Abstract

We evaluated the usefulness of PCR assays that target the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region for identifying mycobacteria at the species level. The conservative and species-specific ITS sequences of 33 species of mycobacteria were analyzed in a multialignment analysis. One pair of panmycobacterial primers and seven pairs of mycobacterial species-specific primers were designed. All PCRs were performed under the same conditions. The specificities of the primers were tested with type strains of 20 mycobacterial species from the American Type Culture Collection; 205 clinical isolates of mycobacteria, including 118 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates and 87 isolates of nontuberculous mycobacteria from 10 species; and 76 clinical isolates of 28 nonmycobacterial pathogenic bacterial species. PCR with the panmycobacterial primers amplified fragments of approximately 270 to 400 bp in all mycobacteria. PCR with the M. tuberculosis complex-specific primers amplified an approximately 120-bp fragment only for the M. tuberculosis complex. Multiplex PCR with the panmycobacterial primers and the M. tuberculosis complex-specific primers amplified two fragments that were specific for all mycobacteria and the M. tuberculosis complex, respectively. PCR with M. avium complex-, M. fortuitum-, M. chelonae-, M. gordonae-, M. scrofulaceum-, and M. szulgai-specific primers amplified specific fragments only for the respective target organisms. These novel primers can be used to detect and identify mycobacteria simultaneously under the same PCR conditions. Furthermore, this protocol facilitates early and accurate diagnosis of mycobacteriosis.

It is estimated that there are 8 million cases of tuberculosis (TB), causing 2.5 million deaths per year, worldwide, making TB the foremost cause of death due to infection. Mycobacterial infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), such as the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), M. fortuitum, and M. chelonae, are also on the increase (20). The increasing number of mycobacterial infections has made it clinically important to quickly identify mycobacteria at the species level. The diagnosis of pathogenic versus nonpathogenic species not only has epidemiological implications but also is relevant for patient management (1).

PCR has proven to be a very useful tool for the rapid diagnosis of infectious diseases, including mycobacteriosis. Many of the PCR assays used for detecting mycobacteria involve species-specific primers targeting the 16S rRNA, hsp65, 32-kDa protein genes, or the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and detect only a single or a limited number of mycobacterial species (10, 13). The ITS between the l6S and 23S rRNA genes is approximately 270 to 360 bp but varies in size from species to species. It is considered to be a suitable target for probes with which additional phylogenetic information can be derived (15). Furthermore, the ITS is suitable for differentiating species of mycobacteria and potentially can be used to distinguish clinically relevant subspecies (12). With respect to mycobacteria, both the high level of spacer sequence variation and the good reproducibility of ITS sequencing suggest the applicability of this approach. The purposes of this study were to design genus-specific and species-specific primers and to determine the PCR conditions for the simple and accurate detection of clinically important mycobacterial species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primer design.

Conservative and polymorphic ITS sequences of mycobacteria were sought in a multialignment of the ITS regions of 33 mycobacterial species using CLUSTAL-W (http://genome.kribb.re.kr) (Table 1). The ITS sequences of 31 mycobacterial species were obtained from GenBank. The ITS regions of M. fortuitum and M. chelonae were cloned and sequenced, as there were no sequence data in GenBank, even though these species are frequently isolated from clinical specimens (20). The sequence identity between the designed primers and the mycobacterial ITS regions was analyzed with a BLAST search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Based on the multialignment analysis data, a mycobacterial genus-specific primer pair and seven species-specific primer pairs were designed (Table 2). A set of primers, ITS-F and mycom-2, was used to amplify partial ITS regions in mycobacteria. The two primers were designed from the highly conserved region on the basis of 16S rRNA and ITS sequences of mycobacteria, respectively (3). Species-specific primers were designed from the polymorphic regions of ITS sequences of mycobacteria.

TABLE 1.

Strains used for sequence analysis and alignment of the ITS regions

| Organism | GenBank accession number(s) |

|---|---|

| M. avium | LO7856, X74494, LO7848, LO7847, L15620, X74054, LO7858, LO7857, LO7855, LO7853, LO7852, LO7851, LO7850, LO7849, Z46421, and Z46422 |

| M. conspicuum | X92668 |

| M. farcinogenes | Y10384 |

| M. gastri | Y14182 and X97633 |

| M. genavense | Y14183 |

| M. gordonae | L42261, L42260, L42259, and L42258 |

| M. habana | X74056 |

| M. intracellulare | Z46425, X75602, X74057, L07859, and Z46423 |

| M. kansasii | X97632, L42262, and L42263 |

| M. leprae | X56657 |

| M. lufu | X74055 |

| M. malmoense | Y14184 and Z35225 |

| M. marinum | Y14185 |

| M. paratuberculosis | X74495 |

| M. phlei | X74493 |

| M. scrofulaceum | L15622 |

| M. senegalense | Y10385 |

| M. shimoidei | AJ005005 and X99219 |

| M. simiae | X75599, Y14186, Y14187, and Y14188 |

| M. smegmatis | AB003598, AB003597, X76257, and U07955 |

| M. szulgai | X99220 |

| M. terrae | Z46427 |

| M. triplex | Y14189 |

| M. triviale | X99221 |

| M. tuberculosis complexa | X58890, L15623, L26330, L26328, M20940, and L26329 |

| M. ulcerans | X99217 |

| M. xenopi | Y14192, L15624, Y14190, and Y14191 |

| Mycobacterium species | L15621 |

| M. fortuitumb | AF144326 |

| M. chelonaeb | AF144327 |

Includes M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, M. bovis, and M. microti.

ITS sequences of these two species were not published in GenBank; they were cloned and sequenced by us, and the sequences were submitted to GenBank.

TABLE 2.

Genus- and species-specific primers designed for the detection of mycobacteria

| Primera | Target species (expected size, bp) | Position(s) | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS-F | Panmycobacteria (variable) | 16S rRNA | 5′-TGGATCCGACGAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′ |

| mycom-2 | ITS region | 5′-TGGATAGTGGTTGCGAGCAT-3′ | |

| TBF | M. tuberculosis (121) | 28–47 | 5′-TGGTGGGGCGTAGGCCGTGA-3′ |

| TBR | 129–148 | 5′-CACTCGGACTTGTTCCAGGT-3′ | |

| MACF | MAC (144) | 117–136 | 5′-CCCTGAGACAACACTCGGTC-3′ |

| MACR | 241–260 | 5′-GTTCATCGAAATGTGTAATT-3′ | |

| FORF | M. fortuitum (223) | 45–64 | 5′-CCGTGAGGAACCGGTTGCCT-3′ |

| FORR | 248–267 | 5′-TAGCACGCAGAATCGTGTGG-3′ | |

| CHEF | M. chelonae (93) | 59–78 | 5′-GTTACTCGCTTGGTGAATAT-3′ |

| CHER | 133–152 | 5′-TCAATAGAATTGAAACGCTG-3′ | |

| GORF | M. gordonae (152) | 84–103 | 5′-CGACAACAAGCTAAGCCAGA-3′ |

| GORR | 216–235 | 5′-GCATCAAAATGTATGCGTTG-3′ | |

| SCOF | M. scrofulaceum (99) | 131–150 | 5′-TCGGCTCGTTCTGAGTGGTG-3′ |

| SCOR | 210–229 | 5′-TAAACGGATGCGTGGCCGAA-3′ | |

| SZUF | M. szulgai (105) | 124–143 | 5′-AACACTCAGGCTTGGCCAGA-3′ |

| SZUR | 209–228 | 5′-GAGGGCAGCGCATCCAATTG-3′ |

Primers are grouped in pairs.

Bacterial strains.

The type strains of 20 mycobacterial species from the American Type Culture Collection and 1l8 M. tuberculosis and 87 NTM clinical isolates were used in this study. M. tuberculosis clinical isolates were randomly selected from the stored strains at the mycobacterial laboratories of Pusan National University Hospital and National Masan Tuberculosis Hospital. NTM (clinical isolates) were identified by conventional methods and kindly provided by the Korean National Tuberculosis Association, which is the reference laboratory for tuberculosis diagnosis in eastern Asia. In the case of discrepancies between traditional and PCR methods, we confirmed our results by sequence analysis of the ITS. Fifty-five clinical isolates of nonmycobacterial pathogens were included to confirm the specificity (Table 3). These isolates were identified biochemically or with commercial kits, such as API (Biomerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and Vitek (BioMerieux Vitek, Hazelwood, Mo.) kits.

TABLE 3.

Mycobacterial and nonmycobacterial isolates used in this study

| Mycobacterial type strains and clinical isolates (no.) |

PCR resulta | Nonmycobacterial clinical isolates (no.) |

PCR resulta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. abscessus ATCC 19977 | + | Aeromonos hydrophila (2) | − | |

| M. agri ATCC 27406 | + | Burkholderia cepacia (2) | − | |

| M. asiatticum ATCC 25276 | + | Candida albicans (2) | − | |

| M. austroafricanum ATCC 33464 | + | Citrobacter freundii (2) | − | |

| M. avium ATCC 25291 | + | Enterobacter aerogenes (2) | − | |

| M. bovis ATCC 19210 | + | Enterobacter cloacae (2) | − | |

| M. chelonae ATCC 35752 | + | Enterococcus faecalis (2) | − | |

| M. flavescens ATCC 14474 | + | Enterococcus faecium (2) | − | |

| M. fortuitum ATCC 6841 | + | Enterococcus raffinosis (2) | − | |

| M. gordonae ATCC 14470 | + | Escherichia coli (2) | − | |

| M. intracellulare ATCC 13950 | + | Klebsiella pneumoniae (2) | − | |

| M. kansasii ATCC 12478 | + | Plesiomonos shigelloides (2) | − | |

| M. phlei ATCC 354 | + | Proteus mirabilis (2) | − | |

| M. scrofulaceum ATCC 19981 | + | Proteus vulgaris (2) | − | |

| M. smegmatis ATCC 21701 | + | Providencia rettgeri (2) | − | |

| M. szulgai ATCC 35799 | + | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2) | − | |

| M. terrae ATCC 15755 | + | Rahnella aquatilis (1) | − | |

| M. triviale ATCC 23292 | + | Salmonella spp. (2) | − | |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | + | Serratia marcescens (2) | − | |

| M. vaccae ATCC 15483 | + | Shewanella putrefaciens (2) | − | |

| MAC clinical isolates (31) | + | Shigella flexneri (2) | − | |

| M. chelonae clinical isolates (10) | + | Shigella sonnei (2) | − | |

| M. fortuitum clinical isolates (13) | + | Staphylococcus epidermidis (2) | − | |

| M. gordonae clinical isolates (10) | + | Staphylococcus aureus (2) | − | |

| M. scrofulaceum clinical isolates (3) | + | Streptococcus agalactiae (2) | − | |

| M. szulgai clinical isolates (10) | + | Streptococcus intermedius (2) | − | |

| M. terrae clinical isolates (10) | + | Streptococcus pneumoniae (2) | − | |

| M. tuberculosis clinical isolates (118) | + | Vibrio paraphaelmolyticus (2) | − |

Result of PCR with ITS-F and mycom-2 primers: +, PCR amplification; −, no PCR amplification.

Preparation of genomic DNA and PCR.

All the mycobacteria were subcultured on Ogawa media, and nonmycobacteria were subcultured on blood agar plates. DNA was prepared from freshly grown colonies using an InstaGene matrix kit (Bio-Rad). PCR was performed with each pair of genus-specific primers and species-specific primers under the same conditions. Multiplex PCR was performed using panmycobacterial and M. tuberculosis complex-specific primers in the same reaction tube. The primers were synthesized at a 50-nmol concentration (reagents were supplied by BioBasic Inc.). We tested the PCR conditions by adding various concentrations of tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC), dimethyl sulfoxide, and glycerol to reduce nonspecific amplifications; finally, the following conditions were chosen. The constituents of the PCR mixtures were as follows: 500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris HCl (pH 9.0), 1% Triton X-100, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dGTP, dTTP, and dCTP), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 μM TMAC, 10 pmol of each primer, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (BioBasic). Each reaction was carried out for 5 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and 10 min at 72°C. The products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gels. For multiplex PCR for the detection of mycobacteria and M. tuberculosis, the primer concentration was optimized by mixing the ITS-F (10 pmol), mycom-2 (30 pmol), and TBF (20 pmol) primers together.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF144326 and AF144327.

RESULTS

Designed primers.

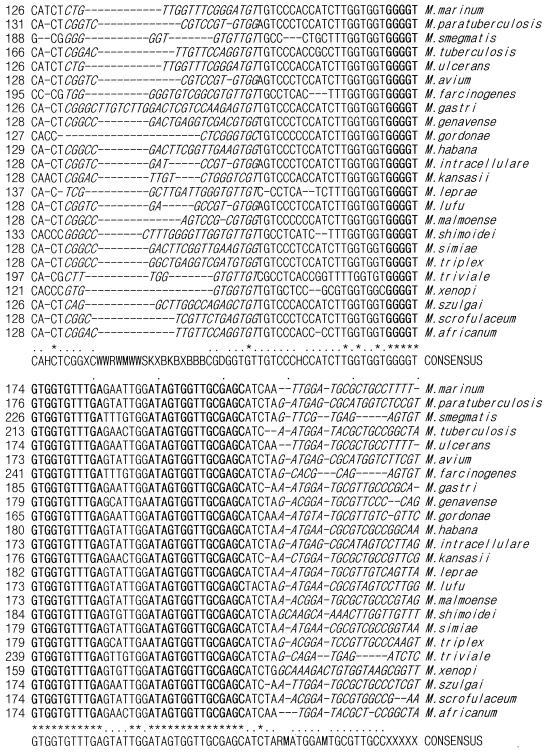

The ITS sequence has two conserved regions and several polymorphic regions in the 33 mycobacteria examined, including M. fortuitum and M. chelonae (Fig. 1). One pair of genus-specific and seven pairs of species-specific primers for mycobacteria were designed after consideration of product size and melting temperature (Table 3). The pair of panmycobacterial primers was expected to amplify specific fragments of 270 to 400 bp from species to species. Each pair of M. tuberculosis complex-, MAC-, M. fortuitum-, M. chelonae-, M. gordonae-, M. scrofulaceum-, and M. szulgai-specific primers was expected to amplify specific fragments of 121, 144, 223, 93, 152, 99, and 105 bp in the respective target mycobacteria.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the mycobacterial ITS sequences. The alignment includes conserved and polymorphic regions derived from the mycobacterial species. The conserved sequences are in bold print, and the polymorphic sequences are in italic print. Dashes represent deletions, and asterisks represent identity.

Detection of mycobacteria.

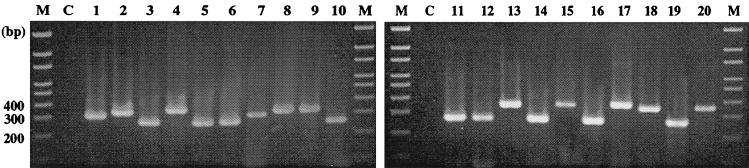

For all the tested type strains of mycobacteria, the specific fragments were amplified in the PCR with the ITS-F and mycom-2 primers. The amplicons were approximately 270 to 400 bp in size, as expected (Fig. 2). For 118 M. tuberculosis and 87 NTM clinical isolates, the expected specific fragments were amplified with genus-specific primers (ITS-F and mycom-2). Nonspecific amplicons were not seen in any of the nonmycobacterial pathogens tested (Table 3).

FIG. 2.

Genus-specific amplification of mycobacterial ITS by primers ITS-F and mycom-2. Lanes M, 100-bp size markers; lanes C, negative control; lane 1, M. abscessus ATCC 19977; lane 2, M. agri ATCC 27406; lane 3, M. asiaticum ATCC 25276; lane 4, M. austroafricanum ATCC 33464; lane 5, M. avium ATCC 25291; lane 6, M. bovis ATCC 19210; lane 7, M. chelonae ATCC 35752; lane 8, M. flavescens ATCC 14474; lane 9, M. fortuitum ATCC 6841; lane 10, M. gordonae ATCC 14470; lane 11, M. intracellulare ATCC 13950; lane 12, M. kansasii ATCC 12478; lane 13, M. phlei ATCC 354; lane 14, M. scrofulaceum ATCC 19981; lane 15, M. smegmatis ATCC 21701; lane 16, M. szulgai ATCC 35799; lane 17, M. terrae ATCC 15755; lane 18, M. triviale ATCC 23292; lane 19, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; lane 20, M. vaccae ATCC 15483.

Identification of mycobacteria.

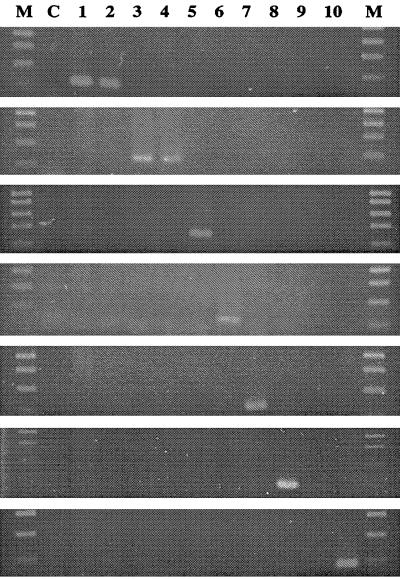

PCR with the M. tuberculosis complex-specific primers, TBF and TBR, amplified an approximately 121-bp fragment only in the M. tuberculosis and M. bovis type strains (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3, PCR with each pair of NTM-specific primers amplified the specific fragment of the expected size only in strains of the target organism. All NTM clinical isolates were tested with each set of species-specific primers, and the specificity was confirmed.

FIG. 3.

PCR with each pair of mycobacterial species-specific primers. From top to bottom, primers TBF and TBR, MACF and MACR, FORF and FORR, CHEF and CHER, GORF and GORR, SZUF and SZUR, and SCOF and SCOR. Lanes M, 100-bp DNA ladder size markers; lane C, negative control; lane 1, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; lane 2, M. bovis; lane 3, M. avium; lane 4, M. intracellulare; lane 5, M. fortuitum; lane 6, M. chelonae; lane 7, M. gordonae; lane 8, M. szulgai; lane 9, M. terrae; lane 10, M. scrofulaceum.

Multiplex PCR.

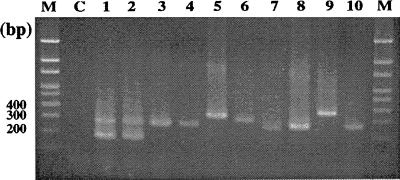

PCR with panmycobacterial and M. tuberculosis complex-specific primers in the same tube amplified the two expected fragments, approximately 274 and 121 bp in size, in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis type strains and one panmycobacterial fragment in each of the NTM type strains (Fig. 4). The same result was also obtained for clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis and NTM. No fragment was found by PCR for nonmycobacterial pathogens.

FIG. 4.

Multiplex PCR with panmycobacterial and M. tuberculosis-specific primers. Lanes M, 100-bp DNA ladder size markers; lane C, negative control; lane 1, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; lane 2, M. bovis; lane 3, M. avium; lane 4, M. intracellulare; lane 5, M. fortuitum; lane 6, M. chelonae; lane 7, M. gordonae; lane 8, M. szulgai: lane 9, M. terrae; lane 10, M. scrofulaceum.

DISCUSSION

Rapid identification of species of mycobacteria is an important factor for a successful diagnosis of mycobacteriosis. It facilitates selection of the appropriate drug therapy. However, it is not easy to identify species of mycobacteria, especially NTM. The Accuprobe culture confirmation kit (Gen-Probe Inc., San Diego, Calif.), one of the commercially available methods for mycobacterial identification, can be used for only a limited number of mycobacterial species (13). Furthermore, the kit is relatively expensive. High-performance liquid chromatography can also be used for mycobacterial identification, and its operating cost is low. However, the equipment is expensive (7).

Currently, the widely accepted strategy formulated to improve methods for mycobacterial strain identification includes analysis of the gene encoding 16S rRNA (15). Other target genes have been proposed for the identification of mycobacteria by PCR-based sequencing. They included the spoligotyping (spacer oligonucleotide typing) region (2, 21), the 32-kDa protein gene (16), the dnaJ gene (18), the superoxide dismutase gene (22), the 65-kDa heat shock protein gene (hsp65) (14, 19), and the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) (11). Each technique has several advantages and disadvantages. For example, an excessive degree of variability, such as that found in the hsp65 gene, may be undesirable, because such variability or instability of species-specific signatures will make the development of reliable probes that cover all strains within a species impossible (15). 16S rDNA sequences do not vary greatly within a species, and they are identical in some species (20). Molecular typing by 16S rRNA sequence determination is not only more rapid but also more accurate than traditional typing (17).

Comparative sequence analysis of amplified rpoB DNAs can be used efficiently to identify clinical isolates of mycobacteria in parallel with traditional culture methods and as a supplement to 16S rDNA gene analysis. For M. tuberculosis, rifampin resistance can be simultaneously determined (11).

This study demonstrated that an ITS-based PCR method has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for the detection and identification of medically important species of mycobacteria. Glennon et al. (8) first speculated on its utility for the diagnosis of TB. The ITS sequence between the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes, which is more variable than the 16S rRNA gene itself, has been shown to be species specific in many microorganisms (9). However, there is little between-species variation in the length of the spacer, which ranges from 235 nucleotides for M. xenopi to 285 nucleotides for M. gastri, a slowly growing mycobacterium. The spacer sequences of slowly growing species are approximately 75 nucleotides shorter than those of rapid growers. Frothingham and Wilson (6) demonstrated intraspecies sequence polymorphisms in 4 of 11 species. M. gastri and M. avium each were split into two distinct sequevars (sequence variations), designated Mga-A and Mga-B and Mav-A and Mav-B, respectively, based on the nomenclature proposed by Frothingham and Wilson (6).

It was possible to develop genus- and species-specific primers because the ITS has two conserved regions and several polymorphic regions in the 33 mycobacterial species. The two conserved regions are close to each other within the mycobacterial ITS (Fig. 1). The primers mycom-1 and mycom-2 were designed from these two conserved sequences. The amplicons for the primer set mycom-1 and ITS-R were expected to be approximately 120 to 250 bp long. In a previous study, however, our group demonstrated that these primers amplified nonspecific bands in 28 clinical isolates of 14 species (3). Therefore, we used ITS-F and mycom-2 as a pair of genus-specific primers.

To develop multiplex PCR that will identify clinically important mycobacteria in one reaction tube, the PCR conditions should be the same in the individual reactions. It was most difficult to find conditions under which specific bands were produced successfully under the same PCR conditions, despite variability in the length and GC content of each pair of primers. We studied the influence of TMAC, dimethyl sulfoxide, and glycerol on the PCRs and found that the use of TMAC in the PCR mixture dramatically reduced or eliminated nonspecific priming events, thereby enhancing the specificity of the reaction. In fact, TMAC binds selectively to dA-dT base pairs, altering the dissociation equilibrium and increasing the melting temperature (5). In a solution containing 3.0 M TMAC, this displacement is sufficient to shift the melting temperature of dA-dT base pairs to that of dG-dC base pairs. The PCR yield increased with 15 to 60 μM TMAC, while 150 μM TMAC completely inhibited the reaction (4). In this study, PCR was carried out in the presence of 0, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM TMAC. We observed an increase in PCR specificity at 10 μM TMAC (data not shown). A nonspecific upper band, of approximately 550 bp, was seen with M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. We did not adjust the concentrations of target DNAs of type strains and clinical isolates. Because we tested PCR with clinical isolates, target DNA was not constant. We optimized the PCR conditions.

In conclusion, the novel primers that we designed could be used to detect and identify mycobacteria simultaneously under the same PCR conditions. Furthermore, this protocol facilitated the early and accurate diagnosis of mycobacteriosis. Further experiments will be necessary to determine the conditions needed to detect mycobacteria directly from patient specimens, such as sputum. At the same time, the conditions for successfully performing multiplex PCR using at least four sets of primers, including genus-specific and M. tuberculosis-, MAC-, and M. fortuitum-specific primers, should be studied.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health R & D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HMP-99-V-B-0004).

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156:S1–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Aranaz A, Liebana E, Mateos A, Dominguez L, Vidal D, Domingo M, Gonzolez O, Rodriguez-Ferri E F, Bunschoten A E, van Embden J D, Cousins D. Spacer oligonucleotide typing of Mycobacterium bovis strains from cattle and other animals: a tool for studying epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2734–2740. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2734-2740.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang C L, Son H C, Kim S H, Kim C M, Chung B S, Park S K, Park H K, Jang H J, Song S D. Proceedings of XX World Congress of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Bologna, Italy: Litosei-Rostignano-Bologna; 1999. Detection of mycobacteria by amplifying the internal transcribed spacer regions with novel genus-specific primers; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevet E, Lemaitre G, Katinka M D. Low concentrations of tetramethylammonium chloride increase yield and specificity of PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3343–3344. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connors T D, Burn T C, VanRaay T, Germino G G, Klinger K W, Landes G M. Evaluation of DNA sequencing ambiguities using tetramethylammonium chloride hybridization conditions. Biotechniques. 1997;22:1088–1090. doi: 10.2144/97226bm17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frothingham R, Wilson K H. Sequence-based differentiation of strains in the Mycobacterium avium complex. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2818–2825. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2818-2825.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glennon M, Cormican M G, Ni Riain U, Heginbothom M, Gannon F, Smith T. A Mycobacterium malmoense-specific DNA probe from the 16S/23S rRNA intergenic spacer region. Mol Cell Probes. 1996;10:337–345. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glennon M, Smith T, Cormican M, Noone D, Barry T, Maher M, Dawson M, Gilmartin J J, Gannon F. The ribosomal intergenic spacer region: a target for the PCR based diagnosis of tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1994;75:353–360. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(94)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurtler V, Stanisich V A. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S–23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology. 1996;142:3–16. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kauppinen J, Mantyjarvi R, Katila M L. Mycobacterium malmoense-specific nested PCR based on a conserved sequence detected in random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprints. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1454–1458. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1454-1458.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim B J, Lee S H, Lyu M A, Kim S J, Bai G H, Chae G T, Kim E C, Cha C Y, Kook Y H. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1714–1720. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1714-1720.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lappayawichit P, Rienthong S, Rienthong D, Chuchottaworn C, Chaiprasert A, Panbangred W, Saringcarinkul H, Palittapongarnpim P. Differentiation of Mycobacterium species by restriction enzyme analysis of amplified 16S–23S ribosomal DNA spacer sequences. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996;77:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter E, Niemann S, Rusch-Gerdes S, Hoffner S. Identification of Mycobacterium kansasii by using a DNA probe (AccuProbe) and molecular techniques. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:964–970. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.964-970.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ringuet H, Akoua-Koffi C, Honore S, Varnerot A, Vincent V, Berche P, Gaillard J L, Pierre-Audigier C. hsp65 sequencing for identification of rapidly growing mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:852–857. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.852-857.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth A, Fischer M, Hamid M E, Michalke S, Ludwig W, Mauch H. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S–23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:139–147. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.139-147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soini H, Viljanen M K. Diversity of the 32-kilodalton protein gene may form a basis for species determination of potentially pathogenic mycobacterial species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:769–773. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.769-773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Springer B, Stockman L, Teschner K, Roberts G D, Bottger E C. Two-laboratory collaborative study on identification of mycobacteria: molecular versus phenotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:296–303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.296-303.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takewaki S, Okuzumi K, Manabe I, Tanimura M, Miyamura K, Nakahara K, Yazaki Y, Ohkubo A, Nagai R. Nucleotide sequence comparison of the mycobacterial dnaJ gene and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for identification of mycobacterial species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:159–166. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Bottger E C, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troesch A, Nguyen H, Miyada C G, Desvarenne S, Gingeras T R, Kaplan P M, Cros P, Mabilat C. Mycobacterium species identification and rifampin resistance testing with high-density DNA probe arrays. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:49–55. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.49-55.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yo G S, Li H L, Torrea G, Bunschoten A, van Embden J, Gicquel B. Evaluation of spoligotyping in a study of the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2210–2214. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2210-2214.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zolg J W, Philippi-Schulz S. The superoxide dismutase gene, a target for detection and identification of mycobacteria by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2801–2812. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2801-2812.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]