Abstract

Mycobacterium branderi, a potential human pathogen first characterized in 1995, has been isolated from respiratory tract specimens. We report here a case in which M. branderi was the only organism isolated upon culture from a hand infection. This isolate, along with a second isolate from a bronchial specimen, was subjected to conventional identification tests for mycobacterial species. Further analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of mycolic acids and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed, and the antibiotic susceptibility profile was determined for both strains. Biochemical tests and the HPLC pattern were consistent with that of M. branderi and M. celatum, which are very similar. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of both strains corresponded to that of M. branderi and enabled us to confidently differentiate this organism from other closely related species such as M. celatum. This contributes to a further understanding of the status of this species as a potential human pathogen as well as illustrating the need for molecular diagnostics as a complementary method for the identification of rare mycobacterial species.

CASE REPORT

In February 1998, a 52-year-old female with a 4-year history of dermatomyositis presented to the emergency department of the St-Boniface General Hospital, Winnipeg, Canada, with pain and swelling of the right fifth digit and wrist. Early in the course of her disease, she had been treated with azathioprine (Imuran) and chloroquine (Plaquenil). These medications had been discontinued due to side effects. She worked as a bank teller until 1996, and was presently unemployed, living on a farm. Autoimmune tenosynovitis was diagnosed, and she was started on prednisone (20 mg a day). In July of the same year, she developed an ulcer on the fifth digit, which was swabbed and cultured. There was no history of trauma. Gram stain, fungal stain, viral cultures, fungal cultures, and aerobic and anaerobic bacterial cultures were all negative. An X ray of the hand was normal. The white blood cell count was 11.8 × 109/liter, with 89% neutrophils. She was initially started on metronidazole and cefazolin, but there was poor clinical response to this therapy. A month later, she developed ulcerative subcutaneous nodules, and on examination, the patient had evidence of tenosynovitis of the right fifth digit and wrist, chronic induration of the wrist, and subcutaneous white nodules along the volar aspect of the forearm. There was nontender axillary adenopathy. Surgical debridement of the right palm and wrist was performed. Histopathology of this tissue revealed caseating granulomas. Cultures of the drainage were negative for bacterial and fungal culture. Acid-fast bacillus smears were positive, and she was started on isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for presumptive M. tuberculosis infection. It subsequently grew a pure culture of acid-fast nontuberculous mycobacteria. The provincial Mycobacteriology Laboratory at the Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Canada, identified the isolate as M. branderi. Following definitive identification, the antituberculous drugs were discontinued and the patient received empiric antimicrobial therapy with clarithromycin (1,000 mg twice a day [b.i.d.]) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) (one double-strength tablet b.i.d.). Two weeks later, the patient continued to have yellow, odorless discharge from the incision sites on the flexor aspect of the right palm and the right wrist. There were persistent erythema and induration surrounding the draining sinuses on the wrist. Ciprofloxacin (750 mg b.i.d.) was added to the treatment regimen, and the clarithromycin dose was decreased to 500 mg b.i.d. Six weeks later, there had been a dramatic improvement in her right hand and wrist, with resolution of the draining sinuses in the right palm and a significant decrease in the open area in the right wrist. The induration was mostly resolved, although she continued to have some erythema surrounding a 2.5-by-4-cm ulcer in the right wrist area, which was gradually resolving. She received a total of 19 months of antibiotics.

In January of 1999, an additional case of M. branderi was detected from a 74-year-old female with shortness of breath together with back and chest pain who was referred to a respiratory clinic at the Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg. Chest X ray revealed middle lobe collapse and peripheral pneumonic infiltrates. Clinical symptoms persisted after empiric ciprofloxacin treatment for 2 weeks. Three sputum samples were submitted to the same laboratory where the M. branderi isolate from the first case were identified. One of the three submitted sputum cultures grew M. avium complex. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen was also submitted, which was negative for routine bacteriology but grew a pure culture of acid-fast nontuberculous mycobacteria, subsequently identified as M. branderi. One year later, the patient remained symptomatic and the underlying cause of disease remained unclear.

M. branderi is a newly described species of mycobacterium (12), and its role as a human pathogen is not well defined. The previously described isolates of M. branderi were respiratory tract isolates obtained from nine patients, some of whom had cavitary mycobacteriosis of the lungs (12). Repeat samples presented M. branderi as the only cultivable organism, suggesting its potential pathogenic role in humans (12).

Clinical specimens consisting of hand drainage from the first patient and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from the second patient were submitted for mycobacteriology culture. Middlebrook 12B liquid medium (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) grew acid-fast bacilli that were subcultured onto Middlebrook 7H10 agar. Each specimen grew a pure culture of M. branderi. On Middlebrook 7H10 agar medium, each clinical isolate of M. branderi showed two colony types: one white and the other opaque. Both colony types were nonchromogenic, raised, smooth edged, and domed. The Kinyoun acid fast stain demonstrated pleomorphic, beaded, slightly curved acid-fast bacilli. The AccuProbe test (Gen-Probe, San Diego, Calif.) was performed according to manufacturer's instruction and was negative for M. tuberculosis complex and M. avium complex.

Biochemical testing of the specimens was performed by conventional methods as previously described (11, 13, 16) and gave identical results for the two organisms isolated (Table 1). Both showed growth from 25 to 42°C and were nonchromogenic. Niacin, nitrate reductase, Tween 80 hydrolysis, urease, tellurite reduction, and iron uptake tests were all negative; as well, there was no acid production from mannitol, sorbitol, and inositol. Both organisms could not utilize sodium citrate as a sole source of carbon. Both organisms were positive for heat-stable catalase, arylsulfatase activity, and pyrazinamidase.

TABLE 1.

Growth characteristics and biochemical testing results of the two clinical isolates in comparison with M. branderi (12) and the closely related species M. celatum (4)a

| Biochemical test | Clinical isolates | M. branderi | M. celatumb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth temp | |||

| 25°C | + | + | + |

| 28°C | + | + | |

| 31°C | + | + | |

| 42°C | + | + (45°C) | + (45°C) |

| Pigment production | |||

| Light | − | − | − |

| Dark | − | − | − |

| Niacin | − | − | − |

| Nitrate reductase | − | − | − |

| Catalase, >45 mm foam | − | − | − |

| 68°C catalase | + | + | |

| Arysulfatase activity | + | + | + |

| Tween 80 hydrolysis | − | − | − |

| Urease activity | − | − | − |

| Tellurite reduction | − | + | |

| 5% NaCl tolerance | − | − | |

| Pyrazinamidase | + | Trace to 2+ | + |

| Iron uptake | − | − | |

| Sodium citrate utilization | − | ||

| Acid production from: | |||

| Mannitol | − | ||

| Sorbitol | − | ||

| Inositol | − |

+, positive; −, negative.

A pale yellow pigment may be observed in older cultures.

Mycolic acid analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed according to the standardized method (5). The HPLC analysis of mycolic acids of both isolates produced a chromatographic pattern very similar to the patterns produced by M. celatum (6), with the same retention times, but with thicker-looking peaks, different peak height ratios, and less separation within the peaks of the second cluster. Both species have HPLC chromatographic patterns occurring as double clusters not unlike those of M. xenopi and the M. avium complex. The patterns of both isolates also showed additional small peaks at the front of the second cluster.

Sequence-based species identification using the 16S rRNA gene (14) was performed for both specimens. With the first specimen, both colony types were sequenced to confirm culture purity. Sequencing reactions were performed with the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and run on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Resulting sequences were assembled and analyzed using Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Inc. Madison, Wis.), resulting in a 1,458-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene, equivalent to positions 28 to 1490 of the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene. The sequences of both organisms isolated, which were identical, showed highest percent similarity (99.7%) to that of M. branderi ATCC 51789 (GenBank accession no. X82234).

BACTEC 12B radiometric broth macrodilution sensitivity testing was performed on the clinical isolates according to the method used for M. avium complex strains (8, 15). The following drugs were tested, and their MIC results are indicated in Table 2: amikacin, capreomycin, clarithromycin, clofazamine, ciprofloxacin, ethambutol, ethionamide, kanamycin, ofloxacin, rifabutin, rifampin, sparfloxacin, streptomycin, and thiacetazone.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial sensitivity results for the two clinical isolates of M. branderi

| Antibiotic | Concn tested (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) for isolate:

|

Suggested interpretation(s)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||

| Amikacin | 2.0, 4.0, 8.0 | ≤2.0 | 8.0 | S, Rb |

| Capreomycin | 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 | 2.5 | 5.0 | |

| Clarithromycin | 2.0, 8.0, 32.0 | ≤2.0 | ≤2.0 | Sc |

| Clofazimine | 0.06, 0.12, 0.25 | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | Sb |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 | ≤1.0 | ≤1.0 | Sb |

| Ethambutol | 2.0, 4.0, 8.0 | ≤2.0 | 4.0 | S, MSb |

| Ethionamide | 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 | >20 | >20 | Rb |

| Kanamycin | 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 | 10.0 | >20 | |

| Ofloxacin | 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 | |

| Rifabutin | 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 | 2.0 | >2.0 | Rc |

| Rifampin | 0.5, 2.0, 8.0 | >8.0 | >8.0 | Rb |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | |

| Streptomycin | 2.0, 4.0, 8.0 | ≤2.0 | ≤2.0 | Sb |

| Thiacetazone | 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 | >4.0 | >4.0 | |

Interpretations not yet standardized and therefore not necessarily correlating with clinical efficiency. Codes: S, susceptible; MS, moderately susceptible; R, resistant.

Based on tentative resistance breakpoints of M. avium complex isolates, as suggested by Inderlied et al. (10).

Discussion.

Nontuberculosis mycobacterium (NTM) species are becoming increasingly important in the clinical setting, causing nosocomial outbreaks or pseudo-outbreaks; pulmonary disease; lymphadenitis; skin, soft tissue, or skeletal infections; and AIDS-related and -nonrelated disseminated infections, among others (1). Although it is generally believed that the environment is the source of most NTM infections, their pathogenesis remains irresolute and a continuous provision of studies regarding NTM-related infections is required for further knowledge and understanding. This particular study describes two cases implicating M. branderi.

M. branderi was first described in 1992 by Brander et al. as part of the Helsinki group (2), consisting of 14 pure isolates later confirmed to be M. branderi and M. celatum (12). On the basis of biochemical and lipid characteristics and 16S ribosomal sequencing, the nine M. branderi organisms were assigned a unique species. M. branderi is initially separated from similar slow-growing species by biochemical test results including growth at 45°C, negative Tween 80 hydrolysis, and positive 14-day arylsulfatase test (2). Based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, M. branderi is distinct from, but most closely related to, M. celatum (12).

For the two patient isolates described in this report, the conventional biochemical test panel for mycobacterial species identification was not conclusive due to the generally inert nature of this organism and its similar biochemical profile with other species. M. branderi resembles M. celatum, M. xenopi, M. avium complex, and M. malmonese in growth characteristics (2). M. branderi and M. xenopi show no enzymatic difference (2), but M. branderi is differentiated on the basis of its smooth and dome-shaped colonies on 7H10 agar, increased growth at 25°C, lack of pigmentation, and differing HPLC patterns of fatty acids and alcohol composition (12). M. branderi is differentiated from most of the M. avium complex by a positive arylsulfatase test (2) and from M. malmonese and M. shimodei by a negative Tween 80 hydrolysis test (12). Occasionally, M. branderi may be differentiated from older cultures of M. celatum by a lack of pigment, although in general M. celatum is nonchromogenic. We have found that Tellurite reduction was negative for both clinical strains of M. branderi, whereas strains of M. celatum (n = 24) are positive for this test (4). This may serve as a tool to differentiate these two species biochemically. Further analysis by HPLC of mycolic acids and 16S rRNA sequencing was required for species differentiation between M. branderi and M. celatum.

The mycolate pattern of M. branderi is of the same type as that of M. avium complex and M. xenopi, as all contain alpha-, keto-, and carboxymycolates (2). The HPLC pattern of both clinical isolates demonstrated a double cluster profile matching those of the limited number of strains of M. branderi analyzed to date and very closely resembling the pattern of M. celatum. In comparison with the M. celatum pattern, M. branderi appears to have better-developed early peaks in the first cluster, less-separated peaks in the second cluster, and different ratios for the peak heights with thicker peaks (M. M. Floyd, personal communication). The pattern obtained with M. branderi ATCC 51798T has the same characteristics as the patterns of the two clinical isolates, with the exception of the smaller peaks in front of the second cluster being less evident. Furthermore, these smaller peaks may occasionally be detected in strains of M. celatum. The difference between the chromatographic patterns of M. celatum and M. branderi can be subtle, and more strains must be examined before these particular variations to the M. celatum patterns can be attributed only to M. branderi (W. R. Butler, personal communication).

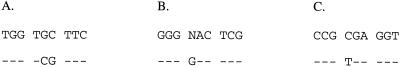

At present, 16S rRNA gene sequencing remains the sole definitive means to differentiate between them. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of the clinical isolates were most closely matched with that of M. branderi ATCC 51789T (EMBL or GenBank accession no. X82234), with a 99.7% similarity, which included three mismatches and one ambiguity (or n). M. branderi ATCC 51789T and ATCC 51788 were sequenced in our laboratory and were found to have a 100% similarity to each other and with both isolates. The region of the 16S rRNA gene containing the differences between the GenBank-submitted sequence and those determined in our laboratory are indicated in Fig. 1. Despite this discrepancy, a significantly lower percent similarity, 95.3 to 95.5, was seen with the various M. celatum clusters designated type 1 (accession no. L08169), type 2 (accession no. L08170) (4), and type 3 (accession no. Z46664) (3), demonstrating the ability of 16S rRNA gene sequencing to differentiate between the two species.

FIG. 1.

Clarification of discrepancies and ambiguity detected with the only available nucleotide entry of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of M. branderi in the GenBank database. The top row shows the sequence of ATCC 51789 (accession no. X82234); the bottom row shows the sequence obtained for M. branderi ATCC 51789, ATCC 51788, isolate 1, and isolate 2 from our institution. E. coli positions within 16S rRNA gene are nucleotides 1016 to 1024 (A), nucleotides 1141 to 1149 (B), and nucleotides 1163 to 1171 (C). Dashes indicate identical nucleotides.

Susceptibility patterns observed for the Helsinki strains included resistance to isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and cycloserine and susceptibility to streptomycin, ethionamide, ethambutol, and capreomycin (2) based on the methodology described by Canetti et al. in 1969 (7). It was also stated that susceptibility to ethambutol in combination with resistance to cycloserine is not commonly observed in other species of mycobacteria (12). Other than for members of the M. tuberculosis complex, no standardized methods are available for the susceptibility testing of mycobacterial species. Furthermore, the clinical efficiency and outcome of antimicrobial treatment of NTM infections in correlation with susceptibility results have yet to be studied extensively (9, 10). Interpretations of MICs determined for M. avium isolates have been suggested (8, 10, 15) and are the only basis available for a tentative interpretation of the susceptibility patterns of the M. branderi isolates in this study. The finger infection resolved following treatment with ciprofloxacin. However, the lung infection did not improve, suggesting the possibility of another disease or inadequate treatment.

Although M. branderi has previously been isolated from respiratory tract specimens, this is the first reported case of isolation from a wound infection. The isolation of M. branderi as a sole pathogen from a hand infection indicates that this organism may be more pathogenic than previously recognized. Additional studies are required to further characterize M. branderi and understand the role of this species as a human pathogen.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:S1–S25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brander E, Jantzen E, Huttunen R, Julkunen A, Katila M-L. Characterization of a distinct group of slowly growing mycobacteria by biochemical tests and lipid analyses. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1972–1975. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.1972-1975.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bull T J, Shanson D C, Archard L C, Yates M D, Hamid M E, Minnikin D E. A new group (type 3) of Mycobacterium celatum isolated from AIDS patients in the London area. Int J Syst Bact. 1993;45:861–862. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler W R, O'Connor S P, Yakrus M A, Smithwick R W, Plikaytis B B, Moss C W, Floyd M M, Woodley C L, Kilburn J O, Vadney F S, Gross W M. Mycobacterium celatum sp. nov. Int J Syst Bact. 1993;43:539–548. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler W R, Floyd M M, Silcox V, Cage G, Desmond E, Duffey P S, Guthertz L S, Gross W M, Jost K C, Ramos L S, Thibert L, Warren N. Standardized method for HPLC identification of mycobacteria. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler W R, Floyd M M, Silcox V, Cage G, Desmond E, Duffey P S, Guthertz L S, Gross W M, Jost K C, Ramos L S, Thibert L, Warren N. Mycolic acid pattern standards for HPLC identification of mycobacteria. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canetti G, Fox W, Khomenko A, Mahler H T, Menon N K, Mitchinson D A, Rist N, Smelev N A. Advances in techniques of testing mycobacterial drug sensitivity and use of sensitivity tests in tuberculosis control programmes. Bull W H O. 1969;41:21–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heifets L, Lindholm-Levy P, Libonati J, Hooper N, Laszlo A, Cynamon M, Siddiqi S. Radiometric broth macrodilution method for determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) with Mycobacterium avium complex isolates. Denver, Colo: National Jewish Center for Immunology and Respiratory Medicine; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heifets L B. Drug susceptibility testing. Clin Mycobacteriol Clin Lab Med. 1996;16:641–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inderlied C B, Nash K A. Antimycobacterial agents: in vitro susceptibility testing, spectra of activity, mechanisms of action and resistance, and assays for activity in biological fluids. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 127–175. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent P T, Kubica G P. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. Atlanta, Ga: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services publication (CDC) 86-8230. Centers for Disease Control; 1985. pp. 71–157. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koukila-Kähkölä P, Springer B, Böttger E C, Paulin L, Jantzen E, Katila M. Mycobacterium branderi sp. nov., a new potential human pathogen. Int J Syst Bact. 1995;45:549–553. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-3-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metchock B G, Nolte F S, Wallace R J., Jr . Mycobacterium. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 399–437. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Relman D A. Universal bacterial 16S rDNA amplification and sequencing. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddiqi S H, Heifets L B, Cynamon M H, Hooper N M, Laszlo A, Libonati J P, Lindholm-Levy P J, Pearson N. Rapid broth macrodilution method for determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations for Mycobacterium avium isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2332–2338. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2332-2338.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witebsky F G, Kruczak-Filipov P. Identification of mycobacteria by conventional methods. Clin Microbiol Clin Lab Med. 1996;16:569–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]