Abstract

Objective

To explore the experiences of people living with long COVID and how they perceive the healthcare services available to them.

Design

Qualitative systematic review.

Data sources

Electronic literature searches of websites, bibliographic databases and discussion forums, including PubMed LitCovid, Proquest COVID, EPPI Centre living systematic map of evidence, medRxiv, bioRxiv, Medline, Psychinfo and Web of Science Core Collection were conducted to identify qualitative literature published in English up to 13 January 2021.

Inclusion criteria

Papers reporting qualitative or mixed-methods studies that focused on the experiences of long COVID and/or perceptions of accessing healthcare by people with long COVID. Title/abstract and full-text screening were conducted by two reviewers independently, with conflicts resolved by discussion or a third reviewer.

Quality appraisal

Two reviewers independently appraised included studies using the qualitative CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) checklist. Conflicts were resolved by discussion or a third reviewer.

Data extraction and synthesis

Thematic synthesis, involving line-by-line reading, generation of concepts, descriptive and analytical themes, was conducted by the review team with regular discussion.

Results

Five studies published in 2020 met the inclusion criteria, two international surveys and three qualitative studies from the UK. Sample sizes varied from 24 (interview study) to 3762 (survey). Participants were predominantly young white females recruited from social media or online support groups. Three analytical themes were generated: (1) symptoms and self-directed management of long COVID; (2) emotional aspects of living with long COVID and (3) healthcare experiences associated with long COVID.

Conclusions

People experience long COVID as a heterogeneous condition, with a variety of physical and emotional consequences. It appears that greater knowledge of long COVID is required by a number of stakeholders and that the design of emerging long COVID services or adaptation of existing services for long COVID patients should take account of patients’ experiences in their design.

Keywords: organisation of health services, quality in health care, infectious diseases, qualitative research, virology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review synthesises the existing qualitative literature on people’s experiences of long COVID and the healthcare services available to them.

The search strategy was comprehensive and sought to find published research, prepublication articles and grey literature.

The search was limited to the English language; therefore, potentially relevant studies may have been excluded.

Only five qualitative studies of variable quality were eligible for inclusion in this review, limiting the extent to which conclusions and practice recommendations can be made.

Participants in the included studies were predominantly younger, female and users of social media or online support groups, which may also limit the generalisability of the review findings.

Introduction

The long-term effects of COVID-19 are recognised increasingly as being heterogeneous and complex in nature. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a widespread perception that COVID-19 was an acute infection that resulted in death or recovery after 2 weeks.1 However, many people experienced wide-ranging and fluctuating symptoms for weeks or months after confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection. As these experiences were shared, on social media and other outlets, the term ‘long COVID-19’ was generated by patients.2 There remains no internationally agreed definition of long COVID, as COVID-19 is still a relatively new disease, with ongoing research on the long-term effects.3 Greenhalgh et al4 suggested ‘postacute COVID-19’ for symptoms lasting beyond 3 weeks after onset and ‘chronic COVID-19’ for those lasting beyond 12 weeks. Recent UK guidelines defined ‘ongoing symptomatic COVID-19’ as signs and symptoms lasting 4–12 weeks and ‘post-COVID-19 syndrome’ as signs and symptoms developing during or after COVID-19 and continuing beyond 12 weeks.5 6 As this systematic review is concerned with lived experience, we will use the patient-generated term long COVID to encapsulate all these definitions.

Symptoms of long COVID can affect those hospitalised and ventilated,3 as well as those with so-called mild COVID-19, during the acute phase.4 Little is known about long-term sequelae in asymptomatic patients, with this recently highlighted as an important area for future research.3 Potential long-term effects include central nervous system, psychosocial, cardiovascular, pulmonary, haematologic, renal and gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as widely reported persistent fatigue, dyspnoea, joint and chest pain.3 Estimates of long COVID rates vary from 10%4 to 35%7 with the true rate yet to be determined. Therefore, with over 108 000 000 confirmed COVID-19 cases globally as of 30 January 2021,8 there are now a large number of people at risk of long COVID.

Healthcare services specifically for long COVID are evolving. For example, some specialist centres have been set up in parts of the UK,9 and there has been a global call for the development of rehabilitation programmes and services for patients with long COVID.10 In order for healthcare services to meet patients’ needs, it is important to understand the experience of long COVID and of accessing healthcare services from patients’ perspectives. There is a growing body of qualitative research on the lived experience of long COVID and, to date, no published synthesis of this literature. The aim of this qualitative systematic review was therefore to explore the experiences of people living with long COVID and their perceptions of the healthcare services available to them.

Methods

A qualitative systematic literature review was undertaken based on an a priori protocol (available on request) and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.11 This review updates a review undertaken by the authors to inform the production of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) guideline on the management of long COVID.5 6

Inclusion criteria

Full details of the inclusion criteria for the review are given in online supplemental file 1.

bmjopen-2021-050979supp001.pdf (348.1KB, pdf)

Participants: Individuals experiencing long COVID whether suspected or confirmed by diagnostic test, with no restriction on duration of symptoms. We excluded studies on the views or experiences of healthcare for conditions other than COVID-19 and those relating to the views of healthcare staff, unless they were patients themselves.

Phenomena of interest: people’s views on and experiences of living with and managing long COVID and on the healthcare services available to them.

Context: Studies from any country and any setting.

Types of study: systematic reviews of qualitative studies; primary qualitative studies; and qualitative components of mixed method studies.

Information sources and search strategy

An information specialist (CM) carried out a search in October 2020. Sources searched included: PubMed LitCovid, Proquest COVID, EPPI Centre living systematic map of evidence, medRxiv, bioRxiv, Medline, PsychInfo and Web of Science Core Collection. A full list of resources searched is available in online supplemental file 2. Published studies, grey literature and prepublication articles were sought. In databases not specific to COVID-19, search results were limited to publications in 2020. All searches were limited to the English language due to a lack of translation services and the need for evidence to be synthesised in a timely manner due to the rapidly evolving nature of long COVID research. A search update was conducted on 13 January 2021.

Bibliographic database searches applied adapted versions of the qualitative research filter by DeJean et al12 and a filter for patient experience literature developed by combining terms from papers by Selva et al13 and Wessels et al.14 The search strategy for Medline is available in online supplemental file 2. Search strategies for other bibliographic databases are available on request.

Study selection

Citations were uploaded to EndNote software, and duplicates were removed. Records were screened against the inclusion criteria based on titles and abstracts by two reviewers independently (JH and DM). The same two reviewers then assessed the full text of potentially relevant articles. Disagreements were discussed and referred to a third reviewer where necessary. The two reviewers were in agreement for the majority of the papers, and only one study required recourse to the third reviewer (KM).

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted descriptive data from each study (KC, JH, KM, DM and MN), using a data extraction template designed specifically for this review. The reviewers then compared templates and resolved any discrepancies, which were few in number, by discussion. Details extracted from the studies included: country in which the study was conducted, method of data collection and analysis, phenomena of interest, setting/context/culture, participant characteristics and sample size, and a description of the main results. As this review was conducted in a short timescale, to provide early evidence on a rapidly evolving subject, we did not contact authors for missing information.

Quality appraisal

Included studies were critically appraised by two reviewers independently (KC, JH, KM, DM, MN and JH) using the CASP qualitative checklist (https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/). Discrepancies, which were minimal, were discussed and referred to a third reviewer if required. For the reasons described previously, authors were not contacted for additional information on methodology of their individual studies.

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis was undertaken on the findings from included studies.15 This involved: (1) line-by-line reading of each study by two reviewers independently (JH, KM and MN) to identify initial concepts; (2) grouping similar concepts into initial descriptive themes and subthemes and (3) generating the final analytical themes. These were discussed and agreed by the review team (KC, JH, KM, DM and MN) throughout the process, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion within the team.

Patient and public involvement

As a systematic review focused on published and grey literature no primary research involving patients was conducted. The original synthesis that this review updates was subject to review by an expert group that included several members with lived experience of long COVID and a targeted public consultation that included groups representing those with experience of this condition. Further details are provided within the NICE long COVID guideline.5

Results

Search results

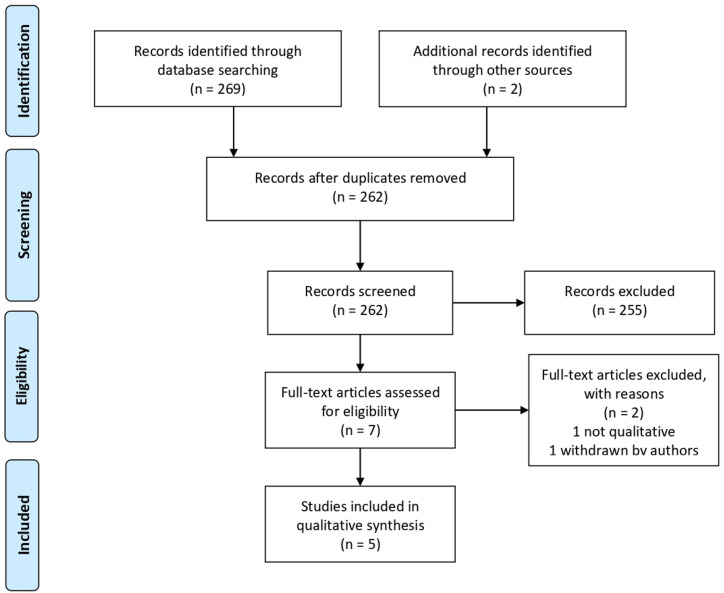

The literature search identified 269 articles. A further two studies were identified from reference lists. After removal of duplicates and title/abstract screening, seven articles were evaluated as full text. The main reasons for excluding articles were no qualitative element to the research, no patient involvement and not meeting our definition of long COVID (we were interested in studies relating to symptoms over 4 weeks’ duration). Out of the seven fully evaluated articles, one study was excluded because it did not use qualitative methods or contain data on direct patient experience. A second study that was initially included was later excluded after it was withdrawn from prepublication by the authors. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram depicting the study selection process is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

Five studies were included in the thematic synthesis (table 1).1 16–19 Three studies conducted focus groups or interviews with patients from the UK and two studies, from the Patient-Led Research group, conducted international surveys with most responses coming from the USA and the UK. Sample sizes varied from 24 interviews to 3762 survey respondents and were generally weighted towards white (83.8%), female participants (75%). The number of patients included in the studies in which information was gathered through surveys was much larger than those using interviews and focus groups as data collection methods. However, while representing fewer patients, the latter method offers the opportunity of collecting more in-depth data and for interaction among participants and/or with the interviewer. All studies focused on adults with an age range of 20–68 years in the four studies that reported participants’ ages; one study did not report the number of participants or their ages.1

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study (country) | Study methods and setting | Participant characteristics and sample size | Main results |

| Assaf et al (multinational)19 |

Online survey 21 April–2 May 2020 circulated to long COVID support groups and through social media. Quantitative and qualitative data collection. |

n=640 Patients with symptoms lasting >2 weeks 62.7% aged 30–49 years; 76.0% white; 76.6% female. |

Cyclical symptoms experienced unexpectedly for ≥6 weeks. Stigma experienced by patients with long COVID. Impacts on lifestyle, including physical activity. Dismissed or misdiagnosed by medical professionals . Sentiment analysis conducted on satisfaction with medical staff and on sharing experiences. |

| Davis et al (multinational)16 |

Online survey 6 September–25 November 2020 circulated to online patients support groups and social media. Quantitative and qualitative data collection. |

n=3762 Patients with symptoms lasting >28 days 60.8% aged 40–59; 85.3% white; 78.9% female. |

Patients with long COVID reported prolonged multisystem involvement and significant disability. The most frequent symptoms reported after 6 months were: fatigue, postexertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction. |

| Kingstone et al (UK)17 |

Recruitment through social media (Twitter or Facebook) and snowball sampling July–August 2020. Semistructured interviews by telephone or video call (duration 35–90 min). Thematic analysis using principles of constant comparison. |

n=24 Self-reported persistent symptoms following acute COVID-19 illness. Age range 20–68 years; 87.5% white British; 79.2% female. |

Four key themes reported in results: ‘Hard and heavy work’ of enduring and managing symptoms, trying to find answers, and accessing care. Living with uncertainty and fear. Importance of finding the 'right' GP. Recovery and rehabilitation: what would help? |

| Ladds et al (UK)18 |

Participants recruited from UK-based long COVID patient support groups, social media and snowball sampling. Individual narrative interview (telephone or video) or participation in an online focus group. Constant comparison method of data analysis. |

Total n=114 55 interviews (73% female), median age 48 (range 31–68) years; 59 focus group participants (68% female), median age 43 (range 27–73) years. |

Five key themes reported in results: The illness experience. Accessing care. Relationships (or lack of) with clinicians. Emotional touchpoints in encounters with health services. Ideas for improving services. |

| Maxwell (UK)1 |

Focus group of COVID-19 Facebook group members. | Not reported. | Four key themes reported in results: Expectation. Symptom journey. Being doubted. Support. |

GP, general practitioner.

Methodological quality

Studies were of variable methodological quality. Three met most of the criteria on the CASP checklist (table 2) and thus were considered of high quality, and two met fewer criteria. No studies were excluded on the basis of quality as all were considered to offer valuable content despite the limitations identified.

Table 2.

CASP critical appraisal of using the checklist for qualitative studies

| Assaf et al19 | Kingstone et al17 | Ladds et al18 | Maxwell1 | Davis et al16 | |

| Clear aims statement | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Appropriate methodology | U | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Appropriate research design | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Appropriate recruitment | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Appropriate data collection | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Researcher-participant relationship considered | N | U | U | U | U |

| Ethical issues considered | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Rigorous data analysis | U | Y | Y | N | U |

| Clear statement of findings | U | Y | Y | Y | Y |

N, criterion not satisfied; U, unclear if criterion satisfied; Y, criterion satisfied.

All five studies recruited participants through social media and/or online support groups. While this is understandable given the need to quickly access participants for whom no established groups or organisations existed, this convenience sampling may have resulted in bias.20 People who are active on social media or online support groups are likely to differ from the general population (eg, younger age) and may be more vocal about their experiences. Three included studies acknowledged skewed sample characteristics including mainly white ethnicity, over-representation of women and a generally younger age group.16 18 19 Limited demographic information was provided on participants, particularly in Maxwell,1 making it difficult to determine which population groups may have been missed by these studies.

None of the studies discussed potential biases arising from the relationship between researchers and study participants. This is despite people with lived experience of long COVID symptoms being among the study authors, or performing data analysis in some studies.16 17 19 This participatory research approach can be considered to represent both a strength and a weakness. Having authors and researchers with experience of long COVID analyse data is beneficial in bringing lived experience to the interpretation of data. However, it may also introduce bias for the same reason.

Several other quality issues were noted. In the study by Kingstone et al,17 participants received a compensation voucher for their time, which may have influenced decisions on whether to participate. Ladds et al18 only fully transcribed the first 10 out of the 55 interviews (the remaining interviews were partially transcribed). This was due to the urgency of the work and limited resources plus a perceived lack of need to duplicate previously discovered themes. This may have introduced bias. Finally, Maxwell1 reported very limited methodological details, making it difficult to determine how the research was conducted or the number of people involved in the focus group.

Review findings

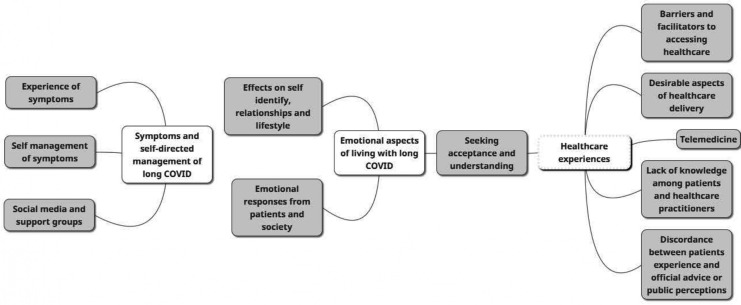

The initial stages of thematic analysis resulted in the generation of 138 descriptive themes. These were then refined into 54 subthemes, which were attributed to 11 higher order themes using an iterative process, with continuous discussion between reviewers. Further review and refinement of themes resulted in three overarching analytical themes: (1) symptoms and self-directed management of long COVID; (2) emotional aspects of living with long COVID; and (3) healthcare experiences associated with long COVID. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the final three themes and the initial 11 higher order themes. Full details of descriptive themes and subthemes are available in online supplemental file 3.

Figure 2.

Map of analytical and descriptive themes from the analysis.

Symptoms and self-directed management of long COVID

Evidence from all the included studies1 16–19 showed that people with long COVID experience a wider range of symptoms than the three symptoms officially recognised as acute COVID-19: high temperature, new continuous cough and change or loss of sense of smell or taste. One individual stated:

From week four I started to get chest pains and then breathlessness, gradually other symptoms developed including dry mouth, sore tongue, joint pains, fatigue, rash and tachycardia.1

The symptoms experienced by patients with long COVID varied in severity from relatively mild to potentially life-threatening symptoms that required hospital admission.16–19 Symptoms also fluctuated over time with new symptoms appearing at different stages of the illness and in different parts of the body.1 17–19 Each symptom was experienced for a prolonged but variable length of time, with a cumulative effect in many cases.1 16 18

People identified a disconnect between their lived experiences, official advice and public perception of the illness. It was felt that the public perceived the illness as a binary condition1 17—either mild and easily treated at home or serious and requiring hospitalisation—with no variation or allowances made for ongoing symptoms.

So, COVID-19, it’s either a mild infection or you die? No. But no one is prepared to think about us.17

The literature showed that people believed they would require a short recovery period and would be back at work in 2 weeks, a belief mirrored by employers and the public.1 16–19 The lived experience, for some, was quite different:

After nearly 6 months I have started to feel some improvement, although doing anything remotely physical results in a flare up of symptoms…1

I had to take two weeks off, had to work from home for four, but had to return for two weeks with fever as my employer would not give me more time […].16

This discordance between expectations and experience seemed to have a direct effect on the mental and emotional state of those experiencing prolonged illness,1 18 19 often leading to uncertainty about what to do about their symptoms.1 17 18 People described needing to adjust their lifestyle, including pacing themselves and setting realistic goals, in order to self-manage their symptoms.1 17 18 One study highlighted specific methods used by a number of patients attempting to self-care, such as taking supplements or trying therapeutic massage.17

Many people turned to social media and support groups (online or face to face) for support and found them to be a valuable way to share experiences, knowledge and resources with others in a similar situation.17–19 This communication helped to validate patient experiences and provided reassurance they were not alone in their struggle with long-term symptoms.

At least I know I'm not alone. And I think people who actually have had the disease tend to know a little bit more about it… I actually think that the support group has given more knowledge than the doctors have.18

However, there were also reports of stigma, anxiety and depression17 19 triggered by knowledge garnered from these online groups.

… Internet support groups, yeah on the Facebook groups that I'm on, I mean to be honest, I try not to read that group too much because it depresses me, makes me a bit anxious.17

Emotional aspects of living with long COVID

For many patients, there was a feeling that their self-identity was affected by long COVID. People reported an impact on how they viewed themselves, before and after their illness.16 18 There was a feeling they had to reconsider who they were and what they could do within the context of family and work.16–18 The phrase ‘compared with how I used to be’ was used by multiple participants in Kingstone et al’s study,17 while Ladds et al18 commented on the concept of a ‘spoiled identity’ where an identity as previously ‘healthy, independent and successful’ was perceived to be threatened.

Interviews by Ladds et al18 with doctors and other clinicians who had experienced long COVID showed that many were worried about the impact of cognitive deficits on their ability to perform their jobs.

[T]he medicolegal aspect is huge… and it’s scary to not be able to recognise potentially where you have deficits because if you can’t recognise them then that’s an unknown unknown in what can you do with that.18

There was a sense of stigma associated with long COVID, with people experiencing a sense of shame and blame (internally generated stigma) and expressing fears that employers and others in the community may stigmatise them for having long COVID (externally generated stigma).1 18 19 Family members were considered to be affected by long COVID and were seen as also requiring support.1 17 One interview participant described the impact her symptoms had on her family and how she felt they did not believe her:

I think, at first, they just thought, ‘Oh, for god’s sake, she’s napping again’. I feel like I constantly have to explain. I’m just exhausted and I just want to know why I’m so exhausted …17

Patients described experiencing a range of emotions as part of their illness journey.1 16–18 Anxiety was often related to multiple aspects of the illness including uncertainty about the cause of symptoms, concern that they may never recover completely and anxiety due to not being believed by healthcare professionals, family and friends.

… I was really frightened, terrified and just thought I might die on a couple of occasions … maybe not ‘I’m going to die right now’, but definitely ‘I’m never going to get better from this’ kind of feeling.17

Patients also expressed a strong desire to find acceptance and understanding about their experiences of long COVID, both among healthcare professionals and family and friends.

… one of my friends did say after quite a while, ‘I’m not being awful, but do you think a lot of it’s in his mind?’ and I said ‘no’. I was quite upset about that…17

Similarly, there was a widespread perception that healthcare professionals doubted patients’ descriptions of long COVID,1 ignored patient concerns,17 misdiagnosed symptoms19 or were dismissive of patient experiences.19 This lack of knowledge affected people’s feelings around their healthcare experiences.17

Healthcare experiences

Across most of the studies, participants expressed concerns relating to the lack of knowledge, information and understanding about long COVID among healthcare professionals.1 17–19 While the reason behind this lack of knowledge was understood, there was a general feeling that there needed to be acknowledgement of this gap within the healthcare community.

Well yeah, I feel like there’s a lack of knowledge. And I really wasn’t able to get any answers, I know, you know this is obviously a novel illness. But just even for one doctor to look into it a bit and come back to me, didn’t happen.17

The absence of knowledge and information about long COVID symptoms was reported to create anxiety and confusion for patients.1 17–19 Ladds et al18 found that this confusion was intensified by the lack of medical knowledge, understanding and guidance from healthcare professionals. There were also reports of conflicting or inconsistent advice from health professionals.18

Some professionals did recognise the limitations of their own knowledge17 18 and referred patients to online support groups. Focus group participants suggested they would rather be told that the professional did not have the knowledge required to address their illness, if that was the case.17 The importance of finding a general practitioner (GP) who was understanding, empathetic and who provided support to those experiencing long COVID is highlighted in this quote:

I have to say it was a really powerful experience speaking to the GPs … the two more recent ones, actually just the experience of being heard and feeling like somebody got it and was being kind about it, but you know it was okay that they couldn’t do anything, I just kind of needed to know that I wasn’t losing it really and it was real what I was experiencing, I think so that was really helpful.17

Along with this perceived lack of knowledge, multiple perceived barriers to healthcare access were reported1 17 18, along with a perception among participants that health services and doctors were too busy dealing with cases of acute COVID-19 to have capacity to deal with anything else, including patients with long-term symptoms.1 18 This perception appeared strengthened by the difficulties people experienced when trying to access primary care, especially if they were seeking a face-to-face consultation.

I think the message to avoid hospital and the GP unless you had specific symptoms was very unhelpful, particularly as I didn’t have, and never have had, a cough or fever.1

In general, study participants found accessing care to be ‘complex, difficult and exhausting’.18 This led to patients describing how they felt they had to manipulate the inflexible algorithm-driven systems in order to receive care, which led to feelings of guilt and anger.18 Some patients described creative solutions they had come up with to help them access healthcare, while others reported resorting to private healthcare to access tests.18 Many patients felt they needed to conduct their own research and construct their own care pathways, taking the lead in arranging consultations with specialists and circumventing bottlenecks in the system.18 This was reported as a route often employed by medical professionals who themselves were suffering from long COVID.18

There was also a perceived lack of support within the system.1 17 18 Some individuals described how NHS111 (a national telehealth helpline in the UK) had directed them to their GP who then directed them back to NHS111.18 There was what appeared to be a lack of guidance for those who did not need to be admitted to hospital but were no longer in the acute phase of the illness.1 18 19

Patients who felt they had received satisfactory care and access to healthcare were generally those who had been offered follow-up appointments and who felt their healthcare providers listened to them and gave them ongoing support, even if that was in the form of a video or telephone call.17–19

Telemedicine was widely used to facilitate interactions with healthcare services.1 17–19 However, it was generally perceived by patients to have limitations.1 17 Remote consulting with primary care was viewed by some patients as potentially limiting direct access to GPs, disrupting continuity of care (people often could not see the same GP every time) and making the communication of symptoms more challenging.1 17 18 Some patients felt that strict adherence to protocols for telemedicine-delivered care affected patient safety or led to mismanagement of their care.

… I remembered ringing my GP from the floor on my lounge laying on my front and kind of saying I’m really short of breath, you know, do you think I should try an inhaler do I need to go back to A&E and I was kind of told well you don’t really sound too out of breath over the phone… I really felt at that point right if you could see me you would see that I am really like broken.18

A positive view expressed in relation to telemedicine was that it increased accessibility of primary care during periods of societal restrictions aimed at controlling the spread of COVID-19.

My doctor was available via messaging, telephone, and telemedicine. She also contracted COVID-19 so she shared her experience with recovery and it helped me stay calm that I was on the right track.19

When asked to describe desirable features of healthcare services or service delivery for patients with long COVID, research participants asked for face-to-face assessments1 17 and talked about the need for ‘one-stop clinics’ with multidisciplinary teams who could look at their wide-ranging symptoms and treat them holistically.1 17 18 A case manager to oversee individual patients and ensure that all aspects of their care was considered was suggested, along with meaningful referral pathways and criteria.1

What would be most helpful is if all main hospitals could have a COVID clinic that had experts from respiratory, cardiology, rheumatology, neurology, physiotherapy etc, so you could go along for half a day and see people from these different departments, they can refer you for tests and you can get a plan in place, we are having such a range of symptoms that GPs are struggling to know what to do with you.1

Other participants spoke about wanting to be listened to, to be believed and understood and to be offered practical advice on coping.1

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first synthesis of findings from qualitative studies on peoples’ experiences of living with long COVID and accessing healthcare services for this condition. Our main findings were threefold. First, that the lived experience of long COVID is highly variable and perceived as being at odds with public perceptions and official guidance on COVID-19. Second, that there are significant emotional consequences of living with long COVID that need to be understood by a number of stakeholders. Finally, that people with long COVID report a range of positive and negative healthcare experiences that can be used to inform the development of new, or adaptation of existing, services for this important patient group.

COVID-19 is a new illness, first declared a public health emergency by the WHO on 30 January 2020.21 The implications across the globe and stress on healthcare services are unprecedented. It is perhaps unsurprising that knowledge of long COVID is perceived as underdeveloped; there is no agreed definition of long COVID, and the long-term sequelae are to a large extent unknown.3 Many people in the included studies turned to social media and patient-led support groups, due to perceived lack of understanding from family, employers and healthcare professionals.1 17–19 Social media and support groups are widely used for other health conditions22 but are generally considered complementary to healthcare services; part of the ‘jigsaw’ that makes supported self-management successful.23 Therefore, there appears to be a need for more widespread understanding of and information about long COVID, and people with lived experience are ideally placed to contribute their expert opinion.

Our review highlighted a number of emotional consequences of long COVID including the impact on people’s identities, employment and relationships with family and healthcare providers. Emerging models and recommendations for managing long COVID all highlight the need for psychological inputs.24–26 It is perhaps more complex to address the wider emotional consequences highlighted by this review; however, understanding and information as described previously and targeted at various levels (eg, healthcare professionals, patients, public and employers) appears to be indicated.

In addition to lack of knowledge, the review found a number of barriers to accessing healthcare, with reports of unhelpful messaging and complex processes to navigate. Healthcare professionals with long COVID were more able to navigate this complex system than non-professionals, suggesting a potential inequality. Telemedicine, rapidly rolled-out in many countries as a way of maintaining healthcare during the pandemic,27 was not always seen as beneficial. As new models for managing long COVID emerge, these findings may be useful for ensuring that services are patient centred.28 The finding that patients want multidisciplinary, holistic services is congruent with the well-documented multiorgan nature of COVID-19 and heterogeneous nature of long COVID symptoms.3

Strengths and limitations

Our review has highlighted a range of important issues associated with long COVID and accessing healthcare, from the perspective of people with this condition. The review is limited by the small number of qualitative studies (n=5) that have been published to date and will benefit from being updated as further research becomes available in this fast-moving field. Nonetheless, it contributes to an early understanding of the lived experience of long COVID and of accessing healthcare services. The majority of studies were conducted in the UK, there was over-representation of younger and female, white, participants and all studies recruited participants via social media or online support groups. Therefore, the findings apply to this population, and it is possible that other groups of people with long COVID have different experiences and views. Some emerging evidence suggests that long COVID may be more prevalent in younger female individuals29; a meta-analysis in preprint form however reports a linear increase in long COVID from age 20–70 years.30 We limited our search to studies published in English; therefore, it is possible that we missed studies published in other languages. We did not exclude studies on methodological quality, resulting in the inclusion of one study with limited methodological details resulting in a low CASP score. However, the validity of appraisal of qualitative research is debated in the literature,31 and we are confident that all studies contributed valuable data on the lived experience of long COVID. We did not formally calculate agreement between pairs of reviewers at data extraction, critical appraisal or data synthesis stages. However, given the small number of included studies, and frequent communication within the review team, there were very few instances of disagreement, all of which were resolved by discussion. We did not contact authors for additional information that may have allowed us to more fully appraise methodological quality of the included studies. However, we did not exclude any studies based on methodological quality; therefore, the review findings were not affected.

Implications for practice

There is a need for greater understanding and communication about long COVID at a number of levels (public, policy and healthcare professional). Our findings suggest that people with long COVID are well placed to cocreate this understanding and communication. Our findings can also be used by those currently developing services for people with long COVID to ensure that they meet patients’ needs. The varied and fluctuating symptoms and emotional consequences experienced by people with long COVID indicate a need for multidisciplinary services, which provide holistic patient-centred assessment, appropriate management and specialist referral where indicated.

Implications for research

Further qualitative research on more culturally diverse samples of people with long COVID is indicated to help understand the impact of long COVID and the healthcare needs of the wider population than is represented by the current review. As models of care and services are developed/adapted for people with long COVID, it is vital that the views and experiences of people with long COVID continue to be explored.

Conclusion

We have presented a synthesis of the current qualitative evidence on the experience of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services. People experience long COVID as a heterogeneous condition, with a variety of physical and emotional consequences. It appears that greater knowledge of long COVID is required by a number of stakeholders and that the design of emerging long COVID services or adaptation of existing services for patients with long COVID should take account of patients’ experiences in their design.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it was published online. The corresponding author has been changed to Moray Nairn.

Contributors: DM, JH, KC, KM and MN developed the protocol. CM conducted the literature searches. JH and DM screened articles for inclusion. KM, DM, JH and MN extracted data, appraised studies and, including KC, were involved with synthesising the qualitative data, interpreting the findings and writing the first draft of the manuscript. Other members of the research teams within Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, and Healthcare Improvement Scotland provided peer review comments on the draft manuscript. KM is the guarantor for this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Search strategies for databases other than Medline are available by contacting the corresponding author. Full data extraction tables are also available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Maxwell D. Living with COVID19: a dynamic review of the evidence around ongoing Covid19 symptoms (often called Long Covid), 2020. Available: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/themedreview/living-with-covid19/ [Accessed 02 Nov 2020].

- 2.Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made long Covid. Soc Sci Med 2021;268:113426. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins V, Sohaei D, Diamandis EP, et al. COVID-19: from an acute to chronic disease? potential long-term health consequences. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2021;58:297–310. 10.1080/10408363.2020.1860895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020;13:m3026. 10.1136/bmj.m3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 [Accessed 2 Feb 2021]. [PubMed]

- 6.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) . Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/managing-the-long-term-effects-of-covid-19/ [Accessed 2 Feb 2021].

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA) . Morbidity and mortality weekly report: symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network — United States, March–June 2020, 2020. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6930e1.htm [Accessed 2 Feb 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [Accessed 2 Feb 2021].

- 9.NHS England . NHS to offer 'long covid' sufferers help at specialist centres, 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/10/nhs-to-offer-long-covid-help/ [Accessed 2 Feb 2021].

- 10.Gutenbrunner C, Stokes EK, Dreinhöfer K, et al. Why rehabilitation must have priority during and after the COVID-19-pandemic: a position statement of the global rehabilitation alliance. J Rehabil Med 2020;52:jrm00081. 10.2340/16501977-2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeJean D, Giacomini M, Simeonov D, et al. Finding qualitative research evidence for health technology assessment. Qual Health Res 2016;26:1307–17. 10.1177/1049732316644429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selva A, Solà I, Zhang Y, et al. Development and use of a content search strategy for retrieving studies on patients’ views and preferences. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:126. 10.1186/s12955-017-0698-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients’ knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc 2016;104:320–4. 10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingstone T, Taylor AK, O'Donnell CA, et al. Finding the 'right' GP: a qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID. BJGP Open 2020;4:bjgpopen20X101143. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladds E, Rushforth A, Wieringa S, et al. Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: qualitative study of 114 "long Covid" patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:1144. 10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patient Led Research . Report: what does COVID-19 recovery actually look like? an analysis of the prolonged COVID-19 symptoms survey by Patient-Led research team, 2020. Available: https://patientresearchcovid19.com/research/report-1/ [Accessed 27 Oct 2020].

- 20.Blank G, Lutz C. Representativeness of social media in Great Britain: investigating Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+, and Instagram. American Behavioral Scientist 2017;61:741–56. 10.1177/0002764217717559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization (WHO) . COVID-19 public health emergency of international concern: global research and innovation forum - towards a research roadmap, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum [Accessed 16 Feb 2021].

- 22.Myneni S, Lewis B, Singh T, Paiva K, et al. Diabetes self-management in the age of social media: large-scale analysis of peer interactions using semiautomated methods. JMIR Med Inform 2020;8:e18441. 10.2196/18441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson N, Ozakinci G. “It all needs to be a full jigsaw, not just bits”: exploration of healthcare professionals’ beliefs towards supported self-management for long-term conditions. BMC Psychol 2019;7:38. 10.1186/s40359-019-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ladds ERA, Wieringa S, Taylor S. Developing services for long COVID: lessons from a study of wounded healers. Clin Med J 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barker-Davies RM, O'Sullivan O, Senaratne KPP, Baker P, et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:949–59. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sivan M, Halpin S, Hollingworth L, Snook N, et al. Development of an integrated rehabilitation pathway for individuals recovering from COVID-19 in the community. J Rehabil Med 2020;52:jrm00089. 10.2340/16501977-2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas EE, Haydon HM, Mehrotra A, Snoswell L, et al. Building on the momentum: sustaining telehealth beyond COVID-19. J Telemed Telecare 2020:1357633X2096063. 10.1177/1357633X20960638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, Naldemirci O, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scand J Caring Sci 2017;31:662–73. 10.1111/scs.12376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NIHR . Living with COVID-19 – second review, 2021. Available: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/themedreview/living-with-covid19-second-review/ [Accessed 08 Jul 2021].

- 30.Thompson EJ, Williams DM, Walker AJ. Risk factors for long COVID: analyses of 10 longitudinal studies and electronic health records in the UK [Preprint]. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majid U, Vanstone M. Appraising qualitative research for evidence syntheses: a compendium of quality appraisal tools. Qual Health Res 2018;28:2115–31. 10.1177/1049732318785358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050979supp001.pdf (348.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Search strategies for databases other than Medline are available by contacting the corresponding author. Full data extraction tables are also available.