Abstract

People living with severe mental illness (SMI) are one of the most marginalized groups in society. Interventions which aim to improve their social and economic participation are of crucial importance to clinicians, policy‐makers and people with SMI themselves. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on social interventions for people with SMI published since 2016 and collated our findings through narrative synthesis. We found an encouragingly large amount of research in this field, and 72 papers met our inclusion criteria. Over half reported on the effectiveness of interventions delivered at the service level (supported accommodation, education or employment), while the remainder targeted individuals directly (community participation, family interventions, peer‐led/supported interventions, social skills training). We identified good evidence for the Housing First model of supported accommodation, for the Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment, and for family psychoeducation, with the caveat that a range of models are nonetheless required to meet the varied housing, employment and family‐related needs of individuals. Our findings also highlighted the importance of contextual factors and the need to make local adaptations when “importing” interventions from elsewhere. We found that augmentation strategies to enhance the effectiveness of social interventions (particularly supported employment and social skills training) by addressing cognitive impairments did not lead to transferable “real life” skills despite improvements in cognitive function. We also identified an emerging evidence base for peer‐led/supported interventions, recovery colleges and other interventions to support community participation. We concluded that social interventions have considerable benefits but are arguably the most complex in the mental health field, and require multi‐level stakeholder commitment and investment for successful implementation.

Keywords: Social interventions, severe mental illness, community‐based interventions, supported accommodation, supported education, supported employment, community participation, family interventions, peer‐supported interventions, social skills training

The high social and economic costs of severe mental illness (SMI) are well recognized, with clear negative impacts on patients, their families and the wider society1, 2. The World Economic Forum has estimated that mental ill‐health will account for more than half the global economic burden attributable to non‐communicable diseases by 2030 3 . People with SMI are at greater risk of poverty, unemployment and poor housing, factors which impact negatively on their social inclusion and exacerbate mental ill‐health. Consequently, clinicians, policy‐makers and many other stakeholders are interested in improving social outcomes for this group. Yet, this has proved to be a very challenging task.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Mental Health Action Plan (2013‐2030) 4 specifically emphasizes the need to implement comprehensive, integrated and responsive mental health and social care services in community‐based settings so that “persons affected by these disorders are able to exercise the full range of human rights and to access high‐quality, culturally‐appropriate health and social care in a timely way to promote recovery, in order to attain the highest possible level of health and participate fully in society and at work, free from stigmatization and discrimination”. Similarly, the Australian Government's Productivity Commission (2020) 5 states that “housing, employment services and services that help a person engage with and integrate back into the community, can be as, or more, important than healthcare in supporting a person's recovery”.

However, despite these and many other calls and concerted efforts over recent decades to develop services that can enable people with severe mental health problems to integrate into their local communities, these people remain one of the most excluded groups in society 6 . In the second national survey of psychosis in Australia, only one third of people experiencing a psychotic disorder was employed, and these people were more than twice as likely to report loneliness compared with the general population 7 .

Whilst this situation is in part due to stigma and discrimination, as well as inadequacies in service provision and mental health systems that continue to institutionalize individuals with more complex problems8, 9, symptoms of the illness itself also contribute. Around a third of people diagnosed with schizophrenia have positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) that do not respond to medication10, 11, and negative symptoms and cognitive impairments associated with more severe psychosis impair people's motivation and social skills. These problems create barriers for social inclusion by impacting on the person's ability to build and sustain relationships and to engage in work, education and other community activities12, 13, 14.

Nevertheless, there is a growing body of consumer‐oriented literature which validates the importance of personal recovery from mental illness, which is not defined by the presence or absence of symptoms but by valued social roles and relationships15, 16. There is, therefore, an obvious need to address the social impact of SMI and thus interrupt its bidirectional, negatively reinforcing relationship with social exclusion. Yet, the evidence base to support investment in social interventions has tended to lag behind that concerning pharmacological and psychological therapies, possibly due to their complex nature and the associated challenges they pose in terms of robust study design. Furthermore, due to their complexity, even when supported by good evidence, social interventions are typically more difficult to implement in practice compared with pharmacological (and even psychological) therapies and require commitment and support from multiple stakeholders across the policy and provider spectrum 17 .

Perhaps a more fundamental issue is the lack of clarity about exactly what is meant by a “social intervention”. For example, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on the prevention and management of psychosis and schizophrenia in adults 18 categorizes family interventions under psychological therapies (along with cognitive behavioral therapy and art therapies) in one section and under “psychosocial interventions” in another, but does not use the terms “psychosocial” or “social” in relation to its section on interventions that enable employment, education and occupational activities.

These difficulties with nomenclature are understandable but problematic. If we consider the example of family interventions, these need to be delivered by well‐trained professionals (often, but not exclusively, clinical psychologists) and draw on underpinning psychological theories, and it seems reasonable, therefore, to consider them as psychological interventions. However, they target the individual's immediate social network and aim to impact positively on social outcomes for both service users and carers (for example, through better family relationships and reducing the emotional strain experienced by family members). The term “psychosocial” addresses this issue, but has tended to be used as a catch‐all for any intervention that is not a medicinal or biomedical one.

This term also often conflates models of care with interventions that more specifically target the individual. For example, intensive case management is a well‐described, manualized and internationally recognized model of community‐based multidisciplinary support provided to people with severe mental health problems who are high users of inpatient care. Its effectiveness in reducing inpatient service use is well established (particularly when implemented in settings that have high levels of provision of inpatient services and less developed community services) 19 . However, it is not a psychological or social intervention in itself, but rather a vehicle for the delivery of pharmacological, psychological and social interventions. Despite this, it is often referred to as a psychosocial intervention. Other models of care (such as supported accommodation and supported employment) appear more obviously “social” both in content and in what they aim to achieve and thus, arguably, have a better fit with the term “social intervention”.

Adding to the complexity, there is an increasing interest in peer‐led or co‐led interventions for people with mental health problems, which, by definition, have a “social” component (the “peer” element) but are not commonly described as “social” interventions, despite an emphasis on promoting choice, control and agency.

An additional problem for researchers is that social outcomes are not always well defined, which impacts on how reliably they can be measured. More objective outcomes, such as employment or stable housing, can be operationalized relatively easily, but concepts such as quality of life tend to be more subjective and thus more difficult to assess, not least because they can be confounded by symptoms of the mental illness itself 20 .

A further issue is context. Whilst the belief that schizophrenia and other SMI has a better social prognosis in non‐industrialized societies is no longer universally accepted 21 , there are major challenges associated with the delivery of effective social interventions to enhance social outcomes in less economically developed settings, including sociocultural factors such as the availability of family support, the impact of industrialization, stigma, discrimination, inadequate protection of human rights, and limited access to services 22 . Furthermore, there are even greater barriers to providing and researching social interventions in low‐ and middle‐income (LAMI) than higher‐income countries, due to the limited availability of human and financial resources.

Given these multiple considerations, we focused this review on interventions that were clearly social in content and aimed to improve social outcomes; specifically, those that aimed to improve social and economic participation for people with SMI. We included studies conducted in LAMI countries as well as those from high‐income countries.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of the recent literature on models of care and interventions for individuals with SMI for the Australian Royal Commission into Victoria's Mental Health System 23 . The present review includes a subset of identified studies that reported on the effectiveness and/or cost‐effectiveness of community‐based models of care and interventions that had the overarching aim of supporting social inclusion.

Search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our search was conducted in July 2020 using Medline, EMBASE, PsycInfo, CINAHL and Cochrane databases, and included peer‐reviewed papers published between January 2016 and July 2020. Our search terms (key words and MeSH terms) reflected three central concepts: “severe mental illness”, “models of care and/or interventions”, and “outcome and experience measurement” (full search string available on request). We limited our search to publications in English and available in full text. Authors were contacted for relevant papers if the full text could not be accessed.

Inclusion criteria for the original search were: a) models of care for adults aged 18 to 65 years with severe and persistent mental illness; b) group or individual interventions that could be delivered alone or through an identified model of care. For example, Individual Placement and Support is a model of care (a form of supported employment), whereas family psychoeducation is an intervention. Additional inclusion criteria for the present review were: c) community‐based models and interventions that aimed to improve social inclusion (i.e., supported accommodation, supported education, supported employment, community participation interventions, family interventions, peer‐supported/developed/led interventions; social skills training interventions); d) studies that evaluated models of care or interventions for people with SMI, defined as a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or other severe and enduring psychotic disorder. Studies reporting on models of care or interventions that also comprised a peer component were included within the relevant category. The separate peer‐led/supported interventions category included studies where the peer component was not delivered as part of one of the other included models of care or interventions.

Exclusion criteria were: a) studies conducted in environments other than the community, for example inpatient units or prisons; b) studies that focused on individuals with a primary diagnosis of personality, depressive or anxiety disorder, substance use disorder, acquired brain injury, intellectual disability, or trauma due to natural disasters or military service; c) studies where fewer than 50% of the sample met our SMI diagnostic inclusion criteria (see above); d) studies that did not report on any relevant social outcomes; e) publications that did not report primary empirical data, such as reviews, editorials and commentaries.

Social outcomes were broadly defined to include any indicator of improved social or economic participation. For example, for studies evaluating supported accommodation, we included those reporting on housing stability or progression to more independent accommodation; for studies of supported employment or supported education, we included those reporting outcomes related to gaining or sustaining employment in a competitive, paid or unpaid post, or engagement in mainstream or supported study or volunteering. Outcomes of interest for studies of family interventions included measures of family functioning such as expressed emotion and carer burden. Whilst not measured at the individual service user level, these are appropriate to the aims of this review since supportive, healthy family relationships are crucial to most people's recovery and social and community participation 24 . In addition, it is well established that high expressed emotion within the family is a risk factor for relapse and is highly correlated with carer burden 25 . Thus, family interventions often aim to reduce one or both of these. For other interventions, outcomes included measures of social skills, social functioning, engagement in community‐based activities, social connection, self‐efficacy, hope and empowerment.

Study selection

Results of the original search undertaken for the Victorian Royal Commission were screened using the Covidence online software (https://www.covidence.org). After duplicates were removed, reviewers screened by title, abstract and full text. All disagreements were resolved through consulting with the project lead.

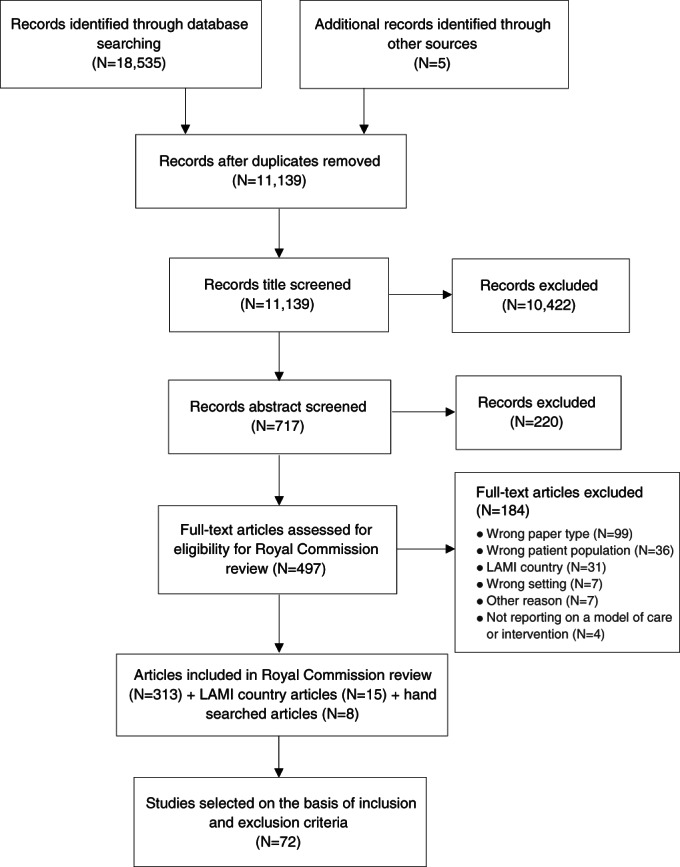

The Royal Commission review identified 313 papers. For the present review, an additional 15 papers reporting on studies conducted in LAMI countries (that were excluded from the Royal Commission review) plus eight hand‐searched papers were included in the pool, giving a total of 336 papers.

Publications were selected from these 336 using Covidence on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. A team of six reviewers screened by title, abstract and full text, with each study requiring two “yes” votes at each stage to be included. All conflicting votes were resolved by an independent third reviewer.

Quality of evidence

Primary papers were evaluated by the Kmet standard criteria to assess methodological quality of both quantitative and qualitative research 26 . Quantitative papers were rated on 14 items and qualitative papers on 10 items, related to the study design, participant selection, data analysis methods, and the clarity and interpretation of results. Each paper was rated by one reviewer and validated through discussion between reviewers at weekly meetings to ensure consistency in rating. Total scores were reported out of 100 (i.e., as percentage equivalents) to take account of non‐applicable items.

We developed a data extraction table and guidance notes to assist consistency in the synthesis of findings from studies in each of the seven models of care/community interventions. One co‐author produced a textual summary for each social intervention category, and each summary was then reviewed by both first authors. The textual summaries were then refined and finalized through consensus discussion within the author group.

Narrative synthesis

Given the range of models of care and interventions included, we chose a narrative synthesis approach to summarize our findings. Narrative synthesis includes: a preliminary synthesis to identify patterns of findings across included studies; exploration of whether effects of an intervention vary according to study population; identification of factors that may influence the results within individual studies and explain difference in findings between studies; development of a theoretical framework underpinning specific intervention effects; assessment of the robustness of the synthesis based on the strength of evidence; discussion of the generalizability of conclusions to wider populations and contexts 27 .

Since our review included multiple social interventions, we did not aim to address the development of a theoretical framework underpinning the effects of each intervention. However, factors that might be relevant to the effectiveness and implementation across our included social interventions were summarized.

RESULTS

We identified 72 studies meeting our eligibility criteria (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. LAMI – low‐ and middle‐income

Over half (41/72) of the included studies reported on the effectiveness of social interventions delivered at the service level (supported accommodation, supported education, supported employment), and the remainder evaluated interventions targeting people with SMI directly (community participation, family interventions, peer‐developed/led/supported interventions, social skills training). A summary of the characteristics and quality ratings of included studies is provided in Tables 1, 2, 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included supported accommodation and supported education studies

| Country | Study design | Study population | Kmet score/100 (quant.) | Kmet score/100 (qual.) | Social outcomes investigated | Key findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Supported accommodation studies | |||||||

|

Aubry et al 28 |

Canada | Non‐blinded RCT comparing HF+ACT with TAU |

Homeless adults with SMI |

92 | Outcomes at 24 months. Primary: housing stability. Secondary: community integration. | HF+ACT group had greater housing stability. No difference between groups in community functioning. | |

|

Bitter at al29 |

The Netherlands | Non‐blinded cluster RCT comparing supported housing staff training in recovery‐based practice with TAU |

Adults with SMI |

92 | Outcomes at 20 months. Primary: social functioning and personal recovery. Secondary: empowerment, hope, self‐efficacy. | No difference between groups in outcomes. | |

|

Brown et al 30 |

US | Pre‐post case‐control study comparing HF+ ACT with TAU | Homeless adults with SMI | 91 | Housing stability over the 12 months before and after intervention or TAU period. | HF+ACT group had greater housing stability. | |

| Gutman et al 31 | UK | Case‐control study comparing supported housing transition program with TAU | Homeless men with SMI | 45 | Primary outcome at 6 months: successful move to supported housing. | Intervention group more likely to have successful move to supported housing. | |

| Holmes et al 32 | Australia | Retrospective non‐controlled pre‐post evaluation of supported housing | Homeless adults with mental health problems | 45 | Housing stability and evictions 2 years before and after moving to the project. | Those with SMI less likely to be evicted than other clients. | |

| Killaspy et al 33 | UK | National survey of supported accommodation services in England | Adults with SMI | 100 |

Cross‐sectional survey. Primary: autonomy and social inclusion. Secondary: costs of care. |

Residential care (RC) and supported housing (SH) had clients with more severe mental illness than floating outreach (FO). Autonomy greatest for SH. SH and FO more socially included than RC. RC most expensive. | |

| Killaspy et al 34 | UK |

Cohort study of participants surveyed in Killaspy et al 33 |

Adults with SMI | 100 | Outcomes at 30 months. Primary: successful move to more independent accommodation. Secondary: costs of care. | 41% moved‐on successfully with associated lower inpatient and community mental health service costs. Move‐on was most likely for FO clients. | |

| Somers et al 35 | Canada | Non‐blinded RCT comparing HF+ACT (scattered housing) vs. HF+ACT (congregate housing) vs. TAU |

Homeless adults with SMI |

92 | Outcomes at 24 months. Primary: housing stability. Secondary: community integration. |

HF+ACT in both scattered and congregate site groups had greater housing stability than TAU. Community integration better than TAU for congregate HF+ACT group. |

|

| Stergiopoulos et al 36 | Canada | Non‐blinded RCT comparing HF+ACT with TAU |

Homeless adults with SMI |

92 | Outcomes at 24 months. Primary: housing stability. Secondary: community integration. |

HF+ACT group had greater housing stability and community integration. |

|

| Macnaughton et al 37 | Canada | Qualitative process evaluation of HF implementation in six regions | HF staff and stakeholders, training and process documents | 92 | Implementation of HF in different contexts. |

Training and support critical for HF staff. Training flexible enough to accommodate different contexts and policy imperatives. |

|

| Padamaker et al 38 | India | Qualitative study of move from long‐term institution to supported housing | Women with SMI and focus group with staff | 40 | Service user and staff experiences of the move. | Gradual improvement in women's functioning and confidence and acceptance by neighbours. | |

| Rhenter et al 39 | France | Qualitative study of participants of RCT comparing HF with TAU | Homeless adults with SMI who received HF | 100 |

Housing and recovery experiences before and after move to HF service. |

Importance of stable housing as “a refuge” that prompts reflection and instils hope. | |

| Roos et al 40 | Norway | Qualitative study of sheltered housing services | Adults with SMI | 90 | Clients’ experiences of the services. | Clients liked having self‐contained apartment plus shared space to socialize and do activities with others. Main issue was time‐limited nature of service. | |

| Stanhope et al 41 | US | Qualitative study of supportive housing projects | Staff of services for homeless adults with SMI | 85 | Case managers’ views on purpose and delivery of the service. |

Staff were overly focused on medication management. |

|

| Stergiopoulos et al 42 | Canada | Qualitative process evaluation of implementation of HF | HF managers, housing providers and case managers | 90 | Facilitators and barriers to implementation of HF. | Facilitators: shared commitment to HF philosophy; shared caseload; monitoring fidelity. Barriers: lack of housing availability; inadequate frequency of client contacts; lack of service user involvement. | |

| Worton et al 43 | Canada | Qualitative process evaluation of implementation of HF in six regions |

HF staff and stakeholders, training and process documents |

92 | Facilitators and barriers to implementation of HF in different contexts. |

Facilitators: stakeholders engaged; resources; local champions; staff trained and supervised, able to adapt model to local context; outcome monitoring. Barriers: lack of structures to align key agencies; staff resistance. |

|

|

Supported education studies | |||||||

| Ebrahim et al 46 | UK |

Non‐controlled, mixed methods pre‐post evaluation of a recovery college |

Recovery college students |

55 | 40 | Outcomes assessed through feedback forms at end of each course: empowerment, well‐being, confidence and free‐text comments. | Students felt more empowered and experienced improved well‐being and confidence. College was enabling, promoted hope and social connection. |

| Hall et al 47 | Australia | Co‐produced, non‐controlled, mixed methods evaluation of a recovery college | Recovery college students, staff, other key stakeholders | 41 | 85 | Experiences of the recovery college | College facilitated learning and growth; was inspiring, encouraging and compassionate; a “stepping‐stone” to mainstream education. |

| Sommer et al 48 | Australia | Non‐controlled pre‐post evaluation of a recovery college | Recovery college students | 91 | Primary outcome: achievement of goals identified in initial learning plan. | 70% of goals achieved at least partially. Most common goals related to education, physical health, social and personal relationships, mental health, and employment. | |

| Sutton et al 49 | UK | Non‐controlled pre‐post evaluation of a recovery college | Recovery college students | 86 | Primary outcome: economic benefits of attending the recovery college. | Attendance associated with higher chance of subsequent employment and increase in personal income. | |

| Wilson et al 50 | UK |

Non‐controlled, mixed methods, pre‐post evaluation of a recovery college |

Recovery college students | 77 | 80 | Primary outcomes at 6 months: well‐being, social inclusion. | Improvement in students’ well‐being and social inclusion, supported by qualitative findings. |

RCT – randomized controlled trial, HF – Housing First, ACT – assertive community treatment, TAU – treatment‐as‐usual, SMI – severe mental illness, quant. – quantitative, qual. – qualitative

Table 2.

Characteristics of included supported employment studies

| Country | Study design | Study population | Kmet score/100 (quant.) | Kmet score/100 (qual.) | Social outcomes investigated | Key findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Christensen et al 51 |

Denmark |

Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing IPS with enhanced IPS (E‐IPS) or TAU |

Adults with SMI seeking employment or education |

100 |

Outcomes at 18 months. Primary outcome: competitive employment or education. |

More of those receiving IPS (59.1%) or E‐IPS (59.9%) achieved competitive employment or education than TAU group (46.5%), but advantage for E‐IPS over IPS. |

|

| Cook et al 52 | US | Multisite controlled trial comparing SE with TAU | Adults with SMI from four US regions | 85 | Social security data on employment over 13 years. | 32.9% of participants were employed at some point. This was almost three times more likely for SE recipients. | |

| De Winter et al 53 | The Netherlands | Non‐controlled longitudinal study of IPS | Clients of 27 IPS programs (23 targeted adults with SMI) | 77 | IPS fidelity and employment assessed quarterly over five years. | Greatest improvement in employment outcomes seen after 18 months of IPS. Positive association between IPS fidelity and employment. | |

| Glynn et al 54 | US | Non‐blinded RCT comparing IPS with IPS + work skills training | Adults with SMI | 100 | Primary outcomes at 2 years: employment and job tenure. | 63% of all participants gained employment. No differences between groups. | |

| Kern et al 55 | US | Pooled results from two RCTs comparing IPS with IPS + errorless learning |

Adults with SMI |

77 | Primary outcomes at 12 months: achievement of employment and job tenure. | 32% of all participants obtained jobs (mostly minimum wage and part‐time). The IPS + errorless learning group had greater job tenure. | |

| Lystad et al 56 | Norway | Multi‐site non‐blinded RCT comparing VR+CR with VR+CBT |

Adults with SMI |

62 | Primary outcome at 2 years: employment, hours worked. |

Employment and hours worked increased in both groups. No difference between groups in outcomes. |

|

| McGurk et al 57 | US | Non‐blinded RCT comparing enhanced VR (E‐VR) with E‐VR+CR | Adults with SMI for whom previous VR was ineffective | 85 | Outcomes at 3 years. Primary: employment rate. Secondary: engagement in work related activity. | No differences in employment rate between groups, but E‐VR+CR group more likely to engage in work‐related activity. | |

| McGurk et al 58 | US | Pre‐post feasibility study of VR+CR |

Adults with SMI |

64 | Feasibility (uptake and completion). | Intervention feasible (79% of participants completed at least 6/24 sessions). | |

| Puig et al 59 | US | Sub‐analysis of one arm of RCT comparing IPS with and without cognitive training | Adults with SMI receiving the cognitive training intervention | 82 | Outcomes at 2 years: cognitive skills and competitive employment. | Improved attention and age (younger and older participants) were associated with achieving competitive employment. | |

| Reme et al 60 | Norway | Multicentre non‐blinded RCT comparing IPS with TAU | Adults with severe and moderate mental illness | 85 | Outcomes at 12 and 18 months. Primary: competitive employment. | IPS group more likely to be in competitive employment. Similar employment rates for people with severe and moderate mental illness. | |

| Rodriguez Pulido et al 61 | Spain | Non‐blinded RCT comparing IPS with IPS+CR | Adults with SMI | 100 | Outcomes at 2 years. Primary: employment and hours worked/week. |

IPS +CR group more likely to gain employment and worked more hours. |

|

| Scanlan et al 62 | Australia | Non‐controlled prospective study of recovery‐based IPS service | Adults with SMI | 83 | Outcomes at 2 years: competitive or voluntary employment, job tenure, education engagement. | 49.5% gained competitive employment, mean duration 151 days. 63.9% gained employment or engaged in education or voluntary work. | |

| Schneider et al 63 | UK | Feasibility RCT comparing IPS + work‐focused CBT with IPS alone |

Adults with SMI |

81 | Outcomes at 6 months. Primary: hours in competitive employment. Secondary: participation in education, training or volunteering. | 34% participants gained employment. No differences between groups in outcomes. | |

| Twamley et al 64 | US | Non‐blinded RCT comparing IPS + cognitive training with E‐IPS |

Adults with SMI |

96 | Outcomes at 2 years. Primary: number of weeks worked. Secondary: job attainment, hours worked, wages earned. | No difference between groups in outcomes. | |

| Zhang et al 65 | China | Non‐blinded RCT comparing IPS with VR or IPS + work‐related social skills training (E‐IPS) |

Adults with SMI |

88 |

Outcomes at 2 years. Primary: job attainment Secondary: job tenure, hours per week worked. |

Higher job attainment and longer job tenure in the E‐IPS group than IPS alone. IPS and E‐IPS both had better employment outcomes than VR. | |

| Hutchinson et al 66 | UK |

Mixed methods evaluation of IPS implementation in six regions |

Community mental health services for adults with SMI | 50 | 35 |

Outcomes at 18 months. Primary: competitive employment. Qualitative: factors influencing implementation. |

5 of the 6 sites achieved target of supporting 60 clients into competitive employment. Service resource pressures, stakeholder support and achievement of targets influenced programme sustainability. |

| Gammelgaard et al 67 | Denmark | Phenomenological study of IPS | Adults with SMI participating in RCT evaluating IPS | 80 | How IPS and employment might influence recovery, through a “reflective lifeworld approach”. | Employment specialists adopted recovery‐based practice. Employment boosted self‐esteem, skills, routines and financial security. | |

| Perrez‐Corrales et al 68 | Spain | Phenomenological study of volunteering programs | Adults with SMI working in volunteer roles | 100 | Experiences of volunteering and its impact on the recovery process. | Volunteering enabled people to build a valued identity; having responsibility through volunteering helped people feel they had a “normal” life. | |

| Talbot et al 69 | UK | Descriptive qualitative study of IPS in forensic mental health setting | Adults with SMI under community forensic services | 60 | Implementation of IPS in community forensic mental health service. | Implementation required robust collaboration with internal and external agencies. Barriers: negative staff attitudes and difficulty engaging employers. Facilitators: support of service managers and outside groups. | |

| Yu et al 70 | China | Qualitative process evaluation of E‐IPS recipients in RCT reported above 65 | Adults with SMI who received E‐IPS and gained employment plus their family members | 55 | Participant and family views of the E‐IPS intervention. | Participants reported benefits from work‐related social skills training and valued social connections made at work. Participants valued having choice about jobs whereas carers valued financial benefits more than job fit. |

RCT – randomized controlled trial, IPS – Individual Placement and Support, SE – supported employment, CBT – cognitive behavioral therapy, TAU – treatment‐as‐usual, SMI – severe mental illness, VR – vocational rehabilitation, CR – cognitive remediation, quant. – quantitative, qual. – qualitative

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies on social interventions delivered at the group or individual client level

| Country | Study design | Study population | Kmet score/100 (quant.) | Kmet score/100 (qual.) | Social outcomes investigated | Key findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Community participation studies | |||||||

|

Chen et al 75 |

China | Non‐blinded RCT comparing Clubhouse model with standard care | Adults with SMI | 75 |

Outcomes at 6 months. Primary: social functioning and self‐determination. |

Clubhouse group had greater improvement in social functioning and self‐determination. | |

| Heatherington et al 76 | US | Non‐controlled pre‐post study evaluating a residential farm program | Adults with SMI | 86 | Outcomes at 6 and 36 months: clinical and personal recovery; community participation. | Improved community participation at 36 months. | |

| Varga et al 77 | Hungary | Non‐blinded RCT comparing community social club with case management or TAU | Adults with SMI | 92 | Outcomes at 6 months: social functioning and social cognition. |

Community social club and case management groups had better social function than TAU. Community social club group also had better social cognition. |

|

| Moxham et al 78 | Australia | Qualitative evaluation of Recovery Camp | Adults with SMI | 85 | Participants’ personal goals and whether met during the camp. | Goals: connectedness; developing healthy habits; challenging myself; personal recovery. Most goals reported as met. | |

| Prince et al 79 | US | Qualitative exploration of Clubhouse model | Clubhouse members (adults with SMI) | 85 | Exploration of benefits of Clubhouse membership and most helpful features. |

Benefits: improved social skills, gaining confidence, social connection. Features: flexible, non‐judgmental culture; equality of members and staff; evening and weekend activities; skills acquisition; sharing experiences; outreach support. |

|

|

Rouse et al 80 |

Canada | Participatory qualitative evaluation of Clubhouse model | Clubhouse members (adults with SMI) and staff | 95 | Explored how Clubhouse structures and ethos facilitated members’ recovery. | Structures/ethos: mutual respect, promoting self‐efficacy and autonomy, opportunities for social connection, providing purpose. Recovery: building identity and self‐respect, acquiring skills, being part of an empowered community. | |

| Saavedra et al 81 | UK | Qualitative evaluation of creative workshops in local art gallery | Adults with SMI, mental health staff, and workshop facilitator | 95 | Exploration of impact of workshop participation. | Main benefits: learning about artistic process; social connection; greater psychological well‐being; challenging institutional attitudes; breaking down barriers between service users and staff. | |

| Whitley et al 82 | Canada | Qualitative evaluation of a participatory video project | Adults with SMI | 80 | Exploration of participants’ experiences of the project. | Project well received. Main benefits: skill acquisition; connectedness; meaningful focus; empowerment; personal growth. | |

| Smidl et al 83 | US | Non‐controlled, mixed methods pre‐post evaluation of a therapeutic gardening project |

Adults with SMI and staff |

45 | 60 |

Outcomes at 3 months: motivation, social skills. Qualitative data from participants’ journals. |

Motivation ratings improved. Most participants and staff felt the project helped with social connection and skills. Qualitative: the project gave people a sense of purpose and pride. |

|

Family intervention studies | |||||||

| Kumar et al 84 | India | Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing a brief psychoeducation programme with nonspecific control intervention | Key relatives of adults with SMI | 69 | Outcomes at completion of sessions. Primary: carer burden. | Intervention group experienced greater reduction in carer burden. | |

| Martin‐Carrasco et al 85 | Spain and Portugal | Multicentre, assessor‐blinded RCT comparing psychoeducation intervention programme with TAU |

Primary family caregivers of adults with SMI |

96 | Outcomes at end of intervention (4 months) and 4 months later. Primary: subjective and objective carer burden. | Intervention group experienced reduced subjective carer burden at both follow‐ups. No difference between groups in objective carer burden. | |

| Mirsepassi et al 86 | Iran | Implementation study of a psychoeducation service | Adults with SMI and their family members | 60 | Programme development, implementation and sustainability. | Implementation affected by: low referral rate; limited resources; poor literacy; excessive distance to travel to access service. | |

| Perlick et al 87 | US | Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing carer‐only adaptation of family focused therapy with standard health education | Relatives of adults with SMI | 88 | Outcomes at end of intervention and 6 months later. Primary: carer burden. | Intervention group experienced greater improvement in carer burden at both follow‐ups. | |

| Al‐HadiHasan et al 88 | Jordan | Qualitative process evaluation, nested within an RCT | Adults with SMI and their primary caregivers who received the family intervention | 85 | Impact of family psychoeducation intervention on recipients. | Carers reported improved health, well‐being and coping. Service users reported better motivation. Both groups experienced improved self‐confidence and social interaction. | |

| Edge et al 89 | UK | Mixed methods, feasibility cohort study | African‐Caribbean adults with SMI, their relatives or “proxy” family | 65 | 65 | Feasibility of delivering a culturally appropriate family intervention to “proxy families” (peer supporters or volunteers if no family). |

Intervention highly acceptable. Most service users reported improved family relationships. Relatives’ communication with service users and health professionals improved. |

| Higgins et al 90 | Ireland | Sequential mixed methods, single group, pre‐post pilot evaluation of EOLAS programmes |

Adults with SMI and their family members |

45 | 55 | All outcomes at programme completion. Service users and families: hope for the future and self‐advocacy. Family members: perceptions of available social support. | No significant changes in quantitative outcomes. Qualitative: most participants found hearing other members’ stories was helpful. Co‐facilitation by peer support workers viewed positively, but some clinician facilitators appeared to lack skills to enable peer support worker co‐facilitators to participate equally. |

| Higgins et al 91 | Ireland | Sequential mixed methods, single group, pre‐post evaluation of EOLAS programmes |

Relatives of adults with SMI |

59 | 50 | All outcomes at programme completion: confidence in ability to cope and to access help for relative; self‐advocacy; hope for the future. | Participants experienced increased confidence and hope and were satisfied/very satisfied with the program. Qualitative: increased awareness of communication within the family; value of peer support. |

| Lobban et al 92 and Lobban et al 93 | UK | Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing online psychoeducation + resource directory (RD) with RD alone; mixed methods evaluation and economic analysis |

Relatives and close friends of adults with SMI. Qualitative sample: intervention group only |

100 100 |

65 50 |

Outcomes at 12 and 24 weeks. Primary: carer well‐being and experience of support. Secondary: costs of intervention and health and social care; experiences of the intervention. | No differences between groups in carer well‐being and support. Intervention cost more than RD alone and delivered no better health outcomes. Qualitative: intervention positively received. Proactive support from the peer supporters particularly appreciated. |

| Nguyen et al 94 | Vietnam | Non‐controlled, mixed methods, pre‐post evaluation of family intervention and cost analysis | Adults with SMI and their caregivers | 68 | 45 |

Outcomes at 1 year. Quantitative: service user functioning. Qualitative: intervention acceptability and feasibility. Cost analysis: service user and family income. |

High participation (98%) and acceptability. Service user functioning improved, and one quarter secured a paid job. Financial burden on family decreased. |

|

Peer‐led/supported intervention studies | |||||||

| Agrest et al 95 | Chile | Qualitative evaluation of peer supported intervention promoting recovery | Adults with SMI | 80 | Feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. | Peer support workers well received and helped engagement with community resources. | |

| Beavan et al 96 | Australia | Self‐report survey of Hearing Voices Network |

Adults with SMI who attended network meetings |

85 | 75 |

Cross‐sectional data only. Descriptive and free‐text responses. |

Positive benefits included reduced isolation, gaining social skills and improved self‐esteem. |

|

Easter et al 97 |

US | Non‐blinded RCT comparing facilitation of advance directive by a peer‐support worker or a clinician | Adults with SMI under the care of an ACT team | 69 |

Outcomes at 6 weeks. Primary: empowerment. Secondary: self‐esteem. |

Modest advantage of using peer support workers in terms of empowerment and attitudes toward treatment. | |

| Mahlke et al 98 | Germany | Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing peer support + TAU with TAU alone |

Adults with SMI |

96 |

Outcomes at 6 months. Primary: self‐efficacy. |

Self‐efficacy greater for intervention group. | |

| O'Connell et al 99 | US | Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing peer mentor + TAU with TAU alone | Adult inpatients with SMI, substance misuse and recurrent admissions | 85 |

Outcomes at 9 months. Secondary: social function and sense of community. |

Greater improvement in social function for intervention group. | |

|

Salzer et al 100 |

US | Non‐blinded RCT and qualitative evaluation of addition of peer support workers to community mental health services |

Adults with SMI |

69 | 60 |

Outcomes at 12 months: community participation, empowerment, therapeutic alliance. Qualitative: content of peer support. |

Peer support group had greater community participation days. |

| Thomas et al 101 | US |

Sub‐analysis of intervention arm of RCT comparing peer support with TAU |

Adults with SMI receiving the peer support intervention | 89 | Outcomes at 6 and 12 months: therapeutic alliance, empowerment and satisfaction. | Therapeutic alliance between participants and peer workers was high and positively associated with empowerment and satisfaction. | |

|

Social skills intervention studies | |||||||

| Favrod et al 102 | France | Non‐controlled pre‐post evaluation of Positive Emotions Program for Schizophrenia | Adults with schizophrenia and severe negative symptoms | 86 | Follow‐up assessment point not specified. Primary: social function. |

Social function improved. |

|

| Hasson‐Ohayon et al 103 | Israel | Non‐blinded RCT comparing social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) vs. therapeutic alliance focused therapy (TAFT) vs. TAU | Adults with SMI under a psychiatric rehabilitation service | 75 | Outcomes at end of 6 month intervention and 3 months later. Primary: social function. | No difference between groups in social functioning. | |

| Horan et al 104 | US |

Non‐blinded RCT comparing social cognitive skills training (SCST) delivered in vivo with SCST delivered in clinic or active control intervention |

Adults with SMI | 93 | Outcomes at 3 months. Primary: social cognition. Secondary: social functioning. |

SSCT groups both improved in social cognition. No between‐group differences in social functioning. |

|

| Kayo et al 105 | Brazil | Assessor‐blinded RCT comparing social skills training with an active control intervention | Adults with treatment resistant schizophrenia receiving clozapine | 93 | Outcomes at 20 weeks and 6 months. Primary: negative symptoms. Secondary: social skills. | No between‐group differences in social skills or negative symptoms. | |

RCT – randomized controlled trial, TAU – treatment‐as‐usual, SMI – severe mental illness, quant. – quantitative, qual. – qualitative

Social interventions delivered at the service level

Supported accommodation (see Table 1)

There were 16 eligible studies in this domain, nine of which were quantitative28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 and seven qualitative37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43. The studies were conducted in eight different countries: six in Canada28, 35, 36, 37, 42, 43, three in the UK31, 33, 34, two in the US30, 41, and one each in Australia 32 , France 39 , India 38 , the Netherlands 29 and Norway 40 .

The quantitative studies comprised four randomized controlled trials (RCTs)28, 29, 35, 36, two case‐control studies30, 31, one pre‐post uncontrolled study 32 , one national survey 33 , and one national naturalistic prospective cohort study 34 .

The mean Kmet quality assessment score for quantitative papers was 83 (out of 100) and ranged from 10033,34 to 4531, 32. The mean quality assessment score for the qualitative papers was 85 and ranged from 10039 to 40 38 .

Housing First

Five of the quantitative studies and four of the qualitative studies (53% of all the supported accommodation studies) evaluated the Housing First (HF) model. This approach evolved in the US and Canada to address the high rate of homelessness amongst people with SMI, many of whom also have comorbid substance misuse problems. It involves the provision of rent supplements and support from a clinical team assisting persons to find, move into and sustain a tenancy, and helping them address their mental health issues using a recovery‐oriented framework 44 .

A robust, five centre RCT in Canada (“Chez Soi”) found HF to be associated with greater housing stability compared with treatment‐as‐usual (TAU) at 2‐year follow‐up (74% of HF clients were in stable housing compared to only 41% of those receiving standard care) 45 , but no differences were found between the groups in community functioning or secondary clinical and social outcomes. Our review included five high‐quality studies, two quantitative28, 36 and three qualitative37, 42, 43, associated with the Chez‐Soi trial.

A high‐quality (Kmet 91) case‐control study 30 in Seattle, US reported better housing outcomes for those receiving HF, with a lower percentage homeless and fewer days of homelessness at 12‐month follow‐up compared to standard care. A non‐blinded RCT versus TAU (Kmet 92) 28 reported findings from Moncton, Canada, where the clinical input to HF tenants was provided through assertive community treatment (ACT). Housing outcomes were better for HF recipients than those in the standard care group, with large effect sizes, but there was no difference between groups in community functioning or clinical outcomes.

A sub‐analysis of data from the Chez‐Soi trial's Toronto site 36 (Kmet 92), which provided HF plus intensive case management, adapted to the city's ethnically diverse population, reported that housing stability and community functioning were greater for those who received HF compared to controls. Similar positive results were obtained in a three‐arm RCT conducted in Vancouver 35 (Kmet 92) that compared HF provided to people with SMI (mainly psychosis and co‐occurring substance misuse problems) in scattered tenancies without on‐site staff, versus support provided in 24‐hour staffed congregate housing, and versus standard care. Both forms of supported accommodation (HF and on‐site staffing) were associated with greater housing stability than standard care, but clients in the congregate staffed housing rated their sense of community integration and personal recovery higher than the other two groups.

Using data from preparatory meetings, training events, supervision and focus groups with key stakeholders at HF implementation sites in the Chez‐Soi trial, two qualitative studies37, 43 (both with Kmet scores of 92) investigated the barriers and facilitators to successful implementation of the HF model.

Facilitators included: a) site readiness (i.e., ensuring that local stakeholder organizational policies were aligned to support implementation; that ring‐fenced and adequate resources were available; and that local champions were in place); b) organizing stakeholder sessions to frame the problem (homelessness) in a way that was congruent with different organizations’ values and allowed them to collaborate to address it; c) ensuring that all key players were included and engaged in the process; d) ensuring that housing providers and clinicians were trained and supervised to deliver the key elements of the HF model; e) identifying and addressing obstacles to local implementation (e.g., providing rent subsidies to use private tenancies to address shortages in housing supplies); f) providing forums for staff to share and solve implementation problems, build knowledge and avoid burnout; g) allowing flexibility in the model to fit with local context; h) using data to highlight successful outcomes and expand the programme.

Barriers to implementation included: a) lack of consensus about target client group; b) seeing homelessness as a housing problem rather than a wider health and societal problem; c) lack of consensus on how to organize the various structures of the HF approach; d) staff resistance to change and the (false) belief that they were already delivering HF; e) lack of existing structures to bring agencies together; f) financial disincentives (e.g., organizations competing for the same funds); g) housing stability being seen as an end in itself rather than a vehicle to support clients' ongoing recovery; h) lack of training and supervision to ensure that staff adopted a recovery‐oriented approach.

A qualitative evaluation of the implementation of HF at the Chez‐Soi Toronto site 42 was also conducted through interviews with HF senior managers, housing providers and case managers (Kmet 90). Model fidelity assessments were used to identify services with lower fidelity for further exploration of the barriers to implementation. Three main obstacles were identified: lack of housing availability; inadequate frequency of client contacts (the target was weekly contact, but this proved challenging due to staff time constraints and clients declining visits); and a lack of service user involvement in the HF programme. Facilitators to implementation included: a shared commitment to the HF philosophy across providers, senior managers and case managers; and using a shared team caseload approach to provide staff with peer support. The authors concluded that monitoring model fidelity was helpful to identify and then address implementation challenges.

A further robust (Kmet 100) qualitative study of clients of HF services conducted in France 39 reported benefits that went beyond the concrete outcome of housing stability reported in the quantitative studies. These included the deep sense of security that came from having a permanent home and how this provided a base to access adequate resources, build a routine, reclaim a previous identity or build a new one. However, the findings also highlighted the scale of the challenge for individuals in doing so. The authors noted that, whilst the effects of HF are considerable, they are often insufficient to break negative cycles and may only be able to “cushion” downward trajectories. They also observed that housing stability should not be considered a success in and of itself, but rather a basis for ongoing recovery.

Other models of supported accommodation

A national survey of mental health supported accommodation services in England 33 and a subsequent naturalistic cohort study 34 (both with a Kmet score of 100) identified three main types of service: a) residential care homes that provided congregate facilities, staffed 24 hours, where day‐to‐day needs were addressed (e.g. meals, supervision of medication and cleaning) and places were not time limited; b) supported housing that comprised shared or individual self‐contained, time‐limited tenancies with staff based on‐site up to 24 hours a day to assist individuals to gain skills to move on to less supported accommodation; and c) floating outreach services that provided visiting support for a few hours a week to people living in time‐unlimited, self‐contained, individual tenancies, with the aim of reducing support over time.

Quality of care was best in supported housing, and floating outreach was the cheapest of the three service types, but client characteristics differed significantly. Although two‐thirds of participants had some form of psychosis, those in residential care and supported housing had more severe mental health problems than those receiving floating outreach. However, across all services, 57% had a history of severe self‐neglect and 37% were considered vulnerable to exploitation.

After adjusting for differences in clinical characteristics, supported housing clients had greater autonomy than those of the other two service types. Clients of supported housing and floating outreach services were more socially included than those in residential care, but experienced more crime.

At 30‐month follow‐up, 41% of participants had successfully moved on to more independent accommodation (or, for those receiving floating outreach, were managing with fewer hours of support). After adjustment for clinical characteristics, this was most likely for floating outreach clients compared to clients of the other two service types, and more likely for those in supported housing than those in residential care.

Adjusted multilevel models revealed that clients who progressed to more independence had significantly lower community and inpatient mental health service costs than those who did not. Two aspects of service quality were associated with successful progression to more independence: promotion of human rights and recovery‐based practice. Those with more unmet needs, those with higher ratings of vulnerability to self‐neglect or exploitation, and those who had been living at the supported accommodation service longer were less likely to move on. The authors concluded that there were pros and cons of the various models and that different service types tailored to individual need were required, rather than investing only in the cheapest type (i.e., floating outreach).

Group and individual qualitative interviews were carried out with residents of a sheltered housing project in Trondheim, Norway 40 (Kmet 90), that provided self‐contained bedsits, with some communal areas for socializing, and staff on site 24 hours a day. Residents felt that this model provided them with a good balance of independence and support. They liked not having to share facilities with others, felt safe having staff on site, and reported being supported to gain confidence with daily living skills and social activities. The only drawback was the time‐limited nature of the project (residents were expected to move on after a few years).

A six‐week group programme comprising twice weekly sessions with an occupational therapist to prepare people to move to a floating outreach service was evaluated through a small (Kmet 45) case‐control study 31 . More of those who attended the group sustained their supported housing at six‐month follow‐up, suggesting that structured preparatory work for housing transition may be beneficial, but the methodological problems with this study limit the strength of its findings.

Whilst a number of studies identified the importance of supported accommodation services providing a recovery‐oriented approach34, 37, 43, this may prove difficult to implement. A cluster RCT 29 (Kmet 92) in the Netherlands evaluated a recovery‐based practice training intervention for staff of supported accommodation services. The intervention encompassed the use of a collaborative and strengths‐based approach to support service users to identify and work towards individualized goals, but no differences were found between intervention sites and standard services on the primary outcomes of personal recovery, quality of life or social functioning.

Nevertheless, a small qualitative study in Chennai, India 38 (Kmet 40), exploring the experiences of women who moved from a longer‐term mental health institution to a staffed group home, highlights the importance of supported accommodation to people's recovery. The move allowed the women to begin to develop an individual identity and to gain a sense of belonging in the local community for the first time.

Supported education (see Table 1)

Five papers evaluating supported education were identified46, 47, 48, 49, 50, all of which focused on recovery colleges: a recovery‐based mental health education program that uses peer learning advisors to facilitate individual student learning plans 48 and where students are people with lived experience of mental health problems. Two of the studies were quantitative48, 49 and three employed mixed methods46, 47, 50. Three were conducted in the UK46, 49, 50 and two in Australia47, 48.

Although a number of studies reported that attendance at a recovery college inspired students to consider looking for work, only one – a self‐report survey of a college in the UK49 (Kmet 86) – reported data to show a significant positive association between attendance and being in paid or self‐employment at nine‐month follow‐up.

A recovery college in Australia, where students were supported to develop learning plans and identify up to three specific goals, which were reviewed at least annually, was evaluated using routinely collected data on 64 students 48 (Kmet 91). The most commonly cited goals were education, physical health, social and personal relationships, mental health, and employment.

Student engagement in the college courses (including the number of courses enrolled in and the number of classes attended) was found to be associated with goal attainment, but active involvement in the college for over 685 days was negatively associated with goal attainment. The authors concluded that this could be due to a higher severity of mental health needs amongst longer‐term students and a possible need for additional support. The main factors that were reported to impede goal attainment included physical health problems, external stressors/life events, and dependency on others to access the college.

Simpler goals with a relatively short‐time frame appeared easier to achieve than more complex or longer‐term ones. Employment goals were less likely to be achieved than other types of goals, whereas education related goals were the most likely, followed by mental health, social, and physical health goals.

Mixed methods evaluations of recovery colleges of varying quality conducted in the UK46, 50 and Australia 47 have shown consistently positive findings in terms of student satisfaction, improvements in mental well‐being, confidence and reduced social isolation. Many students reported that they were planning to attend mainstream courses, volunteer or gain paid employment in the future46, 50, and some described the college as a “stepping‐stone” to mainstream education 47 . Some colleges provided employment opportunities themselves by involving students in the formulation and facilitation of courses on a paid or voluntary basis, and some signposted students to peer‐support positions elsewhere 47 .

Supported employment (see Table 2)

We identified 20 studies that addressed interventions targeting employment or voluntary work, of which 15 were quantitative51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, one used mixed methods 66 and four were qualitative67, 68, 69, 70.

The mean Kmet quality assessment score for quantitative papers was 82 and ranged from 10051,54,61 to 50 (quantitative component of a mixed methods study) 66 . The mean quality assessment score for the qualitative papers was 66 and ranged from 10068 to 3566 (qualitative component of a mixed methods study).

Seven studies were conducted in the US52, 54, 55, 57, 58, 59, 64, three in the UK63, 66, 69, two each in China65, 70, Denmark51, 67, Norway56, 60 and Spain61, 68, and one each in Australia 62 and the Netherlands 53 .

The interventions studied could be grouped into three main types: Individual Placement and Support (IPS), characterized by rapid individualized job searching for competitive employment, integrated with mental health support, welfare benefits counselling, and on‐the‐job support 71 ; other forms of competitive or sheltered employment with employment specialists providing on‐the‐job support; and vocational rehabilitation, that typically focused on pre‐vocational training, interview and preparation of a curriculum vitae.

Two high‐quality studies (Kmet 10051 and Kmet 85 60 ) compared IPS with usual care, both reporting more favourable employment outcomes achieved through IPS, supporting the international evidence that IPS delivers improved employment outcomes compared to traditional vocational rehabilitation 72 .

A further study 53 (Kmet 77) investigated the longitudinal association between IPS fidelity and employment outcomes among 27 IPS programmes that reported outcomes quarterly to a central registry in the Netherlands. A positive association was found between improvement in IPS fidelity and employment rates over time, with employment outcomes showing the greatest improvement after 18 months of implementation.

Based on emerging evidence that enhanced cognitive functioning could further improve the outcomes achieved from supported employment 73 , eight studies investigated the effectiveness of enhancements to supported employment interventions. Six of these supplemented IPS51, 54, 61, 63, 64, 65, and two supplemented another form of supported employment56, 57. Enhancements included: cognitive remediation computer‐assisted training via CogPack 61 ; manualized compensatory cognitive training 64 ; cognitive remediation (CIRCUITS computer software) in combination with social skills (Thinking Skills for Work) 51 ; computer‐assisted cognitive remediation (CogPack) plus Thinking Skills for Work56, 57, generic work skills training (Workplace Fundamentals) 54 ; work‐related social skills training (10 sessions of behavioral rehearsal plus in vivo problem solving) 65 ; and work‐focused cognitive behavioral therapy (3‐6 sessions matched to need) 63 .

The supplemental interventions were offered at varying levels of intensity, ranging from three to 30 sessions. However, not all studies described in detail the degree of participant engagement, and those which did suggest less than optimal engagement. Twamley et al 64 (Kmet 96) reported a mean of 8.23±4.88 weekly sessions of cognitive training attended in the first 12 weeks of IPS. Christensen et al 51 (Kmet 100) described the enhanced IPS intervention as comprising 30 sessions of cognitive remediation, but 24% of participants did not attend any sessions and the mean attendance was fewer than 10 sessions. In Glynn et al's RCT 54 (Kmet 100), comparing IPS versus IPS plus work skills training, 22% of participants attended none of the work skills classes (an “as‐treated” analysis that removed those participants did not reveal any additional benefits from the supplemental intervention).

While some neurocognitive improvement was described in most of the studies that augmented IPS with a cognitive intervention, only two61, 65 demonstrated significant between‐group findings on employment outcomes. In a Spanish study 61 (Kmet 100), participants in the IPS plus cognitive remediation group achieved significantly greater employment rates and hours worked than those receiving IPS alone. Although well conducted, this was quite a small study, and findings should be interpreted with some caution. In a study carried out in China, Zhang et al 65 (Kmet 88) found that the group receiving IPS plus work‐related social skills training had significantly higher employment rates (63%) than a standard IPS group (50%) and a vocational rehabilitation group who engaged in sheltered work (33%). They suggested that the success of the enhanced IPS intervention might be associated with cultural factors (such as the importance that Chinese employers place on social competence) and concluded that the augmented IPS intervention was a good cultural fit for the Chinese context.

Two studies supplemented supported employment (not IPS) with enhancements that included cognitive remediation56, 57. McGurk et al 57 (Kmet 85) focused their intervention on people who had not previously benefited from vocational services. They randomized participants to either enhanced vocational rehabilitation alone (where participants were supported to identify and address specific cognitive difficulties relevant to the workplace) or enhanced vocational rehabilitation plus computer‐based cognitive remediation (24 sessions) and work‐related coaching (Thinking Skills for Work). There were no between‐group differences on employment outcomes, although the authors noted between‐group differences in education levels at baseline that may have influenced the results.

In Norway, Lystad et al 56 (Kmet 62) investigated the JUMP vocational rehabilitation programme, where participants were offered 10 months of intensive vocational support in sheltered or competitive work environments in addition to either cognitive remediation (40 hours of computer‐based training and coaching, similar to the Thinking Skills for Work intervention), or 40 hours of work‐related cognitive behavioral therapy. Both groups improved in cognitive skills, but no between‐group differences were found in employment outcomes.

Kern et al 55 (Kmet 77) examined how job tenure and work behaviors were impacted by errorless learning (structured training where work behaviors that were causing challenges were broken into elements and addressed hierarchically using cues, prompts, modelling and self‐instruction until high levels of performance were achieved). Data from two studies were combined in the reported paper: a study of 74 veterans with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and a study of 106 participants living in the community with a diagnosis of SMI and memory impairment. Participants all received IPS and were randomized at the point of obtaining a job to either continue IPS alone or to receive IPS plus errorless learning. In total, 58 (32%) participants obtained jobs that were mostly minimum wage and part‐time, and the errorless learning group had significantly better job tenure (41% were still working at the end of 12‐month follow‐up compared to 14% of the IPS alone group). There were no differences in hours worked or wages earned.

Overall, of the eight studies that evaluated supplementing IPS or another form of supported employment, only two found that the augmented approach improved employment outcomes61, 65, despite most of the interventions being associated with improved neurocognitive performance. In addition, Kern et al 55 ’s errorless learning enhancement, predominantly targeting social skills in the workplace, demonstrated enhanced job tenure. Furthermore, a subsequent analysis of participants in the trial conducted by Twamley et al 64 who received IPS and compensatory cognitive training, found that those who were younger or older benefited more in comparison with middle‐aged participants, and that improving attention significantly predicted work attainment 59 (Kmet 82).

Employment outcomes in the included studies were assessed over different periods, up to two years, with the most effective intervention reporting 63% employed and most studies reporting around 50%. These data demonstrate that targeted interventions can be effective in helping a large proportion of people with SMI achieve employment. However, the definition of employment varied and could involve as little as one hour per week in a low wage job over a short period of time.

One study took a longer view, using social security data to understand the impact of engagement in a supported employment programme in the US over many years 52 (Kmet 85). The supported employment programme was not IPS, but comprised employment specialists embedded within multidisciplinary teams coordinating clinical and employment supports and aiming to place people in competitive jobs matched to their preferences. Data on 449 individuals over 13 years showed that a third earned some income and 13% achieved economic self‐sufficiency at least some of the time. Compared to the control group receiving usual care, participants in this study were almost three times more likely to gain employment.

Several studies provided insights into implementation issues. The difficulties of addressing negative staff and employer attitudes, and ensuring that supplemental interventions are delivered by adequately skilled trainers, the contextual challenges of the local labour market and welfare systems, and organizational factors – including the separation of employment and mental health services – have been previously identified 72 and were again highlighted in the included studies.

A mixed methods study of a UK demonstration project to embed IPS into six health service sites 66 (quantitative Kmet 50, qualitative Kmet 35) used various strategies to address barriers to implementation (operational and strategic management, data monitoring, alignment of reporting, use of champions, and learning communities), and many participants gained employment. However, funding was not sustained at several sites, in the context of cost pressures in the health system, highlighting how external factors can undermine implementation efforts. A qualitative evaluation of the implementation of IPS in a forensic context (Kmet 60) 69 identified additional barriers for this client group, such as stigma and restrictions on employment relating to participants’ criminal history.

McGurk et al 58 demonstrated that it was feasible for front‐line staff to engage clients with more complex SMI in their Thinking Skills for Work intervention, prior to referring them to mainstream employment support (Kmet 64). The intervention was tailored to each site, with staff trained via two workshops focused on understanding the cognitive challenges of people with SMI and supporting clients to use a computerized cognitive training software programme. Sites with easier access to mainstream employment support had better employment outcomes, and the authors highlighted the relevance of local contextual factors to the successful implementation of supported employment interventions.

An Australian study 62 (Kmet 83) provided detail on how job coaches used the theory and practice guidance of the Collaborative Recovery Model 74 to underpin their implementation of IPS, including how they engaged with people, instilled hope and built on individuals’ strengths and values. The authors concluded that a recovery‐based approach appeared to enhance the structured activities of high‐fidelity IPS, but the findings warrant further investigation under controlled conditions.

Qualitative studies also provided additional insights into the need to consider cultural factors, personal experiences and family perspectives in implementation. A phenomenological investigation of 12 participants receiving IPS explored how the intervention influenced recovery for people with SMI 67 (Kmet 80). Some participants described the importance of the relationships that they established with employment specialists leading to increased self‐esteem and changes to life patterns, while others identified employment itself as most influential in their recovery. They highlighted how the individualized approach of IPS made them more hopeful about employment, especially in comparison with previous experiences with mainstream employment centres.

The experiences of 15 people with schizophrenia who received the IPS enhanced with social skills training intervention in the study conducted in China described earlier 65 were explored qualitatively 70 (Kmet 55). The findings highlighted the importance of sociocultural factors, such as the legal and moral responsibility of families in mainland China for caring for those with mental illness. The authors identified differences in perspectives between caregivers, who wanted their family member to attain the “best” job, and their relatives with schizophrenia, who wanted to find a job they liked. They concluded that, in collectivist cultures, provision of vocational interventions may benefit from taking a family‐oriented rather than individualistic approach.

Countering the focus on competitive employment as the only important outcome for people with SMI, a high‐quality Spanish study explored volunteering as a vocational intervention 68 (Kmet 100). People with SMI reported that volunteering provided them with a role and responsibilities and supported them in rebuilding a valued identity and sense of a “normal life”, affirming that vocational activities deliver benefits beyond earning an income.

Social interventions delivered at the group or individual client level (see Table 3)

Community participation

Nine studies evaluating interventions aimed to improve the community participation of people with SMI were identified, three of which were quantitative75, 76, 77, five qualitative78, 79, 80, 81, 82, and one employed mixed methods 83 . Three of the studies were conducted in the US76, 79, 83, two in Canada80, 82, and one each in Australia 78 , China 75 , Hungary 77 and the UK81.

A high‐quality RCT 77 (Kmet 92) conducted in Hungary investigated the impact of two types of community‐based psychosocial intervention (a community social club and case management) on social cognition and functional outcomes compared to a matched TAU control group. The authors reported a significant improvement in functional outcomes for participants in both intervention groups at six‐month follow‐up, with the most significant gains in social cognition found amongst those allocated to the community‐based club. They concluded that the club's “supportive social milieu” enabled consumers to engage in more social interactions and practice new social roles, which they posited would, in turn, enable greater societal engagement.

A well‐established, internationally recognized approach to bringing people with SMI together in a “supportive social milieu” to promote community participation is the Clubhouse. This has a strong peer‐led ethos, whereby members are responsible for the everyday running of the programme and mutually supported within the peer structure to achieve a wide range of psychosocial goals, including social and work‐based skills.

An RCT conducted in China 75 (Kmet 75) reported greater improvements in social functioning and self‐determination in participants randomly allocated to join a Clubhouse compared to a standard care control group at six‐month follow‐up.

The Clubhouse approach has also been evaluated through robust qualitative studies. Prince et al 79 (Kmet 85) first identified the key features of the approach through focus groups involving 20 Clubhouse members. These features were then assessed for importance through interviews with a further 150 members. Respondents particularly valued the flexibility of the Clubhouse structure, which they attributed to the lack of organizational hierarchy, the variety of activities provided to support the development of social skills, and the availability of activities outside, as well as within, office hours.

In addition, a large qualitative study of a Clubhouse in Canada80 (Kmet 95) found that the co‐leadership by peers and staff was fundamental to its culture. Other critical aspects included unconditional acceptance, promotion of self‐efficacy and mutual respect. Members reported that being part of the Clubhouse reduced social isolation and stigma and provided them with a sense of purpose, accomplishment and belonging.

A variety of other activity‐based group programmes aiming to improve people's confidence and community participation have also been studied. The Gould Farm programme, described as providing “recovery‐focused, milieu treatment on a 700‐acre working farm, that integrates counselling and medication with a work program providing opportunities for the development of daily living, social, and work skills as well as mental and physical health” was evaluated through an uncontrolled, pre‐post study 76 (Kmet 86). Participants showed improvements in psychosocial functioning of medium effect size, and maintenance of gains six months after finishing the programme. At 36‐month follow‐up, it was reported that participants had subsequently been able to gain work or volunteering positions, attend mainstream education, or participate in hobbies.