Abstract

Elevated levels of miR-21 expression are associated with many cancers, suggesting it may be a promising clinical biomarker. In prostate cancer (PCa), however, there is still no consensus about the usefulness of miR-21 as an indicator of disease progression. This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to investigate the value of miR-21 expression as a prognostic measurement in PCa patients. Medline (Ovid), EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane Library databases were systematically searched for relevant publications between 2010 to 2021. Studies exploring the relationship between miR-21 expression, PCa prognosis and clinicopathological factors were selected for review. Those reporting hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were subject to meta-analyses. Fixed-effect models were employed to calculated pooled HRs and 95% CIs. Risk of bias in each study was assessed using QUIPS tool. Certainty of evidence in each meta-analysis was assessed using GRADE guidelines. A total of 64 studies were included in the systematic review. Of these, 11 were eligible for inclusion in meta-analysis. Meta-analyses revealed that high miR-21 expression was associated with poor prognosis: HR = 1.58 (95% CI = 1.19–2.09) for biochemical recurrence, MODERATE certainty; HR = 1.46 (95% CI = 1.06–2.01) for death, VERY LOW certainty; and HR = 1.26 (95% CI = 0.70–2.27) for disease progression, VERY LOW certainty. Qualitative summary revealed elevated miR-21 expression was significantly positively associated with PCa stage, Gleason score and risk groups. This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that elevated levels of miR-21 are associated with poor prognosis in PCa patients. miR-21 expression may therefore be a useful prognostic biomarker in this disease.

Keywords: meta analysis, microRNA, miR-21, prognostic, prostate cancer, systematic

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer for males in 105 countries including North and South America, Western Europe and Australia [1]. The majority of PCa cases are localized disease with very high survival rate after initial treatment (∼100% 5-year survival), but recurrence may occur in about 40% as biochemical recurrence (BCR) or distant metastasis that has a significantly poorer prognosis (∼30% 5-year survival) [2]. Additionally, some may progress as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) or develop chemoresistance [3].

Currently, prognosis is predicted by considering cancer stage, Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, patient’s health condition, treatment choice and treatment response [4]. However, these clinicopathological factors still have certain limitations. For example, Gleason score is a histological method which is subject to inter-observer variability, and clinicians can find the grading system confusing [5,6]. Staging may vary between clinical and pathological estimation, forcing clinicians to alter treatment regime, and prognosis for lower stage cancer is less than predictable [7]. PSA lacks specificity and BCR, defined by rise in PSA level following prostatectomy or radiotherapy, does not necessarily predict clinical recurrence or metastasis with sufficient accuracy [8]. Therefore, there is still a clear clinical need for novel molecular markers that may overcome some of these limitations [9].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of non-coding molecules which have emerged as strong candidates for useful clinical biomarkers [10]. Over the past decade, they have been actively researched in a wide range of diseases, including prostate cancer [11,12]. miRNAs are estimated to regulate 60% of gene expression in human and some specifically target oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes [10,11]. The aberrant expression of miRNAs can therefore contribute to cancer development and several dysregulated miRNAs have been associated with PCa progression [12,13]. Importantly, miRNAs can be detected in blood and urine, as well as tissue. Indeed, they are known to be more stable in biofluids than other nucleic acids which give them potential as diagnostic or prognostic markers [13,14]. However, more research is needed to understand which miRNAs are most relevant in prostate cancer.

miR-21 is one of the most studied miRNAs and there is a large body of evidence to suggest that it has a predominantly oncogenic function since it is over-expressed in many cancers [14]. As one of the first miRNAs to be categorized as an ‘oncomiR’, it has been subsequently evaluated for its potential use as a clinical biomarker in various cancers [15–17]. Several recent systematic reviews have found evidence that circulating miR-21 levels can predict poor prognosis in esophageal, pancreatic, colorectal and breast cancers [18,19]. In urological cancers, including PCa, Chen et al. found some evidence that miR-21 over-expression was significantly associated with unfavorable prognosis in their integrated analysis [20]. However, despite evidence that it can contribute to PCa development, no systematic review or meta-analysis to date has been carried out specifically for miR-21 in this setting. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to systematically evaluate studies related to prognostic value of miR-21 in PCa, appraising study qualities and synthesising evidence by meta-analyses, data association and qualitative summary.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

This review was conducted following a protocol which was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) under the registration ID: CRD42020183408 on 23 June 2020. The protocol was developed following guidance on PRISMA-P [21], systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies [22] and the checklist of items recommended in the PRISMA statement [23].

Search strategy

Electronic databases from which records were retrieved include Medline (Ovid), EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane Library, covering publications from 2010 to 2021 and they were last searched on 8 November 2021. Additionally, reference lists of included studies and relevant review papers were searched manually. Prognostic factor studies were prone to selective reporting in that miRNAs with insignificant findings might not be reported [24]; therefore, a high-sensitivity approach was used in the search strategy as shown in Supplementary Table ST 1. Key words related to miRNAs, in addition to miR-21, were included to broaden the search to cover relevant studies that measured miR-21 but did not report the result. Retrieved records from databases were exported to systematic review manager Rayyan where duplicates were removed [25]. Titles and abstracts of remaining records were screened for relevance independently by two reviewers. Full text of studies selected for inclusion were subsequently imported into another systematic review manager Covidence (www.covidence.org) where studies were assessed for eligibility in duplicate. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion in the systematic review, original peer-reviewed human studies published in English from year 2010 to 2021 with full-text available online or from Ulster University Library were included. In vitro, in silico and in vivo studies that did not include human participants were excluded. Studies without original human data that analyzed publicly available human data (e.g., from The Cancer Genome Atlas repository) were not included to avoid multiple counting of sample size. Review-type studies and duplicate reports were excluded for the same reason. If the same study was published in multiple journals, only the most informative or the most recent one was included. Studies published before 2010 were excluded due to advances in miRNA technology.

For meta-analyses, studies with characteristics specified by PICOT (Table 1) were eligible for inclusion in meta-analysis [22]. Length of follow-up was not restricted to broaden the number of inclusions and increase the number of eligible studies.

Table 1. PICOT eligibility criteria.

| P | Population | Male patients of any age worldwide diagnosed with PCa. |

|---|---|---|

| I | Index prognostic factor | Measurement of miR-21 levels in tissue or circulating/fluid samples such as tumour tissue, blood, plasma, serum, urine and seminal fluid. |

| C | Comparator prognostic factors | Clinicopathological factors such as stage, grade, Gleason score, PSA level and health condition (e.g., recurrence, metastasis). |

| O | Outcomes of interest | Survival outcomes of any type (e.g., OS, RFS) estimated in HR, 95% CI, P-value and/or survival curves with log-rank P-value. |

| T | Timing | Samples taken as baseline at the start of follow-up of any length. |

Studies with characteristics specified by PICOT were eligible for inclusion in meta-analysis.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PCa, prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Data collection process

A data extraction form adapted from CHARMS-PF checklist [22] was created within Covidence to capture information about each study, source of data, PICOT details, sample size, missing data, statistical analysis methods, survival outcome results and/or association analysis results (Supplementary Table ST 2). Data were extracted independently in duplicate into separate forms. Completed forms were compared, and conflicts were resolved through discussion. Authors of 12 studies were contacted for missing data or clarifications (Supplementary Table ST 3). Only data relevant to prognosis were considered; therefore, data related to diagnosis and healthy or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) controls were disregarded.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Judgment was made independently in duplicate using the Quality in Prognostic Factor Studies (QUIPS) tool that assesses risk of bias as HIGH, MODERATE, LOW or UNCLEAR in six domains (Supplementary Table ST 4) [26]. For domain 3 ‘Prognostic factor measurement’, methods accepted as reliable for miR-21 measurement were qPCR, sequencing and array technology. For domain 5 ‘Adjustment for covariates’, the core set of desired adjustment covariates was predefined as Gleason score/grade and pathological/clinical stage.

Statistical analysis

The principal summary measure for meta-analysis was hazard ratio (HR), presented with 95% confidence interval (CI) and P-value. Kaplan–Meier plot presented with log-rank P-value was also accepted. Eligible studies of similar design in terms of outcome and handling of miR-21 data were grouped into separate meta-analyses. For each meta-analysis effect estimates were pooled as HR (95% CI) based on fixed-effect inverse variance method in the review manager RevMan5.4 [27]. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of the forest plot, chi-square (Chi2) test and I2 test (Chi2 P≤0.1 indicates significant heterogeneity; I2<30% denotes low/unimportant heterogeneity, 30–60% moderate heterogeneity, 50–90% substantial heterogeneity and 75–100% considerable heterogeneity). Impact on the robustness of analyses by the presence of an outlier and the inclusion of a study that introduced clinical heterogeneity was assessed by sensitivity analyses. For qualitative summary, association measure included but was not limited to correlation, fold change (FC) or mean difference.

Certainty of evidence

For each analysis the certainty of evidence was rated according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines [28]. This review estimated the prognostic value of miR-21 in PCa as an exploratory study without direct association with clinical decision making; therefore, certainty was rated based on the non-contextualized setting as HIGH, MODERATE, LOW or VERY LOW certainty. Starting from HIGH certainty, evidence could be rated down in five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias; or rated up in three domains: large effect, dose−response and plausible confounding. Assessment of publication bias was not possible due to low number of studies eligible for each analysis, which meant any test of bias would be underpowered.

Results

Study selection

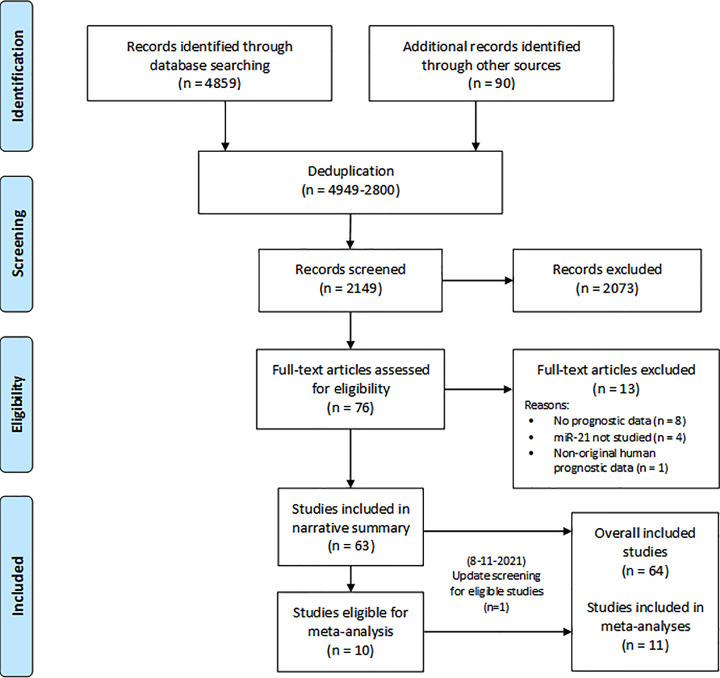

Study selection was as shown in the flow diagram (Figure 1). Up until 23 July 2020, 4859 records were retrieved from database searching and a further 90 were identified from manual searching of reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews. After duplicates were removed (n=2800), record screening identified 76 eligible studies for full-text assessment. Thirteen full-text articles were ineligible due to lack of prognostic data (n=8), lack of miR-21 data (n=4) and lack of original human prognostic data (n=1) (Supplementary Table ST 5). The remaining 63 studies [29–77,79–92] were included in the systematic review, with 10 eligible for meta-analysis. On 8 November 2021, an update screening for meta-analysis identified one more eligible study [78], bringing the total number of included studies to 64, with 11 eligible for meta-analysis.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram (adapted from Moher et al. [23]).

Study characteristics

Characteristics of all 64 studies included in this systematic review are summarized in Supplementary Table ST 6. Each included study was assigned a Study ID composed of first author’s name and publication year. The PICOT eligibility criteria (Table 1) identified studies on PCa patient cohorts which could be stratified against measurable parameters and outcomes for inclusion in the meta-analysis. A total of 11 studies, with study sizes ranging from 31 to 478 participants, encompassing 1485 PCa patients total, were eligible for meta-analysis (Tables 2 and 3). Amankwah, 2013 [31] indicated that the recurrent group was oversampled, no rationale was provided. Sharova, 2021 [78] was clearly indicated as prospective; Zedan, 2017 [85] and Zhao, 2019a [89] were clearly indicated as retrospective studies. Cohort types were projected for the rest judging by the details contained. Thus, six studies appeared to be prospective (Guan, 2016 [42]; Leite, 2015 [60]; Lin, 2014 [64]; Lin, 2017 [65]; Sharova, 2021 [78]; Yang, 2016 [84]) and four were retrospective (Amankwah, 2013 [31]; Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68]; Zedan, 2017 [85]; Zhao, 2019a [89]); it was unclear for Li, 2012 [61].

Table 2. Characteristics of 11 studies eligible for meta-analyses.

| Study ID, Type | Study size | P | I | C | O | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amankwah, 2013 [31] Retrospective |

65 | PCa histologically confirmed; Underwent RP Non-recurrent median age = 59 (47–75) Recurrent (oversampled) median age = 57 (46–75) |

High/low miR-21, -221 & -222 in FFPE tissue (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

Age; BMI; cT; GS | RFS4 | 3–254 months |

| Guan, 2016 [42] Prospective |

85 | PCa pathologically confirmed; Underwent ADT1 Mean age = 75 ± 7.7 |

High/low levels of 7 miRNAs (including miR-21) in FFPE tissue (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

Age; cT; GS; PSA | PFS5 | 14–95 months |

| Leite, 2015 [60] Prospective |

127 | Localized PCa; Underwent RP Mean age = 63 ± 7.6 |

High/low miR-21 in FFPE tissue (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

GG; PSA; pT | RFS6 | 2–120 months |

| Li, 2012 [61] (unclear) |

168 | PCa pathologically confirmed; Underwent RP and regional lymph node dissection Low miR-21 median age = 68 (56–77) High miR-21 median age = 67 (48–77) |

High/low miR-21 in FFPE tissue (LNA-ISH) |

Age; Capsular invasion; GS; pN; PSA; pT; Surgical margin | RFS6 | 2–80 months |

| Lin, 2014 [64] Prospective |

97 | CRPC patients; Underwent docetaxel chemotherapy Median age = 68 (46–87) |

High/low levels of 46 miRNAs (including miR-21) in plasma/serum (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

Age; Alkaline phosphatase; GS; Haemoglobin; PSA; Visceral metastasis | OS | 3–62 months |

| Lin, 2017 [65] Prospective |

87 | CRPC patients; Underwent docetaxel chemotherapy Median age = 72 (40–89) |

High/low levels of 14 miRNAs (including miR-21) in plasma (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

Alkaline phosphatase; Hemoglobin; PSA | OS | 0.7–45 months |

| Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68] Retrospective |

478 | PCa patients; Underwent RP Median age = 62 (45–75) |

High/low levels of 7 miRNAs (including miR-21-5p) in FFPE tissue (RT-qPCR) |

GG; Perineural infiltration; PSA; pT; Surgical margins; Tumor size; Vascular infiltration | RFS7 | 6–188 months |

| Sharova, 2021 [78] Prospective |

31 | mCRPC patients; Treated with ARTA2 Median age = 75 (69.5–80.5) |

High/low levels of miR-21, -141 & -223 in plasma (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

GS; Hemoglobin; Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; PSA; Time to CRPC | OS PFS8 |

Median = 36.6 months |

| Yang, 2016 [84] Prospective |

92 | PCa pathologically confirmed; Underwent resection Mean age = 60 ± 6 |

High/low miR-21 in PBMC (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

Age; cT; GS; PSA | OS | 21–69 months |

| Zedan, 2017 [85] Retrospective |

49 | Localised PCa; Underwent RP & regional lymph node dissection Mean age = 62.7 (52–71) |

Continuous levels of 6 miRNAs (including miR-21) in FFPE tissue (ISH analysed by computer software) |

GS; PSA; pT | RFS6 | (Not stated) |

| Zhao, 2019a [89] Retrospective |

206 | PCa patients; Underwent RP Median age = 63 (47–74) |

Continuous levels of 20 miRNAs (including miR-21-5p) in FFPE tissue (TaqMan RT-qPCR) |

Age; DRE; PSA; ISUP grade3; pN; Prostate volume; pT; Surgical margin | RFS6 | 17–180 months |

Abbreviations: ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; ARTA, androgen receptor-targeted agents; BMI, body mass index; C, comparator prognostic factors; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; cT, clinical tumor stage; DRE, digital rectal examination; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; GG, Gleason grade; GS, Gleason score; I, index prognostic factor; ISH, in situ hybridization; ISUP, International Society of Urological Pathology; LNA-ISH, locked nucleic acid in situ hybridization; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; O, outcomes of interest; OS, overall survival; P, population; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PCa, prostate cancer; PFS, progression-free survival; pN, lymph node metastasis; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; pT, pathological tumor stage; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

1ADT included surgical castration or luteinising hormone-releasing hormone agonist combined with an antiandrogen according to Guan, 2016 [42].

2ARTA included abiraterone (n=10) and enzalutamide (n=21) according to Sharova, 2021 [78].

3ISUP grading system was based on Gleason score according to Zhao, 2019a [89].

4Endpoint included biochemical recurrence defined as serum PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/ml after treatment, clinical metastasis or PCa-specific death.

5PFS defined as time to development of CRPC from initiation of ADT where progression to CRPC was defined as three consecutive monthly increases in serum PSA level against ADT according to Guan, 2016 [42].

6Biochemical recurrence defined as serum PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/ml after treatment.

7Biochemical recurrence defined as serum PSA ≥ 0.4 ng/ml after treatment.

8PFS defined as time to radiological/clinical progression from initiation of ARTA according to Sharova, 2021 [78].

Table 3. Allocation of 11 studies into 4 meta-analyses.

| Outcome | Handling of miR-21 data | No. of studies | Total no. of participants | Study IDs | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFS | Dichotomous | 4 | 838 | Amankwah, 2013 [31]; Leite, 2015 [60]; Li, 2012 [61]; Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68] | 1 |

| Continuous | 2 | 255 | Zedan, 2017 [85]; Zhao, 2019a [89] | 2 | |

| OS | Dichotomous | 4 | 307 | Lin, 2014 [64]; Lin, 2017 [65]; Sharova, 2021 [78]; Yang, 2016 [84] | 3 |

| PFS | Dichotomous | 2 | 116 | Guan, 2016 [42]; Sharova, 2021 [78] | 4 |

Eleven eligible studies were allocated into four separate meta-analyses according to outcomes and handlings of miR-21 data. Note: Sharova, 2021 [78] with two outcomes was allocated into Analyses 3 and 4.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

For population ‘P’, two studies from the same research group (Lin, 2014 [64] and Lin, 2017 [65]) included male patients diagnosed with CRPC that underwent docetaxel chemotherapy (a different set of patients was used for each study, therefore no double counting). Participants of Guan, 2016 [42] and Sharova, 2021 [78] received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and androgen receptor-targeted agents (ARTA) respectively; However, Sharova, 2021 [78] only included metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients. The rest of the studies (n=7) included male PCa patients that underwent resection surgeries such as radical prostatectomy (RP) and/or regional lymph node dissection. Not all studies reported the age range of participants, but it is apparent from available information that they were all around middle to old age groups at baseline (≥40 years).

For index prognostic factor ‘I’, Lin, 2014 [64]; Lin, 2017 [65]; Sharova, 2021 [78] and Yang, 2016 [84] measured circulating miR-21 in plasma, serum or peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples while the rest (n=7) measured tissue miR-21 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples; Li, 2012 [61] and Zedan, 2017 [85] measured miR-21 level by in situ hybridization (ISH) methods that are semi-quantitative, while the rest (n=9) used real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) techniques that are highly sensitive and specific [93].

For comparator prognostic factors ‘C’, the most frequently included ones were Gleason score/grade (GS/GG; n=10 except Lin, 2017 [65]), PSA (n=10 except Amankwah, 2013 [31]) and pathological/clinical stage (pT/cT; n=8 except Lin, 2014 [64], Lin, 2017 [65] and Sharova, 2021 [78]). These were followed by age (n=6), hemoglobin (n=3), surgical margin (n=3), lymph node metastasis (pN; n=2) and alkaline phosphatase (n=2). Body mass index (BMI), capsular invasion, visceral metastasis, perineural infiltration, tumor size, vascular infiltration, digital rectal examination (DRE), prostate volume, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and time to CRPC were each included once between six studies (Amankwah, 2013 [31]; Li, 2012 [61]; Lin, 2014 [64]; Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68]; Sharova, 2021 [78]; Zhao, 2019a [89]).

For outcomes of interest ‘O’, Lin, 2014 [64]; Lin, 2017 [65]; Sharova, 2021 [78] and Yang, 2016 [84] observed for overall survival (OS) defined as time from the date of treatment to the date of death; Guan, 2016 [42] and Sharova, 2021 [78] observed for progression-free survival (PFS), defined as time to development of CRPC from initiation of ADT by Guan, 2016 [42], and as time to radiological/clinical progression from initiation of ARTA by Sharova, 2021 [78]. The rest (n=6) observed for recurrence-free survival (RFS), generally defined as time from the date of treatment to the date of biochemical recurrence (BCR) with slight variations as indicated in Table 2 footnotes d, f and g. Latest follow-up times across studies ranged from 45 months (Lin, 2017 [65]) to 254 months (Amankwah, 2013 [31]), averaging up to 125 months (∼10 years). Not enough information was provided in Zedan, 2017 [85] to estimate the follow-up period.

Risk of bias within studies

Risk of bias within each eligible study was assessed using the QUIPS tool [26]; two independent judgments were made before reaching consensus. Final ratings of risk of bias within the 11 studies eligible for meta-analyses are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Risk of bias within studies assessed using QUIPS tool.

| Study ID | QUIPS domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Study participation | 2 Study attrition | 3 Prognostic factor measurement | 4 Outcome measurement | 5 Adjustment for covariates | 6 Statistical analysis and reporting | |

| Amankwah, 2013 [31] | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Guan, 2016 [42] | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | LOW |

| Leite, 2015 [60] | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH |

| Li, 2012 [61] | UNCLEAR | LOW | MODERATE | LOW | LOW | HIGH |

| Lin, 2014 [64] | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | MODERATE |

| Lin, 2017 [65] | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | MODERATE |

| Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68] | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | MODERATE |

| Sharova, 2021 [78] | MODERATE | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | LOW |

| Yang, 2016 [84] | UNCLEAR | MODERATE | LOW | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR |

| Zedan, 2017 [85] | MODERATE | LOW | MODERATE | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR |

| Zhao, 2019a [89] | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | LOW |

Overall, no eligible study achieved LOW risk of bias in all domains. Most concerns in risk of bias were around domain 5 and 6 mainly due to inadequate adjustment for predefined important prognostic factors and selective reporting. The lack of rationale for sample size appears to be a common problem across the majority of eligible studies.

Meta-analyses and sensitivity analyses

For all outcomes, results of each study eligible for meta-analyses are summarized in Table 5 (n=11). Six studies observed RFS, four observed OS, and two observed PFS. Effect estimates were pooled as HR (95% CI) based on fixed-effect inverse variance method. Statistical heterogeneity was determined by visual inspection of the forest plot, Chi2 test and I2 test (Chi2 P≤0.1 indicates significant heterogeneity; I2 < 30% denotes low/unimportant heterogeneity, 30–60% moderate heterogeneity, 50–90% substantial heterogeneity and 75–100% considerable heterogeneity).

Table 5. Summary of results of individual studies eligible for meta-analysis.

| Outcome (Analysis) | Study ID | Event /Total | Univariate analysis: Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Multivariate analysis: Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Covariates adjusted for* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFS (1) | Amankwah, 2013 [31] | 28/65 (43%) | (Cut-off = median; log-rank P<0.0001) KM plot favouring high miR-21 Estimated HR (95% CI)1: = 4.83 (2.26–10.35), P=0.00005 Inverse2: = 0.21 (0.10–0.44), P=0.00005 |

1.99 (0.70–5.64), P=0.20 Inverse2: = 0.50 (0.18–1.42), P=0.20 |

Age GS cT |

| Leite, 2015 [60] | 50/127 (39%) | (Cut-off = median; log-rank P=0.003) KM plot favoring low miR-21 Estimated HR (95% CI)1: = 2.32 (1.33–4.03), P=0.003 |

2.505 (1.356–4.629), P=0.003 |

GG PSA pT |

|

| Li, 2012 [61] | 116/168 (69%) | (Cut-off = median; log-rank P<0.001) KM plot favoring low miR-21 Estimated HR (95% CI)1: = 1.91 (1.33–2.75), P=0.0005 |

2.059 (1.075–3.944), P=0.029 | Age Capsular invasion GS pN PSA pT Surgical margin |

|

| Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68] | 170/478 (36%) | (Cut-off = 4th quartile; log-rank P=0.006) KM plot favoring low miR-21 Estimated HR (95% CI)1: = 1.65 (1.15–2.36), P=0.006 |

1.4 (1.0–1.9), P=0.089 | Apical PSM GG Non-apical PSM Perineural infiltration PSA pT Vascular infiltration |

|

| RFS (2) | Zedan, 2017 [85] | 19/49 (39%) | (Continuous miR-21) 1.231 (0.697–2.177), P=0.474 |

(No multivariate analysis data) | (N/A) |

| Zhao, 2019a [89] | 98/206 (48%) | (Continuous miR-21) 1.12 (1.01–1.24), P=0.049 |

(Continuous miR-21) 1.35 (0.86–2.12), P=0.188 |

15 other miRNAs of interest | |

| OS (3) | Lin, 2014 [64] | 55/97 (57%) | (High vs. low miR-21, cut-off = median) 2.3 (1.3–3.9), log-rank P=0.004 |

(No multivariate analysis data) | (N/A) |

| Lin, 2017 [65] | 53/87 (61%) | (High vs. low miR-21, cut-off = median) 1.2204 (0.7028–2.1192), P=0.477 |

(Continuous miR-21) 1.1488 (0.8849–1.4916), P=0.303 |

Alkaline phosphatase Hemoglobin PSA |

|

| Sharova, 2021 [78] | 13/31 (42%) | (Cut-off = 2.69; log-rank p = 0.0067) KM plot favoring high miR-21 5.2 (1.7–15.7), P=0.0191 Inverse2: = 0.192 (0.064–0.588), P=0.0191 |

5.8 (1.0–33.1), P=0.049 Inverse2: = 0.172 (0.03–1.0), P=0.049 |

Hemoglobin Time to CRPC |

|

| Yang, 2016 [84] | 42/92 (46%) | (Cut-off not stated; log-rank P<0.05) KM plot favoring low miR-21 Estimated HR (95% CI)1: = 2.02 (1.09–3.73), P=0.025 |

3.567 (1.287–9.882), P=0.014 | Age BCR Bone metastasis cT GS PSA |

|

| PFS (4) | Guan, 2016 [42] | 47/85 (55%) | (Cut-off = mean; log-rank P=0.006) KM plot favoring low miR-21 2.381 (1.250–4.537), P=0.008 |

1.985 (1.032–3.817), P=0.040 | cT |

| Sharova, 2021 [78] | 26/31 (84%) | (Cut-off = 2.69; log-rank P= =0.0002) KM plot favoring high miR-21 7.4 (2.6–21.2), P=0.0021 Inverse2: = 0.135 (0.047–0.385), P=0.0021 |

4.8 (1.3–17.8), P=0.019 Inverse2: = 0.208 (0.056–0.769), P=0.019 |

Hemoglobin Time to CRPC |

Abbreviations: BCR, biochemical recurrence; CI, confidence interval; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; cT, clinical tumor stage; GG, Gleason grade; GS, Gleason score; HR, hazard ratio; KM, Kaplan–Meier; N/A, not applicable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; pN, lymph node metastasis; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSM, positive surgical margins; pT, pathological tumor stage; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

GS/GG and pT/cT were predefined as important prognostic factors that should be adjusted for in multivariate analysis.

1Unadjusted HR (95% CI) was not reported; hence it was estimated using an Excel calculator [94].

Analysis 1: Recurrence-free survival; dichotomous miR-21 data (n=4)

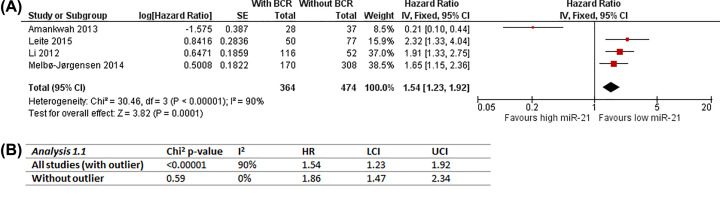

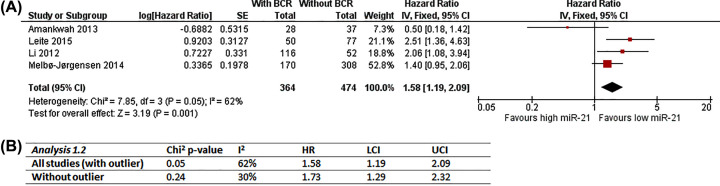

This analysis includes Amankwah, 2013 [31]; Leite, 2015 [60]; Leite, 2012 [61] and Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68] as they have observed RFS as outcome and dichotomised tissue miR-21 expression data into high and low groups (median as cut-off for Amankwah, 2013 [31]; Leite, 2015 [60] and Li, 2012 [61]; 4th quartile for Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68]). Unadjusted and adjusted effect estimates of all four studies were combined in Analysis 1.1 (Figure 2A) and Analysis 1.2 (Figure 3A) respectively for comparison to examine the effect of heterogeneity caused by differences in covariate adjustment. Overall number of participants is 838 (364 with BCR; 474 without BCR).

Figure 2. Analysis 1.1: Meta-analysis of dichotomous miR-21 expression with recurrence-free survival (unadjusted).

(A) Unadjusted results and forest plot, RevMan5.4 snapshot. (B) Sensitivity analysis of impact of outlier (Amankwah, 2013 [31]); BCR, biochemical recurrence; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IV, inverse variance; LCI, lower confidence interval; SE, standard error; UCI, upper confidence interval.

Figure 3. Analysis 1.2: Meta-analysis of dichotomous miR-21 expression with recurrence-free survival (adjusted).

(A) Adjusted results and forest plot, RevMan5.4 snapshot. (B) Sensitivity analysis of impact of outlier (Amankwah, 2013 [31]); BCR, biochemical recurrence; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IV, inverse variance; LCI, lower confidence interval; SE, standard error; UCI, upper confidence interval.

The overall effect of unadjusted estimates, as shown in the forest plot of Analysis 1.1, favors low miR-21, suggesting high miR-21 expression is associated with higher risk of BCR (HR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.23–1.92). Statistical heterogeneity tests indicate significantly considerable heterogeneity (Chi2 P<0.00001; I2 = 90%), most likely caused by the presence of an outlier (Amankwah, 2013 [31]) which showed an opposite direction of effect estimate to the other studies. To probe this further, the impact of the outlier on this meta-analysis was assessed by sensitivity analysis. Results of sensitivity analysis (Figure 2B) confirmed the data from Amankwah, 2013 [31] as the source of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0% without outlier). However, the inclusion of the outlier did not change the effect estimate significantly; therefore, the results of Analysis 1.1 are still valid.

The overall effect of adjusted estimates (Analysis 1.2) is very close to that of unadjusted estimates (Analysis 1.1) supporting the same conclusion, i.e., it favors low miR-21, suggesting high miR-21 expression is associated with higher risk of BCR (HR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.19–2.09; Figure 3A). However, different from Analysis 1.1, Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014 [68] now occupied over half of the overall weight (52.8%) with Li, 2012 [61] weighing only 18.8%. Amankwah, 2013 [31] still appears to be outlying, and statistical heterogeneity tests also indicate significantly substantial heterogeneity (Chi2 P=0.05; I2 = 62%). Again, sensitivity analysis repeating Analysis 1.2 without Amankwah, 2013 [31] reduced statistical heterogeneity to insignificant and low/unimportant (I2 = 30%; Figure 3B), verifying the outlying estimate as the source of statistical heterogeneity. The slight difference in overall effect reveals that the inclusion of the outlier has limited impact, and that the results of Analysis 1.2 are robust.

Comparing the two analyses, covariate adjustment in Analysis 1.2 had brought Amankwah, 2013 [31] closer to the other studies with the upper CI arm crossing the line of no effect and overlapping with others’ that might explain the lower statistical heterogeneity indicated by I2 values compared to Analysis 1.1 (62% vs. 90%). However, eliminating the effect of outlier, higher I2 value of adjusted estimates compared with unadjusted (30% vs. 0%) implies that differences in covariate adjustment might have introduced some heterogeneity, though low and insignificant.

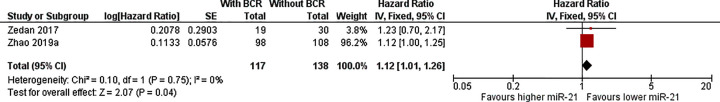

Analysis 2: Recurrence-free survival; continuous miR-21 data (n=2)

This analysis includes Zedan, 2017 [85] and Zhao, 2019a [89] as both have observed RFS as outcome against continuous miR-21 expression in tissue samples. Only unadjusted effect estimates were combined in Analysis 2 (Figure 4) because of lack of multivariate analysis data for Zedan, 2017 [85]. Overall number of participants is 255 (117 with BCR; 138 without BCR).

Figure 4. Analysis 2: Meta-analysis of continuous miR-21 expression with recurrence-free survival.

Unadjusted results and forest plot, RevMan5.4 snapshot; BCR, biochemical recurrence; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

The overall effect estimate (HR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.01–1.26) favors lower miR-21, indicating that higher miR-21 expression is associated with higher risk of BCR. The overall effect in the forest plot showed high precision from the tight CI and statistical heterogeneity is very low (Chi2 P=0.75; I2 = 0%). However, the data points are very close to the line of no effect with the lower CI of Zedan, 2017 [85] across. The overall weight is dominated by Zhao, 2019a [89] (96.2%) between only two studies.

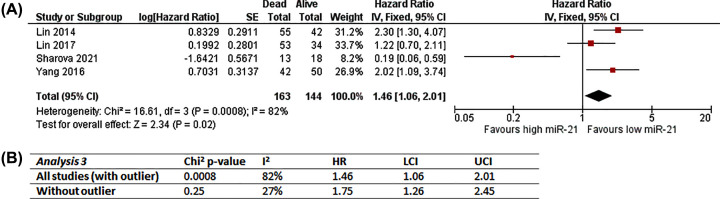

Analysis 3: Overall survival; dichotomous miR-21 data (n=4)

This analysis included Lin, 2014 [64]; Lin, 2017 [65]; Sharova, 2021 [78] and Yang, 2016 [84] as they are similar in outcome observed (OS), handling of miR-21 data (dichotomised) and source of miR-21 (circulating samples). Only unadjusted effect estimates were combined in Analysis 3 (Figure 5A) because of lack of multivariate analysis data for Lin, 2014 [64] and differences in covariate adjustment and handling of miR-21 data in multivariate analysis for Lin, 2017 [65]. Overall number of participants is 307 (163 dead; 144 alive).

Figure 5. Analysis 3: Meta-analysis of miR-21 expression with overall survival.

(A) Unadjusted results and forest plot, RevMan5.4 snapshot. (B) Sensitivity analysis of impact of outlier (Sharova, 2021 [78]); CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IV, inverse variance; LCI, lower confidence interval; SE, standard error; UCI, upper confidence interval.

The overall effect in Analysis 3 favors low miR-21, suggesting high miR-21 expression is associated with higher risk of death (HR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.06–2.01; Figure 5A). Sharova, 2021 [78] was outlying in the opposite direction to the rest and mostly likely have caused the considerable heterogeneity (Chi2 P=0.0008; I2 = 82%); Therefore the impact of including Sharova, 2021 [78] in Analysis 3 was examined in sensitivity analysis (Figure 5B). Sensitivity analysis repeating Analysis 3 without Sharova2021 [78] significantly reduced heterogeneity to low/unimportant level (Chi2 P=0.25; I2 = 27%; Figure 5B), confirming an outlier as the main source of heterogeneity, and that had brought the overall effect estimate closer to the line of no effect.

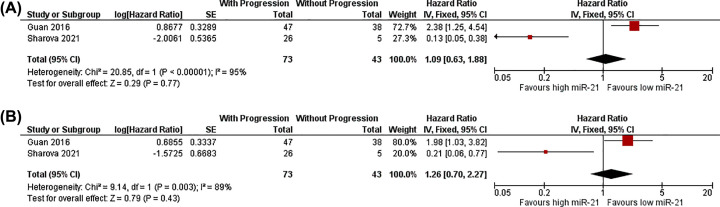

Analysis 4: Progress-free survival; dichotomous miR-21 data (n=2)

Analysis 4 included Guan, 2016 [42] and Sharova, 2021 [78] because both studies observed PFS as outcome. Overall number of participants is 116 (73 with progression; 43 without progression). Figure 6A,B showed meta-analysis results along with forest plots of combined unadjusted and adjusted effect estimates respectively (Analyses 4.1 and 4.2). Neither analysis reached a significant overall effect (CIs crossing line of no effect), most likely since only two studies with opposite effect estimates were available, which also contributed to considerable heterogeneities (Chi2<0.1; I2>80%). Therefore, no meaningful conclusion could be drawn from Analysis 4.

Figure 6. Meta-analyses of miR-21 expression with progression-free survival.

(A) Analysis 4.1: Unadjusted results and forest plot, RevMan5.4 snapshot. (B) Analysis 4.2: Adjusted results and forest plot, RevMan5.4 snapshot; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Qualitative summary and associations

Most of the 64 studies included in this review compared the association of miR-21 with commonly used clinicopathological prognostic factors (Table 6). These included Gleason score/grade (n=28), pathological/clinical stage (n=18), serum PSA level (n=18), risk stratification (n=12) and age at diagnosis (n=9). Association of miR-21 expression with recurrence (n=19) and metastasis (n=14) were also examined in many included studies. A few studies have compared miR-21 levels in/with prostate volume (n=4), chem-response (n=3), digital rectal examination (DRE) result (n=3), ethnicity (n=2) and surgical margin (n=2). Other comparisons made include genitourinary radiotoxicity (Kopcalic, 2019 [53]), neuroendocrine-like versus Adeno PCa (Ostano, 2020 [71]), follow-up time, family history (Shen, 2012 [79]) and reclassification (Zhao, 2019b [90]).

Table 6. Summary of association results of included studies.

| Association result | Gleason (n=28)* | Stage (n=18) | PSA (n=18)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P<0.05 | Pos | T | Arisan, 2020; Guan, 2016; Li, 2012; Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014; Zhao, 2019a | Li, 2012; Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014; Reis, 2012; Zhao, 2019a | ||

| C | Al-Qatati, 2017; Gurbuz, 2020; Ibrahim, 2019a; Ibrahim, 2019b; Ju, 2019; Yang, 2016 | Al-Qatati, 2017; Gurbuz, 2020; Huang, 2015b; Ibrahim, 2019a; Ibrahim, 2019b; Ju, 2019; Stuopelyte, 2016; Yang, 2016 | Al-Qatati, 2017; Gurbuz, 2020; Ibrahim, 2019b | |||

| U | Samaan, 2014 | |||||

| Neg | T | Ren, 2014 | Ren, 2014 | |||

| P >0.05 | Pos | T | Katz, 2014; Kurul, 2019; Lichner, 2015; Reis, 2012; Zedan, 2017; Zedan, 2018 | Zedan, 2017 | Li, 2012; Reis, 2012; Zedan, 2018; Zhao, 2019a | |

| C | Shen, 2012 | Shen, 2012 Zedan, 2019 |

Ju, 2019; Shen, 2012; Zedan, 2018; Zedan, 2019 | |||

| Neg | T | Kristensen, 2016** | Katz, 2014 | Zedan, 2017 | ||

| C | Kotb, 2014; Zedan, 2018; Zedan, 2019 | Sharova, 2021; Yang, 2016; Zhao, 2019b | ||||

| No diff | T | Amankwah, 2013 | Guan, 2016; Katz, 2014 | |||

| C | Farran, 2018; Foj, 2017; Stuopelyte, 2016 | |||||

|

No

P-value |

Pos | T | Hart, 2014 | |||

| No corr | C | Agaoglu, 2011 | ||||

| Association result | Recurrence (n=19) | Metastasis (n=14) | Risk (n=12) | Age (n=9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P<0.05 | Pos | T | Leite, 2015; Li, 2012; Melbø-Jørgensen, 2014; Reis, 2012 | Guan, 2016; Li, 2012 | Zhu, 2019 | |

| C | Huang, 2015b; Ju, 2019; Yang, 2016 | Agaoglu, 2011; Brase, 2011; Huang, 2015b; Ibrahim, 2019a; Ibrahim, 2019b; Watahiki, 2013; Yang, 2016; Ju, 2019 | Foj, 2017; Ju, 2019; Shen, 2012 | Zedan, 2019 | ||

| Neg | T | Suer, 2019**; Amankwah, 2013 | Ren, 2014 | Ren, 2014 | ||

| C | Danarto, 2020 | |||||

| P>0.05 | Pos | T | Kurul, 2019; Leite, 2011; Ren, 2014 | Katz, 2014; Leite, 2013; Zedan, 2017 | ||

| C | Stuopelyte, 2016 | Al-Qatati, 2017; Hoey, 2019; Sapre, 2014; Zedan, 2019 | Huang, 2015b; Yang, 2016 | |||

| Neg | T | Katz, 2014 | Leite, 2011 | Lichner, 2013 | Zhao, 2019a; Li, 2012 | |

| C | Selth, 2013; Shen, 2012 | Shen, 2012; Zhao, 2019b | ||||

| No diff/corr | T | Kristensen, 2016**; Zheng, 2014 | Guan, 2016 | |||

| C | Singh, 2014 | |||||

|

No

P-value |

Pos | T | Bonci, 2016 | |||

Most of the 64 studies included in this review compared the association of miR-21 with commonly used clinicopathological prognostic factors (Gleason score/grade; pathological/clinical stage; serum PSA level; risk stratification; age at diagnosis), as well as recurrence and metastasis.

Study IDs in bold were eligible for meta-analysis (n=11).

Abbreviations: C, circulating miR-21; corr, correlation; diff, difference; Neg, negative association; Pos, positive association; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; T, tissue miR-21; U, unknown miR-21 source

Zedan, 2018 [86] was counted twice as both tissue and plasma miR-21 expressions were measured.

3p strand of miR-21 was measured.

Results were grouped according to statistical significance (P<0.05/P>0.05), association direction (positive/negative) and sample source (tissue/circulating). Association measures varied between studies, these include fold change (FC), mean difference and correlation, meaning it was impractical to summarize findings according to comparison methods. Therefore, findings were summarised according to association directions. When higher miR-21 expression was associated with higher degree/presence of the comparators it was indicated as positive; when it was associated with lower degree/absence of the comparators it was negative.

Additional figures demonstrating association results can be found in Supplementary Figure SF 1A–G. Twelve out of 28 studies (43%) that compared miR-21 levels in different Gleason scores/grades found significant positive association of miR-21 levels from tissue and circulating samples. Twelve out of 18 studies (67%) that compared miR-21 levels in different pathological/clinical stages found significant positive association of miR-21 mostly from circulating samples as well as tissue. In contrast, only three studies reported significant positive association in circulating miR-21 and serum PSA. Seven out of 19 studies (37%) found significant positive association between tissue/circulating miR-21 and biochemical recurrence, defined generally as biochemical recurrence determined by rise in serum PSA ≥ 0.2–0.4 ng/ml after treatment. Ten out of 14 studies (71%) that compared miR-21 levels in samples of metastatic versus localized PCa patients found significant positive association between metastatic PCa and miR-21 mostly in circulating samples (n=8; tissue n=2). 11 out of 12 studies (92%) that examined risk stratification reported positive association of higher risk with elevated miR-21 expression, although only 4 (33%) of these were found to be statistically significant.

Certainty of evidence – GRADE

Publication bias was not assessed due to low number of studies eligible for each analysis. No analysis was rated up for large effect, dose response or plausible confounding. Table 7 presented judgments of rate-downs and overall certainties of each analysis. Overall certainty is MODERATE for Analysis 1.2; LOW for Analyses 1.1 and 2; VERY LOW for Analyses 3, 4.1 and 4.2. See Supplementary Table ST 7 for full rationales for rating down certainty of evidence.

Table 7. Certainty of evidence in each analysis (GRADE).

| Analysis | Outcome | Pooled result HR (95% CI) | No. of participants | Certainty rate-downs | Overall certainty5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | RFS1,3 | 1.54 (1.23–1.92) | 838 (4 studies) | - RoB: High RoB in 3 studies - Imprecision: Estimated HR in all studies |

LOW |

| 1.2 | RFS2,3 | 1.58 (1.19–2.09) | 838 (4 studies) | - RoB: High RoB in 3 studies | MODERATE |

| 2 | RFS1,4 | 1.12 (1.01–1.26) | 255(2 studies) | - RoB: Unadjusted HR & high RoB in 1 study - Imprecision: CI close to HR 1 |

LOW |

| 3 | OS1,3 | 1.46 (1.06–2.01) | 307 (4 studies) | - RoB: Unadjusted HR & high RoB in 3 studies - Indirectness: Lin 2014 & Lin 2017 recruited CRPC patients to address chemo-response - Imprecision: Estimated HR in 1 study; CI close to HR 1 |

VERY LOW |

| 4.1 | PFS1,3 | 1.09 (0.63–1.88) | 116 (2 studies) | - RoB: High RoB in both studies - Inconsistency: Opposite direction results - Imprecision: Wide CI crossing HR 1 |

VERY LOW |

| 4.2 | PFS2,3 | 1.26 (0.70–2.27) | 116 (2 studies) | - RoB: High RoB in both studies - Inconsistency: Opposite direction results - Imprecision: Wide CI crossing HR 1 |

VERY LOW |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RoB, risk of bias.

1Unadjusted effect estimates.

2Adjusted effect estimates.

3Dichotomised miR-21 levels.

4Continuous miR-21 levels.

5HIGH: We are very confident that the variation in risk associated with miR-21 expression lies close to that of the estimate; MODERATE: We are moderately confident that the variation in risk associated with miR-21 expression is likely to be close to the estimate, but substantial difference is possible; LOW: We have limited certainty in the estimate, the variation in risk associated with miR-21 expression may be substantially different from the estimate; VERY LOW: We have very little certainty in the estimate, the variation in risk associated with miR-21 expression is likely to be substantially different from the estimate (GRADE [28]).

Discussion

In this report, we have performed the first systematic review and meta-analysis of miR-21 as a prognostic factor in PCa. miR-21 is one of the most studied miRNAs in cancer and has been shown to play a role in many different cellular mechanisms which can contribute to cancer progression, including PCa [95]. Although miR-21 targets many genes and thus regulates many genetic pathways, it appears to act in a primarily oncogenic fashion with many studies reporting elevated levels in samples taken from cancer patients. Despite this body of evidence, there is still doubt about whether it may be a useful biomarker for cancer prognosis, so robust analyses of existing studies are needed to determine its value for clinical application and to inform the optimal design of future studies.

The pooled results of all meta-analyses reported here supported an association between high miR-21 expression and poor prognosis in PCa. Regarding RFS, Analysis 1.2 estimated a 58% increased risk of BCR for high baseline expression of tissue miR-21 (HR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.19–2.09) with MODERATE certainty of evidence. For OS, Analysis 3 estimated a 75% increased risk of death for high baseline expression of circulating miR-21 with VERY LOW certainty of evidence (HR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.26–2.45). No meaningful conclusion could be drawn for PFS in Analysis 4 due to considerable heterogeneity between only two eligible studies. The heterogeneity could be attributed to differences in population, miR-21 source and PFS definition. Guan, 2016 [42] recruited pathologically confirmed PCa patients while Sharova, 2021 [78] only included mCRPC patients; Guan, 2016 [42] detected miR-21 from FFPE tissue samples while Sharova, 2021 [78] examined it in plasma samples; Guan, 2016 [42] defined PFS as time to development of CRPC while Sharova, 2021 [78] defined it as time to radiological/clinical progression. Analysis 4 demonstrated the importance of only combining results of similar studies as a basic principle of meta-analysis. The limited certainty in OS result and lack of similar studies in PFS for a meaningful meta-analysis indicated that more high-quality prognostic studies are needed for OS and PFS. Nevertheless, our systematic approach and meta-analyses found consistent evidence that miR-21 may have prognostic value in PCa. These data suggest miR-21 can be put forward as a strong candidate for the prognosis of the disease, although further work is clearly needed to prove its value more conclusively as a biomarker.

Our results agreed with systematic reviews in other cancers such as non-small cell lung, pancreatic and colorectal cancers [96–98]. These suggested high tissue miR-21 as an unfavourable prognostic biomarker. Circulating miR-21 overexpression was also associated with poor prognosis in digestive system and breast cancers [18,19,99]. This is not unexpected, given that it is generally agreed to act as an oncogene, but this understanding of its functional role in the cell can only be translated into medical application when the literature available is subject to methodical evaluation in studies such as these.

However, it is worth noting that the authors of the papers subject to meta-analysis here all indicated limitations with their studies. We recorded this as part of our data gathering process and further probed it through our quality assessment of individual studies. Pooled evidence by QUIPS and GRADE methodologies revealed sources of risk of bias and down-rate of certainty of evidence. In several studies, selective reporting and failure to adjust for the core set of covariates increased risk of bias and imprecision, thus decreased certainty of evidence. Furthermore, publication bias could not be properly assessed due to inadequate number of studies included in individual analysis. This was mainly due to high heterogeneity across studies, such as differences in outcome, handling of miR-21 data and sample source. The limited similarities meant that eligible studies had to be split into separate small analyses, therefore reducing the impact of meta-analyses. It was unfortunate that so few of the published studies met the required criteria for inclusion in meta-analysis, which limits the strength of the analyses and our subsequent ability to draw firm conclusions. Although the very nature of a properly conducted meta-analysis is to be robust and consistent in the application of the methodology, limitations in selected studies are inevitably reflected in the limitations of the subsequent meta-analyses, since the patient numbers and/or measured parameters are less than ideal. Perhaps that is to be expected since miRNAs as biomarkers is a relatively recent field of research, but it is clear that a lack of standardised approach to these type of biomarker studies makes it difficult to evaluate the clinical usefulness of miRNAs as prognostic biomarkers. Therefore, for any researchers carrying out future cancer prognostic studies of this type, it is highly recommended that they adhere to the Reporting Recommendations for Tumour Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) guidelines for proper study design, conduct, analysis and reporting [100]. This will reduce risk of bias and heterogeneity across studies to generate higher quality evidence and more opportunity for comparison in meta-analyses like the ones presented here. Evidently, Zhao, 2019a [89] was the only included study that followed the guidelines and achieved LOW risk of bias in most QUIPS domains.

Although several of the full-text studies reviewed were not eligible for meta-analysis, they nevertheless contained useful data about the association of miR-21 with PCa, which is important to discuss since it can inform future study design. Overall, several studies in this review supported the hypothesis that there is a significant positive association between miR-21 expression and various clinical measurements of PCa progression, such as stage, Gleason score, risk groups, metastasis and recurrence. Notably, very few studies found a significant association between miR-21 expression and serum PSA level or age at diagnosis.

However, for clinical application of miR-21 analysis, several barriers must be overcome. A standardized method for measuring miR-21 must be decided upon. RT-qPCR, as used in many of the studies reported here, would seem the most appropriate technique at present in terms of sensitivity and applicability. Nevertheless, agreement is needed on common normalisation approaches and comparable internal controls, such as reference genes. Even with these measures in place, a consensus would then be needed on an appropriate cut-off value for prognostic outcome, which was very variable in the studies evaluated here. Another important consideration is that the correct miR-21 strand is being measured, since there is no guarantee that expression of miR-21-3p and miR-21-5p will be similar. The majority of the studies in this review did not specify miR-21 strand, which is also another reason to be cautious about the interpretation of the results presented here.

Even if standardized approaches meant RT-qPCR was accepted as suitably sensitive and accurate method, the sample type in which to measure the miR-21 target is a further complication. Among 64 studies included in this review, 32 measured miR-21 levels in circulating samples, including plasma, serum, PBMC, urine, exosome and whole blood; 30 measured miR-21 levels in tissue samples; Zedan, 2018 [86] measured from both sample types; and Samaan, 2014 [74] did not clearly state the sample source. Zedan, 2018 [86] found significant correlation of miR-21 levels between matched tissue and plasma samples from 25 healthy patients (r=0.58, P<0.01) but not in 21 PCa patients (P=0.42). It is not certain that tissue and biofluid levels of miR-21 will be directly comparable, and it is also possible that different outcomes might be better predicted by miR-21 expression in one particular sample type. Thus, further inter- and intra-individual analyses would be needed to determine the relative value of these different sample types. It is therefore clear that for miR-21, or any other miRNA, to gain clinical acceptance as disease biomarker, it requires well-designed, prospective clinical studies to validate the findings reported here. Ideally, these studies should utilise the same PICOT criteria, ensuring common outcomes and measurements can then be compared between studies and across different research centres.

Nevertheless, even though there are not yet enough well-designed studies to conclusively prove biomarker potential of miRNAs, it does appear increasingly likely that they will be used in future as non-invasive, liquid biomarkers for cancer and other diseases [101,102]. With this in mind, miR-21 is a very attractive candidate to profile, since it is abundantly expressed in both tissue and biofluids, making it easy to measure [14,103]. In relation to PCa specifically, its involvement in promoting cancer growth, and related roles in important pathological changes, such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), is now well established [14,104], so there is a strong biological rationale for measuring its expression as a marker of disease progression. It is worth remembering however that miRNAs often work synergistically as a regulatory network for gene expression, so the involvement of miR-21 with other miRNAs should be considered. For instance, while this paper was being prepared, another systematic review and meta-analysis was published which reported the prognostic significance of 15 microRNAs related to metastasis and EMT process in PCa patients [105]. Surprisingly, miR-21 was not included among them, but the authors did acknowledge the link between their selected miRNAs and miR-21 in their discussion, and they concluded that a miRNA panel of biomarkers would be optimal to determine progression risk. Similarly, another recent paper used meta-analysis methods to identify miR-21 as one of several miRNAs which could predict response to ADT [106]. Profiling different miRNAs in parallel makes sense, since many miRNAs are known to be involved in PCa development [101,103]. It is also unlikely that miR-21 (or any other miRNA) as a single biomarker would be sufficient to accurately predict any given patient outcome. Therefore, the ability to measure expression levels of other miRNAs, or other genetic parameters, in combination with miR-21 should be built into the design of future studies investigating its prognostic value in cancer A multivariate profiling approach to PCa prognosis, which includes measurement of miR-21, would be a sensible approach to take.

Conclusion

Meta-analyses of 11 studies in this report showed that high miR-21 expression was associated with poor prognosis in PCa. Qualitative summary of all 64 studies also found positive association of miR-21 expression with various prognostic factors for PCa. These findings corroborate data from other systematic reviews which have shown similar findings for miR-21 in various cancers. However, further research is needed, including more high-quality investigations that follow standardized guidelines for study design. With continued effort, miR-21 could prove to be a clinically useful prognostic biomarker in prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Joan Atkinson, Ulster University, for reviewing our search strategy; and Dr Marialena Trivella, University of Oxford, for providing statistical advice and an Excel calculator for the estimation of Hazard ratios.

Abbreviations

- BCR

biochemical recurrence

- CI

confidence interval

- CRPC

castration-resistant prostate cancer

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- FC

fold change

- HR

hazard ratio

- IV

inverse variance

- LCI

lower confidence interval

- OS

overall survival

- RFS

recurrence-free survival

- RoB

risk of bias

- UCI

upper confidence interval

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed in the present study are available from the published papers that have been cited in this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

Department for the Economy (DfE), Northern Ireland.

CRediT Author Contribution

M.Y. Cynthia Stafford: Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Colin E. Willoughby: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. Colum P. Walsh: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. Declan J. McKenna: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Project administration.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A. and Jemal A. (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahdy A., Patil R. and Parajuli S. (2019) Biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer and temporal association to bone metastasis. Am. J. Case Rep. 20, 1521–1525 10.12659/AJCR.918569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suárez C., Morales-Barrera R., Ramos V., Núñez I., Valverde C., Planas J.et al. (2013) Role of immunotherapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). BJU Int. 113, 367 10.1111/bju.12110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prostate Cancer UK (2019) What is my outlook? Available at: https://prostatecanceruk.org/prostate-information/just-diagnosed/what-is-my-outlook Accessed May 4, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichner Z., Ding Q., Samaan S., Saleh C., Nasser A., Al-Haddad S.et al. (2015) miRNAs dysregulated in association with Gleason grade regulate extracellular matrix, cytoskeleton and androgen receptor pathways. J. Pathol. 237, 226 10.1002/path.4568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordetsky J. and Epstein J. (2016) Grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma: current state and prognostic implications. Diagn. Pathol. 11, 25 10.1186/s13000-016-0478-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng L., Montironi R., Bostwick D.G., Lopez‐Beltran A. and Berney D.M. (2012) Staging of prostate cancer. Histopathology 60, 87–117 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasinska A., Jaszczynski J., Rychlik U., Łuczynska E., Pogodzinski M. and Palaczynski M. (2020) Prognostic significance of serum PSA level and telomerase, VEGF and GLUT-1 protein expression for the biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 26, 1049–1056 10.1007/s12253-019-00659-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertoli G., Cava C. and Castiglioni I. (2016) MicroRNAs as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and theranostics in prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 421 10.3390/ijms17030421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalanotto C., Cogoni C. and Zardo G. (2016) MicroRNA in control of gene expression: an overview of nuclear functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1712 10.3390/ijms17101712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali Syeda Z., Langden S.S.S., Munkhzul C., Lee M. and Song S.J. (2020) Regulatory mechanism of MicroRNA expression in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1723 10.3390/ijms21051723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabris L., Ceder Y., Chinnaiyan A.M., Jenster G.W., Sorensen K.D., Tomlins S.et al. (2016) The potential of MicroRNAs as prostate cancer biomarkers. Eur. Urol. 70, 312–322 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuopelyte K., Daniunaite K., Bakavicius A., Lazutka J.R., Jankevicius F. and Jarmalaite S. (2016) The utility of urine-circulating miRNAs for detection of prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 115, 707–715 10.1038/bjc.2016.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bautista-Sánchez D., Arriaga-Canon C., Pedroza-Torres A., De La Rosa-Velázquez I.A., González-Barrios R., Contreras-Espinosa L.et al. (2020) The promising role of miR-21 as a cancer biomarker and its importance in RNA-based therapeutics. Mol. Ther. Nucl. Acids 20, 409–420 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W., Li J., Zhu W., Gao C., Jiang R., Li W.et al. (2014) MicroRNA-21 and the clinical outcomes of various carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 14, 819 10.1186/1471-2407-14-819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y., Gao X., Wei F., Zhang X., Yu J., Zhao H.et al. (2014) Diagnostic and prognostic value of circulating miR-21 for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene 533, 389–397 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu X., Han Y., Wu Y., Zhu X., Lu X., Mao F.et al. (2011) Prognostic role of microRNA-21 in various carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 41, 1245–1253 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guraya S. (2018) Prognostic significance of circulating microRNA-21 expression in esophageal, pancreatic and colorectal cancers; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 60, 41–47 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jinling W., Sijing S., Jie Z. and Guinian W. (2017) Prognostic value of circulating microRNA-21 for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 45, 1–6 10.1080/21691401.2016.1216856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z., Zhan Y., Chi J., Guo S., Zhong X., He A.et al. (2018) Using microRNAs as novel predictors of urologic cancer survival: an integrated analysis. EBioMedicine 34, 94–107 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M.et al. (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 350, g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley R.D., Moons K.G.M., Snell K.I.E., Ensor J., Hooft L., Altman D.G.et al. (2019) A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies. BMJ 364, k4597 10.1136/bmj.k4597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. and Altman D.G. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kempf E., de Beyer J.A., Cook J., Holmes J., Mohammed S., Nguyên T.L.et al. (2018) Overinterpretation and misreporting of prognostic factor studies in oncology: a systematic review. Br. J. Cancer 119, 1288–1296 10.1038/s41416-018-0305-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z. and Elmagarmid A. (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5, 210 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden J.A., van der W., Danielle A., Cartwright J.L., Côté P. and Bombardier C. (2013) Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 158, 280–286 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Cochrane Collaboration (2020) Review Manager (RevMan) 5.4 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foroutan F., Guyatt G., Zuk V., Vandvik P.O., Alba A.C., Mustafa R.et al. (2020) GRADE Guidelines 28: Use of GRADE for the assessment of evidence about prognostic factors: rating certainty in identification of groups of patients with different absolute risks. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 121, 62–70 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agaoglu F.Y., Kovancilar M., Dizdar Y., Darendeliler E., Holdenrieder S., Dalay N.et al. (2011) Investigation of miR-21 miR-141 and miR-221 in blood circulation of patients with prostate cancer. Tumor Biol. 32, 583–588 10.1007/s13277-011-0154-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al‐Qatati A., Akrong C., Stevic I., Pantel K., Awe J., Saranchuk J.et al. (2017) Plasma microRNA signature is associated with risk stratification in prostate cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 141, 1231–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amankwah E.K., Anegbe E., Park H., Pow-Sang J., Hakam A. and Park J.Y. (2013) miR-21 miR-221 and miR-222 expression and prostate cancer recurrence among obese and non-obese cases. Asian J. Androl. 15, 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arisan E.D., Rencuzogullari O., Freitas I.L., Radzali S., Keskin B., Kothari A.et al. (2020) Upregulated Wnt-11 and miR-21 expression trigger epithelial mesenchymal transition in aggressive prostate cancer cells. Biology 9, 52 10.3390/biology9030052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell E.H., Kirste S., Fleming J.L., Stegmaier P., Drendel V., Mo X.et al. (2015) A novel miRNA-based predictive model for biochemical failure following post-prostatectomy salvage radiation therapy. PLoS ONE 10, e0118745 10.1371/journal.pone.0118745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonci D., Coppola V., Patrizii M., Addario A., Cannistraci A., Francescangeli F.et al. (2016) A microRNA code for prostate cancer metastasis. Oncogene 35, 1180–1192 10.1038/onc.2015.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brase J.C., Johannes M., Schlomm T., Fälth M., Haese A., Steuber T.et al. (2011) Circulating miRNAs are correlated with tumor progression in prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 128, 608–616 10.1002/ijc.25376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant R., Pawlowski T., Catto J.W.F., Marsden G., Vessella R.L., Rhees B.et al. (2012) Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 106, 768–774 10.1038/bjc.2011.595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danarto R., Astuti I., Umbas R. and Haryana S.M. (2020) Urine miR-21-5p and miR-200c-3p as potential non-invasive biomarkers in patients with prostate cancer. Turk J. Urol. 46, 26 10.5152/tud.2019.19163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Endzeliņš E., Berger A., Melne V., Bajo-Santos C., Soboļevska K., Ābols A.et al. (2017) Detection of circulating miRNAs: comparative analysis of extracellular vesicle-incorporated miRNAs and cell-free miRNAs in whole plasma of prostate cancer patients. BMC Cancer 17, 1–13 10.1186/s12885-017-3737-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farran B., Dyson G., Craig D., Dombkowski A., Beebe-Dimmer J.L., Powell I.J.et al. (2018) A study of circulating microRNAs identifies a new potential biomarker panel to distinguish aggressive prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis 39, 556–561 10.1093/carcin/bgy025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fendler A., Jung M., Stephan C., Honey R.J., Stewart R.J., Pace K.T.et al. (2011) miRNAs can predict prostate cancer biochemical relapse and are involved in tumor progression. Int. J. Oncol. 39, 1183–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foj L., Ferrer F., Serra M., Arévalo A., Gavagnach M., Giménez N.et al. (2017) Exosomal and non‐exosomal urinary miRNAs in prostate cancer detection and prognosis. Prostate 77, 573–583 10.1002/pros.23295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan Y., Wu Y., Liu Y., Ni J. and Nong S. (2016) Association of microRNA‐21 expression with clinicopathological characteristics and the risk of progression in advanced prostate cancer patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate 76, 986–993 10.1002/pros.23187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gurbuz V., Kiliccioglu I., Dikmen A.U., Bilen C.Y., Sozen S. and Konac E. (2020) Comparative analysis of epi-miRNA expression levels in local/locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer patients. Gene 758, 144963 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hart M., Nolte E., Wach S., Szczyrba J., Taubert H., Rau T.T.et al. (2014) Comparative microRNA profiling of prostate carcinomas with increasing tumor stage by deep sequencing. Mol. Cancer Res. 12, 250–263 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoey C., Ahmed M., Ghiam A.F., Vesprini D., Huang X., Commisso K.et al. (2019) Circulating miRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers to predict aggressive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J. Translat. Med. 17, 1–11 10.1186/s12967-019-1920-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang X., Yuan T., Liang M., Du M., Xia S., Dittmar R.et al. (2015) Exosomal miR-1290 and miR-375 as prognostic markers in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 67, 33–41 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang W., Kang X.L., Cen S., Wang Y. and Chen X. (2015) High-level expression of microRNA-21 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is a diagnostic and prognostic marker in prostate cancer. Genet. Test Mol. Biomark. 19, 469–475 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibrahim N.H., Abdellateif M.S., Thabet G., Kassem S.H., El-Salam M.A., El-Leithy A.A.et al. (2019) Combining PHI and miRNAs as biomarkers in prostate cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Clin. Lab. 65, 10 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.181213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ibrahim N.H., Abdellateif M.S., Kassem S.H.A., Abd El Salam M.A. and El Gammal M.M. (2019) Diagnostic significance of miR‐21 miR‐141 miR‐18a and miR‐221 as novel biomarkers in prostate cancer among Egyptian patients. Andrologia 51, e13384 10.1111/and.13384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ju G., Lian J., Wang Z., Cao W., Lin J., Li Y.et al. (2019) Correlation between miRNA-21 expression and diagnosis metastasis and prognosis of prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 12, 8172–8180 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katz B., Reis S.T., Viana N.I., Morais D.R., Moura C.M., Dip N.et al. (2014) Comprehensive study of gene and microRNA expression related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 9, e113700 10.1371/journal.pone.0113700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly B.D., Miller N., Sweeney K.J., Durkan G.C., Rogers E., Walsh K.et al. (2015) A circulating microRNA signature as a biomarker for prostate cancer in a high risk group. J. Clin. Med. 4, 1369–1379 10.3390/jcm4071369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kopcalic K., Petrovic N., Stanojkovic T.P., Stankovic V., Bukumiric Z., Roganovic J.et al. (2019) Association between miR-21/146a/155 level changes and acute genitourinary radiotoxicity in prostate cancer patients: a pilot study. Pathol. Res. Pract. 215, 626–631 10.1016/j.prp.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kotb S., Mosharafa A., Essawi M., Hassan H., Meshref A. and Morsy A. (2014) Circulating miRNAs 21 and 221 as biomarkers for early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Tumor Biol. 35, 12613–12617 10.1007/s13277-014-2584-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kristensen H., Thomsen A.R., Haldrup C., Dyrskjøt L., Høyer S., Borre M.et al. (2016) Novel diagnostic and prognostic classifiers for prostate cancer identified by genome-wide microRNA profiling. Oncotarget 7, 30760 10.18632/oncotarget.8953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurul N.O., Ates F., Yilmaz I., Narli G., Yesildal C. and Senkul T. (2019) The association of let‐7c miR‐21 miR‐145 miR‐182 and miR‐221 with clinicopathologic parameters of prostate cancer in patients diagnosed with low‐risk disease. Prostate 79, 1125–1132 10.1002/pros.23825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leite K.R., Sousa-Canavez J.M., Reis S.T., Tomiyama A.H., Camara-Lopes L.H., Sañudo A.et al. (2011) Change in expression of miR-let7c miR-100 and miR-218 from high grade localized prostate cancer to metastasis. Urol. Oncol. 29, 265–269 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leite K.R., Tomiyama A., Reis S.T., Sousa-Canavez J.M., Sañudo A., Dall'Oglio M.F.et al. (2011) MicroRNA-100 expression is independently related to biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 185, 1118–1122 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leite K.R., Tomiyama A., Reis S.T., Sousa-Canavez J.M., Sañudo A., Camara-Lopes L.H.et al. (2013) MicroRNA expression profiles in the progression of prostate cancer—from high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia to metastasis. Urol. Oncol. 31, 796–801 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leite K.R., Reis S.T., Viana N., Morais D.R., Moura C.M., Silva I.A.et al. (2015) Controlling RECK miR21 promotes tumor cell invasion and is related to biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer. J. Cancer 6, 292 10.7150/jca.11038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li T., Li R.S., Li Y.H., Zhong S., Chen Y.Y., Zhang C.M.et al. (2012) miR-21 as an independent biochemical recurrence predictor and potential therapeutic target for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 187, 1466–1472 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lichner Z., Fendler A., Saleh C., Nasser A.N., Boles D., Al-Haddad S.et al. (2013) MicroRNA signature helps distinguish early from late biochemical failure in prostate cancer. Clin. Chem. 59, 1595–1603 10.1373/clinchem.2013.205450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lichner Z., Ding Q., Samaan S., Saleh C., Nasser A., Al‐Haddad S.et al. (2015) miRNAs dysregulated in association with Gleason grade regulate extracellular matrix cytoskeleton and androgen receptor pathways. J. Pathol. 237, 226–237 10.1002/path.4568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin H.M., Castillo L., Mahon K.L., Chiam K., Lee B.Y., Nguyen Q.et al. (2014) Circulating microRNAs are associated with docetaxel chemotherapy outcome in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 110, 2462–2471 10.1038/bjc.2014.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin H.M., Mahon K.L., Spielman C., Gurney H., Mallesara G., Stockler M.R.et al. (2017) Phase 2 study of circulating microRNA biomarkers in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 116, 1002–1011 10.1038/bjc.2017.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Long Q., Johnson B.A., Osunkoya A.O., Lai Y.H., Zhou W., Abramovitz M.et al. (2011) Protein-coding and microRNA biomarkers of recurrence of prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 46–54 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McDonald A.C., Vira M., Walter V., Shen J., Raman J.D., Sanda M.G.et al. (2019) Circulating microRNAs in plasma among men with low‐grade and high‐grade prostate cancer at prostate biopsy. Prostate 79, 961–968 10.1002/pros.23803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Melbø-Jørgensen C., Ness N., Andersen S., Valkov A., Dønnem T., Al-Saad S.et al. (2014) Stromal expression of MiR-21 predicts biochemical failure in prostate cancer patients with Gleason score 6. PLoS ONE 9, e113039 10.1371/journal.pone.0113039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mortensen M.M., Høyer S., Ørntoft T.F., Sørensen K.D., Dyrskjøt L. and Borre M. (2014) High miR-449b expression in prostate cancer is associated with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. BMC Cancer 14, 1–7 10.1186/1471-2407-14-859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nam R.K., Wallis C.J., Amemiya Y., Benatar T. and Seth A. (2018) Identification of a novel MicroRNA panel associated with metastasis following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 38, 5027–5034 10.21873/anticanres.12821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ostano P., Mello-Grand M., Sesia D., Gregnanin I., Peraldo-Neia C., Guana F.et al. (2020) Gene expression signature predictive of neuroendocrine transformation in prostate adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1078 10.3390/ijms21031078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reis S.T., Pontes-Junior J., Antunes A.A., Dall'Oglio M.F., Dip N., Passerotti C.C.et al. (2012) miR-21 may acts as an oncomir by targeting RECK a matrix metalloproteinase regulator in prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 12, 1–7 10.1186/1471-2490-12-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]