Abstract

Aeroallergen sensing by airway epithelial cells triggers pathogenic immune responses leading to type 2 inflammation, the hallmark of chronic airway diseases such as asthma. Tuft cells are rare epithelial cells and the dominant source of IL-25, an epithelial cytokine, and cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs), lipid mediators of vascular permeability and chemotaxis. How these two mediators derived from the same cell might cooperatively promote type 2 inflammation in the airways has not been clarified. Here, we showed that inhalation of the parent leukotriene C4 (LTC4) in combination with a subthreshold dose of IL-25 led to activation of two innate immune cells: inflammatory type 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) for proliferation and cytokine production, and dendritic cells (DCs). This cooperative effect led to a multiple fold greater recruitement of eosinophils as well as CD4+ T cell expansion indicative of true synergy. While lung eosinophilia was dominantly mediated through the classical CysLT receptor CysLT1R, type 2 cytokines and activation of innate immune cells required signaling through CysLT1R and partially CysLT2R. Tuft cell-specific deletion of Ltc4s, the terminal enzyme required for CysLT production, reduced lung inflammation and the systemic immune response after inhalation of the mold aeroallergen Alternaria; this effect was further enhanced by concomitant blockade of IL-25. Our findings identified a potent synergy of CysLTs and IL-25 downstream of aeroallergen-trigged activation of airway tuft cells leading to a highly polarized type 2 immune response and further implicate airway tuft cells as powerful modulators of type 2 immunity in the lungs.

One Sentence Summary:

Tuft cells produce LTC4 and IL-25 which cooperate to induce allergen-driven airway inflammation.

INTRODUCTION:

Type 2 immunity is a host defense mechanism engaged to expel helminths and to repair epithelial cell damage from viruses, allergens and particulate matter. Aeroallergens subvert this system by activating epithelial cells for release of cytokines (IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP) and danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs and epithelial cell cytokines act in concert to stimulate tissue resident DCs, macrophages, and innate type 2 lymphoid cells (ILC2s) to direct and propagate type 2 inflammation, leading to chronic airway inflammatory diseases such as asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis (1, 2). Besides the classical epithelial cell cytokines, multiple studies suggest that DCs and ILC2s are also activated by lipid mediators (3–5) and neuropeptides (6–8). While genetic and immunologic studies have defined barrier epithelial cell pathways that amplify mucosal inflammation, the events that initiate pathogenic immune recognition are poorly understood.

Airway solitary chemosensory cells are unique epithelial cells that resemble taste bud cells in their expression of taste signaling molecules and are referred to as tuft cells (9). Unlike the chemosensory cells in taste buds, tuft cells are scattered as solitary cells in the epithelium of the upper and large lower airway and are largely absent in the lung except for in the setting of post-viral remodeling (10, 11). Tuft cells in the trachea are commonly referred to as cholinergic brush cells (12, 13), while a similar population in the nasal respiratory mucosa is termed solitary chemosensory cells (SCCs) (14). A much more abundant subset of chemosensory-like epithelial cells in the olfactory mucosa are named microvillar cells (MVCs) (15). Tracheal brush cells, nasal respiratory SCCs and nasal olfactory MVCs share a core transcriptional profile with tuft cells from other tissue compartments – intestinal, thymic and gallbladder tuft cells – suggesting they belong to one large family of chemosensory tuft cells (16). Their shared markers include the Ca2+ triggered cation channel TRPM5, the epithelial cytokine IL-25, the enzyme choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and the transcription factor Pou2f3 (13–17). Notably, the transcripts encoding the lipoxygenase (Alox5, Alox5ap and Ltc4s) and cyclooxygenase (Ptgs1 and Hpgds) pathway enzymes are core transcriptional features of all tuft cells (9, 16, 18, 19). Tuft cells generate cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) ex vivo in response to the mold aeroallergen Alternaria and the dust mite allergen Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (16). Furthermore, tuft cell-deficient Pou2f3−/− mice have reduced eosinophilic lung inflammation after Alternaria inhalation, demonstrating a role of tuft cells in directing innate type 2 immunity in the airways (16). However, the mechanism through which tuft cell-derived CysLTs regulate allergen-triggered type 2 immunity in the airways has not been defined.

CysLTs are named for their canonical generation by leukocytes recruited or activated in the setting of established inflammation (20). CysLTs in the inflamed airways derive from sensitized macrophages (21), IgE-coated mast cells (22), recruited eosinophils (23), and basophils (24), and platelet-leukocyte aggregates (25). Following receptor-mediated Ca2+ flux, phospholipase A2 (PLA2α) releases phospholipids at the outer nuclear membrane to generate free arachidonic acid. The first enzyme of the lipoxygenase pathway, 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), oxidizes arachidonic acid in the presence of 5-LO activating protein (FLAP) to generate leukotriene A4 (LTA4), which is subsequently converted to LTC4 by leukotriene C4 synthase (LTC4S) (26). LTC4 is rapidly exported extracellularly and converted within minutes to LTD4, which in turn is rapidly metabolized to LTE4 (20). CysLTs exert their effects through three G-protein coupled receptors. CysLT1R has high affinity for LTD4 (Kd ~ 1 nM), binds LTC4 with lesser affinity, and can transduce signals to LTE4 (27, 28). CysLT2R binds LTC4 and LTD4 at equimolar concentrations (29) and is resistant to currently available pharmacotherapy targeting CysLT1R. CysLT3R (OXGR1 or GPR99) is a high affinity receptor for LTE4 (30). CysLTs potently augment type 2 immune responses and their role as mediators of bronchoconstriction, vasodilatation and chemotaxis in established allergic inflammation has been well documented (31).

There is an important role for CysLTs in the initial phase of airway immune responses as mediators generated upon allergen sensing by DCs (32), macrophages (33) and epithelial cells (16). These “innate” CysLTs hold emerging biological relevance as drivers of the polarization of the innate immune response. CysLTs condition DCs to prime Th2 cells after initial house dust mite inhalation (34) and synergize with IL-33 for ILC2 activation in the airways through CysLT1R-mediated NFATc translocation relevant to the Alternaria model of innate airway inflammation (3–5). Similar to CysLTs, IL-25 targets both ILC2s and DCs in the naïve airways. IL-25 specifically induces the expansion of a subtype of inflammatory ILC2s characterized by high expression of KLRG1 (7, 35). In addition, IL-25 directly targets lung-resident DCs leading to CD4+ Th2 cell recruitment independent of ILC2 activation (36, 37). Tuft cells are critically positioned at the luminal side of the airway epithelium at the interface of contact with allergens. Tuft cells are the dominant source of IL-25 in the naïve airways (13, 38) and generate CysLTs upon allergen sensing (16). Tuft cells direct both innate and adaptive phase eosinophilic lung inflammation(16). Thus, we wondered whether the central role of tuft cells in driving airway immunity may derive in part from the cooperative effect between these mediators, as has been reported in the intestine (39).

Here, we demonstrated that the two principal inflammatory mediators of tuft cells – LTC4 and IL-25 – synergize to initiate type 2 inflammation in the naïve airways. Subthreshold doses of IL-25 and LTC4, when administered in combination intranasally, induce proliferation of innate immune cells, type 2 cytokine production and recruitment of eosinophils several fold over either of the mediators alone. Tuft cell-targeted deletion of the terminal CysLT biosynthetic enzyme, Ltc4s, in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice led to a reduction in allergen-induced type 2 lung inflammation. Finally, blocking IL-25 in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice further reduced the lymph node response to allergen, demonstrating the contribution of these two tuft cell mediators to developing adaptive immunity. Thus, tuft cells are unique epithelial effector cells capable of inducing airway type 2 inflammation through synergistic cytokine and lipid mediator signaling.

RESULTS:

Exogenous LTC4 amplifies IL-25 induced lung inflammation

The role of tuft cells as initiators of type 2 inflammation was initially attributed to their production of IL-25 (13, 38, 40). CysLTs are one of the major products of airway tuft cells after aeroallergen activation ex vivo (16). The interactions between tuft cell-derived IL-25 and CysLTs in the airways remain unknown. We therefore investigated the effect of these pro-inflammatory mediators on lung inflammation in vivo (Fig. 1A). LTC4 alone (at a concentration of 1.6 nmol) triggered only mild inflammation in naive mice, consistent with previous studies (41) (Fig. 1B, C). A dose-response of intranasal IL-25 revealed that decreasing the concentration below the 500 ng previously used for lung inflammation studies (7, 36) resulted in a precipitous loss of potency to induce eosinophilic inflammation (Fig. S1A). Specifically, 100 ng of IL-25 induced 15-fold lower eosinophilia than 500 ng (Fig. S1A).

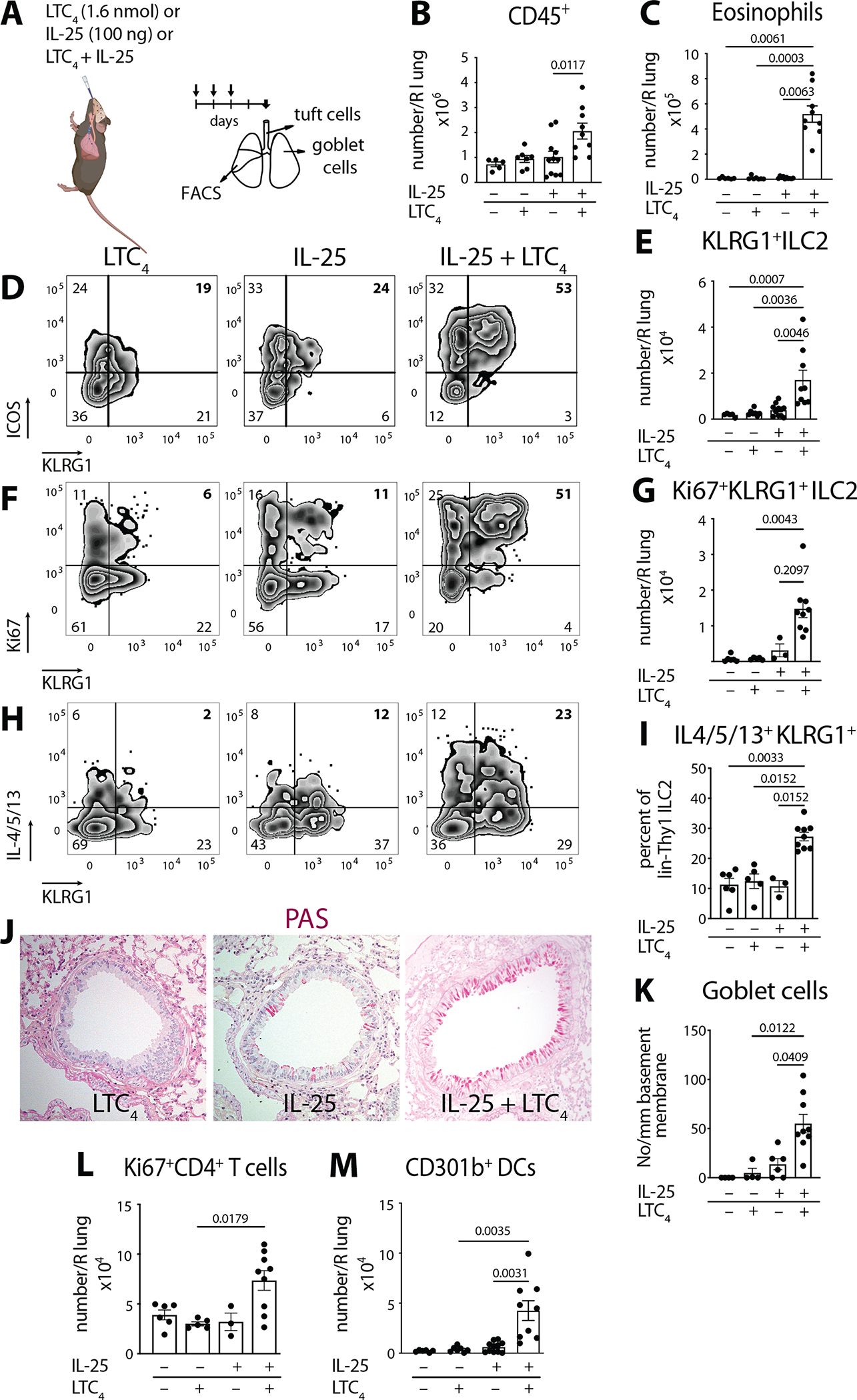

Fig. 1. LTC4 and IL-25 synergize for airway type 2 lung inflammation.

(A) WT mice (C57BL/6) were given three daily inhalations of LTC4 (1.6 nmol), or IL-25 (100 ng) or a combination of LTC4 and IL-25 and assessed 2 days after the last dose. (B) Number of CD45+ cells and (C) number of eosinophils in the right lung assessed by FACS. (D) lin−Thy1+ lung ILC2s were evaluated for expression of KLRG1 and ICOS. (E) Number of KLRG1+ ILC2s in the lung. (F) Intranuclear expression of Ki67 was assessed in lin−Thy1+ lung ILC2s together with KLRG1 surface staining. (G) Number of Ki67+ KLRG1+ ILC2s in the lung. (H) Lung ILC2 cytokine expression was assessed by intracellular staining for IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 after Golgi plug treatment of lung single cell suspensions. (H) Percent of KLRG1+ IL-4/5/13 within the lin−Thy1+ lung ILC2s. (J) Goblet cell hyperplasia in cross sections of the lung assessed by Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stain. (K) Goblet cells were enumerated per mm of basement membrane in the large bronchi. (L) Number of proliferating CD4+ T cells (Ki67+ CD4+ T cells) and (M) Number of CD301b+ DCs in the lung by FACS. Data are means ± SEM pooled from 3 independent experiments, each dot is a separate mouse, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons, p values <0.05 indicated.

When combined with LTC4, low dose 100 ng IL-25 led to a 2-fold increase of CD45+ cells in the lung over either mediator alone (Fig. 1B). This was associated with a notable inflammatory infiltrate in the peribronchial and perivascular space (Fig. S1B). Eosinophils were the most abundant inflammatory cells in the perivascular infiltrate in the lung (Fig. S1C). The combination of IL-25 and LTC4 led to a 47-fold increase of eosinophils compared to IL-25 alone and 59-fold change compared to LTC4 alone (Fig. 1C) suggestive of a synergistic effect of the two tuft cell mediators, multiple fold increase rather than cumulative effect. To determine if this effect is driven by innate immune cells, we first assessed the ILC2 compartment (Fig. S1D) for changes in response to IL-25 and LTC4, we detected a population of KLRG1+ ICOS+ Thy1.2+ ILC2s, similar to the previously described IL-25 dependent inflammatory ILC2s (35) (Fig. 1D). Inhaled low dose IL-25 was insufficient to induce this ILC2 subset, but the addition of LTC4 led to a 4-fold increase in inflammatory KLRG1+ILC2 numbers compared to IL-25 and 6-fold increase compared to LTC4 alone (Fig. 1E). The ILC2 expansion was specific to inflammatory KLRG1+ILC2s, as we did not detect a significant change in the number of any of the subsets of KLRG1−ILC2s (Fig. S1E). To determine if the expansion of ILC2s was driven by recruitment or proliferation, we evaluated Ki67 expression in the lung. Ki67+ cells accounted for 80% of the KLRG1+ ILC2s (Fig. S1F) and their numbers increased 5-fold compared to IL-25 alone and 18-fold compared to LTC4 alone (Fig. 1F, G) with a smaller but significant increase in Ki67+KLRG1−ILC2s (Fig. S1G). Intracellular staining for IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 confirmed a significant increase in type 2 cytokine generation by ILC2s (Fig. 1H, I and Fig. S2A). Consistent with the selective effect of LTC4/IL-25 synergy on KLRG1+ ILC2s, we found that this ILC2 subset exhibited the most prominent increase in ILC2 cytokine production (Fig. 1H, I and Fig. S2A, B).

Whole lung protein evaluation further confirmed a polarization of the immune response: LTC4 + IL-25 augmented type 2 cytokine production over PBS or either mediator alone, with significant increases of three type 2 cytokines in lung homogenates – IL-4 (6-fold), IL-5 (18-fold) and IL-13 (8-fold compared to IL-25 alone) (Fig. S2C). In addition to type 2 cytokines, we detected a significant increase in lung IL-6 and a small but significant augmentation of TNF-α in whole lung homogenates (Fig. S2D). The type 1 cytokine IFN-γ was undetectable and IL-17 family member cytokines were not induced (Fig. S2E). Intriguingly, while neither LTC4 nor IL-25 alone influenced the lung levels of IL-33 protein, when administered together, they caused lung IL-33 to double (Fig. S2F), suggesting that this pathway might act as a “primer” for increased local production of multiple inflammatory cytokines.

Consistent with the observed increase in IL-13, the combination of LTC4 and IL-25 induced lung remodeling with significant goblet cell hyperplasia (Fig. 1J, K). Unexpectedly, despite the clear induction of lung IL-13, the number of DCLK1+ tuft cells assessed in whole tracheal mounts did not change (Fig. S2G). To determine if tracheal tuft cells proliferate in response to IL-13 as reported for nasal respiratory tuft cells (43), we administered IL-13 intraperitoneally and assessed the tuft cell numbers by DCLK1 immunoreactivity 5 days later. We found a clear increase of tracheal tuft cells after IL-13 intraperitoneal injections (Fig. S2H, I). Thus, the dissociation of IL-13 dependent goblet cell hyperplasia from the lack of tuft cell proliferation in the early time points of LTC4+IL-25 synergy likely reflects distinct pathways that regulate goblet cell and tuft cell remodeling in the airways.

In addition to the induction of ILC2-dependent pathways, the cooperative effect of IL-25 and LTC4 also induced CD4+ T cell proliferation, leading to increased numbers in the lung (Fig. 1L and S1H). However, we detected no changes in the number of CD8+ T cells or macrophages, and only a marginal increase in neutrophils (Fig. S1I–K).

Finally, the IL-25/LTC4 increase in lung eosinophilia and inflammatory ILC2 expansion was associated with an expansion of pulmonary DCs (Fig. S1L), particularly the CD301b+ subset with 6 fold increase compared with IL-25 and 11-fold increase compared with LTC4 (Fig. 1M). This is consistent with the reported expression of both CysLT receptors and the IL-25 receptor on DCs and their role in DC activation (42). This provided further evidence that LTC4 and IL-25 activate multiple innate immune cells (ILC2s and DCs) to create an effect that is multiple fold beyond the effect of either mediator alone indicative of true synergy.

To determine if all three CysLTs (LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4) can cooperate with IL-25, we administered each alone and in combination with IL-25. Although all three products could potentiate the effect of IL-25 and increase the number of ILC2s (Fig. S3A), LTC4 was the dominant CysLT to promote the aggregate response of CD301b+ DC expansion (Fig. S3B), eosinophil (Fig. S3C), and CD4+ T cell recruitment (Fig. S3D).

Together, these data demonstrated that two pro-inflammatory and airway remodeling pathways can be triggered by the tuft cell mediators IL-25 and LTC4. The presence of LTC4 dramatically reduced the IL-25 dose required to induce robust type 2 inflammation. Furthermore, tuft cell mediators at low dose, likely similar to those generated physiologically, acted in synergy to activate multiple immune cell subsets including ILC2s and DCs to effectively skew innate inflammation to a type 2 phenotype.

The synergy of LTC4 and IL-25 is cooperatively mediated by CysLT1R and CysLT2R.

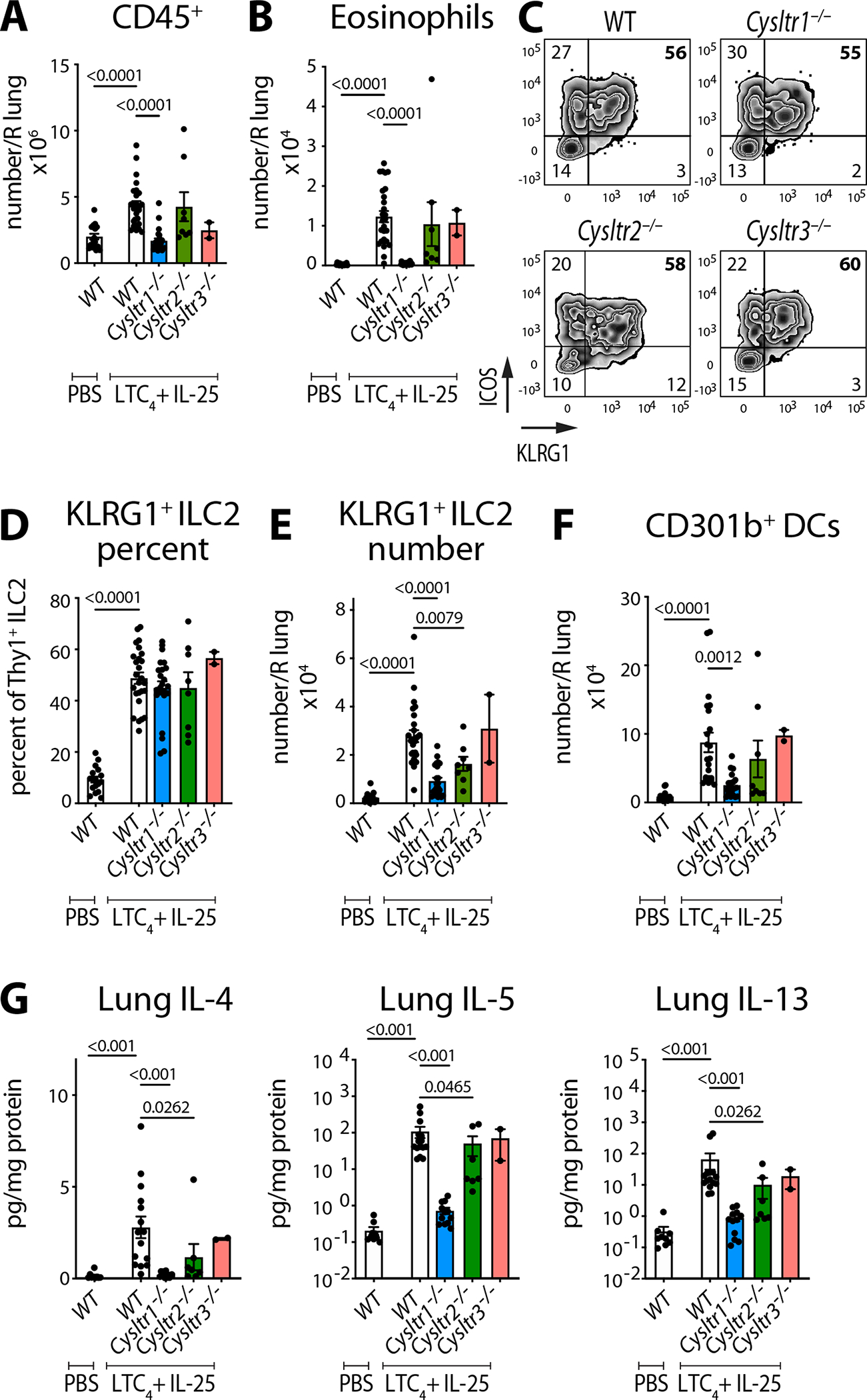

To define the CysLT receptors responsible for mediating the cooperative effect of IL-25 and LTC4, we evaluated the response in three strains of mice, each lacking one of the three CysLT receptors. This allowed us to account for both the direct effect of LTC4 on CysLT1R and CysLT2R and of the biosynthetic products LTD4 and LTE4. We found abrogation of lung inflammation and eosinophil recruitment in Cysltr1−/− mice (Fig. 2A, B) with marginal reduction of eosinophil counts in Cysltr2−/− or Cysltr3−/− mice (Fig. 2A, B). While the percent of KLRG1+ICOS+Thy1+ ILC2s was unaffected, the total number of these inflammatory ILC2s was reduced in both Cysltr1−/− and Cysltr2−/− mice (Fig. 2C–E) consistent with an effect of CysLTs on ILC2 proliferation. Inflammatory CD301b+ DCs were reduced in Cysltr1−/−, with a non-significant trend toward reduction in Cysltr2−/− mice (Fig. 2F). Finally, type 2 cytokines were significantly reduced in both Cysltr1−/− and Cysltr2−/− mice, with a predominant reduction in Cysltr1−/− mice (Fig. 2G). While CysLT1R deletion significantly abrogated the effect of LTC4 and IL-25 on lung eosinophil recruitment and partially reduced the expansion of ILC2s, deleting both LTC4 receptors and the IL-25 receptor IL17RB is likely required to completely abolish the effect of the potent LTC4/IL-25 synergy. Collectively, our data highlighted the complexity of the CysLT system and implicated two receptors in the effects of LTC4 on target cells.

Fig. 2. LTC4 potentiation of IL-25-induced type 2 inflammation depends on CysLT1R and CysLT2R.

WT (C57BL/6), Cysltr1−/−, Cysltr2−/− and Cysltr3−/− mice were given three daily inhalations of LTC4 and IL-25 and assessed 2 days after the last dose (as in Fig. 1A). (A) Number of lung CD45+ cells and (B) number of eosinophils were assessed by FACS. (C) lin−Thy1+ lung ILC2s were evaluated for expression of KLRG1 and ICOS. (D, E) Frequency and number of KLRG1+ ICOS+ ILC2s. (F) Number of CD301b+ DCs. (G) Cytokine protein concentration was determined using multiplex ELISA in lung homogenates and expressed per mg of lung protein. Data are means ± SEM pooled from 3 independent experiments, each dot is a mouse, significant p values indicated for each pairwise comparison: Mann Whitney U test.

ChAT-mediated targeted deletion of Ltc4s selectively ablates tuft cell generation of CysLTs.

To assess the epithelial and immune effector circuit regulated by CysLTs, we generated Ltc4sfl/fl mice to enable conditional deletion of Ltc4s. We opted to use a ChATCre-driven reporter to target airway tuft cells because of its ubiquitous expression in all subsets– olfactory nasal, respiratory nasal and tracheal (12, 16, 44, 45). We first characterized the distribution of ChatCretdTomato cells in situ. Whole mount evaluation of the nasal mucosa demonstrated a high concentration of ChATCretdTomato+ (tuft) cells in the olfactory portion and scattered, solitary cells in the respiratory portion, consistent with the expected distribution of tuft cells in the nose (Fig. S4A)(16, 44). In the lower airways, we found rare ChATCretdTomato+ epithelial (tuft) cells limited to the trachea (Fig. S4A) similar to what we observed in ChAT-eGFP mice (12, 13, 45). As previously reported, we found no ChATCretdTomato+ cells beyond the trachea in the naïve mouse airways (10, 44). By FACS, we identified a distinct population of EpCAMhightdTomato+ cells in the nasal mucosa that accounted for 1–2 % of live cells, similar to our previous findings for frequency of nasal tuft cells (Fig. S4B, C)(16). We then sorted these cells and compared them to EpCAMhighTdTomato− cells from the same mice (Fig. 3A, B).

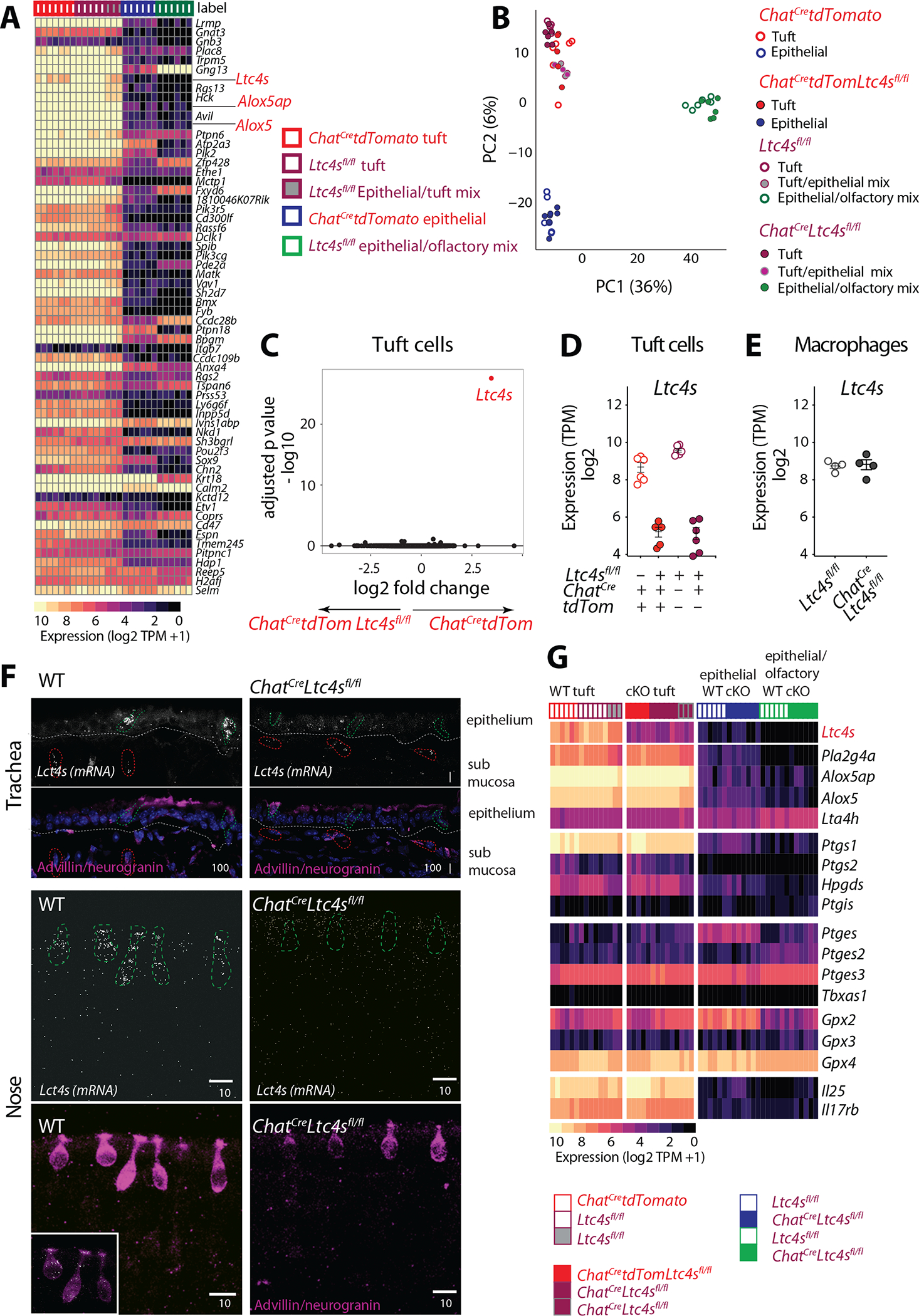

Fig. 3. Essential features of the tuft cell transcriptome are preserved after specific deletion of Ltc4s.

Tuft cells and epithelial cells were isolated from the naïve nasal mucosa of ChatCretdTomato, Ltc4sfl/fl, ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice. Tuft cells were defined as EpCAMhighTomato+ in ChatCretdTomato expressing mice and as EpCAMhighCD45low in mice lacking the Tomato construct and were compared to EpCAMhighCD45− and EpCAMinterm cells. (A) Expression of the tracheal scRNAseq signature (9) genes across tuft and non-tuft epithelial cells in the nose (expression level expressed as log2(TPM + 1). (B) Principal components analysis comparing each of the above populations of cells from ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl, ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl and control ChatCretdTomato and Ltc4sfl/fl mice. (C) Volcano plot displaying significance (y axis, -log10(FDR)) of differential expression (x axis, log2 fold-change) in tuft cells derived fromChatCretdTomato and ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl mice. (D-E) Expression level of Ltc4s in tuft cells (D) derived from Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl, ChatCretdTomato and ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl mice and macrophages (E) from Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice. TPM counts derived from RNAseq analysis using DeSeq2. (F) In situ hybridization with RNAscope probe for Ltc4s (white). Tuft cells were distinguished based on immunoreactivity for advillin and neurogranin (magenta). Representative images of the trachea (top), and nose (bottom) of WT and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice. (Scale bar: indicated in μm). (G) Heatmap of expression (log2(TPM+1), color bar) of genes in the lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase pathway, Il25 and its receptor Il17rb expressed in nasal tuft cells and epithelial cells of the indicated genotypes. cKO, conditional knockout.

Since fluorescent reporter expression could interfere with the function of the target cells, we used a strategy to isolate tuft cells from WT mice as we previously reported based on their high EpCAM and low CD45 expression (16) (Fig. S4D). Because our previous studies and current observations of the shape of tuft cells suggested that >95% of nasal tuft cells are small globular cells (Fig. S4A)(16), we further restricted our gating to the FSClowSSClow subset to exclude any non-tuft EpCAMhigh cells. To validate this subset transcriptionally, we sorted EpCAMhighCD45lowFSClow cells from Ltc4sflfl mice. We also sorted similarly sized EpCAMhigh and EpCAMinterm cells by bulk RNAseq to define the tuft cell transcriptome expression in each subset.

To define the relationship of nasal tuft cells to tracheal tuft cells, we compared the expression profile of EpCAMhighChATCretdTomato cells from ChatCretdTomato mice and EpCAMhighCD45low and EpCAMhighCD45− cells from Ltc4sfl/fl mice to the tracheal tuft cell signature defined by scRNAseq (9). EpCAMhighChATCreTomato+ cells and EpCAMhighCD45low cells were highly enriched for tuft cell-specific transcripts while EpCAMhighCD45− likely represent a less pure mix of tuft cells and epithelial cells (Fig. 3A, Fig. S4F). Although CD45 expression allows for the isolation of a relatively pure population of tuft cells, not all tuft cells express CD45. Both strategies to isolate tuft cells yielded cell populations that highly expressed the tuft cell-specific genes Trpm5, Avil, and Pou2f3 and enzymes in the CysLT biosynthetic cascade, including Alox5, Alox5ap and Ltc4s (Fig. 3A). Thus, the abundant nasal epithelial Chat-expressing cells were highly transcriptionally similar to the rare tracheal tuft cells.

We then crossed the Ltc4sflfl mice to ChatCre and ChatCretdTomato mice to specifically delete Ltc4s in ChAT-expressing cells. Tuft cell numbers in the nose did not differ significantly between WT mice and mice with conditional Ltc4s deletion in tuft cells (Fig. S4C, E). Principal component analysis revealed that tuft cells from WT mice (ChatCretdTomato and Ltc4sflfl) and mice with Ltc4s conditional deletion (ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sflfl and ChatCreLtc4sflfl) clustered together (Fig. 3B, S4F). This highlighted the lack of significant transcriptional alterations in tuft cells or other EpCAM+ populations in the nose due to Ltc4s conditional deletion. Focusing on tuft cells specifically, we found that Ltc4s was the most differentially expressed gene in mice with conditional expression of this gene (Fig. 3C, S4G). Ltc4s expression was 90% reduced in EpCAMhighChATCreTomato+ tuft cells from ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl mice and 95% reduced in the tuft cell enriched EpCAMhighCD45+ cells of ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 3D). Despite the efficiency of Ltc4s deletion, we found very limited change in the homeostatic transcriptional profile of tuft cells besides Ltc4s (Fig. 3C, S4G–H).

Cholinergic neurons are the best characterized Chat-expressing cells (46). Therefore, to account for possible Chat and Ltc4s co-expression in the central and peripheral nervous system, we interrogated published scRNAseq datasets of the mouse central and peripheral nervous system and detected no expression of Ltc4s in the main Chat-expressing populations of the nervous system – motor neurons and visceral motor neurons (Fig. S5A). In the nervous system, Ltc4s was only expressed in immune cell populations. Chat expression in immune cell subsets is reported in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (47) and lung ILC2s (48). Among hematopoietic cells in the airway mucosa, Ltc4s is reported in macrophages, DCs, eosinophils, basophils and mast cells (21–24, 32). To confirm that Ltc4s expression was not affected in macrophages and DCs, we isolated both immune cell subsets from Ltc4sflfl and ChatCreLtc4sflfl mice (Fig. S5B). Macrophages expressed Ltc4s at similarly high levels as tuft cells with no reduction in Ltc4s expression in ChatCreLtc4sflfl mice (Fig. 3E, S5C). DC expression of Ltc4s was lower than that of macrophages and tuft cells, and was not significantly affected in ChatCreLtc4sflfl mice (Fig. S5C).

Next, to better define the specificity of Ltc4s deletion, we evaluated the expression of Ltc4s mRNA in the trachea and nose using in situ hybridization in combination with an antibody cocktail to clearly mark the tuft cells in the airways (Fig. 3F). In the trachea, we detected a high number of Ltc4s mRNA organized “puncta” in the epithelium and very rare Ltc4s expressing cells in the submucosa (Fig. 3F). Far more Ltc4s+ cells were detected in the nasal epithelium than in the trachea, consistent with our observation of higher numbers of tuft cells in the nasal mucosa (Fig. 3F, S4A). Organized nasal epithelial Ltc4s was limited to tuft cells (Fig. 3F). There was a dramatic reduction in epithelial Ltc4s mRNA in both the nose and in the trachea of ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. S5D). Since we detected few Ltc4s+ cells outside of the epithelium in the nose and trachea (Fig. 3F and S5E), we did not quantitate the extraepithelial Ltc4s expression. Taken together, our data indicated that ChATCre-mediated deletion of Ltc4s effectively ablated expression of the Ltc4s transcript in tuft cells without an appreciable effect on other epithelial, neuronal, or immune cell subtypes in the upper and lower airways.

To probe more specifically for an effect of Ltc4s deletion on the expression of other eicosanoid biosynthetic enzymes, we compared the transcriptional profile of tuft cells, epithelial cells, macrophages, and DCs across control (ChatCretdTomato and Ltc4sfl/fl) mice and mice with tuft cell-specific deletion of Ltc4s (ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl). Expression of cyclooxygenase (Ptgs1, Ptgs2, Hpgds, Ptgis) and lipoxygenase (Alox5ap, Alox5, Alox5ap, Lta4h) enzymes in tuft cells was not affected by Ltc4s deletion (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, the expression of Il25 and its receptor, Il17rb, was not reduced by the tuft cell-specific deletion of Ltc4s (Fig. 3G). The homeostatic expression of eicosanoid biosynthetic enzymes in EpCAM+ cells in the nose (Fig. 3G) or in nasal macrophages or DCs also remained unaltered (Fig. S5C). Finally, we investigated whether Alternaria-induced activation of tuft cells might trigger in vivo reprogramming of the eicosanoid biosynthetic transcriptome or other tuft cell mediators, as a similar response is reported in macrophages sensitized to house dust mite (21). To this end, we administered a single intranasal Alternaria inhalation to ChatCretdTomato and ChatCretdTomatoLtc4sfl/fl mice and assessed the tuft cell transcriptional profile 1 day or 3 days after allergen challenge (Fig. S6A). Surprisingly, we found no differential expression changes in any of the eicosanoid biosynthetic transcripts, Il25, Il17rb or Chat (Fig. S6B). Thus, the plasticity of the eicosanoid machinery described in macrophages (21) did not appear to extend to the tuft cell on the transcriptional level. Collectively, we found that ChATCre-mediated deletion of Ltc4s specifically targets Ltc4s expression of tuft cells, with minimal effect on the tuft cell transcriptional profile and with no appreciable effect on Ltc4s expression of neighboring immune cells.

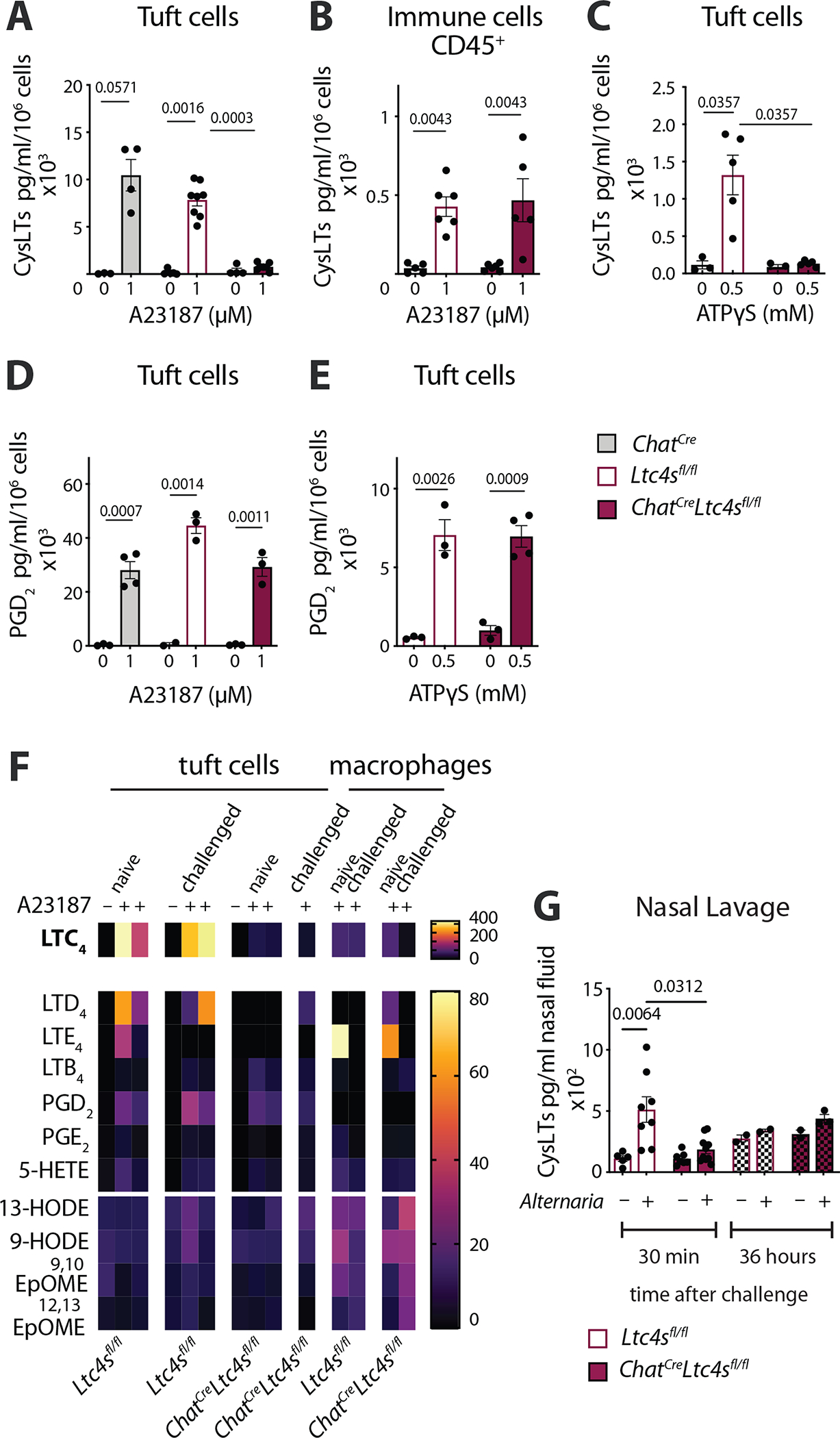

To confirm that the Ltc4s transcript deletion leads to a specific impairment of CysLT generation, we isolated nasal tuft cells from ChatCre, Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice and assessed their responses to Ca2+ ionophore and the physiologic tuft cell stimulus ATP using an ex vivo stimulation assay (16) (Fig. S7A). Tuft cells isolated from both ChatCre and Ltc4sfl/fl mice generated high levels of CysLTs in response to Ca2+ ionophore (A23187), and this response was almost entirely absent in tuft cells from ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 4A). CD45+ cells isolated from Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice stimulated with Ca2+ ionophore generated CysLTs at comparable levels, confirming the specificity of Ltc4s deletion to tuft cells (Fig. 4B). Stimulation with ATP similarly elicited CysLT generation in tuft cells isolated from Ltc4sfl/fl, but not from ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the RNAseq data demonstrating preserved cyclooxygenase biosynthetic transcripts, tuft cells from ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice stimulated with both Ca2+ ionophore and ATP generated PGD2 at levels comparable to tuft cells sorted from Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCre mice (Fig. 4D, E).

Fig. 4. Ltc4s deletion in ChAT-expressing cells selectively ablates CysLT generation by tuft cells.

Tuft cells (EpCAMhighCD45low SSClow) or CD45+ cells were isolated from the nasal mucosa of ChatCre, Ltc4sflfl and ChatCreLtc4sf/lfl mice and stimulated ex vivo with Ca2+ ionophore (A23187) or ATPγS. The concentration of CysLTs or PGD2 in the supernatants was measured by ELISA or lipidomics at 30 min. (A-B) CysLTs in the supernatants of tuft cells (A), or CD45+ cells (B) stimulated with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 measured by ELISA. (C) CysLTs in the supernatant of tuft cells stimulated with ATPγS measured by ELISA. (D-E) PGD2 in the supernatants of tuft cells stimulated with A23187 (D) or ATPγS (E) measured by ELISA. (F) Eicosanoids measured in the supernatants of tuft cells and macrophages by LC-MS (lipidomics). (G) Alternaria was administered intranasally to naïve Ltc4sflfl and ChatCreLtc4sflfl mice and nasal lavage was obtained at 30 min or 36 hours. CysLTs were measured by ELISA after acetone precipitation. Data are means ± SEM, from at least two independent experiments, each dot represents a separate biological replicate representing pooled cells from 1–3 mice, Mann Whitney U-test p values <0.05 are indicated.

To determine how allergen sensitization in the presence or absence of tuft cell Ltc4s affects the eicosanoid biosynthetic capacity in the airways, we administered a single dose of Alternaria to naïve mice, sorted tuft cells and immune cells 36 hours later and stimulated them ex vivo with Ca2+ ionophore. The tuft cell CysLT generating capacity did not change after Alternaria challenge and the ChatCre mediated Ltc4s deletion consistently ablated CysLTs derived from tuft cells (Fig. S7B). We found an inconsistent trend towards higher PGD2 generation in tuft cells sorted from Alternaria-challenged mice, which might be affected by Ltc4s deletion (Fig. S7C).

We then assessed how the CysLT and broader eicosanoid generating capacity of Ltc4s sufficient and deficient tuft cells compares to that of nasal macrophages, lung alveolar macrophages and Alternaria-recruited lung eosinophils by ELISA (Fig. S7B–F), lipidomics (Fig. 4F) and targeted lipid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Tuft cells, nasal and lung macrophages generated the same levels of CysLTs upon maximal stimulation with Ca2+ ionophore (Fig. 4F, S7B, D, E, G). CysLT production by recruited eosinophils was much lower, although notably we did not specifically use eosinophil survival factors in these assays (Fig. S7F, G), which might explain the discrepancy with published literature on CysLT generation by eosinophils. Ltc4s deletion in tuft cells affected the Alternaria-induced reprograming of nasal but not lung macrophages (Fig. S7D, E). When we assessed the levels of eicosanoids using lipidomics, we found that LTC4 generation by tuft cells far exceeded that of macrophages (Fig. 4F) while targeted LC-MS/MS demonstrated similar levels (Fig. S7G) suggesting variability depending on the method used. Importantly, using two different methods of verification, we found that the specificity of ELISA for CysLTs generated by tuft cells was high (Fig. 4A, 4F, S7G). This likely reflects the high selective generation of LTC4 by tuft cells.

Tuft cells are the dominant source of Alternaria-triggered nasal CysLTs in mice with deletion of the tuft cell-specific transcription factor Pou2f3 (16). Here, intranasal Alternaria administered in vivo to Ltc4sfl/fl mice induced generation and luminal release of CysLTs into the nasal lavage fluid 30 min after inhalation while the level of CysLTs detected in the nasal lavage 36 hours later was not different between PBS and Alternaria challenged mice (Fig. 4G). Nasal CysLTs were significantly reduced in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice, confirming that Ltc4s expressed in tuft cells is a critical contributor to the innate nasal LTC4 generated upon allergen recognition (Fig. 4G).

Collectively, these data demonstrated that ChatCre-mediated deletion of Ltc4s specifically ablated the ability of tuft cells to generate CysLTs but did not alter their numbers, transcriptional profile, or potential to sense environmental danger signals and respond with generation of eicosanoids. Furthermore, our data conclusively defined LTC4 as the dominant tuft cell-derived eicosanoid and tuft cells as a major source of LTC4 in the uninflamed nasal mucosa.

Alternaria-induced ILC2 and DC expansion depends on tuft cell-derived CysLTs.

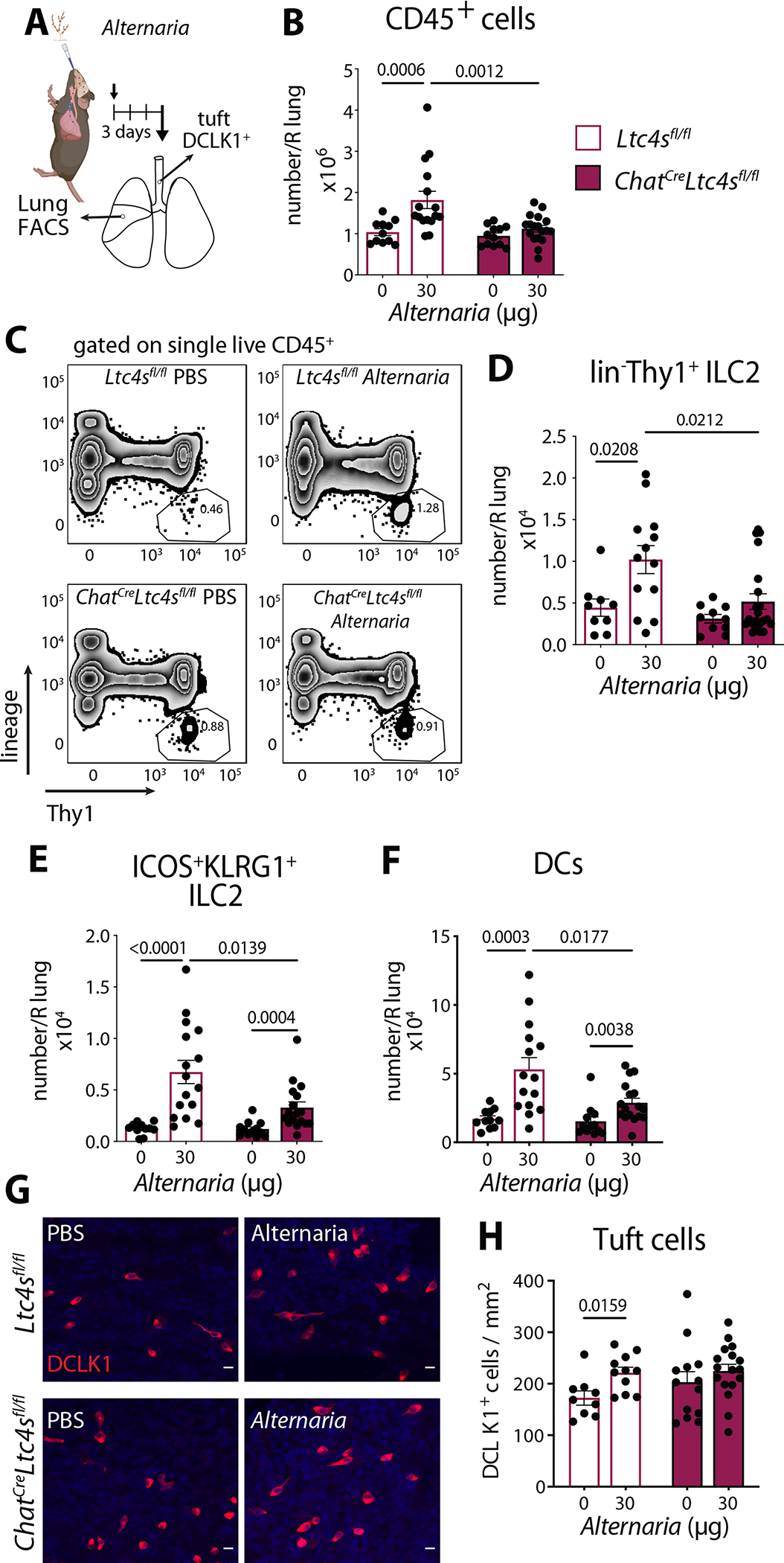

To determine how tuft cell-derived CysLTs regulated the airway immune response to inhaled allergens, we administered the aeroallergen Alternaria intranasally to control mice (Ltc4sfl/fl) and mice with conditional deletion of Ltc4s in tuft cells and evaluated the lung infiltrate 3 days later at a time point we had previously defined to be dependent on CysLTs (13) (Fig. 5A). Alternaria-induced lung inflammation was reduced in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 5B), and surprisingly, we found a decrease in the lin−Thy1+ ILC2s, which in this model are primarily IL-33 driven (49) (Fig. 5C, D). The accumulation of KLRG1+ICOS+ ILC2s was reduced in Alternaria-challenged ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 5E). As observed in our pharmacologic model, we found a reduction in the recruitment of DCs to the lung (Fig. 5F). Thus, in an aeroallergen-triggered airway inflammation model where CysLTs are produced early in the tissue response, the targeted deletion of CysLT generation in tuft cells diminished the local activation and expansion of two critical innate immune cell types.

Fig. 5. Tuft cell derived CysLTs regulate ILC2 expansion in the lung.

(A) Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice were given a single intranasal administration of Alternaria. Tracheal tuft cells and lung inflammation were evaluated 3 days after challenge. (B) Number of CD45+ cells assessed by FACS. (C) Lungs were assessed for frequency of Thy1+ ILC2s (D) Numbers of Thy1+ ILC2s and (E) numbers Thy1+ KLRG1+ ILC2 and (F) numbers of DCs in the lung assessed by FACS. (G) Tracheal tuft cells were identified in whole tracheal mounts by DCLK1 immunoreactivity. Representative images, (scale bar 10 μm) (H) Quantitation of tuft cell numbers in the trachea. Data are means ± SEM, from at least three independent experiments, each dot represents a separate mouse, Mann Whitney U-test p values < 0.05 are indicated.

We considered the possibility that IL-25 generated in response to Alternaria (50) might activate tuft cells directly through IL17RB, which is highly expressed in tuft cells(Fig. 3G), to induce CysLT generation (13, 16). To probe if IL-25 signaling might be disrupted in the absence of endogenous CysLTs, we administered high dose of IL-25 (500 ng sufficient to induce in vivo activation of ILC2s and DCs, Fig. S1A), to WT and mice with germline deletion of Ltc4s (and account for all possible sources of LTC4). Intranasal IL-25 induced ILC2 expansion and activation as well as DC recruitment and tuft cell number increase in the trachea, all of which were intact in Ltc4s−/− mice (Fig. S8A–C). To further probe if the synergy of LTC4 and IL-25 might be disrupted by tuft cell specific deletion of Ltc4s, we administered LTC4 and IL-25 alone or in combination (as in Fig. 1A) to ChatCreLtc4sflfl mice. Lung eosinophilia, ICOS+KLRG1+ ILC2 expansion and DC expansion and lung type 2 cytokines were induced in the ChatCreLtc4sflfl mice cooperatively by LTC4 and IL-25, similar to what we observed in WT mice (Fig. S8D–H). The preserved response to IL-25 in the absence of LTC4S suggests that IL-25 activation of tuft cells through IL17RB for CysLT production is not a major contributor to the tuft cell proinflammatory function.

Alternaria inhalation leads to both lung inflammation and tracheal epithelial remodeling with tuft cell expansion that is dependent on endogenous CysLTs (13). Here, we found that Alternaria inhalation led to expansion of tuft cells in the trachea of WT Ltc4sfl/fl mice, while no tuft cell expansion was observed in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 5G, H). Tuft cell-specific deletion of CysLTs was associated with a higher baseline number of tuft cells, which was consistent with our previous data in Ltc4s−/− mice and points to the tuft cell as the major source of CysLTs that regulate tracheal remodeling (13). Collectively, we demonstrated that endogenously generated CysLTs from tuft cells are required for both inflammation and airway tissue remodeling in response to Alternaria.

Early lung eosinophilia and systemic immune response triggered by Alternaria depend on tuft cell derived CysLTs.

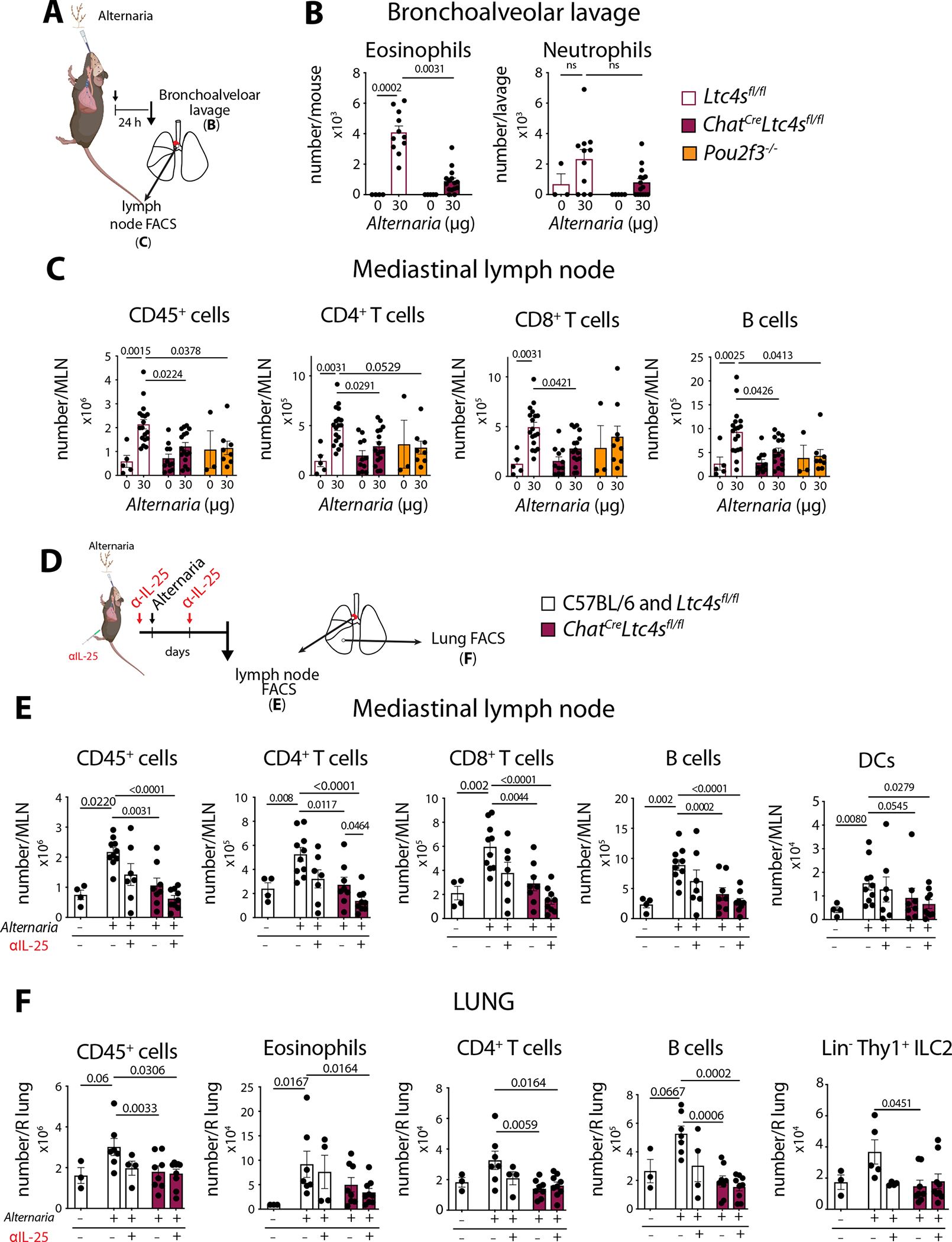

To further define the steps of the local and systemic immune response that depend on tuft cell-derived CysLTs, we evaluated the early response to Alternaria 24 hours after a single intranasal inhalation (4, 16, 51) (Fig. 6A). Alternaria-triggered bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) eosinophilia was induced in Ltc4sfl/fl mice at 24 hours and significantly reduced in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. 6B). The low-level recruitment of neutrophils at this time point was not affected by the deletion of Ltc4s in tuft cells (Fig. 6B). The 70% reduction of BAL eosinophilia in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice was similar to the reduction we reported in tuft cell-deficient Pou2f3 −/− mice (16). Mice with germline deletion of Ltc4s had a similar degree of reduction in eosinophilia to ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice, with marginal effect on the variable rapid lung neutrophil recruitment (Fig. S9A).

Fig. 6. Tuft cell-derived CysLTs in concert with IL-25 contribute to Alternaria-induced early eosinophilia and systemic immunity.

(A) Ltc4sfl/fl, Pou2f3−/− and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice were given a single intranasal dose of Alternaria and were evaluated 24 hours after the challenge. (B) Bronchoalveolar lavage cells were counted, and eosinophils and neutrophils were evaluated using Diff-Quik stain. (C) Mediastinal lymph node (MLN) numbers of CD45+ cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells were evaluated by FACS. (D) Mice were given two intraperitoneal injections of an anti-IL-25 antibody 2 hours before and 22 hours after a single intranasal Alternaria inhalation and were evaluated by FACS 48 hours later (E) Mediastinal lymph node (MLN) numbers of CD45+ cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells and DCs were evaluated by FACS. (F) Lung CD45+ cells, eosinophils, CD4+ T cells, B cells and Thy1+ ILC2s were assessed by FACS. Data are means ± SEM pooled from ≥ 2 independent experiments, each dot is a separate mouse, p values from Mann Whitney U-test p values < 0.05 are indicated.

To evaluate the relative contribution of tuft cell derived CysLTs to the systemic immune response, we also assessed the lymph node for immune cell expansion 24 hours after a single dose of Alternaria. We compared mice with tuft cell-specific deletion of Ltc4s to tuft cell-deficient Pou2f3 −/− mice to account for differences attributable to other tuft cell-derived mediators, including IL-25 and PGD2. The Alternaria-elicited lung draining lymph node hyperplasia was significantly reduced in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl and Pou2f3 −/− mice with reduced accumulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells (Fig. 6C). We found an even larger reduction in lymphocyte recruitment in mice with germline deletion of Ltc4s−/− suggesting that an additional source of CysLTs is engaged by Alternaria (Fig. S9B). Acetylcholine can also contribute to the regulation of Alternaria-elicited lung inflammation (48). To ensure that the effects of ChatCre -mediated Ltc4s deletion here did not result from dysfunctional ChAT, we assessed the Alternaria-induced response in ChatCre mice and found that their ability to mount local lung and systemic responses was not altered (Fig. S9C, D). Thus, tuft cell-derived CysLTs direct both local and systemic allergen-triggered early innate responses.

Finally, to determine if synergy of CysLTs and IL-25 contributed to the integrated Alternaria airway response, we combined antibody inhibition of IL-25 with deletion of tuft cell-derived CysLTs and assessed the lymph node and lung response (Fig. 6D). In the lymph node, the combination of IL-25 antibody blockade and tuft cell CysLT deletion effectively ablated the Alternaria-induced lymph node hyperplasia with additive effects on CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and B cell accumulation (Fig. 6E). Notably, this effect was most pronounced for CD4+ T cells where we found a statistically significant difference of adding IL-25 blockade to CysLT deletion. Importantly, although DC migration was only marginally reduced in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice, adding IL-25 blockade led to a much more significant reduction of DC migration (Fig. 6E). In the lung, the reduction in eosinophils observed in ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice only reached statistical significance when IL-25 antibody was given to mice with tuft cell CysLT deletion (Fig. 6F). There was no additional effect of IL-25 blockade on B or T cell recruitment or on ILC2 accumulation in the lung when compared to CysLT deletion in tuft cells (Fig. 6F).

In summary, we found that despite their relative rarity in the airways, tuft cell derived CysLTs were required for eosinophilic inflammation throughout the lungs and contributed to the development of the systemic immune response to aeroallergens. CysLTs and IL-25 cooperatively regulated the lymph node response to Alternaria while an IL-25 blocking antibody did not reduce the lung inflammation induced by Alternaria.

DISCUSSION:

Tuft cells are sentinel airway epithelial cells positioned to sense inhaled antigens with apical tuft-like projections extending into airway lumen. Their role in immune responses was obscure until they were found to be the dominant source of intestinal IL-25 (38, 40, 52). We recently demonstrated that airway tuft cells are an important source of CysLTs (16). Our findings here reveal that these two tuft cell-derived mediators cooperatively promoted aeroallergen-triggered airway type 2 inflammation. Synergy of IL-25 and LTC4 induced ILC2 proliferation and activation for cytokine production, DC, T cell, and eosinophil recruitment. Although signaling through CysLT1R was necessary for tissue eosinophilia, signaling through CysLT1R and partially through CysLT2R – the latter resistant to available pharmacotherapy – was required for the full cooperative effect of LTC4 and IL-25. Finally, in an integrated Alternaria-elicited aeroallergen model, IL-25 and tuft cell-derived CysLTs cooperated to direct the systemic lymph node response to Alternaria. These findings uncovered how inflammatory lipids, produced by the epithelium, synergize with epithelial ‘alarmin’ cytokines to drive cascades of type 2 inflammation in response to inhaled aeroallergens.

The tuft cell mediator IL-25 induces mild ILC2 activation unless it synergizes with neuromedin U to promote type 2 lung inflammation with 80 % eosinophil predominance (7). Here we identified a new IL-25 promoting pathway: LTC4 cooperates with very low dose of IL-25, that is insufficient to induce inflammation independently. We found that decreasing the dose of inhaled IL-25 led to an exponential drop in the ability of this cytokine to activate ILC2s and DCs in vivo. However, simultaneous exposure to LTC4 and IL-25 triggered a dramatic 47-fold increase in lung eosinophils, proliferation of 80% of inflammatory ILC2s, DC expansion and goblet cell hyperplasia. Hence, tissue signals that lead to the concomitant generation of LTC4 and IL-25 can greatly promote lung inflammation. Airway tuft cells are equipped with the machinery to generated both LTC4 and IL-25 and with the sensing machinery to respond to multiple environmental antigens: bitter tasting agonists and bacterial compounds (53–55), formylated bacterial peptides (56), ATP (16, 53, 57, 58) and allergens (16). Furthermore, upon activation, tuft cells also generate the neuromediator acetylcholine (56, 59). Through these mediators, tuft cells can activate neighboring epithelial cells for antimicrobial release (58), sensory neurons for control of respiratory reflexes and mast cell activation (12, 60) and innate immune cells for cytokine production (39). This highly potent pro-inflammatory program requires tight control to prevent uncontrolled inflammation in response to innocuous inhaled particles.

The temporal and spatial segregation of proinflammatory mediators derived from tuft cells is likely critical to their regulation. Alternaria-elicited CysLTs in the airway lining fluid peaked 30–60 min after intranasal challenge and is undetectable thereafter (16, 50), while IL-25 is detected 12 hours after Alternaria challenge(50). It is likely that the level of IL-25 generated in response to Alternaria early on is much lower to limit its potential to trigger unchecked inflammation. The presence of CysLTs at the early time points after Alternaria inhalation renders these low doses of IL-25 highly inflammatory. Interestingly, IL-25 is selectively secreted on the apical surface of cultured human airway tuft cells (43) and undetectable on the basal surface positing that spatial control might also be critical to maintaining homeostatic segregation. These studies demonstrate that several mediators derived from tissue resident cells promote the effect of IL-25 on type 2 immunity and suggest that IL-25 effects are tightly regulated, likely to limit their pathogenetic potential. Moreover, spatial segregation also plays an important role in directing CysLT responses in the airways. The availability of CysLT ligands in proximity to their respective receptors is tightly controlled by the surface membrane expression of the enzymes that rapidly convert LTC4 to its products LTD4 and LTE4. Furthermore, CysLT1R and CysLT2R receptor expression on immune and structural cells in the vicinity of their short-lived ligands (LTC4 and LTD4) provides an added layer of regulation of the CysLT receptor-ligand interactions.

Our study leaves several questions unanswered. In our pharmacologic model, IL-25 cooperated with LTC4 for ILC2 proliferation after Alternaria. In our allergen-challenge model, CysLTs were required for ILC2 proliferation, but we found no further decrement in ILC2 proliferation by IL-25 antibody blockade. This might be because CysLTs act upstream of IL-25, which is consistent with our previous findings of LTE4 acting upstream of IL-25 (13). Alternatively, the lack of additional effects of IL-25 blockade on lung ILC2s might be explained by the dominant effect of IL-33 in Alternaria-induced lung inflammation and its cooperation with LTC4 (3, 5). Notably, IL-33 can be released from platelets in response to LTC4 activation of CysLT2R (41, 61–63). This loop might serve as a bypass of the IL-25/LTC4 synergy in the lung. The specific interactions of epithelial cytokines with CysLTs in the innate and chronic phase of allergic inflammation in the complex models of aeroallergen-induced innate and adaptive responses remain to be fully explored.

In contrast to the limited effect of IL-25+LTC4 synergy on lung ILC2 proliferation, we found that the lymph node response to Alternaria is almost completely ablated when both CysLTs and IL-25 are inhibited. This is likely due the cooperative effect of IL-25 and LTC4 on DC migration to the draining lymph nodes. DC activation by tuft cells might be direct as they respond to both CysLTs and IL-25 (34, 36, 37). Alternatively, this synergy might be mediated indirectly through sensory neuron-derived substance P (8) or CGRP (64), both of which can activate DCs for lymph node migration. Importantly, tight functional connections to substance P+ and CGRP+ sensory nerves are among the best described features of both tracheal tuft (brush) cells (12) and nasal tuft (solitary chemosensory) cells (60). Furthermore, CysLT2R is highly expressed in airway innervating sensory nerves and is directly activated by LTC4 (65–68) providing a possible tuft cell-sensory neuron-DC axis to promote type 2 inflammation in the airways.

Our study provides insights into how airway tuft cells promote allergic inflammation, but it does not locate the site of allergen recognition and initiation of the immune response. While the lung is the most accessible organ to study airway inflammation, most allergic airway inflammation models use intranasal instillation of allergens. Tuft cells are much more abundant in the nose (16, 44), rare in the naïve mouse trachea (~0.1% of epithelial cells) (13), and extremely rarely found in the naïve mouse lung (10). How nasal olfactory and respiratory versus tracheal tuft cells contribute to DC conditioning for Th2 priming directly and indirectly (33, 34) remains to be explored.

Our lipidomics analysis demonstrated that LTC4 was by far the most dominant eicosanoid generated by tuft cells and an important contributor to the overall CysLT generating capacity in naïve airways. Re-programmed macrophages, recruited eosinophils, and expanded mast cells likely account for the bulk of CysLTs generated in the chronic phase of allergic inflammation but tuft cells are a critical source in the early phase of allergen recognition. Unexpectedly, we found that tuft cell expression of eicosanoid biosynthetic enzymes and generation of eicosanoids is unchanged after activation with Alternaria. Macrophages are highly transcriptionally plastic after house dust mite sensitization (21). Further studies are needed to determine if tuft cell derived PGD2, in the setting of established inflammation, critically contributes to type 2 inflammation or modulates epithelial proliferation.

While the pharmacological synergy of IL-25 with LTC4 for type 2 immunity suggested that both are central mediators produced by tuft cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that LTC4 from tuft cells might have broader effects on immune responses beyond this specific interaction. Tuft cells are also prominent sources of acetylcholine, which can be generated in response to formylated peptides (56). A population of Chat-expressing ILC2s that also express cholinergic receptors is specifically induced by Alternaria in the lung (48). Thus, an interaction between acetylcholine and CysLTs might further augment the activation of ILC2s. Interestingly, although both Chat and Ltc4s are widely expressed in diverse immune subsets, only tuft cells uniquely co-express both markers, further expanding the possibility of a functional importance of this co-localization.

In summary, our data provided evidence of a system of allergen-triggered responses in the airways. Notably, in mouse models, the most dramatic increase in airway tuft cell numbers is found in the recovery phase of influenza infection (11). In human airway diseases, CysLTs are found in the BAL of infants with RSV bronchiolitis (69–71) and IL-25 is induced by viral exacerbations of asthma (72). Beyond allergen recognition, this system may also play decisive roles in other airway diseases associated with IL-25 and CysLT production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The aims of this study were to define the role of two of the major tuft cell-derived mediators – LTC4 and IL-25 in driving type 2 inflammation in the airways. We used a pharmacologic model to evaluate the lung inflammation induced by LTC4 or IL-25 alone or in combination. Using mice with receptor-specific deletion for each CysLT receptor, we identified the two receptors responsible for mediating this response. We then developed and characterized transcriptionally a new mouse model with tuft cell-specific deletion of LTC4 generation – ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl to specifically characterize the dependence of a mouse model of allergen-induced inflammation on tuft cell-derived CysLTs.

Detailed descriptions of Methods and Materials are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Experimental Models and Mice

The use of mice for these studies was in accordance with review and approval by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Mice were randomly assigned to treatment groups after matching for sex, age and genotype.

Ltc4sfl/fl mice were generated by Ingenious targeting laboratory (Ronkonkoma, NY). Homozygous Ltc4sfl/fl mice were crossed with Chat-IRES-Cre mice to generate ChatCre+Ltc4sfl/fl mice. ChatCre+Ltc4sfl/fl were also mated to ROSAtm9tdTomato mice to generate ChatCre+ −tdTomato+ − and ChatCre+ −tdTomato+ −Ltc4sfl/fl mice.

Aeroallergen, cytokine and lipid mediator challenge protocols

Mice were given a single intranasal inhalation of Alternaria alternata (Greer) culture filtrate and euthanized at the following time points: 1 hour for nasal lavage to assess eicosanoids (Fig. 4); 2) at 24 hours for BAL assessment of inflammation or mediastinal lymph node assessment of DC recruitment and lymphocyte numbers (Fig. 6); and at 3) 72 hours for lung and tracheal harvesting. (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). In a set of experiments, mice were given two doses of LEAF-purified anti-IL-25 antibody or IgGk1 isotype control (Biolegend) intraperitoneally 6 hours before and 18 hours after Alternaria challenge at a dose of 100 mg/mouse (Fig. 6D–F) and mice were euthanized 36 hours after the allergen challenge for lymph node and lung assessment.

For CysLT (and IL-25 synergy experiments (Figures 1 and 2), LTC4, LTD4 or LTD4, IL-25 or the combination of LTC4, LTD4 or LTD4 and IL-25 were administered intranasally daily for three consecutive days. The lung and trachea were harvested 48 hours after the last intranasal administration (Fig. 1, Fig. S1, S2, S3).

In a set of experiments, mice were given a single dose of mouse IL-13 intraperitoneally and tuft cell numbers were assessed in the trachea after 5 days (Biolegend) (Fig. S2H, I).

Single cell preparations for evaluation of inflammation

For evaluation of lung inflammation, lungs were perfused, homogenized and digested with collagenase IV and dispase in the presence of DNAse to obtain single cell suspensions. Cell surface receptor expression was assessed as previously described (13). To evaluate for proliferation, lung cells were first incubated with cell surface antibodies, then fixed and permeabilized using the True-Nuclear™ Transcription Factor Buffer Set (Biolegend), followed by incubation with a rat anti-Ki67 antibody (Invitrogen, clone SolA15) (Fig. 1F, G, S1D, F, G). In selected experiments, lung single-cell suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 4 h with Golgi-Plug (BD Biosciences) prior to intracellular staining with a mix of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 cytokine antibodies (Fig. 1H, I, S2A, B). Lymph nodes were dissociated using a metal mesh and digested with collagenase IV, dispase and DNAse for 30 min prior to cell surface staining for T and B lymphocytes and DCs. Flow cytometry was performed on BD LSR Fortessa™ Cell Analyzer (Fig. 6C, E, S9B, C).

Cytokine detection in whole lung

Protein was extracted after homogenization of the lung with T-PER protein extraction buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors(cOmplete™, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Sigma Aldrich). After assessment of protein concentration with a bicinchonic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (ThermoFisher), the cytokine concentrations were measured with LEGENDplex mouse T-helper Cytokine Panel (Biolegend, including IFN-γ, IL-5, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-4, IL-10, IL-9, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-13) and analyzed on a BD LSR Fortessa™ Cell Analyzer (Fig. 2G, S2C–E).

Single cell preparations for ex vivo stimulation and RNA sequencing

For single-cell preparations of tuft cells from the nasal mucosa, mouse snouts were processed with dispase solution, followed by mechanical separation and a second digestion with a papain containing tyrode-based solution (16, 73). Tuft cells were defined as as EpCAMhighTomato+ in ChatCreTomato and ChatCreTomatoLtc4sfl/fl mice (Fig. S4B) EpCAMhighCD45neg/lowSSClow (Fig. S4D) in Ltc4sfl/fl and ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice.

To isolate macrophages and DCs, the snouts were enzymatically dissociated with a PBS-based solution containing collagenase IV, dispase and DNAse. Macrophages were defined as CD11b+CD11c+SiglecF+ and DCss as SiglecF−CD11b+CD11c+MHCII+ (Fig. S5B).

For RNA sequencing, at least 500 but no more than 1300 tuft cells, macrophages or DCs from 1 naïve digested mouse snout were sorted into TCL buffer (Qiagen) supplemented with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco).

Ex vivo stimulation of tuft cells, macrophages and eosinophils

Sorted tuft cells were plated at concentration 400,000 cells/ml in 200 μL of epithelial cell proliferation media. Hematopoietic cells were plated as 66,000–200,000 cells/ml for nasal macrophages, 0.5 ×106 cells/ml for lung macrophages and 66,000–1.3 ×106 cells/ml for lung eosinophils in R10 media. The cells were rested for 1–18 hours, and then stimulated with 1 mM A23187 or 0.5 mM ATPγS in 50 μl of HBSS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 30 min. The supernatants were harvested for lipid mediator analysis. No additional evaluation for viability was performed before or after stimulation.

In situ Hybridization (RNAscope) and mRNA quantitation

For in situ hybridization, we used RNAscope® Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit v2 (ACD) assay following the manufactureŕs instructions. The probe to Lct4s was custom-made by ACD (Cat. No. 1092591-C1) and it targets exons 1–5 of the Ltc4s transcript (nucleotides 98–534 of NM_008521.2). After in situ hybridization, sections were rinsed were stained with a mix of anti-advillin (Novus Biologicals) and anti-neurogranin (Abcam) antibodies and imaged on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope. To quantify expression of transcripts, the images were applied a threshold until only puncta signal was observed. The integrated density was measured as a method to quantify total mRNA puncta. In the case of nasal tissue, the signal was measured only in tuft cells, as revealed by the expression of Advillin/Neurogranin, thus the quantification represents mRNA per cell. In the case of the trachea, a random area of the tracheal epithelium, as reflected by DAPI stain, was quantified for mRNA puncta and the values represent mRNA per area of tracheal epithelium.

CysLT and PGD2 detection

CysLTs and other eiconsanoids were assessed by three methods 1) CysLT and PGD2 levels were measured in nasal lavages and in supernatants of cells stimulated ex vivo by Cysteinyl Leukotriene ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, 500390) and Prostaglandin D2 ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, 512031). 2) Lipid analysis for eicosanoids was performed at the UCSD Lipidomics Core (https://www.ucsd-lipidmaps.org/home) (74, 75). 3) Targeted analysis for CysLTs was performed at the Harvard Mass Spectrometry Facility using an ultimate 3000 LC coupled with a Q-exactive plus mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher).

Histochemistry, immunofluorescence and quantitative assessment of goblet cell and tuft cell numbers

Goblet cells were quantitated in PAS stained 2.5 μm thick sections of glycolmethacrylate-embedded lungs and eosinophil recruitment was visualized with Congo red reactivity.

For evaluation of tracheal tuft cells, tracheas were incubated with an anti-DCLK1 antibody (Abcam) for 7 days post fixation and the immunoreactivity was identified with Alexa 546 conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen) with Hoechst 33342 as a nuclear dye. Quantitation of tuft cells in whole mounts was as previously described (13).

Low input RNA sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed at the Broad Institute Genomics Labs using low-input eukaryotic Smart-seq2. Smart-seq2 libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 using a High Output kit to generate 2 × 38 bp reads (plus dual index reads). BCL files were converted to merged, de-multiplexed FASTQ files using the Illumina Bcl2Fastq software pack- age v.2.17.1.14. Paired-end reads were mapped to the UCSC mm10 mouse transcriptome using Bowtie57. Gene expression levels were quantified as transcript-per-million (TPM) values by RSEM58 v.1.2.3 in paired-end mode. Computational pipelines for RNA seq analysis were implemented as described elsewhere (9, 19). Tuft cell marker genes were derived from the ‘consensus’ signature defined with single-cell RNA sequencing (9). Heatmaps were generated using the ‘pheatmap’ R package. Pairwise Pearson correlations between all samples were calculated using the R function ‘cor’ from the ‘stats’ package (Fig. S3D). Expression data for mouse neuronal populations was downloaded from the Mouse Brain Atlas (http://mousebrain.org/downloads.html) and visualized using the ‘ggplot2’ package in R.

Statistics

Analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism software (version 8). Nonparametric two-sided Mann–Whitney and unpaired T tests were used to determine significance in pairwise comparison of responses in the in vivo and ex vivo stimulation models. For samples that did not follow normal distribution (D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test), we used a Mann-Whitney test to calculate the p values. For experiments with ≧4 group comparisons, the overall significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA and pairwise comparison was performed with Kruskall-Wallis tests with Dunn’s correction. A value of p <0.05 was considered significant. Sample sizes were not predetermined by statistical methods.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. LTC4 and IL-25 synergize for airway type 2 lung inflammation.

Fig. S2. Lung cytokine profile and tuft cell numbers after LTC4 and IL-25 inhalation.

Fig. S3. CysLT synergy with IL-25 to promote lung inflammation in vivo is primarily driven by LTC4.

Fig. S4. The transcriptional profile of tuft cells from ChatCreLtc4sfl/fl mice is unaltered.

Fig. S5. Chat and Ltc4s are not co-expressed in neurons or immune cells.

Fig. S6. The eicosanoid transcriptional profile of tuft cells is unaltered before and after Alternaria sensitization.

Fig. S7. Ltc4s deletion does not alter the eicosanoid generating capacity of airway immune cells.

Fig. S8. Ltc4s deletion does not alter the airway responses to IL-25.

Fig. S9. Lung and lymph node responses to Alternaria in ChatCre and Ltc4s−/− mice.

Table S1. Reagents

Table S2. Raw data in excel file

Acknowledgements:

We thank Adam Chicoine from Brigham and Women’s Hospital Human Immunology Center Flow Core for his help with FACS sorting. We are grateful to Charles Vidoudez and Sunia Trauger from the Harvard Center for Mass Spectrometry and Oswald Quehenberger from the University of California San Diego Lipidomics Core for their expertise and help setting up the mass spectrometry assays for CysLTs and lipidomics assays. We are also thankful to Lisa Goodrich at the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School for providing reagents and infrastructure for in situ hybridization. Pou2f3−/− mice are available from Dr. Matsumoto under a material transfer agreement with the Monell Chemical Senses Center. Schematic diagrams were created using BioRender.

Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health grant K08 AI132723 (to LGB), 1R21AI154345 (to LGB and ALH), 5T32AI007306 (to SU), R01AI078908, R37AI052353, R01AI136041, R01HL136209 (to JAB), U19 AI095219 (to NAB, JAB), R01AI134989 (to NAB), AAAAI Foundation Faculty Development Award and Joycelyn C. Austen Fund for Career Development of Women Physician Scientists (to LGB), Parker B. Francis Fellowship (to ALH) and a generous donation by the Vinik family (to LGB).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS:

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and Materials Availability.

The RNA sequencing data for this study have been deposited to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible under accession number GSE188820. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES:

- 1.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H, Allergens and the airway epithelium response: gateway to allergic sensitization. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 134, 499–507 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammad H, Lambrecht BN, Barrier Epithelial Cells and the Control of Type 2 Immunity. Immunity 43, 29–40 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Moltke J, O’Leary CE, Barrett NA, Kanaoka Y, Austen KF, Locksley RM, Leukotrienes provide an NFAT-dependent signal that synergizes with IL-33 to activate ILC2s. Journal of Experimental Medicine 214, 27–37 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty TA, Khorram N, Lund S, Mehta AK, Croft M, Broide DH, Lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells express cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1, which regulates TH2 cytokine production. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 132, 205–213 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund SJ, Portillo A, Cavagnero K, Baum RE, Naji LH, Badrani JH, Mehta A, Croft M, Broide DH, Doherty TA, Leukotriene C4 Potentiates IL-33-Induced Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Activation and Lung Inflammation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 199, 1096–1104 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbot S, Abdulnour RE, Burkett PR, Lee S, Cronin SJ, Pascal MA, Laedermann C, Foster SL, Tran JV, Lai N, Chiu IM, Ghasemlou N, DiBiase M, Roberson D, Von Hehn C, Agac B, Haworth O, Seki H, Penninger JM, Kuchroo VK, Bean BP, Levy BD, Woolf CJ, Silencing Nociceptor Neurons Reduces Allergic Airway Inflammation. Neuron 87, 341–354 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallrapp A, Riesenfeld SJ, Burkett PR, Abdulnour RE, Nyman J, Dionne D, Hofree M, Cuoco MS, Rodman C, Farouq D, Haas BJ, Tickle TL, Trombetta JJ, Baral P, Klose CSN, Mahlakoiv T, Artis D, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Chiu IM, Levy BD, Kowalczyk MS, Regev A, Kuchroo VK, The neuropeptide NMU amplifies ILC2-driven allergic lung inflammation. Nature 549, 351–356 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perner C, Flayer CH, Zhu X, Aderhold PA, Dewan ZNA, Voisin T, Camire RB, Chow OA, Chiu IM, Sokol CL, Substance P Release by Sensory Neurons Triggers Dendritic Cell Migration and Initiates the Type-2 Immune Response to Allergens. Immunity 53, 1063–1077 e1067 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montoro DT, Haber AL, Biton M, Vinarsky V, Lin B, Birket SE, Yuan F, Chen S, Leung HM, Villoria J, Rogel N, Burgin G, Tsankov AM, Waghray A, Slyper M, Waldman J, Nguyen L, Dionne D, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Tata PR, Mou H, Shivaraju M, Bihler H, Mense M, Tearney GJ, Rowe SM, Engelhardt JF, Regev A, Rajagopal J, A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature 560, 319–324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tizzano M, Cristofoletti M, Sbarbati A, Finger TE, Expression of taste receptors in solitary chemosensory cells of rodent airways. BMC pulmonary medicine 11, 3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rane CK, Jackson SR, Pastore CF, Zhao G, Weiner AI, Patel NN, Herbert DR, Cohen NA, Vaughan AE, Development of solitary chemosensory cells in the distal lung after severe influenza injury. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 316, L1141–L1149 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krasteva G, Canning BJ, Hartmann P, Veres TZ, Papadakis T, Muhlfeld C, Schliecker K, Tallini YN, Braun A, Hackstein H, Baal N, Weihe E, Schutz B, Kotlikoff M, Ibanez-Tallon I, Kummer W, Cholinergic chemosensory cells in the trachea regulate breathing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 9478–9483 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bankova LG, Dwyer DF, Yoshimoto E, Ualiyeva S, McGinty JW, Raff H, von Moltke J, Kanaoka Y, Frank Austen K, Barrett NA, The cysteinyl leukotriene 3 receptor regulates expansion of IL-25-producing airway brush cells leading to type 2 inflammation. Science Immunology 3, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finger TE, Bottger B, Hansen A, Anderson KT, Alimohammadi H, Silver WL, Solitary chemoreceptor cells in the nasal cavity serve as sentinels of respiration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 8981–8986 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen A, Finger TE, Is TrpM5 a reliable marker for chemosensory cells? Multiple types of microvillous cells in the main olfactory epithelium of mice. BMC Neurosci 9, 115 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ualiyeva S, Hallen N, Kanaoka Y, Ledderose C, Matsumoto I, Junger WG, Barrett NA, Bankova LG, Airway brush cells generate cysteinyl leukotrienes through the ATP sensor P2Y2. Sci Immunol 5, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita J, Ohmoto M, Yamaguchi T, Matsumoto I, Hirota J, Skn-1a/Pou2f3 functions as a master regulator to generate Trpm5-expressing chemosensory cells in mice. PloS one 12, e0189340 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadjsombati MS, McGinty JW, Lyons-Cohen MR, Jaffe JB, DiPeso L, Schneider C, Miller CN, Pollack JL, Nagana Gowda GA, Fontana MF, Erle DJ, Anderson MS, Locksley RM, Raftery D, von Moltke J, Detection of Succinate by Intestinal Tuft Cells Triggers a Type 2 Innate Immune Circuit. Immunity 49, 33–41 e37 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haber AL, Biton M, Rogel N, Herbst RH, Shekhar K, Smillie C, Burgin G, Delorey TM, Howitt MR, Katz Y, Tirosh I, Beyaz S, Dionne D, Zhang M, Raychowdhury R, Garrett WS, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Shi HN, Yilmaz O, Xavier RJ, Regev A, A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature 551, 333–339 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austen KF, Maekawa A, Kanaoka Y, Boyce JA, The leukotriene E4 puzzle: finding the missing pieces and revealing the pathobiologic implications. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 124, 406–414; quiz 415–406 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henkel FDR, Friedl A, Haid M, Thomas D, Bouchery T, Haimerl P, de Los Reyes Jimenez M, Alessandrini F, Schmidt-Weber CB, Harris NL, Adamski J, Esser-von Bieren J, House dust mite drives proinflammatory eicosanoid reprogramming and macrophage effector functions. Allergy 74, 1090–1101 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis RA, Austen KF, Drazen JM, Clark DA, Marfat A, Corey EJ, Slow reacting substances of anaphylaxis: identification of leukotrienes C-1 and D from human and rat sources. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 77, 3710–3714 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandeira-Melo C, Weller PF, Eosinophils and cysteinyl leukotrienes. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids 69, 135–143 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshimoto T, Soberman RJ, Lewis RA, Austen KF, Isolation and characterization of leukotriene C4 synthetase of rat basophilic leukemia cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 82, 8399–8403 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laidlaw TM, Kidder MS, Bhattacharyya N, Xing W, Shen S, Milne GL, Castells MC, Chhay H, Boyce JA, Cysteinyl leukotriene overproduction in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease is driven by platelet-adherent leukocytes. Blood 119, 3790–3798 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimoto T, Soberman RJ, Spur B, Austen KF, Properties of highly purified leukotriene C4 synthase of guinea pig lung. The Journal of clinical investigation 81, 866–871 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch KR, O’Neill GP, Liu Q, Im DS, Sawyer N, Metters KM, Coulombe N, Abramovitz M, Figueroa DJ, Zeng Z, Connolly BM, Bai C, Austin CP, Chateauneuf A, Stocco R, Greig GM, Kargman S, Hooks SB, Hosfield E, Williams DL Jr., Ford-Hutchinson AW, Caskey CT, Evans JF, Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene CysLT1 receptor. Nature 399, 789–793 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster HR, Fuerst E, Branchett W, Lee TH, Cousins DJ, Woszczek G, Leukotriene E4 is a full functional agonist for human cysteinyl leukotriene type 1 receptor-dependent gene expression. Sci Rep 6, 20461 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heise CE, O’Dowd BF, Figueroa DJ, Sawyer N, Nguyen T, Im DS, Stocco R, Bellefeuille JN, Abramovitz M, Cheng R, Williams DL Jr., Zeng Z, Liu Q, Ma L, Clements MK, Coulombe N, Liu Y, Austin CP, George SR, O’Neill GP, Metters KM, Lynch KR, Evans JF, Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry 275, 30531–30536 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanaoka Y, Maekawa A, Austen KF, Identification of GPR99 protein as a potential third cysteinyl leukotriene receptor with a preference for leukotriene E4 ligand. The Journal of biological chemistry 288, 10967–10972 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR Jr., Leukotrienes. The New England journal of medicine 357, 1841–1854 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett NA, Maekawa A, Rahman OM, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y, Dectin-2 recognition of house dust mite triggers cysteinyl leukotriene generation by dendritic cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 182, 1119–1128 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke DL, Davis NH, Campion CL, Foster ML, Heasman SC, Lewis AR, Anderson IK, Corkill DJ, Sleeman MA, May RD, Robinson MJ, Dectin-2 sensing of house dust mite is critical for the initiation of airway inflammation. Mucosal immunology 7, 558–567 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett NA, Rahman OM, Fernandez JM, Parsons MW, Xing W, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y, Dectin-2 mediates Th2 immunity through the generation of cysteinyl leukotrienes. The Journal of experimental medicine 208, 593–604 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U, Williamson PR, Urban JF Jr., Paul WE, IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nature immunology 16, 161–169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claudio E, Tassi I, Wang H, Tang W, Ha HL, Siebenlist U, Cutting Edge: IL-25 Targets Dendritic Cells To Attract IL-9-Producing T Cells in Acute Allergic Lung Inflammation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 195, 3525–3529 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claudio E, Wang H, Kamenyeva O, Tang W, Ha HL, Siebenlist U, IL-25 Orchestrates Activation of Th Cells via Conventional Dendritic Cells in Tissue to Exacerbate Chronic House Dust Mite-Induced Asthma Pathology. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 203, 2319–2327 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Moltke J, Ji M, Liang HE, Locksley RM, Tuft-cell-derived IL-25 regulates an intestinal ILC2-epithelial response circuit. Nature 529, 221–225 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGinty JW, Ting HA, Billipp TE, Nadjsombati MS, Khan DM, Barrett NA, Liang HE, Matsumoto I, von Moltke J, Tuft-Cell-Derived Leukotrienes Drive Rapid Anti-helminth Immunity in the Small Intestine but Are Dispensable for Anti-protist Immunity. Immunity 52, 528–541 e527 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Dardalhon V, Cesses P, Garnier L, Pouzolles M, Brulin B, Bruschi M, Harcus Y, Zimmermann VS, Taylor N, Maizels RM, Jay P, Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature 529, 226–230 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu T, Kanaoka Y, Barrett NA, Feng C, Garofalo D, Lai J, Buchheit K, Bhattacharya N, Laidlaw TM, Katz HR, Boyce JA, Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease Involves a Cysteinyl Leukotriene-Driven IL-33-Mediated Mast Cell Activation Pathway. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tworek D, Smith SG, Salter BM, Baatjes AJ, Scime T, Watson R, Obminski C, Gauvreau GM, O’Byrne PM, IL-25 Receptor Expression on Airway Dendritic Cells after Allergen Challenge in Subjects with Asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 193, 957–964 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]