Abstract

Background

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A) is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that may occur during or in the weeks following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. To date, only case reports and small case series have described typical findings and management of patients with MIS-A. The prevalence of MIS-A is largely unknown due to the lack of data.

Case summary

A 30-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with new-onset of fever, chest discomfort, macular exanthema, abdominal pain, mild dyspnoea, and coughing. The patient reported a mildly symptomatic recent coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Significantly increased markers of inflammation and a modest increase of cardiac troponin were found upon laboratory work-up at admission. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotics, the patient’s clinical status deteriorated continuously. Cardiac work-up, including echocardiography, coronary angiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, was done and signs of acute myocarditis with mildly reduced left ventricular systolic function were found. The complex multi-organ symptom constellation facilitated the diagnosis of MIS-A following COVID-19 infection. Besides aspirin, intravenous, continuous hydrocortisone treatment was initiated, resulting in a prompt improvement of symptoms and clinical findings.

Discussion

We report a case of successfully treated MIS-A in the context of COVID-19, which further adds to the existing literature on this rare but clinically significant condition. Our case highlights the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach to correctly diagnose this complex, multi-organ disease and enable fast and appropriate management of these high-risk patients.

Keywords: Case report, Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults, MIS-A, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2

Learning points

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults is a rare complication following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection and should be considered in patients presenting with typical symptoms, such as fever, cardiac and gastrointestinal symptoms, dermatological manifestations with only mild respiratory symptoms.

Our case highlights the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach to correctly diagnose this complex, multi-organ disease and enable appropriate early management of these high-risk patients.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) originated in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019 and has since spread rapidly across the globe causing an international pandemic. In April 2020, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) was described as a rare complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in the UK.1 The prevalence of MIS-C has been estimated at 2/100 000 children in communities experiencing widespread COVID-19 infection.2 To date, only case reports and small case series attest to the even rarer manifestation of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A). Clinical presentation varies from case to case, but typically includes fever, cardiac and gastrointestinal symptoms, dermatological manifestations, and only mild respiratory symptoms.3

Timeline

| Timeline | Events |

|---|---|

| 4 weeks prior |

|

| Day 1 |

|

| Days 1–3 |

|

| Day 4 |

|

| Days 4–11 |

|

| Day 24 |

|

| Day 53 |

|

Case presentation

A 30-year-old, ill-appearing South Asian male patient presented to the emergency department with new-onset fever, chest discomfort, macular exanthema, abdominal pain, coughing, mild dyspnoea, and tachypnoea for a couple of days. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable except for a recent infection with SARS-CoV-2 about a month prior to the current presentation. There was no history of smoking or a family history of cardiovascular disease and the patient had a mildly increased body mass index of 29. The course of the COVID-19 disease was mild with only minor symptoms of respiratory infection, most notably coughing, did not require further medical attention, and the patient recovered completely without any residual symptoms. The patient had not been vaccinated prior to COVID-19 infection or since then. Upon admission to the emergency department, the patient tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids in consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs. Antibody-testing for SARS-CoV-2 was positive with 164 U/mL, confirming past COVID-19 infection.

On examination, a widespread, itching, non-scaling macular exanthema was evident, which originated at the lower legs and had since spread to the trunk. Additionally, mild abdominal tenderness was localized in the epigastric area and pulmonary auscultation revealed bilateral fine rales in the lung bases. Upon cardiac auscultation, no murmurs or pathological heart sounds were evident and peripheral volume status appeared euvolaemic. The further physical exam was unremarkable and vital signs were initially stable. Laboratory work-up showed significant inflammation [white blood cells 11.7 G/L and c-reactive protein (CRP) 155 mg/L] and a mild increase of markers of myocyte necrosis and myocardial stretch [high-sensitive cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) 84 ng/L and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) 476 ng/L] (Figure 1). Upon chest X-ray, bilateral diffuse reticular abnormalities were described in both lungs (Figure 2). The patient was started on i.v. broad-spectrum, empiric antibiotics after blood cultures were drawn (ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. and azithromycin 500 mg p.o.) and was subsequently admitted to the department of pulmonary medicine. High-resolution chest computed tomography (CT), which was issued to further characterize the X-ray findings, showed mild bilateral, multilobular interstitial abnormalities, and ground-glass opacities most notably in the basal sections of the lung (Figure 2). These findings were compatible with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and there were no signs of acute bacterial pneumonia or severe respiratory disease.

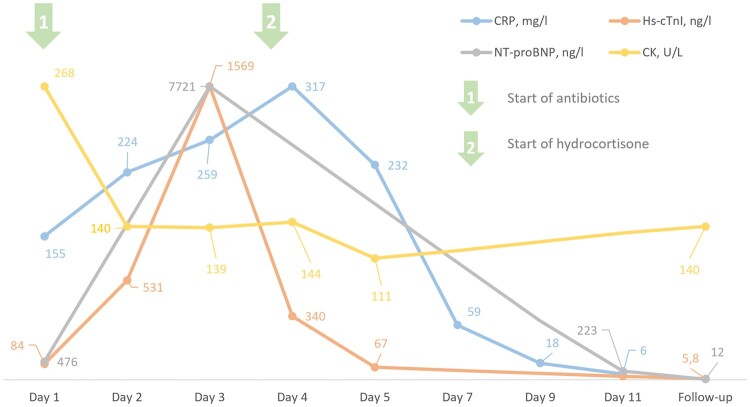

Figure 1.

Linear changes of inflammatory and cardiovascular biomarkers in our patient over the course of his illness.

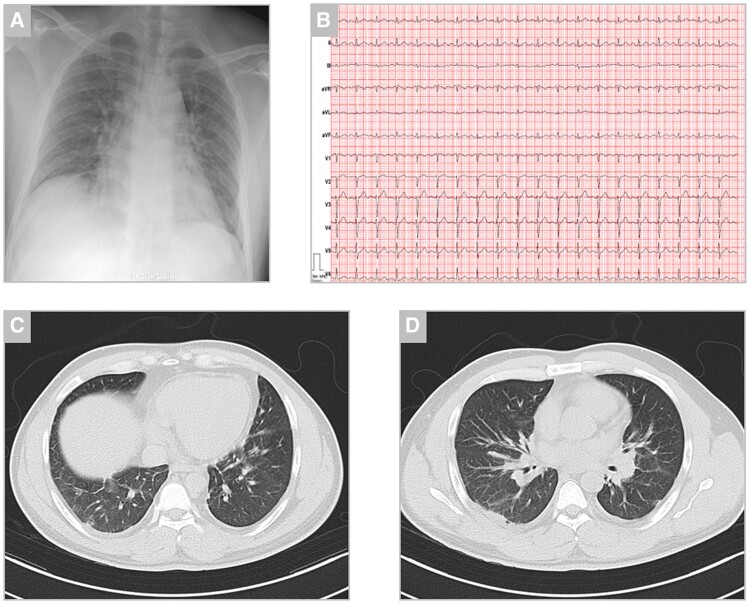

Figure 2.

Chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, and chest computed tomography on the day of admission. (A) Chest X-ray showed bilateral diffuse reticular opacities with a regular dimensioned heart silhouette. (B) Twelve-lead electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia at a rate of 120 beats per minute and peripheral low voltage. (C and D) Chest computed tomography scans showed bilateral multilobular interstitial abnormalities and mild ground-glass opacities.

Upon laboratory follow-up, a significant increase of both hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP was noted. The electrocardiogram was unremarkable except for sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute and peripheral low voltage. Transthoracic echocardiography showed mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 49% without evidence of regional wall motion abnormalities (Figure 3, Supplementary videos 1–4). Since the patient continued to suffer from chest discomfort referral for acute coronary angiography was issued, which excluded coronary artery disease. Ventriculography confirmed mildly reduced left ventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction of 43%. (Figure 4). The patient was then transferred to our cardiological ward for haemodynamic monitoring and further management. To confirm the current tentative diagnosis of acute myocarditis, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was arranged. Pulmonary embolism may also be considered as a potential differential diagnosis in this setting. However, since the pre-test probability for pulmonary embolism was low (Wells Score of 1.5), echocardiography showed normal right ventricular function nor any other signs of pulmonary embolism and a different diagnosis was considered more likely, a second CT scan was omitted to reduce radiation exposure in this young patient.

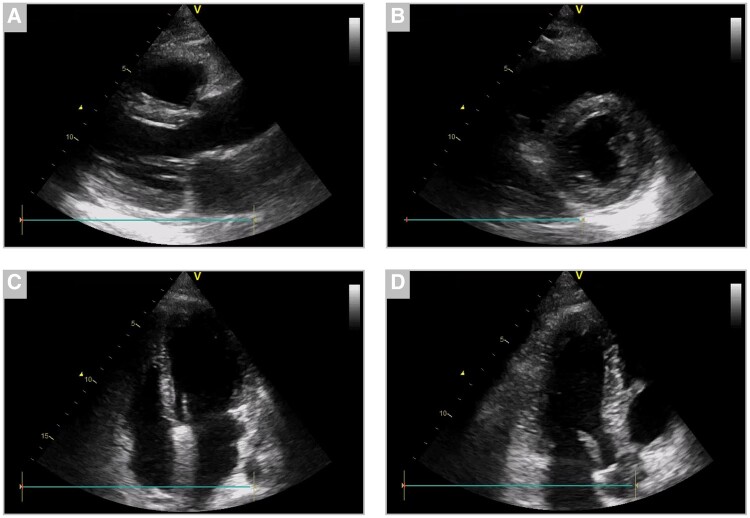

Figure 3.

Transthoracic echocardiography upon transfer to cardiac care showed mildly reduced left ventricular systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction of 49%) and normal right ventricular function during sinus tachycardia. (A) Parasternal long-axis, (B) parasternal short-axis, (C) four-chamber view, and (D) three-chamber view.

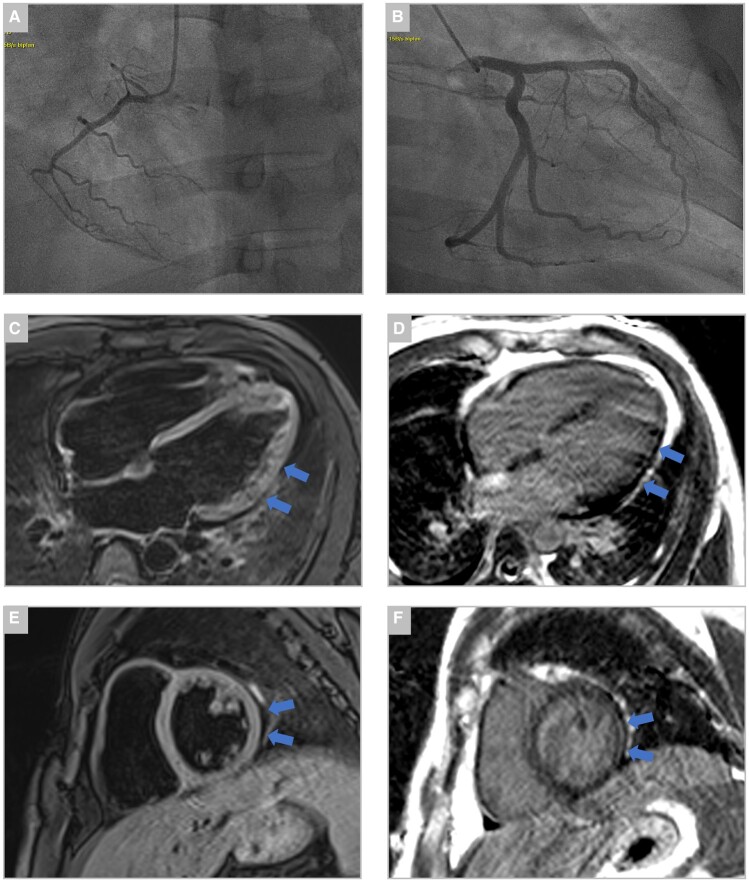

Figure 4.

Coronary angiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging during the index event. (A and B) Coronary angiography showed no visible coronary disease or luminal irregularities. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing (C) four-chamber view T2-weighted image with mildy hyperintense signal located in the lateral wall, indicative of myocardial oedema (blue arrows). (D) Four-chamber view 10-min post-gadolinium injection (late gadolinium enhancement) with patchy epicardial enhancement in the lateral wall (blue arrows). (E) Short-axis T2-weighted image with hyperintense signal located in the lateral wall (blue arrows). (F) Short-axis 10-min post-gadolinium injection (late gadolinium enhancement) with patchy epicardial enhancement in the lateral wall (blue arrows).

During the next couple of days, despite continuous antibiotic treatment, symptoms did not improve and clinical findings further deteriorated: heart rate further rose and blood pressure dropped to 90/60 mmHg. In addition to the aforementioned symptoms, we found bilateral redness of the eyes, consistent with conjunctivitis and a generalized arthralgia. Autoimmune diagnostics returned negative and we did not find any signs of acute human parvovirus B-19 infection, mononucleosis, streptococcal infection, influenza, or rubella upon diagnostic work-up, which have to be considered as potential differential diagnoses in this case. The complex, multi-organ symptom constellation with a failure of clinical improvement despite broad-spectrum antibiotics facilitated the diagnosis of MIS-A following recent mildly symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. According to current literature, the patient was started on a 100 mg daily dose of aspirin and an intravenous hydrocortisone drip with 200 mg/day after an initial bolus of 100 mg. The patient’s symptoms and haemodynamic parameters improved drastically following the start of steroid treatment. We also observed a prompt and steady decrease of inflammatory markers and the last fever spike of 39°C was documented on the day of steroid initiation. Cardiac MRI finally confirmed acute myocarditis with findings of myocardial oedema, late gadolinium enhancement and small pericardial effusion—at this point, in time the patient was already feeling better and only suffered from intermittent and mild chest pain (Figure 4).

After 6 days of intravenous corticosteroid treatment—stopped without tapering—the patient was discharged from hospital care without significant residual symptoms. The necessity of strict, physical activity restriction for 3–6 months was discussed with the patient. There were no adverse or unanticipated events secondary to corticosteroid treatment. Upon 2-week follow-up, the patient was feeling well and there was no symptom recurrence. Echocardiography at 6-week follow-up revealed a normalization of systolic left ventricular function alongside a normalization of laboratory markers of myocardial injury. Antithrombotic treatment with aspirin was also stopped at this point.

Discussion

Multi-inflammatory syndrome in children—also known as paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (PIMS-TS)—was first recognised in the UK in April 2020. Since then several reports have confirmed MIS-C as a rare, but significant, complication in children with a history of or exposure to COVID-19. Recently, case reports and small case series of MIS-A have been published, that outlined the clinical presentation and disease course of these patients.3 While the clinical plethora of symptoms is similar to the ones observed in children, the prevalence of the disease is unclear in adults and adolescents due to the lack of data. Typical symptoms include fever (body temperature ≥38°C for at least 24 h), cardiac symptoms (chest pain or palpitations), gastrointestinal symptoms, dermatological manifestations, and haemodynamic deterioration (low blood pressure), while only suffering from mild respiratory symptoms. Patients usually have evidence of cardiac involvement with electrocardiographic abnormalities, elevated troponin levels, or echocardiographic findings of reduced left or right ventricular function. While myocarditis is a hallmark of MIS-C/MIS-A presentation, the pathophysiological mechanism behind has not been fully elucidated yet. Direct viral effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, a systemic inflammatory response and endothelial proteins, such as endoglin, have been discussed as potential pathophysiological triggers of myocarditis in these patients.4 Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults is also accompanied by a significant inflammatory response, evidenced by a substantial increase of inflammatory markers, such as CRP or ferritin and also by elevated coagulopathy markers, such as D-Dimer.3,5–7

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has proposed a working case definition to facilitate diagnosis of patients with MIS-A (Table 1). Similarly, a diagnostic algorithm has been suggested by Vogel et al., which quantifies the clinical likelihood of MIS-A diagnosis. Our case met all diagnostic criteria of the CDC case definition and scored level 1 of diagnostic certainty in the algorithm by Vogel etal. Early diagnosis of MIS-A is essential to improve outcome for affected patients, who are at high risk of deterioration to critical illness and mortality. A case series including 16 patients with MIS-A has reported a necessity of intensive care treatment in 10 patients with 2 subsequent fatal outcomes.3,5

Table 1.

Working MIS-A case definition by CDC3

| Working MIS-A case definition by CDC |

|---|

| Age ≥21 years AND |

| Severe illness requiring hospitalization AND |

| Current or previous (within 12 weeks) SARS-CoV-2 infection AND |

| Severe dysfunction of one or more extrapulmonary organ systems AND |

| Laboratory evidence of severe inflammation AND |

| Absence of severe respiratory illness |

Adequate management of patients with MIS-A requires a multidisciplinary approach to ensure optimal, individualized treatment. Besides haemodynamic support and symptomatic treatment, early administration of intravenous high-dose corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulins have been suggested as first-line treatment options.8 Additionally, short-term treatment with low-dose aspirin has been recommended for patients with MIS-C since the disease has been linked to Kawasaki disease, which is associated with platelet activation, thrombocytosis, and endothelial damage. Decision for antithrombotic treatment should be balanced with the individual bleeding risk of each patient.8 While these recommendations are only based on case reports and case series and have not been tested in clinical studies, this is the only evidence available at this time.3,9 Our case report highlights the appropriate work-up for cardiovascular involvement patients with MIS-A and further adds insight to the practical management of these patients. Additionally, one has to keep in mind, which the prevalence of MIS-A is probably vastly underestimated due to the lack of public knowledge and the difficulty to distinguish MIS-A from a severe COVID-19 disease course. Thorough clinical examination and history taking is required to facilitate early diagnosis of MIS-A and allow subsequent adequate medical care.

Lead author biography

Christoph C. Kaufmann studied medicine at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria and is currently enrolled in a PhD programme at the same institution. At present, he is a third-year cardiology resident at the Klinik Ottakring in Vienna. His clincal and research interest focus on cardiovascular biomarkers, heart failure, electrophysiology and COVID-19.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding

The research was supported by the Ludwig Boltzmann Cluster for Cardiovascular Research, Vienna, and the Association for the Promotion of Research in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology (ATVB), Vienna.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Paediatric Intensive Care Society. PICS statement: increased number of reported cases of novel presentation of multisystem inflammatory disease. 2020. https://pccsociety.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PICS-statement-re-novel-KD-C19-presentation-v2-27042020.pdf (5 May 2021).

- 2. Dufort EM, Koumans EH, Chow EJ, Rosenthal EM, Muse A, Rowlands J. et al. ; New York State and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Investigation Team. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morris SB, Schwartz NG, Patel P, Abbo L, Beauchamps L, Balan S. et al. Case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection—United Kingdom and United States, March-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1450–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Consiglio CR, Cotugno N, Sardh F, Pou C, Amodio D, Rodriguez L. et al. ; CACTUS Study Team. The immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Cell 2020;183:968–981.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogel TP, Top KA, Karatzios C, Hilmers DC, Tapia LI, Moceri P. et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults (MIS-C/A): case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 2021;39:3037–3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mieczkowska K, Zhu TH, Hoffman L, Blasiak RC, Shulman KJ, Birnbaum M. et al. Two adult cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAAD Case Rep 2021;10:113–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rieper K, Sturm A.. [First cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults in Germany]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2021;146:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, Gorelik M, Lapidus SK, Bassiri H. et al. American College of Rheumatology clinical guidance for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-CoV-2 and hyperinflammation in pediatric COVID-19: version 2. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:e13–e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MBF. et al. ; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2020;383:334–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.