Abstract

Background

Small observational studies have suggested that statin users have a lower risk of dying with COVID‐19. We tested this hypothesis in a large, population‐based cohort of adults in 2 of Canada’s most populous provinces: Ontario and Alberta.

Methods and Results

We examined reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction swab positivity rates for SARS‐CoV‐2 in adults using statins compared with nonusers. In patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, we compared 30‐day risk of all‐cause emergency department visit, hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, or death in statin users versus nonusers, adjusting for baseline differences in demographics, clinical comorbidities, and prior health care use, as well as propensity for statin use. Between January and June 2020, 2.4% of 226 142 tested individuals aged 18 to 65 years, 2.7% of 88 387 people aged 66 to 75 years, and 4.1% of 154 950 people older than 75 years had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction swab for SARS‐CoV‐2. Compared with 353 878 nonusers, the 115 871 statin users were more likely to test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 (3.6% versus 2.8%, P<0.001), but this difference was not significant after adjustment for baseline differences and propensity for statin use in each age stratum (adjusted odds ratio 1.00 [95% CI, 0.88–1.14], 1.00 [0.91–1.09], and 1.06 [0.82–1.38], respectively). In individuals younger than 75 years with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, statin users were more likely to visit an emergency department, be hospitalized, be admitted to the intensive care unit, or to die of any cause within 30 days of their positive swab result than nonusers, but none of these associations were significant after multivariable adjustment. In individuals older than 75 years with SARS‐CoV‐2, statin users were more likely to visit an emergency department (28.2% versus 17.9%, adjusted odds ratio 1.41 [1.23–1.61]) or be hospitalized (32.7% versus 21.9%, adjusted odds ratio 1.19 [1.05–1.36]), but were less likely to die (26.9% versus 31.3%, adjusted odds ratio 0.76 [0.67–0.86]) of any cause within 30 days of their positive swab result than nonusers.

Conclusions

Compared with statin nonusers, patients taking statins exhibit the same risk of testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 and those younger than 75 years exhibit similar outcomes within 30 days of a positive test. Patients older than 75 years with a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test and who were taking statins had more emergency department visits and hospitalizations, but exhibited lower 30‐day all‐cause mortality risk.

Keywords: COVID‐19, outcomes, SARS‐CoV‐2, statins

Subject Categories: Mortality/Survival, Risk Factors

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HFRS

Hospital Frailty Risk Score

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

In 469 749 adults tested for SARS‐COV‐2, statin users exhibited the same risk of testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 as nonusers and those younger than 75 years exhibited similar outcomes within 30 days of a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test.

Statin users 75 years or older with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection exhibited lower 30‐day all‐cause mortality risk but more emergency department visits and hospitalizations than nonusers.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

While statins have many indications for which they are definitively beneficial, their use was not associated with lower (or higher) risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or with better (or poorer) outcomes in those with COVID‐19 in our cohort.

Several factors (such as diabetes or chronic kidney disease) are known to predispose individuals to infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 and to poor outcomes in those who develop COVID‐19. 1 The impact of chronic medications on the risk of COVID‐19 is uncertain, but of intense interest. Statins are some of the most commonly prescribed medications in North America. Although best known for their cardiovascular benefits, statins have wide‐ranging anti‐inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and even antiviral effects. However, statins have also been shown in animal studies to increase the cellular expression of angiotensin‐converting enzyme II, the primary receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2. 2 , 3 A recent report on 1219 statin‐treated patients hospitalized in Hubei Province, China suggested that treatment with statins was associated with a 40% lower risk of 28‐day all‐cause mortality 4 and an analysis of 170 patients in the United States 5 reported that statin users had a lower risk of severe COVID‐19 and exhibited faster recovery times. A subsequent meta‐analysis that included 6 other observational studies reported that the risk of death with COVID‐19 was 46% lower in statin users compared with nonusers. 6 Despite these promising observational data, it is perhaps worth remembering that while numerous cohort studies in the pre‐COVID‐19 era reported that statin users exhibited better outcomes with pneumonia or sepsis, 7 a meta‐analysis of 9 randomized trials demonstrated no difference in 28‐day hospital mortality with statin treatment in patients with non‐COVID‐19 infections. 8

Thus, we designed this study to test whether current use of statins is associated with increased susceptibility of adults to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and/or poorer outcomes in those with a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test. Using large‐scale, population‐based cohorts in Alberta and Ontario (2 of Canada’s most populous provinces), we measured the association between current use of statins and infection rates among adults who underwent SARS‐CoV‐2 testing; we also assessed the association of current statin use with outcomes in adults with laboratory‐confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

METHODS

Data Disclosure

To comply with each province’s Health Information Protection Act and in order to minimize the possibility of unintentionally sharing information that can be used to re‐identify private information, the data set cannot be made publicly available; however, requests to access the data set from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the corresponding author (Dr. Finlay McAlister) at finlay.mcalister@ualberta.ca.

Subjects and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in the provinces of Alberta and Ontario, Canada. Both provinces have government‐funded single‐payer health care systems that provide universal access to essential services to all residents, with no charges at the point of care. This study received ethics approval from the Health Ethics Research Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00101096) with a waiver of informed consent for Alberta patients because we used de‐identified administrative data. The use of Ontario data is authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act and does not require review by a Research Ethics Board. In both provinces, each individual is assigned a unique personal health care number, and we used these numbers to identify and link the records for each adult in 6 health care databases. These included the following: the Discharge Abstract Database (which captures the most responsible [or primary] diagnosis and up to 24 other diagnoses for all acute‐care hospitalizations in the provinces), the Provincial Laboratory Databases (which capture all SARS‐CoV‐2 reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction [RT‐PCR] test results), the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (which captures all visits to emergency departments with up to 10 diagnoses per visit), outpatient physician billing claims, the Alberta Pharmacy Information Network, and the Ontario Drug Benefit Plan. The validity and completeness of coding for medical diagnoses in these data sets have been previously established. 9 , 10 The Alberta Pharmacy Information Network database captures data on drug dispensations (date, dose, and quantity dispensed) from >98% of outpatient pharmacies in the province and for patients of all ages. 11 The Ontario Drug Benefit Plan database captures the same information for all prescription claims made to the plan by Ontario residents 65 years and older and some residents under 65 years (primarily those receiving social assistance or with high prescription costs relative to their household income). In Alberta, analyses were conducted within the Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Data Platform. In Ontario, analyses were conducted at ICES (formerly Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences).

Definition of Cases and Index Date

We identified all adults who had a RT‐PCR swab to test for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection between January 1 and June 12, 2020 whether it was done as an outpatient or as an inpatient. For patients tested multiple times during our study, we only examined the data related to their first positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test (or first negative test in those who never tested positive). Index date was the date of the first RT‐PCR test in patients who were never positive, or the date of the first positive if at least 1 of their laboratory tests was positive in this study period. Outcomes including emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and/or deaths in the first 30 days after a positive RT‐PCR test were examined in this population.

Exposure of Interest

The independent dichotomous variable of interest was the receipt of a statin prescription at least once in the 90 days before the index date that was of sufficient quantity that it should have still been available to the patient at their index date. We did not collect specific agents or doses of statins, but simvastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin, and rosuvastatin account for >90% of all statin prescriptions dispensed in these provinces.

Covariates

We identified comorbidities for each patient using standardized and validated International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) and (ICD‐10‐Canada) case definitions based on any hospitalizations, ED visits, and outpatient physician visits in the 5 years before and including the index date using case definitions previously validated in Alberta and Ontario. 12 In addition, we calculated the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS) by assigning point values for the presence of any of 109 ICD‐10 codes in each patient’s hospitalizations in the 2 years before their index date (see the original HFRS publication for the list of the codes and the points assigned for each code). 13 “Frailty” is defined by a score ≥5 on the HFRS, which comprises ICD‐10 codes for frailty‐associated diagnoses such as falls, blindness, spinal compression fractures, osteoporosis, skin ulcers, dementia/delirium, Parkinson disease, urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections, disorders of electrolytes, drug/alcohol abuse, and sequelae of strokes such as hemiplegia, dysphagia, etc. We also captured health care resource use before the time of their index RT‐PCR swab and used the prior 5 years’ hospitalization data to generate Charlson Comorbidity Scores for each individual.

Outcomes

The outcome of interest for our examination of the association between statin use and risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was whether a patient undergoing RT‐PCR swab had a positive test. The outcomes of interest for our examination of the association between statin use and COVID‐19 severity were all‐cause ED visits, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, or deaths in the first 30 days after a positive test for SARS‐CoV‐2. For the purposes of this analysis, we examined test positivity rates and outcomes within 30 days of a positive swab for SARS‐CoV‐2 in 3 subgroups: individuals aged 18 to 65 years (from Alberta only because prescription drug data are available for this age group in Alberta but not Ontario), those aged 66 to 75 years (from both provinces), and those older than 75 years (from both provinces).

Statistical Analysis

We present summary statistics of our data stratified according to the use of statins and stratified by swab test result (COVID positive or negative). We used χ2 tests to examine the association between statin use and our dichotomous outcomes described above (positive test in those undergoing testing and, in a separate analysis, 30‐day outcomes in those with a positive test using the date of testing as the inception date for outcomes analysis). We then conducted a series of multivariable logistic regression analyses to determine the independent association between statin use and each of the outcomes of interest in the 3 prespecified age strata. Beginning with adjustment for age and sex only, we then undertook full adjustment for age, sex, rural versus urban residence, socioeconomic status (from the Pampalon material deprivation index in Alberta and the Ontario Marginalization Index), long‐term care facility residence, HFRS, Charlson score, selected comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, HIV, cancer, atrial fibrillation, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma) and medications dispensed within 90 days before the index, use of ED/hospitals in the 3 months preceding the index date, number of hospitalizations or ED visits in the 12 months before the index date, ethnicity (only available in Ontario), and week of testing. There was no significant collinearity in the included variables.

Because we hypothesized that statin use was a proxy measure for the healthy‐user effect, 14 to minimize confounding and selection bias we also constructed an analysis with the inverse probability of treatment weighting approach using propensity scores. In repeat analyses for all tested individuals and test‐positive individuals separately, overall and by age group, each individual’s probability of being on a statin was estimated from a multivariable logistic regression model including all of the variables listed in the previous paragraph. The inverse probability of treatment weighting was defined as the inverse of the probability of receiving the treatment that the patient received. Stabilized weights, where extreme scores are weighted less, were used because of its robustness to the influence of these extreme scores. 15 Balance in propensity score was examined by the weighted standardized mean difference between statin users and nonusers for each covariate used in calculating the score. We considered a covariate balanced if the standardized difference was <0.1, except in subgroups where the number of patients was <500, where we used a 0.25 cut‐off because of the relatively small sample size. When large weights (>100) occurred in the tail of the propensity score distribution, we truncated the large weight based on 99.9th percentile. After determining each individual’s stabilized weight, we performed weighted logistic regression analyses, regressing each of our outcomes on statin use. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) within each province separately.

We calculated adjusted odds ratio (aOR) within each province separately using the methods above, and then pooled the estimates using meta‐analysis. Although both Alberta and Ontario used a common protocol and common case definitions for comorbidities, there are still several potential sources of heterogeneity between the provinces (such as differences in populations, drug formulary restrictions, data capture, and SARS‐CoV‐2 testing priorities). Therefore, as per the convention of the Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies (https://www.cnodes.ca/), a random effect model was used for this meta‐analysis. Restricted maximum likelihood estimator was used to estimate the population heterogeneity because of its relatively high efficiency compared with other estimators when number of effect sizes is small. 16 , 17 This analysis was conducted using the package “metafor” in R Core Team 2020 (metafor: Meta‐Analysis Package for R. R package version 1.4‐0, URL http://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=metafor).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Those Having Swabs Done

Between January 1 and June 12, 2020, 274 828 Albertans over the age of 18 years had at least 1 RT‐PCR swab for SARS‐CoV‐2 and 6024 (2.2%, including 1.4% of the 48 416 individuals older than 65 years) were positive. In Alberta, the median age of those adults tested was 45 years and 9.8% had >1 swab done during the study period. Of the 48 416 Albertans older than 65 years who were tested, the median age was 76 years, 23.2% were long‐term care residents, 42.7% were male, 39.9% had at least 1 Charlson comorbidity (mean Charlson score 1.1), 46.8% had at least 1 hospitalization or ED visit in the prior year (mean 1.6), 19.7% met the HFRS definition of frail, and 15.8% had more than 1 swab done during the timeframe we studied (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals Tested for SARS‐CoV2, Stratified by Age Group, Province, and Test Result

| Characteristics | Alberta older than 65 y | Ontario older than 65 y | Alberta age 18–65 y | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested | COVID Neg | COVID Pos | P value | Tested | COVID Neg | COVID Pos | P value | Tested | COVID Neg | COVID Pos | P value | |

| Population size, n | 48 416 | 47 734 | 682 | 194 921 | 186 913 | 8008 | 226 412 | 221 070 | 5342 | |||

| Age, y, n (%) unless otherwise state | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 77.8 (9.0) | 77.7 (9.0) | 79.7 (9.5) | <0.0001 | 80.96 (8.93) | 80.89 (8.93) | 82.55 (8.91) | <0.0001 | 41.0 (12.8) | 41.1 (12.9) | 40.8 (12.0) | 0.11 |

| 66–75 | 23 396 (48.3) | 23 121 (48.4) | 275 (40.3) | <0.0001 | 64 991 (33.3) | 62 883 (33.6) | 2108 (26.3) | <0.0001 | ||||

| 76–85 | 13 798 (28.5) | 13 610 (28.5) | 188 (27.6) | 62 596 (32.1) | 60 051 (32.1) | 2545 (31.8) | ||||||

| 85+ | 11 222 (23.2) | 11 003 (23.1) | 219 (32.1) | 67 334 (34.5) | 63 979 (34.2) | 3355 (41.9) | ||||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 27 763 (57.3) | 27 372 (57.3) | 391 (57.3) | 0.99 | 117 077 (60.1) | 112 197 (60.0) | 4880 (60.9) | 0.10 | 132 959 (58.7) | 130 494 (59.0) | 2465 (46.1) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 20 653 (42.7) | 20 362 (42.7) | 291 (42.7) | 77 844 (39.9) | 74 716 (40.0) | 3128 (39.1) | 93 453 (41.3) | 90 576 (41.0) | 2877 (53.9) | |||

| Long‐term care resident, n (%) | 11 247 (23.2) | 11 002 (23.0) | 245 (35.9) | <0.0001 | 61 375 (31.5) | 56 791 (30.4) | 4584 (57.2) | <0.0001 | 1326 (0.6) | 1303 (0.6) | 23 (0.4) | 0.13 |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 5645 (11.7) | 5562 (11.7) | 83 (12.2) | 23 945 (12.3) | 23 644 (12.6) | 301 (3.8) | 21 644 (9.6) | 21 431 (9.7) | 213 (4.0) | |||

| Material deprivation quintile, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 8429 (17.4) | 8309 (17.4) | 120 (17.6) | <0.0001 | 39 904 (20.5) | 38 607 (20.7) | 1297 (16.2) | <0.0001 | 43 576 (19.2) | 42 955 (19.4) | 621 (11.6) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 8144 (16.8) | 8062 (16.9) | 82 (12.0) | 38 145 (19.6) | 36 752 (19.7) | 1393 (17.4) | 42 396 (18.7) | 41 560 (18.8) | 836 (15.6) | |||

| 3 | 6704 (13.8) | 6625 (13.9) | 79 (11.6) | 36 181 (18.6) | 34 542 (18.5) | 1639 (20.5) | 35 832 (15.8) | 35 044 (15.9) | 788 (14.8) | |||

| 4 | 7826 (16.2) | 7781 (16.3) | 45 (6.6) | 37 529 (19.3) | 35 992 (19.3) | 1537 (19.2) | 33 503 (14.8) | 32 726 (14.8) | 777 (14.5) | |||

| 5 (most deprived) | 7455 (15.4) | 7310 (15.3) | 145 (21.3) | 40 634 (20.8) | 38 633 (20.7) | 2001 (25.0) | 39 031 (17.2) | 37 625 (17.0) | 1406 (26.3) | |||

| Unknown | 9858 (20.4) | 9647 (20.2) | 211 (30.9) | 2528 (1.3) | 2387 (1.3) | 141 (1.8) | 32 074 (14.2) | 31 160 (14.1) | 914 (17.1) | |||

| Week of index test, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 0–12 (Jan–Mar) | 3073 (6.3) | 3035 (6.4) | 38 (5.6) | <0.0001 | 7673 (3.9) | 7254 (3.9) | 419 (5.2) | <0.0001 | 25 453 (11.2) | 25 158 (11.4) | 295 (5.5) | <0.0001 |

| 13–16 (Apr) | 10 894 (22.5) | 10 548 (22.1) | 346 (50.7) | 47 499 (24.4) | 43 016 (23.0) | 4483 (56.0) | 53 874 (23.8) | 52 122 (23.6) | 1752 (32.8) | |||

| 17–20 (May) | 14 815 (30.6) | 14 549 (30.5) | 266 (39.0) | 82 111 (42.1) | 79 725 (42.7) | 2386 (29.8) | 70 697 (31.2) | 67 893 (30.7) | 2804 (52.5) | |||

| 21–24 (Jun) | 19 634 (40.6) | 19 602 (41.1) | 32 (4.7) | 57 638 (29.6) | 56 918 (30.5) | 720 (9.0) | 76 388 (33.7) | 75 897 (34.3) | 491 (9.2) | |||

| Number of tests, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 40 782 (84.2) | 40 267 (84.4) | 515 (75.5) | <0.0001 | 146 378 (75.1) | 143 281 (76.7) | 3097 (38.7) | <0.0001 | 206 910 (91.4) | 201 864 (91.3) | 5046 (94.5) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 5776 (11.9) | 5658 (11.9) | 118 (17.3) | 32 269 (16.6) | 30 346 (16.2) | 1923 (24.0) | 16 901 (7.5) | 16 651 (7.5) | 250 (4.7) | |||

| 3+ | 1858 (3.8) | 1809 (3.8) | 49 (7.2) | 16 274 (8.3) | 13 286 (7.1) | 2988 (37.3) | 2601 (1.1) | 2555 (1.2) | 46 (0.9) | |||

| Hospital frailty risk score | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (5.8) | 2.8 (5.8) | 4.3 (7.3) | <0.0001 | 3.07 (5.96) | 3.01 (5.90) | 4.32 (7.16) | <0.0001 | 0.2 (1.5) | 0.2 (1.5) | 0.1 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| <5 | 38 889 (80.3) | 38 408 (80.5) | 481 (70.5) | <0.0001 | 152 440 (78.2) | 146 814 (78.5) | 5626 (70.3) | <0.0001 | 223 200 (98.6) | 217 898 (98.6) | 5302 (99.3) | 0.0002 |

| 5–15 | 6682 (13.8) | 6546 (13.7) | 136 (19.9) | 30 340 (15.6) | 28 786 (15.4) | 1554 (19.4) | 2625 (1.2) | 2593 (1.2) | 32 (0.6) | |||

| >15 | 2845 (5.9) | 2780 (5.8) | 65 (9.5) | 12 141 (6.2) | 11 313 (6.1) | 828 (10.3) | 587 (0.3) | 579 (0.3) | 8 (0.1) | |||

| Hospitalization/ED visits in prior y | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 25 767 (53.2) | 25 359 (53.1) | 408 (59.8) | 0.002 | 97 953 (50.3) | 93 866 (50.2) | 4087 (51.0) | <0.0001 | 158 950 (70.2) | 154 926 (70.1) | 4024 (75.3) | <0.0001 |

| 1 or 2 | 12 259 (25.3) | 12 116 (25.4) | 143 (21.0) | 66 648 (34.2) | 63 778 (34.1) | 2870 (35.8) | 48 624 (21.5) | 47 536 (21.5) | 1088 (20.4) | |||

| 3+ | 10 390 (21.5) | 10 259 (21.5) | 131 (19.2) | 30 320 (15.6) | 29 269 (15.7) | 1051 (13.1) | 18 838 (8.3) | 18 608 (8.4) | 230 (4.3) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (3.0) | 1.6 (3.0) | 1.3 (2.4) | 0.0168 | 1.21 (2.17) | 1.21 (2.18) | 1.08 (1.78) | <0.0001 | 0.8 (2.8) | 0.8 (2.8) | 0.5 (1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalization/ED visit in prior 3 mo, n (%) | 10 587 (21.9) | 10 471 (21.9) | 116 (17.0) | 0.002 | 22 519 (11.6) | 21 482 (11.5) | 1037 (12.9) | <0.0001 | 25 664 (11.3) | 25 219 (11.4) | 445 (8.3) | <0.0001 |

| Resource intensity weights from hosp/ED visits in prior y, mean (SD) | 1.3 (3.8) | 1.3 (3.7) | 1.7 (4.8) | 0.0011 | 2.20 (4.89) | 2.17 (4.85) | 2.95 (5.74) | <0.0001 | 0.2 (1.6) | 0.2 (1.6) | 0.1 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Charlson Index, based on prior 5 y | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 29 078 (60.1) | 28 724 (60.2) | 354 (51.9) | <0.0001 | 104 328 (53.5) | 100 636 (53.8) | 3692 (46.1) | <0.0001 | 215 090 (95.0) | 209 903 (94.9) | 5187 (97.1) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 6535 (13.5) | 6416 (13.4) | 119 (17.4) | 30 227 (15.5) | 28 740 (15.4) | 1487 (18.6) | 5242 (2.3) | 5167 (2.3) | 75 (1.4) | |||

| 2 | 4745 (9.8) | 4653 (9.7) | 92 (13.5) | 21 946 (11.3) | 20 891 (11.2) | 1055 (13.2) | 2999 (1.3) | 2946 (1.3) | 53 (1.0) | |||

| 3+ | 8058 (16.6) | 7941 (16.6) | 117 (17.2) | 38 420 (19.7) | 36 646 (19.6) | 1774 (22.2) | 3081 (1.4) | 3054 (1.4) | 27 (0.5) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.8) | 1.2 (1.7) | 0.15 | 1.97 (1.97) | 1.96 (1.98) | 1.99 (1.84) | 0.327 | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| COPD or asthma | 6272 (13.0) | 6219 (13.0) | 53 (7.8) | <0.0001 | 52 382 (26.9) | 50 353 (26.9) | 2029 (25.3) | 0.002 | 5495 (2.4) | 5441 (2.5) | 54 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 15 963 (33.0) | 15 726 (32.9) | 237 (34.8) | 0.32 | 55 229 (28.3) | 52 572 (28.1) | 2657 (33.2) | <0.0001 | 19 585 (8.7) | 19 051 (8.6) | 534 (10.0) | 0.0004 |

| Hypertension | 35 933 (74.2) | 35 404 (74.2) | 529 (77.6) | 0.04 | 155 246 (79.6) | 148 609 (79.5) | 6637 (82.9) | <0.0001 | 38 916 (17.2) | 37 897 (17.1) | 1019 (19.1) | 0.0002 |

| Prior stroke (exclude TIA) | 1750 (3.6) | 1717 (3.6) | 33 (4.8) | 0.09 | 9182 (4.7) | 8665 (4.6) | 517 (6.5) | <0.0001 | 542 (0.2) | 534 (0.2) | 8 (0.1) | 0.17 |

| Coronary artery disease | 4789 (9.9) | 4725 (9.9) | 64 (9.4) | 0.66 | 26 849 (13.8) | 25 932 (13.9) | 917 (11.5) | <0.0001 | 2300 (1.0) | 2269 (1.0) | 31 (0.6) | 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 3965 (8.2) | 3907 (8.2) | 58 (8.5) | 0.76 | 18 938 (9.7) | 18 085 (9.7) | 853 (10.7) | 0.004 | 751 (0.3) | 743 (0.3) | 8 (0.1) | 0.02 |

| Cancer | 16 544 (34.2) | 16 349 (34.3) | 195 (28.6) | 0.002 | 43 922 (22.5) | 42 331 (22.6) | 1591 (19.9) | <0.0001 | 19 765 (8.7) | 19 479 (8.8) | 286 (5.4) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 3165 (6.5) | 3126 (6.5) | 39 (5.7) | 0.38 | 2263 (1.16) | 2165 (1.16) | 98 (1.22) | 0.59 | 10 076 (4.5) | 9828 (4.4) | 248 (4.6) | 0.49 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 149 (21.0) | 9995 (20.9) | 154 (22.6) | 0.30 | 31 103 (16.0) | 29 675 (15.9) | 1428 (17.8) | <0.0001 | 5324 (2.4) | 5217 (2.4) | 107 (2.0) | 0.09 |

| HIV | 35 (0.1) | 35 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.48 | 236 (0.1) | 225 (0.1) | 11 (0.1) | 0.67 | 481 (0.2) | 468 (0.2) | 13 (0.2) | 0.62 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 8228 (17.0) | 8108 (17.0) | 120 (17.6) | 0.67 | 47 392 (24.3) | 45 372 (24.3) | 2020 (25.2) | 0.05 | 2781 (1.2) | 2741 (1.2) | 40 (0.7) | 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 6969 (14.4) | 6844 (14.3) | 125 (18.3) | 0.003 | 51 328 (26.3) | 48 823 (26.1) | 2505 (31.3) | <0.0001 | 6371 (2.8) | 6246 (2.8) | 125 (2.3) | 0.034 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| ACEi, ARBs, or ARNIs | 19 689 (40.7) | 19 454 (40.8) | 235 (34.5) | 0.0009 | 78 148 (40.1) | 75 004 (40.1) | 3144 (39.3) | 0.12 | 21 345 (9.4) | 20 798 (9.4) | 547 (10.2) | 0.04 |

| Steroid | 3483 (7.2) | 3455 (7.2) | 28 (4.1) | 0.002 | 14 194 (7.3) | 13 812 (7.4) | 382 (4.8) | <0.0001 | 6577 (2.9) | 6479 (2.9) | 98 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| α‐Blockers | 265 (0.5) | 260–264 | 1–5* | 0.89 | 4086 (2.1) | 3930 (2.1) | 156 (1.9) | 0.35 | 542 (0.2) | 537–541 | 1–5* | 0.01 |

| β‐Blockers | 11 105 (22.9) | 10 950 (22.9) | 155 (22.7) | 0.90 | 52 372 (26.9) | 50 227 (26.9) | 2145 (26.8) | 0.86 | 7072 (3.1) | 6954 (3.1) | 118 (2.2) | 0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 9690 (20.0) | 9550 (20.0) | 140 (20.5) | 0.74 | 51 993 (26.7) | 49 655 (26.6) | 2338 (29.2) | <0.0001 | 7776 (3.4) | 7544 (3.4) | 232 (4.3) | 0.0002 |

| Hydralazine | 318 (0.7) | 312 (0.7) | 6 (0.9) | 0.47 | 2077 (1.1) | 1948 (1.0) | 129 (1.6) | <0.0001 | 92 (0.0) | 87–91 | 1–5* | 0.91 |

| Nitrates | 1866 (3.9) | 1853 (3.9) | 13 (1.9) | 0.008 | 8205 (4.2) | 7869 (4.2) | 336 (4.2) | 0.95 | 533 (0.2) | 528–532 | 1–5* | 0.03 |

| Diuretics | 11 084 (22.9) | 10 924 (22.9) | 160 (23.5) | 0.72 | 51 019 (26.2) | 48 920 (26.2) | 2099 (26.2) | 0.94 | 8342 (3.7) | 8202 (3.7) | 140 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Centrally acting antihypertensive | 162 (0.3) | 157–161 | 1–5* | 0.25 | 588 (0.3) | 566 (0.3) | 22 (0.3) | 0.65 | 853 (0.4) | 846 (0.4) | 7 (0.1) | 0.003 |

| Anticoagulants | 5421 (11.2) | 5352 (11.2) | 69 (10.1) | 0.37 | 33 239 (17.1) | 31 837 (17.0) | 1402 (17.5) | 0.27 | 1523 (0.7) | 1506 (0.7) | 17 (0.3) | 0.001 |

| Metformin | 5447 (11.3) | 5361 (11.2) | 86 (12.6) | 0.26 | 25 437 (13.0) | 24 137 (12.9) | 1300 (16.2) | <0.0001 | 7113 (3.1) | 6906 (3.1) | 207 (3.9) | 0.002 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1284 (2.7) | 1262 (2.6) | 22 (3.2) | 0.35 | 6193 (3.2) | 5942 (3.2) | 251 (3.1) | 0.82 | 2665 (1.2) | 2587 (1.2) | 78 (1.5) | 0.05 |

| GLP‐1 receptor agonists | 446 (0.9) | 441–445 | 1–5* | 0.60 | 1590 (0.8) | 1530 (0.8) | 60 (0.7) | 0.50 | 2245 (1.0) | 2214 (1.0) | 31 (0.6) | 0.002 |

| DPP4 inhibitors | 1681 (3.5) | 1655 (3.5) | 26 (3.8) | 0.62 | 18 301 (9.4) | 17 293 (9.3) | 1008 (12.6) | <0.0001 | 2117 (0.9) | 2042 (0.9) | 75 (1.4) | 0.0003 |

| Sulfonamides | 1349 (2.8) | 1335 (2.8) | 14 (2.1) | 0.24 | 7397 (3.8) | 6984 (3.7) | 413 (5.2) | <0.0001 | 1487 (0.7) | 1450 (0.7) | 37 (0.7) | 0.74 |

| TZDs | 95 (0.2) | 90–94 | 1–5* | 0.56 | 65 (0.0) | 60–64 | 1–5* | 0.15 | 126 (0.1) | 121–125 | 1–5* | 0.99 |

| Insulin | 2532 (5.2) | 2484 (5.2) | 48 (7.0) | 0.03 | 13 574 (7.0) | 12 899 (6.9) | 675 (8.4) | <0.0001 | 3427 (1.5) | 3369 (1.5) | 58 (1.1) | 0.01 |

ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNIs, angiotensin‐receptor neprilysin inhibitors; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DDP4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors; ED, emergency department; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1; SGLT2, sodium/glucose cotransporter member 2; TIA, transient ischemic attack; and TZDs, thiazolidinediones.

When cell sizes are less than 5 the exact number is suppressed per Canadian privacy legislation for healthcare databases.

In the same timeframe, 194 921 Ontarians older than 65 years had at least 1 RT‐PCR swab for SARS‐CoV‐2 and 8008 (4.1%) were positive. In Ontario, the median age of elderly individuals tested was 81 years, 31.5% were long‐term care residents, 39.9% were male, 46.5% had at least 1 Charlson comorbidity, 49.7% had at least 1 hospitalization or ED visit in the prior year, 21.8% met the HFRS definition of frail, and 24.9% had >1 swab done during the study period (Table 1).

Of note, 16.9% of the long‐term care residents in Alberta had at least 1 hospitalization or ED visit in the 3 months before their COVID test index date versus 5.8% of the long‐term care residents in Ontario in the 3 months before their COVID test index date.

Statin Users Versus Nonusers

The majority of adults undergoing RT‐PCR swabs were not on cardiovascular or glucose‐lowering medications (Table 2); statins were the most commonly prescribed cardiovascular medication and were used by 7.0% of adults aged 18 to 65 years and 41.1% of those older than 65 years tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in our cohort. Statin users were older, more likely to have atherosclerosis‐related comorbidities, prior hospitalizations/ED visits, and higher HFRS and Charlson scores in all age groups (Table 2). These findings were confirmed in the construction of the multivariable propensity score for being prescribed a statin using these data, which had c‐statistics of 0.91 in Alberta and 0.76 in Ontario. Across statin propensity score quintiles, the rates of SARS‐CoV‐2 test positivity varied (2.1% versus 1.4% versus 1.5% versus 0.98% versus 1.2% in Alberta and 5.1% versus 3.8% versus 4.2% versus 3.8% versus 3.6% in Ontario) but hospitalizations increased (11.4% versus 14.5% versus 21.2% versus 23.0% versus 28.9% in Alberta and 15.6% versus 26.1% versus 27.3% versus 32.8% versus 40.5% in Ontario, both P<0.001 for trend). This latter result empirically demonstrates that indication bias is present in that patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes were more likely to be taking statins prepandemic.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals Tested for SARS‐CoV2, Stratified by Age Group, Province, and Statin Use

| Alberta older than 65 y | Ontario older than 65 y | Alberta age 18–65 y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested | Non‐statin user | Statin user | P value | Tested | Non‐statin user | Statin user | P value | Tested | Non‐statin user | Statin user | P value | |

| Population size, n | 48 416 | 31 166 | 17 250 | 194 921 | 112 039 | 82 882 | 226 412 | 210 673 | 15 739 | |||

| Age, y, n (%) unless otherwise stated | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 77.8 (9.0) | 78.4 (9.5) | 76.5 (7.8) | <0.0001 | 80.96 (8.93) | 81.81 (9.4) | 79.81 (8.15) | <0.0001 | 41.0 (12.8) | 40.0 (12.5) | 55.6 (7.6) | <0.0001 |

| 66–75 | 23 396 (48.3) | 14 479 (46.5) | 8917 (51.7) | <0.0001 | 64 991 (33.3) | 35 422 (31.6) | 29 569 (35.7) | <0.0001 | ||||

| 76–85 | 13 798 (28.5) | 8206 (26.3) | 5592 (32.4) | 62 596 (32.1) | 32 520 (29.0) | 30 076 (36.3) | ||||||

| 85+ | 11 222 (23.2) | 8481 (27.2) | 2741 (15.9) | 67 334 (34.5) | 44 097 (39.4) | 23 237 (28.0) | ||||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 27 763 (57.3) | 19 441 (62.4) | 8322 (48.2) | <0.0001 | 117 077 (60.1) | 73 836 (65.9) | 43 241 (52.2) | <0.0001 | 132 959 (58.7) | 125 870 (59.7) | 7089 (45.0) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 20 653 (42.7) | 11 725 (37.6) | 8928 (51.8) | 77 844 (39.9) | 38 203 (34.1) | 39 641 (47.8) | 93 453 (41.3) | 84 803 (40.3) | 8650 (55.0) | |||

| Long‐term care resident, n (%) | 11 247 (23.2) | 8644 (27.7) | 2603 (15.1) | <0.0001 | 61 375 (31.5) | 41 397 (36.9) | 19 978 (24.1) | <0.0001 | 1326 (0.6) | 966 (0.5) | 360 (2.3) | <0.0001 |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 5645 (11.7) | 3687 (11.8) | 1958 (11.4) | 0.12 | 23 945 (12.3) | 14 532 (13.0) | 9413 (11.4) | 21 644 (9.6) | 19 773 (9.4) | 1871 (11.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Material deprivation quintile, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 8429 (17.4) | 5404 (17.3) | 3025 (17.5) | <0.0001 | 39 904 (20.5) | 23 679 (21.1) | 16 225 (19.6) | <0.0001 | 43 576 (19.2) | 40 999 (19.5) | 2577 (16.4) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 8144 (16.8) | 5252 (16.9) | 2892 (16.8) | 38 145 (19.6) | 22 368 (20.0) | 15 777 (19.0) | 42 396 (18.7) | 39 622 (18.8) | 2774 (17.6) | |||

| 3 | 6704 (13.8) | 4214 (13.5) | 2490 (14.4) | 36 181 (18.6) | 20 782 (18.5) | 15 399 (18.6) | 35 832 (15.8) | 33 241 (15.8) | 2591 (16.5) | |||

| 4 | 7826 (16.2) | 4938 (15.8) | 2888 (16.7) | 37 529 (19.3) | 21 134 (18.9) | 16 395 (19.8) | 33 503 (14.8) | 30 818 (14.6) | 2685 (17.1) | |||

| 5 (most deprived) | 7455 (15.4) | 4507 (14.5) | 2948 (17.1) | 40 634 (20.8) | 22 627 (20.2) | 18 007 (21.7) | 39 031 (17.2) | 35 514 (16.9) | 3517 (22.3) | |||

| Unknown | 9858 (20.4) | 6851 (22.0) | 3007 (17.4) | 2528 (1.3) | 1449 (1.3) | 1079 (1.3) | 32 074 (14.2) | 30 479 (14.5) | 1595 (10.1) | |||

| Week of index test, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 0–12 (Jan–Mar) | 3073 (6.3) | 1958 (6.3) | 1115 (6.5) | 0.56 | 7673 (3.9) | 4171 (3.7) | 3502 (4.2) | <0.0001 | 25 453 (11.2) | 23 999 (11.4) | 1454 (9.2) | <0.0001 |

| 13–16 (Apr) | 10 894 (22.5) | 6994 (22.4) | 3900 (22.6) | 47 499 (24.4) | 27 876 (24.9) | 19 623 (23.7) | 53 874 (23.8) | 50 095 (23.8) | 3779 (24.0) | |||

| 17–20 (May) | 14 815 (30.6) | 9506 (30.5) | 5309 (30.8) | 82 111 (42.1) | 49 741 (44.4) | 32 370 (39.1) | 70 697 (31.2) | 65 688 (31.2) | 5009 (31.8) | |||

| 21–24 (Jun) | 19 634 (40.6) | 12 708 (40.8) | 6926 (40.2) | 57 638 (29.6) | 30 251 (27.0) | 27 387 (33.0) | 76 388 (33.7) | 70 891 (33.6) | 5497 (34.9) | |||

| Number of tests, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 40 782 (84.2) | 26 147 (83.9) | 14 635 (84.8) | 0.02 | 146 378 (75.1) | 83 925 (74.9) | 62 453 (75.4) | <0.0001 | 206 910 (91.4) | 192 711 (91.5) | 14 199 (90.2) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 5776 (11.9) | 3806 (12.2) | 1970 (11.4) | 32 269 (16.6) | 18 956 (16.9) | 13 313 (16.1) | 16 901 (7.5) | 15 621 (7.4) | 1280 (8.1) | |||

| 3+ | 1858 (3.8) | 1213 (3.9) | 645 (3.7) | 16 274 (8.3) | 9158 (8.2) | 7116 (8.6) | 2601 (1.1) | 2341 (1.1) | 260 (1.7) | |||

| Hospital frailty risk score | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (5.8) | 2.8 (5.9) | 2.8 (5.6) | 0.34 | 3.07 (5.96) | 2.97 (5.95) | 3.20 (5.97) | <0.0001 | 0.2 (1.5) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.8 (2.9) | <0.0001 |

| <5 | 38 889 (80.3) | 25 013 (80.3) | 13 876 (80.4) | 0.001 | 152 440 (78.2) | 88 427 (78.9) | 64 013 (77.2) | <0.0001 | 223 200 (98.6) | 208 257 (98.9) | 14 943 (94.9) | <0.0001 |

| 5–15 | 6682 (13.8) | 4237 (13.6) | 2445 (14.2) | 30 340 (15.6) | 16 665 (14.9) | 13 675 (16.5) | 2625 (1.2) | 1998 (0.9) | 627 (4.0) | |||

| >15 | 2845 (5.9) | 1916 (6.1) | 929 (5.4) | 12 141 (6.2) | 6947 (6.2) | 5194 (6.3) | 587 (0.3) | 418 (0.2) | 169 (1.1) | |||

| Hospitalization/ED visits in prior year | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 25 767 (53.2) | 17 324 (55.6) | 8443 (48.9) | <0.0001 | 97 953 (50.3) | 60 153 (53.7) | 37 800 (45.6) | <0.0001 | 158 950 (70.2) | 149 240 (70.8) | 9710 (61.7) | <0.0001 |

| 1 or 2 | 12 259 (25.3) | 7708 (24.7) | 4551 (26.4) | 66 648 (34.2) | 36 783 (32.8) | 29 865 (36.0) | 48 624 (21.5) | 44 798 (21.3) | 3826 (24.3) | |||

| 3+ | 10 390 (21.5) | 6134 (19.7) | 4256 (24.7) | 30 320 (15.6) | 15 103 (13.5) | 15 217 (18.4) | 18 838 (8.3) | 16 635 (7.9) | 2203 (14.0) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (3.0) | 1.5 (2.9) | 1.8 (3.2) | <0.0001 | 1.21 (2.17) | 1.08 (2.05) | 1.38 (2.31) | <0.0001 | 0.8 (2.8) | 0.8 (2.7) | 1.3 (3.7) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalization/ED visit in prior 3 mo, n (%) | 10 587 (21.9) | 6334 (20.3) | 4253 (24.7) | <0.0001 | 22 519 (11.6) | 11 281 (10.1) | 11 238 (13.6) | <0.0001 | 25 664 (11.3) | 23 152 (11.0) | 2512 (16.0) | <0.0001 |

| Resource intensity weights from hosp/ED visits in prior year, mean (SD) | 1.3 (3.8) | 1.2 (3.9) | 1.3 (3.5) | 0.28 | 2.20 (4.89) | 2.30 (5.57) | 2.08 (3.96) | <0.0001 | 0.2 (1.6) | 0.2 (1.5) | 0.5 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Charlson Index, based on prior 5 y | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 29 078 (60.1) | 19 659 (63.1) | 9419 (54.6) | <0.0001 | 104 328 (53.5) | 65 300 (58.3) | 39 028 (47.1) | <0.0001 | 215 090 (95.0) | 202 931 (96.3) | 12 159 (77.3) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 6535 (13.5) | 4391 (14.1) | 2144 (12.4) | 30 227 (15.5) | 18 679 (16.7) | 11 548 (13.9) | 5242 (2.3) | 3769 (1.8) | 1473 (9.4) | |||

| 2 | 4745 (9.8) | 2900 (9.3) | 1845 (10.7) | 21 946 (11.3) | 11 519 (10.3) | 10 427 (12.6) | 2999 (1.3) | 2130 (1.0) | 869 (5.5) | |||

| 3+ | 8058 (16.6) | 4216 (13.5) | 3842 (22.3) | 38 420 (19.7) | 16 541 (14.8) | 21 879 (26.4) | 3081 (1.4) | 1843 (0.9) | 1238 (7.9) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.9) | <0.0001 | 1.97 (1.97) | 1.68 (1.86) | 2.31 (2.06) | <0.0001 | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.5 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| COPD or asthma | 6272 (13.0) | 3536 (11.3) | 2736 (15.9) | <0.0001 | 52 382 (26.9) | 27 818 (24.8) | 24 564 (29.6) | <0.0001 | 5495 (2.4) | 4381 (2.1) | 1114 (7.1) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 15 963 (33.0) | 7750 (24.9) | 8213 (47.6) | <0.0001 | 55 229 (28.3) | 21 013 (18.8) | 34 216 (41.3) | <0.0001 | 19 585 (8.7) | 12 402 (5.9) | 7183 (45.6) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 35 933 (74.2) | 21 080 (67.6) | 14 853 (86.1) | <0.0001 | 155 246 (79.6) | 82 207 (73.4) | 73 039 (88.1) | <0.0001 | 38 916 (17.2) | 28 553 (13.6) | 10 363 (65.8) | <0.0001 |

| Prior stoke (exclude TIA) | 1750 (3.6) | 799 (2.6) | 951 (5.5) | <0.0001 | 9182 (4.7) | 3326 (3.0) | 5856 (7.1) | <0.0001 | 542 (0.2) | 256 (0.1) | 286 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 4789 (9.9) | 1535 (4.9) | 3254 (18.9) | <0.0001 | 26 849 (13.8) | 7409 (6.6) | 19 440 (23.5) | <0.0001 | 2300 (1.0) | 680 (0.3) | 1620 (10.3) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 3965 (8.2) | 2202 (7.1) | 1763 (10.2) | <0.0001 | 18 938 (9.7) | 8521 (7.6) | 10 417 (12.6) | <0.0001 | 751 (0.3) | 371 (0.2) | 380 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer | 16 544 (34.2) | 10 454 (33.5) | 6090 (35.3) | <0.0001 | 43 922 (22.5) | 24 999 (22.3) | 18 923 (22.8) | 0.007 | 19 765 (8.7) | 17 236 (8.2) | 2529 (16.1) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 3165 (6.5) | 1994 (6.4) | 1171 (6.8) | 0.10 | 2263 (1.16) | 1317 (1.18) | 946 (1.14) | 0.49 | 10 076 (4.5) | 8610 (4.1) | 1466 (9.3) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 149 (21.0) | 5463 (17.5) | 4686 (27.2) | <0.0001 | 31 103 (16.0) | 12 995 (11.6) | 18 108 (21.8) | <0.0001 | 5324 (2.4) | 3375 (1.6) | 1949 (12.4) | <0.0001 |

| HIV | 35 (0.1) | 18 (0.1) | 17 (0.1) | 0.1097 | 236 (0.1) | 99 (0.1) | 137 (0.2) | <0.0001 | 481 (0.2) | 428 (0.2) | 53 (0.3) | 0.0004 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 8228 (17.0) | 4792 (15.4) | 3436 (19.9) | <0.0001 | 47 392 (24.3) | 24 026 (21.4) | 23 366 (28.2) | <0.0001 | 2781 (1.2) | 2018 (1.0) | 763 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 6969 (14.4) | 4232 (13.6) | 2737 (15.9) | <0.0001 | 51 328 (26.3) | 28 004 (25.0) | 23 324 (28.1) | <0.0001 | 6371 (2.8) | 5283 (2.5) | 1088 (6.9) | <0.0001 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| ACEi, ARBs, or ARNIs | 19 689 (40.7) | 9052 (29.0) | 10 637 (61.7) | <0.0001 | 78 148 (40.1) | 31 547 (28.2) | 46 601 (56.2) | <0.0001 | 21 345 (9.4) | 12 758 (6.1) | 8587 (54.6) | <0.0001 |

| Steroid | 3483 (7.2) | 2091 (6.7) | 1392 (8.1) | <0.0001 | 14 194 (7.3) | 7700 (6.9) | 6494 (7.8) | <0.0001 | 6577 (2.9) | 5580 (2.6) | 997 (6.3) | <0.0001 |

| α‐Blockers | 265 (0.5) | 122 (0.4) | 143 (0.8) | <0.0001 | 4086 (2.1) | 1429 (1.3) | 2657 (3.2) | <0.0001 | 542 (0.2) | 440 (0.2) | 102 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| β‐Blockers | 11 105 (22.9) | 4685 (15.0) | 6420 (37.2) | <0.0001 | 52 372 (26.9) | 20 749 (18.5) | 31 623 (38.2) | <0.0001 | 7072 (3.1) | 3989 (1.9) | 3083 (19.6) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 9690 (20.0) | 4727 (15.2) | 4963 (28.8) | <0.0001 | 51 993 (26.7) | 23 720 (21.2) | 28 273 (34.1) | <0.0001 | 7776 (3.4) | 4897 (2.3) | 2879 (18.3) | <0.0001 |

| Hydralazine | 318 (0.7) | 117 (0.4) | 201 (1.2) | <0.0001 | 2077 (1.1) | 684 (0.6) | 1393 (1.7) | <0.0001 | 92 (0.0) | 39 (0.0) | 53 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Nitrates | 1866 (3.9) | 668 (2.1) | 1198 (6.9) | <0.0001 | 8205 (4.2) | 2928 (2.6) | 5277 (6.4) | <0.0001 | 533 (0.2) | 161 (0.1) | 372 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Diuretics | 11 084 (22.9) | 5720 (18.4) | 5364 (31.1) | <0.0001 | 51 019 (26.2) | 24 170 (21.6) | 26 849 (32.4) | <0.0001 | 8342 (3.7) | 5521 (2.6) | 2821 (17.9) | <0.0001 |

| Centrally acting antihypertensive | 162 (0.3) | 90 (0.3) | 72 (0.4) | 0.019 | 588 (0.3) | 213 (0.2) | 375 (0.5) | <0.0001 | 853 (0.4) | 704 (0.3) | 149 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Anticoagulants | 5421 (11.2) | 2849 (9.1) | 2572 (14.9) | <0.0001 | 33 239 (17.1) | 15 788 (14.1) | 17 451 (21.1) | <0.0001 | 1523 (0.7) | 997 (0.5) | 526 (3.3) | <0.0001 |

| Metformin | 5447 (11.3) | 1683 (5.4) | 3764 (21.8) | <0.0001 | 25 437 (13.0) | 6953 (6.2) | 18 484 (22.3) | <0.0001 | 7113 (3.1) | 3299 (1.6) | 3814 (24.2) | <0.0001 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1284 (2.7) | 241 (0.8) | 1043 (6.0) | <0.0001 | 6193 (3.2) | 1188 (1.1) | 5005 (6.0) | <0.0001 | 2665 (1.2) | 861 (0.4) | 1804 (11.5) | <0.0001 |

| GLP‐1 receptor agonists | 446 (0.9) | 119 (0.4) | 327 (1.9) | <0.0001 | 1590 (0.8) | 329 (0.3) | 1261 (1.5) | <0.0001 | 2245 (1.0) | 1252 (0.6) | 993 (6.3) | <0.0001 |

| DPP4 inhibitors | 1681 (3.5) | 440 (1.4) | 1241 (7.2) | <0.0001 | 18 301 (9.4) | 4930 (4.4) | 13 371 (16.1) | <0.0001 | 2117 (0.9) | 785 (0.4) | 1332 (8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Sulfonamides | 1349 (2.8) | 391 (1.3) | 958 (5.6) | <0.0001 | 7397 (3.8) | 1878 (1.7) | 5519 (6.7) | <0.0001 | 1487 (0.7) | 563 (0.3) | 924 (5.9) | <0.0001 |

| TZDs | 95 (0.2) | 22 (0.1) | 73 (0.4) | <0.0001 | 65 (0.0) | 13 (0.0) | 52 (0.1) | <0.0001 | 126 (0.1) | 28 (0.0) | 98 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Insulin | 2532 (5.2) | 787 (2.5) | 1745 (10.1) | <0.0001 | 13 574 (7.0) | 3801 (3.4) | 9773 (11.8) | <0.0001 | 3427 (1.5) | 1666 (0.8) | 1761 (11.2) | <0.0001 |

ACEi indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNIs, angiotensin‐receptor neprilysin inhibitors; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DDP4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1; SGLT2, sodium/glucose cotransporter member 2; TIA, transient ischemic attack; and TZDs, thiazolidinediones.

Swab Positivity Rates

Between January 1 and June 12, 2020, 6024 (2.2%) adult Albertans who were tested had a positive swab for SARS‐CoV‐2, ranging from 4.5% in April to 0.5% in June. More than 88% of tested patients were younger than 65 years and the positivity rate was highest (2.4%) in those aged 18 to 65 years. In Albertans older than 65 years, the positivity rates were 2.2% in long‐term care residents and 1.2% in those living in the community. In the same timeframe, 8008 (4.1%) Ontarians over the age of 65 years who were tested had a positive swab for SARS‐CoV‐2, ranging from 9.4% in April to 1.2% in June, with the highest positivity rate being in those older than 85 years (5.0%).

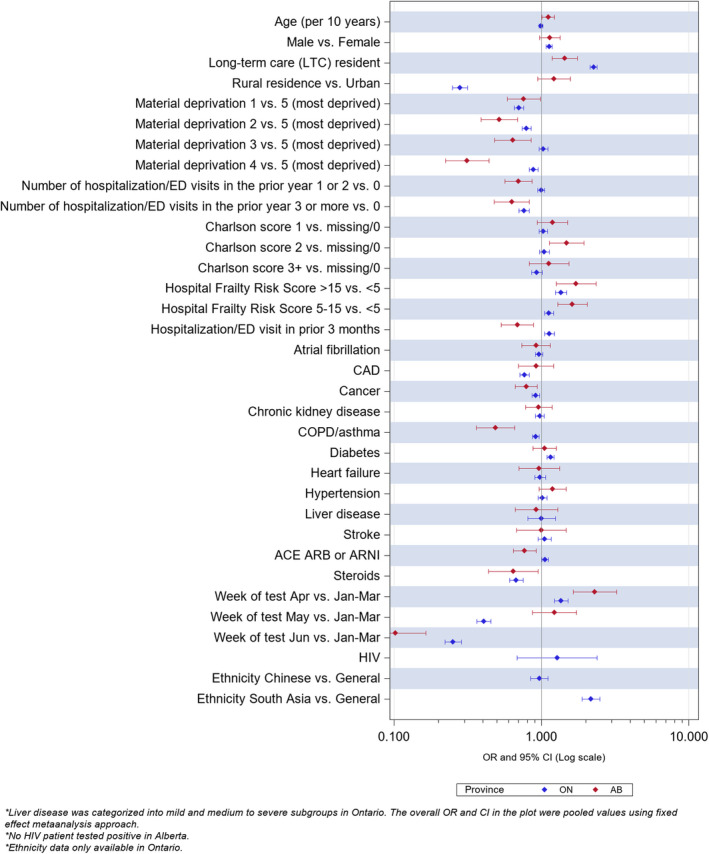

Test positivity rates were inversely associated with socioeconomic status in both provinces and in both younger and older individuals (Table 1). In persons older than 65 years, those living in long‐term care facilities, frail individuals (HFRS scores >5), older individuals, urban residents, and those with higher Charlson comorbidity scores or diabetes were more likely to test positive (Figure 1). In persons older than 65 years, more RT‐PCR swabs were done in women (57.3% in Alberta and 60.1% in Ontario), although the positivity rates were similar in women and men (1.4% versus 1.4% in Alberta and 4.2% versus 4.0% in Ontario). The use of cardiovascular or glucose‐lowering medications was very similar between those with positive or negative swab results, although use of renin‐angiotensin system inhibitors was higher in Alberta (Table 1).

Figure 1. Multivariate predictors of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in Albertans and Ontarians older than age 65 years who were tested.

Ethnicity data not available for Alberta.

In patients aged 18 to 65 years (n=226 412) or older than 75 years (n=154 950), statin users were not more likely to test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 (2.2% versus 2.4%, P=0.32, and aOR 1.00 [95% CI, 0.88–1.14] in those 18–65; 4.1% versus 4.0%, P=0.50, and aOR 1.06 [0.82–1.38] in those older than 75 years, Table 3). In 88 387 patients aged 66 to 75 years, statin users were more likely to test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 (2.8% versus 2.6%, P=0.03), although this difference was no longer evident after adjustment for propensity score (aOR 1.00 [95% CI, 0.91–1.09], Table 3).

Table 3.

Swab Positivity Rates in Statin Users Versus Nonusers by Age Strata

| Age strata | Number with positive swab (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | OR adjusted for age and sex only (95% CI) | Fully adjusted OR (95% CI) | aOR from logistic regression with IPTW (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Non‐user | Statin user | |||||

| Age between 18 and 65 y | 5342 (2.36) | 4989 (2.37) | 353 (2.24) | 0.95 (0.85–1.06) | 0.96 (0.86–1.08) | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) |

| Age between 66–75 y | 2383 (2.70) | 1293 (2.59) | 1090 (2.83) | 1.05 (0.96–1.14) | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) |

| Age >75 y | 6307 (4.07) | 3772 (4.04) | 2535 (4.11) | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 1.11 (0.93–1.33) | 1.06 (0.82–1.38) |

aOR indicates adjusted odds ratio; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting analysis using propensity scores; and OR, odds ratio.

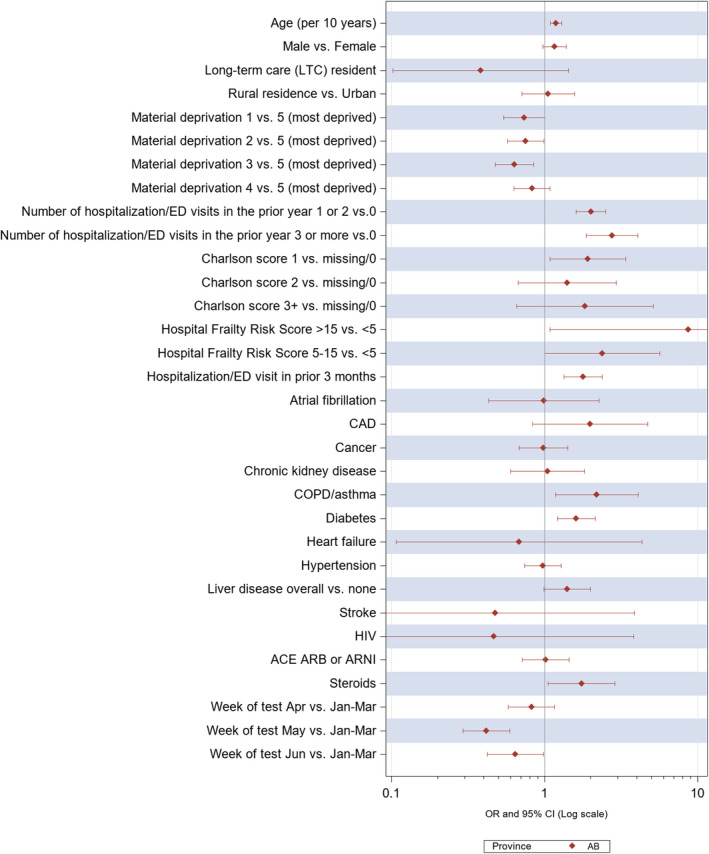

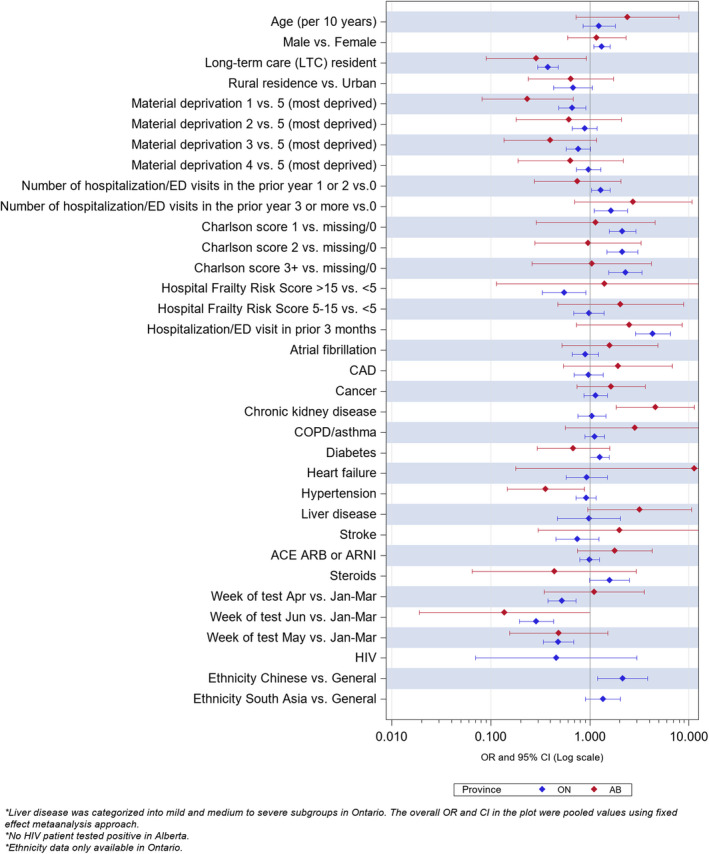

Thirty‐Day Outcomes After a Positive SARS‐CoV‐2 Swab

In the 7725 individuals aged 18 to 65 and 66 to 75 years with a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in both provinces, statin users were more likely to visit an ED, be hospitalized, be admitted to ICU, or die of any cause within 30 days of their positive swab result than nonusers. However, none of these differences were significant after adjustment for baseline differences and propensity for statin use (Table 4 and Figures 2 and 3).

Table 4.

Events Within 30 Days of a Positive SARS‐CoV‐2 Test Result, by Statin Use, n (%)

| Cohort | Number in each age stratum with outcomes | Crude OR (95% CI) | OR adjusted for age and sex only (95% CI) | Fully adjusted OR (95% CI) | aOR from logistic regression with IPTW (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Non‐statin user | Statin user | |||||

| Age between 18 and 65 y | 5342 | 4989 | 353 | ||||

| All‐cause hospitalization | 183 (3.43) | 147 (2.95) | 36 (10.20) | 3.74 (2.55–5.48) | 2.05 (1.37–3.09) | 1.25 (0.73–2.14) | 0.81 (0.42–1.58) |

| At least 1 ED visit | 618 (11.57) | 554 (11.10) | 64 (18.13) | 1.77 (1.33–2.36) | 1.38 (1.02–1.86) | 0.82 (0.56–1.19) | 0.45 (0.27–0.75) |

| ICU admission | 39 (0.73) | 27 (0.54) | 12 (3.40) | 6.47 (3.25–12.88) | 3.18 (1.51–6.70) | 2.93 (1.28–6.69) | 2.30 (0.87–6.08) |

| Death | 8 (0.15) | 6 (0.12) | 2 (0.57) | 4.73 (0.95–23.53) | 2.03 (0.37–11.02) | 0.46 (0.09–2.41) | 0.29 (0.00–58.33) |

| Death or ICU admission | 43 (0.8) | 30 (0.60) | 13 (3.68) | 6.32 (3.27–12.23) | 3.08 (1.51–6.28) | 2.94 (1.15–7.48) | 2.13 (0.82–5.55) |

| Any event (any outcome above within 30 d) | 648 (12.13) | 582 (11.67) | 66 (18.70) | 1.74 (1.31–2.31) | 1.34 (1.00–1.81) | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) | 0.45 (0.28–0.74) |

| Age between 66–75 y | 2383 | 1293 | 1090 | ||||

| All‐cause hospitalization | 766 (32.14) | 397 (30.70) | 369 (33.85) | 1.13 (0.95–1.35) | 1.09 (0.92–1.3) | 0.84 (0.66–1.06) | 0.91 (0.73–1.12) |

| At least one ED visit | 820 (34.41) | 440 (34.03) | 380 (34.86) | 1.07 (0.80–1.43) | 1.05 (0.78–1.41) | 0.90 (0.72–1.12) | 1.01 (0.82–1.25) |

| ICU admission | 232 (9.74) | 115 (8.89) | 117 (10.73) | 0.86 (0.29–2.56) | 0.82 (0.28–2.39) | 0.57 (0.21–1.59) | 0.51 (0.12–2.23) |

| Death | 290 (12.17) | 131 (10.13) | 159 (14.59) | 1.50 (1.17–1.92) | 1.45 (1.12–1.86) | 1.19 (0.86–1.64) | 1.07 (0.78–1.48) |

| Death or ICU admission | 436 (18.3) | 213 (16.47) | 223 (20.46) | 1.17 (0.73–1.85) | 1.15 (0.76–1.73) | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) |

| Any event (any outcome above within 30 d) | 1170 (49.1) | 618 (47.80) | 552 (50.64) | 1.10 (0.93–1.30) | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 0.90 (0.73–1.11) | 0.93 (0.76–1.14) |

| Age >75 y | 6307 | 3772 | 2535 | ||||

| All‐cause hospitalization | 1657 (26.27) | 827 (21.92) | 830 (32.74) | 1.8 (1.43–2.26) | 1.50 (1.33–1.70) | 1.41 (0.83–2.38) | 1.19 (1.05–1.36) |

| At least one ED visit | 1388 (22.01) | 674 (17.87) | 714 (28.17) | 1.82 (1.62–2.06) | 1.54 (1.37–1.75) | 1.41 (1.10–1.82) | 1.41 (1.23–1.61) |

| ICU admission | 200 (3.17) | 95 (2.52) | 105 (4.14) | 2.68 (0.64–11.22) | 1.92 (0.46–8.03) | 2.08 (0.35–12.29) | 1.61 (0.42–6.21) |

| Death | 1865 (29.57) | 1182 (31.34) | 683 (26.94) | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 0.85 (0.76–0.95) | 0.81 (0.69–0.96) | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) |

| Death or ICU admission | 1954 (30.98) | 1229 (32.58) | 725 (28.60) | 0.83 (0.75–0.92) | 0.86 (0.76–0.96) | 0.82 (0.72–0.93) | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) |

| Any event (any outcome above within 30 d) | 3127 (49.58) | 1786 (47.35) | 1341 (52.90) | 1.38 (0.98–1.96) | 1.38 (0.86–2.20) | 1.08 (0.76–1.53) | 0.97 (0.87–1.09) |

aOR indicates adjusted odds ratio; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IPTW indicates inverse probability of treatment weighting analysis using propensity scores; and OR, odds ratio.

Figure 2. Multivariate predictors of any event in the 30 days after a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in individuals younger than 65 years.

Figure 3. Multivariate predictors of any event in the 30 days after a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in those aged 66 to 75 years.

Ethnicity data not available for Alberta. Number of individuals with HIV and a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in this age group was <5 in Alberta and thus data not reportable because of privacy restrictions.

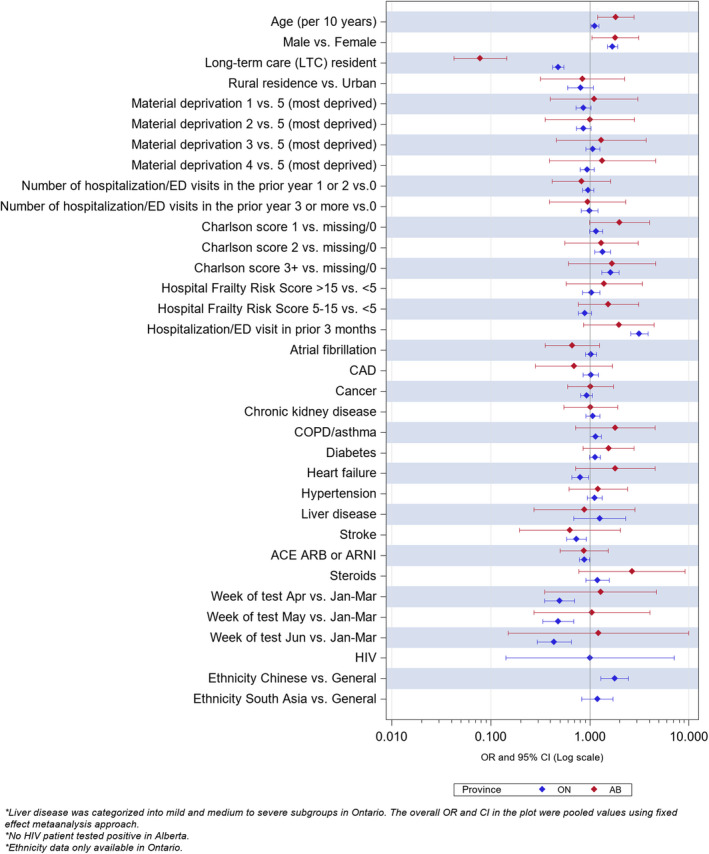

In the 6307 individuals older than 75 years who had SARS‐CoV‐2 in both provinces, the 2535 statin users were more likely to visit an ED (28.2% versus 17.9%, aOR 1.41 [1.23–1.61]) or be hospitalized (32.7% versus 21.9%, aOR 1.19 [1.05–1.36]), but were less likely to die (26.9% versus 31.3%, aOR 0.76 [0.67–0.86]) of any cause within 30 days of their positive swab result than nonusers (Table 4, Figure 4).

Figure 4. Multivariate predictors of any event in the 30 days after a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in those older than 75 years.

Ethnicity data not available for Alberta. Number of individuals with HIV and a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 swab in this age group was <5 in Alberta and thus data not reportable because of privacy restrictions.

DISCUSSION

We found that patients taking statins are not at higher risk of testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 or having adverse events within 30 days of a positive test. While adults using statins were more likely to test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, they were also older and sicker than statin nonusers such that there were no significant differences in positivity rates after adjustment for age, clinical covariates, differences in socioeconomic status and living situations, and propensity for statin use. Similarly, while a higher proportion of statin users younger than 75 years who had COVID‐19 exhibited poorer outcomes than statin nonusers, this was a reflection of their underlying health characteristics since statin use was not independently associated with outcome differences in those younger than 75 years with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Finally, despite the observation that statin use in people over age 75 years with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was associated with significantly more ED presentations and hospitalizations, there were significantly fewer deaths of any cause.

Many of the associations we observed—that individuals with higher socioeconomic were less likely to test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2, that older individuals, those living in long‐term care facilities, or those with markers of frailty or diabetes were more likely to be swab positive—are not unexpected. While our finding that those with more hospitalizations or ED presentations before the pandemic were less likely to test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 may seem counterintuitive, we believe it reflects the fact that these individuals (presumably more likely to have had chronic illnesses) may have been following public health advice to shelter in place and reduce their exposure risk. Alternately, it may also be a manifestation of collider bias 18 in that these individuals may have been more likely to have been tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 even if asymptomatic. It is interesting that these associations were in the opposite direction (higher 30‐day event rates in those with higher Charlson scores and more prepandemic health care use) for patients who had COVID‐19. The fact that long‐term care residents exhibited lower rates of hospitalization and ED use than their community‐dwelling peers likely reflects the fact that their caregivers or health care providers chose not to transfer them to acute care settings during the pandemic.

Although statins generally have an excellent safety profile in humans, randomized trials of statins 19 failed to demonstrate any benefits in sepsis in the pre‐COVID era. Thus, our finding that statin use was not associated with a lower risk of being SARS‐CoV‐2 swab positive or better outcomes in adults younger than age 75 years with COVID‐19 is not surprising. Our finding of a lower mortality risk in patients older than 75 years with COVID‐19 perhaps reflects the fact that not all deaths in patients with COVID‐19 are because of the infection itself or multi‐organ failure but that some are because of thromboembolic disease or coronary events (which would be expected to be less likely in statin users and also represent a higher proportion of deaths in very elderly patients with COVID‐19). 20 An alternate explanation for higher ED visits but fewer deaths in statin users older than 75 years could be selection bias and residual confounding. Specifically, a preventive therapy such as a statin is more likely to be prescribed to elderly individuals who are relatively well (“healthy‐users”) and that these same patients are also more likely to see physicians on a regular basis, undergo recommended screening tests, exercise, eat well, stop smoking, be immunized, and be more adherent to medications and public health guidance (all nonmeasured potential confounders of our results). 14

Several limitations of our study merit consideration. First, we did not have data on the indications for or doses of statin prescribed. Second, we defined statin use as those patients who had filled 1 or more statin prescriptions; while we do not have data on whether patients actually took these medications, this would bias our study towards finding a benefit from statin use because more adherent patients (ie, those who fill a prescription) tend to have better outcomes (the healthy user effect). This limitation, in fact, serves to strengthen our finding that statin use was not associated with lower risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or better outcomes in those age <75 years with COVID‐19. Third, we are unable to adjust for unmeasured confounders such as body mass index, race or ethnicity, smoking, or health care–seeking behavior. Fourth, we do not have any data on goals of care for patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 and thus are unable to adjust for factors such as palliative or comfort care, which are strong confounders of outcomes. 21 Fifth, the total number of deaths or ICU admission within 30 days in those 18 to 65 years of age was small and given the sensitivity of the inverse probability of treatment weighting method to the weight of rare events, it is not unexpected to see differences between the results from regression methods and inverse probability of treatment weighting. Sixth, while there are undoubtedly sources of heterogeneity between Alberta and Ontario (such as differences in populations, formulary restrictions, data capture, and SARS‐CoV‐2 testing priorities), we believe that calculating aOR separately in each province and then pooling the effect estimates between the 2 provinces using a random‐effects model minimizes any effect such differences would have on our results (of note, using a fixed‐effects model yielded similar effect estimates, just with narrower confidence intervals, but did not change which associations were significant and which were not). Seventh, because our data were collected on cases up to June 12, 2020, they reflect experience with the wild‐type SARS‐CoV‐2 and before variants of concern began circulating in Canada. Finally, we examined all‐cause events in patients after a positive swab for SARS‐CoV‐2 and cannot comment on specific causes for those ED visits, ICU admissions, or deaths (ie, cardiac versus noncardiac, COVID versus other, etc).

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results stand in stark contrast to the previously published small observational studies 4 , 5 , 6 suggesting benefits with statins in COVID‐19 that we discussed in our introduction. However, our study is several magnitudes larger and we were able to adjust for a host of potential confounders and also included an analysis weighted by propensity for statin use that those studies did not. This confirms the longstanding tenet that there are caveats to observational studies that limit extrapolating their findings to recommendations about treatment. Given our sample size and findings, we do not think randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of statins on COVID‐19 outcomes are likely to be informative in patients younger than 75 years. In fact, preliminary results from the INSPIRATION‐S (The Intermediate Versus Standard‐Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation in Critically‐Ill Patients With COVID‐19: An Open Label Randomized Controlled Trial ‐ Statin) trial revealed no mortality difference for atorvastatin versus placebo in 587 patients with COVID‐19 admitted to ICUs. 22 Based on our data demonstrating mortality of 31.3% at 30 days in those older than 75 years not taking statins, we estimate that ≈7000 patients would need to be randomized to statin versus placebo to establish or refute (with 80% power) at least a 10% mortality difference with statin use in individuals with COVID‐19 over age 75 years. Until such a randomized trial is conducted, we believe the most reasonable assumption is that while statins have many indications for which definitive proof of their benefit already exists, prevention of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or improving outcomes in those hospitalized with COVID‐19 are unproven. However, our data do demonstrate the safety of continuing statin therapy in patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2.

APPENDIX

CORONA Collaboration Members

University of Toronto: Husam Abdel‐Qadir, Peter Austin, Charles de Mestral, Shaun Goodwin, Andrew Ha, Moira Kapral, Dennis Ko, Jeff Kwong, Douglas Lee, Paula Rochon, Idan Roifman, Heather Ross, Michael Schull, Louise Sun, Jacob Udell, Bo Wang, Harindra Wijeysundera, Amy Yu. University of Alberta: Kevin Bainey, Jeff Bakal, Justin Ezekowitz, Russ Greiner, Sunil Kalmady, Padma Kaul, Finlay McAlister, Sean van Diepen, Robert Welsh, Cindy Westerhout. Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA: Cynthia Jackevicius. University of Ottawa: Peter Liu. University of California, Los Angeles, CA: Roopinder Sandhu.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research COVID‐19 Rapid Research Funding Opportunity grant (# VR4 172736). The Ontario portion of this study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long‐Term Care (MLTC). The Alberta portion of this study was supported by the Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Support Unit.

Disclosures

Dr McAlister holds the Alberta Health Services Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, Dr Lee is the Ted Rogers Chair in Heart Function Outcomes, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Dr Austin is supported by a Mid‐Career Investigator Award from the Heart & Stroke Foundation, and Dr Goodman holds the Heart & Stroke Foundation of Ontario/University of Toronto Polo Chair. Dr Goodman serves as a consultant and has indicated other interests for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly and Company, Esperion, Ferring, GlaxoSmithKline, HLS Therapeutics, JAMP Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, SANOFI PASTEUR INC, Servier, Valeo Pharma. Dr Goodman also serves on the data and safety monitoring board for Daiichi Sankyo Company and Novo Nordisk. Dr Udell has received grants from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen Research & Development, LLC. Dr Udell serves as a consultant for Novartis and Sanofi. Dr Udell has indicated other interests with Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Sanofi. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

The Ontario portion of this study is based on data supplied by the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long‐Term Care (MLTC), the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), and Cancer Care Ontario (CCO). The opinions, results, view, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of their Drug Information File. The Alberta portion of this study is based on data provided by Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not represent the views of the Government of Alberta or Alberta Health Services. Neither the Government of Alberta nor Alberta Health Services express any opinion in relation to this study.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 18.

Contributor Information

Finlay A. McAlister, Email: finlay.mcalister@ualberta.ca.

for the CORONA Collaboration:

Husam Abdel‐Qadir, Charles de Mestral, Shaun Goodwin, Andrew Ha, Moira Kapral, Jeff Kwong, Paula Rochon, Idan Roifman, Heather Ross, Michael Schull, Louise Sun, Bo Wang, Harindra Wijeysundera, Amy Yu, Kevin Bainey, Jeff Bakal, Justin Ezekowitz, Russ Greiner, Sunil Kalmady, Robert Welsh, Cindy Westerhout, Peter Liu, and Roopinder Sandhu

REFERENCES

- 1. Wynants L, van Calster B, Collins GS, Riley RD, Heinze G, Schuite E, Bonten MMJ, Dahly DL, Damen JA, Debray TPA, et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of Covid‐19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2020;369:m1328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schmidt NM, Wing PAC, McKeating JA, Maini MK. Cholesterol‐modifying drugs in COVID‐19. Oxf Open Immunol. 2020;1:iqaa001. doi: 10.1093/oxfimm/iqaa001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fajgenbaum DC, Rader DJ. Teaching old drugs new tricks: statins for COVID‐19? Cell Metab. 2020;32:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang X‐J, Qin J‐J, Cheng XU, Shen L, Zhao Y‐C, Yuan Y, Lei F, Chen M‐M, Yang H, Bai L, et al. In‐hospital use of statins is associated with a reduced risk of mortality among individuals with COVID‐19. Cell Metab. 2020;32:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daniels LB, Sitapati AM, Zhang J, Zou J, Bui QM, Ren J, Longhurst CA, Criqui MH, Messer K. Relation of statin use prior to admission to severity and recovery among COVID‐19 inpatients. Am J Cardiol. 2020;136:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Permana H, Huang I, Purwiga A, Kusumawardhani NY, Sihite TA, Martanto E, Wisaksana R, Soetedjo NNM. In‐hospital use of statins is associated with a reduced risk of mortality in coronavirus‐2019 (COVID‐19): systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pharmacol Rep. 2021;73:769–780. doi: 10.1007/s43440-021-00233-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma Y, Wen X, Peng J, Lu Y, Guo Z, Lu J. Systematic review and meta‐analysis on the association between outpatient statins use and infectious disease‐related mortality. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen M, Ji M, Si X. The effects of statin therapy on mortality in patients with sepsis: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11578. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quan H, Li B, Duncan Saunders L, Parsons GA, Nilsson CI, Alibhai A, Ghali WA; for the IMECCHI Investigators . Assessing validity of ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1424–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tu JV, Chu A, Donovan LR, Ko DT, Booth GL, Tu K, Maclagan LC, Guo H, Austin PC, Hogg W, et al. The Cardiovascular Health in Ambulatory Care Research Team (CANHEART): using big data to measure and improve cardiovascular health and healthcare services. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:204–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ye M, Vena JE, Johnson JA, Xu JY, Eurich DT. Validation of drug prescription records for senior patients in Alberta’s Tomorrow Project: assessing agreement between two population‐level administrative pharmaceutical databases in Alberta, Canada. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28:1417–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Fortin M, Guthrie B, Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Klarenbach SW, Lewanczuk R, Manns BJ, Ronksley P, et al.; for the Alberta Kidney Disease Network . Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: application to administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:31. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0155-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, Keeble E, Smith P, Ariti C, Arora S, Street A, Parker S, Roberts HC, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391:1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chewning B. The healthy adherer and the placebo effect. BMJ. 2006;333:18–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7557.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, Shetterly S, Blanchette C, Smith D. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health. 2010;13:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00671.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viechtbauer W. Bias and efficiency of meta‐analytic variance estimators in the random‐effects model. J Educ Behav Stat. 2005;30:261–293. doi: 10.3102/10769986030003261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Viechtbauer W. Confidence intervals for the amount of heterogeneity in meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2007;26:37–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.2514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griffith GJ, Morris TT, Tudball MJ, Herbert A, Mancano G, Pike L, Sharp GC, Sterne J, Palmer TM, Davey Smith G, et al. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID‐19 disease risk and severity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaborators . Efficacy and safety of cholesterol‐lowering treatment: meta‐analysis of data from 90,506 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elezkurtaj S, Greuel S, Ihlow J, Michaelis EG, Bischoff P, Kunze CA, Sinn BV, Gerhold M, Hauptmann K, Ingold‐Heppner B, et al. Causes of death and comorbidities in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:4263. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82862-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McAlister FA, Wang J, Donovan L, Lee DS, Armstrong PW, Tu JV. The influence of patient goals of care on performance measures in patients hospitalized for heart failure—an analysis of the EFFECT Registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:481–488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. INSPIRATION‐S Study Results . Oral Presentation by Dr. Behnood Bikdeli at the American College of Cardiology Virtual Annual Scientific Session (ACC 2021). May 16, 2021.