Abstract

Myelin oligodendrocyte-antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) often presents with severe optic neuritis (ON) but tends to recover better than in aquaporin-4 antibody neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (AQP4-NMOSD). We measured OCT and VEP in MOGAD and AQP4-NMOSD eyes with good visual function, with or without previous ON episodes. Surprisingly, OCT and/or VEPs were abnormal in 84% MOGAD-ON versus 38% AQP4-NMOSD-ON eyes (p = 0.009) with good vision, compared with 18% and 17% respectively of eyes with no previous ON. A sub-group with macular OCT performed as part of a research study confirmed both retinal and macular defects in visually-recovered MOGAD eyes. These findings have implications for investigation and management of MOGAD patients.

Keywords: Neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease (MOGAD) opticcoherence tomography (OCT), visual evoked potentials (VEP), Visual function, Optic Neuritis

Introduction

Aquaporin-4 antibody neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (AQP4-NMOSD) and myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease (MOGAD) often present with recurrent attacks of optic neuritis (ON) but visual recovery is generally better in MOGAD-ON than in AQP4-NMOSD ON.1,2 It is assumed that optic coherence tomography (OCT) and visual evoked potentials (VEPs) reflects visual recovery, however, our observations are that some MOGAD patients with good visual recovery from ON had very abnormal clinical OCT results. 3 This study was designed to review systematically this observation comparing MOGAD with AQP4-NMOSD patients to see if OCT (and VEPs) were more sensitive in MOGAD in those with good vision

Methods

Patients where OCT had occurred at least 6 months post ON attack were recruited from the Oxford NMO nationally commissioned service. Only results from eyes with good central visual acuity (VA) defined as LogMar ≤ 0 (best corrected score on the retro-illuminated ETDRS chart) were included, and OCT and visual evoked potentials (VEP) results were analysed.

For the clinical study MOGAD or AQP4-NMOSD patients with both clinical OCTs (peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, pRNFL) and VEP measurements were included. OCT scans for all patients were performed on Heidelberg Spectralis OCT machines at the Eye Clinic at the John Radcliffe hospital under the same scanning protocol. The peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer (pRNFL) was measured with an activated eye tracker using 3.4 mm ring scans around the optic nerve (12°, 1536 A-scans, 1 ≤ ART ≤ 99). Definition of abnormality was taken from the Heidelberg Spectralis reports. VEPs were performed in different clinical laboratories, in different hospitals and on different machines; therefore, abnormality was defined according to the local neurophysiology laboratory definition.

In order to validate the clinical cohort, allowing for validation and quality control, as well as the relation with macular data we carried out a macular sub-study. For this analysis we used the same Spectralis spectral-domain devices (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) with automatic real-time function for image averaging to measure disc (pRNFL) and OCT macular volumes calculated as a 3 mm diameter cylinder around the fovea. Segmentation of all layers was performed semi-automatically using Eye explorer (version 1.10.4.0. with viewing module 1.0.16.0. Heidelberg Engineering). One experienced rater adriana roca-fernandez (ARF) carefully checked all scans for sufficient quality and segmentation errors and corrected when necessary. OCT data in this study are reported according to the APOSTEL recommendations. The QC process discarded 2 AQP4-NMOSD and 2 MOGAD eyes due to bad imaging quality. The reference range for abnormality in these scans has been defined as the 5th quantile of the healthy controls (HC) cohort. To calculate differences between groups we performed linear mixed effect (LME) models, accounting for inter-eye correlations of monocular measurements, and adjusting by age and sex. Estimated regression coefficients (B), standard errors (SE) and p values are provided in the results section.

Consent obtained under ethics 16/SC/0224 and 17/EE/0246.

Results

Clinical cohort

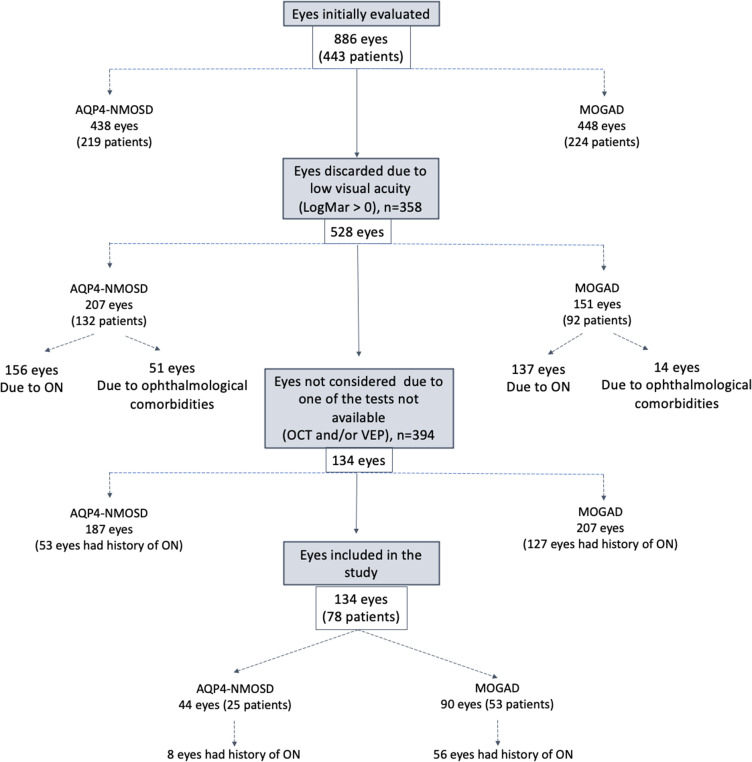

From our service of 219 AQP4 patients and 224 MOGAD patients, 358 eyes were discarded due to reduced visual acuity (logMAR>0): 293 due to ON (137 in MOGAD patients, 156 in AQP4-NMOSD patients) and 65 were discarded due to other comorbid eyes diseases (age related eye disorders and systemic autoimmune diseases with ophthalmological involvement – the majority in AQP4-NMOSD patients) (Figure 1). Only patients with both clinical Oxford OCT and any VEPs performed (where an ON attack occurred > 6 months after onset) were included. Data was available for analysis on 53 MOGAD patients with 90 good VA eyes and 25 AQP4-NMOSD patients with 44 good VA eyes. Of these, 56/90 MOGAD eyes (62%) and 8/44 AQP4-NMOSD eyes (18%) had history of one or more ON episodes (median number of ON, 1.5 for AQP4-NMOSD, 1 for MOGAD) (Table 1) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of cohort selection.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics.

| MOGAD | AQP4-NMOSD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number patients | 53 | 25 | ||||

| Males / Females | 33/29 | 21/4 | ||||

| Age years median (range) | 35 (11–73) | 57 (17–83) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 43 White (81.1%) 0 African-Caribbean (0%) 3 Asian (5.7%) 1 Mixed race (1.9%) 6 Prefer not to say (11.3%) |

16 White (64%) 8 African-Caribbean (32%) 1 Asian (4%) |

||||

| No. Patients with past history of optic neuritis | 28 | 5 | ||||

| - Time from ON to OCT, median (range) in months | 32 (6–124) | 44 (17–98) | ||||

| No. Patients with no past history of optic neuritis | 25 | 20 | ||||

| OCT examination | ||||||

| Both eyes examined (patients) | 74 (37) | 38 (19) | ||||

| Patients with concordant OCT result in both eyes | 26 | 18 | ||||

| Patients with discordant OCT result in both eyes | 11 | 1 | ||||

| One eye only examined -other eye poor VA post ON (patients) | 16(16) | 6 (6) | ||||

| Ophthalmic test results | ||||||

| TOTAL | ON | No-ON | TOTAL | ON | No-ON | |

| OCT and VEP examination normal, N | 37 | 9 | 28 | 35 | 5 | 30 |

| OCT examination abnormal, N | 21 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| VEP examination abnormal, N | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| OCT and VEP examination abnormal, N | 26 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

Note: Age and sex group differences between MOGAD and AQP4-NMOSD patients were significant (Fisher's exact tests for sex, p = 0.007; Wilcox test for age, p = 0.001). Differences between normal Vs abnormal ophthalmic examinations were assessed with Fisheŕs exact test and significant between MOGAD and AQP4-NMOSD for the Total number of eyes (p ≤ 0.001) and ON eyes (p = 0.009).

Abbreviations: ARF, Adriana Roca-Fernandez; BMOMRW, Bruch´s membrane opening based minimum rim width; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; GCIP, ganglionar and inner plexiform retinal layer; HC, healthy control; IS, immunosuppression; MOGAD, Myelin Oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease; MRI, magneticresonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMO, Neuromyelitis Optica; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; NON, no history ofoptic neuritis; OCTs, optic coherence tomography (in plural); QC, quality control; RNFL, retinal nerve fibre layer; N, number; AQP4-NMOSD, AQP4 seropositive Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease; OCT, Optic coherence tomography; VEP, Visual evoked potentials; VA, central visual acuity.

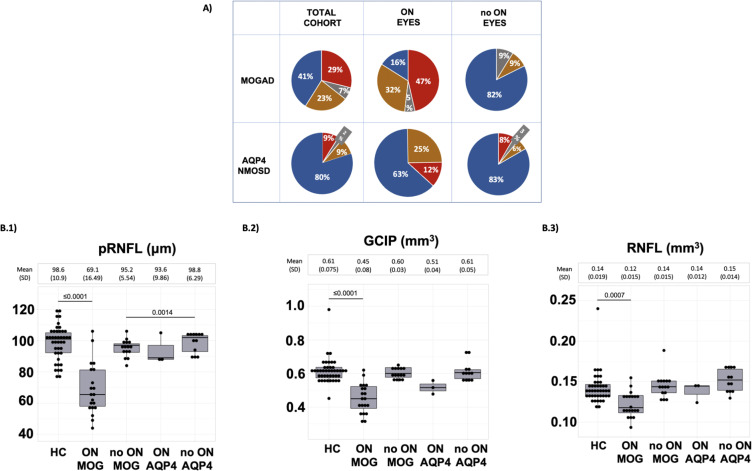

A summary of all results of clinical OCT and VEP measurements are shown in Fig 2A (Table 1). Whereas, the majority (80%) of AQP4-NMOSD eyes with good VA had normal VEP and OCT examinations, only 41% of MOGAD eyes with normal VA had normal findings, the remainder having abnormal OCT, VEP or both (p ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Comparisons between AQP4-NMOSD (AQP4) and MOGAD patients

*AQP4-NMOSD is referred in this table as AQP4 for simplicity.

(A) Clinical cohort grouped according abnormal OCT (orange); abnormal VEP (grey), both tests abnormal (red) or both tests normal (blue).

(B) Macular sub-study cohort grouped according disease group or HC group and ON or NON group, boxplot shows median, 25th and 75th percentile (B.1) pRNFL (B.2) GCIP (B.3) macular RNFL. Maximum likelihood was used for the estimation of p values.

Abbreviations: MOGAD, Myelin oligondendrocyte glycoprotein; AQP4, AQP4 seropositive Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease; OCT, Optic coherence tomography; ON, Only eyes that have had previous ON; no ON, Only eyes not have previous ON; pRNFL, peripapillar retinal nerve fibre layer; GCIP, ganglionar and inner plexiform layer; RNFL, macular retinal nerve fibre layer.

This difference between the two diseases was most apparent in those with normal VA and a previous ON (Figure 2A); only 16% of MOGAD eyes compared with 63% of AQP4-NMOSD eyes had normal investigations (p = 0.003) (Table 1). Notably, OCT abnormalities were more common than VEP abnormalities, with 79% MOGAD-ON patients having abnormal OCTs compared to 38% of AQP4-NMOSD-ON patients (p = 0.01).

Abnormalities were also noted in some eyes without a previous history of ON but without a difference between MOGAD (18%) of which 4/6 had a contralateral ON and AQP4-NMOSD (17%) of which none had a contralateral ON (p = 0.91) (Figure 2A).

Macular sub-study cohort

To further investigate these unexpected observations, we performed a macular sub-study in a subgroup of the above; 19 MOGAD patients (35/38 normal VA eyes), 9 AQP4-NMOSD (15/18 normal VA eyes), and 21 healthy individuals (42/42 normal VA eyes). From those, 20 MOGAD eyes and 3 AQP4-NMOSD eyes had histories of a median of 1 or 2 ON episodes respectively. Figure 2B(1–3) shows the pRNFL, macular retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) and ganglionar and inner plexiform retinal layer (GCIP) values for each group. The results confirmed a significant reduction in OCT values in the MOGAD ON group compared to HC not only in the pRNFL (B(SE) = −33.1(3.77), p ≤ 0.001), but also in the macular GCIP (B(SE): −0.18(0.02), p ≤ 0.001) and RNFL (B(SE): −0.020 (0.005), p = ≤ 0.001) parameters Figure 2B(1–3).

Discussion

This observational study demonstrates the sensitivity of OCT, greater than that of VEPs, in detecting subclinical damage in MOGAD-ON patients. Our macular sub-study OCT cohort demonstrated a similar pattern in macular OCT measurements, and confirmed our clinic observations where the majority of MOGAD patients continue to have abnormal tests despite recovering vision after an ON attack.

Given the much lower prevalence of abnormal tests (18%) in MOGAD patients who have never had ON compared to 84% of MOGAD ON patients, it is likely that the abnormal OCT and VEP results are mainly a direct consequence of an ON attack rather than an unrelated disease process. However, abnormalities still occurred in a moderate number of non-ON eyes.

Although we previously showed that AQP4-NMOSD-ON is associated with a worse visual outcome than MOGAD ON1,4,5 here we note that those patients who do recover good vision are more likely to have normal investigations than MOGAD-ON patients. Thus, by studying only patients with good visual recovery, we selected a smaller subgroup of AQP4-NMOSD patients than MOGAD patients because of the better clinical recovery in MOGAD. We excluded those with poor vision because OCT would be expected to be abnormal and thus has less diagnostic value. Sotirchos et al. 6 found worse visual recovery in AQP4-NMOSD with similar severity of macular GCIP thinning. We hypothesize that astrocyte damage in AQP4-NMOSD attacks might be more of an ‘all or nothing’ event and those that recover may have no secondary demyelination. Moreover, knowing that OCT and VEPs are also sensitive markers in MS, we have demonstrated that OCT (as done at a clinical level) and VEPs appear better at detecting primary demyelinating pathology as occurs in MOGAD. Although more AQP4-NMOSD patients overall were on IS the patients with normal vision post ON who had normal OCT were not on treatment as their attacks were prior to diagnosis and there was no evidence their attacks were milder.

This retrospective analysis has limitations. The diagnosis of ON in this study, as in routine clinical practice, was based on clinical signs and symptoms. We did not use the other eye as the normal control because many patients had bilateral ON and even in those without ON in the other eye a subset had abnormal OCT. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not routinely performed although it was used where the diagnosis was in doubt. Mild ON could have been missed and ON could have been diagnosed incorrectly but the NMOSD clinicians reviewed the patients’ symptoms and signs with the relevant neurologists/ophthalmologists and it is likely these errors would be small. Additionally, more AQP4-NMOSD patients were on immunosuppressive medication than MOGAD patients. However, we do not think these factors would not cause the observed differences between the two diseases noted. VEPs were performed at different centres with different reference ranges and equipment. Likewise, for the clinical cohort, we used the Heidelberg BMO-MRW Reference Database which includes only subjects of European descent. Retinal thickness variability between races, and the use of a single threshold in OCT could have underestimated abnormalities in the AQP4-Ab group with a greater proportion of patients of Afro-Caribbean origin. However, this aims to be pragmatic in order to be easily translated into clinical practice. We defined good visual function based upon central visual acuity, and visual fields were not systematically performed. We analysed all eyes measured whether or not they had paired observations, and did not distinguish between those with concordant ON eyes or those where only one eye was affected. A major strength is the use of a single centre for the clinical OCT tests performed under the same protocol and, in the case of the macular sub-study OCT analysis, segmented by the same person.

Our observations support the use of VEPs and OCT to determine the likelihood of previous visual symptoms being due to a MOGAD-ON. This is important because it could lead to an adjustment in the on-going immunosuppression. In addition, as sub-clinical abnormalities can occur without symptoms and although the relevance of the subclinical abnormalities is unknown, cumulative damage could well lead to clinical impairment and so close monitoring where it is noted is important. Hence, it is important to repeat the tests after each MOGAD relapse (i.e. to re-baseline the results) to provide comparison data should future visual symptoms occur.

Acknowledgements

NHS England for funding the Highly Specialized Diagnostic and Advisory Service for Neuromyelitis Optica

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: A Roca-Fernández https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8720-9397

S Messina https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1134-5771

Contributor Information

A Roca-Fernández, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University Of Oxford, UK; Department of Neurology/Neuroimmunology, Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia (CEMCAT), Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

V Camera, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University Of Oxford, UK.

G Loncarevic-Whitaker, University of Oxford Clinical Medical School, Medical Science Division, University of Oxford, UK.

S Sharma, Department of Ophthalmology, Oxford University Hospitals, National Health Service Trust, Oxford, UK.

References

- 1.Jurynczyk M, Messina S, Woodhall MR, et al. Clinical presentation and prognosis in MOG-antibody disease: a UK study. Brain J Neurol 2017; 01): 3128–3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujihara K, Misu T, Nakashima I, et al. Neuromyelitis optica should be classified as an astrocytopathic disease rather than a demyelinating disease. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol 2012; 3: 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filippatou AG, Mukharesh L, Saidha Set al. et al. AQP4-IgG And MOG-IgG related optic neuritis—prevalence, optical coherence tomography findings, and visual outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol [Internet], 2020 Oct 8; 11:540156. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.540156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobo-Calvo A, Ruiz A, Maillart E, et al. Clinical spectrum and prognostic value of CNS MOG autoimmunity in adults: the MOGADOR study. Neurology 2018 May 22; 90: e1858–e1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitley J, Leite MI, Nakashima I, et al. Prognostic factors and disease course in aquaporin-4 antibody-positive patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder from the United Kingdom and Japan. Brain J Neurol 2012 Jun; 135: 1834–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sotirchos ES, Filippatou A, Fitzgerald KC, et al. Aquaporin-4 IgG seropositivity is associated with worse visual outcomes after optic neuritis than MOG-IgG seropositivity and multiple sclerosis, independent of macular ganglion cell layer thinning. Mult Scler J 2020 Oct 1; 26: 1360–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]