Abstract

Background

Indoor residual spraying (IRS) and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) are malaria vector control measures used in India, but the development of insecticide resistance poses major impediments for effective vector control strategies. As per the guidelines of the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP), the study was conducted in 12 districts of Madhya Pradesh to generate data on insecticide resistance in malaria vectors.

Methods

The susceptibility tests were conducted on adult An. culicifacies as per the WHO standard technique with wild-caught mosquitoes. The blood-fed female mosquitoes were exposed in 3 to 4 replicates on each occasion to the impregnated papers with specified discriminating dosages of the insecticides (DDT: 4%, malathion: 5%, deltamethrin: 0.05%, and alphacypermethrin: 0.05%), for one hour, and mortality was recorded after 24-hour holding.

Results

An. culicifacies was found resistant to DDT 4% in all the 12 districts and malathion in 11 districts. The resistance to alphacypermethrin was also observed in two districts, and possible resistance was found to alphacypermethrin in seven districts and to deltamethrin in eight districts, while the vector was found susceptible to both deltamethrin and alphacypermethrin in only 3 districts.

Conclusion

An. culicifacies is resistant to DDT and malathion and has emerging resistance to pyrethroids, alphacypermethrin, and deltamethrin. Therefore, regular monitoring of insecticide susceptibility in malaria vectors is needed for implementing effective vector management strategies. However, studies to verify the impact of IRS with good coverage on the transmission of disease are required before deciding on the change of insecticide in conjunction with epidemiological data.

1. Introduction

Malaria is a major public health problem in India, contributing to about 89% of incidence from South East Asia [1]. Five Indian states are responsible for transmission of more than 70% of malaria in the country of which Madhya Pradesh is the fifth highly malarious state which contributes about 5% of total malaria cases [2]. Anopheles culicifacies is the main malaria vector in rural and periurban areas in India contributing to about 65% of annual malaria transmission [3]. Insecticide-based vector control interventions currently in use in India include indoor residual spraying (IRS) and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) [4]. One of the major impediments for effective vector control is the development of resistance in vectors to the insecticides which are used in public health sprays. Presently, three insecticides, DDT (organochlorine), malathion (organophosphate), and mostly synthetic pyrethroids, are used in IRS and LLINs. An. culicifacies has shown resistance to DDT [5–7] and malathion [8, 9] and also reduced susceptibility to synthetic pyrethroids in a few areas including in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh [10–14]. This study was undertaken as a task force project under the aegis of the Indian Council of Medical Research. Based on epidemiological data and geographic ecosystems, the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) selected 12 districts of Madhya Pradesh to generate data on insecticide resistance in malaria vectors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epidemiological situation in the districts selected for the insecticide monitoring study.

| Districts | Year | Population | BSE | +VE | PF | ABER | API | SPR | PF% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhar | 2015 | 2364759 | 348960 | 4328 | 1949 | 15.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 45.00 |

| 2016 | 2412054 | 320115 | 2100 | 765 | 13.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 36.00 | |

| Hoshangabad | 2015 | 1343272 | 197175 | 1672 | 665 | 14.68 | 1.24 | 0.85 | 39.0 |

| 2016 | 1372137 | 197608 | 1139 | 445 | 14.42 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 39.0 | |

| Anuppur | 2015 | 811306 | 79769 | 2007 | 1280 | 10.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 64.00 |

| 2016 | 776248 | 79504 | 1226 | 764 | 10.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 62.00 | |

| Panna | 2015 | 1078217 | 167850 | 1332 | 242 | 16.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 18.00 |

| 2016 | 1099781 | 13969 | 1582 | 479 | 13.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 30.00 | |

| Tikamgarh | 2015 | 1534632 | 152233 | 1336 | 18 | 9 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 1.35 |

| 2016 | 1564028 | 185300 | 1327 | 38 | 11.8 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 2.86 | |

| Shivpuri | 2016 | 1884582 | 220925 | 3885 | 576 | 12.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 15.00 |

| 2017 | 1922690 | 201781 | 1648 | 93 | 11.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6.00 | |

| Datia | 2016 | 868232 | 90424 | 456 | 8 | 44.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 7.00 |

| 2017 | 885586 | 113899 | 506 | 3 | 10.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 2.00 | |

| Alirajpur | 2016 | 800942 | 122482 | 1602 | 713 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 44 |

| 2017 | 810614 | 84331 | 704 | 302 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 43 | |

| Bhind | 2016 | 1880870 | 218174 | 3424 | 51 | 11.60 | 1.82 | 1.57 | 1.49 |

| 2017 | 1918488 | 191213 | 1925 | 11 | 9.97 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.57 |

Note. The epidemiological data of three districts (Singrauli, Khargone, and Umaria) were not available at the time of study. BSE: blood smear examination, +VE: number of malaria positive cases, PF: Plasmodium falciparum, ABER: annual blood examination rate, API: annual parasite incidence, SPR: slide positivity rate, and PF%: Plasmodium falciparum percentage.

There are 50 districts in Madhya Pradesh with a population of about 60 million, including 12 million tribal populations. The state consists of sparsely settled forested hills with a 31% forested area and serves as a reservoir for intense perennial malaria transmission [15]. In the present investigation, we monitored the insecticide susceptibility status of An. culicifacies in 12 districts of Madhya Pradesh against commonly used insecticides in the public health system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The susceptibility tests against An. culicifacies were carried out in 12 districts of Madhya Pradesh located in the northern, eastern, western and southern parts of the state, namely, districts Umaria, Singrauli, Anuppur, Panna, Tikamgarh, Hoshangabad, Khargone, Dhar, Alirajpur, Bhind, Datia, and Shivpuri, from July 2017 to July 2019. In the districts, three to seven villages in two to three CHCs (about 1% of total villages in the district) in different terrains, i.e., hilltop, plain, foothill, and forest terrains were selected for the studies (Table 2). Anuppur, Umaria, and Bhind were under DDT indoor spray and Singrauli, Panna, Hoshangabad, Khargone, Dhar, Alirajpur, and Shivpuri were under alphacypermethrin (synthetic pyrethroid) indoor spray. In districts Tikamgarh and Datia, there was no routine indoor spray for the last >20 years due to low malaria prevalence (<2 API). However, in the year 2016, 26 villages in the district of Tikamgarh received focal sprays of DDT. In five districts, viz., Panna, Anuppur, Singrauli, Alirajpur, and Dhar, long-lasting insecticide-treated nets were distributed (Table 2). However, all the districts were proposed for LLIN distribution by the year 2019.

Table 2.

Profile of study areas including the vector control measures and the period of study.

| S No. | Districts | Location | Insecticide used for IRS | LLIN distributed (yes or no) | No. of study villages | Ecotype of villages | Period of surveys |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anuppur | East | DDT | Yes | 6 | Plain, foothill, hilltop | Sept 2017 |

| 2 | Panna | North east | SP | Yes | 6 | Plain, foothill, hilltop | Oct 2017 |

| 3 | Tikamgarh | North | No spray | No | 3 | Plain, forest | Oct 2017 |

| 4 | Singrauli | East | SP | Yes | 6 | Plain, foothill, hilltop | Oct 2017 |

| 5 | Umaria | East | DDT | No | 6 | Plain, foothill, hilltop | July 2017 |

| 6 | Hoshangabad | South | SP | Yes | 6 | Plain, foothill, hilltop | Apr 2018 |

| 7 | Khargone | South | SP | No | 6 | Plain, foothill, forest | Sept 2018 |

| 8 | Alirajpur | West | SP | Yes | 6 | Plain, foothill, forest | Dec 2018 and Jul 2019 |

| 9 | Dhar | West | SP | Yes | 6 | Plain, foothill, forest | Dec 2018 and Jul 2019 |

| 10 | Shivpuri | North | SP | No | 7 | Plain, foothill, hilltop | Feb 2019 |

| 11 | Datia | North | No spray | No | 6 | Plain, forest | Feb 2019 |

| 12 | Bhind | North | DDT | No | 7 | Plain, foothill | Jul 2019 |

SP = synthetic pyrethroids: alphacypermethrin

2.2. Insecticide Susceptibility Tests

Susceptibility tests were conducted on adult An. culicifacies following essentially the WHO standard procedures using the kit and method [16]. Wild-caught mosquitoes were collected from different resting sites (indoors-human dwellings/cattle sheds and outdoors) and preferably blood-fed female mosquitoes [17] and identified based on morphological characters [18] in the selected villages of the districts in the different months from 2017 to 2019 (Table 2). The collected mosquitoes were brought to the laboratory for testing in cloth cages wrapped with wet towels. Female mosquitoes were exposed in 3 to 4 replicates on each occasion to the WHO impregnated papers with specified discriminating dosages of the insecticides (DDT: 4%, malathion: 5%, deltamethrin: 0.05%, and alphacypermethrin: 0.05%), with respective insecticide controls for comparison (two replicates) for one hour, and mortality was recorded after 24-hour holding. The tests were repeated within 2 or 3 days in different villages of different terrains in each district. Cartons with wet towels at the bottom were used to conduct the tests to maintain the ambient temperature of 26 ± 2°C and the RH of 70–80% [19]. Mortality after 24 hrs of holding period was recorded [20]. Percent mortality was calculated separately for the test and control replicates using the following formula: % observed mortality = number of dead mosquitoes × 100/number of mosquitoes tested.

If the mortality in control replicates is between 5% and 20%, the test mortality was corrected with the control mortality using Abbott's formula [21]. In cases where the mortality in the controls exceeded 20%, the test was discarded: % corrected mortality = (% test mortality – % control mortality) × 100/(100 – % control mortality).

According to the WHO criteria [20], mosquito species that show on exposure to the diagnostic dosage of a given insecticide a mortality rate of 98 to 100% are designated as “susceptible,” <90% as “confirmed resistance,” and between 90% and 98% as “possible resistance.”

3. Results

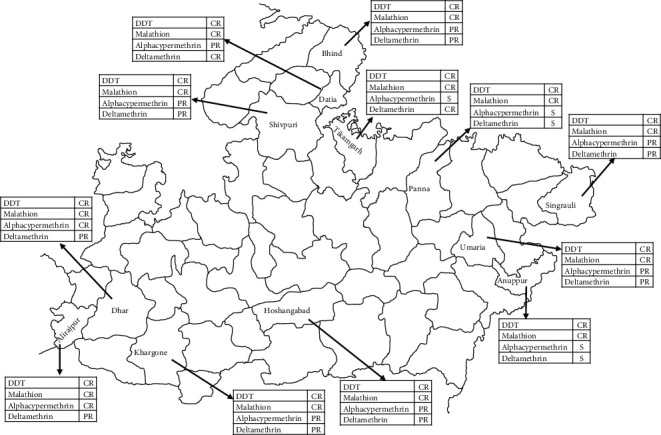

Results of the susceptibility tests carried out in 12 districts are given in Table 3. An. culicifacies was found resistant to DDT in all the districts with a % mortality rate ranging from 7.6 to 60% and resistant to malathion in 11 districts (62 to 87%) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Susceptibility status of An. culicifacies to discriminatory dosages of DDT, malathion, alphacypermethrin, and deltamethrin in 12 districts of Madhya Pradesh.

| Insecticide-% | Districts | No. of mosquitoes exposed | Dead 24 hr | Mortality (%)∗ | Susceptibility status∗∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp | Control | Exp | Control | ||||

| DDT-4% | Anuppur | 105 | 60 | 17 | 1 | 16.2 | CR |

| Panna | 105 | 45 | 13 | 1 | 12.4 | CR | |

| Singrauli | 105 | 45 | 19 | 0 | 18.1 | CR | |

| Tikamgarh | 105 | 30 | 17 | 0 | 16.2 | CR | |

| Umaria | 105 | 45 | 15 | 0 | 14.3 | CR | |

| Hoshangabad | 105 | 60 | 8 | 2 | 7.6 | CR | |

| Khargone | 120 | 60 | 15 | 1 | 12.5 | CR | |

| Alirajpur | 105 | 45 | 8 | 1 | 7.6 | CR | |

| Dhar | 120 | 45 | 21 | 0 | 17.5 | CR | |

| Datia | 100 | 45 | 60 | 1 | 60 | CR | |

| Shivpuri | 100 | 55 | 41 | 0 | 41 | CR | |

| Bhind | 105 | 45 | 17 | 0 | 16.2 | CR | |

|

| |||||||

| Malathion-5% | Anuppur | 105 | 60 | 68 | 1 | 64.8 | CR |

| Panna | 105 | 45 | 77 | 0 | 73.3 | CR | |

| Singrauli | 105 | 45 | 74 | 2 | 70.5 | CR | |

| Tikamgarh | 105 | 30 | 89 | 0 | 84.8 | CR | |

| Umaria | 105 | 45 | 80 | 0 | 76.2 | CR | |

| Hoshangabad | 105 | 60 | 76 | 2 | 72.4 | CR | |

| Khargone | 120 | 60 | 78 | 0 | 65 | CR | |

| Alirajpur | 105 | 45 | 61 | 0 | 58.1 | CR | |

| Dhar | 120 | 45 | 78 | 0 | 65 | CR | |

| Datia | 100 | 45 | 93 | 2 | 93 | PR | |

| Shivpuri | 100 | 55 | 87 | 2 | 87 | CR | |

| Bhind | 105 | 45 | 67 | 0 | 63.8 | CR | |

|

| |||||||

| Alphacypermethrin-0.05% | Anuppur | 105 | 60 | 103 | 2 | 98.1 | S |

| Panna | 105 | 45 | 104 | 0 | 99 | S | |

| Singrauli | 105 | 45 | 95 | 1 | 90.5 | PR | |

| Tikamgarh | 105 | 30 | 105 | 0 | 100 | S | |

| Umaria | 105 | 45 | 100 | 1 | 95.2 | PR | |

| Hoshangabad | 105 | 60 | 101 | 0 | 96.2 | PR | |

| Khargone | 120 | 60 | 112 | 1 | 93.3 | PR | |

| Alirajpur | 105 | 45 | 92 | 2 | 87.6 | CR | |

| Dhar | 120 | 45 | 101 | 1 | 84.2 | CR | |

| Datia | 100 | 45 | 97 | 2 | 97 | PR | |

| Shivpuri | 100 | 55 | 93 | 2 | 93 | PR | |

| Bhind | 105 | 45 | 100 | 0 | 95.2 | PR | |

|

| |||||||

| Deltamethrin-0.05% | Anuppur | 105 | 60 | 103 | 2 | 98.1 | S |

| Panna | 105 | 45 | 104 | 0 | 99 | S | |

| Singrauli | 105 | 45 | 98 | 1 | 93.3 | PR | |

| Tikamgarh | 105 | 30 | 105 | 0 | 100 | S | |

| Umaria | 105 | 45 | 101 | 1 | 96.2 | PR | |

| Hoshangabad | 105 | 60 | 100 | 0 | 95.2 | PR | |

| Khargone | 120 | 60 | 116 | 1 | 96.7 | PR | |

| Alirajpur | 105 | 45 | 101 | 2 | 96.2 | PR | |

| Dhar | 120 | 45 | 112 | 1 | 93.3 | PR | |

| Datiya | 100 | 45 | 100 | 2 | 100 | S | |

| Shivpuri | 100 | 55 | 97 | 2 | 97 | PR | |

| Bhind | 105 | 45 | 102 | 0 | 97.1 | PR | |

∗ The control mortality in all districts in all insecticides was either <5.0. ∗∗ CR = confirmed resistant, PR = possible resistant, and S = susceptible.

Figure 1.

Map of Madhya Pradesh showing study districts and insecticide susceptibility status of An. culicifacies.

In district Datia, species showed possible resistance to malathion, registering 93% mortality. Resistance to alphacypermethrin was observed in Dhar and Alirajpur districts where % mortality was 84.2 and 87.6, respectively, and tests were repeated after 6 months, and the mortality was 82.9 and 85.7% indicating no variation in mortality (Table 3).

An. culicifacies was reported susceptible to pyrethroids, viz., alphacypermethrin and deltamethrin in 3 districts, i.e., Anuppur, Panna, and Tikamgarh (98.1 to 100.0% mortality), while in Datia it was susceptible to deltamethrin (100% mortality).

An. culicifacies was possibly resistant to alphacypermethrin in 7 districts, viz., Singrauli, Umaria, Hoshangabad, Khargone, Datia, Shivpuri, and Bhind, with mortality ranging from 90.5 to 97.0%. However, to deltamethrin, possible resistance in An. culicifacies was observed in 8 districts, viz., Singrauli, Umaria, Hoshangabad, Khargone, Alirajpur, Dhar, Shivpuri, and Bhind where mortality registered was between 93.3 and 97% (Table 3).

The terrain-wise pooled data of 12 districts (Table 4) showed similar susceptibility status in all 4 terrains, i.e., plain, foothill, hilltop, and forest areas except for deltamethrin. The species was possibly resistant with registered mortality of 96.7%, 94.3%, and 96.4%, respectively, in plain, foothill, and hilltop terrains, whereas in forest terrain the species was susceptible to deltamethrin with 98% mortality. However, the difference in observed mortalities was within a range of 2–4% indicating the population to be near susceptible or possibly resistant.

Table 4.

Terrain-wise grouped insecticide susceptibility data in An. culicifacies.

| Type of terrain | Insecticide | No. of mosquitoes exposed | Mortality in 24 hr | Mortality (%) | Susceptibility status∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp | Control | Exp | Control | ||||

| Plain | DDT | 600 | 285 | 116 | 3 | 19.3 | CR |

| Malathion | 600 | 285 | 442 | 4 | 73.7 | CR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 600 | 285 | 548 | 10 | 91.3 | PR | |

| Deltamethrin | 600 | 285 | 580 | 10 | 96.7 | PR | |

| Forest | DDT | 295 | 120 | 69 | 0 | 23.4 | CR |

| Malathion | 295 | 120 | 213 | 1 | 72.2 | CR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 295 | 120 | 274 | 0 | 92.9 | PR | |

| Deltamethrin | 295 | 120 | 289 | 0 | 98.0 | S | |

| Foothill | DDT | 400 | 190 | 58 | 2 | 14.5 | CR |

| Malathion | 400 | 190 | 268 | 1 | 67.0 | PR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 400 | 190 | 366 | 4 | 91.5 | PR | |

| Deltamethrin | 400 | 190 | 377 | 4 | 94.3 | PR | |

| Hilltop | DDT | 195 | 75 | 40 | 2 | 20.5 | CR |

| Malathion | 195 | 75 | 145 | 4 | 74.4 | CR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 195 | 75 | 186 | 0 | 95.4 | PR | |

| Deltamethrin | 195 | 75 | 188 | 0 | 96.4 | PR | |

∗ CR = confirmed resistance, PR = possible resistance, and S = susceptible.

An. culicifacies showed resistance to DDT and malathion in all the terrains with the observed % mortality rate to DDT in the range of 14.5 to 23.4 and to malathion in the range of 67.0 to 74.4%. Possible resistance to alphacypermethrin was observed in all 4 terrains with a mortality rate in the range of 91.3 to 95.4%.

Based on the spray history in last 10 years in different districts, districts were categorized into three groups: group A-IRS with pyrethroids, 7 districts, viz., Panna, Hoshangabad, Singrauli, Khargone, Dhar, Alirajpur, and Shivpuri; group B-IRS with DDT, 3 districts, viz., Anuppur, Umaria, and Bhind; and group C-without IRS, 2 districts, viz., Tikamgarh and Datia (Table 5). An. culicifacies was found resistant to DDT and malathion registering low % mortality rates for DDT of 16.2, 15.6, and 37.6% in groups A, B, and C, respectively, while increased % mortality rates were registered for malathion at 69.2, 68.3, and 88.8%, respectively. To pyrethroid alphacypermethrin, the species showed possible resistance in groups A and B with % mortality in the range of 90.2 and 96.2, respectively, but was susceptible in group C with 98.5% mortality. Statistical analysis of mortalities against alphacypermethrin between the sprayed group (A) and the no spray group (C) was highly significant (chi sq. = 15.36, p < 0.0001) and with the DDT sprayed group (B) (chi. Sq. = 11.15, p, 0.001) and no significance was seen in alphacypermethrin mortality when compared with the no spray (C) and the DDT sprayed (B) group (chi. Sq. = 2.44, p=0.118). The species showed possible resistance to deltamethrin with % mortality in the range of 95.2 and 97.1% in groups A and B, respectively, but was completely susceptible in group C.

Table 5.

Susceptibility status of An. culicifacies in the districts grouped under different categories based on IRS.

| Villages with different insecticide sprays | Insecticide | No. of mosquitoes exposed | No. of mosquitoes dead | % mortality | Susceptibility status∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Control | Test | Control | ||||

| Group A—pyrethroid IRS since last 5–10 years and earlier with DDT IRS-7 districts (Singrauli, Panna, Hoshangabad, Khargone, Dhar, Shivpuri, and Alirajpur) | DDT | 970 | 445 | 157 | 5 | 16.2 | CR |

| Malathion | 970 | 445 | 671 | 7 | 69.2 | CR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 970 | 445 | 875 | 9 | 90.2 | PR | |

| Deltamethrin | 970 | 445 | 923 | 9 | 95.2 | PR | |

|

| |||||||

| Group B—DDT spray since last 5–10 years—3 districts (Anuppur, Bhind, and Umaria) | DDT | 315 | 105 | 49 | 1 | 15.6 | CR |

| Malathion | 315 | 105 | 215 | 1 | 68.3 | CR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 315 | 105 | 303 | 3 | 96.2 | PR | |

| Deltamethrin | 315 | 105 | 306 | 3 | 97.1 | PR | |

|

| |||||||

| Group C—no spray since last >20 years—2 districts (Tikamgarh and Datia) | DDT | 205 | 75 | 77 | 1 | 37.6 | CR |

| Malathion | 205 | 75 | 182 | 2 | 88.8 | CR | |

| Alphacypermethrin | 205 | 75 | 202 | 2 | 98.5 | S | |

| Deltamethrin | 205 | 75 | 205 | 2 | 100.0 | S | |

∗ CR = confirmed resistant, PR = possible resistant, and S = susceptible.

4. Discussion

Insecticide resistance is becoming a limiting factor for effective malaria vector control for national programmes worldwide, especially in view of the committed elimination of malaria in this decade by 2030. Presently, about 125 species of mosquitoes are documented to show resistance to one or more insecticides.

Raghavendra et al. [22] reviewed the status of insecticide resistance among the major malaria vectors in India in the last quarter century (1991–2016) based on the available information from published and unpublished reports. Resistance to DDT in An. culicifacies is widespread in the country [5, 6], and resistance to malathion is widespread in the districts in the states of Maharashtra [8], Gujrat [23, 24], Andhra Pradesh [24], Uttar Pradesh [9], and Madhya Pradesh [13]. There are a few reports of resistance to synthetic pyrethroids in various parts of the country [10–14]. Resistance to malathion was detected in five districts of Andhra Pradesh, nine districts of Odisha, and possible resistance in two districts of Jharkhand, 4 districts of Odisha, and 4 districts of West Bengal. An. culicifacies was found susceptible to malathion in two districts of Jharkhand and six districts of Odisha, resistant to deltamethrin in four districts of Andhra Pradesh, with possible resistance in 10 districts of Odisha, and susceptible to deltamethrin in some districts of Odisha, Jharkhand, and West Bengal [25].

In the present study, in Madhya Pradesh, An. culicifacies the main malaria vector was found resistant to DDT 4% in all the 12 districts surveyed and resistant to malathion in 11 districts, except in Datia district where the species is reported possibly resistant. The species was reported resistant to alphacypermethrin in two districts Dhar and Alirajpur. This vector was found susceptible to both deltamethrin and alphacypermethrin in three districts, i.e., Anuppur, Panna, and Tikamgarh. Possible resistance was found to alphacypermethrin in seven districts, namely, Singrauli, Umaria, Hoshangabad, Datia, Shivpuri, Bhind, and Khargone, and to deltamethrin in eight districts, viz., Singrauli, Umaria, Hoshangabad, Khargone, Alirajpur, Dhar, Shivpuri, and Bhind. Thus, the species was resistant to DDT and malathion in all the districts while it was mostly possible resistant to pyrethroids.

It may be stated that DDT has been sprayed in these areas in surveyed districts since the inception of the national malaria control activities in the early 1950s. Decreased mortality in An. culicifacies to pyrethroids was found in areas that received alphacypermethrin IRS in the last 5–10 years. In all the areas, the species in different districts have shown resistance to DDT and malathion. However, in areas without pyrethroid indoor spray, the species registered possible resistance and were susceptible to pyrethroids, alphacypermethrin, and deltamethrin in the range of 96.2 to 100%. Malathion was not sprayed regularly in these areas and the observed resistance to malathion could be due to possible selection by its use in agriculture/forestry in the absence of its use in public health sprays but needs further investigation.

To date, DDT, malathion, deltamethrin, alphacypermethrin, and lambda cyhalothrin are the most commonly used insecticides for vector control in public health in India, and other pyrethroid insecticides, namely, cyfluthrin and bifenthrin, are also recommended for use in antimalaria sprays [26]. Deltamethrin and alphacypermethrin impregnated LLINs are in extensive use in India in different states of the country, and Madhya Pradesh is receiving the LLINs in 2019 in all endemic districts.

The resistance in mosquitoes may develop due to changes in their enzyme systems resulting in more rapid detoxification or sequestration of the insecticide or due to mutations in the target site preventing the insecticide target site interaction [27]. Spraying of insecticides without proper understanding of the prevailing resistance mechanism may lead to increased vector resistance and failure of vector control intervention. In India, end-point replacement of insecticides is practiced after failure of control of a given class of insecticide resulting in multiple resistance in malaria vectors [28].

5. Conclusion

Results of the present study in 12 districts of Madhya Pradesh indicate that An. culicifacies is reported resistant in all the districts to DDT and to malathion, while to pyrethroids, alphacypermethrin, and deltamethrin the species is reported mostly possible resistant. Owing to the dynamics of development of resistance as evidenced from the above study, there is a need for regular monitoring of insecticide susceptibility in malaria vectors for implementing effective disease vector management strategies. However, studies to verify the impact of IRS with good coverage on transmission of disease are needed before deciding on a change of insecticide in conjunction with epidemiological data [26]. In addition, insecticide molecules with novel modes of action belonging to new classes of insecticides and insecticide mixtures such as neonicotinoid and pyrrole including carbamate class of insecticides for IRS and LLIN interventions are in development/trials. These molecules need to be adapted for vector control in our country to keep the date for elimination. Furthermore, it needs to be emphasized that the regulatory norms being followed for the introduction of interventions need to be reviewed for faster introduction. This will facilitate to preserve the gains achieved so far and pave the way for a faster impact on the transmission of malaria and disease control, ultimately leading to malaria elimination by date.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the technical staff and project staff of the ICMR-NIRTH Jabalpur for their help in lab and field work and acknowledge the valuable support of the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme and the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Madhya Pradesh. The authors sincerely acknowledge the support of the district malaria officers of the concerned districts of Madhya Pradesh. The study received the grant (no. e-77197) from the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, to carry out the research work. The support is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability

All the data are reported in the manuscript. The hardcopy of the data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure

The funding agency does not have any role in the planning and execution of the study or in the preparation and publication of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

A. K. M, M. R. A. D., and K. R. designed the study; A. K. M. and G. C performed the sample collection and experiments; A. K. M., P. K. B, G. C., and K. R. analyzed the data; A. K. M and H. J. P. K. B. wrote the manuscript; and A. D., P. K. B., A. K. M., M. R. K. R. H. J, and G. C. reviewed the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO. World Malaria Report 2018 . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275867/9789241565653-eng.pdf?ua=l . [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Vector Borne Diseases Control Programme. Directorate of Health Services . Delhi, India: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 2020. http://nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/malsituation . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma V. P. Fighting malaria in India. Current Science . 1998;75(11):1127–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raghavendra K., Barik T. K., Reddy B. P. N., Sharma P., Dash A. P. Malaria vector control: from past to future. Parasitology Research . 2011;108(4):757–779. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma V. P., Chandrahas R. K., Ansari M. A., et al. Impact of DDT and HCH spraying on malaria transmission in villages with DDT and HCH resistant Anopheles culicifacies. Indian Journal of Malariology . 1986;23(1):27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S. N., Shukla R. P., Raghavendra K. Susceptibility status of An. fluviatilis and An. culicifacies to DDT, deltamethrin and lambdacyhalothrin in District Nainital, Uttar Pradesh. Indian Journal of Malariology . 1999;36(3-4):90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deobhankar R. B., Palkar N. D. Magnitude of DDT resistance in Anopheles culicifacies in Maharashtra State. Journal of Communicable Diseases . 1990;22(1):p. 77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vittal M., Bhate M. R. Bioassay tests on the effectiveness of malathion spraying in Aurangabad town, Maharashtra. Indian Journal of Malariology . 1981;18:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla R. P., Sharma S. N., Bhat S. K. Malaria outbreak in bhojpur PHC of district Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of Communicable Diseases . 2002;34(2):118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittal P. K., Adak T., Singh O. P., Raghavendra K., Subbarao S. K. Reduced susceptibility to deltamethrin in Anopheles culicifacies sensu lato, in Ramnathapuram district, Tamil Nadu–Selection of a pyrethroid-resistant strain. Current Science . 2002;82(2):185–188. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh O. P., Raghavendra K., Nanda N., Mittal P. K., Subbarao S. K. Pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles culicifacies in Surat district, Gujarat, west India. Current Science . 2002;82(5):547–550. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma S. K., Upadhyay A. K., Haque M. A., Singh O. P., Adak T., Subbarao S. K. Insecticide susceptibility status of malaria vectors in some hyperendemic tribal districts of Orissa. Current Science . 2004;87(12):1722–1726. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra A. K., Chand S. K., Barik T. K., Dua V. K., Raghavendra K. Insecticide resistance status in Anopheles culicifacies in Madhya Pradesh, central India. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases . 2012;49(1):39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatt R. M., Sharma S. N., Barik T. K., Raghavendra K. Status of insecticide resistance in malaria vector, Anopheles culicifacies in Chhattisgarh state, India. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases . 2012;49(1):36–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh N., Chand S. K., Bharti P. K., et al. Dynamics of forest malaria transmission in Balaghat district, Madhya Pradesh, India. PLoS One . 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073730.e73730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vectors. Bio-efficacy and persistence of insecticides on treated surfaces. Report of the WHO informal consultation. WHO/CDC/MAL/98 . 1998;12:p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Manual of Practical Entomology in Malaria, Vector Bionomics and Organization of Antimalaria Activities, Pt II . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Offset Publication; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wattal B. L., Kalra N. L. Regionwise pictorial keys to the female Indian Anopheles. Bulletin of National Society India Malarial Mosquito Borne Diseases . 1961;9(2):85–138. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma S. N., Shukla R. P., Mittal P. K., Adak T., Subbarao S. K. Insecticide resistance in malaria vector Anopheles culicifacies in some tribal districts of Chhattisgarh, India. Current Science . 2007;92(9):1280–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Test Procedures for Insecticide Resistance Monitoring in Malaria Vector Mosquitoes . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241505154/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbott W. S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. Journal of Economic Entomology . 1925;18(2):265–267. doi: 10.1093/jee/18.2.265a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raghavendra K., Velamuri P. S., Verma V., et al. Temporo-spatial distribution of insecticide-resistance in Indian malaria vectors in the last quarter-century: need for regular resistance monitoring and management. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases . 2017;54(2):p. 111. doi: 10.4103/0972-9062.217613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yadava R. L., Rao C. K., Biswas H. Field trial of cyfluthrin as an effective and safe insecticide for control of malaria vectors in triple insecticide resistant areas. Journal of Communicable Diseases . 1996;28(4):287–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghavendra K., Vasantha K., Subbarao S. K., Pillai M. K., Sharma V. P. Resistance in Anopheles culicifacies sibling species B and C to malathion in Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat States, India. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association . 1991;7(2):255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghavendra K., Barik T. K., Sharma S. K., et al. A note on the insecticide susceptibility status of principal malaria vector Anopheles culicifacies in four states of India. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases . 2014;51(3):230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Vector Borne Diseases Control Programme (NVDBCP) Delhi, India: NVDBCP; 2009. Change of insecticide (annexure B) https://nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/Malaria-Operational-Manual-2009.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemingway J., Hawkes N. J., McCarroll L., Ranson H. The molecular basis of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology . 2004;34(7):653–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghavendra K., Verma V., Srivastava H. C., Gunasekaran K., Sreehari U., Dash A. P. Persistence of DDT, malathion & deltamethrin resistance in Anopheles culicifacies after their sequential withdrawal from indoor residual spraying in Surat district, India. Indian Journal of Medical Research . 2010;132(3):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are reported in the manuscript. The hardcopy of the data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.