Abstract

Collagen fibrils, linear arrangements of collagen monomers, 20–500 nm in diameter, comprising hundreds of molecules in their cross-section, are the fundamental structural unit in a variety of load-bearing tissues such as tendons, ligaments, skin, cornea, and bone. These fibrils often assemble into more complex structures, providing mechanical stability, strength, or toughness to the host tissue. Unfortunately, there is little information available on individual fibril dynamics, mechanics, growth, aggregation and remodeling because they are difficult to image using visible light as a probe. The principle quantity of interest is the fibril diameter, which is difficult to extract accurately, dynamically, in situ and non-destructively. An optical method, differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy has been used to visualize dynamic structures that are as small as microtubules (25 nm diameter) and has been shown to be sensitive to the size of objects smaller than the wavelength of light. In this investigation, we take advantage of DIC microscopy’s ability to report dimensions of nanometer scale objects to generate a curve that relates collagen diameter to DIC edge intensity shift (DIC-EIS). We further calibrate the curve using electron microscopy and demonstrate a linear correlation between fibril diameter and the DIC-EIS. Using a non-oil immersion, 40x objective (NA 0.6), collagen fibril diameters between ~100 nm to ~300 nm could be obtained with ±11 and ±4 nm accuracy for dehydrated and hydrated fibrils, respectively. This simple, nondestructive, label free method should advance our ability to directly examine fibril dynamics under experimental conditions that are physiologically relevant.

Keywords: Collagen Fibril Diameter, Differential Interference Contrast Microscopy, DIC Edge Intensity Shift, SEM, TEM

1. Introduction

Collagen is the most abundant protein in vertebrates and the principle load bearing molecule in their tissues. While there has been over 50 years of research into collagen fibril assembly and growth (Gross and Schmitt, 1948), we are still remarkably deficient in our knowledge of the mechanisms that drive animal structure formation and evolution. Collagen fibrils, 20 nm to a few hundred nanometers in diameter (Parry et al., 1978), are the basic building block in the complex hierarchical structure of collagenous tissues. However, our ability to conduct quantitative studies of fibril dynamics and mechanics is limited. The theoretical limit of visible light microscopy, 1.22λ/(2NA), translates to approximately 220 nm. This resolution limit does not permit very accurate determination of collagen fibril diameter or changes in diameter. Such measurements are critical to understand basic assembly and degradation dynamics in controlled systems.

Fibril diameter has been measured directly using different methods such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Starborg et al., 2013), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Svensson et al., 2017), and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Chernoff and Chernoff, 1992). TEM has been widely used for fibril diameter measurement in a variety of tissues (Birk and Trelstad, 1986; Dyer and Enna, 1976; Flint et al., 1984; Hama et al., 1976) and reconstituted fibrils (Bahr, 1950; Gross et al., 1954; Jackson and Fessler, 1955). To prepare samples for TEM, tissues need to be dehydrated, fixed, embedded in resin, cut into extremely thin slices, and stained. Transverse sections are usually used to measure fibril diameter; alternatively, extracted fibrils or reconstituted fibrils can be dried and stained on TEM grids which will lead to a longitudinal fibril view. Nevertheless, the TEM preparation procedure is destructive due to dehydration (Leonardi et al., 1983), fixation (Parry and Craig, 1977), and sectioning (Michna, 1984). It has been shown that fibrils can shrink and flatten on the support surface of a TEM grid (Holmes et al., 2010) compared to the wet fibrils in physiological conditions (Eikenberry et al., 1982b). SEM, another electron microscopy (EM) method, enables the visualization of the three-dimensional collagen network and provides further insight into the nature of the collagen fibrils and their size (Inoue et al., 1969; Okuda, 1970). SEM has also been used to measure fibril diameter in different tissues (Clarke, 1974; Inoue and Takeda, 1975; Lin et al., 1993; Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006); nevertheless, samples are usually destructively dried, mounted on a metal stub, and then coated before being observed.

The surface of collagen fibrils without any specific preparation can be investigated in ambient conditions using AFM. AFM images are obtained by scanning the fibril surface with a finely shaped tip held at an atomic distance and probing the interactions between the tip and the fibril surface. Atoms at the apex of the tip and the atoms on the fibril surface interact with each other via short-range chemical forces and long-range Van der Waals and electrostatic forces (Israelachvili, 2011). Researchers have used AFM to measure the diameter of reconstituted collagen fibrils (Baselt et al., 1993; Gale et al., 1995; Revenko et al., 1994) as well as native fibrils (Aragno et al., 1995; Fullwood et al., 1995; Meller et al., 1997). The most important advantage of AFM compared to EM methods is the ability to image samples in their native state and to study live cellular events (Ge-Ge et al., 2017; Suzuki et al., 2013). However, there are still some limitations: AFM is limited to measurements on isolated fibrils, has a rather slow temporal resolution (Heinisch et al., 2012), it is necessary to consider image distortion due to the tip size, and fibril adhesion to surfaces could change the fibril’s shape (Yamamoto et al., 1997).

Fibril diameters have also been estimated by other methods such as small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and second-harmonic generation microscopy (SHG) to overcome the destructive sample preparation procedure. SAXS is a common method to measure average collagen fibril diameter of a tissue in its native state without any additional treatment (Boote et al., 2003; Boote et al., 2011; Daxer et al., 1998; Eikenberry et al., 1982a; Meek and Leonard, 1993). When X-rays pass through a collagenous tissue, they provide detailed information on arrangement of collagen molecules and fibrils (Goodfellow et al., 1978; Meek and Quantock, 2001). SAXS is non-destructive and allows for a statistically robust sampling (Goh et al., 2005). However, it provides average measurements of collagen fibril diameters in a tissue and it has not been used for individual fibrils.

SHG has been used to study of collagen fibrils both in vivo (Zoumi et al., 2002) and in vitro (Lutz et al., 2012). Collagen has a highly anisotropic molecular structure which makes it a strong source of SHG (Cicchi et al., 2013; Cox and Kable, 2006). However, measurement of fibril diameter is not directly possible from the nonlinear optical signal of SHG microscopy. Bancelin et al. developed a method to determine collagen fibril diameter using SHG and verifying the results with TEM images (Bancelin et al., 2014). They reported absolute measurement limit of individual fibrils as small as 30 nm in diameter with rather large uncertainty (± 25 nm). While SHG could detect collagen fibrils without introducing exogenous probes, there remain some limitations in addition to the low accuracy: SHG microscopy is expensive and technically demanding, SHG can only be used for unipolar fibrils with constant collagen density, and the SHG signal depends on the fibril angle which can introduce inaccuracy in quantitative studies (Williams et al., 2005). Nonetheless, SHG is a potentially powerful label-free method to extract information from collagen networks in real time and under physiologically relevant conditions.

All the above methods have been extremely valuable in studying of collagen fibrils, but they all lack the ability to measure collagen fibril diameter in live studies performed under simple light microscopy. DIC microscopy is one of the most popular label-free methods to visualize fibrillar structures. DIC is simple, inexpensive and ubiquitous. A major advantage of DIC is that collagen fibrils can be studied directly in solution (Zareian et al., 2016) without previously being dehydrated, fixed, or stained. However, quantitative studies are limited for small structures like collagen fibrils due to diffraction limit of visible light.

Biological specimens are weak-phase objects and their conventional images have low contrast and poor visibility. DIC microscopy was introduced over a half of a century ago for the study of phase objects and has been widely used by biologists since then. A video-enhanced DIC method was introduced by Allen et al. to improve the performance of DIC microscopy and detect microtubules as small as 25 nm in diameter (Allen et al., 1981). The method was widely used, for example, to measure microtubule growth velocity (Dogterom and Yurke, 1997) and image reconstitution of physiological microtubule dynamics (Kinoshita et al., 2001), and enabled the discovery of kinesin (Salmon, 1995). Nevertheless, due to innate nonlinearities (Fu et al., 2010), DIC microscopy has been only used for qualitative imaging and was therefore not appropriate for accurate diameter measurements of those small biological samples.

Previously, attempts were made to measure collagen fibril diameter with DIC microscopy (Bhole et al., 2009; Flynn, 2012) and fibril images were simulated using Mie scattering theory. A linear relationship between fibril diameter and DIC edge intensity shift (DIC-EIS) was predicted at that time. However, due to vibration of fibrils in the thin field of view of DIC, fibril diameter was not resolved experimentally. In this investigation we used EM methods in combination with DIC to not only show the sensitivity of DIC-EIS to diameter change, but also to correlate DIC-EIS to fibril diameter without requiring further EM processing.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Fibril extraction

Type I collagen fibrils were extracted from bovine scleras (Liu et al., 2016). Briefly, the scleral tissue was removed from the cornea and surrounding adipose tissue. The sclera was then cut into approximately 1 cm by 2 cm pieces. Some shallow cuts were made on each piece. Pieces of sclera were rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then placed into an extraction medium (pH 7.5–8.0) containing >1000 BAEE unit/mL trypsin (9002-07-7, Sigma-Aldrich), 4 mM ethylenediaminetraacetic acid (60-00-4, Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 M tris-HCl (1185-53-1, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.05% sodium azide (26628-22-8, Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were shaken for ~5 minutes until the sclera swelled and some fibrils were removed. Fibril suspensions were centrifuged at 5000×g for 30 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the fibril pellet was resuspended and stored in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide at 4 °C.

2.2. Fibril Preparation for TEM-DIC imaging

Referenced TEM grids (01841-F, Ted Pella Inc.) were placed on a rotatable dish and between two small cover glass (1217H20, Thomas Scientific) to not directly touch the bottom glass and prevent distortion of the formvar layer. A 20 μL volume of the fibril suspension was pipetted on top of the grid. Fibrils were air-dried on the TEM grid and imaged first with DIC microscopy and then TEM.

2.3. DIC Imaging

All DIC images were taken on a Nikon inverted microscope (ECLIPSE TE2000-E) equipped with a CoolSNAP EZ CCD Camera and a 40x objective (Plan Fluor ELWD 40x Nikon, NA 0.6). Air-dried fibrils on TEM grids were imaged with DIC microscopy at different angles to the shear axis of the light path. Dehydrated and hydrated fibrils on PDMS sheets and glass were imaged with DIC microscopy while they were oriented perpendicular to the shear axis of the light path (Fig. 1a and 1b).

Fig. 1.

DIC-EIS of collagen fibrils. (a) Vibration direction of analyzer and polarizer in an inverted microscope and the resulting shearing direction. (b) Schematic of a collagen fibril oriented perpendicular to the shear axis. (c) Intensity profile across the collagen fibril along the shear axis when the fibril diameter is larger than the diffraction limit of visible light microscopy. The final image has spatially separated intensity amplitude shifts and the specimen’s size can be determined using conventional imaging techniques. (d) Intensity profile across the collagen fibril along the shear axis when the fibril diameter is smaller than the diffraction limit of visible light microscopy. The intensity amplitude shifts along the shear axis are not completely resolved.

2.4. TEM Processing

TEM grids were stained three times on a droplet of 1.5% uranyl acetate for three seconds each time. The grids were dried with filter paper and imaged with a JEOL JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope.

2.5. Microfabrication of Trenches in PDMS Sheets for SEM-DIC imaging

Standard UV lithography processes were used to create a mold for casting the microstructures. Trenches of 25 μm wide and 20 μm deep were designed in SolidWorks software and printed out on high-resolution transparencies. Single side polished silicon (Si) was used to fabricate the master mold using photolithography process with a negative near-UV photoresist (SU-8 2050 Microchem Corp.). The Si wafer was spin-coated with the photoresist, then baked for solvent removal and exposed to UV light through the printed mask. The exposed wafer was then post-baked and developed to obtain a master mold containing the microstructures. Once the mold fabrication was complete, trenches of PDMS were casted out of the SU-8 master mold by performing standard soft lithography method. PDMS prepolymer mixture (Sylgard184, DowCorning) was prepared from the elastomer base and curing agent at a 10:1 weight ratio. The mixture was then vacuumed to remove air bubbles. The silicon mold was spin-coated with the mixture (100 μm thickness) and then cured at 60 °C for 6 h. Hardened PDMS with microstructures was peeled off the mold and cut into 5 μm by 15 μm pieces.

2.6. Fibril Preparation for SEM-DIC imaging

PDMS sheets were plasma cleaned and placed on a dish. A 50 μL volume of collagen fibrils was pipetted on an 8 mm coverglass that was placed beside the PDMS sheet. Two glass microneedles were used to draw collagen fibrils out of fibril solution and place them over trenches of PDMS. The microneedles were held by capillary holders and moved by electronic micromanipulators (TransferMan NK 2, Eppendorf). Fibrils oriented perpendicular to the shear axis of the light path were imaged in DIC microscopy before SEM imaging.

2.7. SEM Processing

PDMS sheets with collagen fibrils on them were placed on SEM stubs and coated with 5 nm of platinum using a spotter coater. Collagen fibrils were observed under a field‐emission SEM (S‐4700, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Several parameters were tested to 1) obtain high resolution images that allows for fibril diameter measurement and 2) keep the electron dose as low as possible to prevent fibril destruction under the electron beam. Best results were obtained at 1.5 kV, 3 mm working distance, 50 μm objective lens apertures, 2560×1920 image resolution, and 16 sec acquisition time. The chosen setting was stable for at least 2 images to ensure that fibrils were stable during the first image.

2.8. DIC images of Dry/Hydrated Fibrils over Trenches of PDMS

Because the dehydration of fibrils which were previously placed over trenches of PDMS was destructive, fibrils were first placed over trenches of PDMS and imaged dry and then in PBS with DIC. Five fibrils were imaged in the dehydrated condition and then each fibril was hydrated and imaged at 6 time points in PBS: 10 minutes, 30 minutes, 2 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, and 2 days after adding PBS.

2.9. DIC images of Dry/Hydrated Fibrils on Glass

DIC-EIS of fibrils on glass was used to investigate the reversibility of fibril diameter change after dehydration. Collagen fibril suspension in PBS was added to a glass bottom dish and fibrils were permitted to settle on the glass. DIC images of fibrils were captured in PBS before drying, after air drying, and finally after rehydration in PBS.

2.10. Image Processing

TEM images were stitched together in Photoshop software to create large images of fibrils. The large images were used to measure fibril diameter as a function of position along the fibril in ImageJ software. The image processing to obtain fibril diameter from SEM images and DIC-EIS from DIC images were performed in Matlab (Mathworks, Inc., Natick MA) as follows: SEM images were uploaded into Matlab. A region of interest (ROI) was defined around the fibril and edges of the fibril were found by defining a threshold intensity. DIC images were also uploaded into Matlab. An ROI was defined around the middle section of the fibril (10 μm) over trenches of PDMS. The maximum and the minimum intensities of all columns (across the fibril) were found and DIC-EIS was calculated as the difference between the maximum and the minimum intensities.

Figure 1 further clarifies how DIC-EIS is measured from DIC images of collagen fibrils. If the fibril diameter is larger than the limit of visible light microscopy, the final image has spatially separated intensity patterns along the shear axis (Fig. 1c) and the diameter can be determined from the separation of the two patterns. As fibril diameter decreases, patterns merge and the superimposed intensity patterns result in reduced intensity (Fig. 1d).

2.11. Data Analysis and Statistical Information

To measure DIC-EIS, each fibril was imaged 3 times per condition and each image was processed 5 times in MATLAB. The results were reported as mean ± standard deviation.

The average DIC-EIS and the average diameter of fibrils were used to show DIC-EIS is linearly correlated to collagen fibril diameter. The accuracy of the prediction (or the standard error of the estimate, σest) was calculated using

where Y is an actual score, Y’ is a predicted score, and N is the number of pairs of scores.

To show that DIC-EIS is unaffected by small changes in fibril direction, 35 fibrils were imaged with 0°−15°, 15°−30°, 30°−45° ,45°−60°, 60°−75°, and 75°−90° deviated from the northwest-southeast direction. The DIC-EIS values were normalized to the max DIC-EIS values (fibrils deviated 0°−15° from the northwest-southeast direction) and reported as mean ± standard deviation. The two sample t-test (p < 0.05) was used to determine whether or not each group is significantly different from the group with 0°−15° deviation from the northwest-southeast direction.

ANOVA tests (p < 0.05) were used to show whether or not the DIC-EIS of five rehydrated fibrils changed over time (10 minutes, 30 minutes, 2 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, and 2 days after adding PBS). Two sample t-tests (p < 0.05) were used to show that the DIC-EIS of all five wet fibrils were significantly different. Each fibril was compared with the closest fibril in size to it. DIC-EIS of wet fibrils, before and after dehydration, were analyzed using paired sample t-tests (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. DIC-EIS is sensitive to collagen fibril diameter variation

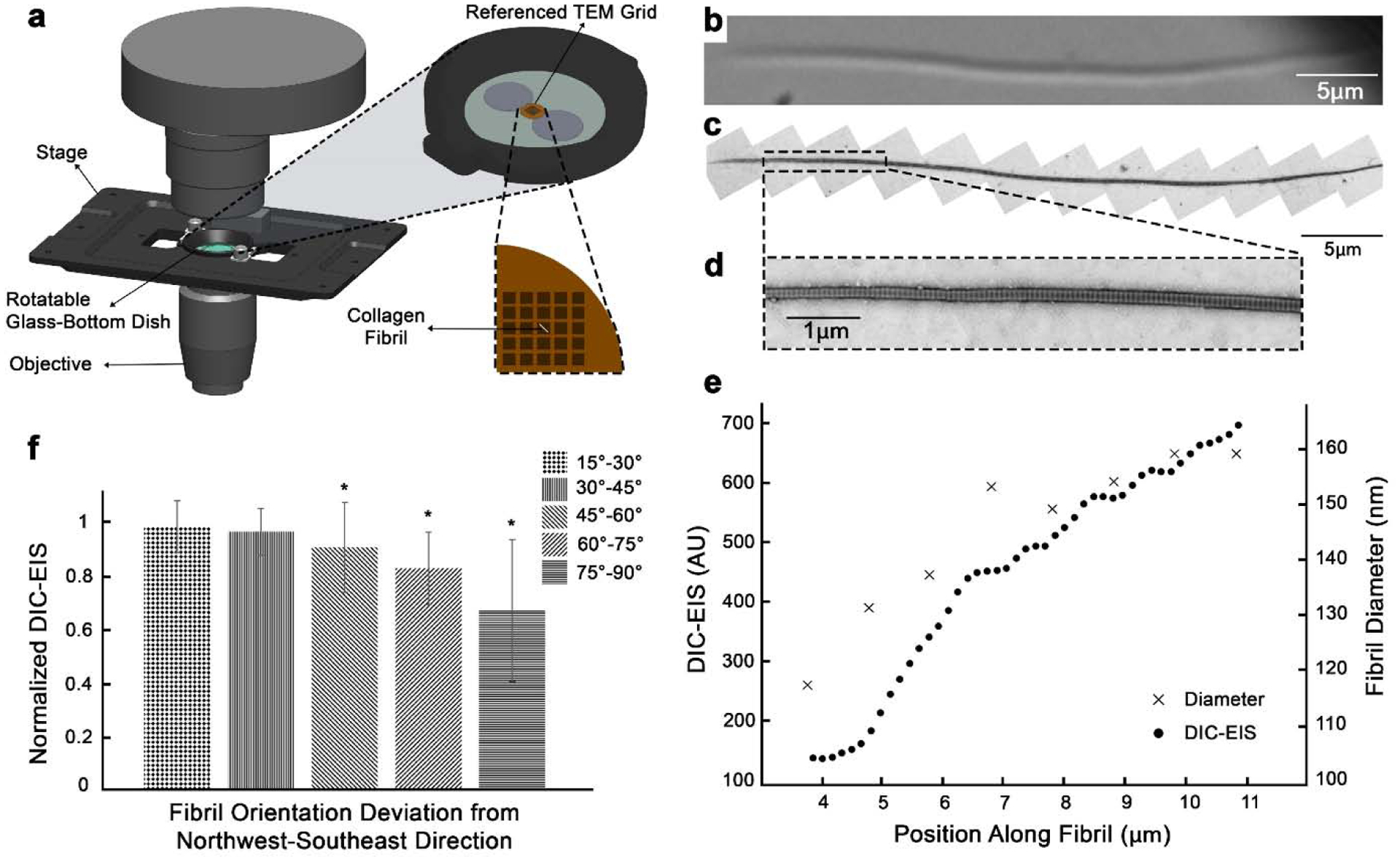

TEM microscopy was performed to measure the sensitivity of DIC-EIS to fibril diameter variation. Figure 2 shows the experimental setup (Fig. 2a), DIC (Fig. 2b) and TEM (Fig. 2c and 2d) images of a representative fibril. Measured diameters from these TEM images and their corresponding DIC-EIS are shown in Fig. 2e along the fibril section. Figure 2e clearly demonstrates that DIC-EIS is sensitive to fibril diameter variation along the same fibril. However, the numerical results of DIC-EIS in our experimental setup were not comparable between fibrils. This inconsistency was thought to be due to local distortion of formvar layer after fibril deposition which could alter the DIC-EIS signal.

Fig. 2.

TEM-DIC correlation shows the sensitivity of DIC-EIS to collagen fibril diameter and direction. (a) The experimental setup where collagen fibrils were air-dried on a referenced TEM grid and imaged with DIC microscopy. (b) DIC image of a representative fibril. Note that this image has been rotated. (c) TEM image of the same fibril in (b). (d) High magnification of a selected region of the fibril with a rapid diameter change. (e) Variation of DIC-EIS and diameter along the selected region in (d). The x-axis represents position along the fibril starting from the left side of the fibril. (f) Change of DIC-EIS as a function of fibril direction (n = 35 fibrils). An asterisk indicates significant difference to 0°−15° group (t-test, p < 0.05).

3.2. DIC-EIS is minimally affected by small changes in fibril direction

Theoretically the maximum edge intensity happens when the fibrils are oriented in northwest-southeast direction (perpendicular to the shear axis; Fig. 1a and 1b). It is possible to rotate the fibrils or the DIC prism (Arnison et al., 2004; Danz and Gretscher, 2004; Fabre et al., 2009) in order to achieve this maximum edge intensity. However, it is not always practical to image fibrils at this favorable angle. This can take considerable time and would not be suitable for imaging in live systems. Thus, we investigated the sensitivity of the DIC-EIS to fibril direction, while fibrils were rotated up to 90° away from northwest-southeast direction. As the angle of fibril increased, the change in DIC-EIS was more pronounced, lowering the DIC-EIS by 2%, 4%, 10%, 18%, and 34% for fibrils 15°−30°, 30°−45° ,45°−60°, 60°−75°, and 75°−90° deviated from the northwest-southeast direction, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2f, the DIC-EIS was not significantly altered for fibrils up to 45° deviated from the northwest-southeast direction. Data is normalized to max DIC-EIS values (fibrils deviated 0°−15° from the northwest-southeast direction).

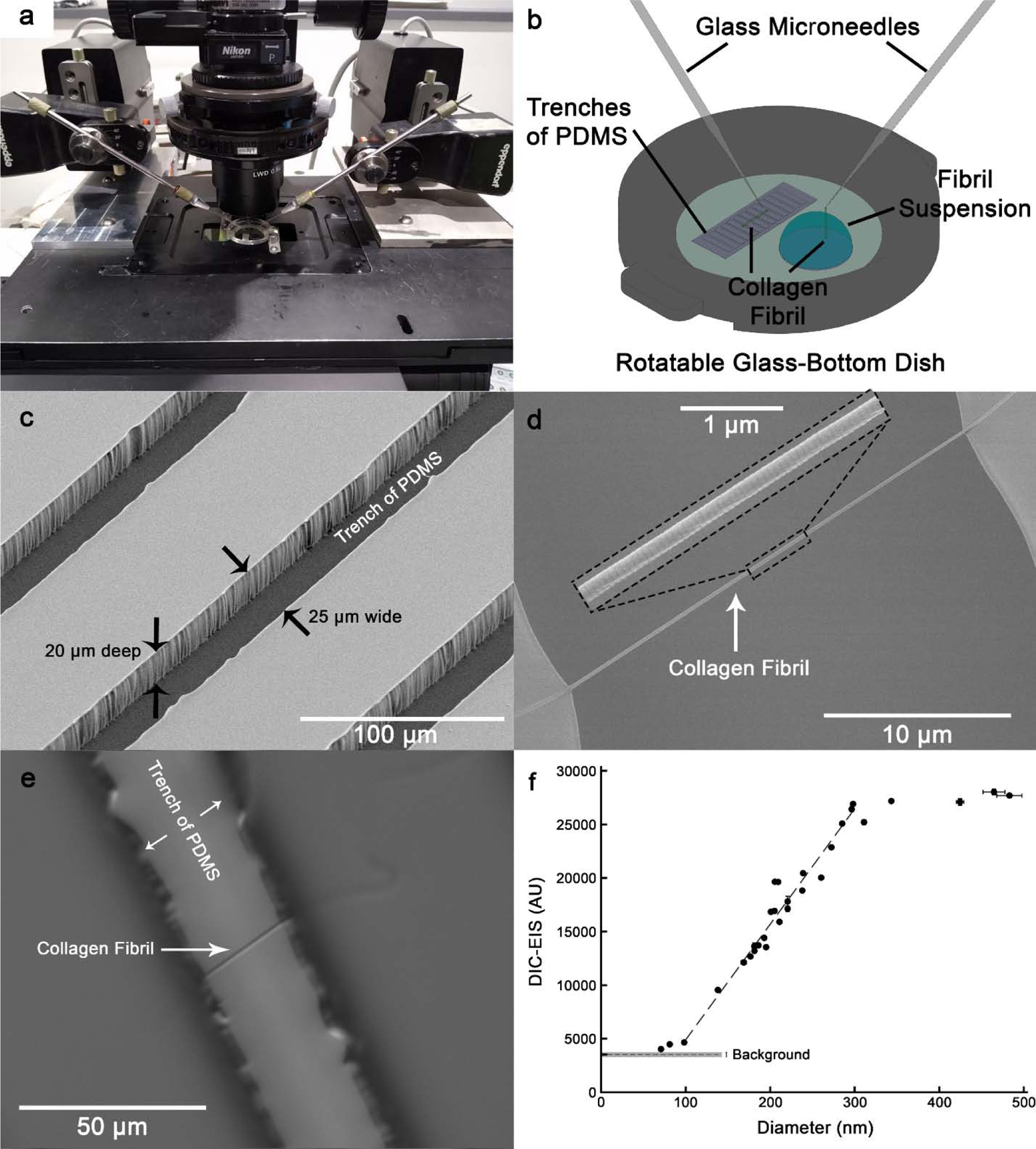

3.3. DIC-EIS is linearly correlated to collagen fibril diameter

Our goal was to calculate fibril diameter directly from DIC images. To overcome the inconsistency of DIC-EIS values of fibrils on TEM grids, fibrils were placed over trenches of PDMS to be imaged with SEM and DIC microscopy (Fig. 3). The DIC-EIS and fibril diameter from SEM images were positively correlated (r = 0.97) for fibrils with a diameter between ~100 to ~300 nm (n = 23 fibrils). Figure 3f shows this linear region. Using this linear curve, fibril diameters could be estimated with ±11 nm accuracy. DIC-EIS was insensitive to diameter variation for fibrils larger than 300 nm and smaller than 100 nm. Note that due to the high energy of the focused beam of electrons, fibrils often broke when SEM images were captured repeatedly from the same fibril section. Therefore, each fibril was imaged only once. Consequently, data points on Fig. 3f are shown with no error bars in the horizontal direction. Also, the standard deviations of DIC-EIS data (148 AU in average) were too small to be shown on the figure.

Fig. 3.

Linear correlation between fibril diameter from SEM images and DIC-EIS. (a) The microscope stage equipped with micromanipulators. (b) Schematic showing method of pulling collagen fibrils out of fibril suspension using microneedles and placement of fibrils over trenches of PDMS. (c) SEM image of trenches of PDMS. (d) SEM image of a fibril over the 25 μm wide gap. The middle section of the fibril is shown at high magnification. (e) DIC image of the same fibril as shown in (d). Note that the fibril was imaged perpendicular to the shear axis, but it is shown in a different orientation for comparison with the SEM image in (d). (f) DIC-EIS as a function of diameter (n = 30 fibrils). A linear region can be seen for fibrils with diameter between ~100 nm to ~300 nm (n = 23 fibrils). Note that diameter values are measurements of dehydrated fibrils with 5 nm platinum coating.

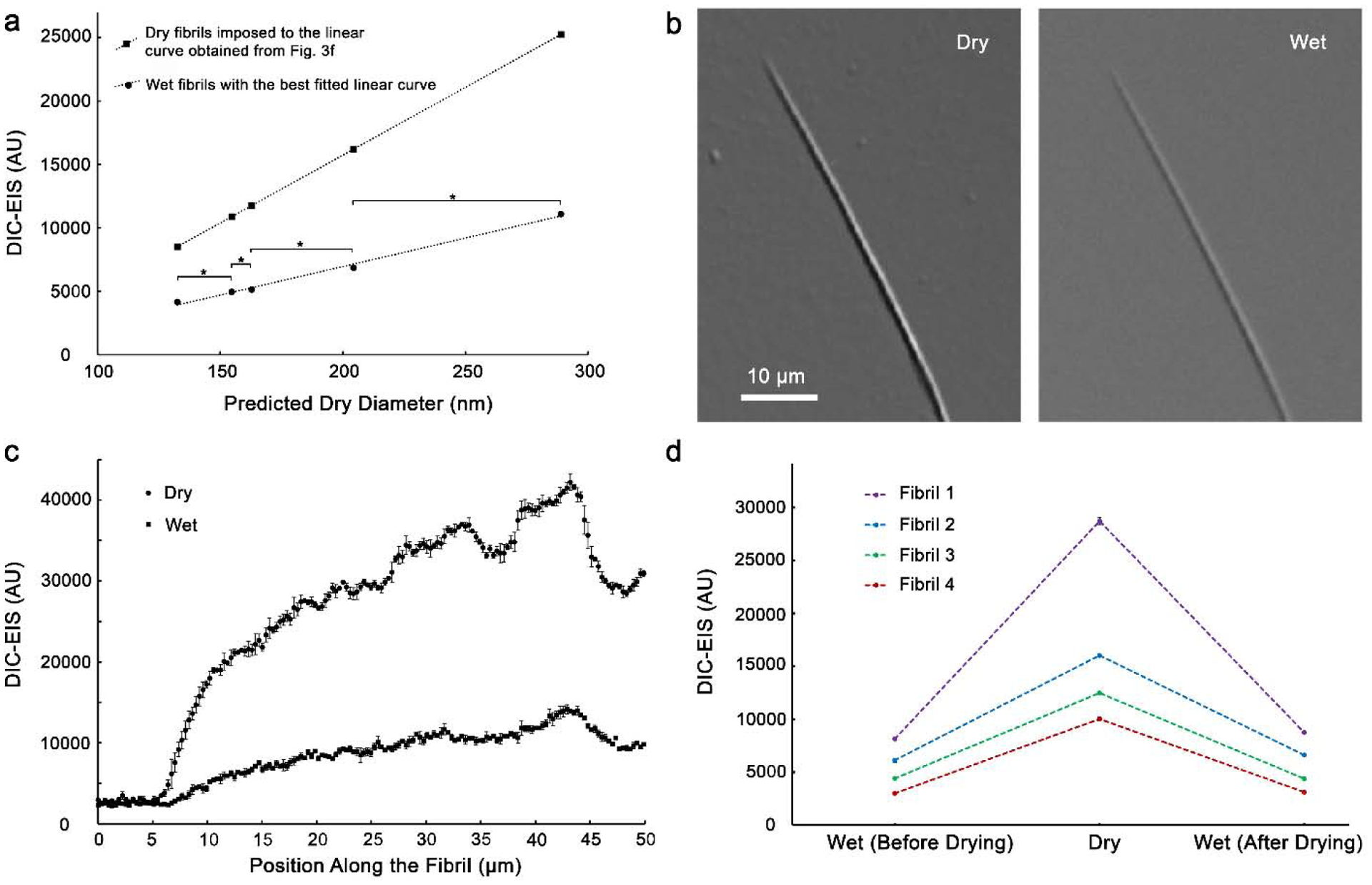

3.4. DIC-EIS is capable of live measurements of hydrated fibrils

The principal value of this method is its ability to look at live measurements. Therefore, we correlated the dry to the wet DIC-EIS signal. Five fibrils were imaged in the dehydrated condition with predicted diameters of 133, 155, 163, 204, and 289 nm (Fig. 4a; diameter of fibrils was predicted based on the linear correlation that was found in Fig. 3f). After addition of PBS, DIC-EIS of all five wet fibrils were significantly different from one another (t-test, p < 0.05) and showed a positive correlation (r = 0.99) to fibril diameter (Fig. 4a). Using this linear curve, fibril diameters could be estimated with approximately ±4 nm accuracy which corresponds to a sensitivity of ~two layers of monomers on the fibril. Furthermore, DIC-EIS of wet fibrils did not significantly change after 10 minutes, 30 minutes, 2 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, and 2 days (ANOVA test, p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of DIC-EIS for wet and dry fibrils. (a) DIC-EIS of fibrils in PBS were also linearly correlated to fibril diameters. Using this linear curve, fibril diameters could be estimated with ±4 nm accuracy. Y-axis error bars were smaller than 53 AU leading to less than ±2 nm uncertainty in predicted diameter (too small to show on the figure). The brackets with asterisks indicate that two consecutive points are significantly different (t-test, p < 0.05). (b) DIC images of a typical fibril in dry and wet conditions on glass. (c) DIC-EIS of the fibril shown in (b). (d) Reversible DIC-EIS of fibrils after air drying on glass. The standard deviations of DIC-EIS data (109 AU in average) are too small to be seen on the figure.

3.5. DIC-EIS shows a reversible diameter change due to dehydration

DIC-EIS of fibrils on glass was used to investigate the reversibility of fibril diameter change after dehydration. Figure 4b shows DIC images of a typical fibril in dry and wet conditions with the same exposure time. Figure 4c shows the sensitivity of DIC-EIS to diameter change for the fibril shown in Fig. 4b. Paired sample t-test (p < 0.05) showed a reversible diameter change after drying and rehydration of fibrils; the DIC-EIS of rehydrated fibrils after air drying changed less than 10% compared to the DIC-EIS of fibrils before drying (Fig. 3d).

4. Discussion

A simple and powerful tool to measure absolute collagen fibril diameter from DIC-EIS has been presented. The method is suitable for extracting information from fibrils with dry diameters between ~100 nm to ~300 nm. Above 300 nm, the final image has separated intensity amplitude shifts along the shear axis. As the fibril diameter increases, amplitude shifts become more separated but their intensity values stay unchanged. For these relatively thick fibrils, diameters can be determined using conventional imaging techniques (Fig. 1c). Below 300 nm, the final image has superimposed intensity amplitude shifts (Fig. 1d). We showed that DIC-EIS linearly decreases as fibril diameter decreases from 300 nm to 100 nm (Fig. 3f). The lower limit of detection (100 nm) is dictated by the size of the DIC point-spread function, which depends on the numerical aperture of the objective and the amount of shear in the Wollaston prisms. The lower limit is inversely proportional to the numerical aperture and can be decreased by using a higher NA objective. In this investigation, we used a simple 40x long working distance objective with a relatively low NA (0.6) for convenience. Working with a more powerful objective (e.g. 60x Plan Apo 1.4 NA oil-immersion) it is possible to substantially decrease the lower limit of detection and improve the measurement accuracy by more than a factor of two, placing the DIC-EIS detection limit on par with SHG (~40 nm) but with a much lower variance. Nonetheless, our data suggest that quantitative studies of dynamic collagen fibril assembly, degradation and growth can be performed on a relatively simple microscope with DIC and a 40x LWD objective. While previously it was necessary to apply a secondary method to obtain fibril diameter (Paten et al., 2019), using this method direct DIC microscopy can be used to measure fibril diameter without the need to fix, stain, or label the fibril, permitting the study of dynamic changes on the same fibril over long periods.

It is important to note that the DIC signal is sensitive to changes in experimental setup when the optical path is altered (e.g. changes in the index of refraction of fibril milieu, wavelength of light (Choo et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2009), light exposure time, filters, and objective). However, given the general linearity in the DIC-EIS vs diameter curve it can be easily calibrated with a few reference fibrils. When working in air, it is necessary to consider the water content of the fibrils, since it has been shown that the fibril diameter increases with hydration (Sayers et al., 1982). Fratzl and Daxer have suggested a two-stage drying model for collagen fibrils in the corneal stroma in which first, water is removed from interfibrillar substance (mostly proteoglycans) and second, complete drying happens by removing water from inside the fibril (Fratzl and Daxer, 1993). This suggests that fibril associated water is bound relatively strongly and that it affects the fibril diameter. Measurements from electron microscopy of wet frozen (Craig et al., 1986) corneas and X-ray studies of hydrated corneas (Worthington and Inouye, 1985) showed a ~45% increase of diameter compared to dehydrated fibrils (Craig and Parry, 1981). Another X-ray diffraction study of cornea showed ~40% increase of fibrils diameters on hydration (Meek et al., 1991). We imaged dried and hydrated fibrils and showed that in both conditions, DIC-EIS is linearly correlated to the fibril diameter. We also showed that DIC-EIS of hydrated fibrils were not changed over two days. These collagen fibrils were trypsin extracted (Liu et al., 2016) from bovine sclera and previously showed no proteoglycan content.

As is well-known, the DIC signal is sensitive to fibril orientation showing maximum edge intensity when fibrils are oriented at 45° to the polarization axes (the northwest-southeast direction), and thus perpendicular to the shear direction. However, our data show that the DIC-EIS of fibrils oriented in different directions has an effect that is small at small angles and that the effect can be calibrated. The signal depends on the directional derivative of the phase, which varies with the cosine of the angle, which varies slowly at small angles, in agreement with this observation.

Fibril cross section shape needs to be considered carefully. We took our measurements on fibrils that were on glass, on formvar layer of TEM grids, or stretched across trenches in a PDMS substrate. In the latter case, we could expect no surface effects on our measurements. However, it has been shown that fibrils can flatten when they are adhered to surfaces (Svensson et al., 2012). Flattening will strongly affect the measurements of DIC-EIS through three mechanisms: 1) The edge-to-edge distance will increase, 2) The presence of the second interface can change the gradient in the index of refraction, and 3) the phase is equal to the integral of the index of refraction along the path of propagation. While, DIC-EIS signals can be obtained from surface adhered fibrils, it is likely that there will be substantial shifting of the DIC-EIS/diameter curve.

5. Conclusions

Using DIC microscopy, we have demonstrated a powerful, simple optical method that can determine collagen fibril diameters well below the wavelength of light and with uncertainly levels not obtainable with any other optical system. The approach enables investigation of collagen fibril assembly, growth and degradation kinetics in real time and under physiological conditions without requiring labelling.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jeffrey Paten and William Fowle for their help with electron microscopy imaging; Pooyan Tirandazi and Carlos Hidrovo for their help with preparation of PDMS sheets. This study was funded by NIH R21 EY029167.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Allen RD, Allen NS, Travis JL, 1981. Video-enhanced contrast, differential interference contrast (AVEC-DIC) microscopy: a new method capable of analyzing microtubule-related motility in the reticulopodial network of Allogromia laticollaris. Cell Motil 1, 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragno I, Odetti P, Altamura F, Cavalleri O, Rolandi R, 1995. Structure of rat tail tendon collagen examined by atomic force microscope. Experientia 51, 1063–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnison MR, Larkin KG, Sheppard CJR, Smith NI, Cogswell CJ, 2004. Linear phase imaging using differential interference contrast microscopy. J Microsc-Oxford 214, 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr G, 1950. The reconstitution of collagen fibrils as revealed by electron microscopy. Experimental Cell Research 1, 603–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bancelin S, Aime C, Gusachenko I, Kowalczuk L, Latour G, Coradin T, Schanne-Klein MC, 2014. Determination of collagen fibril size via absolute measurements of second-harmonic generation signals. Nat Commun 5, 4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselt DR, Revel JP, Baldeschwieler JD, 1993. Subfibrillar structure of type I collagen observed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J 65, 2644–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhole AP, Flynn BP, Liles M, Saeidi N, Dimarzio CA, Ruberti JW, 2009. Mechanical strain enhances survivability of collagen micronetworks in the presence of collagenase: implications for load-bearing matrix growth and stability. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 367, 3339–3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birk DE, Trelstad RL, 1986. Extracellular compartments in tendon morphogenesis: collagen fibril, bundle, and macroaggregate formation. J Cell Biol 103, 231–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boote C, Dennis S, Newton RH, Puri H, Meek KM, 2003. Collagen fibrils appear more closely packed in the prepupillary cornea: optical and biomechanical implications. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44, 2941–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boote C, Kamma-Lorger CS, Hayes S, Harris J, Burghammer M, Hiller J, Terrill NJ, Meek KM, 2011. Quantification of collagen organization in the peripheral human cornea at micron-scale resolution. Biophys J 101, 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff EAG, Chernoff DA, 1992. Atomic Force Microscope Images of Collagen-Fibers. J Vac Sci Technol A 10, 596–599. [Google Scholar]

- Choo P, Hryn AJ, Culver KS, Bhowmik D, Hu JT, Odom TW, 2018. Wavelength-Dependent Differential Interference Contrast Inversion of Anisotropic Gold Nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 122, 27024–27031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchi R, Vogler N, Kapsokalyvas D, Dietzek B, Popp J, Pavone FS, 2013. From molecular structure to tissue architecture: collagen organization probed by SHG microscopy. J Biophotonics 6, 129–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IC, 1974. Articular cartilage: a review and scanning electron microscope study. II. The territorial fibrillar architecture. J Anat 118, 261–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox G, Kable E, 2006. Second-harmonic imaging of collagen. Methods Mol Biol 319, 15–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AS, Parry DA, 1981. Collagen fibrils of the vertebrate corneal stroma. Journal of ultrastructure research 74, 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AS, Robertson JG, Parry DA, 1986. Preservation of corneal collagen fibril structure using low-temperature procedures for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Mol Struct Res 96, 172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danz R, Gretscher P, 2004. C-DIC: a new microscopy method for rational study of phase structures in incident light arrangement. Thin Solid Films 462, 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Daxer A, Misof K, Grabner B, Ettl A, Fratzl P, 1998. Collagen fibrils in the human corneal stroma: structure and aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39, 644–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom M, Yurke B, 1997. Measurement of the force-velocity relation for growing microtubules. Science 278, 856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer RF, Enna CD, 1976. Ultrastructural features of adult human tendon. Cell Tissue Res 168, 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikenberry E, Brodsky B, Parry D, 1982a. Collagen fibril morphology in developing chick metatarsal tendoms: 1. X-ray diffraction studies. Int J Biol Macromol 4, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Eikenberry E, Brodsky B, Craig A, Parry D, 1982b. Collagen fibril morphology in developing chick metatarsal tendon: 2. Electron microscope studies. Int J Biol Macromol 4, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fabre L, Inoue Y, Aoki T, Kawakami S, 2009. Differential interference contrast microscope using photonic crystals for phase imaging and three-dimensional shape reconstruction. Appl Optics 48, 1347–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint MH, Craig AS, Reilly HC, Gillard GC, Parry DA, 1984. Collagen fibril diameters and glycosaminoglycan content of skins--indices of tissue maturity and function. Connect Tissue Res 13, 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn B 2012. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations on the Mechanical Stabilization and Enzymatic Degradation of Collagen, In Ruberti JW, et al. , (eds.). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fratzl P, Daxer A, 1993. Structural transformation of collagen fibrils in corneal stroma during drying. An x-ray scattering study. Biophysical journal 64, 1210–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Oh S, Choi W, Yamauchi T, Dorn A, Yaqoob Z, Dasari RR, Feld MS, 2010. Quantitative DIC microscopy using an off-axis self-interference approach. Opt Lett 35, 2370–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullwood NJ, Hammiche A, Pollock HM, Hourston DJ, Song M, 1995. Atomic force microscopy of the cornea and sclera. Curr Eye Res 14, 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale M, Pollanen MS, Markiewicz P, Goh MC, 1995. Sequential assembly of collagen revealed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J 68, 2124–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge-Ge Q, Wen-Hui L, Jia-Chao X, Xiao-Long K, Rong Z, Fang L, Xiao-Hong F, 2017. Development of integrated atomic force microscopy and fluorescence microscopy for single-molecule analysis in living cells. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry 45, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Goh KL, Hiller J, Haston JL, Holmes DF, Kadler KE, Murdoch A, Meakin JR, Wess TJ, 2005. Analysis of collagen fibril diameter distribution in connective tissues using small-angle X-ray scattering. Biochim Biophys Acta 1722, 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow JM, Elliott GF, Woolgar AE, 1978. X-ray diffraction studies of the corneal stroma. J Mol Biol 119, 237–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Schmitt FO, 1948. The structure of human skin collagen as studied with the electron microscope. J Exp Med 88, 555–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Highberger JH, Schmitt FO, 1954. Collagen Structures Considered as States of Aggregation of a Kinetic Unit. The Tropocollagen Particle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 40, 679–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama H, Yamamuro T, Takeda T, 1976. Experimental studies on connective tissue of the capsular ligament. Influences of aging and sex hormones. Acta Orthop Scand 47, 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch JJ, Lipke PN, Beaussart A, El Kirat Chatel S, Dupres V, Alsteens D, Dufrene YF, 2012. Atomic force microscopy - looking at mechanosensors on the cell surface. J Cell Sci 125, 4189–4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DF, Tait A, Hodson NW, Sherratt MJ, Kadler KE, 2010. Growth of collagen fibril seeds from embryonic tendon: fractured fibril ends nucleate new tip growth. J Mol Biol 399, 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Takeda T, 1975. Three-dimensional observation of collagen framework of lumbar intervertebral discs. Acta Orthop Scand 46, 949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Kodama T, Fujita T, 1969. Scanning electron microscopy of normal and rheumatoid articular cartilages. Arch Histol Jpn 30, 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili JN, 2011. Intermolecular and surface forces. 3rd ed. Academic Press, Burlington, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DS, Fessler JH, 1955. Isolation and properties of a collagen soluble in salt solution at neutral pH. Nature 176, 69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, Arnal I, Desai A, Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, 2001. Reconstitution of physiological microtubule dynamics using purified components. Science 294, 1340–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi L, Ruggeri A, Roveri N, Bigi A, Reale E, 1983. Light microscopy, electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction analysis of glycerinated collagen fibers. J Ultrastruct Res 85, 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CP, Douglas WH, Erlandsen SL, 1993. Scanning electron microscopy of type I collagen at the dentin-enamel junction of human teeth. J Histochem Cytochem 41, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Andarawis-Puri N, Eppell SJ, 2016. Method to extract minimally damaged collagen fibrils from tendon. J Biol Methods 3, e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz V, Sattler M, Gallinat S, Wenck H, Poertner R, Fischer F, 2012. Impact of collagen crosslinking on the second harmonic generation signal and the fluorescence lifetime of collagen autofluorescence. Skin Res Technol 18, 168–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, Leonard DW, 1993. Ultrastructure of the corneal stroma: a comparative study. Biophys J 64, 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, Quantock AJ, 2001. The use of X-ray scattering techniques to determine corneal ultrastructure. Prog Retin Eye Res 20, 95–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, Fullwood NJ, Cooke PH, Elliott GF, Maurice DM, Quantock AJ, Wall RS, Worthington CR, 1991. Synchrotron x-ray diffraction studies of the cornea, with implications for stromal hydration. Biophysical journal 60, 467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller D, Peters K, Meller K, 1997. Human cornea and sclera studied by atomic force microscopy. Cell Tissue Res 288, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michna H, 1984. Morphometric analysis of loading-induced changes in collagen-fibril populations in young tendons. Cell Tissue Res 236, 465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T, 1970. Collagen framework of human articular cartilage studied by the replica method and scanning electron microscopy. Arch Histol Jpn 32, 215–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry DA, Craig AS, 1977. Quantitative electron microscope observations of the collagen fibrils in rat-tail tendon. Biopolymers 16, 1015–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry DA, Barnes GR, Craig AS, 1978. A comparison of the size distribution of collagen fibrils in connective tissues as a function of age and a possible relation between fibril size distribution and mechanical properties. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 203, 305–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paten JA, Martin CL, Wanis JT, Siadat SM, Figueroa-Navedo AM, Ruberti JW, Deravi LF, 2019. Molecular Interactions between Collagen and Fibronectin: A Reciprocal Relationship that Regulates De Novo Fibrillogenesis. Chem 5, 2126–2145. [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano PP, Vanderby R Jr., 2006. Collagen fibril morphology and organization: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biol 25, 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenko I, Sommer F, Minh DT, Garrone R, Franc JM, 1994. Atomic force microscopy study of the collagen fibre structure. Biol Cell 80, 67–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon ED, 1995. Ve-Dic Light-Microscopy and the Discovery of Kinesin. Trends in Cell Biology 5, 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers Z, Koch MH, Whitburn SB, Meek KM, Elliott GF, Harmsen A, 1982. Synchrotron x-ray diffraction study of corneal stroma. J Mol Biol 160, 593–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starborg T, Kalson NS, Lu Y, Mironov A, Cootes TF, Holmes DF, Kadler KE, 2013. Using transmission electron microscopy and 3View to determine collagen fibril size and three-dimensional organization. Nat Protoc 8, 1433–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Wang GF, Fang N, Yeung ES, 2009. Wavelength-Dependent Differential Interference Contrast Microscopy: Selectively Imaging Nanoparticle Probes in Live Cells. Anal Chem 81, 9203–9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Sakai N, Yoshida A, Uekusa Y, Yagi A, Imaoka Y, Ito S, Karaki K, Takeyasu K, 2013. High-speed atomic force microscopy combined with inverted optical microscopy for studying cellular events. Sci Rep 3, 2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson RB, Herchenhan A, Starborg T, Larsen M, Kadler KE, Qvortrup K, Magnusson SP, 2017. Evidence of structurally continuous collagen fibrils in tendons. Acta Biomater 50, 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson RB, Hansen P, Hassenkam T, Haraldsson BT, Aagaard P, Kovanen V, Krogsgaard M, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP, 2012. Mechanical properties of human patellar tendon at the hierarchical levels of tendon and fibril. J Appl Physiol 112, 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM, Zipfel WR, Webb WW, 2005. Interpreting second-harmonic generation images of collagen I fibrils. Biophys J 88, 1377–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington CR, Inouye H, 1985. X-Ray-Diffraction Study of the Cornea. International journal of biological macromolecules 7, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Hitomi J, Shigeno M, Sawaguchi S, Abe H, Ushiki T, 1997. Atomic force microscopic studies of isolated collagen fibrils of the bovine cornea and sclera. Arch Histol Cytol 60, 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareian R, Susilo ME, Paten JA, McLean JP, Hollmann J, Karamichos D, Messer CS, Tambe DT, Saeidi N, Zieske JD, Ruberti JW, 2016. Human Corneal Fibroblast Pattern Evolution and Matrix Synthesis on Mechanically Biased Substrates. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 1204–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoumi A, Yeh A, Tromberg BJ, 2002. Imaging cells and extracellular matrix in vivo by using second-harmonic generation and two-photon excited fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 11014–11019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]