Abstract

Data from four recent studies (S. H. Goh et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2164–2166, 1998; S. H. Goh et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:818–823, 1996; S. H. Goh et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3116–3121, 1997; A. Y. C. Kwok et al., Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1181–1192, 1999) suggest that an approximately 600-bp region of the chaperonin 60 (Cpn60) gene, amplified by PCR with a single pair of degenerate primers, has utility as a potentially universal target for bacterial identification (ID). This Cpn60 gene ID method correctly identified isolates representative of numerous staphylococcal species and Streptococcus iniae, a human and animal pathogen. We report herein that this method enabled us to distinguish clearly between 17 Enterococcus species (Enterococcus asini, Enterococcus rattus, Enterococcus dispar, Enterococcus gallinarum, Enterococcus hirae, Enterococcus durans, Enterococcus cecorum, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus mundtii, Enterococcus casseliflavus, Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus malodoratus, Enterococcus raffinosus, Enterococcus avium, Enterococcus pseudoavium, Enterococcus new sp. strain Facklam, and Enterococcus saccharolyticus), and Vagococcus fluvialis, Lactococcus lactis, and Lactococcus garvieae. From 123 blind-tested samples, only two discrepancies were observed between the Facklam and Collins phenotyping method (R. R. Facklam and M. D. Collins, J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:731–734, 1989) and the Cpn60 ID method. In each case, the discrepancies were resolved in favor of the Cpn60 ID method. The species distributions of the 123 blind-tested isolates were Enterococcus new sp. strain Facklam (ATCC 700913), 3; E. asini, 1; E. rattus, 4; E. dispar, 2; E. gallinarum, 20; E. hirae, 9; E. durans, 9; E. faecalis, 12; E. mundtii, 3; E. casseliflavus, 8; E. faecium, 25; E. malodoratus, 3; E. raffinosus, 8; E. avium, 4; E. pseudoavium, 1; an unknown Enterococcus clinical isolate, sp. strain R871; Vagococcus fluvialis, 4; Lactococcus garvieae, 3; Lactococcus lactis, 3; Leuconostoc sp., 1; and Pediococcus sp., 1. The Cpn60 gene ID method, coupled with reverse checkerboard hybridization, is an effective method for the identification of Enterococcus and related organisms.

Enterococcus species are a frequent source of hospital-acquired infections, ranging from urinary tract infections to endocarditis, surgical wound infections, bloodstream infections, and neonatal sepsis (18, 28). Enterococci were found to be the second and third most common causes of nosocomial urinary tract infections and bacteremias, respectively (18, 28). Recently, 36% of 41 participating medical centers reported the isolation of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from patients with bloodstream infection in the United States (18). With the rapid increase in nosocomial infections with multiple-drug-resistant enterococci, accurate identification to the species level (ID) is important for appropriate drug therapy, especially in relation to vancomycin resistance. For example, Enterococcus gallinarum and Enterococcus casseliflavus are intrinsically resistant to low levels of vancomycin (VanC phenotype) (33). Some strains of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis may acquire a VanB phenotype—an inducible, variable level of resistance to vancomycin—or a VanA phenotype, which confers resistance to high levels of both vancomycin and teicoplanin (21, 23, 24, 27, 32). A VanD phenotype that is highly resistant to vancomycin, but sensitive to even low levels of teicoplanin, has also been described (26), as well as a VanE phenotype resistant to low levels of vancomycin and susceptible to teicoplanin (13).

Commonly, Enterococcus species are identified by a combination of morphological and culture characteristics (11, 12). However, the occurrence of atypical phenotypic characteristics can lead to misidentification. Automated ID systems and kits can also give rise to errors in the identification of the enterococci and bacterial species such as Lactococcus garvieae, Lactococcus lactis, and Vagococcus fluvialis, which are sometimes misidentified as enterococci (12, 17, 18, 29, 34). Other phenotypic identification methods include whole-cell protein profile analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (22). Genotypic ID methods for enterococci have been reported, such as the genus-specific probe from Gen-Probe (LaJolla, Calif.), which reacts positively with all enterococci except Enterococcus cecorum, Enterococcus columbae, and Enterococcus saccharolyticus (12). Some Vagococcus species also react with the probe described above (10). Another Enterococcus genus-specific, PCR-based identification method was reported recently that utilizes the tuf gene (33). However, the primers used for this method also amplified the genes from six bacterial species belonging to two other genera that were tested as negative controls in the study (19). Other species-specific probes and DNA-based molecular methods have been described to identify enterococci to the species level (1, 2, 5, 6, 13, 25, 30, 35). Most of these studies involved the analysis of a limited number of enterococcal species, although those species analyzed are the most common human Enterococcus isolates. Recent studies (14–16, 20) have shown that the chaperonin 60 gene (Cpn60, also known as Hsp60) can be utilized for microbial species ID. Cpn60 genes, found universally in eubacteria and eucaryotes, encode ∼60-kDa polypeptides with a conserved primary structure (9). We have found that sufficient interspecies DNA sequence variation occurs in an ∼600-bp region within the Cpn60 gene to make it the basis for a species-specific, molecular ID method. We report here the results of the application of this method to identify 17 Enterococcus species, as well as Lactococcus lactis, Lactococcus garvieae, and Vagococcus fluvialis. To determine the efficacy of this test, Cpn60 gene sequences amplified from 123 isolates were test hybridized, under a blinded protocol, against amplicons from this panel of bacterial species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

The reference bacterial isolates used were E. saccharolyticus ATCC 43076, Enterococcus pseudoavium ATCC 49372, Enterococcus avium ATCC 14025, Enterococcus raffinosus ATCC 49427, Enterococcus malodoratus ATCC 43197, E. faecium ATCC 19434, E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788, Enterococcus mundtii ATCC 43186, E. faecalis ATCC 19433, Enterococcus hirae ATCC 8043, E. cecorum ATCC 43198, E. gallinarum ATCC 49573, Enterococcus durans ATCC 19432, Enterococcus dispar ATCC 51266, Enterococcus rattus (ATCC 700914), Enterococcus asini (ATCC 700915), and a new Enterococcus sp. strain, CDC-1390-83 (ATCC 700913), as well as Vagococcus fluvialis ATCC 49515, Lactococcus lactis ATCC 19435, and Lactococcus garvieae ATCC 43921. The identities of the blind-tested samples were previously determined by phenotypic characterization as described previously (10, 11).

Digoxigenin tagging of Cpn60 gene fragments by direct PCR incorporation of digoxigenin-11-dUTP.

Extraction of crude DNA from bacterial cultures by the Instagene method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol, except that instead of picking a single colony from a blood agar plate, a disposable inoculating loop was used to sweep across the culture plate to harvest multiple colonies. The PCR protocol was as described in reference 16. The primers for PCR were those described in the following section. The digoxigenin-labeled Cpn60 PCR products, without purification, were diluted 1:100 in hybridization buffer (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate], 50% formamide, 2% Boehringer Mannheim blocking reagent, 0.1% N-lauryl sarcosine, 0.02% SDS and used directly for reverse checkerboard hybridization.

Preparation of Cpn60 PCR product from reference bacterial isolates.

The PCR amplification protocol and purification methods to generate the Cpn60 PCR product from each reference bacterial species were performed exactly as described in reference 16, except for the degenerate PCR primers (H279A and H280A), which are shown in Fig. 1. The PCR products were used as the filter-immobilized probes for reverse checkerboard hybridization with the Immunetics, Inc. (Cambridge, Mass.), miniblot apparatus.

FIG. 1.

Structures of degenerate PCR primers and PCR products. (A) Sequences of PCR primers H729, H279A, H730, and H280A. Nucleotides 1 to 24 of both H729 and H730 are the M13 forward and reverse sequencing primers, respectively (underlined). Nucleotides 25 to 50 of H729 and H730 and 1 to 25 of H279A and H280A (italicized) are degenerate sequences encoding degenerate Cpn60 peptide sequences. (B) Schematic representation of amplification of Cpn60 PCR products with primers H729 and H730 or H279A and H280A. In each case, the PCR product includes 552 bp of template-specific Cpn60 sequence (grey bar). The 652-bp product of H729 and H730 was used as a sequencing template, while the product of H279A and H280A was used in hybridization assays.

Cpn60 gene ID by reverse checkerboard hybridization and chemiluminescent detection.

The minislot 30 and miniblot 45 devices from Immunetics, Inc., were used for reverse checkerboard hybridization and chemiluminescent detection experiments. The protocols were as reported previously (16). Briefly, the minislot 30 apparatus was used to immobilize each PCR-generated 604-bp target from type strains onto a nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim) in 0.1-by-13-cm slots. After 60 min at 42°C in prehybridization buffer, the filter was loaded into the miniblot apparatus, such that the bands of immobilized target DNA formed in the minislot apparatus were perpendicular to the minichannels of the miniblot apparatus. Digoxigenin-labeled probes were introduced into individual minichannels, and hybridization proceeded overnight. Hybridization times of 1 to 2 h are also sufficient to generate discernible positive signals. The filters were washed at high stringency (68°C with 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS), and Boehringer Mannheim protocols for chemiluminescent detection of hybridized digoxigenin-labeled probes were followed.

Sequence analysis and phylogeny methods.

PCR products generated with primers H729 and H730 (Fig. 1) were sequenced directly by cycle sequencing at the NRC Plant Biotechnology Institute core facility by using M13 forward and reverse sequencing primers. Sequence analysis and alignments were done with the GCG Wisconsin Package (version 10.0-UNIX; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.). Phylogenetic analysis was done with the programs seqboot, dnadist, neighbor, and consense within the PHYLIP phylogeny package (version 3.57c; J. Felsenstein, 1995). Trees were viewed and converted to a graphic format with TreeView (R. D. M. Page, 1998).

RESULTS

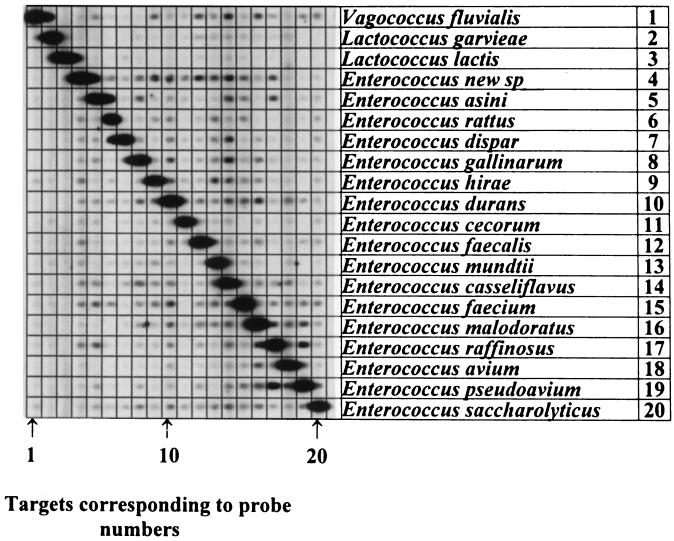

Cpn60 gene segments were amplified from 17 Enterococcus species, 2 Lactococcus species, and a single Vagococcus type species. The specificity of the Cpn60 gene method for identification of these species was tested simultaneously by using each amplified Cpn60 gene segment as a hybridization probe against the entire panel, by a reverse checkerboard protocol. Species identification was inferred if a hybridization signal was generated at the intersection of a probe lane with a single target lane. The result is shown in Fig. 2. Each digoxigenin-labeled Cpn60 probe hybridized specifically, producing a signal only against the unlabeled Cpn60 target from the same species. The three nonenterococci tested also generated species-specific signals in this test and showed no cross-hybridization with any of the enterococci (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Reverse checkerboard hybridization results of type strains of organisms used as probes in the study. The strain of each species is as identified in Materials and Methods. The Cpn60 600-bp DNA targets are immobilized on the membrane as horizontal slots. The probes are introduced into thin channels of the miniblot apparatus that run perpendicular to the targets. The numbers indicating the probe lanes correspond to the respective numbers designating each organism in the horizontal positions.

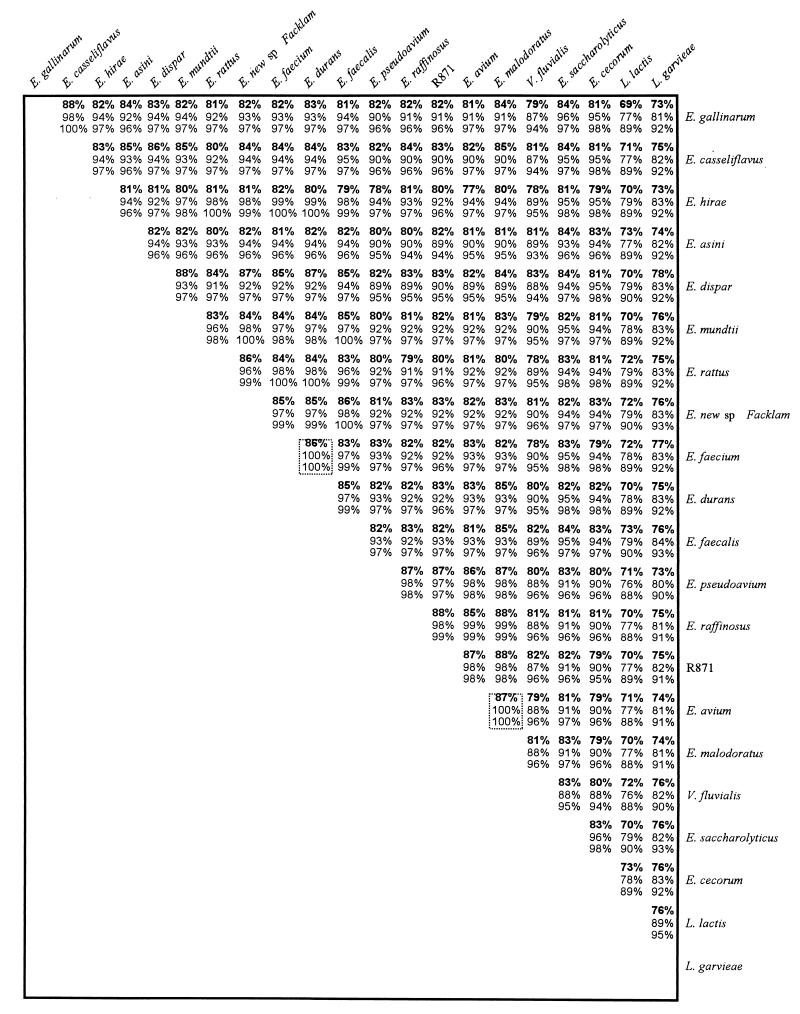

Sequences were determined for the Cpn60 PCR products generated from each of the test species (Fig. 2). Sequence data were deposited in GenBank and assigned the following accession numbers: Enterococcus asini, AF245671; Enterococcus rattus, AF245669; Enterococcus dispar, AF245668; Enterococcus gallinarum, AF245667; Enterococcus hirae, AF245666; Enterococcus durans, AF245686; Enterococcus cecorum, AF245685; Enterococcus faecalis, AF245684; Enterococcus mundtii, AF245683; Enterococcus casseliflavus, AF245682; Enterococcus faecium, AF245681; Enterococcus malodoratus, AF245680; Enterococcus raffinosus, AF245679; Enterococcus avium, AF245678; Enterococcus pseudoavium, AF245677; Enterococcus new sp. strain Facklam, AF245672; Enterococcus saccharolyticus, AF245676, Enterococcus sp. strain R871, AF245670; Vagococcus fluvialis, AF245675; Lactococcus lactis, AF245673; and Lactococcus garvieae, AF245674. The correct alignment of the 552-bp template-specific nucleotide sequences (Fig. 2) was trivial, since their identical lengths and overall similarity permitted an ungapped alignment (data not shown). A summary of the nucleotide and inferred peptide sequence identity and similarity of these sequences is shown in Fig. 3. Among all species, nucleotide sequence identity ranged between 69 and 88%, peptide sequence identity ranged between 76 and 100%, and similarity ranged between 88 and 100%. Within the enterococci, nucleotide sequence identities ranged from 77% (E. hirae versus E. avium) to 88% (E. gallinarum versus E. casseliflavus, E. dispar versus E. mundtii, E. raffinosus versus Enterococcus sp. strain R871, E. raffinosus versus E. malodoratus, and Enterococcus sp. strain R871 versus E. malodoratus). In two cases (E. faecium versus E. durans and E. avium versus E. malodoratus), nucleotide sequences were divergent (86 and 87% identity, respectively), while the peptide sequences of each pair were 100% identical. Clinical isolate R871 was most similar to E. raffinosus (88% nucleotide sequence identity, 98% amino acid sequence identity). The nucleotide sequence from L. garvieae ranged from a low of 73% identity to Enterococcus species (E. gallinarum, E. hirae, and E. pseudoavium) to a high of 78% identity (E. dispar).

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence identity (top values, boldface), amino acid sequence identity (middle values), and similarity (bottom values) for the 600-bp Cpn60 sequence fragments from E. gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, E. hirae, E. asini, E. dispar, E. mundtii, E. rattus, Enterococcus new sp. Facklam, E. faecium, E. durans, E. faecalis, E. pseudoavium, E. raffinosus R871, E. avium, E. malodoratus, V. fluvialis, E. saccharolyticus, E. cecorum, L. lactis, and L. garvieae reference isolates. The sequences used in this analysis are the 552-bp sequences between the degenerate PCR primer annealing sites in each case. Boxes indicate instances in which there is divergence at the nucleotide level, but the amino acid sequences are identical.

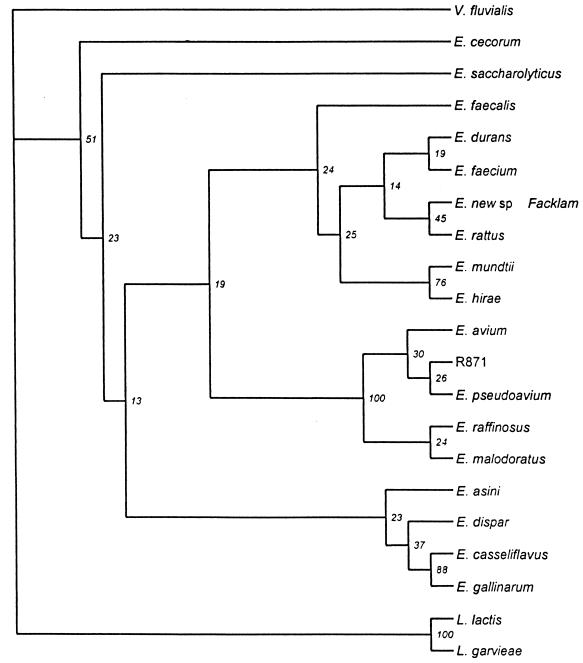

The aligned nucleotide sequences were used as the basis for generating phylogenetic trees (Fig. 4). Bootstrapping iterations (a total of 500) were produced from the alignment, and distance matrices were calculated by a maximum likelihood method. The corresponding neighbor-joined trees were produced with V. fluvialis as an outgroup root. Three major groupings within the enterococci were evident. The first group consisted of E. faecalis, E. durans, E. faecium, Enterococcus new sp. strain Facklam (ATCC 700913), E. rattus, E. mundtii, and E. hirae. The second group consisted of R871, E. avium, E. pseudoavium, E. raffinosus, and E. malodoratus. The third group consisted of E. asini, E. dispar, E. casseliflavus, and E. gallinarum.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on a CLUSTAL W alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the 552-bp region of Cpn60 between the degenerate primers used in PCR amplification. The tree (drawn in the rectangular cladogram format) is a consensus of neighbor-joined trees generated from maximum likelihood distance matrices for 500 bootstrapping iterations. The tree is rooted with V. fluvialis as the outgroup. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages) are shown at each branch point. Branch lengths in this consensus tree format are arbitrary.

To validate the utility of the Cpn60 gene ID method for Enterococcus identification, 121 isolates previously identified by the method of Facklam and Collins (11) were tested under a blinded protocol. Identification by the Cpn60 gene ID method corresponded to that by the phenotypic methods in 121 of 123 cases (Table 1). Only two discrepancies were found in the study. Strains 0286-86 and R871 were both identified as E. avium by conventional phenotyping. However, 0286-86 was identified as E. raffinosus by Cpn60 ID, while R871 failed to hybridize to any of the type species listed in Fig. 2 (Table 1). Replating and retesting of the discrepant isolates by both methods reproduced these results. Subsequently, whole-cell protein analysis (22) done on 0286-86 also identified the isolate as E. raffinosus (data not shown), thus supporting the original Cpn60 ID result. Furthermore, DNA sequencing of the Cpn60 PCR fragment from 0286-86 showed complete identity with E. raffinosus ATCC 49427. Pairwise sequence comparisons of the Cpn60 PCR product from R871 (GenBank accession no. AF245670) revealed that this isolate is most similar to E. raffinosus (88% nucleotide sequence identity, 98% amino acid sequence identity). These data explain the observed failure of R871 to hybridize with any of the DNA probes immobilized on the filters, including E. raffinosus ATCC 49927 (Table 1). Each of the Leuconostoc and Pediococcus isolates which correctly failed to hybridize to any of the immobilized probes shown in Fig. 2 could not be identified by the Cpn60 ID method, because the appropriate species-specific probes were not included in the hybridization blot.

TABLE 1.

Results of phenotyping, Cpn60 ID, and sequence comparisons for 121 organisms examined in this study

| Organism | No. of strains | Result by: methoda

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotyping | Cpn60 ID | Sequence | ||

| Enterococcus avium | 2 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus pseudoavium | 1 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus raffinosus | 8 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus malodoratus | 3 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus faecium | 23 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus casseliflavus | 8 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus mundtii | 3 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 12 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus durans | 9 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus hirae | 9 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus gallinarum | 20 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus dispar | 2 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus rattus | 4 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus asini | 1 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus new sp. (Facklam) | 3 | + | + | + |

| Lactococcus lactis | 2 | + | + | + |

| Lactococcus garvieae | 3 | + | + | + |

| Vagococcus fluvialis | 4 | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus avium (0286-86) | 1 | E. avium | E. raffinosus | E. raffinosus |

| Enterococcus avium R871 | 1 | E. avium | No hybridization | New species |

| Leuconostoc sp.b | 1 | + | No hybridizationb | NDc |

| Pediococcus sp.b | 1 | + | No hybridizationb | ND |

+, positive identification.

Not included in the hybridization panel (see Results and Discussion).

ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

The miniblot Cpn60 ID chemiluminescent method utilized in this study to identify Enterococcus isolates was previously described to identify Staphylococcus species (16). The format of this method allows the ID of up to 40 bacterial isolates against a background of 30 known target bacterial species at one given time. In a reference laboratory, the larger the number of isolates tested, the lower the cost per test, since the hands-on time is not significantly increased with increased sample numbers. In fact the hands-on time of 90 min for each hybridized membrane is the same regardless of the numbers of bacterial isolates being identified. There can be further significant cost savings if more than one complete blot is processed simultaneously. Also, the membrane can be stripped and reprobed at least three times with no loss of hybridization signal strength (unpublished data). In our laboratory, it presently takes about 28 h from processing the bacterium for PCR amplification to obtaining the DNA hybridization results. The total material and reagent cost per test is $2.10.

The Cpn60 gene ID method distinguished clearly between the type strains of each of the 17 Enterococcus species, 2 Lactococcus species, and 1 Vagococcus species that were tested (Fig. 2). Although standard phenotyping methods (11) can misidentify the three nonenterococcal species that we tested, species-specific ID signals were generated for each of these organisms by the Cpn60 method (Fig. 2).

Like biochemical phenotyping, the Cpn60 ID method can distinguish clearly between E. avium and E. pseudoavium (Fig. 2 and Table 1), which share 86% Cpn60 DNA sequence identity (Fig. 3). The identification of enterococci via the intergenic spacer rRNA PCR method failed to distinguish between these two related species (31). Enterococcus group II (6) includes E. faecium and E. gallinarum, and both have similar biochemical test profiles (11). The only differentiating phenotypic characteristic between them is that E. gallinarum is motile, while E. faecium is not (11). However, there are nonmotile E. gallinarum isolates, and our method reliably identified two nonmotile and six motile E. gallinarum strains that were included in the validation samples. Likewise, E. casseliflavus and E. mundtii, which also belong to group II Enterococcus and share similar phenotypic characteristics, were correctly identified (Table 1). Finally, false negatives were not observed in this study, suggesting that the Cpn60 sequences within isolates of each species are well conserved. However, results from ongoing diagnostic tests of clinical Enterococcus strains will be needed to further confirm these observations.

The clustering of species in this study based on Cpn60 sequence comparisons is similar to the published Enterococcus phylogenetic trees that were based on 16S rRNA sequences (3, 25, 35). The combined 16S rRNA data (3, 25, 35) show three distinct clusters, composed of E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus as one group; E. malodoratus, E. avium, E. pseudoavium, and E. raffinosus in a second group; and E. hirae, E. faecium, E. durans, and E. mundtii in a third group. This is similar to the patterns observed when a phylogenetic tree is generated from Cpn60 sequence data (Fig. 4). However, direct comparison between the 16S rRNA phylogenetic data and the data presented here is problematic, since in two cases (3, 25), the 16S rRNA phylogenetic trees are based on only a single iteration of the sequence alignment, and there is variation in the phylogenetic methods used in each case as well as variation in the number and identity of species included in each analysis. Also, the phylogenetic tree generated for the Cpn60 data is inherently unstable, as indicated by the relatively low bootstrap values, which are likely a direct consequence of the relatively short sequences being compared. Based on the amount of information contained within the sequenced region of Cpn60 (as few as 66 nucleotide differences over the 552-bp region between two 88% identical sequences, such as E. gallinarum versus E. casseliflavus), it is difficult to infer with confidence the detailed phylogenetic relationships between these closely related organisms within the same genus. However, more distant relationships, such as the relationship between members of the Enterococcus genus and the Lactococcus genus, are clearer. A comparison of the Cpn60 nucleotide sequence of L. garvieae with each of the Enterococcus species examined indicated differences of 22 to 27%. Consequently, L. garvieae is appropriately branched outside the Enterococcus domain, but clustered phylogenetically with L. lactis (Fig. 4). This further supports the correct classification of Enterococcus seriolicida as L. garvieae (4, 7, 8, 35).

A nucleotide sequence alignment was chosen as the basis for our phylogenetic analysis, since there are more characters and therefore there is more phylogenetic information in the nucleotide sequence alignment data than in amino acid sequence alignment data (552 nucleotides compared to 184 amino acids). An illustration of this is that the Cpn60 sequences of E. faecium and E. durans are 100% identical at the amino acid level, but only 86% identical at the nucleotide sequence level (Fig. 3). This translates into 77 informative differences between the nucleotide sequences and zero differences between the amino acid sequences of these two species. A similar situation exists for E. avium and E. malodoratus, which are only 87% identical at the nucleotide level, but which are 100% identical at the amino acid level (Fig. 3). Thus, within the sequenced region of the Cpn60 gene, these pairs of Enterococcus species can only be recognized as distinct species at the nucleotide sequence level.

Our present study included two Enterococcus species, E. rattus and a new enterococcus species, which were not included in previous analyses of Enterococcus phylogeny. E. rattus was most similar to E. durans (84% nucleotide identity, 98% amino acid identity, and 100% amino acid similarity), and the new enterococcus species (ATCC 700913) was most similar to E. dispar at the nucleotide level (87% identical) and to E. mundtii and E. faecalis at the amino acid level (98% identical and 100% similar in each case) (Fig. 3). Both E. rattus and the new enterococcus species (ATCC 700913) were found in the E. hirae-E. faecium-E. durans-E. mundtii phylogenetic cluster (Fig. 4). Interestingly, R871, a clinical isolate that failed to hybridize to any of the Enterococcus type strains and was identified phenotypically as E. avium, clustered within the E. avium-E. pseudoavium-E. malodoratus-E. raffinosus phylogenetic group. At the sequence level, R871 was most similar to E. raffinosus (88% nucleotide identity, 98% amino acid identity, and 99% amino acid similarity).

Based on the sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis presented here, it is apparent that the amount of phylogenetic information contained within the 552-bp region of Cpn60 analyzed is sufficient to decipher phylogenetic relationships to the level of groups or clusters of related species. In addition, the sequence differences between the Enterococcus species examined, as reported here, are sufficient to allow precise identification of unknown isolates to the species level by the Cpn60 ID hybridization method.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by funding from the Canadian Biotechnology Strategy.

We thank the PBI Sequencing Laboratory for DNA sequencing services and acknowledge the use of the Canadian Bioinformatics Resource (http://www.cbr.nrc.ca/).

REFERENCES

- 1.Betzel D, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Identification of lactococci and enterococci by colony hybridization with 23S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2927–2929. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2927-2929.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Descheemaeker P, Lammens C, Pot B, Vandamme P, Goossens H. Evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of large genomic DNA fragments for identification of enterococci important in human medicine. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:555–561. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vaux A, Laguerre G, Divies C, Prevost H. Enterococcus asini sp. nov. isolated from the caecum of donkeys (Equus asinus) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:383–387. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domenech A, Prieta J, Fernandez-Garayzabal J F, Collins M D, Jones D, Dominguez L. Phenotypic and phylogenetic evidence for a close relationship between Lactococcus garvieae and Enterococcus seriolicida. Microbiologia. 1993;9:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donabedian S, Chow J W, Shlaes D M, Green M, Zervos M J. DNA hybridization and contour-clamped homogeneous electric field electrophoresis for identification of enterococci to the species level. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:141–145. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.141-145.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:24–27. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.24-27.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldar A, Ghittino C, Asanta L, Bozzetta E, Goria M, Prearo M, Bercovier H. Enterococcus seriolicida is a junior synonym of Lactococcus garvieae, a causative agent of septicemia and meningoencephalitis in fish. Curr Microbiol. 1996;32:85–88. doi: 10.1007/s002849900015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliot J A, Collins M D, Pigott N E, Facklam R R. Differentiation of Lactococcus lactis and Lactococcus garvieae from humans by comparison of whole-cell protein patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2731–2734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2731-2734.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis R J. Chaperonins: introductory perspective. In: Ellis R J, editor. The chaperonins. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1996. pp. 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Facklam R, Elliot J A. Identification, and clinical relevance of catalase-negative, gram-positive cocci, excluding the streptococci and enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:479–495. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facklam R R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facklam R R, Teixeira L M. Enterococcus. In: Collier L, Balows A, Sussman M, editors. Topley & Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections. 9th ed. London, United Kingdom: Arnold Publications; 1998. pp. 669–682. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fines M, Perichon B, Reynolds P, Sahm D F, Courvalin P. VanE, a new type of acquired glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2161–2164. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goh S H, Driedger D, Gillett S, Low D E, Hemmingsen S M, Amos M, Chan D, Lovgren M, Willey B M, Shaw C, Smith J A. Streptococcus iniae, a human and animal pathogen: specific identification by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2164–2166. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2164-2166.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh S H, Potter S, Wood J O, Hemmingsen S M, Reynolds R P, Chow A W. HSP60 gene sequences as universal targets for microbial species identification: studies with coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:818–823. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.818-823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh S H, Santucci Z, Kloos W E, Faltyn M, George C G, Driedger D, Hemmingsen S M. Identification of Staphylococcus species and subspecies by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method and reverse checkerboard hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3116-3121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwen P C, Kelly D M, Linder J, Hinrichs S H. Revised approach for identification and detection of ampicillin and vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus species by using Microscan panels. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1779–1783. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1779-1783.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones R N, Marshall S A, Pfaller M A, Wilke W W, Hollis R J, Erwin M E, Edmond M B, Wenzel R P. Nosocomial enterococcal blood stream infections in the SCOPE Program: antimicrobial resistance, species occurrence, molecular testing results, and laboratory testing accuracy. SCOPE Hospital Study Group Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ke D, Picard F J, Martineau F, Ménard C, Roy P H, Ouellette M, Bergeron M G. Development of a PCR assay for rapid detection of enterococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3497–3503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3497-3503.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwok A Y C, Su S-C, Reynolds R P, Bay S J, Av-Gay Y, Dovichi N J, Chow A W. Species identification and phylogenetic relationships based on partial HSP60 gene sequences within the genus Staphylococcus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1181–1192. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1992;319:157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merquior V L C, Peralta J M, Facklam R R, Teixeira L M. Analysis of electrophoretic whole-cell protein profiles as a tool for characterization of Enterococcus species. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray B E. The life and times of the enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navarro F, Courvalin P. Analysis of genes encoding d-alanine–d-alanine ligase-related enzymes in Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel R, Piper K E, Rouse M S, Steckelberg J M, Uhl J R, Kohner P, Hopkins M K, Cockerill III F R, Kline B C. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of enterococci and application of species identification of nonmotile Enterococcus gallinarum isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3399–3407. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3399-3407.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perichon B, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. VanD-type glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium BM4339. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2016–2018. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quintiliani R, Jr, Evers S, Courvalin P. The vanB gene confers various levels of self-transferable resistance to vancomycin in enterococci. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1220–1223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaberg D R, Culver D H, Gaynes R P. Major trends in the microbial etiology of nosocomial infections. Am J Med. 1991;91(Suppl. 3B):72S–75S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90346-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer D A, Jochimsen E M, Gielerak P, Jarvis W R. Pseudo-outbreak of Enterococcus durans infections and colonization associated with introduction of an automated identification system software update. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2685–2687. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2685-2687.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh K V, Coque T M, Weinstock G M, Murray B E. In vivo testing of an Enterococcus faecalis efaA mutant and use of efaA homologs for species identification. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyrrell G J, Bethune R N, Willey B, Low D E. Species identification of enterococci via intergenic ribosomal PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1054–1060. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1054-1060.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uttley A H, Georges R C, Naidoo J, Woodford N, Johnson A P, Collins C H, Morrison D, Gilfillan A J, Fitch L E, Heptonstall J. High-level vancomycin-resistant enterococci causing hospital infections. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:173–181. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincent S, Knight R G, Green M, Sahm D F, Shlaes D M. Vancomycin susceptibility and identification of motile enterococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2335–2337. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2335-2337.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilke W W, Marshall S A, Coffman S L, Pfaller M A, Edmund M B, Wenzel R P, Jones R N. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus raffinosus: molecular epidemiology, species identification error, and frequency of occurrence in a national resistance surveillance program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams A M, Rodrigues U M, Collins M D. Intergeneric relationships of Enterococci as determined by reverse transcriptase sequencing of small-subunit rRNA. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90098-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]