Highlights

-

•

Community health workers could be important actors in facing the pandemic.

-

•

The pandemic led to a deterioration of working conditions of CHWs.

-

•

CHWs are exposed to disparities within the health workforce.

-

•

The situation experienced by CHWs reveals the struggles of Brazil’s vulnerable.

-

•

The pandemic has contributed to distancing vulnerable groups from the State.

Keywords: Covid-19 pandemic, Community Health Workers, Vulnerabilities, Health Workforce

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in calls for an increased integration of community health workers (CHWs) into the health system response. Historically, CHWs can play an important role in ensuring the sustainability of health policy implementation – by addressing social determinants of health and maintaining care for ongoing health problems. Their frontline work, with close contact to populations, places CHWs in a position of increased vulnerability to becoming infected and to being the target of abuse and violence. These vulnerabilities compound underlying problems faced by CHWs, who often come from poor backgrounds, are insufficiently paid and receive inadequate training. Speaking to a scarcity of studies on how CHWs are impacted by the pandemic, this paper conducts a systematic study of CHWs in Brazil. Based on quantitative and qualitative data collected during June and July 2020, it considers perceptions and experiences of CHWs, comparing them with other health professionals. We study the extent to which the pandemic added to existing vulnerabilities and created new problems and imbalances in the work of CHWs. We conclude that COVID-19 led to a deterioration of the working conditions of CHWs, of their relations with other health professionals, and of their ability to carry out their essential work in the public health system.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the difficulties faced by frontline health workers around the world. The disease has been associated with increased mortality amongst physicians and other health care workers [1], [2]. Other physical symptoms such as exhaustion, pain and discomfort resulting from the new work routine and from prolonged personal protective equipment (PPE) usage have been reported by health workers [3]. Psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, insomnia and post-traumatic stress have become widespread, stemming from traumatic situations, exhaustion, isolation, social distancing, and lack or inadequate PPE – all of this exacerbated by unrelenting media reporting [4]. There have also been reports of harassment, abuse, discrimination and stigmatization of frontline staff [5]. These impacts are not limited to frontline workers, as the pandemic is having knock-on effects across health systems. It has also been argued that COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to contribute to compassion fatigue in the health system as a whole [6], [7].

Community health workers (CHWs) are close-to-community providers with no specialized medical training who operate as links between physicians, nursing staff and remote or vulnerable groups [8]. Often recruited from the communities they serve, CHWs can specialize in one task or carry out many: identifying the health needs of populations, particularly neglected groups like women, the elderly and the disabled; gathering epidemiological information; scheduling consultations; accompanying patients in long-term medication; supporting vaccination and vector-control programmes; and promoting health education and disease prevention [9].

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, authors have emphasized the crucial importance of CHWs in the health emergency response. CHWs can perform essential functions in the response such as regular monitoring of vulnerable people at home and, if individuals develop symptoms, conducting simple assessments, referring them for formal care as appropriate and collecting essential surveillance data [10], [11]. In addition to their emergency-response work, CHWs can play an important role in addressing social determinants of health during the pandemic [12], and in maintaining delivery of care for ongoing health problems, such as epilepsy [13].The importance of CHW programmes is particularly evident in low-and middle-income countries, and in countries with less-resilient health systems [14]. Nonetheless, there have also been calls for deploying CHW programmes in developed countries like the United States of America [15], and in the context of more robust health systems, such as the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), that are struggling with the unprecedented demands presented by the pandemic [16].

Calls for an increased integration of CHWs into the pandemic response need to be supplemented by in-depth studies of how these workers are being impacted, the risks they are facing in their frontline activities, what has worked and what has failed on the ground-level of the response. Only on the basis of such an assessment will it be possible to develop mechanisms for ensuring the health and safety of CHWs – an essential first step for the effectiveness of their work.

We seek to address this gap by conducting a systematic study of the impact of the pandemic among CHWs in Brazil. The academic literature has explored in general terms the impact of the pandemic upon Brazilian health workers and the challenges they have faced, particularly regarding policy coordination and access to PPE and training [17]. Moreover, when specific health professions are considered, the literature has overwhelmingly focused on physicians and nursing staff [18], [19].

It is important to point out that some studies have considered the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon Brazilian CHWs [11], [20]. The present article brings four key innovations. Firstly, it combines qualitative and quantitative analysis of how CHWs are experiencing the pandemic. Secondly, it is based on data collected during the pandemic; this enables a “real time” analysis based on what workers are experiencing while facing the crisis. Thirdly, the paper innovates by taking into account the situation faced by different elements of the Brazilian public health workforce. Specifically, it considers CHWs alongside nursing staff and physicians. Although we do not intend to make a systematic comparison of professions, data from nursing staff and physicians helps to highlight the inequalities and specific vulnerabilities experienced by CHWs in a way that has not been done before in the literature. Finally, this paper takes a ‘bottom-up’ approach, looking closely at perceptions of CHWs, expressed in statements made during the pandemic. Taking the standpoint of the experiences of CHWs, we study the extent to which the pandemic added to existing vulnerabilities and created new problems and imbalances in their work. We explore whether the pandemic has contributed to a deterioration of the working conditions of CHWs, of their relations with other health professionals, and of their ability to carry out their essential work in the public health system. Our study contributes to the assessment of the Brazilian pandemic response and of the impact of the crisis in terms of reproducing and exacerbating the vulnerabilities of Brazil’s CHWs, a crucial component of the country’s frontline health staff.

Our analysis is made more relevant because of the disastrous response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Jair Bolsonaro, the Brazilian president, denied from the start the importance of the health emergency [21], [22]. He deliberately acted to undermine the recommendations of public health authorities, incentivized public gatherings and systematically refused to wear masks and, most recently, he claims that he did not take the vaccine. The actions and omissions of his government prevented a nationwide consensus to emerge on the necessity of social distancing, business closures and other measures to face the pandemic [23]. Under Bolsonaro’s helm, the federal government failed to assume a central coordination role in the pandemic response effort. This led to disarray on the frontlines and added extra pressure on health professionals, including CHWs.

2. The work of CHWs in the Brazilian health system before the COVID-19 pandemic

In Brazil, the public Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]) is organized along three levels of care: primary health care (PHC), specialized level and the hospital level. PHC is the entry point of the system, responsible for disease prevention and health promotion and reaching 75,41% of the population [24]. CHWs are part of the country’s Family Health Strategy (Estratégia Saúde da Família [ESF]), the primary health care arm of the SUS. The ESF is implemented by multi-professional teams that provide health care inside clinics and in people’s homes. Each team includes a physician, one nurse and 4–6 CHWs .

To ensure that services are provided directly to the families, the program relies heavily on the frontline work of CHWs, who bridge the ESF teams and citizens, particularly the most vulnerable. Their responsibilities include: health education and promotion; keeping records of individuals and families in their area; making regular household visits to monitor the welfare of patients; and contributing to vaccination and vector-control campaigns [25]. There are 40,000 ESF teams and 286,000 CHWs in Brazil24. Scholars point out that the proximity of CHWs to their community is an important factor to increase access to health services [26]. Also, CHWs translate policies into local knowledge, making them more intelligible to citizens and more adjusted to their daily lives – an important component of health promotion [27], [28]. As a result of their work, in the last decades CHWs have contributed to important improvements in health conditions, namely a decrease of infant mortality and improvements in wellbeing indexes [29], [30].

The lives and work of Brazilian CHWs are traversed by vulnerability. Many are poor and from non-white backgrounds. They are overwhelmingly women, with overall representation in the ESF teams above 75% and in some cases up to 95% [31]. The profession of CHW is often precarious, with different (formal and informal) selection processes leading to various contractual arrangements where labour rights are normally scarce [32]. Their training is fragmented, unsystematic, uneven across the country and often deployed when CHWs are already on the job [33]. CHWs are normally recruited from the communities where they work, the assumption being that they should hold an insider knowledge of the territories. CHWs are therefore tasked with tackling vulnerabilities while often living in deprivation and while facing the same health risks as other health system users [34]. Proximity to the community means that they face constant demands from community members outside regular working hours and are subject to overwork [35]. Overwork is one of the factors leading to burnout, stress and other psychological and physical problems among CHWs [36]. In many cases, CHWs do not have preferential access to the services provided in the clinics where they are embedded and thus face difficulties in accessing healthcare.

The high representation of women in the CHW profession can partly be explained by the fact that, historically, care-related professions in Brazil are mostly performed by women, who are already overwhelmed with family care and with maintaining community ties [37]. CHW activity thus feeds from traditional visions of women as carers permeating Brazil’s highly patriarchal society [38]. The expectation that female CHWs “take care” of community members, often in informal ways that go beyond their working-hours and job description, is a condition for the implementation and effectiveness of the ESF.At the same time, it is part and parcel of existing dynamics of vulnerability in Brazilian society, in which gender-based vulnerabilities intersect with race- and class-based ones [39].

In sum, CHWs, already living in a position of vulnerability, are expected to deliver assistance to their communities while receiving little recognition, meagre economic rewards, inadequate training, insufficient occupation health care and little job security. Against this background, the unique challenges posed by the pandemic can be understood as an exogenous crisis, with the potential to create new dynamics of vulnerability or reinforce existing ones.

3. Materials and methods

The context of the pandemic is unique and can be understood as an exogenous crisis which creates new dynamics or places new stresses on existing ones. This is an exploratory mixed method research combining quantitative and qualitative data and analysis. In order to understand the vulnerabilities experienced by CHWs during the pandemic, we used three data collection procedures to triangulate the data. These were: 1) analysis of federal legislation about CHW work during the pandemic; 2) an online survey with Brazilian frontline PHC professionals; 3) online ethnography on Facebook groups.

3.1. Document analysis

We conducted a search of all national-level regulations and governmental guidelines regarding PHC and CHWs between March and July 2020. We collected all documents published during this period (18) and analyzed what they proposed for CHWs work and their protection during the pandemic. Some of these documents (6) proposed changes in the treatment of specific groups, like homeless people, pregnant women, among others. Some (5) introduced changes in procedures inside health clinics, for instance in what pertains to working hours. 7 of these documents advanced recommendations for health workers in general, mainly nurses and physicians. Only one document (“Recommendations for Community Health Workers During the Pandemic”) proposed changes in the work of CHWs during the pandemic [40], [11].

3.2. Online survey

In order to collect “real time” data about how frontline workers experienced the pandemic, between 15th June and 1st July 2020 we carried out an online survey with 1120 Brazilian frontline PHC professionals, including 870 CHWs, 151 Nursing staff and 99 physicians. The focus on different frontline health professionals is justified by our goal of assessing how the pandemic impacted upon existing imbalances and hierarchies in ESF teams. The online survey enabled us to overcome the fieldwork restrictions caused by the pandemic and the need for physical distance [41].

The questions were based on previous research about frontline workers and health emergencies [42]. We created 47 questions, organized in 3 groups: profile; working conditions; and perceptions of changes in work procedures during the pandemic. The variables and questions are summarized on Appendix 1. All questions were revised by academics and tested with 5 volunteer health workers. We also developed tests of coherence, flow and content. The survey, which took 10 min to be completed, was disseminated by social media – Whatsapp, Twitter and Facebook, and by unions and workers’ associations. The response rate, considering the number of people accessing the survey, was 30%. Those who were reached and responded can be considered politically engaged and interested in scientific research. Moreover, the respondents required access to the Internet and to computers or smartphones. This limits the sample of respondents to those who are digitally active. Another limitation of the study is the lack of similar data collected before the pandemic. Recognizing this limitation, our analysis was grounded in other studies describing the lives and work of CHWs prior to the pandemic.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings are important in that they are based on the perceptions of CHWs about their working conditions. In the questions elaborated for the survey, we specifically endeavored to consider the pandemic in light of the past situation, in order to be able to comment on differences and change. Moreover, we triangulated the data from the different sources – survey, Facebook, document analysis and previous academic research – so as to better understand and contextualize the impact of the pandemic.

Due to the fieldwork restrictions, we developed a convenience sample. Our survey does not have probabilistic features, and our quantitative data is used in an exploratory and descriptive way. Our purpose is not to generate statistical generalization. Nonetheless, the socio demographic data of CHW population in Brazil is close to the one we reached in our sample. According to national data, 70% of CHWs are women, more than 50% are non-white, mostly with ages between 30 and 45 years old. Moreover, 70% completed secondary education and they receive, on average, 2 minimum-wages (Milanezi et al. 2020).

Appendix 2 summarizes the profile of the 870 CHW who participated in the online survey. Most CHWs are women (75.5%) and black (70.9%). 53.9% (n = 469) identified themselves as black women, 20% as white women (n = 174), 15.7% as black men (n = 137) and 10.3% as others. Most respondents are between 30 and 49 years old (72.2%) and work in the Northeast (67.4%), one of the poorest regions of the country. Sociodemographic data collected in our survey thus closely matches nationwide sociodemographic data of CHWs, suggesting that a substantial number of our respondents were coming from situations of vulnerability as described in the previous section.

Comparison with other health professionals in PHC highlights the vulnerable position of CHWs regarding gender and race. While the majority of CHW respondents are black women (53.9%), most physicians are white (71.7%). Nursing professionals are overwhelmingly female (86.8%), with some equity between white (48%) and black women (52%). The profile of respondents in Table 1 confirms the divisions of race and gender of Brazilian PHC professionals [43], [44], [45]. Here, again, our sample aligns with national data about the characterization of the health workforce in terms of gender and race: CHWs are mostly black women [39]; nursing staff are mostly women, black and white [46]; and physicians are mostly white men and women [47].

Table 1.

Gender, race and profession of survey participants, June 2020.

| CHW | Nursing Staff | Physicians | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 870 | 151 | 99 |

| Black women | 53,9% | 43,0% | 19,2% |

| Black men | 15,7% | 6% | 6,1% |

| White women | 20,0% | 43,7% | 45,5% |

| White men | 4,1% | 2,6% | 26,3% |

| Others* | 6,2% | 4,6% | 3% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: Online survey: Effects of coronavirus in health workers work conditions. June 2020.

3.3. Facebook private group discussions

We collected data from a public Facebook group with more than 21,000 CHWs from all over Brazil. We analyzed the posts created by CHWs in this group during the period March-July 2020. Around 100 discussions, involving close to 600 CHWs, were observed. All discussions related to the pandemic, including: testimonials on how CHW roles changed; discussions about the risk of working during the pandemic; discussions about whether and how the municipalities were supporting them; discussions about labor issues related to working during the pandemic. We did not track the socio demographic profile of the CHWs engaging in those groups. They can be seen as politically engaged professionals with access to the Internet and to social media. As an extra measure of validation, we triangulated the data collected from Facebook groups with the data collected from the survey.

3.4. Data analysis

Data from the survey was analyzed using descriptive statistics. We compared how CHWs, physicians and nursing staff answered the questions in order to observe differences and similarities in the way they are experiencing the pandemic, namely in terms of access to resources and support. After the descriptive analysis of the quantitative data, we developed a qualitative analysis of the open questions from the survey and from Facebook group discussions. For the qualitative analysis we first developed an axial coding [48] based on three initial codes: material working conditions; institutional support; and changes in the workplace. We then analyzed each code to discern patterns regarding working conditions, institutional support, and perceptions of work-related transformations. Analysis was conducted using SPSS and NVivo 12.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. CHW report poor working conditions during the pandemic

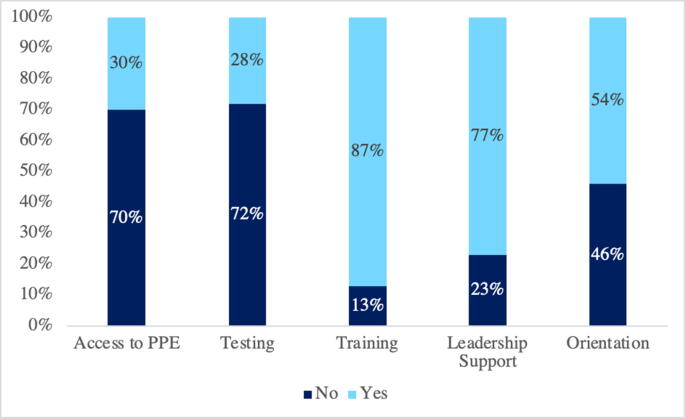

Survey results indicate that during the pandemic CHWs were experienced poor working conditions, and our research suggests that some of their previously existing vulnerabilities were exacerbated [11]. Graph 1 presents the perception of CHWs about working conditions during the pandemic. Only 30% of these CHW claimed to have received adequate PPE; only 28% said they had received testing materials; and only 13% reported that they had undergone some type of training on how to act during the pandemic. During the first six months of the pandemic, the federal government failed to ensure distribution of PPE, tests or other protective measures for CHWs. Government regulations concerning PPE, tests and training, addressed other professions, like nurses and physicians, while failing to consider CHWs.

Graph 1.

CHWs Working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Online survey: Effects of coronavírus in health workers work conditions. June 2020 (n = 870).

In terms of perception of institutional support, 77% of CHWs did not feel supported by management and 46% claimed not to have received direct guidance from their superiors.

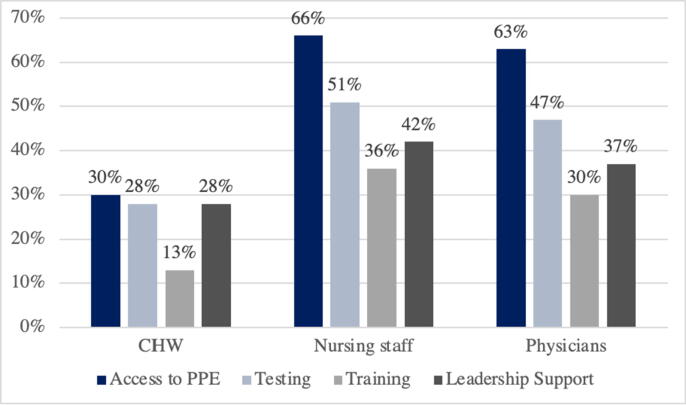

The scenario of vulnerability of CHWs is even clearer when we compare the data. We observed differences between the perception of CHWs and the perceptions of nursing staff and physicians also working in PHC. Variation between professions leads us to argue that these professionals are acting under very different material circumstances. Graph 2 shows that, proportionally, twice as many nursing professionals and physicians (66% and 63%, respectively) perceive that they had access to PPE until June 2020. With regards to training, this gap is even wider: while only 13% of CHWs claimed to have undergone training, while 36% of nursing professionals and 30% of physicians made similar claims.

Graph 2.

Comparison of working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Survey online: Effects of coronavírus in health workers work conditions. June 2020.

As argued above, socioeconomic vulnerability and the requirement of proximity to communities presented a complex, and often insalubrious, working environment for CHWs even before COVID-19 [49]. The nature of the pandemic, where physical distance and the avoidance of non-essential contact were seen as important preventive measures, added further vulnerabilities to CHWs. Without PPE, vaccination or adequate training and guidance, they were placing their own health and lives at risk every time they went to work.

4.2. The pandemic reduced the confidence and impacted on the mental health of CHWs

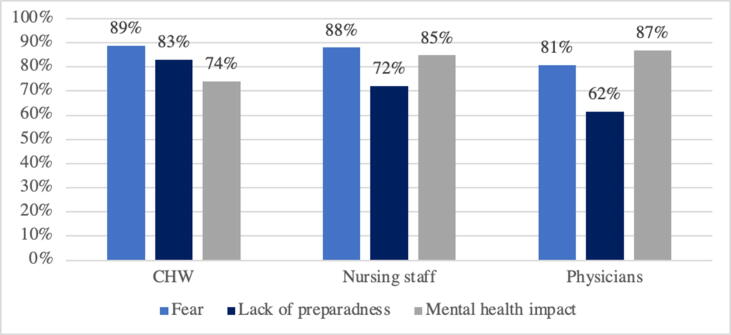

Issues predating the pandemic, related to precariousness of work, hierarchical work dynamics, quality of life, low pay, lack of training and psychological distress were reported by previous studies and demonstrate a critical panorama under which these professionals routinely work [50], [51]. During the COVID-19 crisis, the impact of the pandemic upon Brazil’s CHWs was experienced not only in relation to working condition indicators. Given inadequate PPE provision, the lack of definition about what CHWs should do during the pandemic and how they should reorganize their work, the crisis reduced their ability to feel confident when carrying out their roles.

The only governmental guideline proposing changes in the work of CHWs during the pandemic (“Recommendations for Community Health Workers During the Pandemic”), was confusing and ambiguous. It managed to simultaneously orient CHWs to continue home visits during the pandemic, and told them not to do these visits anymore. This created a scenario of great ambiguity and uncertainty, which resulted in low levels of confidence among CHWs. This lack of confidence is evidenced by reports of fear and lack of preparedness. Graph 3 also shows a high percentage (74%) of CHWs experiencing mental health difficulties as a result of the pandemic.

Graph 3.

Feelings experienced by frontline PHC professionals during the pandemic scenario - June 2020.

Source: Survey online: Effects of coronavírus in health workers work conditions. June 2020 (CHW = 870; Nursing staff = 151; Physicians = 99).

Perceptions of fear and lack of preparedness are also evidenced by the qualitative data. In Facebook group discussions, CHWs express how they felt during the crisis. A prevalent theme is the perception of being alone, without governmental support. As one CHW put it:

“We are living in the middle of the chaos and we are alone. The government wants us to go to the streets in their name, but they do not care about us. They just want to be re-elected. But we are dying. People are dying. And they [the authorities] don’t care. (CHW1)”

Other studies have shown that the fear CHWs experience in relation to COVID-19 is related to feeling or being prepared, and to receiving support from the federal government. The feeling of preparedness – or, in this case, a lack thereof - was associated with poor material working conditions, such as non-existent PPE, inadequate guidance from managers and support from superiors and the federal government [52]. Faced with precariousness in their job security, CHWs felt pressured to continue their work even when perceiving themselves at great risk. Very insecure working conditions and a scenario of uncertainty meant that CHWs were approaching their work without confidence in their role and terrified of becoming infected. This placed a great strain in their personal life, as reported by one CHW:

“I fear going back home and contaminating my family. I asked my daughter to leave home and stay with her father. I have not seen her for many weeks because I am exposed to risks and don’t want to put anyone else at risk. (CHW4)”

Claiming that “nobody wants to be a dead hero” (CHW5) at a Facebook group post, one CHW aptly summarized the feeling of disaffection among many CHWs, who were routinely celebrated as essential by policymakers and the public, while being denied the means to conduct their work safely and with confidence.

4.3. The pandemic impacted upon interactions between CHW and citizens

CHWs reported that the pandemic impacted upon their relationships with their patients and their community. Data from the survey shows that 93,3% of CHW participants think that the pandemic affected the way they interact with citizens. The main changes are: new practices for interaction while keeping physical distance (50,5%); new hygiene habits and work protocols (20,9%); fear and distrust (12,6%); use of PPE (4,5%); and more solidarity and information sharing with users (2,3%).

Bolsonaro’s denialist agenda, which saw the pandemic mainly as a challenge to his own popularity and reelection hopes, increased the challenges to the performance of CHWs. It led to a politicization of the pandemic, which in turn resulted in increasingly polarized and extreme opinions among the population. This, adding to the need for physical distance and masks, created a hostile scenario for CHWs to work, as reported by one CHW: “My questions about the amount of PPE that they made available was seen as something wrong by the supervisor and coordinator. For this reason, I was targeted for criticism and discussions and threats to withdraw from the current team (CHW6)”.

Under this context, data from the survey and from the facebook groups suggest that CHW may be losing part of their legitimacy, as citizens do not trust them as they did before the pandemic. Moreover, CHWs also mention that the crisis made citizens feel distrust towards, and fear of, CHWs, often perceived as possible vectors of the disease. One example is the following statement from the Facebook group:

“The citizens fear me as I fear them. They don’t want to be infected by me and I am afraid I can infect myself. We cannot efficiently perform our work this way. Our performance is very superficial, we cannot get into the houses, we cannot have the same way of working, we are without guidance and materials to develop our jobs. (CHW3)”

4.4. The pandemic affected the power dynamics in PHC teams

The pandemic brought about changes in the working practices of CHWs [53] as they could not do home visits and other collective activities and became responsible for some activities of telemedicine. These changes affected the power dynamics in PHC teams. As suggested above, it reinforced inequalities between health professionals in what regards working conditions and feelings of confidence and preparedness. Second, the pandemic changed how teams work and the dynamics of delivery of services. For example, in many municipalities PHC teams are not conducting face-to-face meetings anymore. Given the central importance of weekly team meetings for CHWs to be heard, this results in the weakening of the voice of CHWs in collective decisions and in the implementation of policies. As one CHW mentioned:

“during the pandemic the teams are not meeting anymore and CHWs do not have the space to make their claims and participate in the decisions”. (CHW5)

The pandemic also exacerbated previous problems of hierarchical relations in ESF teams, and situations of moral harassment. Data from the survey suggests that 28% of CHWs feel that the pandemic led to an increase in moral harassment in the workplace. Some testimonials supported this: “We cannot complain about anything. If we do it, we will receive veiled punishments.” (CHW8)

Finally, the uncertainties and coordination problems in the pandemic response made the role of CHW seem less important for other health professionals, and as a result CHWs were even less valued in the context of the team. CHWs, already widely considered as the “weakest link” in PHC teams because of their lack of specialized training and socioeconomic background [27], [11], are further marginalized with the lack of clarity about their role and their reduced confidence. CHWs reported that:

“I never imagined that our work would be so devalued as during the pandemic. They [the government] treat us as if we are not even necessary”. (CHW13)

4.5. The role of CHW in the health system is endangered

The pandemic is also endangering the very role of CHWs in PHC provision, as the nature of CHW activity relies on interactions with citizens, mainly conducted inside homes. At a time when their role in the health system is being questioned, with ongoing changes in PHC policy which aim to reduce their role [42], the inability on the part of CHWs to fulfill their function during the pandemic adds further risks to the profession. Thus, in addition to the problems caused by the lack of confidence of CHWs in what pertains to carrying out their work, and the distrust of the population which often sees CHWs as possible disease spreaders, the pandemic can also contribute to a broader distrust of the CHW as a profession, which in turn endangers the continuity of their post-pandemic work.

The perception among CHWs of a growing risk to their profession has spurred collective mobilization aimed at helping to legitimize their work. Regional-level unions and a national confederation of unions have initiated a campaign enjoining CHWs to keep doing their work so as to prove their importance to the SUS. These testimonials reflect this situation:

“This is the time for us to prove that our work is fundamental. If we are not in this frontline, we will be showing the government that they do not need us. And our struggle will be weakened”. (CHW18)

4.6. The pandemic affected the services provided to citizens

Poor working conditions of CHWs inside communities generate constraints in assistance and difficulties in implementing primary care policies [49]. As a result of all the effects described above, the pandemic has also impacted upon the provision of services, mainly in regard to vulnerable citizens who most require the public health system and the work of CHWs.

One difficulty often reported by CHWs is how the pandemic has impacted in terms of how they communicate with health system users:

“The home visits were that time of conversation, listening to people’s problems, especially the elderly’s, having a coffee… a good time for them. Now we need to stay outside the houses.” (CHW20)

One of the most important benefits of the work of Brazilian CHWs among vulnerable populations is the myriad intangible impacts of listening and caring for those who are normally neglected and marginalized by public service provision – the poor and elderly, those with chronic patients, the lonely and the mentally ill. Research has also shown that 80% of black, brown and indigenous people in Brazil are reliant upon the public health system, including PHC and the CHW programme [54].

COVID-19 has contributed to a deterioration of care, with severe consequences for vulnerable groups. Comorbidities that are deemed to exacerbate the risk of serious COVID-19 infection, such as higher blood pressures and diabetes, are also more common among these groups [43]. Moreover, it is telling that Brazil is the country with the highest level of maternal deaths linked to COVID-19 [55]. Until July 2020, 77% of worldwide maternal deaths of women infected by COVID-19 were concentrated in Brazil. Most of these deaths are associated with serious failures in care, including the lack of assistance of these women in PHC – a role traditionally performed by CHWs. Other studies show a higher rate of COVID-19 fatality cases among black and brown women (17%) if compared with white women (8,9%) [56].

The higher rates of infection of COVID-19 among vulnerable groups can in part be explained by lack of sanitation, access to water, the impossibility to isolate infected family members and other precarious and insalubrious living conditions. It is also plausible to argue that the inability of CHWs to perform their traditional health education and promotion role, and their inability to interact closely with vulnerable users, has contributed to the uncontrollable increase of COVID-19 contamination in poor areas of Brazil.

5. Conclusion

The impact of the pandemic among Brazilian health professionals has been profound. This paper has drawn on first-hand accounts collected during the pandemic to reveal important dimensions of its impact. Our argument focused on CHWs, an oft-neglected professional category. Our data adds qualitative depth by providing a detailed picture of existing vulnerabilities in this category. Despite the importance of CHWs in Brazilian health care, the lives and work of Brazilian CHWs were, before COVID-19, already traversed by vulnerabilities. These were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The failure of leadership and coordination at the level of the federal government during the pandemic created a scenario of ambiguity and tension around the work of CHWs. This situation of uncertainty undermined the effectiveness of the response. The nature of crises is always one in which a degree of unpredictability is unavoidable. However, research shows that in order to support frontline professionals, it is essential for governments to provide clear and timely guidelines [57]. These guidelines need to be flexible enough so that they can be adjusted as the crisis unfolds, and new facts emerge. In the Brazilian response to COVID-19, the absence of clear decisions on the part of the government to coordinate and guide the work of health professionals endangered the health and safety of CHWs and of the wider population. CHWs are tasked with bringing health teams closer to local dynamics, connecting families to services, and translating policies. CHW perceptions of fear and lack of preparedness thus have concrete consequences on the frontlines of the response, namely in the way CHWs interact with health system users and in their ability to inform, advise and provide care to vulnerable groups. Given that the work of CHWs is predominantly based on face-to-face interactions in the communities, the requirement of physical distance during the pandemic put into question some of the fundamental aspects of the care they provide to citizens.

Our argument revealed important disparities within the health workforce during the pandemic response. When looking at how nurses and physicians were considered in the documents published in the same period, it becomes clear that CHWs were left in a more precarious situation than other health professions. Situations of health emergency entail risks for all health professionals. However, our findings reveal that different types of health professionals in Brazil were affected differently by the pandemic. And those professionals who are already at a disadvantage in normality were hit hardest during the crisis. Furthermore, it is expected that, during a crisis and in a situation of scarce resources, there will be a degree of competition between professionals. Nonetheless, this competition can in some cases exacerbate the disadvantages of some groups. In the case of Brazil, competition within the health workforce can be seen to reflect existing inequalities in Brazilian society. CHWs, who are overwhelmingly black women, received less recognition, resources and support and were more exposed to work-related vulnerabilities than nursing staff (overwhelmingly white women) and physicians (mostly white men and women). Furthermore, changes in the dynamics and division of labor in PHC teams, brought about by the pandemic, impacted upon the already-fragile balance between different health professions upon which Brazilian PHC rests.

The dire situation experienced by Brazilian CHWs reveals the ongoing struggles of Brazil’s poorest and most vulnerable. More than 70% of the Brazilian population depends on the public health system, and the PHC is the gatekeeper of the system. The access of these groups to the health system and the state rely mostly on CHWs, who bridge between communities and institutions [11], [28]. The fragility of PHC thus has critical and direct consequences in exacerbating inequalities in access to healthcare and other services. By rendering CHWs more vulnerable, by calling into question the nature of their work and their standing vis à vis other health professionals, the pandemic has contributed to further distancing vulnerable groups from the state and its policies.

This paper has some limitations. The first one is regarding data collection, considering that this is a convenience sample, with data collected by workers who are engaged and digitally active. The second one is that we do not have the same type of data from the period before the pandemic to make the comparison. These limitations do not allow us to generalize the findings presented here. The third limitation is that we are analyzing one specific context: Brazilian CHWs. Future studies should observe these dynamics in other contexts, where the experience of community health workers may be different from the Brazilian ones.

6. Key messages

Community health workers could be important actors in facing the Covid-19 pandemic. However, they are exposed to important disparities within the health workforce during the pandemic response, which can be seen as a reflection of existing inequalities in Brazilian society.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis about CHWs’ situation during the pandemic reveal that, by rendering CHWs more vulnerable, by calling into question the nature of their work and their standing vis à vis other health professionals, the pandemic has contributed to further distancing vulnerable groups from the state and its policies.

The Covid-19 pandemic led to a deterioration of the working conditions of CHWs, of their relations with other health professionals, and of their ability to carry out their essential work in the public health system.

The dire situation experienced by Brazilian CHWs reveals the ongoing struggles of Brazil’s poorest and most vulnerable.

Ethical approval

The research was approved by the Ethical Committee of Getulio Vargas Foundation, n. 099/2020.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gabriela Lotta: Conceptualization. João Nunes: Conceptualization. Michelle Fernandez: Conceptualization. Marcela Garcia Correa: Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank to Giordano Magri and Claudio Mello who helped in data collection. Authors thank to FGV for funding the research.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpopen.2021.100065.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Iyengar K.P., Ish P., Upadhyaya G.K., Malhotra N., Vaishya R., Jain V.K. COVID-19 and mortality in doctors. DiabetesMetab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(6):1743–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson D, Anders R, Padula W V, Daly J, Davidson PM. Vulnerability of nurses and physicians with COVID-19: Monitoring and surveillance needed. J Clin Nurs 2020;29(19–20):3584–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Shaukat N., Ali D.M., Razzak J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(40):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanal P., Devkota N., Dahal M., Paudel K., Joshi D. Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID-19 in a low resource setting: a cross-sectional survey from Nepal. Global Health. 2020;16(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green L., Fateen D., Gupta D., McHale T., Nelson T., Mishori R. Providing women’s health care during COVID-19: Personal and professional challenges faced by health workers. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;151(1):3–6. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alharbi J., Jackson D., Usher K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15-16):2762–2764. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlmann E., Dussault G., Wismar M. Health labour markets and the “human face” of the health workforce: resilience beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(4):1–2. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olaniran A., Smith H., Unkels R., Bar-Zeev S., van den Broek N. Who is a community health worker? – a systematic review of definitions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1272223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartzler A.L., Tuzzio L., Hsu C., Wagner E.H. Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):240–245. doi: 10.1370/afm.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palafox B., Renedo A., Lasco G., Palileo‐Villanueva L., Balabanova D., McKee M. Maintaining population health in low- and middle-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: Why we should be investing in Community Health Workers. Trop Med Int Heal. 2021;26(1):20–22. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotta G., Wenham C., Nunes J., Pimenta D.N. Community health workers reveal COVID-19 disaster in Brazil. The Lancet. 2020;396(10248):365–366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31521-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peretz P.J., Islam N., Matiz L.A. Community Health Workers and Covid-19 — Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):e108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2022641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sham L., Ciccone O., Patel A. The COVID-19 pandemic and Community Health Workers: An opportunity to maintain delivery of care and education for families of children with epilepsy in Zambia. J Glob Heal. 2020;10(2):1–3. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajisegiri W.S., Odusanya O.O., Joshi R. COVID-19 Outbreak Situation in Nigeria and the Need for Effective Engagement of Community Health Workers for Epidemic Response. Glob Biosecurity. 2020;1(4):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfield NI, Crittenden R, Fox D, McDonough J et al. COVID-19 Crisis Creates Opportunities for Community-Centered Population Health: Community Health Workers: at the Center. J Ambulat Care Manag 2020;43(3):184–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Haines A., de Barros E.F., Berlin A., Heymann D.L., Harris M.J. National UK programme of community health workers for COVID-19 response. The Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1173–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30735-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valente E.P., Damásio L.C.V.C., Luz L.V., Pereira M.F.S., Lazzerini M. COVID-19 among health workers in Brazil: the silent wave. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):1–3. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotrin P, Moura W, Gambardela-Tkacz CM, Pelloso FC, Santos L dos, Carvalho MD de B, et al. Healthcare Workers in Brazil during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a cross-sectional online survey. Inq J Health Care 2020;57:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bolina A.F., Bomfim E., Lopes-Júnior L.C. Frontline Nursing Care: The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Brazilian Health System. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:1–6. doi: 10.1177/2377960820963771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.-G., Ma W., et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Heal. 2020;5(9):e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hallal P.C. SOS Brazil: science under attack. Lancet. 2021;397(10272):373–374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferigato S., Fernandez M., Amorim M., Ambrogi I., Fernandes L.M.M., Pacheco R. The Brazilian Government's mistakes in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1636. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.do Rosário-Costa N, et al. Community Health Workers’ Attitudes, Practices and Perceptions Towards the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazilian Low-income Communities. IOSPress. 2021:3–11. Available in: https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor205000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Health Ministry. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial - Doença pelo Coronavírus COVID-19. Secretaria de Vigilância Sanitária, 2020; October 23. Available in: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/media/pdf/2020/outubro/29/boletim_epidemiologico_covid_37_alterado2-compactado.pdf.

- 25.Health Ministry. Política Nacional da Atenção Básica. Brasília; 2012.

- 26.Lotta G.S., Marques E.C. How social networks affect policy implementation: An analysis of street-level bureaucrats' performance regarding a health policy. Social & Policy Administration. 2020;54(3):345–360. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger MGM, Wenham C, Nacif Pimenta D, Nkya TE, Schall B, Nunes AC, et al. How do community health workers institutionalise: An analysis of Brazil’s CHW programme. Global Publ Heal. 2021;1-18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nunes J., Lotta G. Discretion, power and the reproduction of inequality in health policy implementation: Practices, discursive styles and classifications of Brazil’s community health workers. Soc Sci Med. 2019;242(112551):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro M.C., Massuda A., Almeida G., Menezes-Filho N.A., Andrade M.V., de Souza Noronha K.V.M., et al. Brazil's unified health system: the first 30 years and prospects for the future. The Lancet. 2019;394(10195):345–356. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massuda A., Hone T., Leles F.A.G., de Castro M.C., Atun R. The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis and resilience. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3(4):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simas PRP, Pinto IC de M. Trabalho em saúde: retrato dos agentes comunitários de saúde da região Nordeste do Brasil. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22(6):1865–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Morosini Márcia Valéria, Corbo Anamaria D'Andrea, Guimarães Cátia Correa. O agente comunitário de saúde no âmbito das políticas voltadas para a atenção básica: concepções do trabalho e da formação profissional. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde. 2007;5(2):287–310. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morosini M. EPSJV; Rio de Janeiro: 2010. Educação e trabalho em disputa no SUS: a política de formação dos agentes comunitários de saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alonso CM do C, Béguin PD, Duarte FJDCM. Work of community health agents in the Family Health Strategy: meta-synthesis. Rev Saud Pub 2018; 52(14):1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Martines W.R.V. Chaves EC Vulnerabilidad y sufrimiento en el trabajo del agente comunitario de salud en el Programa Salud de la Familia. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2007;41(3):426–433. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342007000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Telles SH, Pimenta AMC. Burnout syndrome in community health agents and coping strategies. Saúde e Soc 2009;18(3):467–78.

- 37.Hirata H. O trabalho de cuidado. Sur: Revis Inter de Dir Humanos. 2016;13(24):53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbosa Regina Helena Simões, Menezes Clarissa Alves Fernandes de, David Helena Maria Scherlowski Leal, Bornstein Vera Joana. Gênero e trabalho em saúde: Um olhar crítico sobre o trabalho de agentes comunitárias/os de saúde. Interface Commun Heal Educ. 2012;16(42):751–765. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milanezi J, Gusmão HN, Souza CJ, Bertolozzi, TB, Lotta G, Fernandez M, Corrêa MG et al. Mulheres negras na pandemia: o caso de Agentes Comunitárias de Saúde (ACS). Informativos Desigualdades Raciais e Covid-19, AFRO CEBRAP, São Paulo. 2020;5. Available in: https://cebrap.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Informativo-5-Mulheres-negras-na-pandemia-o-caso-de-Agentes-Comunita%CC%81rias-de-Sau%CC%81de-ACS-.pdf.

- 40.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Recomendações para adequação das ações dos agentes comunitários de saúde frente à atual situação epidemiológica referente ao Covid-19. 2020. Available in: http://www.saudedafamilia.org/coronavirus/informes_notas_oficios/recomendacoes_adequacao_acs_versao-001.pdf [accessed: June 19, 2020].

- 41.Bryman A. Oxford University Press; London UK: 2016. Social research methods. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare workers' emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clin Med Res 2016;14(1):7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Lino M, Lanzoni GM de M, Albuquerque G de, Schveitzer M. Perfil socioeconômico, demográfico e de trabalho dos Agentes Comunitários de Saúde. Cogitare Enferm 2012;17(1):57–64.

- 44.Scheffer M, Cassenote A, Guilloux AGA, Miotto BA, Mainardiet GM et al. Demografia Médica no Brasil. FMUSP, CFM, Cremesp. São Paulo, SP: FMUSP, CFM, Cremesp; 2020. Available in: http://www.epsjv.fiocruz.br/sites/default/files/files/DemografiaMedica2018%20(3).pdf.

- 45.Fiocruz. Pesquisa Perfil da Enfermagem no Brasil. COFEN. São Paulo, SP; 2017. Available in: http://biblioteca.cofen.gov.br/perfil-da-enfermagem-no-brasil/.

- 46.Cofen. Perfil da enfermagem no Brasil, 2019. Available in: http://www.cofen.gov.br/perfilenfermagem/index.html.

- 47.Scheffer M. Demografia médica no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2020.

- 48.Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Ed. 70; 1994.

- 49.Jatobá Alessandro, Bellas Hugo Cesar, Bulhões Bárbara, Koster Isabella, Arcuri Rodrigo, de Carvalho Paulo Victor R. Assessing community health workers’ conditions for delivering care to patients in low-income communities. Appl Ergon. 2020;82:102944. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunes João. The everyday political economy of health: community health workers and the response to the 2015 Zika outbreak in Brazil. Review Intern Pol Econ. 2020;27(1):146–166. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1625800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morosini M.V.G.C., Fonseca A.F., de Lima L.D. Política Nacional de Atenção Básica 2017: retrocessos e riscos para o Sistema Único de Saúde. Saúde em Debate. 2018;42(116):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandez M., Lotta G. How Community Health Workers are facing COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil: Personal Feelings, Access to Resources and Working Process. Arch Fam Med Gen Pract. 2020;5(1):115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernandez M., Lotta G., Corrêa M. Desafios para a Atenção Primária à Saúde no Brasil: uma análise do trabalho das agentes comunitárias de saúde durante a pandemia de Covid-19. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde. 2021;19 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pires L.N., Carvalho L., Rawet E. Multidimensional Inequality and COVID-19 in Brazil. Econ Public Policy Br Arch. 2020;80(315):33–58. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takemoto Maira L.S., Menezes Mariane de O., Andreucci Carla B., Nakamura‐Pereira Marcos, Amorim Melania M.R., Katz Leila, et al. The tragedy of COVID-19 in Brazil: 124 maternal deaths and counting. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;151(1):154–156. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darney P.D., Nakamura-Pereira M., Regan L., Serur F., Thapa K. Maternal Mortality in the United States Compared With Ethiopia, Nepal, Brazil, and the United Kingdom: Contrasts in Reproductive Health Policies. Obstetrics Gynecol. 2020;135(6):1362–1366. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Møller MØ. The dilemma between self-protection and service provision under Danish Covid-19 guidelines: a comparison of public servants’ experiences in the pandemic frontline. J Comp Policy Anal: Res Practice 2021;23(1): 95-108.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.