Abstract

Background: Metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients have a poor prognosis with a 3-year survival rate of 25%. About 30% of them present lung metastases (LM). This study aimed to construct 2 nomograms to predict the risk of LM and overall survival of STS patients with LM. Materials and Methods: The data of patients were derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database during the period of 2010 to 2015. Logistic and Cox analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors and prognostic factors of STS patients with LM, respectively. Afterward, 2 nomograms were, respectively, established based on these factors. The performance of the developed nomogram was evaluated with receiver operating characteristic curves, area under the curve (AUC) calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA). Results: A total of 7643 patients with STS were included in this study. The independent predictors of LM in first-diagnosed STS patients were N stage, grade, histologic type, and tumor size. The independent prognostic factors for STS patients with LM were age, N stage, surgery, and chemotherapy. The AUCs of the diagnostic nomogram were 0.806 in the training set and 0.799 in the testing set. For the prognostic nomogram, the time-dependent AUC values of the training and testing set suggested a favorable performance and discrimination of the nomogram. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year AUC values were 0.698, 0.718, and 0.715 in the training set, and 0.669, 0.612, and 0717 in the testing set, respectively. Furthermore, for the 2 nomograms, calibration curves indicated satisfactory agreement between prediction and actual survival, and DCA indicated its clinical usefulness. Conclusion: In this study, grade, histology, N stage, and tumor size were identified as independent risk factors of LM in STS patients, age, chemotherapy surgery, and N stage were identified as independent prognostic factors of STS patients with LM, these developed nomograms may be an effective tool for accurately predicting the risk and prognosis of newly diagnosed patients with LM.

Keywords: surgeries, soft tissue functionality, nomogram, Cox regression analysis, logistics regression analysis, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Introduction

Soft Tissue Sarcoma and Lung Metastasis

Soft tissue sarcoma (STS) are malignant soft-tissue tumors that comprise a variety of histological subtypes (such as liposarcomas, rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, leiomyosarcomas, and fibrosarcomas) and can arise in nearly any part of the body. 1 STS are predominantly located in the lower limbs, followed by the upper limbs and trunk. Further common locations include the head/neck region and retroperitoneal space. 2 Advanced STS often metastasizes through the bloodstream, lymphatic system, and intraperitoneal route, which is an important reason for poor prognosis in STS patients. 3 The lung is the most frequent organ of metastasis for STS, comprising 80% of the first site of metastasis from STS. 4 The risk of metastasis is largely driven by tumor grade; approximately 60% of patients with high-grade tumors will develop lung metastases (LM), with the vast majority occurring within 2 years of primary tumor resection. 5 The highest risk tumors are those that are >5 cm in size with an intermediate or high-grade histology. 6 The reported median life expectancy ranges from 10 to 12 months for STS patients suffering from LM.7,8 Considering this rapid progression of high-grade STSs prompt detection of LM may improve prognosis given therapeutic interventions currently available.

Therapeutic Strategies

The gold standard for patients with localized STSs is surgical-wide resection with oncologic margins.2,9 In contrast, STS patients with metastatic lesions are treated by systemic chemotherapy, radiation, and possibly with resection of the primary tumor or metastatic lesions.10,11 Doxorubicin, the first-line palliative chemotherapy, is recommended as a therapeutic option for the majority of STS patients with LM. 12 Pulmonary metastasectomy is also a proven standard approach for the management of STS patients with LM, and some published studies have indicated that 5-year overall survival (OS) ranges from 43% to 50.9% in patients following this procedure.13‐15 In addition, Matsuoka et al reported surgical resection of a primary tumor in the extremities could improve survival for metastatic STS patients. 16 Despite efforts to improve the clinical outcome of these patients, the prognosis remains poor. 17

Prognostic Assessment

Several published studies have assessed the LM-related risk factors and prognostic factors of STS patients with LM, including the number of LM, histology, stage, and location of primary disease and pulmonary metastasectomy.8,17,18 To date, however, there is a lack of standard predictive models to predict risk and prognosis for STS with LM for clinicians. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database is the largest publicly available dataset, which collects data from 18 cancer registries and involves approximately 30% of the US population. Therefore, using population-based data, the objective of this study was to develop 2 nomograms for predicting LM in patients newly diagnosed with STS and the survival rate of STS patients with LM.

Materials and Methods

Patient’ Population

The data of patients diagnosed with STS were downloaded from the SEER database utilizing SEER∗Stat software (Surveillance Research Programme, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software, www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat, version 8.3.6).

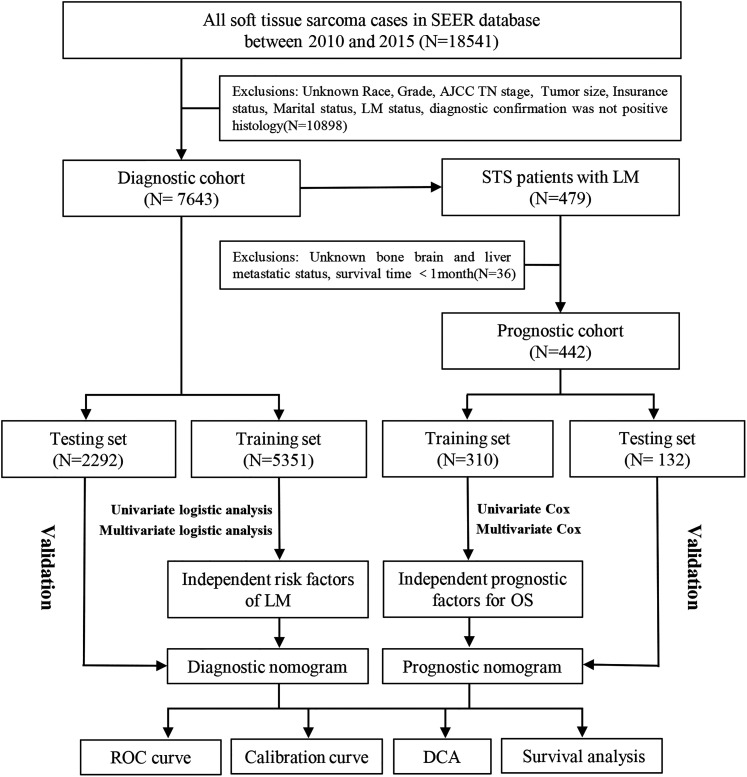

For the diagnostic cohort, the inclusion criteria were: (a) patients diagnosed with STS between 2010 and 2015 and (b) complete clinical data, including sex, race, age at diagnosis, tumor site, tumor size, histology, grade, T stage, N stage, marital, and insurance status. The exclusion criteria were (a) the diagnosis confirmation of the patient was not histology positive; (b) STS was not the first malignant tumor; and (c) patients diagnosed with autopsies or death certificates. In addition, STS patients with LM who had complete treatment information for surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, definitive information for bone metastasis, liver metastasis, and brain metastasis, and a survival time of ≥1 month formed another prognostic cohort. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of patient selection and the study flow.

Study Variables

Based on the accessible data recorded in the SEER database and published literature. Some appropriate variables were included for the present study. Eleven variables were extracted to identify the independent LM-related risk factors, including age, sex, race, histologic type, grade, tumor site, tumor size, T stage, N stage, marital status, and insurance status. In studying the independent prognostic factors for STS patients with LM, 6 other variables were also collected, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, specific metastasis information of bone metastasis, liver metastasis, and brain metastasis.

Those continuous variables were also transformed into categorical variables based on recognized cutoff values. (age: <55 years and ≥55 years and tumor size: <5 cm, 5-10 cm, and >10 cm).7,18,19

Institutional Review Board Approval

All anonymized data used in this study were obtained from the SEER database. The individual SEER ID (13899-Nov2020) was used to support our analysis. All procedures in this study involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Statistical Analysis

In the present study, statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc) and R version 3.6.1 (https://www.r-project.org/about.html, R Statistical Software, R Foundation for Statistical Computing).20,21 All enrolled patients were randomized into the training set and testing set in a ratio of approximately 7:3 using R software. Overall survival was determined as the primary endpoint for the section of prognostic analysis section in this study. The χ2 test is applied to test whether there was a significant difference in the baseline data between both sets.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to explore independent risk factors of LM in STS patients. In the prognostic analysis, the univariate and multivariate Cox analyses were performed to determine prognostic factors. Finally, based on the results of logistic analysis and Cox analysis, the diagnostic nomogram and prognostic nomogram were constructed by the “rms” package in R software, respectively. Validation of the models was carried out internally in the training set and externally in the testing set. Meanwhile, the predictive accuracy of the nomogram was appraised by discrimination and calibration evaluation. The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for diagnostic nomogram and 1-, 2-, and 3-year ROC curve for prognostic nomogram were plotted. And the ROC curves of the independent variables were also generated. Calibration curves and decision curve analysis (DCA) were conducted to evaluate the accuracy and clinical applicability of this model. 22

Furthermore, all STS patients with LM were assigned into the high-risk, intermediate-risk, and low-risk subgroup according to the tertile of total scores, and the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test was performed. The P value < .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Study Population Characteristics

In the present study, we extracted data from 7643 STS patients to form a study cohort to identify the independent risk factors for LM in STS patients and develop a diagnostic nomogram. These patients were randomly allocated to the training set (N = 5351, for development and internal validation of the nomogram) and testing set (N = 2292, for external validation of the nomogram) using R software. The baseline data between the 2 sets were comparable and are shown in Table 1. In addition, of the 7643 STS patients, 5.78% (N = 442) were confirmed to have LM at the time of primary diagnosis.

Table 1.

The Demographic and Clinicopathologic Information of Patients Newly Diagnosed With STS.

| Variables | Total set (N = 7643) |

Training set (N = 5351) |

Testing set (N = 2292) |

P value |

| Age(years) | .252 | |||

| <55 | 3239 (42.4%) | 2245 (42.0%) | 994 (43.4%) | |

| ≥55 | 4404 (57.6%) | 3106 (58.0%) | 1298 (56.6%) | |

| Race | .610 | |||

| Black | 831 (10.9%) | 571 (10.7%) | 260 (11.3%) | |

| Other a | 696 (9.1%) | 494 (9.2%) | 202 (8.8%) | |

| White | 6116 (80.0%) | 4286 (80.1%) | 1830 (79.8%) | |

| Sex | .386 | |||

| Female | 3312 (43.3%) | 2336 (43.7%) | 976 (42.6%) | |

| Male | 4331 (56.7%) | 3015 (56.3%) | 1316 (57.4%) | |

| Histologic type | .615 | |||

| Fibrosarcoma | 1276 (16.7%) | 882 (16.5%) | 394 (17.2%) | |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 149 (1.9%) | 105 (2.0%) | 44 (1.9%) | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 934 (12.2%) | 643 (12.0%) | 291 (12.7%) | |

| Liposarcoma | 1942 (25.4%) | 1390 (26.0%) | 552 (24.1%) | |

| MPNST | 269 (3.5%) | 196 (3.7%) | 73 (3.2%) | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 172 (2.3%) | 113 (2.1%) | 56 (2.4%) | |

| Synovial sarcoma | 389 (5.1%) | 270 (5.0%) | 119 (5.2%) | |

| Unclassified | 460 (6.0%) | 311 (5.8%) | 149 (6.5%) | |

| Other | 2052 (26.8%) | 1438 (26.9%) | 614 (26.8%) | |

| Grade | .583 | |||

| Grade I | 1488 (19.5%) | 1052 (19.7%) | 436 (19.0%) | |

| Grade II | 1470 (19.2) | 1020 (19.1%) | 450 (19.6%) | |

| Grade III | 19 333 (25.3%) | 1335 (24.9%) | 598 (26.1%) | |

| Grade IV | 2752 (36.0%) | 1944 (36.3%) | 808 (35.3%) | |

| Tumor site | .916 | |||

| Extremity | 4466 (58.4%) | 3127 (58.4%) | 1339 (58.4%) | |

| Head and neck | 429 (5.6%) | 304 (5.7%) | 125 (5.5%) | |

| Trunk | 2748 (36.0%) | 1920 (35.9%) | 828 (36.1%) | |

| T stage | .663 | |||

| T1 | 2251 (29.5%) | 1568 (29.3%) | 683 (29.8%) | |

| T2 | 5392 (70.5%) | 3783 (70.7%) | 1609 (70.2%) | |

| N Stage | .347 | |||

| N0 | 7315 (95.7%) | 5129 (95.9%) | 2186 (95.4%) | |

| N1 | 328 (4.3%) | 222 (4.1%) | 106 (4.6%) | |

| Tumor size | .103 | |||

| <5 cm | 2031 (26.6%) | 1407 (26.3%) | 624 (27.2%) | |

| 5 to 10 cm | 2646 (34.6%) | 1826 (34.1%) | 820 (35.8%) | |

| >10 cm | 2966 (38.8%) | 2118 (39.6%) | 848 (37.0%) | |

| Insurance status | .382 | |||

| Insured | 7384 (96.6%) | 5176 (96.7%) | 2208 (96.3%) | |

| Uninsured | 259 (3.4%) | 175 (3.3%) | 84 (3.7%) | |

| Marital status | .825 | |||

| Married | 4267 (55.8%) | 2983 (55.7%) | 1284 (56.0%) | |

| Unmarried | 3376 (44.2%) | 2368 (44.3%) | 1008 (44.0%) | |

Abbreviations: MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; STS, soft tissue sarcoma.

American Indian, Native Alaskan and Asian, Pacific Islander.

Risk Factors for LM in STS Patients and Diagnostic Nomogram

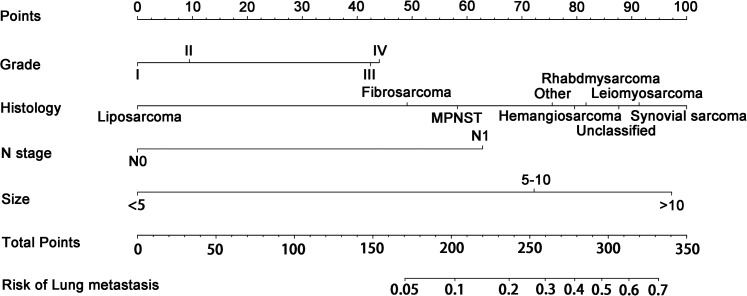

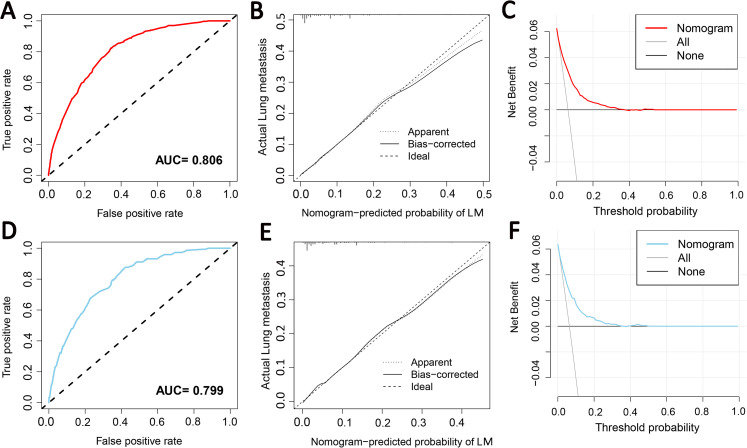

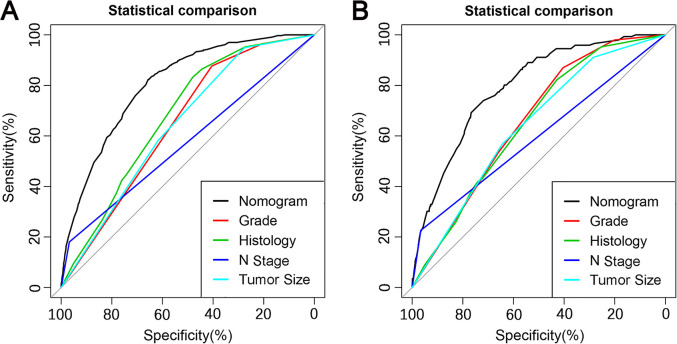

Grade, histologic type, N stage, and tumor size were identified as independent risk factors for LM (Table 2), and a diagnostic nomogram was developed to predict the risk of LM in first-diagnosed STS patients (Figure 2). The AUCs of the nomogram were 0.806 in the training set (Figure 3A) and 0.799 in the testing set (Figure 3D). Furthermore, ROC curves and AUCs of each independent risk factor were also generated (Figure 4). These results suggested that the discrimination of any single risk factor was lower than that of the nomogram in either the training or testing set. In addition, the calibration curves of both sets suggested that the prediction of the nomogram was highly consistent with the actual observation (Figure 3B and E), and DCA indicated that this nomogram was an excellent risk-assessment tool for LM in first-diagnosed STS patients (Figure 3C and F).

Table 2.

Logistics Regression Analysis for Risk Factors of LM in STS Patients.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||

| <55 | Reference | |||

| ≥55 | 0.97 (0.775-0.214) | .793 | ||

| Race | ||||

| Black | Reference | |||

| Other a | 0.71 (0.432-1.167) | .177 | ||

| White | 0.803 (0.574-1.122) | .198 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 1.073 (0.857-1.343) | .54 | ||

| Histologic type | ||||

| Fibrosarcoma | Reference | |||

| Hemangiosarcoma | 2.426 (1.079-5.455) | .032 | 2.045 (0.867-4.823) | .102 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2.972 (1.882-4.692) | <.001 | 2.695 (1.682-4.317) | <.001 |

| Liposarcoma | 0.343 (0.185-0.634) | .001 | 0.316 (0.164-0.609) | .001 |

| MPNST | 1.749 (0.858-3.564) | .124 | 1.24 (0.598-2.571) | .563 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 4.706 (2.47-8.966) | <.001 | 2.148 (1.087-4.245) | .028 |

| Synovial sarcoma | 3.815 (2.254-6.458) | <.001 | 3.302 (1.907-5.72) | <.001 |

| Unclassified | 3.73 (2.239-6.215) | <.001 | 2.471 (1.453-4.203) | .001 |

| Other | 2.874 (1.903-4.34) | <.001 | 1.859 (1.215-2.844) | .004 |

| Grade | ||||

| Grade I | Reference | |||

| Grade II | 2.536 (1.287-4.998) | .007 | 1.248 (0.607-2.566) | .548 |

| Grade III | 8.481 (4.658-15.444) | <.001 | 2.706 (1.404-5.218) | .003 |

| Grade IV | 8.466 (4.693-15.274) | <.001 | 2.809 (1.467-5.377) | .002 |

| Tumor site | ||||

| Extremity | Reference | |||

| Head and neck | 0.639 (0.352-1.159) | .14 | ||

| Trunk | 1.148 (0.912-1.444) | .241 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | |||

| T2 | 5.722 (3.761-8.706) | <.001 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 6.588 (4.782-9.075) | <.001 | 4.368 (3.093-6.169) | <.001 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| <5 cm | Reference | |||

| 5 to 10 cm | 5.854 (3.507-9.771) | <.001 | 5.444 (3.239-9.152) | <.001 |

| >10 cm | 8.244 (4.998-13.6) | <.001 | 9.8 (5.877-16.342) | <.001 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Insured | Reference | |||

| Uninsured | 1.324 (0.758-2.313) | .324 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | Reference | |||

| Unmarried | 1.118 (0.895-1.396) | .325 | ||

Abbreviations: MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; LM, lung metastasis.

American Indian, Native Alaskan and Asian, Pacific Islander.

Figure 2.

Nomogram for predicting the risk of lung metastasis (LM) from soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients.

Figure 3.

The receiver operating characteristic curve (A), calibration curve (B), and decision curve analysis (C) of the training set; the receiver operating characteristic curve (D), calibration curve (E), and decision curve analysis (F) of the testing set.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve between the nomogram and each independent predictor in the training set (A) and the testing set (B).

Predictors of OS for STS Patients With LM and Prognostic Nomogram

A total of 442 eligible STS patients with LM were enrolled in the study cohort of prognostic analysis. Table 3 summarizes the baseline data of patients in the training set (N = 310) and testing set (N = 132) using R software, which were comparable in this study.

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics of STS Patients With LM.

| Variables | Total set (N = 442) |

Training set (N = 310) |

Testing set (N = 132) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | .666 | |||

| <55 | 194 (43.9%) | 134 (43.2%) | 60 (45.5%) | |

| ≥55 | 248 (56.1%) | 176 (56.8%) | 72 (54.5%) | |

| Race | .709 | |||

| Black | 62 (14.0%) | 41 (13.2%) | 21 (15.9%) | |

| Other a | 34 (7.7%) | 25 (8.1%) | 9 (6.8%) | |

| White | 346 (78.1%) | 244 (78.7%) | 102 (77.3%) | |

| Sex | .413 | |||

| Female | 177 (40.0%) | 128 (41.3%) | 49 (37.1%) | |

| Male | 265 (60.0%) | 182 (58.7%) | 83 (62.9%) | |

| Histologic type | .685 | |||

| Fibrosarcoma | 46 (10.4%) | 27 (8.7%) | 19 (14.4%) | |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 9 (2.0%) | 7 (2.3%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 80 (18.1%) | 58 (18.7%) | 22 (16.7%) | |

| Liposarcoma | 19 (4.3%) | 15 (4.8%) | 4 (3.0%) | |

| MPNST | 15 (3.4%) | 11 (3.5%) | 4 (3.0%) | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 165 (37.3%) | 117 (37.7%) | 48 (36.4%) | |

| Synovial sarcoma | 19 (4.3%) | 11 (3.5%) | 8 (6.1%) | |

| Unclassified | 42 (9.5%) | 30 (9.7%) | 12 (9.1%) | |

| Other | 47 (10.6%) | 34 (11.0%) | 13 (9.8%) | |

| Grade | .856 | |||

| Grade I | 13 (2.9%) | 8 (2.6%) | 5 (3.8%) | |

| Grade II | 43 (9.7%) | 29 (9.4%) | 14 (10.6%) | |

| Grade III | 149 (33.7%) | 104 (33.5%) | 45 (34.1%) | |

| Grade IV | 237 (53.6%) | 169 (54.5%) | 68 (51.5%) | |

| Tumor site | .293 | |||

| Extremity | 255 (57.7%) | 186 (60.0%) | 69 (52.3%) | |

| Head and neck | 14 (3.2%) | 10 (3.2%) | 4 (3.0%) | |

| Trunk | 173 (39.1%) | 114 (36.8%) | 59 (44.7%) | |

| T stage | .576 | |||

| T1 | 35 (7.9%) | 26 (8.4%) | 9 (6.8%) | |

| T2 | 407 (92.1%) | 284 (91.6%) | 123 (93.2%) | |

| N Stage | .828 | |||

| N0 | 361 (81.7%) | 254 (81.9%) | 107 (81.1%) | |

| N1 | 81 (18.3%) | 56 (18.1%) | 25 (18.9%) | |

| Tumor size | .541 | |||

| <5 cm | 28 (6.3%) | 22 (7.1%) | 6 (4.5%) | |

| 5 to 10 cm | 158 (35.7%) | 112 (36.1%) | 46 (34.8%) | |

| >10 cm | 256 (57.9%) | 176 (56.8%) | 80 (60.6%) | |

| Insurance status | .122 | |||

| Insured | 426 (96.4%) | 296 (95.5%) | 130 (98.5%) | |

| Uninsured | 16 (3.6%) | 14 (4.5%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Marital status | .726 | |||

| Married | 230 (52.0%) | 163 (52.6%) | 67 (50.8%) | |

| Unmarried | 212 (48.0%) | 147 (47.4%) | 65 (49.2%) | |

| Bone metastasis | .980 | |||

| No | 382 (86.4%) | 268 (86.5%) | 114 (86.4%) | |

| Yes | 60 (13.6%) | 42 (13.5%) | 18 (13.6%) | |

| Liver metastasis | .306 | |||

| No | 386 (87.3%) | 274 (88.4%) | 112 (84.8%) | |

| Yes | 56 (12.7%) | 36 (11.6%) | 20 (15.2%) | |

| Brain metastasis | .491 | |||

| No | 432 (97.7%) | 302 (97.4%) | 130 (98.5%) | |

| Yes | 10 (2.3%) | 8 (2.6%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Surgery | .098 | |||

| No | 163 (36.9%) | 122 (39.4%) | 41 (31.1%) | |

| Yes | 279 (63.1%) | 188 (60.6%) | 91 (68.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy | .774 | |||

| No | 143 (32.4%) | 99 (31.9%) | 44 (33.3%) | |

| Yes | 299 (67.6%) | 211 (68.1%) | 88 (66.7%) | |

| Radiotherapy | .796 | |||

| No | 247 (55.9%) | 172 (55.5%) | 75 (56.8%) | |

| Yes | 195 (44.1%) | 138 (44.5%) | 57 (43.2%) | |

Abbreviations: MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; LM, lung metastasis.

American Indian, Native Alaskan and Asian, Pacific Islander.

Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses determined 4 independent prognostic factors for OS of STS patients with LM, including age, N stage, surgery, and chemotherapy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis for STS Patients With LM.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||

| <55 | Reference | |||

| ≥55 | 1.789 (1.381-2.317) | <.001 | 1.799 (1.376-2.352) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | Reference | |||

| Other a | 0.855 (0.489-1.493) | .581 | ||

| White | 0.916 (0.641-1.309) | .63 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.978 (0.758-1.261) | .863 | ||

| Histologic type | ||||

| Fibrosarcoma | Reference | |||

| Hemangiosarcoma | 3.555 (1.517-8.332) | .004 | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 0.74 (0.449-1.218) | .236 | ||

| Liposarcoma | 1.138 (0.579-2.238) | .708 | ||

| MPNST | 0.634 (0.273-1.473) | .29 | ||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.773 (0.359-1.665) | .511 | ||

| Synovial sarcoma | 0.515 (0.279-0.949) | .033 | ||

| Unclassified | 1.442 (0.845-2.46) | .179 | ||

| Other | 0.893 (0.569-1.399) | .62 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| Grade I | Reference | |||

| Grade II | 0.93 (0.369-2.346) | .878 | ||

| Grade III | 1.48 (0.644-3.4) | .355 | ||

| Grade IV | 1.532 (0.675-3.478) | .307 | ||

| Tumor site | ||||

| Extremity | Reference | |||

| Head and neck | 1.741 (0.886-3.421) | .108 | ||

| Trunk | 1.097 (0.846-1.423) | .484 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | |||

| T2 | 1.177 (0.737-1.881) | .495 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| N1 | 1.462 (1.07-1.997) | .017 | 1.513 (1.101-2.079) | .011 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| <5 cm | Reference | |||

| 5 to 10 cm | 1.035 (0.607-1.766) | .899 | ||

| >10 cm | 1.155 (0.689-1.938) | .584 | ||

| Insurance status | ||||

| Insured | Reference | |||

| Uninsured | 0.941 (0.526-1.681) | .836 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | Reference | |||

| Unmarried | 1.229 (0.956-1.579) | .107 | ||

| Bone metastasis | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.404 (0.988-1.993) | .058 | ||

| Liver metastasis | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.212 (0.827-1.776) | .325 | ||

| Brain metastasis | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 2.31 (1.139-4.685) | .02 | ||

| Surgery | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.513 (0.396-0.665) | <.001 | 0.505 (0.388-0.657) | <.001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.709 (0.543-0.926) | .012 | 0.748 (0.567-0.986) | .039 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.798 (0.62-1.027) | .08 | ||

Abbreviations: MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; LM, lung metastasis.

American Indian, Native Alaskan and Asian, Pacific Islander.

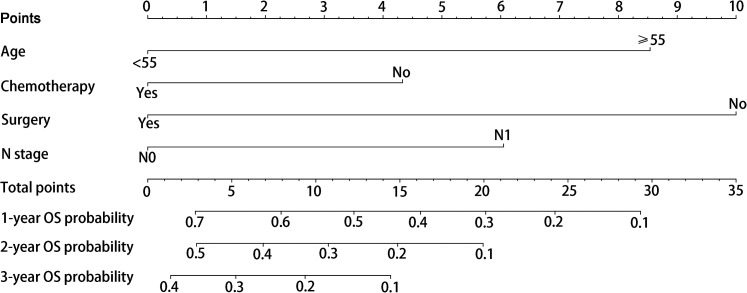

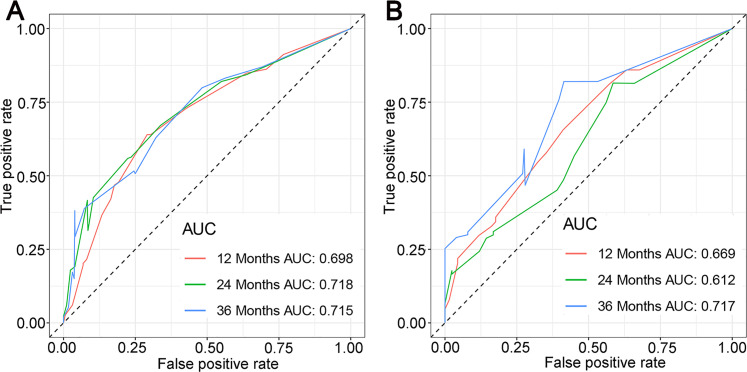

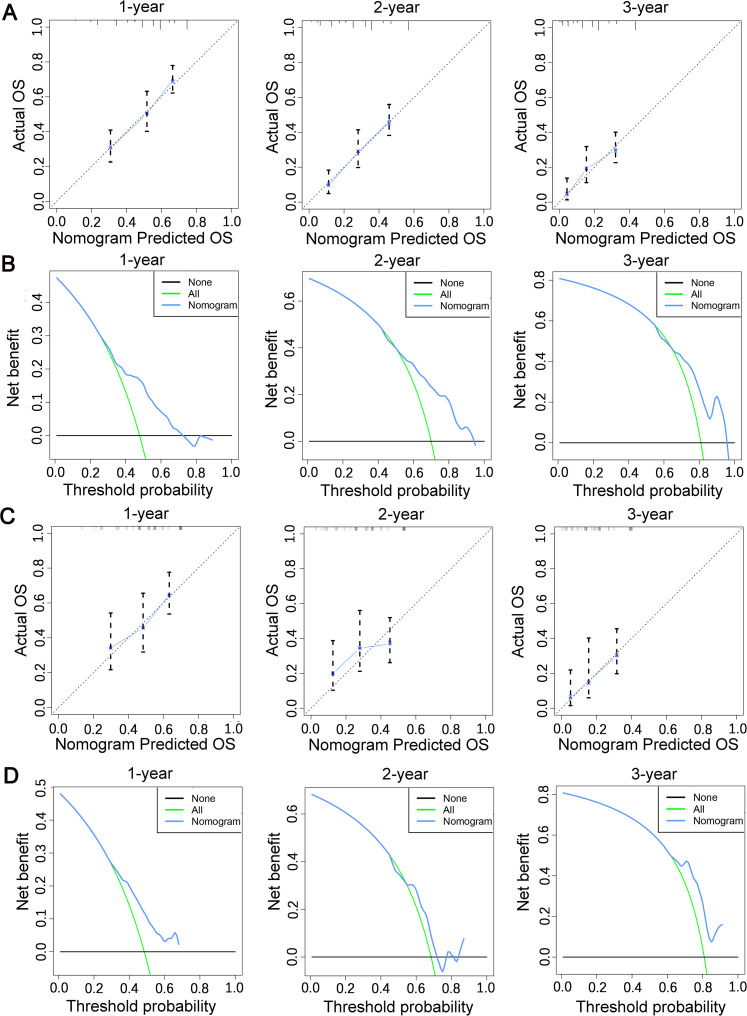

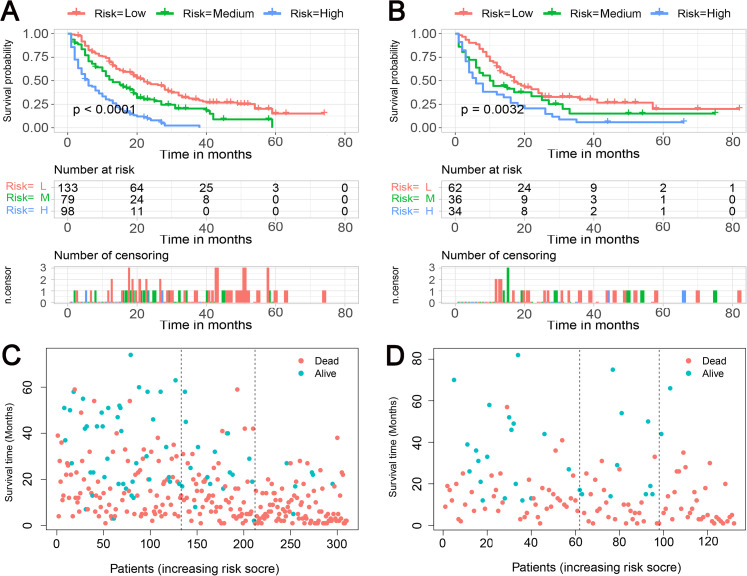

Finally, the abovementioned independent prognostic predictiors were incorporated to construct the prognostic nomogram for predicting 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS in STS patients with LM (Figure 5). In addition, validation was conducted in the training and testing sets, respectively. ROC curves showed that the AUCs of this prognostic nomogram for 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS reached 0.698, 0.718, and 0.715 in the training set (Figure 6A) and 0.669, 0.612, and 0.717 in the testing set (Figure 6B). The calibration curves for 1-, 2-, and 3-year showed significant consistency between the predictive survival and actual survival in both sets (Figure 7A and C). As shown by DCA, the nomogram demonstrated positive net benefits across a wide range of death risks in both sets, indicating its favorable clinical utility in predicting 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS (Figure 7B and D). Furthermore, we calculated the total scores for each patient based on this prognostic nomogram and then used X-tile software version 3.6.1 (Yale University School of Medicine) to determine the optimal cutoff values of the risk score and divided the patients into 3 subgroups for Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, which showed that patients in the high-risk group did demonstrate worse survival than patients in the median- and low-risk groups (Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Prognostic nomogram for predicting 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival (OS) for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients with lung metastasis (LM).

Figure 6.

The receiver operating characteristic curve in the training set (A) and in the testing set (B).

Figure 7.

The calibration curves of the nomogram in the training set (A) and in the testing set (C); the decision curve analysis of the nomogram in the training set (B) and in the testing set (D).

Figure 8.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis of the training set (A) and testing set (B); Kaplan-Meier survival status analysis of the training set (C) and testing set (D).

Discussion

Overall study findings STS with LM are an advanced stage of STS with a particularly poor prognosis. 23 Given its high heterogeneity, the clinical outcome of STS patients with LM differs from person to person. The risk of LM and survival prediction in patients with LM has been investigated widely in the context of other malignancies.24‐26 In this study, the probability of LM in first-diagnosed STS patients can be easily evaluated based on the diagnostic nomogram, which potentially guides the LM screening and further clinical management. Likewise, the prognostic nomogram provided the individualized prediction of 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS for STS patients with LM. Moreover, both nomograms showed excellent reliability in the risk assessment of LM and survival prediction in STS patients with LM, as indicated by ROC curves, AUCs, and calibration curves. Furthermore, DCA demonstrated the effective clinical applicability of the models with wide threshold probabilities. Several of our findings warrant further discussion.

Risk Assessment of LM Among First-Diagnosed STS Patients

As shown in our study, 4 clinicopathological variables, including grade, histologic type, N stage, and tumor size, were independent risk factors for LM in patients first diagnosed with STS. Among these variables, histology had the highest discrimination. Synovial sarcoma was considered the STS type with the highest risk for LM. The reason for this outcome may be that histological differentiation can create different biological characteristics of the sarcomas, and metastasis is mainly related to the biological characteristics of the lesion. Besides, based on the view of differentiation, mitotic count and tumor necrosis, tumor grade is closely correlated with the occurrence of metastases. 27 The association between tumor differentiation and LM in STS patients was confirmed in a previous study. 28 Moreover, synovial sarcomas of grade 3 according to the FNCLCC system more often developed metastases than did grade 2 tumors. 29 In addition, we also observed that larger tumor and lymph node metastasis (LNM) were more likely to correlate with LM. Some potential explanations are that changes in tumor size may be closely related to its biological behavior and LNM is regarded as a prerequisite for malignant tumor invasion and metastasis.30,31 David et al also supported the notion that lymph node positivity is a predictive sign of biological aggressiveness and distant metastasis. 32 Taken together, STS patients with the characteristics of higher grade, histologic type of synovial sarcoma, LNM, and tumor size larger than 10 cm were associated with increased risk of LM at initial diagnosis and justified more thorough chest computer tomography scanning. 5

Diagnostic, Prognostic, Quality of Life, Survival, and Therapeutic Procedures

The effective prognostic study of STS patients with LM will be of great help to clinicians. According to our findings, age at diagnosis was an independent prognostic factor and had a distinctly positive association with death risk in STS patients with LM. Although Chudgar and colleagues found that patients aged ≥50 had similar median disease-free and OS compared to younger patients. 33 The association of increasing age with decreased survival in our cohort is likely multifactorial, with increasing age potentially representing an increasing rate of comorbidities and decreased tolerance of loss of lung parenchyma. This difference in results could also be due to selection bias in single institution compared to multi-institutional studies. Increasing age has been associated with decreased survival in patients with STS in other large, multi-institutional studies; for example, Carbonnaux and colleagues observed this association in retrospective analysis using the data from 3 national reference centers designated by the French National Center Institute. 34 On the other hand, although LNM is rare in sarcomas patients, patients with LNM do have more undesirable survival. One possible reason for this may be that they are more likely to have LM. Besides, it was noteworthy that surgery of the primary site displayed the most powerful prognostic value for OS. Although the significance of pulmonary metastasectomy has been extensively investigated in STS patients with LM, it has been proven to be associated with increased survival and improved quality of life.23,35,36 However, the treatment regimen of STS patients with LM remains a challenge, as local treatment regimens have rarely been studied. In 2018, Krishnan et al 37 reviewed 43 cases of STS patients presenting with metastasis at diagnosis who underwent resection of the primary tumor and found that the median survival of 22 months in this study was better than the previously reported median survival of 12 months in patients treated with palliative chemotherapy. 38 In our cohort, surgical resection of primary tumors also improved the OS of STS patients with LM. One possible reason is a multidirectional process whereby circulating cancer cells can seed distant organs as well as the primary tumor. 39 Circulating cancer cells in metastatic diseases seem to be recruited by cytokines, particularly interleukin 6, secreted by the primary tumor. 40 Primary tumor resection might, thus, reduce levels of circulating cancer cells and so prolong survival in patients with metastatic STS. Surgical resection of the primary tumor could reduce carcinomatous pain, resulting in improved performance status. Performance status is one of the most significant indicators for determining treatment strategies among patients with malignant neoplasms. Improved performance status might allow administration of systemic chemotherapy even among patients with severe general condition. Therefore, both primary tumors and pulmonary metastases should be actively recommended to obtain the maximum survival time. STS with LM was considered the advanced stage, and palliative chemotherapy was often the treatment of choice for patients at this stage. To date, some published clinical studies have justified the administration of doxorubicin as the standard first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic STS.12,41,42 Another study by Grünwald et al suggested that pazopanib had a positive effect on survival in patients with metastatic STS aged 60 years or older. 43 In recent years, treatment with second-line agents for advanced STS has been often histology-driven,44,45 and novel therapeutic agents, such as trabectedin and eribulin, have shown a role in some sarcoma subtypes. Therefore, newly developed agents may expand the treatment options and improve the prognosis of patients with metastatic STS in the near future. Interestingly, radiotherapy did not seem to play an important role in improving prognosis in our model, which was impressive and puzzling. Harati et al also found that radiation did not significantly improve local recurrence-free survival or disease-specific survival in somatic LMS. 43 However, a recent systematic review reported local control of LM from STS with stereotactic body radiotherapy, compared with surgery, was associated with a lower cumulative overall death rate. 46 Therefore, prospective trials are urgently required for further confirmation. In general, it can be well predicted the 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS of STS patients with LM based on 4 independent prognostic factors, which providing guidance for personalized patient consultation and risk-adapted clinical management.

Limitations

Undeniably, some limitations in this study should be considered. First, patients with missing data on the collected variables were excluded, which led to inevitable selective bias. In addition, the information derived from the SEER database was about the disease at the initial diagnosis, which meant that LM occurring in the clinical follow-up cannot be analyzed. Finally, neither nomogram was externally validated in the clinical setting owing to insufficiency of cases.

Conclusion

The present study showed that grade, N stage, histologic type, and tumor size were independent risk factors for LM from STS, and age, N stage, surgery, and chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors of OS for STS patients with LM. The 2 nomograms we developed may be individual, visual, and more intuitive convenient predictive models for risk assessment and survival prediction for LM from STS.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the contribution of the SEER database and the 18 registries supplying cancer research information, and thank all colleagues involved in the study for their contributions.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- AUC

area under the curve

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computer tomography

- DCA

decision curve analyses

- DM

distant metastases

- HR

hazard ratio

- LM

lung metastasis

- LNM

lymph node metastasis

- MPNST

malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

- OR

odd ratio

- OS

overall survival

- PD-L1

programmed death ligand 1

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SBRT

stereotactic body radiotherapy

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- STS

soft tissue sarcoma

- TNM

Tumor, Node, Metastasis.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Zhiyi Fan and Changxing Chi contributed equally. ZF and SY conceived the study design. ZF, YT, and CC supervised the data collection and literature review. YT, ZH, and YS generated the tables and figures. ZF drafted the manuscript. ZF and CC revised the manuscript. SY is responsible for this article. The data analyzed during the current study are available from the SEER data set repository, or the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the SEER database (https://seer.cancer.gov/). We received permission to access the research data file in the SEER programme from the National Cancer Institute, US (reference number 15260-Nov2018). Approval was waived by the local ethics committee, as SEER data are publicly available and de-identified.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Youxin Song https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2954-0871

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.van der Graaf W, Orbach D, Judson I, Ferrari A. Soft tissue sarcomas in adolescents and young adults: a comparison with their paediatric and adult counterparts. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):e166‐e175. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30099-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harati K, Goertz O, Pieper A, et al. Soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities: surgical margins can be close as long as the resected tumor has no ink on it. Oncologist. 2017;22(11):1400-1410. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callegaro D, Miceli R, Bonvalot S, et al. Development and external validation of a dynamic prognostic nomogram for primary extremity soft tissue sarcoma survivors. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;17:100215. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan M, Antonescu C, Moraco N, Singer S. Lessons learned from the study of 10,000 patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2014;260(3):416-421. 10.1097/sla.0000000000000869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamboa A, Ethun C, Switchenko J, et al. Lung surveillance strategy for high-grade soft tissue sarcomas: chest x-ray or CT scan?. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(5):449-457. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft-tissue sarcoma of adults: meta-analysis of individual data. Sarcoma meta-analysis collaboration. J Lancet (London, England). 1997;350(9092):1647-1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iqbal N, Shukla N, Deo S, et al. Prognostic factors affecting survival in metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 110 patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(3):310-316. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1369-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedi M, King D, Charlson J, et al. Multimodality management of metastatic patients with soft tissue sarcomas may prolong survival. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(3):272-277. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318277d7e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stojadinovic A, Leung D, Hoos A, Jaques D, Lewis J, Brennan M. Analysis of the prognostic significance of microscopic margins in 2,084 localized primary adult soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):424-434. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueda T, Uchida A, Kodama K, et al. Aggressive pulmonary metastasectomy for soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 1993;72(6):1919-1925. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espat N, Bilsky M, Lewis J, Leung D, Brennan MJC. Soft tissue sarcoma brain metastases. Prevalence in a cohort of 3829 patients. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2706-2711. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Judson I, Verweij J, Gelderblom H, et al. Doxorubicin alone versus intensified doxorubicin plus ifosfamide for first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):415-423. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70063-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto Y, Kanzaki R, Kanou T, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic factors of pulmonary metastasectomy for osteosarcoma and soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24(7):863-870. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01422-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno T, Taniguchi T, Ishikawa Y, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy for osteogenic and soft tissue sarcoma: who really benefits from surgical treatment? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43(4):795-799. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dear R, Kelly P, Wright G, Stalley P, McCaughan B, Tattersall M. Pulmonary metastasectomy for bone and soft tissue sarcoma in Australia: 114 patients from 1978 to 2008. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8(3):292-302. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuoka M, Onodera T, Yokota I, et al. Surgical resection of primary tumor in the extremities improves survival for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma patients: a population-based study of the SEER database. Clin Transl Oncol. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s12094-021-02646-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindner L, Litière S, Sleijfer S, et al. Prognostic factors for soft tissue sarcoma patients with lung metastases only who are receiving first-line chemotherapy: an exploratory, retrospective analysis of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (EORTC-STBSG). Int J Cancer. 2018;142(12):2610-2620. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Italiano A, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Cesne A, et al. Trends in survival for patients with metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2011;117(5):1049-1054. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawamura C, Springfield D, Marcus K, Perez-Atayde A, Gebhardt M. Factors predicting local recurrence, metastasis, and survival in pediatric soft tissue sarcoma in extremities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(11):3019-3027. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1398-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RStudio Team R. Integrated Development for R. Available at: http://www.rstudio.com/. Accessed June 21, 2017.

- 21.R RDCT. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 2.0-0. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2011.

- 22.Vickers A, Elkin E. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(6):565-574. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamoto T, Hara H, Morishita M, et al. Prognostic influence of the treatment approach for pulmonary metastasis in patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2020;37(4):509-517. doi: 10.1007/s10585-020-10038-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie L, Huang W, Wang H, Zheng C, Jiang J. Risk factors for lung metastasis at presentation with malignant primary osseous neoplasms: a population-based study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-1571-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X, Zhao J, Bai J, et al. Risk and clinicopathological features of osteosarcoma metastasis to the lung: a population-based study. J Bone Oncol. 2019;16:100230. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2019.100230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song K, Song J, Lin K, et al. Survival analysis of patients with metastatic osteosarcoma: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End results population-based study. Int Orthop. 2019;43(8):1983-1991. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04348-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillou L, Coindre J, Bonichon F, et al. Comparative study of the national cancer institute and French federation of cancer centers sarcoma group grading systems in a population of 410 adult patients with soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(1):350-362. doi: 10.1200/jco.1997.15.1.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coindre J, Terrier P, Guillou L, et al. Predictive value of grade for metastasis development in the main histologic types of adult soft tissue sarcomas: a study of 1240 patients from the French federation of cancer centers sarcoma group. Cancer. 2001;91(10):1914-1926. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trassard M, Le Doussal V, Hacène K, et al. Prognostic factors in localized primary synovial sarcoma: a multicenter study of 128 adult patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(2):525-534. doi: 10.1200/jco.2001.19.2.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munajat I, Zulmi W, Norazman M, Wan Faisham W. Tumour volume and lung metastasis in patients with osteosarcoma. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2008;16(2):182-185. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emori M, Tsuchie H, Nagasawa H, et al. Early lymph node metastasis may predict poor prognosis in soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Surg Oncol. 2019;2019:6708474. doi: 10.1155/2019/6708474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johannesmeyer D, Smith V, Cole D, Esnaola N. The impact of lymph node disease in extremity soft-tissue sarcomas: a population-based analysis. Am J Surg. 2013;206(3):289-295. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chudgar N, Brennan M, Munhoz R, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy with therapeutic intent for soft-tissue sarcoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;154(1):319-330.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.02.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carbonnaux M, Brahmi M, Schiffler C, et al. Very long-term survivors among patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;8(4):1368-1378. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Predina J, Puc M, Bergey M, et al. Improved survival after pulmonary metastasectomy for soft tissue sarcoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(5):913-919. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182106f5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dossett L, Toloza E, Fontaine J, et al. Outcomes and clinical predictors of improved survival in a patients undergoing pulmonary metastasectomy for sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(1):103-106. doi: 10.1002/jso.23961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnan C, Kim H, Park J, Han I. Outcome after surgery for extremity soft tissue sarcoma in patients presenting with metastasis at diagnosis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(7):681-686. doi: 10.1097/coc.0000000000000346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constantinidou A, van der Graaf W. The fate of new fosfamides in phase III studies in advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2017;84:257-261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Comen E, Norton L, Massagué J. Clinical implications of cancer self-seeding. Eur J Cancer. 2011;8(6):369-377. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Ma Q, Liu T, et al. Tumor self-seeding by circulating tumor cells in nude mouse models of human osteosarcoma and a preliminary study of its mechanisms. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;140(2):329-340. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1561-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seddon B, Strauss S, Whelan J, et al. Gemcitabine and docetaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line treatment in previously untreated advanced unresectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas (GeDDiS): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(10):1397-1410. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30622-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tap W, Wagner A, Schöffski P, et al. Effect of doxorubicin plus olaratumab versus doxorubicin plus placebo on survival in patients With advanced soft tissue sarcomas: the ANNOUNCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1266-1276. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grünwald V, Karch A, Schuler M, et al. Randomized comparison of pazopanib and doxorubicin as first-line treatment in patients With metastatic soft tissue sarcoma age 60 years or older: results of a German Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(30):3555-3564. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.00714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singhi E, Moore D, Muslimani AJP. Metastatic soft tissue sarcomas: a review of treatment and new pharmacotherapies. J Clin Oncol. 2018;43(7):410-429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.In G, Hu J, Tseng W. Treatment of advanced, metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: latest evidence and clinical considerations. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9(8):533-550. doi: 10.1177/1758834017712963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tetta C, Londero F, Micali L, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy versus metastasectomy in patients with pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020;32(5):303-315. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]