Abstract

The decisions of where and how people want to spend their leisure time have a direct effect on the tourism industry, their well-being, and their happiness. Stemming from the social comparison theory, the present study investigates the impact of couple holiday decision tactics on their emotional well-being and the satisfaction and the mediating effect of emotional well-being on the relationship between holiday decision tactics and couple satisfaction. The fundamental framework was examined using 513 questionnaires distributed online, to married couples in Turkey. The results of path analysis were obtained using SPSS and AMOS software. Results showed those decision tactics significantly and positively affect emotional well-being and couple satisfaction. Furthermore, the study confirmed that emotional well-being mediates the relationship between holiday decision tactics and couple satisfaction. This study contributes to the discussion on the effect of both partners' holiday decision tactics on their emotional well-being and their satisfaction.

Keywords: Holliday decision tactics, Emotional well-being, Couple satisfaction, Vacation, Turkey

Introduction

A variety of individual decisions relating to the consumption, life, health, job, and family life are faced by individuals. While many options have a small contribution and are regularly made, others are far more complex (Crozier et al., 1997), entail great costs, and have far-reaching effects (Kroesen & Handy, 2014). Therefore, trying to get insights on how individuals, especially partners in a marital or couples relationship, make their choices must not be overlooked in the couple's lifetime existence and also in the leisure industry. In addition to the precise travel experience, the joy of planning for and hoping for a holiday are occasions of family life that are not worth handling with utmost concern and considerations. Family holiday making reveals a discrepancy across the cycle of family life. In general, people with younger kids take fewer trips and the trips frequency increases as the kids get older. There is wide-ranging literature that addresses problems such as tourism motivation. To try to influence or predict choices, it is necessary to know how these decisions are made (Mottiar, & Quinn, 2004). Paradoxically, most researches related to consumer decision-making are based on two conventions. Firstly, the consequences of individual decisions are a result of the availability of choices to make. Second, these choices are the result of individual desires, values, and attitudes (Simpson et al. 2012). O ur preferences, however, are also influenced by interpersonal relationships, and the significant decisions often influence where to go, what to eat, or where to spend Christmas and other leisure vacations (Cavanaugh, 2016). The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of decisions taken in a couple or marital relationship through mutual agreement between the two partners. The process of making decisions, especially when it comes to decisions that are approved by more than one person, like couples as the case of this study, is a phenomenon that consumers have to deal with more often in their daily lives. These decision-making processes can range from very simple to complex situations. Consequently, it suffices to say that having the ability to resolve the complexities of decision-making efficiently in people's everyday social life is noteworthy in helping them to realize a better quality of life. In line with the previous sentence, the main purpose of the present study is to investigate the impact of couple holiday decision tactics (HDT) on their emotional well-being (EWB) and couple satisfaction (CS). Furthermore, the study aims to examine the indirect effect of HDT on CS through EWB. In this case, EWB is considered to mediate the relationship between HDT and CS.

Decisions as to what people want to do with their leisure time, where they want to spend it, and how much funding they are willing to allocate to such activities all have a direct effect on the tourism industry, and this also affects the well-being and even happiness of families, especially couples. Annual holidays, in terms of budgets, time, and job commitments, are an important part of many families' leisure activities. Over the last century, the growth of family holidays has been marked by a growing ability to explore and experience international travel, and the creation of package holidays has been greatly encouraged. (Cohen, 1995).

For couples today, travel-related decisions are common and generally even-handed process. However, prior decision-making studies are usually focused on the individual decision-making of each member providing self-reports of their supposed effect on decisions (Howard & Madrigal, 1990; Mottiar & Quinn, 2004; Decrop, 2008; Jenkins, 1978).

The up-to-date studies on tourism marketing predominantly discover satisfaction (Iniesta-Bonillo et al. 2016; Prebensen et al., 2016) and the desire to revisit destination (Stylos et al., 2017; Tan & Wu, 2016). On the other hand, research on vacation decision-making related to married couples’ is limited (Wijaya, & Widyaningsih, 2021). Vacation decision-making for married couples could be achieved through discussions or designating partners to select options. The outcome of the selection should be unanimously agreed upon by both partners regardless of whether it is the husband or wife who made the decision. Studies on couples’ vacation decisions need to be investigated further, particularly for married couples. There are numerous categorizations of married couples’ purchasing decisions such as autonomy, dominance, and syncretic (Razzouk et al., 2007). Husband and wife’s travel decisions are considered under the syncretic category, where discussions take place well ahead of time to ascertain vacation destination, and different suggestions are brought together for unanimous conclusions.

In the current research, the decisions of both partners are considered to be shared or better still, the decisions of one partner are not objected to or debated. That is to say, the decision of one partner is accepted or considered by the other partner on the contrary. Prior research used a quasi-experiment to explore the complexities related to the joint decision-making practice by watching couples make choices about a real overnight stay at a luxury resort in real time (Smith et al., 2017). Our research explores how the joint decision-making process shifts due to the experience of couples with each other, the duration of the decision-making process, and the types of strategies used to make travel-related choices are discussed. Opinion of decision-making by couples gives room for a greater insight into the experience of the couple in decision-making to prevent conflict. Endorsements are given on how these results can be made practical to hospitality and travel-related marketing strategies. The decision-making of family vacations will remain a significant field of study as it can be related to the marketing of hospitality and tourism, and the root of this research can be traced to past studies according to Jenkins (1978). His research showed the majority of travel choices, including prominent decisions as to where to travel, when to travel, and the amount of money to spend where the decision of the husband is dominated. In contrast with our research, and drawing to the social comparison hypothesis, authors aim to explore important decisions about where to go, when to travel, and how much to spend, where all partners agree unanimously and no partner decides individually. Our research explored the influence of couple holiday decision tactics on their satisfaction and their emotional well-being (EWB). Couples are quite safe and pleasant when, as in the case of the present research, both parties often agree on what they do, particularly on holiday decisions. Though the definition of family holidays does not in all situations involve the establishment of facilities for tourism, it is a popular practice. Numerous researches characterize this situation as a series of buying decisions with the overall purpose of having quality time together in a position other than where the family currently lives, that is to say, other than their home to rest and relax (Fu, Lehto, & Park, 2014; Litvin, Xu, & Kang, 2004). A shared understanding between the two partners should be this purchasing decision as mentioned above and the holiday decision as our study seeks to analyze. This joint decision-making arrangement is very necessary and beneficial in the lives of couples since it contributes to a state of happiness that is better defined in the present study in terms of well-being in general and EWB in particular. These decision-making techniques would give rise to happy relationships between couples. The EWB suggests optimal individual functioning and drives short- and long-term peak performance. (Fredrickson, 2004; 2014: Newman Tay). Experienced enjoyment or hedonistic well-being is often referred to as emotional well-being (EWB).

The EWB describes the emotional consistency of the daily experience of an individual and relates to the intensity and frequency with which an individual is perceived. (2010 by Kahneman and Deaton). In recent years, the implication of accepting the correlation between the supposed level of well-being of individuals and the positive relationship between couples, especially in marriage, has continued in modern literature (Helms, 2013). The subjective well-being, awareness, and emotional satisfaction of life determine the apparent degree of the well-being of individuals. (In Keyes et al. 2002). Ou r research shows that the well-being of the EWB, as in the context of the current study, has a positive effect on couples' satisfaction or marital satisfaction. It has been found that marital happiness is narrowly related to the financial benefits of marriage, one of which is the practice of having a joint income and account, which makes the family's monetary accomplishments easier (Stimpson et al. 2012). On e of the most important sources of relational maintenance, a state of being happy or promotion for human performance, particularly in older adults, has long been considered to be marital relationships satisfaction. (2005 by Bookwala & Franks; 2004 by Okabayashi et al.). Recognizing the function of marital satisfaction is affected by individual emotive states (Fincham, Beach, Harold, & Osborne, 1997), preceding researches have examined different causative factors (Stutzer & Frey, 2006). Firstly, how married partners interact and communicate with each other in a positive sense is a significant predictor of their joint marital satisfaction (Caughlin, 2002). Although the absence or limitation of communication amongst couples in marriage reduces marital satisfaction, active communication could boost marital satisfaction, irrespective of whether a topic is important or trivial. Specifically, even if married couples speak out their marriage frustration and annoyance to each other, in a manner that could lead to marital grief in some situations, it still helps to reduce emotional distance and tension. As a result, their marital satisfaction will still be impacted positively, (Addis & Bernard, 2002).

Although the link between other factors and well-being has been well-researched, such as self-control and well-being (Okabayashi, 2020), EWB, solidarity, and residents' tourist attitude (Wang et al. 2020), mi nimal studies have explored the complex mechanism of general well-being among couples who regularly participate in recreational activities (Rojas-de Gracia and Alarcón-Urbistondo 2016). Fu rthermore, a great number of available studies confirmed that tourism products are multifaceted since they consist of a wide range of simple products supplied by several suppliers. (Kim et al., 2007), with every family member likely to assume a dissimilar role which to an extent depends on the sub-decision being measured (Alonso-Rivas & Grande-Esteban, 2010). However, considering all necessary attention given to this line of study, there are still some considerable levels of encounters posed by established studies. More so, the findings are not always consistent and, in some situations, they are more than less inconsistent. For example, even though some authors assume that it is the woman's responsibility to look for tourist information and holiday options (Howard & Madrigal, 1990; Mottiar & Quinn, 2004), other scholars accomplished the man to be in the better position to do so (Decrop, 2008; Jenkins, 1978). Besides, in all respects, the same magnitude was not examined (Rojas-de Gracia & Alarcón-Urbistondo, 2016). That is to say, there is still no general agreement on the findings. Thus, both the joint effort of the couple and the agreement to decide on a family vacation of equal intensity are taken into account in the current analysis, which will result in the mutual happiness of the couple and the EWB for both couples. As a consequence, the study has the following goals:

The effect of couple HDT on couple EWB

The effect of couple EWB on their satisfaction

The effect of couple HDT on their satisfaction

And last but not the least, the mediating effect of EWB on the relationship between HDT and couple satisfaction

Literature review and theoretical framework

Social comparison theory

Social comparison theory, first published in 1954, was kept alive by Schachter’s paper on affiliation and emotions. Even after this date, the social comparison has attracted great interest because it forms the basis of self-evaluations and a wide range of social psychological concerns (Goethals, 1986; p. 261). Social comparison theory is also important for social life. The need to compare oneself with others is very old and recognizable. According to Festinger, people persist in their values and attitudes and at the same time, they desire to be approved by others. However, it is so hard to act objectively. As a result, people are biased while comparing themselves to others. Individuals may also compare themselves with others for self-improvement and self-esteem (Buunk and Gibbons, 2007; Dijkstra et al., 2010). White and Lehman (2005) state that Western people seek social comparison in terms of self-enhancement motives. On the contrary, Eastern people engage in social comparison for different reasons such as monitoring the social environment, evaluating the self, feeling a sense of connectedness with others, and improving the self.

Social comparison theory considers being a group or family member on decision-making behavior. For example, as far as possible, couples don't make their decisions without taking wife's or husband's advice, because the joint utility should be considered while making decisions (Kirchler, 1993, 1995). Cultural background is another influencing factor in social comparison processes. In general, Western and Eastern cultures differ concerning individualism or collectivism. In other words, Westerns tend to be independent, individualistic, and autonomous while interdependence and collectivism predominate in western societies. Interdependent individuals are known to be more interested in relationships, roles, and social duties. They focus on collective goals rather than personal ones. They care about how others feel, think, and behave (Hofstede, 1980; Triandis, 1989; Heine, 2001; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Although both genders with different interests have some responsibilities about purchasing decisions in traditional Turkish culture, compromise and persuasion appear as the two most significant tactics while making decisions to purchase holidays between couples (Kozak, 2010, p. 493). Meanwhile, according to Hofstede (2001), the structure of purchasing decisions in Turkey has transformed due to the increasing economic power of females within the family. Therefore, couples tend to cooperate with or persuade the partner throughout the decision-making process.

Holiday decision tactics

Decision-making, individually and collectively, affects consumer behavior in buying basic products and services and holidays as well. There are many internal and external factors (e. g. gender, income, marital status) on the holiday-taking decision (Kozak, 2010; Um & Crompton, 1990; Woodside & Lysonski, 1989). Being a family member is another noteworthy factor in making a holiday decision. In the decision-making process, each of the couples plays different roles as initiator, influencer, or decider (Wang et al., 2004, 183). Existing literature dates back to the 1970s. Myers and Moncrief (1978) found that among younger couples, wives were more dominant during making a holiday decision, while couples generally made a joint decision including route, destination, and accommodation.

In the study in Dublin, Ireland, Mottiar and Quinn (2004) also revealed that holiday decisions were made jointly in terms of where and when to go and how much to spend, but women had the leading role in initiating the idea of going on a holiday and collecting the information. Kozak (2010) confirmed that compromise is a commonly used tactic for holiday taking decisions, followed by persuasion, and is also positively associated with tourist satisfaction A recent study suggested that couples followed a joint holiday decision-making process; however, women's level of education and work situation were the most influential variables on holiday decision (Rojas-de-Gracia et al., 2018). Although the husband and wife are the chief decision-makers, the child's influence cannot be ignored about tourism products and services and at different decision stages (Howard and Madrigal, 1990; Wang et al., 2004).

Emotional well-being

Well-being is a commonly used word related to human daily life and activities (Smith and Diekmann, 2017, p. 1). According to World Health Organization (2009), emotional well-being is defined as a state of well-being in which the individual can cope with stress and work productively. In the case of emotional well-being, the individual is expected to contribute to the community. Emotional well-being generally refers to happiness, being undepressed, and confidence. In this regard, feeling comfortable and relaxed, managing and controlling emotions, and coping with challenges are all considered contributory factors to a positive sense of EWB (Coverdale and Long, 2015). The holiday is another necessity for human well-being because of the opportunities provided for recreation, relaxation, self-improvement, self-reliance, bonding, and many other benefits.

Whenever an individual takes a holiday, some psychological needs are known to be satisfied. And this is likely to impact the individual's mental health, physical health, life satisfaction, and even personal growth positively (Tinsley and Eldredge, 1995; Mélon et al., 2018). Gilbert and Abdullah (2002) revealed that there are significant differences between the holiday-taking group and the non-holiday-taking group in terms of well-being. The holiday-taking group is also happier with their family, economic situation, and health domains compared to the non-holiday-taking group. It is argued that holiday has affected the individuals' level of hedonism positively, thereby increasing their well-being, and this makes them feel much happier. In the study conducted on students aged between 12 and 15 years by Gao et al. (2020), it was also found that traveling with family influences the life satisfaction and contentment with the school of adolescents. Although there is a short-term lift-up effect of family holiday travel on the well-being of adolescents, they have significantly higher post-holiday well-being than their non-traveling counterparts.

Couple satisfaction

An individual's emotional state of being in his or her married life is generally defined as couple satisfaction (Ward et al., 2009; p. 415). Perceiving unfavorable circumstances may lead to marital dissatisfaction. Particular factors such as depression, aggressiveness, financial problems, work stress, the way of communication between couples, and taking some responsibilities concerning child-rearing are among the stimulus to trigger dissatisfaction (Amato et al., 2016: 351). Brassard et al. (2009) found that anxiety and avoidance, as impediments to attachment, are often associated with couple dissatisfaction. Couples' perception of attachment anxiety and avoidance causes the experience of conflict. Couple satisfaction focuses on marital relationships depending on individuals' motivational levels. Fulfillment of some psychological needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness has an important role in couple satisfaction (La Guardia et al., 2000; La Guardia & Patrick, 2008). Depression in married women with younger age, lack of autonomy in marriage decisions, marital rape, and domestic abuse by in-laws are among the elements that give rise to undesired consequences concerning couples' bonds (Ali et al., 2009).

On the contrary, religiosity and having a child have a positive impact on marital satisfaction for couples (Kieran, 2001; Lee et al., 2001). Fatima and Ajmal (2012) also found that similarities of religious sects, satisfaction, compromise, love, care, trust and understanding, communication, forgiveness, relation with in-laws, and family structure are some important factors triggering a happier and lasting marriage. Recent studies have also revealed a positive relationship between family travel and family well-being. Family travel has been recognized as an effective means for family members to improve communications and to strengthen family bonds (Lehto et al., 2009, 2012; Durko & Petrick, 2013).

Research hypotheses

Several scholars have examined and confirmed that shared leisure experiences and activities have an important role in couple satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2006; Dew & Wilcox, 2011), because researches on the relationship between well-being and tourism reveal that travel contributes to the favorable experiences of individuals in terms of health, well-being, and life satisfaction (Chen and Petrick, 2013; Pyke et al., 2016). Lengiezaa et al. (2019) fou nd that travel experiences contribute to one’s overall well-being and quality of life when considered from the eudaimonic aspects. According to Smith and Diekmann (2017), tourism experiences trigger hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. For example, it is suggested that more hedonic well-being can be gained from wellness tourism, whereas spiritual tourism brings more eudaimonic experiences (Voigt et al., 2011).

Individuals who have high levels of emotional well-being are often happier in marriage, friendship, and work (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Brown (2013) also suggests that tourism allows individuals to embrace their true self, freedom and to reduce anxiety. In the meantime, it is clearly stated that the leisure satisfaction of individuals is a significant antecedent of marital satisfaction (Agate et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2006; Ward et al., 2014). Thus, holiday take has a strong relationship with the life satisfaction of individuals and marital satisfaction among couples (Mactavish & Schleien, 1998; Shaw & Dawson, 2001; Zabriskie & McCormick, 2003). There are many studies, indicating that couple leisure activities enhance couple communication; decrease stress level; and increase marital satisfaction, especially when decisions are made in mutual agreement (Claxton & Perry-Jenkins, 2008; Schneider et al., 2004; Holman & Jacquart, 1988) and leisure satisfaction is a strong positive indicator of marital satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2006; Ward et al. 2014). Mu ch literature on consumer behavior focuses on gender roles or the influence of children while decision-making. Considering from the viewpoint of decision-making in holiday planning, the husband-dominant or wife-dominant process has been observed. Persuading or intimidating each other or giving priority to the other spouse could be tactics used to decide holiday details. However, while deciding holiday details, compromise is thought of as a common tactic among couples for satisfaction Wang et al., 2004; Kozak, 2010; Ward et al., 2014). The last statement supports and concords our study, on the fact that decisions should be taken by both partners, or taken by one partner and supported by the other without any conflicts.

In the study on Turkish families, it was found that holidays with families contributed to family satisfaction from the perspectives of parents and females; especially, studies examining holidays with family in traditional societies like Turkish society emphasize cultural differences because of their effects on individuals’ life and holiday satisfaction (Aslan, 2009; p. 157–158), because, in Turkish society, married men are perceived through gender role stereotypes, e.g., father, householder. On the other hand, married women are perceived through gender roles, e.g., self-sacrificing, mothers, and housewives. Thus, all of these roles are head of personality traits and this leads to strengthening family bonds (Sakallı Uğurlu et al., 2018).

Based on the above discussion, the present study proposes the following hypotheses.

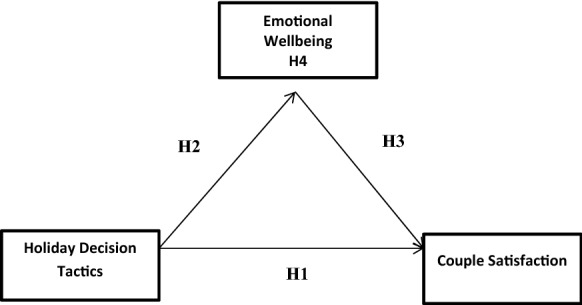

H1 Holiday decision tactics will positively CS.

H2 Holiday decision tactics will positively affect EWB.

H3 EWB will have a positive effect on CS.

H4 EWB will mediate the relationship between HDT and CS.

Research model

See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study model

Methodology

Data were collected between May 2020 and August 2020 through an online survey because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Non-random and snowball sampling designs were used and 513 volunteer married people who take a holiday annually were reached in the study. Within the context of the study purpose, participants were asked to complete the questionnaire consisting of the holiday taking decision items, emotional well-being items, and couple satisfaction items to evaluate their status via holiday experiences.

Measure ıtem

All items were written in English, translated to Turkish, and later back-translated to English by a native speaker (Brislins 1980) to make sure the meaning of the items are not altered. To measure holiday decision tactics of couples, the scale in the study by (Kozak, 2010), benefiting from (Kirchler, 1993, 1995; Jarboe; 1996) was used. A sample item includes "We made our final decision through coercion." To assess levels of the emotional well-being of participants, this study used an emotional well-being scale with five items, adopted from the previous studies in the tourism literature (Kim et al., 2016; Kolakowski, 2013). A sample item for emotional well-being was "Thinking about my marriage makes me feel calm and peaceful." Couple satisfaction was measured using "The Couples Satisfaction Index" with 18 items by Funk and Rogge (2007). A sample item for couple satisfaction was "I feel like part of a team with my partner." The five-point Likert scale was used to measure all of the items with responses ranging from one to five, where one equals strongly disagree and five equals strongly agree. Finally, 7 demographic questions were asked regarding gender, age, education level, years of marriage, numbers of children, breadwinner, and holiday frequency.

The result of the study and data analysis

Table 1 represents the demographic variable of the respondents. The respondents of the hotel destination tactics were male 321(62.6%) and female 192 (37.4%); also the age distribution of their respondents was from 18 to 24 (6); the ages of the respondents that were between 25 and 31 were 92(17.9%). Also, among the respondents, the ages between 32 and 38 were the highest with 173(33.7%). Lastly, 53 years and above were 41(8.0%). All the respondents have had a formal education at some point in their life. The lowest ranging from elementary 8 (1.6%) and the highest was bachelor 206 (39.6%). Among the respondents, more than half of them have 1–3 children 385(75.0%), and also the spouse shares the responsibility equally 364(71.0%). Finally, all the respondents have traveled at least once a year.

Table 1.

Respondents profile (n = 513)

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 321 | 62.6 |

| Female | 192 | 37.4 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 6 | 1.2 |

| 25–31 | 92 | 17.9 |

| 32–38 | 173 | 33.7 |

| 39–45 | 124 | 24.2 |

| 46–52 | 77 | 15.0 |

| 53 and above | 41 | 8.0 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

| Educaiıon | ||

| Elementary | 8 | 1.6 |

| High School | 61 | 11.9 |

| Associate Degree | 35 | 6.8 |

| Bachelor Degree | 206 | 39.6 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

| Year of Marriage | ||

| 0–1 | 39 | 7.6 |

| 2–6 | 149 | 29.0 |

| 7–11 | 136 | 26.5 |

| 12–16 | 68 | 13.3 |

| 17–21 | 44 | 8.6 |

| 21 and above | 77 | 15.0 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

| Number of Children | ||

| No Child | 126 | 24.6 |

| 1–3 | 385 | 75.0 |

| 4 and above | 33 | 0.4 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

| Breadwinner | ||

| Just me | 72 | 14.0 |

| Just my spouse | 77 | 15.0 |

| Dual breadwinner | 364 | 71.0 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

| Holiday Frequency | ||

| Once in a year | 276 | 53.8 |

| Twice in a year | 149 | 29.0 |

| More than twice in a year | 88 | 17.2 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

Validity and reliability

The study establishes the convergent and discriminate validity by using the loading.

Standardized loadings, composite reliability score (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct were within the acceptable values 0.489, 0.836, and 0.678, respectively (see Table 2). The square of the correlation between two sets of the construct of the variables was less than their average variance extracted; therefore, there was evidence of discriminate validity. Also, the composite reliability scores were 0.823, 0.911, and 0.714, respectively. Furthermore, because of cross-loading and insignificant loading, six items were deleted from holiday decision tactics, three items from emotional well-being, and four items from couple satisfaction. Above all, all the remaining loadings were above the threshold 0.70 (Alola et al. 2019) confirming the discriminant validity of the data (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Finally, we checked for multicollinearity via variance inflation factor (VIF) (couple satisfaction, 1.041; emotional well-being, 1.074; holiday decision tactics, 1.159). According to Diamantopoulos and Siguaw (2006), VI F should not exceed the threshold of 3.3; our result shows that all were below the suggested threshold; therefore, multicollinearity was not an issue in this study (Hair et al., 2011).

Table 2.

Loadings and measurement properties

| Construct | Standardized loadings | CAlpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holiday Destination Tactics | 0.650 | 0.489 | 0.823 | |

| HDT 1 | 0.723 | |||

| HDT 2 | 0.681 | |||

| HDT 3 | 0.646 | |||

| HDT 4 | 0.744 | |||

| Emotional Well-being | 0.858 | 0.836 | 0.911 | |

| EWB 5 | 0.918 | |||

| EWB 6 | 0.911 | |||

| Couple Satisfaction | 0.965 | 0.676 | 0.714 | |

| CS 7 | 0.870 | |||

| CS 8 | 0.868 | |||

| CS 9 | 0.859 | |||

| CS 10 | 0.856 | |||

| CS 11 | 0.844 | |||

| CS 12 | 0.833 | |||

| CS 13 | 0.832 | |||

| CS 14 | 0.832 | |||

| CS 15 | 0.815 | |||

| CS 16 | 0.790 | |||

| CS 17 | 0.779 | |||

| CS 18 | 0.774 | |||

| CS 19 | 0.765 | |||

| CS 20 | 0.743 |

C.Alpha = Cronbach alpha, AVE = average variance extracted, CR = composite reliability

Summarily, all initial data checks provided good evidence of a significant relationship among the study variables, thus providing support for further investigation of the proposed hypothesized relationships.

Hypotheses testing

Before proceeding with the result of the correlation, the study test for the normality of the data via skewness analysis. The skewness value for holiday decision tactics is 0.43, emotional well-being − 1.49, and − 0.87 for couple satisfaction. The result shows that the data have a normal distribution and all the values were below the acceptable level of 3.0 (Kline, 2011).

The correlation of observed variables is shown in Table 3. The control variable gender has a positive correlation with holiday decision tactics (0.213** p < 0.05) and couple satisfaction (0.088** p < 0.05). The result shows that holiday decision tactics are correlated with emotional well-being (0.199** p < 0.05) and couple satisfaction (0.262** p < 0.05). The study also accessed the correlation between emotional well-being and couple satisfaction (0.371** p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations

| Correlation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | – | |||

| Holiday Decision tactics | .213** | – | ||

| Emotional well-being | −.079 | −.199** | – | |

| Couple Satisfaction | .088* | −.262** | .371** | – |

| Mean | 1.37 | 2.34 | 4.26 | 1.37 |

| SD | .484 | .697 | .856 | .856 |

**p = 0.01; p* = 0.1

The hierarchical regression analysis is presented in Table 4. The proposed hypothesis that holiday decision tactics will have a positive relationship with couple satisfaction was supported (β = 0.294**p < 0.01); therefore, we accept H1. Also, holiday decision tactics have an impact on emotional well-being as proposed. We accept hypothesis 2 because there is a positive relationship (β = 0.230**p < 0.01). The findings also demonstrated that emotional well-being has a positive impact on couple satisfaction (β = 0.230**p < 0.01). The empirical data support H3.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression result, direct and mediating effect

| Variables | Couple Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step2 | Step3 | |

| Control Variables | |||

| Gender | 0.088** | 0 .150 | 0.163 |

| Independent | |||

| HDT | – | 0.294** | −0.230** |

| Mediator | |||

| EWB | – | – | 0.338** |

| R2 at each step | 0.008 | 0.090 | 0.200 |

| ∆ R2 | – | 0.087 | 0.195 |

| F | 3.98** | 25.36** | 42.36** |

| Sobel test result | z | ||

| HDT→ | EWB→ | CS | 3.3095 |

**Denotes the correlation is significant p < 0.01 and * denotes that correlation is significant as p < 0.05

Hypotheses 4: Emotional well-being acts as a full mediator on the relationship between holiday decision tactics and couple satisfaction. The result reveals that there is a significant impact of R2 (R2 = 0.294, p < 0.01). The model size significantly increased (β = 0.338, p < 0.01); this result lends support to emotional well-being as a full mediator. Therefore, we support H4. Additionally, the mediation test was confirmed with the Sobel test (z = 3.309, p-value = 0.0000) further ascertaining the assumption that H4 is accepted.

Discussion

Adopting from social comparison theory (SCT) (Suls & Wills 1991), this study contributes to the extant literature in the knowledge and the advancement of holiday decision tactics to previous literature. Firstly, our study contributes to emotional well-being (EWB) by contributing to the happiness of couples (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Driving both the short-run and the long-run emotions (Newman et al. 2014), ou r study finds out that emotional well-being has a positive relationship with couple’s satisfaction as in line with previous researchers (Lindauer & Harvath, 2015; Riley et al. 2018).

Interestingly, holiday decision tactics have a positive effect on couple satisfaction and emotional well-being. The topic of holiday decision tactics is a cornerstone in couple satisfaction.

The study of Kahneman and Deaton (2010) reveals that money is not associated with happiness, but poverty causes emotional pain. Our research outcome reveals that holiday decision is essential in couple satisfaction. Additionally, the mediating effect of EWB on SWB and CS shows full mediation. A clear distinction has been made in certain papers concerning the difference between subjective well-being and emotional well-being (Puczkó and Smith 2011). Ho liday tactics decision of couples affects their emotional well-being either positively or negatively. The mediating role of EWB in this study triggers couple satisfaction since is feeling about one’s personal life (Zhu & Fan, 2018). Our study is in line with the study of Diener and Chan (2011) that emotional well-being affects overall satisfaction. Social interaction among the couple increases their overall satisfaction (Kim et al., 2013), which interacts with the positive aspect of emotional well-being. In this token, we posit that when an individual trips with family members, especially one’s spouse, there is a level of psychological benefit attached to such a holiday. Take, for instance, our study found a positive relationship between holiday tactics and couple satisfaction; this is in line with the previous study that holiday is likely to impact individual mental health, and growth (Mélon et al. 2018).

Si milarly, for the control variable, age has a positive correlation with holiday decision tactics and couple satisfaction. The study of Gao et al. (2020) found that in checking the ages of adolescence concerning satisfaction, it found out the traveled are happier with life than the none traveled, and the formal life satisfaction increases which increases post-holiday well-being.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present research contributes to the extant literature on how holiday tactics decision influences couple satisfaction. Emotional well-being mediates the relationship between holiday tactics relationship and couple satisfaction.

In Turkeys culture and also everywhere around the world, couple vacation has become a strong yardstick for improving the relationship among married people. Johnson (2005) in the study conducted on 48 married couples in the USA, which indicated that there was a positive relationship between joint couple holiday taking and marital satisfaction. Tse (2014) suggested that traveling paved the way for general well-being, family harmony, and a positive attitude toward life. Also, in the study by Demirbulat et al. (2015), it was asserted that joint holiday taking strengthened family bonding in The Black Sea region, Turkey. Cai et al. (2020) revealed that vacation enhanced marital satisfaction among Chinese couples and also improved subjective well-being.

The increase in separation and abuse (emotional, physical, and mental) has led to the importance of the subject. Several issues exist that affect the bond for the couple; conflict is a prevalent issue among couples. Therefore, this study is significant and influences the way couple manages their relationship.

Theoretical ımplications

The present study attempts to observe big decisions about where to go, when to travel, and how much to spend, based on the social comparison principle, where all partners should mutually agree and no partner decides. Our research explored the influence and satisfaction on their EWB of a couple of holiday decision tactics. The relationship between couples is very healthy and fun when, as in the case of this study, both parties always agree on what they are doing, particularly on holiday decisions. The social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) notes that since there is an intrinsic need for self-assessment, people prefer to associate their abilities and beliefs with those of others. As the study aims to scrutinize, both partners assess and agree on their desires and decisions for their abilities, since one partner's decision is often inadequate to establish a favorable and required environment to achieve the expected well-being that will contribute to their satisfaction. The fundamental assumptions here are that when there are no objective or unbiased parameters available, when there is a lack of knowledge on the abilities and views of the person, and when there are those with similar characteristics, social comparisons are likely to occur.

Individuals will make some comparisons of their views and beliefs to those of other members of the community, such as tourists at a particular holiday resort or tourists as a whole, to collect knowledge about their relationship within that group. As the study examines, individual partners may compare their own beliefs and views with each other, as they may not be able to gain sufficient knowledge to make the right choices on an individual basis. This analogy will assist in making better choices. To achieve improved well-being and happiness results, they often compare their joint decision-making, which could be individual decision-making by other couples. Previous research shows that individuals continually apply information from others to themselves (Dunning and Hayes, 1996) and this action is unconscious without weighing the suitability of the comparative object (Gilbert et al., 1995). Social comparisons are seen as an important part of psychological processing that affects people's choices, experiences and behaviors, and the state of well-being (Corcoran et al., 2011). Comparisons between oneself and others, for instance, allow people to measure their performance (Taylor and Lobel, 1989), process complex information (Mussweiler and Epstude, 2009), retain self-esteem (Brown 2013), an d make better decisions. The result of this comparison would have a positive effect on well-being within spouses and groups of couples to make better decisions.

Practical ımplications

As our research shows, holiday decision-making strategies have a clear effect on couples' well-being and satisfaction. They try to determine the opinion of each other as couples compare their ability to make decisions. Since individual data are less powerful than combined data, couples are now seeking ways to merge their abilities and efforts to produce better results in decision-making. The findings would often lead to a better state of well-being and a higher degree of happiness for couples. Well-being is often based on concerns relating to the happy experience and the quality of their lives. In adult life, many people consider marriage to be one of the most significant sources of happiness. Furthermore, this contentment is described by many other cultures as a sense of peace, while another school of thought believes it to be a stable state. Some people equate a sense of intent with joy, while others consider it a simple perception of a state of joy. In most cases, the most common underlying cause of happiness for most individuals in adulthood would be couples or marital relationships. EWB is an experience of happiness for a person (Diener, Lucas, & Oshi, 2002), which describes the quality of life. An individual experiencing the EWB is also experiencing a state of happiness in a nutshell, which will spread to satisfaction. Our research indicated and verified that their state of well-being is positively affected when couples agree on vacation decisions without any objection to each other, and thus, their marital satisfaction is positively affected.

Limitations and recommendations for future explorations

The current study examined the influence of holiday decision tactics on emotional well-being and couple satisfaction; in the context of Turkey, future studies should not only focus on Turkey, but should also extend this study to other cultures and countries in and around the Middle East. This research focused on couples who have at least made a vacation in their couple or marital lifetime. Future research should also consider general marital and couple satisfaction, that is, couples who have not gone for any vacation in their marital life, then just focusing on holiday couples. This research will aim to understand the underlying basis of their happiness other than taking vacations together.

The study used an online data collection method to get the view of respondents about the study constructs. For this reason, the questionnaire might have been filled by couples who have never gone for any vacation, or those whose decisions for vacation were individually evaluated. Future data collection exercise is advised to be done on the field. That is to say, the questionnaire should be distributed to hotels and other holiday destinations directly to couples present so that the exact picture of the study objective should be met.

Also, future studies should focus on those couples whose vacation decisions were mutually agreed on, to better understand their level of well-being and satisfaction. Furthermore, a comparison on the level of well-being and satisfaction between couples who mutually decided on their vacation to couples whose decision was made by either the man or the woman .

Appendix

Questionnaire in English and Turkish translated version

| 1. Emotional well-being (duygusal iyi oluş hali) |

| I feel healthy and happy during holiday |

| Tatilde kendimi sağlıklı ve mutlu hissediyorum |

| I feel emotional well-being when I am on holiday |

| Tatildeyken kendimi duygusal anlamda iyi hissediyorum |

| Marriage plays an important role in making me feel relaxed |

| Evliliğimin kendimi rahat hissetmemde önemli payı var |

| Thinking about my marriage makes me feel calm and peaceful |

| Evliliğim hakkında düşündüğümde kendimi sakin ve huzurlu hissediyorum |

| My marriage plays an important role in making me feel refreshed |

| Evliliğim kendimi dinç/canlı hissetmemde önemli rol oynar |

| 2. Holiday decision tactics (tatil kararı alma biçimleri) |

| We made our final decision by persuading each other |

| Birbirimizi ikna ederek tatil kararı alırız |

| We made our final decision by bargaining with each other |

| Birbirimizle pazarlık ederek/anlaşarak tatil kararı alırız |

| We made our final decision by compromising each other |

| Kendimizden ödün vererek tatil kararı alırız |

| We made our final decision through coercion |

| Birbirimize baskı yaparak tatil kararı alırız |

| We made our final decision by intimidating each other |

| Birbirimizi korkutarak/tehdit ederek tatil kararı alırız |

| We made our final decision by sacrificing our own choice |

| Bireysel isteklerimizden vazgeçerek tatil kararı alırız |

| We made our final decision by giving priority to the other spouse |

| Tatil kararı alırken eşime öncelik veririm |

| We made our final decision by obtaining sellers’ opinions |

| Tatil kararımızı satıcıların önerileri doğrultusunda alırız |

| We made our final decision by obtaining our friends/relatives’ opinions |

| Tatil kararlarımızı arkadaş/akraba önerileri doğrultusunda alırız |

| We made our final decision through the influence of our children |

| Tatil kararı almada çocuklarımız etkilidir |

| 3. Couple satisfaction (Çift memnuniyeti) |

| I still feel a strong connection with my partner |

| Eşimle aramızda hala güçlü bir bağ olduğunu hissediyorum |

| If I had my life to live over, I would marry (or live with/date) the same person |

| Bir daha dünyaya gelsem, yine aynı kişiyle evlenirdim |

| Our relationship is strong |

| Eşimle güçlü bir ilişkimiz var |

| I sometimes wonder if there is someone else out there for me |

| Bazen eşimin benim için doğru kişi olmadığını düşünüyorum |

| My relationship with my partner makes me happy |

| Eşimle aramızdaki ilişki beni mutlu ediyor |

| I have a warm and comfortable relationship with my partner |

| Eşimle sıcak ve rahat bir ilişkimiz var |

| I can’t imagine ending my relationship with my partner |

| Eşimle ilişkimizin bitmesini hayal bile edemiyorum |

| I feel that I can confide in my partner about virtually anything |

| Eşime neredeyse her konuda içimi dökebileceğimi ve güvenebileceğimi hissediyorum |

| I have had second thoughts about this relationship recently |

| Son zamanlarda eşimle/bu ilişki ile ilgili pişmanlıklar yaşıyorum |

| For me, my partner is the perfect romantic partner |

| Eşim mükemmel bir romantik partnerdir |

| I really feel like part of a team with my partner |

| Eşimle gerçekten bir takımın parçası gibiyiz |

| I cannot imagine another person making me as happy as my partner does |

| Hiç kimse eşimin beni mutlu ettiği kadar mutlu edemez |

| We spend enough time together |

| Eşimle birlikte yeterince zaman geçiriyoruz |

| I often think that things between me and my partner are going well |

| Eşimle aramızda her şeyin yolunda olduğunu sıklıkla düşünüyorum |

| My partner meets my needs |

| Eşim ihtiyaçlarımı karşılamaktadır |

| The relationship between us meets our original expectations |

| Eşimle aramızdaki ilişki kişisel beklentilerimizi karşılamaktadır |

| Our relationship is good compared to others |

| Diğer evli çiftlerle kıyasladığımda ilişkimizin iyi olduğunu düşünüyorum |

| My partner and I are fun of each other |

| Eşim ve ben birlikte eğlenebiliyoruz |

Funding

There was no funding associated with this manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available by authors on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marymagdaline Enowmbi Tarkang, Email: memtarkang@tarkang.edu.tr.

Uju Violet Alola, Email: uvalola@gelisim.edu.tr.

Yurdanur Yumuk, Email: yurdanuryumuk@karabuk.edu.tr.

References

- Addis J, Bernard ME. Marital adjustment and irrational beliefs. J Rational-Emot Cognitive-Behav Ther. 2002;20(1):3–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1015199803099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agate JR, Zabriskie RB, Agate ST, Poff R. Family Leisure Satisfaction and Satisfaction with Family Life. J Leis Res. 2009;41(2):205–223. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2009.11950166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F, Israr S, Ali B, Janjua N. Association of various reproductive rights, domestic violence and marital rape with depression among Pakistani women. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(1):77. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alola UV, Olugbade OA, Avci T, Öztüren A. Customer incivility and employees' outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tourism Manage Perspect. 2019;29:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Rivas J, Grande-Esteban I. Consumer Behavior. 6a. Pozuelo de Alarcón: Business & Marketing School ESIC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amato MP, Lundberg N, Ward PJ, Schaalje BG, Zabriskie R. The mediating effects of autonomy, competence, and relatedness during couple leisure on the relationship between total couple leisure satisfaction and marital satisfaction. J Leis Res. 2016;48(5):349–373. doi: 10.18666/JLR-2016-V48-I5-7026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(3):411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan N. An examination of family leisure and family satisfaction among traditional Turkish families. J Leis Res. 2009;41(2):157–176. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2009.11950164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard A, Lussier Y, Shaver PR. Attachment, perceived conflict, and couple satisfaction: test of a mediational dyadic model. Family Relat. 2009;58(December 2009):634–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00580.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW (1980) Cross-cultural research methods. In: Environment and culture (pp. 47–82). Springer, Boston, MA

- Brown L. Tourism: A catalyst for an existential authenticity. Ann Tour Res. 2013;40(1):176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk AP, Gibbons FX. Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2007;102(2007):3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Wang S, Zhang Y. Vacation travel, marital satisfaction, and subjective wellbeing: a Chinese perspective. J China Tourism Res. 2020;16(1):118–139. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2019.1575304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caughlin JP. The demand/withdrawal pattern of communication as a predictor of marital satisfaction over time. Hum Commun Res. 2002;28(1):49–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh LA. Consumer behavior in close relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;10:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Petrick JF. Health and wellness benefits of travel experiences: A literature review. J Travel Res. 2013;52(6):709–719. doi: 10.1177/0047287513496477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton A, Perry-Jenkins MP. No fun anymore: Leisure and marital quality across the transition to parenthood. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70(1):28–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E. Contemporary tourism trends and challenges: Sustainable authenticity or contrived post-modernity? In: Butler R, Pearce D, editors. Change in Tourism, People, Places, Processes. London: Routledge; 1995. pp. 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran K, Crusius J, Mussweiler T. Social comparison: motives, standards, and mechanisms. In: Chadee D, editor. Theories in Social Psychology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Coverdale GE, Long AF. Emotional wellbeing and mental health: an exploration into health promotion in young people and families. Perspect Public Health. 2015;135(1):27–36. doi: 10.1177/1757913914558080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier R, Ranyard R, Svenson O. Decision making: Cognitive models and explanations. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Decrop A. Group decision-making. In: Oh H, Pizam A, editors. Handbook of hospitality marketing management. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2008. pp. 440–470. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbulat ÖG, Saatci G, Avcikurt C. Tatilin aile içi davranışlar üzerindeki etkisinin demografik değişkenler açısından incelenmesi: Doğu Karadeniz Bölgesi’nde bir araştırma. J Travel Hosp Manage. 2015;12(2):42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dew J, Wilcox WB. If momma ain’t happy: Explaining declines in marital satisfaction among new mothers. J Marriage Fam. 2011;73(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00782.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos A, Siguaw JA. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br J Manag. 2006;17(4):263–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2011;3(1):1–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P, Gibbons FX, Buunk AP. Social comparison theory. In: Maddux JE, Tangney JP, editors. Social psychological foundations of clinical psychology. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D, Hayes AF. Evidence for Egocentric Comparison in Social Judgment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(2):213–229. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durko AM, Petrick JF. Family and relationship benefits of travel experiences: A literature review. J Travel Res. 2013;52(6):720–730. doi: 10.1177/0047287513496478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima M, Ajmal MA. Happy marriage: a qualitative study. Pakistan J Soc Clin Psychol. 2012;10(1):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relat. 1954;7(2):117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc. 2004;359(1449):1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Havitz ME, Potwarka LR. Exploring the influence of family holiday travel on the subjective well-being of Chinese adolescents. J China Tourism Res. 2020;16(1):45–61. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2018.1513883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Giesler RB, Morris KA. When Comparisons Arise. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(2):227–236. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D, Abdullah J. A study of the impact of the expectation of a holiday on an individual's sense of well-being. J Vacat Mark. 2002;8(4):352–361. doi: 10.1177/135676670200800406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goethals GR. Social Comparison Theory: Psychology from the Lost and Found. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1986;12(1986):261–278. doi: 10.1177/0146167286123001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: Indeed, a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract. 2011;19(2):139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ. Self as the cultural product: An examination of East Asian and North American selves. J Personal. 2001;69:881–906. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms HM (2013) Marital relationships in the twenty-first century. In: Handbook of marriage and the family (pp. 233–254). Springer, Boston, MA

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Cultural consequences. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Holman TB, Jacquart M. Leisure-activity patterns and marital satisfaction: a further test. J Marriage Fam. 1988;50(1):69–77. doi: 10.2307/352428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DR, Madrigal R. Who makes the decision: The parent or child? The perceived influence of parents or children on the purchase of recreation services. J Leis Res. 1990;22(3):244–258. doi: 10.1080/00222216.1990.11969828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iniesta-Bonillo MA, Sánchez-Fernández R, Jiménez-Castillo D. Sustainability, value, and satisfaction: Model testing and cross-validation in tourist destinations. J Bus Res. 2016;69(11):5002–5007. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarboe S. Procedures for enhancing group decision-making. In: Hirokawa RY, Poole MS, editors. Communication and group decision making. 2. California: Sage; 1996. pp. 345–383. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins RL. Family vacation decision-making. J Travel Res. 1978;16(4):2–7. doi: 10.1177/004728757801600401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HA (2005) The contribution of couple leisure ınvolvement, leisure time, and leisure satisfaction to marital satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Brigham Young University, USA

- Johnson HA, Zabriskie RB, Hill B. The contribution of couple leisure involvement, leisure time, and leisure satisfaction to marital satisfaction. Marriage Fam Rev. 2006;40(1):69–91. doi: 10.1300/J002v40n01_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Deaton A. High income improves the evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(38):16489–16493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: the empirical encounter of two traditions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(6):1007. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieran ST. Understanding the relationship between religiosity and marriage: An investigation of the immediate and longitudinal effects of religiosity on newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2001;15:610–626. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D-Y, Lehto XY, Morrison AM. Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tour Manage. 2007;28:423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Uysal M, Sirgy MJ. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour Manage. 2013;36:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. Spouses’ joint purchase decisions: determinants of influence tactics for muddling through the process. J Econ Psychol. 1993;14:405–438. doi: 10.1016/0167-4870(93)90009-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. Studying economic decisions within private households: a critical review and design for a couple of experiences diary. J Econ Psychol. 1995;16:393–419. doi: 10.1016/0167-4870(95)00017-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011) Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling

- Kozak M. Holiday taking decisions- The role of spouses. Tour Manage. 2010;31(2010):489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroesen M, Handy S. The influence of holiday-taking on affect and contentment. Ann Tour Res. 2014;45:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Guardia JG, Patrick H. Self-determination theory is a fundamental theory of close relationships. Can Psychol. 2008;49(3):201–209. doi: 10.1037/a0012760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Guardia JG, Ryan RM, Couchman CE, Deci EL. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(3):367–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TY, Sun GH, Chao SC. The effect of an infertility diagnosis on treatment-related stresses. Arch Androl. 2001;46:67–71. doi: 10.1080/01485010150211173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto XY, Choi S, Lin YC, MacDermid SM. Vacation and family functioning. Ann Tour Res. 2009;36(3):459–479. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2009.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto XY, Lin YC, Chen Y, Choi S. Family vacation activities and family cohesion. J Travel Tour Mark. 2012;29(8):835–850. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2012.730950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lengiezaa ML, Hunt CA, Swim JK. Measuring eudaimonic travel experiences. Ann Tour Res. 2019;74(2019):195–197. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive effect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mactavish J, Schleien S. Playing together growing together: Parents’ perspectives on the benefits of family recreation in families that include children with a developmental disability. Ther Recreation J. 1998;32:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mélon M, Agrigoroaei S, Diekmann A, Luminet O. The holiday-related predictors of wellbeing in seniors. J Policy Res Tourism Leisure Events. 2018;10(3):221–240. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2018.1470184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mottiar Z, Quinn D. Couple dynamics in household tourism decision making: Women as the gatekeepers? J Vacat Mark. 2004;10(2):149–160. doi: 10.1177/135676670401000205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mussweiler T, Epstude K. Relatively fast! Efficiency advantages of comparative thinking. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2009;138(1):1–21. doi: 10.1037/a0014374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers P, Moncrief L. Differential leisure travel decision-making between spouses. Ann Tour Res. 1978;5(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(78)90009-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DB, Tay L, Diener E. Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. J Happiness Stud. 2014;15(3):555–578. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okabayashi H. Self-regulation, marital climate, and emotional well-being among Japanese older couples. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2020;35(4):433–452. doi: 10.1007/s10823-020-09409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen NK, Kim H (Lina), Uysal M (2016) Cocreation as a moderator between the experience value and satisfaction relationship. J Travel Res 55(7): 934–945. 10.1177/0047287515583359

- Pyke S, Hartwell H, Blake A, Hemingway A. Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tour Manage. 2016;55(2016):94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puczkó L, Smith M (2011) Tourism-specific quality-of-life index: The Budapest model. In: Quality-of-life community indicators for parks, recreation and tourism management (pp. 163–183). Springer, Dordrecht

- Riley GA, Evans L, Oyebode JR. Relationship continuity and emotional well-being in spouses of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(3):299–305. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1248896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzouk N, Seitz V, Capo KP. A comparison of consumer decision-making behavior of married and cohabiting couples. J Consum Mark. 2007;24(5):264–274. doi: 10.1108/07363760710773085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-de Gracia MM, Alarcón-Urbistondo P. Toward a gendered understanding of the influence of the couple on family vacation decisions. Tourism Manage Perspect. 2016;20:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2016.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-de-Gracia MM, Alarcón-Urbistondo P, González Robles EM. Couple dynamics in family holidays decision-making process. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2018;30(1):601–617. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakallı Uğurlu N, Türkoğlu B, Kuzlak A, Gupta A. Stereotypes of single and married women and men in Turkish culture. Curr Psychol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9920-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Ainbinder AM, Csikszentmihalyi M. Stress and working parents. In: Haworth JT, Veal AJ, editors. Work and leisure. London: Routledge; 2004. pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SM, Dawson D. Purposive leisure: Examining parental discourses on family activities. Leis Sci. 2001;23:217–231. doi: 10.1080/01490400152809098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A, Griskevicius V, Rothman AJ. Consumerdecisionsinrelationships. J Consum Psychol. 2012;22(3):304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MK, Diekmann A. Tourism and wellbeing. Ann Tour Res. 2017;66(2017):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WW, Pitts RE, Litvin SW, Agrawal D. Exploring the length and complexity of couples' travel decision-making. Cornell Hosp Quart. 2017;58(4):387–392. doi: 10.1177/1938965517704374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpson JP, Wilson FA, Peek MK (2012) Marital status, the economic benefits of marriage, and days of inactivity due to poor health. Int J Popul Res, 1–6

- Stutzer A, Frey BS. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? J Socio-Econ. 2006;35(2):326–347. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stylos N, Bellou V, Andronikidis A, Vassiliadis CA. Linking the dots among destination images, place attachment, and revisit intentions: A study among British and JOURNAL OF QUALITY ASSURANCE IN HOSPITALITY & TOURISM 141 Russian tourists. Tour Manage. 2017;60:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suls JE, Wills TAE. Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research. Washington DC: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lobel M. Social comparison activity under threat: downward evaluation and upward contacts. Psychol Rev. 1989;96(4):569–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley HEA, Eldredge BD. Psychological benefits of leisure participation: a taxonomy of leisure activities based on their need-gratifying properties. J Couns Psychol. 1995;42(2):123–132. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychol Rev. 1989;96:506–520. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tse TSM. Does tourism change our lives? Asia Pacif J Tourism Res. 2014;19(9):989–1008. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2013.833125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Um S, Crompton JL. Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Ann Tour Res. 1990;17:432–448. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(90)90008-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Hsieh AT, Yeh YC, Tsai CW. Who is the decision-maker: the parents or the child in group package tours? Tour Manage. 2004;25(2004):183–194. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00093-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Berbekova A, Uysal M (2020) Is this about feeling? The ınterplay of emotional well-being, solidarity, and residents’ Attitude. J Travel Res, 0047287520938862

- Ward PJ, Lundberg NR, Zabriskie RB, Berrett K. Measuring marital satisfaction: a comparison of the revised dyadic adjustment scale and the satisfaction with married life scale. Marriage Fam Rev. 2009;45(4):412–429. doi: 10.1080/01494920902828219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PJ, Barney K, Lundberg N, Zabriskie RB. A Critical examination of couple leisure and the application of the core and balance model. J Leis Res. 2014;46(5):593–611. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2014.11950344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya AP, Widyaningsih YA. The role of dyadic cohesion on secure attachment style toward marital satisfaction: a dyadic analysis on couple vacation decision. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour. 2021;22(1):119–142. doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2020.1756022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Lehman DR. Culture and social comparison seeking: the role of self-motives. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;3:232–242. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt C, Brown G, Howat G (2011) Wellness tourists: in search of transformation. Tourism Rev, Vol. 66, No. 1/2 2011, 16–30

- Woodside A, Lysonski S. A general model of traveler destination choice. J Travel Res. 1989;27(1):8–14. doi: 10.1177/004728758902700402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zabriskie RB, McCormick B. Parent and child perspectives of family leisure involvement and satisfaction with family life. J Leis Res. 2003;35:163–189. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2003.11949989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Fan Y. Daily travel behavior and emotional well-being: effects of trip mode, duration, purpose, and companionship. Transp Res Part a: Policy Pract. 2018;118:360–373. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by authors on request.