Abstract

Omicron, a novel SARS-CoV-2 variant has emerged and is rapidly becoming the dominant SARS-CoV-2 virus circulating globally. It is important to define reductions in virus neutralizing activity in serum of convalescent or vaccinated individuals to understand potential loss of protection from infection or re-infection. Two doses of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccines provided little 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50) antibody immunity against the Omicron variant, even at one-month post vaccination. Booster doses with BNT162b2 in those with two doses of either BNT162b2 or CoronaVac provided acceptable neutralizing immunity against Omicron variant at 1-month post-booster dose. However, three doses of BNT162b2 elicited higher levels of PRNT50 antibody to Omicron variant suggesting longer duration of protection. Convalescent from SARS-CoV-2 infection did not have protective PRNT50 antibody levels to Omicron, but a single dose of BNT162b2 vaccine provided protective immunity. Field vaccine-efficacy studies against Omicron variant against different vaccines are urgently needed.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, immunity, protection, vaccine, Omicron, BNT162b2, CoronaVac, SinoVac

Text

A novel SARS-CoV-2 variant with increased transmissibility was first reported in South Africa in November 20211, classified as a variant of concern and named Omicron2. The virus had 37 amino acid substitutions in the spike protein of the virus, 15 of them being in the receptor binding domain. It was predicted that some of these amino acid substitutions would have major impact in evading neutralizing antibody. Virus neutralizing antibody is a major determinant of protection from infection in humans and in macaques experimentally challenged with virus3,4. Neutralizing antibody thresholds associated with protection from re-infection or severe disease have been reported5,6. In experimentally infected macaques convalescent from SARS-CoV-2 infection, depletion of CD8 T cells reduced the protective effect from re-infection, suggesting that T cell immunity can contribute to protection4. However, quantitative correlates of T cell protection remain elusive.

Studies on the immunogenicity and vaccine efficacy of BNT162b2 vaccine have been reported, but whole virus inactivated vaccines such as CoronaVac (Sinovac) are less studied. CoronaVac is one of the WHO approved vaccines and over 750 million doses have been administered in more than 40 countries. Phase-three randomized clinical trials of CoronaVac showed efficacies ranging from 50.7% and higher protection from severe disease7,8. But there have been reports of breakthrough infections leading to severe disease and death in CoronaVac vaccinated adults9. Data on the immunogenicity of current COVID-19 vaccines against Omicron variant, is urgently needed.

We had previously demonstrated that those vaccinated with BNT162b2 had markedly higher levels of geometric mean PRNT50 antibody titres compared to those vaccinated with CoronaVac vaccines, at one-month post-second dose of vaccine10. Allowing for antibody waning, we estimated that only 16% of the CoronaVac vaccinated individuals would retain protective thresholds against the wild-type virus while 79.6% of BNT162b2 vaccinees would be similarly protected by six months after second dose of vaccine10. Subsequently, we randomized the cohort receiving CoronaVac vaccine to receive booster doses of CoronaVac or BNT162b2 and showed marked increase in neutralizing antibody following boosting with BNT162b2 but a less optimal responses with CoronaVac11.

However, the emergence of virus variants that are able to partially evade vaccine immunity would compromise vaccine protection. It is important that we rapidly compare virus neutralizing antibody levels to the wild-type virus to which vaccines are developed and Omicron variant, in persons who have received vaccinations or booster doses, for formulation of appropriate public health policy. Here we compare PRNT antibody titres to wild-type SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron variant in previously studied cohorts who recovered from COVID-1912, uninfected community subjects one month after receiving two doses of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccine10, or one month after receiving booster doses of the respective BNT162b2 or CoronaVac or those who received two doses of CoronaVac and received a booster dose of BNT162b2 vaccine11. COVID-19 recovered individuals receiving one dose of vaccines were also studied. Methods used for sampling of participants, serological tests and statistical analyses are detailed in Supplementary Information.

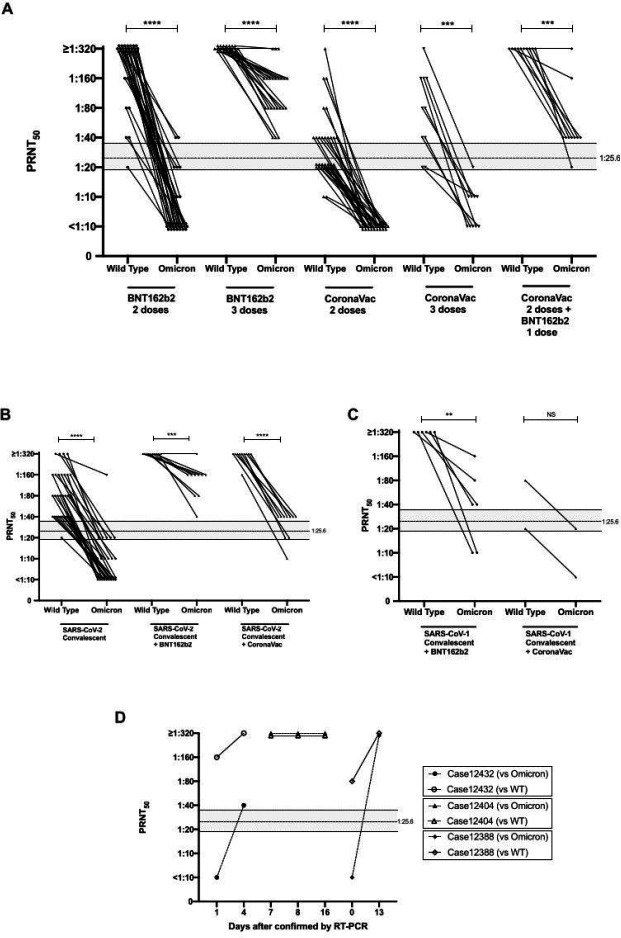

The age, sex numbers of individuals studied and geometric mean PRNT50 titres of the different cohorts are summarized in table 1. The PRNT50 titres with the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 or Omicron variant in these cohorts are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1. PRNT90 data is shown in Supplementary figure 2. PRNT50 titres in COVID-19 vaccinated or convalescent cohorts were markedly lower to Omicron variant than to wild-type virus (Figure 1A–C, Table 1). The fold reduction in comparative GMT to Omicron vs wild-type was 30.9-fold for those receiving two doses of BNT162b2 vaccine, 10.5-fold in COVID-19 convalescent sera and 6.4-fold in those receiving two doses of CoronaVac vaccine (Figure 1A, Table 1). However, comparison of fold-difference in GMT to the two viruses is confounded by groups with low GMT to the wild-type virus because a smaller fold-reduction would already reach the detection threshold. Others report comparable reductions in neutralizing titres to Omicron variant neutralizing titres in sera of vaccinated or COVID-19 convalescent individuals13,14.

Table:

Age, sex and geometric mean 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50) titres vs. Omicron variant

| Exposure group | n | Mean Age (SD) | Age range | Male: female | WT GMT | Omicron GMT | WT; Omicron Fold GMT reduction | Above PRNT50 threshold of protection (1:25.6) 1 month post-vaccine | Above PRNT50 threshold of protection at 5–6 month post-vaccine adjusting for 4.7-fold waning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omicron | Wild-type | Omicron | Wild type | ||||||||

| BNT162b2 (2 doses) | 30 | 51 (14.2) | 25–76 | 16:14 | 216.1 | 7.0 | 30.9 | 1/30 | 29/30 | 0/30 | 25/30 |

| BN162b2 (3 doses) | 23 | 54.6 (14.0) | 30–80 | 11:12 | 320 | 114.9 | 2.8 | 23/23 | 23/23 | 12/23 | 23/23 |

| CoronaVac (2 doses) | 30 | 52.1 (8.2) | 39–73 | 10:20 | 32.5 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 0/30 | 14/30 | 0/30 | 3/30 |

| CoronaVac (2 dose+CoronaVac booster) | 10 | 48.7 (7.4) | 39–59 | 4:6 | 74.6 | 7.6 | 9.7 | 0/10 | 8/10 | 0/10 | 3/10 |

| CoronaVac (2 dose+BNT162b2 booster) | 10 | 48.1 (7.9) | 39–61 | 3:7 | 320 | 52.8 | 6.1 | 9/10 | 10/10 | 2/10 | 10/10 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Convalescent | 30 | 48.9 (15.8) | 20–72 | 13:17 | 85.7 | 8.1 | 10.5 | 1/30 | 29/30 | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| SARS-CoV-2 convalescent + BNT162b2 (1 dose) | 10 | 41.6 (12.4) | 26–58 | 5:5 | 320 | 130 | 2.5 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 7/10 | 10/10 |

| SARS-CoV-2 convalescent + CoronaVac (1 dose) | 10 | 49.9 (9.2) | 37–64 | 5:5 | 298.6 | 30.3 | 9.9 | 8/10 | 10/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 |

| SARS-1 convalescent+BNT162b2 (2 doses)* | 6 | 48.8 (2.9) | 44–52 | 4:2 | 320 | 35.7 | 9.0 | 4/6 | 6/6 | 1/6 | 6/6 |

| SARS-1+CoronaVac (2 doses) | 2 | 52.5 (3.6) | 50–53 | 2:0 | 40 | 10 | 4 | 0/2 | 1/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| COVID-19 (Omicron) Convalescent | 3 | 45 (14.3) | 36–62 | 3:0 | 320 | 320 | 1 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

One of this group received three doses of BNT162b2

Figure 1.

50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50) antibody titres (GMT and SD) to wild-type virus and Omicron variant. Mann-Whitney test was used for significance. See Table for numbers in each group. A. Individuals with 2 or 3 doses of BNT162b2 or CoronVac vaccines, as indicated. B. SARS-CoV-2 convalescent individuals with or without BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccine (one dose). C. SARS-1 convalescent individuals with BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccines. D. PRNT50 antibody titres to wild-type and Omicron variant SARS-CoV-2 viruses in three patients with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infection (see supplementary information for vaccine history and clinical details). ****p<0.0001; ***p p<0.001; **p<0.01; NS p>0.05. Dotted line indicates threshold of protection and shading indicates 95% confidence intervals (see text).

Using methods previously described by Khoury and colleagues5, we had previously determined that the threshold for 50% protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection was a PRNT50 titre of 25.6 with 95% confidence intervals of 1:18.3–1:36.012. Using this threshold for protection, we observed that 29 of 30 BNT162b2 vaccinated individuals retained protective PRNT50 antibody titres to wild-type virus but only 1 (3%) in 30 met this threshold with Omicron variant at one month after second dose of vaccine. None of those vaccinated with CoronaVac met this threshold of protective antibody with the Omicron variant (Table 1). A booster dose of BNT162b2 restored protective thresholds of Omicron variant PRNT50 antibody in all 23 vaccinees but a booster dose of CoronaVac in CoronaVac vaccinees did not provide protective levels of antibody. However, 9 (90%) of 10 of those receiving two doses of CoronaVac boosted with BNT162b2 had protective levels of PRNT50 antibody with the Omicron variant. In those who had past COVID-19 infection followed by BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccine, 10 of 10 and 8 of 10 respectively, had protective levels of PRNT50 antibody with the Omicron variant (Table 1).

It was estimated that neutralizing antibody fell by 4.7-fold within 5 to 5.8 months after the second dose of BNT162b2 vaccine and fell 6.4-fold within 6 months following CoronaVac vaccination15,16. Allowing for a 4.7-fold decline of PRNT50 antibody levels to Omicron variant, we estimated that none of the BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccinated individuals would retain neutralizing antibody levels above the protective threshold at 5–6 months post immunization, while 12 of 23 of those vaccinated and boosted with BTN162b2 would do so, as would 2 of 10 CoronaVac vaccinated individuals boosted with BNT162b2. None of 10 of CoronaVac vaccinated CoronaVac boosted with CoronaVac would retain PRNT50 antibody levels above this threshold (Table 1).

Our COVID-19 convalescent cohort was already 4.8 to 6.5 months after onset of illness and only one of 30 individuals met the protective threshold for Omicron variant. Vaccinating COVID-19 convalescent individuals with one dose of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccine boosted PRNT50 antibody levels to above the protective threshold against Omicron. However, the levels achieved in CoronaVac vaccinated individuals was lower; and allowing for 4.7-fold waning of antibody, their PRNT50 would have dropped below the protective threshold although 7 of 10 who had BNT162b2 vaccinated individuals would still have protective levels of antibody to Omicron (Table 1).

We have previously shown SARS-CoV-1 convalescent sera obtained from those infected during the 2003 SARS outbreak had no neutralizing antibody to SARS-CoV-217. When SARS-survivors from 2003 were vaccinated with two doses of BNT162b2, two of six elicited protective levels of PRNT50 antibody to Omicron but vaccination with CoronaVac (n=2) did not (Table 1).

Three returning travelers diagnosed with Omicron variant were studied as controls. They were males (range in age from 36–62) vaccinated with two doses of RNA (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) vaccines (see Supplementary information for details). Cases 12388 and 12432 had detectable PRNT50 antibody (titres of 80 and 160, respectively) to wild-type virus on the day of first RT-PCR detection or the day after, but did not have detectable cross-neutralizing antibody to Omicron variant (Figure 1D), explaining why they had breakthrough infections. They rapidly mounted neutralizing antibody to Omicron variant of ≥1:320 by day 4 (Case 12432) or day 13 (sera between day 1 and day 13 not being available for case 12388). Serum from Case 12404 was first available at days 7 by which time he had PRNT50 titres of ≥1:320 to both wild-type and Omicron variant. This rapid neutralizing antibody response in RNA vaccinated individuals to an antigenically divergent variant suggests that such individuals are likely to be protected from severe disease.

We included the WHO standard NIBSC 20/136 in two PRNT esperiments with PRNT50 titres of 1:20 and 1:40 respectively with Omicron and 1:320 with wild-type virus.

This study had some limitations. There were relatively small numbers in the individual groups, but as estimated from our power calculations (see Supplementary information), the sample size was adequate to demonstrate significant conclusions. We have not investigated other antibody activities such as binding to spike protein or binding to Fc receptors which may confer antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity via natural killer cell mediated (ADCC). In a previous study with this cohort, we showed that both spike binding antibody and FcgRIIIa binding antibodies paralleled the PRNT antibody responses with these two vaccines10. However, it is possible that these antibodies may be less affected by the mutations found in the Omicron variant and may play relatively more important protective roles in protection from Omicron variant. We have not investigated T cell responses elicited by these vaccines that may provide protection, at least against severe disease.

In summary, we demonstrate that two doses of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccines provide little neutralizing antibody immunity against the Omicron variant, even at one-month post vaccination. Booster doses with BNT162b2 in those with two doses of either BNT162b2 or CoronaVac provide acceptable neutralizing immunity against Omicron variant at 1-month post-booster dose. However, because three doses of BNT162b2 elicit higher levels of PRNT50 antibody to Omicron variant than two doses of CoronaVac followed by a booster with BNT162b2, waning antibody is likely to result in faster loss of protection with the latter schedule. It must be noted however, that CoronaVac, a whole virus inactivated vaccine with multiple viral proteins, has previously been shown to elicit a wider range to T cell responses which may compensate for some loss of neutralizing antibody protection10. Vaccine-efficacy studies against Omicron variant in countries where these different vaccines are being used, are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Health and Medical Research Fund Commissioned Research on the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), Hong Kong SAR (COVID1903003; COVID190126) (CKPM, DSH and MP), US National Institutes of Health (contract no. U01-Grant AI151810) (MP), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)/Research Grants Council (RGC) Joint Research Scheme (N_JHKU737/18) (CKPM and MP), RGC theme-based research schemes (T11-712/19-N and T11-705/21-N) (DSH, MP), Guangdong Province International Scientific and Technological Cooperation Projects (2020A0505100063) (CKPM), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded through the Korea government (NRF-2018M3A9H4055203) (CKPM), AIR@InnoHK (EHYL) and C2i (LLMP, MP) administered by Innovation and Technology Commission of Hong Kong.

Contributor Information

Malik Peiris, University of Hong Kong.

Samuel Cheng, University of Hong Kong.

Chris Ka Pun Mok, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Yonna Leung, University of Hong Kong.

Susanna Ng, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Karl Chan, University of Hong Kong.

Fanny Ko, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Karen Yiu, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Bosco Lam, North Lantau Hospital.

Eric Lau, University of Hong Kong.

Ken Chan, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Leo Luk, University of Hong Kong.

John Li, University of Hong Kong.

Leo Tsang, University of Hong Kong.

Leo Poon, University of Hong Kong.

Chunke Chen, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

David Hui, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

References

- 1.Viana R, et al. 2021. https://krisp.org.za/manuscripts/ZHTOWa-MEDRXIV-2021-268028v1-deOliveira.pdf

- 2.World Health Organization. 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern

- 3.Addetia A, et al. J Clin Microbiol. 58(11):e02107–20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahan K, et al. Nature. 590:630–634 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoury DS, et al. Nat Med. 27:1205–1211 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cromer D, et al. Lancet Microbe. (2021) doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00267-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 21:181–192 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jara A, et al. N Engl J Med. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bangkok Post, 2021. (https://www.bangkokpost.com/world/2133987/hundreds-of-vaccinated-indonesian-health-workers-infected).

- 10.Mok CKP, et al. Respirology Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mok CKP, Am J Resp and Crit Care Med -in press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau EH, et al. EClinicalMedicine. 41:101174 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cele S, et al. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.12.08.21267417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu L, et al. Clin Infect Dis (2021) Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin EG, et al. N Engl J Med. 385:e84. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng G, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 7:S1473-3099(21)00681-2. (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lv H et al. , Cell Reports 31; 107725 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.