Abstract

Beginning in 1992, a sustained outbreak of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections was noted in our 1,000-bed hospital in Barcelona, Spain, resulting in considerable overuse of imipenem, to which the organisms were uniformly susceptible. In January 1997, carbapenem-resistant (CR) A. baumannii strains emerged and rapidly disseminated in the intensive care units (ICUs), prompting us to conduct a prospective investigation. It was an 18-month longitudinal intervention study aimed at the identification of the clinical and microbiological epidemiology of the outbreak and its response to a multicomponent infection control strategy. From January 1997 to June 1998, clinical samples from 153 (8%) of 1,836 consecutive ICU patients were found to contain CR A. baumannii. Isolates were verified to be A. baumannii by restriction analysis of the 16S-23S ribosomal genes and the intergenic spacer region. Molecular typing by repetitive extragenic palindromic sequence-based PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis showed that the emergence of carbapenem resistance was not by the selection of resistant mutants but was by the introduction of two new epidemic clones that were different from those responsible for the endemic. Multivariate regression analysis selected those patients with previous carriage of CR A. baumannii (relative risk [RR], 35.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 7.2 to 173.1), those patients who had previously received therapy with carbapenems (RR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.3 to 15.6), or those who were admitted into a ward with a high density of patients infected with CR A. baumannii (RR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.5) to be at a significantly greater risk for the development of clinical colonization or infection with CR A. baumannii strains. In accordance, a combined infection control strategy was designed and implemented, including the sequential closure of all ICUs for decontamination, strict compliance with cross-transmission prevention protocols, and a program that restricted the use of carbapenem. Subsequently, a sharp reduction in the incidence rates of infection or colonization with A. baumannii, whether resistant or susceptible to carbapenems, was shown, although an alarming dominance of the carbapenem-resistant clones was shown at the end of the study.

Initial concern about multiresistant, carbapenem-resistant (CR) Acinetobacter baumannii infections began when the first hospital-wide outbreak occurred in New York City in 1991 (31, 69). Since then, reports of CR A. baumannii have been accumulating from other parts of the world, such as Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Cuba, England, France, Hong Kong, Kuwait, Singapore, and Spain (3, 9, 10, 22, 53, 66). Currently, the spread of hospital populations of resistant microorganisms is of great concern worldwide, raising the idea that we may be approaching the postantimicrobial era (2, 4, 16, 33, 52, 68). Although methicillin-resistant staphylococci and vancomycin-resistant enterococci have been the focus of much of this attention to date (32, 39, 46, 48, 54, 78), in recent years, emerging gram-negative organisms such as A. baumannii have provided the same challenge with regard to multiple-antibiotic resistance (7, 8, 21, 38, 55, 72, 73).

In September 1992, an outbreak of infections due to multiresistant A. baumannii began in the intensive care units (ICUs) of our institution. Although infection control measures based on strict barrier precautions were instituted, A. baumannii spread throughout the hospital. Since then, more than 1,400 patients have been colonized or infected, 60 to 70% of them during an ICU stay. The incidence rates of new colonized or infected patients ranged from 6.3 cases/100 ICU admissions in 1992 to 14 cases/100 ICU admissions in 1996. Currently, A. baumannii constitutes the most common cause of infection among ICU patients. Numerous efforts were conducted in our institution to investigate the epidemiology of the outbreak (5, 18, 20). Results indicated that colonized patients and environmental contamination might act as the major epidemiological reservoirs for infection. Inadequate prevention of cross-transmission is the main determinant for A. baumannii persistence. Control measures were repeatedly reinforced during this time, but only a transitory decrease in the incidence of A. baumannii infection or colonization was observed following each reinforcement.

From 1992 to 1996, annual susceptibility summaries showed that all A. baumannii epidemic or endemic isolates were resistant to two or more antibiotic groups, which uniformly included β-lactams and gentamicin, and were susceptible only to carbapenems, sulbactam, and colistin. However, on the basis of the variable susceptibilities to tobramycin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline, three major antibiotic susceptibility patterns among the A. baumannii population could be defined. Continued surveillance of A. baumannii isolates by molecular typing procedures showed three main clonal types that corresponded to the three major antibiotic susceptibility patterns detected during the outbreak: clone A, 71%; clone B, 7%; clone C, 14%; and sporadic clones, 8% (M. A. Dominguez, J. Ayats, C. Ardanuy, X. Corbella, J. Liñares, and R. Martin, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. K-124, 1998). During this time, although yearly total antibiotic consumption decreased following a vigorous antibiotic use policy (from 60 daily definite doses [DDDs]/100 ICU hospitalization days in 1992 to 49.9 DDDs/100 ICU hospitalization days in 1996), the inability to control the outbreak indicated that the use of imipenem, the only recognized antibiotic alternative for treatment of infections, remained high, from 12.8 (21.3%) to 13.2 (26.5%) DDDs/100 ICU hospitalization days.

On January 4, 1997, a 75-year-old man who was admitted to our hospital with extensive cerebral infarction developed aspirate pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation and ICU admission. Imipenem at 500 mg every 6 h was started, but the pneumonia progressed after 9 days of treatment. Respiratory specimens obtained by fiberoptic bronchoscopy with a protected specimen brush yielded A. baumannii with intermediate resistance to imipenem (MIC, 8 mg/liter). On day 12, the imipenem dosage was increased to 1 g every 6 h, but the patient died 24 h later. After that time, carbapenem resistance among A. baumannii isolates rapidly spread throughout the ICUs, prompting us to conduct a prospective investigation.

The emergence and spread of carbapenem resistance were managed from a combined laboratory-epidemiology point of view. Our aims were to identify the complexity of factors contributing to the clinical and microbiological epidemiology of such infections and to determine the effectiveness of a combination of infection control strategies.

(The work was presented in part at the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 24 to 27 September 1998, San Diego, Calif.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

(i) Setting. The Hospital de Bellvitge is a 1,000-bed tertiary-care teaching hospital for adults in Barcelona, Spain. It provides acute medical and surgical care to a population of 1.5 million persons, excluding pediatrics, obstetrics, and burns, with about 26,000 patient admissions per year. It has four ICUs, with a total of 46 beds and about 1,200 patient admissions per year. One nurse cares for each two ICU patients; transplant recipients, however, are managed by only one nurse. Selective digestive decontamination is not applied to patients.

(ii) Objectives. The objectives of the study were (i) to identify risk factors for the development of clinical colonization or infection due to CR A. baumannii, (ii) to characterize molecularly the organisms and clones involved, and (iii) to evaluate the efficacy of a multicomponent intervention program.

(iii) Design. The study was an 18-month prospective longitudinal intervention investigation and was centered in the ICUs. From January 1997 to June 1998, all ICU patients harboring A. baumannii in clinical samples entered into a specially designed computer-assisted protocol. During the first 6-month period before intervention (January to June 1997), potential risk factors for the development of CR A. baumannii-positive clinical samples were identified by comparing demographic, clinical, and epidemiological data between CR A. baumannii-positive and carbapenem-susceptible (CS) A. baumannii-positive groups. Since we had observed that the previous carriage of A. baumannii at different body sites, such as the digestive tract, was a major attribute for the subsequent development of A. baumannii-positive clinical samples in our ICU setting (5, 18), rectal swab specimens were prospectively obtained upon ICU admission and weekly thereafter until ICU discharge or death for screening of A. baumannii carriers during this first 6-month study period. According to the risk factors identified, a combination of infection control measures was carefully designed and implemented in the ICUs in July 1997. The response to the intervention was evaluated during the subsequent 12-month period (July 1997 to June 1998) by comparing the incidence rates of new A. baumannii cases of the pre- and postintervention study periods.

Definitions.

CR A. baumannii-positive and CS A. baumannii-positive patients were defined as those patients admitted to the ICUs from whom at least one clinical sample recovered during the ICU stay contained CR or CS A. baumannii (rectal swab specimens were not considered clinical samples). Clinical episodes of colonization or infection were considered acquired in the ICU if they appeared 72 h after ICU admission. Standard Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria were carefully used to define nosocomial infections (28).

Chronic health status was classified into three groups according to the McCabe classification: group 1 includes chronic or curable disease, group 2 includes malignancy or any other disease that results in a life expectancy of less than 5 years, and group 3 includes diseases that result in a life expectancy of less than 1 year (44). The severity of illness was calculated by means of evaluation of the Simplified Acute Physiologic Score (SAPS) measured at ICU admission (40). SAPS is a validated severity-of-disease scoring system that uses age and 13 physiological parameters to generate a score from 0 to 56 by increasing severity of illness.

Immunosuppressed patients included those with nonneoplastic immunosuppressive diseases or those who had used glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or azathioprine in the 2 weeks prior to the first episode of clinical colonization or infection due to A. baumannii. A urinary catheter, intravascular catheterization, parenteral alimentation, mechanical ventilation or tracheostomy, and antibiotic therapy were considered if they had been in use for more than 48 h from ICU admission to the day of the ICU stay that A. baumannii was detected in clinical samples. The term “previous CR A. baumannii carriage” was defined as the presence of CR A. baumannii in one or more fecal samples, before the detection of the first A. baumannii clinical isolate (either CR or CS A. baumannii). The term “concentration of CR A. baumannii-positive patients” was defined as the mean number of patients per day who were known to harbor CR A. baumannii and who were admitted to the same ICU ward during the week before the patient developed the first A. baumannii clinical colonization or infection.

Infection control intervention.

Multicomponent intervention included the sequential closure of all ICUs for extensive decontamination; partial structural redesign of the units with placement of hand-washing facilities within the rooms; continued ICU personnel educational programs; rigorous open surveillance of adequate compliance with barrier precautions, cleaning protocols, and housekeeping procedures; and restriction of carbapenem use. Adequate compliance with the control program was supervised by two specially designated members of the infection control team (one physician and one nurse), who attended to the ICUs daily after the implementation of the intervention program in July 1997. Furthermore, since the ability of A. baumannii to survive in the hospital environment is well known (77), an environmental survey was conducted on the basis of the weekly performance of environmental sampling. A previously reported modification of the swab technique, which involved the use of sterile gauze rather than cotton applicator swabs, was used (20). The focus was on those ICU items that should have been free of contamination under adequate compliance with cleaning procedures and barrier precautions. During the 12-month postintervention study periods, continuous feedback information that comprised data on outbreak evolution, environmental contamination, and carbapenem consumption was provided.

During carbapenem restriction use, a “fourth-generation” cephalosporin (cefepime) or an antipseudomonas penicillin plus a β-lactamase inhibitor (piperacillin-tazobactam), preferably in combination with an aminoglycoside, was recommended as a broad-spectrum empirical regimen for ICU patients. On the basis of both susceptibility tests and previous published experiences (34–36), 1 to 2 g of intravenous sulbactam alone every 6 to 8 h (19), with or without tobramycin, or polymyxin E (colistimethate) administered at recommended doses (12, 37, 74, 80), either parenterally, intrathecally, topically, or aerosolized, was used as an alternative to imipenem against A. baumannii strains, when indicated.

Microbiology procedures.

A. baumannii isolates were identified by the microbiology laboratory by using standard biochemical reactions (24) and its ability to grow at 37, 41, and 44°C. Confirmation of the identification as A. baumannii (either CS or CR A. baumannii) was verified by restriction analysis of the 16S-23S ribosomal genes and the intergenic spacer sequence (27) from representative isolates.

The antibiotic susceptibility of A. baumannii was determined by the microdilution method (MicroScan; NegCombo Type 6I plates; Dade International Inc., West Sacramento, Calif.). Susceptibility to the following antibiotics was determined: ampicillin, ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline. Imipenem resistance was confirmed by the E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) and the agar dilution method. Results were interpreted according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) criteria (51). Susceptibilities to sulbactam and colistin were tested by the disk diffusion method with use of 10/10-μg ampicillin-sulbactam disks and 10-μg colistin disks (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.), and isolates were considered susceptible if the inhibition zones were ≥15 and ≥11 mm, respectively. Sulbactam and colistin MICs were studied by the agar dilution method (50) with Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). The breakpoints for sulbactam were those of NCCLS for ampicillin-sulbactam (51). Breakpoints for colistin were those defined by the French Society for Microbiology (1, 65); thus, isolates were considered susceptible to colistin if the MIC was ≤2 mg/liter.

Since all multiresistant A. baumannii strains, either CR or CS A. baumannii strains, isolated from clinical specimens during the outbreak were uniformly found to be gentamicin resistant, this antibiotic was selected for the screening of rectal and environmental specimens. Rectal swabs and environmental cultures were sampled on MacConkey agar plates (supplemented with 6 μg of gentamicin per ml) and 5% sheep blood agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h.

Molecular typing studies.

Genotyping was performed by the repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (REP-PCR) and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). For the present study we selected 77 CR A. baumannii strains isolated in 1997 from 45 patients. Sixty-one CR A. baumannii isolates were selected from 29 consecutive patients colonized or infected during the first 6-month period before the intervention (January to June 1997); of those isolates, 16 CR A. baumannii strains, were isolated from rectal swabs and 45 were isolated from clinical specimens (respiratory tract, n = 17; blood, n = 7; urine, n = 7; catheter sites, n = 5; and other, n = 9). The remaining 16 clinical strains (respiratory tract, n = 6; blood, n = 2; wound, n = 2; and other, n = 6) belonged to 16 CR A. baumannii-colonized or -infected patients selected at random during the second 6-month period following the intervention (July to December 1997). In addition, five environmental CR A. baumannii strains isolated from ICU items were available for genotyping.

REP-PCR was performed with the primers and under the conditions described elsewhere (71). For PFGE, DNA extraction and purification were carried out as described previously (43, 61). For this analysis, two low-frequency restriction enzymes, SmaI and ApaI, were used separately, following the manufacturer's specifications (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.). DNA restriction fragments were separated in a CHEF-DR III unit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) for 20 h at 200 V, with pulse times ranging from 1 to 30 s when SmaI was used for restriction and from 0.5 to 15 s when ApaI was used for restriction.

Statistical analysis.

Potential risk factors were compared between the CR and CS A. baumannii groups by chi-square, Fisher's exact, or Student's t test, when appropriate. For the purpose of statistical analysis, all those patients who harbored both CR and CS A. baumannii during their ICU stay were considered to be two patients. All variables with a two-tailed P value of ≤0.05 in the univariate analysis were considered statistically significant and were included in logistic regression modeling. Multivariate analysis was done by logistic regression, with significant variables selected by a backward stepwise procedure. To identify differences in the evolution of the outbreak before and after the interventions, the study was divided in three 6-month periods: period 1, preintervention (January to June 1997); period 2, early postintervention (July to December 1997); and period 3, late postintervention (January to June 1998). Temporal trends in incidence rates were evaluated before and after interventions by comparing the mean numbers of new CR- or CS-A. baumannii-colonized or -infected patients per 100 ICU admissions among periods 1, 2, and 3 by using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance and the Mann-Whitney U Wilcoxon Rank Sum W test. The impact of restricted use of carbapenem on the carbapenem resistance trend among periods was analyzed by using linear trend analysis with proportions. Statistical analysis was performed by using the SPSS/PC (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Wash.) and the BMDP (BMDP Statistical Software, Cork, Ireland) statistical packages, and EPI Info software (version 6.04a; CDC, Atlanta, Ga.).

RESULTS

Risk factors for clinical colonization or infection due to CR A. baumannii.

From January to June 1997, 106 (15.7%) of the 676 consecutive patients admitted to the ICUs developed clinical colonization or infection due to multiresistant A. baumannii: 22 (20.7%) due to CR A. baumannii, 67 (63.3%) due to CS A. baumannii, and 17 (16%) due to both CR and CS A. baumannii (Fig. 1). Risk factors were compared between the 39 CR A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients and the 84 CS A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients (Table 1), with no differences in terms of sex, underlying diseases, severity of illness at admission, type of ICU ward, mean number of days in an ICU prior to colonization or infection, and prior number of days with invasive devices or antibiotics being found. In contrast, patients infected or colonized with CR A. baumannii isolates were younger than those infected or colonized with CS A. baumannii isolates and belonged to group 1 of the McCabe classification (chronic or curable diseases) in a significantly greater proportion. Moreover, a higher proportion of CR A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients had undergone major digestive surgery, had received parenteral nutrition or prior therapy with carbapenems, had been admitted into a ward with a high density of CR A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients, and were more frequently previous fecal carriers of CR A. baumannii. Results of the logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 2 and identified the previous state of CR A. baumannii carriage, the previous use of imipenem, and the presence of a higher concentration of CR A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients in the same ICU ward to be the independent risk factors for the development of clinical colonization or infection due to CR A. baumannii.

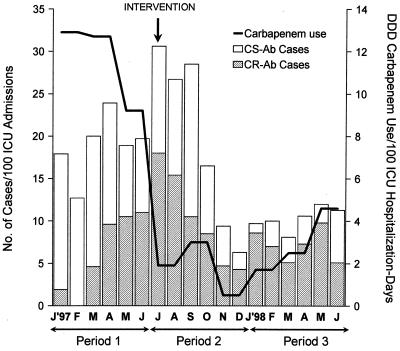

FIG. 1.

Temporal trends in incidence of new patients colonized or infected with CR A. baumannii (CR-Ab) and CS A. baumannii (CS-Ab) and carbapenem consumption from January 1997 to June 1998.

TABLE 1.

Potential risk factors for ICU patients with clinical colonization or infection with CR A. baumannii compared with those for ICU patients with clinical colonization or infection with CS A. baumanniia

| Characteristics | Patients with CR-Ab (n = 39) | Patients with CS-Ab (n = 84) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 48.7 ± 20 | 57.3 ± 18 | 0.02 |

| Male sex (no. [%] of patients) | 29 (74) | 63 (75) | 1.0 |

| Chronic health status (no. [%] of patients) | |||

| McCabe criterion (groups 2 and 3) | 5 (13) | 24 (29) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 7 (18) | 11 (13) | 0.66 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 7 (18) | 20 (24) | 0.46 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (31) | 26 (31) | 0.98 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (3) | 5 (6) | 0.70 |

| Chronic renal failure | 4 (10) | 4 (5) | 0.44 |

| Solid cancer | 3 (8) | 14 (17) | 0.17 |

| Hematologic cancer | 2 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.80 |

| Immunosuppression | 2 (5) | 1 (1) | 0.49 |

| Disease at ICU admission | |||

| SAPS | 12.2 ± 4 | 12.3 ± 4 | 0.90 |

| No. [%] of patients with: | |||

| Polytrauma | 8 (21) | 12 (14) | 0.38 |

| Major digestive surgery | 9 (23) | 8 (10) | 0.04 |

| Cardiopulmonary surgery | 4 (10) | 14 (17) | 0.50 |

| Neurosurgery | 4 (10) | 12 (14) | 0.74 |

| Liver transplantation | 1 (3) | 3 (4) | 1.0 |

| Other | 13 (33) | 33 (41) | 0.21 |

| ICU of admission (no. [%] of patients) | |||

| ICU-A | 10 (26) | 26 (31) | 0.69 |

| ICU-B | 5 (13) | 20 (24) | 0.24 |

| ICU-C | 22 (56) | 37 (44) | 0.27 |

| ICU-D | 2 (5) | 1 (1) | 0.49 |

| Concentration of CR-Ab patients | 2.02 ± 2 | 0.87 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Mean no. of days in ICU prior to isolation | 15.7 ± 16 | 13.9 ± 23 | 0.61 |

| No. (%) of patients with CR-Ab fecal carriage prior to isolation | 16 (52) | 3 (5) | <0.001 |

| Presence of invasive devices (no. [%] of patients) | |||

| Bladder catheter | 39 (100) | 82 (99) | 1.0 |

| Intravascular catheter | 39 (100) | 81 (98) | 0.83 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 19 (49) | 19 (23) | 0.004 |

| Intubation or tracheostomy | 38 (97) | 72 (87) | 0.12 |

| Prior no. of days with invasive devices | |||

| Bladder catheter | 19.9 ± 18 | 15.1 ± 11 | 0.13 |

| Intravascular catheter | 20.8 ± 18 | 15.3 ± 10 | 0.08 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 16.3 ± 9 | 13.1 ± 9 | 0.26 |

| Intubation or tracheostomy | 18.4 ± 17 | 12.9 ± 9 | 0.08 |

| Use of antibiotics prior to isolation (no. [%] of patients) | 39 (100) | 68 (82) | 0.01 |

| Use of carbapenems prior to isolation (no. [%] of patients) | 17 (44) | 9 (11) | <0.001 |

| Prior no. of days with antibiotic therapy | 13.6 ± 10 | 13.3 ± 10 | 0.84 |

| Prior no. of days with carbapenems | 8.4 ± 5 | 10.2 ± 7 | 0.49 |

Plus-or-minus values are means ± standard deviations. Ab, A. baumannii.

TABLE 2.

Multivariate relative risks for potential variables independently associated with infection or colonization with a CR strain

| Potential risk factor | Multivariate analysisa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 0.98 (0.95–1.14) | |

| McCabe criterion (groups 2 and 3) | 0.57 (0.14–2.37) | |

| Major digestive surgery | 1.29 (0.21–7.89) | |

| Parenteral nutrition | 2.34 (0.63–8.62) | |

| Concentration of CR-Abb patients | 1.73 (1.21–2.47) | <0.001 |

| Prior carbapenem use | 4.58 (1.34–15.60) | <0.001 |

| CR-Ab fecal carriage prior to isolation | 35.30 (7.20–173.10) | <0.001 |

RR, relative risk; CI, confidence intervals. Variables with a P value of 0.05 or less by univariate analysis (Table 1) were used in the multivariate model. Subgroup of prior carbapenem use rather than the composite variable of prior antibiotic use was included in the multivariate analysis.

Ab, A. baumannii.

Over the entire 18-month study period, 262 (14%) of a total of 1,836 consecutive patients admitted to our ICUs had clinical samples positive for multiresistant A. baumannii: 109 (42%) due to CS A. baumannii, 102 (39%) due to CR A. baumannii, and 51 (19%) due to both CS and CR A. baumannii (Fig. 1). Of the total of 153 patients from whom clinical samples harbored CR A. baumannii, 90 (59%) met the CDC criteria for infection and 63 (41%) met the CDC criteria for clinical colonization; similarly, 99 (62%) of 160 CS A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients met the CDC criteria for infection. A comparison of the characteristics of patients with CR and CS A. baumannii infections revealed no statistical differences between the groups in terms of sex, age, severity of disease, chronic health status, or prevalence and type of underlying diseases. The clinical characteristics of patients with infections and the mortality rates are shown in Table 3 and do not reveal major differences when patients infected or colonized with CR A. baumannii are compared with those infected or colonized with CS A. baumannii. Intubation-associated respiratory tract infections, catheter-related bacteremia, and surgical wound infections were the most common infections found among members of both groups.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of ICU patients with infection due to CR A. baumannii compared with those with infection due to CS A. baumanniia

| Characteristics | Patients with CR-Ab (n = 90) | Patients with CS-Ab (n = 99) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of infection (no. [%] of patients) | ||

| Tracheobronchitis | 52 (58) | 54 (55) |

| Bacteremiab | 27 (30) | 33 (33) |

| Wound infection | 23 (26) | 21 (21) |

| Pneumonia | 12 (13) | 10 (10) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Catheter-associated ventriculitisc | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 5 (6) | 3 (3) |

| Polymicrobial | 50 (56) | 55 (56) |

| Total no. of days of ICU stay | 32.7 ± 21 | 31.7 ± 26 |

| Total no. of days of hospital stay | 54.9 ± 35 | 50.7 ± 30 |

| Crude mortality rate (no. [%] of patients) | 38 (42) | 50 (51) |

| Mortality at ≤5 days of infection (no. [%] of patients) | 18 (20) | 21 (21) |

Plus-or-minus values are means ± standard deviation. There were no significant differences between the CR and CS A. baumannii (Ab)-infected groups.

Bacteremia was considered secondary to a distant site in three patients in the CR A. baumannii-infected group (wound, n = 2; intra-abdominal infection, n = 1) and in five patients in the CS A. baumannii-infected group (wound, n = 3, soft tissue 1, infection, n = 1; intra-abdominal infection, n = 1).

Data were from a previous report (74).

Microbiology results.

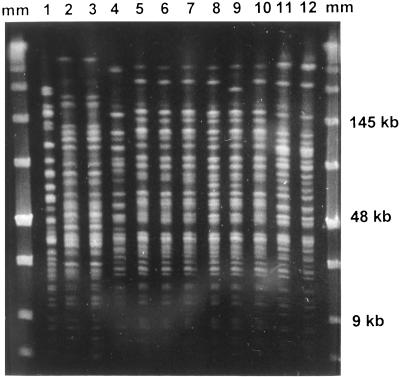

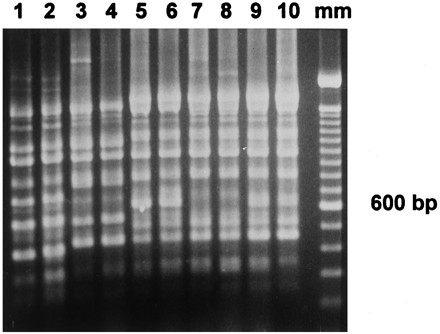

Restriction analysis of the 16S-23S ribosomal operon was performed with representative strains of the CS and CR A. baumannii genotypes found during this study. This analysis confirmed the biochemical results and identified all the strains as belonging to DNA group 2, named A. baumannii. Results of the antibiotic susceptibility tests for the A. baumannii strains isolated during the study period are summarized in Table 4. The antibiotic susceptibility patterns among the CS A. baumannii isolates (susceptible only to carbapenems, sulbactam, and colistin) were consistent with those obtained by PFGE in previous studies (5, 18) and pertained to clone A, the major CS A. baumannii clone isolated during the outbreak. Among CR A. baumannii isolates, we found two antibiotic susceptibility patterns that corresponded to two new A. baumannii genotypes by REP-PCR and PFGE (named D and E). Clone D was susceptible to sulbactam (MIC, 4 mg/liter) and colistin (MIC, ≤0.5 to 1 mg/liter) and was intermediate to tobramycin (MIC, 8 mg/liter) and imipenem (MIC, 8 mg/liter). Imipenem MICs were confirmed both by the E-test and the agar dilution method to avoid false imipenem resistance due to degradation of the drug during storage of the MicroScan panels. Clone E was only susceptible to colistin (MIC, ≤0.5 to 1 mg/liter), intermediate or highly resistant to tobramycin (MIC, 8 to >128 mg/liter), and highly resistant to imipenem (MIC, >32 mg/liter). Neither clone D nor clone E seemed to be related to previous clones isolated during the outbreak (Fig. 2). The results obtained by PFGE reaffirmed those obtained by REP-PCR analysis, which also identified two new clones among the CR A. baumannii strains (Fig. 3).

TABLE 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of A. baumannii clones isolated during the studya

| Antibiotic | MIC (mg/liter)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clone A (CS) | CR clones

|

||

| Clone D | Clone E | ||

| Ticarcillin | 32–>96 | >96 | >96 |

| Piperacillin | >96 | >96 | >96 |

| Sulbactam | 2 | 4 | >64 |

| Ceftazidime | >16 | >16 | >16 |

| Cefepime | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| Imipenem | ≤1 | 8 | >32 |

| Meropenem | ≤4 | >16 | >16 |

| Gentamycin | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Tobramycin | >128 | 8 | 8–>128 |

| Amikacin | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Ciprofloxacin | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| Colistin | <0.5–1 | <0.5–1 | <0.5–1 |

FIG. 2.

Patterns obtained by PFGE for A. baumannii after digestion with SmaI. Lanes 1 to 4, CS isolates belonging to clone A (lane 1), clone B (lanes 2 and 3), and clone C (lane 4); lanes 5 to 12, CR isolates belonging to clone D (lanes 5 to 10) and clone E (lanes 11 and 12); lanes mm, molecular size marker.

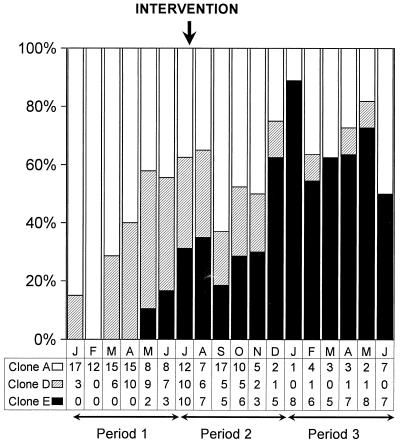

FIG. 3.

Repetitive PCR patterns for A. baumannii. Lanes 1 and 2, CS isolates of clone A; lanes 3 and 4, other CS sporadic clones previously isolated during the endemic; lanes 5 to 10, CR isolates of clone D (lanes 7 and 8) and clone E (lanes 5, 6, 9, and 10); lane mm, 100-bp molecular size marker.

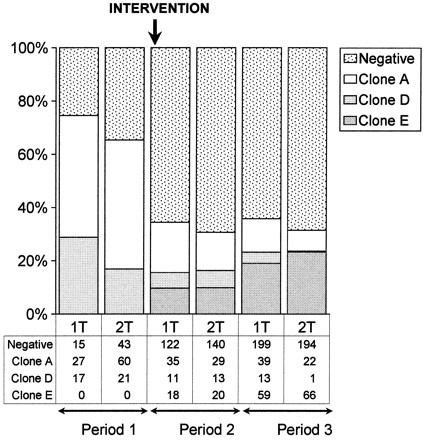

Genotyping of CR A. baumannii isolates from patients colonized or infected during the first 6 months before intervention (January to June 1997) showed a dominance of clone D over clone E: 25 of the 29 patients studied harbored clone D, while the remaining 4 patients harbored clone E. Identical genotypes were found for paired isolates (fecal swabs and clinical samples) from the 16 patients from whom both isolates were available. Among the 16 CR A. baumannii-colonized or -infected patients selected at random during the second period following intervention, clone D was found in 4 patients and clone E was found in 12 patients.

In view of the molecular typing results, the first CR A. baumannii isolate noted to have occurred in January 1997 was a clone D isolate. The first clone E strain was noted to have occurred in May 1997 and was isolated from the urinary tract of a 45-year-old polytraumatic man who had been transferred to our ICU from a hospital in Madrid, where he had been colonized with CR A. baumannii strain with susceptibility pattern identical to that of the clone E strain.

From January 1997 to June 1998, a total of 1,164 cultures of environmental samples were performed, showing a significant decrease in the rates of contamination with either CS or CR A. baumannii after the intervention (Fig. 4). Five of the environmental isolates studied were clone D and clone E isolates (two and three isolates, respectively). These CR A. baumannii strains had the same antibiotypes described for the clinical isolates. On the basis of antibiotic susceptibility, CR A. baumannii environmental isolates had the same clonal distribution throughout the study period as that documented for clinical samples containing CR A. baumannii strains.

FIG. 4.

Temporal trends in environmental contamination with A. baumannii clones before and after interventions.

Response to infection control intervention program.

The incidence rate of new patients with clinical samples positive for CR A. baumannii reached its peak in July 1997, with 18 new CR A. baumannii-positive patients per 100 ICU admissions (Fig. 1). This represented a prevalence of 20 new CR A. baumannii-positive patients, or 60% of all those ICU patients with new clinical isolates that were multiresistant A. baumannii. The implementation of the multicomponent intervention in late July l997 resulted in a sharp reduction in the incidence rate of new A. baumannii infection or colonization, either CR or CS A. baumannii, from 30.6 cases per 100 ICU admissions in that month to 6.3 cases per 100 ICU admissions in December 1997. The incidence rates then remained at a constant, moderate level until the end of the study. The comparison of the mean incidence rates among periods 1, 2, and 3 is shown in Table 5 and indicates a relevant reduction between periods 1 and 3 that reached statistical significance.

TABLE 5.

Temporal trends in incidence of new ICU patients colonized or infected with CR and CS A. baumannii strains: differences before and after interventionsa

| Evolution by period | Patients with CR-Abd | Patients with CS-Ab | All patients (CR-Ab and CS-Ab) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD no. of new cases monthly | |||

| Period 1 (January to June 1997) | 6.2 ± 4.7 | 12.6 ± 3.3 | 18.9 ± 3.6 |

| Period 2 (July to Dec. 97) | 10.2 ± 5.5 | 9.4 ± 5.8 | 19.7 ± 10.4 |

| Period 3 (January to June 1998) | 7.1 ± 1.8 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 10.3 ± 1.4 |

| Comparison (Z value UMWb [P value]) | |||

| Period 1 versus period 2 | −1.04 (0.29) | −1.28 (0.20) | −0.16 (0.87) |

| Period 1 versus period 3 | −0.16 (0.87) | −2.88 (0.003) | −2.88 (0.003) |

| Period 2 versus period 3 | −0.64 (0.52) | −1.92 (0.054) | −1.12 (0.26) |

| Global evolution (χ2KWc [P value]) | 1.02 (0.59) | 9.31 (0.009) | 5.71 (0.057) |

Patients were adjusted per every 100 ICU admissions.

Z value UMW, Z value of Mann-Whitney U test.

χ2KW, chi-square Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance.

Ab, A. baumannii.

The mean level of monthly carbapenem consumption was reduced 85% between the periods before (period 1) and early after implementation of restricted use of carbapenem (period 2), from 11.6 to 1.8 DDDs/100 ICU hospitalization days (Fig. 1). Afterward, low levels of monthly carbapenem consumption were maintained until the end of the study (period 3). Subsequently, the progressive dominance of CR A. baumannii in relation to CS A. baumannii was observed before the intervention was stopped (Fig. 5). Comparison of periods 1 and 2 and periods 1 and 3 showed differences that reached statistical significance. Of great concern was the fact that although the rates of CR and CS A. baumannii infection and colonization were similar for periods 2 and 3 (linear trend analysis between periods 2 and 3 showed nonsignificant differences), molecular typing of the CR A. baumannii isolates revealed an alarming dominance of clone E at the end of the study.

FIG. 5.

Temporal trends in clonal spread of carbapenem resistance among A. baumannii isolates by using molecular characterization of epidemic and endemic clones. Differences before and after the interventions were analyzed by comparing CR A. baumannii (clones D and E) and CS A. baumannii (clone A) groups for periods 1, 2, and 3 by using linear trend analysis with proportions. Six levels of exposition were selected per each period; these corresponded to months 1 to 6 for each period compared. Differences reached significant differences when periods 1 and 2 were compared (chi-square for linear trend, 6.14; P = 0.013) and periods 1 and 3 were compared (chi-square, 5.38; P = 0.02) but not when periods 2 and 3 were compared (chi-square, 1.13; P = 0.28).

DISCUSSION

Over the past two decades, the ability to control multiresistant A. baumannii epidemic infections has differed widely from one hospital to another, probably depending on several epidemiological factors (6, 11, 13, 17, 26, 30, 49, 57, 60, 63, 70, 76). In some institutions, in which epidemic infections were circumscribed to a sole ICU ward, a common contaminated object in the environment could usually be identified as the source of infection. In these cases, the implementation of isolation precautions and modification of cleaning procedures resulted in the prompt eradication of the outbreak. In contrast, in other hospitals, epidemic infections have become endemic, and the clinical and microbiological epidemiologies of these infections remain obscure.

It is of great concern that when directives regarding effective infection control measures for large and sustained outbreaks due to multiresistant A. baumannii were still not well defined, resistance involved carbapenems in our outbreak setting. Although resistance emerged after considerable pressure from imipenem use, a molecular typing approach showed that this was not due to the acquisition of resistance mechanisms by the clones responsible for the outbreak but, rather, was due to the sequential introduction of two new clones. After detection of the first CR A. baumannii infection, a dramatic increase in the incidence rate of new ICU patients infected or colonized with carbapenem-resistant isolates was observed. CR A. baumannii strains initially showed intermediate resistance to imipenem (clone D), but afterward a new, different clone (clone E) highly resistant to all commercially available antibiotics except polymyxins appeared and became dominant.

The risk factors associated with the development of A. baumannii infections have raised controversy. In most studies, the risk factors identified were in accordance with those associated with other nosocomial infections, such as the severity of illness, the prior use of antibiotics, or the previous number of days with invasive devices in place (41, 47, 75). However, when prospective screening for colonized patients was done by body site, we previously observed that a large proportion of ICU patients became secondarily colonized with A. baumannii at different body sites, similar to that which occurs in patients infected or colonized with other nosocomial pathogens (64). This previous state of A. baumannii carriage was a major attribute for the subsequent development of A. baumannii infections (18, 20). Under special epidemiological circumstances such as those noted in our ICUs, the inadequate prevention of cross-transmission determined that A. baumannii carriage occurred very early during ICU admission. In the present study our aim was not to again identify potential attributes for A. baumannii colonization of body sites for our ICU population but, rather, those risk factors particularly associated with the development of clinical episodes of CR A. baumannii colonization or infection among those patients harboring clinical A. baumannii isolates. The logistic regression analysis selected the previous state of CR A. baumannii carriage and the presence of a larger proportion of CR A. baumannii-infected or -colonized patients in the same ICU ward as statistically significant risk factors with regard to other classical risk factors for nosocomial infections, such as the severity of illness or the previous number of days an invasive device was in place. These results reaffirmed some of our previous observations regarding the epidemiology of A. baumannii and demonstrate the important role of horizontal transmission in the acquisition of A. baumannii organisms (either CR or CS strains). In such circumstances, exposure to carbapenems may provide a selective advantage for CR A. baumannii colonizing clones competing with CS A. baumannii clones.

Before the emergence of CR A. baumannii, the outbreak was never under control, although measures including strict attention to cleaning procedures and barrier precautions were repeatedly implemented. The urgent need for control of the outbreak increased definitively when our ability to treat A. baumannii infections became severely threatened by the spread of carbapenem resistance. With the risk factors mentioned above kept in mind, this spread was attacked by a complex combination of procedures that did not include the topical administration of antibiotics for decontamination of patients. Although selective intestinal decontamination might be considered a reasonable additional measure for control (58), in view of the high rates of fecal carriage observed in A. baumannii outbreaks (18, 67), in our ICU setting, several arguments discouraged us from using it during the study. These reasons were the possible exogenous route of the origin of such infections, either from the inanimate environment or from other concomitantly colonized body sites such as the skin, and the extremely narrow range of therapeutic options for our A. baumannii-infected patient population. Multiple-antibiotic resistance casts doubt on the real efficacy of digestive decontamination, since many strains were highly resistant to aminoglycosides (a family of antibiotics usually included in decontamination schedules, along with polymyxins). Taking all these factors into account, we believed that there was a true risk not only of failure from the use of monotherapy but also of the emergence of more resistant A. baumannii strains.

It is difficult to state whether the subsequent decrease in incidence rates was the consequence of interventions in Acinetobacter epidemics, since several confounding factors such as seasonality are known to influence incidence rates (56). In our case, the trend was slowed down and, thereafter, was dramatically reversed during the late summer months, the season in which Acinetobacter epidemics tend to rise worldwide. Determination of the relative role of the different interventions applied is problematic, because they concurred in time and probably interacted with one another. However, we believe that the fact that the proportions of A. baumannii isolates were reduced similarly among the CR and CS A. baumannii groups (both clinical and environmental) strongly reinforces the roles of adequate compliance with hand-washing procedures, the use of barrier precautions, and cleaning procedures in controlling A. baumannii outbreaks. On the other hand, restriction of carbapenem use appeared to be useful in delaying the progressive increase in the incidence of CR A. baumannii infections or colonizations in relation to the incidence of CS A. baumannii infections or colonizations, although carbapenem resistance did not revert to susceptibility after 1 year of restricted use.

Multiresistant, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii outbreaks are now gradually posing a threat to the hospitalized populations in some public tertiary-care hospitals (14, 15, 31, 42, 59, 66). However, only very few of these outbreaks, such as that described by Go et al. (31), were managed from a combined clinical-microbiological point of view (23, 45). In contrast to our results, those investigators achieved not only a progressive decrease in the A. baumannii incidence rates but also a complete reversion of carbapenem resistance. It is difficult to assess the extent to which this different response may be due in part to the fact that in the outbreak reported by Go et al. (31) imipenem resistance developed from A. baumannii strains belonging to the previous clones responsible for the endemic, while in our case, the carbapenem resistance was due to the acquisition of two new epidemic clones (clones D and E).

Similar to other multiresistant populations, for A. baumannii organisms it is difficult to separate resistance from their clinical behavior (29). Prior to the spread of CR A. baumannii, the clinical virulence of CS A. baumannii had not been well defined, although it was noted to be almost uniformly associated with high crude mortality rates (about 40 to 50%) (6, 14, 25, 62). However, the facts that the isolation of A. baumannii from clinical specimens may often reflect colonization rather than significant infection, that most isolates occur in severely ill ICU patients with several underlying diseases, that a large proportion of infections are polymicrobial, and that most infections are usually associated with multiple invasive procedures make controlled investigations extremely difficult. Therefore, in the immediate future, only clinical judgment in the selection of the sort of patients who really need antibiotics and animal models may provide an appropriate basis to assess the role of CR A. baumannii in such infections and of antibiotic alternatives in modifying the final outcomes for patients (79).

This study has provided evidence that the fateful trend toward antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii may finally include carbapenems, the last recognized antibiotic alternative for most strains isolated worldwide, during large and sustained hospital outbreaks. Management of these emerging organisms is complex and requires a combination of molecular typing techniques and epidemiological studies. High-level and extended environmental contamination, close contact between colonized patients and health care workers, and widespread imipenem use were the main determinant factors that promoted rapid clonal dissemination of CR A. baumannii throughout the hospital. Restriction of carbapenem use and, probably more importantly, strict compliance with basic infection control measures may have a strong impact on controlling A. baumannii outbreaks, although carbapenem resistance may not be eliminated. In summary, to confront the imminent threat of untreatable A. baumannii infections, physicians should sharpen their good clinical judgment when making antibiotic treatment decisions and should strongly ensure strict compliance with basic control measures for the containment of infection. Although controversial, other potential measures, such as the use of selective decontamination programs that prevent patient carriage, may be considered in addition to basic infection control strategies when the “traditional” approach fails to control an outbreak.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the doctors and nurses from the Intensive Care Medicine Service (Hospital de Bellvitge) who provided care for the patients included in the study, Rafael Abós from the Unitat Clínico-Epidemiològica (Hospital de Bellvitge) for assistance with statistical analysis, Mercedes Sora from the Pharmacy Department (Hospital de Bellvitge) for providing antibiotic consumption data, Isabel García-Arata from the Microbiology Laboratory (Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, Spain) for ribotype analysis, and Amaya Virós for helpful advice in manuscript preparation.

The study was supported by the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias de la Seguridad Social (grants 96-0674 and 98-0525) from the National Health Service of Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acar J F, Bergogne-Bérézin E, Chabbert Y, Cluzel R, Courvalin P, Dabernat H, Drugeon H, Duval J, Flandrois J P, Fleurette J, Goldstein F, Meyran M, Morel C L, Philippon A, Sirot J, Soussy C J, Thabaut A, Veron M. Statement of the Antibiogram Committee of the French Society for Microbiology. Pathol Biol. 1992;40:741–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acar J F, Goldstein F W. Consequences of increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S125–S130. doi: 10.1086/514913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afzal-Shah M, Livermore D M. Worldwide emergence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:576–577. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.5.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archibald L, Phillips L, Monnet D, McGowan J E, Jr, Tenover F, Gaynes R. Antimicrobial resistance in isolates from inpatients and outpatients in the United States: increasing importance of the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:211–215. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayats J, Corbella X, Ardanuy C, Dominguez M A, Ricart A, Liñares J, Ariza J, Martin R. Epidemiological significance of cutaneous, pharyngeal, and digestive tract colonization by multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii in ICU patients. J Hosp Infect. 1997;37:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(97)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck-Sague C M, Jarvis W R, Brook J H, Culver D H, Potts A, Gay E, Shotts B W, Hill B, Anderson R L, Weinstein M P. Epidemic bacteremia due to Acinetobacter baumannii in five intensive care units. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:723–733. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergogne-Berezin E, Towner K J. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:148–165. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergogne-Berezin E, Joly-Guillou M L. Hospital infection with Acinetobacter spp.: an increasing problem. J Hosp Infect. 1991;18(Suppl. A):250–255. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(91)90030-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bou G, Cervero G, Dominguez M A, Quereda C, Martínez-Beltrán J. Characterization of a nosocomial outbreak caused by a multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain with a carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme: high-level carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii is not due solely to the presence of β-lactamases. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3299–3305. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3299-3305.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown S, Bantar C, Young H K, Amyes S G B. Limitation of Acinetobacter baumannii treatment by plasmid-mediated carbapenemase ARI 2. Lancet. 1997;351:186–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buisson Y, Tran van Nhieu G, Ginot L, Bouvet P, Schill H, Driot L, Meyran M. Nosocomial outbreaks due to amikacin-resistant tobramycin-sensitive Acinetobacter species: correlation with amikacin usage. J Hosp Infect. 1990;15:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90024-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catchpole C R, Andrews J M, Brenwald N, Wise R. A reassessment of the in-vitro activity of colistin sulphomethate sodium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:255–260. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cefai C, Richards J, Gould F K, McPeake P. An outbreak of Acinetobacter respiratory tract infection resulting from incomplete disinfection ventilatory equipment. J Hosp Infect. 1990;15:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90128-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cisneros J M, Reyes M J, Pachón J, Becerril B, Caballero F J, García-Garmendia J L, Ortiz C, Cobacho A R. Bacteremia due to Acinetobacter baumannii: epidemiology, clinical findings, and pronostic features. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:1026–1032. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark R B. Imipenem resistance among Acinetobacter baumannii: association with reduced expression of a 33-36 kDa outer membrane protein. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:245–251. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen M L. Epidemiology of drug resistance: implications for a post-antimicrobial era. Science. 1992;257:1050–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contant J, Kemeny E, Oxley C, Perry E, Garber G. Investigation of an outbreak of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus var. anitratus infections in an adult intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 1990;18:288–291. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(90)90171-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbella X, Pujol M, Ayats J, Sendra M, Ardanuy C, Domínguez M A, Liñares J, Ariza J, Gudiol F. Relevance of digestive tract colonization in the epidemiology of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:329–334. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbella X, Ariza J, Ardanuy C, Vuelta M, Tubau F, Sora M, Pujol M, Gudiol F. Efficacy of sulbactam alone and in association with ampicillin in nosocomial infections due to Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:793–802. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbella X, Pujol M, Argerich M J, Ayats J, Sendra M, Peña C, Ariza J. Environmental sampling of Acinetobacter baumannii: moistened swabs versus moistened sterile gauze pads. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:458–460. doi: 10.1086/503137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crombach W H J, Dijkshoorn L, van Noort-Klaassen M, Niessen J, van Knippenberg-Gordebeke G. Control of an epidemic spread of a multi-resistant strain of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus in a hospital. Intensive Care Med. 1989;15:166–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01058568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Da Silva G J, Leitao G J, Peixe L. Emergence of carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2109–2010. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2109-2110.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dijkshoorn L, Aucken H M, Gerner-Smidt P, Kaufmann M E, Ursing J, Pitt T L. Correlation of typing methods for Acinetobacter isolates from hospital outbreaks. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:702–705. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.702-705.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dijkshoorn L. Acinetobacter—microbiology. In: Bergogne-Bérézin E, Joly-Guillou M L, Towner K J, editors. Acinetobacter: microbiology, epidemiology, infections, management. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1996. pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fagon J Y, Chastre J, Domart Y, Trouillet J L, Gibert C. Mortality due to ventilator-associated pneumonia or colonization with Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter species; assessment by quantitative culture of samples obtained by a protected specimen brush. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:538–542. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.French G L, Casewell M W, Roncoroni A J, Knight S, Phillips I. A hospital outbreak of antibiotic resistant Acinetobacter anitratus: epidemiology and control. J Hosp Infect. 1980;1:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(80)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Arata M I, Gerner-Smidt P, Baquero F, Ibrahim A. PCR-amplified 16S and 23S rDNA restriction analysis for the identification of Acinetobacter strains at the DNA group level. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:777–784. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(97)82453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garner J S, Jarvis W R, Emori T C, Horan T C, Hughes J M. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:128–140. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerner-Smidt P. Endemic occurrence of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus biovar anitratus in an intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 1987;10:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(87)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Getchell-White S I, Donowitz L G, Groschel D H. The inanimate environment of an intensive care unit as a potential source of nosocomial bacteria: evidence for long survival of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1989;10:402–406. doi: 10.1086/646061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Go E S, Urban C, Burns J, Kreiswirth B, Eisner W, Mariano N, Mosinka-Snipas K, Rahal J J. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of Acinetobacter infections sensitive only to polymyxin B and sulbactam. Lancet. 1994;344:1329–1332. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiramatsu K, Aritaka N, Hanaki H, Kawasaki S, Hosoda Y, Hori S, Fukuchi Y, Kobayashi I. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet. 1997;350:1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacoby G A, Archer G L. New mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:601–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102283240906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiménez-Mejías M E, Pachón J, Becerril B, Palomino-Nicás J, Rodríguez-Cobacho A, Revuelta M. Treatment of multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis with ampicillin/sulbactam. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:932–935. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joly-Guillou M L, Decre D, Herrman J L, Bourdelier E, Bergogne-Berezin E. Bactericidal in-vitro activity of β-lactams and β-lactamase inhibitors, alone or associated, against clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii: effect of combination with aminoglycosides. J Antimicrob Chemoter. 1995;36:619–629. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones R N, Dudley M N. Microbiologic and pharmacodynamic principals applied to the antimicrobial susceptibilty testing of ampicillin/sulbactam: analysis of the correlations between in vitro test results and clinical response. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;28:5–18. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kucers A, Crowe S, Graysson M L, Hoy J. Polymyxins. In: Kucers A, Crowe S, Graysson M L, Hoy J, editors. The use of antibiotics. A comprehensive review with clinical emphasis. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1997. pp. 667–675. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert T G, Gerbaud G, Bouvet P, Vieu J F, Courvalin P. Dissemination of amikacin resistance gene aphA6 in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1244–1248. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Gall J R, Loirat P, Alperovich A, Glaser P, Granthil C, Mathieu D, Mercier P, Thomas R, Villers D. A simplified acute physiology score for ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 1984;12:975–977. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198411000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lortholary O, Fagon J Y, Buu-Hoi A, Slama M A, Pierre J, Giralt P, Rosenzweig R, Gutmann L, Safar M, Acar J. Nosocomial acquisition of multiresistant A. baumannii: risk factors and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:790–796. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyytikainen O, Koljaig S, Harma M, Vuopio-Varkila J. Outbreak caused by two multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clones in a burns unit: emergence of resistance to imipenem. J Hosp Infect. 1995;31:41–54. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maslow J N, Slutsky A M, Arbeit R D. Application of pulsed-field electrophoresis to molecular epidemiology. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 563–571. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCabe W R, Jackson G G. Gram negative bacteremia. Am J Med. 1962;110:847–855. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald L C, Jarvis W R. Linking antimicrobial use to nosocomial infections: the role of a combined laboratory-epidemiology approach. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:245–247. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moellering R C., Jr Emergence of enterococcus as a significant pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:1173–1178. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mulin B, Talon D, Viel J F, Vicent C, Leprat R, Thouverez M, Michel-Briand Y. Risk factors for nosocomial colonization with multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:569–576. doi: 10.1007/BF01690727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray B E. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Musa E K, Desai N, Casewell M W. The survival of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus inoculated on fingertips and on formica. J Hosp Infect. 1990;15:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90029-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. NCCLS document M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 9th informational supplement. NCCLS document M100–S9. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neu H C. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science. 1992;257:1064–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paton R H, Miles S, Hood J, Amyes S G B. ARI 1: β-lactamase-mediated imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1993;2:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(93)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peackock J E, Jr, Marsik F J, Wenzel R P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: introduction and spread within a hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:526–532. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-4-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quinn J P. Clinical problems posed by multiresistant nonfermenting Gram-negative pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl.1):S117–S124. doi: 10.1086/514912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Retailliau H F, Hightower A W, Dixon R E, Allen J R. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus: a nosocomial pathogen with an unusual seasonal pattern. J Infect Dis. 1979;139:371–375. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakata H, Fujita K, Maruyama S, Kakehashi H, Mori Y, Yoshioka H. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus biovar. anitratus septicaemia in a neonatal intensive care unit: epidemiology and control. J Hosp Infect. 1989;14:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(89)90129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanchez M, Cambronero J A, Lopez J, Cerda E, Rubio J, Gomez M A, Nuñez A, Rogero S, Oñoro J J, Sacristan J A. Effectiveness and cost of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in critically ill intubated patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:908–916. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9712079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scaife W, Young H K, Paton R, Amyes S G B. Transferable imipenem-resistance in Acinetobacter species from a clinical source. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:585–587. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seifert H, Boullion B, Schulze A, Pulverer G. Plasmid DNA profiles of Acinetobacter baumannii: clinical application in a complex endemic setting. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15:520–528. doi: 10.1086/646970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seifert H, Gerner-Smidt P. Comparison of ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for molecular typing of Acinetobacter isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1402–1407. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1402-1407.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seifert H, Strate A, Pulverer G. Nosocomial bacteremia due to Acinetobacter baumannii: clinical features, epidemiology, and predictors of mortality. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74:340–349. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199511000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherertz R J, Sullivan M L. An outbreak of infection in burn patients: contamination of patients' mattresses. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:252–258. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silvestri L, Monti Bragadin C, Milanese M, Gregori D, Consales C, Gullo A, Van Saene H K F. Are most ICU infections really nosocomial? A prospective observational cohort study in mechanically ventilated patients. J Hosp Infect. 1999;42:125–133. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1998.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soussy C J, Cluzel R, Courvalin P the Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. Definition and determination of in vitro antibiotic susceptibility breakpoints for bacteria in France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:238–246. doi: 10.1007/BF01974543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tankovic J, Legrand P, de Gatines G, Chemineau V, Brun-Buisson C, Duval J. Characterization of a hospital outbreak of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by phenotypic and genotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2677–2681. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2677-2681.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Timsit J F, Garrait V, Misset B, Goldstein F W, Renaud B, Carlet J. The digestive tract is a major site for Acinetobacter baumannii colonization in intensive care unit patients. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1336–1337. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomasz A. Multiple-antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1247–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urban C, Go E, Mariano N, Berger B J, Avraham I, Rubin D, Rahal J J. Effect of sulbactam on infections caused by imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter calcoaceticus biotype anitratus. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:448–451. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vila J, Amela M, Jimenez de Anta M T. Laboratory investigation of hospital outbreak caused by two different multiresistant Acinetobacter calcoaceticus subsp. anitratus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1086–1089. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.1086-1089.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vila J, Marcos M A, Jimenez de Anta M T. A comparative study of different PCR-based DNA fingerprinting techniques for typing of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:482–489. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vila J, Navia M, Ruiz J, Casal C. Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of a gene enconding a OXA-derived β-lactamase in A. baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2757–2759. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vila J, Ruiz J, Navia M, Becerril B, Garcia I, Perea S, Lopez-Hernandez I, Alamo I, Ballester F, Planes A M, Martinez-Beltran J, Jimenez de Anta M T. Spread of amikacin resistance in A. baumannii strains isolated in Spain due to an epidemic strain. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:758–761. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.758-761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Viladrich P F, Corbella X, Corral L, Tubau F, Mateu A. Successful treatment of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventriculitis with intraventricular colistin sulphomethate sodium. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:916–917. doi: 10.1086/517243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Villers D, Espaze E, Coste-Burel M, Giauffret F, Ninin E, Nicolas F, Richet H. Nosocomial Acinetobacter baumannii infections: microbiological and clinical epidemiology. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:182–189. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weernink A, Severin W P J, Tjernberg I, Dijkshoorn L. Pillows, an unexpected source of Acinetobacter. J Hosp Infect. 1995;29:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wendt C, Dietze B, Dietz E, Ruden H. Survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1394–1397. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1394-1397.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wenzel R P, Edmon M B. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus:infection control considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:245–251. doi: 10.1086/514646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wolff M, Joly-Guillou M L, Farinotti R, Carbon C. In vivo efficacies of combinations of β-lactams, β-lactamase inhibitors, and rifampin against Acinetobacter baumannii in a mouse pneumonia model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1406–1411. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wood C A, Reboli A C. Infections caused by imipenem-resistant A. calcoaceticus biotype anitratus. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1602–1603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]