ABSTRACT

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are among the most common comorbidities associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality risk. Renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockers are cornerstones in the treatment of both hypertension and proteinuric CKD. In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a hypothesis emerged suggesting that the use of RAS blockers may increase susceptibility for COVID-19 infection and disease severity in these populations. This hypothesis was based on the fact that angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a counter regulatory component of the RAS, acts as the receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 cell entry. Extrapolations from preliminary animal studies led to speculation that upregulation of ACE2 by RAS blockers may increase the risk of COVID-19-related adverse outcomes. However, these hypotheses were not supported by emerging evidence from observational and randomized clinical trials in humans, suggesting no such association. Herein we describe the physiological role of ACE2 as part of the RAS, discuss its central role in COVID-19 infection and present original and updated evidence from human studies on the association between RAS blockade and COVID-19 infection or related outcomes, with a particular focus on hypertension and CKD.

Keywords: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, chronic kidney disease, COVID-19, hypertension, renin–angiotensin system

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2); it began in China at the end of 2019 and developed into a global pandemic in 2020 [1]. Since then, COVID-19 has been established as a major issue of public health, infecting >200 million individuals and accounting for >4.5 million deaths worldwide, with numbers continuously rising [2]. The risk of severe COVID-19 disease and associated death increases with older age, male sex and the coexistence of various comorbid conditions, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and, above all, chronic kidney disease (CKD) [3].

Initial reports from China, Italy and the USA suggested that hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity among hospitalized COVID-19 patients [4, 5] as well as among severely ill COVID-19 individuals admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) [6]. As a consequence, early in the pandemic, a large number of observational studies associated COVID-19-related deaths with prevalent hypertension [4, 5, 7]. However, the role of hypertension as a risk factor for the adverse effects of COVID-19 probably needs to be better defined, as there are a number of factors that could confound a possible relationship between hypertension and severe COVID-19, including age and common comorbidities, i.e. cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and CKD [8]. The high prevalence of hypertension overall, and particularly in the elderly, could explain a large part of the association between hypertension and COVID-19 severity, as older patients seem to be at a higher risk for COVID-19-related complications [9]. In a seminal cross-sectional study designed to delineate some of these issues, Iaccarino et al. [3] showed that age and comorbidities, such as coronary heart disease, heart failure, CKD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were the most important determinants of death among COVID-19 patients, while hypertension and antihypertensive therapy per se were not associated with adverse outcomes in these individuals. As such, the association of the presence of hypertension with COVID-19 severity and associated death needs further examination.

CKD was not listed in initial reports as a risk factor for severe COVID-19; however, within a few months, underlying CKD evolved as one of the most common comorbidities conveying an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-associated mortality [10, 11]. A study from the USA including 5279 COVID-19 patients showed that underlying CKD was associated with hospital admission and disease severity [12]. In another study from the UK, which included data from 17 million electronic health records, CKD was also identified as a risk factor for COVID-19-related mortality [13]. Furthermore, the results from the European Renal Association (ERA) Registry [14] including 4298 patients receiving kidney replacement therapy showed that both dialysis patients (n = 3285) and kidney transplant recipients (KTRs; n = 1013) had a significantly higher 28-day mortality risk than propensity score-matched historical controls. Interestingly, the mortality risk in both end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) groups was higher in patients >75 years of age, while the presence of several comorbidities also affected outcomes, similar to observations in non-CKD populations [3].

With the onset of the pandemic, some authors suggested that patients with hypertension or cardiovascular disease who were on renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockers might be at higher risk of severe COVID-19 [15], based on previous evidence that SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 bind to their target cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) located in the cell membrane [16]. As RAS blockers are cornerstones in the treatment of several conditions, including hypertension, heart failure and proteinuric CKD, non-evidence-based, widespread and uncontrolled discontinuation of these drugs would have enormous consequences for cardiovascular and kidney health worldwide [17–19]. A huge number of publications related to this topic appeared and continue to be published. Thus the present work is an update on the role of ACE2 within RAS physiology, the crucial role of ACE2 in COVID-19 infection and the evidence from observational and human studies on the association of RAS blockade and COVID-19 infection and associated complications in patients with hypertension and CKD.

ROLE OF ACE2 IN THE RAS

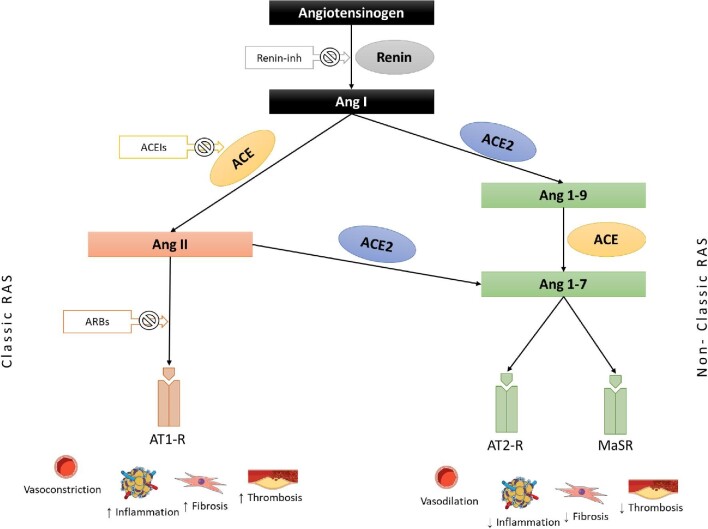

The RAS is the most important endocrine system, participating in the regulation of numerous physiological systems. Among others, it plays a key role in the control of blood pressure (BP) by regulating vascular tone and fluid and electrolyte balance [20]. The main components of the RAS involved in BP regulation are angiotensin II (Ang II) and angiotensin 1-7 (Ang 1-7) [21]. Ang II is a potent vasoconstricting agent that increases renal sodium and water reabsorption through direct action in the proximal tubules and indirectly through an increase of aldosterone secretion in the distal tubules [22]. In addition to these actions, Ang II also has significant oxidative, inflammatory and fibrotic actions that are involved in cardiorenal remodelling [22]. The above main effects of Ang II take place through binding to the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) and subsequent activation of several signal transduction pathways [22]. On the other hand, the Ang 1-7/ACE2 cascade, known as the non-classic RAS, acts as an endogenous counter regulatory arm to the Ang II/ACE axis. Ang 1-7 activates the Mas receptor (MasR) to promote vasodilation and exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic functions [21]. Components of both RAS pathways are co-expressed in the majority of human tissues, having paracrine and autocrine functions independent of their systemic effects; the balance between these axes determines whether tissue injury will occur in response to different stimuli [21].

ACE is a metalloprotease converting the decapeptide Ang I into octapeptide Ang II, the main mediator of the classic RAS [23]. ACE2 is the pivotal enzyme of the non-classic RAS; it is a transmembranic monocarboxypeptidase with 806 amino acids, which shares ∼40% structural identity and 60% sequence similarity with ACE [24]. ACE2 is highly expressed in the heart (endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts), blood vessels (endothelial and smooth muscle cells), lungs (bronchial epithelial cells, type 2 pneumocytes and macrophages), kidney (tubular epithelial cells) and the gut (intestinal epithelial cells) and plays an important role in several cardiovascular and immune pathways [21]. Among multiple functions, the most significant role of ACE2 is the conversion of Ang I to Ang 1-9 and Ang II to Ang 1-7, promoting systemic vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory effects [21] (Figure 1). Due to structural differences in the binding sites of ACE and ACE2, the pharmacological class of ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) does not inhibit the activity of ACE2 [25].

FIGURE 1:

The role of ACE and ACE2 in classic and non-classic RAS pathways.

ROLE OF RAS BLOCKERS IN COVID-19: PRELIMINARY HYPOTHESES

The potential association between COVID-19 and RAS was hypothesized early in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. ACE2 acts as the cell membrane receptor for some strains of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, mediating the entrance of the virus into the cells by binding the spike protein [26]. Binding of the N-terminal portion of the viral protein unit S1 to a pocket of the ACE2, along with S protein cleavage between the S1 and S2 units by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), facilitates virus entry into cells, viral RNA release and replication and cell-to-cell transmission [27].

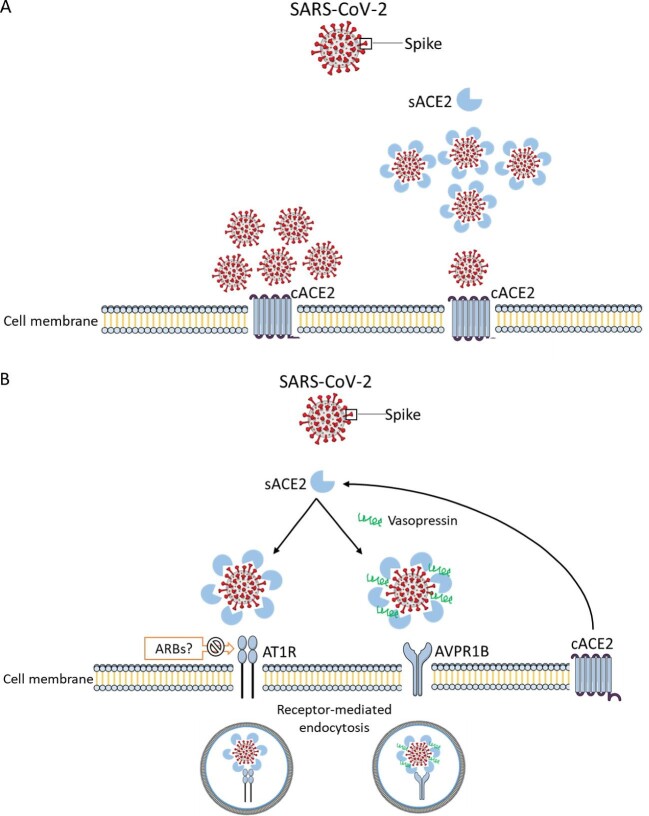

Previous data from animal studies have shown that RAS blockers might upregulate tissue activity or ACE2 expression in the heart, lung and kidneys [28–32]. However, it was also proposed that soluble ACE2 may behave as a decoy receptor for SARS-CoV-2, limiting viral binding to cell membrane ACE2 (Figure 2). Indeed, the combination of soluble ACE2 and remdesivir markedly improved their therapeutic windows against SARS-CoV-2 in in vitro and animal models [33, 34]. To this end, clinical trials of soluble ACE2 for COVID-19 are ongoing (e.g. NCT05065645), although initial phase 2 trials did not meet the primary endpoint (NCT04335136). In this regard, most, if not all, clinical studies addressing the impact of RAS blockade on ACE2 studied soluble ACE2 (which may limit SARS-CoV-2 infection) rather than cell membrane ACE2 (that may potentially favor SARS-CoV-2 infection). They described multiple determinants of soluble ACE2, including both therapeutic agents and underlying conditions. Thus, in some studies, RAS blockade was associated with lower soluble ACE2 [35] while in others there was no association [36, 37]. A final glimpse of the complexity of the system and the need for results of actual clinical trials rather than relying on predictions from preclinical models came for the realization that SARS-CoV-2 forms aggregates, through the spike protein, with soluble ACE2 or soluble ACE2–vasopressin to enter cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis using AT1R or arginine vasopressin receptor 1B (AVPR1B), respectively [38]. Entry using AT1R would presumably be blocked by angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2:

The potential roles of soluble ACE2 (sACE2) in COVID-19 infection. (A) sACE2 may behave as a decoy receptor for SARS-CoV-2, limiting viral binding to cell membrane ACE2 (cACE2). (B) SARS-CoV-2 forms aggregates, through the spike protein, with sACE2 or sACE2-vasopressin to enter cells via AT1R or AVPR1B.

In any case, given that increased cell membrane ACE2 in response to RAS blockade, as observed in animals, could theoretically increase the chance of virus entry into organs through an increase of the potential entry sites [39], there was initially much concern about the role of RAS blockers on ACE2 expression and hence susceptibility to COVID-19 infection [40]. On the other hand, some authors have also proposed that ACEIs and ARBs could have a beneficial effect in COVID-19 [41]. More specifically, it has been suggested that either by diminishing production of Ang II with the use of an ACEI or by blocking the Ang II–AT1R binding with the use of an ARB, there could be an enhanced generation of Ang 1-7 by ACE2 and activation of the MasR, which could attenuate lung inflammation and fibrosis [42]. Finally, Cohen et al. [42] previously proposed a third hypothesis, i.e. that ACEIs could be harmful and ARBs are neutral in COVID-19 severity, as ACEIs block bradykinin breakdown, thus increased bradykinin and its active metabolite DABK binds to the B2/B1 receptor, respectively, leading to increased lung inflammation [43]. On the other hand, ARBs do not take part in the bradykinin cascade and thus they do not precipitate further bradykinin-mediated lung injury [42]. Moreover, as indicated above, they may block virus entry via AT1R [38].

ROLE OF RAS BLOCKERS IN COVID-19: OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

In contrast to the above hypotheses, observational studies published in mid-2020 demonstrated that the use of RAS blockers is not associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and disease severity, including mortality [44, 45]. In a population-based case–control study in Italy, the use of RAS blockers was more common among COVID-19 patients than among controls, but was not associated with COVID-19 infection or disease severity [44]. Similar observations were also made in another cohort study including 12 594 patients from the USA; there was no association between the use of five different classes of antihypertensive treatment (ACEIs, ARBs, beta blockers, calcium-channel blockers or thiazide diuretics) and an increased likelihood of a positive test for COVID-19 or an increased risk for severe COVID-19 [45]. In addition, in a multicentre cohort study including >1.3 million patients with hypertension from the USA and Spain showed that there was no association between COVID-19 diagnosis and exposure to ACEI/ARB therapy versus calcium-channel blockers/thiazide therapy {hazard ratio [HR] 0.98 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84–1.14]}, as well as no significant difference between RAS blockers and calcium-channel blockers/thiazides for risk of COVID-19 hospitalization, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury or sepsis across all comparisons [46]. Finally, in a meta-analysis from Baral et al. [47] including 52 studies with a total of 101 949 COVID-19 patients, treatment with ACEIs or ARBs was not associated with a higher risk of multivariable-adjusted mortality and severe adverse events.

Of note, there are also some studies indicating a protective effect of RAS blockers in COVID-19-related outcomes. For example, in a large cohort of 1.4 million patients with different diseases (hypertension, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, CKD) in Sweden, the use of RAS blockers was associated with a significantly lower risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization and death [48]. A similar association was observed when ARB use was analysed separately, whereas ACEI use was not significantly associated with any outcome [48]. The aforementioned meta-analysis from Baral et al. [47] also showed that among patients with hypertension there were significant reductions in the risk of death [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.57 (95% CI 0.43–0.76)] and severe adverse events [aOR 0.68 (95% CI 0.53–0.88)] in patients receiving ACEIs or ARBs. Similarly, a recent properly designed meta-analysis of 30 observational studies with 17 281 patients accounting for confounders during data synthesis showed that treatment with RAS blockers was associated with significantly decreased mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 after adjusting for age, sex, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes and CKD [49].

Despite the fact that RAS blockers are among the most frequently described medications in patients with CKD, data about the effects of RAS blockers in COVID-19 severity, particularly in this population, are scarce. The ERA COVID-19 database (ERACODA) is a European multicentre database aiming to investigate the course and outcome of COVID-19 in patients on dialysis and KTRs [50]. In a recent subanalysis of ERACODA including 1052 dialysis patients and 459 KTRs, Soler et al. [51] demonstrated that there was no association between treatment with RAS blockers and 28-day mortality in both crude and adjusted models [haemodialysis patients: adjusted HR (aHR) 1.04 (95% CI 0.73–1.47); KTRs: aHR 1.12 (95% CI 0.69–1.83)]. Similarly, discontinuation of RAS blockers during COVID-19 disease was not associated with mortality in both dialysis patients and KTRs [haemodialysis patients: aHR 1.52 (95% CI 0.51–4.56); KTRs: aHR 1.36 (95% CI 0.40–4.58)]. Finally, no significant associations between treatment with RAS blockers and COVID-19 severity outcomes (i.e. hospitalization, ICU admission, ventilator support) were observed [51]. Similar results were obtained across both subgroups when ACEIs and ARBs were studied separately [51].

ROLE OF RAS BLOCKERS IN COVID-19: CLINICAL TRIALS

Despite the importance of the studies described above, these works inevitably carry some limitations inherent to their observational design, including selection bias, collider and time-dependent bias and confounding [42], therefore these findings should be considered as hypothesis-generating, requiring confirmation by randomized controlled trials (RCTs). As of this writing, only a few RCTs investigating the association of RAS blocker use and the course and prognosis of COVID-19 disease have been published (Table 1). In the Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Adverse Outcomes in Patients with COVID19 trial (BRACE-CORONA; NCT04364893), 659 hospitalized COVID-19 patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio either to continuation or discontinuation of ACEI/ARB therapy for 1 month. Among baseline characteristics, 40.4% of participants were females, the median age was 55.1 years, 31.9% had diabetes and 4.6% had coronary heart disease; however, the study excluded patients with decompensated heart failure 1 year prior to enrollment. RAS blocker discontinuation was not associated with beneficial effects for the primary outcome [mean between-group difference in days alive and out of hospital: −1.10 (95% CI −2.30–0.13)], suggesting that withdrawal of RAS blockers in hospitalized COVID-19 patients does not alter the short-term prognosis of the disease [52]. A study characteristic that might limit the generalizability of these findings is the reasonable exclusion of patients with contraindications to discontinue therapy with RAS blockers (i.e. patients with heart failure). Consistent with the above, the results from the Randomized Elimination or ProLongation of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in COVID-19 (REPLACE COVID) trial including 152 hypertensive patients (45.0% females, mean age 62 ± 12 years, 52.0% diabetes, 12% coronary heart disease) hospitalized for COVID-19 infection also suggested that there were no significant differences between RAS blocker continuation versus discontinuation in the incidence of the combined primary endpoint (time to death, duration of mechanical ventilation, time on renal replacement or vasopressor therapy and multiorgan dysfunction during hospitalization) [53]. Limitations of the study included the exclusion of patients with contraindications to discontinue RAS blockers (e.g. heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, nephrotic range proteinuria, etc.), as well as an imbalance in the use of ACEIs across the assigned groups at baseline (49% in the discontinuation versus 33% in the continuation group; P = 0.05).

Table 1.

Studies investigating the effects of discontinuation of RAS blockers during COVID-19 infection on disease severity and outcomes

| Study | Location | Study design | Participants | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRACE-CORONA trial [52] | Brazil | Multicentre, registry-based, open-label, parallel-group randomized clinical trial with blinded endpoint assessment | n = 659 hospitalized patients [median age 55.1 years (IQR 46.1–65.0)] | Number of days alive and out of the hospital through 30 days | Death (during the 30-day follow-up period), CV death, COVID-19 progression | Primary outcome: no difference (discontinuation: 21.9 ± 8.0 versus continuation group: 22.9 ± 7.1 days) Secondary outcomes: no differences in death, CV death, COVID-19 progression |

| REPLACE COVID trial [53] | USA, Canada, Mexico, Sweden, Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina | Prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial | n = 152 hospitalized patients (age 62 ± 12 years) | A global rank score (time to death, duration of MV, time on renal replacement or vasopressor therapy and multi-organ dysfunction during the hospitalization) | All-cause death, length in-hospital stay, length of ICU stay, invasive MV or ECMO, AUC of the SOFA score | Primary outcome: no differences [discontinuation: median rank 81 (IQR 38–117) versus continuation: 73 (40–110); β-coefficient 8 (95% CI 13–29)]Secondary outcomes: no differences between the two arms in all outcomes studied. |

| ACEI-COVID trial [54] | Austria and Germany | Parallel group, randomized, controlled, open-label trial | n = 204 hospitalized patients [median age 75 years (IQR 66–80)] | Maximum SOFA score within 30 days, where death was scored with the maximum achievable SOFA score | Area under the death-adjusted SOFA score (AUCSOFA), mean SOFA score, ICU admission, MV and death | Primary outcome: no difference [discontinuation: median SOFA score 0 (0–2) versus continuation: 1 (0–3); P = 0.12] |

| Secondary outcomes: ↓ AUCSOFA, ↓ mean SOFA score, ↓ death and organ dysfunction at 30 days in discontinuation group. No significant differences for MV and ICU admission | ||||||

| Najmeddin et al. [55] | Iran | Prospective, parallel-group, triple-blind, randomized trial | n = 64 hospitalized patients (age 66.3 ± 9.9 years) | Length of stay in hospitals and ICU | Need for MV, non-invasive ventilation, readmission, and COVID-19 symptoms after discharge | Primary outcome: no difference [hospitalization length: discontinuation 4.0 (IQR 2.0–5.0) versus continuation 4.0 days (2.0–8.0); P = 1.000, ICU stay length: 4.0 days (IQR 2.0–5.0) versus 7.0 (3.5–11.2); P = 0.691] |

| Secondary outcomes: no differences between the two arms in all outcomes studied |

AUC, area under the curve; CV, cardiovascular; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR, interquartile range; MV, mechanical ventilation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

More recently, the results of the Stopping ACE-inhibitors in Covid-19 trial (ACEI-COVID; NCT04353596) have been published. This was a randomized, controlled, multicentre, open-label trial that randomly assigned 204 COVID-19 patients on chronic treatment with an ACEI/ARB to continuation or discontinuation of RAS blockers for 30 days [54]. Participants of the ACEI-COVID trial were older (mean age 72 ± 11 years) than the two aforementioned trials, 33% had diabetes and 22% had coronary heart disease. Patients with severe heart failure (ejection fraction <30%, New York Heart Association class 3–4) were again excluded. The primary endpoint was the maximal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score within 30 days and was not significantly different between the two arms [54]. Among the secondary endpoints, the area under the SOFA score and mean SOFA score were significantly lower in the discontinuation than in the continuation group, suggesting that the discontinuation of RAS blockers in COVID-19 may lead to a faster and better recovery [54]. Nonetheless, these observations should be considered again as hypothesis-generating, as the primary result of the study was considered to be neutral. Finally, another recently published prospective, blinded, randomized clinical trial in Iran in 64 patients with hypertension (53.1% females, mean age 66.3 ± 9.9 years) showed that the primary outcome (i.e. hospitalization/ICU length of stay) was not different between patients with the continuation of RAS blockers or patients in which RAS blockers were substituted with a calcium channel blocker [55]. It should be noted that the conclusions of the later trial, as well as other trials of relevant size, may be limited by inadequate study power, whereas the findings of the larger studies in the field (i.e. the BRACE-CORONA trial) are more solid. Overall, the aforementioned trials showed that treatment with RAS blockers does not seem to affect outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. These findings are aligned with the existing observational data and support the general recommendations produced by several national and international scientific organizations and societies to continue the use of antihypertensive medications in general and ACEIs/ARBs in particular in patients with COVID-19 infections [56, 57].

The above trials provide important evidence on the effects of discontinuation of RAS blockade in COVID-19-infected patients. However, they did not assess all the relevant questions in the field, i.e. whether treatment with RAS blockers increases the propensity of infection with SARS-CoV-2 infection or whether the above neutral results are also present in specific patient groups, such as individuals with ESKD. Another important question is whether initiation of an RAS blocker during COVID-19 infection may have beneficial effects on disease severity and outcomes. As of this writing, there are two studies that tried to address this issue (Table 2). In a parallel-group, randomized, superiority trial including 158 hospitalized COVID-19 patients (46.8% females, mean age 65.3 ± 17.1 years, 19.0% diabetes) who were not on ACEI or ARB treatment at baseline, Duarte et al. [58] showed a significant reduction in inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein levels by adding telmisartan on existing standard-of-care treatment compared with standard-of-care treatment alone [58]. In contrast, a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of adding losartan on ACEI/ARB-naïve outpatients with COVID-19 (n = 117 patients, 49.5% females, median age 38 years, 5.9% diabetes) was terminated early because of the low likelihood of treatment effect [59]. The currently ongoing Ramipril for the Treatment of COVID-19 trial (RAMIC; NCT04366050) is investigating the potential benefits of ramipril over placebo in improving survival, reducing ICU admissions and the use of mechanical ventilation support in 560 patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19. Similarly, two other trials are investigating the effects of losartan (NCT04312009) and spironolactone (NCT04345887) in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Hopefully these ongoing clinical trials, as well as the future meta-analyses of randomized trials, will elucidate the optimal use of RAS blockers in patients with COVID-19.

Table 2.

Published and ongoing studies investigating the effects of initiation of a RAS blocker during COVID-19 infection on disease severity and outcomes

| Study | Location | Study design | Participants | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duarte et al. [58] (NCT04355936) | Argentina | Randomized, open label, parallel group, controlled superiority trial (intervention: p.os 80 mg telmisartan twice daily for 10 days on top of standard care) | n = 158 hospitalized COVID-19 patients | CRP plasma levels at day 5 and 8 after randomization | Time to discharge within 15 days, admission to ICU and death at 15 and 30 days | Primary outcome: ↓ Day 5 and Day 8 CRP levels in telmisartan group (P = 0.038/<0.001, respectively) |

| Secondary outcomes: ↓ median time-to-discharge, ↓ death rate by day 30, ↓ composite outcome of ICU, mechanical ventilation or death at days 15 and 30 in telmisartan group | ||||||

| Puskarich et al. [59] (NCT04311177) | USA | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo controlled trial (intervention: oral 25 mg losartan twice daily for 10 days) | n = 117 COVID-19 outpatients | All-cause hospitalization within 15 days | Functional status, dyspnoea, temperature and viral load | The trial was terminated early due to reduced hospitalization rate and reduced likelihood of clinically important treatment effect. No significant difference between losartan and placebo for the primary outcome (5.2% versus 1.7%, P = 0.32), adverse events and viral loads |

| RAMIC study (NCT04366050) | USA | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo controlled trial (intervention: oral 2.5 mg ramipril once daily for 14 days) | n = 560 COVID-19 patients hospitalized or in emergency department | Composite outcome of mortality or need for ICU admission or ventilator use within 14 days | - | - |

| NCT04312009 | USA | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo controlled trial (intervention: oral 25 mg losartan twice daily for 7 days) | n = 205 hospitalized COVID-19 patients | Difference in Estimated (PEEP-adjusted) PaO2:FiO2 ratio at 7 days | Hypotension, AKI, SOFA score, SpO2:FiO2 ratio, all-cause mortality, ICU admission/length of stay, length of hospitalization, respiratory failure and viral load | - |

| NCT04345887 | Turkey | Parallel group, placebo controlled trial (intervention: oral 200 mg Spironolactone once daily for 5 days) | n = 60 COVID-19 patients admitted in ICU | Difference in PaO2/FiO2 ratio at 5 days | Difference in SOFA score at 5 days | - |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CRP, C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

CONCLUSION

RAS blockade represents a cornerstone in the treatment of patients with hypertension, cardiovascular disease and CKD. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of ACEIs and ARBs in COVID-19-infected patients was questioned due to the fact that cell membrane ACE2 is the main entry point of SARS-CoV-2 into cells and background studies have shown that it is upregulated during ACEIs/ARBs treatment. Observational studies suggested that there is no higher risk from continuing ACEIs/ARBs in COVID-19 patients already receiving these medications, while their use may also confer a benefit through organ protection. Subsequent randomized trials have demonstrated that RAS blockers are safe, as their discontinuation does not appear to alter outcomes. As a result, several scientific societies have recommended against discontinuation of RAS blockers in patients with or at risk of COVID-19 infection. Ongoing randomized trials are expected to offer detailed information on whether initiation of RAS blockers during COVID-19 infection may confer benefits. As of this writing, more observational studies and clinical trials are needed to specifically examine the safety of continuing RAS blockade during COVID-19 disease in CKD patients.

Contributor Information

Marieta P Theodorakopoulou, Department of Nephrology, Hippokration Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

Maria-Eleni Alexandrou, Department of Nephrology, Hippokration Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

Afroditi K Boutou, Department of Respiratory Medicine, G. Papanikolaou Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Charles J Ferro, Department of Renal Medicine, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK.

Alberto Ortiz, Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, IIS-Fundacion Jimenez Diaz UAM, Madrid, Spain.

Pantelis Sarafidis, Department of Nephrology, Hippokration Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A.O. has received consultancy or speaker fees or travel support from Advicciene, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Amicus, Amgen, Fresenius Medical Care, Bayer, Sanofi-Genzyme, Menarini, Kyowa Kirin, Alexion, Idorsia, Chiesi, Otsuka, Novo Nordisk and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma and is Director of the Catedra Mundipharma-UAM of diabetic kidney disease and the Catedra AstraZeneca-UAM of CKD and electrolytes. A.O. is the Editor-in-Chief of CKJ. P.S. reports consultant and speaker fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Elpen Pharmaceuticals, Genesis Pharma, Innovis Pharma, Menarini, Sanofi and Winmedica and research support from AstraZeneca; he is an Associate Editor of the Journal of Human Hypertension and a Theme Editor for Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation. The other authors disclose that they do not have any financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest regarding this article.

FUNDING

This article was not supported by any source and represents an original effort of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boutou AK, Georgopoulou A, Pitsiou Get al. Changes in the respiratory function of COVID-19 survivors during follow-up: a novel respiratory disorder on the rise? Int J Clin Pract 2021; 75: e14301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. https://covid19.who.int/ (2 October 2021, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iaccarino G, Grassi G, Borghi Cet al. Age and multimorbidity predict death among COVID-19 patients: results of the SARS-RAS study of the Italian Society of Hypertension. Hypertension 2020; 76: 366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du Ret al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan Met al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020; 323: 2052–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella Aet al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020; 323: 1574–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu PP, Blet A, Smyth Det al. The science underlying COVID-19: implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation 2020; 142: 68–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kario K, Morisawa Y, Sukonthasarn Aet al. COVID-19 and hypertension-evidence and practical management: guidance from the HOPE Asia Network. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020; 22: 1109–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CAet al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020; 369: m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruchfeld A. The COVID-19 pandemic: consequences for nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021; 17: 81–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ERA-EDTA Council, ERACODA Working Group . Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for severe COVID-19: a call to action by the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021; 36: 87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang Jet al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020; 369: m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran Ket al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020; 584: 430–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NCet al. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1540–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wan Y, Shang J, Graham Ret al. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol 2020; 94: e00127–e00120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering Wet al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 2018; 36: 1953–2041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SDet al. Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1169–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Blood Pressure Work Group . KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2021; 99: S1–S87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loutradis C, Price A, Ferro CJet al. Renin–angiotensin system blockade in patients with chronic kidney disease: benefits, problems in everyday clinical use, and open questions for advanced renal dysfunction. J Hum Hypertens 2021; 35: 499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santos RAS, Sampaio WO, Alzamora ACet al. The ACE2/angiotensin-(1–7)/MAS axis of the renin–angiotensin system: focus on angiotensin-(1–7). Physiol Rev 2018; 98: 505–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Verma K, Pant M, Paliwal Set al. An insight on multicentric signaling of angiotensin II in cardiovascular system: a recent update. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 734917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sparks MA, Crowley SD, Gurley SBet al. Classical renin–angiotensin system in kidney physiology. Compr Physiol 2014; 4: 1201–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ballermann BJ, Onuigbo MAC. Angiotensins. In: Fray JCS (ed). Comprehensive Physiology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011: 104–155 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arendse LB, Danser AHJ, Poglitsch Met al. Novel therapeutic approaches targeting the renin–angiotensin system and associated peptides in hypertension and heart failure. Pharmacol Rev 2019; 71: 539–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Yet al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 586–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder Set al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181: 271–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MCet al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 2005; 111: 2605–2610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Gallagher PEet al. Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade on renal angiotensin-(1–7) forming enzymes and receptors. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 2189–2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Agata J, Ura N, Yoshida Het al. Olmesartan is an angiotensin II receptor blocker with an inhibitory effect on angiotensin-converting enzyme. Hypertens Res 2006; 29: 865–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soler MJ, Ye M, Wysocki Jet al. Localization of ACE2 in the renal vasculature: amplification by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade using telmisartan. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2009; 296: F398–F405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wösten-van Asperen RM, Lutter R, Specht PAet al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome leads to reduced ratio of ACE/ACE2 activities and is prevented by angiotensin-(1-7) or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist. J Pathol 2011; 225: 618–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Monteil V, Dyczynski M, Lauschke VMet al. Human soluble ACE2 improves the effect of remdesivir in SARS-CoV-2 infection. EMBO Mol Med 2021; 13: e13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shoemaker RH, Panettieri RA, Libutti SKet al. Development of a novel, pan-variant aerosol intervention for COVID-19. bioRxiv 2021; doi: 10.1101/2021.09.14.459961 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raedle-Hurst T, Wissing S, Mackenstein Net al. Determinants of soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 concentrations in adult patients with complex congenital heart disease. Clin Res Cardiol 2020; doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01782-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Michaud V, Deodhar M, Arwood Met al. ACE2 as a therapeutic target for COVID-19; its role in infectious processes and regulation by modulators of the RAAS system. J Clin Med 2020; 9: E2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chirinos JA, Cohen JB, Zhao Let al. Clinical and proteomic correlates of plasma ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) in human heart failure. Hypertension 2020; 76: 1526–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yeung ML, Teng JLL, Jia Let al. Soluble ACE2-mediated cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 via interaction with proteins related to the renin–angiotensin system. Cell 2021; 184: 2212–2228.e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shibata S, Arima H, Asayama Ket al. Hypertension and related diseases in the era of COVID-19: a report from the Japanese Society of Hypertension Task Force on COVID-19. Hypertens Res 2020; 43: 1028–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. South AM, Tomlinson L, Edmonston Det al. Controversies of renin–angiotensin system inhibition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020; 16: 305–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao Set al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med 2005; 11: 875–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cohen JB, South AM, Shaltout HAet al. Renin–angiotensin system blockade in the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Kidney J 2021; 14: i48–i59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roche JA, Roche R. A hypothesized role for dysregulated bradykinin signaling in COVID-19 respiratory complications. FASEB J 2020; 34: 7265–7269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani Met al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2431–2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin Cet al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2441–2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morales DR, Conover MM, You SCet al. Renin–angiotensin system blockers and susceptibility to COVID-19: an international, open science, cohort analysis. Lancet Digit Health 2021; 3: e98–e114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baral R, Tsampasian V, Debski Met al. Association between renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e213594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Savarese G, Benson L, Sundström Jet al. Association between renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitor use and COVID-19 hospitalization and death: a 1.4 million patient nationwide registry analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2021; 23: 476–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee T, Cau A, Cheng MPet al. Angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in COVID-19: meta-analysis/meta-regression adjusted for confounding factors. CJC Open 2021; 3: 965–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Noordzij M, Duivenvoorden R, Pena MJet al. ERACODA: the European database collecting clinical information of patients on kidney replacement therapy with COVID-19. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 2023–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Soler MJ, Noordzij M, Abramowicz Det al. Renin–angiotensin system blockers and the risk of COVID-19-related mortality in patients with kidney failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 16: 1061–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lopes RD, Macedo AVS, de Barros E Silva PGMet al. Effect of discontinuing vs continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers on days alive and out of the hospital in patients admitted with COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 254–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cohen JB, Hanff TC, William Pet al. Continuation versus discontinuation of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bauer A, Schreinlechner M, Sappler Net al. Discontinuation versus continuation of renin–angiotensin-system inhibitors in COVID-19 (ACEI-COVID): a prospective, parallel group, randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 863–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Najmeddin F, Solhjoo M, Ashraf Het al. (15 July 2021). Effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibitors on early outcomes of hypertensive COVID-19 patients: a randomized triple-blind clinical trial. Am J Hypertens 2021; doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpab111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Position Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE-inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang (7 November 2021, date last accessed)

- 57. International Society of Hypertension . A Statement from the International Society of Hypertension on COVID-19. https://ish-world.com/a-statement-from-the-international-society-of-hypertension-on-covid-19/ (7 November 2021, date last accessed)

- 58. Duarte M, Pelorosso F, Nicolosi LNet al. Telmisartan for treatment of Covid-19 patients: an open multicenter randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 37: 100962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Puskarich MA, Cummins NW, Ingraham NEet al. A multi-center phase II randomized clinical trial of losartan on symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 37: 100957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]