Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the impact of the incisor position on the self-perceived psychosocial impacts of malocclusion among Chinese young adults.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study included a convenience sample of 17.1- to 22.3-year-old young adults (n = 1005). The five groups represented were normal occlusion as well as incisor Class I, Class II/1, Class II/2, and Class III malocclusion. For clinical assessment, the incisor relationship was evaluated according to the British Standards Institute Incisor Classification, and the self-perception of dental esthetics was assessed using the Psychosocial Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire (PIDAQ). Statistical analysis involved the analysis of variance and Tukey multiple-comparison post hoc tests.

Results:

Psychosocial impacts were different among the five groups for the four PIDAQ domains (P < .001 for all four domains). Statistically significant differences were found between the four malocclusion groups and the normal occlusion group in all four domains (P < .001 for all four domains). Furthermore, statistically significant differences were found between four malocclusion groups.

Conclusions:

All four malocclusion groups had more severe psychosocial impacts than the normal occlusion group in the four PIDAQ domains. Statistically significant differences were also found between the four malocclusion groups; these malocclusion groups ranked by score, highest to lowest, were Class III, Class II/1, Class II/2, and Class I.

Keywords: Malocclusion, Psychosocial impacts, Incisor position

INTRODUCTION

Although orthodontists traditionally consider oral health and function as the main goals of treatment,1,2 social and psychological effects are the key motives for patients to seek orthodontic treatment.3–5 Recently, oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) measures with respect to malocclusion have been studied to measure orthodontic treatment need and outcome.6–13 A previous study indicated malocclusions may contribute to mental health problems, and some patients even needed psychological counseling,14 so it is necessary to understand the relationship between psychosocial impacts and malocclusion in young adults.

In the last few years, several measures have been developed or adapted to measure OHRQoL in regard to malocclusion, including condition-specific oral impacts on daily performances (CS-OIDP),15 oral health impacts profile (OHIP),16,17 14-items short-form oral health impact (OHIP-14),18 the child perception questionnaire (CPQ11-14),19–21 and Rosenberg's self-esteem scale.11,22,23 Only a few of these measures have been specifically developed for malocclusion. The Psychosocial Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire (PIDAQ),24 which was designed specifically for orthodontics, is a self-rating instrument that was used to assess the psychosocial impacts of dental esthetics in young adults. Previous studies have confirmed its validity in different countries with different languages.25–27

On the other hand, the method by which malocclusion is defined is important in studies evaluating OHRQoL with respect to malocclusion. Although previous studies frequently used the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI)9–11,21,25 and Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN)8,23,24,28–30 to define malocclusion, Angle's Classification is most widely used to define malocclusion clinically. The Incisor Classification, which is another important malocclusion classification based on incisor-occlusion relationship, was developed to overcome some of the disadvantages of Angle's Classification.31 Few studies have used Angle's Classification or the Incisor Classification to evaluate OHRQoL in regard to malocclusions.28 However, most patients who seek orthodontic treatment are presumably more concerned about their anterior segments of teeth than their posterior segments. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the relationship between psychosocial impacts measured by PIDAQ and malocclusion classified by the Incisor Classification in a group of Chinese young adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of all 8792 first-year students (17.1 to 22.3 years old, mean 17.9 ± 2.5 years, 5099 men and 3693 women) of Wuhan Textile University attended a general health and an oral health examination program in 2011. Malocclusions were examined and recorded using the Incisor Classification by one of the authors, Dr Xia.Reference needed-ED The incisor relationship was classified according to the British Standard Institute.31

To ascertain intraexaminer reliability in the use of the Incisor Classification, 40 students were reexamined after a period of 2 weeks by the same examiner. The results were tested using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. There was no statistically significant difference between the measurements for reliability (P = .521). The computed intrarater correlation coefficient for repeated measurements was 0.96 (P < .001), which indicated high reliability.

In all, 1404 subjects (16.0%) had individual normal occlusion, 3892 (44.3%) had Class I malocclusion, 2179 (24.8%) had Class II division 1 (Class II/1) malocclusion, 215 (2.4%) had Class II division 2 (Class II/2) malocclusion, and 1102 (12.5%) had Class III malocclusion. Among these, the students excluded from our study were those who (1) had majored in Art Professional, (2) had cleft lip and/or cleft palate, (3) had severe caries and/or periodontal diseases, (4) had undergone previous orthodontic treatment or were currently undergoing orthodontic treatment, or (5) refused to answer the questionnaire.

After these exclusions, the smallest group size included 201 students (Class II/2); hence, a method similar to Bernabé et al.30 was used to standardize the sample size to 201 for the other groups as well, which was done by simple randomization. Total sample size was composed of 1005 individuals.

The study was approved by the Ethics Institutional Review Board of Wuhan University, and each participant provided written informed consent. If participants were under 18 years old, informed consents were signed by their parents.

Self-Reported Questionnaire

The PIDAQ,24 which was developed in English, has four domains: dental self-confidence (DS, 6 items), social impact (SI, 8 items), psychological impact (PI, 6 items), and aesthetic concern (AC, 3 items). Some studies had translated and culturally adapted the original English version into other language such as Portuguese25 and Chinese.26 Although there is a validated Chinese version of PIDAQ,26 our version of Chinese PIDAQ was developed independently. Briefly, according to the procedure proposed by the International Quality of Life Assessment,33 a pilot study similar to that of Sardenberg et al.25 was used to translate, back translate, and culturally adapt the original English version into Chinese. Its validity and reliability were tested on a sample of 296 young adults (161 males and 135 females, age 19.1 to 24.2 years) that were recruited from Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, China. Statistics showed that Cronbach α was .94 for DS, .81 for SI, .79 for PI, and .71 for AC. Intra Class Correlation Coefficient was .90 for DS, .97 for SI , .97 for PI, and .96 for AC. The results indicated that our Chinese version of PIDAQ had satisfactory reliability and validity.

In the present study, the items in DS were scored in a reversed manner to produce a consistent measure of impacts to ensure the same direction of scoring for all questionnaire items.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (SPSS for Windows, version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). One-way analysis of variance was used for the comparisons among the groups, and Tukey multiple comparison post hoc test was used for subgroup comparisons. The results were evaluated within a 95% confidence interval. The statistical significance level was established at P < .05.

RESULTS

One-way analysis of variance revealed statistically significant intragroup differences in all four domains (Table 1; P < .001 for DS, SI, PI, and AC).

Table 1.

Descriptive Results of the Inquiry and Statistics of One-Way Analysis of Variancea

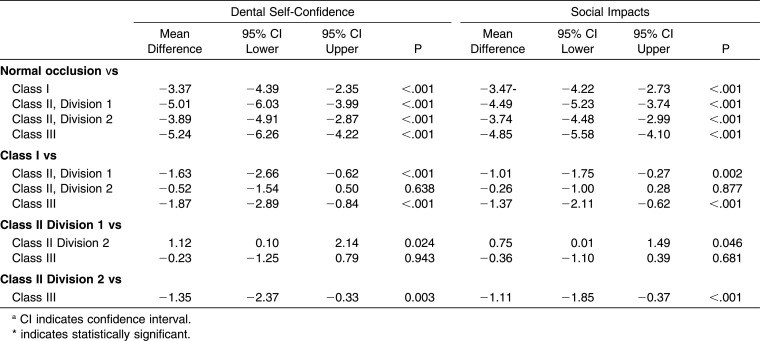

Statistically significant differences were found between all four malocclusion groups and the normal occlusion group in all four domains (Table 2; P < .001 for DS, SI, PI, and AC). Generally, the four malocclusion groups ranked by scores in order from highest to lowest were Class III, Class II/1, Class II/2, and Class I.

Table 2.

Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Post Hoc Tests for Subgroup Comparisons

Table 2.

Extended

The Class III group reported the highest psychosocial impacts among all five groups in all four domains, and the Class II/1 group reported the second highest impacts. However, no statistically significant differences were found between those two groups in the four domains except for AC (Table 2; P=.943 for DS, P=.681 for SI, P=.706 for PI, and P=.026 for AC). The Class III group had more severe psychosocial impacts than the Class I group (Table 2; P<.001 for DS, P<.001 for SI, P<.001 for PI, and P<.001 for AC) and the Class II/2 group (Table 2; P=.003 for DS, P<.001 for SI, P=.006 for PI, and P<.001 for AC) in all four domains. The Class II/1 malocclusion group had more severe psychosocial impacts than the Class I malocclusion group (Table 2; P<.001 for DS, P=.002 for SI, P=.003 for PI, and P=.004 for AC) and the Class II/2 group (Table 2; P=.024 for DS, P=.046 for SI, P=.195 for PI, and P=.036 for AC) in all four domains. The Class II/2 group was mildly more severe than the Class I group in any of the four domains (Table 2; P=.638 for DS, P=.877 for SI, P=.596 for PI, and P=.937 for AC).

DISCUSSION

The subjects of the present study included a young university student group, which was similar to the original instrument.24 We excluded subjects who had undergone orthodontic treatment previously or were currently undergoing such treatment. Furthermore, subjects with severe caries and/or periodontal diseases, subjects with cleft lip and/or cleft palate, and subjects who had majored in Arts Professional were excluded in order to reduce possible interference.

Our results indicated that the psychosocial impacts on subjects in all four malocclusion groups were statistically significantly different from those with normal occlusion. This indicated that psychosocial impacts related to malocclusion occur irrespective of the type of malocclusion, and this finding is consistent with those of previous studies.8,14,21,30,33 Furthermore, the results of the present study demonstrate that PIDAQ is a sensitive index for measuring psychosocial impacts on patients with malocclusion. Similarly, de Paula et al.33 found that 98.3% of subjects showed some level of psychosocial impact from dental esthetics when PIDAQ was used.

An important finding in the present study was that the psychosocial impacts of Class III and Class II/1 patients were similar and more severe than those of Class I and Class II/2 patients. This suggests that the anterior-posterior relationship of the upper and lower teeth is conspicuous and is very important to patients. In other words, the overjet in Class III and Class II/1 is different from that in Class I and Class II/2 patients. The overjet increases in Class II/1 and decreases or reverses in Class III patients, which might induce a protrusion or retrusion profile. These traits, which can be perceived easily by patients, can further influence the psychology of patients. Previous studies34,35 indicate that the overjet is one of the most important traits and might affect the self-dental perception of patients greatly.

In addition, the psychosocial impacts of Class III were more severe than those of Class II/1, although few statistically significant differences were observed between these two groups. This indicated that Class III malocclusion might induce considerably severe psychosocial impacts on patients. Burden et al.14 investigated an orthognathic patients group; results indicated that worse mean scores of the psychological measures were found in the skeletal II patients than skeletal III patients. Their results were different from ours. There were three possible reasons for this. (1) Patients of their study group had severe malocclusions, which needed orthognathic treatment, but most individuals of our study group were with mild to moderate malocclusion. The individuals in the Class II/1 group who might need orthognathic treatment had a less severe malocclusion than those in the Class III group in our study (a judgment by experience, no radiography used in present study), in other words, the severity of deformity of those two groups was different. (2) Class III malocclusion might be less acceptable than Class II /1 in Chinese people. (3) In the present study, the Class II group was divided into Class II/1 and Class II/2 groups. It found that psychosocial impacts were higher in the Class II/1 group, which indicated that the self-perceived psychosocial impacts of patients were different based on those two Class II subdivisions. But in the study of Burden et al.,14 Class II/2 patients were not differentiated from Class II/1 patients, which might reduce the scores of the latter.

Psychosocial impacts of the Class II/2 group were mildly more severe than those of the Class I group, but there were no significant differences between those two groups. The reason is not clear. A previous study indicated that anterior teeth display during smiling might inflect psychosocial impacts measured by PIDAQ,27 too. Excess upper anterior teeth display or gingival display is usually a symptom of Class II/2 patients, but not for Class I and other groups, which may be a possible reason for the increased psychosocial impacts of the Class II/2 group.

It should be noted that scores in every PIDAQ domain showed a wide range in each type of malocclusion, which means that the severity of malocclusion and other factors might influence the self-perception of dental appearance in patients. Although some studies found that psychosocial impacts increased while the severity of malocclusion increased,8,22,29,33 clinical experience and other studies indicated that some patients had severe psychosocial impacts even because of mild malocclusion.36 Therefore, the different impacts of the different types of malocclusion in the present study should be regarded as a generic condition. The psychosocial impacts of patients should be treated individually in the clinic.

Furthermore, effects of socioeconomic status were not studied because this information about patients was not collected. The original author of PIDAQ did not find any differences between men and women with the application of PIDAQ. Hence, the differences between men and women were not evaluated in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

All four groups of subjects with malocclusion had more severe psychosocial impacts than those with normal occlusion in the four PIDAQ domains.

Statistically significant differences were observed among the four malocclusion groups. Generally, the four malocclusion groups ranked by scores in order from highest to lowest were Class III, Class II/1, Class II/2, and Class I.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank colleagues of the School of English, Wuhan University, who contributed to translating and culturally adapting the original English version into Chinese in the pilot study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang M, McGrath C, Hägg U. The impact of malocclusion and its treatment on quality of life: a literature review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006;16:381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt O, Hepper P, Johnston C, Stevenson C, Burden D. Professional perceptions of the benefits of orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2001;23:315–323. doi: 10.1093/ejo/23.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.lbino JE, Cunat JJ, Fox RN, Lewis EA, Slakter MJ, Tedesco LA. Variables discriminating individuals who seek orthodontic treatment. J Dent Res. 1981;60:1661–1667. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600090501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw WC, Addy M, Dummer PM, Ray C, Frude N. Dental and social effects of malocclusion and effectiveness of orthodontic treatment: a strategy for investigation. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14:60–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1986.tb01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt O, Hepper P, Johnston C, Stevenson M, Burden D. The aesthetic component of the index of orthodontic treatment need validated against lay opinion. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24:53–59. doi: 10.1093/ejo/24.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP. Quality of life and its importance in orthodontics. J Orthod. 2001;28:152–158. doi: 10.1093/ortho/28.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. The relationship between normative orthodontic treatment need and oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:426–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0528.2003.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klages U, Bruckner A, Guld Y, Zentner A. Dental esthetics, orthodontic treatment and oral health attitudes in young adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traebert ES, Peres MA. Prevalence of malocclusions and their impact on the quality of life of 18-year-old young male adults of Florianopolis. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2005;3:217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Traebert ES, Peres MA. Do malocclusions affect the individual's oral health-related quality of life. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marques LS, Ramos-Jorge ML, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA. Malocclusion: esthetic impact and quality of life among Brazilian schoolchildren. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernabé E, Tsakos G, Messias de Oliveira C, Sheiham A. Impacts on daily performances attributed to malocclusions using the Condition-Specific Feature of the Oral Impacts on Daily Performances Index. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:241–247. doi: 10.2319/030307-111.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khadka A, Liu Y, Li J, et al. Changes in quality of life after orthognathic surgery: a comparison based on the involvement of the occlusion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burden DJ, Hunt O, Johnston CD, Stevenson M, O'Neill C, Hepper P. Psychological status of patients referred for orthognathic correction of skeletal II and III discrepancies. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:43–48. doi: 10.2319/022709-114.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adulyanon S, Sheiham A. Oral impacts on daily performances. In: Slade GD, editor. Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, Department Dental Ecology; 1997. pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slade GD. Assessing change in quality of life using the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2002;81:459–463. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster Page LA, Thomson WM, Jokovic A, Locker D. Validation of the child perceptions questionnaire (CPQ 11-14) J Dent Res. 2005;84:649–652. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agou S, Locker D, Streiner DL, Tompson B. Impact of self-esteem on the oral-health-related quality of life of children with malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Min-Ho Jung. Evaluation of the effects of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment on self-esteem in an adolescent population. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badran SA. The effect of malocclusion and self-perceived aesthetics on the self-esteem of a sample of Jordanian adolescents. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:638–644. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klages U, Claus N, Wehrbein H, Zentner A. Development of a questionnaire for assessment of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics in young adults. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28:103–111. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sardenberg F, Oliveira AC, Paiva SM, Auad SM, Vale MP. Validity and reliability of the Brazilian version of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics questionnaire. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:270–275. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H, Quan C, Guo C, Zhou C, Wang Y, Bao B. Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics questionnaire [published online ahead of print November 24, 2011] Eur J Orthod. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr136. doi:10.1093/ejo/cjr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paula DF, Jr, Silva ÉT, Campos AC, Nuñez MO, Leles CR. Effect of anterior teeth display during smiling on the self-perceived impacts of malocclusion in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:540–545. doi: 10.2319/051710-263.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernabé E, Sheiham A, de Oliveira CM. Condition-specific impacts on quality of life attributed to malocclusion by adolescents with normal occlusion and Class I, II and III malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:977–982. doi: 10.2319/091707-444.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernabé E, Sheiham A, Tsakos G, Messias de Oliveira C. The impact of orthodontic treatment on the quality of life in adolescents: a case-control study. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:515–520. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekuni D, Furuta M, Irie K, et al. Relationship between impacts attributed to malocclusion and psychological stress in young Japanese adults. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:558–563. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.British Standard Institute. British Standard Incisor Classification Glossary of Dental Terms BS 4492. London, UK: British Standard Institute; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aaronson NK, Acquadro C, Alonso J, et al. International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res. 1992;1:349–351. doi: 10.1007/BF00434949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Paula Júnior DF, Santos NC, da Silva ET, Nunes MF, Leles CR. Impact of dental esthetics on quality of life in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:1188–1193. doi: 10.2319/082608-452R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernabé E, de Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Condition-specific sociodental impacts attributed to different anterior occlusal traits in Brazilian adolescents. Eur J Oral Science. 2007;115:473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernabé E, Flores-Mir C. Influence of anterior occlusal characteristics on self-perceived dental appearance in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:831–836. doi: 10.2319/082506-348.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenny J, Cons NC, Kohout FJ, Frazier PJ. Test of a method to determine socially acceptable occlusal conditions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1980;8:424–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1980.tb01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]