Abstract

We report a patient with chronic granulomatous disease who developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and a subphrenic abscess. During treatment, high levels of Aspergillus antigen were detected in the abscess, but circulating antigen and Aspergillus DNA were undetectable in the serum.

CASE REPORT

A 4-year-old boy with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease was referred to our hospital for treatment of invasive aspergillosis that had been diagnosed and treated at another hospital. A computerized tomography scan of the chest showed two large pulmonary infiltrates with minimal invasion of a rib on the right side and a subphrenic abscess. A bronchoscopy had been performed, and Aspergillus fumigatus was cultured from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The infection had progressed despite treatment with amphotericin B at a dose of 14 mg per day, which corresponds with a daily dose of 1 mg per kg of body weight for 4 weeks. A fine-needle aspiration of the subphrenic abscess was performed and A. fumigatus was recovered by culture. The treatment was changed to voriconazole at a dose of 4 mg/kg b.i.d. (emergency use protocol; Pfizer Ltd., Sandwich, United Kingdom) after informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents. After 4 weeks of intravenous therapy, there was radiological evidence of a response and treatment was continued with oral voriconazole. The infection, however, progressed after 8 weeks of oral treatment, with a repeat computerized tomography scan showing destruction of a rib, subcutaneous infiltration, and enlargement of the subphrenic abscess. A second fine-needle aspiration of the abscess was performed, and cultures yielded A. fumigatus. The levels of voriconazole in plasma were regarded as being too low, and the drug was again administered intravenously at a dose of 100 mg, three times a day. The child showed a favorable response to this dose, and after a total of 10 months the voriconazole was discontinued and secondary prophylaxis with itraconazole at a daily dose of 6 mg per kg was commenced.

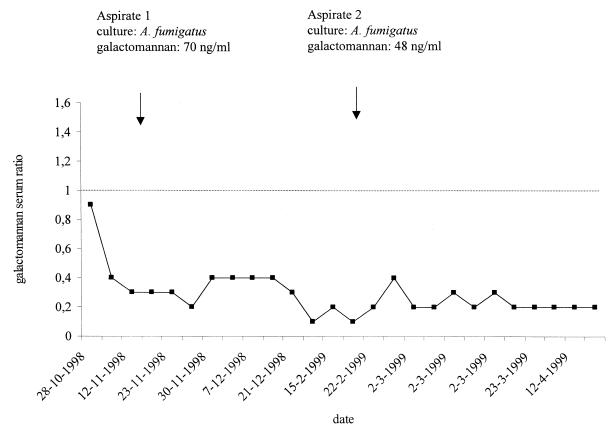

Circulating galactomannan was not detected by a commercial sandwich enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) (Platelia Aspergillus; Bio-Rad, Marnes-La-Coquette, France) in 26 undiluted serum samples obtained over a period of 6 months (Fig. 1). The first serum sample was obtained 18 days after treatment with amphotericin B had commenced. Since an excess of antigalactomannan antibody in the serum could result in false-negative reactivity of the ELISA by the formation of immune complexes, all serum samples were retested in a 1:10 dilution, but again, no ELISA reactivity was observed. The presence of serum immunoglobulin G antibodies against Aspergillus species was determined using a commercial ELISA (Genzyme Virotech GmbH, Rüsselsheim, Germany). Low levels of antibody were detected in four serum samples, but these levels were considered insufficient to interfere with the antigen detection assay. Galactomannan was not detected in two urine samples obtained during the course of infection. Furthermore, the buffy coat obtained from an EDTA-treated blood sample was tested, but no galactomannan was detected. However, high levels of galactomannan (70 and 48 ng/ml) were present in the two aspirates obtained from the patient. The galactomannan concentration of a serum sample that was obtained simultaneously with the second aspirate was 0.1 ng/ml, which suggests that a 480-fold difference in galactomannan levels was present between the abscess and serum. To detect circulating Aspergillus DNA, a PCR was performed exactly as described previously (1). The amplification reactions, which were targeted to mitochondrial DNA of A. fumigatus, were performed with enzymatic prevention of carryover contamination through the systematic use of uracyl-N-glycosylase (UNG) and with detection of PCR inhibitors by an internal control as previously described (1). Among eight plasma samples that were analyzed, PCR inhibitors were detected in five. Aspergillus DNA was not detected by PCR in the remaining three plasma samples that were obtained during progression of the infection.

FIG. 1.

Results of antigen detection with serum and two aspirates of the subphrenic abscess. Galactomannan ratios are considered negative if they are <1.0 and positive if they are >1.5. Values between 1.0 and 1.5 are indeterminate. The results of PCR performed with plasma obtained on 28 October, 12 November, and 23 November were negative.

Invasive aspergillosis is a life-threatening infection that may affect patients with compromised defenses. Early diagnosis is very difficult, but novel tests such as PCR and antigen detection which detect fungal DNA or antigen in body fluids have been developed (2, 3, 7). The presence of circulating markers in the blood corresponds with the development of an infection in the tissues. A promising commercial sandwich ELISA is the Platelia Aspergillus (Bio-Rad), which enables the detection of low levels of the Aspergillus antigen galactomannan (6). Excellent performance characteristics in patients with hematological malignancies have been reported (3 4, 5). In a recent prospective, pathology-controlled study that included over 240 episodes of neutropenia, a sensitivity of 92.6% and a specificity of 95.4% were found when serial monitoring of galactomannan was performed (4). We report a case of proven invasive aspergillosis in a nonneutropenic host in whom we detected high galactomannan levels at the site of infection but were unable to detect circulating Aspergillus markers.

Absence of circulating antigen in patients with confirmed disease has been reported previously, mostly for neutropenic patients (2, 4), but the reason for false-negative reactivity remains unknown. We have demonstrated that high levels of galactomannan may be present at the site of infection but not in the serum, which suggests that antigen is not released into body fluids. This is supported by the absence of circulating Aspergillus DNA in the blood. Encapsulation of the infectious process could prevent leakage of the Aspergillus antigen into body fluids. Also, the level of angioinvasion could be lower in this host group than in neutropenic patients, thus preventing systemic spread of antigen. If the immune response of the host modifies the level of circulating antigen, this would have significant consequences for the monitoring of response to antifungal therapy. In that situation, a decline of the antigen titer would not necessarily be correlated with a decrease of fungal burden but rather with encapsulation of the process. Viable fungi could endure in the tissue while circulating Aspergillus markers remain undetectable. Alternatively, the false-negative ELISA reactivity could be due to pretreatments with amphotericin B that have suppressed the production of galactomannan by the fungus. Pretreatment serum samples from our patient were not available for analysis. Nevertheless, even during clinical and radiological progression of the infection, circulating antigen could not be detected. Finally, A. fumigatus strains may differ in their ability to produce galactomannan in response to their environment, for instance, under microaerophilic conditions or at low pHs. The kinetics of galactomannan in infected patients, especially nonneutropenic hosts, as well as the effect of the host response on the circulation of antigen are largely unknown and require further studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bretagne S, Costa J-M, Marmorat-Khuong A, Poron F, Cordonnier C, Vidaud M, Fleury-Feith J. Detection of Aspergillus species DNA in bronchoalveolar lavage samples by competitive PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1164–1168. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1164-1168.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bretagne S, Costa J M, Bart-Delabesse E, Dhedin N, Rieux C, Cordonnier C. Comparison of serum galactomannan antigen detection and competitive polymerase chain reaction for diagnosing invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1407–1412. doi: 10.1086/516343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einsele H, Hebart H, Roller G, Löffler J, Rothenhöfer I, Müller C A, Bowden R A, van Burik J, Engelhard D, Kanz L, Schumacher U. Detection and identification of fungal pathogens in blood by using molecular probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1353–1360. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1353-1360.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maertens J, Verhaegen J, Demuynck H, Brock P, Verhoef G, Vandenberghe P, Van Eldere J, Verbist L, Boogaerts M. Autopsy-controlled prospective evaluation of serial screening for circulating galactomannan by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for hematological patients at risk for invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3223–3228. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3223-3228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohrlich P, Sarfati J, Mariani P, Duval M, Carol A, Saint-Martin C, Bingen E, Latgé J P, Vilmer E. Prospective sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for serum galactomannan: early predictive value and clinical use in invasive aspergillosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:232–237. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stynen D, Goris A, Sarfati J, Latgé J P. A new sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect galactofuran in patients with invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:497–500. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.497-500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verweij P E, Latgé J-P, Rijs A J M M, Melchers W J G, De Pauw B E, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A A, Meis J F G M. Comparison of antigen detection and PCR assay using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients receiving treatment for hematological malignancies. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3150–3153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3150-3153.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]