Abstract

We studied 11 cases of culture-proven Listeria-associated lymphadenitis reported to the French National Reference Center for Listeria from 1994 to 2019 and 8 additional published cases. Listeria-associated lymphadenitis is rare, but it is associated with a mortality as high as for invasive listeriosis, and it is frequently diagnosed with concomitant neoplasia.

Keywords: adenitis, cancer, Listeria monocytogenes

We studied 11 cases of Listeria-associated lymphadenitis reported to the French Reference Center for Listeria, and 8 published cases. Listeria-associated lymphadenitis is rare but associated with a mortality as high as for invasive listeriosis, and frequently diagnosed with concomitant neoplasia.

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) is responsible for listeriosis, a severe foodborne infection mostly reported in immunocompromised patients, where it mostly presents as septicemia and neurolisteriosis. It is also responsible for maternal-neonatal infection. Focal infections are rare, consecutive to hematogenous seeding or direct inoculation [1]. Among them, Lm-associated lymphadenitis have not been characterized. We undertook a national retrospective study of this presentation over the last 25 years and identified 11 cases and reviewed the 8 published cases.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Collection

French surveillance of human listeriosis relies on mandatory reporting since 1999 with strains submission to the French National Reference Center for Listeria [2]. Reporting exhaustiveness is 87% [3]. We retrospectively studied culture-proven Listeria-associated lymphadenitis cases reported from January 1994 to December 2019. All cases with mention of “lymphadenitis”, “lymph node infection”, or “abscess” were reviewed. A confirmed case was defined as a patient from whom Listeria was isolated by culture of a lymph node. Eleven cases were identified, their medical charts were reviewed, and bacterial isolates were sequenced.

Ethical Evaluation

Because of the observational nature of the study with all data collected as a part of French National Surveillance, this study did not require patients’ written consent nor formal Institutional Review Board approval, according to the French legislation.

Review of the Literature

We searched the PubMed database for reports between January 1966 and December 2019, using the terms “Listeria”, “listeriosis”, “lymphadenitis”, and “lymph node” without language restriction [4–10].

Listeria monocytogenes Characterization

Species identification was carried out with API-Listeria microgallery (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) before January 2017 and then matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry [11]. Genome sequencing was performed as previously described [12]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) serogrouping, multilocus sequence types (MLSTs), and core genome MLST profiles were deduced from genome assemblies using the BIGSdb-Lm platform (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/listeria) [12].

Histopathological Analyses

We studied 2 available case samples: 5-μm thick sections of paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were performed. Listeria was labeled by immunohistochemistry using a polyclonal rabbit antiserum (R12) that detects Lm serotype 1/2a (Listeria O I/II) or 4b and Listeria ivanovii (Listeria O V/VI antiserum Seiken kit; Denka Seiken Co., Tokyo, Japan), and a goat antirabbit antibody coupled to peroxidase (EnVision+; Dako), followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. Images were captured on AxioImager A2 microscope with AxioCam ICc 1 digital camera (Zeiss).

For immunofluorescence staining, paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized, and antigens were retrieved by citric acid buffer. Samples were stained with R12 antibody for Lm serotype I/IIa [1] or Listeria O V/VI for L ivanovii and a goat antirabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 546 (Invitrogen) together with Hoechst 33342. Images were captured on a LSM710 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

RESULTS

Clinical Cohort

Among 7643 human cases collected between 1994 and 2019 in France, 11 were Lm-associated lymphadenitis (0.14%). Eight more published cases were identified, including 6 with some clinical data available. The 19 cases are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Features of 19 Patients With Listeria monocytogenes-Associated Lymphadenitis

| Reference | Patient No. | Age at Diagnosis, Sex, Underlying Diseases | Clinical and Imaging Features | Blood Cultures | Species and MLST Clonal Complex |

Histopathology | Treatment, Surgery, Antibiotics | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms Duration Before Diagnosis | Localization | Size, Number | Signs of Absces s |

General and Associated Signs | ||||||||

| This study | 1 | 72-year-old man, Essential thrombocythemia, myelofibrosis, chronic neutropenia, unbalanced diabetes, prednisone 7.5 mg/day | 3 weeks | Right cervical and under the chin | Bulky, multiple (CT scan) | No | Pneumonia | Negative |

L monocytogenes

CC121 |

NP | Puncture, amoxicillin (26 days) + gentamicin (5 days) | Two recurrences treated with amoxicillin (3 then 4 weeks). Cure (4 months). Death (1 year). |

| This study | 2 | 63-year-old man, uncontrolled diabetes (glycated hemoglobin 17.4%), tobacco smoke, alcoholism | 1 month | Right cervical | Bulky (6.5 × 8 cm; CT scan), single | Inflammatory (C) and necrotic (CT scan) mass | Weight loss (12 kg) | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC4 |

NP | Puncture, amoxicillin + gentamicin | Cure. Death (4 years, hepatocellular carcinoma) |

| This study | 3 | 88-year-old woman, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases | 3 weeks | Right inguinal | Bulky, single (C) | No | Lower limb cellulitis | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC2 |

Infiltration with gynecological carcinomatous cells | Amoxicillin-clavulanate (10 days): persistence. Lymph node removal. Amoxicillin 6 g/d. | Discovery of a metastatic gynecological carcinoma. Death (2.5 months) |

| This study | 4 | 82-year-old woman, uncontrolled type II diabetes, obesity | 3 months | Left cervical | Bulky (5cm, C), single (US) | No (US) | No | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC9 |

NP | Surgical drainage. No antibiotic. | Death (1 day) |

| This study | 5 | 55-year-old woman, type II diabetes, tobacco smoking | NA | Left inguinal | Bulky, single (C) | No | NA | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC5 |

Nonnecrotic epithelioid granuloma | Lymph node removal. | Cure. Death (5 years, metastatic gallblader carcinoma) |

| This study | 6 | 60-year-old man, HBV and alcoholic cirrhosis, tobacco smoking, alcoholism | 1 month | Median cervical | Bulky, single (CT scan, US) | Fistulization | No | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC20 |

Nonnecrotic epithelioid granuloma | Surgical drainage. Amoxicillin (21 days) | Cure (2 months) |

| This study | 7 | 72-year-old woman, untreated and unbalanced type II diabetes | 3 weeks | Left submaxillar | Bulky (7 × 4 × 7 cm; CT scan), single | Yes (CT scan) | Asthenia | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC199 |

Necrotic epithelioid granuloma, pus | Lymph node removal. Pefloxacin (10 days) | Cure (6 months) |

| This study | 8 | 61-year-old man, carcinoma of the esophagus diagnosed 1 month earlier |

NA | Right supraclavicular | Bulky, multiple (CT scan) | No | Weight loss | NP |

L monocytogenes

CC21 |

NP | Puncture. Amoxicillin 8 g/day (15 days) | Cure (5 months). Metastatic carcinoma of the esophagus (right latero-esophageal and supraclavicular bundle of lymph node). |

| This study | 9 | 80-year-old woman, type II diabetes | NA | Inguinal | NA | NA | NA | NA |

L monocytogenes

CC7 |

NA | NA | Cure (17 years) |

| This study | 10 | 11-year-old boy | 6 days | Right iliac | Large (16 × 11 mm), multiple (US). | No | Fever, anorexia, abdominal pain |

NP |

Listeria ivanovii

CC883 |

Chronic lymphadenitis without sign of malignancy | Surgical lymph node removal. Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg per day (15 days) | Cure (1 month) |

| This study | 11 | 66-year-old man | 1.5 months | Right cervical | Large (3cm), multiple (CT scan) | No | Asthenia, weight loss, fever |

Negative |

L monocytogenes

CC20 |

NP | Puncture. Cotrimoxazole (3 weeks) | Cure (2 months). Discovery of a chronic lymphocytic leukemia. |

| Larsson S [13] | 12 | 81-year-old woman, type II diabetes | 3 weeks | Cervical | NA | Yes | No | NA | NA | NP | Surgical drainage. No antibiotic | Cure |

| Bojsen-Moller [7] | 13 | NA | NA | Cervical | Single | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Blanche et al [8] | 14 | 55-year-old woman, types II diabetes, HIV infection (CD4+ T lymphocyte count 242/mm3) | NA | Cervical | Multiple | No | Fever | Negative | NA | Nonnecrotic epithelioid granuloma, pus | Surgical drainage. Amoxicillin (6 weeks) | Cure |

| Ferrer et al [9] | 15 | 81-year-old man, diabetes mellitus | NA | Cervical | Single | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Goulet et al [14] | 16 | 56-year-old man, type II diabetes, alcoholism | NA | Cervical | NA | NA | NA | NP | NA | NP | Puncture | Cure |

| Goulet et al [14] | 17 | 60-year-old man | NA | Cervical | NA | NA | NA | NP | NA | NP | Puncture | Cure |

| Rosenthal et al [10] | 18 | 75-year-old man, type II diabetes, obesity, tobacco smoke, alcoholism | 1 month | Cervical | Bulky (4cm), multiple | Fistulization | No | NP | NA | Necrotic epithelioid granuloma, pus | Lymph node removal. Amoxicillin-clavulanate (4 weeks) | Death (4 week); autopsy: myocardial ischemia, metastatic carcinoma of the bladder, residual neck abscess |

| Betriu et al [5] | 19 | 52-year-old woman, uncontrolled type II diabetes | NA | Left cervical | Bulky (8 × 3 × 3; CT scan), single | Inflammatory mass (C), collection (CT scan, US) | Fever | Negative | NA | Epithelioid granuloma | Surgical drainage. Amoxicillin (1 month) + Gentamicin (3 days) | Stable (2 months) |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MLST, multilocus sequence type; NA, not applicable; NP, not practiced.

Epidemiological Features

Ten patients (10 of 18, 56%) were male. Median age was 65 years (interquartile range [IQR], 57–79). Four patients (4 of 18, 22%) were ≥80 years old. Sixteen patients (16 of 18, 89%) presented 1–3 immunosuppressive comorbidities, either pre-existing (n = 12) or revealed by listeriosis (n = 4): diabetes was reported in 12 of 18 (67%); alcoholism and neoplasia were each reported in 4 of 18 (22%); neoplasia was diagnosed shortly before (case 8), concomitantly (cases 3 and 11), or shortly after (case 18) the diagnosis of lymphadenitis (no patient had received chemotherapy at lymphadenitis onset); myelofibrosis with chronic neutropenia and human immunodeficiency virus infection were also reported (n = 1, each).

Clinical Features

Median time from first symptom to diagnosis was 4 weeks (IQR, 3–4 weeks; n = 10). Lymphadenitis was isolated (9 of 15, 60%) or multiple (6 of 15, 40%). All involved a single unilateral area: cervical (14 of 19, 74%), inguinal (3 of 19, 16%), supraclavicular or iliac (1 of 19, 5% each). Lesions were bulky in 12 of 15 (80%). Suppuration was evidenced clinically and/or by computed tomography or ultrasound imaging in 7 of 16 (44%). Five patients (5 of 13, 38%) reported fever. No neurological involvement was reported. One patient with inguinal lymphadenitis exhibited concomitant intertrigo and lower limb cellulitis, and another with cervical adenitis had concomitant upper lobe consolidation pneumonia that resolved, respectively, with amoxicillin/clavulanate and amoxicillin/gentamicin. Another patient with iliac lymphadenitis had confirmed Listeria-associated appendicitis.

Laboratory Characteristics and Microbiological Features

Median leucocyte count was 10 150/mm3 (IQR, 6250–10 525; n = 6), and median C-reactive protein level was 42 mg/L (IQR, 36–54; n = 5). Listeria was isolated from pus or tissue culture in 17 of 17 cases. In 1 patient (case 10, iliac lymphadenitis), samples also grew Streptococcus anginosus and anaerobic flora. Blood cultures, when performed, were all negative (4 of 4). Listeria monocytogenes was identified in 10 of 11 (91%) cases, and L ivanovii was identified in 1. Distribution of Lm clonal complexes was as follows: 2 isolates belonged to CC2 and CC4 hypervirulent clones, 2 belonged to hypovirulent clones CC9, and 121 others belonged to clones with intermediate virulence (Table 1).

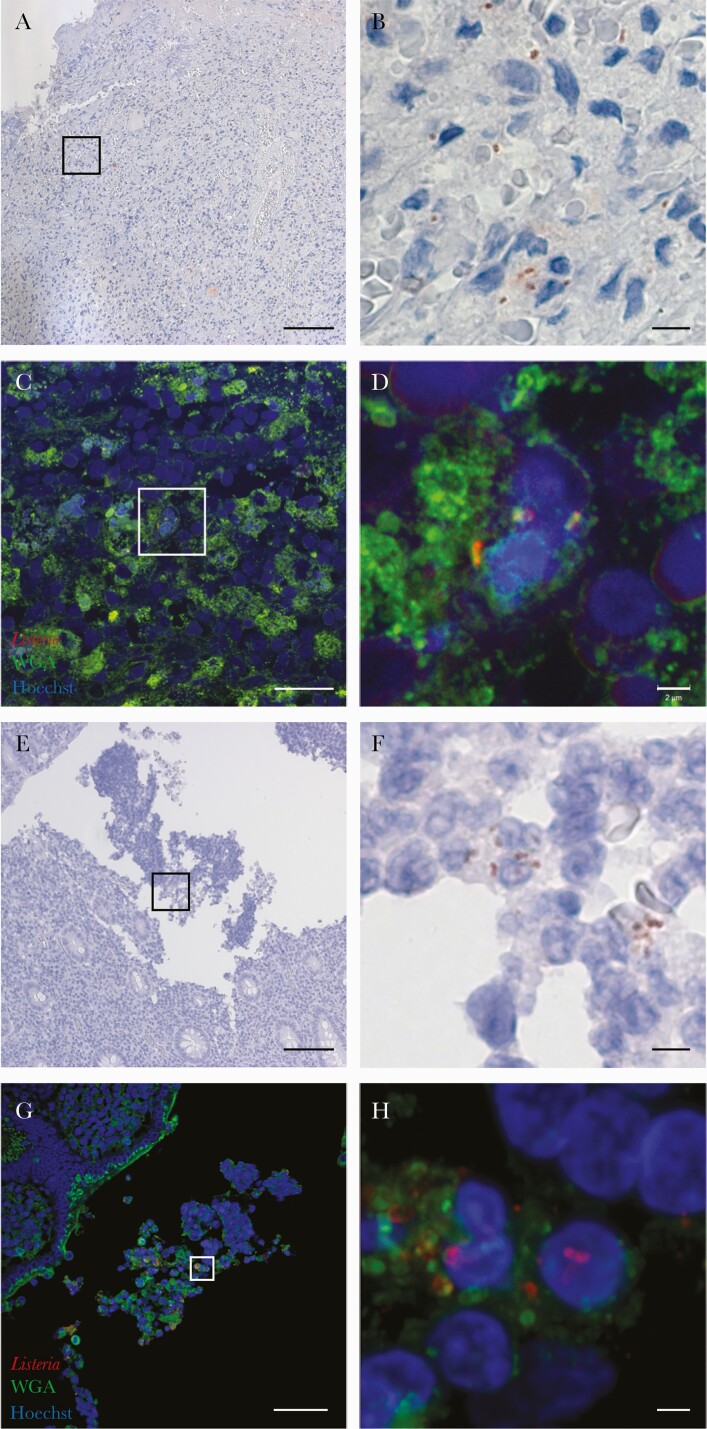

Histopathological Findings

Histopathological reports were available for 8 patients and showed epithelioid granuloma in 6 of 8 (75%, including 2 with necrosis), chronic lymphadenitis or metastatic gynecological carcinoma without epithelioid granuloma (1 of 8, 13% each). Listeria could be identified in samples of 2 cases (cases 6 and 10), by immunoperoxidase staining (Figure 1A, B, E and F) and immunofluorescence (Figure 1C, D, G and H). Bacteria were localized mostly in cells having a morphology evocative of monocytes/macrophages and also in polymorphonuclear cells (Figure 1B and F).

Figure 1.

Detection of Listeria monocytogenes (Lm), which appear in red, in adenitis tissue samples collected from 2 patients with immunoperoxidase staining (A, B, E, and F) and direct immunofluorescence with wheat germ agglutinin (in green) and Hoechst (in blue) staining (C, D, G, and H). The Lm are localized (1) within cells evocative of monocytes and macrophages, (2) but also in polymorphonuclear cells in close vicinity with the capsule of the abscessed lymph node in the section available for case 6 (A–D), and (3) within appendix lumen in the section available for case 10 (E–H). Scale bars: 100 µm (A and E), 20 µm (C), 50 µm (G), 5 µm (B and F), and 2 µm (D and H).

Treatment and Follow-up

Management relied on surgery in 16 of 16 cases (100%): puncture (6 of 16, 38%), surgical drainage (4 of 16, 25%), or excisional biopsy (6 of 16, 38%). Antibiotics were administered in 11 of 13 (85%) and relied on amoxicillin (n = 4), amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 2), amoxicillin and gentamicin (n = 3), cotrimoxazole or pefloxacin (n = 1, each), for a median of 21 days (IQR, 15–28; n = 10). Thirteen patients (13 of 17, 76%) recovered; 1 reported protracted recurrence requiring prolonged antibiotics (6%). Three patients (3 of 17, 18%) died within 3 months, immediately after surgical procedure (n = 1, no autopsy performed) or as a consequence of concomitant neoplasia (n = 2, including 1 patient for whom autopsy findings revealed myocardial ischemia and bladder carcinoma).

DISCUSSION

We studied the detailed clinical and microbiological features of Lm-associated lymphadenitis in a cohort of 19 patients, including 11 from the French cohort and the 8 previously published cases. Several conclusions can be drawn.

First, although rare, Lm-associated lymphadenitis is a genuine disease entity, whose mortality is as high as invasive listeriosis [15]. In line with this observation, most patients presented predisposing conditions associated with invasive listeriosis, namely, older age and immunosuppressive comorbidities, including diabetes, alcoholism, and ongoing neoplasia [15]. Listeria-associated lymphadenitis and cancer were diagnosed concomitantly in 4 patients, in the range reported in nonmaternal invasive listeriosis (22% versus 20%) [15]. None had received antitumoral chemotherapy at lymphadenitis onset, possibly reflecting tumor-associated immunosuppression. Indeed, studies in a BALB/c model of mammary carcinoma have shown that Lm survives and multiplies in the tumoral microenvironment while rapidly killed in healthy tissues [16]. This selective survival and growth is linked to the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells that produce interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-β that could help Lm escape the cellular immune response at the tumor site [16]. It indicates that patients with Lm-associated lymphadenitis should be evaluated for neoplasia, mainly in the affected lymph node or locoregionally.

Seeding from a locoregional portal of entry is a possibility, considering the negativity of blood cultures, the absence of neurolisteriosis, and the involvement of a single lymph node, even though one cannot exclude that it may also result from bacteremia. The predominant cervical involvement may follow translocation in the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) of the pharyngo-oral region. Listeria can indeed be detected in tonsils of wild animals [17, 18] and also in humans [19]. The case with appendicitis likely results from Listeria translocation across the MALT of the appendix (Peyer’s patches).

Management should include (1) drainage of suppurative lesions or excisional biopsy and (2) Listeria-targeting amoxicillin-based antimicrobial therapy, which is otherwise not recommended in suppurative lymphadenitis, where Staphylococcus aureus should be covered. Because the review of literature was not performed according to PRISMA guidelines, some cases may have been overlooked and the total number of published cases may be higher.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, Lm-associated lymphadenitis is rare but associated with a mortality as high as for invasive listeriosis. Patients with Lm-associated lymphadenitis should be evaluated for concomitant neoplasia.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Hardy (Experimental Neuropathology Unit, Institut Pasteur Paris) for section preparations. We thank Dr. Marie-Albane Bensussan (University Hospital, Amiens), Drs. Stéphane Bland and Helene Petitprez (Annecy-Genevois Hospital), Karine Aubry (University Hospital, Limoges), Dr. Burroni Barbara (Cochin University Hospital, Paris), Dr. Jean Puyhardy (HIA Legouest Hospital, Metz), and Dr. Barrans Alain (Bassin de Thau Hospital, Sete).

Financial support. This work was funded by Institut Pasteur, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM), and Santé Publique France.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Charlier C, Leclercq A, Cazenave B, et al. Listeria monocytogenes-associated joint and bone infections: a study of 43 consecutive cases. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:240–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goulet V, Jacquet C, Martin P, et al. Surveillance of human listeriosis in France, 2001-2003. Euro Surveill 2006; 11:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morgand M, Leclercq A, Maury MM, et al. Listeria monocytogenes-associated respiratory infections: a study of 38 consecutive cases. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24:1339.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goulet V, de Valk H, Pierre O, et al. Effect of prevention measures on incidence of human listeriosis, France, 1987-1997. Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7:983–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Betriu C, Pérez-Cecilia E, Saiz F, Torres R, Picazo JJ.. Cervical adenitis due to Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2006; 14:188–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nieman RE, Lorber B.. Listeriosis in adults: a changing pattern. Report of eight cases and review of the literature, 1968-1978. Rev Infect Dis 1980; 2:207–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bojsen-Moller J. Human listeriosis. Diagnostic, epidemiological and clinical studies. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol 1972; (Suppl 229):1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blanche P, Lebrun B, Paul G, Sicard D.. Lymph node listeriosis in a HIV infected patient. Presse Médicale Paris Fr 1983 1992; 21: 1129–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrer D, Gómez D, Diosdado N, Rafecas FJ.. Listeriosis in the adult: presentation of 14 cases. Enfermedades Infecc Microbiol Clínica 1989; 7: 424–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenthal R, Vogelbach P, Gasser M, Zimmerli W.. Cervical lymphadenitis--a rare case of focal listeriosis. Infection 2001; 29:170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thouvenot P, Vales G, Bracq-Dieye H, et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry-based identification of Listeria species in surveillance: a prospective study. J Microbiol Methods 2018; 144:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moura A, Criscuolo A, Pouseele H, et al. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Microbiol 2016; 2:16185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Larsson S, Cronberg S, Winblad S.. Clinical aspects on 64 cases of juvenile and adult listeriosis in Sweden. Acta Med Scand 1978; 204:503–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goulet V, Marchetti P.. Listeriosis in 225 non-pregnant patients in 1992: clinical aspects and outcome in relation to predisposing conditions. Scand J Infect Dis 1996; 28:367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Charlier C, Perrodea É, Leclercq A, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:510–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chandra D, Jahangir A, Quispe-Tintaya W, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells have a central role in attenuated Listeria monocytogenes-based immunotherapy against metastatic breast cancer in young and old mice. Br J Cancer 2013; 108:2281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quereda JJ, Leclercq A, Moura A, et al. Listeria valentina sp. nov., isolated from a water trough and the faeces of healthy sheep. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020; 70: 5868–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weindl L, Frank E, Ullrich U, et al. Listeria monocytogenes in different specimens from healthy red deer and wild boars. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2016; 13: 391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bakulov IA. Listeriosis of animals: problems and research. Acta Microbiol Hung 1989; 36:145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]