Abstract

Background

Risk factors for child maltreatment have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially due to economic downfalls leading to parental job losses and poor mental health.

Objective

This study aimed to examine the association between child maltreatment and unemployment rate in the Republic of Korea.

Participants and setting

Nationally representative data at the province level were used.

Methods

The monthly excess number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic was estimated for each province. Fixed effects regressions was used to examine the relationship between the excess number of hotline calls and unemployment rate.

Results

The average excess number of hotline calls was significantly negative in the early stage of the pandemic, but became significantly positive afterwards except for some months with averages not statistically different from zero. The regression results showed that an increase of male unemployment rate by 1% was significantly associated with an increase in the excess number of hotline calls by 0.15—0.17 per 10,000 children for most dependent variables for the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The statistical significance of female unemployment rate was mixed with the opposite sign of the coefficient to that of male unemployment. Overall unemployment rate was not significant.

Conclusions

This study suggests that disruptions in child welfare services should be avoided to prevent underreporting of or delayed responses to suspected cases. Also, policies need to be designed considering potential pathways from economic downfalls, especially male unemployment, to child maltreatment.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, COVID-19, Hotline call, Job loss, Unemployment

1. Introduction

Violence against children is a global health issue with long-term effects. Longitudinal studies show how experiences of maltreatment in childhood affected behaviors in adulthood. For instance, Jonson-Reid et al. analyzed data following more than 3000 children in the United States (US) for 15 years and showed that chronic child maltreatment was significantly associated with perpetration of child maltreatment and poor mental health in adulthood (Jonson-Reid et al., 2012). Another study by Skinner et al. examined survey data of around 300 children followed for more than 30 years in the US and showed that physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in childhood had direct and indirect effects on mental health and behavioral problems such as alcohol and substance use in adolescence and adulthood (Skinner et al., 2016).

Although research on the impact of unexpected crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic on child maltreatment has not been done much, existing studies show that child maltreatment increased during crises such as natural disaster, disease epidemic, and economic recession. For instance, Keenan et al. showed that inflicted traumatic brain injury, a common form of child abuse during the first year of life, increased five times in the first six months in affected areas by Hurricane Floyd in the US, whereas it stayed almost the same in unaffected areas (Keenan et al., 2004). Anecdotal evidence from past epidemics indicates that the risk of violence against women and girls increased during the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sierra Leone (UKAID 2020) (Fraser, 2020). Also, some studies show that child maltreatment increased during the Great Recession in US in 2007—2009. Berger et al. showed that the rate of abusive head trauma among children younger than five years increased significantly during the economic recession as compared to the pre-recession period (Berger et al., 2011). Schneider et al. examined panel data of families in 20 US cities for the periods before, during, and after the Great Recession and showed that an increase in child abuse and neglect was significantly associated with the economic recession, controlling for individual economic and mental health status (Schneider et al., 2017).

Diverse risk factors contributing to child abuse and neglect have been studied (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014). At the individual and family levels, parental characteristics such as mental health and experiences of abuse and neglect in their childhood have been identified as risk factors. For instance, Dubowitz et al. examined panel data of 332 low-income families followed for more than a decade in the US and found that two out of five statistically significant risk factors for child maltreatment were related to parental mental health such as depression and drug use (Dubowitz et al., 2011). Widom et al. analyzed data of more than 600 individuals and their offspring followed for 30 years in the US and showed that children of parents who suffered abuse and neglect in their childhood were more likely to be exposed to neglect and sexual abuse (Widom et al., 2015). Coulton et al. examined panel data for 475 census tracts over the period 1990—2010 in the US and found that a high share of single parent families is one of strongly associated risk factors with child maltreatment (Coulton et al., 2018). Another study by Ahmadabadi et al. examined longitudinal data of 2064 mothers and children in Australia for more than a decade and found that children whose mothers were victimized by their male partners were more likely to experience physical and mental abuse (Ahmadabadi et al., 2018).

At the community and societal level, risk factors include neighborhood characteristics, especially poverty and unemployment. Farrell et al. analyzed national representative data including child abuse fatalities and population statistics for the period 1999—2014 in the US and found that children living in counties with the highest poverty concentration were significantly associated with a higher rate of child abuse fatalities as compared to counties with the lowest poverty concentration (Farrell et al., 2017). A study by Morris et al. using data for 31 zip codes over the period 2011—2014 in the US showed that poverty was associated with an increased risk of all child maltreatment subtypes, and unemployment rate was associated with child neglect (Morris et al., 2019). Schneider et al. showed that economic uncertainty, measured by unemployment rate and the Consumer Sentiment Index, was a significant risk factor for child abuse and neglect (Schneider et al., 2017). There were few studies that examined the relationship between child maltreatment and unemployment by gender. Cherry and Wang used male unemployment rate as an indicator of labor market conditions that can affect adult male behavior and showed that child maltreatment was significantly associated with a decrease in the employment rate of men aged 20 to 34 at the state level in the US over the period 2000—2012 (Cherry & Wang, 2016). Lindo, Schaller, and Hansen examined the relationship between labor market conditions and child maltreatment at the county level in US for the period 1998—2012 and found strong evidence that child maltreatment decreased as male employment increased, and by contrast, it increased as female employment increased (Lindo et al., 2018).

Recent studies have shown that some risk factors for child maltreatment have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. As lockdown measures were intensified, economic activities have been restricted, leading to income loss and unemployment for many people. Restrictions on mobility and economic downfalls have deteriorated people's mental health. For instance, Wong et al. showed in a study using survey data of 600 parents in Hong Kong that the current pandemic led to parental income reduction and job loss, thereby significantly increasing the risk of physical abuse of their children (Wong et al., 2021). Lee et al. examined survey data of 283 adults living in the US and showed that the COVID-19 pandemic increased parents' perceived social isolation and employment loss, leading to neglect and verbal aggression toward their children (Lee et al., 2021). Although data are scarce, media and reports from governments and organizations showed that intimate partner violence increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a risk factor for child maltreatment. For instance, Zhang showed that police reports on family violence cases, mostly toward women, has increased by double to triple in some rural areas in China during the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to the same period in 2019 (Zhang, 2020). A news article reported that the number of women who died from domestic abuse during intensive lockdown was double the average over the last ten years in the United Kingdom (Grierson, 2020).

In this study, unemployment rate – overall and by gender – was focused as a risk factor for child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Korea (Korea afterwards). Particularly, this study assessed if there was an increase in child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to previous four years and then evaluated whether unemployment was associated with child maltreatment using fixed effects regressions.

2. Background

In Korea, child maltreatment is defined as physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect and abandonment, and any other cruel acts and harms toward children that impede childhood health and welfare under the Child Welfare Act (Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2018). In the national child protection system, Child Protection Centers play a central role. The hotline for reporting suspected child maltreatment cases was integrated to the 24-hour police hotline (112) in 2014, thereby strengthening the role of the police in dealing with suspected cases. In regards to the operational process, when a suspected case is reported through the hotline or other channels such as calls to Child Protection Centers, a staff from a Child Protection Center designated to a reported area takes an immediate action with a police to investigate the case, usually starting from visiting a home. Depending on the decision on the degree of risks and harms posed to the child, different levels of protective and legal measures are taken including referrals to community child welfare centers, provision of mental health services, and out-of-home placement under the court protection order (Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2018; Lee, 2019). Annual reports show that the national average of child maltreatment cases increased from 2.14 to 4.01 per 1000 children from 2016 to 2020 (Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency, 2019, Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency, 2020, Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency, 2021). The average share of actual cases out of total reported cases via the hotline and other channels is 68.4% (standard deviation [SD] =4.4%) over the period 2016—2020.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Korean government has expanded existing unemployment benefits and introduced new subsidy programs to support unemployed people, which might have mitigated potential negative impacts on child maltreatment (Ministry of Employment and Labor, 2020, Ministry of Employment and Labor, 2021). The government has expanded the existing Employment Success Package Program that provides comprehensive supports including financial allowances and training in a phased manner to low-income households and the unemployed youth and elderly. The government has also eased the eligibility for Livelihood Support Loan that provides loans without collateral at a low interest rate to low-income households. Also for reaching out to people who are not covered by the national employment insurance, the government has introduced two support programs – one implemented by local governments (Special Support Program for Regional Employment) and another by the central government (Emergency Employment Stability Subsidy) – that aims at providing financial supports and counseling services to vulnerable people such as self-employed and micro-businesses owners.

3. Methods

3.1. Data

Table 1 lists dataset used for analysis. Data were nationally representative and available at the province level, which is the first administrative boundaries composed of seven major cities and nine provinces. In 2019, there was a change in the administrative boundaries, so that one city (Sejong) was excluded from a province and added as a major city. However, in this study, the city was kept in the province to which it previously belonged for the consistency of dataset before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Data and sources.

| Variable | Frequency | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Child maltreatment | ||

| Hotline (112) calls related to child maltreatment | Monthly (Feb 2016—Mar 2021) | National Police Agency, 2021 |

| 2. Unemployment | ||

| Unemployment rate, total | Monthly (Feb 2020—Mar 2021) | Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2021a |

| Unemployment rate, female | Monthly (Feb 2020—Mar 2021) | |

| Unemployment rate, male | Monthly (Feb 2020—Mar 2021) | |

| 3. Restrictions on mobility | ||

| Proportional change in mobile-based mobility per capita as compared to the same month in 2019 | Monthly (Feb 2020—Mar 2021) | Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2021b |

| 4. Population | ||

| Population, total | Yearly (2020, 2021) | Ministry of the Interior and Safety, 2021 |

| Child population, 0–17 years old | Yearly (2020, 2021) |

3.2. Outcome variable

This study used the monthly number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment as a proxy for child maltreatment cases for each province. This is because the number of actual cases was not available at the monthly basis, instead made available as yearly aggregated numbers in the following year. Monthly data were needed considering the COVID-19 pandemic had been evolving quickly, which led to frequent changes in restrictions on mobility, thereby affecting unemployment rate and the risk of child maltreatment.

As the outcome variable, the excess monthly number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children was calculated for the period of COVID-19 pandemic as compared to previous years. First, the time period was divided into the pre- and the during-COVID period: from February 2016 to December 2019 and from February 2020 to March 2021, respectively, considering the first case was confirmed in late January 2020. Data on monthly hotline calls related to child maltreatment were available from February 2016 onwards. Second, the monthly number of hotline calls was divided by child population aged 0—17 and multiplied by 10,000. Third, to quantify the historical time trend in hotline calls before the COVID-19 started, a simple linear regression was run for the pre-COVID period in which the number of hotline calls per 10,000 children was a linear function of year for each month at the province level as following:

where calls y∣m, prov is the number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children in year y for a given month m in province prov for the pre-COVID period, and e y∣m, prov is residual. Fourth, using the simple linear regression, the number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children was predicted for a corresponding month for each province for the during-COVID period. Fifth, the gap between the predicted and the actual number of hotline calls per 10,000 children was calculated as the monthly excess number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment at the province level for the during-COVID period.

Three alternative outcomes were also examined. The first one was calculated with the same procedure based on the linear time trend except that the pre-COVID period was restricted to three years of 2017—2019. Other two alternatives were calculated as the gaps between the actual number of hotline calls and the monthly average of hotline calls over two different periods: 2016—2019 and 2017—2019.

3.3. Independent variables

For regressions, main independent variables of interest were monthly overall, female, and male employment rates at the province level. The monthly intensity of restrictions on mobility was included as another independent variable to control for its association with channels for spotting and reporting child abuse and neglect. For instance, restriction measures have led to the closure schools and preschools and disruptions in at-risk household visit programs, and in turn it has precluded spotting child maltreatment cases. To measure the intensity of restrictions on mobility, this study used the proportional change in mobility per capita as compared to the same month in 2019 for each province. For the early period from February to May 2020, the data was available only at the national level. To impute missing values at the province level, we applied the month-to-month proportional change of the national-level data from February to June 2020 to each province. For easy interpretation as restriction measures, minus one was multiplied to mobility per capita. Time-invariant and time-varying (yearly) province-specific characteristics that were potentially related to child maltreatment were controlled for in regressions using fixed effects.

3.4. Regressions

Fixed effects ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for panel data were performed to quantify the relationship between the excess number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment and unemployment rates controlling for restrictions on mobility, province-specific characteristics, and time effects. Regressions were run for the four alternative dependent variables. Two cases for unemployment rate were examined: model 1 with overall unemployment rate and model 2 with female and male unemployment rates.

Model 1 is as following:

where excess calls prov, y, m is the number of excess hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children for province prov, year y, and month m for the during-COVID period. unemp prov, y, m−1 is the overall unemployment rate, and mobil_restrict prov, y, m−1 is the intensity of restrictions on mobility. These two variables were lagged by one month considering there may be a time gap from changes in unemployment rates and restriction measures to spotting and reporting child maltreatment cases. δ prov is province fixed effects that control for time-invariant province-specific characteristics that may be correlated with child maltreatment. δ prov, y is province-year fixed effects or province-specific linear time trends that control for time-variant (yearly) province-specific characteristics potentially related to child maltreatment. δ y and δ y, m are time fixed effects at the yearly and monthly level, respectively. Lastly, e prov, y, m is residual. Clustered robust (White-Huber) standard error estimation was used, treating provinces as clusters.

Model 2 is as following:

where female_unemp prov, y, m−1 and male_unemp prov, y, m−1 are female and male unemployment rate, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

4.1.1. Dependent variable

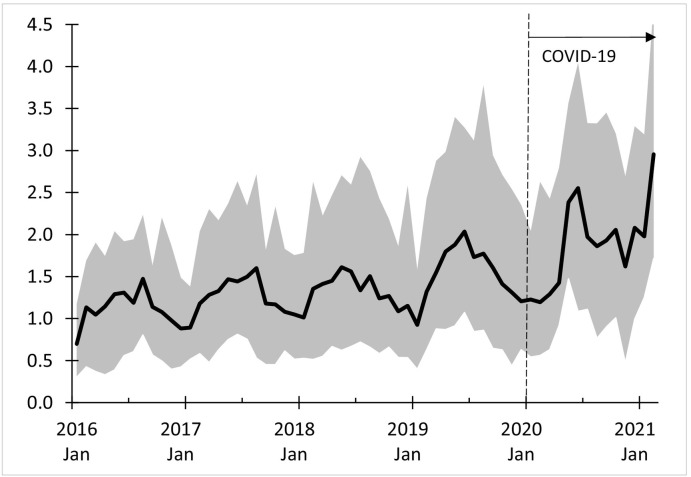

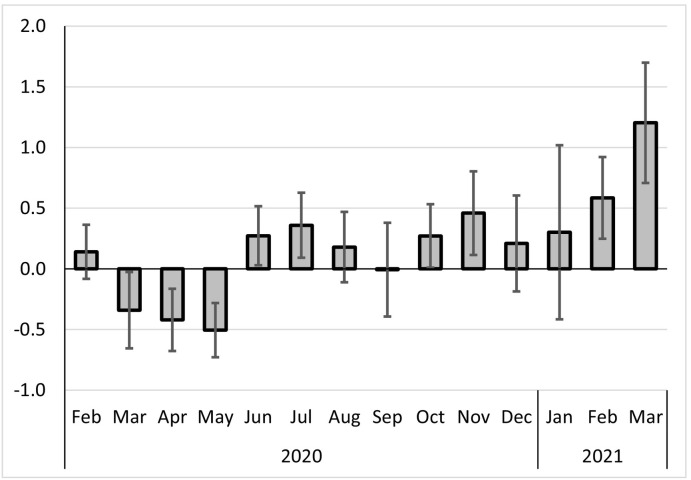

Fig. 1 shows the nationwide monthly number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children over the period February 2016 to March 2021. It shows that the number of hotline calls has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic which started in late January 2020 as compared to the previous years. Table 2 shows that the average excess number of hotline calls was 0.19 per 10,000 children (SD = 0.78). Fig. 2 shows that the average excess number of hotline calls was significantly negative in the early stage of the pandemic from March to May 2020 and became significantly positive afterwards except for some months with averages not statistically different from zero.

Fig. 1.

Nationwide hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children, February 2016—March 2021.

Note: The solid line shows nationwide hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children aged 0—17 years from February 2016 to March 2021. The shaded area presents 2.5th percentile to 97.5th percentile in monthly hotline calls at the province level.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables at the province level for the during-COVID period of February 2020—March 2021.

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | N | Province | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Excess hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children | 0.19 | 0.78 | −3.31 | 2.79 | 224 | 16 | 14 (months) |

| 2. Unemployment | |||||||

| Unemployment rate (%), total | 3.91 | 1.15 | 1.30 | 8.80 | 224 | 16 | 14 |

| Unemployment rate (%), female | 4.02 | 1.54 | 0.90 | 12.70 | 224 | 16 | 14 |

| Unemployment rate (%), male | 3.82 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 6.10 | 224 | 16 | 14 |

| 3. Restrictions on mobility (%)a | 10.22 | 10.28 | −22.20 | 44.10 | 224 | 16 | 14 |

| 4. Population | |||||||

| Population, total | 3,213,082 | 3,354,885 | 673,974 | 13,500,000 | 32 | 16 | 2 (years) |

| Child population, 0–17 years old | 474,673 | 513,188 | 116,037 | 2,190,957 | 32 | 16 | 2 |

Note. SD = standard deviation; N = total observations.

For easy interpretation, minus one was multiplied to proportional change in mobility per capita as compared to the same month in 2019.

Fig. 2.

Excess hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: The bars show the averages of the province-level excess hotline calls. The ranges present the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For 95% CIs, t-value was used considering the small same size (16 provinces): 95% CI = average ± t(SD/4), t = 2.131 (df = 16–1). SD = standard deviation.

4.1.2. Independent variables

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of independent variables. Average monthly unemployment rate was 3.91% (SD = 1.15%) for the during-COVID period. Average female unemployment rate was higher than male unemployment rate at 4.02% (1.54%) as compared to 3.82% (1.07%) for the same period. Average mobility per person decreased by 10.22% (10.28%) during the pandemic as compared to the pre-COVID period.

4.2. Regressions

Table 3 shows the regression results. The level of 5% was used for being statistically significant; and that of 10%, for being slightly significant.

Table 3.

Regression results.

| Dependent variable |

The monthly excess number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment per 10,000 children measured based on: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time trend over 2016—2019 |

Time trend over 2017—2019 |

Average over 2016—2019 |

Average over 2017—2019 |

|

| Coef (SE) | Coef (SE) | Coef (SE) | Coef (SE) | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Unemployment rate (%), overall | 0.07 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.12) | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.06) |

| Mobility restrictions (%, reference: 2019) | −1.40 (0.73)⁎ | −1.82 (0.87)⁎ | −0.83 (0.53) | −0.87 (0.52) |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Unemployment rate (%), female | −0.10 (0.06) | −0.13 (0.08) | −0.10 (0.04)⁎⁎ | −0.10 (0.03)⁎⁎ |

| Unemployment rate (%), male | 0.17 (0.08)⁎⁎ | 0.16 (0.09)⁎ | 0.15 (0.06)⁎⁎ | 0.15 (0.06)⁎⁎ |

| Mobility restrictions (%, reference: 2019) | −1.22 (0.74) | −1.61 (0.89)⁎ | −0.66 (0.54) | −0.70 (0.55) |

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province-year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-month | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 224 | 224 | 224 | 224 |

| Provinces | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| N per province | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

Coef = coefficient; SE = standard errors; N = total observations.

Significant at 5% level.

Significant at 10% level.

In the model 1, the overall unemployment rate was not significant for all the alternative dependent variables. Mobility restrictions was slightly significant for the dependent variables measured based on the historical time trend and insignificant for those based on the historical average.

In the model 2, male unemployment rate was statistically significant for three out of four alternative dependent variables. For the remaining one, which is based on the time trend over 2017—2019, male unemployment rate was slightly significant. An increase in male unemployment rate by 1% was associated with an increase in the excess number of hotline calls by 0.15—0.17/10,000 children. Female unemployment had a negative coefficient which is the opposite to male unemployment. It was significant for the dependent variables calculated using the historical averages, showing that an increase in female unemployment rate by 1% was associated with a decrease in the excess number of hotline calls by 0.10/10,000 children. However, it was not significant for the dependent variables measured based on the historical time trends. Restrictions on mobility was not significant for most dependent variables.

The assumptions of OLS regressions were examined (Hayashi, 2011). First, to test the linearity between the excess number of hotline calls and independent variables, Pregibon test was conducted. For all the regression models, the linearity could not be rejected at the significance level of 5%. Second, the normality of error terms was examined using visual methods, the frequency distribution of residuals, P—P plot, and Q-Q plot. All graphs showed that the distributions of residuals were similar to the normal distribution in general. Also, for an enough sample size such as in this study, the normality is not a major concern according to the central limit theorem. Third, to avoid biases in standard errors due to heteroscedasticity, clustered robust (White-Huber) standard error estimation was used (Hoechle, 2007). Fourth, in regards to strict exogeneity, to minimize biases in OLS estimators due to omitted variables that are potentially related to child maltreatment, four fixed effects were included to control for time-invariant and time-varying (yearly) province-specific characteristics and year and year-month effects. Also, to obtain unbiased standard errors under autocorrelation, clustered robust (White-Huber) standard error estimation was used. Lastly, multicollinearity among explanatory variables was tested using the pairwise correlation matrixes. There was no correlations above 0.7 among explanatory variables of interest, which suggests an absence of multicollinearity. Details on post-estimations are presented in Appendix A.

5. Discussion

To examine the relationship between child maltreatment and unemployment during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea, this study measured the excess number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment as compared to the pre-COVID period. The results showed that the excess number of calls was significantly negative in the early stage from March to June 2020 but became significantly positive afterwards for the majority of the following months. The fixed effects regressions showed that in relation to the excess number of hotline calls, overall unemployment rate was insignificant; male unemployment was significant for three alternative dependent variables out of four and slightly significant for the remaining one; and female unemployment had the opposite sign to male unemployment and was significant for the dependent variables based on the historical average but insignificant for those based on the historical time trend.

The significant falls in the excess number of hotline calls in the early stage of the pandemic can be related to intensive restriction measures on mobility, which led to school closures and disruptions in child welfare services. Specifically, in the first-half of 2020, the beginning of the school semester was delayed and classes were replaced by online teaching in most schools, thereby opportunities for teachers to identify child maltreatment cases declined. Also, at-risk household visits have decreased or replaced by investigation through phone calls due to the increase of COVID-19 cases. Disruptions or changes in child protection services during the COVID-19 pandemic have been often observed in developing and developed countries (Katz et al., 2021).

Although few studies have been conducted to examine the associations between child maltreatment and unemployment by gender as described in the Introduction, the findings of this study are consistent with the previous studies in that an increase in male unemployment is significantly associated with an increase in the risk of child maltreatment (Cherry & Wang, 2016; Lindo et al., 2018).

In regards to causal paths from unemployment, particularly male unemployment, to child maltreatment, studies on risk factors for child maltreatment and the relationship of unemployment and child maltreatment described in the Introduction suggest potential mechanisms to some degree. At the individual and family level, unemployment may worsen parental mental health, leading to depression and substance abuse, which is a risk factor for child maltreatment. Also unemployment may increase intimate partner violence and divorce, thereby worsening risk factors within the family. However, these causal paths may apply to all people who suffer economic shocks regardless of gender. With respect to different mechanisms by gender, Lindo, Schaller, and Hansen suggested a framework to explain the relationship between child maltreatment and female and male unemployment (Lindo et al., 2018). In the framework, men were assumed to be more prone to perpetrate child maltreatment than women; therefore, unemployment shock on father increases the time that children spend with a person with a higher propensity for child maltreatment. The authors supported the assumption with a survey result that 62% of perpetrators were male in the US according to the National Incidence Study despite substantially less time that males spend with their children as compared to females (Sedlak et al., 2010). This survey result is consistent with annual national surveys in Korea (Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency, 2019, Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency, 2020). For the period 2015—2019, males accounted for a larger share of total perpetrators of child maltreatment than females in Korea. Among total perpetrators, 55—59% were males, and around 80% of them were fathers. By contrast, fathers spent a significantly shorter time with their children than mothers. The national household survey in 2018 in Korea showed that fathers spent around 4 hours a weekday with their children aged under 6 years on average, which is a half the time that mothers spent (Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korea Institute of Child Care and Education, 2019).

These findings suggest that interventions to prevent child maltreatment need to be designed considering potential pathways from unemployment shocks, especially male unemployment, to child maltreatment. Financial support for families who are vulnerable to economic downfalls will be important. To help individuals cope with stress from economic hardships, mental health services need to be expanded and made easy to access. Providing childcare services and regular home visits, especially for families with risk profiles such as single or unemployed parent, can help alleviate the negative impact of unemployment on child maltreatment. For instance, a study by Sandner and Thomsen showed that expanding public childcare reduced child maltreatment in Germany, and the effects were the strongest in families in which fathers were often unemployed (Sandner et al., 2020). The authors argued that, considering males were more often perpetrators, the expansion of childcare protected children by reducing time that children spent with potential male perpetrators.

This study has limitations. First, due to the lack of monthly data on actual child maltreatment cases, the monthly number of hotline calls related to child maltreatment was used as a proxy. This posed a limitation because it might include calls for falsely reported cases, redundant reporting, or not necessarily reporting cases, also it does not include reported cases through other channels such as calls to Child Protection Centers. Second, this study used data at the province level. Therefore, the findings does not explain how the relationship between unemployment and child maltreatment can vary depending on contextual factors within the household. For instance, although male unemployment is significantly associated with an increased risk of child maltreatment, if a female caretaker has a stronger bargaining power within the family or an unemployed male has a capability to cope with financial difficulties, the likelihood of child maltreatment may decline. Third, the time horizon in this study spanned over the first year and two months since the first COVID-19 case was confirmed. The relationship between unemployment and child maltreatment may evolve differently as the pandemic is prolonged because policies for reporting and responding to violence against children could be amended to better suit for the pandemic situation. Lastly, although different fixed effects were included to minimize biases due to omitted variables, there is still a possibility that time-varying variables at the monthly level that are potentially related to child maltreatment might be omitted, which will bias the estimators in the regressions.

6. Conclusions

This study showed that the risk of child maltreatment during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly associated with male unemployment in Korea using fixed effects regressions. It suggests that interventions to prevent child maltreatment would need to be designed considering potential pathways from economic shocks, especially male unemployment, to child maltreatment.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Norman Loayza (World Bank), Andrew Mason (World Bank), Aaditya Mattoo (World Bank), Elizaveta Perova (World Bank), and Tobias Pfutze (World Bank) provided valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105474.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ahmadabadi Z., Najman J., Williams G., Clavarino A., D’Abbs P., Abajobir A. Maternal intimate partner violence victimization and child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018;82:23–33. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R.P., Fromkin J.B., Stutz H., Makoroff K., Scribano P.V., Feldman K.…Fabio A. Abusive head trauma during a time of increased unemployment: A multicenter analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):637–643. doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2010-2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry R., Wang C. The link between male employment and child maltreatment in the U.S., 2000–2012. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;66:117–122. doi: 10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2016.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C., Richter F., Korbin J., Crampton D., Spilsbury J. Understanding trends in neighborhood child maltreatment rates: A three-wave panel study 1990–2010. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018;84:170–181. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2018.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H., Kim J., Black M., Weisbart C., Semiatin J., Magder L. Identifying children at high risk for a child maltreatment report. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35(2):96–104. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell C., Fleegler E., Monuteaux M., Wilson C., Christian C., Lee L. Community poverty and child abuse fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5) doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2016-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser E. VAWG Helpdesk; London, UK: 2020. “Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on violence against women and girls,” VAWG helpdesk research report no. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Grierson J. Guardian; 2020. Domestic abuse killings “more than double” amid Covid-19 lockdown.https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/15/domestic-abuse-killings-more-than-double-amid-covid-19-lockdown [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F. In: Econometrics. Hayashi F., editor. Princeton University Press; 2011. Finite-sample properties of OLS; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hoechle D. Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. The Stata Journal. 2007;7(3):281–312. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0700700301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2014. New directions in child abuse and neglect research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M., Kohl P., Drake B. Child and adult outcomes of chronic child maltreatment. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):839–845. doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2011-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz I., Katz C., Andresen S. Child maltreatment reports and Child Protection Service responses during COVID-19: Knowledge exchange among Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;116(Pt 2) doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2021.105078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan H., Marshall S., Nocera M., Runyan D. Increased incidence of inflicted traumatic brain injury in children after a natural disaster. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(3):189–193. doi: 10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korea Legislation Research Institute . 2018. Child Welfare Act (Enforcement Date 25 April 2018).https://law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=198257&viewCls=engLsInfoR&urlMode=engLsInfoR#0000 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor . 2020. Responding to COVID-19 : Emergency Employment Measures.https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/index.do [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor . 2021. 2020 Employment and Labor Policy in Korea.https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/index.do [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.J. In: National systems of child protection. Merkel-Holguin L., Fluke J., Krugman R., editors. Springer; Cham: 2019. Child protection system in South Korea; pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Ward K., Lee J., Rodriguez C. Parental social isolation and child maltreatment risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. 2021 doi: 10.1007/S10896-020-00244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindo J.M., Schaller J., Hansen B. Caution! Men not at work: Gender-specific labor market conditions and child maltreatment. Journal of Public Economics. 2018;163:77–98. doi: 10.1016/J.JPUBECO.2018.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy and Finance . 2021. Unemployment rate (overall, female, male), 2020-2021 (in Korean)https://kosis.kr/regionState/stateLabourUnemployment.do [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy and Finance . 2021. Mobility during COVID-19, 2020-2021 (in Korean)https://kosis.kr/covid/statistics_mobile.do [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korea Institute of Child Care and Education . 2019. National Survey on Childcare 2018 (in Korean)http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=032902&CONT_SEQ=349978&page=1 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency . 2019. Annual report on child abuse and neglect 2015-2018 (in Korean)https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/gm/sgm0704ls.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=13&MENU_ID=1304081001&PAR_CONT_SEQ=356034 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency . 2020. Annual report on child abuse and neglect 2019 (in Korean)https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=032901&CONT_SEQ=360165 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Child Protection Agency . 2021. Annual report on child abuse and neglect 2020 (in Korean)https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&page=1&CONT_SEQ=367066 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety Demographic statistics, 2020-2021 (in Korean) 2021. https://jumin.mois.go.kr/

- Morris M., Marco Miriam, Maguire-Jack Kathryn, Kouros Chrystyna D, Bailey Brooklynn, Ruiz Ernesto, Im Wansoo. Connecting child maltreatment risk with crime and neighborhood disadvantage across time and place: A Bayesian spatiotemporal analysis. Child Maltreatment. 2019;24(2):181–192. doi: 10.1177/1077559518814364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Police Agency Monthly hotline (112) calls related to child maltreatment, 2016-2021. 2021. https://www.open.go.kr/

- Sandner M., Thomsen S.L., Gonzalez L., Sandner M., Thomsen S., Gonzalez L. “Preventing child maltreatment: Beneficial side effects of public childcare provision,” Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series Working Paper no 1207. 2020. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:bge:wpaper:1207

- Schneider W., Waldfogel J., Brooks-Gunn J. The Great Recession and risk for child abuse and neglect. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;72:71–81. doi: 10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak M., Mettenburg A.J., Basena J., Petta I., McPherson A., Greene K., Li S. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; Washington, DC: 2010. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4) [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M., Hong S., Herrenkohl T., Brown E., Lee J., Jung H. Longitudinal effects of early childhood maltreatment on co-occurring substance misuse and mental health problems in adulthood: The role of adolescent alcohol use and depression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77(3):464–472. doi: 10.15288/JSAD.2016.77.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C., Czaja S., DuMont K. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Real or detection bias? Science. 2015;347(6229):1480–1485. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.1259917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J., Wai A.K.-C., Wang M.P., Lee J.J., Li M., Kwok J.Y.-Y.…Choi A.W.-M. Impact of COVID-19 on child maltreatment: Income instability and parenting issues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1–10. doi: 10.3390/IJERPH18041501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. The influence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on family violence in China. Journal of Family Violence. 2020 doi: 10.1007/S10896-020-00196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material