Abstract

Objectives:

Only few studies evaluated whether hurricane preparedness impacts health. The PREPARE study addresses this gap.

Methods:

We recruited participants who had pertinent pre-hurricane data from the San Juan Overweight Adults Longitudinal Study (SOALS: n=364) and 125 patients with diabetes from Federally Qualified Health Center (COSSMA) in Puerto Rico. Participants aged 42–75 years completed interviews 20–34 months after Hurricanes Irma and Maria. We evaluated associations between self-reported hurricane preparedness and health and other related associations using logistic regression controlling for age, location, education and interview date.

Results:

Only 41% of participants reported high pre-hurricane preparedness; 25% reported gaps (moderate/low availability) in information and 48% reported gaps in resources for hurricane preparedness. Participants reporting lower pre-hurricane preparedness had higher reported hurricane-related detrimental health impact (OR=1.96; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.95) and higher odds (OR=2.07; 95% CI: 0.92, 4.68) of developing new non-communicable disease (NCD) compared to others. Post-hurricane drinking water disruption for ≥ 3 months versus none or less (OR=2.76; 95% CI: 1.39, 5.47) and similarly diet changes due to cooking/refrigeration access (OR=1.96; 95% CI: 1.24, 3.07), and diet changes for ≥ 20 months due to finances/access to shops (OR=2.83; 95% CI: 1.85, 4.32) were also associated with detrimental health impact.

Conclusion:

Lower preparedness was associated with higher detrimental impact of the hurricanes on overall health, and marginally significant impact on NCD. Future preparedness efforts could especially target means of coping with disruption of water services and regular diet, as these were also associated with detrimental health impact.

1. Introduction

Rising global surface temperatures have given way to an increased intensity of natural disasters, including hurricanes, which could have detrimental effects on health and well-being.1 The Atlantic Ocean had its most active hurricane season on record in 2020, with 30 named tropical storms,2 ten of which underwent rapid intensification.3 Exposure to hurricanes and other disasters is a consistent predictor of individual adverse health outcomes, including worsening of chronic disease, infections,4–6 and mental health disorders.7–9 Reducing exposure to hurricane-related stressors at individual and community levels could potentially prevent associated adverse health outcomes.9

The track and intensity of hurricanes are reasonably estimated a day or more prior to their impact on land. This provides time for government and other entities to issue warnings and calls for actions, including evacuation and preparation for potential damage to homes, and disruption of power and water and food access. For example, residents of hurricane-prone areas, such as those in low lying areas, are often advised to prepare “disaster kits” and “grab bags” and identify areas within the home to avoid injury.10, 11 Importantly, hurricanes generally occur within the defined hurricane season, allowing people in hurricane prone areas to prepare well in advance to avoid adverse health outcomes.

Prior research indicates low levels of disaster preparedness, even in disaster-prone areas. For example, data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) showed that 78% of participants in United States (US) reported feeling prepared for a disaster in 2006, but only 45% were actually adequately prepared.12 A 2012 review suggested that only 30–40% of US residents had emergency supplies.13 Even in an area where people have previously experienced hurricane disasters, only 8% of participants had enough food, water, and medications to last three days or more.14 Several studies identified barriers preventing people from preparing adequately, including lack of time and resources for emergency supplies, as well as unclear messages on how to prepare.12–15

The majority of studies to date have helped identify gaps in preparedness in different populations, including high-risk groups like older adults11, 15–17 and residents of disaster prone areas.18, 19 However, many of these studies asked participants about their preparedness for a hypothetical future disaster. Hence, these studies do not assess how actual preparedness efforts influenced disaster impacts. Also, most studies did not evaluate individual components of preparedness (e.g. water, food), and only a few drew on qualitative or mixed methods data to understand gaps in disaster preparedness.

Puerto Rico (PR), a US territory since 1898, is an archipelago in a very hurricane-prone region in the Caribbean. Adults living in PR have a higher incidence of chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity compared to adults living in mainland US. Hurricane Irma passed close to Puerto Rico (PR) on September 6, 2017 with Category 5 winds, resulting in significant flooding, widespread power outages, and water supply disruptions.20, 21 Just 14 days later, Hurricane Maria (Category 4) made landfall in Puerto Rico, resulting in severe flooding, mudslides, and extensive damage to property, and infrastructure including extensive disruption of water service and damage to the power grid with disruption of power across the entire region.22

An official death toll of 64 attributed to Hurricane Maria by December 2017 was initially reported by the PR government. In 2018, a Harvard University study23 estimated 4,645 deaths, and a George Washington University study24 estimated 2,975 deaths, later accepted as the official death toll. Prior research elsewhere showed that hurricanes are associated with increased non-communicable disease (NCD) risk.25–28 One recent study in the US Virgin Islands29 found that older adults and people with chronic disease faced the most adverse health impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Limited access to water along with prolonged loss of power due to Hurricane Maria were suggested to have been major contributors to high morbidity and excess mortality in Puerto Rico.23, 24 However, preparedness and its association with health impacts has not been evaluated in this context. Several studies show that patients with diabetes have serious complications in unfavorable environments due to disrupted health services and limited resources30. Potential explanations include anxiety, overeating, interruption of medications and physical activity, disruption of water supply, and limited resources after natural disasters31–33. The publications estimating death tolls after Hurricane Maria23, 24 did not evaluate NCD, which may explain the increased mortality.

Understanding gaps in preparedness, especially among high-risk groups with pre-existing health conditions could inform improvements in hurricane preparedness to reduce the impact on morbidity and mortality. This manuscript focuses on evaluating preparedness and its role in mitigating the detrimental long-term impacts of hurricanes on health among high-risk Hispanic adults in Puerto Rico. The aims of this manuscript are: (1) to describe hurricane preparedness among Puerto Rican adults prior to Hurricanes Irma/Maria; (2) to identify gaps in hurricane preparedness; (3) to understand the relationship between hurricane preparedness and the impact of the hurricanes on health; and (4) to understand the associations between post-hurricane disruptions of power, water and food access on health.

2. Methods

The Preparedness to Reduce Exposures and diseases Post-hurricanes and Augment Resilience (PREPARE) study built on existing cohorts to enable a longitudinal study to evaluate the impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on health outcomes in Puerto Rico, and to evaluate hurricane preparedness and resilience in this context.

2.1. Study population

The goal was to enroll participants from across Puerto Rico with pertinent data prior to the hurricanes. Hence, we sampled from two different sources, and conducted additional evaluations after Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit Puerto Rico. We recruited the majority of participants from an existing cohort, San Juan Overweight Adults Longitudinal Study (SOALS). Since SOALS consisted of adults drawn primarily from San Juan and neighboring areas, and since the hurricanes impact varied by location, we stratified the sampling by location in SOALS. Diabetes incidence and management were of key interest in PREPARE. Since SOALS recruited participants without physician diagnosed diabetes, and we also wanted to capture more participants from remote areas of Puerto Rico, we recruited participants with confirmed diabetes from federally qualified health centers Corporation of Health Services and Advanced Medicine (Spanish acronym: COSSMA). COSSMA has been providing outpatient health clinics, education, prevention programs, and special services for people with chronic disease from the rural eastern central region of Puerto Rico, where the eye of Hurricane Maria made landfall.

The primary goal of SOALS was to evaluate the bidirectional association between periodontitis and pre-diabetes. SOALS recruited 1,206 overweight/obese Hispanic adults aged 40 to 65 years (one who was found to be 39 and one 67 were retained), without diabetes mellitus (DM) and major conditions including cardiovascular disease.34 Data were collected at baseline (2011–2013) and three-year follow-up (2014–2016) exams. From the 1,028 who completed the follow up visit, we excluded 22 people for missing data, 125 with DM detected from study assessments at the baseline visit, three deceased, and one who had not consented for future studies. Eight refused to be contacted, leaving 869 eligible participants from three locations: 377 from the capital city (San Juan), 281 from the rest of the San Juan Metropolitan area (Metro area), and 211 from municipalities of Puerto Rico outside of San Juan Metropolitan Area (Other). We aimed to recruit 125 participants from each of these locations to get a more representative sample across Puerto Rico.

Inclusion criteria for COSSMA were: 1) having been a COSSMA patient in 2017 prior to Hurricane Maria; 2) having a diabetes diagnosis at a COSSMA visit prior to the hurricanes; 3) having attended at least one COSSMA medical appointment no earlier than one year before Hurricanes Irma and Maria and another visit within the year after; and 4) having data in their electronic health records (EHR) on HbA1c, height, and weight measurements before and after the hurricanes. COSSMA provided services to 2,306 individuals with DM prior to Hurricane Maria in 2017. After excluding patients with other missing information, we identified 416 potential participants with a similar age distribution to that of SOALS participants and with HbA1c assessments dated three months prior to Hurricane Irma (since HbA1c measures reflect the last three months). We recruited by priority levels based on post-hurricane HbA1c assessment dates in 2018 closer to 1 year after the hurricanes, until we reached our target of 125 participants with roughly equal having controlled and uncontrolled DM.

2.2. Procedures

An interview guide was developed with input from experts. All interviewers had at least completed high school. Training consisted of explaining and discussing each item and direct data entry in the REDCap platform, providing tips and effective techniques to gather data through interviews, and conducting mock interviews. Experienced study investigators trained the 16 interviewers, and conducted regular oversight to ensure that data collection procedures were performed correctly, and provided feedback as needed. The trained interviewers conducted recruitment and data collection between May 2019 and July 2020, 20–34 months after the hurricanes. They mailed an initial invitation to eligible SOALS participants followed by calls, and called COSSMA patients to inform them about the study. They scheduled eligible and willing participants for in-person visits. After completing written informed consent and confirmation of eligibility, they conducted computer-aided interviews on the REDCap platform. Interviews were conducted in person at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus for SOALS participants, and at a convenient COSSMA healthcare facility (Cidra and Las Piedras) for COSSMA patients.

Puerto Rico experienced a series of earthquakes in January 2020, and the government mandated COVID-19 pandemic lockdown started on March 15, 2020, which impacted the study. Before the lockdown, we had completed 54 COSSMA visits and 364 SOALS visits. We conducted the 71 pending COSSMA interviews with verbal consent by telephone during the pandemic. We decided not to complete the pending SOALS procedures, as we could not conduct in-person assessments needed for other aims, and we were only short of our target by 11 participants.

2.3. Measures

Questionnaires assessed impacts of the hurricanes, health conditions, and preparedness. In order to identify possible gaps in preparedness, participants were asked to rate the degree to which they felt they had the information and/or resources for adequate individual hurricane preparedness, and to report specific gaps. Since Hurricane Maria was later and caused much more damage than Irma, and we felt that it might be difficult for participants to distinguish Irma and Maria in their responses given how close they were in time, most questions focused on what happened after Maria.

Appendix 1 lists the key questions assessed in PREPARE that were used in this analysis (questions were administered in Spanish, but the English versions are provided here). Pertinent data including sociodemographic and medical data were abstracted from EHR for COSSMA participants. We assessed development of any major new NCD since the SOALS follow-up visit (2014–2020). COSSMA data was abstracted from the EHR, where we had actual dates to identify participants who developed NCD following the hurricanes.

Content analysis of the qualitative data obtained from the interviews was performed by three of the authors. For each question, a line-by-line analysis of the transcripts was conducted to determine common and recurring themes and patterns. We used an iterative process to refine the themes and codes identified. Discrepancies in coding were discussed, disagreements were resolved via mutual consensus, and criteria for each theme were revised as needed. After consensus of the themes and codes between all researchers, we computed counts and descriptive statistics by common themes and cohort for eligible participants.

2.4. Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were generated overall and by cohort (SOALS or COSSMA). Descriptive statistics include sociodemographic variables, disruption of essential services, components of preparedness and gaps in preparedness, and impact of the hurricanes. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between reported levels of preparedness and reported impact of the hurricanes on the participants’ health on development of new NCD. Analyses were conducted separately in each cohort and then pooled to achieve better control of confounding. Multivariable analyses were adjusted for age, education level, and for location in SOALS. Since the timing (before earthquakes, after pandemic) and different data collection methods (in-person or by telephone) could have affected the integrity of the sample and the quality of the responses obtained, we also controlled for the date of interviews (before or after the events). Participants were excluded from the analysis for which they had missing data on any of the variables. Statistical significance level was set to 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata 16.1. Similar analyses were conducted for additional exposures related to hurricane preparedness and impact (water, power loss and diet changes). Key analyses were repeated evaluating reported impact of the hurricanes on the participant’s family’s health as the outcome.

Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 59.8 years (SD=7.1), 75% were female, 94% were of Puerto Rican descent, and 49% were mixed/unspecified race. Over half the participants (58%) reported a household income below $20,000, and 61% reported having more than high school diploma post-secondary education degrees. SOALS participants (all free of diabetes) were younger and had substantially higher income and education than COSSMA participants (patients with diabetes). Around one-third of participants reported that the hurricanes impacted their health (43% of COSSMA and 32% of SOALS participants), and 36% reported that the hurricanes impacted the health of their family. The majority of participants (71%) reported that hurricanes impacted their finances (75% SOALS and 59% COSSMA).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of PREPARE participants: Mean ± SD or n (%)

| Overall | SOALS | COSSMA | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Sample Size (N) | 489 | 364 | 125 |

|

| |||

| Mean age ± SD | 59.8 ± 7.1 | 58.7 ± 6.8 | 62.9 ± 7.1 |

|

| |||

| Female | 368 (75.3) | 280 (76.9) | 88 (70.4) |

|

| |||

| Mixed/unspecified race | 241 (49.3) | 187 (51.4) | 54 (43.2) |

|

| |||

| > High School Diploma Education | 298 (60.9) | 269 (73.9) | 29 (23.2) |

|

| |||

| Household Income < $20,000 | 281 (57.5) | 175 (48.1) | 106 (84.8) |

|

| |||

| Preparedness before Maria | |||

| Low | 124 (25.4) | 98 (26.9) | 26 (20.8) |

| Moderate | 164 (33.5) | 112 (30.8) | 52 (41.6) |

| High | 201 (41.1) | 154 (42.3) | 47 (37.6) |

|

| |||

| Health impact of hurricanes (self)1 | 170 (34.8) | 116 (31.9) | 54 (43.2) |

|

| |||

| Health impact of hurricanes (family)1 | 178 (36.4) | 129 (35.4) | 49 (39.2) |

|

| |||

| Financial impact of the Hurricanes | 348 (71.2) | 274 (75.3) | 74 (59.2) |

|

| |||

| Duration of Power Loss | |||

| < 1 month | 18 (3.7) | 16 (4.5) | 2 (1.6) |

| 1 – 3 months | 204 (42.2) | 177 (49.3) | 27 (21.6) |

| > 3 months | 262 (54.1) | 166 (46.2) | 96 (76.8) |

|

| |||

| Disruption of the principal source of drinking water2 | |||

| % with disruption | 260 (53.2) | 181 (49.7) | 79 (63.2) |

|

| |||

| Duration of drinking water disruption3 | |||

| 1 day to < 1 month | 119 (47.8) | 88 (51.2) | 31 (40.3) |

| 1 – 3 months | 92 (36.0) | 65 (37.8) | 27 (35.1) |

| > 3 months | 38 (15.3) | 19 (11.1) | 19 (24.7) |

|

| |||

| Stored water lasted for3 | |||

| < 1 month | 155 (62.5) | 110 (63.6) | 45 (60.0) |

| 1 – 3 months | 81 (32.7) | 60 (34.7) | 21 (28.0) |

| > 3 months | 12 (4.8) | 3 (1.7) | 9 (12.0) |

|

| |||

| Drinking water disruption compared to how long the stored water lasted | |||

| Same | 20 (8.3) | 15 (8.9) | 5 (6.9) |

| Shorter time | 93 (38.6) | 68 (40.5) | 25 (34.3) |

| Water disruption for longer time | 128 (53.1) | 85 (50.6) | 43 (58.9) |

|

| |||

| Duration stored food lasted | |||

| < 1 month | 259 (55.0) | 220 (62.3) | 39 (33.1) |

| 1 – 3 months | 188 (39.9) | 121 (34.3) | 67 (56.8) |

| > 3 months | 24 (5.1) | 12 (3.4) | 12 (10.2) |

|

| |||

| Diet changes due to power loss4 | |||

| < 1 month | 86 (21.6) | 85 (23.6) | 1 (2.7) |

| 1 – 3 months | 186 (46.7) | 172 (47.7) | 14 (37.8) |

| > 3 months | 126 (31.7) | 104 (28.8) | 22 (59.5) |

|

| |||

| Diet changes up to interview date5 | 138 (28.2) | 101 (27.8) | 37 (29.6) |

|

| |||

| Experiences of hurricanes Irma and Maria served greatly6 to prepare better for future events | 411 (84.1) | 316 (86.8) | 95 (76.0) |

Abbreviations: SOALS = San Juan Overweight Adults Longitudinal Study; COSSMA = Corporation of Health Services and Advanced Medicine; SD = Standard Deviation.

What was the impact of the hurricanes on personal health? On family members’ health?

Did you have a post-María disruption of your usual source of drinking water?

Only reported by those who had a disruption in the principal source of drinking water.

How long did you have to change your eating habits due to a lack of refrigeration or cooking means?

As of today, has the impact of the hurricanes on access to shops or impact on finances resulted in a long-term change in your daily diet?

High degree or very high degree.

All participants lost power (average 19.2 weeks, SD=12.2); 96% reported being without power for one month or longer and 54% for longer than 3 months. Among COSSMA participants, 77% reported losing power for over 3 months (average 27.8 weeks, SD=13.5), compared to 46% of SOALS participants (average 16.2 weeks, SD=10.2). Overall, 73% lost water service (average 8.5 weeks, SD=9.6, median 4.3 weeks) (data not in table). A total of 53% lost access to their primary source of drinking water and 15% of these participants had drinking water disrupted for over three months. Participants whose drinking water was disrupted, stored water for five weeks on average (SD=7.2), and 63% of them did not store water or stored water estimated to last them less than one month. Over half of the participants (53%) did not store enough water to compensate for the duration of water service disruption. Before the hurricanes, 52% of the SOALS participants consumed bottled water as their main source, and after the hurricanes, 75% consumed bottled water as their main source (not shown in tables); these data were not collected for COSSMA. Most participants who lost water access resorted to consuming bottled water (89%) and 18% resorted to oases. Oases, supplied by the government Emergency Management Offices, consisted of places where people could fill up containers for water and included cistern trucks and fixed portable tanks35, 36. There were over 100 established points across the 78 municipalities. Many participants reported concerns regarding drinking water including quality (51%), taste (28%), and color (32%). Stored food lasted participants an average of 5.2 weeks SD=9.0 (median 3 weeks). Of the 398 participants who responded to the question on diet changes due to lack of refrigeration or cooking means after the hurricanes, 78.4% (312 of the 398 participants) had to make changes for one month or longer. Over a quarter (28%) of participants reported long-term changes to their diets due to challenges in access to shops and/or financial impact from the hurricanes.

3.2. Perceived gaps in preparedness

Only 41% of participants (42% SOALS vs. 38% COSSMA) reported being highly prepared for Hurricane Maria (Table 1). Overall, 84% of participants (87% SOALS and 76% COSSMA) reported that their experiences with the hurricanes prepared them greatly for future disasters (as indicated by “high degree” or “very high degree” responses to Q10 in Appendix 1 “How well did your experience with hurricanes Irma and Maria prepare you for future events?”). Overall, 75% (366/488) reported that they were highly informed about individual hurricane preparedness at the time of interview including 80% (292/364) of SOALS participants and 60% (74/124) of COSSMA participants (Table 2). Only 52% of all participants (255/488) reported having enough resources to be highly prepared including 56% (204/364) of SOALS participants and 41% (51/124) of COSSMA participants.

Table 2.

Gaps in resources and information reported by PREPARE participants and specific responses as coded from open-ended questions.

| Overall n (%) |

SOALS n (%) |

COSSMA n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Number of responders to availability questions below | 488 | 364 | 124 |

|

| |||

| Reported availability of information for hurricane preparedness 1 | |||

| Low (not at all / very small degree / small degree) | 25 (5.1) | 12 (3.3) | 13 (10.5) |

| Moderate (moderate degree) | 97 (19.9) | 60 (16.5) | 37 (29.8) |

| High (very great degree) | 366 (75.0) | 292 (80.2) | 74 (59.7) |

|

| |||

| Gaps in information 2, 3 | |||

| Number who reported low to moderate availability of information and specific gaps in information | 69 (56.6) | 50 (69.4) | 19 (38.0) |

| General information about hurricanes | 25 (36.2) | 14 (28.0) | 11 (57.9) |

| Food security and storage options | 14 (20.3) | 13 (26.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Emergency management4 | 21 (30.4) | 18 (32.0) | 3 (15.8) |

| Water (storage and oasis centers) | 8 (11.6) | 8 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Alternate energy sources | 7 (10.1) | 6 (12.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Home protection | 8 (11.6) | 7 (14.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Emergency backpack | 4 (5.8) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (10.5) |

| Alternate communication methods | 2 (2.9) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Other | 10 (14.5) | 7 (14.0) | 3 (15.8) |

|

| |||

| None/nothing 5 | 47 | 19 | 28 |

|

| |||

| All 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

|

| |||

| I don’t know 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

|

| |||

| Reported availability of resources for hurricane preparedness 6 | |||

| Low (not at all / very small degree / small degree) | 98 (20.1) | 75 (20.6) | 23 (18.6) |

| Moderate (moderate degree) | 135 (27.7) | 85 (23.4) | 50 (40.3) |

| High (very great degree) | 255 (52.3) | 204 (56.0) | 51 (41.1) |

|

| |||

| Gaps in resources 7, 8 | |||

| Number who reported low to moderate availability of resources and specific gaps in resources | 189 (81.1) | 150 (93.8) | 39 (53.4) |

| Economic | 85 (45.0) | 73 (48.7) | 12 (30.8) |

| Alternative energy and powered gadgets | 63 (33.3) | 53 (35.3) | 10 (25.6) |

| Home protection/improvements | 41 (21.7) | 33 (22.0) | 8 (20.5) |

| Water storage | 32 (16.9) | 24 (16.0) | 8 (20.5) |

| Food storage and cooking options | 24 (12.7) | 22 (14.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Information | 12 (6.3) | 7 (4.7) | 5 (12.8) |

| Medicine/medical care | 7 (3.7) | 5 (3.3) | 2 (5.1) |

| Other | 19 (10.1) | 13 (8.7) | 6 (15.4) |

|

| |||

| None/nothing 5 | 41 | 9 | 32 |

|

| |||

| I don’t know 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Abbreviations: SOALS = San Juan Overweight Adults Longitudinal Study; COSSMA = Corporation of Health Services and Advanced Medicine.

“Do you feel you have the necessary information to prepare adequately for hurricane preparedness?”

“What are the gaps in information that you have yet to learn about?” (Multiple responses were allowed)

The open-ended question (Q13 in the appendix) was asked only to people who responded not at all, to a very small degree, small degree or moderate degree to the question (Q12 in the appendix) do you feel you have the necessary information to prepare adequately for hurricanes?

Emergency management includes management after the hurricane has struck. For example, emergency plans, safest areas/places, refuge centers, government services, and community post-disaster relief support.)

Not included in the denominator for the specific gaps.

“Do you feel you have the resources you need for adequate hurricane preparedness?”

”What are the gaps in resources that you need?” (Multiple responses were allowed)

Among 122 (25%) participants who reported moderate to low / no availability of information for hurricane preparedness (72 from SOALS and 50 from COSSMA), responses to the open-ended question to identify specific gaps in information for adequate hurricane preparedness are summarized in Table 2. Fifty-three participants responded to the open-ended question with do not know, none/nothing or all, but did not identify any specific gaps. Among the 69 participants who reported specific gaps, 25 (36%) including 28% (14/50) in SOALS and 58% (11/19) in COSSMA reported gaps related to general information about hurricanes, 30% (21/69) including 32% (18/50) in SOALS and 16% (3/19) in COSSMA reported emergency management strategies as the most frequently reported gaps. The latter included contingency plans (e.g., emergency plans for people with specific health needs or functional diversity, condominiums, neighborhoods), safe areas, shelters, and other aids. Other key gaps reported were food security and storage methods including 20% (14/69) overall, 26% (13/50) in SOALS and 5% (1/19) in COSSMA; and water storage and available oasis centers including 12% (8/69) overall, 16% (8/50) in SOALS and 0% in COSSMA. The least frequently reported information gaps among both cohorts included alternative energy sources, home protection, and gaps related to emergency backpack (e.g., information on how to prepare the emergency backpack, what to include and in what quantity, and where to store the backpack).

Among 189 (47.8%) participants who reported moderate to low / no availability of resources for hurricane preparedness (150 from SOALS and 39 from COSSMA), responses to the open-ended question to identify gaps in resources for adequate hurricane preparedness are summarized in Table 2. Forty-four participants responded to the open-ended question with do not know, or none/nothing, but did not identify any specific gaps. The order of frequency was similar in both cohorts for economic resources (45%: 85/189), alternative energy sources (33%: 63/189), home protection and improvements (22%: 41/189), and water storage (17%: 32/189). Gaps in economic resources were reported by 49% (73/150) of SOALS participants compared to 31% (12/39) of COSSMA participants, whereas a need for alternative energy and powered gadgets was reported by 26% (10/39) of COSSMA participants compared to 35% (53/150) of SOALS participants.

3.3. Associations between preparedness and hurricane-related health impact

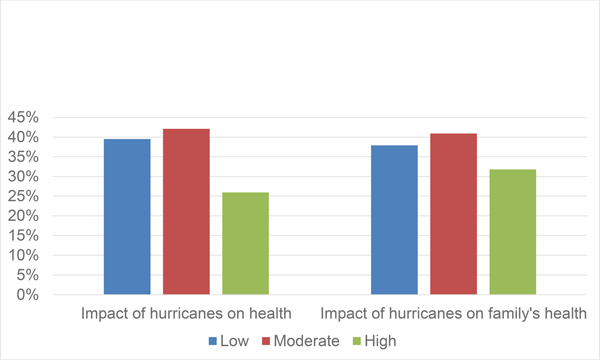

Figure 1 shows the health impact of hurricanes on participants and their families by preparedness levels. Among people with high preparedness, 26% reported an impact on their own health, compared to 40% of those with low preparedness. Among people with high preparedness, 32% reported an impact on their family’s health, whereas among people with low preparedness, 38% reported an impact on their family’s health.

Figure 1.

PREPARE participants: Impact of hurricanes Irma and Maria on participants’ and family’s health by pre-hurricane preparedness level

Table 3 shows results from multivariable analyses, pooling across both cohorts. All analyses controlled for age (60 years old or younger vs older than 60 years old), cohort (SOALS vs. COSSMA), location (only in SOALS), education (high school diploma or less vs. more than high school diploma), and date of interview (before the events vs. after the earthquakes vs. after COVID-19 pandemic). Participants who reported low to moderate levels of preparedness had 1.96 times the odds (95% CI: 1.31, 2.95) of experiencing an adverse health outcome compared to participants who reported a high level of preparedness prior to Hurricane Maria; the association was similar in SOALS (OR=1.95; 95% CI: 1.21, 3.14) and COSSMA (OR=2.05; 95% CI: 0.92, 4.58) (data not shown in tables). When we additionally adjusted for pre-hurricane family income in SOALS (data not available in COSSMA) as a measure of financial ability to adequately prepare for the disaster prior to the hurricanes, it did not change the estimates. Preparedness was not significantly associated with family health (OR=1.34; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.98).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression evaluating associations between preparedness and related factors, and self-reported hurricane related health impact among PREPARE participants

| OR crude | 95% CI | OR adjusted* | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Preparedness | |||||

| High | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Low or moderate | Pooled | 1.98 | 1.34, 2.95 | 1.96 | 1.31,2.95 |

|

Drinking water loss | |||||

| None to ≤ 3 months | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| > 3 months | Pooled | 2.74 | 1.40, 5.38 | 2.76 | 1.39, 5.47 |

|

Power loss | |||||

| 3 months or less | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| > 3 months | Pooled | 1.22 | 0.84, 1.78 | 1.17 | 0.79,1.74 |

|

| |||||

| Drinking water and power loss | |||||

| 3 months or less | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| > 3 months | Pooled | 2.74 | 1.34, 5.62 | 2.82 | 1.36, 5.87 |

|

| |||||

| Long term diet changes due to access to shops or financial impact | |||||

| No | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | Pooled | 2.94 | 1.96, 4.42 | 2.83 | 1.85, 4.32 |

|

| |||||

| Diet changes due to lack of refrigeration or cooking means | |||||

| 3 months or less | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| > 3 months | Pooled | 2.21 | 1.43, 3.42 | 1.96 | 1.24, 3.07 |

|

| |||||

| Duration of drinking water loss vs how long stored water lasted | |||||

| Same or stored water lasted for longer than what they lost | Reference | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Loss of water longer than stored water lasted | Pooled | 1.35 | 0.81, 2.26 | 1.43 | 0.84, 2.44 |

Abbreviations: SOALS = San Juan Overweight Adults Longitudinal Study; COSSMA = Corporation of Health Services and Advanced Medicine; OR crude = odds ratio crude, OR adj.=adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI = confidence interval at 95%. Odds Ratio adjusted model controlled for age (≤60 years old/ >60 years old), cohort (SOALS/COSSMA), location in SOALS, education (high school diploma or less/ more than high school diploma) and date of interview (before the events/ after the earthquakes/ after COVID-19).

Among participants who reported low to moderate levels of preparedness, 69% developed a new NCD, compared with 57% among those who reported a high preparedness. Participants who reported low to moderate levels of preparedness had 2.07 higher odds (95% CI: 0.92, 4.68) of developing a new NCD compared to participants who reported a high level of preparedness, after controlling for age, location, education, and date of interview. Participants who had any major NCD prior to the hurricanes (except for diabetes in COSSMA) were excluded from this analysis.

Associations between power, water, and diet changes and health impact of hurricanes

Multivariable analyses pooling both cohorts showed that participants who reported drinking water disruption for over 3 months had 2.76 (95% CI: 1.39, 5.47) times odds of experiencing a health impact compared to participants who reported shorter duration or no disruption. This association was null for family’s health as the outcome. We also compared participants who had longer interruptions in drinking water than their water in storage lasted, with those whose water in storage lasted longer than or similar to the period of interruption of service; there was a weak and non-significant association (OR= 1.43; 95% CI: 0.84, 2.44). Duration of power loss (over three months compared to shorter duration) was not associated with health impact (OR=1.17; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.74). Participants who had lost both water and power for longer than three months (compared to other participants) had higher health impact (pooled OR=2.82; 95% CI: 1.36, 5.87). Participants who made diet changes due to lack of refrigeration or cooking means for ≥ 3 months had twice the odds of reporting a health impact than participants with none or less than three months diet changes (OR=1.96; 95% CI: 1.24, 3.07); the odds ratio was 1.51 (95% CI: 0.96, 2.37) for family’s health. Participants who had longer-term diet changes (up to the time of study interviews) due to lack of access to stores or financial impact had 2.83 (95% CI: 1.85, 4.32) times the odds of experiencing a health impact, compared to those who did not; the association was also significant (OR= 2.12; 95% CI: 1.39, 3.23) for family’s health.

Discussion

Among PREPARE participants, 41% (SOALS 42% and COSSMA 38%) reported being highly prepared before Hurricanes Irma and Maria, 33.5% were moderately prepared, and 25.4% reported their preparedness as low. In comparison, 2006 BRFSS data assessing disasters preparedness from five US states (Arizona, Connecticut, Montana, Nevada, and Tennessee) showed that 22.2% reported feeling well prepared, 55.3% feeling somewhat well prepared, and 22.5% reported being not prepared at all.12 PREPARE participants were older, majority had overweight/obesity, 25% had diabetes, and they were reporting prior preparedness after exposure to two major hurricanes, compared to BRFSS with a more representative sample from five US states, reporting general preparedness for different potential disasters.

Although preparedness was higher than BRFSS, it was still markedly low, considering that Puerto Rico has a long history of hurricanes. However, a Category 5 Hurricane was extremely rare in Puerto Rico and people were not prepared for the severe long-term impact resulting from Irma and Maria. The low rate of preparedness among our participants is likely due in part to a large percent of participants having gaps in resources. Among participants with low to moderate availability of resources, almost half had gaps in economic resources, followed by alternative energy and powered gadgets, and home protection/improvements. Prior research suggests that families may be more likely to buy one-time purchase supplies, such as phones and flashlights, compared to supplies like food and water.10

Higher self-reported hurricane preparedness was associated with lower self-reported hurricane-related impact on health. Since the primary aim of this manuscript was to evaluate the overall health impact of the hurricanes, we focused on the health impact reported by participants, which may include injury, infectious disease, development/exacerbation of NCD, and/or mental health impact. We also observed a similar association between overall preparedness and development of NCD, corroborating our findings on reported health impact. SOALS participants self-reported their medically diagnosed NCD for the period spanning the hurricanes. The associations were similar in COSSMA where we extracted medical diagnoses from EHR and had the exact dates to distinguish post-hurricane NCDs. The association was independent of age, location, education, date of interview as well as pre-hurricane income.

No association was seen between duration of power loss and health impact. Although power loss may have likely impacted health directly (e.g., for people who needed powered medical devices) or indirectly, everyone lost power so there was no comparison group without power loss. However, our results do suggest an indirect impact of power loss as it affected many people’s diet due to lack of access to refrigeration and cooking means, and the diet changes were detrimentally associated with health.

Although food stored in preparation for the hurricane lasted an average of 5.2 weeks, and 45% of participants stored food to last a month or longer, 78% of participants reported making diet changes for one month or more due to lack of means to refrigerate or cook. Over one-fourth of the participants made longer-term diet changes due to food accessibility or financial impact. The associations between duration the stored food lasted, and diet changes were not significant, suggesting that other aspects, such as alternative cooking means and receiving help from government or other sources, may have mitigated the impact. Detrimental dietary changes (resulting from poor food preparedness and access) could exacerbate chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes37. Given the gaps in information reported regarding food security and storage options, more guidance is needed (e.g., on nutritious food that does not need refrigeration, proper storage methods for different food items, and managing food in the fridge after power loss). Considering that Puerto Rico relies considerably on importing food, post-disaster food accessibility may also be highly contingent on importing adequate food supplies and having the means to preserve perishable items and cook. People also need access and resources prior to hurricanes, so that affordable and nutritious shelf-stable food can be stored to last for several weeks or even months after power loss to reduce food insecurity after disasters.

The findings suggest that COSSMA participants, who had lower levels of socioeconomic status, were older and more likely to live in rural locations, experienced longer periods of power loss, and were more likely to experience economic impacts of the hurricanes, relative to their counterparts in SOALS. Given the rural setting of COSSMA clinics and most of their patients’ homes in the southeast region of Puerto Rico where the eye of Hurricane Maria made landfall, COSSMA participants may have likely had a much bigger impact of the hurricane and been more dependent on the mobilization of community organizations and government. Our data in fact shows that a higher percent of COSSMA participants (19%) received three months or more of government help compared to 9% of SOALS participants. Also, among those who had a disruption in their source drinking water, COSSMA participants were much more likely to have used government oasis compared to SOALS participants. These factors may have played a considerable role in mitigating water and food accessibility problems and thus reducing the health impact of the hurricanes among COSSMA participants. These results are consistent with research showing post-disaster hardships among low socioeconomic samples in the aftermath of other major disasters38, 39. They also align with Conservation of Resources theory40, which suggests that those already lacking social and economic resources are vulnerable to further resource loss in the event of external stressors.

A majority of the respondents expressed that their experiences with Hurricanes Irma and Maria served to highly prepare them for future disasters. However, most participants reported that post-disaster financial impacts would likely impact their ability to prepare adequately in the future. Economic resources are a necessity for hurricane preparedness, but almost half of the participants felt that they did not have sufficient economic resources to be highly prepared for future hurricanes. Hurricane Maria and its aftermath caused an estimated $68 billion in damages.21, 22 The economy in Puerto Rico was already facing financial challenges prior to the hurricanes limiting one’s ability to improve self-reported hurricane preparedness. The population has plummeted over the years due to high unemployment rates and rising poverty levels as well as the lasting impact of Hurricane Maria. Two years after, many homes had still not been repaired from damages caused by the hurricanes. Of the 72% of participants who reported having received help from organizations, only 55% were satisfied with the help received. However, very little assistance is provided for preparedness prior to hurricanes. Directing more funds to increase information and resources for better hurricane preparedness would reduce the overall impacts and costs associated to future disasters. PR, a US territory, had a 43% poverty rate over three-fold the US rate of 13%, and more than twice that of Mississippi (20%), which had among the highest state poverty rates in 201841. The low socioeconomic status of people in Puerto Rico may have affected and may continue to affect the ability to adequately prepare for hurricanes. Socioeconomic status has also been demonstrated to have an impact in mortality; six month after Hurricane Maria, people with low socioeconomic status remained at higher risk for excess of mortality42.

Our study built on existing cohorts which had several advantages. However, this limited generalizability. Participants were drawn from across Puerto Rico but were not a truly representative sample of all adults in Puerto Rico, as they included participants in a cohort study or patients with pre-existing diabetes receiving care at federally qualified health centers and were limited to 42–75 years old high-risk adults with overweight/obesity. Also, participants who may have had a bigger impact from the hurricanes may have more likely left Puerto Rico and to be excluded from the study 43. Future studies can assess the level of hurricane preparedness, gaps in preparedness, and impact on health in larger longitudinal studies across different age groups.

4.1. Public Health Implications

Our study suggests that, given the low preparedness levels and their associated health impacts, better preparedness is important in helping to reduce morbidity and mortality in the aftermath of future disasters. The hurricanes led to widespread water and power loss and diet changes, which were associated with detrimental health impacts, whereas better hurricane preparedness was associated with lower health impact. Participants reported gaps in resources and information that limited their ability to prepare better. Substantial government, non-profit and personal resources are expended after hurricanes; our results suggest that prioritizing preparedness would be potentially much more effective and less expensive.

People living in areas prone to frequent hurricanes need better information and resources to prepare well for power outages, water loss, and reduced access to food supplies which could help mitigate the detrimental effects of hurricanes on health. Government response could also have had an effect on the health of people who were less prepared. A report published by the Office of Inspector General mentioned that “The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) mismanaged the distribution of commodities in response to Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico. FEMA lost visibility of about 38% of its commodity shipments to Puerto Rico, worth an estimated $257 million. Commodities successfully delivered to Puerto Rico took an average of 69 days to reach their final destinations.”44 In September 2018, 20,000 pallets of bottled water were discovered undistributed in Ceiba.45 Moreover, in January 2020 a warehouse with supplies for Hurricane Maria victims was discovered; items included food, water, cots, and baby formula.46 In addition to individual preparedness, preparedness of government, healthcare, and social organizations is essential to preventing and mitigating the health impacts of future disasters47.

The relevance of these findings extends globally, and additional multidisciplinary research and global efforts are needed. It is important to allocate adequate resources for preparedness and to disseminate information about proper preparedness at individual, national, and global levels to help reduce morbidity and mortality after hurricanes. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic further complicates hurricane preparedness and mitigation, due to the need to wear masks, maintain physical distance, and isolate cases while sheltering, and the competing demands on healthcare and other emergency organizations. The lessons learned from this study are applicable to many locations globally and are even more critical when natural disasters are compounded by additional public health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Conclusion

Improving preparedness is important to reduce the potential detrimental health impact of hurricanes. Better self-reported preparedness, shorter disruption of water services and food accessibility were associated with lower health impact. There are important gaps in information, resources, and practices for hurricane preparedness. Addressing gaps in information and resources could help to improve individual hurricane preparedness and thereby reduce hurricane-related health impact.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Despite a history of hurricanes, 59% were not well prepared for the hurricanes.

Low preparedness is associated with detrimental health impact of hurricanes.

Disruption of drinking water > 3 months was related to detrimental health impact.

Diet changes due to the hurricanes were associated with detrimental health impact.

Several gaps in preparedness, resources and information were identified.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Jeanpaul Fernández, Omar Acevedo, Gabriela Morales, Fabiana De La Matta, Eduardo Rodríguez, Coralys Ortiz, Karla Perez, Ibanaliz Santoni, Angel Aguayo, Kiany Serrano, Fabiola Morales, Radamés Revilla, Dr. Karen Martínez, Dr. Hilton Franqui Rivera, Dr. Ángel López Candales the PRCTRC laboratory and nursing personnel and COSSMA staff and volunteers Anna B. Flores Rolón, Isolina Miranda Sotillo, Dr. Diomarie Martínez Reyes, Dr. Héctor O. Santos Reyes, Lic. Norma Antomattei Velázquez, José Antonio Santiago Vázquez, Charlynne De Jesús Ramos, Héctor R. Álvarez Vázquez, Krystal M. Morales López, Daraishka M. Pérez Caraballo, Gedaliz Leon Ortolaza, Idaliz Ortiz De Villate, Nataly A. Delgado Hernández, Jaisy Vega, and Valerie Molina.

5. Funding Sources

Research reported in this publication was supported by the following grant awards of the National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grants R21MD013666 (PREPARE), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Grant U54MD007587 (PRCTRC), and U54MD007600 (RCMI); National Institutes of General Medical Sciences 1U54GM133807– 01A1(Hispanic Alliance); and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant R01DE020111 (SOALS).

Abbreviations

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- NCD

Non-communicable disease

- SOALS

San Juan Overweight Adults Longitudinal Study

- COSSMA

Corporation of Health Services and Advanced Medicine

- DM

Diabetes Mellitus

- EHR

Electronic Health Records

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- PR

Puerto Rico

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

4. Data Availability

Data related to this article can be requested by writing to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Barrett B, Charles JW, Temte JL. Climate change, human health, and epidemiological transition. Preventive medicine. 2015;70:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NOAA A. Atlantic Hurricane Season takes infamous top spot for busiest on record. 2020;

- 3.Wikipedia. 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season. 2020;

- 4.Freedy JR, Simpson WM Jr. Disaster-related physical and mental health: a role for the family physician. American family physician. 2007;75(6):841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orengo-Aguayo R, Stewart RW, de Arellano MA, Suárez-Kindy JL, Young J. Disaster exposure and mental health among Puerto Rican youths after Hurricane Maria. JAMA network open. 2019;2(4):e192619–e192619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prohaska TR, Peters KE. Impact of natural disasters on health outcomes and cancer among older adults. The Gerontologist. 2019;59(Supplement_1):S50–S56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankenberg E, Gillespie T, Preston S, Sikoki B, Thomas D. Mortality, the family and the Indian Ocean tsunami. The Economic Journal. 2011;121(554):F162–F182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norris FH, Sherrieb K, Galea S. Prevalence and consequences of disaster-related illness and injury from Hurricane Ike. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2010;55(3):221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raker EJ, Zacher M, Lowe SR. Lessons from Hurricane Katrina for predicting the indirect health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(23):12595–12597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heagele TN. Lack of evidence supporting the effectiveness of disaster supply kits. American journal of public health. 2016;106(6):979–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickering CJ, O’Sullivan TL, Morris A, et al. The promotion of ‘Grab Bags’ as a disaster risk reduction strategy. PLOS currents. 2018;10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ablah E, Konda K, Kelley CL. Factors predicting individual emergency preparedness: a multistate analysis of 2006 BRFSS data. Biosecurity and bioterrorism: biodefense strategy, practice, and science. 2009;7(3):317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levac J, Toal-Sullivan D, OSullivan TL. Household emergency preparedness: a literature review. Journal of community health. 2012;37(3):725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapucu N Culture of preparedness: household disaster preparedness. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. 2008; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohn S, Eaton JL, Feroz S, Bainbridge AA, Hoolachan J, Barnett DJ. Personal disaster preparedness: an integrative review of the literature. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2012;6(3):217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Killian TS, Moon ZK, McNeill C, Garrison B, Moxley S. Emergency preparedness of persons over 50 years old: Further results from the health and retirement study. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2017;11(1):80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyota K, Tsukasaki K, Itatani T. Disaster preparedness among families of older adults taking oral medications. Home health care services quarterly. 2018;37(4):325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra S, Suar D. Age, family and income influencing disaster preparedness behaviour. PSYCHOLOGICAL STUDIES-UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT. 2005;50(4):322. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reininger BM, Rahbar MH, Lee M, et al. Social capital and disaster preparedness among low income Mexican Americans in a disaster prone area. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;83:50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cangialosi J, Latto A, Berg R. Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Irma (AL112017)(30 August–12 September 2017) National Hurricane Center, Miami. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crunch C Disaster Year in Review 2019.

- 22.Pasch RJ, Penny AB, Berg R. National Hurricane center tropical cyclone report: Hurricane Maria. TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT AL152017, National Oceanic And Atmospheric Administration and the National Weather Service. 2018:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, et al. Mortality in puerto rico after hurricane maria. New England journal of medicine. 2018;379(2):162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos-Burgoa C, Goldman A, Andrade E, et al. Ascertainment of the estimated excess mortality from hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. 2018;

- 25.Miller AC, Arquilla B. Chronic diseases and natural hazards: impact of disasters on diabetic, renal, and cardiac patients. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2008;23(2):185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rath B, Donato J, Duggan A, et al. Adverse health outcomes after Hurricane Katrina among children and adolescents with chronic conditions. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2007;18(2):405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan BJ, Franklin RC, Burkle FM Jr, et al. Reducing disaster exacerbated non-communicable diseases through public health infrastructure resilience: perspectives of Australian disaster service providers. PLoS currents. 2016;8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma AJ, Weiss EC, Young SL, et al. Chronic disease and related conditions at emergency treatment facilities in the New Orleans area after Hurricane Katrina. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2008;2(1):27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chowdhury MAB, Fiore AJ, Cohen SA, et al. Health Impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on St Thomas and St John, US Virgin Islands, 2017–2018. American journal of public health. 2019;109(12):1725–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonseca VA, Smith H, Kuhadiya N, et al. Impact of a natural disaster on diabetes: exacerbation of disparities and long-term consequences. Diabetes care. 2009;32(9):1632–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velez-Valle EM, Shendell D, Echeverria S, Santorelli M. Type II diabetes emergency room visits associated with Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey: implications for preparedness. Journal of environmental health. 2016;79(2):30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debarati Guha-Sapir WGVP, Lagoutte Joel. Short communication: Patterns of chronic and acute diseases after natural disasters – a study from the International Committee of the Red Cross field hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2007;12(11):1338–1341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman FR, Devgan S. An increase in newly onset IDDM admissions following the Los A ngeles earthquake. Diabetes Care. Mar 1995;18(3):422. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.3.422a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshipura KJ, Muñoz-Torres FJ, Morou-Bermudez E, Patel RP. Over-the-counter mouthwash use and risk of pre-diabetes/diabetes. Nitric Oxide. 2017;71:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NotiCel. Lista de Oasis en Puerto Rico. 2021. https://www.noticel.com/huracanes/el-tiempo/la-calle/20171006/lista-de-oasis-en-pr/

- 36.Telemundo. AAA coordina la distribución de 100 oasis. https://www.telemundopr.com/noticias/puerto-rico/aaa-oasis-agua-huracan-maria-puerto-rico/8520/

- 37.Mozaffarian D Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abramson D, Stehling-Ariza T, Garfield R, Redlener I. Prevalence and predictors of mental health distress post-Katrina: findings from the Gulf Coast Child and Family Health Study. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2008;2(2):77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paxson C, Fussell E, Rhodes J, Waters M. Five years later: Recovery from post traumatic stress and psychological distress among low-income mothers affected by Hurricane Katrina. Social science & medicine. 2012;74(2):150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American psychologist. 1989;44(3):513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.<jo>USC B A Third of Movers From Puerto Rico to the Mainland United States Relocated to Florida in 2018.

- 42.Santos-Burgoa C, Sandberg J, Suárez E, et al. Differential and persistent risk of excess mortality from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico: a time-series analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2018;2(11):e478–e488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinojosa J, Melendez E. Puerto Rican exodus: One year since Hurricane Maria. Center for Puerto Rican Studies. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 44.FEMA Mismanaged the Commodity Distribution Process in Response to Hurricanes Irma and Maria (2020).

- 45.Weir B 20,000 pallets of bottled water left untouched in storm-ravaged Puerto Rico. https://edition.cnn.com/2018/09/12/us/puerto-rico-bottled-water-dump-weir/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perret C Puerto Ricans discovered a warehouse full of unused food, water, and supplies from Hurricane Maria, resulting in the firing of the island’s emergency manager. https://www.insider.com/puerto-rico-residents-find-warehouse-full-of-supplies-from-maria-2020-1

- 47.Noboa-Ramos CA-DY, Fernández E, and Joshipura K. Organizations’ Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery Experience: Lessons Learnt from Hurricane Maria. Journal of Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2021. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data related to this article can be requested by writing to the corresponding author.