Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Imbalance of oxidants/antioxidants results in heart failure, contributing to mortality after burn injury. Cardiac mitochondria are a prime source of ROS, and a mitochondrial-specific antioxidant may improve burn-induced cardiomyopathy. We hypothesize that the mitochondrial-specific antioxidant, Mito-TEMPO, could protect cardiac function after burn.

STUDY DESIGN:

Male rats had a 60% TBSA scald burn injury and were treated with/without Mito-TEMPO (7 mg·kg-1, ip) and harvested at 24 hours post burn. Echocardiography (ECHO) was employed for measurement of heart function. Masson Trichrome and H & E staining were used for cardiac fibrosis and immune response. O2K system assessed mitochondria function in vivo. qPCR was used for mitochondrial DNA replication and gene expression.

RESULTS:

Burn-induced cardiac dysfunction, fibrosis, and mitochondrial damage were assessed by measurement of mitochondrial function, DNA replication, and DNA-encoded ETC-related gene expression. Mito-TEMPO partially improved the abnormal parameters. Burn-induced cardiac dysfunction was associated with crosstalk between the NFE2L2-ARE pathway, PDE5A-PKG pathway, PARP1-POLG-mtDNA replication pathway, and mitochondrial SIRT signaling.

CONCLUSIONS:

Mitochondrial-specific antioxidant (Mito-TEMPO) reversed burn-induced cardiac dysfunction by rescuing cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants may be an effective therapy for burn-induced cardiac dysfunction.

Precis

Mitochondrial-specific antioxidant (Mito-TEMPO) reversed burn-induced cardiac dysfunction by rescuing cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Severe burns are associated with high mortality in both pediatric and adult patient populations (1). Burns and associated inhalation injuries are frequently plagued by complications, including infection and multi-organ system dysfunction. Multi-organ system dysfunction is a major contributor to mortality from burns (2, 3). Cardiac dysfunction has been well described as a sequelae of burn injury and a contributor to multi-organ failure (4, 5).

Burns induce a significant stress response which results in several metabolic consequences including hypermetabolism, muscle wasting, and stress-induced diabetes (6). Mitochondria play a role in maintaining homeostasis by regulating oxygen consumption and cell energy expenditure. ATP-consuming reactions have been estimated to account for 57% of the hypermetabolic response to burns. This suggests that mitochondrial oxygen consumption is a significant contributing factor to burn hypermetabolism (7). While some tissues can adapt following burn injury with increased respiratory capacity and function (8), other tissues are unable to, resulting in impaired mitochondrial function (9). Mitochondrial damage following burns has been specifically described in cardiac tissues (10, 11). This may be due to oxidative stress secondary to the hypermetabolic state (9). This increased oxidative stress provides a target for therapeutic intervention to abrogate the progression of cardiovascular dysfunction (12). Antioxidants have been used in heart failure as a means to treat oxidative stress to cardiomyocytes (13). Moreover, antioxidant vitamin therapy has been previously shown to disrupt cardiac inflammatory cytokine secretion after burn injury (14).

Recently, it has been presented that an antioxidant targeting mitochondria, Triphenylphosphonium chloride (Mito-TEMPO), may be protective against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity (15). Mito-TEMPO is a well-known mitochondria-specific superoxide scavenger and a physiochemical compound mimicking superoxide dismutase from mitochondria which functions to suppress mitochondrial ROS. Moreover, a therapeutic inhibition of mitochondrial ROS with Mito-TEMPO reduces diabetic cardiomyopathy (16), while resolution of oxidative stress in mitochondria by Mito-TEMPO in old mice restored cardiac function and the capacity of coronary vasodilation to the same magnitude observed in the young mice (1, 17). Overall, one can hypothesize that a direct mitochondria targeting antioxidant enhancement strategy may have promissive therapeutic benefits in heart complications after burn. Therefore, we aim to understand how the imbalance of oxidants and antioxidants might lead to cardiac dysfunction following burn injury. Mito-TEMPO is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant which has been shown to decrease oxidative stress in fibrosis, carcinogenesis, and sepsis models (18–20). We hypothesize that cardiac mitochondria are a main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Mito-TEMPO might be beneficial in improving burn-induced cardiac dysfunction.

METHODS

Ethics statement

All animal research procedures adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for experimental animal use and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, TX (Protocol number: 1509059).

Study design and treatment protocol

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were allowed to acclimate for 1 week before experimentation and received food and water ad libitum throughout the study. Animals were kept on a 12:12 light-dark cycle. Temperature was maintained at ~22°C in all animal housing and procedure rooms. The animals were then randomly assigned to either the Sham (control) group or the 24 hours post burn (24 hpb) group A well-established model for the induction of a 60% TBSA full-thickness burn was used (8, 21). Briefly, rats (300–350 g) were given analgesia (buprenorphine, 0.05mg/kg, s.c.) and anesthetized with general anesthesia (isoflurane, 3–5%). Rats were placed within a protective mold that exposed ~60% of the TBSA and submerged in 95°C to 100°C water to induce a scald burn. The dorsum was immersed to 10 seconds and the abdomen for 2 seconds, resulting in a 30% TBSA injury on both the dorsum and the abdomen (60% TBSA burn in total). Room temperature Lactated Ringer (LR) solution (40 mL/kg, i.p. ± Triphenylphosphonium chloride (Mito-TEMPO, 7 mg/kg body weight, ip) was administered immediately after the burn for resuscitation. Rats received oxygen during the recovery from anesthesia. At pre-determined time points (24 hpb), rats were humanely euthanized, and blood and tissue were collected. Fresh heart tissues were used to isolate mitochondria and rest tissue samples were stored −80°C.

Cardiac mitochondria isolation

Cardiac mitochondria were isolated/purified using the MitoCheck® Mitochondrial (Tissue) Isolation Kit (Cayman, Ann Arbor, Michigan, Cat# 701010) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the heart tissue was washed, suspended in mitochondrial homogenization buffer to be homogenized, and spun at 680 × g for 15 minutes; the supernatant was then transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again at 8,800 × g for 15 minutes. Mitochondrial pellets were washed twice-using mitochondrial homogenization buffer containing protease inhibitor (Abcam Cat# ab201111). Mitochondrial protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Aliquoted mitochondrial pellets were stored at −80 °C for later usage.

Cardiac oxidants/antioxidants

ROS release was measured by an Amplex red assay. Briefly, heart tissue homogenized samples (50 μg protein) were added to black flat-bottom plates. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 50 μl each of 100 μM Amplex red (Invitrogen) and 0.3 U/ml HRP. The HRP catalyzed Amplex red oxidation by H2O2, resulting in fluorescent resorufin formation, was monitored at Ex563 nm/Em587 nm (standard curve: 50 nM - 5 M H2O2) using a Spectra Max M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA).

Myocardial mitochondrial Glutathione (GSH) and Glutathione Disulfide (GSSG) were measured with a spectrophotometric method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, Cat# 703002). Briefly, isolated heart mitochondria were homogenized in phosphate buffer containing 1 mM EDTA (pH 7, 5–10 ml/g tissue) and harvested the supernatant after centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, The quantification of GSSG, exclusive of GSH, was accomplished by first derivatized GSH with 2-vinylpyridine. GSH reacts with DTNB (5,5’-dithio-bis-2-(nitrobenzoic acid) to produce a yellow colored TNB (5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid). The rate of TNB production is directly proportional to the formation of GSH which is measured at 405–414 nm using a plate reader after incubating for 25 min.

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was assessed using lag time by antioxidants against the myoglobin-induced oxidation of 2,2’-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) with H2O2 (Antioxidant Assay kit, Cayman Chemical, cat# 709001). Briefly, 20 μl of plasma samples (diluted 1:20, v/v) and/or heart homogenates (15 μg protein) were added in triplicate to 96-well plates and mixed with 90 μl of 10 mM PBS (pH 7.2), 50 μl of myoglobin solution, and 20 μl of 3 mM ABTS. Reaction was initiated with H2O2 (20 μl) and change in color monitored at 600 nm (standard curve: 2–25 μM trolox).

Mitochondrial MnSOD activity was measured by using total SOD activity minus Cu,ZnSOD activity. Total activity was measured using a commercially available kit (Superoxide Dismutase Assay Kit, Cayman Chemical, cat# 706002) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cu,ZnSOD activity was measured by addition of SDS (final concentration: 2%) in sample solutions to inhibit MnSOD (standard curve: 0.005–0.05 U/ml recombinant CuZnSOD).

Echocardiography (ECHO)

Rats were sedated with inhaled anesthesia (1.5% isoflurane/100% O2) and placed supine on an electrical heating pad at 37°C, and heart rate and respiratory physiology were continuously monitored by ECHO. After shaving the chest, warmed ultrasound gel was applied, and transthoracic ECHO was performed using the Vevo® 2100 ultrasound system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) equipped with a high-frequency linear array transducer (MS250 13–24 MHz)(22). All measurements were obtained in triplicate, and data were analyzed using the Vevo® 2100 standard measurement package.

Histology

Heart tissue sections were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for at least 24 hours, dehydrated in absolute ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micron tissue sections were subjected to staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s Trichrome at the Research Histopathology Core at the UTMB. The images were obtained by Motic EasyScanner and analyzed by using Motic DSAssistant software (Motic North America, British Columbia, Canada) and Image J software. Myocarditis (presence of inflammatory cells) in H&E stained tissue sections was scored as 0 (absent), 1 (focal/mild, ≤ 1 foci), 2 (moderate, ≥ 2 inflammatory foci), 3 (extensive coalescing of inflammatory foci or disseminated inflammation), and 4 (diffuse inflammation, tissue necrosis, interstitial edema, and loss of integrity). Inflammatory infiltrates were characterized as diffuse or focal depending upon how closely the inflammatory cells were associated (23). Fibrosis was assessed by measuring the collagen area as a percentage of the total myocardial area and categorized as (0) < 1%, (1) 1–5%, (2) 5–10%, (3) 10–15%, and > 15% based on percent fibrotic area (24).

Gene expression analysis

Heart tissue-sections (10 mg) were homogenized in 100 μl TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and total RNA was extracted and precipitated by chloroform/isoamyl alcohol/isopropanol method. The RNAs were treated by DNase I, RNase-free (Westlake, LA. Cat# M0303S) to digest genomic DNA. To judge the integrity and overall quality of isolated RNAs, 2 μg RNAs were added to 10X native agarose gel loading buffer (15% ficoll, 0.25% xylene cyanol, 0.25% bromophenol blue) and run on 1% native agarose gels. The integrity RNAs were washed with 75% cold ethanol, re-suspended in 20 μl of UltraPure™ nucleotide-free distilled water, and a DU® 700 UV/Visible Spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, CA) was used to measure absorbance at 260 and 280 nm (OD260/280 ratio ≥ 2, 1 OD260 Unit = 40 μg/ml RNA). Total RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed with Oligo(dT)20 primer using a SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). The cDNA was used as a template in a real-time quantitative PCR on an iCycler Thermal Cycler with SYBR-Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and gene-specific oligonucleotides (Table 1). The threshold cycle (Ct) values for target mRNAs were normalized to multi-housekeeping genes including GAPDH mRNA, α-tubulin and β-actin and the relative expression level of each target gene was calculated as fold change (25).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides Used for Gene Expression Studies

| Gene | 5‘-Forward-3’ | 5‘-Reverse-3’ | Amplicon size (bp) | Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | CTATGAGGGTTACGCGCTCC | ATGTCACGCACGATTTCCCT | 141 | NM_031144.3 |

| ATP6 | TAGGCTTCCGACACAAACTAAA | CTGCTAGTGCTATCGGTTGAATA | 129 | KF011917.1 |

| COXI | GCCAGTATTAGCAGCAGGTATC | GGTGGCCGAAGAATCAGAATAG | 125 | KF011917.1 |

| Cyt B | CCTTCCTACCATTCCTGCATAC | TGGCCTCCGATTCATGTTAAG | 118 | KF011917.1 |

| GAPDH | ACTCCCATTCTTCCACCTTTG | CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCATATT | 105 | NM_017008.4 |

| GCLC | CCTCCTCCTCCAAACTCAGATA | TGGTCAGCAGTACCACAAATAC | 112 | NM_012815.2 |

| HO1 | GATGGCCTCCTTGTACCATATC | AGCTCCTCAGGGAAGTAGAG | 99 | NM_012580.2 |

| NFE2L2 | CACTCTGTGGAGTCTTCCATTT | GAATGTGTTGGCTGTGCTTTAG | 125 | BC061724.1 |

| ND1 | GGCTCCTTCTCCCTACAAATAC | AAGGGAGCTCGATTTGTTTCT | 122 | KF011917.1 |

| NQO1 | TGAGAAGAGCCCTGATTGTATTG | CACCTCCCATCCTTTCTTCTTC | 104 | NM_017000.3 |

| PARP1 | GCTGAGGTCATCAGGAAGTATG | CTCTCCCTCTCGCTCTATCTT | 102 | NM_013063.2 |

| PDE5 | GCCGCCACTATTATCTCCTTC | CTACTTCCTCCCACTCCATTTG | 112 | NM_133584.1 |

| PGC1α | GACACGAGGAAAGGAAGACTAAA | GTCTTGGAGCTCCTGTGATATG | 119 | AY237127.1 |

| PKG | GGGAAGGTCGAAGTCACAAA | CTGTCCGGGTACAGTTGTAAAG | 100 | EU251189.1 |

| POLG | GGTTGTCCAGGGAGAGTTTATG | CCACAAGCATGAGGTGTAAGTA | 86 | NM_053528.1 |

| POLRmt | GCTCACGCTGGACATGTATAA | ATGAACACATACACCAGCTCTC | 81 | NM_001106766. |

| RhoA | GACCAGTTCCCAGAGGTTTATG | GTCCCATAAAGCCAACTCTACC | 96 | 1 D84477.1 |

| RGS2 | GGAAGACCCGTTTGAGCTATT | TCCTCAGGAGAAGGCTTGATA | 106 | NM_053453.2 |

| SIRT3 | CCCAATGTCGCTCACTACTT | AGGGATACCAGATGCTCTCT | 105 | NM_001106313. |

| SSB | GTGGAAGGCAAAGTGGACTA | CTTGCCTGGTCACTCAGAAATA | 107 | CTTGCCTGGT |

| TFAM | CTGAGTGGAAGGTGTACAAAGA | CTTCCTTCTCTAAGCCCATCAG | 84 | BC062022.1 |

| TOP1 | CTGAACCAAGGAGACGGAATAC | GTTTGGGACTGATCCCATTGA | 106 | AY550025.1 |

| Tubulin | AATTCGCAAGCTGGCTGACC | CCGTAGTCGACAGAGAGCCT | 123 | NM_022298.1 |

| Twinkle | GATCGCAGCTCAAGACTACAT | TCTTCTTTCCGTGGGTGAATAA | 96 | NM_001107599. |

Sample size and Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with triplicate observations per sample (n =6–8 Rats/group) and data were expressed as mean ± standard error mean (SEM). All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Data (linear range or log10 transformed) were analyzed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test under Column Statistics to determine if the data are normally distributed. Normally distributed data were analyzed by Student’s t test (comparison of 2 groups) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (comparison of multiple groups). If data were not normally distributed, then Mann-Whitney (comparison of 2 groups) and Kruskal-Wallis (K-W, comparison of multiple groups) tests were employed. Significance is presented by *24 hpb vs. sham rats or &24 hpb/TEMPO vs. 24 hpb) (*,&p<0.05, **,&&p<0.01, ***,&&&p<0.001).

RESULTS

Effect of Mito-TEMPO on the balance of cardiac oxidants and antioxidants after burn injury.

We evaluated the effect of Mito-TEMPO on the ROS (Fig.1A) including heart tissue H2O2 (Fig.1A.a), cardiac mitochondrial H2O2 (Fig. 1A.b) and cardiac mitochondrial GSSG (Fig.1A.c), and on the antioxidants (Fig.1B) including heart total antioxidant (Fig. 1B.a), cardiac mitochondrial MnSOD activity (Fig.1B.b) and mitochondrial GSH (Fig. 1B.c) in sham control, 24 hpb and 24 hpb/Mito-TEMPO rats. In 24 hpb rats, H2O2 levels either in the heart tissue or cardiac mitochondria were increased by 12.8-fold in heart tissue (Fig.1A.a), and 3.5-fold in cardiac mitochondria (Fig. 1A.b), respectively. In cardiac mitochondria after burn injury, the GSSG level was increased by 74% (Fig. 1A.c) and the GSH level was decreased by 61% (Fig. 1B.c), respectively.

Figure 1.

Effect of Mito-TEMPO on the balance of cardiac oxidants and antioxidants after burn injury. Shown are levels of (A) cardiac total H2O2 (a), cardiac mitochondrial H2O2 (b) and cardiac mitochondrial GSSG content after burn injury (± Mito-TEMPO). Shown are levels of (B) total cardiac antioxidant capacity (B.a), cardiac mitochondrial MnSOD activity (B.b) and cardiac mitochondrial GSH content (B.c) after burn injury (± Mito-TEMPO). In all figures, data are plotted as mean value ± SD. Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. sham) or # (24 hpb vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as *, #p<0.05, **, ##p<0.01, ***, ### p<0.001 (n = ≥6 per group).

Our data showed a 61% decrease in total antioxidant levels (Fig. 1B.a) and a 38% decrease in MnSOD activity (Fig.1B.b) in the heart after burn injury. Mito-TEMPO reduced cardiac H2O2 by 95% (Fig.1A), cardiac mitochondria H2O2 by 85% (Fig. 1A.b), and cardiac mitochondria GSSG by 76% (Fig. 1A.c) compared to burn injury alone. In addition, Mito-TEMPO increased cardiac antioxidants by 73% (Fig. 1B.a), cardiac mitochondria MnSOD by 72% (Fig. 1B.b), and cardiac mitochondria GSH by 81% (Fig. 1B.c) compared to burn injury alone.

Effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac dysfunction.

Echocardiography-imaging showed the indices of LV systolic function, i.e., ejection fraction (EF), stroke volume (SV) was decreased by 20% (Fig. 2A), and 36% (Fig. 2B) respectively after burn injury. Left ventricular internal diameter end systole (LVID;s) and LV systolic volume (LV Vol;s) were increased by 20% (Fig. 2C), and 81% (Fig. 2D) respectively, after burn injury. Mito-TEMPO administration normalized systolic function to sham levels (Fig 2A–2D).

Figure 2.

Effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac dysfunction. Shown are (A) ejection fraction (EF), (B) stroke volume (SV), (C) Left ventricular internal diameter end systole (LVID;s), (D) left ventricular systolic volume (LV Vol;s.). Data are presented as mean value ± SD, shown as **, && p < 0.01, ***, &&& p < 0.001 (n = ≥ 6 per group).

Effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced myocardial inflammation.

Histological evaluation of tissue sections by H&E staining showed that myocardial inflammation was significantly increased in 24 hpb (score: 4.0 ± 0.4 vs. 0.23 ± 0.04, Sham vs. 24 hpb, Fig 3). An 8-fold increase in cardiac inflammation after burn injury (vs. sham control) was also noted (Fig 3B, p<0.001). Mito-TEMPO significantly reduced the inflammation score compared to burn injury alone (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced myocardial inflammation.

(A) Shown are representative H&E stained images of the left ventricle (magnification: 20×. Pink: muscle/cytoplasm/keratin, blue: nuclear) (panels A.a to A.c). (B) Shown are the density measurements from panel A. In all figures, data are plotted as mean value ± SEM (n ≥ 6 per group). Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. matched control) or & (24 hpb/untreated vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as ***,&&& p < 0.001 (n = ≥ 6 per group).

Effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac fibrogenesis.

Histological evaluation of tissue sections with Masson’s Trichrome stain showed that myocardial collagen content was significantly increased in 24 hpb myocardium (score: 4.0 ± 0.4 vs. 0.5 ± 0.04, 24 hpb vs. sham control, Fig 4). An increase in cardiac fibrosis after burn injury was noted by a 1.5–8-fold increase in mRNA levels for COL1A1, COL3A1, and COL5A2 (data not shown). Mito-TEMPO reduced the staining area score by 65% compared to burn injury alone (Fig 4). Mito-TEMPO also reduced the mRNA levels of collagen isoforms from 50–90% compared to burn injury alone (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac fibrogenesis.

(A) Shown are representative images of the left ventricle with Masson’s trichrome staining (panels a–c). (B) Shown are the relative density measurements from panel A. In all figures, data are plotted as mean value ± SEM (n ≥ 6 per group). Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. matched control) or & (24 hpb/untreated vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as ***,&&& p < 0.001 (n = ≥ 6 per group).

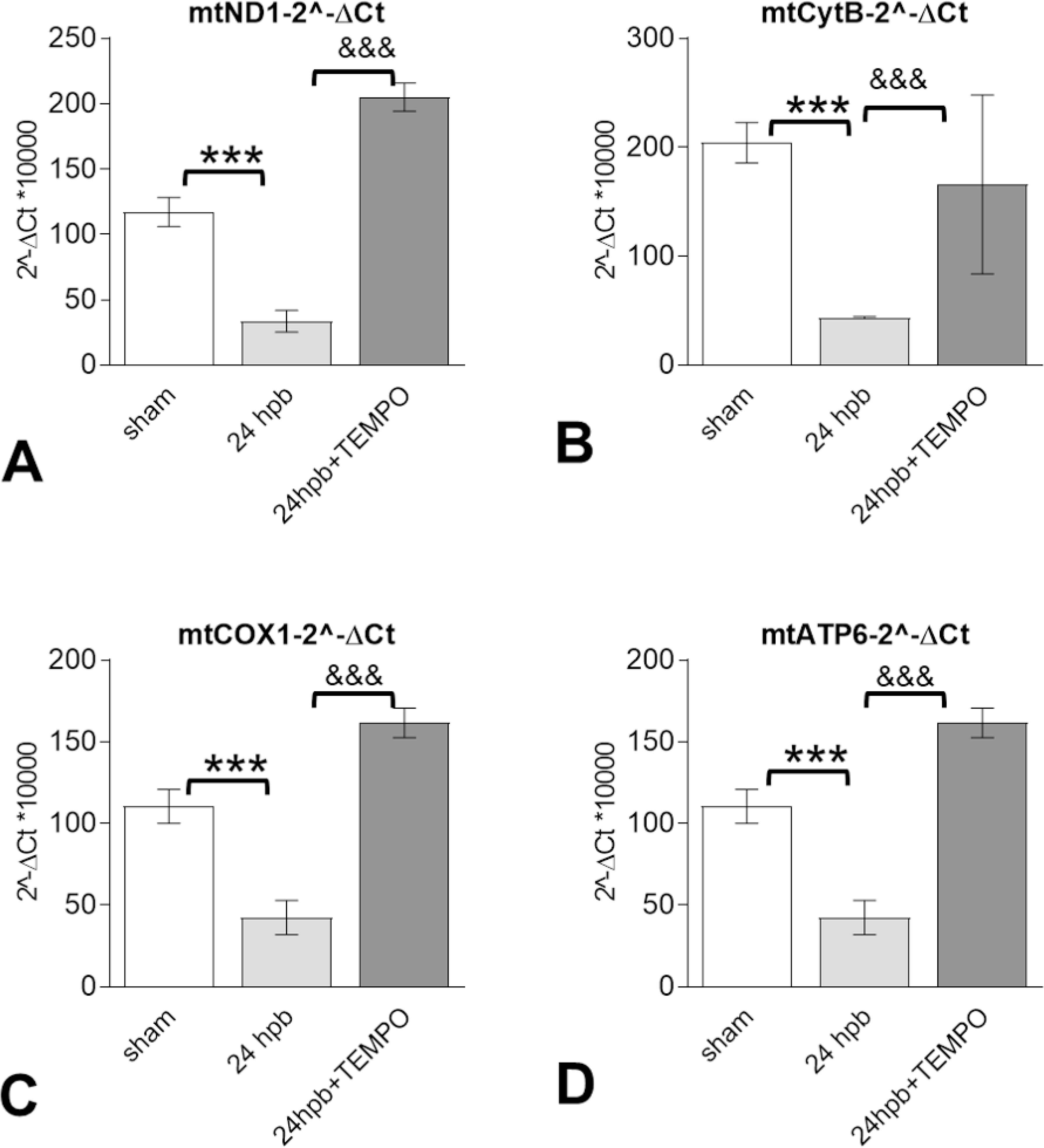

Effects of Mito-TEMPO on mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene expression after burn injury

Burn injury significantly decreased mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene expression of electron transport chain complex I gene (ND1, Fig.5A), complex III gene (CYTB, Fig 5B), complex IV gene (COI, Fig 5C), and complex V gene (ATP6, Fig. 5D) compared to control. Mito-TEMPO administration reversed mitochondrial DNA encoded gene expression to sham levels (Fig 5).

Figure 5. Effects of Mito-TEMPO on mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene expression after burn injury.

Shown are (A) representatives of the mitochondrial DNA encoded complex I genes (mtND1), (B) mitochondrial DNA encoded complex III gene (CYTB) (C) mitochondrial DNA encoded complex IV gene (COXI), and (D) mitochondrial DNA encoded complex V genes (ATP6). In all figures, data are presented as mean value SD. Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. sham control) or & (24 hpb vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as ***, &&& p < 0.001 (n = 6 per group).

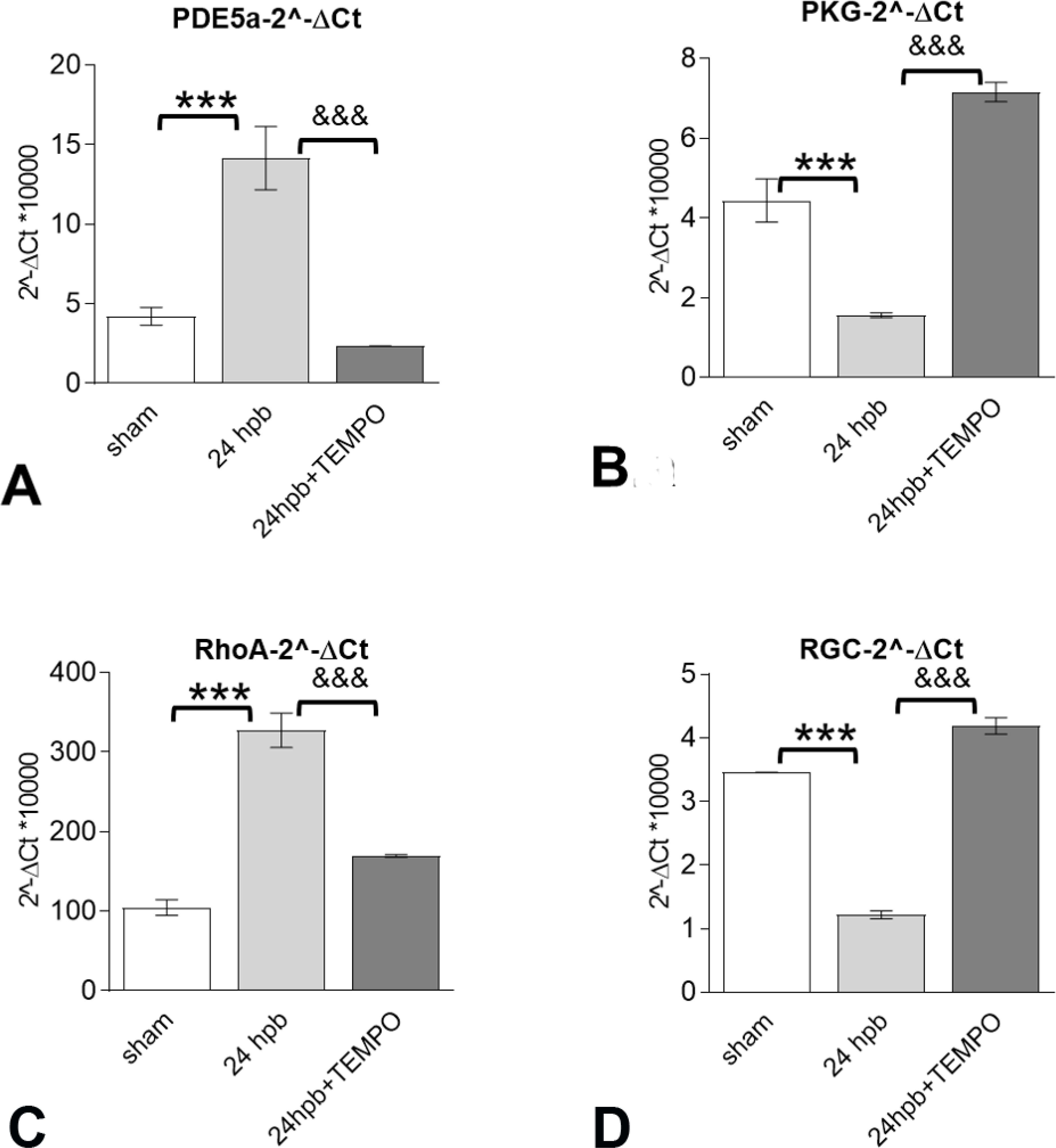

The effect of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac dysfunction occurs through the PDE5A-PKG pathway.

After burn injury, PDE5A gene expression was increased 2.36-fold (Fig.6A), PKG expression was decreased by 65% (Fig. 6B.a), RhoA expression was increased 2.12-fold (Fig.5B.b) and RGC gene was decreased 6-fold (Fig. 6B.d) compared to sham control. Mito-TEMPO administration normalized PDE5A-cGMP-PKG related gene expression to sham levels (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. The effects of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac dysfunction occur through the PDE5A-PKG pathway.

Shown are (A) Myocardial levels of PDE5A mRNA and Myocardial levels of PKG (B) as well as PKG-down-regulated genes including RhoA (C) and RGC (D) mRNA levels. Results were normalized to GAPDH and β-actin mRNAs, and represent as 2 −ΔCt x 1000. In all figures, data are plotted as mean value ± SD. Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. control) or & (24 hpb vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as ***, &&& p < 0.001 (n = ≥ 6 per group).

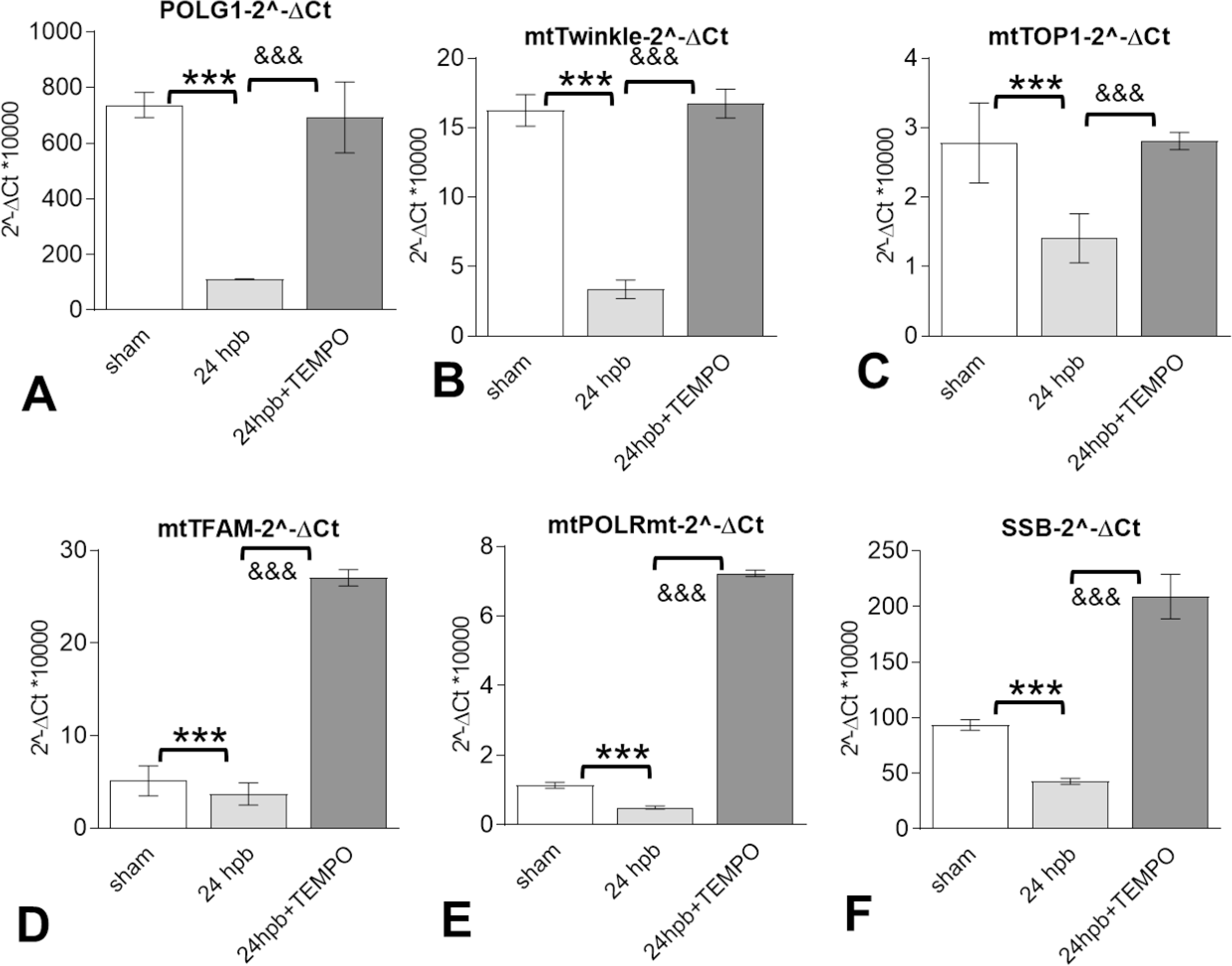

Mito-TEMPO improves burn-induced cardiac dysfunction through regulation of mitochondrial DNA replication-related genes.

The mRNA levels for the components of the mitochondrial DNA replication/repair complex, including Twinkle, TOP1mt, POLRMT, and SSPB1, as well as the genes of the mitochondrial transcription machinery, including POLG and TFAM, were significantly decreased by 85% for POLG (Fig. 7A), 79% for Twinkle (Fig. 7B), 49% for TOP1 (Fig. 7C), 30% for TFAM (Fig. 7D), 56% for POLRmt (Fig. 7E), and 54% for SSB (Fig. 7F) after burn injury. All mitochondrial DNA replication/repair complex mRNA levels in the myocardium were returned to sham levels after Mito-TEMPO administration.

Figure 7. The benefits of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac dysfunction were through regulation of mitochondrial DNA replication-related genes.

Shown are mitochondrial DNA replication-related genes included (A) mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma 1 (POLG1), (B) mitochondrial twinkle, (C) mitochondrial topoisomerase 1 (TOP1), (D) mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), (E) mitochondrial DNA directed RNA polymerase (mtPOLR), (F) mitochondrial single stranded DNA binding protein (mtSSB). Results were normalized to GAPDH and β-actin mRNAs and represent fold change after burn injury (±MitoTEMPO), as compared to sham. In all figures, data are plotted as mean value ± SD. Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. control) or & (24 hpb vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as ***, &&& p < 0.001 (n = ≥ 6 per group).

Mito-TEMPO modulates burn-induced cardiac dysfunction via the Nrf2-ARE-ROS axis

Real-time (RT)-quantitative PCR showed that the mRNA level for Nrf2 was decreased by 64% in response to burn injury (Fig. 8A). The mRNA levels for Nrf2-dependent HO-1, NQO1, and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) antioxidants were depressed by 38%, 77%, and 79%, respectively, after burn injury (Fig. 8B–D). The mRNA levels for NEF2L2 (aka Nrf2), HO-1, NQO1 and GCLC antioxidants after Mito-TEMPO treatment remained significantly higher or equal to the levels noted in sham control (Fig. 8A–D).

Figure 8. The benefit of Mito-TEMPO on burn-induced cardiac dysfunction via Nrf2-ARE-ROS axis.

Shown are target genes of Nrf2-ARE-ROS axis including: (A)Nrf2 (A), HO-1 (B), NQO1 (C), GCLM (D), PGC1-alpha (E), PARP1 and SIRT3 (G). Results were normalized to rat GAPDH and β-actin mRNAs and represent fold change after a burn (±TEMPO), as compared to that noted in matched normal controls. In all figures, data are plotted as mean value ± SD. Significance is shown as * (24 hpb vs. control) or & (24 hpb vs. 24 hpb/TEMPO), and presented as ***, &&& p < 0.001 (n = ≥ 6 per group).

In examining the PGC1α -NDA mitochondrial biogenesis pathway, we found that burn injury resulted in 67%, 18-fold, and 58% decline in PGC1alpha (Fig.8E), PARP1 (Fig. 8F), and SIRT3 (Fig. 8G), respectively. Mito-TEMPO treatment resulted in normalization of the PGC1α-NDA pathway to sham levels.

Discussion:

In summary, our data demonstrate that burn injury increased cardiac ROS production, inflammation, and fibrogenesis while decreasing cardiac antioxidant production and mitochondrial DNA encoded gene expression. These findings were associated with decreases in cardiac function and modulation of the PDE5A-PKG and Nrf2-ARE-ROS pathways. Mito-TEMPO administration restored cardiac ROS, inflammation, fibrogenesis, antioxidants and mitochondrial DNA encoded gene expression to sham levels.

These data suggest that Mito-TEMPO protects against heart dysfunction and mitochondrial damage after burns by increasing total antioxidant capacity of the heart, preserving heart mitochondrial activity, preserving cardiac function, and decreasing cardiac inflammation and fibrogenesis. Mito-TEMPO also affects mitochondrial DNA encoded gene expression after burn injury and is associated with the PDE5A-PKG pathway, PARP1-POLG-mtDNA replication pathway, mitochondria SIRT signaling pathway, and the Nrf2-ARE-ROS axis. These findings, along with our previous studies, strongly suggest crosstalk between the PDE5A-PKG pathway and the Nrf2-ARE-ROS pathways (11,26). To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the utility of Mito-TEMPO as a cardioprotective antioxidant post-burn injury and supports the use of mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants as a therapeutic agent for cardiac dysfunction after burn injury.

Several markers may be used to quantify oxidative stress in mammals. Concentrated hydrogen peroxide is a main marker of ROS that exists in both the cytosol and mitochondria. Glutathione disulfide is created in the reduction of hydrogen peroxide and thus is a useful indicator of oxidative stress, with higher GSH/GSSG ratios signifying less oxidative stress to the organism (27). MnSOD is an only enzyme in the mitochondria that converts hydrogen peroxide to diatomic oxygen, functionally clearing the mitochondria of ROS and preventing apoptosis (28). Our previous research found that cardiac mitochondrial damage caused by burn injury is associated with decreased MnSOD activity and an increase in mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation via dysregulation of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant expression (11, 26). Our results in this study show that Mito-TEMPO had a significant effect in lowering the level of ROS in both mitochondria and heart tissue. Antioxidant levels, mitochondrial MnSOD activity, and the GSH/GSSG ratio (Figure 1) were all elevated in Mito-TEMPO treated specimens, indicating that the oxidative stress to the mitochondria during burn injury was lower after treatment.

At ten years post-burn, approximately half of pediatric patients develop systolic heart dysfunction and about 70% of patients experience diastolic heart dysfunction (29, 30). However, little is known about the mechanism behind acute cardiac dysfunction post-burn. Acute burn injury-associated cardiac dysfunction manifests clinically as acute heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy (31–33). This is reflected in the echocardiography results seen in this study: ejection fraction and stroke volume are decreased and the ventricular size and end-diastolic volume are increased after burn injury. Mito-TEMPO was effective in preserving these measures of cardiac function, suggesting that it may be an effective agent to preserve cardiac function acutely.

Burn injury causes patients to enter a hyper-inflammatory state, which is reflected in inflammatory cell infiltration in the post-burn myocardium (5). This was seen in our model as well. Mito-TEMPO treatment resulted in fewer infiltrating inflammatory cells after burn injury. Our observations may infer that Mito-TEMPO down regulates pro-inflammatory pathways in addition to its role as a direct antioxidant. In other disease states, such as heart failure, antioxidants have been shown to decrease inflammation through the Nitric oxide pathway (34). The pro-inflammatory state seen post-burn is known to induce fibrogenesis and, in dermal tissue, steroids and anti-adrenergic agents have decreased post-burn fibrogenesis (35). We observed that Mito-TEMPO was effective in decreasing post-burn fibrogenesis in cardiomyocytes. Our previous research revealed a similar finding, when a PDE5A inhibitor was found to ameliorate post-burn fibrogenesis (36). Another study found that elevated antioxidant enzymes resulting from sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition decreased myocardial oxidative stress and fibrogenesis (37).

Mitochondrial dysfunction post-burn has been described in muscle, adipose, and hepatic tissue (9, 38, 39). One explanation for this impairment may relate to issues in the electron transport chain (ETC). Mitochondrial gene expression for ETC components of cytochrome b-2, NADH dehydrogenase, cytochrome c oxidase, and ATP synthase were all decreased post-burn but preserved with Mito-TEMPO treatment. The antioxidant might preserve mitochondrial function by preventing down-regulation of mitochondrial gene expression, which is involved in production of ETC components, resulting in the beneficial effects on cardiac function in the setting of post-burn oxidative stress.

Our previous research demonstrated that the PDE5A-cGMP-PKG pathway plays a role in burn-induced cardiomyopathy (36). This is further supported by other previously published articles that have shown that PDE5A is upregulated in the setting of cardiac hypertrophy (40). Moreover, PKG1α kinase upregulation may be cardioprotective (41). We observed that treatment with Mito-TEMPO was effective in preventing the upregulation of the PDE5A pathway, ultimately resulting in elevated PKG and subsequently elevated RGC2 levels. This finding suggests that antioxidants may either directly or indirectly affect the PDE5A pathway. Sildenafil, a PDE5A inhibitor, has been shown to decrease inflammatory cell infiltration in brain tissue (42)(43). This pathway may be another mechanism by which Mito-TEMPO prevents post-burn cardiac dysfunction.

Mitochondrial replication was found to be decreased post-burn, which might serve as a surrogate for mitochondrial dysfunction by reflecting that mitochondrial machinery may not be working properly. Several diseases result from mutations affecting mitochondrial replication factors (44). Mutations in POLG, Twinkle, and other genes responsible for the mitochondrial DNA replication machinery have been associated with deletions, point mutations, and depletion of mitochondrial DNA (45). Several mitochondrial polymerase and replication factors have increased expression in Mito-TEMPO treated rats relative to untreated rats post-burn. These findings suggest that mitochondrial antioxidant treatment might also preserve mitochondrial replication post-burn.

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2 or NFE2L2), is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of antioxidants as a response to significant oxidative stress, like severe burn injury (46). Our previous research demonstrated that the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC1a-Nrf2-ARE pathway plays a critical role in cardiac dysfunction (26). SIRT3 is a sirtuin (NAD+ - dependent deacetylase) that has been shown to promote genome stability during oxidative, metabolic, and genotoxic stress in a number of human disease states (47, 48). We observed that treatment with Mito-TEMPO affected this pathway, ultimately leading to elevated SIRT3 expression in treated specimens. This suggests that mitochondria-directed antioxidants, specifically Mito-TEMPO, may crosstalk with the Nrf2 pathway, providing another explanation for the protective effect of Mito-TEMPO on cardiomyocytes following burns-induced oxidative stress.

In summary, burn injury results in cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction due to the generation of ROS and decrease of mitochondrial antioxidants(11, 26). A mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, Mito-TEMPO, mimics superoxide dismutase and accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix where it may impact metabolism following a burn injury and decrease the likelihood of mitochondrial injury. The most significant finding in this study was that Mito-TEMPO provided effective protection against burn-induced heart dysfunction, possibly by inhibiting mitochondrial ROS, which in turn modulated the course of the disease. We also found that Mito-TEMPO treatment maintained mitochondrial function, not only by scavenging ROS, but by also normalizing PDE5A-cGMP-PKG and Nrf2-ARE-PGC-1 pathways. Taken together, these results indicated that appropriately inhibited mitochondrial superoxide generation could maintain the stability of cardiac function after burn.

CONCLUSIONS

Mitochondrial specific antioxidant (Mito-TEMPO) abrogated burn-induced heart dysfunction via improvement of cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants may be an effective therapy for burn-induced cardiac dysfunction by decreasing post-burn inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrogenesis. This study also raises the possibility that there is crosstalk between the PDE5A-cGMP-PKG, PARP1-POLG-mtDNA replication, and mitochondria SIRT signaling pathways in the setting of burn injury.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- EF

ejection fraction

- ETC

electron transport chain

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide-4-trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone

- GCLM

gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione Disulfide

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HO1

Heme Oxygenase 1

- Hpb

hours post burn

- LR

lactated ringer

- LV

left ventricular

- LV Vol;s

left ventricular systolic volume

- LVID;s

left ventricular internal diameter end systole

- Mito-TEMPO

Triphenylphosphonium chloride

- MnSOD

Manganese Superoxide Dismutase

- mtATP6

Mitochondrial DNA encoded complex V gene, ATP Synthase Membrane Subunit 6

- mtCOX1

Mitochondrial DNA encoded complex IV gene, cyclo-oxygenase 1

- mtCytB

Mitochondrial DNA encoded complex III gene, cytochrome B

- mtND1

Mitochondrial DNA encoded complex I gene, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 1

- mtPOLR

Mitochondrial DNA directed RNA polymerase

- mtSSB

Mitochondrial single stranded DNA binding protein

- NQO1

NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1

- Nrf2-ARE-ROS

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (aka NFE2L2) – Antioxidant Response Elements – Reactive Oxygen Species

- PARP1-POLG-mtDNA

Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 - DNA Polymerase Gamma – mitochondrial DNA

- PDE5A-PKG

Phosphodiesterase 5A Protein Kinase G

- PGC1 – alpha

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- POLG1

Mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma 1 (POLG1)

- RhoA

Rho Kinase A

- RGC

receptor guanylate cyclase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SIRT3

Sirtuin 3

- TOP1

Mitochondrial topoisomerase 1

- TFAM

Mitochondrial transcription factor A

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Selected for the 2020 Southern Surgical Association Program.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klein MB, Goverman J, Hayden DL, et al. Benchmarking outcomes in the critically injured burn patient. Ann Surg. 2014. May;259(5):833–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SF, Bessey PQ, Schurr MJ, et al. National Burn Repository 2005: a ten-year review. J Burn Care Res. 2006. Jul-Aug;27(4):411–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallinen O, Maisniemi K, Bohling T, et al. Multiple organ failure as a cause of death in patients with severe burns. J Burn Care Res. 2012. Mar-Apr;33(2):206–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeschke MG, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, et al. Long-term persistance of the pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillory AN, Clayton RP, Herndon DN, Finnerty CC. Cardiovascular Dysfunction Following Burn Injury: What We Have Learned from Rat and Mouse Models. Int J Mol Sci. 2016. Jan 2;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter C, Tompkins RG, Finnerty CC, et al. The metabolic stress response to burn trauma: current understanding and therapies. Lancet. 2016. Oct 1;388(10052):1417–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu YM, Tompkins RG, Ryan CM, Young VR. The metabolic basis of the increase of the increase in energy expenditure in severely burned patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1999. May-Jun;23(3):160–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohanon FJ, Nunez Lopez O, Herndon DN, et al. Burn Trauma Acutely Increases the Respiratory Capacity and Function of Liver Mitochondria. Shock. 2018. Apr;49(4):466–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cree MG, Fram RY, Herndon DN, et al. Human mitochondrial oxidative capacity is acutely impaired after burn trauma. Am J Surg. 2008. Aug;196(2):234–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coletta C, Modis K, Szczesny B, et al. Regulation of Vascular Tone, Angiogenesis and Cellular Bioenergetics by the 3-Mercaptopyruvate Sulfurtransferase/H2S Pathway: Functional Impairment by Hyperglycemia and Restoration by DL-alpha-Lipoic Acid. Mol Med. 2015. Feb 18;21:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen JJ, Cummins CB, Radhakrishnan RS. Burn-Induced Cardiac Mitochondrial Dysfunction via Interruption of the PDE5A-cGMP-PKG Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Mar 28;21(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubattu S, Forte M, Raffa S. Circulating Leukocytes and Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: A State of the Art. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:2650429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Pol A, van Gilst WH, Voors AA, van der Meer P. Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: past, present and future. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019. Apr;21(4):425–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton JW, White DJ, Maass DL, et al. Antioxidant vitamin therapy alters burn trauma-mediated cardiac NF-kappaB activation and cardiomyocyte cytokine secretion. J Trauma. 2001. Mar;50(3):397–406; discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha VC, Franca LS, de Araujo CF, et al. Protective effects of mito-TEMPO against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016. Mar;77(3):659–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ni R, Cao T, Xiong S, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species with mito-TEMPO reduces diabetic cardiomyopathy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016. Jan;90:12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owada T, Yamauchi H, Saitoh SI, et al. Resolution of mitochondrial oxidant stress improves aged-cardiovascular performance. Coron Artery Dis. 2017. Jan;28(1):33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S, Wu H, Han D, et al. A Novel Mechanism of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Mediated Protection against Sepsis: Restricting Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages by Increasing Mitophagy and Decreasing Mitochondrial ROS. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;3537609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding W, Liu T, Bi X, Zhang Z. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Mito-Tempo Protects Against Aldosterone-Induced Renal Injury In Vivo. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44(2):741–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shetty S, Kumar R, Bharati S. Mito-TEMPO, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, prevents N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019. May 20;136:76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mascarenhas DD, Elayadi A, Singh BK, et al. Nephrilin peptide modulates a neuroimmune stress response in rodent models of burn trauma and sepsis. International journal of burns and trauma. 2013;3(4):190–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhan A, Sirker A, Zhang J, et al. High-frequency speckle tracking echocardiography in the assessment of left ventricular function and remodeling after murine myocardial infarction. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2014. May;306(9):H1371–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen JJ, Porter C, Garg NJ. Inhibition of NFE2L2-Antioxidant Response Element Pathway by Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Contributes to Development of Cardiomyopathy and Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Chagas Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017. Sep 20;27(9):550–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen JJ, Garg NJ. Manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency exacerbates the mitochondrial ROS production and oxidative damage in Chagas disease. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2018. Jul;12(7):e0006687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen JJ, Gupta S, Guan Z, et al. Phenyl-alpha-tert-butyl-nitrone and benzonidazole treatment controlled the mitochondrial oxidative stress and evolution of cardiomyopathy in chronic chagasic Rats. J Am Coll Cardiol. United States; 2010. p. 2499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen JJ, Cummins CB, Szczesny B, Radhakrishnan RS. Cardiac Dysfunction after Burn Injury: Role of the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC1alpha-NFE2L2-ARE Pathway. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. Apr;230(4):562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DP. Redefining oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006. Sep-Oct;8(9–10):1865–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pias EK, Ekshyyan OY, Rhoads CA, et al. Differential effects of superoxide dismutase isoform expression on hydroperoxide-induced apoptosis in PC-12 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003. Apr 11;278(15):13294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hundeshagen G, Herndon DN, Clayton RP, et al. Long-term effect of critical illness after severe paediatric burn injury on cardiac function in adolescent survivors: an observational study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017. Dec;1(4):293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard TS, Hermann DG, McQuitty AL, et al. Burn-induced cardiac dysfunction increases length of stay in pediatric burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2013. Jul-Aug;34(4):413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams HR, Baxter CR, Parker JL. Contractile function of heart muscle from burned guinea pigs. Circ Shock. 1982;9(1):63–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams HR, Baxter CR, Izenberg SD. Decreased contractility and compliance of the left ventricle as complications of thermal trauma. Am Heart J. 1984. Dec;108(6):1477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maass DL, Hybki DP, White J, Horton JW. The time course of cardiac NF-kappaB activation and TNF-alpha secretion by cardiac myocytes after burn injury: contribution to burn-related cardiac contractile dysfunction. Shock. 2002. Apr;17(4):293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratchford SM, Clifton HL, Gifford JR, et al. Impact of acute antioxidant administration on inflammation and vascular function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2019. Nov 1;317(5):R607–R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herndon D, Capek KD, Ross E, et al. Reduced Postburn Hypertrophic Scarring and Improved Physical Recovery With Yearlong Administration of Oxandrolone and Propranolol. Ann Surg. 2018. Sep;268(3):431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen JJ, Cummins C, Radhakrishnan RS. Sildenafil Recovers Burn-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Cells. 2020. Jun 3;9(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C, Zhang J, Xue M, et al. SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin attenuates myocardial oxidative stress and fibrosis in diabetic mice heart. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019. Feb 2;18(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cree MG, Newcomer BR, Herndon DN, et al. PPAR-alpha agonism improves whole body and muscle mitochondrial fat oxidation, but does not alter intracellular fat concentrations in burn trauma children in a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2007. Apr 23;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter C, Herndon DN, Borsheim E, et al. Uncoupled skeletal muscle mitochondria contribute to hypermetabolism in severely burned adults. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014. Sep 1;307(5):E462–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takimoto E Cyclic GMP-dependent signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ J. 2012;76(8):1819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura T, Ranek MJ, Lee DI, et al. Prevention of PKG1alpha oxidation augments cardioprotection in the stressed heart. J Clin Invest. 2015. Jun;125(6):2468–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pifarre P, Prado J, Baltrons MA, et al. Sildenafil (Viagra) ameliorates clinical symptoms and neuropathology in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2011. Apr;121(4):499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nunes AR, Sample V, Xiang YK, et al. Effect of oxygen on phosphodiesterases (PDE) 3 and 4 isoforms and PKA activity in the superior cervical ganglia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;758:287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falkenberg M Mitochondrial DNA replication in mammalian cells: overview of the pathway. Essays Biochem. 2018. Jul 20;62(3):287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young MJ, Copeland WC. Human mitochondrial DNA replication machinery and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016. Jun;38:52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012. Sep 20;367(12):1098–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bosch-Presegue L, Vaquero A. Sirtuins in stress response: guardians of the genome. Oncogene. 2014. Jul 17;33(29):3764–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sebastian C, Satterstrom FK, Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R. From sirtuin biology to human diseases: an update. J Biol Chem. 2012. Dec 14;287(51):42444–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]