ABSTRACT

This article describes the efforts made by the Israeli government to contain the spread of COVID-19, which were implemented amidst a constitutional crisis and a yearlong electoral impasse, under the leadership of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was awaiting a trial for charges of fraud, bribery, and breach of trust. It thereafter draws on the disproportionate policy perspective to ascertain the ideas and sensitivities that placed key policy responses on trajectories which prioritized differential policy responses over general, nation-wide solutions (and vice versa), even though data in the public domain supported the selection of opposing policy solutions on epidemiological or social welfare grounds. The article also gauges the consequences and implications of the policy choices made in the fight against COVID-19 for the disproportionate policy perspective. It argues that Prime Minister Netanyahu employed disproportionate policy responses both at the rhetorical level and on the ground in the fight against COVID-19; that during the crisis, Netanyahu enjoyed wide political leeway to employ disproportionate policy responses, and the general public exhibited a willingness to tolerate this; and (iii) that ascertaining the occurrence of disproportionate policy responses is not solely a matter of perception.

Keywords: Disproportionate response, overreaction, underreaction, rhetoric, Covid-19, Israel, netanyahu

Introduction

The Israeli government has successfully curbed the spread of the first wave of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). From the early stages of COVID-19 spread in Israel, the government implemented a combination of stringent social distancing measures, complete closure of the education system, cessation of passenger flights to Israel, strict curfews and lockdowns, as well as a near-complete shuttering of the economy, and, at the time of writing (31 May 2020), the number of deaths stands at 285 (Ministry of Health [MoH], 2020a). As the Israeli government began implementing these measures in late January 2020, it was experiencing a constitutional crisis that was exacerbated by a yearlong electoral impasse. Indeed, following two consecutive elections before the pandemic and a third that was held immediately after its initial outbreak, the government – comprised of right-wing and ultra-Orthodox religious parties – fell short of winning the majority needed to form a new coalition government. This unique situation, which occurred amid deep global anxiety regarding the spread of the coronavirus, resulted in great uncertainty, and the situation was further aggravated by the fact that the head of the Israeli care-taker government, Benjamin Netanyahu, was scheduled to appear in court on 17 March 2020, on charges of fraud, bribery, and breach of trust.1 Thus, the conditions were ripe for political considerations to intermingle with the definition of policy problems as well as the selection of policy measures in the fight against COVID-19.

Regarding health system capacity, although Israel has faced serious emergency management challenges, especially wars and major terrorist attacks, its healthcare system was not prepared for an epidemic. A state audit report published on 23 March 2020, concluded that the MoH, the Health Management Organizations, and the hospital system were not fully prepared for a pandemic flu outbreak despite a 2005 government decision regarding the need for preparedness. It also highlighted the shortage of hospital beds, isolation rooms, staffing, and medications, in addition to ill-equipped intensive care units and a lack of cooperation between the MoH and the Ministry of Defense (MoD) (Office of the State Comptroller and Ombudsman of Israel, 2020, p. 518).

Drawing on the Israeli experience, this article aims to describe how events unfolded since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; to analyze how new information regarding the spread of the virus influenced the policy measures employed to contain the pandemic; to ascertain the ideas and sensitivities that placed key policy responses on trajectories which prioritized differential responses over general, nation-wide solutions (and vice versa), even though data in the public domain supported the selection of opposing policy solutions on epidemiological or social welfare grounds; and to gauge the implications of these policy choices for the disproportionate policy perspective (Maor, 2017a, 2017b). This perspective is especially relevant in the Israeli case in light of a statement made by Netanyahu at an early stage of the pandemic, according to which he ‘instructed [health officials] to overreact, rather than underreact,’ because ‘this epidemic is perhaps one of the most dangerous in the last 100 years.’2 The Israeli example therefore provides a test case of a unique pathway to policy change (Weible et al., 2020) – namely, deliberative disproportionate policy response.

This paper argues that Netanyahu deliberately employed disproportionate policy responses (e.g., Maor 2019a, 2019b) both at the rhetorical level and on the ground. At the rhetorical level, Netanyahu employed policy overreaction rhetoric, seizing the ‘creeping crisis’ (Boin, Ekengren, & Rhinard, 2020) to continually step up existential warnings by envisaging a plague of medieval proportions. Netanyahu combined this rhetoric with appeals to his rival from the opposition, Benny Gantz, to join him in an ‘emergency unity government’ in order to help save Israel from the virus. On the ground, three disproportionate policy measures were employed. First, a deliberate policy underreaction was recorded when returning travelers from the U.S. were exempted from the quarantine restrictions imposed on travelers returning from Europe between February 26 and 4 March 2020, even though most of the 24 million travelers who passed through Ben Gurion airport in 2019 were traveling to and from Europe and the US. There was therefore a gap in policy from February 26 until March 9, when Israel sealed itself off from international travel, which ‘contributed substantially more to the spread of the virus in Israel than would be proportionally expected’ (Miller, Martin, & Harel et al., 2020). This gap, according to Minister of Tourism Yariv Levin, resulted from Israel’s desire to maintain good relations with the United States. It may also have been due to the pressure exerted by ultra-Orthodox politicians to allow hundreds of infected yeshiva students from New York unregulated access to Israel.

Second, a deliberate policy overreaction was recorded when a national curfew was enforced during the Passover holiday, while epidemiological data indicated that a differential response covering in particular ultra-Orthodox localities, which were hotspots for the spread of the virus, should have been selected. In those localities, for example, the doubling time of the number of infected persons ranged from 2.5 to 3.9 days (National Center for Information and Knowledge for the Fight against Corona 2020a, p. 3). This policy overreaction was employed, according to Prime Minister Netanyahu, in order to avoid stigmatizing the ultra-Orthodox community. It may also have been due to his wish to avoid angering its representatives in the government. Third, a deliberate policy overreaction was recorded when a ‘Coronavirus grant’ was paid to all families with up to four children aged 0–17, benefiting ultra-Orthodox households especially, although income inequality data supported means-testing to target those most in need of this grant.

These examples of deliberate disproportionate responses indicate (i) that the disproportionate policy responses reflected political considerations benefiting Prime Minister Netanyahu; (ii) that Netanyahu enjoyed wide political leeway to employ disproportionate policy responses during the crisis, and the general public demonstrated a willingness to tolerate such responses; and (iii) that ascertaining the occurrence of disproportionate policy responses is not solely a matter of perception but rather can be gauged objectively, based on publicly available information.

The paper is structured as follows. The first section describes the fight against COVID-19 in Israel amidst political and constitutional crises and analyzes the impact of new information on the policy decisions made during this fight. It is divided into three subsections, namely, the background; the initial spread of COVID-19, early policy moves, and the elections for the 23rd Knesset; and the further spread of COVID-19 and the constitutional crisis. The second section ascertains the ideas and sensitivities that placed some policy responses on disproportionate policy trajectories, gauging the consequences and implications of the policy choices made in the fight against COVID-19 for the disproportionate policy perspective. The final section concludes.

The fight against COVID-19 amidst political and constitutional crises: a historical analysis

The Background

Israel is a parliamentary democracy consisting of a legislative branch (the Knesset – Israel’s parliament), an executive branch (the prime minister and government), and a judiciary. The Israeli parliamentary system is characterized by a government that is drawn from parliament and that can be toppled by a constructive vote of confidence. The fact that the government is drawn from the parliament and relies upon a parliamentary majority implies a lack of clear-cut functional boundaries between the legislative and executive branches. Consequently, the former follows the legislative lead of the latter, and the legislative branch’s oversight of the government is relatively weak.

In recent years, the very meaning of the principle of ‘separation of powers’ has been contested, with the partial fusion of the legislative and executive branches inviting numerous petitions to the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ). In addition, many political issues remain unresolved due to the contentious political climate and the intensifying ideological polarization in Israeli society. As a result, the HCJ has increasingly found itself embroiled in adjudicating issues that remain unresolved by the political system. Judicial review of legislative and executive acts has become a topic of public debate over the last decades, with certain voices claiming that an unelected judiciary is overriding the desires of the general public. This debate, and the constitutional crisis that has intensified alongside it, reached a zenith during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Due to Benjamin Netanyahu’s failure to form a coalition that enjoyed the confidence of the Knesset following both the elections for the 21st Knesset in April 2019 and the subsequent elections for the 22nd Knesset in September 2019, the incoming pandemic was managed by a care-taker government led by Netanyahu.3 At the same time, Netanyahu himself, who has been prime minister since 2009, and previously held the position from 1996 to 1999, was facing three indictments on charges of fraud, bribery, and breach of trust, and his trial was due to begin in mid-March 2020. His legal predicament was a prominent issue in the campaigns preceding the elections for the 23rd Knesset, which took place on March 2. A petition was submitted to the HCJ asking it to declare that Netanyahu’s indictments render him legally unfit to be called upon to form a governing coalition, in the event that his outgoing coalition should gain sufficient seats to do so. This petition was dismissed by the HCJ two months before the elections (2 January 2020) on the grounds that it was ‘theoretical and premature.’4 Thus, the outbreak of COVID-19 in Israel occurred as the country was experiencing a political deadlock, led by a government that had not enjoyed democratic legitimacy for over a year and a prime minister about to face a criminal trial.

The initial spread of COVID-19, early policy moves, and the elections for the 23rd Knesset

In late January 2020, soon after it became apparent that an epidemic was raging in China, the MoH issued a series of escalating warnings regarding travel to China and took some legal steps to widen the ministry’s emergency powers. The initial policy was intended to prevent the arrival of the virus in the country or at least delay the virus’ spread within Israel. In early February, the Israeli public became aware that a group of their countrymen were aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which was anchored near the coast of Japan in quarantine. On February 16, the first known cases of Israelis infected with COVID-19 were 2 (later 4) passengers aboard the Diamond Princess.5 They were hospitalized in Japan, and 11 other Israeli passengers from the ship returned to Israel. Upon their arrival, on February 21, one of them was diagnosed as carrying the virus, becoming the first COVID-19 case in the country. In the following 10 days, up until the elections (March 2), the number of cases increased to 10, while the government continued to pursue a policy of prevention by mandating self-quarantine for travelers arriving from several Asian countries.

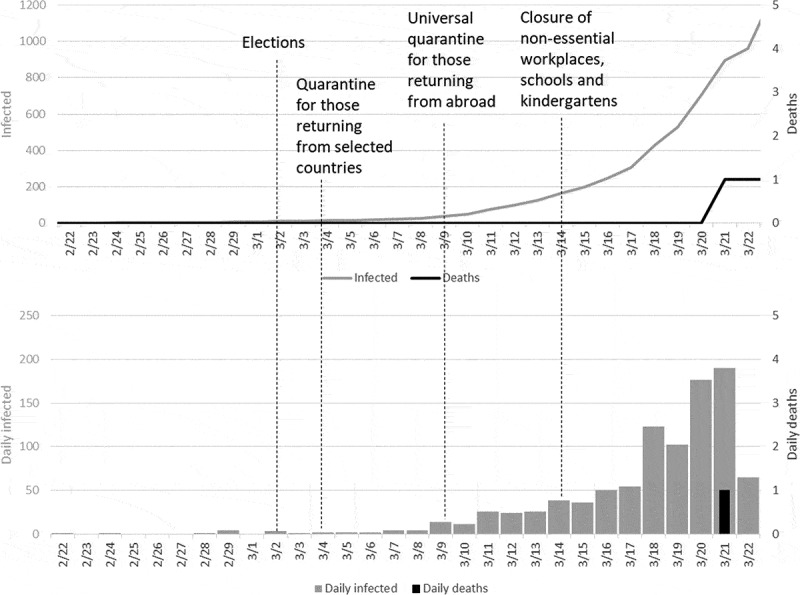

The elections took place on March 2, with a turnout of 71%, but the political deadlock remained largely unchanged. While the Likud Party increased its power, this came at the expense of its coalition partners. In terms of political blocs, the right-wing block gained 58 seats while the opposing parties obtained 62 seats – just over half of the 120 seats in the Knesset. However, the opposing parties, which constituted a heterogeneous mix of center-right, center, left, and The Joint Arab List, lacked ideological cohesiveness, while the right-wing bloc, led by the Likud Party with the support of religious Zionist parties and ultra-Orthodox parties, was more ideologically cohesive. As the results of the election became apparent over the week that followed, so did the indications that the COVID-19 virus had spread within the population. Figure 1 presents the timeline of political developments vis-à-vis the spread of the pandemic in Israel. It is evident that the elections took place just before the rate of infections began to rise; that the electoral results became apparent as the rate of infection became noticeable; and that the government did not wait to take action.

Figure 1.

The first month of the epidemic (since the first case) in Israel. The upper panel presents the accumulated number of infected cases (gray line) and deaths (black line); the bottom panel presents the daily increase in cases (gray) and deaths (black). Note that infection cases correspond to the gray Y-axis on the right, and the deaths correspond to the black Y-axis on the left.

As the virus was spreading, it was necessary to decide on the list of countries requiring quarantine for returning passengers. On February 2, the MoH ordered that travelers returning from China should be placed under a 14-day quarantine. On February 16, Thailand, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Macau were added to the list of countries requiring quarantine. On February 26 (2 known cases), the MoH extended the order to include travelers returning from Italy, and on March 4 (15 known cases) France, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, and Austria were added to the list.6 On March 6 (27 known cases), it was reported that officials in the MoH were considering extending the quarantine requirement to those returning from the U.S. and additional countries in Europe (Netherlands, Belgium, and Norway).7 Government officials clarified that these decisions should be approved by the Prime Minister’s Office, while rejecting claims that political considerations were involved.8 On March 8 (40 known cases), in a meeting with Netanyahu, the MoH advocated extending the quarantine requirement to all returning travelers. The prime minister conducted talks with the U.S. vice-president about the matter. At that time, the government did not impose quarantine regulations on those returning from the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) conference, which took place in New York City and was attended by 18,000 participants,9 despite the fact that some participants at the conference tested positive for coronavirus.10 Finally, on the evening of March 9 (44 known cases), it was announced that the quarantine requirement would be applied to all travelers returning from abroad. However, the order was not retrospective, meaning that it did not apply to those who had returned prior to that date.11

Further spread of COVID-19 and the constitutional crisis

On March 11 (97 known cases), the Blue and White Party – the largest party in the bloc that gained 62 seats – was close to securing the support of a majority of new Knesset Members for the recommendation that the President task its leader, Benny Gantz, with forming a coalition. From this point onward the political story became embroiled with the policy response to COVID-19. While any crisis triggers responses at strategic and operational levels (Boin & ‘T Hart, 2010), in this case policy responses to the national public health crisis were combined with a very high-stakes game of political survival. The crisis was met by a Prime Minister who, while leading the efforts to contain it, was in a severe conflict of interest that could have tilted policy choices between efforts to curb the spread of the virus and attempts to secure his political and personal future.

Thus, it is no surprise that the leaders of the opposition parties saw the COVID-19 outbreak as a crisis that ‘fell from the sky,’ a gift for Netanyahu. On the evening of March 11 (97 known cases), Netanyahu held a press conference, together with the minister of health and senior officials at the MoH. This was the first in a series of public events at which Netanyahu used the bully pulpit of nationally televised announcements, without allowing follow-up questions from the press, to address the public about the coronavirus crisis. He portrayed a plague of medieval proportions, stressing its unprecedented nature. Another feature of these public appearances included repeated appeals to the Blue and White Party to join the Likud Party in forming a national unity government. In addition, all the participants at these events, including Netanyahu himself, praised the prime minister for his astute management of the fight against the coronavirus.

On March 13 (153 known cases), the Blue and White Party requested that the care-taker Knesset Speaker – Yuli Edelstein (Likud) – hold a Knesset session at which a new Speaker would be elected. Edelstein refused to do so, arguing that traditionally the Speaker is elected at the first meeting of the new parliament, which normally takes place after the governing coalition is formed. Consequently, Knesset Speaker Edelstein delayed the convening of the Knesset, justifying this with the claim that it would avoid a situation in which an alternative Speaker would be elected by the new majority of the Knesset before coalition negotiations concluded and thus could belong to a party that is not part of the governing coalition. In such an eventuality, a majority of at least 90 out of 120 Knesset Members would be required to remove the Speaker, a number that is practically unattainable. In effect, Edelstein created a situation in which Netanyahu could manage the Coronavirus crisis without a functioning parliament, hence preventing a vote to replace Edelstein as Speaker and the passage of legislation that would disqualify Netanyahu from forming a government while under indictment, as well as preventing the parliament from overseeing the government’s use of emergency powers in the fight against COVID-19.12 The emergency measures implemented by the government included a late-night decision by the justice minister (Likud) to impose a state of emergency on the court system, forcing the judges of Netanyahu’s forthcoming trial to postpone its opening session by two months – to late May.13

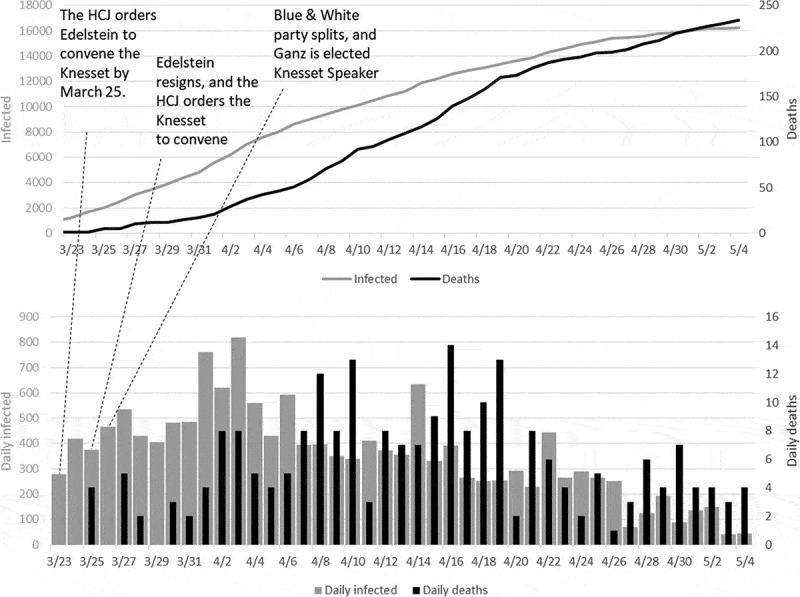

Edelstein’s objection to holding a Knesset session resulted in public criticism – mostly from the center-left – and a petition to the HCJ to compel the Speaker to hold a Knesset session that would vote on his replacement and establish the Arrangements Committee, which governs all parliamentary work between the date of the election and the formation of a new government. In an unprecedented decision, on March 23, the HCJ intervened and ordered Knesset Speaker Edelstein to convene the Knesset by March 25 (see timeline of events in Figure 2).14 In the evening of the deadline set by the Court, Edelstein resigned, citing undue political intervention on the part of the HCJ as the reason for this.15 An urgent petition to the HCJ that evening, supported by the Government’s Legal Counsel, the highest legal authority within the executive in Israel, led the Court to take another unprecedented decision, ordering that the Knesset convene the next day.16

Figure 2.

The apex of the epidemic in Israel (early days of April) and its decline. The upper panel presents the accumulated number of infected cases (gray line) and deaths (black line); the bottom panel presents the daily increase in cases (gray) and deaths (black). Note that infection cases correspond to the gray Y-axis on the right, and the deaths correspond to the black Y-axis on the left.

The final surprise in this constitutional crisis occurred on the following day. The Knesset was about to convene in order to elect a new speaker. It was assumed that this would be Knesset Member Meir Cohen (Blue and White Party), who was set to receive the support of all parties which did not belong to the right-wing bloc. Netanyahu, seeing that the new Knesset majority was about to assert its power, made a final offer to Benny Gantz and Gabi Ashkenazi – two of the leaders of the Blue and White Party – to join a unity government. In order to buy additional time, the Likud announced that it would support any Knesset Member from Gantz’s faction of the Blue and White Party as a candidate for Knesset Speaker. Gantz and Ashkenazi agreed to the offer, perhaps initially to gain more time.17 However, their consent to the Likud’s proposal sparked fierce objections within the Blue and White Party, leading its largest faction (Yesh-Atid) to split from the Blue and White alliance. That evening, Gantz was elected as Knesset Speaker, with the support of right-wing parties and some members of the Blue and White Party who joined him. This event split the main opposition to the right-wing bloc, and the establishment of a unity government was only a matter of time – a coalition agreement was indeed signed on April 20 (total deaths: 178), and the coalition was finally sworn in by the Knesset on May 17 (total deaths: 272).

Further control measures in the fight against COVID-19

The prime minister gave full reign to the extreme precautionary inclinations of the MoH. According to Minister of Health Yaakov Litzman, Netanyahu ‘responded to the fears [cultivated by] the MoH’s director general.’18 The latter’s main concern was to ensure that the health system, which has been underfunded, understaffed, and underequipped for the last decade (OECD 2016), would not be overwhelmed by patients in need of ventilation. MoH officials, both at official briefings and on media panels, continually warned of a looming catastrophe, raising the spectre of 10,000 deaths resulting from the pandemic.19 Consequently, large gatherings were banned, and citizens were advised on proper hand hygiene and social distancing. However, matters progressed swiftly: schools were closed entirely, individuals were restricted to moving no more than 100 meters from their dwelling place (except for essential purchases of food and medicines), and all ‘non essential’ enterprises were shut down, with no more than 15% of the workforce functioning. Further policy measures included a Passover holiday lockdown that prohibited intercity travel and family gatherings for celebrations.

At the ministerial level, the fight against COVID-19 was dominated by the MoH. Extant guidelines regarding the spread of epidemics in Israel (MoH and National Emergency Authority 2007), which accord a prominent role to the Home Front Command operating under the MoD, were ignored. Instead, Netanyahu relied solely on the MoH, overseen by the National Security Council (NSC), Israel’s central body for coordination, integration, analysis, and monitoring in the field of national security. The MoH’s aim during the outbreak (and at the time of writing) was to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by quelling the spread of the disease and minimizing mortality due to COVID-19. From that perspective, total lockdown was considered the optimal strategy, given the weaknesses of the healthcare system in terms of funding, staffing, and the shortage of ventilators and testing kits (Office of the State Comptroller and Ombudsman of Israel, 2020, p. 518).20 This extreme one-size-fits-all lockdown approach suited Netanyahu’s predicament and accorded with his efforts to fan the flames, signalling to the public that the most aggressive route had been selected in order to bring the pandemic under control.

Surprisingly, the emphases on fear and ‘flattening the curve’ were not supplemented by any clear strategy for testing, tracking, and isolating COVID-19 cases. Netanyahu prioritized cell-phone tracking, relying on the technical skills of the Shin Beit – Israel’s internal security service, under the authority of the Prime Minister’s Office – to find and notify citizens who might have been exposed to known cases and instruct them to enter isolation. On another front, Israel was slow to increase testing, despite Netanyahu’s pledge to rapidly reach a level of 30,000 tests per day. In addition, Israel lacked adequate PCR testing kits, and no policy was set in place regarding serological testing to determine the level of immunity in the population. The task of obtaining test kits and equipment from abroad was allocated to the Mossad – Israel’s mythological secret service agency, under the authority of the Prime Minister’s Office – despite the fact that the MoD has better experience in purchasing and logistics. Perhaps this was due to Netanyahu’s disinclination to give a highly visible role (and hence opportunities for credit claiming) to Minister of Defense Naftali Bennett, one of Netanyahu’s main political rivals (Maor, 2020a).

In this contentious political climate, the numbers of infected, ventilated, and deceased patients were released daily by the MoH, but data regarding the relative risks for different population groups were suppressed and this topic was not publicly discussed. At the end of March – two weeks after the general lockdown was imposed – the first decline in the infection rate was detected. Moreover, it became apparent that the epidemic was concentrated in relatively few localities, characterized mostly by a high share of ultra-Orthodox residents. This was not surprising. In the first weeks of the epidemic in Israel, some ultra-Orthodox communities resisted the ban on social gatherings and the closure of schools, and they did not observe the social distancing requirements in schools, yeshivas, and synagogues. These communities only began to observe the health regulations after the high morbidity rates in ultra-Orthodox communities in New York and Israel became known, in late March and early April.

As indicated in Figure 2, the infection rate reached its zenith in the early days of April, followed by a steady decline (until the time of writing). Note the time lag between the decline in morbidity rate (daily infected) and mortality rate (daily deaths). On April 19 (13,852 known cases and 192 dead), Netanyahu announced a limited lifting of the restrictions on economic activity, allowing sidewalk vendors to open and permitting physical exercise in pairs at distances of up to 500 meters from home. Yet schools remained closed, and, apart from the exception for exercise, people were not allowed to move further than one hundred meters from home. The government claimed that widening the number of businesses permitted to function was intended to increase the active workforce from 15%, under the more stringent restrictions on economic activity, to 30%, with the partial lifting, but the rationale for these particular proportions was not explained to the public. Under increasing pressure from the Ministry of Finance and economic stakeholders, on April 26, businesses, other than those in large malls, were allowed to open, with citizens advised to maintain social distancing and wear masks. The lifting of the restrictions on economic activity did not apply to open air markets, and a large demonstration took place in the Mahane Yehuda Market in Jerusalem, with angry proprietors wearing masks sporadically and clearly not observing social distancing. Furthermore, the insistence on blocking bereaved families from visiting their relatives’ graves on Memorial Day (April 27) was another example of policy inconsistency, because while military cemeteries were closed on that day, stores (e.g., IKEA) were allowed to open. This haphazard exit strategy stands in stark contrast to the extreme control exerted during the total shutdown of the economy. The consequences in terms of a second spike of the epidemic do not seem to have been systematically considered or explained to the public. However, it is clear that at the time of writing, the MoH is no longer the dominant actor among the government ministries in managing the crisis.

Still, Netanyahu’s strategy was successful. As already noted, his political opposition caved in and agreed to form a coalition government, which was sworn in on May 17, using the COVID-19 crisis as justification. How this development will affect the fight against the coronavirus remains to be seen, but it is telling that since the coalition agreement was signed (April 20), Prime Minister Netanyahu has apparently been paying less attention to MoH advice in making de-confinement decisions and instead paying more heed to economic stakeholders.

A disproportionate policy perspective on the fight against the Coronavirus

The Israeli experience of the fight against the coronavirus provides a few classic examples of deliberate disproportionate policy responses (e.g., Maor, 2019b; see also, 2020b). Before elaborating on this point, let us clarify that our analysis here is undertaken in light of a recent turn, whereby the concept of disproportionate policy response, and its two component concepts – policy over – and underreaction (Maor, 2012, 2014) – are re-entering the policy lexicon as types of intentional policy responses that are largely undertaken when political executives are vulnerable to voters and when there is uncertainty regarding the optimal policy choice (Maor, 2019b). In such cases, there is an increased likelihood that political considerations will intermingle with the definition of policy problems and goals, widening the window for a deliberate disproportionate response (Maor, 2019b, p. 11). At the heart of this conceptual turn lies the disproportionate policy perspective (Maor, 2017a), which provides the rationale that, under certain circumstances, disproportionate policy responses may be intentionally designed, implemented as planned, and at times successful in delivering the political benefits sought by the political executives who initiate them and in achieving policy goals. This perspective implies that ‘a disproportionate response in the policy domain may at times be a politically well calibrated and highly effective strategy because of the damage it inflicts on political rivals and/or its success in shaping voters’ perceptions favorably’ (Maor, 2019b, p. 5).

One of the biggest challenges faced by the Israeli public in the period between the first case of the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel was confirmed (February 21) and the occurrence of the first death (March 20), has been how to determine the starting point of the pandemic. This, in turn, created an opportunity for Netanyahu to strategically frame collective threats in the run-up to critical policy moves; to justify extra-ordinary measures by announcing the existence of a pandemic of medieval Black Plague proportions, when there was no evidence to suggest that this was actually the case; and, more importantly, to convince the public that a severe crisis was underway, one that would have potentially catastrophic consequences in the absence of immediate action.

Specifically, at the rhetorical level, Netanyahu employed policy overreaction rhetoric (Maor, 2018) by announcing early in the outbreak that he had ‘instructed [MoH officials] to overreact, rather than underreact.’21 At the same time, he stepped up existential warnings, arguing that the pandemic may prove to be the biggest threat to humanity since the Middle Ages (Channel 12 interview, 21 March 2020), that ‘we could reach a million infected within a month,’ that ‘there could also be 10,000 dead Israelis’ (March 25, an interview in Channel 12 news), and that, unlike the Holocaust, ‘we identified the danger of the coronavirus in time’ (Speech, Holocaust Remembrance Day Ceremony, Yad Vashem, 20 April 2020). This rhetoric created a collective sense of catastrophic crisis, with 76% of the public fearing infection,22 and facilitated an unprecedented level of public attention that was used as a political resource (Baumgartner & Jones, 1993), leaving little room for differing interpretations. Furthermore, Netanyahu appeared almost nightly on prime-time television to announce ever more aggressive measures, with no opportunity for follow-up questions. On March 12, he called for the formation of a national emergency government for a limited period, while evoking an atmosphere that recalled the eve of the 1967 war. ‘Together’, he claimed, ‘we will fight to save tens of thousands of citizens.’ Netanyahu’s policy overreaction rhetoric proved successful. First, there was mass acceptance of, and hence compliance with, the aggressive policy solutions devised by Netanyahu and the MoH’s director general, Moshe Bar Siman-Tov. Both Netanyahu and Bar Siman-Tov enjoyed high levels of public support, with Netanyahu’s job approval rating reaching 60%.23 Second, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Blue and White Party Chairman Benny Gantz formed a ‘national emergency government’ to fight the coronavirus pandemic.

Beyond rhetoric, the disproportionate policy perspective is designed, among other things, to help explain a complex reality in which political executives deliberately select policy over- or underreaction alternatives ‘on the ground.’ An example of deliberate policy underreaction in the fight against COVID-19 was the exemption of travelers returning from the U.S. from the quarantine restrictions imposed on travelers returning from Europe on February 26 and on 4 March 2020. Specifically, it was known that initial infection in Israel began following the entry of returning travelers from abroad (MoH 2020b, p. 4); that Israel has one main entry point, namely Ben-Gurion Airport; and that around 24 million travelers passed through this airport in 2019, traveling mostly to and from Europe and the US.24 As noted earlier, the policy adopted included 14-day home quarantine for travelers returning from Italy (February 16), and France, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, and Austria (March 4). No restrictions were placed on travelers arriving from the U.S. until March 9, when all those entering Israel were required to comply with the 14-day home quarantine. The consequences of this policy gap have emerged in a study tracking the dynamics of COVID-19 infection that uses full genome sequencing. Miller et al. (2020, p. 5) concluded that “[o]ver 70% of the clade introductions into Israel […] were inferred to have occurred from the U.S., while the remaining were mainly from Europe.ˮ Was this policy gap a deliberate policy decision? In a radio interview, Minister of Tourism Yariv Levin was the first official to admit publicly that politics and diplomacy played a role in this decision. When it came to the U.S., he said, ‘the relationship is especially sensitive, and when we make decisions regarding the United States, it is in coordination, and we won’t take any unilateral steps.’ Indeed, he called the U.S. “an ally, a responsible country,ˮ adding that ‘any decisions regarding that country need to be careful and cooperative.’25 This deliberate policy underreaction may also have been due to the pressure exerted by ultra-Orthodox politicians to allow hundreds of infected yeshiva students from New York unregulated access to Israel (Harel, 2020).

An example of deliberate policy overreaction is the rejection of a differential approach to controlling the spread of the virus, especially when new epidemiological information indicated that the ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak, as well as other ultra-Orthodox cities and neighborhoods in Jerusalem, were among the worst hit localities. Specifically, on April 5, two days before Passover, the National Center for Information and Knowledge for the Fight against Corona (2020a, p. 3) published a factsheet detailing the rapid infection rate in the ten worst-performing localities, seven of which were characterized by ultra-Orthodox populations. In these localities, the doubling time of the number of infected persons ranged from 3.9 (Upper-Modiin) and 2.9 (Bnei-Brak and Tiberius) to 2.5 days (Elad). A day later, the Center revealed that most infected persons in Jerusalem were concentrated in ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods. With approximately 47 infected persons per 10,000 residents, these neighborhoods came second place in Israel in the rate of infection for 10,000 people (National Center for Information and Knowledge for the Fight against the Corona, 2020b, p. 1). These findings called for the implementation of a selective policy, combining lockdowns and curfews in selected geographical areas where the spread of the virus was out of control.

However, in order to avoid stigmatizing the ultra-Orthodox community and to avoid angering its representatives in the Israeli government, including Minister of Health Yaakov Litzman and Minister of the Interior Aryeh Deri, the policy for the Passover holiday included a curfew on all Jewish localities in Israel, even those without any recorded infection. The justification for this policy move was recorded in a Zoom meeting of Prime Minister Netanyahu with the external team of experts on March 29. Netanyahu responded in the following manner to the suggestion that economic damage be minimized by implementing a differential lockdown covering only Bnei Brak and Jerusalem: ‘So you are saying, wait a moment, why make it [the lockdown] stricter? Go on, go after the ultra-Orthodox, and then you’ll see. I say that if you go after the ultra-Orthodox, you’ll immediately create an effect that they themselves are responsible for it [the spread of the virus], I can exclude them. An effect like that, in my opinion, can be lethal.’26 Indeed, ultra-Orthodox commentators claimed that imposing curfews solely on ultra-Orthodox communities could have transform the coronavirus into an anti-Haredi or anti-Semitic epidemic.27

Another example of deliberate policy overreaction concerned the Passover grant. At the outset, on a national level, the number of children aged 0–17 in households with children of this age averages 2.43 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2019). Households in ultra-Orthodox localities have the highest average numbers of children, among them Beit Shemesh (3.67), Bnei-Brak (3.5), and Jerusalem (2.99), while those in Tel Aviv have the lowest average (1.87) (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2019). A few days before Passover, Prime Minister Netanyahu pledged a special Passover grant to families – not subject to means testing – of 500 shekels per child for the first four children. This pledge was fully implemented by April 12. Needless to say, this universal grant was partly a waste of resources because money was not being spent on those most in need of it at a time of serious crisis.

The aforementioned examples of deliberate disproportionate policy responses indicate that ascertaining the occurrence of such responses is not solely a matter of perception. During a severe crisis, once information in the public domain calls for a certain policy, be it a lockdown or border restrictions, political executives can follow the advice of the relevant ministry, yet they may still have enough leeway to decide whether to employ the required policies in a differential or a general way. It is precisely here that political considerations can become interwoven with the policy measures employed. Needless to say, some disproportionate policy responses are indeed a matter of perception, yet the challenge is to identify those responses that contradict the public interest on the basis of the information available in the public domain, when no access is granted to information held solely by decision-makers.

The aforementioned examples also demonstrate that deliberate disproportionate responses may occur alongside unintentional disproportionate responses, which occur due to errors of commission or omission. The errors in handling the fight against COVID-19 in Israel included a lack of focus during the early stages of the outbreak on isolating the most vulnerable, among them the elderly, especially those residing in nursing homes, and the inability to scale up COVID-19 testing and deliver on Netanyahu’s promise to reach 30,000 tests per day.

Conclusions

The case of the fight against COVID-19 in Israel brings to the fore both the wide political leeway that democratically-elected leaders enjoy and the willingness of the general public to tolerate, at times, disproportionate policy responses. Once the global coronavirus outbreak reached Israel, which was in the midst of a constitutional crisis exacerbated by a yearlong electoral impasse, a window of opportunity opened for political considerations to intermingle with the definition of policy problems and goals as well as with the policy measures employed. As was demonstrated here, Netanyahu skillfully seized this opportunity and, while adhering to the alarmist policy solutions devised by the MoH, undertook political moves that reached out to his political rival but simultaneously maintained the stability of his right-wing bloc, especially the loyalty of his ultra-Orthodox religious partners, and sustained Israel’s links with the U.S. Administration. In parallel, Netanyahu employed policy overreaction rhetoric to shape the way the Israeli public perceived both the potential scale of the pandemic and the response of his government to the spread of the coronavirus.

The Israeli case also shows that disproportionate policy response is not random. Incumbent leaders try to minimize economic, social, and health threats, but when the prime minister’s political survival is on the line, and a global crisis creeps in, a proportionate response, such as the initial, aggressive policy moves undertaken by the Israeli government in the fight against COVID-19, can intermingle with deliberate disproportionate responses. This policy mix derives from the political temptation that is always present when elected executives are vulnerable to voters and when there is uncertainty regarding which policy solutions should be employed.

Finally, the Israeli case demonstrates extreme uncertainty in numerous arenas – the international health arena, with the workings of the virus vexing the scientific and medical communities; the domestic health arena, with the spread of the virus; the political arena; and the judicial/constitutional arena. This extreme uncertainty clouds the ability of the public to identify elected executives’ conflicting interests in pursuing disproportionate policy responses. In calling attention to these uncertainties, and to elected executives’ incentives to ramp up certain threats, we seek to guide future research in tracing and uncovering the full spectrum of government responses: proportionate policy responses, nonintentional disproportionate policy responses, unintentional disproportionate policy responses, and deliberate disproportionate policy responses.

Moshe Maor, Professor of Political Science & Wolfson Family Chair Professor of Public Administration, Department of Political Science, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem, Israel.

Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science & The Federmann School of Public Policy, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem, Israel.

David Chinitz, Professor, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ein Kerem, Jerusalem, Israel.

Footnotes

The shutdown of the justice system due to the coronavirus led to a delay in the court appearance, which was rescheduled to take place on 24 May 2020.

Benjamin Netanyahu, Press Conference, 4 March 2020. Reported in Israel Hayom, March 5.

According to Section 30(b) of Basic Law: The Government, the powers of caretaker governments are not restricted in any way due to the governance continuity principle.

Dr. Orna Bari (and others) v. The Government Legal Counsel (and others) (2 January 2020) HCJ 8145/19.

YNET, 16 February 2020: https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5678645,00.html.

YNET, 4 March 2020: https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5688829,00.html.

Ma’ariv, 6 March 2020: https://www.maariv.co.il/news/health/Article-752430.

TheMarker , 7 March 2020: https://www.themarker.com/news/health/1.8635859.

AIPAC 2020 website, https://event.aipac.org/policyconference-about

YNET, 8 March 2020: https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5690957,00.html.

Globes, 9 March 2020: https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001321094.

The government resorted to 70 emergency regulations (from March 15 to 27 April 2020) while facing a Knesset that had been effectively shut down due to the coronavirus.

YNET, 15 March 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5694834,00.html.

The Movement for Government Quality in Israel (and others) v. Knesset Speaker (and others) (23 March 2020) HCJ 2144/20.

Ma’ariv, 25 March 2020, https://www.maariv.co.il/elections2020/news/Article-756173.

The Movement for Government Quality in Israel (and others) v. Knesset Speaker (and others) (25 March 2020) HCJ 2144/20.

Israel Public Broadcasting Corporation (Kan), 26 March 2020, https://www.kan.org.il/item/?itemid=68781.

Israel Public Broadcasting Corporation (Kan), 17 May 2020, http://kan.org.il/item/?temid=71229.

Israel Public Broadcasting Corporation (Kan), 17 May 2020, http://kan.org.il/item/?temid=71229.

MoH officials probably still remembered that in the mid-2000's the Ministry of Justice charged some of their colleagues for the failure to regulate baby formulas, which led to irreparable damage in a number of infants, and that they were subsequently found guilty of malpractice.

Benjamin Netanyahu, Press Conference, 4 March 2020. Reported in Israel Hayom, March 5.

Israel Democracy Institute, 30.3.2020, https://www.idi.org.il/articles/31153

Ma’ariv, 4 April 2020, https://www.maariv.co.il/news/politics/Article-761729; Israel

Democracy Institute, 27 February 2020, https://www.idi.org.il/articles/30883; Israel Democracy Institute, 30 March 2020, https://www.idi.org.il/articles/31153

Globes, 7 January 2020, https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001313973

Haaretz, English Edition, 8 March 2020. Available online at:

Channel 13 News, 23.5.2020. https://13news.co.il/item/news/domestic/health/ministry-of-health-coronavirus-1065246/

Ha’Modia, 13 April 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1993). Agendas and instability in American politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A., & ‘T Hart, P. (2010). Organizing for effective emergency management: Lessons from research. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 69, 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M., & Rhinard, M. (2020). Hiding in plain sight: Conceptualizing the creeping crisis. Risks, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy. doi: 10.1001/rhc3.12193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics . (2019). Selected data for the International Child Day 2019. Press Release, 18.11.2019,(in Hebrew). Retrieved from https://old.cbs.gov.il/reader/newhodaot/hodaa_template.html?hodaa=201911349

- Harel, A. (2020). The lockdown is the message. Haaretz, May 28, pp. 1 & 7.

- Maor, M. (2012). Policy overreaction. Journal of Public Policy, 32, 231–259. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2014). Policy persistence, risk estimation and policy underreaction. Policy Sciences, 47, 425–443. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2017a). The implications of the emerging disproportionate policy perspective for the new policy design studies. Policy Sciences, 50, 383–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2017b). Disproportionate policy response. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-168 [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2018). Rhetoric and doctrines of policy over- and underreactions in times of crisis. Policy and Politics, 46, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2019a). Overreaction and bubbles in politics and policy. In A. Mintz & L. Terris (Eds.), Oxford handbook on behavioral political science. Oxford Handbooks Online, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2019b). Deliberate disproportionate policy response: Towards a conceptual turn. Journal of Public Policy, 1–24. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X19000278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2020a). Policy overreaction styles during manufactured crises. Policy and Politics. doi: 10.1332/030557320X15894563823146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2020b). The political calculus of bad governance: The fight against COVID-19 in Israel. Working Paper. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D., Michael. A. M., Harel, N., ., Kustin, T., Tirosh, O., Meir, M., Sorek, N., Gefen-Halevi, S., Amit, S., Vorontsov, O., Wolf, D., Peretz, A., Shemer-Avni, Y., Roif-Kaminsky, D., Kopelman, N., Huppert, A., Koelle, K., and Stern, A. (2020). Full genome sequences inform patterns of SARS-CoV-2 spread into and within Israel. MedRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.21.20104521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . (2020a). Corona: Historical data. (in Hebrew). Retrieved from https://govextra.gov.il/ministry-of-health/corona/corona-virus/

- Ministry of Health (2020b). Epidemiological Report: Highlights: The New COVID-19, 14.4.2020. Director of Public Health Services, (in Hebrew). Available on-line at: https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/covid-19_epi4.pdf

- Ministry of Health and National Emergency Authority . (2007). Planning and organization of essential market in an emergency: Standard operating procedures No. 22. Retrieved from https://www.themarker.com/embeds/pdf_upload/2020/20200410-085056.pdf

- National Center for Information and Knowledge for the Fight against the Corona . (2020a). Daily report. State of Affairs: Israel. 5.4.2020, (in Hebrew). Retrieved from https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/daily-report-05042020/he/daily-report_daily-report-05042020.pdf

- National Center for Information and Knowledge for the Fight against the Corona . (2020b). Daily report. State of Affairs: Israel. 6.4.2020 (in Hebrew). Retrieved from https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/report-n20-jerusalem-covid19-status/he/research-report_report-n20-Jerusalem-covid19-status.pdf

- Office of the State Comptroller and Ombudsman of Israel . (2020). Annual Report 70A, March 23. Retrieved from https://www.mevaker.gov.il/sites/DigitalLibrary/Pages/Reports/3246-6.aspx

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) . (2016). Health policy overview: Health policy in Israel, April. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Health-Policy-in-Israel-April-2016.pdf

- Weible, C. M., Nohrstedt, D., Cairney, P., Carter, D. P., Crow, D. A., Durnová, A. P., … Stone, D. (2020). COVID-19 and the policy sciences: Initial reactions and perspectives. Policy Sciences, 53(2), 225–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]