Abstract

Background

Suicide attempt is the most predictive risk factor of suicide. Trauma – especially sexual abuse – is a risk factor for suicide attempt and suicide. A common reaction to sexual abuse is dissociation. Higher levels of dissociation are linked to self-harm, suicide ideation, and suicide attempt, but the role of dissociation in suicidal behavior is unclear.

Methods

In this naturalistic study, ninety-seven acute psychiatric patients with suicidal ideation, of whom 32 had experienced sexual abuse, were included. Suicidal behaviour was assessed with The Columbia suicide history form (CSHF). The Brief trauma questionnaire (BTQ) was used to identify sexual abuse. Dissociative symptoms were assessed with Dissociative experiences scale (DES).

Results

Patients who had experienced sexual abuse reported higher levels of dissociation and were younger at onset of suicidal thoughts, more likely to self-harm, and more likely to have attempted suicide; and they had made more suicide attempts. Mediation analysis found dissociative experiences to significantly mediate a substantive proportion of the relationship between sexual abuse and number of suicide attempts (indirect effects = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.05, 0.28, proportion mediated = 68%). Dissociative experiences significantly mediated the role of sexual abuse as a predictor of being in the patient group with more than four suicide attempts (indirect effects = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.02, 0.19, proportion mediated = 34%).

Conclusion

The results illustrate the importance of assessment and treatment of sexual abuse and trauma-related symptoms such as dissociation in suicide prevention. Dissociation can be a contributing factor to why some people act on their suicidal thoughts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-021-03662-9.

Keywords: Sexual abuse, Trauma, Dissociation, Suicidal behavior, Suicide attempt

Background

Suicide accounts for more than 700,000 deaths yearly worldwide [1]. Suicidal behavior can include different levels of severity from suicide thoughts to death by suicide [2]. Traditional risk factors like depression, hopelessness, most psychiatric disorders, and impulsivity can predict suicide ideation, but such factors poorly predict suicide attempts among suicide ideators. In an ideation-to-action framework to suicide, the progression from suicide ideation to lethal suicidal attempts can be understood as a distinct process. This process can include factors that diminish fear of pain, injury, and death which can increase a person’s capability to attempt suicide [3].

People who are exposed to early traumatic events are at increased risk of attempting suicide compared to the general population [4]. Sexual abuse, especially in childhood, has consistently been associated with suicidal behavior [5]. An early Australian study of 183 young people found the suicide rate of people reporting sexual abuse to be 10.7–13.0 times the national rates at 9 years after inclusion in the study. Of those who reported sexual abuse, 43% reported suicide ideation and 32% reported suicide attempts [6]. Recent meta-analyses have confirmed that childhood sexual abuse is an important risk factor for suicide attempts [7, 8].

A large body of research has identified a relationship between potentially traumatizing events and dissociative symptoms [9]. Dissociation can be understood as a form of detachment and can include depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, fugue states, and identity disorders [10]. Dissociation can include a disconnection from the body that can reduce fear and pain associated with harming the body that can make suicide attempt possible [11].

Several studies have found dissociation to be a predictor of suicide attempts [12–15]. Dissociation has been found to differentiate individuals with a history of suicide attempt from those with suicide ideation alone [11]. Research show that higher levels of dissociation can be an important mediating factor, regardless of psychiatric disorders in the development of self harm and suicide attempt [16].

Dermirkol and colleagues found that childhood maltreatment is a strong predictor of suicide attempts and that “psychache” and dissociation play mediator roles in this relationship [17]. They found dissociation to have a full mediator role in the effect of emotional abuse and physical abuse on suicide attempt and partial mediator roles in the effect of sexual abuse and physical neglect on suicide attempt. However, one limitation of their study was its wide age range, as the effect of the trauma may decrease with age.

A systematic review of the literature confirms there is robust evidence for a mediating role of dissociation in trauma and non-suicidal self-injury, but the literature is lacking evidence of the mediating role of dissociation in suicide ideation and completed suicides [18]. There are, to our knowledge, no studies of the association between dissociation and sexual abuse in suicide risk that differentiates between single- and multi-suicide attempters.

In this study, acute psychiatric patients at suicide risk who had experienced sexual abuse were compared to patients with suicide risk who had not experienced sexual abuse. The role of dissociation in the association between sexual abuse and suicide attempts was thereby analyzed which has the potential to fill a knowledge gap. We predicted that (1) patients having experienced sexual abuse would be more likely to have a history of suicide attempt, (2) they would report higher levels of dissociation, and (3) dissociation would have a mediating effect on the association between sexual abuse and suicide attempts.

Methods

Participants

The participants included were acute psychiatric patients referred to the crisis resolution team at Sørlandet Hospital in Southern Norway. The crisis resolution teams aim to help people experiencing mental health crises, usually related to suicide risk and acute mental illness. The inclusion period was from May 2014 to August 2017. Patients aged between 18 and 65 years referred to the mental health service for suicide risk were included. Suicide risk could include suicide thoughts, suicide threats, suicidal behavior, and suicide attempts. Three hundred sixty-seven patients were asked to participate, 227 patients agreed to participate and 97 completed all measurements included for the analysis in this study. When comparing the patients who agreed to participate with the patient group that did not want to participate there is no significant difference in age, gender or depression. The exclusion criteria were severe substance abuse and the inability to read, speak, or write Norwegian. The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2013/1664/REK sør øst D) approved the study.

Measures

Brief trauma questionnaire (BTQ)

The brief trauma questionnaire (BTQ) [19] is a 10-item self-report questionnaire used to assess experiences of traumatic events. In the present study, the BTQ was included to assess unwanted sexual contact and this experience was labeled “sexual abuse.” The question was asked, “Has anyone ever made or pressed you into having some type of unwanted sexual contact? By “sexual contact,” we mean any contact with someone else and your private parts or between you and somebody else’s private parts. Have this ever happened to you? Yes or no.” Sexual abuse was coded as a dichotomous variable (0 = not present, 1 = present). The psychometric data for the BTQ is somewhat limited, but interrater reliability has been shown to be good for all the primary trauma categories and criterion validity, with associations found consistently between PTSD-symptom severity and BTQ-measured trauma [20].

Dissociative experiences scale (DES)

The dissociative experiences scale (DES) is a 28-item self-report form used to measure dissociative symptoms [21]. The questionnaire is the most widely used self-report measure of dissociation and has been found to give reliable measures of dissociation in clinical and non-clinical populations [21]. In the present study, the total scale score (range 0–100) was calculated by averaging across all 28 items. Pathological dissociation was identified by using 8 items from the DES, DES-T [22].

Columbia suicide history form (CSHF)

The Columbia suicide history form (CSHF) [23] was selected for this study to assess the severity of suicidal behavior and, specifically, an individual’s suicide-attempt history. The CSHF is structured as a screening interview, with 5 questions on suicide ideation, 7 questions on intensity of ideation, 6 questions on suicidal behavior, and 2 questions on lethality evaluations of actual attempts. The interview covers both suicidal behavior during the previous month and lifetime history of suicidal behavior for all the different questions. Suicide attempts are further categorized by the first, latest, and most deadly attempts. Most questions in the interview are yes or no-based, some questions are age-based, and some questions ask for the number of occurrences of suicidal behavior. The CSHF has shown good convergent and divergent validity with other multi-informant suicidal ideation and behavior scales, and it has been validated as a suitable assessment of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior in both clinical and research settings [24].

Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS)

The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) is a standardized rating scale designed to assess symptoms of an ongoing depression [25]. The validity of the scale has been supported in several studies [26]. The MADRS includes 10 phenomena related to depression, and clinicians assess each phenomenon with a rating of 0 to 6.

Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT)

The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire developed by a World Health Organization (WHO) collaboration project to assess whether a person is at risk of alcohol-abuse problems and alcohol dependence [27]. Several studies have found that the questionnaire is a reliable and valid measure for identifying alcohol-abuse problems [28].

Drug-use disorder identification test (DUDIT)

The drug-use disorder identification test (DUDIT) is an 11-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess whether a person is at risk of drug abuse and drug dependence. Research has shown that this is an effective screening in clinically selected groups for drug-related problems [29].

Diagnoses

The diagnoses were reported from the assessment when they first met the crisis resolution team. Some patients had already been diagnosed with a mental illness before they were referred to the crisis resolution team, some patients were diagnosed in their first assessment in the team, and some patients did not report or meet the criteria for a diagnosis within the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders [30].

Procedure

The participants were asked to participate in the study after referral and following their first meeting with clinicians at the hospital. They were all given a written information form and the nature of the study was explained to them. Those who wanted to participate were given a consent form to sign and informed that they would have the right to withdraw at any time.

The clinicians involved in the data collection were all trained to complete the screening interview. This training included a video made by the developers of the CSHF, in addition to an observation of an interview between a researcher and a patient.

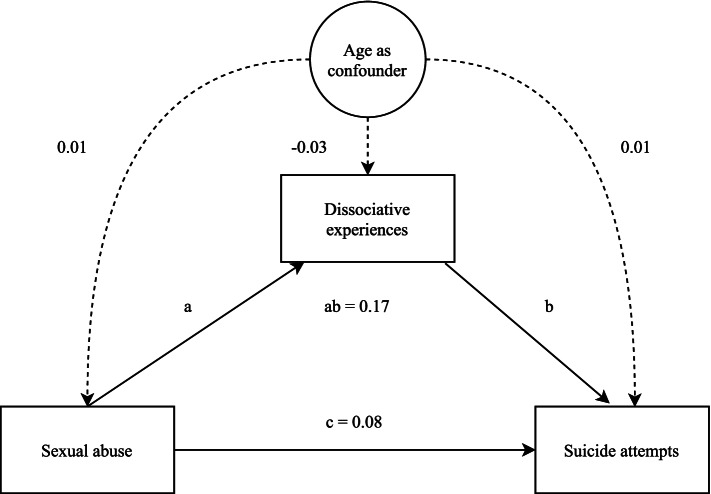

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS [31] and JASP [32]. A descriptive analysis was conducted to compare suicidal behavior in the sexual abuse and no sexual abuse groups. T-tests and chi-square tests were used where appropriate. Mediation analyses was conducted with Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), following the methods outlined by Woody [33], using 100,000 bootstrapped samples and full-information maximum likelihood to handle missing data. Power analysis following methods described by Liu and Wang (2019) [34] indicated low power (0.50) to detect individual mediation effect (highest expected = 0.30). However, given the potential importance of the study and known difficulties in gathering large samples in the population of suicide attempters [35] we continued the analyses. The primary model (Fig. 1) included sexual abuse as a predictor, dissociation as mediator, and number of suicide attempts as dependent variable. Confounders (age and gender) and other mediators (depression, drug abuse, alcohol abuse) were added in separate models. If confounders or additional mediators increased R2, these were added to the model. The best fitting model was the original, with the addition of age as a confounder, and only this model is presented. The same model was used to investigate repeated suicide behavior, defined as being in the 80th percentile of number of suicide attempts (> 2 attempts) and being in the 90th percentile of number of suicide attempts (> 4 attempts). Additional information on scale correlations and fits can be found in supplement 1.

Fig. 1.

Visual depiction of primary SEM model

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients included in the analyses. The most common diagnostic group represented were affective disorders, neurotic and stress-related disorders, personality disorders, and disorders related to substance use. The most-used psychotropics were hypnotics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients included in the analysis, N = 97

| N | % | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.5 | 14.0 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 44 | 45 | ||

| Female | 53 | 55 | ||

| Education in years | 13.1 | 3.4 | ||

| Depression score | 24.8 | 7.3 | ||

| Main diagnosis, ICD-10 | ||||

| F10–19 Disorders related to substance use | 4 | 4.1 | ||

| F20–29 Disorders related to psychosis | 1 | 1.0 | ||

| F30–39 Affective disorders | 41 | 42 | ||

| F40–48 Neurotic and stress-related disorders | 25 | 25.8 | ||

| F50 Eating disorder | 1 | 1.0 | ||

| F60–69 Personality disorders | 12 | 12.3 | ||

| F80–89 Developmental disorders | 2 | 2.0 | ||

| F90–98 Behavioral and emotional disorders | 2 | 2.0 | ||

| Unspecified diagnosis | 9 | 9.8 | ||

| Psychotropics | ||||

| Antidepressant | 25 | 26.6 | ||

| Antipsychotics | 12 | 12.8 | ||

| Mood stabilizers | 12 | 12.8 | ||

| Hypnotics | 29 | 30.9 | ||

| Anxiolytics | 22 | 23.4 | ||

| Central stimulants | 5 | 5.3 | ||

Table 2 shows the clinical variables for the acute psychiatric patients reporting sexual abuse and no sexual abuse. Patients who had experienced sexual abuse scored significantly higher on the AUDIT and DES. The patients who had experienced sexual abuse were younger when they first had thoughts of suicide and more likely to have self-harmed and attempted suicide in their lifetime. The sexual abuse patient group scored higher on the DES and included more patients with pathological dissociation than patients with no experiences of sexual abuse.

Table 2.

Clinical variables for acute psychiatric patients reporting sexual abuse and no sexual abuse

| N = 97 | Sexual abuse n = 31 | No sexual abuse n = 66 | P value | Cohens d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.08 | 0.4 | ||

| Male (n) | 10 | 34 | ||

| Female (n) | 21 | 32 | ||

| MADRS total score | 26.5 | 24.0 | 0.14 | 0.3 |

| AUDIT total score | 32.0 | 11.0 | 0.01 | 0.9 |

| DUDIT total score | 4.2 | 3.3 | 0.59 | 0.1 |

| DES total score | 24.9 | 14.7 | 0.02 | 0.7 |

| DES pathological | 66.7% | 18.2% | 0.01 | 0.6 |

| Suicidal behavior | ||||

| Age of first suicide thought | 16.8 | 23.1 | 0.05 | 0.4 |

| Self-harm lifetime | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 0.7 |

| Suicide attempt lifetime | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| High lethality suicide attempt | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.63 | 0.1 |

| Total number of suicide attempts | 6.7 | 2.0 | 0.07 | 0.4 |

Table 3 displays the results of the bootstrapped mediation analysis of dissociation as a mediator of sexual abuse and number of suicide attempts, corrected for the confounding effect of age. These analyses revealed that dissociative experiences significantly mediated a substantive proportion of the relationship between sexual abuse and number of suicide attempts (indirect effects = 0.17, 95% CI [0.05, 0.28], proportion mediated = 68%). Dissociative experiences did not significantly mediate the role of sexual abuse as a predictor of making more than 2 suicide attempts (indirect effects = 0.07, 95% CI [0.00, 0.15], proportion mediated = 21%). However, dissociative experiences did significantly mediate the role of sexual abuse as a predictor of making more than 4 suicide attempts (indirect effects = 0.11, 95% CI [0.02, 0.19], proportion mediated = 34%).

Table 3.

Statistics for mediation analyses

| Outcome | Age confound predictor variable (95% CI) | Age confound mediating variable (95% CI) | Age confound outcome variable (95% CI) | Direct effects (95% CI) | Indirect effects (95% CI) | Total effects (95% CI) | R2 Outcome | % mediated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of suicide attempts | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.01) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.09 (− 0.15, 0.32) | 0.17 (0.05, 0.28) | 0.25 (0.02, 0.49) | 0.24 | 68% |

| More than 2 attempts | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | − 0.03 (− 0.04, − 0.01) | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.01) | 0.26 (0.07, 0.45) | 0.07 (0, 0.15) | 0.33 (0.15, 0.51) | 0.15 | 21% |

| More than 4 attempts | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.01) | − 0.03 (− 0.04, − 0.01) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.03) | 0.21 (0.02, 0.40) | 0.11 (0.02, 0.19) | 0.32 (0.14, 0.50) | 0.19 | 34% |

Note. Each row represents a separate mediation model. For all three models Sexual abuse is the predictor and dissociative experiences the mediator, and age is confounding variable. All measures are standardized. “Direct effects” describes the relationship between predictor and outcome that is not explained by mediation. “Indirect effects” describes the relationship between predictor and outcome that is explained by mediation. Total effects is the combination of indirect and direct effects

Discussion

Dissociation mediated a substantive proportion of the relationship between sexual abuse and number of suicide attempts. As predicted, psychiatric patients who have experienced sexual abuse are more likely to have self-harmed and attempted suicide than patients who have not experienced sexual abuse. Also as predicted, patients in the sexual abuse group reported more pathological dissociation and higher levels of dissociation. The model further identified dissociation as a significant mediating factor of the predictive value of sexual abuse when identifying patients with more than 4 suicide attempts and close to significant mediating effect for patients with more than 2 attempts. A mechanism can be that dissociation heighten vulnerability to stress and this disposition can be a facilitator of helplessness, hopelessness, intolerable stress, and suicidal behavior [36].

The interpersonal theory of suicide [37] explains suicidal behavior as consisting of both the desire to die and the capability to die. The desire to die can arise from thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and feelings of hopelessness [38]. The capability to engage in suicidal behavior emerges through habituation and opponent processes after repeated exposure to physical pain or fear-inducing experiences [37]. In the present study, sexual abuse can be understood as an exposure to psychological provocative or fear inducing situations, that could be contributing to a desire to die. Dissociation with its physical disconnection from one’s body could be understood as a facilitator of the habituation to fear that creates courage or fearlessness that builds capability to suicide. Self harm and attempting suicide (and multiple suicide attempts) could be building blocks to suicide capability trough the habituation of pain [39]. An implication of this study is that treatment of dissociation should be included in suicide prevention.

Treatment of dissociative reactions often uses a carefully paced, three-stage process that involves building a therapeutic relationship, increasing safety and stability, developing skills in regulating emotions and managing dissociation, processing traumatic memories, and integrating a sense of self. The final work often includes a focus on developing relationships and life quality. In treatment, one must often revisit the different stages over time [40]. The treatment of patients with dissociative disorders (TOP DD), one of the largest and most geographically diverse studies of treatment of dissociative disorders, followed this phase-stage treatment and found a reduction in dissociation, suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, risky behaviors, and substance use [41].

Self harm and suicide attempt is not always easy to separate into two different categories. If the multi-suicide attempts are more an expression to regulate emotions or a form of communication for help, it could be argued that this form of suicidal behaviour is different from suicide attempt where the intension of suicide is higher. These processes could be difficult to detect and understand correctly in an interview. It is important to address the nuances of suicide intension in assessment of suicide attempt and difficult to measure it correctly [42].

In the analysis, age was found to be a confounding variable for the best fitting model. The confounding effect of age might reflect the frequency of sexual abuse experiences, as well as the number of suicide attempts rising with increasing age. Research has suggested that dissociative experiences decrease with age [43]. It is possible to have less dissociation with age and with more lived life have experienced more abuse and more attempted suicide.

Future studies could include a non-clinical population to achieve a more complete understanding of the relationships between trauma, dissociation, and suicidal behavior. It could be that the occurrence and severity of dissociation in a sample of acute psychiatric patients with suicidal behavior is somewhat different from those in the general population. Research has shown that dissociation is present in a variety of different mental disorders [44]. There is evidence of a robust relationship between disruptions in sleep patterns and dissociation [45] and disrupted sleep is common for most psychiatric patients.

The limitations of this study are the relatively small sample and the no sexual abuse group being twice the size of the sexual abuse group. In addition, there was no measure of the duration, severity or impact of sexual abuse on life quality or mental health in general for each individual. The severity of sexual abuse could have had an impact on both dissociation and suicidal behavior. The level of psychological strain caused by sexual abuse is relevant to suicide risk and could be included in future studies. It could also be valuable to explore the nuances of suicide capability in the dissociation-suicide attempt link.

Conclusion

In this study, dissociation mediated a substantive proportion of the relationship between sexual abuse and number of suicide attempts. The results in this study illustrate the importance of assessment and treatment of sexual abuse and trauma-related symptoms such as dissociation in suicide prevention. Dissociation can be a reason why some people act on their suicidal thoughts.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: S1. Table 1 Scale correlations. S1. Table 2 Fit indices for model 1. S1. Table 3 Residual variances model 1. S1. Table 4 Covariances model 1. S1. Table 5 Fit indices for model 2. S1. Table 6 Residual variances model 2. S1. Table 7 Covariances model 2. S1. Table 8 Fit indices for model 3. S1. Table 9 Residual variances model 3. S1. Table 10 Covariances model 3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kirsti Drange, Anne Jorunn Risnes, Helene Wie Ludvigsen, Marie Aaslie Reiråskag, Tor Andre Fjellstad, Viel Karete Helling-Larsen, Linda Esperaas and the Crisis Resolution team at Sørlandets Hospital for their contribution in collecting data.

Abbreviations

- CSHF

The Columbia suicide history form

- BTQ

The Brief trauma questionnaire

- DES

Dissociative experiences scale

- MADRS

The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

- AUDIT

The alcohol use disorders identification test

- DUDIT

The drug-use disorder identification test

- WHO

World Health Organization

- SEM

Structural Equation Modelling

- TOP DD

The treatment of patients with dissociative disorders

Authors’ contributions

NIL, VHØ and SSB contributed in the planning of the project and the study design. SSB collected the data and did most of the writing of the manuscript. VØH and SSB analyzed and interpreted the patient data. TBB did the SEM analysis and writing of the SEM procedure. NIL and VØH was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by a collaboration between University of Oslo and Sørlandet Hospital HF.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Ethical Committee for Medical and Health Research for Southern Norway (2013/1664/REK sør øst D) approved the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The participants were all given a written information form and the nature of the study was explained to them. Those who wanted to participate were given a consent form to sign and informed that they would have the right to withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO guidance to help the world reachthe target of reducing suicide rate by 1/3 by 2030 https://www.who.int/news/item/17-06-2021-one-in-100-deaths-is-by-suicide: WHO; 2021.

- 2.O'Connor RC, Nock MK. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klonsky ED, Qiu T, Saffer BY. Recent advances in differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(1):15–20. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakubczyk A, Klimkiewicz A, Krasowska A, Kopera M, Sławińska-Ceran A, Brower K, et al. History of sexual abuse and suicide attempts in alcohol-dependent patients. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(9):1560–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Castroman J, Melhem N, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, et al. Early childhood sexual abuse increases suicidal intent. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):149–154. doi: 10.1002/wps.20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plunkett A, O'Toole B, Swanston H, Oates RK, Shrimpton S, Parkinson P. Suicide risk following child sexual abuse. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(5):262–266. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0262:SRFCSA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng QX, Yong BZJ, Ho CYX, Lim DY, Yeo W-S. Early life sexual abuse is associated with increased suicide attempts: an update meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;99:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zatti C, Rosa V, Barros A, Valdivia L, Calegaro VC, Freitas LH, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide attempt: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from the last decade. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorahy M, van der Hart O. Relationship between trauma and dissociation. In Traumatic Dissociation. Neurobiology and Treatment, ed. E. Vermetten, M.J. Dorathy & D Spiegel. American Psychiatric Association; 2007. pp. 3–30.

- 10.Niciu MJ, Shovestul BJ, Jaso BA, Farmer C, Luckenbaugh DA, Brutsche NE, et al. Features of dissociation differentially predict antidepressant response to ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pachkowski MC, Rogers ML, Saffer BY, Caulfield NM, Klonsky ED. Clarifying the relationship of dissociative experiences to suicide ideation and attempts: a multimethod examination in two samples. Behav Ther. 2021;52:1067–79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Foote B, Smolin Y, Neft DI, Lipschitz D. Dissociative disorders and suicidality in psychiatric outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(1):29–36. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815fa4e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calati R, Bensassi I, Courtet P. The link between dissociation and both suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabasco A, Andover MS. The interaction of dissociation, pain tolerance, and suicidal ideation in predicting suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112661. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertule M, Sebre SB, Kolesovs A. Childhood abuse experiences, depression and dissociation symptoms in relation to suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. J Trauma Dissoc. 2021;22(5):598–614. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Kılıç F, Coşkun M, Bozkurt H, Kaya İ, Zoroğlu S. Self-injury and suicide attempt in relation with trauma and dissociation among adolescents with dissociative and non-dissociative disorders. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(2):172. doi: 10.4306/pi.2017.14.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demirkol ME, Uğur K, Tamam L. The mediating effects of psychache and dissociation in the relationship between childhood trauma and suicide attempts. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2020;21(5):453–460. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi R, Longo L, Fiore D, Carcione A, Niolu C, Siracusano A, et al. Dissociation in stress-related disorders and self-harm: a review of the literature and a systematic review of mediation models. J Psychopathol. 2019;25(3):162–71.

- 19.Schnurr P, Vielhauer M, Weathers F, Findler M. Brief Trauma Questionnaire. 1999.

- 20.Harville EW, Jacobs M, Boynton-Jarrett R. When is exposure to a natural disaster traumatic? Comparison of a trauma questionnaire and disaster exposure inventory. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waller NG, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: a taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(3):300–321. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.3.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, Gould M, Stanley B, Brown G, et al. Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) New York: Columbia University Medical Center; 2008. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatr. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leucht S, Fennema H, Engel RR, Kaspers-Janssen M, Lepping P, Szegedi A. What does the MADRS mean? Equipercentile linking with the CGI using a company database of mirtazapine studies. J Affect Disord. 2017;210(1):287–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Saunder J, Aasland O, Babor T, De La Fuente J, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O'Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(13):1977–1989. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F. Evaluation of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res. 2005;11(1):22–31. doi: 10.1159/000081413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.IBM Corp. SPSS. 27.0 ed. Armonk, NY2020. p. computer software for Mac.

- 32.JASP Team. JASP. 0.14.1 ed2020. p. Computer software.

- 33.Woody E. An SEM perspective on evaluating mediation: what every clinical researcher needs to know. J Exper Psychopathol. 2011;2(2):210–251. doi: 10.5127/jep.010410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Wang L. Sample size planning for detecting mediation effects: a power analysis procedure considering uncertainty in effect size estimates. Multivar Behav Res. 2019;54(6):822–839. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2019.1593814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernandes AC, Dutta R, Velupillai S, Sanyal J, Stewart R, Chandran D. Identifying suicide ideation and suicidal attempts in a psychiatric clinical research database using natural language processing. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25773-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orbach I. Dissociation, physical pain, and suicide: a hypothesis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24(1):68–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(12):1313. doi: 10.1037/bul0000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith PN, Cukrowicz KC. Capable of suicide: a functional model of the acquired capability component of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(3):266–275. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bailey TD, Brand BL. Traumatic dissociation: theory, research, and treatment. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2017;24(2):170. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brand BL, McNary SW, Myrick AC, Classen CC, Lanius R, Loewenstein RJ, et al. A longitudinal naturalistic study of patients with dissociative disorders treated by community clinicians. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2013;5(4):301. doi: 10.1037/a0027654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suominen K, Isometsä E, Ostamo A, Lönnqvist J. Level of suicidal intent predicts overall mortality and suicide after attempted suicide: a 12-year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torem MS, Hermanowski RW, Curdue KJ. Dissociation phenomena and age. Stress Med. 1992;8(1):23–25. doi: 10.1002/smi.2460080104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyssenko L, Schmahl C, Bockhacker L, Vonderlin R, Bohus M, Kleindienst N. Dissociation in psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis of studies using the dissociative experiences scale. Am J Psychiatr. 2018;175(1):37–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17010025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giesbrecht T, Smeets T, Leppink J, Jelicic M, Merckelbach H. Acute dissociation after 1 night of sleep loss. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2013;1(S):150–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: S1. Table 1 Scale correlations. S1. Table 2 Fit indices for model 1. S1. Table 3 Residual variances model 1. S1. Table 4 Covariances model 1. S1. Table 5 Fit indices for model 2. S1. Table 6 Residual variances model 2. S1. Table 7 Covariances model 2. S1. Table 8 Fit indices for model 3. S1. Table 9 Residual variances model 3. S1. Table 10 Covariances model 3.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.