Abstract

In Orthopedics, damage control is indicated in patients with pelvic and/or long bone fractures associated with hemodynamic instability. It is inappropriate to perform a complex definitive reduction and fixation surgery for severely injured trauma patients with hemodynamic instability. In these cases, it is recommended to perform minimally invasive procedures that temporarily stabilize the fractures and bleeding control. Closed or open fractures of the long bones such as femur, tibia, humerus, and pelvis can lead to hemodynamic instability and shock. Thus, orthopedic damage control becomes a priority. However, if the patient is hemodynamically stable, it is recommended to stabilize all fractures with an early permanent internal fixation. These patients will have a shorter hospital length of stay and a reduction in mechanical ventilation, blood components transfusions and complications. Therefore, the concept of orthopedic damage control should be individualized according to the hemodynamic status and the severity of the injuries. Open fractures, dislocations, and vascular injuries could lead to permanent sequelae and complications if a correct management and approach are not performed.

Keywords: Polytrauma, Damage control, Orthopedics, External fixation, Definitive early fixation

Resumen

En Ortopedia se indica control del daño en pacientes que presentan fracturas de pelvis y/o huesos largos asociado a condiciones generales inestables. Dada la severidad del trauma asociada a inestabilidad hemodinámica no es adecuado realizar una cirugía definitiva compleja de reducción y fijación de todas sus fracturas. En estos casos se recomienda realizar procedimientos poco invasivos que permitan estabilizar provisionalmente las fracturas, para; disminuir el dolor, controlar la hemorragia de las fracturas, obtener una alineación adecuada de los huesos fracturados y reducir las luxaciones. Estas medidas permiten controlar el daño del primer golpe para así disminuir las complicaciones. Las fracturas de los huesos largos fémur, tibia, húmero y pelvis cerradas o abiertas pueden llevar a una inestabilidad y estado de shock. Mientras que el paciente no tenga alteración hemodinámica, se recomienda estabilizar todas sus fracturas precozmente con una fijación interna que controle esta forma el daño y la necesidad de tiempo de hospitalización. Como resultado se disminuyen los días en cuidados intensivos, la ventilación mecánica, las transfusiones y las complicaciones. El concepto de control de daño para el manejo de las lesiones ortopédicas se debe individualizar de acuerdo a las condiciones generales de cada paciente y la gravedad de sus lesiones como: fracturas abiertas, luxaciones, luxación completa de la articulación sacroíliaca, luxofractura del talo, y lesiones vasculares, ya que estas lesiones requieren un manejo prioritario inicial generalmente definitivo en la mayoría de los pacientes con politraumatismo para evitar complicaciones serias futuras que pueden dejar secuelas definitivas al no recibir el tratamiento adecuado inicial.

Palabras clave: Politraumatismo, control del daño, ortopedia, fijación externa, fijación temprana definitiva

Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| In Orthopedics, damage control is indicated in patients with pelvic and/or long bone fractures associated with hemodynamic instability. It is not appropriate to perform a complex definitive reduction and fixation surgery for severely injured trauma patients with hemodynamic instability. In these cases, it is recommended to perform minimally invasive procedures which provide temporary stabilization of the fractures and bleeding control. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| Closed or open fractures of the long bones such as femur, tibia, humerus, and pelvis can lead to hemodynamic instability and shock, thus, orthopedic damage control becomes a priority. However, if the patient is hemodynamically stable it is recommended to stabilize all fractures with an early permanent internal fixation. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| Orthopedic damage control is based on early physiological stabilization and temporary maneuvers such as external fixators and damage control resuscitation. This strategy is indicated in hemodynamically unstable trauma patients with long bone fractures, unstable pelvic fractures and/or massive hemorrhage. |

Introduction

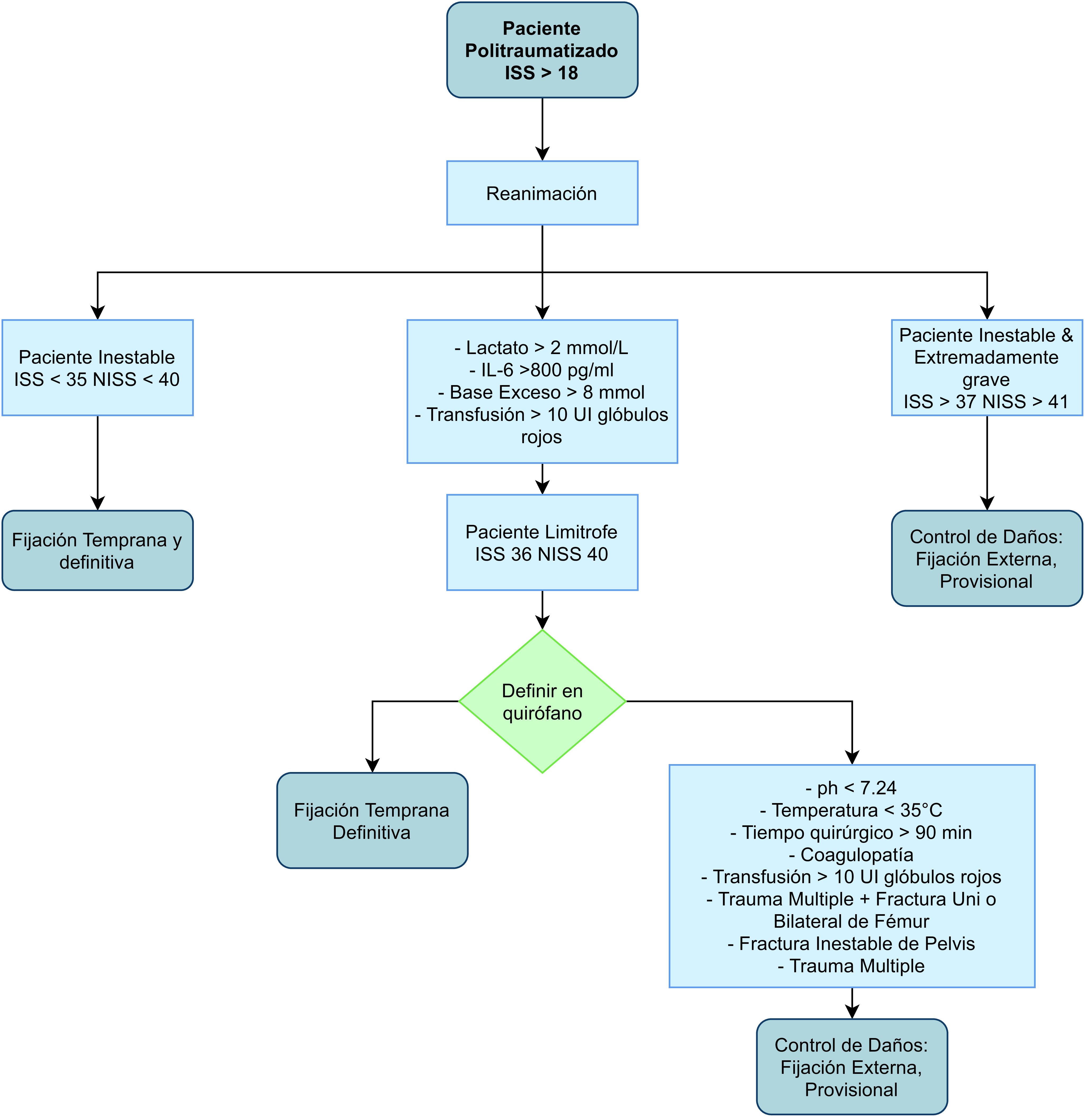

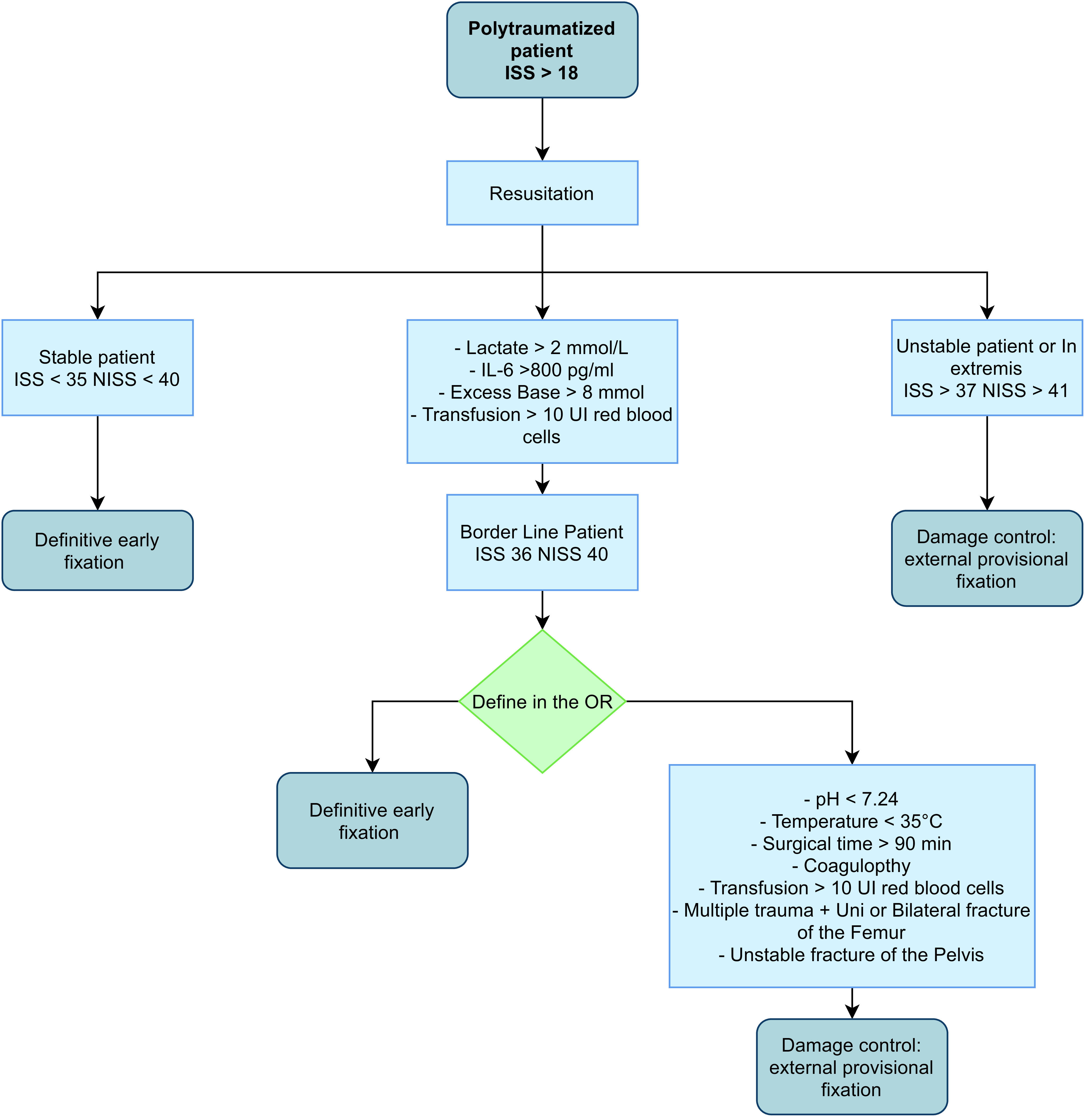

Damage control in Orthopedics and Traumatology is indicated in severely injured trauma patients with long bones and/or pelvis fractures. Definitive treatment of these orthopedic injuries is performed via open or closed reduction and stable internal fixation. However, early definitive fracture fixation is not recommended for patients with persistent hemodynamic instability despite resuscitation efforts 1 , 2 . In these cases, it is indicated to perform prompt and provisional fracture fixation under the principles of orthopedic damage control with temporary external fixators 3 - 5 . Then, a second surgery should be performed to place permanent osteosynthesis. Injury severity should be estimated according to the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and/or the New ISS (NISS) to decide whether the patient is a candidate for early definitive fixation or orthopedic damage control 6 - 8 . Early definitive stabilization is indicated in patients with an ISS less than 36 points or a NISS less than 40 points 9 , 10 .

On the contrary, patients with a higher score should undergo orthopedic damage control. After the index surgery, the patient should be transferred to the intensive care unit to continue metabolic resuscitation, and then definitive fixation of all fractures should be performed. This article aims to expose the principles of orthopedic damage control.

Epidemiology

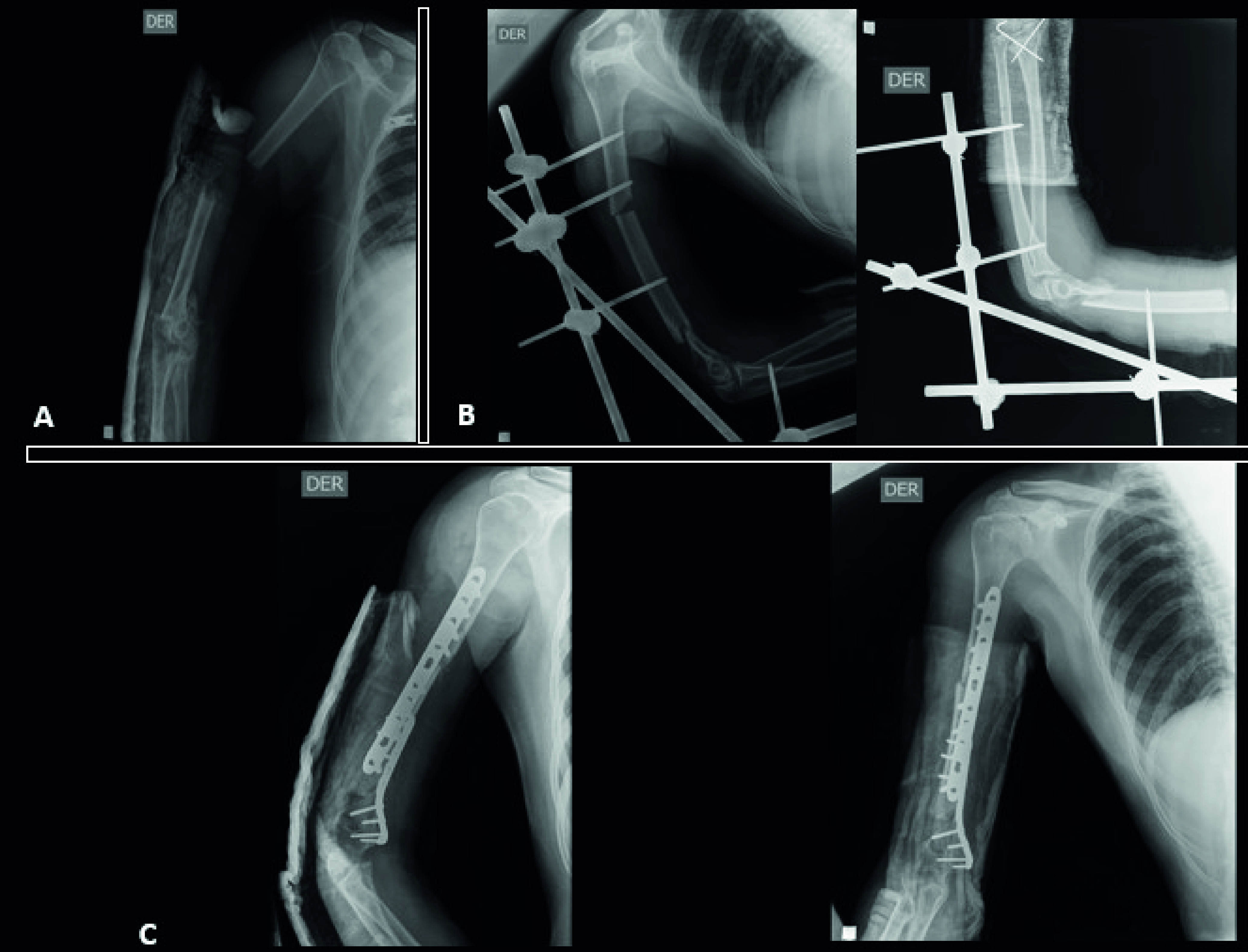

Polytrauma is one of the leading causes of death in patients younger than 40 years 11 , 12 . Worldwide, road traffic accidents are the main mechanism of trauma associated with polytrauma in patients aged 5 to 30 years 11 , 13 . Local studies had reported an incidence of 80-100 patients per year with polytrauma, of these 55% present long bones or pelvis fracture and 12% had indication for amputation due to severe lower extremity injury. The most frequent fractures were tibia diaphysis, femur diaphysis, and pelvis. Bilateral femur fractures were associated with a poor prognosis, increased mortality rate, and fat embolism syndrome 8 . These patients had an ISS higher than 18 points and required treatment in the Intensive Care Unit 10 . Orthopedic damage control was performed at index surgery in 31% of the patients and early definitive fixation in 61% (Figure 1). The mean intensive care unit length of stay was 8 days, and the mean hospital length of stay was 17 days. Sixty percent required mechanical ventilation with a mean duration of 5.6 days 10 , 13 . The overall complication rate was 44%. Patients with early definitive stabilization generally have lower ISS and NISS with less complications, morbidity and mortality rates 10 .

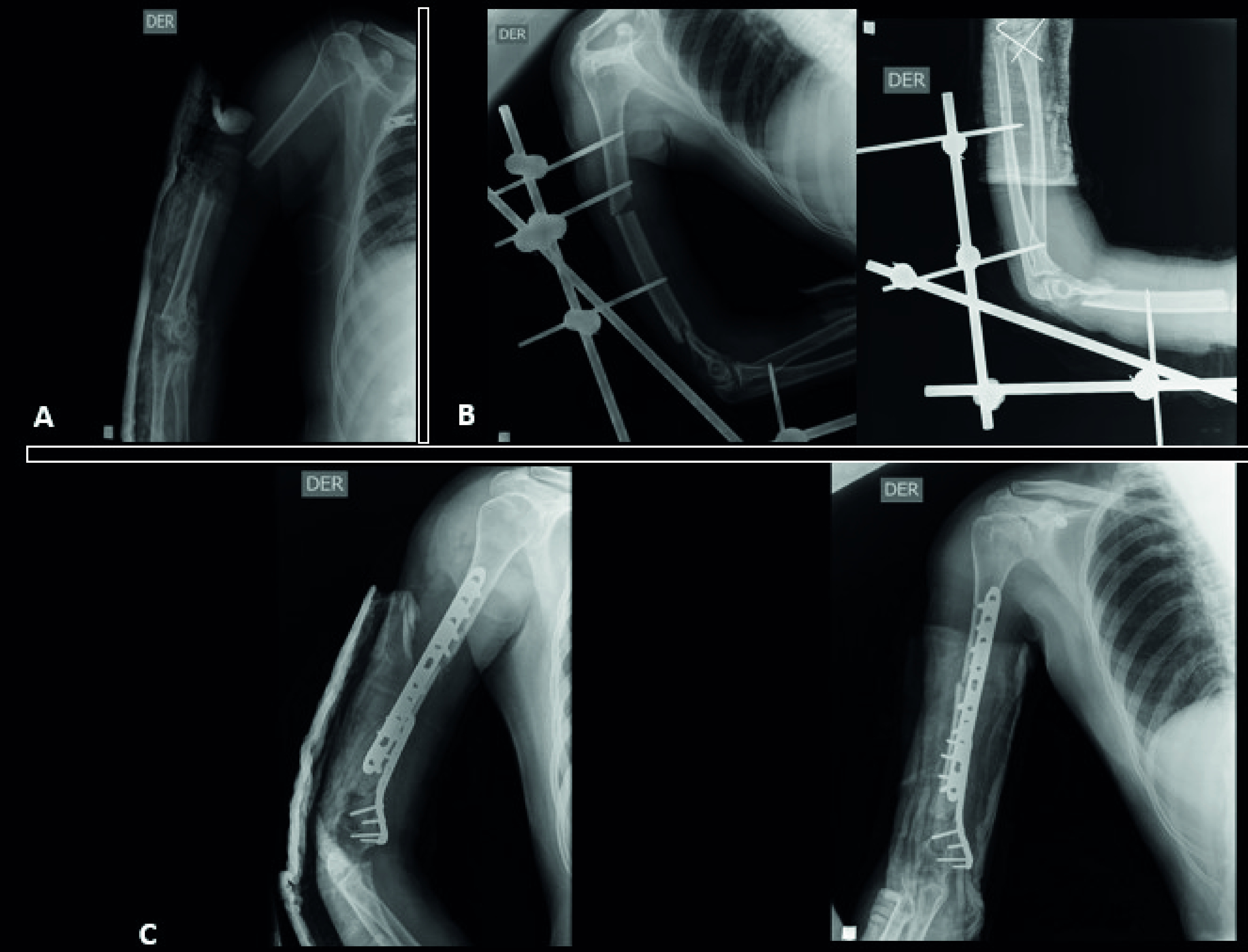

Figure 1. Polytrauma with humerus fracture. A.Admission X-ray of right humerus fractureB. X-ray of the humerus after damage control with external fixatorC.Definitive fixation after a second surgical time.

Pathophysiological considerations

Polytrauma is defined as a trauma that affects three or more systems and has an ISS greater than 18 14 . Polytrauma is caused by high-energy mechanisms that generate significant injuries. When high-energy trauma affects more than one system, an exaggerated inflammatory response occurs with the activation of cytokines, macrophages, leukocytes, and other inflammatory cells. Cell migration is activated by interleukin-8 (IL-8) and other components of the complement system such as C5a and C3a 15 , 17 . This organic response produces local (on the fracture site) and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS). Depending on the severity of the trauma and the individual response of the patient, the SIRS can last several days until the anti-inflammatory events and Systemic Anti-inflammatory Compensatory Response Syndrome (CARS) come into action 18 .

Both the immune response markers and the inflammatory reactants peak within the first 24 -72 hours of trauma 16 , 19 . This is the reason why the most critical hours are the first 72 hours. The markers are divided into three groups: a) acute phase reactants, b) mediator activity and c) cellular activity. The most important for orthopedic trauma are TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-10 (Table 1).

Table 1. Main markers of inflammation in the polytrauma patient 25 .

| Phase | Marker | Principal function | Peak |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase reactants | Protein-bound lipopolysaccharide (LPB) | Activation of macrophages to release IL-6 and IL-1 | 48 -72 hours |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | Low specificity in trauma since it is increased in the presence of infections, cancer, and autoimmune diseases | Levels up to 500 mg in 8 hours | |

| Procalcitonin (PCT) | Produced by stimulation of IL-6. Low specificity in trauma, indicates more presence of infection | 48-72 hours | |

| Mediator activity markers | Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNF- α) | It is one of the central regulators since it is required for leukocyte chemotaxis. If persist elevated, it is an indicator of a poor prognosis. | 24-48 hours |

| IL- 1 and IL- 8 | Its presence is essential in the initial phase for adequate inflammatory activation. If persist elevated, it is an indicator of a poor prognosis and mortality. | 24-48 hours | |

| IL-6 | The appearance of (LPB) occurs secondary. | 4 hours (indicates the severity of trauma 24 hours | |

| IL -10 | Powerful anti-inflammatory in response to increased TNF-α. In homeostasis with TNF-α improves prognosis. | > 72 hours | |

| Cell activity markers | Cytokine receptors | They are a good indicators of inflammatory response severity because of their specificity for TNF-α and interleukins. Specific for interleukin inhibit cell transduction. | > 72 hours |

| Elastase | Released by neutrophils. Its elevation is associated with increased mortality and multiple organ failure. | ||

| Human leukocyte antigen (HLA-DR) | It is the marker with the highest validity to correlate with morbidity and mortality |

Diagnosis

According to Berlin’s definition, a polytrauma patient presents injuries in three or more systems or in two or more different anatomical regions 14 . The hemodynamic status of the patient should be defined and the severity of trauma should be estimated. The most recommended score is the ISS proposed by Baker 6 . The ISS evaluates six systems: the head (including the cervical spine), face, thorax (including the thoracic spine), abdomen (including the lumbar spine), extremities (including the pelvis), and external skin injuries. This score is based on the Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS), which estimates a degree of severity per injured organ (Table 2).

Table 2. Abbreviated Trauma Index (AIS) 20 .

| Overall Abbreviated Trauma Index Score | Pelvic and Extremity Trauma Scoring |

|---|---|

| 1. Minor | 1. Contusion in the absence of fracture |

| 2. Moderate | 2. Short Bone Fracture |

| 3. Serious | 3. Multiple Short Bone Fracture or single long bone fracture |

| 4. Severe | 4. An open fracture, fractures in more than one long bone, or traumatic amputation |

| 5. Critical | 5. Unstable pelvic fracture or multiple open long bone fractures |

| 6. Maximal | 6. Impossible to survive |

Osler proposed a modification of the scores considering that some patients have several fractures in the extremities and pelvis and not so important injuries in other systems. Thus, the New Injury Severity Score (NISS) is an alternative score, in which one system can provide two scores if the injuries are more severe than those in other systems 7 , 8 . For example, a polytraumatized patient with a rib fracture (+2), closed fracture of the femur (+3), unstable pelvic fracture (+4), and mild trauma to the abdominal wall (+1). Considering the three injured systems, the thorax, abdomen, and extremities/pelvis, the ISS score (the sum of the squares of the three most compromised systems = 42+ 22+ 12) is 21 points. Otherwise, if we take the most compromised locations (thorax, femur, and pelvis) as the NISS scale suggests, the total is 29 points (42+ 32+ 22). Even though the score does not vary in other patients the score does not varythe score does not vary because no system has more than one injury in other patients, the ISS scale could minimize the severity of the trauma (See the example in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differences between NISS and ISS calculation in polytraumatized patients. Patients with polytrauma of the chest, abdomen, extremities, pelvis, and spine. Bilateral open femur fracture (5 points), unstable pelvic and radius fracture (4 points), chest trauma and thoracic spine fracture (4 points), and abdominal trauma with stable pneumoperitoneum (2 points). ISS = 52+ 42+ 22= 45 points. NISS = 52+ 42+ 42= 57 points.

Initial treatment will be defined according to the hemodynamical stability of the patient and the severity of trauma. According to the classification, some actions could be taken. For example, open fractures, vascular injuries, joint dislocations and/or femoral neck fractures should always be prioritized and early definitive stabilization or a temporal stabilization with external fixators under the concept of damage control could be performed.

Treatment

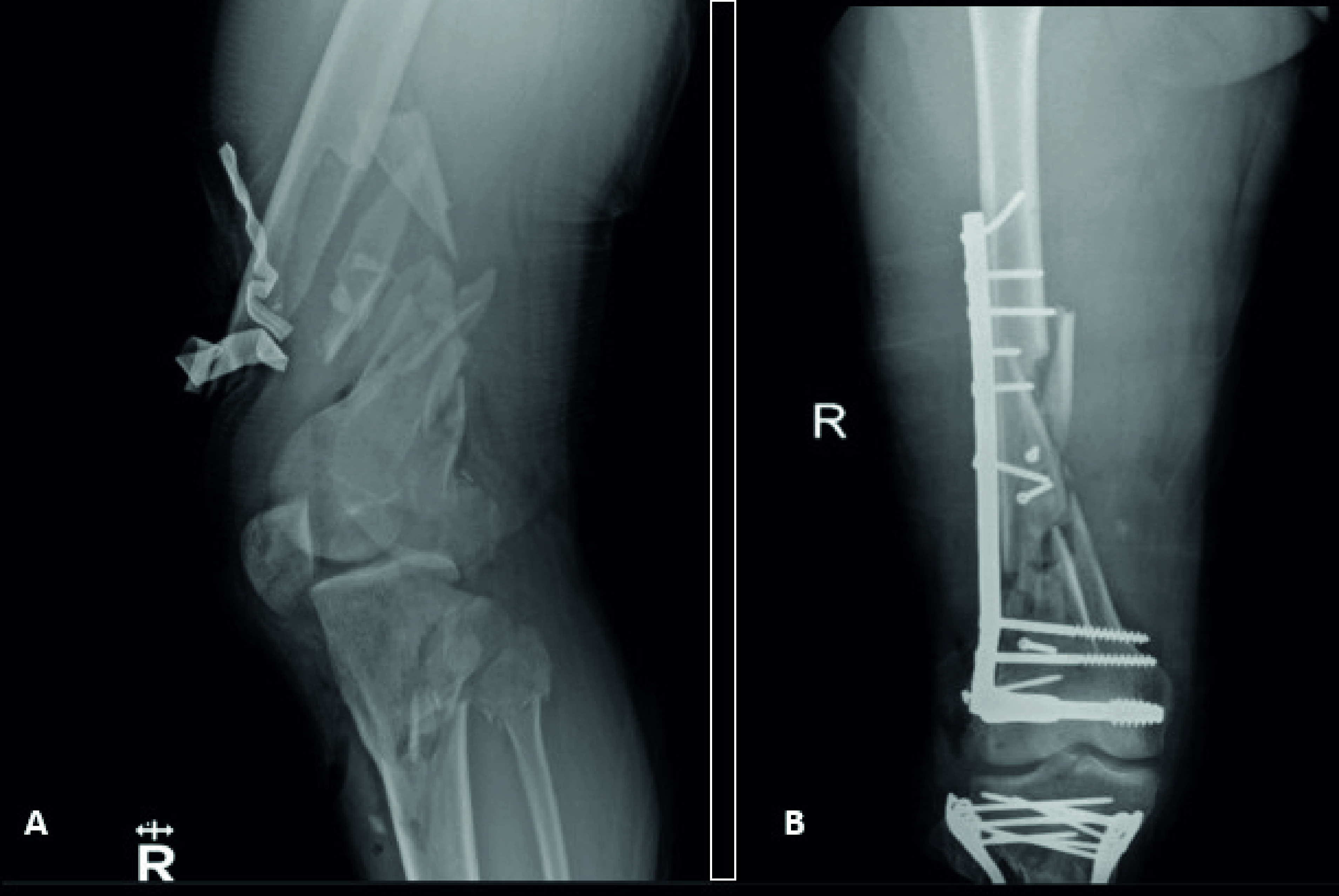

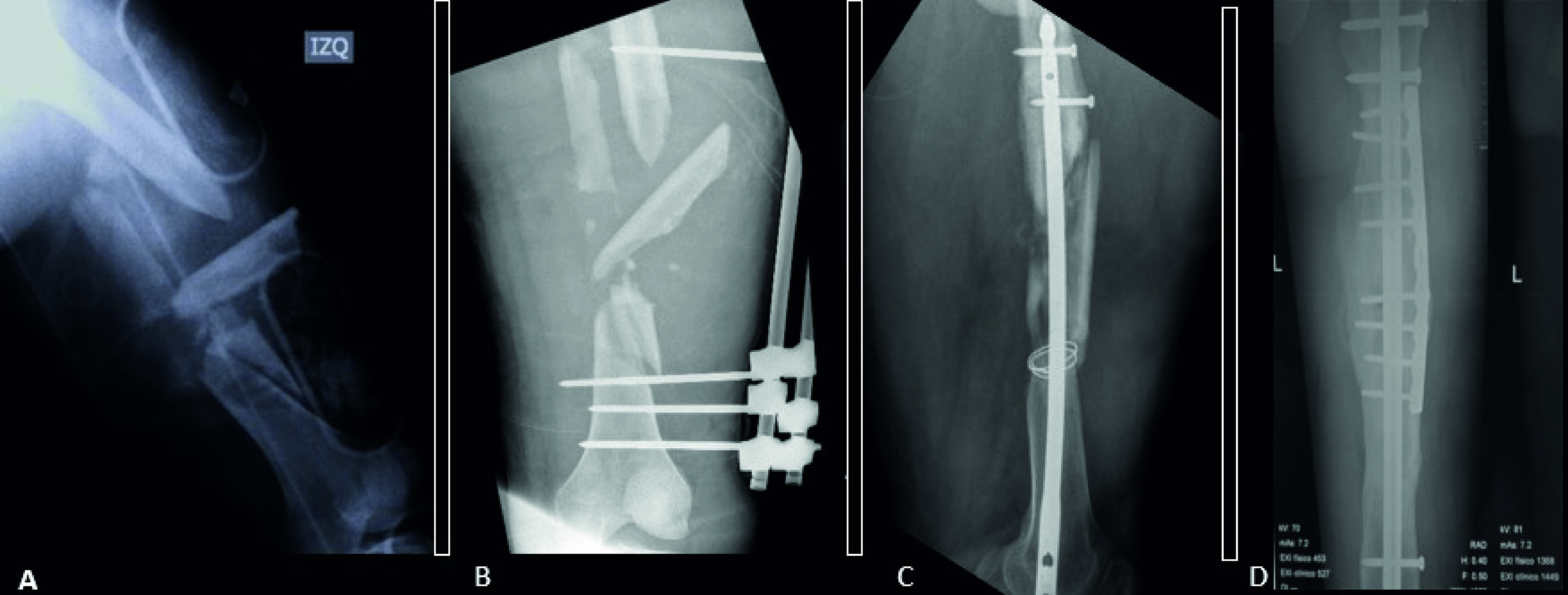

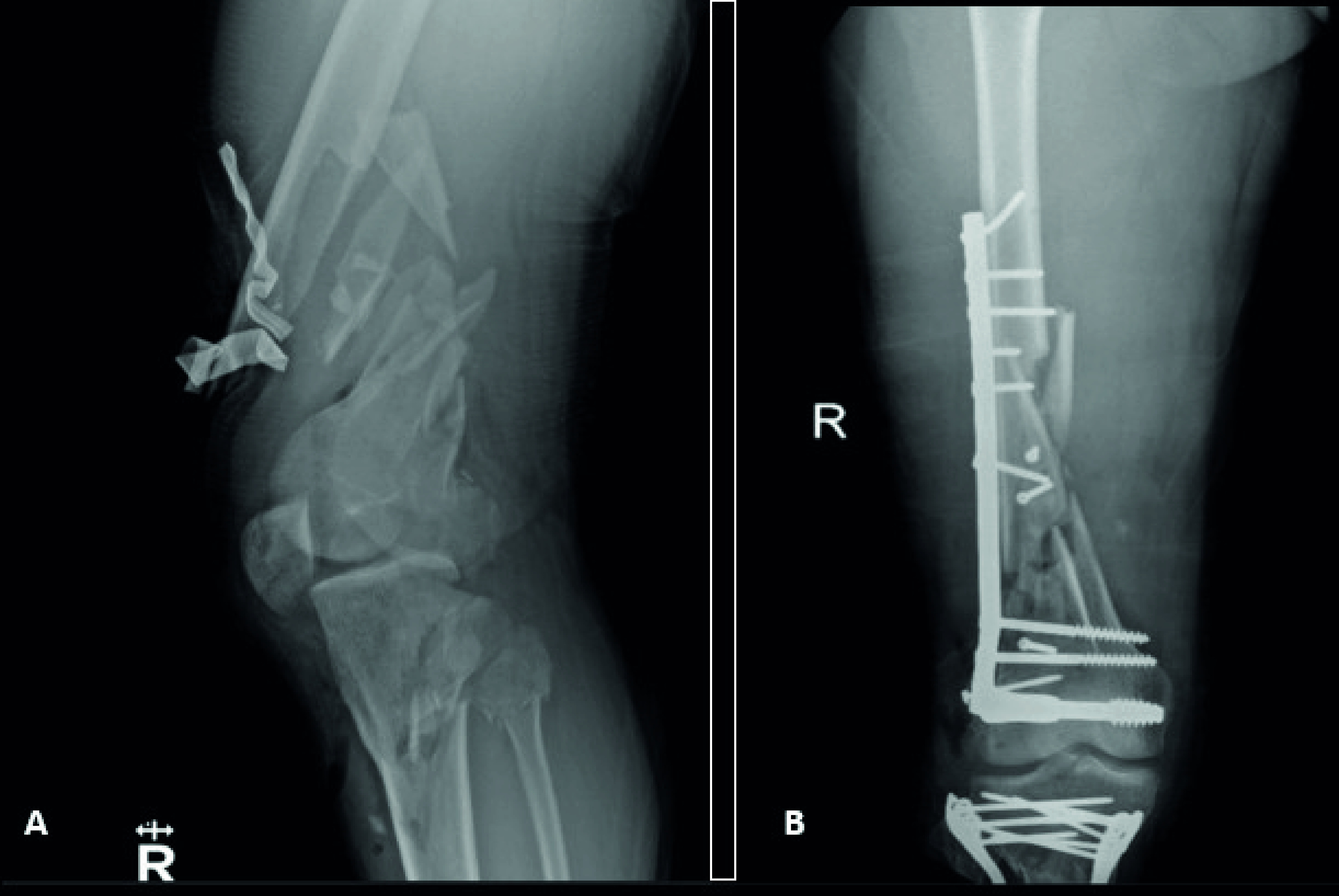

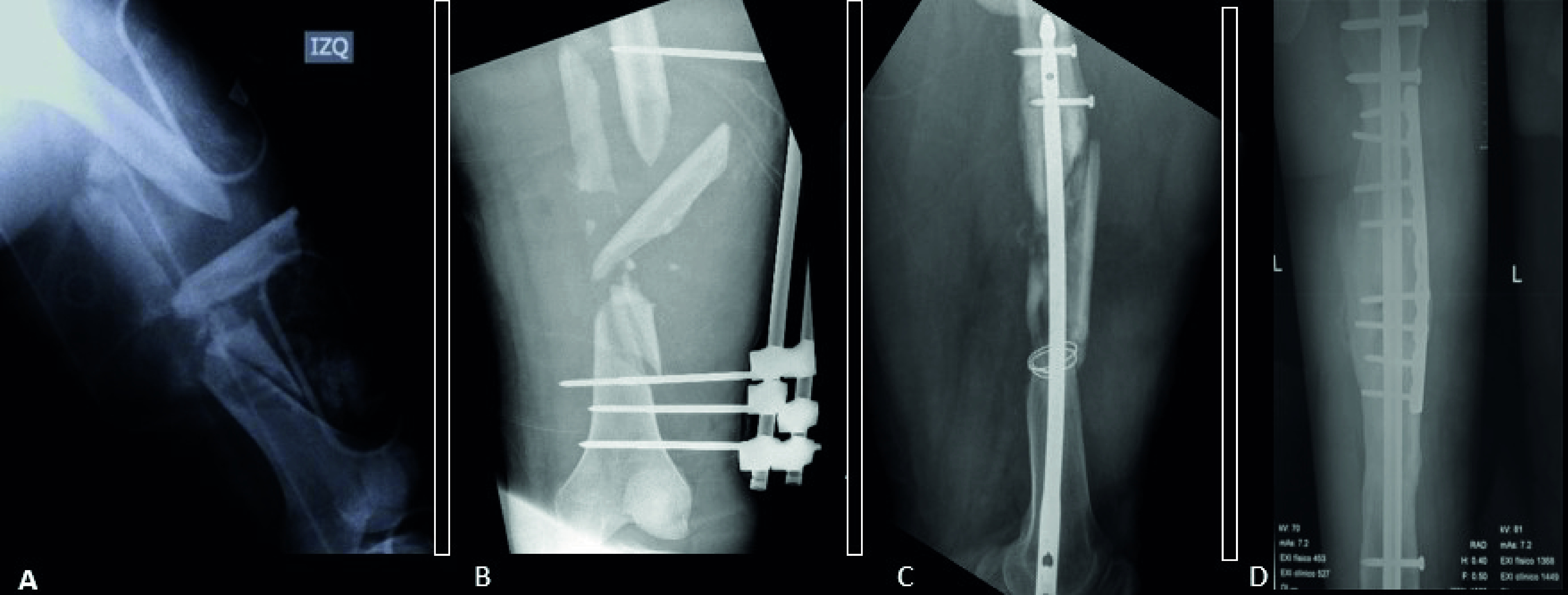

The definitive stabilization of long bone fractures in the first 24 hours positively impacts survival 1 , 21 - 23 . Hemodynamically stable patients should undergo definitive fixation of fractures during the first surgery (Figura 3). However, prolonged interventions (over 90 minutes) in hemodynamically unstable patients are associated with unfavorable outcomes. Furthermore, major surgery can trigger and increase immune response resulting in a clinical condition called “Second Trauma” 15 , 17 , 24 . Therefore, delayed definitive stabilization has been implemented in hemodynamically unstable patients to reduce the effect of the second trauma 25 , 26 . These patients should undergo damage control with a temporary fixation, followed by physiologic stabilization and a deferred definitive fixation in a second surgical time 5 to 10 days after damage control (Figura 4) 10 , 16 , 27 , 28 .

Figure 3. Orthopedic management of a hemodynamically stable patient with polytrauma. A 30-year-old male was admitted for a traffic accident as a motorcycle driver. ISS 30 NISS 32 upon admissionA.Admission X-ray femur shaft fracture + tibial plateau and fibula fractureB.First stage postsurgical result after definitive early stabilization of the fractures.

Figure 4. Orthopedic management of a hemodynamically unstable patient with polytrauma. A 30-year-old patient who was involved in a motorcycle accident, upon admission ISS 37 NISS 45 A. Admission radiograph of the left femur with open diaphyseal fracture B. After damage control radiography with external fixator C. Second surgical time 10 days later to admission with retrograde cephalic medullary nail D. 2 years after internal fixation in which adequate consolidation is observed.

But where are the borderline patients in this approach? Currently, the literature has not established whether borderline patients should undergo damage control or initial definitive fixation. The recommendation is to have the technical tools that allow to define if the patient is a candidate for damage control 22 , 29 . The proposed orthopedic approach and management is depicted in the algorithm shown in Figure 5 and Table 3).

Figure 5. Orthopedic Trauma Management Algorithm.

Table 3. Classification of the polytraumatized patient.

| Parameters | Stable | Limit | Unstable | In extremis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypovolemic state | Blood pressure (mmHg) | > 100 | 80-100 | 60-90 | <50-60 |

| Units of blood | 0-2 | 3-8 | 5-15 | > 15 | |

| Lactate level | Normal | 2.5 | > 2.5 | Severe acidosis | |

| Base deficit | Normal | No data | No data | > 6-8 | |

| ATLS | I | II-III | III-IV | IV | |

| Coagulation | Platelets | > 110,000 | 90,000-110,000 | 70,000-90,000 | <70,000 |

| Facto II, V (%) | > 1 | 70-80 | 50-70 | <50 | |

| Fibrinogen | Normal | 1.0 | <1 (abnormal) | Coagulopathy | |

| Temperature | Degree centigrade (° C) | > 34 | 33-35 | 30-32 | <30 |

| Soft tissue injury | Pulmonary function*** | 350-400 | 300 - 350 | 200-300 | <200 |

| Chest trauma (AIS) | I or II | > II | > II | > III | |

| Pelvic fracture classification | Type A fracture: Stable | Type B fractures: unstable | Type C fracture: Unstable | Type C fracture: Unstable | |

| Surgical strategy | Damage control | No | ± | Yes | Yes |

| Definitive surgery | Yes | ± | No | No |

Stable patients and some in a borderline state are generally able to perform damage control with definitive early stabilization of all their fractures

Conclusion

Orthopedic damage control is based on early physiological stabilization and temporary maneuvers such as external fixators and damage control resuscitation. This strategy is indicated in hemodynamically unstable trauma patients with long bone fractures, unstable pelvic fractures and/or massive hemorrhage.

References

- 1.Vallier HA, Super DM, Moore TA, Wilber JH. Do patients with multiple system injury benefit from early fixation of unstable axial fractures the effects of timing of surgery on initial hospital course. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:405–412. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182820eba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nahm NJ, Vallier HA. Timing of definitive treatment of femoral shaft fractures in patients with multiple injuries A systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1046–1063. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182701ded. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Alleyrand JCG.O'Toole RV The evolution of damage control orthopedics Current evidence and practical applications of early appropriate care. Orthop Clin North Am. 2013;44:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallier HA, Wang X, Moore TA, Wilber JH, Como JJ. Timing of orthopaedic surgery in multiple trauma patients Development of a protocol for early appropriate care. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:543–551. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31829efda1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts C, Pape C-H, Jones A, Malkani A, Rodriguez J, Giannoudis P. Damage control orthopaedics Evolving concepts in the tratment of patients who have sustained orthopaedic trauma. J Bone Jt Surg. 2005;87-A:434–449. doi: 10.1016/j.mpsur.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker S. O`Neill B The injury serverity score An update. J Trauma. 1976;16(11):882–882. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong TH, Krishnaswamy G, Nadkarni NV, Nguyen H V, Lim GH, Bautista DCT. Combining the new injury severity score with an anatomical polytrauma injury variable predicts mortality better than the new injury severity score and the injury severity score A retrospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0215-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng Q, Tang B, Xue C, Liu Y, Liu X, Lv Y. Comparison of the ability to predict mortality between the injury severity score and the new injury severity score A meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13080825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waydhas C, Nast-Kolb D, Trupka A, Settl R. Posstraumatic inflammatory response, secondary operations, and late multiple organ failure. J Trauma. 1996;40:624–631. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez R. A, Uribe JP, Escobar SS, Henao J, Rios JA, Martinez-Cano JP. Control de daño y estabilización temprana definitiva en el tratamiento del paciente politraumatizado. 2018;32(3):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.rccot.2017.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organizacion . The global burden of diseases: 2019 Update. Geneva: World Health Organizacion; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicola R. Early total care versus damage control current concepts in the orthopedic care of polytrauma patients. ISRN Orthop. 2013;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/329452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peden R, McGee K, Krug E, Peden MM, World Health Organization . Injuries and violence prevention department. injury : a leading cause of the global burden of disease 2000. World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pape HC, Lefering R, Butcher N, Peitzman A, Leenen L, Marzi I. The definition of polytrauma revisited An international consensus process and proposal of the new "Berlin definition." J Trauma Acute Care. Surg. 2014;77:780–786. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannoudis P V, Hildebrand F, Pape HC. Inflammatory serum markers in patients with multiple trauma Can they predict outcome? J Bone Jt Surg Ser B. 2004;86:313–323. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.15035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schell H, Duda GN, Peters A, Tsitsilonis S, Johnson KA, Schmidt-Bleek K. The haematoma and its role in bone healing. J Exp Orthop. 2017;4:5–5. doi: 10.1186/s40634-017-0079-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horst K, Eschbach D, Pfeifer R, Hübenthal S, Sassen M, Steinfeldt T, et al. Local Inflammation in Fracture Hematoma: Results from a Combined Trauma Model in Pigs. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:126060. doi: 10.1155/2015/126060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannoudis PV, Smith RM, Bellamy MC, Morrison JF, Dickson RA, Guillou PJ. Stimulation of the inflammatory system by reamed and unreamed nailing of femoral fractures An analysis of the second hit. J Bone Jt Surg Ser B. 1999;81:356–361. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B2.8988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury. 2011;42:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenspan L, McLellan BA, Greig H. Abbreviated Injury Scale and Injury Severity Score a scoring chart. J Trauma. 1985;25:60–64. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Copeland C, Mitchell K, Brumback R, Gens D, Burgess A. Mortality in patients with bilateral femoral fractures. J Orthop Res. 1998;12:315–319. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pape HC, Rixen D, Morley J, Husebye EE, Mueller M, Dumont C. Impact of the method of initial stabilization for femoral shaft fractures in patients with multiple injuries at risk for complications (borderline patients) Ann Surg. 2007;246:491–499. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181485750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nowotarski PJ, Turen CH, Brumback RJ, Scarboro JM. Conversion of external fixation to intramedullary nailing for fractures of the shaft of the femur in multiply injured patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefaivre KA, Starr AJ, Stahel PF, Elliott AC, Smith WR. Prediction of pulmonary morbidity and mortality in patients with femur fracture. J Trauma. 2010;69:1527–1536. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f8fa3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez R. A Control del daño en ortopedia y traumatología. Rev Colomb Ortop Traumatol. 2006;20(3):55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scalea TM, Boswell SA, Scott JD, Mitchell KA, Kramer ME, Pollak AN. External fixation as a bridge to intramedullary nailing for patients with multiple injuries and with femur fractures Damage control orthopedics. J Trauma. 2000;48(4):613–621. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200004000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giannoudis P V. Surgical priorities in damage control in polytrauma. J Bone Jt Surg Ser B. 2003;85:478–483. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B4.14217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostenuik P, Mirza FM. Fracture healing physiology and the quest for therapies for delayed healing and nonunion. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:213–223. doi: 10.1002/jor.23460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi RR, Overton TL, Haut ER, Lau B, Vallier HA, Rohs T. Optimal timing of femur fracture stabilization in polytrauma patients A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:787–795. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]