Abstract

Background

Interleukin (IL)-17 family is a group of six cytokines that plays a central role in inflammatory processes and participates in cancer progression. Interleukin-17A has been shown to have mainly a protumorigenic role, but the other members of the IL-17 family, including IL-17F, have received less attention.

Methods

We applied systematic review guidelines to study the role of IL-17F, protein and mRNA expression, polymorphisms, and functions, in cancer. We carried out a systematic search in PubMed, Ovid Medline, Scopus, and Cochrane libraries, yielding 79 articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Results

The findings indicated that IL-17F has both anti- and protumorigenic roles, which depend on cancer type and the molecular form and location of IL-17F. As an example, the presence of IL-17F protein in tumor tissue and patient serum has a protective role in oral and pancreatic cancers, whereas it is protumorigenic in prostate and bladder cancers. These effects are proposed to be based on multiple mechanisms, such as inhibition of angiogenesis, vasculogenic mimicry and cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and aggravating the inflammatory process. No solid evidence emerged for the correlation between IL-17F polymorphisms and cancer incidence or patients’ prognosis.

Conclusion

IL-17F is a multifaceted cytokine. There is a clear demand for more well-designed studies of IL-17F to elucidate its molecular mechanisms in different types of cancer. The studies presented in this article examined a variety of different designs, study populations and primary/secondary outcomes, which unfortunately reduces the value of direct interstudy comparisons.

Keywords: IL-17F, cancer, Systematic review, Lymphocytes, Prognostic, Polymorphism

Introduction

Cancer caused almost 9.6 million deaths globally in 2018 [1]. The incidence of cancers can be decreased to some extent by avoiding known risk factors, such as tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption [2], but several unknown environmental, genetic, and epigenetic reasons likely exist for cancer progression. Thus, safer and more effective treatments are continuously being sought for different cancer types.

Cancer biomarkers are biological compounds detectable in tissues or body fluids. They are applied for the prognosis of various cancers and to predict the outcome and efficiency of treatments [3]. Cytokines, one group of biomarkers, are proteins that participate in cell signaling and mediate innate and adaptive immune system responses. Some cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-15, seem to also be relevant in cancer immunotherapy [4].

Interleukin (IL)-17F is a member of the IL-17 cytokine family, which contains six members (IL-17A-F). IL-17F is produced by several cells, including activated CD4+ T cells, monocytes, basophils, and mast cells [5]. IL-17A and IL-17F share the greatest homology with each other, and they have two common receptors: IL-17RA and IL-17RC. IL-17A was the first IL-17 cytokine identified, and it plays important roles in host defense, inflammation, allograft rejection, and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis [6–8]. IL-17A has mainly been reported as a protumorigenic factor, however some studies showed it as an antitumorigenic cytokine [6, 9]. Other members, including IL-17F, have been far less extensively studied, also in cancer [10].

Here, we systematically collected literature concerning the expression, polymorphisms, and function of IL-17F in various cancers and reviewed the role of IL-17F as a pro- or antitumorigenic molecule. We also analysed data related to the proposed molecular mechanisms by which IL-17F affects cancer development and progression.

Methods

This review study was registered at the international prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO under registration number CRD42020186465.

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and conducted a search using PubMed, Ovid Medline, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases. We searched the terms interleukin-17F (interleukin 17f OR il 17f OR interleukin-17f OR il-17f) and cancer (cancer OR neoplasm* OR carcinoma* OR malignan* OR tumo?r* OR sarcoma* OR leukemia* OR lymphoma* OR adenocarcinoma*), with an asterisk (*) indicating truncation and a question mark (?) indicating wildcard characters, from titles, abstracts, and keywords. We conducted two searches, the first one was on the 15th of May 2020, and the second search covered the period from 16th of May 2020 until 9th of October 2021.

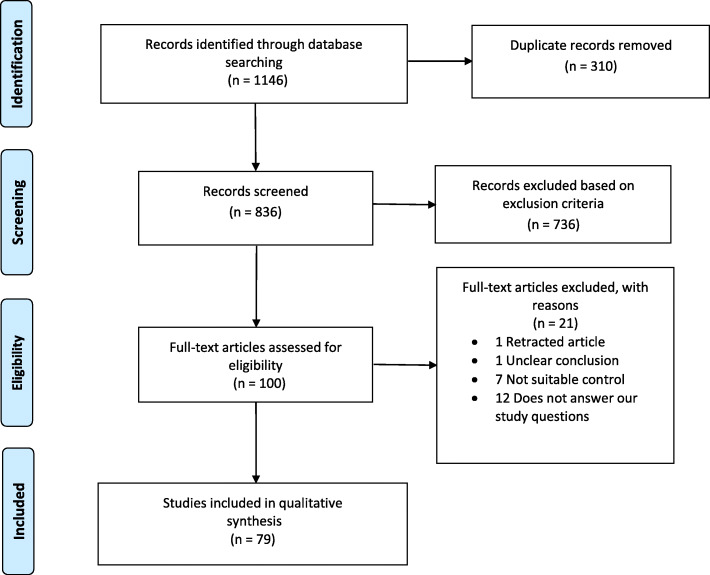

We identified a total of 1146 records through database searching and removed 310 duplicates, leaving 836 records for screening. Three researchers (R.A. and T.M. or A.A.) screened the records independently and were blinded to each other’s decisions. Disagreements in included and excluded articles were resolved by reaching a consensus between the researchers. We excluded 736 records because they were reviews, case reports, letters, book chapters, conference abstracts, written in languages other than English, or irrelevant to our review. In addition, we found a few more duplicates during manual record screening. We assessed 100 full-text articles for eligibility, excluded a further 21, and thus, included 79 articles in this review (Fig. 1). We recorded all data extraction results using Excel.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search strategy and the studies included and excluded at various steps

We extracted all data concerning cancer type, study size, methodology, and main findings with p-values from the articles. We included study population in the extraction of IL-17F polymorphism studies.

Results

Protein and mRNA expression of IL-17F in various cancers

We present the studies on IL-17F mRNA and protein expression levels in Table 1 based on cancer type listed alphabetically. Below, we describe the results in the order of the most studied cancers of each category.

Table 1.

Interleukin-17F expression in cancer

| Cancer | Sample and cancer type | Target | Method | Patients + control | Main findings | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | Surgical resection | Protein | IHC | 80 (bladder cancer) + 23 (cystitis) + 6 (hyperplastic bladder polyps) | IL-17F was overexpressed in the bladder cancer group (p < 0.01) | Liu et al. 2016 [11] |

| Breast | Blood | Protein | Multiplex | 150 + 60 | Soluble levels of IL-17F were similar between breast cancer patients and healthy control (data not shown) | Avalos-Navarro et al. 2019 [12] |

| Surgical specimens | Protein | IHC | 180 | IL-17F was not associated with pCR rate but tumors with IL17F infiltrates were significantly smaller than those without them (P = 0.041). | Oda et al. 2012 [13] | |

| Colorectal | Cultured rectal cancer biopsy | Protein | Multiplex ELISA | 12 (rectal cancer) + 8 (normal) | IL-17A/F was secreted at significantly higher levels from the rectal cancer secretome than the normal rectal secretome (p = 0.003). | Heeran et al. 2020 [14] |

| CRC, surgical resection | Protein, mRNA | RT-qPCR, WB, IHC | 67 | IL-17F was overexpressed in CRC tumor tissues compared with paired non-tumor mucosa at both mRNA and protein levels. Overexpression of IL-17F was associated with worse RFS (p = 0.03) and OS (p < 0.05) | Chen et al., 2019 [15] | |

| CRC, endoscopic biopsy | Protein | IHC | 29 (CRC) + 17 (UC) + 7 (CHP) | Positive IL-17F was significantly higher in UC and polyp samples compared with CRC (p = 0.00001 and p = 0.0007) | Liu et al. 2018 [16] | |

| CRC, serum | Protein | Multiplex | 122 | No association between IL-17F and OS/PFS | Lereclus et al. 2017 [17] | |

| CC, surgical resection, serum | Protein | Bio-Plex | 33 | Elevated levels of IL-17F were associated with advanced disease. Stage IV showed elevated systemic levels of IL-17F compared to stages I-III (p all< 0.05). | Sharp et al. 2017 [18] | |

| CRC, serum | Protein | ELISA | 109 + 52 | No IL-17F was detected in patients’ sera and only one healthy individual had IL-17F in his serum. | Nemati et al. 2015 [19] | |

| CRC, cultured surgical resection | Protein | IHC/IF | 10 + 10 | IL-17F was decreased in CRC compared to healthy control | Al-Samadi et al. 2015 | |

| CC, surgical resection | Protein + mRNA | IHC, WB, RT-qPCR | 40 | Lower levels of IL-17F mRNA were found in cancer tissue compared to normal mucosa (p < 0.05) | Tong et al. 2012 [20] | |

| Oral | Oral and/or oropharyngeal cancer, saliva | protein | ELISA | 71 | The higher salivary concentrations of IL-17F was significantly associated with disease advancement. | Zielińska et al. 2020 |

| OTSCC, surgical resection | Protein | IHC/IF | 83 | Extracellular IL-17F at the tumor invasion front was associated with better disease-specific survival in patients with all-stages and early-stages of oral tongue SCC. (p = 0.001) | Almahmoudi et al. 2019 [21] | |

| OSCC, blood | Protein | ELISA | 58 + 52 | IL-17F was decreased in OSCC patient samples compared to healthy control (p < 0.05). | Xiaonan et al. 2019 [22] | |

| OSCC, serum | Protein | ELISA | 85 (OSCC) + 15 (leukoplakia) + 28 (healthy) | IL-17F was decreased in OSCC patient samples compared to healthy controls (p < 0.05). Patients with smoking habit had higher IL-17F. | Ding et al. 2015 [23] | |

| Leukemia | CLL, blood | Protein | FCM | 21 + 9 | No significant association between TH17F cells and CLL | Sherry et al. 2015 [24] |

| B-CLL, serum and cell lysates | Protein | WB, ELISA | 23 + 13 | IL-17F is less expressed in PMNs and B-lymphocytes of patients compared to cells of healthy subjects. IL-17F was significantly increased in serum of stage IV disease patients compared with healthy subjects and stage 0/I and III patients. | Garley et al., 2014 [25] | |

| Liver | HCC, blood | Protein | Bio-Plex | 87 + 87 | IL-17F levels not associated with HCC | Shen et al. 2018 [26] |

| HCV-HCC, surgical resection | mRNA | qRT-PCR | 40 (cancerous + adjacent non-cancerous tissues) | IL-17F positive frequency was higher in cancerous tissue than in non-cancerous tissue | Wu et al. 2017 [27] | |

| Lung | surgical resection | Protein | IHC | 55 + 12 | Expression of IL-17F was positively associated with tumor differentiation and negatively associated with lymph node metastasis and TNM staging (p all< 0.05) | Li et al. 2019 [28] |

| NSCLC, surgical resection | Protein | IHC | 29 (squamous cell carcinoma) + 30 (adenocarcinoma) + 10 (healthy control) | IL-17F immunoreactivity was increased in both SCC and ADC tissue compared with healthy control (p < 0.05). IL-17F immunoreactivity was expressed principally in macrophages, but also epithelial cells and some malignant cells. | Huang et al., 2018 [29] | |

| NSCLC, serum | Protein | Multiplex | 50 + 14 | IL-17F was decreased in squamous cell carcinoma stage M1 compared to M0 (P < 0.05) and in stages IIIB-IV compared to stages I-IIIa (p < 0.01) | Yang et al. 2015 [30] | |

| Lymphoma | BIA-ALCL, surgical resection | Protein | IHC | 4 (BIA-ALCL) + 4 (healthy) + 10 (LP) + 6 (pcALCL) | IL-17F expression was weaker in BIA-ALCL tumor cells | Kadin et al. 2016 [31] |

| AIDS-NHL, serum | Protein + mRNA | multiplex immunoassay | 176 (AIDS-NHL) + 176 (HIV+) | No significant association between IL-17F expression and AIDS-NHL | Vendrame et al. 2014 [32] | |

| CTCL, skin biopsy | mRNA | PCR | 60 | IL-17F was expressed more in progressive CTCL compared to non-progressive disease (p < 0.05) | Willerslev-Olsen et al. 2014 [33] | |

| CTCL, surgical resection | mRNA | PCR | 60 | IL-17F+ patients had a significantly increased risk of disease progression (odds ratio = 2.75; p = 0.025) compared with IL-17F- patients | Krejsgaard et al. 2013 [34] | |

| CTCL, surgical resection | mRNA | RT-qPCR | 21 (CTCL) + 5 (psoriasis) + 6 (normal) | IL17F mRNA levels were not significantly elevated in lesional skin of CTCL | Miyagaki et al. 2011 [35] | |

| CTCL, surgical resection | mRNA | RT-PCR | 62 | IL-17F genes were expressed in poor prognosis clusters, and seemed to strongly correlate with an advanced and/or progressive disease | Litvinov et al. 2010 [36] | |

| Ovarian | surgical resection | Protein | FCM | 24 (cystadenocarcinoma) + 25 (cystadenoma) + 11 (serous borderline tumors) + 20 (control) | Number of IL-17F-positive TH17 cells is not increased or decreased in ovarian cancer | Winkler et al. 2017 [37] |

| ascites | Protein | Cytokine profiling kit | 266 | No association between IL-17F and OS | Chen et al. 2015 [38] | |

| Pancreas | serum | Protein | Luminex | 78 (pancreatic adenocarcinoma) + 41 (control) + 40 (chronic pancreatitis) + 20 (recurrent acute pancreatitis) | IL-17F was decreased in pancreatic adenocarcinoma when compared with chronic pancreatitis (p = 0.023) | Park et al. 2020 [39] |

| Prostate | surgical resection | Protein | IHC | 116 (prostate cancer) + 10 (BPH) | A significant higher IL-17F expression was found in the prostate cancer group in comparison to the BPH group (p < 0.05). | Janiczek et al. 2020 [40] |

| surgical resection | Protein | IHC | 29 (prostate adenocarcinoma) + 47 (BPH) + 6 (control) | IL-17F was elevated in BPH (p = 0.014) and prostate adenocarcinoma (p = 0.026) compared to healthy controls. | Liu et al. 2015 [41] | |

| Skin | Skin BCC, serum | Protein | ELISA | 81 + 53 | IL-17F levels not associated with cancer risk | Mohammadipour et al. 2019 [42] |

Abbreviations: AIDS-NHL = HIV-infection associated non-hodgkin lymphoma, ADC = adenocarcinoma B-CLL = B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, BCC = basal cell carcinoma, BIA-ACLC = breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma, BPH = bening prostatic hyperplasia, CC = colon cancer, CHP = colorectal hyperplastic polyps, CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CRC = colorectal cancer, CTCL = cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, FCM = flow cytometry, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV-HCC = hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma IF = immunofluorescence, IHC = immunohistochemistry, LP = lymphomatoid papulosis, NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer, OS = overall survival, OSCC = oral squamous cell carcinoma, OTSCC = oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma, pcALCL = primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, pCR = pathological complete response, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PFS = progression-free survival, PMNs = polymorphonuclear cells, RFS = relapse-free survival, RT-PCR = real-time or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, RT-qPCR = quantitative real-time or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, SCC = squamous cell carcinoma, UC = ulcerative colitis, WB = western blotting

IL-17F expression is linked to colorectal cancer

The expression of IL-17F has been investigated most in colorectal cancer (CRC) [14–20, 43]. IL-17F expression in CRC tissue samples was studied in 4 articles [15, 16, 20, 43]. In three articles, IL-17F expression in tumour sections was decreased [16, 20, 43]. Al-Samadi et al. [43] showed by immunohistochemistry that IL-17F level was decreased in CRC compared with healthy controls, and similarly, Liu et al. [16] found less IL-17F in CRC than in ulcerative colitis or polyp samples. In addition, IL-17F mRNA expression was reduced in colon cancer according to Tong et al. [20]. However, Chen et al. [15] reported recently that IL-17F was overexpressed in tumour mucosa compared with paired non-tumour mucosa.

Serum levels of IL-17F in CRC patients were studied in 3 articles [17–19]. In one publication, elevated serum, together with conditioned media from cultured surgical resection, levels of IL-17F were associated with advanced colon cancers [18], whereas no association between serum levels and overall survival or progression-free survival among CRC patients was detected in another publication [17], and in a third publication, no detectable IL-17F levels in CRC patients’ serum were found [19].

Heeran et al. [14] showed that IL-17A/F secretion from the cultured rectal cancer biopsy was significantly higher than the normal rectal tissue, however the study did not report the level of IL-17F alone.

IL-17F has mainly a protective role in oral squamous cell carcinoma, but not in skin basal cell carcinoma

Four articles investigated the expression of IL-17F in oral cancers [22, 23, 44, 45]. Three articles reported a protective role of IL-17F in oral cancer while the fourth one suggested a protumorgenic effect for IL-17F. Extracellular IL-17F at the tumour invasion front was associated with better disease-specific survival among oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma (OTSCC) patients [44]. In two studies, serum-derived IL-17F was decreased in OSCC patients compared with healthy controls [22, 23]. On the other hand, the concentration of IL-17F in the saliva of oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients was significantly associated with disease progression [45]. To conclude, IL-17F protein in tissue and serum, but not in saliva, seems to possess an antitumorigenic role in oral cancers. By contrast, in skin basal cell carcinoma, serum levels of IL-17F were not associated with cancer risk [42].

Variation in IL-17F expression in lymphomas and leukemia

In six articles, the expression of IL-17F in lymphomas was evaluated [31–36]. Kadin et al. [31] found that IL-17F expression was weaker in breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) cells than in benign capsular infiltrates. In three articles, tumoral IL-17F mRNA expression was linked to progressive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) [33, 34, 36], which indicates a protumorigenic role of IL-17F in CTCL. However, Miyagaki et al. [35] did not find elevated levels of IL-17F mRNA in CTCL, and no association between IL-17F serum level and risk for HIV-associated Non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma was detected by Vendrame et al. [32].

Two studies addressed the role of IL-17F in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) [24, 25]. The first publication showed an increase in serum IL-17F in stage IV B-CLL patients compared with healthy controls and stage 0/I and III patients [25]. The same study found a lower IL-17F expression in PMNs and B-lymphocytes of patients compared to cells of healthy subjects [25]. The second study reported no significant association between TH17F+ cells and CLL [24].

No consensus on IL-17F levels in lung cancer

Regarding lung malignancies, we found three studies in which IL-17F was measured [28–30]. Huang et al. [29] documented that IL-17F immunoreactivity was increased in both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma tissues compared with healthy controls. In contrast, according to Li et al. [28], IL-17F was positively associated with tumour differentiation and negatively with lymph node metastasis and TNM staging. Similarly, Yang et al. [30] found that IL-17F, in the patients’ serum, was decreased in more progressive disease.

Amount of IL-17F varies in breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers

Two studies have analysed IL-17F protein amount in breast cancer patients [12, 13]. Oda et al. [13] noted that IL-17F+ tumour infiltrate T-cells were associated with smaller tumour size. Avalos-Navarro et al. [12] did not find an association between serum IL-17F expression and breast cancer. In ovarian cancer, levels of IL-17F+ Th17-cells were similar between cancer and control groups [37], and IL-17F in the ascites fluid was not associated with patients’ overall survival [38]. As for prostate cancer, two studies reported that IL-17F was overexpressed in prostate cancer samples relative to healthy controls [41] or benign prostatic hyperplasia [40].

Expression of IL-17F in liver, pancreatic, and bladder cancers varies

In liver cancer, one study reported no association between IL-17F protein levels and hepatocellular carcinoma [26], whereas another one suggested that IL-17F mRNA was more often present in cancerous than in adjacent non-cancerous tissue of hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma [27]. IL-17F was decreased in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma compared with chronic pancreatitis patients [39]. In bladder cancer, IL-17F was overexpressed in the cancer group compared with the cystitis and hyperplastic bladder polyp groups [11].

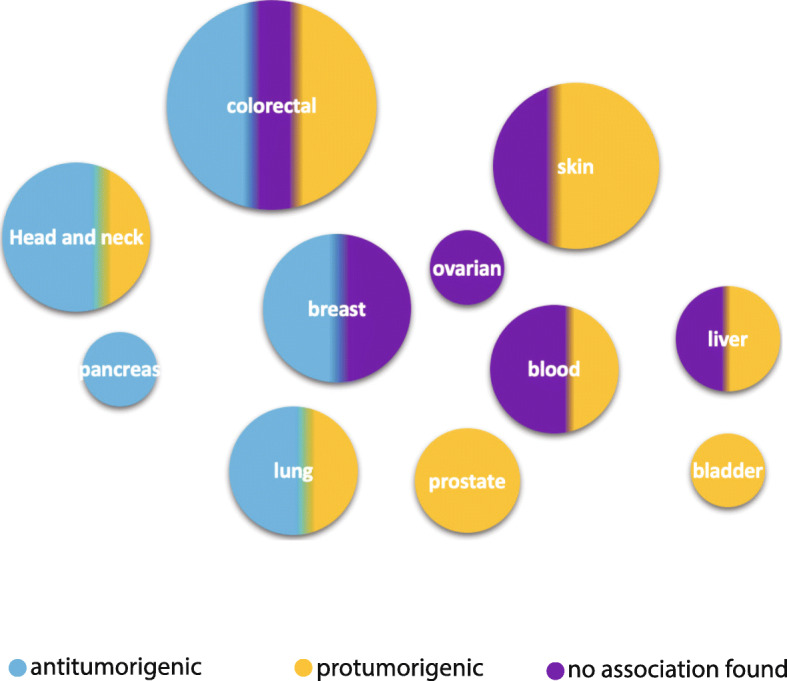

To summarize, IL-17F expression (protein and mRNA) levels in tumour and serum samples seem to depend on cancer type (Fig. 2), and more studies are needed prior to concluding its predictive value in any of the malignancies.

Fig. 2.

Interleukin-17F expression and its role in tumorigenesis. The size of dots represents the number of studies included in this review and the colour represents the possible role of IL-17F expression in tumorigenesis

IL-17F SNPs

Eight IL-17F SNPs (rs763780, rs9382084, rs12203582, rs1266828, rs2397084, rs7771511, rs641701, and rs9463772) were studied in terms of their association with 13 types of cancer in 38 studies [17, 19, 42, 46–76]. Findings are collected in Tables 2 and 3. In six cancers – breast, cervical, laryngeal, liver, skin, and pancreatic cancer – no significant association was found with the IL-17F SNPs [42, 46–49, 52, 70, 71]. In six cancers – acute myeloid leukemia, bladder, colorectal, gastric, lung, and oral cancer – the results were inconsistent [17, 19, 50, 51, 53–69, 72–75, 77, 78]. One study reported significant association between rs763780 IL-17F SNP and high risk of developing follicular lymphoma [76].

Table 2.

Summary of the studies concerning the role of IL-17F polymorphisms in cancer

| SNP | Cancer type | Total studies No. | No association No. | Association No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs763780 | Bladder | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Blood (AML) | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Breast | 2 | 2 | – | |

| Cervix | 3 | 3 | – | |

| Colorectal | 7 | 4 | 3 | |

| Gastric | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| Oral | 2 | 2 | – | |

| Larynx | 1 | 1 | – | |

| Liver (HBV-HCC) | 1 | 1 | – | |

| Lung | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lymphoma | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Pancreas | 1 | 1 | ||

| Skin (BCC) | 1 | 1 | – | |

| rs9382084 | Breast | 1 | 1 | – |

| Cervix | 1 | 1 | – | |

| Gastric | 1 | – | 1 | |

| rs12203582 | Breast | 1 | 1 | – |

| Gastric | 1 | 1 | – | |

| Lung | 1 | – | 1 | |

| rs1266828 | Breast | 1 | 1 | – |

| Cervix | 1 | 1 | – | |

| Lung | 1 | 1 | – | |

| rs2397084 | Oral | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Lung | 1 | 1 | – | |

| rs7771511 | Breast | 1 | 1 | – |

| rs641701, | Colorectal | 1 | – | 1 |

| rs9463772 | Colorectal | 1 | – | 1 |

Abbrevations: AML = acute myeloid leukemia, BCC = basal cell carcinoma, HBV-HCC = hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma

Table 3.

IL-17F polymorphisms in cancer

| Cancer | SNPs | Population (country) | Study size (patients + healthy control) | Effect on patient (p-value) | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | rs763780 | Iran | 180 + 180 | The rs763780 polymorphism was not associated with bladder cancer susceptibility in the Iranian population. | Aslani et al., 2020 [72] |

| rs763780 | Poland | 175 + 207 | rs763780 polymorphism was not associated with bladder cancer susceptibility | Krajewski et al. 2020 [73] | |

| rs763780 | China (Han) | 301 + 446 | TT genotype and T allele of rs763780 were more common among patients than controls. Rs763780 SNP was associated with bladder cancer development and tumor stage, as well as gender and smoking status of patient. | Zhou et al. 2013 [67] | |

| Blood | rs763780 | Egypt | 100 + 100 | IL-17F mutation showed neither correlation with AML susceptibility nor with therapy outcome. | Zayed et al. 2020 [74] |

| rs763780 | Egypt | 100 + 100 | IL-17F gene polymorphisms was not associated with AML risk | Elsissy et al. 2019 [50] | |

| rs763780 | Poland | 62 + 125 | The rs763780 IL-17F polymorphism was found to be associated with predisposition to AML | Wróbel et al. 2014 [51] | |

| Breast | rs763780 | Southern Iran | 192 + 215 | No association between IL-17F polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility | Naeimi et al. 2014 [46] |

| rs7771511, rs9382084, rs12203582, rs1266828, rs763780 | China (Han) | 491 + 502 | No association between IL-17F polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility | Wang et al. 2012 [47] | |

| Cervix | rs763780 | China | 352 + 352 | No association between IL-17F polymorphisms and cervical cancer | Cong et al. 2015 [48] |

| rs763780, rs9382084, rs1266828 | China | 264 + 264 | No significant association between IL-17F polymorphisms and cancer risk | Lv et al. 2015 [49] | |

| rs763780 | China | 311 + 463 | No association between IL-17F polymorphisms and cancer risk or patient clinical characteristics | Quan et al., 2012 [52] | |

| Colorectal | rs641701, rs9463772 | Italy | 370 (test set n = 233, validation set n = 137) | rs641701 and rs9463772 were found to be a prognostic markers related to a high risk of LARC disease recurrence, metastasis, and death | Cecchin et al. 2020 [75] |

| rs763780 | China | 352 + 433 | IL-17F rs763780 polymorphism was not associated with the risk of CRC | Feng et al. 2019 [53] | |

| rs763780 | Korea | 695 + 1846 | Dietary pattern reflecting inflammation was significantly associated with CRC risk. Moreover, this association could be modified according to the IL-17F rs763780 genotype and anatomic site. | Cho et al. 2018 [54] | |

| rs763780 | Saudi Arabia | 117 + 100 | No association between IL-17F polymorphisms and CRC risk | Al Obeed et al. 2018 [55] | |

| rs763780 | Malaysia | 70 + 80 | No association between IL-17F polymorphisms and CRC risk | Samiei et al. 2018 [56] | |

| rs763780 | France | 122 | IL-17F polymorphisms was not associated with OS/PFS | Lereclus et al. 2017 [17] | |

| rs763780 | Southern Iran | 202 + 203 | T allele of IL-17F T7488C may be involved in reduced risk of CRC | Nemati et al. 2015 [19] | |

| rs763780 | Tunisia | 102 | IL-17F AG + GG genotypes were more frequent in controls than in patients with colon cancer, and IL-17F wild type genotype AA had an impact on OS. | Omrane et al. 2015 [57] | |

| Gastric | rs763780 | Korea | 300 + 247 | T allele frequency of IL-17F rs763780 was found to be statistically higher in patients with gastric cancer, compared with healthy controls | Choi et al. 2016 [58] |

| rs763780 | China | 153 + 207 | No association was found between IL-17F rs763780 T > C genotype and risk of gastric cancer | Zhao et al. 2016 [59] | |

| rs763780 | China | 326 + 326 | No significant positive association was observed with the risk of gastric cancer and IL-17F polymorphisms | Hou et al. 2015 [60] | |

| rs763780 | China | 462 + 462 | No significant differences between rs763780 genotypes and gastric cancer risk | Wang et al. 2014 [61] | |

| rs763780 | Chile | 147 + 172 | IL-17F polymorphisms was not associated with risk of gastric cancer | Gonzalez-Hormazabali et al. 2014 [63] | |

| rs763780 | China | 572 + 572 | rs763780 polymorphism may be associated with risk of developing gastric cancer, particularly among alcohol drinkers. | Gao et al. 2014 | |

| rs763780, rs9382084, rs12203582 | China | 293 + 550 | The rs9382084 TT genotype was significantly associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer and has interaction with tobacco smoking on gastric cancer risk. Rs9382084 genetic variants greatly increase risk of non-cardia gastric cancer. No association was found between variants of rs763780 and rs12203582 and gastric cancer risk | Qinghai et al. 2013 [64] | |

| rs763780 | China (Han) | 962 + 787 | IL-17F polymorphisms associated with susceptibility to gastric cancer and clinopathological features of it | Wu et al. 2010 [65] | |

| rs763780 | Japan | 102 | No significant association between CIHM status and IL-17F (7488 T > C) | Tahara et al. 2010 [66] | |

| rs763780 | Japan | 287 + 524 | No significant difference between IL-17F genotypes and risk of gastric cancer | Shibata et al. 2009 [68] | |

| Head and neck | rs763780, rs2397084 | China | 182 + 364 | No association between rs763780 and rs2397084 polymorphisms and risk of oral cancer | Hu et al. 2017 |

| rs763780, rs2397084 | China | 121 + 103 | Rs2397084, but not rs763780, was associated with OSCC risk, and this was related to tumor stage and differentiation. IL-17F polymorphisms together with smoking and drinking can enhance the risk of OSCC development | Li et al. 2015 [78] | |

| Larynx | rs763780 | China | 325 + 325 | IL-17F genotypes and alleles was not associated with risk of laryngeal cancer | Si et al. 2017 [70] |

| Liver | rs763780 | China | 155 + 171 | IL-17F rs763780 polymorphisms do not contribute to HBV-related HCC susceptibility independently | Xi et al. 2015 [72] |

| Lung | rs763780, rs1266828, rs12203582 | China | 320 + 358 | rs763780 and rs1266828 were not associated with lung cancer risk. Rs12203582 associated with risk of lung cancer, also among smokers. | He et al. 2017 [69] |

| rs763780, rs2397084 | Tunisia | 239 + 258 | IL-17F 7488G allele was associated with increased lung cancer risk. IL-17F7383 A/G polymorphism was not associated with lung cancer risk | Kaabachi et al. 2014 [62] | |

| Lymphoma | rs763780 | Brazil | 152 + 212 | rs763780 polymorphism increased risks of developing follicular lymphoma. | Assis-Mendonça et al., 2020 [76] |

| Pancreas | rs763780 | European and African | 351 (European ancestry n = 294, African ancestry n = 26) | OS was significantly shorter for the rs763780 heterozygotes compared with controls, but this did not hold in the multivariate analysis. | Innocenti et al. 2012 [71] |

| Skin | rs763780 | Iran | 200 + 200 | No association of rs763780 gene polymorphisms and risk of BCC | Mohammadipour et al. 2019 [42] |

Abbrevations: AML = acute myeloid leukemia, BCC = basal cell carcinoma, CIHM = CpG island hypermethylation, CRC = colorectal cancer, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, LARC = locally Advanced Rectal Cancer, OS = overall survival, OSCC = oral squamous cell carcinoma, PFS = progression-free survival

Proposed function of IL-17F based on in vivo and in vitro studies

We analysed the mechanisms by which IL-17F affects cancer development and progression based on in vitro and in vivo animal studies and collected the findings in Table 4.

Table 4.

Interleukin-17F functional studies

| Cancer | Study type | Cell lines/animal type | Main results | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | in vitro | PBMCs and CD4+ T cells | IL-17F triggers NFkB phosphorylation in T and B cells from patients with CLL, but not age-matched healthy controls. | Sherry et al. 2015 [24] |

| Breast | in vitro | MCF-7 cells | IL-17F enhances MCF-7 cell proliferation, migration and invasion via activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. | Chen et al. 2020 [81] |

| Colorectal | in vitro | HCT116 cells | IL-17F promotes cancer cell migration and invasion by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition | Chen et al., 2019 [15] |

| in vitro | HCT116 wild-type and IL-17F overexpressing cell clones | IL-17F plays an important role in colon cancer development through regulation of cell cycle. This could partially happen through IL-17F effects on p27 and p38. | Tong et al. 2014 [82] | |

| in vitro, in vivo | ApcMin/+ mice, CRC cell lines (DLD-1 and HT-29) | Tumor-infiltrating leukocytes produce large amounts of T helper type IL17-related cytokines, including IL-17F. Individual neutralization of IL-17F does not change the TIL-derived proproliferative effect in CRC cells. | De Simone et al., 2014 | |

| in vitro, in vivo | Cell lines (HCT116, HUVEC), BALB/c nude mice and C57BL/6 mice | IL-17F has protective role in colon cancer, possibly by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis. | Tong et al. 2012 [20] | |

| Gastric | in vitro | Gastric cancer cell line (AGS) | IL-17F, may contribute to amplification and persistence of inflammatory processes implicated in inflammation-associated cancer through activation of p65 NFkB. | Zhou et al. 2007 [83] |

| Oral | in vitro | Cell lines (HSC-3, SCC-25, SAS) | IL-17F has an antitumorigenic effect through inhibition of the vasculogenic mimicry | Almahmoudi et al. 2021 [84] |

| in vitro | Cell lines (HSC-3, SCC-25, HOKs, HUVEC, CAF) | IL-17F inhibited cell proliferation and random migration of oral cancer cells and inhibited the endothelial cell tube formation. | Almahmoudi et al. 2019 [21] | |

| Liver | in vitro, in vivo | Cell lines (293 T, SMMC-7721, ECV304), athymic nude mice | IL-17F suppresses cancer cell growth via inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. | Xie et al. 2010 [85] |

| Lung | in vitro, in vivo | Human A549 and murine LL/2 (LLC1) lung cancer cell lines, bone marrow-derived macrophages from C57BL/6 mice. Chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) | IL-17A/F does not affect cancer cell viability or glycolytic metabolism in vitro. Conditioned media from IL-17A/F-stimulated macrophages promoted lung cancer cell progression through an increased migration capacity in vitro and enhanced in vivo tumor growth, proliferation and angiogenesis. | Ferreira et al. 2020 [86] |

| in vivo | CCSPcre/K-rasG12D mice | IL-17F has no effect on lung cancer development in K-ras mutated mouse model. | Chang et al. 2014 [87] | |

| Small intestine | in vivo | ApcMin/+ mice | Ablation of IL-17F significantly inhibits spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis in the small intestine of ApcMin/+ mice. This was associated with decreased IL-1b and Cox-2 expression as well as IL-17 receptor C (IL-17RC) expression | Chae et al., 2011 [88] |

Abbrevations: CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CAF = cancer-associated fibroblasts, HOKs = human oral keratinocytes, HUVEC = human umbilical vein endothelial cells, NFkB = Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cell, TIL = tumor-infiltrating leukocyte

Mechanisms for antitumour effects of IL-17F

Several mechanisms have been suggested through which IL-17F exert its antitumorigenic effects, including inhibition of tumour angiogenesis, cell cycle regulation, cancer cell proliferation and migration, and cancer vasculogenic mimicry. IL-17F inhibited tumour angiogenesis in three cancer types: liver [85], colon [20], and oral [21, 84]. IL-17F inhibited oral carcinoma cell proliferation, random cell migration and vasculogenic mimicry [21, 84], controlled the cell cycle through p27 and p38, and diminished oxidative stress-causing G2/M phase arrest in colon carcinoma cells [82].

Mechanisms for protumorigenic effects of IL-17F

In addition to the possible macrophage-mediated, pro-angiogenic role of IL-17F presented by Ferreira et al. [86], IL-17F was found to contain also other protumorigenic properties, through inflammation [83], epithelial-mesenchymal transition [15] NFkB regulation [24] and MAPK/ERK activation [81]. Zhou et al. [83] showed that IL-17F might enhance inflammatory processes in inflammation-associated cancer through activation of p65 NFkB. Similarly, Sherry et al. [24] reported that IL-17F causes NFkB phosphorylation in T- and B-cells of CLC patients.

Conditioned media from IL-17F-stimulated macrophages promoted lung cancer progression by enhancing cancer cell migration in vitro and tumour growth in vivo [86], but no connection existed between IL-17F and lung tumour number in a mouse model [87], nor was there any connection between lung cancer cell viability and glycolytic metabolism in vitro [86].

The CRC cell migration and invasion promoting role of IL-17F was caused by induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HCT-116 cells [15]. Similarly, Chen et al. [81] found that IL-17F enhances MCF-7, a breast cancer cell line, cell proliferation, migration and invasion via activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. In ApcMin/+ mice, knockout of IL-17F inhibited small intestine tumorigenesis, and this was associated with decreased IL-1b, Cox-2, and IL-17RC expression [88]. In addition, IL-17F was not associated with a TIL-derived proliferative effect in CRC [89].

Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to clarify the role of IL-17F, protein and mRNA expression and polymorphisms, in cancer and the mechanisms through which IL-17F affects cancer development and progression. We collected publications from four databases (Ovid Medline, PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane Library). Based on the collected data, IL-17F seems to play a role in cancer development and progression. However, this role was shown to be either pro- or antitumorigenic depending on the cancer type, the source (tissue or fluid) from which it was measured, and the form (protein or mRNA) in which it was analyzed. The correlation between IL-17F polymorphism and cancer incidence or patients’ prognosis seemed to be weak in every cancer analyzed. Effects of IL-17F on cancer progression were shown to be through several different mechanisms.

The correlation between IL-17F expression and cancer has been studied in 13 different cancers in 34 publications. The results have varied in different cancers and depending on the expression (protein or mRNA) and location (tumour tissue or soluble) of IL-17F. The main findings concerning IL-17F protein expression were in OSCC, which showed that IL-17F expression in tumor tissue and patient serum, but not in saliva, was associated with better prognosis [22, 23, 44, 45]. The opposite effect was noticed in prostate cancer [40, 41]. In the case of colorectal cancer and lymphomas, which were studied quite extensively, the results were inconclusive [15–20, 31–36, 43]. In other cancers, there were only a few studies or the results varied too much to draw a clear conclusion. This variation in the role of IL-17F in different cancers is common also in other proteins such as MMP-8 [90]. Despite IL-17A and IL-17F binding to the same receptors, namely IL-17RA and IL-17RC, and sharing high homology, IL-17A has a clearer protumorigenic effect [9], while the role of IL-17F is variable. One clear example of the variation between the two cytokines is their role in oral cancer. As mentioned earlier, IL-17F was shown to be an antitumour cytokine in most of the analysed articles in this review, while IL-17A was reported more than once to be a protumour cytokine [91, 92].

The association between IL-17F polymorphisms and cancer was another important aspect in this review, but again the results were variable. Rs763780 polymorphisms have been broadly studied in CRC and gastric cancers [17, 19, 53–61, 63–66, 68, 75], but the findings have been diverse. Other IL-17F SNPs has been less extensively analyzed, and more studies are needed to confirm the relevance of IL-17F polymorphisms in various cancers. As with the expression results, the data for IL-17A polymorphisms are more solid than for IL-17F. The results of a meta-analysis covering 10 case-control studies, involving 4516 cases and 5645 controls, showed a significant association between IL-17A polymorphisms and the risk of developing cancer, particularly gastric cancer, in the Asian (and Chinese) population [93].

There were only a few functional studies of IL-17F, suggesting both an anti- and protumorigenic roles. One of the main mechanisms by which IL-17F exerts its antitumorigenic effect is the inhibition of angiogenesis and vasculogenic mimicry, which was reported in four studies [20, 21, 84, 85]. Inhibition of tumour angiogenesis and vasculogenic mimicry could thus be a potential therapeutic target in cancer treatment [94]. Other antitumorigenic mechanisms of IL-17F included the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and migration [21] and cell cycle regulation [82]. A protumorigenic role of IL-17F could be caused by regulation of inflammatory responses [83], epithelial-mesenchymal transition [15], IL-1b, Cox-2, and IL-17CR expression [88] and MAPK/ERK activation [81]. Since Ferreira et al. [86] assessed the effects of IL-17A and IL-17F simultaneously, their findings cannot be extrapolated to IL-17F alone. In our search for the functional studies of IL-17F in cancer, we detected two interesting articles reporting opposite results about the role of IL-17F in colon cancer. Tong and his colleagues claimed an anti-tumorigenic role for IL-17F by showing a significant decrease in the tumor growth when IL-17F over expressed HCT116 cells transplanted subcutaneously in nude mice comparing with the mock transfectants [20]. They also used AOM-DSS induced inflammation-associated colon cancer IL-17F−/− mice model to show that these mice had higher colonic tumor numbers and tumor areas compared with the wild-type controls. After further analysis, they found that this anti-tumorgenic role in both models was possibly a result of inhibition of tumor angiogenesis through decreasing VEGF levels and CD31+ cells. On the other hand, Chae and Bothwell used ApcMin/+ mice model highly susceptible to develop spontaneous intestinal adenoma to study the effect of IL-17F on intestinal cancer [88]. Opposite to the Tong et al., IL-17F knockout ApcMin/+ mice inhibited the spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis compared with the ApcMin/+ mice. This was also associated with reducing IL-1β, Cox-2, and IL-17RC expression suggesting proinflammatory and protumorgenic roles of IL-17F in intestinal cancer [88]. These contrary results are confusing, however they could be due to the different mice models used in the two studies.

In contrast to IL-17A, which has already been studied intensively, IL-17F has thus far received much less attention in the cancer research field. Based on our criteria, only 79 articles were included in this review, which is a low number considering that we included all types of cancer. Weaknesses of this review comprise its broad scope and the large number of different types of studies, making it impossible to provide an in-depth analysis of them. Additionally, studies included in this article examined a variety of different designs, study populations and primary/secondary outcomes, which unfortunately reduce the value of direct interstudy comparisons and therefore these comparisons should be taken with caution. Nevertheless, this review gives an overall picture of the variable IL-17F roles in different cancers.

In conclusion, more well-designed studies of IL-17F are needed to elucidate its molecular mechanisms in different types of cancer. These studies are important to address several aspects such as the difference in the function between tissue or soluble IL-17F, the affected pathways through which IL-17F exert its effect, the effect of IL-17F on the tumor stroma cells, especially inflammatory cells, and if targeting IL-17F could provide a therapeutic benefits for cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BIA-ALCL

breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CTCL

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- IL

interleukin

- MAPK/ERK

mitogen-activated protein kinase/ extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- OTSCC

oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- PMNs

polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- PRISMA

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Authors’ contributions

AA and TS: conceptualization; TM and RA: data curation; TM and RA: formal analysis; TS: funding acquisition; AA, TM, RA: investigation; AA, TM, RA: methodology; AA and TS: project administration; TS: resources; AA and TS: supervision; TM: writing - original draft; AA, TS, RA: writing - review & editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the funders of this study: the Doctoral Programme in Clinical Research, University of Helsinki; the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation; the Cancer Society of Finland; the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation; the Oulu University Hospital MRC grant; the Helsinki University Central Hospital research funds; and the Doctoral Programme of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki. The funders took no part in the design or performance of the study. Funding consists of academic grants without any engagements considering the research project.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu S, Zhu W, Thompson P, Hannun YA. Evaluating intrinsic and non-intrinsic cancer risk factors. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):3490–018-05467-z. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawyers CL. The cancer biomarker problem. Nature. 2008;452(7187):548–552. doi: 10.1038/nature06913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silk AW, Margolin K. Cytokine therapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(2):261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SH, Dong C. IL-17F: regulation, signaling and function in inflammation. Cytokine. 2009;46(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majumder S, McGeachy MJ. IL-17 in the pathogenesis of disease: good intentions gone awry. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39(1):537–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-092536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Qian T, Zhang D, Yan H, Hao F. Clinical efficacy and safety of anti-IL-17 agents for the treatment of patients with psoriasis. Immunotherapy. 2015;7(9):1023–1037. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z, Li J, Jiang K. Relationship between Th17 cells and allograft rejection. Front Med. 2009;3(4):491–494. doi: 10.1007/s11684-009-0066-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang B, Kang H, Fung A, Zhao H, Wang T, Ma D. The role of interleukin 17 in tumour proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis; 25110397. Mediat Inflamm. 2014;2014:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2014/623759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ, Gaffen SL. The IL-17 family of cytokines in health and disease. Immunity. 2019;50(4):892–906. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Yang W, Zhao L, Liang Z, Shen W, Hou Q, et al. Immune analysis of expression of IL-17 relative ligands and their receptors in bladder cancer: Comparison with polyp and cystitis; 27716046. BMC Immunol. 2016;17:–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Avalos-Navarro G, Muñoz-Valle JF, Daneri-Navarro A, Quintero-Ramos A, Franco-Topete R, Morán-Mendoza AJ, et al. Circulating soluble levels of MIF in women with breast cancer in the molecular subtypes: relationship with Th17 cytokine profile; 31102004. Clin Exp Med. 2019;19(3):385–391. doi: 10.1007/s10238-019-00559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oda N, Shimazu K, Naoi Y, Morimoto K, Shimomura A, Shimoda M, et al. Intratumoral regulatory T cells as an independent predictive factor for pathological complete response to neoadjuvant paclitaxel followed by 5-FU/epirubicin/cyclophosphamide in breast cancer patients; 22986814. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(1):107–16. 10.1007/s10549-012-2245-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Heeran AB, Dunne MR, Morrissey ME, Buckley CE, Clarke N, Cannon A, et al. The protein secretome is altered in rectal cancer tissue compared to normal rectal tissue, and alterations in the secretome induce enhanced innate immune responses 2021;13(3):1–18, DOI: 10.3390/cancers13030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Chen Y, Yang Z, Wu D, Min Z, Quan Y. Upregulation of interleukin-17F in colorectal cancer promotes tumor invasion by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Rep. 2019;42(3):1141–1148. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Sun X, Zhao X, An L, Wang Z, Jiang J, et al. Expression and location of IL-17A, E, F and their receptors in colorectal adenocarcinoma: comparison with benign intestinal disease. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214(4):482–91. 10.1016/j.prp.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lereclus E, Tout M, Girault A, Baroukh N, Caulet M, Borg C, et al. A possible association of baseline serum IL-17A concentrations with progression-free survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with a bevacizumab-based regimen. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):220. 10.1186/s12885-017-3210-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Sharp SP, Avram D, Stain SC, Lee EC. Local and systemic Th17 immune response associated with advanced stage colon cancer. J Surg Res. 2017;208:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nemati K, Golmoghaddam H, Hosseini SV, Ghaderi A, Doroudchi M. Interleukin-17FT7488 allele is associated with a decreased risk of colorectal cancer and tumor progression. Gene. 2015;561(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong Z, Yang XO, Yan H, Liu W, Niu X, Shi Y, et al. A protective role by interleukin-17F in colon tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34959. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Almahmoudi R, Salem A, Murshid S, Dourado MR, Apu EH, Salo T, et al. Interleukin-17F has anti-tumor effects in Oral tongue Cancer. Cancers. 2019;11(5):650. 10.3390/cancers11050650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Xiaonan H. Expression levels of BDNF, VEGF, IL-17 and IL-17F in oral and maxillofacial squamous cell carcinoma and their clinicopathological features. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2019;35(3):1225–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding L, Hu E-L, Xu Y-J, Huang X-F, Zhang D-Y, Li B, et al. Serum IL-17F combined with VEGF as potential diagnostic biomarkers for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2015;36(4):2523–9. 10.1007/s13277-014-2867-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sherry B, Jain P, Chiu PY, Leung L, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, et al. Identification and characterization of distinct IL-17F expression patterns and signaling pathways in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and normal B lymphocytes. Immunol Res. 2015;63(1–3):216–27. 10.1007/s12026-015-8722-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Garley M, Jablonska E, Sawicka-Powierza J, Ratajczak-Wrona W, Kloczko J, Piszcz J. Expression of subtypes of interleukin-17 ligands and receptors in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Lab. 2014;60(10):1677–1683. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2014.131107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen J, Wu H, Peng N, Cai J. An eight cytokine signature identified from peripheral blood serves as a fingerprint for hepatocellular cancer diagnosis; 30602951. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(2):260–266. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu MS, Wang CH, Tseng FC, Yang HJ, Lo YC, Kuo YP, et al. Interleukin-17F expression is elevated in hepatitis C patients with fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Infect. Agents Cancer. 2017;12:42–017–0152-7. doi: 10.1186/s13027-017-0152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Ma X, Tan C, Fang H, Sun Y, Gai X. IL-17F expression correlates with clinicopathologic factors and biological markers in non-small cell lung cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(10):152562. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Q, Ma XC, Yang X, Wang W, Li Y, Lv Z, et al. Expression of IL-17A, E, and F and their receptors in non-small-cell lung cancer; 30334403. J Biol Reg Homeost Agents. 2018;32(5):1105–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang D, Zhou J, Zeng T, Yang Z, Wang X, Hu J, et al. Serum chemokine network correlates with chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer; 25976768. Cancer Lett. 2015;365(1):57–67. 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kadin ME, Deva A, Xu H, Morgan J, Khare P, MacLeod RAF, et al. Biomarkers provide clues to early events in the pathogenesis of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma; 26979456. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(7):773–781. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vendrame E, Hussain SK, Breen EC, Magpantay LI, Widney DP, Jacobson LP, et al. Serum levels of cytokines and biomarkers for inflammation and immune activation, and HIV-associated non-hodgkin B-cell lymphoma risk; 24220912. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23(2):343–9. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Willerslev-Olsen A, Litvinov IV, Fredholm SM, Petersen DL, Sibbesen NA, Gniadecki R, et al. IL-15 and IL-17F are differentially regulated and expressed in mycosis fungoides (MF). Cell Cycle. 2014;13(8):1306–12. 10.4161/cc.28256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Krejsgaard T, Litvinov IV, Wang Y, Xia L, Willerslev-Olsen A, Koralov SB, et al. Elucidating the role of interleukin-17F in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122(6):943–50. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-480889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Miyagaki T, Sugaya M, Suga H, Kamata M, Ohmatsu H, Fujita H, et al. IL-22, but not IL-17, dominant environment in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(24):7529–38. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1192. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Litvinov IV, Jones DA, Sasseville D, Kupper TS. Transcriptional profiles predict disease outcome in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(7):2106–2114. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winkler I, Pyszniak M, Pogoda K, Semczuk A, Gogacz M, Miotla P, et al. Assessment of Th17 lymphocytes and cytokine IL17A in epithelial ovarian tumors. Oncol Rep. 2017;37(5):3107–15. 10.3892/or.2017.5559. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Chen Y-L, Chou C-Y, Chang M-C, Lin H-W, Huang C-T, Hsieh S-F, et al. IL17a and IL21 combined with surgical status predict the outcome of ovarian cancer patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(5):703–11. 10.1530/ERC-15-0145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Park WG, Li L, Appana S, Wei W, Stello K, Andersen DK, et al. Unique circulating immune signatures for recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a pilot study of these conditions with and without diabetes: immune profiling of pancreatic disorders; 31791885. Pancreatology. 2020;20(1):51–9. 10.1016/j.pan.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Janiczek M, Szylberg Ł, Antosik P, Kasperska A, Marszałek A. Expression levels of IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-17RA, and IL-17RC in prostate Cancer with taking into account the histological grade according to Gleason scale in comparison to benign prostatic hyperplasia: in search of new therapeutic options. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020 May 25:4910595–4910597. doi: 10.1155/2020/4910595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Zhao X, Sun X, Li Y, Wang Z, Jiang J, et al. Expression of IL-17A, E, and F and their receptors in human prostatic cancer: comparison with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 2015;75(16):1844–56. 10.1002/pros.23058. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Mohammadipour K, Mansouri R, Salmanpour R, Haghshenas MR, Erfani N. Investigation of Interleukin-17 gene polymorphisms and serum levels in patients with basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Iran J Immunol. 2019;16(1):53–61. doi: 10.22034/IJI.2019.39406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Samadi A, Moossavi S, Salem A, Sotoudeh M, Tuovinen SM, Konttinen YT, et al. Distinctive expression pattern of interleukin-17 cytokine family members in colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(2):1609–1615. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3941-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almahmoudi R, Salem A, Sievilainen M, Sundquist E, Almangush A, Toppila-Salmi S, et al. Extracellular interleukin-17F has a protective effect in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2018;40(10):2155–2165. doi: 10.1002/hed.25207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zielinska K, Karczmarek-Borowska B, Kwasniak K, Czarnik-Kwasniak J, Ludwin A, Lewandowski B, et al. Salivary IL-17A, IL-17F, and TNF-alpha are associated with disease advancement in patients with Oral and oropharyngeal Cancer. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020 Aug 13:3928504–3928508. doi: 10.1155/2020/3928504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naeimi S, Erfani N, Ardekani AM, Ghaderi A. Variation of IL-17A and IL-17F genes in patients with breast cancer in a population from southern Iran. Adv Environ Biol. 2014;8(9):892–897. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Huang S, Wang Z, et al. Association analysis of IL-17A and IL-17F polymorphisms in Chinese Han women with breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34400. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Cong J, Liu R, Wang X, Sheng L, Jiang H, Wang W, et al. Association between interluekin-17 gene polymorphisms and the risk of cervical cancer in a Chinese population. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(8):9567–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lv Q, Zhu D, Zhang J, Yi Y, Yang S, Zhang W. Association between six genetic variants of IL-17A and IL-17F and cervical cancer risk: a case-control study. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(5):3979–3984. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elsissy M, Abdelhafez A, Elmasry M, Salah D. Interleukin-17 gene polymorphism is protective against the susceptibility to adult acute myeloid leukaemia in Egypt: a case-control study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(9):1425–1429. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wróbel T, Gębura K, Wysoczańska B, Dobrzyńska O, Mazur G, et al. IL-17F gene polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to acute myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(9):1551–1555. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1674-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quan Y, Zhou B, Wang Y, Duan R, Wang K, Gao Q, et al. Association between IL17 polymorphisms and risk of cervical cancer in chinese women; 23049595. J Immunol Res. 2012;2012:1–6. 10.1155/2012/258293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Feng H, Ying R, Chai T, Chen H, Ju H. The association between IL-17 gene variants and risk of colorectal cancer in a Chinese population: A case-control study. Biosci Rep. 2019 Nov 29;39(11). 10.1042/BSR20190013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Cho YA, Lee J, Oh JH, Chang HJ, Sohn DK, Shin A, et al. Inflammatory Dietary Pattern, IL-17F Genetic Variant, and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients. 2018 Jun 5;10(6). 10.3390/nu10060724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Al Obeed OA, Vaali-Mohamed M-A, Alkhayal KA, Bin Traiki TA, Zubaidi AM, Arafah M, et al. IL-17 and colorectal cancer risk in the Middle East: gene polymorphisms and expression. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2653–2661. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S161248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samiei G, Yip WK, Leong PP, Jabar MF, Dusa NM, Mohtarrudin N, et al. Association between polymorphisms of interleukin-17A G197A and interleukin-17F A7488G and risk of colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14(Supplement):S299–S305. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.235345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Omrane I, Medimegh I, Baroudi O, Ayari H, Bedhiafi W, Stambouli N, et al. Involvement of IL17A, IL17F and IL23R polymorphisms in colorectal cancer therapy; 26083022. PLos One. 2015;10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Choi WS, Kim O, Yoon JH, Park YG, Nam SW, Lee JY, et al. Association of IL-17A/F polymorphisms with the risk of gastritis and gastric cancer in the Korean population. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2016;12(3):327–36. 10.1007/s13273-016-0037-7.

- 59.Zhao WM, Shayimu P, Liu L, Fang F, Huang XL. Association between IL-17A and IL-17F gene polymorphisms and risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population; 27525907. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016;15(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Hou C, Yang F. Interleukin-17A gene polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to gastric cancer; 26261639. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(6):7378–7384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang N, Yang J, Lu J, Qiao Q, Bao G, Wu T, et al. IL-17 gene polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to gastric cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014;35(10):10025–30. 10.1007/s13277-014-2255-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Kaabachi W. Ben amor a, Kaabachi S, Rafrafi a, Tizaoui K, Hamzaoui K. interleukin-17A and -17F genes polymorphisms in lung cancer. Cytokine. 2014;66(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Musleh M, Bustamante M, Stambuk J, Escandar S, Valladares H, et al. Role of cytokine gene polymorphisms in gastric cancer risk in Chile; 24982364. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(7):3523–30. [PubMed]

- 64.Gao YW, Xu M, Xu Y, Li D, Zhou S. Effect of three common IL-17 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the risk of developing gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1398–1402. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qinghai Z, Yanying W, Yunfang C, Xukui Z, Xiaoqiao Z. Effect of interleukin-17A and interleukin-17F gene polymorphisms on the risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Gene. 2014;537(2):328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu X, Zeng Z, Chen B, Yu J, Xue L, Hao Y, et al. Association between polymorphisms in interleukin-17A and interleukin-17F genes and risks of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(1):86–92. 10.1002/ijc.25027. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Tahara T, Shibata T, Nakamura M, Yamashita H, Yoshioka D, Okubo M, et al. Association between IL-17A, −17F and MIF polymorphisms predispose to CpG island hyper-methylation in gastric cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2010;25(3):471–7. 10.3892/ijmm_00000367. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Zhou B, Zhang P, Wang Y, Shi S, Zhang K, Liao H, et al. Interleukin-17 gene polymorphisms are associated with bladder cancer in a Chinese Han population. Mol Carcinog. 2013;52(11):871–8. 10.1002/mc.21928. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Shibata T, Tahara T, Hirata I, Arisawa T. Genetic polymorphism of interleukin-17A and -17F genes in gastric carcinogenesis. Hum Immunol. 2009;70(7):547–551. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He Y, Du Y, Wei S, Shi J, Mei Z, Qian L, et al. IL-17A and IL-17F single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with lung cancer in Chinese population. Clin Resp J. 2017;11(2):230–242. doi: 10.1111/crj.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Si FZ, Feng YQ, Han M. Association between interleukin-17 gene polymorphisms and the risk of laryngeal cancer in a Chinese population. Genet Mol Res. 2017 Mar 30;16(1). 10.4238/gmr16019076. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Xi X-E, Liu Y, Lu Y, Huang L, Qin X, Li S. Interleukin-17A and interleukin-17F gene polymorphisms and hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma risk in a Chinese population; 25429834. Med Oncol. 2015;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Innocenti F, Owzar K, Cox NL, Evans P, Kubo M, Zembutsu H, et al. A genome-wide association study of overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine in CALGB 80303. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(2):577–84. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Aslani A, Haghshenas MR, Erfani N, Khezri AA. IL17A and IL17F genetic variations in iranian patients with urothelial bladder cancer: a case-control study. Middle East J Cancer. 2021;12(3):377–382. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krajewski W, Karabon L, Partyka A, Tomkiewicz A, Poletajew S, Tukiendorf A, et al. Polymorphisms of genes encoding cytokines predict the risk of high-grade bladder cancer and outcomes of BCG immunotherapy. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2020;45(1):37–47. 10.5114/ceji.2020.94674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Zayed RA, El-Saadany Z, Raslan HN, Ghareeb M, Ibraheem D, Rashed M, et al. IL-17 a and IL-17 F single nucleotide polymorphisms and acute myeloid leukemia susceptibility and response to induction therapy in Egypt. Meta Gene. 2020;26:100773. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2020.100773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cecchin E, De Mattia E, Dreussi E, Montico M, Palazzari E, Navarria F, et al. Immunogenetic markers in IL17F predict the risk of metastases spread and overall survival in rectal cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2020;149:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Assis-Mendonça GR, Lourenço GJ, Delamain MT, de Lima VCC, Colleoni GWB, de Souza CA, et al. Single-nucleotide variants in TGFB1, TGFBR2, IL17A, and IL17F immune response genes contribute to follicular lymphoma susceptibility and aggressiveness. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(10):97-020-00365–4. 10.1038/s41408-020-00365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Hu M, Li N, Li B, Guo J. Association of IL-17 genetic polymorphisms and risk of oral carcinomas and their interaction with environmental factors in a Chinese population. Biomed Res. 2017;28(15):6796–802. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li N, Zhang C, Chen Z, Bai L, Nie M, Zhou B, et al. Interleukin 17A and interleukin 17F polymorphisms are associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma susceptibility in a chinese population; 25579009. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(2):267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen J, Liu X, Huang H, Zhang F, Lu Y, Hu H. High salt diet may promote progression of breast tumor through eliciting immune response; 32721893. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;87:106816. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tong Z, Yan H, Liu W. Interleukin-17F attenuates H2O2-induced cell cycle arrest; 24423465. Cell Immunol. 2014;287(2):74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhou Y, Toh M-L, Zrioual S, Miossec P. IL-17A versus IL-17F induced intracellular signal transduction pathways and modulation by IL-17RA and IL-17RC RNA interference in AGS gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Cytokine. 2007;38(3):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Almahmoudi R, Salem A, Hadler-Olsen E, Svineng G, Salo T, Al-Samadi A. The effect of interleukin-17F on vasculogenic mimicry in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(6):2223–2232. doi: 10.1111/cas.14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xie Y, Sheng W, Xiang J, Ye Z, Yang J. Interleukin-17F suppresses hepatocarcinoma cell growth via inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Investig. 2010;28(6):598–607. doi: 10.3109/07357900903287030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferreira N, Mesquita I, Baltazar F, Silvestre R, Granja S. IL-17A and IL-17F orchestrate macrophages to promote lung cancer. Cell Oncol. 2020;43(4):643–654. doi: 10.1007/s13402-020-00510-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chang SH, Mirabolfathinejad SG, Katta H, Cumpian AM, Gong L, Caetano MS, et al. T helper 17 cells play a critical pathogenic role in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(15):5664–9. 10.1073/pnas.1319051111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Chae W-J, Bothwell ALM. IL-17F deficiency inhibits small intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.De Simone V, Franze E, Ronchetti G, Colantoni A, Fantini MC, Di Fusco D, et al. Th17-type cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-alpha synergistically activate STAT3 and NF-kB to promote colorectal cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2015;34(27):3493–3503. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Juurikka K, Butler GS, Salo T, Nyberg P, Åström P. The role of MMP8 in Cancer: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4506. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wei T, Cong X, Wang X-T, Xu X-J, Min S-N, Ye P, et al. Interleukin-17A promotes tongue squamous cell carcinoma metastasis through activating miR-23b/versican pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(4):6663–80. 10.18632/oncotarget.14255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Lee M-H, Tung-Chieh Chang J, Liao C-T, Chen Y-S, Kuo M-L, Shen C-R. Interleukin 17 and peripheral IL-17-expressing T cells are negatively correlated with the overall survival of head and neck cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9(11):9825–9837. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Niu Y-M, Yuan H, Zhou Y. Interleukin-17 gene polymorphisms contribute to cancer risk. Mediat Inflamm. 2014;2014:128490. doi: 10.1155/2014/128490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(21):1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.