Abstract

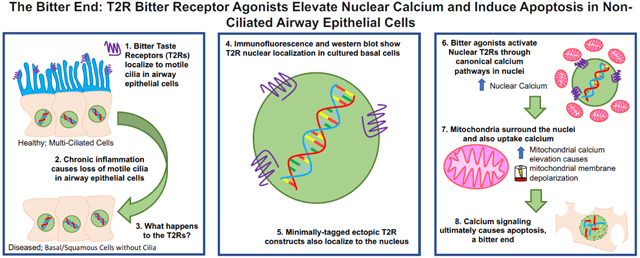

Bitter taste receptors (T2Rs) localize to airway motile cilia and initiate innate immune responses in retaliation to bacterial quorum sensing molecules. Activation of cilia T2Rs leads to calcium-driven NO production that increases cilia beating and directly kills bacteria. Several diseases, including chronic rhinosinusitis, COPD, and cystic fibrosis, are characterized by loss of motile cilia and/or squamous metaplasia. To understand T2R function within the altered landscape of airway disease, we studied T2Rs in non-ciliated airway cell lines and primary cells. Several T2Rs localize to the nucleus in de-differentiated but localize to cilia in differentiated cells. As cilia and nuclear import utilize shared proteins, some T2Rs may target to the nucleus in the absence of motile cilia. T2R agonists selectively elevated nuclear and mitochondrial calcium through a G-protein-coupled receptor phospholipase C mechanism. Additionally, T2R agonists decreased nuclear cAMP, increased nitric oxide, and increased cGMP, consistent with T2R signaling. Furthermore, exposure to T2R agonists led to nuclear calcium-induced mitochondrial depolarization and caspase activation. T2R agonists induced apoptosis in primary bronchial and nasal cells differentiated at air-liquid interface but then induced to a squamous phenotype by apical submersion. Air-exposed well-differentiated cells did not die. This may be a last-resort defense against bacterial infection. However, it may also increase susceptibility of de-differentiated or remodeled epithelia to damage by bacterial metabolites. Moreover, the T2R-activated apoptosis pathway occurs in airway cancer cells. T2Rs may thus contribute to microbiome-tumor cell crosstalk in airway cancers. Targeting T2Rs may be useful for activating cancer cell apoptosis while sparing surrounding tissue.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), mucosal immunology, cyclic-AMP, caspase, bacterial infection, chronic rhinosinusitis, chemosensation, nitric oxide, cystic fibrosis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Mucociliary clearance is the primary physical defense of the airways against inhaled pathogens, which get trapped in sticky mucus lining the airways. Motile cilia drive clearance of pathogen-laden mucus toward the oropharynx, where it is expectorated or swallowed [1]. Defects in ciliary function in primary ciliary dyskinesia [2] or mucus rheology in cystic fibrosis (CF) [3] impair mucociliary clearance and lead to recurrent and often fatal infections. Beyond driving mucociliary clearance, airway motile cilia area also immune sensors, reviewed in [4]. Ciliated cells express bitter taste receptors (T2Rs). T2Rs are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) originally identified on the tongue but which also act as innate immune ‘sentinels’ [5] by detecting bacterial quorum sensing molecules like bacterial N-Acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) [6, 7] and quinolones [5]. Several T2Rs, including T2R38, 4, 14, and 16 are located on human sinonasal [6, 8] and bronchial [9] cilia. These T2Rs respond to bacterial products by initiating Ca2+-triggered nitric oxide (NO) production to increase ciliary beat frequency and directly kill bacteria [6]. NO activates cyclic-GMP (cGMP) production and protein kinase G (PKG), which phosphorylates cilia proteins [4]. NO also damages cell walls and DNA of bacteria [10, 11] and inhibits replication of viruses [12], including SARS-COV-1 and −2 [13-15].

Clinical data support the importance of ciliated cell T2Rs in airway defense in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). CRS is an upper airway inflammatory disease with cycles of bacterial and/or fungal infection due to impaired mucociliary clearance [1]. The T2R38 isoform in airway cilia responds to AHL’s produced by gram-negative bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa [5]. The TAS2R38 gene encoding T2R38 has a common polymorphism resulting in a non-functional receptor via replacement of amino acids P49A, A262V, and V296I [16]. PAV T2R38 is functional, while AVI T2R38 is not. Homozygous AVI/AVI patients are at higher risk of CRS, are more likely to require surgical intervention for CRS, and may have poorer outcomes after surgery (reviewed in [5]). This led us to hypothesize that pathologies resulting in a loss of cilia, ciliary dysfunction, or airway remodeling may have a detrimental effect on innate immunity by impairing this T2R defensive pathway.

Several inflammatory airway diseases share phenotypes of acquired defects in cilia function or loss of cilia, including CRS [1], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [17], and CF [18]. CRS tissue exhibits de-differentiation of epithelial cells, squamous metaplasia, and loss of cilia [19-22], likely due to inflammatory remodeling. COPD is characterized by mucus hypersecretion and airway thickening, but another important phenotype is altered epithelial composition through squamous metaplasia and cilia loss [17, 23, 24]. CF tissue also exhibits cilia loss and squamous metaplasia [25]. Loss of cilia also occurs with viral or bacterial infection, type-2 inflammation-driven remodeling, or smoking (reviewed in [4]). Cilia loss increases the susceptibility of the epithelium to viral infection [26, 27]. A better understanding of how T2R signaling changes as the cellular composition of the airway epithelium changes is required to explore possible new therapies for advanced airway diseases.

Our goal was to understand how T2R Ca2+ signaling changes when ciliated cells are de-differentiated or replaced with squamous cells in airway disease. To model this cell type, we used immortalized non-ciliated airway cell lines as well as primary nasal and bronchial cells grown in submersion, which induces a squamous phenotype. While these cells expressed T2Rs, altered intracellular localization of T2R-induced Ca2+ responses and possibly the T2Rs themselves contributes to activation of alternative apoptotic signaling, likely involving Ca2+ signaling from the nucleus to mitochondria.

2. Results

2.1. Bitter compounds regulate nuclear Ca2+ in non-differentiated airway epithelial cells

To characterize T2R function in non-ciliated airway epithelial cells, we examined bitter agonist-induced intracellular Ca2+ (Ca2+i) release in primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells grown in submersion as non-ciliated basal cells [28] utilizing the dye Fluo-8. We also tested primary nasal epithelial cells immortalized with human BMI1 [29], and two bronchial epithelial lines. The first line was SV40-transformed human bronchial epithelial line 16HBE14o- (16HBE), which does not form motile cilia but is widely used as an immortalized ciliated cell [30]. We also used Beas-2B cells, immortalized by adenovirus 12 (Ad12)-SV40 hybrid virus, which exhibit a squamous phenotype in the presence of FBS [31]. T2R agonists diphenhydramine (DPD, 5 mM), flufenamic acid (FFA, 500 μM), and denatonium benzoate (15 mM) all induced Ca2+i release in these non-ciliated airway cells (Fig. S1). Known cognate T2Rs for all agonists used are in Table S2. Beas-2Bs and 16HBEs expressed varying levels of T2Rs, as did A549 lung carcinoma cells, with transcripts for DPD- and FFA-receptive T2R14 and all denatonium-associated T2Rs (Table S2) detected (Fig. S2).

We noted that Fluo-8 changes were more intense in the center of the cell, appearing as though Ca2+i release was localized to the nucleus, shown for Beas-2Bs in Fig. 1A. We saw similar results with Ca2+-sensitive dye Fura-2 in Beas-2Bs and 16HBEs (Fig. S3). Other GPCR agonists elicited more global Ca2+i responses, including histamine (Fig. S3A,B) and purinergic agonist ATP (Fig. S3D,E).

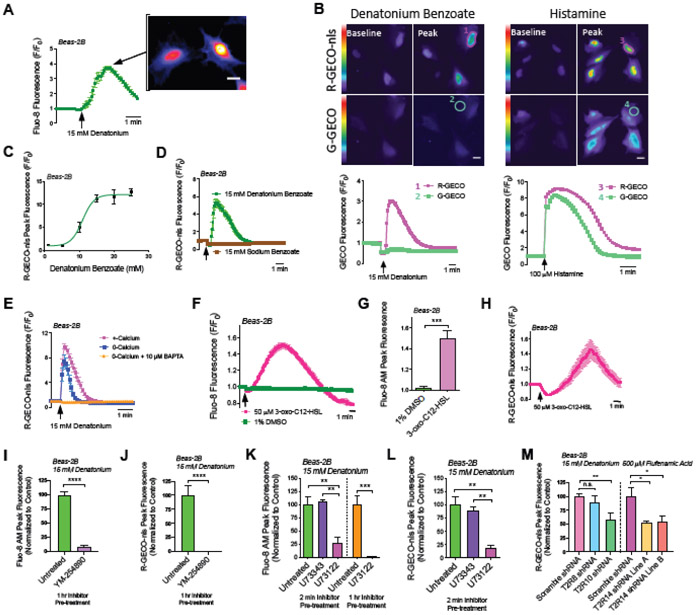

Fig. 1. Denatonium-induced T2R-mediated Ca2+ release is strongly localized to the nucleus in Beas-2B cells.

(A) Beas-2B cells were examined because they are a bronchial line with squamous phenotype in the presence of FBS [31]. Beas-2B cells were loaded with Ca2+ dye Fluo-8. Fluo-8 fluorescence trace and representative image during stimulation with denatonium, showing Ca2+nuc release. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Representative traces showing Beas-2B cells co-expressing G-GECO (Ca2+i) or R-GECO-nls Ca2+nuc) and preferential activation of Ca2+nuc with denatonium. Scale bar = 10 μm. (C) Dose response of peak Ca2+nuc (R-GECO-nls) in Beas-2B treated with denatonium. (D) Shown are two traces of R-GECO-nls fluorescence demonstrating that Denatonium, not Benzoate is necessary for activation of Ca2+nuc. (E) Ca2+nuc (R-GECO-nls) responses in cells ± 10 μM BAPTA-AM for 1hr ± extracellular calcium. 0-Ca2+o buffer contained no added Ca2+ plus 2 mM EGTA to chelate trace Ca2+. (F-H) Traces and bar graph showing Ca2+i (Fluo-8; (F,G)) and Ca2+nuc (R-GECO-nls; (H)) with quorum sensing molecule and T2R agonist 3-oxo-C12-HSL. (I-J) Inhibition of denatonium-induced Fluo-8 and R-GECO-nls responses with YM-254890 (1 uM, 1 hr pre-treatment). (K-L) Bar graphs showing inhibition of 15 mM denatonium-induced Ca2+i and Ca2+nuc with PLC inhibitor U73122 (1 μM; either 2 min or 1 hr pretreatment) but not inactive control analogue U73343. (M) Beas-2B’s stably expressing shRNA targeting either T2R10 or 14, but not T2R8 have reduced bitterant-induced Ca2+nuc signaling. All traces are representative experiments from ≥3 independent experiments with >15 cells selected per repetition. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM from ≥3 experiments; significance by T-test (G,I,J) or 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest (K,L,M), **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Tracing the center vs periphery of the cell has been used to estimate nuclear Ca2+ (Ca2+nuc; [32]), particularly when combined with nuclear stains or nuclear localization sequence (NLS)-tagged fluorescent proteins. However, to more directly investigate if Ca2+nuc was elevated with bitter agonists, Beas-2Bs were co-transfected with two genetically-encoded fluorescent Ca2+ sensors (GECOs), green (G)-GECO and NLS-tagged red (R)-GECO (R-GECO-nls) to differentiate between global Ca2+i and Ca2+nuc [33]. Denatonium benzoate increased R-GECO-nls fluorescence with less pronounced increase in G-GECO fluorescence (Fig. 1B). In contrast, histamine elevated both nuclear and non-nuclear Ca2+ similarly, suggesting denatonium benzoate preferentially increases Ca2+nuc with increased dosage (Fig. 1B-C). Ca2+nuc also increased in A549 cells as well as submerged primary nasal cells from 3 different patients in response to DPD, FFA, or denatonium (Fig. S4).

Denatonium benzoate activates ~8 T2Rs in heterologous expression studies [34], while sodium benzoate activates only two T2Rs with weaker affinity relative to most other agonists (Table S2). For most experiments here investigating mechanisms of Ca2+ signaling, we chose the lowest saturating denatonium concentration (15 mM). Denatonium benzoate (15 mM) activated Ca2+nuc while equimolar sodium benzoate did not (Fig. 1D), supporting that Ca2+nuc release is not due to changes in osmolarity or pH due to the benzoate anion. In Beas-2Bs, Ca2+nuc release was reduced but intact in HBSS with 0-Ca2+o (no added Ca2+ plus 2 mM EGTA to chelate trace Ca2+) but was eliminated when cells were preloaded with calcium chelator BAPTA (Fig. 1E).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing molecule 3-oxo-C12-HSL activates multiple T2Rs [5, 7]. We found that 50 μM 3-oxo-C12-HSL activated both Ca2+i (Fluo-8) and Ca2+nuc (R-GECO-nls) in Beas-2Bs (Fig. 1F-H). Together, these results demonstrate that multiple structurally different T2R agonists can elevate Ca2+nuc across a variety of non-ciliated primary and immortalized airway cells. Although these cells are lacking cilia for the T2Rs to localize to, the T2Rs are nonetheless functionally expressed.

To confirm we were measuring GPCR responses, we tested Beas-2Bs with broad-range G protein inhibitor, YM-254890 [35, 36]. YM-254890 (1 μM) inhibited both Ca2+i and Ca2+nuc with denatonium (Fig. 1I,J). T2Rs canonically signal through phospholipase C (PLC) downstream of the Gβγ of their heterotrimeric G protein [5]. Beas-2Bs were pretreated with PLC inhibitor U73122 (1 μM) or negative control U73343 (1 μM) prior to denatonium stimulation. Two minutes pre-treatment with U73122 but not U73343 inhibited Ca2+i and Ca2+nuc by ~75% (Fig. 1K,L). One hour pre-treatment with U73122 reduced Ca2+ by >99% (Fig. 1K). Thus, PLC is required for denatonium-induced Ca2+nuc signaling. Stable expression of shRNAs targeting either T2R10 or T2R14 reduced Ca2+nuc responses to denatonium benzoate (T2R10 agonist) or FFA (T2R14 agonist), respectively (Fig. 1M). Together, these data support that T2R’s are responsible for bitter agonist-induced Ca2+nuc signaling.

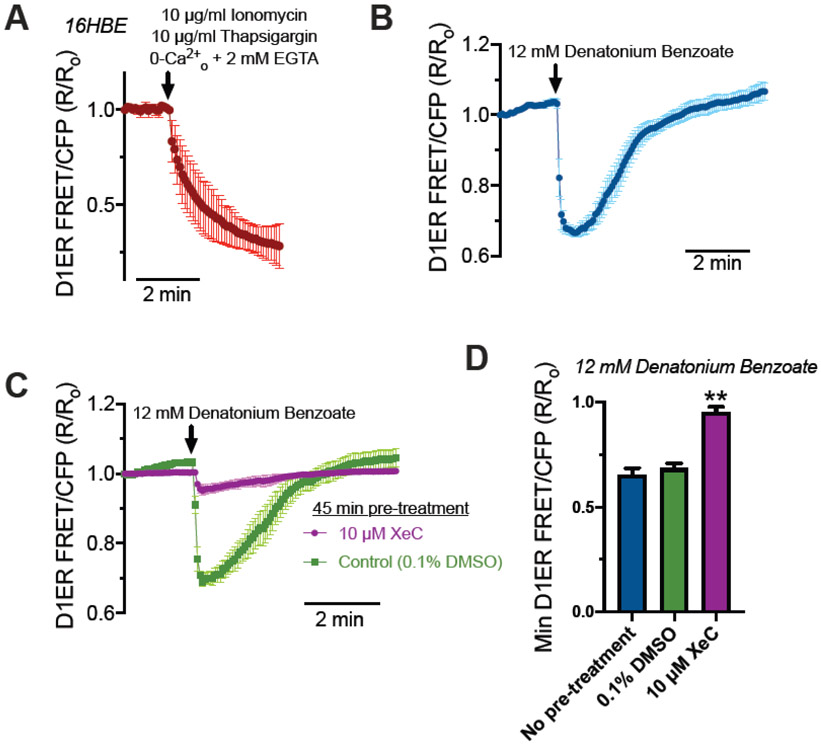

Ca2+nuc may be distinctly regulated from cytosolic Ca2+ signaling, though both are likely controlled by similar pathways including IP3 recptors (IP3Rs) or ryanodine receptors (RyRs) (reviewed in [37, 38]). The nuclear envelope is continuous with the ER, containing both IP3Rs and RyRs on the inner nuclear membrane [39]. Thus, the nuclear envelope is itself a Ca2+ store capable of releasing Ca2+ into the nucleus [40, 41]. We tested if T2R stimulation activated bulk Ca2+ depletion from the ER or if release was occurring from more local sources (e.g., nuceloplasmic granules). To do this, 16HBE cells were transfected with ratiometric CFP/YFP FRET-based ER Ca2+ (Ca2+ER) indicator D1ER [42] and imaged 48 hours later. As mentioned above, Ca2+nuc was largely intact in cells stimulated with denatonium in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig 1E), demonstrating that T2R-induced Ca2+nuc release originates in large part from internal Ca2+ stores. To validate D1ER function, cells expressing D1ER were treated with ionomycin and thapsigargin in HBSS containing EGTA with no added calcium. We observed a decrease in Ca2+ER (Fig 2A). Denatonium benzoate treatment also caused a reduction of Ca2+ER that relaxed to baseline (Fig 2B) suggesting that Ca2+ER is at least partly responsible for Ca2+nuc elevation. This Ca2+ER release is inhibited by xestospongin C, suggesting that it is dependent on the inositol triphosphoate receptor (IP3R) (Fig 2C,D).

Fig 2. Release of Ca2+ from ER stores during denatonium benzoate stimulation in 16HBE cells.

(A) Stimulation of cells with Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin and Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor thaspigargin in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (0-Ca2+o HBSS; no added Ca2+ plus 2 mM EGTA) to fully deplete ER Ca2+ stores and show the dynamic range of the indictor. Shown is average of 5 transfected cells from 5 independent experiments imaged at 60x. (B) Stimulation with 12 mM denatonium benzoate resulted in transient reduction of ER Ca2+. Shown is average of 4 transfected cells from 4 independent experiments imaged at 60x. (C) Denatonium benzoate-depletion of ER Ca2+ was blocked by 45 min pre-incubation by IP3R inhibitor xestospongin C (XeC) but not by vehicle control (0.1% DMSO). Shown is average of 4 transfected cells from 4 independent experiments imaged at 60x. (D) Min D1ER FRET/CFP R/Ro values were plotted from experiments shown in (B) and (C). Significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest; **p<0.01 vs either no pretreatment or 0.1% DMSO vehicle control. Our data suggest that the elevations in Ca2+nuc, at least in part, originate from the bulk cellular ER Ca2+ stores.

In A549 lung cancer cells, T2R agonist quinine activated dose dependent Ca2+nuc responses (Fig. S5A). We utilized A549s due to their strong adherence to glass during permeabilization of plasma membrane (but not intracellular organelles) with a low concentration of β-escin, previously used to study ER Ca2+ release [43]. In permeabilized A549s expressing R-GECO-nls, quinine inceased Ca2+nuc (Fig. S5B), suggesting that Ca2+nuc may originate from T2R signaling on intracellular membranes rather than at the plasma membrane.

In type II taste cells [44], T2Rs signal through Gα-gustducin to activate phosphodiesterase, lowering cAMP. In airway smooth muscle cells, T2Rs signal through Gαi isoforms to inhibit adenylyl cyclase, also lowering cAMP [45]. While T2R signaling in ciliated airway epithelial cells is Gα-gustducin-independent [46], it also correlates with decreased global cAMP [5, 47]. We observed a rapid decrease in cAMPnuc with bitter agonists, which coincided with the increase in Ca2+nuc, suggesting Gαi or Gα-gustducin activity (Fig. S6). Additionally, T2Rs in differentiated ciliated airway cells produce NO downstream of Ca2+ via endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [6, 8]. In non-ciliated cell models, we also observed an increase in NO and cGMP production (Fig. S7).

2.2. T2R14 and T2R39 are localized at least partially to the nucleus in non-differentiated airway epithelial cells

Intrigued by the strong Ca2+nuc response, we investigated T2R localization in submerged airway cells. We hypothesized that T2Rs may be at least partly localized to the nucleus or surrounding membranes. GPCRs and associated proteins can localize to and function on the outer nuclear membrane or within internal nucleoplasmic reticulum membranes [48, 49]. A previous study reported an altered staining of T2R38 from cilia in normal tissue to nuclear localization in inflamed and deciliated CRS tissue [50], though antibody specificity was not verified nor were functional consequences reported. We hypothesized that the strong regulation of Ca2+nuc may be partly due to localization of certain T2Rs to the nucleus or surrounding ER membranes in the absence of proper trafficking to cilia.

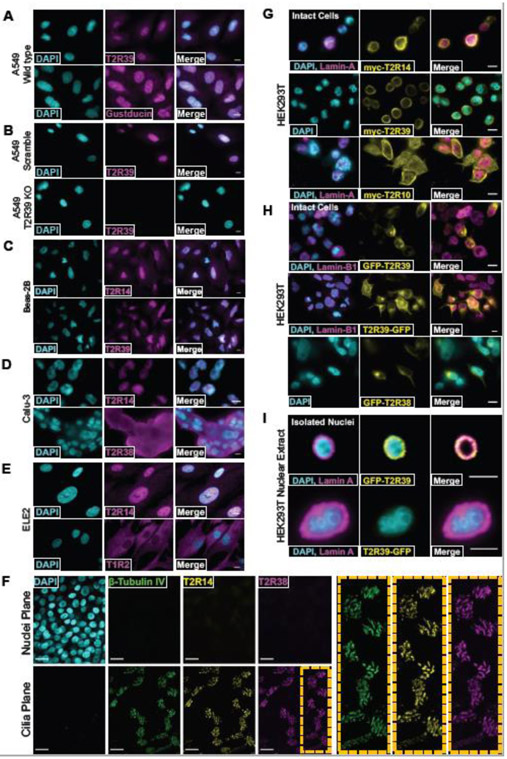

Using confocal immunofluorescence, we observed nuclear staining with antibodies directed against T2R14 and T2R39 in multiple airway cell types (Fig. 3A-E and Fig. S8). The antibody against T2R14 was previously validated to detect recombinant T2R14 and not other T2Rs [8]. To test if the staining for T2R39 was specific, A549s were treated with CRISPR-Cas9 lentivirus to create a frameshift in TAS2R39, thus creating a T2R39 knockout line. There was no observed staining of T2R39 in these knockouts compared with scrambled guide RNA controls, supporting the specificity of the antibody and the T2R39 nuclear localization (Fig. 3B). We also observed nuclear staining with an antibody directed against α-gustducin (Fig. 3A), though implications for this are unclear in light of data from Fig S5E and previous studies suggesting airway epithelial T2R Ca2+ signaling is gustducin-independent [46].

Fig. 3. Nuclear localization of T2R14 and T2R39.

(A-E) Fixed cultures of non-ciliated airway cells stained with antibodies targeting T2R14, T2R39, and Gustducin. (B) CRISPR-cas9-induced scramble or T2R39 KO cell lines were stained for T2R39. (D-E) T2R38 and T1R2 are not localized to the nucleus in Calu-3 (lung adenocarcinoma) or ELE2 (hBMI immortalized primary bronchial epithelial cells) respectively. (A-E) scale bar is 10 μm. (F) Differentiated primary nasal epithelial cells contain T2R14 and T2R38 on cilia, not nuclei. All images are representative image from ≥3 independent experiments. Scale bar is 25 μm. (G) Fixed HEK cells expressing ectopic myc-tagged T2R14, T2R39, or T2R10 and co-expressing mCherry Lamin-A stained with anti-myc antibody, showing nuclear localization of T2R14 and T2R39. (H) Representative images showing GFP-T2R39 but not T2R39-GFP localizes to the nucleus in fixed HEK 239T cells. (I) Nuclei from HEK cells expressing GFP-T2R39 or T2R39-GFP. For all images, 1 representative image from ≥3 experiments were shown. For all images scale bars represent 10 μm.

Not all T2Rs appeared nuclear in all cells; T2R38 exhibited plasma membrane localization in Calu-3 bronchial cells while T2R14 was nuclear (Fig. 3D). An antibody against sweet taste receptor subunit T1R2 stained a non-nuclear cytoplasmic pattern in hBMI immortalized primary HBE ELE2 cells, while T2R14 remained nuclear (Fig. 3E). When the same T2R14 antibody was used to stain differentiated primary nasal epithelial cells, T2R14 was located on the cilia and not the nucleus (Fig. 3F), as previously described [8]. T2R39 was previously reported by others to be expressed in differentiated bronchial cell cilia [9]. Thus, in airway cells without cilia, such as de-differentiated squamous or cancer cells, T2R14 and T2R39 may instead localize at least partly to the nucleus. We also observed that denatonium-responsive T2R4, 8, and 39 are located at least partly to the nucleus in Beas-2Bs and A549s but not in HEK293T cells via Western (Fig. S9).

HEK293Ts are often used as a “null background” model for heterologous expression of T2Rs (e.g., [8, 34]). However, we noted that quinine evokes Ca2+ responses even in HEK293Ts lacking ectopic T2R expression (shown below). A recent study suggested expression of endogenous T2R14 in HEK293Ts [51]. We evaluated Ca2+nuc during treatment with several T2R agonists. Unlike airway cells, neither denatonium benzoate nor equimolar sodium benzoate increased Ca2+nuc in HEK293Ts (Fig. S10A), demonstrating that Ca2+nuc signaling via denatonium treatment has cell type specificity. T2R14 does not respond to denatonium benzoate. However, DPD, which does activate T2R14, increased Ca2+nuc in HEK293Ts (Fig. S10B), supporting endogenous T2R14 regulation of Ca2+nuc in HEK293TS. HEK293Ts express a variety of T2Rs by qPCR (Fig. S10C). Transfection of HEK293Ts with a GFP reporter containing the 2000 base pair promotor regions of T2R14 revealed bright GFP fluorescence (Fig. S10D). Immunofluorescence staining of HEK293Ts with two different T2R14 antibodies was plasma membrane localized at cell-cell contact points but also partly nuclear (Fig. S10E). Though HEK293T cells are used as a “null” model for T2R functional studies, they express at least one functional T2Rs. We continued to investigate how bitter compounds regulate Ca2+nuc in airway cells, but this may also occur in a cells outside the airway.

Many studies utilize heterologous expression of T2Rs containing the first 45 amino acids of rat somatostatin type 3 receptor (SSTR3) or bovine rhodopsin fused to the N-terminus enhance plasma membrane localization (e.g., [34, 52]). While these constructs are useful for characterizing novel T2R agonists, we wanted to look at localization of heterologously expressed T2Rs using constructs with minimal tagging. We expressed T2Rs in HEK293Ts with only a single N-terminal myc and observed strong nuclear localization of myc-T2R14 and myc-T2R39, but not myc-T2R10, using anti-myc antibody (Fig. 3G). We propose that there may be different subcellular localizations of different T2R isoforms within the same cells and between different cells (Fig. S7).

To further examine localization of T2R39, we expressed either N-terminal or C-terminal GFP fusion constructs. While N-terminally tagged GFP-T2R39 co-localized with partly with nuclear membrane marker Lamin-B1, C-terminally tagged T2R39-GFP appeared less nuclear. Non-canonical C-terminal NLS sequences in mGluR5 are important for nuclear localization [53]. Similar C-terminal sequences may be important for T2R39, as C-terminal GFP may block interactions conferring nuclear localization. For comparison, GFP-T2R38 did not appear nuclear, suggesting that the nuclear localization of GFP-T2R39 is an effect of the T2R39 sequence and not the N-terminal GFP (Fig. 3H). To further test this, we co-expressed either GFP-T2R39 or T2R39-GFP with mCherry-Lamin A in HEK293Ts. Consistent with above, GFP-T2R39 was localized to the membrane of isolated nuclei while T2R39-GFP was not (Fig. 3I), suggesting C-terminal sequences may be important for nuclear localization.

2.3. Bitterant-induced Ca2+i release signals to the mitochondria

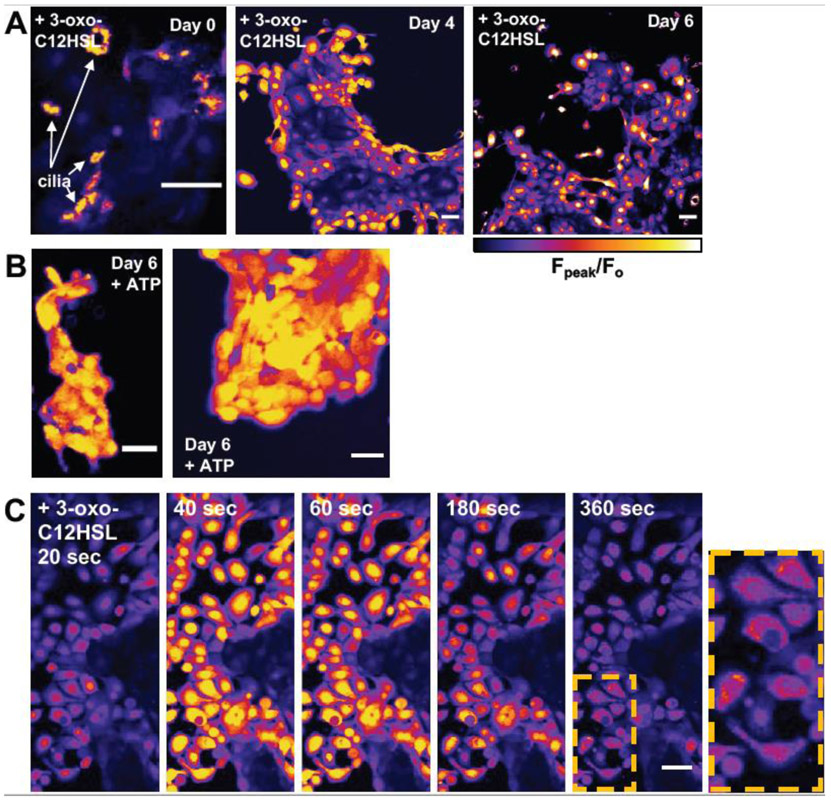

What are the consequences of T2R-induced Ca2+i in non-ciliated airway cells? Denatonium has been shown to alter mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) [54]. The bitter compound absinthin has also been linked to influx of mitochondrial Ca2+(Ca2+mito) [55]. We also observed sustained, mitochondrial-reminiscent Ca2+ elevations in primary nasal cells grown in submersion (Fig. 4). Freshly isolated ciliated cells from nasal brushings (day 0) treated with 100 μM 3-oxo-C12HSL were observed to have a cilia-localized Ca2+ signal (Fig 4A). However, after 4-6 days of submersion, the cilia are lost and this Ca2+ signal appeared to originate from the nuclei (Fig 4A) while treatment with ATP revealed a more global cellular Ca2+ response (Fig 4B). A more careful examination of Day 6 submerged nasal cells revealed that while the Ca2+ signal originates in the nuclei, it then may spread to surrounding perinuclear regions (Fig 4C), possibly mitochondria. Thus, we hypothesized that elevation of Ca2+nuc might signal to the mitochondria and investigated this more rigorously.

Fig. 4. Ca2+ responses to 3-oxo-C12HSL in primary nasal cells loaded with Fluo-4 appear to shift from cilia to nuclear after 4-6 days in culture.

(A) Fpeak/Fo images of peak responses to 100 μM 3-oxo-C12HSL in ciliated cells removed from nasal brushings (day 0) and then cultured in submersion (Lonza BEBM basal media plus SingleQuot growth supplements) on plastic over 4-6 days (during which time, cilia are lost and spread out into a more squamous morphology). Note the change in response from cilia-localized at day 0 to nuclear localized at days 4-6. The intensity of images first three images are scaled identically, thus the magnitude of the cilia-localized response was similar to the nuclear-localized response. (B) Responses to ATP at day 6, which elicited a more global cellular Ca2+ responses. (C) Fluo-4 responses to 3-oxo-C12HSL in cultured submerged cells (day 6 shown) appeared to initiate in the nucleus and resulted in more sustained Ca2+ elevation in the perinuclear region, possibly the mitochondria. All images are representative of results observed from cells isolated and cultured from 3 different patent TAS2R38 PAV/PAV patient turbinates. All scale bars are 40 μm.

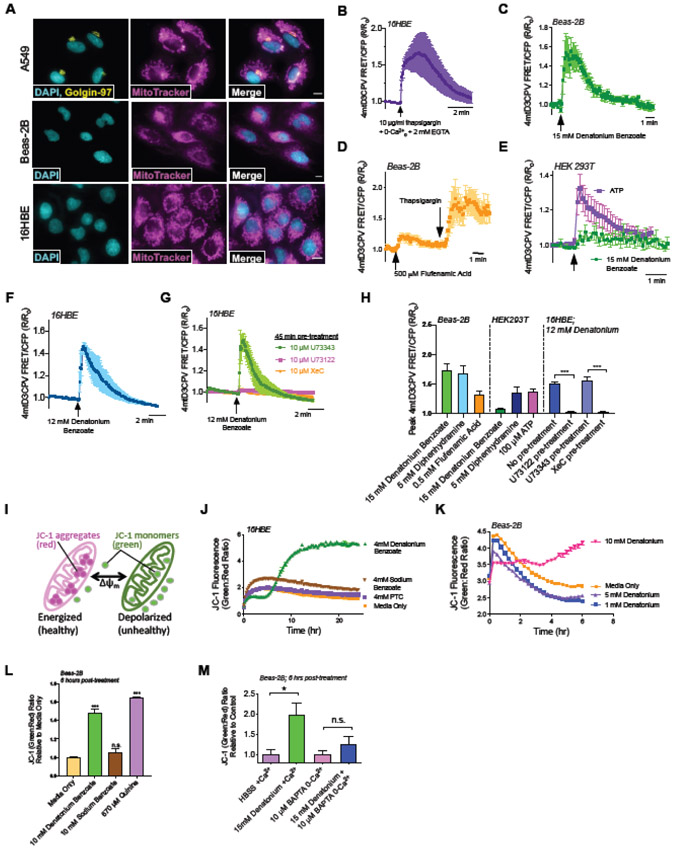

In A549, Beas-2B, and 16HBE cells the mitochondria are in close proximity to the nucleus (Fig. 5A). To test if denatonium activates Ca2+mito, we expressed mitochondrial-localized ratiometric Ca2+ sensor 4mtD3cpv [56] in 16HBEs, Beas-2Bs, or HEKs [56]. When 16HBEs expressing 4mtD3cpv were treated with thapsigargin in 0-Ca2+ HBSS with 2 mM EGTA, we saw a rise in Ca2+mito, suggesting internal Ca2+ stores can feed mitochondria (Fig. 5B). Both denatonium benzoate and FFA, two T2R agonists that increased Ca2+nuc in Beas2Bs, also increased Ca2+mito in Beas-2Bs (Fig. 5C-D). In contrast to Beas2Bs, denatonium did not increase Ca2+mito in HEK293Ts (Fig. 5E), which do not exhibit Ca2+nuc increases to denatonium (Fig. S10A). However, diphenhydramine did increase Ca2+nuc in both HEK293Ts and Beas-2Bs (Fig. S10B). Thus, DPD correspondingly increases Ca2+nuc and Ca2+mito in both cell lines (Fig 5H). Like Beas-2Bs, 16HBE Ca2+mito increased with denatonium (Fig. 5F,H). This was blocked by U73122 or IP3 receptor antagonist xestospongin C (Fig. 5G-H). Thus, bitter compounds that activate Ca2+nuc also activate Ca2+mito, and both responses share similar signaling requirements.

Fig. 5. Acute transient Ca2+mito elevation in airway cells treated with T2R agonists initiates mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) depolarization.

(A) Fluorescence images of nuclear stain DAPI and MitoTracker in A549, Beas-2B, and 16HBE cells, plus immunofluorescence for Golgi marker golgin-97 in A549 cells. Scale bars are 10 μm. (B) Trace of ratiometric CFP/YFP FRET-based mitochondrial-targeted Ca2+ indicator 4mtD3cpV in 16HBEs showing elevation of intracellular Ca2+ by Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin in 0-Ca2+o HBSS (no added Ca2+ and 2 mM EGTA) increased mitochondrial Ca2+, demonstrating that store Ca2+ release can elevate Ca2+mito. (C-D) Trace showing stimulation of Beas-2Bs with denatonium or flufenamic acid increased Ca2+mito. (E) Trace showing minimal Ca2+mito response in HEK cells, which also do not exhibit Ca2+nuc responses to denatonium. (F) Trace showing denatonium elevated Ca2+mito in 16HBE cells. (G) This elevation of Ca2+mito was blocked by pre-treatment with PLC inhibitor U72122 or IP3R inhibitor xestospongin C (XeC). Note that DMSO concentration (0.1%) is the same for all conditions, so inactive U73343 pretreatment also serves as vehicle control for XeC. (H) Bar graph showing peak 4mtD3CPV responses represented as mean ± SEM from independent experiments shown in (B-G) and additionally with 5 mM Diphenhydramine. (I) Mitochondrial membrane potential detection dye JC-1 shifts from red to green fluorescence with depolarization. (J-M) Traces and bar graph of ratiometric mitochondrial membrane potential dye (JC-1) showing that denatonium, not benzoate, initiates mitochondrial membrane depolarization in 16HBEs (J) and Beas-2Bs (K-M). All traces show representative results from ≥5 transfected cells from one of ≥4 independent experiments imaged at 60x. Time course experiments are representative of ≥3 independent experiments. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM from ≥3 experiments. Significance by 1-way ANOVA using Dunnett’s or Tukey’s posttest *P<0.05, ***P<0.0005 ****P<0.0001.

To assess whether this Ca2+mito influx impacted mitochondrial function, we utilized the ratiometric dye JC-1 to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) (Fig. 5I). In 16HBEs and Beas-2Bs, denatonium and quinine depolarized ΔΨm (Fig. 5J,K). This effect on ΔΨm did not occur with sodium benzoate (Fig. 5L). Blocking Ca2+ signaling prevented bitterant-induced depolarization of ΔΨm (Fig. 5M). This supports previous findings that denatonium depolarizes ΔΨm [54] but furthermore reveals that this depolarization is initiated through Ca2+ signaling.

2.4. Bitterant-induced Ca2+ release signals cell death in squamous airway cells but not in well-differentiated cultures

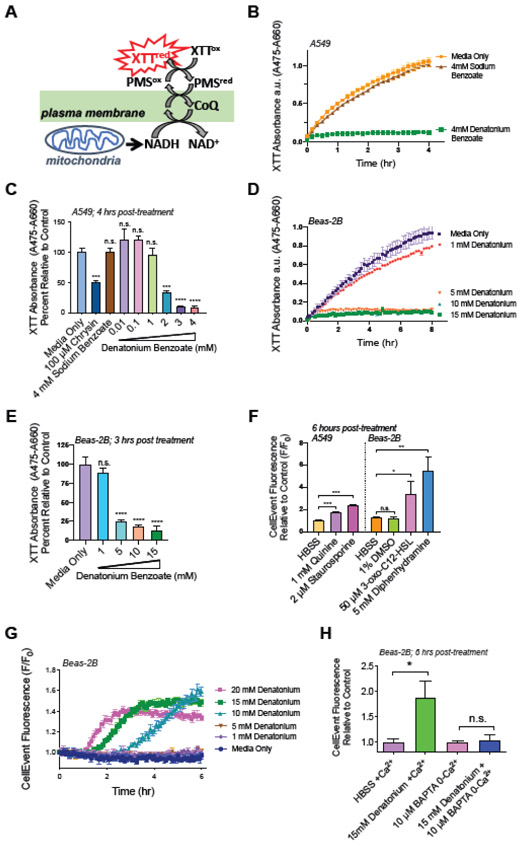

Excess Ca2+mito influx has been linked to cell death [57, 58], and denatonium benzoate has been shown to inhibit cell growth [54]. To determine denatonium’s effect on metabolism in non-ciliated airway cells, we measured NADH production indirectly using XTT (Fig. 6A). Denatonium benzoate inhibited XTT reduction at concentrations ≥1 mM in A549’s while equimolar concentrations of sodium benzoate had no effect (Fig. 6B,C). Flavone bitter-taste receptor agonist chrysin (100 μM) also impaired XTT reduction ~50% in A549s (Fig. 6C). Additionally, the reduction of XTT was also inhibited by concentrations ≥5 mM of Denatonium in Beas-2Bs (Fig. 6D,E). This is very close to the concentration where we see onset of Ca2+nuc responses (~10 mM; Fig 1C).

Fig. 6. Denatonium halts cell metabolism and initiates apoptosis.

(A) Depiction of XTT cell viability assay. (B,C) Denatonium, not benzoate, halts A549 metabolism. (C) A549 metabolism is impaired by T2R agonists chrysin and denatonium at concentrations >1 mM. (D,E) Denatonium also halts Beas-2B metabolism at concentrations ≥5 mM. (F) Bar graph CellEvent fluorescence at 6 hours, indicating caspase activation in A549s in response to quinine and in Beas-2Bs in response to 3-oxo-C12HSL and diphenhydramine. Staurosporine = positive control. (G) Trace showing CellEvent fluorescence increases signifying caspase activation in Beas-2Bs incubated with increasing concentrations of denatonium. (H) Beas-2Bs were pre-incubated with 10 μM BAPTA in 0-Ca2+ HBSS then treated with denatonium. Time course experiments are representative of ≥3 independent experiments. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM from ≥3 experiments. Significance by 1-way ANOVA using Dunnett’s or Tukey’s posttest *P<0.05, ***P<0.0005 ****P<0.0001.

Does ΔΨm depolarization and changes in cell metabolism correlate with apoptosis? To measure caspase activity, we treated cells with the caspase 3/7-sensitive DEVD-based dye CellEvent (Thermo). In A549s and Beas-2B’s, T2R agonists quinine, 3-oxo-C12-HSL, and DPD activated apoptosis, visualized by an increase in CellEvent fluorescence (Fig. 6F). Denatonium also activated apoptosis, (>5 mM; Fig. 6G) again at concentrations paralleling concentrations eliciting Ca2+nuc signaling (Fig. 1C) and ΔΨm depolarization (Fig. 5K). To determine if Ca2+ is directly linked to caspase activation, we pre-incubated Beas-2Bs in 0-Ca2+ HBSS with 10 μM BAPTA ± 15 mM denatonium. As observed with ΔΨm (Fig. 5M), the Ca2+-chelator BAPTA prevented cell death (Fig. 6H) over at least 6 hours. Thus, bitterant-induced Ca2+ elevation is required for ΔΨm depolarization and apoptosis.

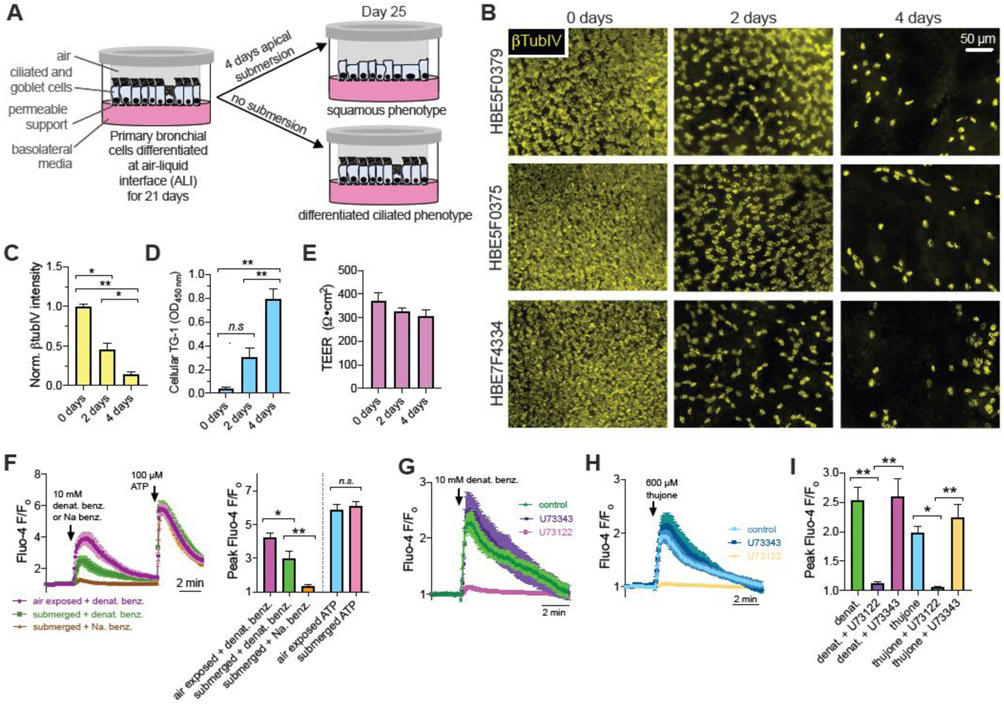

To better test the physiological relevance of the mechanistic above data, we tested bitter agonist-induced apoptotic cell death in de-ciliated squamous metaplastic primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells versus fully differentiated ciliated cultures at air liquid interface (Fig. 7A). Primary bronchial epithelial cells grown in air liquid interface (ALI) transwell cultures were submerged for 4 days, which causes a marked loss of cilia over time as visualized through β-tubulin-IV immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 7B-C). Cellular transglutaminase 1 (TG-1) expression, a marker of squamous metaplasia [59] went up vis ELISA (Fig. 7D) with decreasing βTubIV (Fig. 7C) while transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) remained the same (Fig. 7E). Thus, cells remained viable to maintain the epithelial barrier as they changed from a ciliated to squamous phenotype. In age-matched cultures, denatonium-induced Ca2+ signaling in both air-exposed and squamous cells, while equimolar sodium benzoate had no effect (Fig 7F). Comparable to cell line models, Ca2+ signaling was inhibited by PLC inhibitor U73122 (Fig. 7G-I). Due to the thickness of the primary cell 3D ALI model and resistance to transfection or infection, we did not quantify levels of cytosolic vs nuclear Ca2+ in this model.

Fig. 7. De-ciliated bronchial epithelial cells retain Ca2+ responses to bitter agonists.

(A) Primary HBE cells grown on transwells and differentiated at air liquid interface (ALI) were exposed to 4 days of air or apical submersion (as described in the Methods and [59]). Apical submersion increases squamous differentiation [27, 59, 127]. (B) Immunofluorescence of cilia marker β-tubulin-IV (βTubIV; detected using mouse monoclonal antibody ONS.1A6 (Abcam ab11315) showed marked loss of cilia as previously described [59]. De-identified donor numbers shown on the left, days of submersion shown on the top. Cells were visualized by with 10x objective on a wide-field microscope with GFP filters as described [59]. (C) Quantification of βTubIV immunofluorescence in cultures from 5 donors (1 ALI per donor at each time point showing decreasing intensity with 2 and 4 days apical submersion. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest; *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. (D) Cellular transglutaminase 1 (TG-1) expression was measured as a marker of squamous metaplasia was measured as described [59] using TG-1 ELISA (Aviva Systems Bio, San Diego, CA, Cat # OKCD01601). TG-1 expression went up with decreasing βTubIV. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest; **p<0.01 and n.s. = no significance difference. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM of data from 3 ALIs per time point from 3 separate donors (1 ALI per time point per donor, 9 ALIs total). (E) Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was not altered by submersion, suggesting the epithelial barrier was intact. No significant difference by one-way ANOVA. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM of data from 4 ALIs per time point from 4 separate donors (4 ALI per time point per donor, 12 ALIs total). (F) Ca2+ responses were measured as described [59] using Fluo-4 in 4-day submerged vs age-matched air-exposed cultures. Average traces mean ± SEM) from 6-9 ALIs from 3 donors (2-3 separate ALIs from each donor) per condition shown on the left and bar graph quantification of Ca2+ peaks shown on the right. While the Ca2+ response to denatonium benzoate was reduced, it was not eliminated by submersion. Response to purinergic agonist ATP was unchanged. There was no response to sodium benzoate in submerged cultures. Significance determined by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest using paired comparison as indicated; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and n.s. = not significantly different. (F-H) Responses to T2R agonists denatonium (representative traces in (G)) and thujone (representative traces in (H)), in submerged cultures were reduced by phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 (10 μM; 1 hr pre-treatment) but not inactive control U73343. Peak Ca2+ responses summarized in bar graph shown in (I). Significance determined by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest using paired comparison as indicated; *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

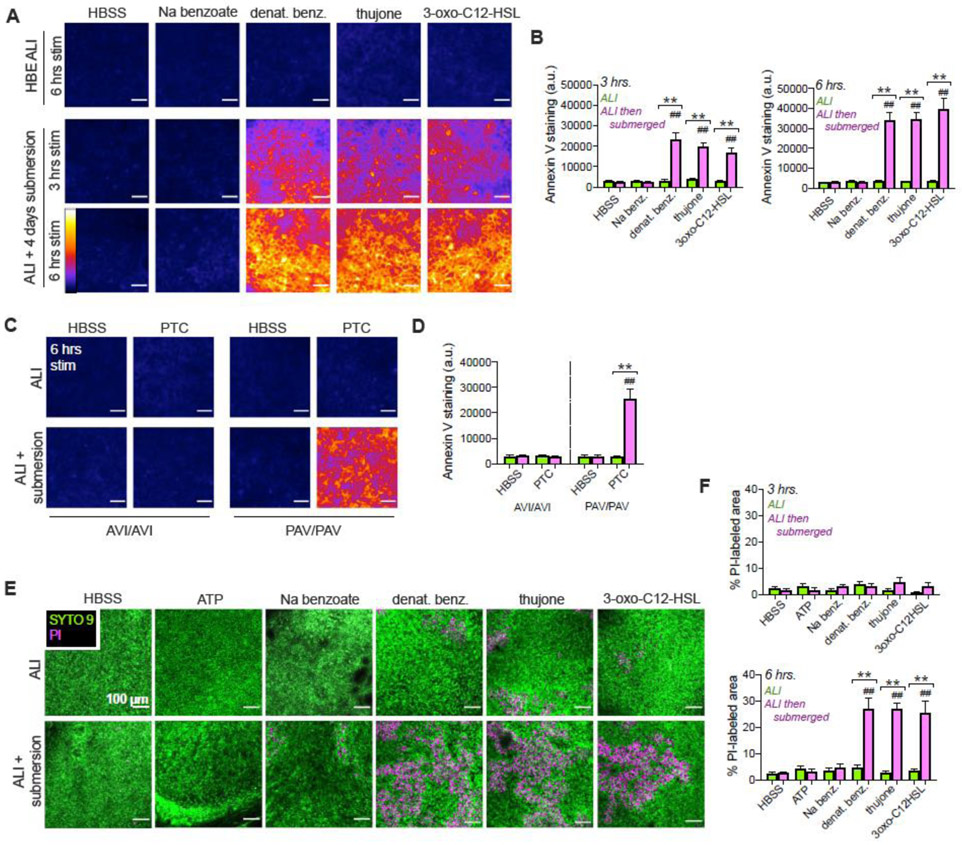

We tested if bitterant-activated Ca2+ causes apoptosis in primary squamous cells derived from ALI cultures. Annexin V-FITC staining increased over 3-6 hrs in submerged cultures stimulated with denatonium benzoate, thujone, or 3-oxo-C12HSL, but not sodium benzoate (Fig. 8A-B). Normally differentiated ciliated cultures did not exhibit Annexin V staining. To tie these responses more fully to T2R function, differentiated vs squamous primary nasal cultures were likewise stimulated with T2R38 agonist PTC. PTC increased annexin V staining only in squamous cultures that were homozygous for the functional T2R38 isoform (PAV polymorphism [6, 16]). Cultures homozygous for non-functional T2R38 (AVI isoform) did not exhibit increased annexin V staining (Fig. 8C-D). This suggests the increased Annexin V-staining in response to PTC is dependent on the cells having functional T2R38.

Fig. 8. T2R agonists induce cell death in submerged but not differentiated primary HBE and sinonasal cells.

(A) Denatonium benzoate, thujone, or 3-oxo-C12HSL increased Annexin V FITC staining in deciliated (submerged) but not differentiated HBE cells. Representative intensity pseudocolored images shown. Scale bar 100 μm. Sodium benzoate (control for denatonium benzoate) had no effect. (B) Bar graphs of relative fluorescence intensity (mean ± SEM) from 4 cultures (2 each from 2 donors) per condition stained at 3 (left) or 6 hours (right). Green bars show air-exposed; magenta bars show submerged. Significance by 1-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest; **p<0.01 between bracketed bars (submerged vs air-exposed) and ##p<0.01 vs HBSS only. (C) Experiments carried out similarly to (A-B) in TAS2R38-genotyped primary nasal cultures ± 500 μM PTC. TAS2R38 (encoding T2R38) has two polymorphisms Mendelianly-distributed in the Philadelphia population [123]. The PAV allele encodes a functional receptor while the AVI allele encodes a non-functional receptor [16]. ALIs from PAV/PAV patient cells exhibit Ca2+ responses to T2R38-specific agonist PTC while ALIs from AVI/AVI homozygous patient cells do not [6]. Representative images show Annexin V-FITC staining at 6 hrs, which increased in PAV/PAV cells exposed to submersion but not air-exposed cells. Staining did not increase in AVI/AVI cells under either condition. (D) Bar graph of mean ± SEM of Annexin V FITC staining from 4 cultures per condition, each from a separate PAV/PAV or AVI/AVI patient. Significance by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest; **p<0.01 between bracketed bars (submerged vs air-exposed) and ##p<0.01 vs HBSS only. (E) Representative images of live-dead (Syto9 in green and propidium iodide [PI] in magenta) staining of HBE cells. (F) Bar graph (mean ± SEM,4 cultures per condition, 2 each from 2 donors) of PI-labeled area from experiments as in (E). Significance by 1-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest; **p<0.01 between bracketed bars (submerged vs air-exposed) and ##p<0.01 vs HBSS only.

Submerged squamous HBE cultures showed increased propodium iodide (PI) staining 6 hours after stimulation with denatonium benzoate, thujone, or 3-oxo-C12HSL but not sodium benzoate or ATP (Fig. 8E-F). The earlier onset of Annexin V staining (3 hrs) vs PI staining (reflecting permeabilization, at 6 hours) supports an apoptotic mechanism. The PI staining likely reflected secondary necrosis in the absence of phagocytes to clear apoptotic cells [60, 61]. Together, the data suggest that T2R agonists activate apoptotic cell death in squamous but not well-differentiated airway epithelial cells.

3. Discussion

We demonstrate nuclear localization of at least some endogenous T2Rs involved in airway defense. These receptors were previously shown to be localized to cilia of differentiated ciliated cells [6, 9]. In less differentiated cells, they appear to localize at least partly to the nucleus. One prior study reported nuclear localization of T2R38 in tissue from CRS patients [50]. While the authors speculated that nuclear T2R38 had an inflammatory role, no functional consequences were reported. Here, we found that T2R14 and T2R39 located on the nucleus of non-ciliated airway cells may signal through Ca2+nuc, cAMPnuc, and NO. Additionally, bitter compounds also increase Ca2+mito and depolarize ΔΨm, ultimately initiating apoptosis. Previously, bitter compounds have been described to induce apoptosis [62, 63], which has been attributed to oxidative stress [54]. Here, we instead suggest that T2R agonists signal an elevation of Ca2+nuc and Ca2+mito, which causes depolarization of ΔΨm and initiates an apoptotic program. We hypothesize that the intense Ca2+nuc increase in close proximity to the mitochondria overloads Ca2+mito.

These mechanisms likely have multiple physiological implications. First, this apoptotic pathway may be utilized as a “last resort” in response to bacterial metabolites if infection infiltrates past the epithelial barrier layer in well-differentiated epithelia. Programmed cell death is an important part of innate immune defense [64]. This pathway may also be activated aberrantly by bacterial metabolites during diseases involving epithelial remodeling and cilia loss such as CRS [20-22]. Lastly, there are potentially important implications for epithelial-derived lung cancers. We observed Ca2+nuc responses and/or cell death in several lung cancer lines (e.g., A549) but not in well-differentiated primary cells. This suggests further investigation of T2Rs as therapeutic targets in lung cancers, where they may activate apoptosis in tumor cells but not differentiated cells. T2Rs may also contribute to tumor-microbiome crosstalk in airway cancer.

We hypothesize that absence or loss of motile cilia causes T2Rs to alternatively localize to the nucleus in non-ciliated airway cells. Both endogenous T2R14 and T2R39 as well as heterologous minimally-tagged T2R14 and T2R39 localize to the nucleus. Many previous studies utilized T2R constructs with N-terminal SST- or rhodopsin-tags as well as C-terminal HSV tags to promote trafficking to the plasma membrane may inadvertently mask native localization [34, 52]. While this may be ideal for agonist profiling, studies of T2R function should likely not rely on tagged constructs as altered localization may occur. To our knowledge, the kinetics of bitter agonists (e.g. , denatonium) diffusion into cells has not been well characterized, thus it is important to note that known EC50 values (Table S2) obtained via ectopic expression of T2Rs artificially targeted to the plasma membrane may not directly correlate observations of Ca2+nuc signaling in dedifferentiated or cancer cells derived from the airway.

Many GPCRs localize at least partly to the nucleus (reviewed in [65]). Some nuclear GPCRs may even act as transcription factors [66]. Nuclear GPCRs are important for diverse functions like retinal vascularization [67], synaptic function [68], cell proliferation [69], and neuropathic pain [70]. Nuclear GPCRs have varied methods of targeting to the nucleus, including canonical and non-canonical NLS sequences [71]. The mGluR5 receptor, which also regulates Ca2+nuc [72], localizes to the nucleus [73] through C-terminal sequences despite a lack of canonical NLS [53]. The relative levels of plasma membrane vs. nuclear mGluR5 vary among cell types [72, 74], suggesting that nuclear GPCR trafficking depends on factors in addition to the receptor itself [75]. Masking the C-terminus of two T2Rs by adding a GFP reduces their nuclear localization, suggesting C-terminal interactions may also be important.

Future truncation and mutagenesis studies are needed to identify sequences important for nuclear localization or identify binding partners that may shuttle T2Rs to the nucleus. This may also clarify how T2Rs traffic to cilia. Because T2Rs are not markedly nuclear-localized when cells form motile cilia, other proteins may facilitate T2R trafficking away from the nucleus in multi-ciliated cells. Transport of proteins into the cilia involves components shared with nuclear import [76], including importins and nucleoporins important for import of GPCRs into the nucleus [77-79]. This may be due to the close relationship between primary ciliary signaling and regulation of gene transcription, which requires movement of signaling molecules from the cilia to the nucleus [80]. While the mechanisms of T2R import into nuclei remain to be determined, we hypothesize that, in de-ciliated or non-ciliated airway cells, the nuclear membrane may become a reservoir for GPCRs that would normally traffic to the cilia under conditions of normal differentiation.

An important consideration with determining the physiological relevance of intracellular GPCR localization is identifying the mechanism of activation on intracellular membranes. Agonists have to cross multiple lipid bilayers to activate an intracellular receptor; the normally extracellular side would be within the lumen of the ER, nucleoplasmic reticulum, or other organelle. However, many bitter molecules are hydrophobic or amphipathic. T2Rs have very little N and C terminal sequences [81]. The ligand binding pockets are within the transmembrane domains; hydrophobic interactions between transmembrane domains and amphipathic ligands are important for activation [82]. Several bitter and sweet molecules, including quinine, are cell permeant, rapidly entering into taste and other cells [83, 84]. Using the intrinsic fluorescence of quinine, Peri et al. visualized quinine uptake into taste cells, including into the nucleus [84]. Bacterial AHLs like 3-oxo-C12-HSL are also cell permeant [85, 86] and reach extracellular concentrations up to hundreds of μM in late stationary and biofilm cultures of P. aeruginosa [87, 88]. We hypothesize that colonization of bacteria during airway infection could generate localized AHL levels high enough to enter the cell and activate T2R Ca2+nuc signaling.

Bitter compounds denatonium, quinine, flufenamic acid, diphenidol, and diphenhydramine, as well as the T2R bacterial agonist 3-oxo-C12-HSL signal through Ca2+nuc and cAMPnuc. Except for being localized to the nucleus, these pathways are similar to T2R pathways in both taste cell and healthy upper airway cell models [5]. For the T2Rs or any GPCRs in the nucleus to regulate intracellular Ca2+, there must be nuclear membrane-localized heterotrimeric G proteins, PLC isoforms, IP3 receptors, etc. Ca2+nuc signaling may be distinct from cytosolic Ca2+ signaling, though regulated by similar IP3-dependent or ryanodine receptor pathways (reviewed in [37, 38]). In some early studies, increases in Ca2+nuc were thought to be tied to cytosolic Ca2+ [89], while recent studies suggest independent regulation [90-92]. Kar et al recently and elegantly demonstrated the presence of IP3 receptors on the inner nuclear membrane, facing the nucleoplasm [39], confirming some other earlier studies suggesting other upstream components of the GPCR signaling cascade also exist within the nucleus [37, 91]. Future biochemical and/or immunofluorescence studies are needed to determine the presence and localization of G proteins and PLC isoforms within airway cell nuclei.

Our data also suggest that T2R-dependent elevations in Ca2+nuc originate at least partly from the ER Ca2+ stores. The nuclear envelope is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum, containing both IP3Rs and RyRs on the inner nuclear membrane. Thus, the nuclear envelope is itself is a Ca2+ store capable of releasing Ca2+ into the nucleus (reviewed in [37, 38]). Invaginations, tubules, or sheets of inner nuclear envelope membrane can form a nucleoplasmic reticulum in many cells that also serves as an intranuclear Ca2+ store and signaling hub (reviewed in [38]). Small (~50 nm) membrane-bound vesicles in the nucleoplasm may also contain IP3 receptors and facilitate nuclear GPCR Ca2+ signaling [93]. Ca2+ microdomains may be created by restricted diffusion across the nuclear membrane or nuclear pore complexes and/or Ca2+ buffering from the nucleoplasmic reticulum or other organelles like ER or mitochondria [94, 95]. Mitochondrial-to-nuclear Ca2+ signaling was proposed to regulate gene expression via Ca2+-activated transcription factors [96, 97]. Our data here suggest that nuclear-to-mitochondrial Ca2+ can regulate apoptosis.

Notably, future studies are also needed to determine the identity of the Gα isoforms (Gαi isoforms 1,2, or 3 or Gα-gustducin) that nuclear T2Rs use to decrease cAMP, as well as the identity of the nuclear adenylyl cyclase and/or phosphodiesterase isoforms. Because we see a reduction in cAMP in cells in HBSS (with presumably no exogenous stimuli to elevate cAMP), it suggests that baseline cAMP is likely low but not completely abscent. The cAMP can likely decrease below baseline levels. We previously saw cytoplasmic cAMP decreases with T2R stimulation in airway cell lines and macrophages [98, 99]. Others have shown that opioid receptor stimulation can lower baseline cAMP in HEK293Ts [100]. We now report here that the same thing occurs with nuclear cAMP. The biosensors for cAMP are largely based on EPAC, but they have mutations engineered to make them higher affinity for cAMP than native EPAC. Thus, the lowering of cAMP detected by the high affinity sensors may or may not have physiological relevance depending on if the native cAMP-sensing proteins (EPAC or PKA) can detect these changes. Regardless, the lowering of nuclear cAMP is a proof of principle of the T2R signaling pathway in the nucleus. Furthermore, T2R-mediated reductions in cAMP may blunt cAMP increases during times of co-stimulation of Gs-coupled cAMP-elevating GPCRs like β2 adrenergic receptors. Future work is needed to closely dissect out mechanisms of nuclear cAMP regulation in airway epithelial cells.

Activation of T2Rs in primary human sinonasal ciliated cells results in increased Ca2+-dependent NO synthesis and ciliary beat frequency [6]. Here, we show that in non-ciliated airway cells, bitter compounds retain the ability to activate NO production, presumably acting as an innate host defense mechanism against infection. Notably, while eNOS is localized to the cilia or base of the cilia in airway epithelial cells [101], eNOS has also been localized to the nucleus in some cells [65, 102-104]. Altered localization of eNOS to the nucleus by loss of cilia may facilitate coupling T2Rs to NO despite their altered localization. T2Rs have been implicated in bronchial airway smooth muscle relaxation [105-107]. NO is also linked to airway smooth muscle relaxation, possibly by through reducing Ca2+ oscillations [108]. Here, we demonstrate that bitter agonists increase NO production via NOS and thus elevate cGMP levels. While NO produced in epithelial cells may be used as a direct defense towards bacterial infection, it may also contribute to airway smooth muscle relaxation.

There have been numerous studies detailing the role of both bitter compounds and bacterial products such as 3-oxo-C12-HSL have in cell survivability and apoptosis in a variety of cell types [54, 109-114]. We suggest these observations may be related to Ca2+nuc. Ca2+nuc is linked to cell proliferation [115] and regulation of transcription factors such as ATF3 and CREB [68, 116, 117]. Other studies have also linked nuclear Ca2+ to apoptotic cell death [118, 119]. Bitter compounds have been linked to halting proliferation [54, 63]. Specifically, denatonium benzoate has been shown inhibit cell proliferation, alter ΔΨm, and release cytochrome c from the mitochondria, thus leading to apoptosis in airway epithelial lines A549 and 16HBE [54]. Our data support these findings; cell growth is immediately halted and after an hour of treatment apoptosis commences. However, we extend these studies by identifying mechanisms of bitterant-induced death. Alterations in ΔΨm and initiation of apoptosis can be blocked by disrupting Ca2+ signaling.

The promiscuous nature of bitter compounds acting as agonists for multiple T2Rs adds a layer of complexity in teasing out specific downstream signaling of any one individual T2R. However, this redundancy may be of evolutionary advantage as a ‘last resort’ defense mechanism for any pathogen that manages to infiltrate past the apical layer of differentiated cells in the airway. This might occur in patients with CRS or COPD with loss of protective ciliated cells. It remains to be determined if activation of T2R-induced apoptosis by bacterial products like 3-oxo-C12-HSL are detrimental or beneficial in non-ciliated epithelial cells. The answer may depend on disease context.

Notably, the concentrations of denatonium (≥5-15 mM) necessary to evoke a Ca2+nuc response and alter cellular metabolism (≥1-10 mM) are somewhat high. A saturating (15 mM) denatonium concentration for Ca2+nuc was used for mechanistic studies to dissect out the Ca2+nuc pathway. T2Rs are comparably low affinity receptors compared with many other GPCRs, likely due to the fact that they come into high contact with bitter agonists in food [5]. Denatonium-responsive T2Rs 4, 39, and 43 have effective concentrations (ECs; defined as the lowest denatonium concentration that elicits a response) of 100-300 μM, while T2R8 has an EC of ~1 mM for denatonium [34]. These T2R ECs for denatonium and other agonists come from heterologous expression studies where the receptors are tagged with the first 45 amino acids of rat SSTR3 (or sometimes rhodopsin) to promote trafficking to the plasma membrane [34, 120]. When T2Rs are intracellularly expressed, the intracellular concentration of denatonium, quinine, or any other agonist used may initially be less than what is in our extracellular bath solution, depending on the diffusion rates of the molecules across the plasma membrane. A study of membrane permeant tastants [83] (note denatonium was not used in the study) showed that permeation of bitter agonists into oral cells increases over ≥8 min. Thus, the concentration that nuclear receptors are seeing in acute studies over 5-10 min may be somewhat less than what is outside the cells. This may explain why slightly lower denatonium concentrations (1-3 mM) that do not initially elicit a Ca2+nuc response did affect cell metabolism measured by XTT assay. These concentrations may increase over time to threshold over time that does increase Ca2+. Alternatively, there may be lower level Ca2+nuc responses at these lower concentrations that are buffered out or simply not detected by the R-GECO1.0 biosensor used. The published Kd is is 482 nM [33], but those measurements are made from the cytoplasm. The behavior of the sensor may be slightly different in the nucleus depending on the local environment. If the affinity is too high, the biosensor may buffer out low level responses. If the affinity is too low, it may miss low level responses. Future studies, perhaps with NLS-tagged ratiometric Ca2+ indicators, are needed to quantitate absolute Ca2+ concentrations in airway epithelial cell nuclei.

Lastly, we confirm that HEKs express many endogenous T2Rs that signaling though Ca2+ and cAMP. The lower threshold for activation of Ca2+ responses by bitter compounds observed after transfection of tagged T2Rs may be due partly to an increase in receptor numbers but may also be due to an increase in plasma membrane localization due to construct tagging. We suggest caution when using HEK cells as an expression model for T2Rs.

4. Materials and Methods

Unless noted otherwise, all protocols were used as previously described [8, 121, 122]. Catalogue numbers for reagents used are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

4.1. Human primary cell culture

Primary human sinonasal cell culture was carried out as extensively described [8, 59, 122]. Tissue acquisition was done in accordance with The University of Pennsylvania guidelines for the use of residual clinical material and in accordance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services code of federal regulation Title 45 CFR 46.116 and the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review board approval (#800614) and written informed consent from each patient was obtained. Tissue was used from patients ≥18 years of age undergoing surgery for sinonasal disease (CRS) or other procedures (e.g. trans-nasal approaches to the skull base for pituitary tumors).

Human primary nasal epithelial cells were obtained through enzymatic dissociation of human sinonasal tissue and cultured as described [6]. Human primary bronchial epithelial cells were procured commercially (Cat.# CC-2540S, Lonza). For isolation of primary nasal epithelial cells, patient sinonasal specimens were digested in MEM culture medium containing 1.4 mg/ml protease and 0.1 mg/ml DNase for 1 hour at 37°C followed by 2 neutralizing washes with MEM culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cell suspension was transferred to a T-25 culture flask containing PneumaCult-Ex Plus culture medium (Cat.# 05040, Stemcell Technologies) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 2 hours to allow for adherence and removal of non-epithelial cells (e.g. fibroblasts, macrophages and lymphocytes). The cell suspension containing only nasal epithelial cells was then transferred to a 10 cm tissue culture dish containing PneumaCult-Ex Plus culture medium and left in the incubator overnight. The following day, the culture medium was aspirated and the cells washed once with sterile PBS and replaced with fresh PneumaCult-Ex Plus culture medium. Both nasal and bronchial primary epithelial cells were passaged every 4-5 days or when cultures achieved 80% confluence. Primary human bronchial epithelial cells were obtained from Lonza and cultured as above.

For deciliation experiments, Normal human bronchial epithelial cells (HBE) air liquid interface cultures (ALIs) were differentiated for 3 weeks and either exposed to air or subjected to submersion for 4 days as previously described [59]. All comparisons were made between age-matched cultures. Cells were stimulated apically for 3-6 hours with 10 mM sodium benzoate (Na benzoate), 10 mM denatonium benzoate (denat. benz.), 600 μM thujone, or 100 μM 3oxoC12HSL or no stimulation HBSS alone.

Cells were then stained with annexin V-FITC assay kit (Cayman Chemical Cat. # 600300). Fluorescence was immediately imaged at the center of the ALI on a wide-field fluorescence microscope with 10x objective. TAS2R38 genotype was carried out as previously described [6]. The TAS2R38 gene encoding the T2R38 receptor has two common polymorphisms that are Mendelianly-distributed in the Philadelphia population [123-125]. The PAV allele encodes a functional receptor while the AVI allele encodes a non-functional receptor [16]. ALIs from PAV/PAV homozygous patient cells exhibit Ca2+ responses to T2R38-specific agonist PTC while ALIs from AVI/AVI homozygous patient cells do not [6].

4.2. Cell line culture and generation of stable shRNA cell lines

Cell culture was as described [8, 59] in Minimal Essential Media with Earl’s salts (Gibco; Gaithersburg, MD USA) plus 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). BEAS-2B (adenovirus 12-SV40 hybrid immortalized bronchial), A549 (alveolar type II-like carcinoma), HEK293T, NCI-H292 (lung mucoepidermoid carcinoma expressing T2R14 [52]), and Caco-2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma) cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA USA). 16HBE (SV-40 immortalized bronchial) cells [30] were from D. Gruenert (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA USA). Transfections used Lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham MA). After transfection with shRNA plasmids for either T2R8, T2R10, T2R14, or scramble shRNA for stable expression, Beas2B cells were supplemented with 1 μg/mL puromycin for 1 week and then maintained in 0.2 μg/mL puromycin.

4.3. Live cell imaging

Unless noted, imaging was as described [8, 59]. For Ca2+, cells were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-AM or Fluo-8-AM for 1 hour in HEPES-buffered Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) at room temperature in the dark. Cells were loaded with 10 μM DAF-FM diacetate for 1.5 hours. Fura-2 was imaged using an Olympus IX-83 microscope (20x 0.75 NA objective), fluorescence xenon lamp with excitation and emission filter wheels (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA USA), Orca Flash 4.0 sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu, Tokyo, Japan) and MetaFluor (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA USA) using a Fura-2 filters (79002-ET, Chroma, Rockingham, VT USA). Imaging of Fluo-8 or DAF-FM used a FITC filter set (49002-ET, Chroma). For nuclear Ca2+ or cAMP, plasmids for G-GECO, R-GECO-nls, Flamindo2 or nls-Flamindo2 were transfected 48 hours prior to imaging. Images were taken with FITC or TRITC filters. Annexin V-FITC was imaged at 10x (0.4 NA). Twenty to thirty cells per experiment were used for calculations.

4.4. Proliferation, mitochondrial membrane potential, and apoptosis measurements

Cells were cultured at sub-confluent density in 24-well glass bottom plates (CellVis). XTT (sodium 3’-[1- (phenylaminocarbonyl)- 3,4- tetrazolium]-bis (4-methoxy6-nitro) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate) was added to sub-confluent cells immediately before absorbance measurements at 475nm (specific absorbance) and 660nm (reference) with Spark 10M plate reader (Tecan; Mannedorf, Switzerland). JC-1 dye was added 10 min prior to recording (ex.488/em.535 and em.590) while CellEvent Caspase 3/7 (ThermoFisher) was added immediately prior to recording (ex.495/em.540).

4.5. Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature followed by a simultaneous blocking/permeabilization in phosphate saline buffer containing 5% normal donkey serum, 1% bovine serum albumun, 0.2% saponin, and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 45 min at room temperature. Cultures were incubated in primary antibody, 1:100 dilutions of T2R or α-gustducin antibodies, at 4°C overnight. Cultures were then incubated with AlexaFluor-labeled donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit (1:1000) at 4°C for 1 hour then mounted with Fluoroshield with DAPI (Abcam). All microscopy images were taken on an Olympus IX-83 microscope using x60 objective (1.4 NA oil; MetaMorph software). For ectopic expression: Myc-T2R10, myc-T2R39, GFP-T2R39, and T2R39-GFP expression constructs obtained from VectorBuilder (Chicago, IL). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000. Thermo MitoTracker Deep Red FM used at 10 nM for 15m pre-incubation at 37° C before fixing with 4% PFA then staining DAPI ± Golgin-97 antibody (Life Technologies, A21270, 1:100; anti-mouse AF488 secondary 1:1000). For co-staining of T2R14 and T2R38 in primary cell cilia, rabbit primary antibodies were labeled with Xenon AlexaFluor 488 or 546 conjugated fab fragments using Zenon antibody labeling kit (ThermoFisher; Cat # Z25302 and Z25304, respectively).

4.6. Western blotting and nuclear isolation

For endogenous T2R Western blot analysis, cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, DNase, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche complete). Post 800 x g lysates (60 μg protein/lane) were loaded in a NuPage 4-12% Bis-Tris gel. Separated proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose. Membrane was blocked in 5% milk in 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.025% Tween-20 (Tris-Tween) for 1 hour. Primary antibody was used at 1:1000 dilution in Tris-Tween with 5% BSA for 1.5 hours. Secondary antibodies of goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase were diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer then incubated with membrane for 1 hour. Blots were incubated for 5 min with Clarity ECL (BioRad Laboratories) and images were obtained using a BioRad Gel Doc, subsequent images and densitometry was analyzed using Image Lab Software (BioRad Laboratories). Nuclei were isolated using the REAP method [126] then either used for biochemistry or fixed on glass slides (4% formaldehyde in PBS, 15 min), stained as above, and imaged.

4.7. Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Subconfluent cultures were resuspended in TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific) and used immediately or otherwise stored at −70°C until use. RNA was isolated using Direct-zol RNA kit (Zymo Research). Once purified, RNA was transcribed to cDNA via High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Resulting cDNA was then quantified utilizing Taqman Q-PCR probes in a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific). Data was then analyzed using Microsoft Excel and plotted in GraphPad PRISM.

4.8. Data analysis and statistics

T-tests (two comparisons only) and one-way ANOVA (>2 comparisons) were calculated using GraphPad PRISM with appropriate post-tests. For comparisons of all samples, Tukey-Kramer posttest was used, while Bonferonni post-test was used for selected pairwise comparisons. Any other data analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel. In all Fig.s, p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), while no statistical significance was represented by “n.s.” All data points represent the mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

De-ciliated squamous airway cells express intracellular T2R bitter taste receptors

Intracellular bitter taste receptors activate nuclear and mitochondrial calcium elevation

Calcium elevation causes depolarization of mitochondrial membrane and caspase activation

Blocking calcium signaling prevents apoptosis

Acknowledgments

We thank Maureen Victoria (University of Pennsylvania) for technical assistance and thoughtful discussion and Andrew Ramsey (University of Pennsylvania) and Alfred Sloan (Synthego) for helpful advice and discussion.

Funding Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01DC016309. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing, or the decision to submit.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Derek McMahon: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Li Eon Kuek, Madeline E Johnson, Paige O Johnson, Rachel LJ Horn: Investigation. Ryan M. Carey, Nithin D. Adappa, James N. Palmer: Resources, Data curation, Project administration. Robert J Lee: Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing interests

Data Availability

The data supporting this manuscript's conclusion are included in the main text file and supporting information. Raw numerical values used to generate graphs are available upon request. New plasmid constructs created during this study are also available upon request.

REFERENCES

- [1].Stevens WW, Lee RJ, Schleimer RP, Cohen NA, Chronic rhinosinusitis pathogenesis, J Allergy Clin Immunol, 136 (2015) 1442–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shapiro A, Davis S, Manion M, Briones K, Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 198 (2018) P3–p4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mall MA, Danahay H, Boucher RC, Emerging Concepts and Therapies for Mucoobstructive Lung Disease, Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 15 (2018) S216–s226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kuek LE, Lee RJ, First contact: the role of respiratory cilia in host-pathogen interactions in the airways, Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 319 (2020) L603–L619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Carey RM, Lee RJ, Taste Receptors in Upper Airway Innate Immunity, Nutrients, 11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee RJ, Xiong G, Kofonow JM, Chen B, Lysenko A, Jiang P, Abraham V, Doghramji L, Adappa ND, Palmer JN, Kennedy DW, Beauchamp GK, Doulias PT, Ischiropoulos H, Kreindler JL, Reed DR, Cohen NA, T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection, J Clin Invest, 122 (2012) 4145–4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jaggupilli A, Singh N, Jesus VC, Duan K, Chelikani P, Characterization of the Binding Sites for Bacterial Acyl Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) on Human Bitter Taste Receptors (T2Rs), ACS Infect Dis, 4 (2018) 1146–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hariri BM, McMahon DB, Chen B, Freund JR, Mansfield CJ, Doghramji LJ, Adappa ND, Palmer JN, Kennedy DW, Reed DR, Jiang P, Lee RJ, Flavones modulate respiratory epithelial innate immunity: Anti-inflammatory effects and activation of the T2R14 receptor, J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 8484–8497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shah AS, Ben-Shahar Y, Moninger TO, Kline JN, Welsh MJ, Motile cilia of human airway epithelia are chemosensory, Science, 325 (2009) 1131–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marcinkiewicz J, Nitric oxide and antimicrobial activity of reactive oxygen intermediates, Immunopharmacology, 37 (1997) 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fang FC, Perspectives series: host/pathogen interactions. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-related antimicrobial activity, J Clin Invest, 99 (1997) 2818–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wink DA, Hines HB, Cheng RY, Switzer CH, Flores-Santana W, Vitek MP, Ridnour LA, Colton CA, Nitric oxide and redox mechanisms in the immune response, J Leukoc Biol, 89 (2011) 873–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Akerstrom S, Mousavi-Jazi M, Klingstrom J, Leijon M, Lundkvist A, Mirazimi A, Nitric oxide inhibits the replication cycle of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, J Virol, 79 (2005) 1966–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Akerstrom S, Gunalan V, Keng CT, Tan YJ, Mirazimi A, Dual effect of nitric oxide on SARS-CoV replication: viral RNA production and palmitoylation of the S protein are affected, Virology, 395 (2009) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Akaberi D, Krambrich J, Ling J, Luni C, Hedenstierna G, Jarhult JD, Lennerstrand J, Lundkvist A, Mitigation of the replication of SARS-CoV-2 by nitric oxide in vitro, Redox Biol, 37 (2020) 101734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bufe B, Breslin PA, Kuhn C, Reed DR, Tharp CD, Slack JP, Kim UK, Drayna D, Meyerhof W, The molecular basis of individual differences in phenylthiocarbamide and propylthiouracil bitterness perception, Curr Biol, 15 (2005) 322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yaghi A, Dolovich MB, Airway Epithelial Cell Cilia and Obstructive Lung Disease, Cells, 5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tilley AE, Walters MS, Shaykhiev R, Crystal RG, Cilia dysfunction in lung disease, Annu Rev Physiol, 77 (2015) 379–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gudis D, Zhao KQ, Cohen NA, Acquired cilia dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis, Am J Rhinol Allergy, 26 (2012) 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chaaban MR, Kejner A, Rowe SM, Woodworth BA, Cystic fibrosis chronic rhinosinusitis: a comprehensive review, Am J Rhinol Allergy, 27 (2013) 387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mynatt RG, Do J, Janney C, Sindwani R, Squamous metaplasia and chronic rhinosinusitis: a clinicopathological study, Am J Rhinol, 22 (2008) 602–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pawankar R, Nonaka M, Inflammatory mechanisms and remodeling in chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps, Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, 7 (2007) 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gohy ST, Hupin C, Fregimilicka C, Detry BR, Bouzin C, Gaide Chevronay H, Lecocq M, Weynand B, Ladjemi MZ, Pierreux CE, Birembaut P, Polette M, Pilette C, Imprinting of the COPD airway epithelium for dedifferentiation and mesenchymal transition, Eur Respir J, 45 (2015) 1258–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gao W, Li L, Wang Y, Zhang S, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, Huang M, Yao X, Bronchial epithelial cells: The key effector cells in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?, Respirology (Carlton, Vic.), 20 (2015) 722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jeffery PK, Brain AP, Surface morphology of human airway mucosa: normal, carcinoma or cystic fibrosis, Scanning Microsc, 2 (1988) 553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu NH, Yang W, Beineke A, Dijkman R, Matrosovich M, Baumgartner W, Thiel V, Valentin-Weigand P, Meng F, Herrler G, The differentiated airway epithelium infected by influenza viruses maintains the barrier function despite a dramatic loss of ciliated cells, Sci Rep, 6 (2016) 39668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lachowicz-Scroggins ME, Boushey HA, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, Interleukin-13-induced mucous metaplasia increases susceptibility of human airway epithelium to rhinovirus infection, Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 43 (2010) 652–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Montoro DT, Haber AL, Biton M, Vinarsky V, Lin B, Birket SE, Yuan F, Chen S, Leung HM, Villoria J, Rogel N, Burgin G, Tsankov AM, Waghray A, Slyper M, Waldman J, Nguyen L, Dionne D, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Tata PR, Mou H, Shivaraju M, Bihler H, Mense M, Tearney GJ, Rowe SM, Engelhardt JF, Regev A, Rajagopal J, A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes, Nature, 560 (2018) 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Munye MM, Shoemark A, Hirst RA, Delhove JM, Sharp TV, McKay TR, O'Callaghan C, Baines DL, Howe SJ, Hart SL, BMI-1 extends proliferative potential of human bronchial epithelial cells while retaining their mucociliary differentiation capacity, Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 312 (2017) L258–L267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gruenert DC, Willems M, Cassiman JJ, Frizzell RA, Established cell lines used in cystic fibrosis research, J Cyst Fibros, 3 Suppl 2 (2004) 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ke Y, Reddel RR, Gerwin BI, Miyashita M, McMenamin M, Lechner JF, Harris CC, Human bronchial epithelial cells with integrated SV40 virus T antigen genes retain the ability to undergo squamous differentiation, Differentiation, 38 (1988) 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gomes DA, Rodrigues MA, Leite MF, Gomez MV, Varnai P, Balla T, Bennett AM, Nathanson MH, c-Met must translocate to the nucleus to initiate calcium signals, J Biol Chem, 283 (2008) 4344–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T, Campbell RE, An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca(2)(+) indicators, Science, 333 (2011) 1888–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Meyerhof W, Batram C, Kuhn C, Brockhoff A, Chudoba E, Bufe B, Appendino G, Behrens M, The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors, Chem Senses, 35 (2010) 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nishimura A, Kitano K, Takasaki J, Taniguchi M, Mizuno N, Tago K, Hakoshima T, Itoh H, Structural basis for the specific inhibition of heterotrimeric Gq protein by a small molecule, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107 (2010) 13666–13671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Peng Q, Alqahtani S, Nasrullah MZA, Shen J, Functional evidence for biased inhibition of G protein signaling by YM-254890 in human coronary artery endothelial cells, European journal of pharmacology, (2020) 173706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Alonso MT, García-Sancho J, Nuclear Ca(2+) signalling, Cell calcium, 49 (2011) 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Malhas A, Goulbourne C, Vaux DJ, The nucleoplasmic reticulum: form and function, Trends in cell biology, 21 (2011) 362–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kar P, Mirams GR, Christian HC, Parekh AB, Control of NFAT Isoform Activation and NFAT-Dependent Gene Expression through Two Coincident and Spatially Segregated Intracellular Ca(2+) Signals, Mol Cell, 64 (2016) 746–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Petersen OH, Gerasimenko OV, Gerasimenko JV, Mogami H, Tepikin AV, The calcium store in the nuclear envelope, Cell calcium, 23 (1998) 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gerasimenko JV, Maruyama Y, Yano K, Dolman NJ, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH, Gerasimenko OV, NAADP mobilizes Ca2+ from a thapsigargin-sensitive store in the nuclear envelope by activating ryanodine receptors, The Journal of cell biology, 163 (2003) 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Palmer AE, Jin C, Reed JC, Tsien RY, Bcl-2-mediated alterations in endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ analyzed with an improved genetically encoded fluorescent sensor, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 101 (2004) 17404–17409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Velmurugan GV, White C, Calcium homeostasis in vascular smooth muscle cells is altered in type 2 diabetes by Bcl-2 protein modulation of InsP3R calcium release channels, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 302 (2012) H124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee RJ, Cohen NA, Sinonasal solitary chemosensory cells "taste" the upper respiratory environment to regulate innate immunity, Am J Rhinol Allergy, 28 (2014) 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kim D, Woo JA, Geffken E, An SS, Liggett SB, Coupling of Airway Smooth Muscle Bitter Taste Receptors to Intracellular Signaling and Relaxation Is via Galphai1,2,3, Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 56 (2017) 762–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lee RJ, Chen B, Redding KM, Margolskee RF, Cohen NA, Mouse nasal epithelial innate immune responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecules require taste signaling components, Innate Immun, 20 (2014) 606–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]