Abstract

COVID-19 is a severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and quarantines have led to significant industrial slowdowns among the world’s major emitters of air pollutants, with resulting decreases to air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions in nations such as China, India and US, deemed to be major sources of global CO2 emissions, as well. However, there are major concerns that these decreases in atmospheric pollution can be hampered as economies are reactivated. Historically, countries have weakened environmental legislations following economic slowdown to encourage renewed economic growth. Such a policy response now will likely have disproportionate impacts on global Indigenous people and marginalized groups within countries, who have already faced disproportionate impacts from COVID-19 and environmental pollution. Our “new normal” remain nimble enough to allow us to fine-tune our interventions, research tools and solutions-oriented research to quickly enough to stay ahead of the pandemic trajectory in the face of air pollution and climate change. Societal and behavioral changes to reduce these anthropogenic cumulative stressors should be advocated, while prioritizing the public health of marginalized groups around the world, promoting new approaches to champion environmental health along with educational programs addressed to the population. Bold government decisions can restart economies while pre-empting future inequities and committing to environmental protection in an era of COVID-19 and global change.

Keywords: COVID-19, Atmospheric pollution, CO2 emissions, Pollutant management, Climate change mitigation, Solutions-oriented research, Environmental and justice, Indigenous people

1. Introduction: COVID-19 impacts on atmospheric pollution

The response to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic led to massive lockdowns and quarantines, as well as slowdowns of human activity patterns, causing economy and industrial shutdowns and closures, with the aim to halt the spread of the virus worldwide, mainly in highly populated nations such as China, India, and United States. As a result of these events, The COVID-19 pandemic and air quality have become intertwined as quarantines, home isolation, and less land and air traffic have likely improved the ambient air quality in Europe, China, India and United States (Bauwens et al., 2020, Barré et al., 2021, Biswal et al., 2021, Chauhan and Singh, 2020, Gkatzelis et al., 2021, NASA, 2020a, NASA, 2020b, Putaud et al., 2021, Ranjan et al., 2020, Singh et al., 2020, Shi and Brasseur, 2020), the world’s largest current emitters of air pollution (Afshari, 2020, McGrath, 2020, Venter et al., 2020). Following the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic, important consideration has reasonably been allocated on the relationship between COVID-19 and atmospheric pollution or/and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, the main greenhouse gas driving climate change, by some government agencies such as NASA, NOAA, and the European Space Agency (ESA). This should be a scientific issue of pressed importance and a research front of higher priority in academia and non-government organizations.

In fact, air pollution substantially declined in the countries aforementioned, as detected by the NASA-Earth Observatory and ESA satellites’ data during the COVID-19 pandemic (NASA, 2020a, NASA, 2020b). Significant decreases in airborne nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and aerosols (particulate matter: PM2.5 or PM10) over China (Bauwens et al., 2020, Chen et al., 2020, Shi and Brasseur, 2020, NASA, 2020a) and in India (Biswal et al., 2021, Ranjan et al., 2020, Singh et al., 2020, NASA, 2020a) were observed, while reduction in carbon monoxide (CO) and CO2 emissions has been reported in New York, NY (McGrath, 2020).

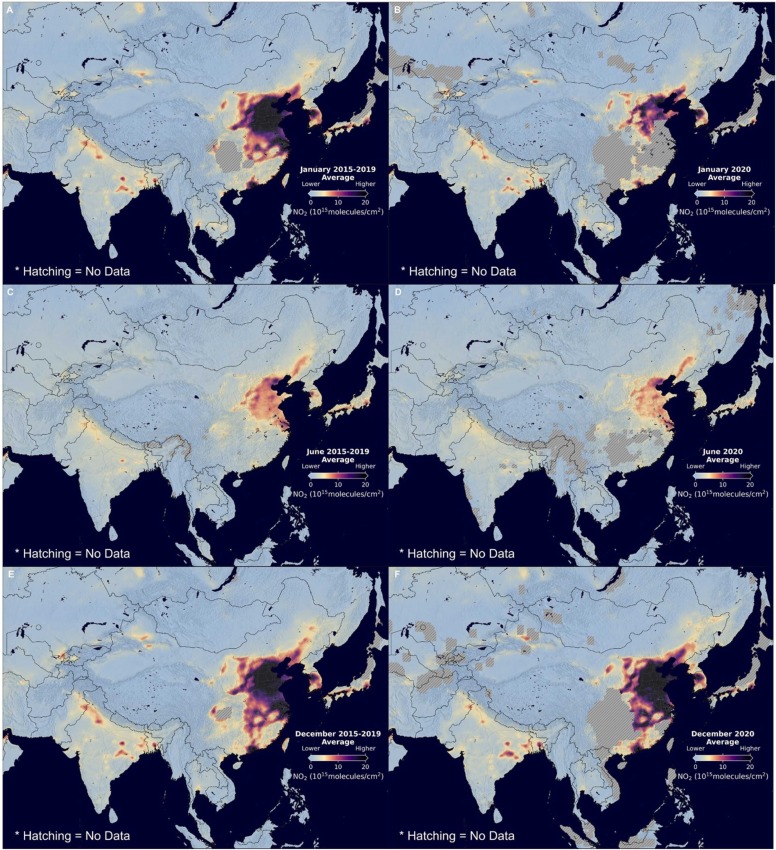

In China, the mean tropospheric density of NO2 (molecules/cm2) has significantly dropped in early and mid-2020 as seen in Fig. 1. When comparing the NO2 -tropospheric density on January 2020 (Fig. 1a,b) versus June 2020 (Fig. 1c,d), a significant reduction (>50%) was observed, which is also evident when contrasting the 2015–2019 average period for January to the average period 2015–2019 in June 2020 (Fig. 1a). At the fine-scale level, for instance, the NO2 concentrations measured on February 10–25, 2020 (during the quarantine) compared to those observed on January 1–20, 2020 (before the quarantine) showed a significant decline in NO2 concentrations in eastern and central China (Fig. S1, Supplementary information).

Fig. 1.

Satellite-derived estimates for tropospheric column density of NO2 (molecules/cm2) over the Asian continent, mainly depicting India and China. Data are shown as the average baseline over the 2015–2019 period for January (A), June (C) and December (E) compared to the 2020 average for January (B), June (D) and December (F), respectively.

Images and data retrieved from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Goddard Space Flight Center: AURA OMI average tropospheric NO2 maps (https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/no2/no2_index.html); and regional NO2 maps (https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/no2/regionals.html: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/no2/pix/regionals/Asia/Asia_2020.html; Lamsal et al., 2021).

Excluding the air pollution “holiday effect” resulting from the Chinese New Year, the decrease of NO2 concentration was 10–30% lower in China relative to the average concentration reported in previous years (2005–2019) at that time period (NASA, 2020a). Conversely, the NO2 levels commenced to rebounding from late April to early May 2020; but mainly in December 2020 as the lockdowns in this nation ceased (Fig. 1e,f).

Comparably, NO2 levels along the northeastern coast of United States significantly plummeted in average by 30% across this region in March 2020 relative to the NO2 mean concentrations (molecules/cm2) of the 2015–2019 period (Fig. S2). Compared to the NO2 average density levels over the 2015–2019 period for January and the levels in January 2020 ( Fig. 2a,b), a reduction of ~50% was projected during June 2020 (Fig. 2c,d). Similar to the NO2 density pattern observed in China, NO2 levels commenced to rebound by December 2020 (Fig. 2e,f). NO2 is an air pollutant primarily emitted from burning fossil fuels (e.g., diesel, gasoline, coal) and can presumably be an indicator linked to fossil fuels’ reductions both in the main polluting countries in Asia (i.e., India and China) and North America, i.e., United States (Bauwens et al., 2020, Gkatzelis et al., 2021).

Fig. 2.

Satellite-derived estimates for tropospheric column density of NO2 (molecules/cm2) over North America, with particular emphasis on the northeastern coast of United States (US). Data are shown as the average baseline over the 2015–2019 period for January (A), June (C) and December (E) compared to the 2020 average for January (B), June (D) and December (F), respectively.

Images and data retrieved from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Goddard Space Flight Center: AURA OMI average tropospheric NO2 maps (https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/no2/no2_index.html); and regional NO2 maps (https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/no2/regionals.html: https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/no2/pix/regionals/NorthAmerica/NorthAmerica_2020.html; Lamsal et al., 2021).

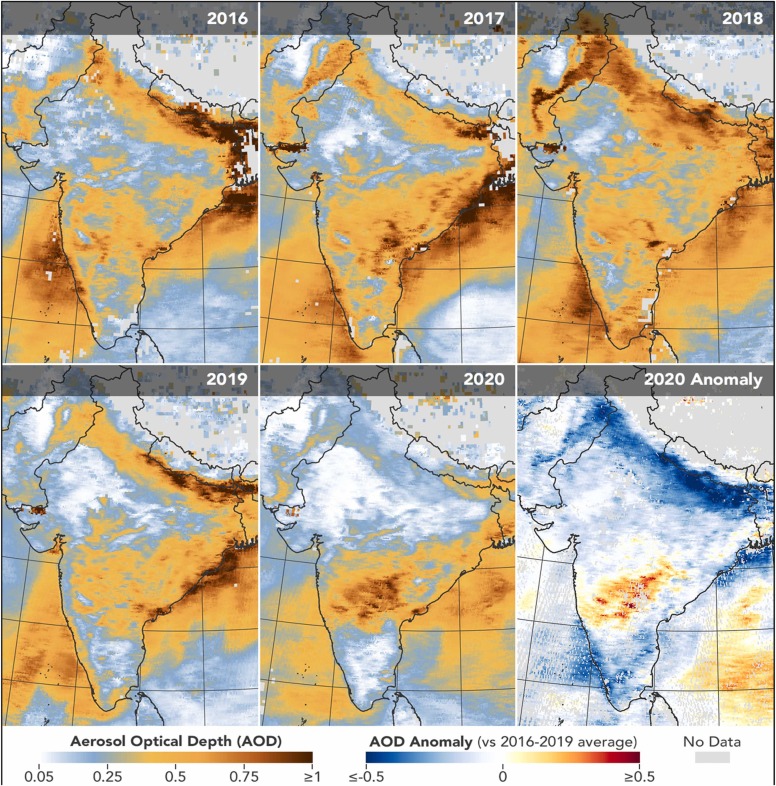

The reduction in the levels of NO2 was not the only case of air pollution changes. Airborne particles dramatically plummeted over India from 2016 to 2020 ( Fig. 3), considering the March 31-April 5 period of each year, as measured by the aerosol optical depth (AOD), i.e., a satellite measurement of aerosols optical thickness to measure how visible and infrared light is absorbed or reflected by airborne particles as it travels through the atmosphere (NASA, 2020b). As illustrated in Fig. 3, the AOD was basically 0.1 or relatively close to 0.05 (clean conditions) in most of India’s territory as shown by the 2020 anomaly, i.e., comparisons of AOD values in 2020 relative to the AOD average values for 2016–2019 (NASA, 2020b). The COVID-19 lockdown in India had an indeed an effect on atmospheric pollution in this country.

Fig. 3.

Aerosol optical depth (AOD) measurements over India from 2016 to 2020 during the same March 31 to April 5 period for each year, and the AOD anomaly in 2020 (i.e., AOD in 2020 relative to the AOD average for 2016–2019). An optical depth, or thickness of 0.05 to < 0.1 (palest white to light blue) over the entire atmospheric vertical column is considered clean (“crystal clear sky”) with maximum visibility, whiles a value ≥ 1 (reddish brown) indicates very hazy conditions. The data were retrieved by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS: https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Image Credit: NASA’s Earth Observatory https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/146596/airborne-particle-levels-plummet-in-northern-india.(For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In the United States, researchers from Columbia University (CUNY Next Generation Environmental Sensor Lab-NGENS Observatory) conducted air quality monitoring research by measuring the composition and changes of urban gases, including CO2, methane (CH4) and carbon monoxide (CO), in New York (McGrath, 2020). The preliminary data indicated that CO and CO2 emissions dropped by ~50% and 10–35% due to reduced vehicles’ traffic during the COVID-19 emergency in New York during the COVID-19 shutdown (McGrath, 2020). Conversely, the global atmospheric CO2 concentrations have not yet plummeted as shown by the monthly mean CO2 measurements (i.e., 414.50 ppm in March 2020 relative to 411.97 ppm in March 2019) reported at Hawaii’s Mauna Loa Observatory (NOAA, 2020a) and the global monthly mean recorded over marine surface sites by the NOAA-Global Monitoring Division (NOAA, 2020b). Despite the global decline of many fossil fuel/carbon burning-activities in urban and industrial areas due to COVID-19, changes in CO2 emissions are not evident since CO2 levels are influenced by the variability of plant – soil carbon cycles (i.e., bio-geochemical cycling) in tandem with the nature of the carbon budget, i.e., atmospheric CO2 concentrations will continue to increase unless annual emissions are set to net-zero (Ehlert and Zickfeld, 2017, Evans, 2020, Le Quéré et al., 2020, Matthews et al., 2017). However, CO2 emission changes are expected as the year 2020 evolves (Evans, 2020, NOAA, 2020a, NOAA, 2020b).

For instance, a drop equivalent to 5.5% of 2019-global total emissions has been projected in 2020 (Evans, 2020), while a more concerted assessment, considering COVID-19 forced confinement, projected an annual CO2 emission reduction by 4% if prepandemic conditions return by mid-June 2020 or by to 7% if some restrictions remain worldwide until the end of 2020 (Le Quéré et al., 2020). However, the global emissions of CO2 must drop by 7.6% annually (Evans, 2020, UNEP, 2019) in order to do not exceed the 1.5 °C global temperature above pre-industrial levels as this is the threshold indicating a temperature limit within the most dangerous climate threats (IPCC, 2018, Le Quéré et al., 2020).

Nonetheless, caution should be considered for the apparent reduction and plausible mitigation in air pollution observed at the time of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic as questions remains on whether the changes in air pollution were actually related to lockdown measures without taking into account the temporal and seasonal variations in emissions and meteorology (Barré et al., 2021, Putaud et al., 2021). Thus, the importance and influence of temporal weather variability in influencing air quality at the time of such estimates and between the baseline reference and lockdown periods is of paramount (Barré et al., 2021) to disentangling meteorological and emission variability when interpreting the emission trends over time.

In the light of these data and observations, questions linger as to whether the global lockdowns and economic slowdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic can have a lasting impact to reducing atmospheric pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions with implications for the public health of marginalized societies, equity, and environmental protection during the post-COVID-19 recovery era.

2. Post COVID-19 environmental policy and pollutant management implications

Though the air pollutants and GHG emissions have been significantly reduced from the direct effects of national quarantines, these reductions may be extremely short lived. The second order effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its shutdown may lead to weakened environmental legislation in the world’s top emitters (which happen to be some of the world’s largest economies) in order to accelerate economic growth. Measures to curtail environmental legislation can be long-lasting and offset any pollution reductions that occurred during lockdown. For example, the United States has rolled back environmental regulations and is interested in stimulating the fossil fuel industry (Rosenbloom and Markard, 2020). For example, major oil exporting countries in North America as well as emerging economies have locked-in further support for fossil-fuel industries, providing subsidies and bailouts for these industries (Quitzow et al., 2021), prompting a stimulus spending that will negatively impact the environment, as highlighted by the World Resource Institute (Dagnet and Jaeger, 2020). Indeed, in an analysis of the stimulus spending across 18 nations, 14 were founds to have contributed to existing industries that will likely worsen environmental outcomes, including subsidies and deregulation, at much higher rates than funding to “green” infrastructures and industries (Dagnet and Jaeger, 2020; VividEconomics, 2020).

Moreover, based on the new data reported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2021), OECD nations and key partner economies have thus far allocated USD 336 billion to environmentally positive measures within their COVID-19 recovery packages. Nonetheless, this funding allocation is not sufficient to have the transformational effects needed to address environmental crises while building back the economy as it amounts to only 17% of the total sums currently allocated to COVID-19 economic recovery (OECD, 2021).

Reviewing the history of environmental policy changes after economic downturns and recessions shows that many nations (including major emitters like USA, UK, Canada, and Australia) slashed environmental legislation and streamlined environmental impact assessment (EIA) processes, allowing more development projects to proceed without EIA and limiting public involvement and consultation on development projects (Bond et al., 2014). The political and economic pressures to opportunistically de-emphasize environmental legislation and tools have been documented around the world across time (Bond et al., 2020). While there are some calls to emerge from COVID-lockdowns embracing pro-environmental development policies such as calls to affirm “Green Deal” approaches (Rosenbloom and Markard, 2020), historical accounts suggest that post-COVID economic recoveries that are environmentally sustainable are not likely (Bond et al., 2014, Bond et al., 2020).

However, there are cases during this era of stimulus spending that are attempting to seriously address environmental sustainability. Canada and France, for example, have attached environmental conditions to bailing out aviation and automobile manufacturing, and other large employers, while Germany and South Korea have announced aggressive plans for transitioning industries towards low emission, such as in electricity and transportation sectors, and the “Next Generation EU” recovery package includes measures to increase sustainability of agriculture, energy, and transportation (VividEconomics, 2020). Nations not dependent on fossil fuels have also deployed greater fiscal measures to respond to the COVID-19 crisis, allowing them to take up opportunities to diversify their economies (Quitzow et al., 2021). Interest in “net-zero” carbon policies across nations has also increased (with a recent estimate at 61% of nations with net-zero commitments), as these policies promise to use technology to offset emissions from existing industries.

Similarly, many nations are promising to develop nature-based solutions to sequester carbon. Conversely, many of the net-zero policies are vague and only 20% meet minimum quality criteria, and many technologies and offsetting strategies are untested and vague (Black et al., 2021). Similarly, recent research suggests that nature-based solutions offer limited (but important) potential, especially if implemented early and designed well to prevent reversals from being a carbon sink to a carbon source (Girardin et al., 2021). While the current post-COVID recovery plans may be “building back better” compared to past recoveries from recessions, they may not be enough to achieve global sustainability goals.

Post-COVID recovery strategies also have implications for international health and cultural equity considerations. Internationally, some estimates place developing and least developed nations as most vulnerable to climate change impacts, and Indigenous communities in the Arctic as facing some of the largest changes to temperature and precipitation changes (IPCC, 2018). The loss of sea ice from climate change in the Arctic has severe implications to the culture and livelihoods of communities in the Arctic (IPCC, 2018). Environmental pollutants disproportionately affect minority communities and indigenous groups. While pollution is the largest environmental cause of premature death in the world, and low income and middle income nations face the brunt of pollution-associated death, Indigenous people often face some of the worst effects of pollution (Landrigan et al., 2018). For example, Indigenous people face the worst air pollution in Canada, and Indigenous groups face severe environmental (i.e., air, water, and land) pollution risks in other regions of the world where there are conflicts between Indigenous peoples and resource extraction projects, or where they rely on seafood as a major food source (Landrigan et al., 2018). The globally inequitable vaccine rollout may exacerbate health consequences for less developed nations, who have some of the lowest vaccination rates (Asundi et al., 2021) and may face re-emerging air pollutant risks as developed nations recover, on top of the COVID-19 risks they face.

Environmental and social injustice is also prevalent within many countries, including the United States, as racial, inequity and ethnic disparities result in greater exposure to harmful environmental pollutants (Landrigan et al., 2018). While COVID has undoubtedly relaxed some of the exposures of these vulnerable groups to pollutants, a post-COVID recovery that maintains low levels of emissions would dampen these pollution and health inequities without having to suffer a pandemic to achieve it. However, promoting post-COVID recovery strategies that weaken environmental legislation will undoubtedly disproportionately affect vulnerable groups like ethnic minorities, who have also been worse affected by COVID (Liverpool, 2020). Disadvantaged groups within and across countries are simultaneously more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and deaths, because of their remote locations and lack of access to health infrastructures (Patel et al., 2020), Importantly, during the COVID-19 pandemic and through the process of recovery, progress across the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has declined, and some of the gains made before the pandemic have reversed (Mukherjee and Bonin, 2020, United Nations, 2021). Recovery post-pandemic should consider how the SDGs are affected, paying special attention to the central theme of the SDGs – no one left behind.

Thus, improved air quality along with climate change mitigation and adaptation should be urgently implemented and/or continued fostered and implemented by developed and developing nations to lessen the exacerbation of respiratory diseases and spread of pathogenic infections by strengthening public health, ultimately reducing the COVID-19 pandemic severity (Afshari, 2020, IPCC, 2018, WHO, 2016).

3. Lesson and reflections from the global COVID-19 experience

Acute air pollution and climate change are two global anthropogenic stressors negatively affecting human health in the long-term (WHO, 2016, WHO, 2018, Smith et al., 2014). While ambient air pollution by particulate matter (PM2.5) is responsible for an estimated > 4 million deaths per year (Cohen et al., 2017), the COVID-19 pandemic has already claimed the lives of > 5.5 million people out of ~320 million confirmed cases (mortality rate of 2%) in tandem with > 9.6 billion vaccine doses administered at the global level by mid-January 2022, according to the interactive database to track COVID-19 in real time from the John Hopkins University’s Coronavirus Resource Centre (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html; Dong et al., 2020). While it was anticipated and now very well known that air pollution was reduced after the lockdown, air pollutant emissions are rebounding to normal levels once developed and developing nations are gradually returning to normalcy and re-activating their economic activities.

As we write this commentary, the ongoing pandemic with a new, highly infectious and transmissible variants, i.e., the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant (Lopez Bernal et al., 2021, Mallapaty, 2021) and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant (UK Health Security Agency, 2021; WHO, 2021) along with the current reopening of socio-economic and industrial activities in many developed nations will increase not only the virus transmission, but airborne pollutants, counteracting some of the atmospheric pollution and GHG emissions reached during the COVID-19 global lockdown (Le Quéré et al., 2020). Despite the fact that significant reductions in air pollution emissions were detected by the satellite data aforementioned, it is still insufficient to offset climate change’s impacts on public health, biodiversity and oceans. The lesson learned from the COVID-19 effect on atmospheric pollution can serve as a compelling reminder that even if all CO2 or GHG emissions are mitigated and ceased today, nations will still have to proactively implement strategic actions to curtail and eliminate airborne pollution in tandem with climate change solutions to reduce emissions and sequester carbon for years to come.

Marginalized groups around the world living in urban, suburban, rural, and remote areas as well as Indigenous communities from developed and developing countries have common and unique health issues in the face of air –pollution, climate change and COVID-19 (i.e., environmental and health education, food security, hygiene and health prevention measures) and in accessing the environmental protection and health care that they need (e.g., lack of pollution abatement and environmental justice, testing, medical treatment and therapy). Prioritizing the environmental health, promoting new approaches to protect human health, diffusing public messaging and health education programs are of paramount importance in an era of COVID-19, pollution and climate change. In this context, developing policy and research programs that are nimble enough to allow us to fine-tune our interventions and research tools to quickly stay ahead of the pandemic trajectory to combat and mitigate pollution and climate change is important. New collaborative research frameworks are vital to ensure that the health needs of people living in cities, rural and remote communities can be assisted with appropriate access to health education program, and ground-breaking technological research.

A call out addressing grand challenges in environmental science research on this topic to investigate the fate and behaviors of aerosols, CO2, and several others atmospheric pollutants (e.g., volatile persistent organic pollutants [POPs], gaseous elemental mercury vapor [Hg0] and inorganic divalent mercury [Hg2+]), as well as additional greenhouse gases (e.g., atmospheric methane [CH4], Nitrous Oxide [N2O], Sulpher Hexaflouride, [SF6]) is also urgently needed as the COVID-19 progresses. Solutions-oriented research and precautionary approaches will be indeed needed to combat the cumulative impact and health effects of atmospheric pollution, climate change and global epidemics of emerging infectious respiratory diseases.

4. Conclusion

The current pandemic is teaching us the ultimate need for behavioral and innovative changes at the individual, community and corporate/industrial levels and that we may be missing a great opportunity, if precautionary actions to prevent, and reduce air pollution and CO2 emissions are not implemented now. Carbon emissions will be on the rise and surging back as COVID-19 lockdowns are uplift or relaxed amidst the re-opening of economics and industrial activities, mainly in developed nations. Meanwhile, pending the end of this pandemic, researching governments’ decisions on how to reactivate economies in an environmentally sustainable and socially equitable way will be crucial to keep locking down carbon emissions and reduce and eliminate air pollution, which are essential for global environmental health inequity and justice, the protection of biodiversity and the conservation of planet Earth.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Juan José Alava: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal data analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Gerald G. Singh: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal data analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Nippon Foundation for providing research funding through the Nippon Foundation-Ocean Litter Project at University of British Columbia, Canada and the Nippon Foundation Nexus Program at Memorial University of Newfoundland. The authors also acknowledges the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)-Goddard Space Flight Center and the NASA-Earth Observatory for the image use policy (https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/image-use-policy), including the images used in this article, freely available for re-publication or re-use.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2022.01.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- Afshari R. Indoor air quality and severity of COVID-19: where communicable and non-communicable preventive measures meet. Asia Pac. J. Med. Toxicol. 2020;9:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Asundi A., O’Leary C., Bhadelia N. Global COVID-19 vaccine inequity: the scope, the impact, and the challenges. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(7):1036–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barré J., Petetin H., Colette A., Guevara M., Peuch V.-H., Rouil L., Engelen R., Inness A., Flemming J., Pérez García-Pando C., Bowdalo D., Meleux F., Geels C., Christensen J.H., Gauss M., Benedictow A., Tsyro S., Friese E., Struzewska J., Kaminski J.W., Douros J., Timmermans R., Robertson L., Adani M., Jorba O., Joly M., Kouznetsov R. Estimating lockdown-induced European NO2 changes using satellite and surface observations and air quality models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:7373–7394. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-7373-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens M., Compernolle S., Stavrakou T., Müller J.-F., van Gent J., Eskes H., et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on NO2 pollution assessed using TROPOMI and OMI observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020;47 doi: 10.1029/2020GL087978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal A., Singh V., Singh S., Kesarkar A.P., Ravindra K., Sokhi R.S., Chipperfield M.P., Dhomse S.S., Pope R.J., Singh T., Mor S. COVID-19 lockdown-induced changes in NO2 levels across India observed by multi-satellite and surface observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:5235–5251. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-5235-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R., Cullen, K., Fay, B., Hale, T., Lang, J., Mahmood, S., Smith, S., 2021. Taking stock: A global assessment of net zero targets. Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit and Oxford Net Zero. 〈https://eciu.net/analysis/reports/2021/taking-stock-assessment-net-zero-targets〉 (Accessed 12 August 2021).

- Bond A., Pope J., Fundingsland M., Morrison-Saunders A., Retief F., Hauptfleisch M. Explaining the political nature of environmental impact assessment (EIA): a neo-Gramscian perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;244 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A., Pope J., Morrison-Saunders A., Retief F., Gunn J.A. Impact assessment: eroding benefits through streamlining? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2014;45:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2013.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A.J., Brauer M., Burnett R., Anderson H.R., Frostad J., Estep K., Balakrishnan K., Brunekreef B., Dandona L., Dandona R., Feigin V. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the global burden of diseases study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A., Singh R.P. Decline in PM2. 5 concentrations over major cities around the world associated with COVID-19. Environ. Res. 2020;187 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Huo J., Fu Q., Duan Y., Xiao H., Chen J. Impact of quarantine measures on chemical compositions of PM2. 5 during the COVID-19 epidemic in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagnet, Y., Jaeger, J., 2020. Not enough climate action in stimulus plans. World Resource Institute (WRI), Washington, DC. 15 September 2020 〈https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/09/coronavirus-green-economic-recovery〉 (Accessed 28 June 2021).

- Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis.. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert D., Zickfeld K. What determines the warming commitment after cessation of CO2 emissions? Environ. Res. Lett. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa564a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S., 2020. Analysis: Coronavirus set to cause largest ever annual fall in CO2 emissions. Carbon Brief. 9 April 2020. 〈https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-set-to-cause-largest-ever-annual-fall-in-co2-emissions〉 (accessed 28 April 2020).

- Girardin C.A., Jenkins S., Seddon N., Allen M., Lewis S.L., Wheeler C.E., Griscom B.W., Malhi Y. Nature-based solutions can help cool the planet—if we act now. Nature. 2021;593(191–194) doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkatzelis G.I., Gilman J.B., Brown S.S., Eskes H., Gomes A.R., Lange A.C., McDonald B.C., Peischl J., Petzold A., Thompson C.R., Kiendler-Scharr A. The global impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns on urban air pollution: a critical review and recommendations. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2021;9(1):00176. doi: 10.1525/elementa.2021.00176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC . In: Masson-Delmotte V., Zhai P., Pörtner H.-O., Roberts D., Skea J., Shukla P.R., Pirani A., Moufouma-Okia W., Péan C., Pidcock R., Connors S., Matthews J.B.R., Chen Y., Zhou X., Gomis M.I., Lonnoy E., Maycock T., Tignor M., Waterfield T., editors. World Meteorological Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. Summary for Policymakers: Global Warming of1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industriallevels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context ofstrengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainabledevelopment, and efforts to eradicate poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal L.N., Krotkov N.A., Vasilkov A., Marchenko S., Qin W., Yang E.-S., Fasnacht Z., Joiner J., Choi S., Haffner D., Swartz W.H., Fisher B., Bucsela E. Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) Aura nitrogen dioxide standard product version 4.0 with improved surface and cloud treatments. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021;14:455–479. doi: 10.5194/amt-14-455-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan P.J., Fuller R., Acosta N.J., Adeyi O., Arnold R., Baldé A.B., Bertollini R., Bose-O'Reilly S., Boufford J.I., Breysse P.N., Chiles T. The lancet commission on pollution and health. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):462–512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Quéré C., Jackson R.B., Jones M.W., Smith A.J., Abernethy S., Andrew R.M., De-Gol A.J., Willis D.R., Shan Y., Canadell J.G., Friedlingstein P. Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020;10:647–653. doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liverpool L. Why are ethnic minorities worse affected? New Sci. 2020;246(3279):11. doi: 10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30790-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Gallagher E., Simmons R., Thelwall S., et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. New Engl. J. Med. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H.D., Landry J.S., Partanen A.I., Allen M., Eby M., Forster P.M., Friedlingstein P., Zickfeld K. Estimating carbon budgets for ambitious climate targets. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2017;3(1):69–77. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, M., 2020. Coronavirus: Air pollution and CO2 fall rapidly as virus spreads. BBC News. March 19, 2020. 〈https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-51944780〉 (Accessed 28 April 2020).

- Mallapaty S. COVID vaccines slash viral spread – but Delta is an unknown. Nature. 2021;596(7870):17–18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S., Bonin, A. , 2020. Achieving the SDGs through the COVID-19 response and recovery. Policy Brief #78. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, UN DESA. 11 June 2020 〈https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-78-achieving-the-sdgs-through-the-covid-19-response-and-recovery/〉 (Accessed 28 June 2021).

- NASA, 2020a. Airborne Nitrogen dioxide plummets over China. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Earth Observatory. 〈https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/146362/airborne-nitrogen-dioxide-plummets-over-china〉 (Accessed 29 April 2020).

- NASA, 2020b. Airborne particle levels plummet in northern India. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Earth Observatory. 〈https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/146596/airborne-particle-levels-plummet-in-northern-india〉 (Accessed 28 April 2020).

- NOAA, 2020a. Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Can we see a change in the CO2 record because of COVID-19? Monthly Average Mauna Loa CO2. Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii. Earth System Research Laboratories, Global Monitoring Laboratory, Department of Commerce, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. 〈https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/〉 (Accessed 28 April 2020).

- NOAA, 2020b. Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Can we see a change in the CO2 record because of COVID-19? Earth System Research Laboratories, Global Monitoring Laboratory, Global Monthly Mean CO2.The Global Monitoring Division of NOAA/Earth System Research Laboratory, Department of Commerce, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. 〈https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/global.html〉 (Accessed 28 April 2020).

- OECD, 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Focus on green recovery. 〈https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/themes/green-recovery#Green-recovery-database〉 (Accessed 12 August 2021).

- Patel J.A., Nielsen F.B.H., Badiani A.A., Assi S., Unadkat V.A., Patel B., Ravindrane R., Wardle H. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Publ. Health. 2020;183:110–111. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putaud J.-P., Pozzoli L., Pisoni E., Martins Dos Santos S., Lagler F., Lanzani G., Dal Santo U., Colette A. Impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on air pollution at regional and urban background sites in northern Italy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:7597–7609. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-7597-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quitzow R., Bersalli G., Eicke L., Jahn J., Lilliestam J., Lira F., Marian A., Süsser D., Thapar S., Weko S., Williams S., Xue B. The COVID-19 crisis deepens the gulf between leaders and laggards in the global energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021;74 doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.101981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan A.K., Patra A.K., Gorai A.K. Effect of lockdown due to SARS COVID-19 on aerosol optical depth (AOD) over urban and mining regions in India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;745(141024):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom D., Markard J. A COVID-19 recovery for climate. Science. 2020;368(6490):447. doi: 10.1126/science.abc4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Singh S., Biswal A., Kesarkar A.P., Mor S., Ravindra K. Diurnal and temporal changes in air pollution during COVID-19 strict lockdown over different regions of India. Environ. Pollut. 2020;266(115368):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Brasseur G.P. The response in air quality to the reduction of Chinese economic activities during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020;47 doi: 10.1029/2020GL088070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.R., Woodward A., Campbell-Lendrum D., Chadee D.D., Honda Y., Liu Q., Olwoch J.M., Revich B., Sauerborn R. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Field C.B., Barros V.R., Dokken D.J., Mach K.J., Mastrandrea M.D., Bilir T.E., Chatterjee M., Ebi K.L., Estrada Y.O., Genova R.C., Girma B., Kissel E.S., Levy A.N., MacCracken S., Mastrandrea P.R., White L.L., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2014. Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits; pp. 709–754.〈https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/human-health-impacts-adaptation-and-co-benefits/〉 [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England. Technical briefing 29. 26 November 2021 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1036501/Technical_Briefing_29_published_26_November_2021.pdf (accessed 13 January 2022).

- United Nations . Department of Economic and Social Affairs United Nations. United Nations Publications; New York, NY, United States of America: 2021. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020; p. 64.〈https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf〉 accessed 12 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP, 2019. Emissions Gap Report 2019. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. 〈http://www.unenvironment.org/emissionsgap〉.

- Venter Z.S., Aunan K., Chowdhury S., Lelieveld J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(32):18984–18990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006853117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VividEconomics., 2020. Green Stimulus Index. An assessment of the orientation of COVID-19 stimulus in relation to climate change, biodiversity and other environmental impacts. Finance for Biodiversity Initiative. https://www.vivideconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/200820-GreenStimulusIndex_web.pdf (accessed 28 June 2021).

- WHO, 2016. Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 〈https://www.who.int/phe/publications/air-pollution-global-assessment/en/〉.

- WHO, 2018. Climate change and health. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. February 1, 2018. 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health〉 (Accessed 28 April 2020).

- WHO., 2021. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. 26 November 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern (accessed 13 January 2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material