Abstract

Background:

Intrathecal opioids are routinely administered during spinal anesthesia for post-cesarean analgesia. The effectiveness of intrathecal morphine for post-cesarean analgesia is well-established, and the use of intrathecal hydromorphone is growing. No prospective studies have compared the effectiveness of equipotent doses of intrathecal morphine versus intrathecal hydromorphone as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen for post-cesarean analgesia. The authors hypothesized intrathecal morphine would result in superior analgesia compared to intrathecal hydromorphone 24 hours after delivery.

Methods:

In this single center, double-blinded, randomized trial, 138 parturients undergoing scheduled cesarean delivery were randomized to receive 150 mcg intrathecal morphine or 75 mcg intrathecal hydromorphone as part of a primary spinal anesthetic and multimodal analgesic regimen;134 were included in the analysis. The primary outcome was numerical rating scale score for pain with movement 24 hours after delivery. Static and dynamic pain scores, nausea, pruritus, degree of sedation, and patient satisfaction were assessed every six hours for 36 hours postpartum. Total opioid consumption was recorded.

Results:

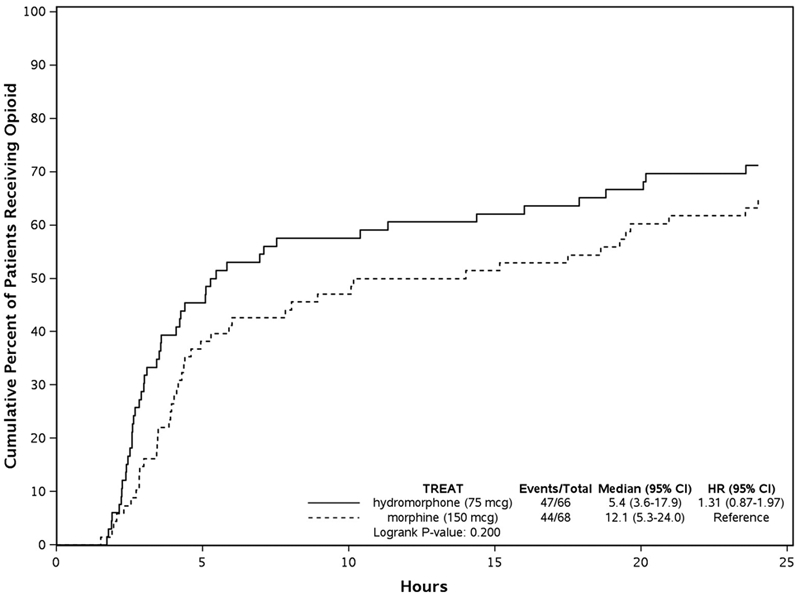

There was no significant difference in pain scores with movement at 24 hours (intrathecal hydromorphone median [25th, 75th] 4 [3, 5] and intrathecal morphine 3[2, 4.5]) or at any time point (estimated difference 0.5, 95% confidence interval, 0-1; P=0.139). Opioid received in the first 24 hours did not differ between groups (median [25th, 75th] oral morphine milligram equivalents for intrathecal hydromorphone 30 [7.5, 45.06] versus intrathecal morphine 22.5 [14.0, 37.5], P=0.769). From Kaplan-Meier analysis, the median time to first opioid request was 5.4 hours for hydromorphone and 12.1 hours for morphine (log rank test P = 0.200).

Conclusions:

Although we hypothesized intrathecal morphine would provide superior analgesia to intrathecal hydromorphone, our results did not confirm this. At the doses studied, both intrathecal morphine and intrathecal hydromorphone provide effective post-cesarean analgesia when combined with a multimodal analgesia regimen.

Introduction

Spinal anesthesia is the most commonly used anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery in the United States and across the world.1 Intrathecal opioids are frequently administered with a local anesthetic during spinal anesthesia for post-cesarean analgesia. Intrathecal morphine is the most widely used opioid for post-cesarean analgesia and its effectiveness is well established.2-6 The prevalence of drug shortages has impacted the supply of preservative-free morphine in the United States and alternative analgesic options have been explored. Retrospective studies have compared intrathecal morphine and hydromorphone.7,8 In addition, one randomized study compared epidural morphine with epidural hydromorphone.9 Previous work by our group found the effective dose for postoperative analgesia in 90% of patients (ED90) after cesarean delivery is 75 mcg for intrathecal hydromorphone and 150 mcg for intrathecal morphine when used as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen.10 There is a paucity of literature prospectively comparing the clinical effect or side-effect profiles of intrathecal morphine versus hydromorphone for analgesia after elective cesarean delivery at equipotent doses.

After intrathecal administration, opioid drug disposition depends on its lipid solubility. Because of morphine’s hydrophilic nature, cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of it decline more slowly than that of more lipophilic drugs. This likely accounts for morphine’s increased rostral spread, greater dermatomal analgesia, and longer duration of action when compared to more lipophilic opioids such as fentanyl and sufentanil. While hydromorphone and morphine have similar molecular structures, hydromorphone is more lipid soluble. This difference in lipid solubility results in a relative decrease in the spread of hydromorphone within the intrathecal space and may influence the duration of action with intrathecal administration.11,12 These differences in lipid solubility between the two medications may influence their duration of action when administered in the intrathecal space. Specifically, this could reduce the duration of actions of intrathecal hydromorphone when compared with intrathecal morphine. Retrospective studies have shown that the analgesic benefit for intrathecal hydromorphone appears to extend at least 12 hours after cesarean delivery and may extend up to 24 hours.10,13

The aim of the current study was to compare the effectiveness and side-effect profiles of intrathecal morphine versus intrathecal hydromorphone for analgesia after cesarean delivery. The primary outcome was pain score with movement at 24 hours after delivery. Our hypothesis was that intrathecal morphine would result in superior analgesia compared to intrathecal hydromorphone at 24 hours after delivery as measured by dynamic pain scores when using equipotent doses.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board in Rochester, MN and the protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02789410) on June 3, 2016 by H.P.S. This manuscript adheres to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. The trial was conducted in accordance to the original protocol, which is available by request. The study was a, double-blinded, parallel group, randomized clinical trial conducted at a single academic institution, Mayo Clinic Hospital (Rochester, Minnesota). Eligible patients were recruited to the study by a member of the study team upon admission to the labor and delivery unit on the day of their scheduled cesarean delivery. Inclusion criteria included American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status II-III, term gestation (37-42 weeks), and desire for a spinal anesthetic for cesarean delivery. Exclusion criteria included contraindication to spinal anesthesia; history of intolerance or adverse reaction to opioid medications; chronic pain syndrome or current opioid use >30 oral morphine milligram equivalents per day; allergy or intolerance to acetaminophen, ketorolac, ibuprofen, or oxycodone; or body mass index greater than 50 kg/m2.

Patients provided written, informed consent and were randomly allocated to one of two study groups: 150 mcg intrathecal morphine or 75 mcg intrathecal hydromorphone. Before study commencement, the study statistician (D.R.S.) created a computer generated randomization schedule using blocks of size N=4 to allocate study arm assignments. Using this randomization schedule, sealed, sequentially numbered, opaque envelopes were created which contained the treatment assignments. Patients, obstetricians, outcome assessors, and study investigators were blinded to the treatment arm. An anesthesia provider not involved in clinical care or performing postoperative patient assessments opened the envelope and prepared the study drug. The study medication (either 0.15 mL of 1 mg/ml concentration morphine sulfate preservative free or 0.75 mL of 100 mcg/mL concentration hydromorphone hydrochloride preservative free) was drawn up in a 1 mL syringe and sterile saline was added to make the total volume 1 mL.

Following randomization, an intravenous catheter was placed and the patient was transported to the operating room where standard ASA monitors were placed and a fluid co-load with Lactated Ringer’s was started. With the patient in a sitting position a 25-gauge Whitacre (BD; Franklin Lakes, NJ USA) needle was introduced into the subarachnoid space at the L2-3, L3-4, or L4-5 interspace in a standard sterile fashion. After return of clear cerebrospinal fluid, 12 mg bupivacaine (1.6 mL 0.75% bupivacaine in 8.25% dextrose), 15 mcg of fentanyl, and the allocated study drug were administered. The parturient was then placed in the supine position with left uterine displacement and an intravenous (IV) phenylephrine infusion was initiated at 0.5 mcg/kg/min, with further titration at the discretion of the anesthesiologist with a goal of maintaining blood pressure within 20% of baseline. Following delivery of the baby, oxytocin was administered per hospital protocol and all patients were given IV granisetron 0.1 mg or IV ondansetron 4 mg for nausea prophylaxis. Supplemental intraoperative analgesia with IV fentanyl 50 to 100 mcg was administered at the discretion of the covering anesthesiologist.

Postoperatively, all patients were treated with a standardized multimodal analgesia regimen, including scheduled acetaminophen 1000 mg orally every 6 hours and ketorolac 15 mg IV every 6 hours for three doses, which was then replaced with ibuprofen 600 mg orally. Oral oxycodone was administered every four hours as needed based on numeric rating scale pain scores: no oxycodone was administered for pain scores less than 4, 5 mg was administered for pain scores rated 4 to 6, and 10 mg was administered for pain scores rated 7 to 10 in intensity. Up to two doses of 50 mcg of IV fentanyl were administered for severe pain unresponsive to the aforementioned interventions. Nausea was treated with granisetron (0.1 mg IV) and/or droperidol (0.625 mg IV) as needed. Pruritus was treated with nalbuphine (5 mg IV) every four hours as needed. Naloxone (0.2 mg IV) was administered for a respiratory rate of <8 or Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale of −3, −4, or −5. The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale, a validated sedation metric, measures sedation from +4 (combative) to −5 (unarousable) on an integer scale, with −3 and −4 being moderate and deep sedation, respectively.14 Patients were monitored with continuous pulse oximetry for the first 24 hours after neuraxial opioid administration. Respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and sedation were monitored every hour for the first 12 hours and every 2 hours for the subsequent 12 hours by nursing staff. Any serious adverse events were to be reported to the Medical Director of Obstetric Anesthesia at Mayo Clinic Hospital, Dr. Hans Sviggum.

Patients were evaluated by study personnel every 6 hours for the first 36 hours after spinal administration. At each time point, the following were collected: pain score at rest, pain score with movement, highest pain score in the preceding 6 hours, severity of nausea (none, mild, moderate, or severe), severity of pruritus (none, mild, moderate, or severe), and overall satisfaction with analgesia (satisfied, somewhat satisfied, neutral, somewhat dissatisfied, or dissatisfied). All pain scores were recorded on an integer 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) numeric rating scale. Study personnel assessed level of sedation and reviewed nurses’ documentation for any episodes of respiratory depression. All assessments were done directly by study personnel, with the exception of any assessment occurring between 12:00 am and 06:00 am, which was usually the 18 hour assessment. For this assessment, patients were asked to fill out a form with the above questions (except the sedation score) upon awakening as close to the scheduled assessment time as possible. Forms were collected by study personnel at the next scheduled assessment.

Maternal characteristics, including age, weight, height, ethnicity/race, gestational age, gravidity, parity, number of previous cesarean deliveries, and procedure length were recorded. Neonatal characteristics, including weight and Apgar scores were collected. Additional information obtained from the electronic medical record included: total opioid consumption at 24 and 36 hours after study drug administration, medical treatments for nausea and pruritus in the first 24 and 36 hours, and hospital length of stay. Opioid medications used were converted into oral morphine milligram equivalents by multiplying by a factor of 0.3 for IV fentanyl, 15 for IV hydromorphone, 1.5 for oral oxycodone, and 0.1 for oral tramadol.15 Data were entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) database.

The primary outcome was pain score with movement 24 hours after spinal administration. Secondary outcomes included severity of opioid-related side effects, including pruritus, nausea, and sedation; total opioid consumption at 24 and 36 hours; pain score at rest at each time point; and the number of treatments for nausea and pruritus at 24 and 36 hours postoperatively.

Statistical analysis:

Continuous variables are summarized using mean ± standard deviation, or median (25th, 75th), and categorical variables are summarized using frequency counts and percentages. Only those subjects with data available at any given time point were included in the analysis. The primary outcome of interest was pain score with movement at 24 hours after delivery. In order to accommodate skewed distributions, pain scores, the amount of opioid received, and hospital length of stay were compared between groups using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Opioid side effects were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test. For the primary outcome, the estimated difference between groups was quantified using the Hodges-Lehmann estimator. In all cases, two-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The median time to first request for postoperative opioid was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method with data censored at 24 hours for patients who did not request opioids in the first 24 postoperative hours. Time to first request for postoperative opioid was compared between groups using the log-rank test and also using proportional hazards regression with results summarized by presenting the point estimate and 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio for hydromorphone versus morphine. For this analysis, the assumption of proportional hazards was assessed by plotting the scaled Schoenfeld residuals versus the time of first opioid. Based on previous work by Sviggum et al.,10 it was hypothesized that the standard deviation of the numeric rating scale pain score at 24 hours was 1.75 units. Under this assumption, it was determined that a sample size of n=65 per group would provide statistical power (two-tailed, alpha=0.05) of approximately 90% to detect a difference between groups of 1.0 unit. Under the assumption that up to 5% of randomized subjects may be excluded for various reasons (e.g. unable to place spinal) a total sample-size of N=138 was used. All analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

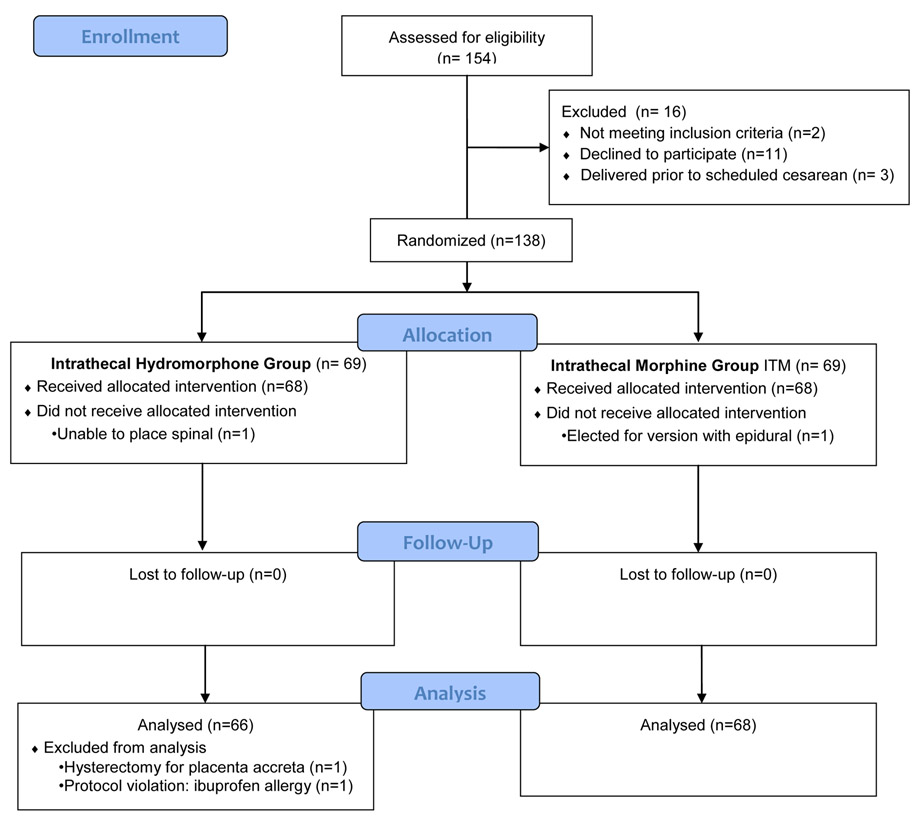

From May 2016 through August 2017, 154 patients were approached about the study and 138 were randomized to either the intrathecal hydromorphone group (n=69) or the intrathecal morphine group (n=69). Enrollment for the study ceased when the target sample size was obtained. A total of 134 women were included in the final analysis, with 66 women in the intrathecal hydromorphone group and 68 women in the intrathecal morphine group. Demographic and baseline characteristics were similar between study groups (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Patients by Treatment Group*

| Characteristic | Hydromorphone (N=66†) |

Morphine (N=68†) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.4±4.3 | 31.9±4.3 | 0.411 |

| Height (cm) | 164.6±7.2 | 165.4±6.7 | 0.407 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.8±19.2 | 78.3±18.2 | 0.735 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.6±6.4 | 28.5±6.2 | 0.942 |

| Gravidity | 0.216 | ||

| 1 | 9 (14) | 10 (15) | |

| 2 | 25 (38) | 34 (50) | |

| 3 | 21 (32) | 16 (24) | |

| ≥4 | 11 (16) | 8 (12) | |

| Parity | 0.534 | ||

| 0 | 11 (17) | 13 (19) | |

| 1 | 33 (50) | 35 (51) | |

| 2 | 18 (27) | 18 (26) | |

| ≥3 | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | |

| Previous cesareans | 0.850 | ||

| 0 | 18 (27) | 19 (28) | |

| 1 | 35 (53) | 37 (54) | |

| ≥2 | 13 (20) | 12 (18) | |

| Tubal Ligation | 0.313 | ||

| No | 53 (80) | 59 (87) | |

| Yes | 13 (20) | 9 (13) | |

| Time of spinal placement | 0.290 | ||

| 06:00 – 09:59 | 49 (74) | 41 (60) | |

| 10:00 – 13:59 | 15 (23) | 24 (35) | |

| 14:00 – 17:59 | 1 (2) | 3 (4) | |

| 18:00 – 21:59 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Duration of Surgery (minutes) | 0.369 | ||

| median (25th, 75th) | 59 (51, 69) | 62 (50, 78) | |

| min, max | 35 to 111 | 30 to 204 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 0.173 | ||

| median (25th, 75th) | 39.0 (39.0, 39.2) | 39.1 (39.0, 39.2) | |

| Range | 37.0 to 40.4 | 37.0 to 40.3 | |

| Fetal weight* (g) | 0.393 | ||

| median (25th, 75th) | 3410 (3070, 3685) | 3460 (3250, 3730) | |

| Range | 2090 to 4440 | 2590 to 4370 | |

| Apgar at 1 minute* | 0.496 | ||

| median (25th, 75th) | 8 (8, 9) | 9 (8, 9) | |

| Range | 1 to 9 | 3 to 9 | |

| Apgar at 5 minutes* | 0.044 | ||

| median (25th, 75th) | 9 (9, 9) | 9 (9, 9) | |

| Range | 7 to 9 | 7 to 9 |

For the morphine group data are summarized for 67 newborns. Data are excluded for one subject who delivered twins.

Data are presented using mean±SD or median (25th, 75th) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. Tubal ligation was compared between groups using the chi-square test and all other characteristics were compared between groups using the rank sum test.

Pain Scores

At 24 h (primary outcome), there was not a significant difference between groups in pain with movement (Table 2). There was no significant difference between pain scores with movement at any time point. Maximum pain scores did not differ between the two groups at any time point. There was a statistically significant decrease in pain scores at rest for the intrathecal morphine group at 18 hours (P = 0.035) (see Table 2). There was no significant difference between pain scores at rest at any other time point. For each of the 3 pain scores (pain at rest, pain with movement, highest pain), the area under the curve over the first 36 hours did not differ significantly between groups.

Table 2:

Pain outcomes*

| Hydromorphone | Morphine | Estimated Difference‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (N=†) | (N=†) | Estimate | (95% CI) | p-value |

| 6 hours | |||||

| Pain at rest | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2.5) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.371 |

| Pain with movement | 3 (2, 6) | 4 (3, 5) | −0.5 | (−1, 0) | 0.183 |

| Highest pain | 4 (2, 6) | 5 (4, 6) | −0.5 | (−1, 0) | 0.202 |

| 12 hours | |||||

| Pain at rest | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.227 |

| Pain with movement | 3 (2, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | 0 | (−1, 1) | 0.751 |

| Highest pain | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 5.5) | 0 | (−1, 1) | 0.765 |

| 18 hours | |||||

| Pain at rest | 2 (1, 4) | 2 (0, 2 ) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.035 |

| Pain with movement | 3.5 (3, 6) | 4 (2, 4) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.137 |

| Highest pain | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 5) | 0 | (−1, 1) | 0.596 |

| 24 hours | |||||

| Pain at rest | 2 (1, 2) | 1 (0.5, 2) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.318 |

| Pain with movement | 4 (3, 5) | 3 (2, 4.5) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.139 |

| Highest pain | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 6) | 0 | (−1, 1) | 0.543 |

| 30 hours | |||||

| Pain at rest | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.241 |

| Pain with movement | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 5) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.155 |

| Highest pain | 5 (4, 6) | 5 (3, 6) | 0 | (−1, 1) | 0.839 |

| 36 hours | |||||

| Pain at rest | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 0 | (−1, 1) | 0.941 |

| Pain with movement | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 5) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.526 |

| Highest pain | 5 (3.5, 6) | 5 (4, 6) | 0.5 | (0, 1) | 0.402 |

| Area Under the Curve | |||||

| Pain at rest | 1.8 (1.0, 2.7) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.3) | 0.25 | (−0.17, 0.67) | 0.173 |

| Pain with movement | 3.7 (2.8, 5.2) | 3.8 (2.7, 4.8) | 0.25 | (−0.33, 0.83) | 0.469 |

| Highest pain | 4.5 (3.2, 5.8) | 4.5 (3.3, 5.3) | 0.08 | (−0.50, 0.67) | 0.298 |

Data are summarized using median (25th, 75th) and compared between groups using the rank sum test.

For the hydromorphone group data were available for 64 subjects at 12 and 36 hours, and 65 subjects at all other time points. For the morphine group data were available for 66 subjects at 36 hours, 67 subjects at 18 and 30 hours, and 68 subjects at all other time points. The area under the curve was calculated for subjects who had data available for all time points (N=63 and N=66 for hydromorphone and morphine respectively).

Hodges-Lehmann estimated difference between groups (Hydromorphone – Morphine).

CI= confidence interval

Opioid Use

Opioid use between the two groups was not significantly different (Table 3). In the first 24 hours, the percentage of parturients who received opioids was 71% (47/66) in the intrathecal hydromorphone group and 65% (44/68) in the intrathecal morphine group (P = 0.463). Among parturients who received opioids, the median (interquartile range) was 30.0 mg (7.5, 45.0) oral morphine equivalents in the intrathecal hydromorphone group compared to 22.5 mg (15.0, 37.5) oral morphine equivalents in the intrathecal morphine group (P = 0.769). There was no difference in the time to the first request for postoperative opioid between the groups (hazard ratio = 1.31, 95% C.I. 0.87 to 1.97) (Figure 2). From Kaplan-Meier analysis, the median time to the first opioid was 5.4 hours for hydromorphone and 12.1 hours for morphine (log rank test P = 0.200).

Table 3:

Other outcomes

|

Characteristic |

Hydromorphone (N=66) |

Morphine (N=68) |

P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the first 24 hours | |||

| Opioid** | |||

| Any received | 47 (71) | 44 (65) | 0.463 |

| Amount received†, mg | 30.0 (7.5, 45.0) | 22.5 (15.0, 37.5) | 0.769 |

| Nausea | |||

| Self-report or treatmentⱡ | 30 (45) | 32 (47) | 0.864 |

| Treatment | 22 (33) | 22 (32) | >0.999 |

| Pruritus | |||

| Self-report or treatmentⱡ | 41 (62) | 41 (60) | 0.861 |

| Treatment | 7 (11) | 13 (19) | 0.226 |

| Sedation§ | 1 (2) | 3 (4) | 0.321 |

| Unsatisfied with analgesia | 5 (8) | 7 (10) | 0.764 |

| Hospital Length of Stay, days | 0.814 | ||

| 1 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| 2 | 23 (35) | 23 (34) | |

| 3 | 42 (64) | 43 (63) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

All values reported as n(%) except as noted.

The amount of opioid received and hospital length of stay are compared between groups using the rank sum test. Other characteristics are compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test.

Does not include intraoperative fentanyl.

Only for those who received opioids are included (N=47 and N=44 for hydromorphone and morphine respectively), reported as median (25th, 75th). Reported in oral morphine milligram equivalents.

Defined as reporting symptoms as moderate or severe or receiving pharmacologic treatment for symptoms

Defined as any negative score on the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale.

Figure 2:

Cumulative Incidence of Postoperative Opioid Use. Kaplan-Meier plot showing the cumulative incidence of postoperative opioid use over the first 24 hours according to the treatment group. The median time to the first opioid was 5.4 hours for hydromorphone and 12.1 hours for morphine (log rank test p = 0.200). CI = confidence interval; HR = Hazard Ratio

Side Effects

There was no significant difference in the number of patients who reported moderate or severe symptoms, and no difference in those who required treatment for either nausea or vomiting (Table 3). Nausea significant enough to require medication administration in the first 24 hours occurred in 22 of 66 (33%) patients in the intrathecal hydromorphone group and 22 of 68 (32%) patients in the intrathecal morphine group (P = >0.999). There was no difference in the number of patients that required medical intervention for pruritus in the intrathecal hydromorphone group 7/66 (11%) compared to the intrathecal morphine group 13/68 (19%) (P = 0.226). There were no episodes of respiratory depression in any patients in either group as indicated by respiratory rate less than 8 breaths per minute or a desaturation event with oxygen saturation less than 92%. The sedation score did not differ between groups. The length of hospital stay did not differ between groups.

The percentage of patients who were not satisfied with their pain control at one or more time points (rated their satisfaction as “neutral”, “somewhat dissatisfied”, or “dissatisfied”) did not differ between groups (intrathecal hydromorphone 5/66 [8%] and intrathecal morphine 7/68 [10%]; P = 0.764). Among those patients who were not satisfied, 92% (11/12) received additional opioids postoperatively compared to 66% (80/122) of patients were satisfied (which included patients reporting “somewhat satisfied” or “satisfied” only) (P = 0.065). Among those who received additional postoperative opioids, those who were not satisfied with their analgesia at one or more time points received significantly (P = 0.023) higher doses of opioids in comparison to those who were satisfied (median [25th, 75th]) 45 mg [33, 75] oral morphine equivalents for those who were unsatisfied vs 22.5 mg [7.5, 37.5] oral morphine equivalents for those satisfied with their analgesia).

Discussion

The main finding of this randomized clinical trial was that pain scores with movement at 24 hours were not different between patients receiving intrathecal morphine and intrathecal hydromorphone as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen for scheduled cesarean delivery. In addition, there were no differences in pain with movement or maximum pain at any time point from 6 to 36 hours after delivery. Side effects including nausea, pruritus, and respiratory depression also did not differ. Of note, the median time to first opioid was 5.4 hours for intrathecal hydromorphone and 12.1 hours for intrathecal morphine. Although not statistically different, this difference may be clinically relevant.

The gold standard for analgesia following cesarean delivery is neuraxial morphine. Our group previously determined the ED90 for intrathecal morphine to be 150 mcg and for intrathecal hydromorphone to be 75 mcg based on pain scores measured 12 hours after adminstration.10 An additional study by Lynde determined the ED50 of hydromorphone for postoperative analgesia following cesarean delivery to be 4.6 mcg based on pain scores measured 12 hours after administration.16 However, the duration of analgesia and side effect profiles of the two medications had not been prospectively compared. Beatty et al. retrospectively compared parturients who received 100 mcg intrathecal morphine and 40 mcg intrathecal hydromorphone and did not find a statistically significant difference in median total opioid consumption and pain scores in the first 24 hours.7 However, Marroquin et al. retrospectively compared both epidural and intrathecal morphine and hydromorphone and found that 60 mcg intrathecal hydromorphone had a shorter duration of analgesia than 200 mcg intrathecal morphine. They were unable to collect pain scores in their study.8 Neither of these aforementioned studies likely utilized the two drugs in equipotent doses.7,8

Unfortunately, guidelines for the equianalgesic conversion of intrathecal morphine to hydromorphone are not yet established, leaving clinicians to rely on expert opinion, clinical experience, and data in parenteral dosing studies. Given the different mechanism of action of intrathecal opioids from parenteral opioids, common parenteral conversion factors may not translate to the intrathecal route.17 Rathmell et al., report 100-200 mcg intrathecal morphine produces similar analgesia to 50-100 mcg intrathecal hydromorphone, suggesting an approximate 2:1 morphine:hydromorphone ratio.12 The two prospective dose-finding studies by Lynde16 and Sviggum et al10 and 3 retrospective studies7,8,13 utilized a wide dose range of intrathecal hydromorphone from 4.6 mcg to 100 mcg. Given this limited data, we chose to evaluate intrathecal morphine to intrathecal hydromorphone at a 2:1 ratio based chiefly on our previously published work evaluating equipotency in a similar patient population.10

Our hypothesis was that at these previously established equipotent doses, intrathecal morphine would result in superior analgesia at 24 hours than intrathecal hydromorphone, but our results did not confirm this. We found no statistically significant difference in reported pain scores with movement at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours. Curiously, there was a single time point at 18 hours where pain scores at rest were significantly lower in the intrathecal morphine group. However, given the lack of statistical difference with movement at this time point, or difference in pain scores at any other time point, this statistical finding has unclear significance.

While the difference in median time to first opioid use (5.4 hours intrathecal hydromorphone vs. 12.1 hours intrathecal morphine) was not statistically significant, it is arguably clinically relevant. In addition, the median oral morphine equivalents between the groups (30 mg intrathecal hydromorphone vs. 22.5 mg intrathecal morphine) may be considered clinically relevant. It is possible that our study was underpowered to detect a subtle superiority of intrathecal morphine over intrathecal hydromorphone in terms of postoperative opioid use. Additional study is required to further explore these associations.

Although effective in reducing pain, intrathecal opioids are associated with side effects including pruritus, nausea, and respiratory depression. A meta-analysis reviewing twenty-eight studies which investigated intrathecal morphine versus placebo demonstrated moderately increased incidences of pruritus, nausea, and vomiting.3 In fact, the incidence of nausea with intrathecal morphine has been reported to be up to 52%3,18,19 with increased nausea or vomiting with increasing dose. The differences in pharmacokinetics between morphine and hydromorphone may result in differences in side effect profiles. Hydromorphone has less hydrophilicity than morphine and less rostral spread which theoretically could result in less pruritus and nausea. Although some studies have found that neuraxial hydromorphone produces fewer side effects (including pruritus) than morphine,20,21 most obstetric studies have not found a difference.7-9 This study also found no difference between these two medications.

While nausea and pruritus are two of the most common side effects of intrathecal opioids, sedation and respiratory depression are the most concerning. In this study, sedation scores did not differ between the two groups and there were no cases of respiratory depression in either group. Recently, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology published a consensus statement on monitoring and treatment for neuraxial opioid-induced respiratory depression.22 This statement states that “hydromorphone has not been studied as thoroughly and lacks the track record of safety that neuraxial morphine has, and therefore if available, intrathecal morphine is the preferred single-shot intrathecal opioid in this setting.” 22 Because clinically significant respiratory depression is a rare event, it will be necessary to report the sedation and respiratory depression outcomes for a large number of patients to evaluate the safety of neuraxial hydromorphone for this side effect. The results of the current study add to previous studies of intrathecal hydromorphone for post-cesarean analgesia that have reported no cases of respiratory depression.7,8,10,13

Drug shortages are an ongoing problem worldwide. A study of Canadian anesthesiologists found approximately 66% of survey respondents had experienced a shortage of one or more anesthesia or critical care medications and 15.2% had experienced a shortage of an opioid medication in the prior year. Additionally, 49% of respondents believed that as a result of drug shortages, they had given an inferior anesthetic and 30% were giving medications with which they were unfamiliar.23 Recently, there has specifically been a shortage of preservative-free morphine in the United States. The results of this study should provide reassurance to anesthesiologists that intrathecal hydromorphone could be a reasonable substitute with similar clinical effect and side effect profile to intrathecal morphine.

This study has a few limitations. Notably, pain scores during movement at 24 hours may not be the most ideal end point for determining the effectiveness of analgesic medications. This primary endpoint was chosen based on the expected duration of analgesia of the medications, its importance to patient satisfaction, and the clarity of data collection and comparison. Using a different primary endpoint (e.g. opioid consumption) or co-primary endpoints might have altered the results. Secondly, the use of multimodal analgesia, including intrathecal fentanyl, while appropriate in clinical practice, potentially limits the observed difference in pain scores between groups. It is possible that eliminating scheduled acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and intrathecal fentanyl could have changed the observed pain scores and analgesic use in such a way that group differences would have been apparent. Thirdly, we did not employ a standardized methodology for obtaining pain scores with movement, which could have confounded the reported scores. We chose pain scores at 24 hours for the current study and the ED90 for intrathecal hydromorphone and intrathecal morphine were based on achieving a pain score ≤3 at 12 hours in our prior study.10 The 2:1 ratio of morphine to hydromorphone used in this study resulted in no statistically significant differences in postoperative analgesia. Using a different ratio of intrathecal morphine to intrathecal hydromorphone (e.g. 3:1) may have created clinical outcome differences in post-cesarean analgesia and likely side effects. Functional recovery measures, although more difficult to obtain, may provide a more holistic view of patient well-being. Additionally, although we powered our study to have a 90% probability of detecting a statistically significant difference in the numeric pain rating scale of 1 or more points (two-tailed test, alpha 0.05), this study may have been underpowered to detect clinically significant differences in our secondary outcomes. For example, the estimated median time to first request for postoperative opioids was 5.4 hours vs 12.1 hours for patients receiving hydromorphone vs morphine, and based on the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio (0.87 to 1.97) our study cannot rule-out the possibility that outcome occurs substantially sooner for those receiving hydromorphone. Results of the present study may not be generalizable to patients with chronic pain or opiate use. Lastly, although considerable effort was made to collect data at multiple meaningful time points, it is possible that meaningful differences might have been apparent if an alternative timing of data collection had been used.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the use of 75 mcg intrathecal hydromorphone for cesarean delivery produces postoperative analgesia of similar effectiveness at 24 hours as that produced by 150 mcg intrathecal morphine when used as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen. Additionally, the side effect profile between these medications is similar. Anesthesia providers should feel comfortable administering either intrathecal hydromorphone or intrathecal morphine as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen to care for patients undergoing cesarean delivery.

Figure 1:.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement: This publication was supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Clinical trial number: NCT02789410; Clinicaltrials.gov; (Registration Date: 6/3/2016); Principal investigator: Hans P Sviggum, MD

Prior presentations: This study was presented at the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology 2018 Annual Meeting in Miami, FL on May 10, 2018

Summary statement: not applicable

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bucklin BA, Hawkins JL, Anderson JR, Ullrich FA: Obstetric anesthesia workforce survey: twenty-year update. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 645–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer CM, Emerson S, Volgoropolous D, Alves D: Dose-response relationship of intrathecal morphine for postcesarean analgesia. Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 437–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gehling M, Tryba M: Risks and side-effects of intrathecal morphine combined with spinal anaesthesia: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2009; 64: 643–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abboud TK, Dror A, Mosaad P, Zhu J, Mantilla M, Swart F, Gangolly J, Silao P, Makar A, Moore J, Davis H, Lee J: Mini-dose intrathecal morphine for the relief of post-cesarean section pain: safety, efficacy, and ventilatory responses to carbon dioxide. Anesth Analg 1988; 67: 137–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen SE, Desai JB, Ratner EF, Riley ET, Halpern J: Ketorolac and spinal morphine for postcesarean analgesia. Int J Obstet Anesth 1996; 5: 14–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milner AR, Bogod DG, Harwood RJ: Intrathecal administration of morphine for elective Caesarean section. A comparison between 0.1 mg and 0.2 mg. Anaesthesia 1996; 51: 871–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beatty NC, Arendt KW, Niesen AD, Wittwer ED, Jacob AK: Analgesia after Cesarean delivery: a retrospective comparison of intrathecal hydromorphone and morphine. J Clin Anesth 2013; 25: 379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marroquin B, Feng C, Balofsky A, Edwards K, Iqbal A, Kanel J, Jackson M, Newton M, Rothstein D, Wong E, Wissler R: Neuraxial opioids for post-cesarean delivery analgesia: can hydromorphone replace morphine? A retrospective study. Int J Obstet Anesth 2017; 30: 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halpern SH, Arellano R, Preston R, Carstoniu J, O'Leary G, Roger S, Sandler A: Epidural morphine vs hydromorphone in post-caesarean section patients. Can J Anaesth 1996; 43: 595–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sviggum HP, Arendt KW, Jacob AK, Niesen AD, Johnson RL, Schroeder DR, Tien M, Mantilla CB: Intrathecal Hydromorphone and Morphine for Postcesarean Delivery Analgesia: Determination of the ED90 Using a Sequential Allocation Biased-Coin Method. Anesth Analg 2016; 123: 690–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bujedo BM: Spinal opioid bioavailability in postoperative pain. Pain Pract 2014; 14: 350–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathmell JP, Lair TR, Nauman B: The role of intrathecal drugs in the treatment of acute pain. Anesth Analg 2005; 101: S30–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauch E: Intrathecal hydromorphone for postoperative analgesia after cesarean delivery: a retrospective study. Aana j 2012; 80: S25–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK: The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166: 1338–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, Hanna M, Kalso E, McQuay HJ, Mercadante S, Meynadier J, Poulain P, Ripamonti C, Radbruch L, Casas JR, Sawe J, Twycross RG, Ventafridda V: Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations. Br J Cancer 2001; 84: 587–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynde GC: Determination of ED50 of hydromorphone for postoperative analgesia following cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth 2016; 28: 17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorlin AW, Rosenfeld DM, Maloney J, Wie CS, McGarvey J, Trentman TL: Survey of pain specialists regarding conversion of high-dose intravenous to neuraxial opioids. J Pain Res 2016; 9: 693–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nortcliffe SA, Shah J, Buggy DJ: Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after spinal morphine for Caesarean section: comparison of cyclizine, dexamethasone and placebo. Br J Anaesth 2003; 90: 665–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sultan P, Halpern SH, Pushpanathan E, Patel S, Carvalho B: The Effect of Intrathecal Morphine Dose on Outcomes After Elective Cesarean Delivery: A Meta-Analysis. Anesth Analg 2016; 123: 154–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodarzi M: Comparison of epidural morphine, hydromorphone and fentanyl for postoperative pain control in children undergoing orthopaedic surgery. Paediatr Anaesth 1999; 9: 419–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaplan SR, Duncan SR, Brodsky JB, Brose WG: Morphine and hydromorphone epidural analgesia. A prospective, randomized comparison. Anesthesiology 1992; 77: 1090–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauchat JR, Weiniger CF, Sultan P, Habib AS, Ando K, Kowalczyk JJ, Kato R, George RB, Palmer CM, Carvalho B: Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Consensus Statement: Monitoring Recommendations for Prevention and Detection of Respiratory Depression Associated With Administration of Neuraxial Morphine for Cesarean Delivery Analgesia. Anesth Analg 2019; 129: 458–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall R, Bryson GL, Flowerdew G, Neilipovitz D, Grabowski-Comeau A, Turgeon AF: Drug shortages in Canadian anesthesia: a national survey. Can J Anaesth 2013; 60: 539–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]