Abstract

Background:

Malignant transformation (MT) of low-grade astrocytoma (LGA) triggers a poor prognosis in benign tumors. Currently, factors associated with MT of LGA have been inconclusive. The present study aims to explore the risk factors predicting LGA progressively differentiation to malignant astrocytoma.

Materials and Methods:

The study design was a retrospective cohort study of medical record reviews of patients with LGA. Using the Fire and Grey method, the competing risk regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with MT, using both univariate and multivariable analyses. Hence, the survival curves of the cumulative incidence of MT of each covariate were constructed following the final model.

Results:

Ninety patients with LGA were included in the analysis, and MT was observed in 14.4% of cases in the present study. For MT, 53.8% of patients with MT transformed to glioblastoma, while 46.2% differentiated to anaplastic astrocytoma. Factors associated with MT included supratentorial tumor (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR] 4.54, 95% CI 1.08–19.10), midline shift >1 cm (SHR 8.25, 95% CI 2.18–31.21), nontotal resection as follows: Subtotal resection (SHR 5.35, 95% CI 1.07–26.82), partial resection (SHR 10.90, 95% CI 3.13–37.90), and biopsy (SHR 11.10, 95% CI 2.88–42.52).

Conclusion:

MT in patients with LGA significantly changed the natural history of the disease to an unfavorable prognosis. Analysis of patients' clinical characteristics from the present study identified supratentorial LGA, a midline shift more than 1 cm, and extent of resection as risk factors associated with MT. The more extent of resection would significantly help to decrease tumor burden and MT. In addition, future molecular research efforts are warranted to explain the pathogenesis of MT.

Keywords: Diffuse astrocytoma, high-grade glioma, low-grade glioma, malignant transformation

Introduction

Astrocytomas are divided into four grades based on the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) central nervous system (CNS) tumor classification. These tumors are usually categorized as low-grade and high-grade astrocytomas. Low-grade astrocytomas (LGAs), including pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO I) and diffuse astrocytoma (WHO II), are benign tumors that have a prognosis significantly longer than high-grade tumors. The median survival time of diffuse astrocytoma ranges from 44 to 57 months, while anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO III) and glioblastoma prognosis (WHO IV) had a median survival time ranging from 15 to 24 months and 11 to 14 months, respectively.[1,2,3]

Malignant transformation (MT) of low-grade gliomas, including fibrillary astrocytoma, diffuse astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, mixed oligoastrocytoma, and ganglioglioma, has been reported in 19.5%–21%.[4,5,6,7] In addition, Broniscer et al. revealed the 10-year cumulative incidence of MT was 3.8%, and the median time of MT was 5.1 years.[7] Although the pathogenesis of MT has been unknown, factors associated with this rare event have been reported. Murphy et al. reported older age, male gender, multiple tumors, chemotherapy alone, and the extent of resection were potential predictors of MT, whereas common genetic profiling of MT was TP53 overexpression, deletions of RB1, CDKN2A, and PTEN pathway abnormalities.[6,7] However, the heterogeneity of the study population was observed from previous studies. Oligodendroglioma, mixed oligoastrocytoma, and other gliomas were included in the study.[4,5,6,7]

In addition, benign tumors can develop to malignancy when patients have to wait for long-term follow-up. If death occurs before MT during the follow-up period, the MT rate will be changed from another competing event.[8] From this concept, we performed a competing risk regression to evaluate clinical characteristics associated with MT in LGA patients.

Materials and Methods

Study population

According to the primary objective, the sample size was calculated using the log-rank test formula.[9] Using data from the study of Murphy et al.,[6] total resection was significantly associated with MT (hazard ratio [HR] 0.47, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.31–0.72) and proportion of total resection group was found in 34.9%. Therefore, these parameters were performed for sample size estimation at the alpha of 0.05 and beta of 0.2 via web-based calculator.[10] The sample size comprised at least 61 patients for testing the hypothesis.

The study was conducted with a medical record review and included all patients newly diagnosed with pilocytic astrocytoma and diffuse astrocytoma between January 2003 and December 2018 in the tertiary hospital of southern Thailand. Some patients were a part of the multicenter CNS tumor registry of Thailand, which was published and had the endpoint of study with death.[1] The histological diagnosis was confirmed by a pathologist, according to the 2016 WHO Classification of CNS tumors.[11]

The excluded criteria were as follows; patients with mixed oligoastrocytoma or other gliomas and unavailable imaging. Moreover, patients who obtained tissue for diagnosis by free-hand biopsy or ultrasound-guided biopsy were excluded, whereas patients with a stereotactic biopsy were not excluded in the present study. Preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were reviewed by a neurosurgeon, such as tumor size, location, side, midline shift. Moreover, a tumor volume calculation was performed based on a prior study of Tunthanathip and Madteng.[12]

The extent of resection was assessed from postoperative imaging and was divided into four groups as follows: Total resection (no visible residual tumor both enhanced and unenhanced portions), subtotal resection (>90% of resection), partial resection (>50% of resection), and biopsy (<5%).[13,14]

In our institute, the postoperative MRIs were routinely performed every 3–6 months for the follow-up purpose. We assess each visit's outcome according to the revised RECIST guidelines (version 1.1).[15] In detail, progressive disease was defined as increased size of tumors of at least 20%, the absolute growth of tumors of at least 5 mm or the appearance of one or more new lesions.[15]

MT was defined as a tumor progressively differentiated to high-grade astrocytoma with histology-confirmed evidence of at least WHO III astrocytoma.[4,5,6,7] Besides, patients' death status was assessed from the Office of Central Civil-Registration on June 30, 2020. A human research ethics committee approved the present study. The present study did not require informed consent from patients because the study design was the retrospective approach. Besides, the patients' identification numbers were encoded before analysis.

Statistical analysis

The endpoint of the study was the MT from which the starting date was the date of diagnosis of LGA and the endpoint of the study was the date of histology-confirmed diagnosis of MT by a pathologist or until June 2020 as the exiting date.

Descriptive statistics were used for describing the baseline characteristics of the patients. The Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test were performed for comparing prognosis between MT group and non-MT group. Using Cox regression analysis, the effect of MT on survival time was analyzed and reported as an HR with 95% CI.

Using Nelson–Aalen estimator, the nonparametric test was performed to describe MT's overall cumulative hazard rate function. Since death is another event that affects the rate at which MT events occur, we use Fine and Gray's competing risk regression analysis to assess the risk associated with MT.[16,17] The subdistribution HR (SHR) was used instead of HR to report MT's risk in both univariate and multivariable analyses. For fitting the model, candidate variables that had a P = 0.1 or less in univariate analysis were analyzed in a multivariable model with backward stepwise selection. The proposed model was considered by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). After fitting the model, each covariate's survival curve was plotted for estimating the cumulative incidence of MT in each covariate.[18,19] Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, TX, USA, SN 401606310234).

Results

Initially, 101 patients who were newly diagnosed with LGA were reviewed. Eleven patients were excluded with unavailable imaging and final diagnosis of mixed glioma. Therefore, 90 patients were analyzed, and baseline clinical characteristics were summarized, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Base-line characteristics of patients newly diagnosed low-grade astrocytoma (n=90)

| Factor | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 47 (52.2) |

| Female | 43 (47.8) |

| Mean age-year (SD) | 35.7 (19.3) |

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Seizure | 46 (51.1) |

| Progressive headache | 37 (41.1) |

| Weakness | 20 (22.2) |

| Visual disturbance | 9 (10.0) |

| Ataxia | 6 (6.7) |

| Behavior change | 1 (1.1) |

| Preoperative KPS score | |

| <80 | 28 (31.1) |

| ≥80 | 62 (68.9) |

| Location | |

| Frontal lobe | 33 (36.7) |

| Temporal lobe | 16 (17.8) |

| Corpus callosum | 10 (11.1) |

| Cerebellum | 9 (10.0) |

| Sellar/suprasellar area | 6 (6.7) |

| Parietal lobe | 4 (4.4) |

| Brainstem | 3 (3.3) |

| Basal ganglion | 3 (3.3) |

| Thalamus | 3 (3.3) |

| Occipital lobe | 1 (1.1) |

| Periventricular area | 1 (1.1) |

| Pineal gland | 1 (1.1) |

| Site of tumor | |

| Left | 33 (36.7) |

| Right | 33 (36.7) |

| Midline | 22 (24.4) |

| Bilateral sites (for multiple lesions) | 2 (2.2) |

| Mean maximum diameter of tumor-cm (SD) | 5.5 (2.0) |

| Mean tumor volume-cm3 (SD) | 58.0 (48.0) |

| Eloquent area | 35 (38.9) |

| Preoperative hydrocephalus | 24 (26.7) |

| Preoperative leptomeningeal dissemination | 5 (5.6) |

| Preoperative multiple lesions | 4 (4.4) |

| Mean preoperative midline shift-cm (SD) | 4 (4.4) |

| Extent of resection | |

| Total resection | 13 (14.4) |

| Subtotal resection | 17 (18.9) |

| Partial resection | 26 (28.9) |

| Stereotactic biopsy | 34 (37.8) |

| Postoperative radiotherapy | 58 (64.4) |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |

| No | 87 (95.6) |

| Temozolomide | 2 (2.2) |

| Vincristine and cyclophosphamide | 2 (2.2) |

| Postoperative KPS score | |

| <80 | 36 (40.0) |

| ≥80 | 54 (60.0) |

| Histology of the first diagnosis | |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | 14 (15.6) |

| Diffuse astrocytoma | 72 (80.0) |

| Gemistocytic astrocytoma | 2 (2.2) |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | 2 (2.2) |

SD – Standard deviation; KPS – Karnofsky performance status

Nearly equal proportions of males and females were 52.2% and 47.8%, respectively. Seizure, progressive headache, and hemiparesis were the first and third common clinical presentations of the eligible patients. The typical location of pilocytic astrocytoma was the cerebellum and suprasellar region of 7/14 (50.0%) and 5/14 (35.7%), while the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and corpus callosum were the common location of diffuse astrocytoma in 32/72 (44.4%), 16/72 (22.2%), and 8 (11.1%), respectively. Moreover, 91% of astrocytoma with WHO grade II were in the supratentorial location, while more than half (58.1%) of WHO Grade I astrocytoma were placed in the infratentorial location (Chi-square test, P < 0.001).

All eligible patients underwent an operation for histological diagnosis. Therefore, the first diagnosis was diffuse astrocytoma (80%), pilocytic astrocytoma (15.6%), gemistocytic astrocytoma (2.2%), and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (2.2%). Total tumor resection was observed in 14.4%, and more than two-thirds of patients received postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. Furthermore, five patients received postoperative chemotherapy.

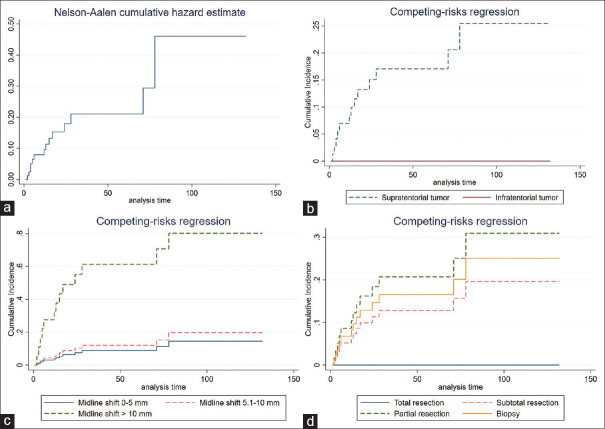

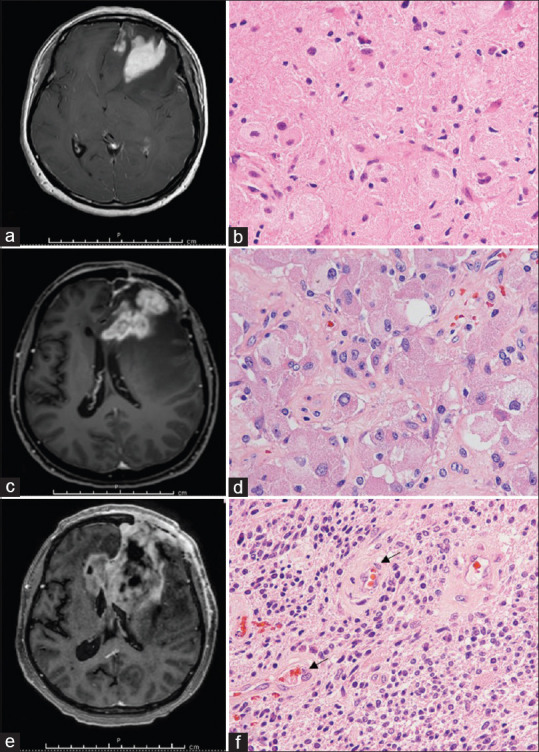

MT occurred 14.4% among the study population when the median time of follow-up was 20 months (interquartile range [IQR] 36 months), and the median time of MT was 13 months (IQR 21.5 months). The clinical characteristics of patients who developed MT during the follow-up period are listed in Table 2. More than half of MT was transformed into glioblastoma, whereas 46.2% of MT turned to anaplastic astrocytoma, as shown in Figure 1a-f and Figure 2a-d. Moreover, almost all patients with MT had never been exposed to radiotherapy before, and all of MT patients had never received adjuvant chemotherapy before MT.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with malignant transformation (n=13)

| Factor | n (%) |

|---|---|

| MT | 13/90 (14.4) |

| Progressive disease without MT | 36/90 (40.0) |

| Extent of resection at MT | |

| Subtotal resection | 6 (46.2) |

| Partial resection | 6 (46.2) |

| Biopsy | 1 (7.7) |

| History of exposure RT | |

| No | 12 (92.3) |

| Radiotherapy before MT | 1 (7.7) |

| Histology at MT | |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 6 (46.2) |

| Glioblastoma | 7 (53.8) |

MT – Malignant transformation; RT – Radiotherapy

Figure 1.

Illustrative cases of malignant transformation of diffuse astrocytoma. (a) Preoperative T1 weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging showing left frontal mass. (b) H and E stain showing moderate cellularity with nuclear atypia of astrocytes. (c) T1 weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging at 4 months later showing progressive left frontal mass with corpus callosum involvement. (d) H and E stain showing an anaplastic transformation, including astrocytes with pleomorphism. (e) T1 weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging at 8 months later showing left frontal tumor crossing to the right side. (f) H and E stain showing glioblastoma features, including hypercellularity of astrocytes and endothelial proliferation (arrow)

Figure 2.

Anaplastic transformation illustrative case of pilocytic astrocytoma. (a) Preoperative T1 weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging showing an enhanced suprasellar mass. (b) H and E stain showing astrocytic cells neoplastic astrocytes in the glial fibrillary background, with numerous Rosenthal fibers (arrows). (c) T1 weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging at 3 years later showing the larger residual tumor. (d) H and E stain showing an anaplastic transformation, including increased cellularity and pleomorphism of tumor cells with multinucleated cells (circle) and mitoses (arrows)

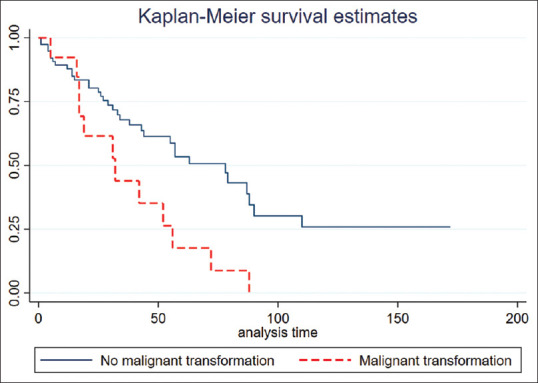

As shown in Figure 3, MT of LGA was significantly associated with poor prognosis (log-rank test, P = 0.006). The median survival time of patients without MT was 78 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 55.2–100.7), whereas patients with MT had a median survival time of 32.0 months (95% CI 11.3–52.6). Using Cox regression analysis, MT significantly affected shortening survival time as HR 2.46 (95% CI 1.26–4.80, P = 0.008).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing malignant transformation group had a significantly poorer prognosis than nonmalignant transformation (log-rank test, P = 0.006)

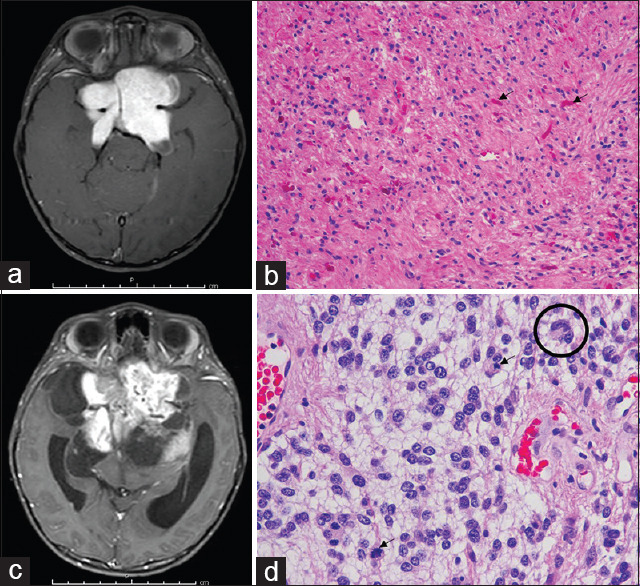

MT was the failure event in the present study that is likely to occur over time, as shown in Figure 4a. Patients with LGA risk to MT were 8.2% in 1-year probability, and the 2-year risk of MT in patients was 16.6%. The MT risk was steady at 19.4% when patients were followed up in the 3rd year, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Survival curve of the cumulative incidence of malignant transformation each factor. (a) Nelson-Aalen estimator of the cumulative hazard function. (b) Supratentorial tumor. (c) Midline shift on preoperative imaging. (d) The extent of resection

Table 3.

Risk of malignant transformation in patients with low-grade astrocytoma overtime

| Follow-up time (months) | Proportion of risk to malignant transformation (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| 12 | 8.2 (3.7–1.8) |

| 24 | 16.1 (8.7–31.4) |

| 36 | 19.7 (10.6–36.7) |

| 48 | 19.7 (10.6–36.7) |

| 60 | 19.7 (10.6–36.7) |

CI – Confidence interval

Factor associated with malignant transformation by the competing risk regression analysis

Various clinical factors were analyzed in the univariate analysis by competing risk regression. Significant factors comprised supratentorial tumor (SHR 7.68, 95% CI 1.78–33.1), midline shift of more than 1 cm from preoperative imaging (SHR 10.29, 95% CI 2.89–35.67), nontotal resection as follows: Subtotal resection (SHR 12.51, 95% CI 2.59–60.44), partial resection (SHR 21.20, 95% CI 7.02–64.27), and biopsy (SHR 16.57, 95% CI 4.68–58.40). In addition, tumors with WHO Grade 2 tended to risk MT.

For multivariable analysis, candidate factors were analyzed with backward stepwise selection. The model which had the least AIC comprised supratentorial tumor (SHR 4.54, 95% CI 1.08–19.10), midline shift of more than 1 cm from preoperative imaging (SHR 8.25, 95% CI 2.18–31.21), nontotal resection as follows: Subtotal resection (SHR 5.35, 95% CI 1.07–26.82), partial resection (SHR 10.90, 95% CI 3.13–37.90), and biopsy (SHR 11.10, 95% CI 2.88–42.52), as shown in Table 4. Subsequently, the significant covariates in the model have constructed the survival curve for estimating the cumulative incidence of MT in each covariate, as shown in Figure 4b-d.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for malignant transformation of low-grade astrocytoma

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| SHR (95%CI) | P | SHR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <40 | Reference | |||

| ≥40 | 0.75 (0.24–2.34) | 0.62 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 1.22 (0.41–3.57) | 0.36 | ||

| Seizure | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.55 (1.87–1.61) | 0.27 | ||

| Preoperative KPS | ||||

| <80 | Reference | |||

| ≥80 | 1.03 (0.33–3.20) | 0.95 | ||

| Location | ||||

| Frontal lobe* | 2.46 (0.81–7.43) | 0.12 | ||

| Temporal lobe* | 0.73 (0.17–3.01) | 0.67 | ||

| Corpus callosum* | 2.19 (0.45–10.66) | 0.32 | ||

| Eloquent area* | 0.88 (0.29–2.63) | 0.82 | ||

| Sellar/suprasellar area* | 1.44 (0.22–9.29) | 0.69 | ||

| Supratentorial tumor* | 7.68 (1.78–33.1) | <0.001 | 4.54 (1.08–19.10) | <0.001 |

| WHO Grade I* | 0.54 (0.06–4.23) | 0.10 | 1.14 (0.10–12.92) | 0.91 |

| Midline shift (cm) | ||||

| 0–0.50 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 0.51–1.00 | 1.39 (0.34–5.57) | 0.63 | 1.18 (0.30–4.53) | 0.80 |

| >1.00 | 10.29 (2.89–35.67) | <0.001 | 8.25 (2.18–31.21) | 0.002 |

| Extent of resection | ||||

| Total resection | Reference | Reference | ||

| Subtotal resection | 12.51 (2.59–60.44) | 0.001 | 5.35 (1.07–26.82) | <0.001 |

| Partial resection | 21.20 (7.02–64.27) | 0.001 | 10.90 (3.13–37.90) | <0.001 |

| Biopsy | 16.57 (4.68–58.40) | 0.001 | 11.10 (2.88–42.52) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative RT* | 1.03 (0.31–3.36) | 0.96 | ||

| Postoperative KPS | ||||

| <80 | Reference | |||

| ≥80 | 0.51 (0.06–3.96) | 0.52 | ||

*Data show only “yes group” while reference groups (no group) are hidden. KPS – Karnofsky performance status; CI – Confidence interval; RT – Radiotherapy; SHR – Subdistribution hazard ratio; WHO – World health organization

Discussion

MT of LGA is the process by which benign astrocytes turn malignant. When MT developed, the prognosis of patients with LGA accelerated downward and had a significantly shorter survival time than the nonMT group. In the present study, MT of LGA developed in 14.4%, and the median time to MT was 13 months. The results in the present study were in concordance with prior studies. The incidence of MT in low-grade gliomas has been reported in 3.8%–21%,[6,7] and Chaichana et al. reported the median latency of MT ranging from 13 to 66 months.[4] However, various methodologies and definitions from prior studies were observed in the literature review. Heterogeneity of low-grade gliomas such as fibrillary astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and mixed glioma may be an influence on MT rate and time to MT, whereas the study population of the present study were focused on astrocytoma. In addition, MT in prior publications included both histology-confirmed MT and imaging characteristic MT,[6] whereas MT in the present study excluded cases without a histological diagnosis.

Clinical predictors associated with MT in the present study were observed as follows: Supratentorial LGA, a preoperative midline shift of more than 1 cm and extent of resection. Supratentorial astrocytoma was significantly prone towards MT, these may be related to the WHO grading of LGA. Although the WHO grading was not significantly associated with MT, LGA with WHO Grade II tended to be MT's risk factor. Chaichana et al. reported that fibrillary astrocytoma, which is WHO Grade II, according to the 2007 CNS tumor classification, was significantly associated with MT.[4]

Midline shift of more than 1 cm was one of the predictors of MT in the present study. As the author's knowledge, this factor has never been reported as an MT predictor, but several studies observed greater tumor size or volume were associated with MT.[4,20,21] Peritumoral edema has been reported as a typical finding of malignant gliomas and contributed as a prognostic factor.[22] These regions promote tumor cell invasion from the blood-brain barrier impairment that may be the mechanism of MT.[23,24] Therefore, our findings that a midline shift of more than 1 cm increased the risk of MT should be further explored with a larger cohort or meta-analysis in the future.

The extent of resection has been considered as a predictor associated with MT in previous studies. Kiliç et al. and Murphy et al. reported that total tumor resection was risk factors of MT. Total tumor resection is the critical factor that modified the patient's prognosis and MT event because residual tumors could transform over time.[6,25] Moreover, total tumor resection has broadly been known as a prognostic factor for increased survival time.[26,27,28] When patients develop the event of death competing MT event, the probability of MT will be directly interfered. Hence, the new survival analysis concept has been published in several neurosurgical conditions such as meningioma, metastases, and cerebral aneurysms.[29,30,31] In addition, multiple lesions of low-grade glioma were reported as a preventative factor of MT.[6] The findings may be an effect from competing events of patients with multiple lesions associated with poor prognosis.[32,33]

Several variables have been reported as MT predictors, but these are still inconclusive. Tom et al. reported that males were associated with MT, while females were a risk factor of MT in the study of Murphy et al. Furthermore, older age was reported as related to MT,[6] whereas Rotariu et al. observed that MT frequently was found in younger patients.[34]

Although the present study is the first paper proposing MT predictors of LGA to the authors' knowledge by Fine and Gray's method, several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. Firstly, the biopsy procedure may cause inadequate tissue diagnosis of MT. We managed this bias by eliminating cases that underwent nonstereotactic biopsy. However, the stereotactic biopsy was accepted in the present study because this procedure has been accepted to take adequate tissue for diagnosis in prior studies.[6,18,35] Secondarily, the study design may lead to bias from retrospective studies. However, the prospective study also has limitations by conducting to explore predictors of MT. Because MT does not frequently occur with time-consuming differentiations, a longitudinal follow-up is needed in the prospective cohort study design. We used the multivariable analysis to adjust the results and confounders.[36] Moreover, the propensity score approach and meta-analysis are alternative ways to explore focused interventions or predictors.[36,37,38] Third, the present study reported that only clinical predictors of MT and genetic investigation should be conducted. From molecular findings, the pathogenesis of MT has been discovered and explains clinical predictors. Glioma with wild type isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) was associated with MT in the study of Tom et al.,[20] while Broniscer et al. studied 9 tissue samples of MT and found that the common molecular pathways of MT were TP53 overexpression, alteration of PTEN, RB1, and CDKN2A.[7] Moreover, Park et al. studied in 3 MT patients with IDH1-mutated gliomas using next-generation sequencing technology which found an altered genetic expression in U2AF2, TCF12, and ARID1A.[39]

Conclusion

MT in patients with LGA significantly changed the natural history of the disease to an unfavorable prognosis. Supratentorial LGA, a midline shift of more than 1 cm, and the extent of resection as risk factors associated with MT. Particularly, total tumor resection, the more extent of resection would significantly help to decrease tumor burden and MT. In addition, future molecular research efforts are warranted to explain the pathogenesis of MT.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by the Health Systems Research Institute (Thailand; grant no. 63-078).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tunthanathip T, Ratanalert S, Sae-Heng S, Oearsakul T, Sakaruncchai I, Kaewborisutsakul A, et al. Prognostic factors and nomogram predicting survival in diffuse astrocytoma. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2020;11:135–43. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3403446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong X, Noorbakhsh A, Hirshman BR, Zhou T, Tang JA, Chang DC, et al. Survival trends of Grade I, II, and III astrocytoma patients and associated clinical practice patterns between 1999 and 2010: A SEER-based analysis. Neurooncol Pract. 2016;3:29–38. doi: 10.1093/nop/npv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaichana KL, McGirt MJ, Laterra J, Olivi A, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Recurrence and malignant degeneration after resection of adult hemispheric low-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:10–7. doi: 10.3171/2008.10.JNS08608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakarunchai I, Sangthong R, Phuenpathom N, Phukaoloun M. Free survival time of recurrence and malignant transformation and associated factors in patients with supratentorial low-grade gliomas. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96:1542–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy ES, Leyrer CM, Parsons M, Suh JH, Chao ST, Yu JS, et al. Risk factors for malignant transformation of low-grade glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100:965–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.12.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broniscer A, Baker SJ, West AN, Fraser MM, Proko E, Kocak M, et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of malignant transformation of low-grade glioma in children. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:682–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein JP. Modelling competing risks in cancer studies. Stat Med. 2006;25:1015–34. doi: 10.1002/sim.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenfeld DA. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics. 1983;39:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohn MA, Senyak J. Sample Size Calculators. [Last accessed on 2021 May 25]. Available from: https://sample-size.net/sample-size-survival-analysis/

- 11.Gupta A, Dwivedi T. A simplified overview of world health organization classification update of central nervous system tumors 2016. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2017;8:629–41. doi: 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_168_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tunthanathip T, Madteng S. Factors associated with the extent of resection of glioblastoma. Precis Cancer Med. 2020;3:12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Im JH, Hong JB, Kim SH, Choi J, Chang JH, Cho J, et al. Recurrence patterns after maximal surgical resection and postoperative radiotherapy in anaplastic gliomas according to the new 2016 WHO classification. Sci Rep. 2018;8:777. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-19014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunthanathip T, Kanjanapradit K. Glioblastoma multiforme associated with arteriovenous malformation: A case report and literature review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23:103–6. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_219_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E, Ford R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, et al. RECIST 1.1-Update and clarification: From the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer. 2016;62:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36:4391–400. doi: 10.1002/sim.7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Competing-Risks Regression. [Last accessed on 2020 May 09]. Available from: https://www.stata.com/features/overview/competing-risks-regression/

- 19.Stcurve-Stata. [Last accessed on 2020 May 09]. Available from: https://www.stata.com/manuals/ststcurve.pdf .

- 20.Tom MC, Park DY, Yang K, Leyrer CM, Wei W, Jia X, et al. Malignant transformation of molecularly classified adult low-grade glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105:1106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreth FW, Faist M, Rossner R, Volk B, Ostertag CB. Supratentorial World Health Organization Grade 2 astrocytomas and oligoastrocytomas. A new pattern of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1997;79:370–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970115)79:2<370::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu CX, Lin GS, Lin ZX, Zhang JD, Chen L, Liu SY, et al. Peritumoral edema on magnetic resonance imaging predicts a poor clinical outcome in malignant glioma. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2769–76. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blystad I, Warntjes JB, Smedby Ö, Lundberg P, Larsson EM, Tisell A. Quantitative MRI for analysis of peritumoral edema in malignant gliomas. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin ZX. Glioma-related edema: New insight into molecular mechanisms and their clinical implications. Chin J Cancer. 2013;32:49–52. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiliç T, Ozduman K, Elmaci I, Sav A, Necmettin Pamir M. Effect of surgery on tumor progression and malignant degeneration in hemispheric diffuse low-grade astrocytomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:549–52. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2002.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majchrzak K, Kaspera W, Bobek-Billewicz B, Hebda A, Stasik-Pres G, Majchrzak H, et al. The assessment of prognostic factors in surgical treatment of low-grade gliomas: A prospective study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:1135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanai N, Berger MS. Glioma extent of resection and its impact on patient outcome. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:753–64. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000318159.21731.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaewborisutsakul A, Sae Heng S, Kitsiripant, Benjhawaleemas P. The first awake craniotomy for eloquent glioblastoma in Southern Thailand. J Health Sci Med Res. 2020;38:61–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Champeaux C, Houston D, Dunn L, Resche Rigon M. Intracranial WHO Grade I meningioma: A competing risk analysis of progression and disease specific survival. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019:2541–9. doi: 10.1007/s00701-019-04096-9. doi: 10.1007/s00701-019-04096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas JT, Jr, Colmer HG, 4th, White L, Fitzgerald N, Isom S, Bourland JD, et al. Competing risk analysis of neurologic versus nonneurologic death in patients undergoing radiosurgical salvage after whole-brain radiation therapy failure: Who actually dies of their brain metastases? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura T, Ochiai C, Kawai K, Morita A, Saito N. How definitive treatment affects the rupture rate of unruptured cerebral aneurysms: A competing risk survival analysis. J Neurosurg. 2019;132:1–6. doi: 10.3171/2018.11.JNS181781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh G, Mehrotra A, Sardhara J, Das KK, Jamdar J, Pal L, et al. Multiple glioblastomas: Are they different from their solitary counterparts? Asian J Neurosurg. 2015;10:266–71. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.162685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tunthanathip T, Sangkhathat S, Tanvejsilp P, Kanjanapradit K. The clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of multiple lesions in glioblastomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;195:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rotariu D, Gaivas S, Faiyad Z, Haba D, Iliescu B, Poeata I. Malignant transformation of low grade gliomas into glioblastoma a series of 10 cases and review of the literature. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 21];Rom Neurosurg. 2010 17:403–12. Available from: https://www.journals.lapub.co.uk/index.php/ roneurosurgery/article/view/521 . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taweesomboonyat C, Tunthanathip T, Sae-Heng S, Oearsakul T. Diagnostic yield and complication of frameless stereotactic brain biopsy. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2019;10:78–84. doi: 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_166_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani AR, Vahedi M. How to control confounding effects by statistical analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5:79–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tunthanathip T, Sangkhathat S. Temozolomide for patients with wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 glioblastoma using propensity score matching. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;191:105712. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tunthanathip T, Mamueang K, Nilbupha N, Maliwan C, Bejrananda T. No association between isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation and increased survival of glioblastoma: A meta-analysis. J Pharm Negat Results. 2020;11:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park CK, Park I, Lee S, Sun CH, Koh Y, Park SH, et al. Genomic dynamics associated with malignant transformation in IDH1 mutated gliomas. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43653–66. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]