Abstract

Study Objectives

Sleep restriction (SR) and total sleep deprivation (TSD) reveal well-established individual differences in Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) performance. While prior studies have used different methods to categorize such resiliency/vulnerability, none have systematically investigated whether these methods categorize individuals similarly.

Methods

Forty-one adults participated in a 13-day laboratory study consisting of two baseline, five SR, four recovery, and one 36 h TSD night. The PVT was administered every 2 h during wakefulness. Three approaches (Raw Score [average SR performance], Change from Baseline [average SR minus average baseline performance], and Variance [intraindividual variance of SR performance]), and within each approach, six thresholds (±1 standard deviation and the best/worst performing 12.5%, 20%, 25%, 33%, and 50%) classified Resilient/Vulnerable groups. Kendall’s tau-b correlations examined the concordance of group categorizations of approaches within and between PVT lapses and 1/reaction time (RT). Bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapped t-tests compared group performance.

Results

Correlations comparing the approaches ranged from moderate to perfect for lapses and zero to moderate for 1/RT. Defined by all approaches, the Resilient groups had significantly fewer lapses on nearly all study days. Defined by the Raw Score approach only, the Resilient groups had significantly faster 1/RT on all study days. Between-measures comparisons revealed significant correlations between the Raw Score approach for 1/RT and all approaches for lapses.

Conclusion

The three approaches defining vigilant attention resiliency/vulnerability to sleep loss resulted in groups comprised of similar individuals for PVT lapses but not for 1/RT. Thus, both method and metric selection for defining vigilant attention resiliency/vulnerability to sleep loss is critical.

Keywords: individual differences, sleep deprivation, Psychomotor Vigilance Test, recovery, variance, baseline

Statement of Significance.

Prior studies have used different methods to define resiliency and vulnerability of Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) performance during sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. However, no study has comprehensively investigated whether these methods result in groups comprised of the same individuals. We compared the concordance of group categorizations by three approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, Variance) to define resilience/vulnerability to sleep loss. All three approaches resulted in similar groups for PVT lapses but not for PVT 1/RT. Thus, the method and PVT metric used to define vigilant attention resiliency and vulnerability to sleep loss is crucial. Further, our results have critical implications for future biomarker and countermeasure studies that consider individual differences in vigilant attention responses to sleep loss.

Introduction

Sleep deprivation causes decrements in attention, subjective sleepiness, and mood, among other negative consequences [1–4]. There are well-established individual differences in the neurobehavioral consequences to both sleep restriction (SR) and total sleep deprivation (TSD) [2, 5–8], whereby some individuals are resilient, and others are vulnerable to the impairing effects of sleep loss. These individual differences are large and stable over time [5, 6, 8]. However, while the literature has characterized these individual differences in different ways, these methods have not yet been systematically compared.

Studies have defined resiliency and vulnerability to the effects of sleep loss on different neurobehavioral tasks using numerous methods. One common approach used to define individuals as resilient and vulnerable to sleep loss involves the use of performance or self-rated raw scores [9–13], whereby those with better performance or self-rated scores during sleep loss are considered more resilient and those with worse performance or scores are considered more vulnerable. Other studies have used difference performance or scores that account for baseline [14–20], whereby individuals whose performance or scores during sleep loss improved or showed the least change, as compared to baseline, are considered more resilient. In addition, intra-individual variance in performance has been posited as an explanation for cognitive vulnerability during well-rested conditions [21–23] and for individual differences in performance during sleep loss [3, 24, 25], and may partly consider time-of-day variation in performance [26–29]. However, defining resilience or vulnerability to sleep loss using this approach has not yet been examined.

Previous research has used the aforementioned approaches in combination with various thresholds to categorize individuals as neurobehaviorally resilient or vulnerable to sleep loss. These methods include median split (50% threshold) [9, 12, 13, 15, 16, 20, 30–34], tertile split (33% threshold) [11, 17, 18, 35], and quartile split (25% threshold) [10, 36], as well as the best and worst n = 5 performers [37] and the best and worst n = 8 performers [14]. The use of ±1 standard deviation (SD) as a threshold to group resilient and vulnerable groups also requires investigation. To our knowledge, our study is the first to systematically compare resilient and vulnerable groups resulting from defining vigilant attention resiliency and vulnerability to sleep loss using different approaches (e.g. using actual performance or scores, considering baseline performance, using intraindividual variance) and various thresholds (e.g. median split, tertile split, etc.).

Vigilant attention, a commonly examined neurobehavioral measure that contributes to the functioning of other neurobehavioral domains [38], has consistently shown impairment during sleep loss [4, 7, 9, 11–13]. Moreover, there are robust individual differences in vigilant attention deficits during sleep deprivation, and studies have used various approaches to investigate such differences [6, 9–13, 17]. Notably, few studies have characterized the recovery of vigilant attention performance after sleep loss [1, 4, 12, 39–46], and to our knowledge, no study to date has investigated whether resilient or vulnerable groups defined by vigilant attention performance during sleep loss have differential performance during subsequent extended recovery periods.

To address the variations and gaps in the existing literature pertaining to sleep loss and in the methods for defining and evaluating vigilant attention resiliency and vulnerability, we created resilient and vulnerable groups using three different approaches and six different thresholds, some which have thus far not been investigated. We sought to: (1) systematically evaluate the concordance of the categorization of individuals into resilient and vulnerable groups between different approaches at each discrete threshold within each measure; (2) compare vigilant attention performance of the resilient and vulnerable groups defined by each approach and within each threshold on each day of the study; and (3) evaluate the concordance of the resilient and vulnerable categorization between measures of vigilant attention. We hypothesized the following: (1) individuals would be categorized into resilient and vulnerable groups by the three approaches in a similar manner within each measure; (2) for all three approaches and at all thresholds, vigilant attention performance would be better in the resilient group compared to the vulnerable group on all sleep deprivation days (SR and TSD); and (3) individuals would be categorized into resilient and vulnerable groups in a similar manner between measures.

Methods

Participants

Forty-one healthy adults (ages 21–49; mean ± SD, 33.9 ± 8.9 years; 18 females; 31 African Americans) were recruited in response to study advertisements. Participants were prohibited from using caffeine, alcohol, medications (except oral contraceptives), or tobacco for the 7 days before study entry, as verified by blood and urine screenings. Participants were monitored at home with actigraphy, sleep–wake diaries, and time-stamped call-ins to determine bedtimes and waketimes during the 7–14 days before the laboratory phase. Please refer to Yamazaki et al. [4] for full details on inclusion and exclusion criteria, the pre-study protocol, and prohibited activities.

The protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received compensation for participation.

Procedures

Participants engaged in a 13-day laboratory study in which they were monitored continuously and received daily checks of vital signs and symptoms by nurses (with a physician on call). The study included two nights of baseline sleep of 10 h (baseline day 1 [B1], 2200–0800 h) and 12 h (baseline day 2 [B2], 2200–1000 h) time in bed (TIB) respectively, followed by five consecutive nights of 4 h TIB per night (sleep restriction days 1–5 [SR1–SR5], 0400–0800 h), four consecutive nights of 12 h recovery sleep opportunity (recovery days 1–4 [R1–R4], 2200–1000 h), and 36 h of total sleep deprivation (TSD, 0 h TIB, wakefulness from 1000 h to 2200 h the following day). Polysomnography (PSG) was recorded on certain nights, including B2. Please refer to Yamazaki et al. [4] for details on the laboratory environment and permitted participant activities. Only participants who underwent the SR condition first in Yamazaki et al. [4] were included in the present study in order to prevent confounding effects of undergoing TSD first without a second baseline phase before undergoing SR.

Neurobehavioral measures

A precise computer-based neurobehavioral test battery was administered every 2 h during wakefulness on all days during the study. The test battery included the well-validated 10-min Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) [47], which measures vigilant attention. The number of lapses (reaction time [RT] > 500 ms) and mean response speed (1/RT) on the PVT were used as outcome measures. B1 served as an adaptation day and thus these PVT data were excluded from analyses. Due to protocol scheduling conflicts, PVT data were missing for the B2 2000h (for N = 26 participants), SR5 0800 h (for N = 22 participants), and R1 1000 h (for N = 22 participants) test bouts.

Resilient, vulnerable, and intermediate group determination

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) groups were defined by three approaches, as follows: (1) the Raw Score approach, which averaged performance (PVT lapses or PVT 1/RT) across the SR1 0800 h–SR5 2000 h test bouts for each participant; (2) the Change from Baseline approach, which subtracted mean performance across the B2 1000–2000 h test bouts for each participant from mean performance across the SR1 0800 h–SR5 2000 h test bouts; (3) the Variance approach, which calculated the intraindividual variance in performance across the SR1 0800 h–SR5 2000 h test bouts. If scores from single test bouts were missing, averages were calculated using scores from the remaining available test bouts.

The median and interquartile range (IQR) of average PVT lapses, average change from baseline score, and intraindividual variance for PVT lapses were as follows: 3.341 (4.434); 2.711 (5.048); and 11.222 (37.103), respectively. The median and IQR of average PVT 1/RT, average change from baseline score, and intraindividual variance for PVT 1/RT were as follows: 3.382 (0.749); –0.512 (0.461); and 0.097 (0.128), respectively.

Within each approach, Res and Vul groups were defined by six thresholds as follows: (1) ±1 SD (Res and Vul groups, each N = 0–8); (2) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res and Vul groups, each N = 5); (3) the best and worst performing 20% (Res and Vul groups, each N = 8); (4) the best and worst performing 25% (Res and Vul groups, each N = 10); (5) the best and worst performing 33% (Res and Vul groups, each N = 13); and (6) the best and worst performing 50% (Res group N = 20, Vul group N = 21). For PVT lapses, using the Raw Score and Change from Baseline approaches, the –1 SD and the best performing percentage groups comprised the Res group (e.g. the fewer PVT lapses, the more resilient; the lower the average change from baseline score, the more resilient). For PVT 1/RT, using the Raw Score and Change from Baseline approaches, the +1 SD and best performing percentage groups comprised the Res group (e.g. the faster [greater] PVT 1/RT, the more resilient; the greater the average change from baseline score, the more resilient). For PVT lapses and PVT 1/RT, using the Variance approach, the –1 SD and best performing percentage groups comprised the Res group (i.e. the less intraindividual variance, the more resilient). At each threshold, the remaining participants who were not categorized into the Res or Vul groups were classified as part of the Int group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in the R software environment [48]. BMI, age, and sex composition, as well as pre-study total sleep time (TST, measured by actigraphy from 7–14 days prior to the in-laboratory study) and B2 TST (measured by PSG), were compared between the Res and Vul groups, for each respective approach, for PVT lapses and PVT 1/RT. BMI, age, and TST were evaluated via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at the 12.5%, 33%, and 50% thresholds (comparisons were restricted to three thresholds to limit the number of analyses conducted). Sex was evaluated via the chi-square test at the 50% threshold for PVT lapses and at the 33% and 50% thresholds for PVT 1/RT because the chi-squared test sample size requirements were not met in each cell at the 12.5% and 33% thresholds for PVT lapses or at the 12.5% threshold for PVT 1/RT. Race was not evaluated at any threshold because the chi-squared test sample size requirements were not met in each cell.

Kendall’s tau-b correlations (R package rstatix) [49, 50] compared the categorizations of participants across the three approaches within each measure at each threshold (e.g. categorization of Res, Vul, and Int groups for PVT lapses at the 12.5% threshold for the Raw Score approach vs. for PVT lapses at the 12.5% threshold for the Change from Baseline approach). Additionally, Kendall’s tau-b correlations compared the categorizations of participants into the Res, Vul, and Int groups between measures and at all thresholds (e.g. Res, Vul, and Int categorizations for all approaches and thresholds for PVT lapses vs. Res, Vul, and Int categorizations for all approaches and thresholds for PVT 1/RT). Kendall’s tau-b was used for these comparisons due to its nonparametric nature, and its ability to account for the repeating of values (e.g. ties in the ranking of data points) in the analysis of ordinal data; given these criteria, it is considered more accurate relative to Spearman’s rank correlation for analyzing this dataset [50, 51]. Tau-b strength was defined as tau-b = 0–0.09: zero; 0.10–0.39: weak; 0.40–0.69: moderate; 0.70–0.99: strong; 1.00: perfect [52].

Bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrapped t-tests with 5000 iterations (R package wBoot) [53, 54] compared average PVT lapses or average PVT 1/RT from the 1000–2000 h test bouts between the Res and Vul groups, for each respective approach, and at each threshold on each day of the study (e.g. PVT lapses on B2 in the Res vs. Vul group defined by the Raw Score approach at the 12.5% threshold). BCa bootstrapped t-tests with 5000 iterations also compared average PVT lapses or PVT 1/RT across SR1-SR5 test bouts (e.g. PVT lapses across SR1–SR5 in the Res vs. Vul group defined by the Raw Score approach at the 12.5% threshold).

To account for multiplicity, the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) [55] correction was applied to all bootstrapped t-test p-values and all within-measure and between-measures Kendall’s tau-b correlation p-values separately, in accordance with the approach in which the original analyses were performed. Only 0.385% of these p-values became non-significant when the FDR correction was applied in this manner, and all presented p-values for the t-tests and Kendall’s tau-b correlations are corrected.

Results

Participant characteristics

The PVT lapses and PVT 1/RT Res and Vul groups, defined by all three approaches, did not significantly differ in BMI, age, or sex at the 12.5%, 33%, or 50% thresholds (F(1) = 0.006–4.002, p = 0.052–0.943; χ2(1) = 0–2.462, p = 0.117–1.000), except for in age by the Raw Score approach at the 12.5% threshold for both measures, whereby the Res group was significantly older than the Vul group (F(1) = 9.363–15.960, p = 0.004–0.016; Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, the Res and Vul groups did not differ significantly in pre-study or B2 TST for any approach at the 12.5%, 33%, or 50% thresholds (F(1) = 0.000–3.731, p = 0.066–0.991; Supplementary Table S1).

PVT lapses

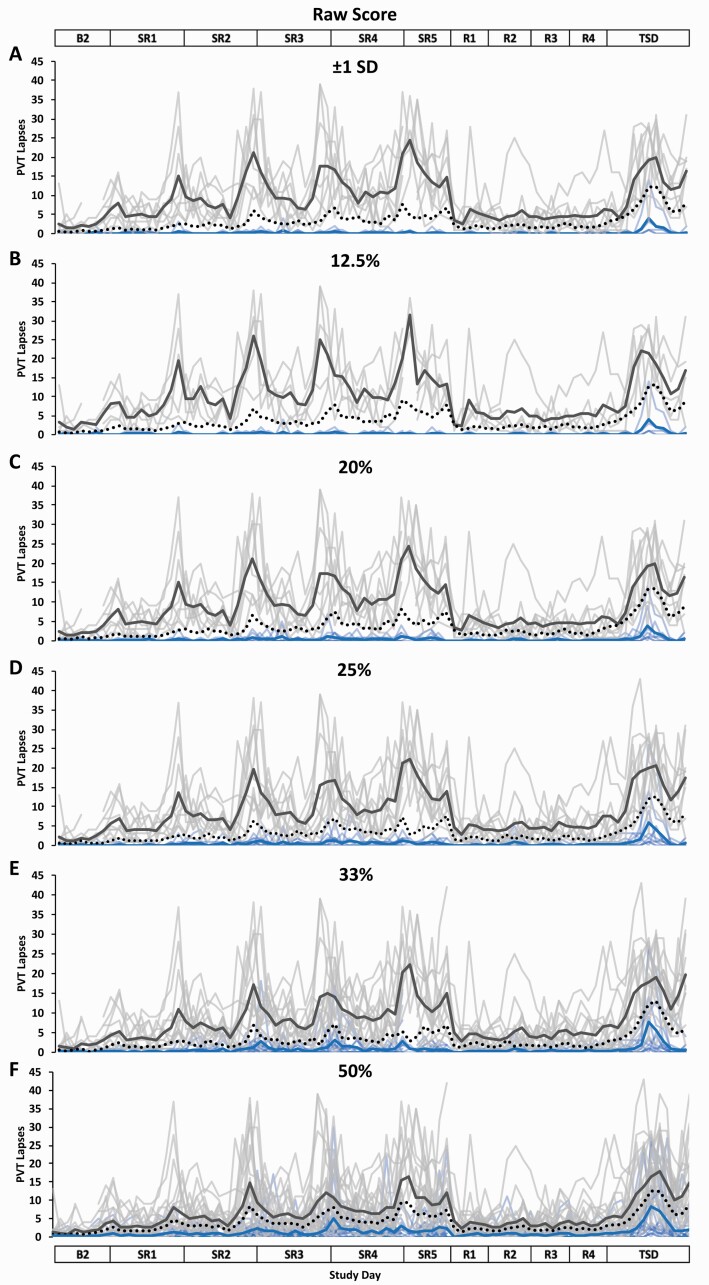

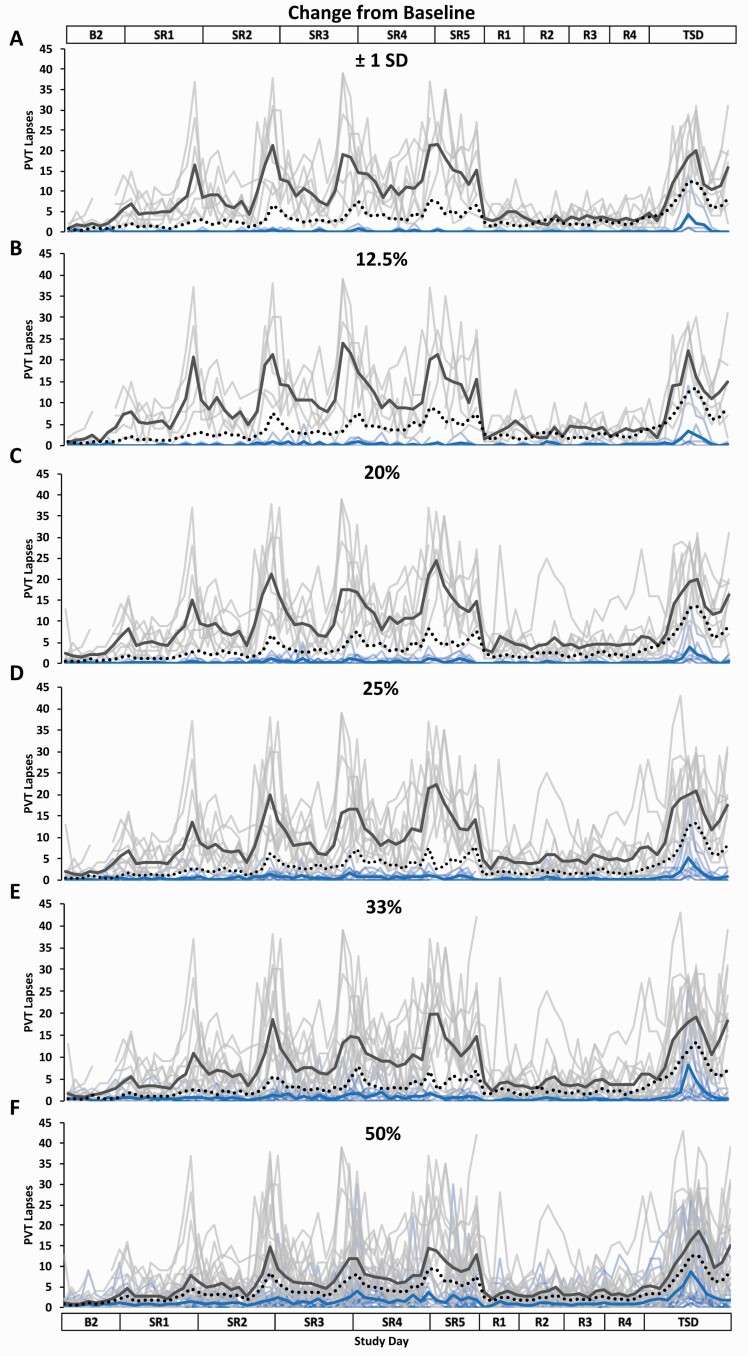

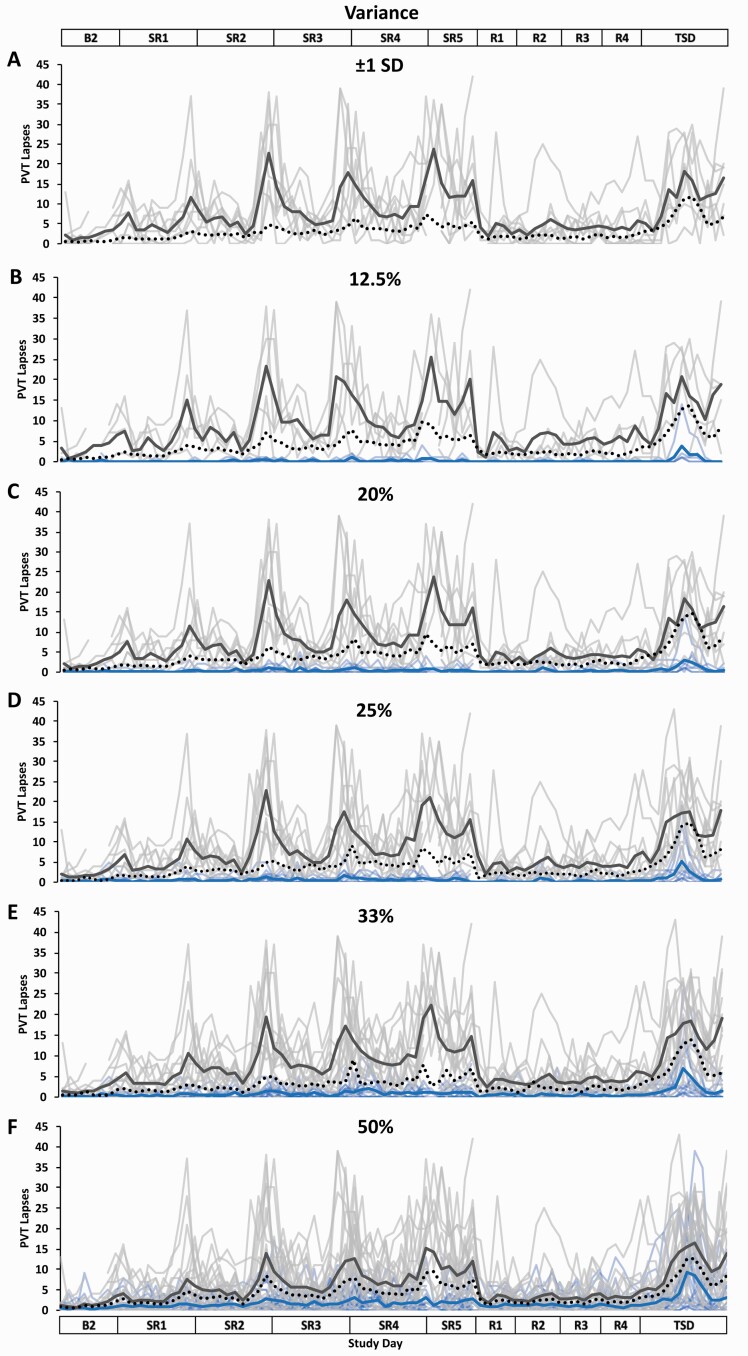

Participants were grouped into Res, Vul, and Int groups by all three approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance) at all thresholds, except for by the Variance approach at ±1 SD, whereby a Res group was not formed (N = 0) due to the absence of individuals whose variance in PVT lapses across SR1–SR5 was less than –1 SD below the mean. For all three approaches at all thresholds, the PVT lapses Res groups had significantly fewer average PVT lapses across SR1–SR5 than the Vul groups (p ≤ 0.001–0.003). The PVT lapses profiles of the Res, Vul, and Int groups across the entire study, defined by the Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance approaches at the six thresholds, are depicted in Figures 1–3, respectively (Supplementary Table S2 shows each individual’s groupings [Res, Vul, or Int group] for each approach at each threshold).

Figure 1.

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) group Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) lapses profiles across the study using six different thresholds within the Raw Score approach. Res, Vul, and Int groups were determined by averaging PVT lapses from all test administrations during sleep restriction days 1–5 (SR1–SR5) (e.g. the fewer PVT lapses, the more resilient) and using the following six thresholds: (A) ±1 standard deviation (SD) (Res N = 5; Vul N = 8; Int N = 28); (B) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res N = 5; Vul N = 5; Int N = 31); (C) the best and worst performing 20% (Res N = 8; Vul N = 8; Int N = 25); (D) the best and worst performing 25% (Res N = 10; Vul N = 10; Int N = 21); (E) the best and worst performing 33% (Res N = 13; Vul N = 13; Int N = 15); (F) the best and worst performing 50% (Res N = 20; Vul N = 21; all N = 41). All Res groups had significantly better performance than their respective Vul groups at all thresholds and on all study days (see Table 2 for detailed daytime performance t-test results). The top and bottom axis labels depict the study design: Baseline day 2 (B2, 1000–2400 h), SR1 (0200 h, 0800–0200 h), SR2–SR4 (0800–0200 h), SR5 (0800–2000 h), Recovery days 1–4 (R1–R4, 1000–2000 h), and total sleep deprivation day (TSD, 2200–2000 h). Light blue lines and light gray lines depict individual PVT lapses profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively; the dark blue and the dark gray line depict averaged PVT lapses profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively. The black dotted line depicts the Int group (except for 50%, for which this line depicts all participants) average PVT lapses profile. Breaks in the lines indicate missing data.

Figure 2.

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) group Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) lapses profiles across the study using six different thresholds within the Change from Baseline approach. Res, Vul, and Int groups were determined by subtracting each participant’s mean PVT lapses score across baseline day (B2) from their mean PVT lapses score across sleep restriction days 1–5 (SR1–SR5) (e.g. the lower the average change from baseline score, the more resilient) and using the following six thresholds: (A) ±1 standard deviation (SD) (Res N = 4; Vul N = 7; Int N = 30); (B) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res N = 5; Vul N = 5; Int N = 31); (C) the best and worst performing 20% (Res N = 8; Vul N = 8; Int N = 25); (D) the best and worst performing 25% (Res N = 10; Vul N = 10; Int N = 21); (E) the best and worst performing 33% (Res N = 13; Vul N = 13; Int N = 15); (F) the best and worst performing 50% (Res N = 20; Vul N = 21; all N = 41). All Res groups had significantly better performance than their respective Vul groups at all thresholds and on all study days except for on B2 at the 50% threshold (see Table 2 for detailed daytime performance t-test results). The top and bottom axis labels depict the study design: B2 (1000–2400 h), SR1 (0200 h, 0800–0200 h), SR2–SR4 (0800–0200 h), SR5 (0800–2000 h), Recovery days 1–4 (R1–R4, 1000–2000 h), and total sleep deprivation day (TSD, 2200–2000 h). Light blue lines and light gray lines depict individual PVT lapses profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively; the dark blue and the dark gray line depict averaged PVT lapses profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively. The black dotted line depicts the Int group (except for 50%, for which this line depicts all participants) average PVT lapses profile. Breaks in the lines indicate missing data.

Figure 3.

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) group Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) lapses profiles across the study using six different thresholds within the Variance approach. Res, Vul, and Int groups were determined by intraindividual variance in PVT lapses from all test administrations during sleep restriction days 1–5 (SR1–SR) (e.g. the less variance, the more resilient) and using the following six thresholds: (A) ±1 standard deviation (SD) (Res N = 0; Vul N = 8; Int N = 33); (B) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res N = 5; Vul N = 5; Int N = 31); (C) the best and worst performing 20% (Res N = 8; Vul N = 8; Int N = 25); (D) the best and worst performing 25% (Res N = 10; Vul N = 10; Int N = 21); (E) the best and worst performing 33% (Res N = 13; Vul N = 13; Int N = 15); (F) the best and worst performing 50% (Res N = 20; Vul N = 21; all N = 41). All Res groups had significantly better performance than their respective Vul groups at all thresholds and on all study days (see Table 2 for detailed daytime performance t-test results). The top and bottom axis labels depict the study design: Baseline day 2 (B2, 1000–2400 h), SR1 (0200 h, 0800–0200 h), SR2–SR4 (0800–0200 h), SR5 (0800–2000 h), Recovery days 1–4 (R1–R4, 1000–2000 h), and total sleep deprivation day (TSD, 2200–2000 h). Light blue lines and light gray lines depict individual PVT lapses profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively; the dark blue and the dark gray line depict averaged PVT lapses profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively. There was no Res group for the ±1 SD threshold due to no participants having a z-score >1.0. The black dotted line depicts the Int group (except for 50%, for which this line depicts all participants) average PVT lapses profile. Breaks in the lines indicate missing data.

Comparison of PVT lapses resilient and vulnerable approaches

All Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant when comparing the three approaches within each threshold (p ≤ 0.001; Table 1). Tau-b values ranged from moderate to perfect when comparing the Raw Score and Change from Baseline approaches across the six thresholds (τ b = 0.684–1.000; Table 1). Tau-b values ranged from moderate to strong when comparing the Raw Score and Variance approaches (τ b = 0.588–0.853; Table 1) and the Change from Baseline and Variance approaches (τ b = 0.512–0.881; Table 1) across the six thresholds.

Table 1.

Kendall’s tau-b correlations comparing the categorization of participants into the Resilient, Intermediate, and Vulnerable groups for Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) lapses and PVT response speed (1/RT) based on three approaches+

| PVT lapses | PVT 1/RT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | Approach 1 | Approach 2 | tau-b | p | Threshold | Approach 1 | Approach 2 | tau-b | p |

| ±1 SD * | Raw† | Baseline‡ | 0.912 | <.001 | ±1 SD | Raw | Baseline | 0.418 | 0.015 |

| Raw | Variance§ | 0.588 | <.001 | Raw | Variance | 0.095 | 0.567 | ||

| Baseline | Variance | 0.524 | <.001 | Baseline | Variance | 0.344 | 0.034 | ||

| 12.5% | Raw | Baseline | 0.684 | <.001 | 12.5% | Raw | Baseline | 0.382 | 0.021 |

| Raw | Variance | 0.684 | <.001 | Raw | Variance | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Baseline | Variance | 0.684 | <.001 | Baseline | Variance | 0.093 | 0.567 | ||

| 20% | Raw | Baseline | 1.000 | <.001 | 20% | Raw | Baseline | 0.403 | 0.015 |

| Raw | Variance | 0.791 | <.001 | Raw | Variance | 0.170 | 0.308 | ||

| Baseline | Variance | 0.791 | <.001 | Baseline | Variance | 0.399 | 0.015 | ||

| 25% | Raw | Baseline | 0.940 | <.001 | 25% | Raw | Baseline | 0.502 | 0.007 |

| Raw | Variance | 0.825 | <.001 | Raw | Variance | 0.133 | 0.422 | ||

| Baseline | Variance | 0.881 | <.001 | Baseline | Variance | 0.346 | 0.027 | ||

| 33% | Raw | Baseline | 0.853 | <.001 | 33% | Raw | Baseline | 0.406 | 0.015 |

| Raw | Variance | 0.853 | <.001 | Raw | Variance | 0.168 | 0.308 | ||

| Baseline | Variance | 0.853 | <.001 | Baseline | Variance | 0.472 | 0.007 | ||

| 50% | Raw | Baseline | 0.805 | <.001 | 50% | Raw | Baseline | 0.414 | 0.020 |

| Raw | Variance | 0.610 | <.001 | Raw | Variance | 0.317 | 0.068 | ||

| Baseline | Variance | 0.512 | 0.001 | Baseline | Variance | 0.512 | 0.007 | ||

+Three different approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance) defined Resilient and Vulnerable groups based on sleep restriction performance within each measure. Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficients and Benjamini–Hochberg corrected p-values are presented.

*SD = standard deviation.

†Raw = Raw Score approach.

‡Baseline = Change from Baseline approach.

§Variance = Variance approach.

Comparison of PVT lapses resilient and vulnerable groups by day

The PVT lapses Res group, defined by all three approaches, had significantly fewer PVT lapses than the respective Vul group on all study days at all thresholds (p ≤ 0.001–0.031; Table 2; Figures 1–3), except for by the Change from Baseline approach at the 50% threshold on B2, which was not significant (p = 0.095).

Table 2.

Comparisons of Resilient and Vulnerable group means for Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) lapses and PVT response speed (1/RT) on each study day within each approach+

| PVT lapses | PVT 1/RT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Day | Threshold | Raw Score p-value | Change from Baseline p-value | Variance p-value | Threshold | Raw Score p-value | Change from Baseline p-value | Variance p-value |

| B2 * | ±1 SD ‖ | <.001 | <0.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.552 | <.001 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.005 | 12.5% | <.001 | 0.790 | 0.018 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.547 | 0.305 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | 0.759 | 0.323 | |

| 33% | <.001 | 0.004 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | 0.822 | 0.925 | |

| 50% | <.001 | 0.095 | 0.031 | 50% | <.001 | 0.990 | 0.285 | |

| SR1 † | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.197 | <.001 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | 0.007 | <.001 | 12.5% | <.001 | 0.231 | 0.219 | |

| 20% | 0.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.287 | 0.559 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | 0.042 | 0.504 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | 0.057 | 0.804 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.007 | 50% | <.001 | 0.067 | 0.171 | |

| SR2 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.051 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.002 | 12.5% | <.001 | 0.013 | 0.445 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.010 | 0.819 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.626 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.125 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | 0.007 | 0.008 | |

| SR3 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.002 | 0.908 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.854 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.225 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.157 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.016 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.002 | |

| SR4 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | 0.908 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.008 | 12.5% | <.001 | 0.006 | 0.770 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.076 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.008 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.004 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| SR5 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | 0.275 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.044 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.027 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.005 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| R1 ‡ | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.005 | 0.185 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.908 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.007 | 0.790 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.824 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.323 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.005 | 50% | <.001 | 0.007 | 0.023 | |

| R2 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.002 | 0.077 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.366 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.952 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.939 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.359 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.003 | 50% | <.001 | 0.011 | 0.021 | |

| R3 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.001 | 0.079 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.487 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.790 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.749 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.178 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | 0.008 | 0.002 | |

| R4 | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | 0.008 | 0.052 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | <.001 | 0.001 | 0.362 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | 0.006 | 0.782 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | 0.001 | <.001 | 0.754 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.134 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | 0.013 | 0.007 | |

| TSD § | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | – | ±1 SD | <.001 | <.001 | 0.630 |

| 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 12.5% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.454 | |

| 20% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 20% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.019 | |

| 25% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 25% | 0.001 | <.001 | 0.001 | |

| 33% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 33% | <.001 | <.001 | 0.001 | |

| 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 50% | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

+Three different approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance) defined Resilient and Vulnerable groups based on sleep restriction performance within each measure. Bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapped t-test p-values are presented. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons was applied to all p-values. Analyses were not conducted for the Variance approach for PVT 1/RT at the ±1 SD threshold due to the absence of a Resilient group.

*B2 = Baseline day 2.

†SR = Sleep restriction day.

‡R = Recovery day.

§TSD = Total sleep deprivation day.

‖SD = standard deviation.

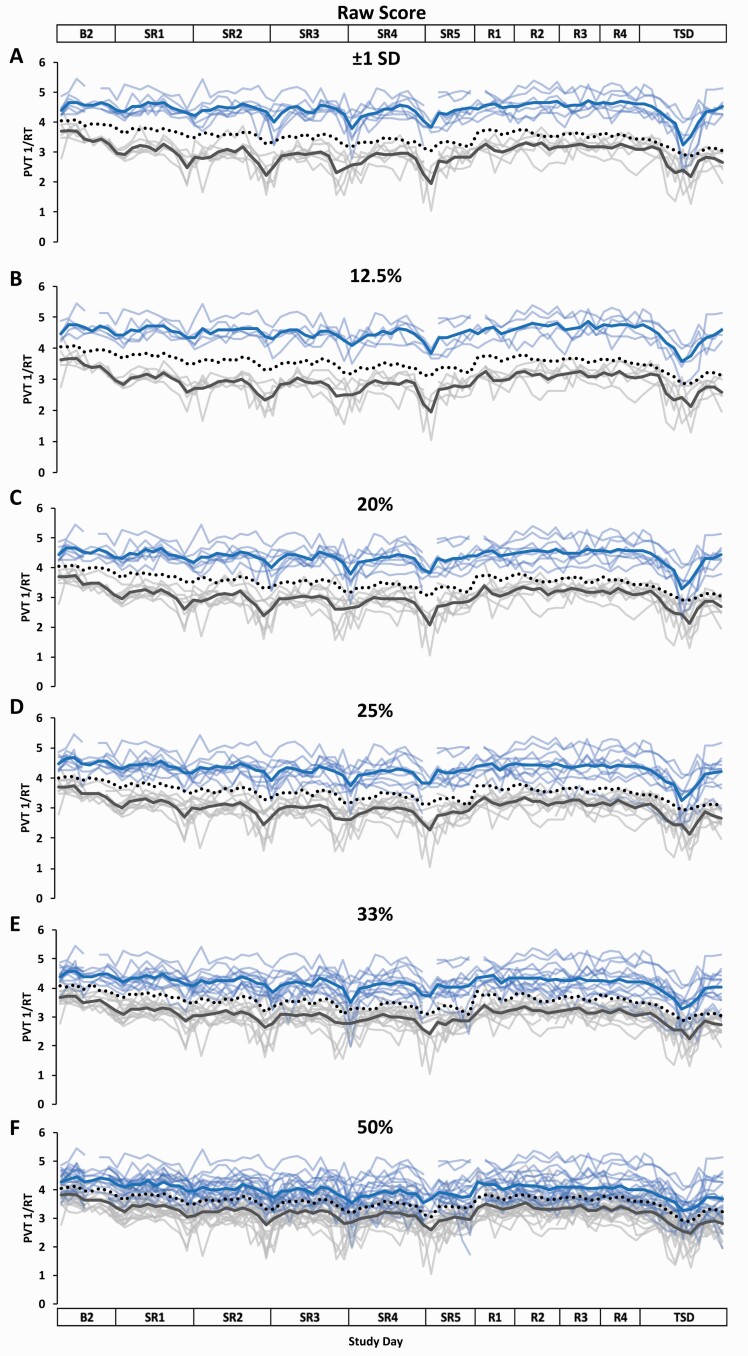

PVT 1/RT

Participants were grouped into Res, Vul, and Int groups by all three approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance) at all thresholds. For all three approaches at all thresholds, the PVT 1/RT Res groups had significantly faster average PVT 1/RT across SR1-SR5 than the Vul groups (p ≤ 0.001–0.013), except for the Variance approach at the ±1 SD, 12.5%, 20%, and 25% thresholds, which were not significantly different across SR1–SR5 (p = 0.206–0.793). The PVT 1/RT profiles of the Res, Vul, and Int groups, defined by the Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance approaches at the six thresholds are depicted in Figures 4–6, respectively (Supplementary Table S2 shows each individual’s groupings [Res, Vul, or Int group] for each approach at each threshold).

Figure 4.

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) group Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) response speed (1/RT) profiles across the study using six different thresholds within the Raw Score approach. Res, Vul, and Int groups were determined by averaging PVT 1/RT from all test administrations during sleep restriction days 1–5 (SR1–SR5) (e.g. the greater PVT 1/RT, the more resilient) and using the following six thresholds: (A) ±1 standard deviation (SD) (Res N = 7; Vul N = 6; Int N = 28); (B) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res N = 5; Vul N = 5; Int N = 31); (C) the best and worst performing 20% (Res N = 8; Vul N = 8; Int N = 25); (D) the best and worst performing 25% (Res N = 10; Vul N = 10; Int N = 21); (E) the best and worst performing 33% (Res N = 13; Vul N = 13; Int N = 15); (F) the best and worst performing 50% (Res N = 20; Vul N = 21; all N = 41). All Res groups had significantly better performance than their respective Vul groups at all thresholds and on all study days (see Table 2 for detailed daytime performance t-test results). The top and bottom axis labels depict the study design: Baseline day 2 (B2, 1000–2400 h), SR1 (0200 h, 0800–0200 h), SR2–SR4 (0800–0200 h), SR5 (0800–2000 h), Recovery days 1–4 (R1–R4, 1000–2000 h), and total sleep deprivation day (TSD, 2200–2000 h). Light blue lines and light gray lines depict individual PVT 1/RT profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively; the dark blue and the dark gray line depict group averaged PVT 1/RT profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively. The black dotted line depicts the Int group (except for 50%, for which this line depicts all participants) average PVT 1/RT profile. Breaks in the lines indicate missing data.

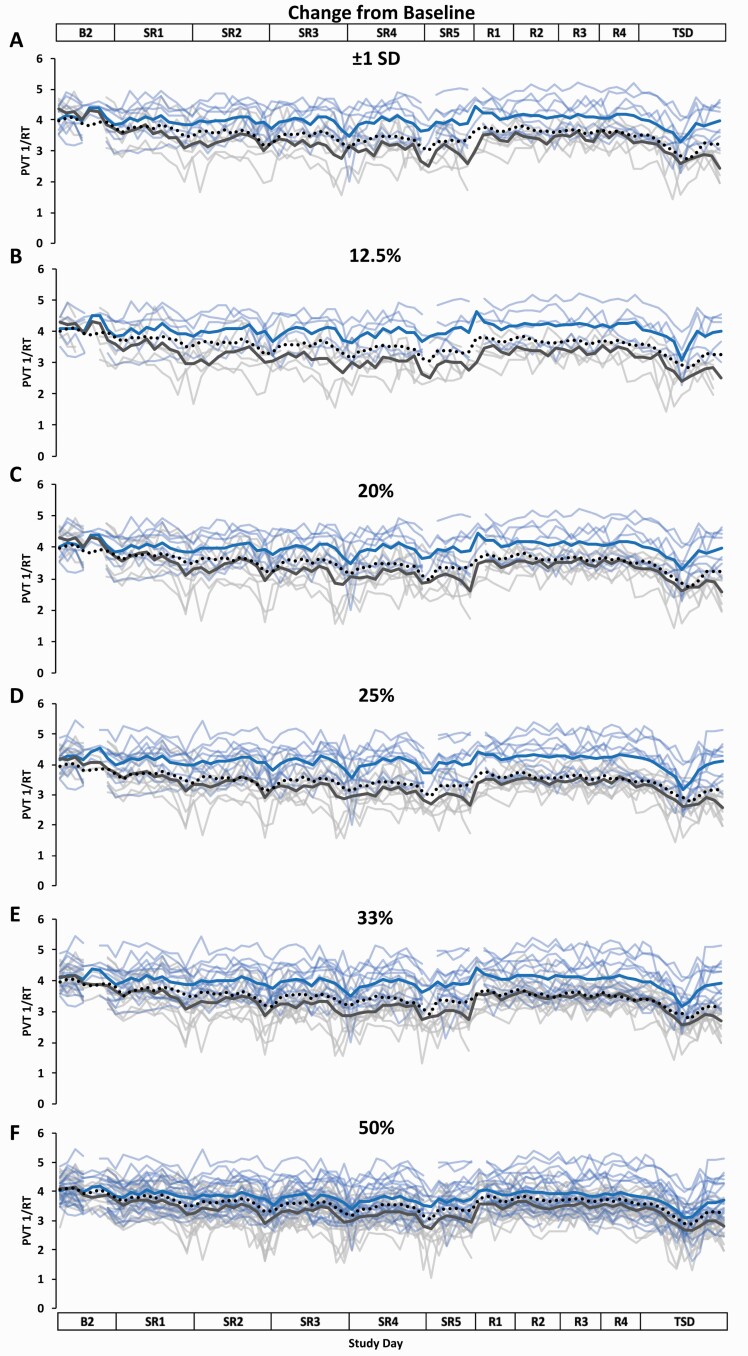

Figure 5.

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) group Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) response speed (1/RT) profiles across the study using six different thresholds within the Change from Baseline approach. Res, Vul, Int groups were determined by subtracting each participant’s mean PVT 1/RT score across baseline day (B2) from their mean PVT 1/RT score across sleep restriction days 1–5 (SR1–SR5) (e.g. the greater the average change from baseline score, the more resilient) and using the following six thresholds: (A) ±1 standard deviation (SD) (Res N = 8; Vul N = 6; Int N = 28); (B) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res N = 5; Vul N = 5; Int N = 31); (C) the best and worst performing 20% (Res N = 8; Vul N = 8; Int N = 25); (D) the best and worst performing 25% (Res N = 10; Vul N = 10; Int N = 21); (E) the best and worst performing 33% (Res N = 13; Vul N = 13; Int N = 15); (F) the best and worst performing 50% (Res N = 20; Vul N = 21; all N = 41). All Res groups had significantly better performance than their respective Vul groups at all thresholds and on all study days except for on B2 at all thresholds and on SR1 at the ±1 SD, 12.5%, 20%, 33%, and 50% thresholds (see Table 2 for detailed daytime performance t-test results). The top and bottom axis labels depict the study design: B2 (1000–2400 h), SR1 (0200 h, 0800–0200 h), SR2–SR4 (0800–0200 h), SR5 (0800–2000 h), Recovery days 1–4 (R1–R4, 1000–2000 h), and total sleep deprivation day (TSD, 2200–2000 h). Light blue lines and light gray lines depict individual PVT 1/RT profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively; the dark blue and the dark gray line depict averaged PVT 1/RT profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively. The black dotted line depicts the Int group (except for 50%, for which this line depicts all participants) average PVT 1/RT profile. Breaks in the lines indicate missing data.

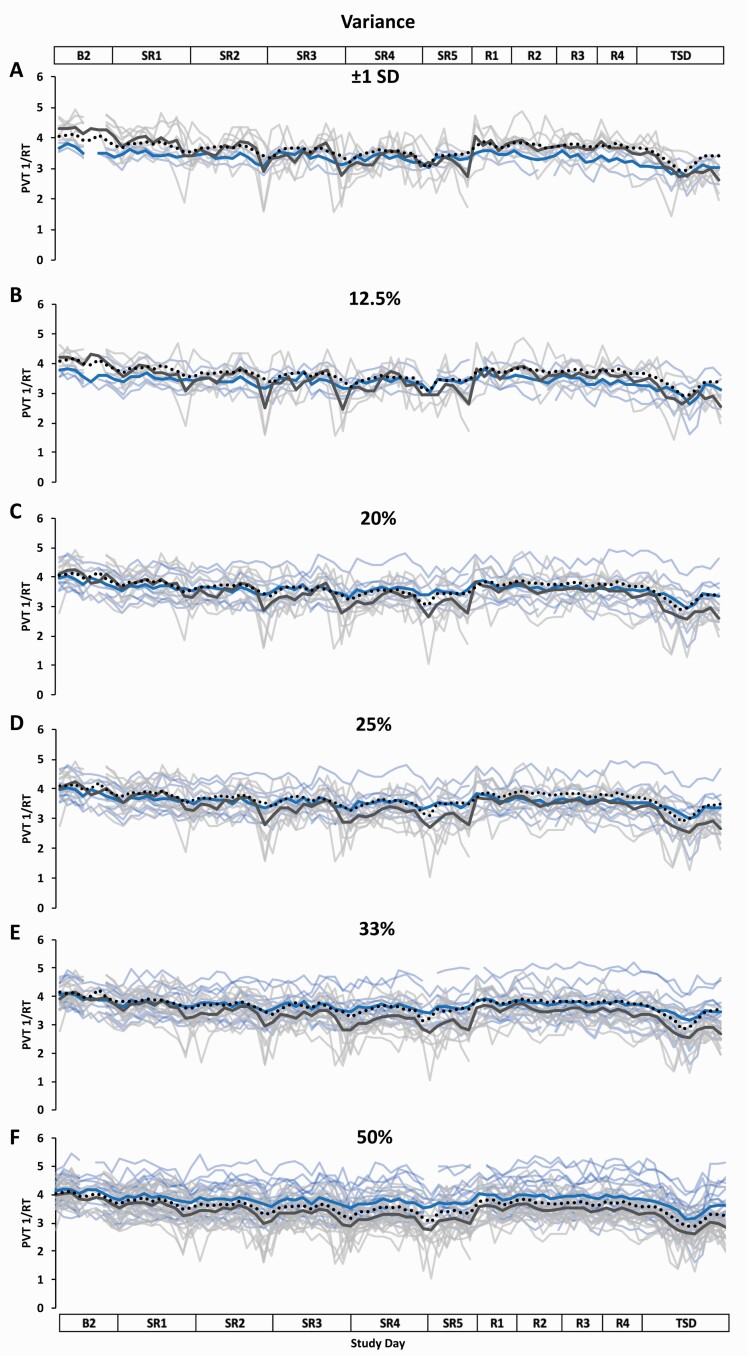

Figure 6.

Resilient (Res), Vulnerable (Vul), and Intermediate (Int) group Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) response speed (1/RT) profiles across the study using six different thresholds within the Variance approach. Res, Vul, and Int groups were determined by intraindividual variance in PVT 1/RT from all test administrations during sleep restriction days 1–5 (SR1–SR5) (e.g. the less variance, the more resilient) and using the following six thresholds: (A) ±1 standard deviation (SD) (Res N = 3; Vul N = 7; Int N = 31); (B) the best and worst performing 12.5% (Res N = 5; Vul N = 5; Int N = 31); (C) the best and worst performing 20% (Res N = 8; Vul N = 8; Int N = 25); (D) the best and worst performing 25% (Res N = 10; Vul N = 10; Int N = 21); (E) the best and worst performing 33% (Res N = 13; Vul N = 13; Int N = 15); (F) the best and worst performing 50% (Res N = 20; Vul N = 21; all N = 41). Results from t-tests comparing daytime performance varied based on study day and threshold (see Table 2 for detailed daytime performance t-test results). The top and bottom axis labels depict the study design: Baseline day 2 (B2, 1000–2400 h), SR1 (0200 h, 0800–0200 h), SR2–SR4 (0800–0200 h), SR5 (0800–2000 h), Recovery days 1–4 (R1–R4, 1000–2000 h), and total sleep deprivation day (TSD, 2200–2000 h). Light blue lines and light gray lines depict individual PVT 1/RT profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively; the dark blue and the dark gray line depict averaged PVT 1/RT profiles for the Res and Vul groups, respectively. The black dotted line depicts the Int group (except for 50%, for which this line depicts all participants) average PVT 1/RT profile. Breaks in the lines indicate missing data.

Comparison of PVT 1/RT resilient and vulnerable approaches

All Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant comparing the Raw Score and Change from Baseline approaches within each threshold and tau-b values ranged from weak to moderate (τ b = 0.382–0.502; p = 0.007–0.021; Table 1). Kendall’s tau-b correlations comparing the Raw Score and Variance approaches were not significant at any threshold (τ b = 0.000–0.317, p = 0.068–1.000; Table 1). Kendall’s tau-b correlations comparing the Change from Baseline and Variance approaches were all significant at all thresholds and ranged from weak to moderate (τ b = 0.344–0.512; p = 0.007–0.034; Table 1), except at the 12.5% threshold, which was not significant (τ b = 0.093, p = 0.567).

Comparison of PVT 1/RT resilient and vulnerable groups by day

The PVT 1/RT Res group, defined by the Raw Score approach, had significantly faster PVT 1/RT than the Vul group on all study days at all thresholds (p ≤ 0.001; Table 2; Figure 4). The Res group, defined by the Change from Baseline approach, had significantly faster PVT 1/RT than the Vul group on SR1 at the 25% threshold and on all subsequent study days (SR2-TSD) at all thresholds (p ≤ 0.001–0.042; Table 2; Figure 5); comparisons at B2 and at other thresholds on SR1 were not significant (p = 0.057–0.990). The Res group, defined by the Variance approach, had significantly faster PVT 1/RT than the Vul group on SR2 (50% threshold), SR3 (33% and 50% thresholds), SR4 (25%, 33%, and 50% thresholds), SR5 (12.5%, 20%, 25%, 33%, and 50% thresholds), R1–R4 (50% threshold), and TSD (20%, 25%, 33%, and 50% thresholds) (p ≤ 0.001–0.044; Table 2; Figure 6). The Res group had significantly slower PVT 1/RT than the Vul group on B2 (±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds) and on SR1 (±1 SD threshold) (p ≤ 0.001–0.018; Table 2; Figure 6); no other comparisons were significant (p = 0.051–0.952).

Comparison of PVT lapses and PVT 1/RT resilient and vulnerable approaches

When compared at the same threshold, Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant for all comparisons between the PVT 1/RT Raw Score approach and all three approaches for PVT lapses, and the tau-b values ranged from moderate to strong (τ b = 0.44–0.79; p ≤ 0.001–0.006; Table 3), with the exception of the comparison of the PVT 1/RT Raw Score approach at the 50% threshold and the PVT lapses Variance approach at the 50% threshold, which was not significant (τ b = 0.32, p = 0.051).

Table 3.

Kendall’s tau-b correlations comparing the categorization of participants into the Resilient, Intermediate, and Vulnerable groups as defined by the three approaches+ between Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) lapses and PVT response speed (1/RT)

| PVT lapses | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Score | Change from Baseline | Variance | ||||||||||||||||||

| Threshold | ±1 SD | 12.5% | 20% | 25% | 33% | 50% | ±1 SD | 12.5% | 20% | 25% | 33% | 50% | ±1 SD | 12.5% | 20% | 25% | 33% | 50% | ||

| PVT 1/RT | Raw Score | ±1 SD † | 0.76 * | 0.77* | 0.74* | 0.72* | 0.68* | 0.54* | 0.75 * | 0.68* | 0.74* | 0.65* | 0.62* | 0.54* | 0.44 * | 0.59* | 0.53* | 0.59* | 0.62* | 0.46* |

| 12.5% | 0.78* | 0.79 * | 0.77* | 0.68* | 0.59* | 0.48* | 0.75* | 0.68 * | 0.77* | 0.68* | 0.59* | 0.48* | 0.36* | 0.58 * | 0.53* | 0.61* | 0.59* | 0.48* | ||

| 20% | 0.75* | 0.69* | 0.79 * | 0.76* | 0.70* | 0.60* | 0.74* | 0.61* | 0.79 * | 0.69* | 0.65* | 0.60* | 0.47* | 0.61* | 0.59 * | 0.64* | 0.65* | 0.45* | ||

| 25% | 0.72* | 0.68* | 0.76* | 0.77 * | 0.67* | 0.53* | 0.65* | 0.54* | 0.76* | 0.71 * | 0.65* | 0.66* | 0.42* | 0.53* | 0.58* | 0.61 * | 0.65* | 0.40* | ||

| 33% | 0.62* | 0.59* | 0.70* | 0.70* | 0.60 * | 0.64* | 0.56* | 0.52* | 0.70* | 0.65* | 0.58 * | 0.64* | 0.36* | 0.46* | 0.54* | 0.56* | 0.58 * | 0.35* | ||

| 50% | 0.55* | 0.48* | 0.60* | 0.66* | 0.58* | 0.71 * | 0.51* | 0.48* | 0.60* | 0.60* | 0.52* | 0.71 * | 0.36* | 0.38* | 0.52* | 0.53* | 0.58* | 0.32 | ||

| Change from Baseline | ±1 SD | 0.29 | 0.32* | 0.31* | 0.38* | 0.48* | 0.57* | 0.32 * | 0.32* | 0.31* | 0.38* | 0.48* | 0.57* | 0.24 | 0.32* | 0.31* | 0.38* | 0.48* | 0.32* | |

| 12.5% | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.33* | 0.40* | 0.48* | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.33* | 0.40* | 0.48* | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.40* | 0.29 | ||

| 20% | 0.32* | 0.37* | 0.34 * | 0.41* | 0.49* | 0.52* | 0.36* | 0.37* | 0.34 * | 0.41* | 0.49* | 0.60* | 0.28 | 0.37* | 0.34 * | 0.41* | 0.49* | 0.37* | ||

| 25% | 0.40* | 0.40* | 0.41* | 0.55 * | 0.60* | 0.60* | 0.44* | 0.40* | 0.41* | 0.50 * | 0.60* | 0.66* | 0.33* | 0.40* | 0.41* | 0.45 * | 0.60* | 0.46* | ||

| 33% | 0.45* | 0.34* | 0.49* | 0.60* | 0.63 * | 0.64* | 0.50* | 0.52* | 0.49* | 0.60* | 0.71 * | 0.75* | 0.44* | 0.40* | 0.49* | 0.56* | 0.67 * | 0.52* | ||

| 50% | 0.47* | 0.38* | 0.45* | 0.53* | 0.64* | 0.71 * | 0.51* | 0.48* | 0.45* | 0.53* | 0.64* | 0.71 * | 0.48* | 0.38* | 0.45* | 0.53* | 0.64* | 0.51 * | ||

| Variance | ±1 SD | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.35* | 0.39* | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.33* | 0.41* | 0.40* | 0.41 * | 0.30 | 0.38* | 0.48* | 0.47* | 0.49* | |

| 12.5% | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.33* | 0.34* | 0.38* | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.40* | 0.40* | 0.29 | 0.48* | 0.28 | 0.45* | 0.53* | 0.46* | 0.48* | ||

| 20% | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.34 * | 0.41* | 0.44* | 0.37* | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.34 * | 0.46* | 0.49* | 0.37* | 0.47* | 0.45* | 0.53 * | 0.58* | 0.54* | 0.60* | ||

| 25% | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.35* | 0.40 * | 0.47* | 0.40* | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.35* | 0.45 * | 0.56* | 0.40* | 0.50* | 0.39* | 0.52* | 0.55 * | 0.51* | 0.66* | ||

| 33% | 0.40* | 0.34* | 0.44* | 0.47* | 0.50 * | 0.46* | 0.33* | 0.34* | 0.44* | 0.51* | 0.58 * | 0.46* | 0.44* | 0.40* | 0.54* | 0.56* | 0.58 * | 0.75* | ||

| 50% | 0.55* | 0.48* | 0.60* | 0.66* | 0.69* | 0.61 * | 0.51* | 0.48* | 0.60* | 0.66* | 0.75* | 0.51 * | 0.48* | 0.48* | 0.60* | 0.66* | 0.75* | 1.00 * | ||

+Three different approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance) defined Resilient and Vulnerable groups based on sleep restriction performance within each measure. Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficients are presented. Bolded tau-b values indicate comparisons of the same thresholds.

†SD = standard deviation.

*p < .05. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction was applied to all p-values.

When compared at the same threshold, Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant for all comparisons between the PVT 1/RT Change from Baseline approach and both the PVT lapses Raw Score and PVT lapses Change from Baseline approaches and ranged from weak to strong (τ b = 0.32–0.71; p ≤ 0.001–0.036; Table 3), with the exception of the comparisons at the ±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds for the PVT 1/RT Change from Baseline and PVT lapses Raw Score approaches, as well as at the 12.5% threshold for the PVT 1/RT and PVT lapses Change from Baseline approaches, which were not significant (τ b = 0.28–0.29, p = 0.054–0.063). When compared at the same threshold, Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant for all comparisons between the PVT 1/RT Change from Baseline and PVT lapses Variance approaches and ranged from weak to moderate (τ b = 0.34–0.67; p ≤ 0.001–0.022; Table 3), with the exception of the comparisons at the ±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds, which were not significant (τ b = 0.19–0.24; p = 0.114–0.215). See Table 3 for tau-b values between the PVT 1/RT Change from Baseline approach categorization compared with the PVT lapses categorizations across all approaches and thresholds.

When compared at the same threshold, Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant for all comparisons between the PVT 1/RT Variance and PVT lapses Raw Score approaches and ranged from weak to moderate (τ b = 0.34–0.61; p ≤ 0.001–0.022; Table 3), with the exception of the comparisons at the ±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds, which were not significant (τ b = 0.09–0.15, p = 0.326–0.535). When compared at the same threshold, Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant for all comparisons between the PVT 1/RT Variance and PVT lapses Change from Baseline approaches and ranged from weak to moderate (τ b = 0.34–0.58; p ≤ 0.001–0.022; Table 3), with the exception of the comparisons at the ±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds, which were not significant (τ b = 0.16–0.28, p = 0.063–0.284). When compared at the same threshold, Kendall’s tau-b correlations were significant for all comparisons between the PVT 1/RT Variance and PVT lapses Variance approaches and ranged from weak to perfect (τ b = 0.41–1.00; p ≤ 0.001–0.011; Table 3), with the exception of the comparison at the 12.5% threshold, which was not significant (τ b = 0.28, p = 0.068). See Table 3 for tau-b values between the PVT 1/RT Variance approach categorization compared with the PVT lapses categorization across all approaches and thresholds.

Discussion

For the first time, we comprehensively compared three different approaches (Raw Score, Change from Baseline, and Variance) and six different thresholds for categorizing individuals as resilient or vulnerable based on PVT performance during chronic SR. For PVT lapses, but not for PVT 1/RT, we found that within each discrete threshold, the categorization of participants by the three approaches were significantly concordant. Moreover, the Raw Score approach groupings for PVT 1/RT were similar to all three approaches for PVT lapses. Defined by all three approaches and at all thresholds, the lapses Res groups had fewer lapses on nearly all study days compared to the respective Vul groups. When defined by the Raw Score approach only, the 1/RT Res groups had significantly faster response speed on all study days at all thresholds compared to the respective Vul groups.

For PVT lapses, the three approaches were significantly correlated at each discrete threshold for categorizing participants into Res, Vul, and Int groups, with all comparisons showing moderate to strong correlations. Thus, those who had fewer lapses during SR also generally showed less or no impairment of performance during SR relative to baseline, and generally less variable performance throughout SR. These results concur with previous studies without a sleep loss component, which found that mean performance and intraindividual variability of performance were positively associated [21, 22, 29, 56, 57]. For PVT 1/RT, the groups formed by the Raw Score and Variance approaches were not significantly related at any threshold but were significant for all comparisons between the Raw Score and Change from Baseline approaches and for all but one comparison between the Change from Baseline and Variance approaches. The non-significant, zero to weak strength relationships between the Raw Score and Variance approaches for PVT 1/RT suggest that those who had faster 1/RT during SR did not necessarily show less within-subject variance and those who had slower 1/RT did not necessarily show greater within-subject variance. The lack of concordance between these two approaches may be due to individual differences in factors related to time-of-day fluctuations in performance, such as chronotype and circadian period [27, 58, 59], which our Variance approach may have partially captured. Perhaps these factors influenced the consistency of PVT 1/RT across sleep loss; this possibility should be further explored. Additionally, since performance consistency has been posited as a reason underlying individual differences [25], yet has been unexplored explicitly until the present study, the Variance approach should be further investigated as a tool for understanding individual differences in PVT performance across periods of sleep loss.

A more granular examination of the groupings of individuals for each PVT metric in Supplementary Table S2 shows that individuals did not change from Res to Vul or vice versa within an approach and across thresholds; however, individuals did change from Res to Vul or vice versa within a threshold across approaches. Upon closer inspection, this change occurred almost exclusively at the less restrictive 33% and 50% thresholds (except for two individuals, one person at both the 20% and 25% thresholds, and one person at the 25% threshold). As such, the 33% and 50% thresholds may be less informative when investigating differences within a PVT metric, though future examination is required, including studies using larger sample sizes, to determine if this remains true. Additionally, the absence of a ±1 SD threshold Res group may indicate that this threshold is not as useful compared to other thresholds.

When evaluating the concordance of the categorizations between PVT 1/RT and PVT lapses at the same threshold, for all but one comparison, the Raw Score approach for PVT 1/RT and all three approaches for PVT lapses were significantly related, with most comparisons ranging from moderate to strong. These results further support that, for PVT lapses, individuals were grouped into Res, Vul, and Int groups in a similar manner for all three approaches. When the Change from Baseline and Variance approaches for PVT 1/RT were compared to all three approaches for PVT lapses at the same thresholds, the strongest correlations were found when the groups were formed using less restrictive thresholds (e.g. 33% and 50% thresholds), rather than using more restrictive thresholds (e.g. ±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds). Thus, individuals who were very resilient to the effects of chronic SR using PVT 1/RT, according to the Change from Baseline and Variance approaches, were not necessarily very resilient using PVT lapses; similarly, those who were very vulnerable using PVT 1/RT (by the Change from Baseline and Variance approaches) were not necessarily very vulnerable using PVT lapses. However, this pattern was not observed for comparisons between the Raw Score approach for PVT 1/RT and all three approaches for PVT lapses. Our results clearly underscore that when analyzing individual differences on the PVT, both the method and outcome metric used to define resiliency and vulnerability should be selected carefully and with significant consideration.

When comparing performance using PVT lapses between Res and Vul groups, on all study days, for all three approaches, and at all thresholds (with one exception: on B2, by Change from Baseline approach, at the 50% threshold), the Res group had significantly fewer lapses than the Vul group. The significant differences in performance during TSD were expected since they also occurred during SR and because of the robust and stable interindividual neurobehavioral differences observed from exposure to both chronic SR and TSD paradigms [8, 60]. Further, the robust and trait-like performance degradation observed during SR and TSD [8, 60] suggests that similar results would be found if TSD PVT performance was used to group individuals as Res, Vul, or Int utilizing the three approaches in the current study. In addition, although we did not explicitly evaluate whether PVT performance returned to baseline or whether the recovery profiles of Res and Vul groups were similar, we show for the first time that the Res group performed significantly better than the Vul group during baseline and on all four recovery days, for all three approaches at all thresholds.

The patterns of performance differences between Res and Vul groups for PVT 1/RT were less uniform. For the Raw Score approach, all Res groups had significantly faster 1/RT on all study days compared to the respective Vul groups, including on B2 and on R1–R4. As with PVT lapses, the differences in performance during both SR and TSD were expected given the trait-like individual differences in performance [8, 60]; however, this is the first demonstration that the robust differences in PVT 1/RT between Res and Vul groups during SR persist throughout four consecutive days of recovery. Our result is in line with a previous study that found a lack of acute recovery in vigilant attention after sleep loss in those individuals who were vulnerable to alcohol intake compared with those individuals who were resilient [61]. Performance comparisons between the Change from Baseline Res and Vul groups, and between the Variance Res and Vul groups, were dependent on the study day and threshold evaluated. Unexpectedly, the Variance approach Vul group had significantly faster 1/RT than the Res group on B2 (±1 SD and 12.5% thresholds) and on SR1 (±1 SD threshold), meaning that those who showed the most intraindividual variance of 1/RT during SR had significantly better performance at B2 and SR1. This finding may partially be due to missing data for the B2 2000 h test bout for the Res and Vul groups (one out of five test bouts included in the B2 average). However, there were no missing data for SR1; thus, the stability of response speed during SR may be unrelated to how one performs while well-rested before sleep loss or during mild acute sleep loss (e.g. one night of 4h TIB).

Our study has a few limitations. First, the approaches and thresholds we used in our study are not an exhaustive list of methods to define and evaluate individual differences in PVT performance during sleep loss. Also, although lapses and 1/RT are the two most used and sensitive metrics to sleep loss derived from the 10-min PVT [62], our results are not generalizable to other PVT metrics, which should be studied in the future. Our results are also not generalizable to adolescents or to older adults, individuals with mood, sleep, or other medical disorders, or other individuals that were not represented in our sample.

Overall, our study showed that resilience and vulnerability to vigilant attention during sleep loss is complex, and that different approaches to define resilience and different thresholds yield Res and Vul groups comprised of different individuals. Use of the Variance approach is likely to result in different individuals in Res and Vul groups compared to use of the Raw Score or Change from Baseline approaches for evaluating performance differences using PVT 1/RT during sleep loss. As such, results derived from using the Variance approach would not be generalizable to results derived from using the Raw Score or Change from Baseline approaches to investigate PVT 1/RT performance differences during sleep loss. However, our study indicates that all three approaches are comparable for PVT lapses.

Our results have implications for biomarker and countermeasure research related to individual differences in vigilant attention during sleep loss given prior studies evaluating whether neural, genetic, or physiological biomarkers can identify resiliency to sleep loss [12, 18, 34, 63, 64] and those evaluating how napping or pharmacological countermeasures differentially improve performance [9, 65]. These studies have employed varied approaches to evaluate resiliency to sleep loss. However, our results suggest that future studies may need to be targeted towards specific definitions of resiliency to sleep loss. Additionally, individual differences to sleep loss have real-world implications for future adverse health outcomes [66], as well as for work and public safety [67–69]. For example, based on our findings, a pilot who shows a fast average response speed on a behavioral attention task during sleep loss (resilient with the Raw Score approach), will generally also be categorized as resilient even when considering their average baseline performance (resilient with the Change from Baseline approach). However, the same may not be true for a pilot who shows a slow average response speed during sleep loss as being categorized as vulnerable when their baseline performance is considered, since a slow response speed under both conditions would indicate resilience by the Change from Baseline approach. Furthermore, a pilot who shows highly stable behavioral attention performance across time regardless of performance scores (resilient with the Variance approach), or one who shows highly unstable performance across time (vulnerable with the Variance approach), will show little to no relationship regarding categorization using the other two approaches, suggesting stability of performance represents a different type of vulnerability. Lastly, it is important to consider a possible “ceiling effect” (participants may have consistently shown a very high number of PVT lapses or extremely slow response speeds due to “ceiling” performance), and how this might impact the determination of resilience and vulnerability using the Variance approach. While we did not directly assess this concept, and our sample notably was not performing “at the ceiling” for either PVT lapses or response speed, it is possible the Variance approach might more poorly capture these potential effects, since it evaluates fluctuations in scores rather than raw scores. Therefore, future studies should examine resilience and vulnerability on behavioral attention tasks using clear, specific definitions since the methods to define these groups have far-reaching implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the faculty and staff of the Unit of Experimental Psychiatry for their contributions to this study in terms of data collection. N.G. designed the overall study and provided financial support. E.Y. conducted statistical analyses of the data, E.Y., T.B., C.C., C.A., and N.G. prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was primarily supported by the Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Research (Award No. N00014-11-1-0361) to N.G. Other support provided by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) grant NNX14AN49G and grant 80NSSC20K0243 (to N.G.), National Institutes of Health grant NIH R01DK117488 (to N.G.) and Clinical and Translational Research Center grant UL1TR000003. None of the sponsors had any role in the following: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

Financial Disclosure: None.

Non-financial Disclosure: None.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Belenky G, et al. Patterns of performance degradation and restoration during sleep restriction and subsequent recovery: a sleep dose-response study. J Sleep Res. 2003;12(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goel N. Neurobehavioral effects and biomarkers of sleep loss in healthy adults. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(11):89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goel N, et al. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin Neurol. 2009;29(4):320–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamazaki EM, et al. Residual, differential neurobehavioral deficits linger after multiple recovery night following chronic sleep restriction or acute total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2021;44(4):zsaa224. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dennis LE, et al. Healthy Adults display long-term trait-like neurobehavioral resilience and vulnerability to sleep loss. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Dongen HP, et al. Dealing with inter-individual differences in the temporal dynamics of fatigue and performance: importance and techniques. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75(3 Suppl):A147–A154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Dongen HP, et al. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003;26(2):117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamazaki EM, et al. Robust stability of trait-like vulnerability or resilience to common types of sleep deprivation in a large sample of adults. Sleep. 2020;43(6):zsz292. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caldwell JL, et al. Differential effects of modafinil on performance of low-performing and high-performing individuals during total sleep deprivation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2020;196:172968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chua EC, et al. Classifying attentional vulnerability to total sleep deprivation using baseline features of Psychomotor Vigilance Test performance. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chua EC, et al. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation associates with instability in behavior and physiologic measures at baseline. Sleep. 2014;37(1):27–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moreno-Villanueva M, et al. The degree of radiation-induced DNA strand breaks is altered by acute sleep deprivation and psychological stress and is associated with cognitive performance in humans. Sleep. 2018;41(7):zsy067. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patanaik A, et al. Classifying vulnerability to sleep deprivation using baseline measures of psychomotor vigilance. Sleep. 2015;38(5):723–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chee MWL, et al. Functional imaging of working memory following normal sleep and after 24 and 35 h of sleep deprivation: Correlations of fronto-parietal activation with performance. Neuroimage. 2006;31(1):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chee MW, et al. Lapsing when sleep deprived: neural activation characteristics of resistant and vulnerable individuals. Neuroimage. 2010;51(2):835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chuah LY, et al. Donepezil improves episodic memory in young individuals vulnerable to the effects of sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2009;32(8):999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kong D, et al. Increased automaticity and altered temporal preparation following sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1219–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patanaik A, et al. Predicting vulnerability to sleep deprivation using diffusion model parameters. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(5):576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riontino L, et al. Individual differences in working memory efficiency modulate proactive interference after sleep deprivation. Psychol Res. 2021;85(2):480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu J, et al. Frontal metabolic activity contributes to individual differences in vulnerability toward total sleep deprivation-induced changes in cognitive function. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(2):169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allaire JC, et al. Intraindividual variability may not always indicate vulnerability in elders’ cognitive performance. Psychol Aging. 2005;20(3):390–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hultsch DF, et al. Intraindividual variability in cognitive performance in older adults: comparison of adults with mild dementia, adults with arthritis, and healthy adults. Neuropsychology. 2000;14(4):588–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. West R, et al. Lapses of intention and performance variability reveal age-related increases in fluctuations of executive control. Brain Cogn. 2002;49(3):402–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Banks S, et al. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):519–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doran SM, et al. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation: evidence of state instability. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139(3):253–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adam M, et al. Age-related changes in the time course of vigilant attention during 40 hours without sleep in men. Sleep. 2006;29(1):55–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blatter K, et al. Circadian rhythms in cognitive performance: methodological constraints, protocols, theoretical underpinnings. Physiol Behav. 2007;90(2-3):196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmidt C, et al. A time to think: circadian rhythms in human cognition. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2007;24(7):755–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rabbitt P, et al. There are stable individual differences in performance variability, both from moment to moment and from day to day. Q J Exp Psychol A. 2001;54(4):981–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diekelmann S, et al. Sleep enhances false memories depending on general memory performance. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208(2):425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Michael L, et al. Electrodermal lability as an indicator for subjective sleepiness during total sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(4):470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rocklage M, et al. White matter differences predict cognitive vulnerability to sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2009;32(8):1100–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salfi F, et al. Effects of total and partial sleep deprivation on reflection impulsivity and risk-taking in deliberative decision-making. Nat Sci Sleep. 2020;12:309–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yeo BT, et al. Functional connectivity during rested wakefulness predicts vulnerability to sleep deprivation. Neuroimage. 2015;111:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Galli O. Predictors of Interindividual Differences in Vulnerability to Neurobehavioral Consequences of Chronic Partial Sleep Restriction [doctoral dissertation]. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. St Hilaire MA, et al. Using a single daytime performance test to identify most individuals at high-risk for performance impairment during extended wake. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Frey DJ, et al. Inter- and intra-individual variability in performance near the circadian nadir during sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 2004;13(4):305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hudson AN, et al. Sleep deprivation, vigilant attention, and brain function: a review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(1):21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Axelsson J, et al. Sleepiness and performance in response to repeated sleep restriction and subsequent recovery during semi-laboratory conditions. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25(2–3):297–308. doi: 10.1080/07420520802107031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Banks S, et al. Neurobehavioral dynamics following chronic sleep restriction: dose-response effects of one night for recovery. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1013–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Honn KA, et al. New insights into the cognitive effects of sleep deprivation by decomposition of a cognitive throughput task. Sleep. 2020;43(7):zsz319. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lamond N, et al. The dynamics of neurobehavioural recovery following sleep loss. J Sleep Res. 2007;16(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Philip P, et al. Acute versus chronic partial sleep deprivation in middle-aged people: differential effect on performance and sleepiness. Sleep. 2012;35(7):997–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McCauley P, et al. A new mathematical model for the homeostatic effects of sleep loss on neurobehavioral performance. J Theor Biol. 2009;256(2):227–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pejovic S, et al. Effects of recovery sleep after one work week of mild sleep restriction on interleukin-6 and cortisol secretion and daytime sleepiness and performance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(7):E890–E896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rupp TL, et al. Banking sleep: realization of benefits during subsequent sleep restriction and recovery. Sleep. 2009;32(3):311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dinges DF, et al. Microcomputer analyses of performance on a portable, simple visual RT task during sustained operations. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 1985;17:652–655. [Google Scholar]

- 48. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2020. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kassambara A. rstatix: Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. R package version 0.6.0. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kendall MG, Gibbons JD.. Rank Correlation Methods. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dodge Y. The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dancey CP, et al. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology. 4th ed. Essex, England: Pearson Education Limited; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiss NA. wBoot: Bootstrap Methods. R package version 1.0.3. 2016. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=wBoot. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mantua J, et al. Self-reported sleep need, subjective resilience, and cognitive performance following sleep loss and recovery sleep. Psychol Rep. 2021;124(1):210–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Benjamini Y, et al. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. doi: 0035-9246/95/57289. [Google Scholar]

- 56. MacDonald SW, et al. Performance variability is related to change in cognition: evidence from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):510–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Anstey KJ. Sensorimotor variables and forced expiratory volume as correlates of speed, accuracy, and variability in reaction time performance in late adulthood. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 1999;6(2):84–95. doi: 10.1076/anec.6.2.84.786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Facer-Childs ER, et al. Circadian phenotype impacts the brain’s resting-state functional connectivity, attentional performance, and sleepiness. Sleep. 2019;42(5):zsz033. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hasan S, et al. Assessment of circadian rhythms in humans: comparison of real-time fibroblast reporter imaging with plasma melatonin. FASEB J. 2012;26(6):2414–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rupp TL, et al. Trait-like vulnerability to total and partial sleep loss. Sleep. 2012;35(8):1163–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Elmenhorst EM, et al. Cognitive impairments by alcohol and sleep deprivation indicate trait characteristics and a potential role for adenosine A1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(31):8009–8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Basner M, et al. Maximizing sensitivity of the psychomotor vigilance test (PVT) to sleep loss. Sleep. 2011;34(5):581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Goel N, et al. PER3 polymorphism predicts cumulative sleep homeostatic but not neurobehavioral changes to chronic partial sleep deprivation. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pellegrino R, et al. A novel BHLHE41 variant is associated with short sleep and resistance to sleep deprivation in humans. Sleep. 2014;37(8):1327–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Maire M, et al. Sleep ability mediates individual differences in the vulnerability to sleep loss: evidence from a PER3 polymorphism. Cortex. 2014;52:47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sin NL, et al. Emotional vulnerability to short sleep predicts increases in chronic health conditions across 8 years. Ann Behav Med. 2021;kaab018. [published online ahead of print]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33821929/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gottlieb DJ, et al. Sleep deficiency and motor vehicle crash risk in the general population: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kaliyaperumal D, et al. Effects of sleep deprivation on the cognitive performance of nurses working in shift. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):CC01–CC03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Swanson LM, et al. Sleep disorders and work performance: findings from the 2008 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America poll. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(3):487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.