Abstract

目的

探讨在黑棘皮病(AN)和非黑棘皮病(NAN)人群中的总睾酮水平对胰岛素分泌和胰岛素抵抗的影响及其相关性。

方法

选取超重患者(体质量指数≥24 kg/m2)639例,根据性别及是否有黑棘皮病分为四组:AN女性137例,NAN女性227例,AN男性129例,NAN男性146例。每组按照总睾酮(TT)四分位数分为4个亚组,比较不同TT水平胰岛素分泌和抵抗的差异及变化规律。

结果

无论男性和女性AN组较非AN组胰岛素分泌水平明显增加、胰岛素曲线下面积增加(P < 0.05),稳态模型-胰岛素抵抗指数升高(HOMA-IR)(P < 0.05),总体胰岛素敏感性指数(WBISI)下降(P < 0.01),但并未观察到随TT变化趋势。NAN女性随着TT水平升高,胰岛素分泌水平逐渐升高,TT升高至Q4水平,胰岛素曲线下面积显著升高(P < 0.01)、WBISI明显下降(P < 0.05);而NAN男性随着TT水平下降,胰岛素分泌水平逐渐升高,TT降至Q1水平,胰岛素曲线下面积明显升高(P < 0.05)、WBISI明显下降(P < 0.05)。

结论

总睾酮水平对胰岛素抵抗和胰岛素分泌有明显影响,在男女中具有不同作用,并且在NAN患者中较AN患者中更为明显。

Keywords: 肥胖症, 黑棘皮病, 总睾酮, 胰岛素分泌, 岛素抵抗

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the correlation of the total testosterone (TT) level with insulin secretion and resistance in patients with acanthosis nigricans (AN) and non-acanthosis nigricans (NAN).

Methods

This study was conducted in a total of 639 overweight patients (body mass index ≥24 kg/m2), including 137 female AN patients, 277 female NAN patients, 129 male AN patients, and 146 male NAN patients. Each group was further divided into 4 subgroups according to the quartile of TT level for comparison of insulin secretion and insulin resistance parameters.

Results

Both female and male patients with AN showed obvious hyperinsulinemia with increased area under the curve for insulin (AUC-INS) (P < 0.05), increased homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index (P < 0.05) and decreased whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI) (P < 0.01) as compared with those in NAN groups, but these parameters did not show significant variations with the change of TT levels. In female patients with NAN, insulin secretion level increased progressively as the TT level increased; the AUC-INS increased (P < 0.01) and WBISI decreased significantly (P < 0.05) when the TT levels increased to Q4. In male patients with NAN, insulin secretion level increased progressively as the TT levels decreased, and the AUC-INS increased (P < 0.05) and the WBISI decreased significantly (P < 0.05) when the TT levels decreased to Q1.

Conclusions

The TT level has a significant effect on insulin resistance and insulin secretion, but its effect varies between genders and is more significant in NAN patients than in AN patients.

Keywords: obesity, acanthosis nigricans, total testosterone, insulin secretion, insulin resistance

黑棘皮病(AN)多伴有超重和肥胖,以脂肪过剩、异位分布堆积为特征,常常出现糖脂代谢失调、性激素调节紊乱、β细胞分泌胰岛素增加、高胰岛素血症[1]。黑棘皮病是发生胰岛素抵抗和早期糖尿病的特异性表皮标志[2]。肥胖时高浓度胰岛素不仅与胰岛素受体的结合增加,还直接与皮肤角质形成细胞中胰岛素样生长因子受体结合,导致黑棘皮病的发生[3, 4]。高雄激素血症、胰岛素抵抗和黑棘皮病综合征中,胰岛素抵抗和高雄激素血症的严重程度呈正相关[5],也有研究认为女性高雄激素、男性低雄激素与肥胖和黑棘皮病有关[6]。

但黑棘皮病皮肤症状的严重程度与雄激素水平并没有直接相关性[7],体脂总量增加的本身也不是黑棘皮病雄激素水平异常的主要原因[5]。研究表明,黑棘皮病空腹胰岛素水平和睾酮、雄烯二酮水平显著相关[7]。一项回顾性横断面研究发现,患有多囊卵巢综合征的肥胖女性游离雄激素指数、雄烯二酮、高雄激素血症与HOMA-IR正相关[8]。肥胖黑棘皮病男性患者雄激素水平总体偏低,而行袖带减重术后总睾酮水平与FINS、HOMA-IR正相关[9]。以往的研究多使用小样本,仅提示肥胖/超重的黑棘皮病和非黑棘皮病的发生发展过程中,雄激素总体异常和胰岛功能之间的相互作用可能起到重要作用,但具体的雄激素水平分级差异对不同疾病的影响尚待进一步研究。我们采用回顾性研究,分析不同总睾酮水平时,不同性别黑棘皮病和非黑棘皮病人群胰岛素抵抗和胰岛素敏感性等指标的差异,以探索总睾酮对胰岛功能影响的特点和规律,发现可能影响胰岛功能变化的总睾酮水平范围。

1. 资料和方法

1.1. 研究对象

自2010年01月~2019年12月,上海市第十人民医院内分泌科就诊的BMI≥24 kg/m2的患者共639例(男性年龄18~60岁,女性年龄18~50岁),其中黑棘皮患者266例,非黑棘皮患者373例,进行回顾性病例对照研究。本研究经上海市第十人民医院伦理委员会批准(临床注册号: ChiCTR-OCS-12002381),获得研究对象同意后采集基础资料。

1.2. 诊断标准

(1)超重:体质量指数(BMI)≥24 kg/m2;(2)肥胖症:BMI≥28 kg/m2;(3)总睾酮水平:以上海市第十人民医院检测设备测定本地人群后确定的正常范围值为标准,女性总睾酮(TT)高于1.42 nmol/L为高雄激素,男性总睾酮低于6.68 nmol/L为雄激素降低;(4)黑棘皮病:颈部皮肤出现黑棘皮样病变,局限于颅骨下方,或超过颈部侧缘,宽度≥2 cm[10]。

1.3. 排除标准

(1)糖尿病、继发性黑棘皮病、继发性肥胖症,伴急慢性重度感染、器官功能衰竭、恶性肿瘤及急性应激状态,妊娠及哺乳期女性,服用激素等影响雄激素水平的药物者。

1.4. 指标测定及评估方法

研究对象空腹8 h,于次晨抽取静脉血,采用放射免疫法测定总睾酮。并进行75 g口服葡萄糖耐量实验(OGTT)和胰岛素释放实验(IRT),测定0、30、60、120、180 min血浆葡萄糖(GLU)和胰岛素(INS)水平,计算稳态模型-胰岛素抵抗指数(HOMA-IR)=PG0 ×INS0/ 22.5,胰岛素生成指数(IGI)=△INS30/△PG30=(INS30-INS0)(/PG30-PG0),稳态模型-胰岛β细胞功能指数(HOMA-β)=20×INS0[/PG0-3.5],总体胰岛素敏感性指数(WBISI)=10 000/平方根{INS0×PG0×[(PG平均×INS平均)]},血糖曲线下面积(AUC- GLU)=0.5 ×[30 ×(PG0 +PG30)+30×(PG30 +PG60)+60×(PG60 +PG120)+60× (PG120 +PG180)],胰岛素曲线下面积(AUC-INS)=0.5×[30 ×(INS0 + INS30)+ 30 × (INS30 + INS60) + 60 × (INS60 + INS120)+60×(INS120+INS180)]。

1.5. 统计学方法

统计学分析及图表绘制用SPSS 22.0软件进行。协方差分析用于比较正态分布两组组间差异。组间构成比用卡方检验。以时间为横坐标,分别以血浆葡萄糖、血浆胰岛素水平为纵坐标,绘制四分位总睾酮水平时血浆葡萄糖及胰岛素曲线图。P < 0.05为差异有统计学差异。

2. 结果

2.1. 不同总睾酮水平血糖和血糖曲线下面积变化

不同总睾酮水平黑棘皮病、非黑棘皮病患者的血糖无明显统计学差异(图 1、2)。男性和女性的AUC-GLU在不同总睾酮水平均无明显统计学差异(表 1)。

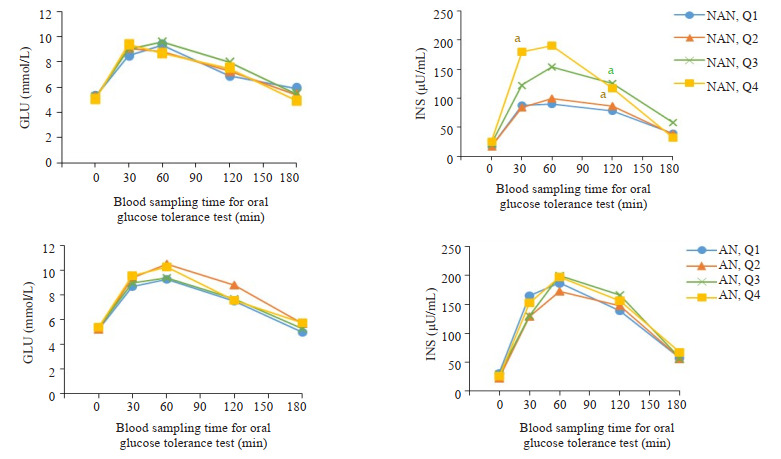

1.

OGTT and IRT:女性非黑棘皮病患者及黑棘皮病患不同总睾酮水平血糖和胰岛素变化

Curves of glucose and insulin levels changes in OGTT and IRT female NAN and AN patients with different total testosterone levels. NAN quartile groupings of female (NAN, Q): NAN, Q1 (TT 0.06-0.72 nmol/L); NAN, Q2 (TT 0.73-1.20 nmol/L); NAN, Q3 (TT 1.21-1.82 nmol/L); NAN, Q4 (TT 1.86-10.20 nmol/L). AN quartile groupings for female (AN, Q): AN, Q1 (TT 0.09-0.69 nmol/l), AN, Q2 (TT 0.76-1.16 nmol/L); AN, Q3 (TT 1.22-1.83 nmol/L); AN, Q4 (TT 1.86-6.86 nmol/L). aP < 0.05 vs Q1. NAN: Non-acanthosis nigrican; AN: Acanthosis nigrican.

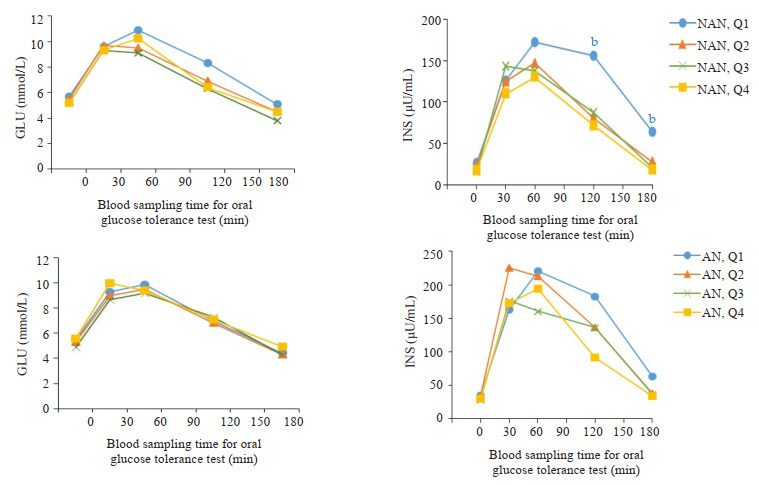

2.

OGTT and IRT:男性非黑棘皮病患者及黑棘皮病患不同总睾酮水平血糖和胰岛素变化

Changes of glucose and insulin levels in OGTT and IRT in male NAN and AN patients with different total testosterone levels. NAN quartile groupings for males (NAN, Q): NAN, Q1 (TT 0.10-6.40 nmol/L); NAN, Q2 (TT 6.50-9.30 nmol/L); NAN, Q3 (TT 9.50-12.00 nmol/L); NAN, Q4 (TT 12.20-44.40 nmol/L). AN quartile groupings for males (AN, Q): AN, Q1(TT 0.16-6.20 nmol/L); AN, Q2 (TT 6.46-9.20 nmol/L); AN, Q3 (TT 9.40-12.10 nmol/L); AN, Q4 (TT 12.20-18.00 nmol/l). bP < 0.01 vs Q4. NAN: Non-acanthosis nigrican; AN: Acanthosis nigrican.

1.

OGTT和IRT:非黑棘皮病及黑棘皮病患者不同总睾酮水平血糖曲线下面积、胰岛素曲线下面积变化

Changes of glucose and insulin area under the curve in OGTT and IRT in female NAN and AN patients with different total testosterone levels

| Group | Female NAN | Female AN | Male NAN | Male AN | |

| NAN quartile groupings of female (NAN, Q): NAN, Q1(TT 0.06-0.72 nmol/L); NAN, Q2(TT 0.73-1.20 nmol/L); NAN, Q3(TT 1.21-1.82 nmol/L); NAN, Q4(TT 1.86-10.20 nmol/L). AN quartile groupings of female (AN, Q): AN, Q1(TT 0.09-0.69 nmol/L); AN, Q2 (TT 0.76-1.16 nmol/L); AN, Q3(TT 1.22-1.83 nmol/L); AN, Q4(TT 1.86-6.86 nmol/l). NAN quartile groupings of male (NAN, Q): NAN, Q1(TT 0.10-6.40 nmol/L); NAN, Q2(TT 6.50-9.30 nmol/L); NAN, Q3(TT 9.50-12.00 nmol/L); NAN, Q4(TT 12.20-44.40 nmol/L). AN quartile groupings of male (AN, Q): AN, Q1(TT 0.16-6.20 nmol/L); AN, Q2(TT 6.46-9.20 nmol/L); AN, Q3(TT 9.40-12.10 nmol/L); AN, Q4(TT 12.20-18.00 nmol/L). AUC-GLU: Area under the glucose curve; AUC-INS: Area under the insulin curve. Compared with Q1 in female and compared with Q4 in male, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01. Compared with NAN quartile groupings, cP < 0.05, dP < 0.01. NAN: Non-acanthosis nigrican; AN: Acanthosis nigrican. | |||||

| n | 227 | 137 | 146 | 129 | |

| Age (year) | 30.76±7.62 | 28.37±6.84 | 32.23±9.12 | 28.26±6.43 | |

| AUC-GLU | |||||

| Q1 | 1330.50 (1150.88, 1487.25) |

1360.50 (1162.50, 1656.00) |

1508.48 (1251.75, 1913.63) |

1363.50 (1248.00, 1527.00) |

|

| Q2 | 1359.00 (1211.25, 1665.75) |

1536.00 (1296.00, 1861.50) |

1315.50 (1149.75, 1818.83) |

1296.00 (1172.63, 1536.38) |

|

| Q3 | 1426.50 (1234.88, 1635.00) |

1386.00 (1216.50, 1666.50) |

1267.50 (1149.75, 1522.50) |

1284.00 (1160.25, 1493.63) |

|

| Q4 | 1363.50 (1195.50, 1602.75) |

1436.25 (1266.00, 1997.25) |

1359.00 (1152.00, 1667.25) |

1410.75 (1253.63, 1738.50) |

|

| AUC-INS | |||||

| Q1 | 13957.50 (7656.98, 20330.44) |

23764.35 (19523.85, 33825.75) |

25165.73 (12962.70, 41568.04)a |

29333.85 (20074.95, 54597.45) |

|

| Q2 | 14267.10 (11581.20, 20473.65) |

25332.30 (14434.35, 37295.55)d |

17451.75 (11915.33, 28974.38) |

30970.95 (23208.15, 43562.25)c |

|

| Q3 | 22321.88 (13699.80, 34919.06)a |

26423.25 (20947.95, 34587.15) |

17622.90 (10012.91, 25435.61) |

22172.03 (17858.81, 30523.80)c |

|

| Q4 | 22240.13 (17265.94, 40798.43)b |

24933.15 (20305.73, 34210.13) |

15534.83 (11214.49, 23350.80) |

21397.13 (13059.49, 37083.53)c |

|

2.2. 不同总睾酮水平胰岛素和胰岛素曲线下面积变化

女性非黑棘皮病组中,随着总睾酮水平升高,胰岛素水平呈升高趋势。30、120 min的INS,在总睾酮Q4水平上较Q1升高(P < 0.05)。120 min的INS,在总睾酮Q3水平时,也出现升高(P < 0.05,图 1)。男性非黑棘皮病组中,随着总睾酮水平下降,胰岛素水平呈升高趋势。120、180 min的INS,在总睾酮Q1水平明显升高(Q1较Q4,P < 0.01)。女性和男性的黑棘皮病组较非黑棘皮病组的胰岛素总体水平升高,黑棘皮病组中INS在不同总睾酮水平均无明显统计学差异(图 2)。

黑棘皮病组女性和男性的AUC-INS较非黑棘皮病组总体水平升高。女性总睾酮在Q2水平时,黑棘皮病组AUC-INS较非黑棘皮病组AUC-INS明显增加(P < 0.01)。男性总睾酮在Q2-4水平时,黑棘皮病组AUC-INS均较非黑棘皮病组增加(P < 0.05)。非黑棘皮病组女性随着总睾酮升高,AUC-INS呈升高趋势。与非黑棘皮病患者Q1比较,AUC-INS在女性非黑棘皮病患者Q3升高(P < 0.05)、非黑棘皮病患者,Q4显著升高(P < 0.01)。非黑棘皮病组男性随着总睾酮下降,AUC-INS呈升高趋势。与非黑棘皮病患者,Q4比较,AUC-INS在男性非黑棘皮病患者,Q1升高(P < 0.05,表 1)。

2.3. 不同总睾酮水平胰岛素抵抗和胰岛素敏感性比较

在不同总睾酮水平,黑棘皮病男性和女性的HOMA-IR总体水平较非黑棘皮病组高(女性Q2组P < 0.05;男性Q1组P < .05,Q3-4组P < .01)。黑棘皮病组的WBISI平均水平总体低于非黑棘皮病对象(女性Q1,4均P < .05,Q2 P < .01;男性Q2,4均P < .01,Q3 Px 0.05);女性Q4较Q1明显下降(P < .05),男性Q1较Q4明显下降(P < .05)。女性及男性的黑棘皮病组IGI总体较非黑棘皮病组高(女性Q1 P < .05;男性Q3 P < 0.05)。女性及男性的黑棘皮病组HOMA-β较非黑棘皮病组总体升高,但仅在男性中有明显统计学差异(Q1-4组均P < .01)。提示黑棘皮病患者较非黑棘皮病患者胰岛素抵抗程度加重、胰岛素敏感性降低,同时胰岛细胞代偿功能也相应增强(表 2)。

2.

非黑棘皮病及黑棘皮病HOMA-IR、WBISI、IGI、HOMA-β比较

Comparison of HOMA-IR, WBISI, IGI and HOMA-β among male and female patients with NAN and AN

| Group | Female NAN | Female AN | Male NAN | Male AN |

| HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; IGI: The insulinogenic index; HOMA-β: Homoeostasis Model Assessment of β-cell function; WBISI: Whole body insulin sensitivity index. Compared with Q1 in female and compared with Q4 in male, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01. Compared with NAN quartile groupings, cP < 0.05, dP < 0.01. NAN: Non-acanthosis nigrican; AN: Acanthosis nigrican. | ||||

| n | 227 | 137 | 146 | 129 |

| Age (year) | 30.76±7.62 | 28.37±6.84 | 32.23±9.12 | 28.26±6.43 |

| HOMA-IR | ||||

| Q1 | 3.76 (2.69, 6.38) | 6.60 (5.56, 11.06) | 7.25 (4.98, 9.87) | 8.45 (7.01, 12.29)c |

| Q2 | 3.81 (2.70, 5.39) | 5.68 (4.35, 8.52)c | 5.60 (3.48, 8.69) | 8.01 (6.60, 10.57) |

| Q3 | 5.06 (3.22, 7.21) | 6.92 (5.09, 10.29) | 4.27 (2.77, 6.95) | 6.51 (4.71, 9.10)d |

| Q4 | 5.82 (3.94, 7.71) | 6.64 (4.50, 10.18) | 4.36 (3.02, 7.05) | 8.65 (6.29, 13.22)d |

| WBISI | ||||

| Q1 | 0.0239 (0.0115, 0.0418) |

0.0091 (0.0074, 0.017)c |

0.0114 (0.0056, 0.0247)a |

0.0073 (0.0043, 0.0122) |

| Q2 | 0.0272 (0.014, 0.0378) |

0.0114 (0.0071, 0.0207)d |

0.0166 (0.0091, 0.0326) |

0.0091 (0.0045, 0.0145)d |

| Q3 | 0.0139 (0.0077, 0.0308) |

0.0116 (0.007, 0.0159) |

0.0240 (0.0128, 0.0357) |

0.0138 (0.0098, 0.0193)c |

| Q4 | 0.0151 (0.0059, 0.0265)a |

0.0112 (0.0071, 0.0161)c |

0.0233 (0.0119, 0.0403) |

0.0103 (0.0071, 0.0161)d |

| IGI | ||||

| Q1 | 20.63 (11.84, 37.15) |

39.43 (16.09, 69.84)c |

23.23 (8.27, 48.00) |

36.24 (22.73, 48.97) |

| Q2 | 25.93 (12.82, 48.39) |

21.33 (14.86, 42.33) |

33.28 (12.52, 64.48) |

45.30 (15.01, 97.05) |

| Q3 | 27.69 (14.26, 41.59) |

35.95 (15.70, 46.47) |

32.24 (15.43, 42.64) |

39.25 (26.28, 53.63)c |

| Q4 | 36.94 (19.9, 53.98) |

42.52 (13.99, 61.81) |

22.56 (14.60, 40.41) |

30.72 (15.75, 43.25) |

| HOMA-β | ||||

| Q1 | 184.69 (117.56, 290.63) |

321.12 (194.06, 445.35) |

253.51 (117.36, 445.94) |

368.85 (290.43, 558.06)d |

| Q2 | 183.40 (130.03, 268.43) |

263.32 (173.22, 345.03) |

228.00 (107.27, 274.67) |

396.27 (291.79, 575.87)d |

| Q3 | 228.47 (170.09, 287.81) |

288.78 (197.37, 463.41) |

207.86 (142.44, 299.61) |

403.45 (209.85, 541.83)d |

| Q4 | 332.40 (187.49, 442.54) |

423.20 (211.75, 485.38) |

218.58 (115.81, 285.02) |

370.19 (198.65, 419.38)d |

3. 讨论

本研究发现,不同总睾酮水平时,黑棘皮病人群均较非黑棘皮病人群高胰岛素血症和胰岛素抵抗指数加重。有研究证实,雄激素主要与皮下脂肪的异位分布和肥大脂肪细胞功能异常相关,并不直接受到体脂总量影响,而这可能是雄激素调节胰岛素抵抗的关键因素[11]。女性雄激素水平异常升高可导致胰腺、肝脏、骨骼肌、脂肪等多个组织器官代谢紊乱,加重全身胰岛素抵抗的发生[12],刺激神经元[13]和胰岛β细胞雄激素受体激活,内质网应激加重,胰岛功能紊乱、高胰岛素血症和胰岛素抵抗加重[14]。而男性低睾酮水平时,胰岛细胞中的雄激素受体受到抑制,活性下降,脂肪积聚增加[15],同时减少肌肉中胰岛素敏感性的分子标记表达,增加内脏脂肪组织和肝脏脂肪变性,进一步促进胰岛素抵抗[14]。在雄激素作用下,胰岛素抵抗和高胰岛素血症相互加重、同时相互抑制,从而不断维持循环血糖水平保持相对稳定[16]。本研究发现,非黑棘皮病患者女性在总睾酮达Q4水平时胰岛素水平和AUC-INS出现明显升高、WBISI下降,而非黑棘皮病患者男性总睾酮低至Q1水平,AUC-INS出现明显升高、WBISI下降,推测在非黑棘皮人群中,女性总睾酮Q4水平、男性总睾酮Q1水平对胰岛素的影响更明显。提示总睾酮水平改变在非黑棘皮病患者中可促进高胰岛素血症、降低胰岛素敏感性,但只有总睾酮水平异常达到一定程度时,才会出现胰岛素水平和胰岛素敏感性改变的明显差异。

本研究证实,总睾酮在非黑棘皮肥胖和黑棘皮病患素抵抗稳态模型指数升高[21]。女性肥胖引起的全身性中对胰岛素抵抗的调节存在明显性别差异。女性肥胖炎症反应和β细胞损伤过程中,循环雄激素水平异常升引起的高胰岛素血症可以胰岛素和胰岛素样生长因子高、β细胞中过量的雄激素受体激活,可能导致β细胞功因其结构、序列和功能的高度同源性,高浓度胰岛素持能障碍[22]。而肥胖男性雄激素水平明显下降,可能是睾续升高可抢占胰岛素样生长因子的受体结合部位,抢先丸间质细胞和脂肪细胞分泌的瘦素和黄体生成素增多与胰岛素样生长因子受体结合,刺激女性卵巢分泌直接导致[23]。在肥胖引起的持续高胰岛素刺激下,雄激素结使血清性激素结合球蛋白水平下降,从而导致高雄激素合球蛋白结合力增强、黄体生成素脉冲幅度增加可导致血症[17]。黄体生成素和人绒毛膜促性腺激素在高胰岛男性雄激素水平下降[23]。女性循环雄激素升高是非生素状态下也可增加细胞因子水平,促进高雄激素血症的理性的,这种雄激素异常升高模式激活雄激素受体、促发生[18]。过量雄激素[19, 20]。植入双氢睾酮的雌性大鼠,进胰岛素分泌,而男性雄激素则可以是生理性减少,这高糖高雄激素刺激胰岛素分泌增加,胰岛氧化应激反应种接近正常范围的下调模式引起雄激素受体活性下降、增加了33%,线粒体功能紊乱,胰岛素敏感性下降,胰岛促进肥胖和胰岛素抵抗[14]。男性雄激素缺乏和女性雄激素过剩,分别通过雄激素受体缺乏或过量的作用产生代谢功能障碍[24]。这些可能是导致非黑棘皮患者男性和女性总睾酮呈反向改变时,均出现高胰岛素血症加重、胰岛细胞敏感性下降的主要原因。

本研究显示,与非黑棘皮病患者比较,IGI、HOMA-β在黑棘皮病男性和女性中总体水平升高,而HOMA-β在黑棘皮病男性患者的总睾酮各水平均有显著升高,提示黑棘皮病患较非黑棘皮病患者人群胰岛细胞功能增强,但黑棘皮病组人群未发现胰岛素抵抗和胰岛细胞功能指标随着总睾酮水平变化出现的显著性差异。我们推测,这是雄激素的“正负反馈”系统起到了某种调节作用。

去除雄激素受体的雄性小鼠出现迟发的总脂肪量和内脏脂肪量增加,表现出高脂联素血症,脂联素可增强胰岛素敏感性[25]。雄激素水平下降、雌二醇/睾酮比值增加,可有效增加糖尿病雄鼠β细胞数量[26],改善胰岛β细胞功能。基因组学层面的研究发现,雄激素可促进胰岛β细胞分化的关键基因表达,由此促进人诱导多能干细胞来源的胰岛β细胞分化率增加12%到35%[27]。胰岛中存在多种参与雄激素类固醇合成途径的关键蛋白,睾酮可以下调胰腺组织雄激素受体mRNA,提高胰岛素mRNA水平,促进胰岛素mRNA表达,减少胰岛细胞早期凋亡损伤[28]。也有研究认为胰腺中的雄激素可能以自分泌或旁分泌的方式作用于胰岛[29],直接作用于胰岛细胞提高胰岛细胞功能状态。肥胖的脂肪毒性所致的胰岛素抵抗和炎症因子激活也可抑制下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴,而低睾酮则进一步促进内脏脂肪团积累,加剧促性腺激素的抑制、睾丸分泌睾酮减少[30, 31]。这表明肥胖/超重的非黑棘皮病及黑棘皮病中雄激素存在正反馈调节作用。

另一方面,随着脂类分解减少、脂肪细胞增生肥大,引起胰岛素抵抗加重和雄激素变化程度增加,雄激素对胰岛细胞功能的某种“负反馈”调整系统也开始启动。有最新研究发现,男性发生胰岛素抵抗时的睾酮下限较胰岛素敏感男性降低了2.29 nmol/L[32]。表明雄激素在一定水平时发生胰岛素抵抗和促进胰岛素细胞功能的作用才更加明显。有分析推测,男性雄激素不足的程度达到中度水平时,加重胰岛素抵抗的作用才明显,而此时胰岛β细胞的分泌功能尚可维持在一定水平;当雄激素不足达到严重程度时,胰岛素抵抗和β细胞功能衰退才比较明显[14]。一项新的研究表明雄激素可通过雄激素受体对胰岛素抵抗产生改善和加重相反作用,这证实了我们的假设。健康男性雄激素受体的CAG少量重复与低体脂肪含量、低血浆胰岛素独立相关[33]。雄激素受体外显子CAG重复序列CAG长于23时,睾酮的增加表现出改善胰岛素抵抗的作用,而长度不足23时,游离睾酮增加可抑制胰岛素敏感性、加重胰岛素抵抗[34]。进一步的研究证实了我们的推论。高糖培养基中INS-1细胞培养72 h,睾酮(浓度0.05~0.5 μg/mL)显著降低INS-1细胞死亡率,但低浓度和高浓度睾酮的却不显示该保护作用[35]。

本研究尚存在一些不足之处,需要进一步扩大样本量,需对于不同年龄阶段、不同体质量人群进一步分层分析,并增加游离睾酮、性激素结合球蛋白等水平,尚需针对性地深入分析和探讨。

Biography

张玲,在读博士研究生,主治医师,E-mail: flyingfish-lu@163.com

Funding Statement

国家科技部重点研发计划(2018YFC1314100);国家自然科学基金(81970677);申康三年行动计划(SHDC2020CR1017B);上海市医药卫生发展基金会糖尿病临床研究项目(I期07研究)

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970677)

Contributor Information

张 玲 (Ling ZHANG), Email: flyingfish-lu@163.com.

林 紫薇 (Ziwei LIN), Email: lin_ziwei225@163.com.

曲 伸 (Shen QU), Email: qushencn@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/41/Supplement_1/S13.full-text.pdf. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S15–33. doi: 10.2337/dc21-ad09. [American Diabetes Association. 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2021[J]. Diabetes Care, 2021, 44(suppl 1): S15-33.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Álvarez-Villalobos NA, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R, González-Saldivar G, et al. Acanthosis nigricans in middle-age adults: a highly prevalent and specific clinical sign of insulin resistance. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijcp.13453. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(3):e13453. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13453. [Álvarez-Villalobos NA, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R, González-Saldivar G, et al. Acanthosis nigricans in middle-age adults: a highly prevalent and specific clinical sign of insulin resistance[J]. Int J Clin Pract, 2020, 74(3): e13453.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermanns-Lê T, Scheen A, Piérard GE. Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin resistance: pathophysiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5(3):199–203. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405030-00008. [Hermanns-Lê T, Scheen A, Piérard GE. Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin resistance: pathophysiology and management[J]. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2004, 5(3): 199-203.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popa ML, Popa AC, Tanase C, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: To be or not to be afraid. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30944606. Oncol Lett. 2019;17(5):4133–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9736. [Popa ML, Popa AC, Tanase C, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: To be or not to be afraid[J]. Oncol Lett, 2019, 17(5): 4133-8.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans syndrome: a common endocrinopathy with distinct pathophysiologic features. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6351620. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;147(1) doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90091-1. [Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans syndrome: a common endocrinopathy with distinct pathophysiologic features[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1983, 147(1): .] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor SR, Meadowcraft LM, Williamson B. Prevalence, pathophysiology, and management of androgen deficiency in men with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or both. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(8):780–92. doi: 10.1002/phar.1623. [Taylor SR, Meadowcraft LM, Williamson B. Prevalence, pathophysiology, and management of androgen deficiency in men with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or both[J]. Pharmacotherapy, 2015, 35(8): 780-92.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuart CA, Peters EJ, Prince MJ, et al. Insulin resistance with acanthosis nigricans: The roles of obesity and androgen excess. Metabolism. 1986;35(3):197–205. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90201-5. [Stuart CA, Peters EJ, Prince MJ, et al. Insulin resistance with acanthosis nigricans: The roles of obesity and androgen excess[J]. Metabolism, 1986, 35(3): 197-205.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyes-Muñoz E, Ortega-González C, Martínez-Cruz N, et al. Association of obesity and overweight with the prevalence of insulin resistance, pre-diabetes and clinical-biochemical characteristics among infertile Mexican women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e012107. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012107. [Reyes-Muñoz E, Ortega-González C, Martínez-Cruz N, et al. Association of obesity and overweight with the prevalence of insulin resistance, pre-diabetes and clinical-biochemical characteristics among infertile Mexican women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMJ Open, 2016, 6(7): e012107.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.钱 春花, 朱 翠玲, 高 晶扬, et al. 青年男性黑棘皮病患者性激素的变化和机制探讨. 中华内分泌代谢杂志. 2018;34(5):383–8. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1000-6699.2018.05.005. [钱春花, 朱翠玲, 高晶扬, 等. 青年男性黑棘皮病患者性激素的变化和机制探讨[J]. 中华内分泌代谢杂志, 2018, 34(5): 383-8.] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke JP, Hale DE, Hazuda HP, et al. A quantitative scale of acanthosis nigricans. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(10):1655–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.10.1655. [Burke JP, Hale DE, Hazuda HP, et al. A quantitative scale of acanthosis nigricans[J]. Diabetes Care, 1999, 22(10): 1655-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammarstedt A, Gogg S, Hedjazifar S, et al. Impaired adipogenesis and dysfunctional adipose tissue in human hypertrophic obesity. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(4):1911–41. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2017. [Hammarstedt A, Gogg S, Hedjazifar S, et al. Impaired adipogenesis and dysfunctional adipose tissue in human hypertrophic obesity[J]. Physiol Rev, 2018, 98(4): 1911-41.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez-Garrido MA, Tena-Sempere M. Metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathogenic role of androgen excess and potential therapeutic strategies. Mol Metab. 2020;35:100937. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.01.001. [Sanchez-Garrido MA, Tena-Sempere M. Metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathogenic role of androgen excess and potential therapeutic strategies[J]. Mol Metab, 2020, 35: 100937.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navarro G, Allard C, Morford JJ, et al. Androgen excess in pancreatic β cells and neurons predisposes female mice to type 2 diabetes. JCI Insight. 2018;3(12):e98607. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98607. [Navarro G, Allard C, Morford JJ, et al. Androgen excess in pancreatic β cells and neurons predisposes female mice to type 2 diabetes[J]. JCI Insight, 2018, 3(12): e98607] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):267–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes[J]. Nat Genet, 2003, 34(3): 267-73.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu WW, Morford J, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Emerging role of testosterone in pancreatic β cell function and insulin secretion. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30601759. J Endocrinol. 2019:JOE-18-0573. doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0573. [Xu WW, Morford J, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Emerging role of testosterone in pancreatic β cell function and insulin secretion[J]. J Endocrinol, 2019: JOE-18-0573.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. http://www.onacademic.com/detail/journal_1000034860337210_7a29.html. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S16–S21. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s16. [Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes[J]. Diabetes, 2004, 53(Suppl 3): S16-S21.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nestler JE, Powers LP, Matt DW, et al. A direct effect of hyperinsulinemia on serum sex hormone-binding globulin levels in obese women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72(1):83–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-1-83. [Nestler JE, Powers LP, Matt DW, et al. A direct effect of hyperinsulinemia on serum sex hormone-binding globulin levels in obese women with the polycystic ovary syndrome[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1991, 72(1): 83-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasquali R, Vicennati V, Gambineri A. Adrenal and gonadal function in obesity. J Endocrinol Investig. 2002;25(10):893–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03344053. [Pasquali R, Vicennati V, Gambineri A. Adrenal and gonadal function in obesity[J]. J Endocrinol Investig, 2002, 25(10): 893-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. http://press.endocrine.org/doi/pdf/10.1210/edrv.18.6.0318. Endocr Rev. 1997;18(6):774–800. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.6.0318. [Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis[J]. Endocr Rev, 1997, 18(6): 774-800.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rager KM, Omar HA. Androgen excess disorders in women: the severe insulin-resistant hyperandrogenic syndrome, HAIR-黑棘皮病患者. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:116–21. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.23. [Rager KM, Omar HA. Androgen excess disorders in women: the severe insulin-resistant hyperandrogenic syndrome, HAIR-黑棘皮病患者[J]. ScientificWorldJournal, 2006, 6: 116-21.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra JS, More AS, Kumar S. Elevated androgen levels induce hyperinsulinemia through increase in Ins1 transcription in pancreatic beta cells in female rats. Biol Reprod. 2018;98(4):520–31. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy017. [Mishra JS, More AS, Kumar S. Elevated androgen levels induce hyperinsulinemia through increase in Ins1 transcription in pancreatic beta cells in female rats[J]. Biol Reprod, 2018, 98(4): 520-31.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogen and androgen receptors: regulators of fuel homeostasis and emerging targets for diabetes and obesity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.002. [Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogen and androgen receptors: regulators of fuel homeostasis and emerging targets for diabetes and obesity[J]. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 22(1): 24-33.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima N, Cavaliere H, Knobel M, et al. Decreased androgen levels in massively obese men may be associated with impaired function of the gonadostat. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(11):1433–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801406. [Lima N, Cavaliere H, Knobel M, et al. Decreased androgen levels in massively obese men may be associated with impaired function of the gonadostat[J]. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 2000, 24(11): 1433-7.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navarro G, Allard C, Xu W, et al. The role of androgens in metabolism, obesity, and diabetes in males and females. Obesity: Silver Spring. 2015;23(4):713–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.21033. [Navarro G, Allard C, Xu W, et al. The role of androgens in metabolism, obesity, and diabetes in males and females[J]. Obesity: Silver Spring, 2015, 23(4): 713-9.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan W, Yanase T, Nomura M, et al. Androgen receptor null male mice develop late-onset obesity caused by decreased energy expenditure and lipolytic activity but show normal insulin sensitivity with high adiponectin secretion. Diabetes. 2005;54(4):1000–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1000. [Fan W, Yanase T, Nomura M, et al. Androgen receptor null male mice develop late-onset obesity caused by decreased energy expenditure and lipolytic activity but show normal insulin sensitivity with high adiponectin secretion[J]. Diabetes, 2005, 54 (4): 1000-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inada A, Inada O, Fujii NL, et al. Β-cell induction in vivo in severely diabetic male mice by changing the circulating levels and pattern of the ratios of estradiol to androgens. Endocrinology. 2014;155(10):3829–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1254. [Inada A, Inada O, Fujii NL, et al. Β-cell induction in vivo in severely diabetic male mice by changing the circulating levels and pattern of the ratios of estradiol to androgens[J]. Endocrinology, 2014, 155(10): 3829-42.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Guo D, Ruzi A, et al. Testosterone improves the differentiation efficiency of insulin-producing cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179353. [Liu H, Guo D, Ruzi A, et al. Testosterone improves the differentiation efficiency of insulin-producing cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(6): e0179353.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morimoto S, Morales A, Zambrano E, et al. Sex steroids effects on the endocrine pancreas. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;122(4):107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.05.003. [Morimoto S, Morales A, Zambrano E, et al. Sex steroids effects on the endocrine pancreas[J]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2010, 122 (4): 107-13.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blouin K, Veilleux A, Luu-The V, et al. Androgen metabolism in adipose tissue: recent advances. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ShoppingCartURL&_method=add&_eid=1-s2.0-S0303720708005030&originContentFamily=serial&_origin=article&_ts=1433103238&md5=489794ffdfe081d717ba7f61df077c06. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;301(1/2) doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.035. [Blouin K, Veilleux A, Luu-The V, et al. Androgen metabolism in adipose tissue: recent advances[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2009, 301 (1/2): .] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mah PM, Wittert GA. Obesity and testicular function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316(2):180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.06.007. [Mah PM, Wittert GA. Obesity and testicular function[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2010, 316(2): 180-6.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossmann M. Low testosterone in men with type 2 diabetes: significance and treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(8):2341–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0118. [Grossmann M. Low testosterone in men with type 2 diabetes: significance and treatment[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 96 (8): 2341-53.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mezzullo M, Di Dalmazi G, Fazzini A, et al. Impact of age, body weight and metabolic risk factors on steroid reference intervals in men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;182(5):459–71. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0928. [Mezzullo M, Di Dalmazi G, Fazzini A, et al. Impact of age, body weight and metabolic risk factors on steroid reference intervals in men[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2020, 182(5): 459-71.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zitzmann M, Gromoll J, von Eckardstein A, et al. The CAG repeat polymorphism in the androgen receptor gene modulates body fat mass and serum concentrations of leptin and insulin in men. Diabetologia. 2003;46(1):31–9. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0980-9. [Zitzmann M, Gromoll J, von Eckardstein A, et al. The CAG repeat polymorphism in the androgen receptor gene modulates body fat mass and serum concentrations of leptin and insulin in men[J]. Diabetologia, 2003, 46(1): 31-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Möhlig M, Arafat AM, Osterhoff MA, et al. Androgen receptor CAG repeat length polymorphism modifies the impact of testosterone on insulin sensitivity in men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(6):1013–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1022. [Möhlig M, Arafat AM, Osterhoff MA, et al. Androgen receptor CAG repeat length polymorphism modifies the impact of testosterone on insulin sensitivity in men[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2011, 164(6): 1013-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanchang W, Semprasert N, Limjindaporn T, et al. Testosterone protects against glucotoxicity-induced apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells (INS- 1) and male mouse pancreatic islets. Endocrinology. 2013;154(11):4058–67. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1351. [Hanchang W, Semprasert N, Limjindaporn T, et al. Testosterone protects against glucotoxicity-induced apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells (INS- 1) and male mouse pancreatic islets[J]. Endocrinology, 2013, 154(11): 4058-67.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]