Abstract

Background

Combination treatments with immune-checkpoint inhibitor and antiangiogenic therapy have the potential for synergistic activity through modulation of the microenvironment and represent a notable therapeutic strategy in recurrent ovarian cancer (ROC). We report the results of camrelizumab (an anti-programmed cell death protein-1 antibody) in combination with famitinib (a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor) for the treatment of platinum-resistant ROC from an open-label, multicenter, phase 2 basket trial.

Methods

Eligible patients with platinum-resistant ROC were enrolled to receive camrelizumab (200 mg every 3 weeks by intravenous infusion) and oral famitinib (20 mg once daily). All patients had disease progression during or <6 months after their most recent platinum-based chemotherapy. Primary endpoint was confirmed objective response rate (ORR) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1 based on investigator’s assessment. Secondary endpoints included disease control rate (DCR), duration of response (DoR), time to response (TTR), progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), 12-month OS rate and safety profile.

Results

Of the 37 women enrolled, 11 (29.7%) patients had primary platinum resistant, 15 (40.5%) patients had secondary platinum resistant and 11 (29.7%) patients had primary platinum refractory disease. As the cut-off date of April 9, 2021, nine (24.3%) patients had achieved a confirmed objective response, the ORR was 24.3% (95% CI, 11.8 to 41.2) and the DCR was 54.1% (95% CI, 36.9 to 70.5). Patients with this combination regimen showed a median TTR of 2.1 months (range, 1.8–4.1) and a median DoR of 4.1 months (95% CI, 1.9 to 6.3). Median PFS was 4.1 months (95% CI, 2.1 to 5.7), and median OS was 18.9 months (95% CI, 10.8 to not reached), with the median follow-up duration of 22.0 months (range, 12.0–23.7). The estimated 12-month OS rate was 67.2% (95% CI, 49.4 to 79.9). The most common ≥grade 3 treatment-related adverse events were hypertension (32.4%), decreased neutrophil count (29.7%) and decreased platelet count (13.5%). One (2.7%) patient died of grade 5 hemorrhage that was judged possibly related to study treatment by investigator.

Conclusion

The camrelizumab with famitinib combination appeared to show antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients with platinum-resistant ROC with an acceptable safety profile. This combination might provide a novel alternative treatment strategy in platinum-resistant ROC setting and warranted further exploration.

Trial registration number

Keywords: clinical trials, phase II as topic, drug therapy, combination, genital neoplasms, female, immunotherapy

Background

Majority of women with ovarian cancer (OC) have advanced disease at diagnosis and are treated with cytoreductive surgery and/or platinum-based chemotherapy.1 Despite the evolutions of surgical techniques and chemotherapy strategies, most patients with advanced disease still experience recurrence that ultimately brings about fatality as a result of the emergence of chemotherapy resistance, particularly resistance to platinum. Women with platinum-resistant recurrent OC (ROC) continue to have a poor prognosis with limited treatment options.2 3 Therefore, there is a clear unmet need to improve outcomes in this subset of patients.

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized the treatment paradigm of several solid tumors, and their clinical applications in multiple tumor types are still under investigation. Nevertheless, different tumor types present various degree of sensitivity to immunotherapy. Despite a clear rational for investigating immunotherapy in OC,4–6 initial over-optimism about ICI monotherapy in the OC treatment has been tempered by the modest efficacy shown in previous clinical trials.7–9 Therefore, efforts to improve antitumor activity have focused on combination immunotherapy with targeted agents in recent years. Overall, the combination of immune checkpoint blockade and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition is a worthwhile strategy for circumventing known resistance mechanisms in OC.10 11 VEGF signaling induces both local and systemic immune mitigating effects, including the release of immunosuppressive cytokines, recruitment of regulatory T cells, and inhibition of dendritic cell maturation. VEGF signaling is also implicated in an increase of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) expression by T cells, which allows tumor cells to evade detection by the immune system.12 To date, a single arm phase 2 trial recruited 38 patients and evaluated combination treatment with nivolumab and bevacizumab, of which only 18 (47%) had platinum-resistant disease.13 The objective response rate (ORR) with this combination regimen was 16.7% (95% CI, 3.6 to 41.4) in platinum-resistant patients, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 7.7 months (95% CI, 4.7 to not reached (NR)),13 meaning that further exploration of ICIs plus anti-angiogenetic agents in platinum-resistant ROC is warranted.

Camrelizumab binds to the PD-1 receptor and blocks its interaction with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and PD-L2, thus blocking immunosuppression mediated by the PD-1 pathway, and has presented promising antitumor activities across a broad range of advanced malignant cancers.14 15 The sunitinib analog famitinib (famitinib malate) is a novel and potent multitarget receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) against VEGFR, C-Kit, and PDGFR, and has antitumor activity in a range of solid tumors.16 17 Therefore, we conducted a basket phase 2 study to evaluate the antitumor activity and safety of camrelizumab combined with famitinib in patients with advanced genitourinary or gynecological cancers.18–21 Herein, we reported the results of camrelizumab plus famitinib in patients with platinum-resistant ROC.

Methods

Study design and patients

This is an open-label, phase 2 basket study (ClinicalTrials.gov) conducted in 25 medical centers in China, and the study design of this trial had been reported previously.18–21 Here, we present the data from the cohort 3 (patients with platinum-resistant ROC). Briefly, eligible patients had histologically confirmed epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube cancer or peritoneal cancer. Disease progression occurred during or <6 months after their most recent platinum-based chemotherapy. No more than one non-platinum-based regimen was permitted to be conducted between their penultimate and last platinum-based chemotherapy. Other anticancer therapies after the completion of the last platinum-based regimen (except endocrine treatment or poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor as maintenance therapy) were not allowed. Other key eligibility criteria included age 18–75 years; patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score of 0 or 1; at least one measurable lesion per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1; estimated life expectancy of at least 12 weeks; and enough renal, hepatic and hematologic function. Key exclusion criteria included prior therapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents or famitinib; applications of immunosuppressant or systemic hormone within 2 weeks of receiving study treatment; another malignancy within 5 years; known active or a history of autoimmune disease; poorly controlled hypertension or active infection.

Procedures

For this combination regimen, all enrolled patients with platinum-resistant ROC received camrelizumab 200 mg by intravenous infusion (over 30 min) once every 3 weeks (Q3W) on Day 1 of each 21-day cycle and oral famitinib with an initial dose of 20 mg once daily (QD). Tolerability was evaluated during the period from the first administration to two treatment cycles of the first recruited 12 patients in cohorts 1–5. If clinically significant toxicity (online supplemental table S1) was reported in no less than 4 of the first enrolled 12 patients or adverse events (AEs) leading to famitinib dose reduction occurred in ≥30% enrolled patients during the tolerability observation period, the initial doses for subsequent enrolled patients would be adjusted to camrelizumab 200 mg Q3W in combination with famitinib 15 mg QD. As of June 1, 2019, only 1 of the first 12 patients met the criteria of the clinically significant toxicities (<4/12 patients) and 2 (4.1%) of all the enrolled 49 patients had AEs leading to famitinib dose reduction.20 Therefore, camrelizumab 200 mg Q3W in combination with famitinib 20 mg QD was well-tolerated and applied as the initial doses for subsequently enrolled patients.

jitc-2021-003831supp001.pdf (106KB, pdf)

Study treatment was continued until intolerable toxicity, confirmed disease progression per RECIST V.1.1, investigator decision, withdrawal of consent, cumulative longest camrelizumab exposure of 24 months, poor compliance or loss to follow-up, whichever occurred first. Treatment beyond confirmed disease progression was permitted only in patients with clinically stable condition at the discretion of the investigator. To manage adverse events, treatment interruption for camrelizumab (camrelizumab should be permanently discontinued if immune-mediated AEs was not resolved within 12 weeks of the last dose) or famitinib was allowed; but dose reductions of camrelizumab were not permitted.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was confirmed ORR per RECIST V.1.1, defined as percentage of patients who had a confirmed complete response (CR) or a partial response (PR) as best overall response based on investigator’s assessment. The secondary endpoints included disease control rate (DCR, defined as proportion of patients who had a CR, PR or durable stable disease (SD) (defined as SD ≥6 weeks) as best overall response), duration of response (DoR, defined as the time from the first documented evidence of CR or PR until disease progression or death due to any cause, whichever occurred first), time to response (TTR, defined as the time from the start of study treatment to the first documented confirmed response (CR or PR) per RECIST V1.1), PFS (defined as the time from treatment initiation to the first documented disease progression per RECIST V.1.1 or death due to any cause, whichever occurred first), overall survival (OS, defined as the time from the date of study treatment initiation until death due to any cause), 12-month OS rate, and safety profile. Exploratory endpoints included tumor responses per RECIST V.1.1 assessed by investigator according to platinum resistant status and PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) expression status.

Assessments

Tumor response assessments were performed at baseline and then every three cycles by investigator according to the RECIST V.1.1. CR or PR was required to be confirmed at least 4 weeks after the first response. The first documented disease progression was required to be confirmed at 4–6 weeks beyond progression, except rapid radiological progression and/or clinical progression. For those who discontinued study treatment without radiological disease progression, tumor response assessments were conducted every 3 months until documented disease progression, or initiation of first subsequent anticancer therapy or study completion, whichever occurred first. Patients were followed for survival status every 2 months until death.

Safety was monitored with vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiograms, laboratory tests and AE reports. Patients were monitored for AEs until 30 days after the last dose of study treatment (serious AEs and treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were collected until 90 days after the last dose of the study treatment), and all AEs were graded according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, V.4.03.

In this trial, platinum resistant status was further classified according to response to prior anticancer treatments. Primary platinum resistance was defined as disease progression occurring ≥2 months and <6 months after completing first-line platinum therapy, secondary platinum resistance was defined as progression ≥6 months after completing first-line platinum-based chemotherapy but <6 months after completing second-line or later-line platinum-based chemotherapy and primary platinum refractory was defined as progression <2 months or no response during the first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

The PD-L1 CPS was centrally tested using fresh biopsy or archival tumor tissues by PD-L1 immunohistochemistry 22C3 pharmDx test (Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA). The PD-L1 expression level was determined using CPS, defined as the number of PD-L1-positive cells (tumor cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes) divided by the total number of tumor cells multiplied by 100. PD-L1 positivity was defined as CPS≥1.

Statistical analyses

The sample size for cohorts 1–5 of two-stage design was estimated using Lin and Shih’s method.22 For cohort 3 presented here, an ORR of 15% was considered ineffective, 25% was considered low desirable response, and 35% was considered high desirable response. Assuming ORR as specified, a power of 80% for a high desirable response and 70% for a low desirable response, and a two-sided α level of 0.1, the number of patients required would be 22 in stage 1, cohort 3 would have a minimum of 33 and a maximum of 53 patients depending on results in stage 1.

If there were no more than 2 responders out of 22 patients in the stage 1, study treatment was considered ineffective and enrollment would be terminated. If there were 3–6 responders, enrollment would be extended to 53 at stage 2; if there were no less than 7 responders, enrollment would be extended to 33 at stage 2. Study treatment was considered effective if at least 12 responders of 53 patients or at least 8 responders of 33 patients were observed.

All patients who received at least one dose of study treatment were included in the full analysis set (FAS), and patients who received at least one dose of study treatment and had at least one post baseline safety evaluation were included in the safety analysis. ORR and DCR with 95% CIs were calculated using the exact method based on binomial distribution (Clopper-Pearson method). Time-to-event endpoints were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the corresponding 95% CIs for median were calculated based on Brookmeyer-Crowley method. The 6-month, 9-month and 12-month OS rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and 95% CIs were calculated using the log–log transformation according to normal distribution approximation with back transformation to CIs on the untransformed scale.

Results

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Between April 19, 2019, and April 9, 2020, a total of 37 patients with platinum-resistant ROC received the regimen of camrelizumab plus famitinib. The median age of patients was 52 years (range, 35–69). Three (8.1%) patients had an ECOG PS of 0, whereas 33 (89.2%) patients had an ECOG PS of 1. The most commons locations of metastases were lymph node (29 patients, 78.4%), peritoneum (21 patients, 56.8%) and liver (n=13, 35.1%). The most common tumor histologic type was high-grade serous carcinoma (22 patients, 59.5%). All patients were pretreated with systemic therapies, and 6 (16.2%) patients received no less than five prior systemic treatments. Six (18.2%) patients had previously received bevacizumab treatment. Prior to this combination regimen, all patients had received standard platinum-based chemotherapy and disease progression occurred during or <6 months after their most recent platinum-based chemotherapy. Of them, 11 (29.7%) patients had primary platinum resistant, 15 (40.5%) patients had secondary platinum resistant and 11 (29.7%) patients had primary platinum refractory disease, respectively. The demographics and baseline characteristics of patients are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients (n=37) |

| Age, years, median (range) | 52 (35–69) |

| <65 | 33 (89.2) |

| ≥65 | 4 (10.8) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 3 (8.1) |

| 1 | 33 (89.2) |

| Tumor type | |

| Ovarian carcinoma | 33 (89.2) |

| Fallopian tube carcinoma | 4 (10.8) |

| FIGO stage at first diagnosis | |

| I | 2 (5.4) |

| II | 6 (16.2) |

| III | 24 (64.9) |

| IV | 5 (13.5) |

| Location of metastases | |

| Lymph node | 29 (78.4) |

| Peritoneum | 21 (56.8) |

| Liver | 13 (35.1) |

| Spleen | 7 (18.9) |

| Abdominal cavity | 6 (16.2) |

| Lung | 5 (13.5) |

| Number of lines of prior systemic therapy | |

| 1 | 4 (10.8) |

| 2 | 11 (29.7) |

| 3 | 10 (27.0) |

| 4 | 6 (16.2) |

| ≥5 | 6 (16.2) |

| Platinum resistant status* | |

| Primary platinum resistant | 11 (29.7) |

| Secondary platinum resistant | 15 (40.5) |

| Primary platinum refractory | 11 (29.7) |

| Previous bevacizumab use | 6 (18.2) |

| Histologic type | |

| Serous adenocarcinoma | |

| High‐grade | 22 (59.5) |

| Low-grade | 1 (2.7) |

| Unknown | 5 (13.5) |

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 1 (2.7) |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 1 (2.7) |

| Other epithelial ovarian cancer | |

| High-grade adenocarcinoma | 5 (13.5) |

| Adenocarcinoma (not otherwise specified) | 2 (5.4) |

| PD-L1 expression †, n (%) | |

| PD-L1 CPS≥1 | 8 (21.6) |

| PD-L1 CPS<1 | 11 (29.7) |

| Unknown | 18 (48.6) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

*Patients were categorized as primary platinum resistance (disease progression occurring ≥2 months and <6 months after completing first-line platinum therapy), secondary platinum resistance (progression ≥6 months after completing first-line platinum-based chemotherapy but <6 months after completing second-line or later-line platinum-based chemotherapy) and primary platinum refractory (progression <2 months or no response during the first-line platinum-based chemotherapy).

†Mandatory fresh biopsy or archival tissue for PD-L1 expression was not requested at enrollment.

CPS, Combined Positive Score; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

At the cut-off date of April 9, 2021, all 37 patients discontinued treatment, with the median follow-up duration of 22.0 months (range, 12.0–23.7). The major reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (radiographic or clinical, 33 patients, 89.2%), as shown in figure 1. One (2.7%) patients who had radiological progressive disease (PD) received continued treatment at investigator’s discretion.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram of cohort 3 (N=37).

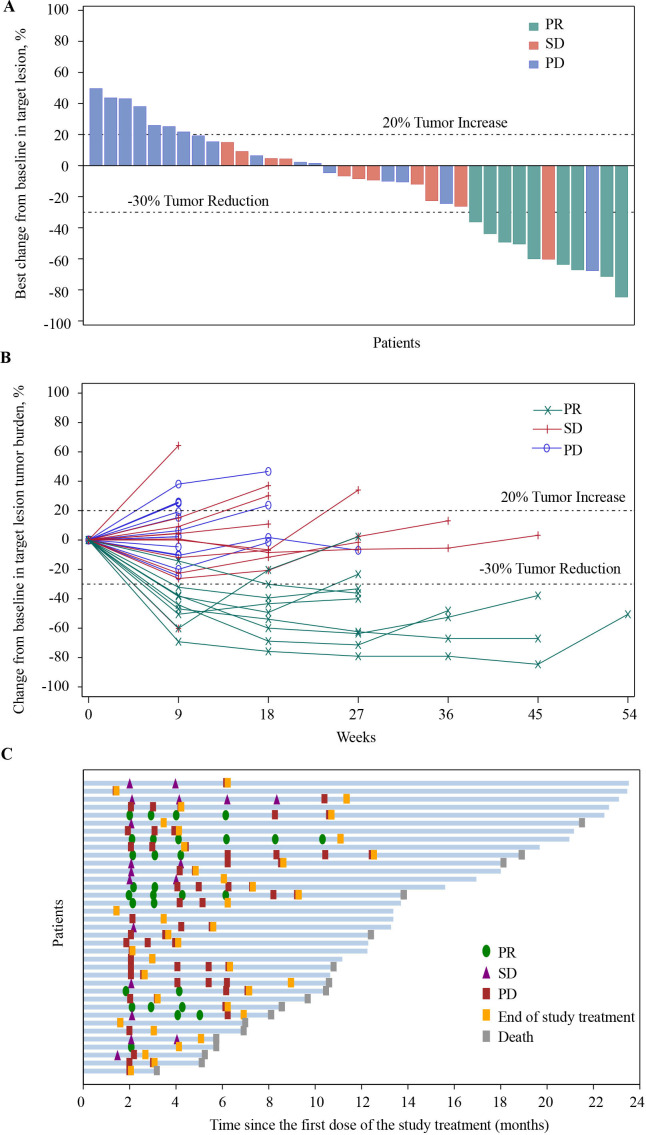

Antitumor activity in all patients

Of the 37 patients in the FAS, no patient achieved a CR, 9 (24.3%) patients had a PR, and 11 (29.7%) patients had an SD. The confirmed ORR was 24.3% (95% CI, 11.8 to 41.2) and the DCR was 54.1% (95% CI, 36.9 to 70.5) in patients with camrelizumab plus famitinib (table 2). Overall, 21 (56.8%) patients achieved a shrinkage of their target lesions from the baseline (figure 2A). The decreased tumor burden was maintained over several assessments (figure 2B). In patients who experienced a response, the median TTR was 2.1 months (range, 1.8–4.1) and median DoR was 4.1 months (95% CI, 1.9 to 6.3; figure 2C), respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of response and survival data

| Variables | All patients N=37 |

| Best overall response, n (%) | |

| Complete response | 0 |

| Partial response | 9 (24.3) |

| Stable disease ≥6 weeks | 11 (29.7) |

| Progressive disease | 17 (45.9) |

| Not evaluable | 0 |

| ORR, % (95% CI) | 24.3 (11.8 to 41.2) |

| DCR, % (95% CI) | 54.1 (36.9 to 70.5) |

| Time to response, months, median (range) | 2.1 (1.8 to 4.1) |

| Duration of response, months, median (95% CI) | 4.1 (1.9 to 6.3) |

| Progression-free survival, months, median (95% CI) | 4.1 (2.1 to 5.7) |

| Overall survival, months, median (95% CI) | 18.9 (10.8 to NR) |

| 6-month rate (95% CI) | 89.2 (73.7 to 95.8) |

| 9-month rate (95% CI) | 78.4 (61.4 to 88.5) |

| 12-month rate (95% CI) | 67.2 (49.4 to 79.9) |

DCR, disease control rate; NR, not reached; ORR, objective response rate.

Figure 2.

Antitumor activity of camrelizumab plus famitinib in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. Responses were assessed by investigator per RECIST V.1 for all 37 patients. (A) Best change of target lesions from baseline in each patient. (B) Percentage change from baseline in target lesion tumor burden over time. (C) Treatment exposure and duration of tumor response in responders. PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease;

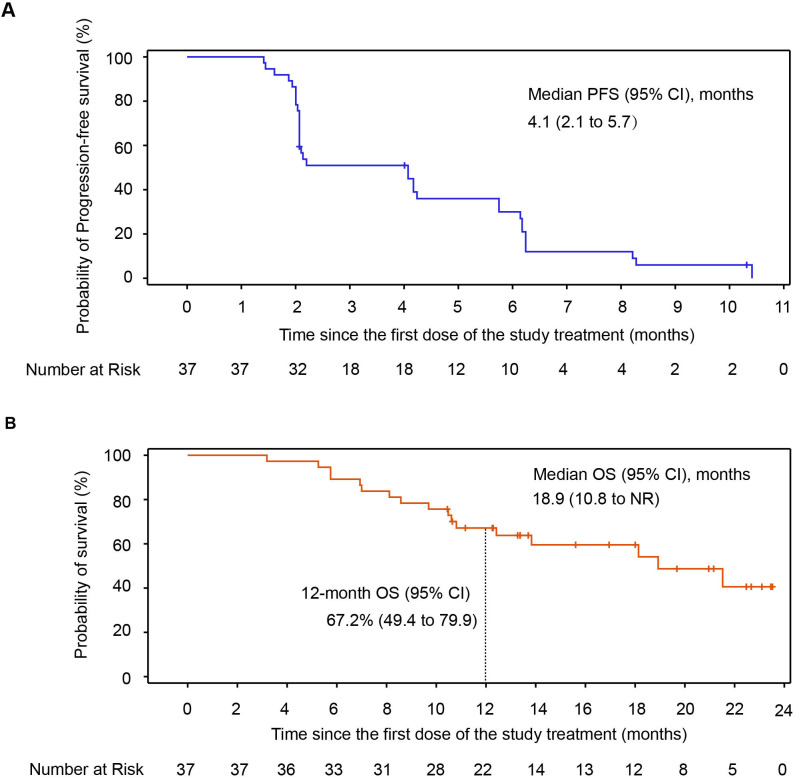

As of data cut-off, 34 (91.9%) patients had PFS events (documented PD or death), and the median PFS was 4.1 months (95% CI, 2.1 to 5.7; figure 3A). A total of 17 (45.9%) patients died, the median OS was 18.9 months (95% CI, 10.8 to NR) with the median follow-up duration of 22.0 months (range, 12.0–23.7), and the estimated 6-month, 9-month and 12-month OS rates were 89.2% (95% CI, 73.7 to 95.8), 78.4% (95% CI, 61.4 to 88.5) and 67.2% (95% CI, 49.4 to 79.9) with this combination regimen, respectively (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

OS and PFS in all patients of cohort 3. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS. NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Anti-tumor activity in subgroup by platinum resistant status

Antitumor activity outcomes by platinum resistant status are presented in online supplemental table S2. The ORR was 36.4% (95% CI, 10.9 to 69.2) in the 11 with primary platinum resistant disease versus 13.3% (95% CI, 1.7 to 40.5) in the 15 patients with secondary platinum resistant disease versus 27.3% (95% CI, 6.0 to 61.0) in the 11 patients with primary platinum refractory disease, respectively. In addition, the DCR was 72.2% (95% CI, 39.0 to 94.0), 40.0% (95% CI, 16.3 to 67.7) and 72.7% (95%CI, 39.0 to 94.0) in patients with primary platinum resistant disease, secondary platinum resistant disease and primary platinum refractory disease, respectively.

Antitumor activity in subgroup by PD-L1 expression

Antitumor activity outcomes by PD-L1 expression are summarized in online supplemental table S3. Tumor PD-L1 expression was available in 19 (51.4%) patients, including 8 patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and 11 patients with PD-L1 CPS <1. The ORR was 50.0% (95% CI, 15.7 to 84.3) in PD-L1 CPS ≥1 versus 18.2% (95% CI, 2.3 to 51.8) in PD-L1 CPS <1. In patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and PD-L1 CPS <1, the DCR was 62.5% (95% CI, 24.5 to 91.5) versus 54.5% (95% CI, 23.4 to 83.3), respectively.

Safety

All the 37 patients were included in the safety analysis. The median cycle of camrelizumab was 6 (range, 2–19), and the median relative dose intensity (defined as the ratio of the delivered dose intensity to the standard dose intensity) was 90.9% (range, 50.0–100.0). The median exposure of famitinib was 18.1 weeks (range, 5.9–54.4), and the median relative dose intensity was 90.5% (range, 44.8–100.0).

All patients experienced at least one TRAE (table 3), and the most common TRAEs of any grade were decreased neutrophil count (30 patients, 81.1%), decreased white blood cell count (29 patients, 78.4%), decreased platelet count (26 patients, 70.3%) and hypertension (24 patients, 64.9%). Thirty (81.1%) patients experienced TRAEs of grade 3 or higher, and the most common ≥grade 3 TRAEs were hypertension (12 patients, 32.4%), decreased neutrophil count (11 patients, 29.7%) and decreased platelet count (5 patients, 13.5%). Reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial proliferation (RCCEP), a common and self-resolving TRAE attributed to camrelizumab monotherapy, was reported in 5.4% of patients (n=2) receiving this combination regimen, with no grade 3 or higher events reported.

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events

| TRAEs, n (%) | All patients (N=37) | |

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| Any TRAE | 37 (100.0) | 30 (81.1) |

| TRAEs leading to camrelizumab discontinuation | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) |

| TRAEs leading to famitinib discontinuation | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.4) |

| TRAEs leading to camrelizumab interruption | 8 (21.6) | 5 (13.5) |

| TRAEs leading to famitinib interruption | 30 (81.1) | 24 (64.9) |

| TRAEs leading to famitinib dose reduction | 7 (18.9) | 4 (10.8) |

| Treatment-related SAEs | 5 (13.5) | 5 (13.5) |

| Any grade TRAEs occurring in at least 20% of patients | ||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 30 (81.1) | 11 (29.7) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 29 (78.4) | 4 (10.8) |

| Platelet count decreased | 26 (70.3) | 5 (13.5) |

| Hypertension | 24 (64.9) | 12 (32.4) |

| Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 21 (56.8) | 2 (5.4) |

| Anemia | 17 (45.9) | 3 (8.1) |

| Proteinuria | 17 (45.9) | 0 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase increased | 15 (40.5) | 3 (8.1) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 15 (40.5) | 2 (5.4) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 14 (37.8) | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 13 (35.1) | 1 (2.7) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 11 (29.7) | 1 (2.7) |

| Diarrhea | 9 (24.3) | 1 (2.7) |

| Occult blood positive | 9 (24.3) | 0 |

| Plateletcrit decreased | 8 (21.6) | 1 (2.7) |

| Weight decreased | 8 (21.6) | 0 |

TRAEs, treatment-related adverse events; SAEs, serious adverse events.

Only one (2.7%) patient discontinued camrelizumab owing to intestinal obstruction. Three (8.1%) patients discontinued famitinib because of TRAEs that were intestinal obstruction, small intestinal perforation, peritonitis and decreased white blood cell count (one patient, 2.7% for each). TRAEs leading to dose modification are indicated in online supplemental table S4. TRAEs led to dose interruption of camrelizumab in 8 (21.6%) patients, with decreased platelet count (4 patients, 10.8%) occurring in more than one patient. Thirty (81.1%) patients experienced at least one TRAE leading to famitinib interruption, mainly including hypertension (11 patients, 29.7%), decreased neutrophil count (9 patients, 24.3%), decreased platelet count (6 patients, 16.2%) and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (4 patients, 10.8%). TRAEs led to dose reduction of famitinib in 7 (18.9%) patients, with decreased platelet count (2 patients, 5.4%) occurring in more than one patient.

Immune-mediated AEs of any grade occurred in 12 (32.4%) patients regardless of attribution (online supplemental table S5), with the most frequent being hypothyroidism (5 patients, 13.5%), hyperthyroidism (3 patients, 8.1%) and diarrhea (3 patients, 8.1%).

Treatment-related serious AEs of grade 3 or higher were reported in 5 (13.5%) patients (online supplemental table S6), included decreased platelet count (2 patients, 5.4%) and peritonitis, staphylococcal infection, decreased white blood cell count, intestinal obstruction, small intestinal perforation, decreased appetite, bile duct stone, bile duct stenosis and hemorrhage (one patient, 2.7% for each). One patient (2.7%) occurred decreased platelet count after study treatment discontinuation due to intestinal obstruction induced by tumor progression. The decreased platelet count was progressively aggravated from grade 1 to grade 3 within 3 days because she gave up further active therapy. Finally, this patient died of grade 5 hemorrhage. Although the investigator believed that the main cause of death should be attributed to the intestinal obstruction caused by tumor progression and patient’s refusal of treatment, the delayed effects of study treatment could not be completely ruled out, therefore, this AE was judged possibly related to study treatment.

Discussion

There are several trials of dual inhibition of VEGF signaling and immune checkpoint pathways in ROC have been published,13 23 however, still limited data is available thus far in those with platinum-resistant ROC. In our phase 2 trial, the combination regimen of camrelizumab plus famitinib achieved an ORR of 24.3% (95% CI, 11.8 to 41.2) in patients with platinum-resistant ROC. Although direct comparisons might be challenging due to different study designs and population enrichment across trials, the ORR with camrelizumab plus famitinib in patients with platinum-resistant ROC was numerically superior to that of PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy (nivolumab, pembrolizumab or avelumab, ORR: 4%–15%)8 9 24 25 in patients with advanced ROC and chemotherapy alone (11.8%) in patients with platinum-resistant ROC,26 and comparable to other combination therapies, including bevacizumab plus chemotherapy (27.3%),26 nivolumab plus bevacizumab (16.7%)13 and avelumab plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) (13%)27 in patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ROC. The ORR with this combination regimen further elucidates the possible synergistic or additive effects to enhance the antitumor activities of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor and antiangiogenic agent.

Due to lack of biopsy or archival tissue at the time of enrollment, 48.6% patients have unknown PD-L1 status in our phase 2 trial, and patients with PD-L1 positive tumors (PD-L1 CPS≥1) had numerically higher ORR compared with patients with PD-L1 negative tumors (50.0% vs 18.2%). Considering limited number of available PD-L1 status and potential selection or information bias, the findings in this trial are difficult to interpret. The results observed from KEYNOTE-100 trial 9 proposed that PD-L1 expression might be associated with improved treatment efficacy. However, better response with nivolumab plus bevacizumab was observed in patients with PD-L1 negative tumors13 or no correlation of activity with PD-L1 expression was reported in JAVELIN 100 trial.24 The ORR was 36.4%, 13.3% and 27.3% in patients with primary platinum-resistant disease, secondary platinum-resistant disease and primary platinum-refractory disease, respectively, suggesting that increased antitumor activity associated with this combination regimen might exist within patients with ROC with primary platinum resistant or primary platinum refractory disease. However, the number of patients in each cycle category was relatively small, which might be underpowered to detect the desired and stable differences. These findings highlighted that potential predictive factors for response to the combination regimen of ICI plus antiangiogenic agent are of interest and should be further validated in the further studies. This combination regimen achieved a DCR of 54.1%, which was numerically higher than the rates achieved by the treatment with pembrolizumab, nivolumab or avelumab monotherapy (33%–45%)8 9 25 28 and was close to that with avelumab plus PLD arm (57.0%) reported from the recent JAVELIN 200 trial.28 The median DoR of 4.1 months (95% CI, 1.9 to 6.3) was relatively shorter than those reported with PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy or mentioned combination regimens.8 9 13 24 25 27 The median PFS was 4.1 months and the median OS was 18.9 months, respectively, with the probability of 12-month OS rate of 67.2% in our phase 2 trial. Median PFS with this combination regimen in platinum-resistant ROC patients was slightly longer than that with chemotherapy alone (3.4 months),26 and numerically shorter than that treatment with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy (6.7 months)26 and bevacizumab plus nivolumab (7.7 months)13 in similar patient population. This might be mainly attributed to the fact that all enrolled patients with ROC in this phase 2 trial had platinum-resistant disease; high prevalence of liver metastases at baseline (13 (35.1%) patients); and fragility from heavy pretreatment (22 (59.5%) patients had received ≥3 prior lines of systemic therapy).

Notably, the OS benefit with camrelizumab plus famitinib seems to be prominent and competitive. On the other hand, previous other phase Ib and II monotherapy trials of three PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab, avelumab)9 24 25 yielded modest survival benefits, further questioning the efficacy of immunotherapy with single agent checkpoint inhibitor in the pretreated OC settings. The median OS of this combination regimen was also decent and comparable to that for bevacizumab plus chemotherapy (16.6 months) observed from AURELIA trial26 and avelumab plus PLD (15.7 months) reported from JAVELIN 200 trial27 in similar patient population.

With respect to safety, the incidence and severity of TRAEs with camrelizumab and famitinib were in line with prior reported toxic effects to be associated with single agent camrelizumab29 30 or famitinb,16 31 and no additional safety flags were identified. The most common grade 3 or higher TRAEs of this combination regimen were hypertension (32.4%), and hematologic toxicities, including decreased neutrophil count (29.7%) and decreased platelet count (13.5%). The occurrence of grade 3 or higher hypertension might be associated with famitinib, which could reflect the anti-angiogenesis effect of VEGF or VEGFR TKIs.32 33 A diary was provided to the patients for blood pressure (BP) capture during the study treatment. When elevated BP (systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg) was confirmed, patients started to receive antihypertensive agents. The choice of antihypertensive treatment was individualized to the patient’s clinical status and follow the standard medical practice. The incidence rate of RCCEP was only 5.4% (2 of 37) when patients treated with camrelizumab plus famitinib, without grade 3 or higher events reported, which was in line with previous findings observed in patients with multiple solid tumors treated with camrelizumab plus apatinib, highlighting that the pathogenesis of RCCEP might be involved with VEGFA/VEGFR-2 signaling pathway.34–36 Furthermore, the combination regimen of camrelizumab 200 mg Q3W plus famitinib 20 mg QD were generally tolerable. The frequency, type and severity of AEs were manageable. With the median follow-up duration of 22.0 months, only 7 (18.9%) patients required a dose reduction of famitinib to 15 mg due to TRAEs. The proportion of treatment discontinued owing to TRAEs was also quite low (camrelizumab, 2.7%; famitinib, 8.1%, respectively). One patient (2.7%) occurred decreased platelet count after study treatment discontinuation due to intestinal obstruction induced by tumor progression. The decreased platelet count was progressively aggravated from grade 1 to grade 3 within 3 days because she gave up further active therapy. Finally, this patient died of grade 5 hemorrhage. Although the investigator believed that the main cause of death should be attributed to the intestinal obstruction caused by tumor progression and patient’s refusal of treatment, the delayed effects of study treatment could not be completely ruled out, therefore, this AE was judged possibly related to study treatment.

The current study also had potential limitations. First, despite decent ORR and prominent OS benefit with camrelizumab plus famitinib had been observed in patients with platinum-resistant ROC, there was still lack of the standard-of-care control arm. Second, subgroup analysis by PD-L1 expression or platinum resistant status was not prespecified in our protocol, and whether PD-L1 expression or platinum resistant status could be consider as a biomarker for the efficacy of the study combination regimen in this challenging disease these warranted further investigation in future trials with larger sample size. Third, baseline data regarding BRCA gene mutation status was not prespecified and collected during the study, therefore, the relationship between BRCA gene mutation status and treatment effect could not be further assessed.

In conclusion, camrelizumab plus famitinib might provide an alternative treatment option with encouraging efficacy and a manageable safety profile for the treatment of heavily pretreated patients with platinum-resistant ROC.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and their families, investigators, and research personals for participating in this study. Writing assistance was provided by Lin Dong (PhD, a Medical Writer from Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals) according to Good Publication Practice Guidelines.

Footnotes

Contributors: Responsible for the overall content as guarantor: XW. Conception and design of the study: XW, LX and QW. Collection and assembly of clinical data: XW, LX, GL, MP, QZ, WH, HS, LW, YG, JZ and YZ. Collection and execution of correlative studies: XW, LX, GL, MP, QZ, WH, HS, LW, YG, JZ and YZ. Data analysis and interpretation of results: XW, LX, XZ and QW. Writing and revision and final approval of the manuscript: All authors.

Funding: The study was funded by Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd.

Competing interests: RS, XZ and QW are employees of Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals. No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities. Data may be requested 24 months after study completion. Qualified researchers should submit a proposal to the corresponding author outlining the reasons for requiring the data. The leading clinical site and sponsor will check whether the request is subject to any intellectual property restriction. Use of data must also comply with the requirements of Human Genetics Resources Administration of China and other country or region-specific regulations. A signed data access agreement with the sponsor is required before accessing shared data.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

All patients provided written informed consent and the institutional review boards or independent ethics committees of all participating sites approved the protocol and all amendments. The study was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice and local laws and regulatory requirements. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l'Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer 2009;115:1234–44. 10.1002/cncr.24149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indini A, Nigro O, Lengyel CG, et al. Immune-Checkpoint inhibitors in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Cancers 2021;13:1663. 10.3390/cancers13071663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24:vi24–32. 10.1093/annonc/mdt333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348:203–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa020177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang W-T, Adams SF, Tahirovic E, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T cells in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2012;124:192–8. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, et al. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:3360–5. 10.1073/pnas.0611533104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQM, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2455–65. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varga A, Piha-Paul S, Ott PA, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with programmed death ligand 1-positive advanced ovarian cancer: analysis of KEYNOTE-028. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152:243–50. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matulonis UA, Shapira-Frommer R, Santin AD, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-100 study. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1080–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdz135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Chen Y, Li F, et al. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab attenuate cisplatin resistant ovarian cancer cells progression synergistically via suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Front Immunol 2019;10:867. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahma OE, Hodi FS. The intersection between tumor angiogenesis and immune suppression. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:5449–57. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An D, Banerjee S, Lee J-M. Recent advancements of antiangiogenic combination therapies in ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2021;98:102224. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu JF, Herold C, Gray KP, et al. Assessment of combined nivolumab and bevacizumab in relapsed ovarian cancer: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1731–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markham A, Keam SJ. Camrelizumab: first global approval. Drugs 2019;79:1355–61. 10.1007/s40265-019-01167-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mo H, Huang J, Xu J, et al. Safety, anti-tumour activity, and pharmacokinetics of fixed-dose SHR-1210, an anti-PD-1 antibody in advanced solid tumours: a dose-escalation, phase 1 study. Br J Cancer 2018;119:538–45. 10.1038/s41416-018-0100-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou A, Zhang W, Chang C, et al. Phase I study of the safety, pharmacokinetics and antitumor activity of famitinib. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013;72:1043–53. 10.1007/s00280-013-2282-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie C, Zhou J, Guo Z, et al. Metabolism and bioactivation of famitinib, a novel inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase, in cancer patients. Br J Pharmacol 2013;168:1687–706. 10.1111/bph.12047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu Y-Y, Zhang H-L, Guo H, et al. Camrelizumab plus famitinib in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: data from an open-label, multicenter phase II basket study. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:5838-5846. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia L, Zhou Q, Zhang Y. 840P famitinib malate plus camrelizumab for recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancer and advanced cervical cancer: an open-label, multicenter phase II study. Ann Oncol 2020;31:S630. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Y-Y Q, Guo H, Luo H. Camrelizumab plus famitinib malate in patients with advanced renal cell cancer and unresectable urothelial carcinoma: a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Y-Y Q, Zou Q, Guo H. Camrelizumab plus famitinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma or unresectable urothelial carcinoma: updated results from a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:4550. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y, Shih WJ. Adaptive two-stage designs for single-arm phase IIA cancer clinical trials. Biometrics 2004;60:482–90. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J-M, Cimino-Mathews A, Peer CJ, et al. Safety and clinical activity of the programmed Death-Ligand 1 inhibitor Durvalumab in combination with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib or vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1-3 inhibitor cediranib in women's cancers: a dose-escalation, phase I study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2193–202. 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Disis ML, Taylor MH, Kelly K, et al. Efficacy and safety of Avelumab for patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: phase 1B results from the javelin solid tumor trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:393–401. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Ikeda T, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:4015–22. 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: the AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1302–8. 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pujade-Lauraine E, Fujiwara K, Ledermann JA, et al. Avelumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ovarian cancer (JAVELIN ovarian 200): an open-label, three-arm, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1034–46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00216-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pujade-Lauraine E, Fujiwara K, Ledermann JA, et al. Avelumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ovarian cancer (JAVELIN ovarian 200): an open-label, three-arm, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1034–46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00216-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang W, Yang Y, Ma Y, et al. Camrelizumab (SHR-1210) alone or in combination with gemcitabine plus cisplatin for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results from two single-arm, phase 1 trials. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1338–50. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30495-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin S, Ren Z, Meng Z, et al. Camrelizumab in patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:571–80. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu R-H, Shen L, Wang K-M, et al. Famitinib versus placebo in the treatment of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:97. 10.1186/s40880-017-0263-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (correct): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:303–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Qin S, Xu R, et al. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:619–29. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70156-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou C, Wang Y, Zhao J, et al. Efficacy and biomarker analysis of camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC previously treated with chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:1296–304. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Zhang Y, Jia R, et al. Anti-PD-1 antibody SHR-1210 combined with apatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric, or esophagogastric junction cancer: an open-label, dose escalation and expansion study. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:515–23. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng Z, Wei J, Wang F, et al. Camrelizumab combined with chemotherapy followed by camrelizumab plus apatinib as first-line therapy for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:3069–78. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2021-003831supp001.pdf (106KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities. Data may be requested 24 months after study completion. Qualified researchers should submit a proposal to the corresponding author outlining the reasons for requiring the data. The leading clinical site and sponsor will check whether the request is subject to any intellectual property restriction. Use of data must also comply with the requirements of Human Genetics Resources Administration of China and other country or region-specific regulations. A signed data access agreement with the sponsor is required before accessing shared data.