The rate of tuberculosis in London, UK, has not reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. This might be surprising given that tuberculosis is airborne, and suggests important lessons about the transmission and treatment of the disease.

Although tuberculosis has been declining in the UK since 2011, incidence before the COVID-19 pandemic remained relatively high in London at 16 cases per 100 000 residents in 2020, double the UK average, and as high as 43 per 100 000 among residents of the deprived and ethnically diverse borough of Newham in east London. WHO considers a country to have a high incidence of tuberculosis if more than 40 people per 100 000 per year are diagnosed with tuberculosis.

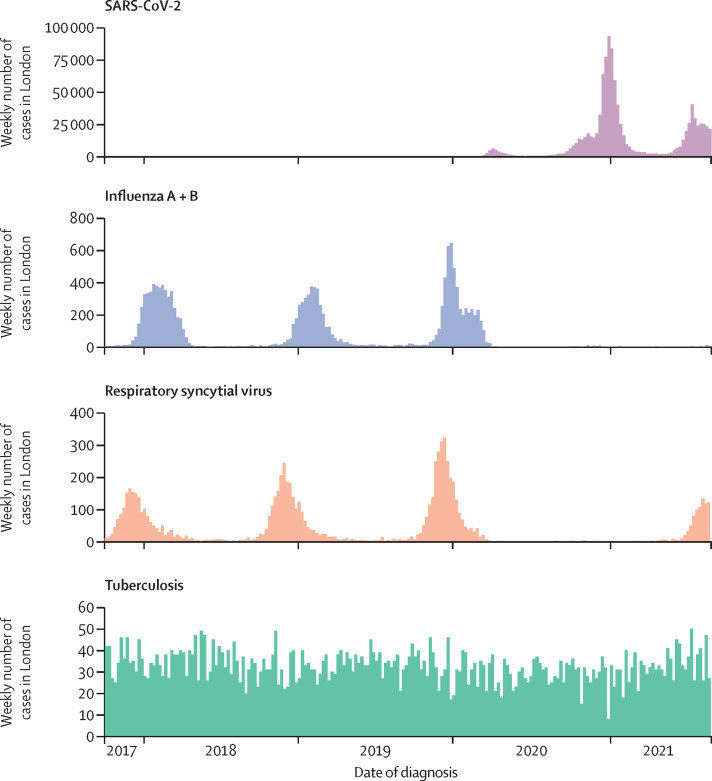

When non-pharmaceutical interventions and lockdowns were introduced to limit COVID-19 in March, 2020, tuberculosis cases were expected to reduce. Other respiratory infections were profoundly affected. The usual influenza season did not happen in winter 2020–21: in London, in December, 2020, there were 19 confirmed cases of influenza, compared with 1947 in December, 2019. This is likely due to reduced transmission rather than a lack of testing for influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, in winter 2020–21, there were few cases of respiratory syncytial virus, a common cause of hospitalisation of infants.

We expected that tuberculosis would also be affected for two reasons. First, tuberculosis transmission might be reduced due to restrictions on social mixing, closure of workplaces, bars, and restaurants, and limitations on local and international travel. These changes might reduce the number of cases that result from recent exposure. Such an effect would likely be lagged because tuberculosis has a latent (or incubation) period, which varies widely between patients and settings but is usually less than 2 years, and after onset of symptoms there is often a delay of several months before diagnosis. The distribution of these periods is skewed: some individuals have short periods between exposure and diagnosis (for example 3–6 months), while for some this period might be many years. If COVID-19 restrictions affected incidence of tuberculosis, we would expect some difference in the rate of diagnoses by summer 2021; more than a year after non-pharmaceutical interventions were first introduced.

Second, all health services have worked differently during the pandemic and many have been less accessible. This might have meant people with tuberculosis are less likely to seek help for symptoms such as coughing and fatigue, while tuberculosis specialists and general practitioners might be less accessible with longer waiting lists. There has been international concern that COVID-19 would reduce access to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment. WHO reported that the number of tuberculosis diagnoses globally reduced from 7·1 million in 2019 to 5·8 million in 2020, with these reductions concentrated in India, Indonesia, and the Philippines, while conversely the number of deaths increased. WHO concluded that “for the first time in over a decade, TB deaths have increased because of reduced access to TB diagnosis and treatment in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic”. At the start of the pandemic, many tuberculosis specialists were concerned that something similar would happen in the UK, with fewer but more severe cases presenting to services, and an increasing number of undiagnosed cases in the community.

However, tuberculosis is a very different disease to respiratory viruses such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus. It is much less seasonal; it has a long latent period (months or years rather than days), and it is closely associated with social deprivation. It is possible that COVID-19 interventions have a different impact on groups most affected by tuberculosis in London, such as those living in larger households, people experiencing homelessness, and communities that often visit countries with high incidence of tuberculosis. These groups might be unable to avoid social mixing or work in jobs that cannot be done at home. The potential impact of COVID-19 on tuberculosis was therefore uncertain.

The London TB Register (LTBR), a surveillance database maintained by the UK Health Security Agency, shows the number and characteristics of all tuberculosis cases diagnosed in London. These data show that an average of 4·1 cases of tuberculosis were diagnosed per day in London during the first lockdown (March–June, 2020); only slightly lower than 4·7 per day over the previous 12 months. This slight reduction might be part of a decade-long decline in tuberculosis. There is some evidence that this trend reversed after the first lockdown, reaching an average 5·0 cases per day in summer 2021. More time will be needed before this trend becomes clear. There has evidently not been the dramatic reduction in cases seen for other respiratory infections (figure ).

Figure.

Number of diagnosed cases per week for selected respiratory infections in London, UK

The number of SARS-CoV-2 cases in early 2020 (ie, the first wave) appears low due to limited availability of testing; the true number of cases was substantially greater.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of cases during the pandemic has also been similar to patients before the COVID-19 pandemic, with an average age of approximately 40 years, six of ten patients being male, and approximately 5% of infections being resistant to the first-line antibiotics. Most importantly, the duration between reported symptom onset and diagnosis has remained at about 3 months, suggesting that people with tuberculosis in London are not waiting until symptoms are more severe before seeking help.

This appears different to the global pattern of fewer patients treated for tuberculosis. It suggests that tuberculosis services in London have remained accessible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Like many health services, tuberculosis services in London struggled during COVID-19 due to staff shortages and the need to limit face-to-face contact. They used more remote assessments, reduced home visits, and reduced directly observed therapy, in which patients take antibiotics at regular in-person clinic visits, allowing clinicians to monitor treatment regimens and the patient's general health. Despite these changes, tuberculosis services in London have diagnosed similar numbers of cases each day.

One possible reason for the continued incidence of tuberculosis during COVID-19 is that most cases arise from long-term latent infections. The balance of active tuberculosis cases attributable to recent exposure compared with reactivation of long-term latent infection is unclear and might be changing over time and varying with local tuberculosis incidence. Studies in England suggest that a small proportion of cases (4% and 11% in two studies) are attributable to recent local transmission. This might suggest that most active infections are attributable to latent infections acquired long ago; possibly explaining the continued incidence of tuberculosis in London, despite reduced social contact during the pandemic.

Another possible reason is that tuberculosis transmission continued during the pandemic in settings and communities most affected by tuberculosis, such as multigenerational households and those experiencing homelessness. Tuberculosis cases during the COVID-19 pandemic had similar characteristics to those before the pandemic, including similar prevalence of homelessness, problematic drug use, and mental health problems, suggesting that the continued incidence of tuberculosis is not explained by increased concentration of the disease in these populations.

Most surprisingly, the London TB Register shows that the rate of tuberculosis diagnosis might now be increasing. Possible reasons for a gradual increase in diagnoses during COVID-19 include: (1) more mixing in private homes during lockdowns, which might also be higher risk settings for tuberculosis transmission than public places and workplaces; (2) co-infection with COVID-19 might increase the infectiousness of tuberculosis, for example through increased coughing; (3) COVID-19 infection might increase susceptibility to tuberculosis infection or reactivation; (4) increased help-seeking for more severe or long-term respiratory symptoms due to awareness of COVID-19. Some of these theories could be investigated by linking patient-level data on tuberculosis or latent tuberculosis testing with COVID-19 testing or hospital data.

The long incubation period of tuberculosis means that changes in incidence happen much more slowly than for influenza and other diseases with rapid onset. The full impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on tuberculosis in London might not yet be clear. However, it is already clear that patients have continued presenting to services and are being diagnosed at a similar rate to before the pandemic. This suggests it is possible to operate tuberculosis services during COVID-19 restrictions in high-income settings. Countries in Africa and south and southeast Asia, with fewer resources and higher incidence of tuberculosis, will need international support to continue treating people with tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.