Abstract

Brain abscess is a very rare condition but has a significant mortality rate. The three main routes of inoculation are trauma, contiguous focus, and the hematogenous route. The odontogenic focus is infrequent and is usually a diagnosis of exclusion. This paper presents a brain abscess case proven to be of dental origin, caused by Actinomyces meyeri and Fusobacterium nucleatum. This case highlights the risk underlying untreated dental disease and why oral infectious foci removal and good oral health are essential in primary care.

1. Introduction

Brain abscess is the most common type of focal infectious neurologic lesion and is defined as a localized area of suppuration which develops within the brain parenchyma [1–5] after inoculation with a pathogen [6].

In most literature, its prevalence is reported as 1 : 100.000 [1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8], which usually occurs more frequently in men [5, 7, 8] under 60 years of age [5].

Even with modern antibiotic treatment, it is still considered a life-threatening infection [2–6, 8, 9] with a mortality rate ranging from 10% [2, 4, 8] to 24% [3, 6].

There are three inoculation pathways from which a brain abscess can develop [2–6, 9–13]: direct contamination through a surgical event (10%–20% of cases) [6, 12], hematogenous spread (20%–30% of cases) [12], and spread from a contiguous focus (20%–40% of cases) [6, 12].

Cerebral space lesion presents roughly the same signs and symptoms: headache (first and most common) [5, 8, 14–16] and nausea/vomiting [9] as a result of increased intracranial pressure [2, 8, 15, 16]. The poorer the mental status of the patient upon admission, the poorer the long-term outcome will be [9], defining this as a major prognosis indicator [8].

Odontogenic infections are a rare but known possible cause of brain abscesses [4, 5, 8, 13, 17, 18] via hematogenous spread [14]. Recent dental treatment, poor oral hygiene, and diabetes are also know risk factors for brain abscess development due to the transient bacteremia associated with compromised immunity [5, 14]. Periodontitis, defined as an infection of tooth-supporting tissues, is characterised by an inflamed and necrotic area with the destruction of the alveolar bone [19, 20]. This condition is an obvious starting point of bacteremia and metastatic spread [2, 5], due to the great heterogeneity and load of microorganisms. Other potential odontogenic sources are odontogenic cysts and periapical osteitis [4].

Comparison cultures from brain abscess and oral focus are rarely obtainable [8], thus making this an exclusion diagnosis [4, 8, 12, 18] with supportive evidence often limited to a positive culture for oral flora from drained cerebral suppuration [8, 12]. Negative cultures of abscesses may be due to cultivation failure or previous antibiotic treatment [21], and this can lead to controversy regarding the accurate prevalence of brain abscess of odontogenic origin, with literature numbers ranging from 3% [7] to 30% [12].

Brain abscesses are frequently polymicrobial [3, 5, 8, 11–13], and those with odontogenic origin have Streptococci as the primary isolate [2, 3, 5, 8, 12]. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Actinomyces meyeri are both rare isolates in this context [22, 23].

Among the family of Fusobacteriaceae [22, 24], Fusobacterium nucleatum are Gram-negative anaerobic rod-shaped bacilli [24–26] and the most pathological species of the genera Fusobacterium [22, 27]. They are present in mucomembraneous surfaces such as the oral cavity [28], respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts [24, 26, 27] and are reported to cause periodontal disease [24, 26]. Their embolic characteristics [27] are known to cause 6% of all bacterial brain abscesses [24], which is a rare finding [22, 24, 26].

Actinomyces meyeri belongs to the family of Actinomycetaceae and is an anaerobic, branching-filamentous Gram-positive bacillus [17, 19, 28–34] present in the oral flora and gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts [15, 17, 28–30, 32, 34–36]. Actinomyces meyeri is usually found in the periodontal sulcus [19, 34, 37, 38], and while it is considered a low-virulence bacteria in immunocompetent individuals, there are risk factors identified for Actinomyces infection including poor oral hygiene, abusive alcohol intake, pulmonary infection, and recent dental treatment [17, 30, 34, 36, 38]. Its infection is usually restricted to the cervicofacial region, with the central nervous system rarely affected [15, 17, 28, 34, 36, 38–41], accounting for approximately 3% of actinomycosis [33, 35, 42]. Infection by Actinomyces meyeri itself is very rare [28, 30, 35], accounting for only 1% of all Actinomyces spp. involved in human pathogenesis [31, 39].

In 2017, a search was performed for case reports, case series, clinical trials, and reviews published in English in peer-reviewed journals in PubMed, using the MeSH terms actinomyces, actinomycosis, Actinomyces meyeri, brain abscess, cerebral, and/or central nervous system, by Guillamet et al. Only seven case reports were found for brain abscess by Actinomyces meyeri, and only one was also positive for Fusobacterium nucleatum [28, 29].

Early diagnosis with CT scan and appropriate treatment improves not only the mortality rate but the overall prognosis as well [3, 6–9, 16, 43].

The treatment for brain abscess is usually a combination of surgery and long-term antibiotics [2, 4, 8, 10, 12, 13, 20, 21, 23, 24, 28, 29, 31, 33, 37, 43] with oral cavity sanitisation when oral focus is suspected [3, 4, 12, 13].

The following case reports an immunocompromised patient with no recent history of dental treatment, but with several other risk factors for cerebral abscess, who developed a brain abscess. The culture was positive (before any antibiotic treatment) for Fusobacterium nucleatum and Actinomyces meyeri. He was submitted to cerebral drainage and long-term antibiotic treatment, having only mild left crural paresis and left temporal hemianopsia as sequelae.

2. Case Report

A 60-year-old man was transferred from the Centro Hospitalar do Médio Tejo-Hospital de Abrantes due to complaints of headache, barely perceptible speech, and decreased muscle strength in the left hemibody, with a week of onset, associated with partial seizures in the left hemibody. The comorbidities were non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus, medicated glaucoma, treated gastric cancer, smoking, and daily alcohol abuse. The patient reported no regular dental follow-up, presenting only in urgent cases.

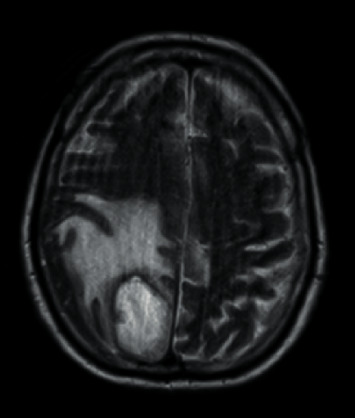

At the latter hospital, the Abdominopelvic Computed Tomography (AP-CT) revealed no significant changes and the Cranioencephalic Computed Tomography (CE-CT) revealed an “apparently intra-axial expansive lesion in the right parasagittal parieto-occipital area, predominantly hypodense, with about 4 cm in diameter, bordered by an extensive halo of perilesional edema” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CE-CT in the latter hospital.

During admission, at the Emergency Department of Hospital de São José, the patient presented a Glasgow Score of 15, left hemibody myoclonus, grade 3 left hemiparesis, and left labial commissure deviation. No other changes in physical examination were sought. Laboratory analysis revealed erythropenia of 3.29 × 1012/L (normal: 4.4–5.9 × 1012/L); 34.9% hematocrit (normal: 40–50%); neutrophilia of 77.9% (normal: 40–75%); lymphopenia of 12.9% (normal: 15–45%); hyperglycemia of 143 mg/dL (normal: 60–100 mg/dL); uremia of 16 mg/dL (normal: 18–55 mg/dL); and hyponatraemia of 134 mEq/L (normal: 136–145 mEq/L).

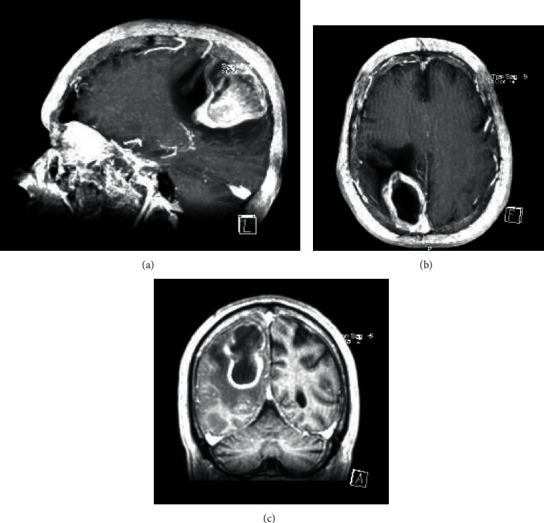

Taking into consideration the findings of CE-CT, the most likely diagnoses were neoplasm or infection of the Central Nervous System (CNS), so the patient was transferred to the Neurosurgery Department. A cranioencephalic Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CE-MRI) was also performed, which revealed a “right posterior parietal corticosubcortical lesion, with diffusion restriction, annular enhancement after gadolinium, and extensive perilesional edema, being more in favor of an abscessed collection hypothesis” (Figures 2(a)–2(c)).

Figure 2.

CE-MRI in Hospital São José.

The patient was submitted to surgical drainage under general anesthesia, with the purulent content sent to microbiology analysis and initiation of empirical antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone 2g every 12 hours and clindamycin 600 mg every 6 hours. The postoperative period in the Postanesthetic Intensive Care Unit (PICU) was uneventful, and the patient was transferred back to the Neurosurgery Department after 2 days.

At the microbiology department, the pus aspirate sample was cultured aerobically and anaerobically, the latter being performed through placing an inoculated medium into an anaerobic environment jar. The sample was initially placed in a liquid anaerobic medium (Brain Heart Infusion broth) enriched with peptone, glucose, sodium chloride, and disodium phosphate. Three days later, a colony growth measured by turbidity was verified. Then, a subculture was performed in different types of growth solid medium (blood agar, chocolate agar, MacConckey agar, and CHROMagar MRSA). A direct identification with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-light mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) from the anaerobic subculture colonies was performed, and the result was Actinomyces meyeri and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Due to cost-effectiveness issues, antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobes is not carried out in our microbiology department, and the antibiotic therapy is established according to the published surveillance data of our hospital.

At this point, the stomatology evaluation and infectious diseases collaboration was requested, which concluded that the two microorganisms had oropharyngeal origin, and thus, an adjustment of antibiotic coverage was recommended. The patient started penicillin 24 MUI a day and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours, intravenously for 3 weeks and orally thereafter.

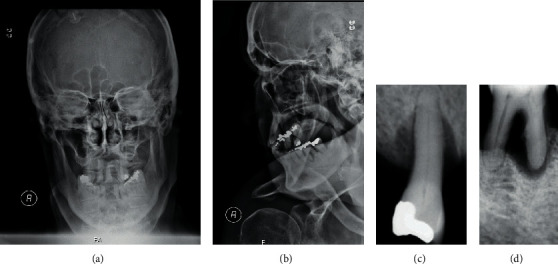

The patient was observed at the Stomatology Department of Hospital de São José, where several oral septic foci were identified that could justify the necessary bacteremia for hematogenous inoculation. Oral physical examination identified partial edentulism in both dental arches; poor oral hygiene with the presence of bacterial plaque and calculus; and generalized advanced chronic periodontitis with active periodontal pockets (Figures 3(a)–3(d)). No oral culture was performed due to our experience with failure to achieve conclusive bacterial cultures under a polymicrobial oral flora with previous antibiotic treatments. The treatment plan consisted of systematic elimination of oral septic foci, teaching and motivation for oral hygiene, and the investigation of possible immune deficits. This evaluation showed no immunodeficiency.

Figure 3.

Face X-ray and intraoral X-ray.

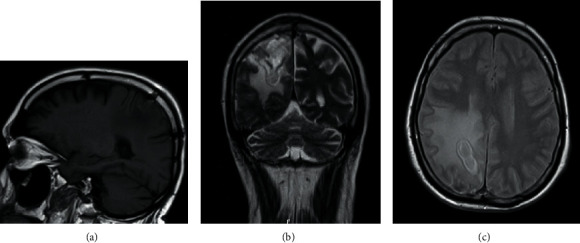

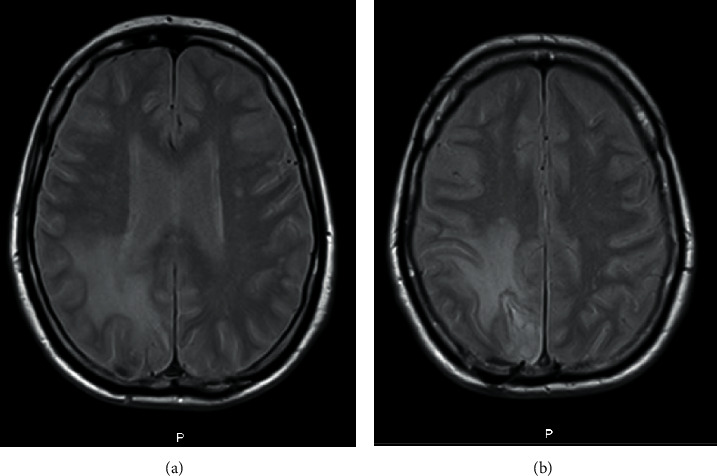

During hospitalisation, the patient underwent two control Cranioencephalic Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CE-MRI) (the first one at 12 hospitalisation day (Figures 4(a)–4(c)) and the second one at 28 hospitalisation day (Figures 5(a) and 5(b))) which revealed downsizing of the abscessed collection and perilesional edema. After one month of hospitalisation, the patient was transferred to the residence area hospital, with the requirement to complete the antibiotic therapy cycle, perform physiotherapy treatments, and repeat the CE-MRI. The patient was left with only residual neurological deficits as a sequel.

Figure 4.

CE-MRI at 12 hospitalisation day.

Figure 5.

CE-MRI at 28 hospitalisation day.

3. Discussion

Brain abscess is a rare but serious condition [2, 3, 5, 7, 22, 26, 42]. The diagnosis is not always straightforward, but CT and MRI are a helpful tool for the clinicians [2, 3, 7, 17, 40]. Although there were no comparison cultures between the patient's oral flora and brain abscess, the fact that all other causes were excluded (including any recent trauma), combined with the fact that he had advanced, generalized chronic periodontitis and that both isolated species are found in normal oral flora, makes this a case of brain abscess of likely dental origin [13, 17, 19, 24, 26, 29, 31, 42].

The patient has residual neurological deficits and still has regular follow-up.

A literature search for case reports with brain abscess caused by Actinomyces meyeri and Fusobacterium nucleatum returned in very few results, and none were found with these two associated microorganisms [3, 29, 39, 40].

This case emphasises the underestimated risk associated with untreated dental disease. Good oral health and regular dental examinations are crucial in every patient, not only for the widely known reason but also to prevent metastatic infections which could follow any odontogenic chronic infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleague Catarina Ferreira for helping them with the microbiological testing clarification.

Data Availability

No data were used to support this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hobson D. T. G., Imudia A. N., Soto E., Awonuga A. O. Pregnancy complicated by recurrent brain abscess after extraction of an infected tooth. Obstetrics & Gynecology . 2011;118(2):467–470. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31822468d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azenha M. R., Homsi G., Garcia I. R. Multiple brain abscess from dental origin: case report and literature review. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery . 2011;16(4):393–397. doi: 10.1007/s10006-011-0308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mylonas A. I., Tzerbos F. H., Mihalaki M., Rologis D., Boutsikakis I. Cerebral abscess of odontogenic origin. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery . 2007;35(1):63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ewald C., Kuhn S., Kalff R. Pyogenic infections of the central nervous system secondary to dental affections-a report of six cases. Neurosurgical Review . 2006;29(2):163–167. doi: 10.1007/s10143-005-0009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X., Tronstad L., Olsen I. Brain abscesses caused by oral infection. Dental Traumatology . 1999;15(3):95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1999.tb00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto H., Karakida K., Otsuru M., Arai M., Shimoda M. A case of brain abscess extended from deep fascial space infection. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology & Endodontics . 2009;108(3):e21–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clifton T., Kalamchi S. A case of odontogenic brain abscess arising from covert dental sepsis. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England . 2012;94(1):e41–e43. doi: 10.1308/003588412x13171221499667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazow S. K., Izzo S. R., Vazquez D. Do dental infections really cause central nervous system infections? Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America . 2011;23(4):569–578. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyama H., Kito A., Maki H., Hattori K., Noda T., Wada K. Inflammatory index and treatment of brain abscess. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science . 2012;74(3):313–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maraki S., Papadakis I. S., Chronakis E., Panagopoulos D., Vakis A. Aggregatibacter aphrophilus brain abscess secondary to primary tooth extraction: case report and literature review. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection . 2016;49(1):119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahill D. P., Barker F. G., Davis K. R., Kalva S. P., Sahai I., Frosch M. P. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10-2010. A 37-year-old woman with weakness and a mass in the brain. New England Journal of Medicine . 2010;362(14):1326–1333. doi: 10.1056/nejmcpc1000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller A. A., Saldamli B., Stübinger S., et al. Oral bacterial cultures in nontraumatic brain abscesses: results of a first-line study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology & Endodontics . 2009;107(4):469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brook I. Microbiology of intracranial abscesses associated with sinusitis of odontogenic origin. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology . 2006;115(12):917–920. doi: 10.1177/000348940611501211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armendariz-Guezala M., Undabeitia-Huertas J., Samprón-Lebed N., Michan-Mendez M., Ruiz-Diaz I., Úrculo-Bareño E. Absceso cerebral actinomicótico en paciente inmunocompetente. Cirugía y Cirujanos . 2017;85:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai M.-S., Tarn J.-J., Liu K.-S., Chou Y.-L., Shen C.-L. Multiple actinomyces brain abscesses: case report. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience . 2001;8(2):183–186. doi: 10.1054/jocn.1999.0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rémy C., Grand S., Laï E. S., et al. 1H MRS of human brain abscesses in vivo and in vitro. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine . 1995;34(4):508–514. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armendariz-Guezala M., Undabeitia-Huertas J., Samprón-Lebed N., Michan-Mendez M., Ruiz-Diaz I., Úrculo-Bareño E. Absceso cerebral actinomicótico en paciente inmunocompetente. Cirugía Y Cirujanos . 2017;85:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner K. W., Schön R., Schumacher M., Schmelzeisen R., Schulze D. Case report: brain and liver abscesses caused by oral infection with Streptococcus intermedius. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology & Endodontics . 2006;102(4):e21–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vielkind P., Jentsch H., Eschrich K., Rodloff A. C., Stingu C.-S. Prevalence of Actinomyces spp. in patients with chronic periodontitis. International Journal of Medical Microbiology . 2015;305(7):682–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahamat-Langendoen J. C., van Vonderen M. G. A., Engström L. J., Manson W. L., van Winkelhoff A. J., Mooi-Kokenberg E. A. N. M. Brain abscess associated with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: case report and review of literature. Journal of Clinical Periodontology . 2011;38(8):702–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2011.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kastner J., Taudy M., Lisy J., Grabec P., Betka J. Orbital and intracranial complications after acute rhinosinusitis. Rhinology Journal . 2010;48(4):457–461. doi: 10.4193/rhino09.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heckmann J. G., Lang C. J. G., Hartl H., Tomandl B. Multiple brain abscesses caused by Fusobacterium nucleatum treated conservatively. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences . 2003;30(3):266–268. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100002717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen-Wei H. Actinomycosis of the brain. Journal of Neurosurgery . 1985;63(1):131–133. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.1.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hischebeth G. T., Keil V. C., Gentil K., Boström A., Kuchelmeister K., Bekeredjian-Ding I. Rapid brain death caused by a cerebellar abscess with Fusobacterium nucleatum in a young man with drug abuse: a case report. BMC Research Notes . 2014;7(1):p. 353. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagalingam S., Lisgaris M., Rodriguez B., et al. Identification of occult Fusobacterium nucleatum central nervous system infection by use of PCR-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Clinical Microbiology . 2014;52(9):3462–3464. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01082-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kai A., Cooke F., Antoun N., Siddharthan C., Sule O. A rare presentation of ventriculitis and brain abscess caused by Fusobacterium nucleatum. Journal of Medical Microbiology . 2008;57(5):668–671. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahya V., Patel J., Wheeler M., Ketsela G. Fusobacterium nucleatum endocarditis presenting as liver and brain abscesses in an immunocompetent patient. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences . 2015;349(3):284–285. doi: 10.1097/maj.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park H. J., Park K.-H., Kim S.-H., et al. A case of disseminated infection due to Actinomyces meyeri involving lung and brain. Infection & Chemotherapy . 2014;46(4):p. 269. doi: 10.3947/ic.2014.46.4.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vazquez Guillamet L. J., Malinis M. F., Meyer J. P. Emerging role of Actinomyces meyeri in brain abscesses: a case report and literature review. IDCases . 2017;10:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolfe R., Steed L. L., Salgado C., Kilby J. M. Actinomyces meyeri, a common agent of actinomycosis. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences . 2016;352(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haggerty C. J., Tender G. C. Actinomycotic brain abscess and subdural empyema of odontogenic origin: case report and review of the literature. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery . 2012;70(3):e210–e213. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akhaddar A., Elouennass M., Baallal H., Boucetta M. Focal intracranial infections due to actinomyces species in immunocompetent patients: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World Neurosurgery . 2010;74(2-3):346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adeyemi O. A., Gottardi-Littell N., Muro K., Kane K., Flaherty J. P. Multiple brain abscesses due to Actinomyces species. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery . 2008;110(8):847–849. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colmegna I., Rodriguez-Barradas M., Young E. J., Rauch R., Clarridge J. Disseminated actinomyces meyeri infection resembling lung cancer with brain metastases. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences . 2003;326(3):152–155. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200309000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández-Valle T., Guío Carrión L., Galbarriatu Gutiérrez L., Vilar Achabal B. Abscesso cerebral por Actinomyces meyeri. Medicina Clínica . 2014;143(7):331–332. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagiya H., Otsuka F. Actinomyces meyeri meningitis: the need for anaerobic cerebrospinal fluid cultures. Internal Medicine . 2014;53(1):67–71. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuijper E. J., Wiggerts H. O., Jonker G. J., Schaal K. P., Gans J. D. Disseminated actinomycosis due to actinomyces meyeri and actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases . 1992;24(5):667–672. doi: 10.3109/00365549209054655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen K. H., Lin C. H. Brain abscess as an initial presentation in a patient of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia caused by a novel ENG mutation. BMJ Case Reports . 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clancy U., Ronayne A., Prentice M. B., Jackson A. Actinomyces meyeri brain abscess following dental extraction. BMJ Case Reports . 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navas E., Millan J. M.-S., Garcia-Villanueva M., de Blas A. Brain abscess with intracranial gas formation: case report. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 1994;19(1):219–220. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cope V. What the General Practitioner Ought to Know about Human Actinomycosis . London, UK: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy S., Ellenbogen J. M. Seizures, frontal lobe mass, and remote history of periodontal abscess. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine . 2005;129(6):805–806. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-805-sflmar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jamjoom A. B., Jamjoom Z. A. B., Al-Hedaithy S. S. Actinomycotic brain abscess successfully treated by burr hole aspiration and short course antimicrobial therapy. British Journal of Neurosurgery . 1994;8(5):545–550. doi: 10.3109/02688699409002946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used to support this study.