Abstract

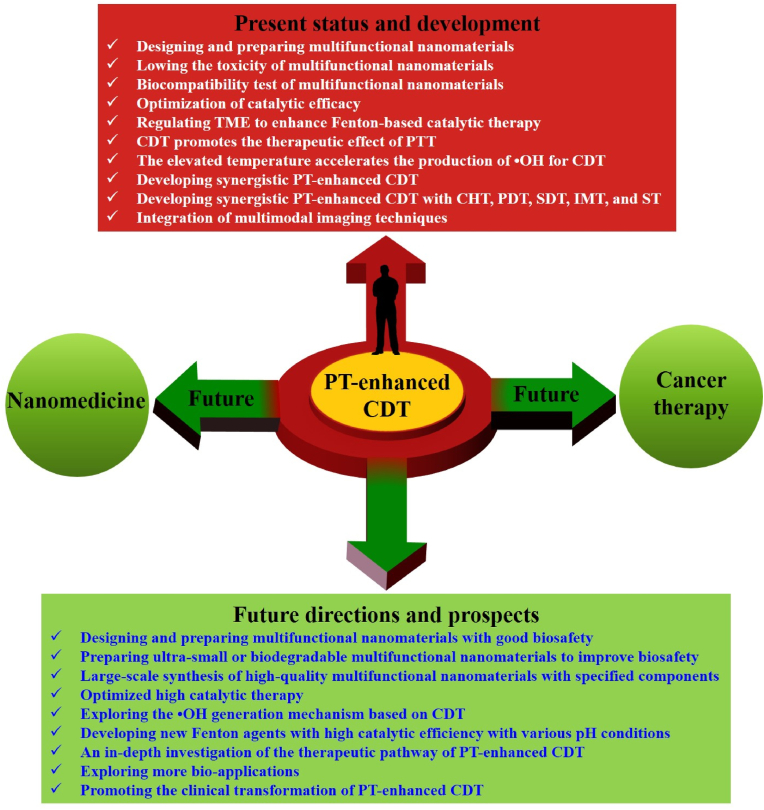

Photothermal (PT)-enhanced Fenton-based chemodynamic therapy (CDT) has attracted a significant amount of research attention over the last five years as a highly effective, safe, and tumor-specific nanomedicine-based therapy. CDT is a new emerging nanocatalyst-based therapeutic strategy for the in situ treatment of tumors via the Fenton reaction or Fenton-like reaction, which has got fast progress in recent years because of its high specificity and activation by endogenous substances. A variety of multifunctional nanomaterials such as metal-, metal oxide-, and metal-sulfide-based nanocatalysts have been designed and constructed to trigger the in situ Fenton or Fenton-like reaction within the tumor microenvironment (TME) to generate highly cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which is highly efficient for the killing of tumor cells. However, research is still required to enhance the curative outcomes and minimize its side effects. Specifically, the therapeutic efficiency of certain CDTs is still hindered by the TME, including low levels of endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), overexpression of reduced glutathione (GSH), and low catalytic efficacy of Fenton or Fenton-like reactions (pH 5.6–6.8), which makes it difficult to completely cure cancer using monotherapy. For this reason, photothermal therapy (PTT) has been utilized in combination with CDT to enhance therapeutic efficacy. More interestingly, tumor heating during PTT not only causes damage to the tumor cells but can also accelerate the generation of •OH via the Fenton and Fenton-like reactions, thus enhancing the CDT efficacy, providing more effective cancer treatment when compared with monotherapy. Currently, synergistic PT-enhanced CDT using multifunctional nanomaterials with both PT and chemodynamic properties has made enormous progress in cancer theranostics. However, there has been no comprehensive review on this subject published to date. In this review, we first summarize the recent progress in PT-enhanced Fenton-based CDT for cancer treatment. We then discuss the potential and challenges in the future development of PT-enhanced Fenton-based nanocatalytic tumor therapy for clinical application.

Keywords: Nanomaterials, Fenton reaction, Chemodynamic therapy, Photothermal therapy, Combination therapy

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This review summarizes recent progress in nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT.

-

•

PT-enhanced CDT as an emerging new modality for tumor-specific therapy.

-

•

The mechanism of PT-enhanced Fenton-based nanocatalytic tumor therapy is provided.

-

•

Propose the major challenges and prospects of nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT.

1. Introduction

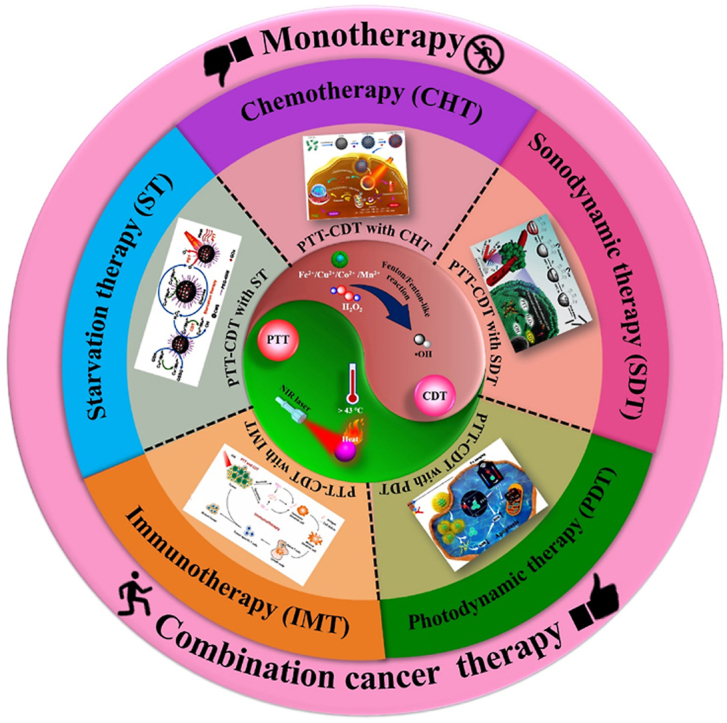

Cancer remains a major threat to human health worldwide because of the intense physical pain, high cytotoxicity, toxic side effects, and poor therapeutic efficiency associated with traditional therapeutic strategies, such as surgery, chemotherapy (CHT), and radiotherapy [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. Numerous studies have attempted to explore new therapeutic strategies, such as photothermal therapy (PTT), chemodynamic therapy (CDT), photodynamic therapy (PDT), sonodynamic therapy (SDT), immunotherapy (IMT), and starvation therapy (ST), with high efficacy and reduced side effects [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. New therapeutic strategies have been successfully used as an interesting alternative to traditional therapeutic strategies, and they are integrated with diagnostic imaging techniques, which are promising for cancer diagnosis and treatment [22,23]. However, monotherapy (e.g., PTT, CDT, PDT, SDT, IMT, or ST alone) cannot maximize the therapeutic efficiency because it is insufficient to effectively eliminate all of the tumor tissue, especially for large tumors [24]. Therefore, there are still many challenges to be overcome for the development of new strategies in the preclinical and clinical research of tumors to move away from monotherapy to combination cancer therapy (e.g., PT-enhanced CDT) to improve the therapeutic efficacy [[25], [26], [27], [28]].

CDT is an emerging nanocatalyst-based therapeutic strategy for tumor-specific therapy that has been developed over the last five years [[29], [30], [31]]. It is well known that CDT is highly selective for tumors and can greatly reduce side effects in normal tissues because it can induce tumor cell death through protein, DNA, and lipid damage upon the decomposition of H2O2 to generate highly toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as •OH via intratumoral metal ion (e.g., Fe2+, Cu2+, Co2+, etc.)-mediated Fenton or Fenton-like reactions [[32], [33], [34]]. Compared with other therapeutic modalities, CDT is initiated by endogenous stimuli, which is exceedingly selective and logical, as well as highly sensitive to the concentration of catalytic ions and the Fenton or Fenton-like reaction in the TME (e.g. H2O2, GSH, and pH value) [35]. In addition, CDT has several unique advantages, such as high tumor specificity, stimulus activation, lower systemic toxicity, and the ability to regulate the TME, for cancer treatment [36,37]. Despite its potential, the use of CDT alone is limited by issues such as the low content of endogenous H2O2 within the tumor, low catalytic efficacy of the Fenton or Fenton-like reactions in the mildly acidic TME (pH 5.6–6.8), and the overexpression of reduced glutathione (GSH) in the TME, which reduces •OH productivity and the therapeutic efficiency of CDT [[38], [39], [40]]. In particular, the neutral pH and mildly acidic pH (pH 5.6–6.8) of the TME are always weakened and non-beneficial for the Fenton reaction, which is only effective under relatively strong acidic conditions (pH 3.0–5.0) [41,42]. However, the low generation rate of the •OH in the mildly acidic TME limits the therapeutic efficacy of CDT [24,25,28,43]. Thus, increasing the production of •OH in the mildly acidic TMEs is critical for the further development of CDT.

Combination cancer therapy has emerged and achieved satisfactory therapeutic effects, which can produce significant synergistic effects and minimize adverse effects [24,44,45]. PT-based combination cancer therapies, such as PT-enhanced CDT [[46], [47], [48]], PT-enhanced PDT [49,50], and chemo-PT-enhanced PDT [26,51], have received a significant amount of research attention because of their outstanding super-additive effect. Among these, synergistic PT-enhanced CDT has recently emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer therapy due to its high selectivity, low toxicity, and negligible invasiveness [[52], [53], [54], [55]]. In addition, PT-enhanced CDT has been utilized in combination with CHT, PDT, SDT, IMT, and ST to increase tumor treatment performance [56]. It has been recognized that the integration of more therapeutic modalities such as PT-enhanced CDT with CHT, PDT, SDT, IMT, and ST, and diagnostic imaging techniques into one nanoplatform will further enhance the tumor suppression effect because of their synergistic effects [53,56].

Based on the basic principle that evaluated temperature can accelerate the reaction rate of Fenton or Fenton-like reactions, increasing the temperature in the tumor area will be an efficient strategy to enhance the efficacy of the Fenton or Fenton-like reactions with an increased yield of •OH, which has been generally employed because of its practicability and simplicity [24,27,41,42,48,[57], [58], [59]]. As previously reported tumor-heating strategies, PTT is a new type of cancer treatment strategy that converts near-infrared (NIR) light energy (700–1300 nm) into heat to kill cancer cells [[60], [61], [62]]. PTT has several advantages: the NIR wavelength is located in the “biological transparency window,” which is minimally absorbed by biological tissue, blood, or water; PTT is minimally invasive, highly selective, has a high spatial resolution, deep penetration, and low toxicity, which utilizes PT conversion to generate local heating for the ablation of tumors [29,30,63]. More interestingly, the PT effect on the tumor area not only causes damage to the tumor cells but can also accelerate the formation of ROS, such as •OH, thus enhancing the CDT efficacy, providing more effective cancer treatment [64]. Therefore, a reasonable combination of PTT with other therapeutic modalities (CDT) using multifunctional nanomaterials is highly desirable toward enhancing therapeutic efficiency [52,[65], [66], [67], [68]]. In addition, there is also an urgent need to develop multifunctional nanomaterials with both PT and chemodynamic properties for PT-enhanced CDT, which can help toward the development of highly effective combination cancer therapies [24,33,69].

To date, a variety of multifunctional nanomaterials, such as metal-, metal oxide-, and metal sulfide-based nanomaterials, have been widely studied for PT-enhanced CDT because of their strong NIR absorption, photothermal conversion efficiency (PCE) properties, biocompatibility, and chemodynamic properties [47,[70], [71], [72]]. In addition, a variety of multifunctional nanomaterials with diagnostic imaging properties have been widely used to improve imaging quality, which has excellent NIR absorption properties, magnetic properties, and other unique physicochemical properties, leading to more efficient and promising applications in diagnostic imaging [45,73]. Therefore, combination cancer therapy allows precise diagnosis and highly efficient tumor therapy, which has the potential to overcome the aforementioned drawbacks. In this review, we summarize the recent progress in multifunctional nanomaterials for PT-enhanced Fenton-based nanocatalytic tumor therapy.

2. Fenton or Fenton-like reaction in PT-enhanced CDT

Recently, various metal-based nanomaterials have been developed for CDT such as Fe, Cu, Co, Mn, Cr, Ag, etc [56]. CDT is generally based on Fenton or Fenton-like reactions and is used to trigger the in situ Fenton or Fenton-like reaction within the TME to produce a large amount of toxic •OH to kill cancer cells, and is a promising anticancer therapy with high specificity and minimal invasiveness [[74], [75], [76], [77], [78]]. Up to now, a lot of iron (Fe)-based nanocatalysts (e.g., Fe, Fe3O4, FeS2, etc.) with different nanostructures or formulations have been developed as a Fenton agent for CDT, which represent highly efficient Fenton reagents that trigger the intratumoral Fenton chemical reaction, resulting in extremely high nanocatalytic efficacy as well as high biocompatibility [74,77,78]. The specific Fenton reaction is commonly based on Fe2+ or Fe3+, which can produce •OH by catalyzing the decomposition of H2O2, resulting in the destruction of proteins, lipids, and DNA, allowing efficient tumor-specific treatment without producing significant side effects in healthy cells [74,[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85]]. The relevant equations (Eqs. (1), (2))) are shown below:

| Fe2++H2O2 → Fe3++•OH + OH− | (1) |

| Fe3++H2O2 → Fe2++•OOH + OH+ | (2) |

Apart from Fe-based nanocatalysts, other metal-based nanocatalysts based on Cu, Co, Mn, Cr, and Ag have also been developed as Fenton-like agents for CDT, which (e.g., Cu+, Co2+, Mn2+, Cr3+, and Ag+) can also catalyze the in situ decomposition of acidic H2O2 into highly toxic •OH via Fenton-like reactions leading to the specific destruction of tumor cells [33,[86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92]]. For example, Cu + or Cu2+ can also act as a Fenton-like catalyst for CDT, which can more easily react with H2O2 to generate •OH in the TME [33]. The copper (Cu)-based catalytic reactions are shown in Equations (3), (4).

| Cu++H2O2 → Cu2++•OH + OH− | (3) |

| Cu2++H2O2 → Cu++•OOH+H+ | (4) |

Fenton or Fenton-like reactions catalyzed by metal-based nanocatalysts commonly require mild acidic pH conditions (pH 3.0–5.0) for higher reaction rates. However, the pH of the TME is in the range of 5.6–6.8, which leads to the low catalytic efficacy of the Fenton or Fenton-like reactions [74,79,81]. In addition, the low concentration of H2O2 in the TME (<100 μM) generates low concentrations of •OH, which also hinders the effect of CDT [93,94]. Based on the basic principle that increasing the tumor tissue temperature by PTT can expedite the reaction rate of the Fenton or Fenton-like reactions, it can potentially produce a sufficient amount of the toxic •OH to induce tumor cell death [84,85]. In particular, the mildly acidic TME (pH 5.6–6.8) has a significantly less effective role in the Fenton reaction without PT treatment [95,96]. Therefore, PT-enhanced Fenton-based nanocatalytic tumor therapy can effectively enhance the reaction kinetics of the classical Fenton reaction [93,94]. Numerous nanomaterials are capable of catalyzing the Fenton reaction with NIR laser irradiation for the PT-enhanced Fenton reaction in CDT against cancer [97,98].

3. Multifunctional nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT

In recent years, numerous nanomaterials, such as metal (Fe, Cu, Au, etc.)-, metal oxide (WO3, MoOχ, MnO2, etc.)- and metal sulfide (Cu2−xS, CoS2, MoS2, etc.)-based nanomaterials with both PT and chemodynamic properties, have been developed for PT-enhanced CDT due to their excellent biocompatibility (Table 1) [27,48,87,[99], [100], [101]]. Multifunctional nanomaterial-based contrast agents have been widely used to improve imaging quality, and contrast agents have excellent near-infrared (NIR) absorption properties, magnetic properties, and other unique physicochemical properties, leading to more efficient and promising applications in multimodal imaging, such as photoacoustic imaging (PAI), fluorescence imaging (FLI), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) [45,73,102]. During CDT, Fenton or Fenton-like reactions can be triggered by various metal-based nanocatalysts [36,56,103]. Numerous nanomaterials have been used to catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to produce •OH, which destroys tumors by triggering intratumoral Fenton or Fenton-like reactions during CDT [[104], [105], [106]]. However, the mildly acidic TME decreases the •OH productivity [107,108]. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve the speed of •OH production in the mildly acidic TME [109]. Most importantly, the tumor-heating effect of PTT may accelerate the generation of •OH, thus enhancing the efficacy of CDT [[110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115]]. The combination of PT-enhanced CDT is highly desirable for generating a synergistic combination cancer therapy because the heat accelerates Fenton chemistry [110].

Table 1.

Summary of multifunctional nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT.

| Nanomaterials | Composition | Size (nm) | % PCE (η) | Irradiation conditions | Temp (°C) | Cell line/animal model | Treatment/imaging | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-based nanomaterials | FeS2-PEG | 180–200 nm | 28.6% | 808 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 5 min | 50 | MCF-7, and 4T1 cells; 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI | [27] |

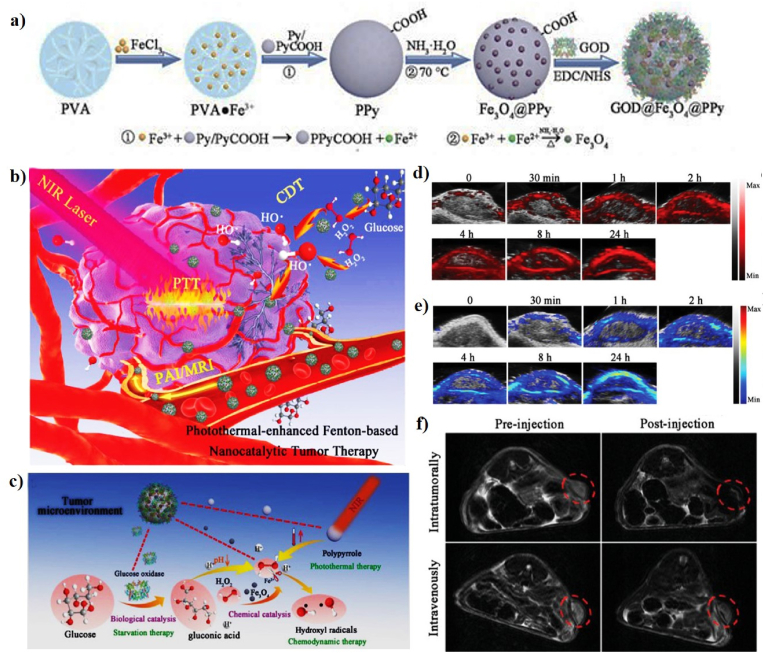

| Fe3O4@PPy@GOD NCs | 163.5 nm | 35.1 and 66.4% | 808 nm or 1064, 1.0 W/cm2, 15 min | 59 | L929, 4T1, HeLa, and HUVEC cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI/MRI | [59] | |

| PSAF NCs | 69.5 nm | 19.21% | 808 nm, 2.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 45 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT | [116] | |

| BSA-CuFeS2 NPs | 4.9 ± 0.9 nm | 38.8% | 808 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 5 min | 63 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/FLI/MRI | [109] | |

| PMFG | 12–20 nm | – | 808 nm, 0.8 W/cm2, 5 min | 45 | MCF-7 cell line | In vitro PTT-CDT | [25] | |

| Nb2C-IO-CaO2 | 150 nm | 32.1% | 1064 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 10 min | 54.4 | HUVEC and 4T1 cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT | [117] | |

| AFP NPs | 242.3 nm | – | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 47.7 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [118] | |

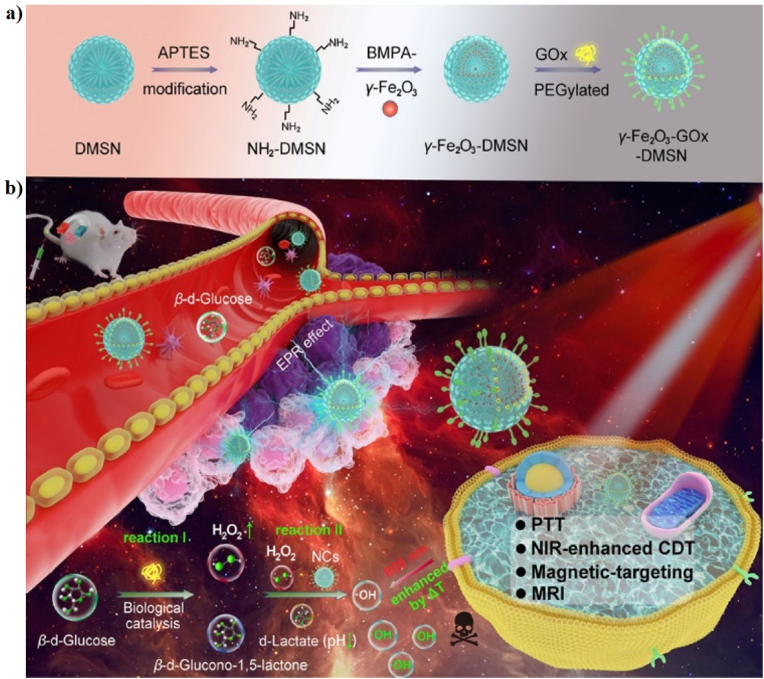

| γ-Fe2O3-GOx-DMSN NCs | 130 nm | 49.8% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 50 | HeLa and U14 cell lines; U14 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI | [119] | |

| FP NRs | 180 nm | 56.6% | 1064 nm, 0.5 W/cm2, 10 min | 55.7 | HeLa, L929, and U14 cell lines; U14 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo SDT-PTT-CDT/PAI/MRI | [48] | |

| EA-Fe@BSA NPs | 13.84 ± 2.53 | 31.9% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 15 min | 41 | HCT116 and HUCEC cell lines; HCT116 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI | [110] | |

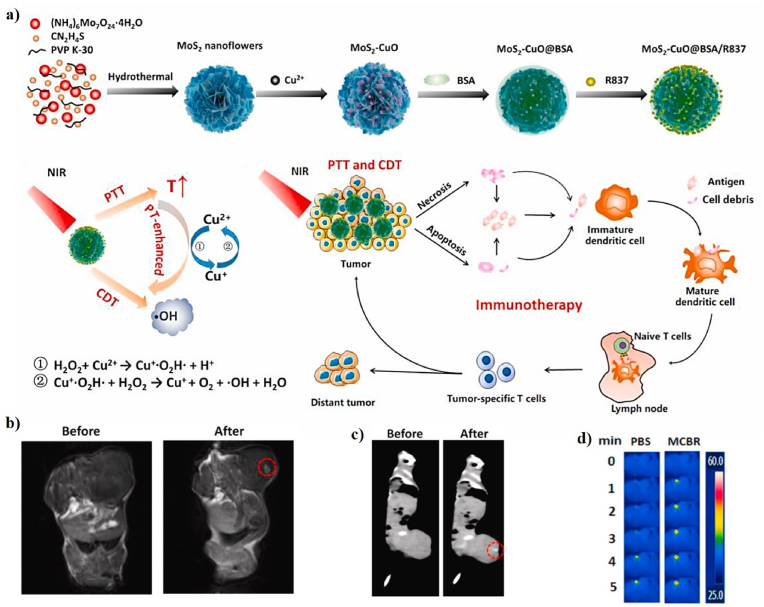

| BSO–FeS2 NPs | 7.27 ± 1.43 nm | 49.5% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 45 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PDT/PAI | [120] | |

| RLR NPs | 200 nm | 26.8%, | 808 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 5 min | 49 | MDA-MB-231 cell line; MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo chemo-PTT-CDT/MRI/FLI | [121] | |

| FeS2@RBCs | 185.2 nm | 30.2% | 1064 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 25.3 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI/FLI | [122] | |

| Fe-POM | 12.9 nm | 51.4% | 1060 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 50 | HUVEC and HeLa cell lines; HeLa tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [123] | |

| PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG | 150 nm | 28.14% | 808 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 10 min | 68.3 | L02 and MCF-7 cell lines; MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI/CT | [124] | |

| FMO | 450 nm | 48.5% | 808 nm, 0.7 W/cm2, 5 min | 50 | HeLa, and L929 cell lines; HeLa tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI | [125] | |

| CFMG hydrogel | – | – | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 49.5 | A375 and C2C12 cell lines; A375 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT | [126] | |

| FeO/MoS2-BSA | 150 nm | 56% | 1064 nm, 0.75 W/cm2, 5 min | 52 | HeLa and U14 cell lines; U14 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI | [127] | |

| F-BS NCs | 80 nm | 23.46% | 808 nm, 1.2 W/cm2, 5 min | 59.1 | L929 and HeLa cell lines; HeLa tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [128] | |

| Fe(III)-GA/GOx@ZIF-Azo | 3 nm | 65.3% | 808 nm, 1.54 W/cm2, 10 min | 46 | MCF-7 cell line; MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/FLI | [129] | |

| Cu-based nanomaterials | CP NCS | 22 nm | 27% | 1064 nm, 0.75 W/cm2, 5 min | 51 | L929, HeLa, and U14 cell lines; U14-tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI/PAI | [130] |

| PEG-Cu2Se HNCs | 86.89 ± 19.93 nm | 50.89% | 1064 nm, 0.75 W/cm2, 5 min | 58.4 | HUVEC and 4T1 cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [41] | |

| SC@G NSs | 60.94 nm | 46.3% | 1064 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 47.5 | 293T and 4T1 cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [131] | |

| PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs | 50 nm | – | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 70 | MCF-7, A549, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines; MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT | [72] | |

| CuO@AuCu-TPP | 255 nm | 37.9% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 51.6 | HeLa cell line; HeLa tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI/CT | [132] | |

| Cu9S8 NPs | ∼18.05 nm | – | 808 nm, 0.5 W/cm2, 5 min | 43 | 4T1 and HUVEC cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [64] | |

| CuO@CNSs-DOX | 15 nm | 10.14% | 808 nm, 2.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 60.3 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo Chemo-PTT-CDT/PAI | [133] | |

| MCBR | 130 nm | 24.6% | 808 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 5 min | 75 | CT26 cell line; CT26 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/IMT/CT/MRI | [47] | |

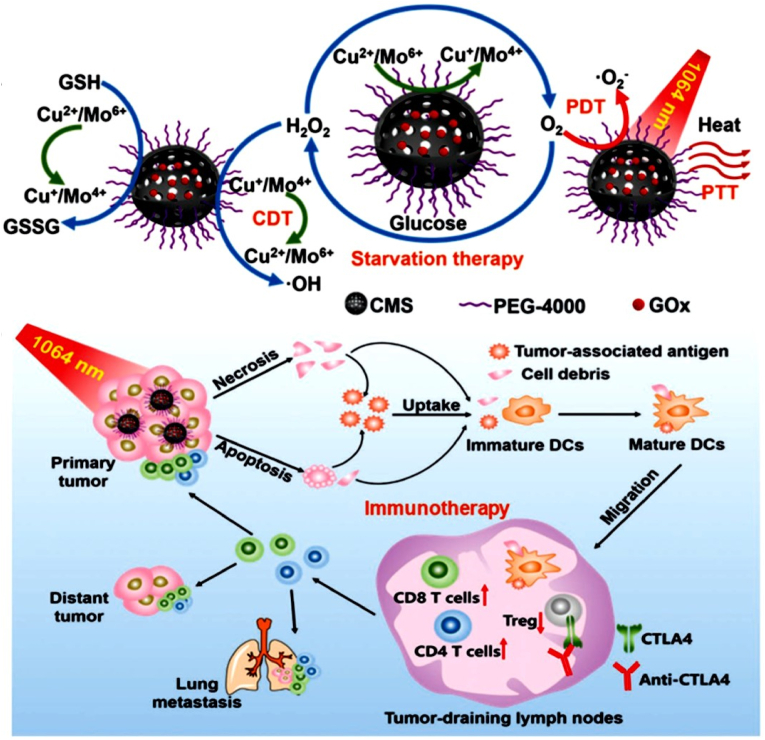

| PEG-CMS@GOx | 5.88 nm | 63.27% | 1064 nm, 0.48 W/cm2, 5 min | 52 | HeLa, L929, and U14 cell lines; U14 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PDT/IMT/PAI | [134] | |

| PFN | 22 nm | 30.17% | 1064 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min | 55 | Panc02 cell line; Panc02 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/MRI | [135] | |

| Gold-based nanomaterials | CAANSs | 52 nm | – | 808 nm, 2.4 W/cm2, 10 min | 68.4 | HeLa cell line | In vitro chemo-PTT | [136] |

| Au@HCNs | 275 ± 0.355 nm | 26.8% | 808 nm, 2.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 52.9 | CT26 cell line; CT26 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT | [137] | |

| Au@MnO2 | 25 nm | 23.6% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 15 min | 42 | 4T1 cell line; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI/MRI | [43] | |

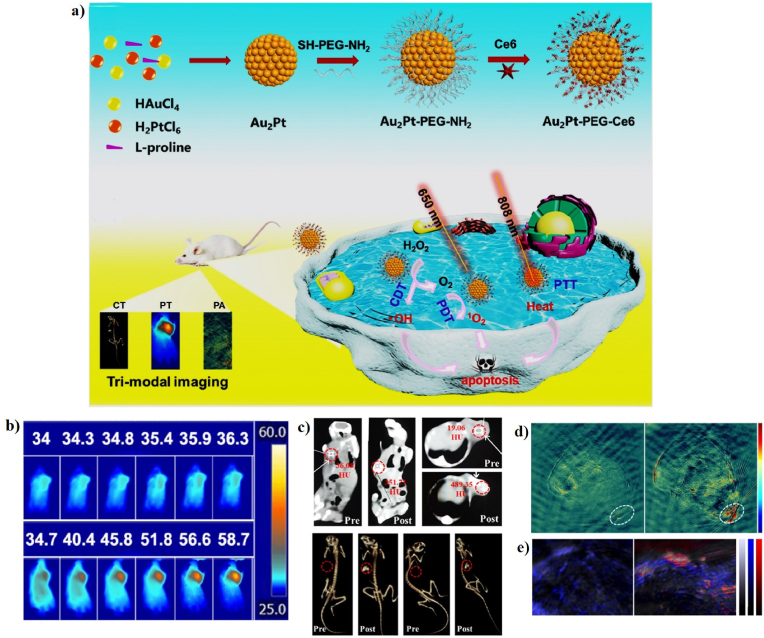

| Au2Pt-PEG-Ce6 | 42 ± 3 nm | 31.5 | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 5 min; 650 nm, 0.259 W/cm2, 5 min | 58.7 | HeLa, L929, and U14 cell lines; U14 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT/PDT/CDT/CT/PAI | [138] | |

| Metal oxide-based nanomaterials | WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs | 5.73 ± 0.93 nm | 25.8% | 1064 nm, 0.5 W/cm2, 5 min | 46 | HUVEC and 4T1 cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [24] |

| DCDMs | 123 nm | 51.5% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 58.7 | L929, HeLa, and U14 cell lines; U14 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/FLI/CT/MRI | [139] | |

| HMCMs | 80 nm | 23.5% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 8 min | 54 | MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MGC-803 cell lines; MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/FLI | [46] | |

| Metal sulfide-based nanomaterials | CoS2 NCs | 19.79 ± 5.2 nm | 60.4% | 808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2, 10 min | 55.4 | 4T1 and HUEVC cell lines; 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo PTT-CDT/PAI | [42] |

3.1. Iron-based nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT

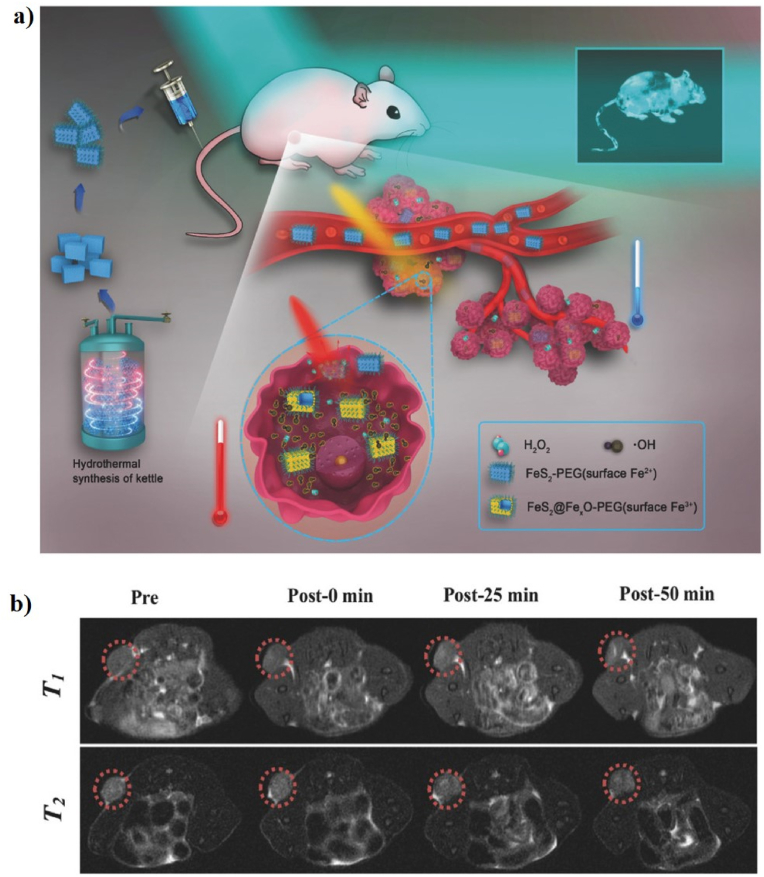

Iron (Fe)-based nanomaterials have been widely used in versatile biomedical applications, such as drug delivery, tissue engineering, PTT, PDT, CDT, SDT, ST, and multimodal imaging [[140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145]]. Some formulations of iron-based nanomaterials have been approved by the United States (US) Food and drug administration (FDA) for use in humans as therapeutics for iron deficiency, drug carriers for cancer therapy, and as contrast agents in MRI [81,[146], [147], [148], [149]]. Recently, iron-based nanomaterials have attracted a lot of attention as antiferromagnetic pyrite Fenton nanocatalysts for cancer therapy [81]. For example, Tang et al. first reported the use of antiferromagnetic pyrite polyethylene glycol (FeS2-PEG) nanocubes for self-enhanced MRI and PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 1a). Iron pyrite (FeS2) ion has been successfully used in a new era of cancer treatment because it can catalyze the production of ROS. PEG is a synthetic and biocompatible polymer that has been used in various applications, such as PEGylation, drug delivery, cancer therapy, and wound healing. FeS2 nanocubes were modified with SH-PEG to enhance their biocompatibility and solubility. More interestingly, the localized heat generated by FeS2-PEG via the PT effect, which accelerates the intratumoral Fenton reaction to efficiently generate •OH to kill tumor cells, implies that the synergistic effect of PTT and CDT into a single nanomaterial can be used as a “one-for-all” formulation. FeS2-PEG is cube-shaped with an average diameter of 180–200 nm. The PCE (η) values of FeS2-PEG and FeS2@FeꭓO-PEG are 28.6 and 29.5%, respectively. The in vitro PT-enhanced CDT effect of FeS2-PEG shows that the heat generated by the PT effect can accelerate and enhance the amount of •OH formed, suggesting that increased temperature can simultaneously induce ionization and improve the production of •OH. 4T1 tumor-xenografted mice were intratumorally injected with FeS2-PEG. The tumor-bearing mice treated with FeS2-PEG and laser irradiation were almost completely inhibited, implying the potential of FeS2-PEG as a PTT/CDT agent for cancer therapy. The T1-and T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) signal intensities showed a significant increase of 56.38 and 2.49%, respectively, which resulted in the synergism of the self-enhanced MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 1b) [27].

Fig. 1.

(a) A schematic illustration of the preparation of FeS2-PEG for self-enhanced MRI and PT-enhanced CDT. (b) In vivo T1-and T2-weighted MR images of tumor-bearing mice after intratumoral injection with FeS2-PEG (the red dotted circles). Reprinted with permission of Ref. [27]. Copyright 2017 Wiley.

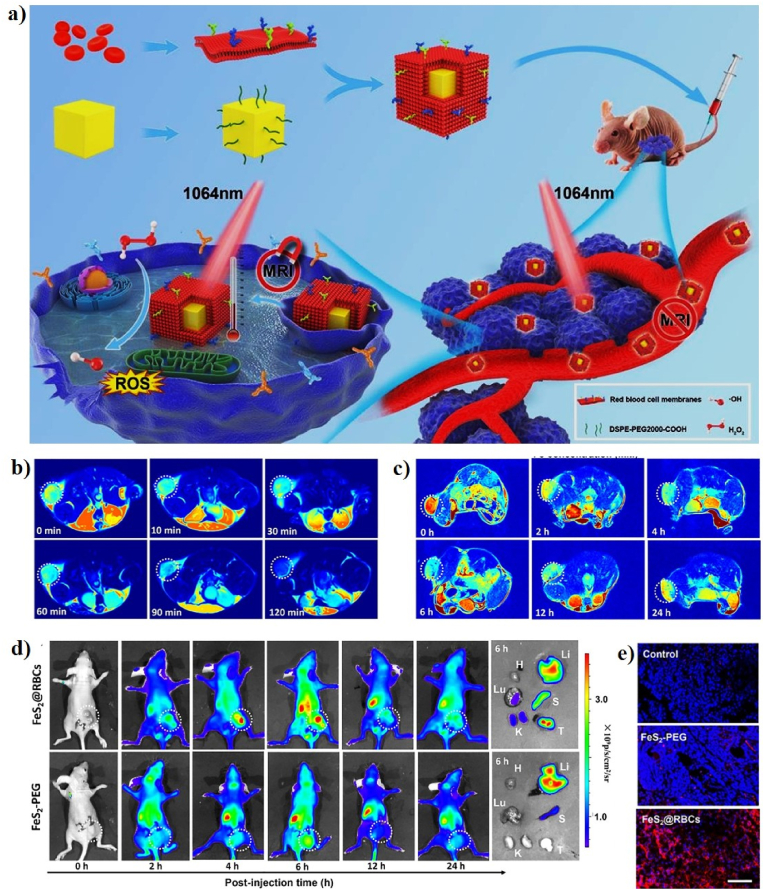

As a representative FeS2-based Fenton nanocatalyst in CDT, She et al. designed red blood cell membrane (RBC)-coated FeS2 for effective PT-enhanced CDT using an FDA-approved 1064 nm laser at 1.0 W/cm2 (Fig. 2a). FeS2 was synthesized by a facile solvothermal reaction and FeS2 was surface-modified with DSPE-PEG2000 to improve the water solubility (FeS2-PEG). RBC was finally coated on the surface of FeS2-PEG to form FeS2@RBCs. FeS2 has a cubic shape with an average diameter of 100–120 nm. The hydrodynamic size of FeS2@RBCs slightly increases from 168.3 nm (FeS2-PEG) to 185.2 nm, and their zeta potential of FeS2@RBCs was −10.3 mV because of the negative charge of RBCs. The PCE (η) of FeS2@RBCs was 30.2%. The synergetic effect of PT-enhanced CDT using FeS2@RBCs has been widely demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. The in vitro PT-enhanced CDT effect of FeS2@RBCs has been evaluated in 4T1 cells under laser irradiation, which showed a stronger inhibition rate of 4T1 cells when exposed to 1064 nm laser irradiation, suggesting the good synergistic PT-enhanced CDT antitumor effect upon 1064 nm laser irradiation. CDT relies on the Fe (FeS2@RBCs)-mediated Fenton reaction to induce cancer cell ferroptosis by catalyzing the decomposition of H2O2 into highly toxic •OH, which is only produced only in the TME without damaging healthy cells due to the high amount of H2O2 present in the tumor area. PT heating in the TME can significantly improve the Fenton reactivity and produce a high amount of •OH, which can effectively inhibit tumor growth with a clinically approved 1064 nm laser. In addition, FeS2@RBCs can be used for diagnosis and MRI-guided PTT/CDT. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously and intratumorally injected with FeS2@RBCs to explore the MRI signal change in the TME, which shows the TME-enhanced capability of FeS2@RBCs as an MRI contrast agent for imaging-guided therapy (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with the cyanine5 amine dye (Cy5)-modified FeS2@RBCs for in vivo FLI. The Cy5-FeS2@RBCs exhibit strong fluorescent signals in the TME 6 h post-injection, indicating that FeS2@RBCs have superior accumulation at the tumor site, which is more beneficial for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 2d, e) [122].

Fig. 2.

(a) A schematic illustration of the preparation of FeS2@RBCs for PT-enhanced CDT. In vivo T2-weighted MR images of tumor-bearing mice at various time points before and after intratumoral (b) and intravenous (c) injection of FeS2@RBCs. (d) In vivo FLI of tumor-bearing mice at various time points before and after intravenous injection of Cy5-modified FeS2@RBCs and ex vivo FLI images of the tumors and main organs collected from the treated mice 6 h post-injection. (e) Confocal images of tumor tissues 6 h post-injection. DAPI and Cy5 are shown in blue and red, respectively. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [122]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd.

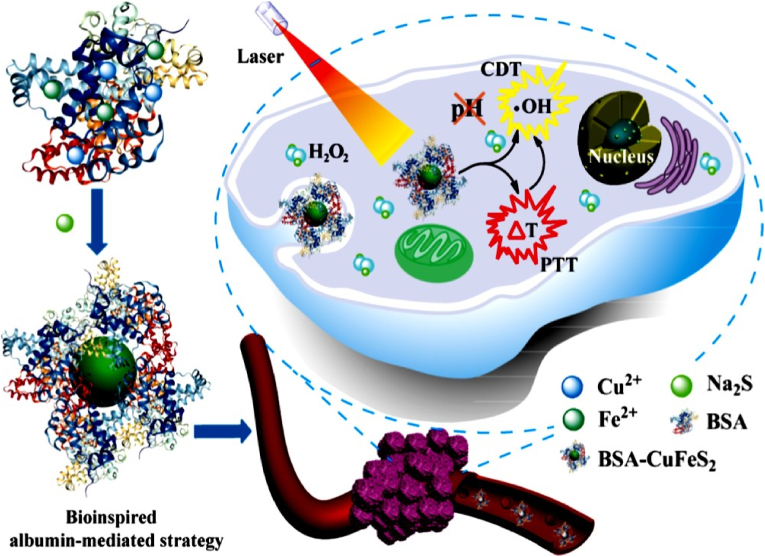

Currently, several ultra-small Fe-based nanomaterials have been developed as a multifunctional theranostic platform, which has a pH-independent Fenton reaction property to produce •OH and photothermal conversion efficiency for PT-enhanced CDT [109]. The ultra-small nanomaterials can be passed through the kidneys, allowing them to be eliminated more quickly from the body and increase long-term biosafety [150,151]. For example, Chen et al. synthesized ultra-small bovine serum albumin (BSA)-modified chalcopyrite NPs (BSA-CuFeS2 NPs) for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 3). BSA is a protein that has been utilized as a stabilizer to bind Fe and Cu ions due to the high affinity of carboxyl groups and surfactants. Na2S∙9H2O was then added to BSA-containing solutions to change the black color, implying the formation of BSA-CuFeS2 NPs. The particles of BSA-CuFeS2 NPs were mono-dispersed with an average size of 4.9 ± 0.9 nm. The PCE (η) value of the BSA-CuFeS2 NPs reached 38.8%, indicating their potential as PTT agents. BSA-CuFeS2 NPs exhibit pH-independent Fenton properties, which can produce a large amount of •OH in the weakly acidic TME. Subsequently, the heat generated by BSA-CuFeS2 NPs can enhance the •OH-generating efficacy, which is a synergistic effect in favor of efficient tumor growth inhibition. The FLI of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice was intravenously injected with BSA-CuFeS2 NPs at different time points. The fluorescence signal of the tumor area at 30 min post-injection increased 8.8-fold when compared with that in the control group, suggesting a high passive accumulation of BSA-CuFeS2 NPs at the tumor site. MR imaging showed a dramatic dark effect at the tumor site and the tumor MR signal rapidly decreased to 43.2%, indicating that the BSA-CuFeS2 NPs can serve as highly efficient MRI contrast agents to guide tumor ablation in vivo. More interestingly, the tumor treated with PTT/CDT was almost completely inhibited post-injection of the BSA-CuFeS2 NPs, suggesting that the BSA-CuFeS2 NPs exhibit the MRI-guided synergistic PT-enhanced CDT for highly efficient tumor ablation [109].

Fig. 3.

A schematic representation of the fabrication of BSA-CuFeS2 NPs for PT-enhanced CDT. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [109]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

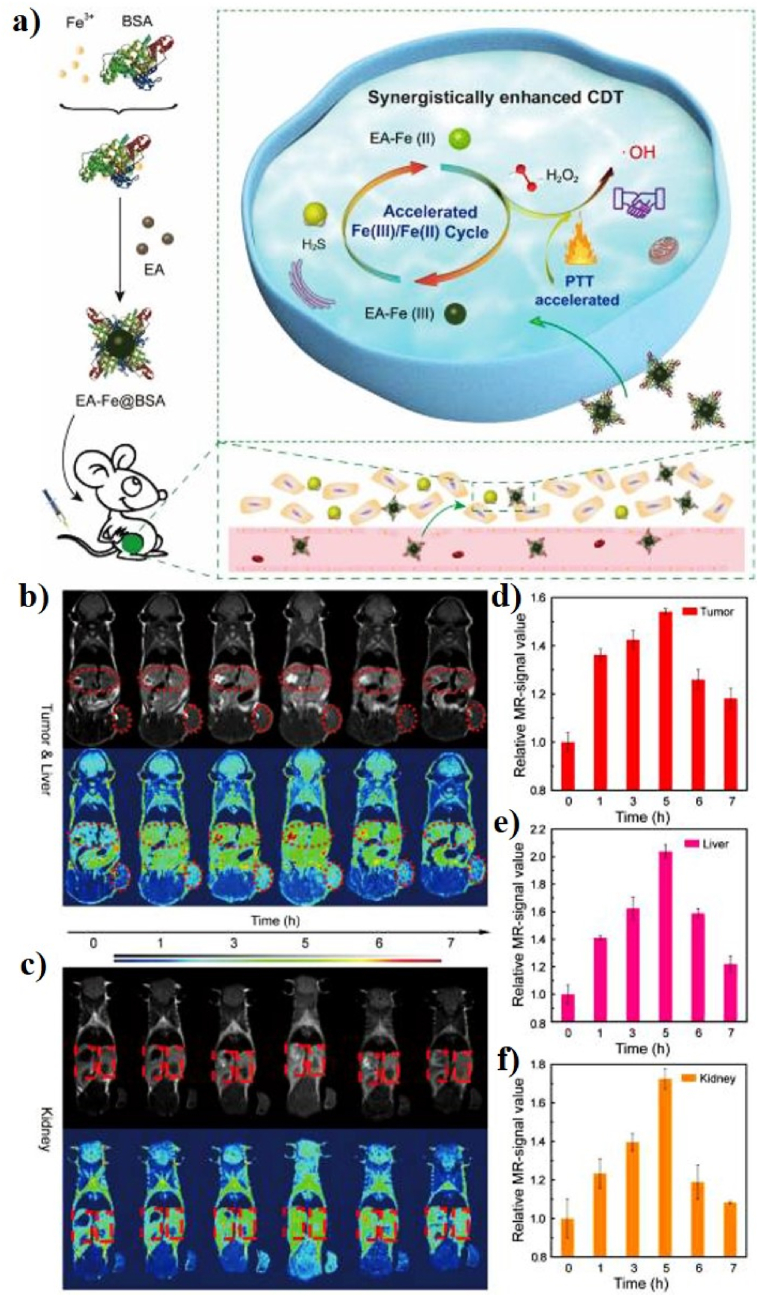

Another study was designed the ultra-small Fe-based nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT. In 2002, Tian et al. constructed ultra-small ellagic acid (EA)-Fe BSA (EA-Fe@BSA) NPs as a CDT agent for PTT to synergistically enhance CDT (Fig. 4a). EA-Fe@BSA was prepared via the simple assembly of EA, Fe(III), and BSA for endogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and PT-enhanced CDT efficiency. The EA-Fe@BSA NPs show a monodispersed spherical morphology with an average diameter of 13.84 ± 2.53 nm and the PCE (η) of EA-Fe@BSA NPs before and after reaction with sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) was ∼31.9 and 31.2%, respectively. The in vitro therapeutic efficacy of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs accelerates the production of •OH upon the addition of NaHS and increases the temperature by the heat generated via PT. NaHS was chosen to induce endogenous H2S to explore the H2S-stimulated CDT efficacy, which induced a greater conversion of Fe(III) in the EA-Fe@BSA NPs to Fe(II) and enhanced the CDT efficacy. The EA-Fe@BSA NPs exhibit obvious T1-weighted MRI both in vitro and in vivo, indicating their potential application as MRI contrast agents (Fig. 4b–f). More importantly, the PT heating effect of the EA-Fe@BSA NPs also accelerated the production of •OH via Fenton reactions in the tumor area. Even though H2S-enhanced CDT alone cannot inhibit the tumor, the synergy of H2S-enhanced CDT and PT-enhanced CDT almost completely inhibits and destroys the tumor, demonstrating outstanding enhanced CDT efficacy upon H2S and PTT acceleration [110].

Fig. 4.

(a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of EA-Fe@BSA NPs for PT-enhanced CDT. In vivo MR images of the tumor and liver (b), and kidney (c) after intravenous injection of EA-Fe@BSA NPs. The corresponding MR signal intensities of the tumor (d), liver (e), and kidney (f) images. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [110]. Copyright 2020 IVYSPRING International Publisher.

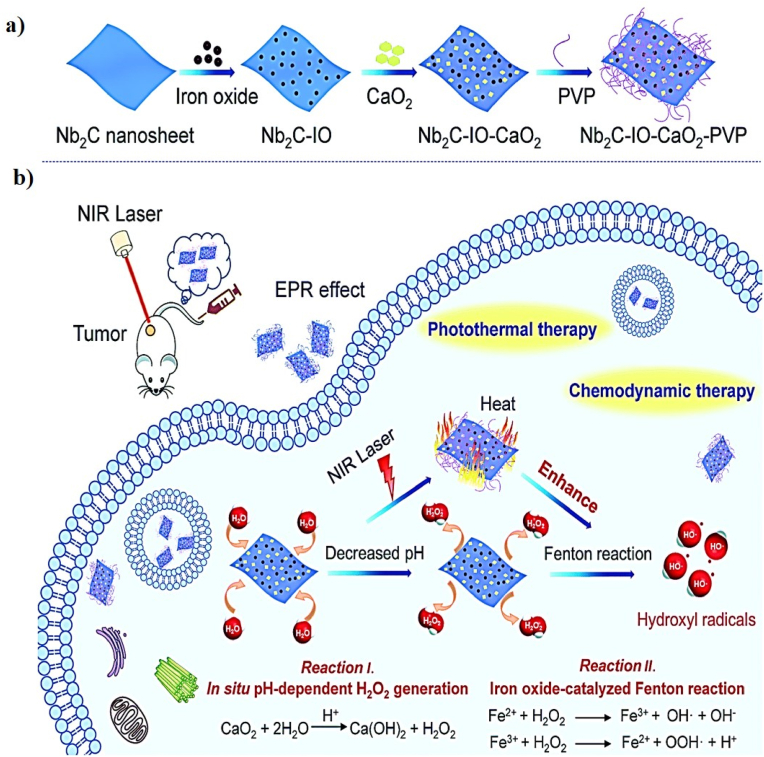

Iron oxide nanomaterials have broad potential in theranostic applications because of their excellent biocompatibility, photothermal conversion efficiency, and magnetic properties, which can be used as Fenton nanocatalysts for cancer therapy [152,153]. Similarly, Gao et al. reported the use of iron oxide (IO)-loaded niobium carbide (Nb2C) MXene nanosheets (Nb2C-IO) conjugated with calcium peroxide (CaO2) NPs to form two-dimensional (2D) composite nanosheets (Nb2C-IO-CaO2) for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 5a, b). The Nb2C and CaO2 NPs have average hydrodynamic sizes of 150 and 8 nm, respectively, and the zeta potential of Nb2C-IO-CaO2 is −5.3 mV. The PCE (η) of Nb2C-IO-CaO2 nanosheets, which act as potent and durable PT agents for PT-enhanced CDT, was 32.1%, which was higher than that of commonly reported photothermal agents, such as Fe3O4@CuS NPs (19.2%) [154] and Fe3O4 nanoclusters (20.8%) [155]. Nb2C-IO-CaO2 employs CaO2 as a potent H2O2 supplier to sustain the IO NP-mediated catalytic Fenton reaction to produce a high amount of •OH to induce tumor cell death. In addition, the Nb2C nanosheets also serve as PT agents to convert NIR light into heat, which can greatly improve the intratumoral •OH yield via Fenton reactions, leading to a more satisfactory therapeutic effect. Nb2C-IO-CaO2 exhibits significantly higher cytotoxicity after laser irradiation, and the maximum apoptosis was 93.3% in 4T1 cells, resulting in PT-enhanced ROS generation by the Fenton reaction produced by Nb2C-IO-CaO2 with self-supplied H2O2. The in vivo synergistic PT-enhanced CDT efficiency of Nb2C-IO-CaO2 was evaluated and the tumor temperature of mice injected with Nb2C-IO-CaO2 rapidly increased to 54.4 °C upon laser irradiation at 1064 nm, leading to the complete inhibition of tumor growth, implying that Nb2C-IO-CaO2 has promising potential as a tumor therapeutic agent for PT-enhanced CDT [117].

Fig. 5.

A schematic illustration of (a) the preparation of Nb2C-IO-CaO2 nanosheets and (b) PT-enhanced CDT utilizing Nb2C-IO-CaO2 nanosheets. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [117]. Copyright 2019 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Also, iron oxide-based Fenton nanocatalysts have excellent catalytic ability to generate •OH. For instance, Zhang et al. synthesized a novel iron oxide (FeO)/molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) modified with BSA (FeO/MoS2-BSA) for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 6a). 2D MoS2 nanosheets have been used as photoablation agents because of their strong NIR absorbance. In addition, MoS2 nanosheets have a peroxidase-mimicking ability, allowing them to catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to produce •OH. FeO/MoS2 was synthesized via electrostatic interactions and then modified with BSA to enhance their biocompatibility. MoS2 has an average size of 150 nm, and FeO has an average size of 8 ± 3 nm. The PCE (η) of the FeO/MoS2-BSA nanocomposite at 1064 nm was calculated to be 56%, indicating its excellent PT performance. The Mo4+ ions on the surface of the MoS2 nanosheets can accelerate the conversion of Fe3+ into Fe2+, while Fe2+ ions can decompose H2O2 to produce a large amount of •OH via Fenton reactions, which can be further improved by the PT effect. The in vitro therapeutic effect of FeO/MoS2-BSA on HeLa cells was confirmed using calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI) staining, which showed a stronger red fluorescence after 1064 nm laser irradiation, indicating the destruction of the HeLa cells by •OH and PT heat. The in vivo PT efficiency of the FeO/MoS2-BSA nanocomposites on the U14 tumor xenograft model was demonstrated using an IR thermal camera (Fig. 6b). The temperature of the tumor area was increased to 52 °C upon 1064 laser irradiation for 10 min and the treated tumors were thoroughly ablated after the 5th day of treatment, implying that synergistic PT-enhanced CDT has high anti-cancer efficiency. Furthermore, the MR signal of the tumor area was observed with an increase in the concentration of FeO/MoS2-BSA, confirming that FeO/MoS2-BSA can act as a promising MRI contrast agent (Fig. 6c) [127].

Fig. 6.

(a) A schematic illustration of the fabrication of FeO/MoS2-BSA for PT-enhanced CDT. (b) IR thermal images of tumor-bearing mice upon intravenous injection of normal saline and FeO/MoS2-BSA, followed by 1064 nm laser irradiation at 0.75 W/cm2 for 10 min. (c) In vivo MR imaging of tumor-bearing mice at various time points after intravenous injection of FeO/MoS2-BSA. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [127]. Copyright 2020 Springer.

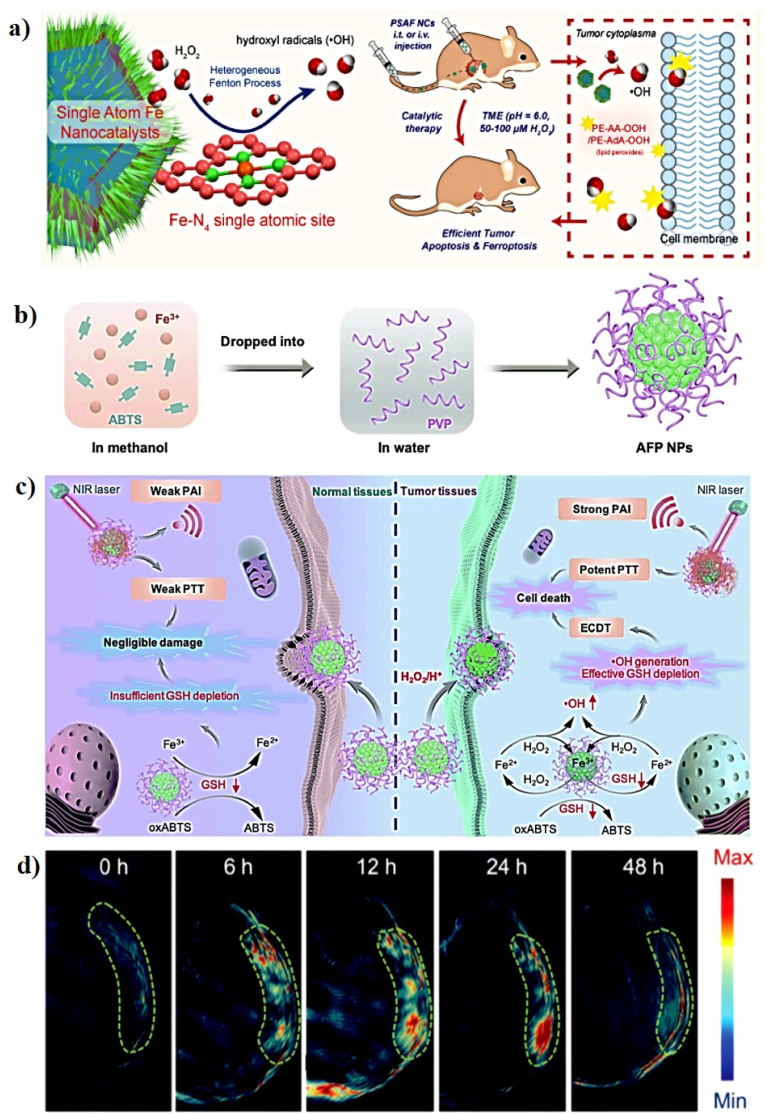

A number of Fe-based nanomaterials showed great potential for PT-enhanced CDT because of their photothermal conversion efficiency and •OH generation capacity via Fenton reaction [156]. In 2019, Huo et al. fabricated PEGylated single-atom Fe-containing nanocatalysts (PSAF NCs) for highly efficient tumor inhibition via the Fenton reaction (Fig. 7a). Single-atom Fe catalysts (SAF NCs) have evolved to become highly efficient electrocatalysts, which will enable improved therapeutic efficiency in tumor-specific nanocatalytic therapy. 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)] (DSPE-PEG-NH2) is a linear heterobifunctional PEGylation reagent with a hydrophobic structure DSPE and amino-terminated PEG chain. The SAF NCs were PEGylated with DSPE-PEG-NH2 via hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions after vigorous sonication to form the PSAF NCs. The SAF NCs exhibit a uniform dodecahedral geometry with an average diameter of ∼69.5 nm. When the PSAF NC aqueous solution (200 μg/mL) was irradiated with an 808 nm laser at 2.0 W/cm2 for 10 min, the temperature increased by 45 °C with high PT stability and strong PCE (19.21%). The in vitro therapeutic effects of PSAF NCs against 4T1 cells were evaluated, and cells treated with PSAF NCs + H2O2 exhibited a strong inhibitory effect. It is clear that the Fenton reaction catalyzed by PSAF NCs also resulted in the production of a large amount of toxic •OH and localized apoptosis and ferroptosis of tumor cells when exposed to H2O2 in the acidic TME, which can be effectively enhanced by the mild-PT effect. The in vivo catalytic therapeutic performance of PSAF NCs was evaluated and the PT-enhanced CDT of tumors could fully destroy the tumors in mice on the 5th and 9th days post-injection of PSAF NCs with laser irradiation [116].

Fig. 7.

(a) A schematic illustration of the preparation of PSAF NCs for PT-enhanced CDT. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [116]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. (b) A schematic illustration of the synthesis procedure for AFP NPs. (c) Proposed mechanism for AFP NPs in the PT-enhanced Fenton-based CDT of tumor and normal tissues. (d) In vivo PA signals of the tumor area at various time points after intravenous injection of AFP NPs. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [118]. Copyright 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry.

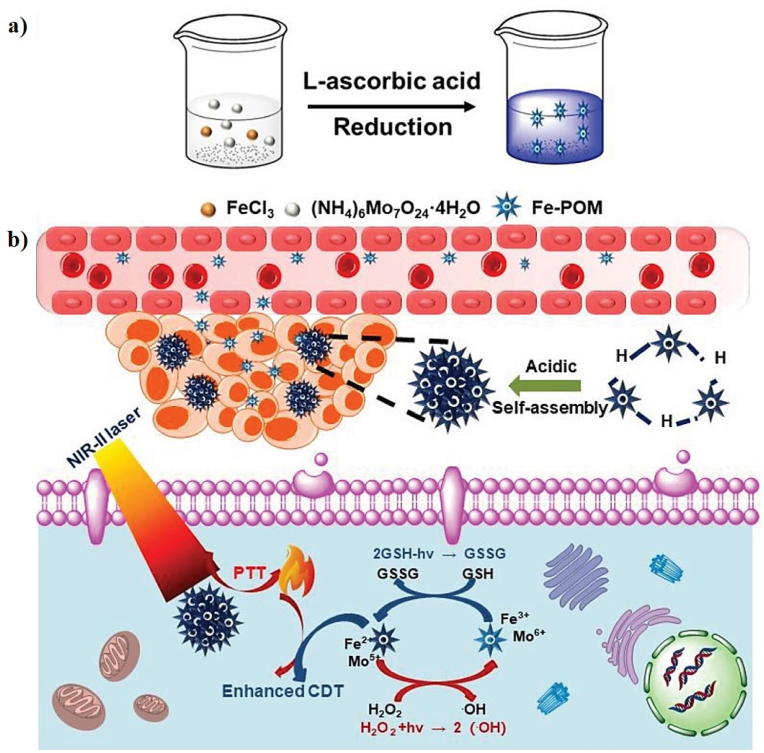

As a representative Fe-based Fenton nanocatalyst in CDT, Liu et al. developed a novel all-in-one ABTS-Fe/PVP (AFP) NP in which Fe3+ and 2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) were dissolved in methanol, and the resulting solution mixed with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as a new CDT agent (AFP NP) for PAI-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 7b, c). ABTS is water-soluble horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate that can be catalyzed by HRP in the presence of H2O2 to generate its green oxidized form (oxABTS), which exhibits high absorption in the NIR region. PVP is a water-soluble polymer that coordinates to Fe3+ and Fe2+. The AFP NPs exhibit a sphere-like morphology with an average size of 242.3 nm and a zeta potential of −12.2 mV. The Fe3+ in the AFP NPs can produce •OH and deplete GSH in the presence of H2O2, demonstrating that AFP NPs can increase intracellular oxidative stress. The PA images and signals were observed at different time points post-injection of the AFP NPs and the PA signals gradually increase at the tumor site, demonstrating the rapid accumulation of AFP NPs at the tumor site through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (Fig. 7d). To investigate the PT effect of AFP NPs, the tumor temperature of the AFP NPs was rapidly increased to 47.7 °C after laser irradiation, which was sufficient to kill the tumor, confirming that the AFP NPs show superior tumor-growth inhibition efficacy because of their efficient CDT through the simultaneous generation of •OH and depletion of GSH [118]. In a similar study, Shi et al. successfully prepared molybdenum (Mo)-based polyoxometalate (POM) cluster doped with Fe (Fe-POM) as an intelligent theranostic agent for PT-enhanced CDT in the NIR-II window (Fig. 8a, b). POM clusters were prepared via a facile synthesis procedure and FeCl3 and l-ascorbic acid were added to the POM solution to form Fe-POM. The Fe-POM had a highly uniform size and morphology with ultra-small diameters of 12.9 nm. The PCE (η) of Fe-POM was calculated to be 51.4%, suggesting the PT heating ability of Fe-POM in the NIR-II window. Fe2+ and Mo5+ can trigger the Fenton reaction, which can convert H2O2 into harmful •OH in the presence of Fe-POM and simultaneously deplete GSH for amplified CDT efficiency, confirming that Fe-POM can significantly improve the PT-catalytic efficacy. This PT effect can further improve the CDT effect, thereby achieving the synergistic effect of PT-enhanced CDT, which can effectively cause cancer cell death in vitro and fully inhibit the tumor in vivo. To obtain a more precise combination of PTT/CDT, PAI guidance will be beneficial for tracking the time-dependent tumor retention of Fe-POM. The PA signal observed at the tumor site gradually increases 2 h post-injection of Fe-POM, suggesting the rapid accumulation of Fe-POM in the tumor area [123].

Fig. 8.

A schematic illustration of the synthesis of Fe-POM (a) and (b) the synergistic mechanism of as-prepared Fe-POM applied in combination therapy. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [123]. Copyright 2020 Wiley.

In another example, Hu and co-workers successfully synthesized PB NCs and achieved the in situ reductions of FePt NPs, followed by coating with PEG and hyaluronic acid (HA) (PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG) for triple-modal imaging-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 9a). PB NCs have been used as new photo-absorbing agents for photothermal ablation therapy. FePt NPs can act as ferroptosis agents and have been used in MRI and CT imaging diagnoses. HA has been used as a specific targeting agent for cancer therapy. PEG is a synthetic polymer that can be used as a coating material on the surface of PB@FePt. The PB NCs have a nanocube structure with a hydraulic diameter of 150 nm. The PCE (η) of PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG was calculated to be 28.14%, implying that PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG possessed a good PT conversion ability. PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG shows a strong synergistic effect on cancer cell inhibition in vitro. PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG has been used in tri-model imaging diagnosis (MRI/CT/PT imaging) (Fig. 9b–d). Tumor-bearing mice were scanned using an MR, CT, and near-infrared (IR) thermal imaging system post-injection of PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG. The MR and CT signals of the tumor site increase significantly, suggesting that PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG has the potential to serve as an efficient CT/MR contrast agent for PT-enhanced CDT. The PT imaging ability of PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG was also investigated and the thermal signal of the tumor became dark red after laser irradiation, implying that the PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG can serve as a PT imaging agent. PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG can effectively catalyze the conversion of H2O2 in tumor-bearing mice into harmful •OH, which can effectively inhibit tumor growth under laser irradiation, implying that the PT-enhanced CDT effect of PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG effectively kills the cellular structure and promotes tumor ablation [124].

Fig. 9.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthetic process used to construct PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG for PT-enhanced CDT. (b) In vivo MR images of tumor-bearing mice at various time points post-injection of PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG. (c) CT image of tumor-bearing mice injected with PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG. (d) IR thermal image of tumor-bearing mice injected with PB@FePt-HA-g-PEG. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [124]. Copyright 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry.

As a typical application, Chen et al. reported, for the first time, the use of biodegradable Fe-doped molybdenum oxide (MoOχ) ultra-fine nanowires (FMO) as Fenton reagents for PT-enhanced CDT. The FMO was synthesized using a single solvothermal technique and modified with PEG-4000. The ultra-fine FMO nanowires had a uniform thickness and lengths of ∼450 nm. The PCE (η) of FMO reached 48.5% under 808 nm laser irradiation, implying that FMO has outstanding PEC and thus strong potential as a PT agent for CDT. The in vitro synergistic therapeutic effect of FMO on tumor cells was evaluated. The Fe2+ and Mo5+ in the FMO can effectively catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 and generate •OH via the Fenton reaction, and subsequently, the intracellular GSH can also be depleted, which may further enhance tumor cell death. The FMO-treated cells were co-stained and observed under a fluorescence microscope. The FMO + H2O2 + laser showed a strong red fluorescence, indicating that the synergistic therapeutic effect of •OH and PT heat had an improved killing efficacy on tumor cells. The tumor-bearing mice were scanned before and after the intratumoral injection of FMO, and the MR signal was observed at the tumor site, indicating that the FMO can be applied as a potential contrast agent for T1-weighted MRI. The tumor temperature in mice injected with the FMO solution was increased up to 50 °C upon laser irradiation for 10 min and the treated tumors completely disappeared within 15 days, indicating that FMO has great potential for use in MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT [125].

Recently, Zhao and co-workers reported the use of Fe3O4 magnetic NPs and bismuth trisulfide (Bi2S3) integrated virus-like Fe3O4@Bi2S3 nanocatalysts (F-BS NCs) modified with BSA (F-BSP NCs) for PT-enhanced CDT. Bi2S3 has been used as a PT agent for PTT because of its excellent in vivo biocompatibility, stability, and high PCE, and ease of synthesis. Fe3O4 magnetic NPs exhibit peroxidase-like activity. The Fe3O4 magnetic NPs were synthesized using a simple hydrothermal technique, which was dispersed in a thioacetamide (TAA) and Bi(NO3)3 solution under ultrasonication to form virus-like Fe3O4@Bi2S3 (F-BS NCs) and then modified with BSA (F-BSP NCs) to enhance their stability and in vivo biocompatibility. The Fe3O4 NPs have an average diameter of 80 nm. The zeta potentials of F-BS NCs and F-BSP NCs were −8.05 and −17 mV, respectively. The PCE (η) of the F-BS NCs was 23.46%. The Fe2+ ions in the F-BSP NCs react with H2O2 to produce highly toxic •OH via a mild PT effect and sequential Fenton reactions, which can further improve the CDT effect. The in vitro anticancer therapeutic efficacy of F-BSP NCs shows the highest apoptosis and necrosis after laser irradiation. The in vivo therapeutic ability and PAI performance of F-BSP NCs were further investigated in tumor-bearing mice. The tumor temperature of the F-BS NCs reached 59.1 °C upon laser irradiation and the treated tumor almost disappeared after 14 days of treatment, suggesting that the synergistic PT-enhanced CDT has an excellent therapeutic effect. The F-BS NCs also showed a clear PA signal in the tumor after intratumoral injection, confirming that the F-BS NCs can serve as ideal diagnostic PAI agents for diagnosis and treatment [128].

3.2. Copper-based nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT

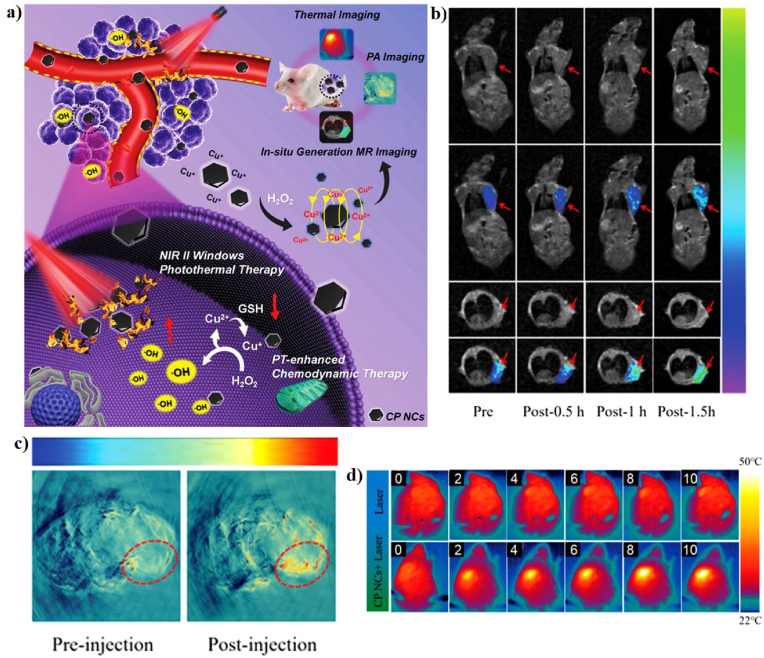

Recently, copper-based nanomaterials have found many applications in a variety of research fields in CDT as potential alternatives for iron-based nanomaterials with promising developments and progress [99]. Copper (Cu) ions can also drive the Fenton-like reactions that prompt the decomposition of H2O2 to produce •OH to induce cancer cell apoptosis [36,38]. More importantly, CDT triggered by copper ions can start under neutral and very mild acidic conditions, which accurately matches the TME [56]. Cu-based nanomaterials are currently explored as new PT agents due to their low biotoxicity, easy fabrication, and low cost [61]. For example, Liu et al. reported, for the first time, the use of trithiol-terminated poly-(methacrylic acid) (PTMP-PMAA)-modified copper(I) phosphide nanocrystals (CP NCs) for MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 10a). Cu(I) phosphide was synthesized from Cu(II) chloride dehydrate (CuCl2·H2O) and triphenyl phosphite (TPOP) at high temperature to form Cu3P, which was then coated with PTMP-PMAA to form the CP NCs to enhance their hydrophilicity. The CP NCs exhibit a hexagonal morphology with an average particle size of ∼22 nm. The temperature of the CP NC aqueous solutions reached 51 °C after 10 min of laser irradiation, suggesting that the CP NCs have excellent PT properties. The PCE (η) of the CP NCs was determined to be 27%, which can further improve the Fenton-like reaction. The MR and PA imaging properties were investigated in vitro and in vivo. The T1-MR signal of the tumor region was significantly enhanced after injection of the CP NCs, indicating that CP NCs can be used as a new in situ self-generation MRI contrast agent (Fig. 10b). The PA signal in the tumor area was notably enhanced 12 h post-injection of the CP NCS, indicating the potential PA imaging ability of CP NCs (Fig. 10c). The Cu(I) on the surface of CP NCs is more effective in the weakly acidic TME with a high production of •OH and triggers the apoptosis of cancer cells, suggesting that CP NCs have excellent •OH generation capability with the help of 1064 nm laser irradiation. The in vivo synergistic therapeutic effect of CP NCs on U14 tumor-bearing mice was confirmed using IR thermal camera (Fig. 10d). The tumor temperature of mice injected with the CP NC solution was increased up to 48 °C upon 1064 nm laser irradiation and tumor growth was significantly inhibited on the 5th day. Furthermore, the excess GSH in the TME can further reduce the Cu(II) produced by the Fenton-like catalytic reaction to Cu(I), enhancing the production of •OH, indicating that the CP NCs have great potential for use in MRI/PAI-guided PT-enhanced CDT [130].

Fig. 10.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthesis of CP NCs and their application in synergistic combination therapy. In vivo T1-MR (b) and PA (c) imaging of tumor-bearing mice. (d) In vivo IR thermal images of tumor-bearing mice. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [130]. Copyright 2019 Wiley.

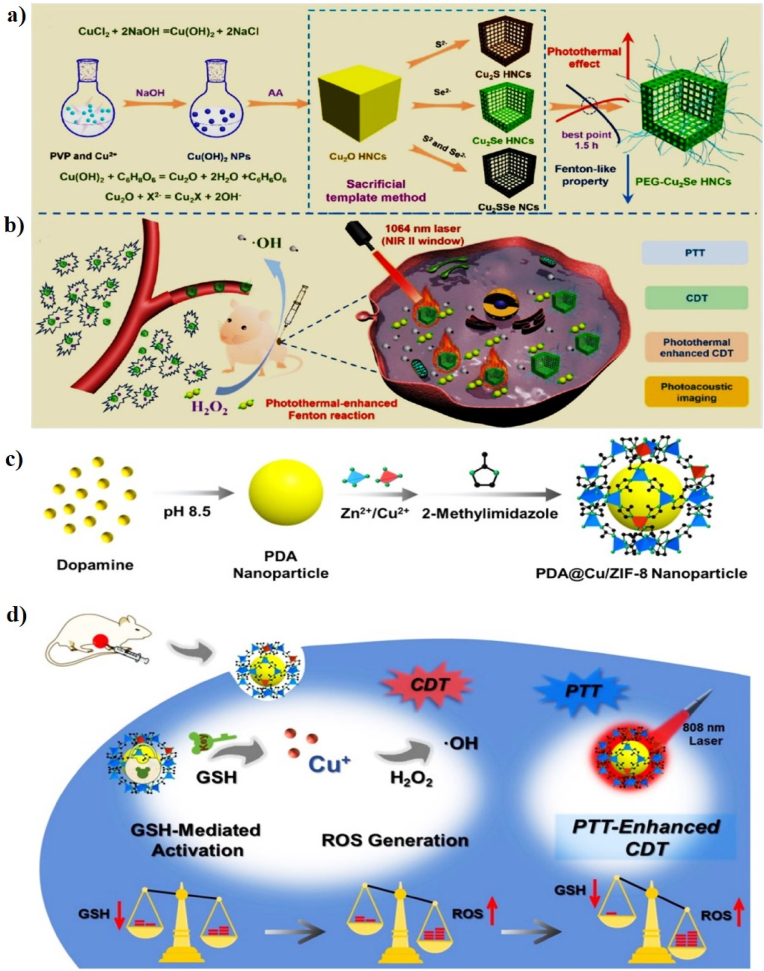

Cu-based nanomaterials have become research hotspots in the field of biomedicine in recent decades because of their excellent photothermal conversion efficiency, biocompatibility, and Fenton-like properties [65]. Compared with other copper-based nanomaterials, copper selenide (Cu2Se) nanomaterials are particularly interesting due to their strong absorption in NIR window and Fenton-like properties, and Cu and selenium (Se) are considered as important trace elements in the human body [157,158]. For example, Wang and co-workers successfully synthesized PEG-coated copper selenide (Cu2Se) hollow nanocubes (HNCs) as a promising catalyst for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 11a, b). The HNCs were prepared via an anion exchange method using Cu2O nanocubes and then modified with thiolated PEG to enhance the stability and dispersibility (PEG-Cu2Se HNCs). The PEG-Cu2Se HNCs show excellent biocompatibility, high PCE, and strong Fenton-like catalytic properties. The Cu2Se HNCs have a regular cubic morphology with an average diameter of 86.89 ± 19.93 nm. The PCE (η) of the Cu2Se HNCs was 50.89% in the NIR-II window, which was significantly higher than that of commonly reported photothermal agents, such as Au–Cu9S5 NPs (37%) [159] and Cu3BiS3 nanorods (40.7%) [160]. In vitro synergistic treatment with PEG-Cu2Se HNCs + H2O2 + laser irradiation had a significant inhibitory effect on 4T1 cells. The strong NIR absorbance of the PEG-Cu2Se HNCs indicates their potential for use in PAI. A strong PA signal was observed at the tumor site after injection of PEG-Cu2Se HNCs, suggesting that the PEG-Cu2Se HNCs can serve as an outstanding agent for PAI. The PEG-Cu2Se HNCs exhibit a strong Fenton-like reaction rate in the presence of H2O2, which can produce a large amount of •OH and significantly improve the therapeutic efficacy of the Fenton-like catalyst to produce •OH, indicating that the mild PT effect with CDT can completely eradicate tumors [41].

Fig. 11.

(a) A schematic illustration of the preparation of PEG-Cu2Se HNCs. (b) Proposed mechanism of PEG-Cu2Se HNCs for PT-enhanced CDT in the NIR-II window. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [41]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. A schematic illustration of the synthesis of PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs (c) and its application in combination therapy (d). Reprinted with permission of Ref. [72]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd.

In another study, An et al. reported Cu2+-doped zeolitic imidazolate framework-8-coated polydopamine (PDA) NPs (PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs) for GSH-triggered and PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 11c, d). PDA NPs were synthesized via solution-phase oxidation and Cu/ZIF-8 was coated on the surface of PDA to achieve highly uniform PDA@Cu/ZIF-8. PDA acts as a PT agent that can produce heat under laser irradiation to generate •OH and deplete GSH, which significantly retards the growth of xenograft tumors. PDA NPs have an average diameter of 50 nm. The temperature of the PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NP solutions increases to 70 °C after 10 min of laser irradiation, indicating their potential as a PT agent. The in vitro anticancer effect of PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs resulted in increased cell death after laser irradiation, implying that the rationally designed PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs for new PTT/CDT treatment can serve as a novel anticancer agent. The synthesized PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs can react with intracellular GSH to simultaneously deplete GSH. In addition, Cu + decomposes H2O2 to produce a large amount of •OH via Fenton-like reactions, which can be further enhanced by the PT effect, causing GSH-controlled ROS generation and GSH depletion in the tumor area. The in vivo PT-enhanced CDT results suggest that PDA@Cu/ZIF-8 NPs exhibit excellent tumor-killing ability [72].

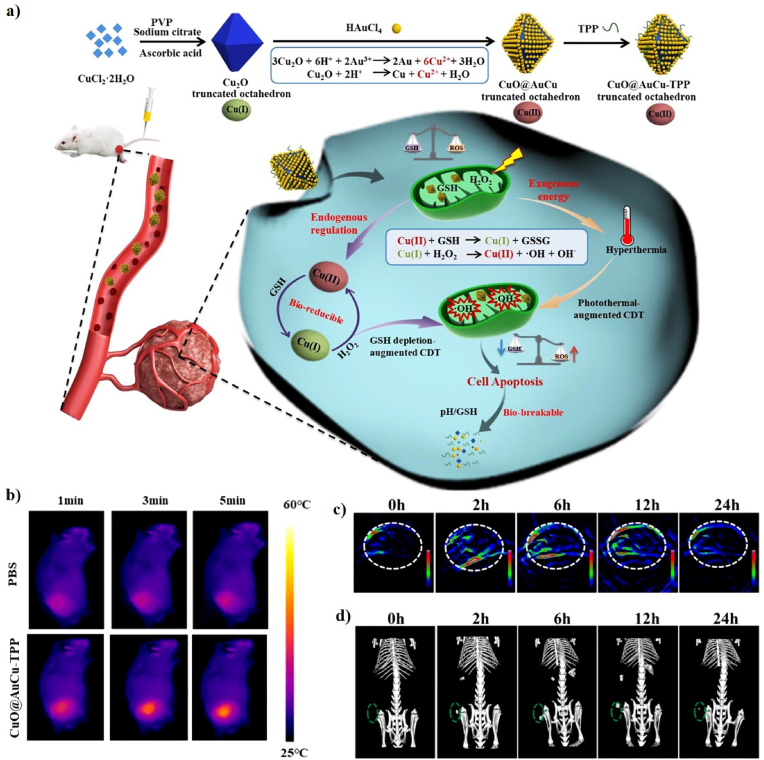

Currently, copper-oxide (Cu2O) nanocrystals have been reported to have a variety of morphologies, including spheres, nanocubes, triangular nanoplates, and octahedrons [[161], [162], [163]]. More interestingly, the truncated octahedron is considered an excellent candidate for the Fenton-like catalytic activity [132]. Similarly, Li et al. developed a triphenylphosphonium (TPP)-conjugated gold-coated copper(II)-based truncated octahedron (CuO@AuCu-TPP) as a Fenton-like catalyst for PA/CT imaging-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 12a). Cu2O was prepared by reducing a solution of copper citrate complexed with ascorbic acid and the Au NPs were then covered on the surface of the Cu2O via a disproportional reaction. Finally, the TPP as a targeting group was conjugated at the end through electrostatic interactions to form CuO@AuCu-TPP. The CuO@AuCu-TPP showed a truncated octahedral structure, with an average particle size of 255 nm and a zeta potential of −7 mV. The PCE (η) of CuO@AuCu-TPP with 808 nm laser irradiation was calculated to be 37.9%, indicating its outstanding PT properties. Cu(II) was reduced to Cu(I) because of the intracellular GSH, which simultaneously depletes GSH, and Cu (I) can react with H2O2 to disrupt the redox balance in the mitochondria via •OH generation and GSH consumption via Fenton-like reactions. The in vitro anticancer efficacy of CuO@AuCu-TPP significantly inhibited HeLa cell viability under laser irradiation, indicating that PT heat can effectively enhance the efficiency of •OH generation. The in vivo synergistic therapeutic efficacy of Au on the surface of CuO@AuCu-TPP showed an excellent PT effect upon laser irradiation, which causes the tumor temperature to increase and enhance the speed of the Fenton-like reaction, thus enabling a synergistic PT effect, Fenton-like reaction, and accurate mitochondrial-targeting ability to achieve strong therapeutic effects (Fig. 12b). In addition, PA and CT images were obtained in mice and strong PA and CT signals at the tumor site were observed 6 h post-injection, indicating that CuO@AuCu-TPP shows great promise for therapeutic application in cancer diagnostics (Fig. 12c, d) [132].

Fig. 12.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthesis of CuO@AuCu-TPP and the therapeutic mechanism of CuO@AuCu-TPP. (b) IR thermal images of mice. In vivo PA (c) and CT (d) images post-injection of CuO@AuCu-TPP. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [132]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd.

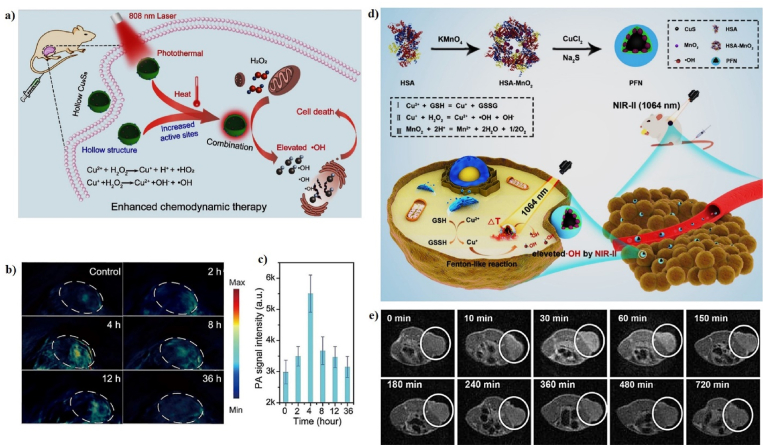

In addition, copper sulfide (CuS) NPs can be used as a theranostic agent because of their PT, PA, and Fenton-like properties [70]. For example, Wang et al. developed hollow and solid copper sulfide NPs (Cu9S8 NPs) as a Fenton-like agent for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 13a). The copper sulfide NPs have a hollow sphere structure with an average diameter of ∼18.05 nm and shell thickness of ∼3.50 nm. The hollow Cu9S8 NPs show excellent chemodynamic treatment effects for cancer, both in vitro and in vivo, due to the •OH generated from endogenous H2O2 under the catalytic conditions of copper ions. Subsequently, the mild temperature generated from the PT effects can effectively improve the CDT efficacy. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with Cu9S8 NPs at various time points and the PA images of the tumor site slowly changed from black to blue over 2–4 h (Fig. 13b, c), suggesting an increase in the signal strength, which can be used to provide useful information for guiding PT-enhanced CDT [64]. In another study, Sun et al. developed a NIR-II PT Fenton-like nanocatalyst (PFN), consisting of human serum albumin (HSA), manganese dioxide (MnO2), and copper sulfide (CuS) for MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 13d). PFN was synthesized using a two-step technique. HAS-encapsulated MnO2 NPs were prepared using a redox reaction and the CuS NPs were deposited via a biomimetic mineralization process to form PFN. CuS NPs are promising Fenton-like nanocatalysts that react with H2O2 to generate •OH for PT-enhanced CDT. The MnO2 NPs decompose into Mn2+, which is a prominent imaging agent for T1-weighted MRI. The PFN generates local heat under 1064 nm laser irradiation, which accelerates the Fenton-like reactions. The particle size of PFN was 22 nm and its zeta potential was −18.7 mV because of the negative charge of CuS. The PCE (η) of PFN was 30.17%, implying that it is a good PT agent. The in vitro anticancer efficacy of PFN + H2O2 + laser irradiation showed the highest level of apoptotic cells, implying synergistic NIR-II PTT and CDT. The tumor temperature of mice injected with PFN gradually reached 55 °C after 5 min under laser irradiation and the treated tumor was completely inhibited without any reoccurrence, implying that the PFN shows superior PT-heating ability and potent antitumor efficiency in vivo. The MR signal in the tumor regions reached its brightest at 30 min post-injection of PFN, indicating the effective accumulation of PFN in tumors and demonstrating their, utility as an activatable MRI contrast agent for cancer therapy (Fig. 13e) [135].

Fig. 13.

(a) A schematic illustration of the fabrication of hollow Cu9S8 NPs for PT-enhanced CDT. In vivo PA images (b) and PA signal (c) of tumor-bearing mice before and after intravenous injection of hollow Cu9S8 NPs. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [64]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd. (d) A schematic illustration of PFN for PT-enhanced CDT. (e) In vivo T1-weight MR images at different time points. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [135]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

3.3. Gold-based nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT

Gold-based nanomaterials are the most well-studied nanomaterials for biomedical applications, such as biosensors, therapy, and multimodal imaging [[164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170]]. Many researchers are currently using gold-based nanomaterials as enzyme mimetics and have greatly expanded the number of new therapeutic applications derived from their enzyme-like functions [171,172]. Gold-based nanomaterials have been used in a variety of research fields in PT-enhanced CDT because of their strong NIR absorption and inherent catalytic properties [137,173]. For example, Fan et al. reported novel nanozymes with a yolk-shell structure in which the gold (Au) NP core was coated with a hollow carbon nanosphere with a porous shell (Au@HCNs) for PT-catalytic therapy. Au NPs have been one of the most widely studied nanozymes in recent years that generate ROS because of their intrinsic enzyme-like activities, and they are also good NIR-absorbing agents. AuNPs were synthesized according to a literature method and then coated with SiO2 using the Stӧber method, yielding Au@SiO2 NPs. PDA was polymerized on the surface of Au@SiO2, yielding Au@SiO2@PDA NPs, which were carbonized under a N2 atmosphere for 2 h at 800 °C and named as Au@HCNs. The Au@HCNs have an average size of 275 ± 0.355 nm and a PCE value (η) of 26.8%. The enzyme-like activity of Au@HCNs can produce ROS, such as •OH and superoxide radicals (•O2−), and PT heat can improve the generation of ROS to accelerate the enzymatic reactions. The in vitro anticancer effect of Au@HCNs significantly inhibits the growth of cancer cells after laser irradiation and generates ROS, inducing cell death. The temperature of Au@HCNs-treated tumors rapidly increases from 33 to 52.9 °C under laser irradiation for 10 min, leading to their complete disappearance without recurrence after treatment. Au@HCNs can react with H2O2 and O2 in the TME to produce toxic ROS, resulting in cell death, which may be enhanced by the mild PT effect [137].

3.4. Other metal oxide- and sulfide-based nanomaterials for PT-enhanced CDT

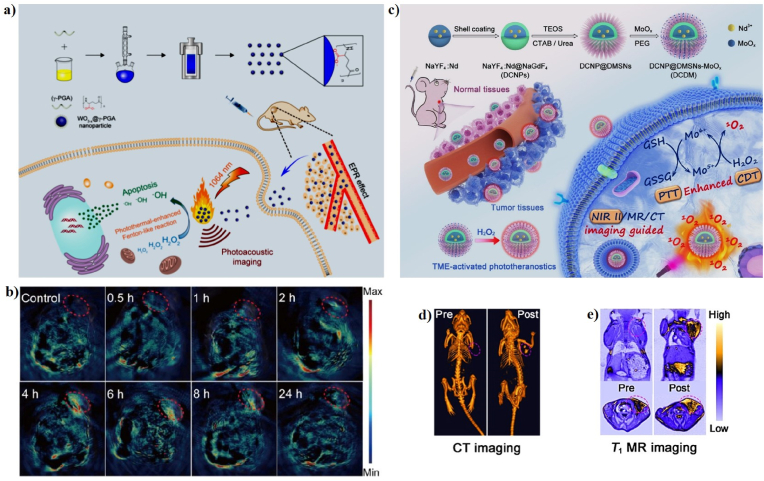

Several transition metals have also been used as Fenton-like agents for PT-enhanced CDT [107,174]. The tungsten trioxide (WO3−x) has been used as a PT material for PTT because of its strong absorption in the NIR region and has also been used as a Fenton-like agent for CDT [107,[175], [176], [177]]. In 2018, Liu et al. successfully prepared ultrasmall tungsten trioxide (WO3−x) NPs, which were then coated with γ-poly-l-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) for PAI and effective PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 14a). The WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs were synthesized via a simple hydrothermal reaction using γ-PGA as a ligand and WCl6 as the tungsten source. The WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs have a monodispersed irregular morphology with an average particle size of 5.73 ± 0.93 nm. The 1064 nm laser PCE (η) of the WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs was 25.8%, as calculated from the heating and cooling curves. More importantly, the Fenton-like reaction occurred for WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs in the presence of H2O2, indicating that the WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs can react with H2O2 to generate a large amount of •OH; this Fenton-like reaction was promoted by the PT effect. Most of the cells were killed in the presence of WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs + H2O2 + laser irradiation, which can be attributed to the in vitro PT-enhanced CDT. The tumors of mice in the presence of WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs + laser irradiation gradually decrease and almost disappear after 18 days, indicating that WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs can cure tumors after laser irradiation. PAI was employed to detect the accumulation of nanomaterials in the tumor areas to guide PT-enhanced CDT. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with the WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs. PA images of the mice were scanned before and after injection at various time points (Fig. 14b). The strongest PA signal was observed at 4 h post-injection, suggesting that the WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs have great potential for use in PAI [24].

Fig. 14.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthesis of WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs for PT-enhanced CDT. (b) In vivo PA imaging of tumor-bearing mice before and post-injection of WO3−x@γ-PGA NPs. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [24]. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. (c) A schematic illustration of the synthesis of DCDMs for PT-enhanced CDT. In vivo CT (d) and MR (e) images of tumor-bearing mice before and post-injection of DCDMs. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [139]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Currently, molybdenum oxide NPs (MoOirst time, the use of biodegradable NPs) have aroused worldwide interest because of their excellent PT conversion efficiency and Fenton-like properties [178]. For instance, Dong et al. developed PEGylated down-conversion NPs (DCNPs) with dendritic mesoporous silica (DMSN) and then loaded ultra-small molybdenum oxide NPs (MoOirst time, the use of biodegradable NPs) as all-in-one nanotheranostic agents (PEG-DCNP@DMSN-MoOirst time, the use of biodegradable NPs) for multimodal imaging-guided PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 14c). DCNP@DMSN had a uniform hexagonal structure with an average diameter of 123 nm. The PCE (η) of PEG-DCNP@DMSN-MoOirst time, the use of biodegradable NPs (DCDMs) was 51.5%, implying that the DCDMs possess excellent PT properties. Mo5+ can efficiently catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to form a considerable amount of singlet oxygen (1O2) in the mildly acidic TME, leading to irreversible cell death. Subsequently, the generated Mo6+ can effectively decrease the levels of GSH in the tumor area, and the GSH depletion and PT effect can further accelerate the generation of 1O2 and enhance CDT. The synergetic PT-enhanced CDT of DCDMs effectively inhibits apoptosis in vitro and killed the tumors in vivo. Moreover, the CT and MR signals of the tumor area 12 h post-injection were obviously higher than those prior to injection, implying that the DCDMs are multimodal imaging contrast agents for clinical diagnosis (Fig. 14d, e) [139].

As a representative manganese dioxide (MnO2)-based Fenton nanocatalyst in CDT, Wang et al. designed a gold@manganese dioxide (Au@MnO2) core-shell nanostructure for PAI/MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT and GSH-triggered CDT. Au@MnO2 has a uniform core-shell structure with an average size of ∼25 nm. The PCE (η) of Au@MnO2 after being triggered by GSH was 23.6%, demonstrating that Au@MnO2 had good PT properties. The GSH-triggered and PT-enhanced CDT of Au@MnO2 can efficiently catalyze the generation of •OH from H2O2 because of the high amount of Mn2+ produced upon the reduction of MnO2 by GSH and the PT effect can accelerate the production of •OH, indicating that Au@MnO2 has promising potential as a GSH-triggered smart theranostic agent for PAI/MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT. The in vitro and in vivo therapeutic effects of Au@MnO2 with laser irradiation show the highest apoptosis and necrosis rates because of the synergistic effect of the GSH-triggered Au@MnO2 agents for PT-enhanced CDT. The complementary effects of MRI and PAI can efficiently enhance the diagnosis of cancer. PA and T1-weighted MR imaging of mice were performed at various time points post-injection of Au@MnO2. The T1-weighted MR signal was observed in the tumor area and the GSH-triggered PAI of Au@MnO2 was similar to that of MRI, indicating that Au@MnO2 has promising potential as a GSH-triggered smart theranostic agent for PAI/MRI-guided PT-enhanced CDT [43].

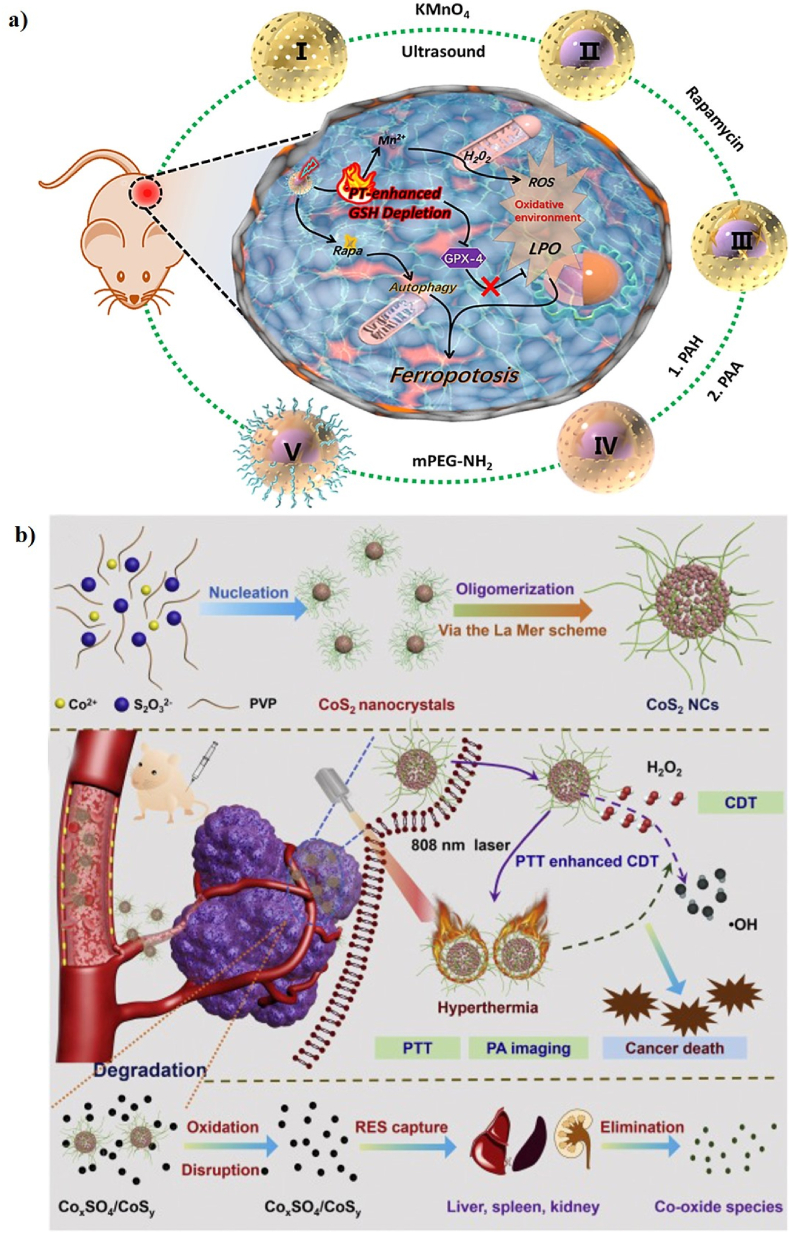

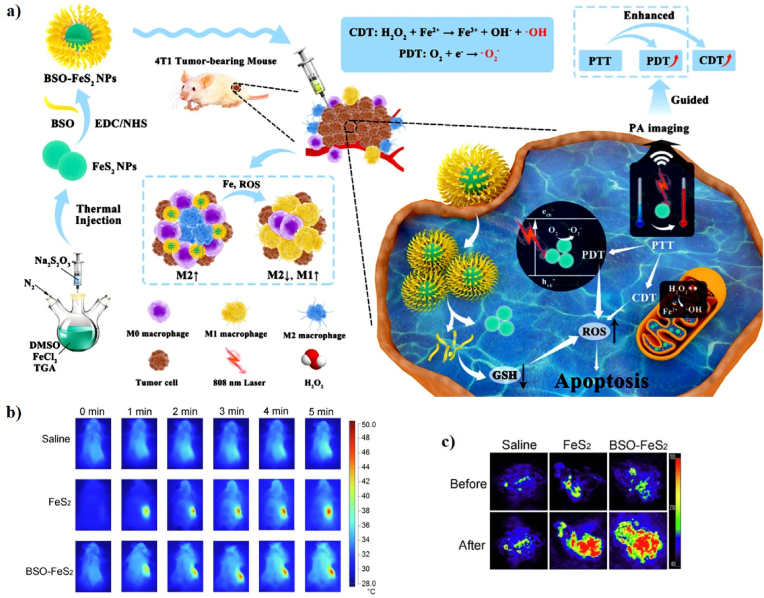

In another similar recent study, An et al. constructed PEG-decorated MnO2@HMCu2−xS nanocomposites (HMCMs), consisting of manganese dioxide (MnO2) and hollow mesoporous copper sulfide (HMCu2−xS), for PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 15a). The particle size of MnO2 was 80 nm. The PCE (η) of HMCM was 22.3%, implying that HMCM has great potential as an ideal PT agent. MnO2 reacts with GSH, converting Mn(IV) to Mn(II) to enhance the Fenton-like reaction with additional •OH produced due to the increased generation of Mn2+ under laser irradiation. The in vitro therapeutic effect of HMCM with laser irradiation showed higher cytotoxicity to MCF-7 cells, which caused higher Mn2+ accumulation in the cells, allowing for the Fenton-like reaction to accelerate endogenous H2O2 for a high level of ROS production. The in vivo anticancer effects of HMCMs with laser irradiation efficiently eliminate tumor growth and showed a high tumor inhibition rate of 75%, demonstrating that HMCMs have superior anticancer efficiency [46]. In addition, Wang et al. developed biodegradable cobalt sulfide (CoS2) nanoclusters (CoS2 NCs) for the PT-enhanced CDT of cancer cells via Fenton-like catalytic activity (Fig. 15b). Cobalt chalcogenides have received a lot of attention in the field of biomedicine because of their high PT properties, biological safety, and catalytic properties. The CoS2 NCs were prepared via a simple one-pot solvothermal method using a cobalt and sulfur source. The CoS2 NCs have a spherical morphology with an average diameter of 19.79 ± 5.2 nm. The PCE (η) of the CoS2 NCs was 60.4%. The CoS2 NCs can generate •OH in the presence of H2O2 and PT heat accelerates the efficacy of the Fenton-like reaction. The in vitro PT-enhanced CDT based on CoS2 NCs was concentration-dependent, which can significantly improve their therapeutic effect on cancer. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were injected with CoS2 NCs and laser-irradiated, resulting in complete inhibition and no reoccurrence. In addition, strong PA signals were observed at the tumor site after injection of CoS2 NCs, suggesting that CoS2 NCs have excellent PAI ability [42].

Fig. 15.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthesis and working mechanisms of HMCMs. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [46]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. (b) A schematic illustration of the fabrication of CoS2 NCs for PT-enhanced CDT. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [42]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd.

4. Combination therapy

Monotherapies such as PTT, CDT, CHT, SDT, PDT, IMT, and ST, have been extensively used in preclinical and clinical studies, and many researchers have reported that monotherapy is not as effective as expected because of the development of resistance and side effects over a long-term period of treatment [179]. Combination therapy commonly refers to the simultaneous co-delivery of drugs or combined-therapeutic strategies in various forms for the effective treatment of cancer [68]. Combination therapy has attracted an increasing amount of clinical attention because of its superior advantages in overcoming the intrinsic drawbacks of monotherapy [90]. The combination of PT-enhanced CDT with CHT, SDT, PDT, IMT, and ST has emerged as a potential alternative to monotherapies due to their synergistic therapeutic effects [99]. In addition, monomodal imaging (e.g., PAI, FLI, MRI, and CT alone) has been widely studied in clinical disease diagnosis, but there are still some short-comings and unsolvable problems that need to be overcome in multimodal imaging (PAI/FLI/MRI/CT multimodal diagnostic imaging) techniques to provide information for the effective diagnosis of disease [180]. Multimodal imaging (PAI/FLI/MRI/CT multimodal diagnostic imaging-guided combination cancer therapy) is also essential for the early stage of diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic effects of the tumor, which play a major role in accurate biomedicine [52,181].

4.1. PT-enhanced CDT with CHT

CHT is a widely accepted method and has been proven successful in cancer treatment in a clinical setting, which is the first-line treatment of patients for the advanced stage of tumors and metastatic tumors [182,183]. CHT has also recently achieved remarkable clinical success in extending the lives of millions of patients, which has several unique advantages such as high efficiency, reliability, reduce pain, and convenience [184]. The use of chemotherapeutic agents is based on the basic principle of highly toxic compounds to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis [185]. Cancer cell apoptosis is also one of the main mechanisms by which chemotherapeutic agents kill cells [186]. However, the major drawbacks of CHT include CHT-resistance, limited dosage, non-specific distribution, low drug levels in the tumor tissues, and severe systemic toxicity, which are responsible for the inefficiency of CHT in patients [[187], [188], [189]]. Hence, minimizing the side effects of CHT agents remains a challenge in the field of cancer CHT. PTT can effectively improve intracellular drug delivery, accelerate drug release, increase drug accumulation at the tumor site, and inhibit drug resistance [190,191]. ROS also plays an important role in the redox balance of biological processes [192]. The high amount of ROS in cancer cells can effectively increase the oxidative damage of cancer cells and enhance the delivery efficiency, thereby resulting in cell death [193]. Therefore, the integration of anticancer drugs and PT-enhanced Fenton-based nanocatalysts into one nanomaterial is highly desirable and PT-enhanced CDT with CHT has demonstrated to be have great potential to overcome the side effects, thus achieving synergistic cancer therapy [194].

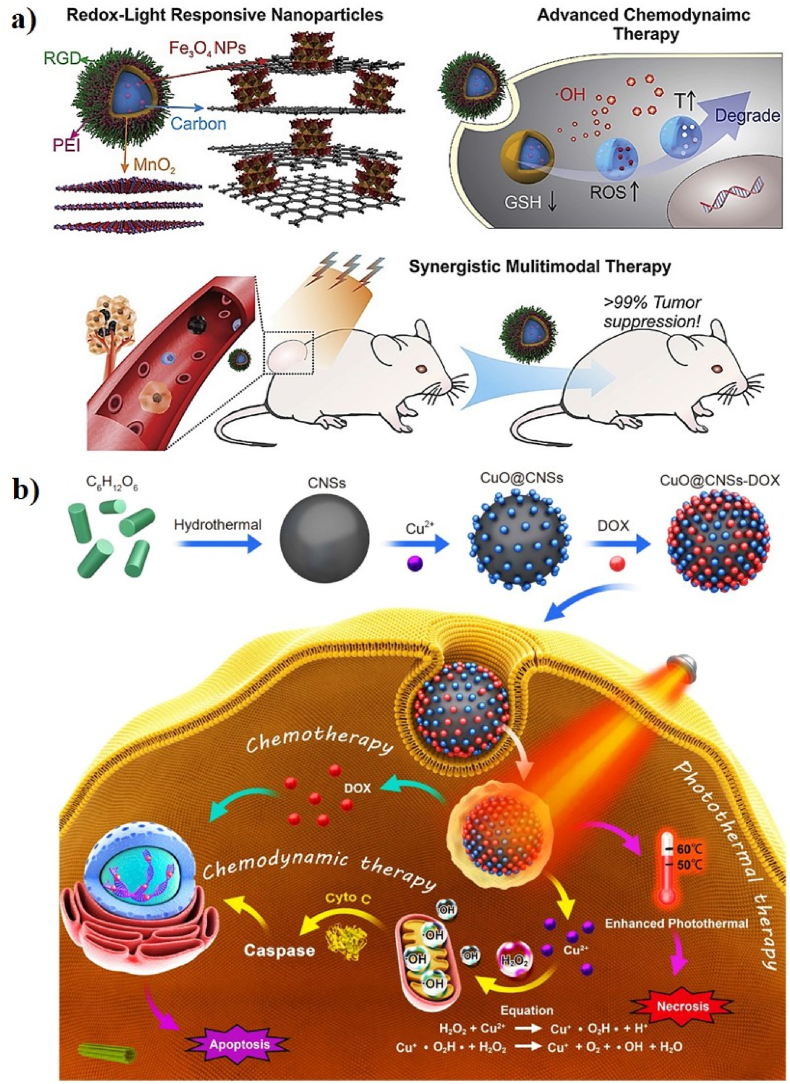

In a similar study, Qi et al. reported a multifunctional carbon dot (CD)-decorated silver (Ag)/gold (Au) bimetallic nanoshell (NS) as a smart nanozyme (CDs-Ag/Au NS, CAANS) for chemo-PTT. The CD-loaded Ag/Au NSs were proven conducive to generating toxic ROS to stimulate CHT. The CAANSs have an average size of 52 nm. Tryptophan (Trp) plays an important role in oxidative stress by inducing the formation of ROS such as superoxide radicals (•O2−), which are decomposed to produce H2O2 in cancerous cells under the PT catalytic process in the presence of CAANSs and effectively kill cancer cells. The apoptosis rate was 95%, suggesting that CAANS can serve as an effective catalytic nanomedicine for cancer therapy [136]. In another study, Wang et al. developed new redox and light-responsive (RLR) NPs with ultra-small iron oxide (Fe3O4) NP-engineered framework comprised of an amorphous hollow carbon matrix core (Fe3O4–C) with nanoflower-like MnO2 loaded with doxorubicin (DOX) for chemo-PT-CDT through a Fenton-like reaction, GSH depletion, and chemo-PT effect (Fig. 16a). The RLR NPs had an average diameter of 200 nm. The PCE (η) of the RLR NPs was 26.8%, which is the most efficient NIR of the PT agent. Ultra-small Fe3O4 NPs release Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions sequentially, which can self-activate the Fenton-like reactivity by catalyzing the conversion of H2O2 into a large number of toxic •OH radicals. This indicates that the acidic nature of the TME can accelerate the Fenton-like reactivity stimulated by the Fe3O4 NPs and enhance the therapeutic efficacy via the ferroptosis pathway. The RLR NPs were programmed to self-activate CDT by reducing the intracellular levels of the antioxidant GSH, accelerating ROS generation, spatiotemporal controllable PTT, and redox-triggered DOX release. The RLR NPs-treated cells have a significantly higher level of ROS after laser irradiation, suggesting the heat production from PTT can accelerate the RLR NPs-based CDT. In addition, the RLR NP-based PTT can also improve the accumulation of DOX in cancer cells for CHT. Tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with FITC-labeled RLR NPs and in vivo fluorescence signals were observed at the tumor site after 2 h. In addition, T1 MRI positive probes (Mn2+) were released, allowing in situ MRI and the MR signals were observed at 1 and 3 h. The in vivo synergistic therapeutic efficacy of the RLR NPs almost stopped tumor growth during the experimental periods, suggesting that the RLR NPs have great potential for use in MRI-guided chemo-PT-enhanced CDT [121].

Fig. 16.

(a) A schematic illustration of the fabrication of RLR NPs for chemo-PT-enhanced CDT. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [121]. Copyright 2019 Elsevier Ltd. (b) A schematic illustration of the synthesis of CuO@CNSs-DOX for chemo-PTT/CDT. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [133]. Copyright 2020 Springer.

In another effort, Jiang and co-workers designed multifunctional doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded copper oxide-decorated carbon nanospheres (CuO@CNSs) for chemo-PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 16b). The CNSs were used as PT agents, which were synthesized via a hydrothermal reaction. CuO was adsorbed on the surface of the CNSs, which can serve as a Fenton-like agent and enhance the PCE of NPs. DOX was finally conjugated on the surface of the CuO@CNSs via electrostatic interactions. The CuO@CNSs have a uniform spherical morphology with an average size of 15 nm. The PCE (η) of the CuO@CNSs was 10.14%, indicating excellent PT properties. The temperature of the CuO@CNS aqueous solution reached up to 60.3 °C, indicating that CuO@CNSs have potential advantages as PT agents. Copper oxide (CuO) can release Cu2+ ions in the TME, which can produce •OH to induce cancer cell apoptosis via Fenton-like reactions. DOX is also released into the TME to kill cancer cells. The CuO@CNSs-DOX + NIR-treated 4T1 cells showed 29% cell apoptosis, indicating that the synergistic PT-enhanced CDT can enhance apoptosis and promote efficacy. The tumors treated with CuO@CNSs-DOX + NIR were completely inhibited, indicating that the synergistic PT-enhanced CDT had a good effect. PAI can provide a non-invasive diagnosis of diseases; the tumor region exhibits a strong PA signal after injection of CuO@CNS, indicating that the CuO@CNSs are ideal PA imaging contrast agents for PAI-guided cancer diagnosis. Multifunctional CuO@CNSs-DOX nanoplatforms have great potential for PAI-guided chemo-PT-enhanced CDT [133].

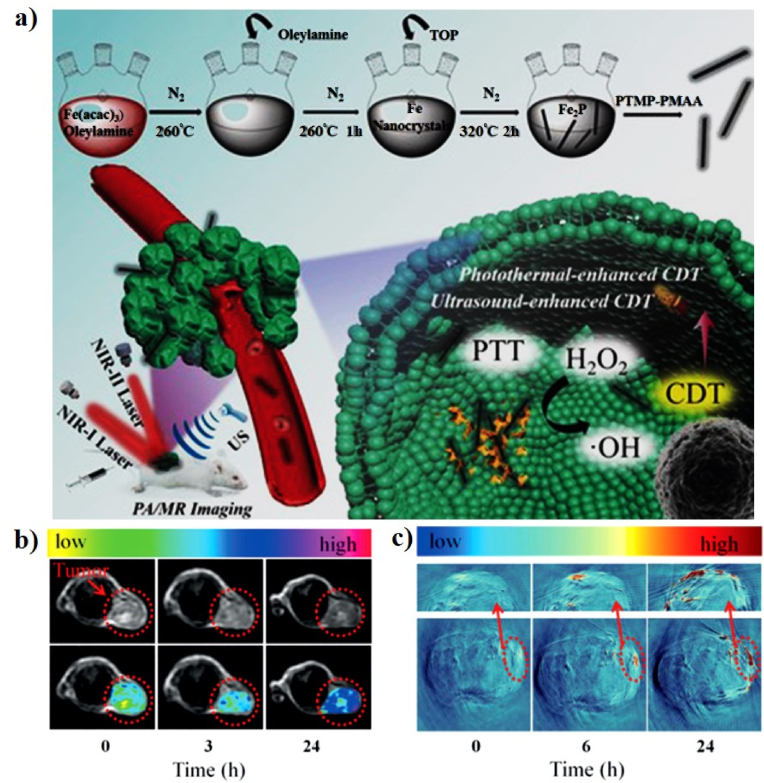

4.2. PT-enhanced CDT with SDT

SDT is a new non-invasive therapy that can eradicate solid tumors using ultrasound (US)-activated sonosensitizers to generate ROS, leading to tumor cell death [[195], [196], [197], [198], [199]]. Although its principle is similar to PDT, SDT is an emerging US-based cancer therapeutic method and is expected to be highly efficient because of its deeper penetration into the tumor site [[200], [201], [202]]. US can penetrate much deeper by several centimeters than PDT to trigger ROS generation and can therefore overcome the major problem of the deep penetration barrier of PDT [203,204]. PT-enhanced CDT with SDT has been used for high-efficiency cancer therapy [198]. For example, Liu et al. reported biocompatible PTMP-PMAA-modified ferrous phosphide (Fe2P) nanorods (FP NRs) as an “all-in-one” Fenton-like agent for ultrasound (US)- and PT-enhanced CDT (Fig. 17a). Fe2P was synthesized via a high-temperature method and PTMP-PMAA was coated onto the surface of Fe2P via a ligand exchange method to enhance their biocompatibility and hydrophilicity. The FP NRs have a rod-like morphology with an average size of 180 nm. The PCE (η) of the FP NRs was 56.6% upon irradiation at 1064 nm, indicating their outstanding PT conversion effect. The FP NRs generate heat under 1064 nm laser irradiation, which effectively enhances the production of •OH. The conversion of Fe3+ to Fe2+ was accelerated by US and the Fe2+ produced further reacts with H2O2 to generate more toxic •OH. Taken together, US and PT heat can effectively enhance the production of ROS by the FP NRs, allowing the application of FP NRs in PT-enhanced CDT with SDT in vitro and in vivo. HeLa cell-treated with FP NRs under the US and 1064 nm laser irradiation exhibit more dead cells, suggesting that the combination of PT-enhanced CDT and SDT shows outstanding anticancer effects. U14 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with the FP NRs. The T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 17b) and PA signals (Fig. 17c) of the tumor were enhanced after 24 h, suggesting that the FP NRs can accumulate at the tumor site through the EPR effect. Tumors were fully inhibited after US and1064 nm laser irradiation, implying that the FP NRs have a good PT-enhanced CDT with SDT effect. Hence, FP NRs can serve as dual-modality MRI/PAI agents to accurately diagnose tumors and provide precise information for US- and PT-enhanced CDT. The synergistic ultrasound- and PT-enhanced CDT can cause cancer cell death in vitro and fully inhibit tumors in vivo, which indicates their remarkable anticancer activity [48].

Fig. 17.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthesis of FP NRs for US/PT-enhanced CDT. In vivo MR (b) and PA (c) images of tumor-bearing mice. Reprinted with permission of Ref. [48]. Copyright 2019 Wiley.

4.3. PT-enhanced CDT with PDT