ABSTRACT

Background

US individuals, particularly from low-income subpopulations, have very poor diet quality. Policies encouraging shifts from consuming unhealthy food towards healthy food consumption are needed.

Objectives

We simulate the differential impacts of a national sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax and combinations of SSB taxes with fruit and vegetable (FV) subsidies targeted to low-income households on SSB and FV purchases of lower and higher SSB purchasers.

Methods

We considered a 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax and 2 FV subsidy rates of 30% and 50% and used longitudinal grocery purchase data for 79,044 urban/semiurban US households from 2010–2014 Nielsen Homescan data. We used demand elasticities for lower and higher SSB purchasers, estimated via longitudinal quantile regression, to simulate policies’ differential effects.

Results

Higher-SSB-purchasing households made larger reductions (per adult equivalent) in SSB purchases than lower SSB purchasers due to the tax (e.g., 4.4 oz/day at SSB purchase percentile 90 compared with 0.5 oz/day at percentile 25; P < 0.05). Our analyses by household income indicated low-income households would make larger reductions than higher-income households at all SSB purchase levels. Targeted FV subsidies induced similar, but nutritionally insignificant, increases in FV purchases of low-income households, regardless of their SSB purchase levels. Subsidies, however, were effective in mitigating the tax burdens. All low-income households experienced a net financial gain when the tax was combined with a 50% FV subsidy, but net gains were smaller among higher SSB purchasers. Further, low-income households with children gained smaller net financial benefits than households without children and incurred net financial losses under a 30% subsidy rate.

Conclusions

SSB taxes can effectively reduce SSB consumption. FV subsidies would increase FV purchases, but nutritionally meaningful increases are limited due to low purchase levels before policy implementation. Expanding taxes beyond SSBs, providing larger FV subsidies, or offering subsidies beyond FVs, particularly for low-income households with children, may be more effective.

Keywords: SSB tax, fruit and vegetable subsidies, combined policy, heterogeneity, quantile regression, longitudinal data, price elasticity

Introduction

Individuals in the United States, particularly those from low-income subpopulations, have very poor diet quality with excessive intake of foods high in added sugar, added sodium, and unhealthy saturated fats (1–5). Regarding high added sugar intake, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) remain among the largest contributors, despite recent declines in their consumption (6, 7). Global experience (8–15) and US studies (16–28) indicate SSB taxes can help reduce SSB purchases and generate meaningful revenues.

Yet, there is a need to further improve dietary quality through encouraging shifts towards whole and minimally processed foods, such as fruits and vegetables (FVs), whole grains, and proteins low in saturated fats. Recently, there has been a growing array of healthy food incentive pilots, primarily funded through the Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives (FINI) Program, targeting low-income US subpopulations. To date, these pilots have been focused on FV incentives. An evaluation of the 2015–2017 FINI program found that FV incentives increased monthly household FV purchases among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants by up to 16% (29), indicating that such targeted incentives can help narrow the nutrition gap among the poor (30).

Meanwhile, simulation studies have shown that FV incentives for adults within Medicaid and Medicare can prevent 1.93 million cardiovascular disease events and save $39.7 billion in formal health-care costs over the average lifetime of the target population (18.3 years) (31). Other studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of FV subsidies combined with SSB disincentives (restrictions or taxes) within SNAP, and found that such combined policies can produce larger health gains and health-care savings compared to either a food incentive or a food disincentive policy alone (32–34).

This study builds off the existing policies and programs by exploring the implications of a national SSB tax policy and a targeted FV subsidy both separately and in combination. Specifically, using nationally representative longitudinal grocery purchase data for urban/semiurban US households, we first predict the impacts of a national SSB tax on household SSB purchases, overall and by income level for low- and higher-income households. Importantly, because the adverse health effects of SSB consumption increase with consumption levels, we allow for the tax effect to vary by household SSB purchase level within each study population.

Next, we examine the impacts of targeted FV subsidies on FV purchases of low-income households, both separately and in combination with SSB taxes. As before, we allow for the impact of these policies to also vary by household SSB purchase level. Regarding the combined policy, we also examine whether higher SSB purchasers would gain larger FV subsidy transfers than lower SSB purchasers, such that the larger financial burden of the SSB tax falling on them would be mitigated. Finally, given the importance of healthy eating during childhood (35–38) and that a healthful diet rich in FVs can be cost-prohibitive for many low-income households (39–41), we analyze the differential effects of the aforementioned fiscal policies on low-income households with and without children.

Methods

Policy simulations

We first predicted the effects of a national 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax (absent FV subsidies) on SSB purchases of urban/semiurban US households, overall and by household income level. Next, we investigated the impact of targeted FV subsidies (absent a SSB tax) on FV purchases of low-income households at the 2 subsidy rates of 30% and 50%. The 30% rate was consistent with the Healthy Incentives Pilot program (42). The 50% rate was motivated by the availability of higher FV incentives up to 100% through FINI grants, renamed the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program in the 2018 Farm Bill (43). Thirdly, we explored the effects of a policy that combined the national SSB tax with targeted FV subsidies on SSB and FV purchases of low-income households. We also analyzed how FV subsidies could help mitigate the financial costs of the SSB tax falling on low-income households purchasing different amounts of SSBs.

In simulating the impacts of fiscal policies involving FV subsidies, we focused our attention on low-income households rather than on all households. Subsidizing FVs at the national level would be controversial and challenging, and raises difficult policy questions regarding how such policies could be feasibly implemented and whether the resources would be well spent. However, existing evidence (e.g., Healthy Incentives Pilot) indicates that FV subsidies could be plausibly and broadly provided to all low-income households through channels such as SNAP.

As mentioned before, throughout, we recognized that responsiveness to each policy might vary based on how much SSBs households are purchasing, with meaningful improvements among higher SSB purchasers being a key target. Lastly, all simulations assumed a complete (100%) pass-through of taxes and subsidies to retail prices and that all consumers were aware of changes in prices of targeted food categories.

Data

We used data from the 2010–2014 Nielsen Homescan Panel (Homescan), a national consumer panel that tracks households’ packaged food purchases for at-home consumption by asking them to scan Universal Product Codes (UPCs) of all purchased products at home after each shopping trip (44, 45). Homescan households were recruited from 52 Nielsen markets (roughly corresponding to the largest metropolitan statistical areas in the contiguous United States) and 24 remaining areas for a total of 76 areas. Nielsen selected recruited households to meet demographic targets to ensure national representativeness, subject to additional weights (projection factors).

After scanning a product's UPC, households recorded the purchased quantity (volume), dollars paid (expenditures), and the purchase date and transmitted this information electronically to Nielsen weekly. Each year, Nielsen prepared a “static” panel, retaining households that consistently reported purchases for at least 10 months of the year. It then matched the static panel with an additional database, including detailed product characteristics such as brand type and product module codes but not nutritional information. To obtain this information, we merged the static panel to the Nutrition Facts Panel and ingredient data from various sources (by UPC and year), including the Mintel Global New Product Database (46).

The static panel also included self-reported sociodemographic information, such as household income and composition. We classified households as low-income if their income was no more than 185% of the federal poverty line (FPL) and as higher-income otherwise. The 185% FPL is a policy-relevant threshold typically used by states to determine income eligibility for food assistance programs such as SNAP and the Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children, and has been used by other studies (7, 28). We further divided low-income households into those with and without any children up to 18 years of age. Moreover, because rural areas were underrepresented in Homescan, following previous studies (28, 47, 48), we restricted the sample to Nielsen's 52 large markets (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, to the extent that households residing in rural areas may have different shopping behavior from urban/semiurban households (49), our findings may not be generalized to rural households.

Homescan has other limitations which should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, Homescan reports household-level food purchases and not individual-level food intake. Second, foods purchased and consumed away from home (e.g., restaurants, fast foods, and vending machines) are not reported in the Homescan. Third, purchases of non-UPC random-weight products (e.g., fresh FVs, meat, cheese, baked goods) are not captured in the Homescan. We discuss the implications of these limitations in the Discussion section.

Statistical methods

To simulate the impacts of the fiscal policies considered herein, we estimated price elasticities of demands (i.e., the ratio of the percentage change in purchase quantity to the percentage change in price of a particular food category) for the SSB, fruit, and vegetable categories. A detailed description of demand estimation methods is provided in the Supplemental Material. Briefly, we defined an aggregate SSB category to contain all product modules typically included in existing excise SSB taxes: regular (caloric) carbonated soft drinks, noncarbonated soft drinks, sports and energy drinks, fruit drinks, and premade sweetened coffees and teas. The fruit category included all UPC-labeled, uniform-weight fresh, frozen, canned, and dried fruits; similarly, the vegetable category contained all UPC-labeled, uniform-weight fresh, frozen, canned, and dried vegetables.

For each household and each food category, we aggregated weekly purchase quantities, standardized in ounces (1 oz = 28.35 grams) and fluid ounces (1 fluid oz = 29.57 grams), and expenditures into quarterly totals. Household-level purchase quantities were then translated into adult equivalents (AEs). To aid interpretation of the results, we converted household total quarterly purchases into daily averages (oz/day/AE).

We then used a semi-logarithmic demand specification to estimate demand elasticities for each category of interest, separately. The dependent variable was the household purchase quantity of a food category, measured in AEs. The explanatory variables included: Fisher price indices (normalized by the Fisher price index of a numéraire category) for 16 aggregate packaged food-at-home (FAH) categories in logarithmic form (see Supplemental Material); a quadratic term in the logarithm of the normalized household total packaged FAH expenditure; the logarithm of household head's age; dummy variables for the household head's education level, marital status, and (self-identified) race/ethnicity; and 9 variables for the proportion of household members within each of the 10 gender-specific age groups (0–11, 12–18, 19–34, 35–64, and 65+, with the female 0–11 age group set as the omitted category) to account for household composition; as well as dummy variables for year, quarter, and census regions.

Next, we employed a longitudinal censored quantile regression estimator (50, 51) to estimate demand parameters at quantiles (hereafter termed percentile levels) 25, 50, 75, and 90 of each category's purchase distribution for all households, and separately for each income group. We then used estimated demand parameters to estimate price elasticities, for which we calculated SEs using the delta method (52). The estimated price elasticities, along with a short write-up of the results, are presented in Supplemental Figures 2 and 3. In the last step, we utilized estimated price elasticities for SSBs to simulate the effect of the national SSB tax on lower to higher SSB purchasers. In this context, lower SSB purchasers were defined by lower SSB purchase percentiles (e.g., 25th percentile) and higher SSB purchasers by higher percentiles (e.g., 90th percentile).

Regarding the targeted FV subsides, we were interested in the effects on FV purchases of lower and higher SSB purchasers within the low-income subpopulation, rather than the impacts on lower and higher FV purchasers. As shown below, low-income households at different SSB purchase levels buy similar amounts of FVs, falling within the third quartiles of FV purchase distributions. Therefore, to predict the impacts of subsidies on FV purchases of low-income households buying varying amounts of SSBs, we used price elasticity estimates at the 75th percentile of FV purchase distributions. Quantitatively similar results were obtained using the median FV price elasticities. All statistical analyses were conducted in 2021 using Stata/MP (StataCorp LLC), version 15.1. SEs for demand parameter estimates were clustered at the household level and were robust to clustering at higher levels (e.g., county level). All statistical inferences were conducted at the 95% confidence level.

Results

Household characteristics

The final analysis sample included 884,532 observations from 79,044 urban/semiurban households. The average period a household was in the sample was 11 quarters, although 21% of the households were in the sample for 4 quarters and 15% for 20 quarters. Table 1 describes the sample. Importantly, households at the higher end of the SSB purchase distribution (measured in AEs) tend to have lower incomes. Consistently, low-income households, particularly those without children, are more likely to be ranked at higher SSB purchase percentiles. Lastly, packaged FAH spending increases with the SSB purchase level, whereas FV shares of expenditure reveal a declining pattern.

TABLE 1.

Household summary statistics

| SSB Purchase Percentile | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Income, thousands of dollars | 59.6 | (35.9) | 67.3 | 63.6 | 57.0 | 50.4 |

| Low-income households, % | 27.4 | (44.6) | 22.4 | 25.2 | 29.8 | 33.2 |

| Low-income households with children, % | 11.2 | (31.5) | 10.2 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 11.3 |

| Low-income households without children, % | 16.2 | (36.9) | 12.2 | 12.0 | 16.9 | 21.9 |

| Packaged FAH expenditures, $/quarter/AE | 298.5 | (191.4) | 237.4 | 264.6 | 322.1 | 375.8 |

| Household size, AEs | 2.6 | (1.4) | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.2 |

| Household head's characteristics, % | ||||||

| Age, y | 52.3 | (14.3) | 51.1 | 51.3 | 52.5 | 53.3 |

| Female | 80.2 | (39.9) | 82.5 | 84.6 | 80.4 | 75.3 |

| Married | 51.4 | (50.0) | 56.5 | 57.1 | 51.1 | 42.5 |

| High school or less | 57.3 | (49.5) | 51.5 | 56.6 | 61.3 | 64.0 |

| Some college | 20.0 | (40.0) | 19.4 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 18.5 |

| College degree or more | 22.7 | (41.9) | 29.1 | 23.5 | 18.8 | 17.5 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.4 | (46.5) | 68.8 | 66.6 | 68.5 | 67.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.8 | (33.4) | 9.8 | 13.2 | 14.1 | 16.3 |

| Hispanic | 12.7 | (33.3) | 13.7 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 11.5 |

| Other races | 6.1 | (24.0) | 7.7 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 5.1 |

| SSBs and FVs packaged FAH budget shares, % | ||||||

| SSBs | 6.4 | (6.1) | 2.8 | 5.6 | 8.3 | 11.2 |

| Fruits | 3.4 | (3.8) | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| Vegetables | 5.7 | (3.9) | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.1 |

| Households, n | 79,044 | |||||

| Observations,N | 884,532 | |||||

The first 2 columns report means and SDs, respectively, for subsamples of households making positive SSB purchases. Columns titled “25 to 90” report the means for households in percentiles 25 to 90, respectively, of household SSB purchase distribution in AEs. A low income corresponds to a household income no more than 185% of the federal poverty line. All calculations use Homescan's projection factor. Source: authors’ calculations, based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2010–2014 period across the US market. The Nielsen Company, 2015 (53). Abbreviations: AE, adult equivalent; FAH, food at home; FV, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

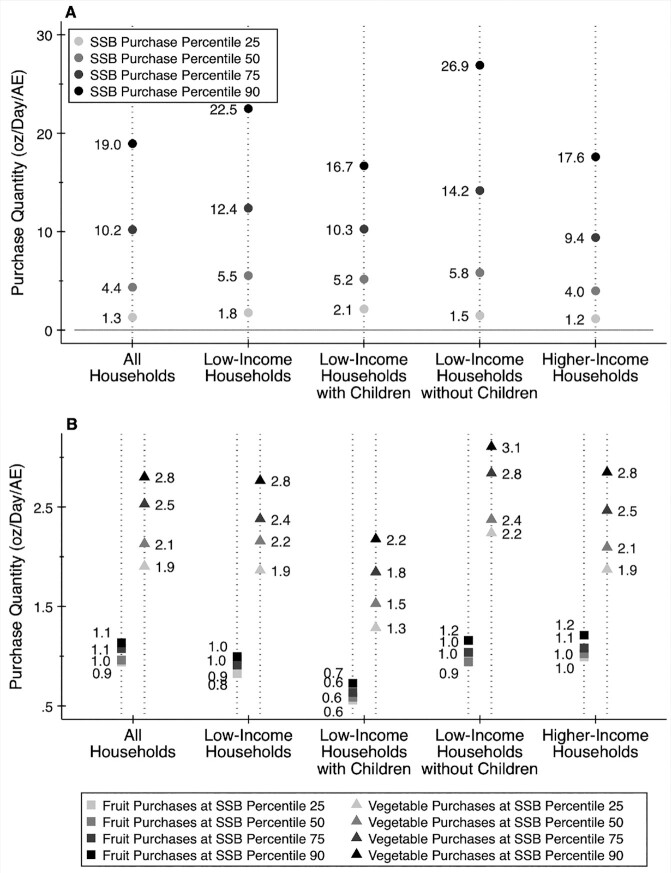

Baseline purchase quantities

There is a substantial variation in the prepolicy SSB purchase levels across the SSB purchase distribution in the full sample (Figure 1A). For instance, a higher SSB purchasing household at the 90th percentile buys more than 4 times SSBs as a household at the median (19 compared with 4.4 oz/day/AE, respectively). There is also variation across income groups and across low-income subgroups. Low-income households, particularly those without children, on average, purchase more SSBs than higher-income households on an AE basis. Figure 1B indicates a minimal variation in packaged FV purchases of different types of SSB-purchasing households across the SSB purchase distribution, in the ranges of 0.9 to 1.1 oz/day/AE for fruits and 1.9 to 2.8 oz/day/AE for vegetables, in the full sample. Stated differently, lower- and higher-SSB-purchasing households buy similar amounts of FVs, with no considerable variation across subpopulations.

FIGURE 1.

Baseline (A) SSB and (B) FV purchase quantities for different types of SSB-purchasing households, overall and by household income level. SSB-purchasing-household types were defined by percentiles of the SSB purchase distribution for each study population; higher SSB percentiles refer to higher SSB purchasers, and lower percentiles refer to lower SSB purchasers. Values on the vertical axis show household average daily purchase quantities, calculated from household total quarterly purchases, standardized in ounces per adult equivalent. A low income corresponds to household income no more than 185% of the federal poverty line. A higher income corresponds to a household income above 185% of the federal poverty line. All calculations use Homescan's projection factor. Numbers of observations (n): full sample (884,532), low-income households (166,382), low-income households with children (47,077), low-income households without children (119,305), and higher-income households (718,150). Source: authors’ calculations, based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2010–2014 periods across the US market. The Nielsen Company, 2015 (53). Abbreviations: AE, adult equivalent; FV, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

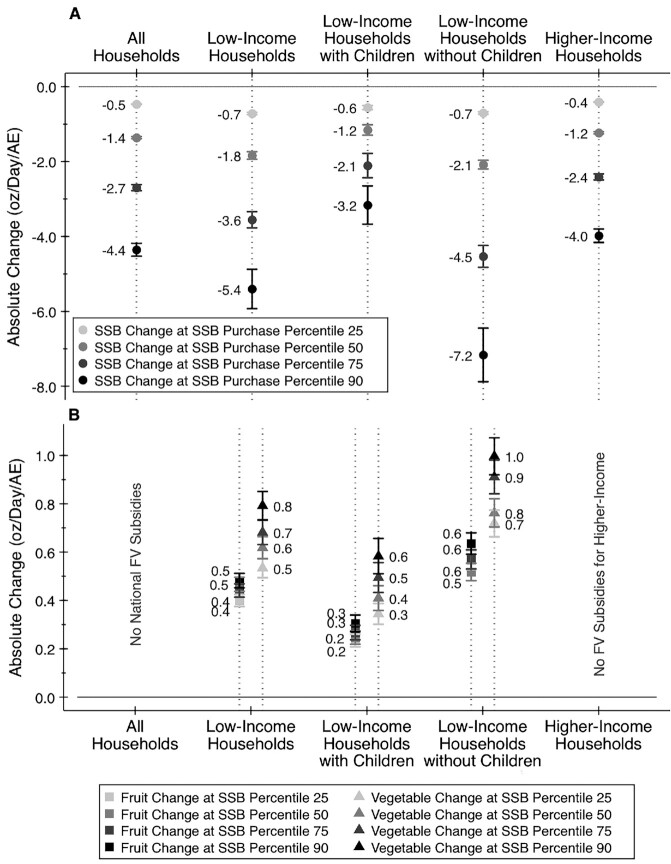

Policy simulation results: SSB tax only

Figure 2A presents the simulated absolute changes (oz/day/AE) in household SSB purchases in response to a national 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax (absent FV subsides). All changes are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (P < 0.05). In the full sample, higher SSB purchasers make substantially larger reductions in SSB purchases than lower SSB purchasers (e.g., 4.4 oz/day/AE at SSB purchase percentile 90 compared with 0.5 oz/day/AE at percentile 25; P < 0.05). Moreover, low-income households, at all SSB purchase levels, reduce their SSB purchases more than higher-income households on an AE basis (e.g., 5.4 compared with 4 oz/day/AE, respectively, at percentile 90; P < 0.05). Within the low-income subpopulation, households without children make larger reductions than those with children, with more noticeable differences at higher SSB purchase levels (e.g., 7.2 compared with 3.2 oz/day/AE, respectively, at percentile 90; P < 0.05). In summary, the results suggest that SSB taxes would affect higher-SSB-purchasing households more than lower SSB purchasers, and that these effects are mainly concentrated among low-income households without children.

FIGURE 2.

Simulated absolute changes in (A) SSB and (B) FV purchases of different types of SSB-purchasing households in response to a national 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax (absent FV subsidies) and a targeted 50% FV subsidy (absent a SSB tax), respectively. SSB-purchasing-household types were defined by percentiles of the SSB purchase distribution for each study population; higher SSB purchase percentiles refer to higher SSB purchasers, and lower percentiles refer to lower SSB purchasers. A low income corresponds to a household income no more than 185% of the federal poverty line. A higher income corresponds to a household income above 185% of the federal poverty line. Absolute changes were simulated using price elasticities from semi-logarithmic demand models for SSBs and FVs, estimated via a longitudinal censored quantile regression estimator. All estimated changes are accompanied by 95% CIs. All calculations used Homescan's projection factor. Numbers of observations (n): full sample (884,532), low-income household (166,382), low-income households with children (47,077), low-income households without children (119,305), and higher-income households (718,150). Source: authors’ calculations, based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2010–2014 periods across the US market. The Nielsen Company, 2015 (53). Abbreviations: AE, adult equivalent; FV, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Although higher-SSB-purchasing households are less sensitive to SSB price changes than lower purchasers (Supplemental Figure 2), they purchased considerably larger amounts of SSBs before the tax and at lower unit prices (Supplemental Figure 4A). Thus, in response to a uniform rate tax, they would make larger decreases in SSB purchases in absolute terms. The larger decreases among low-income households can be explained similarly. In addition, since low-income households without children are more price responsive (Supplemental Figure 2) and purchase more SSBs (on an AE basis), it is not surprising that we found they would decrease SSB purchases more than those households with children.

Supplemental Figure 5 A reports simulated percentage changes (%) in SSB purchases due to the SSB tax. Consistent with the observed patterns in price elasticity estimates across SSB purchase percentiles, percentage reductions in SSB purchases at higher percentiles are smaller than those at lower SSB percentiles. While this pattern implies that higher SSB purchasers would make less than proportional reductions in SSB purchases compared to lower purchasers (e.g., 23% at the 90th percentile compared with 36% at the 25th percentile; P < 0.05), we note that percentage changes at all purchase levels are nutritionally meaningful. Furthermore, as discussed above, the smaller percentage changes by higher SSB purchasers translate into larger absolute changes, which are important from a public health perspective.

Policy simulation results: FV subsidies only

Figure 2B shows the simulated impacts of a 50% FV subsidy (absent a SSB tax) on FV purchases of low-income households. Overall, households at all SSB purchase levels increase their FV purchases by similar amounts, in the ranges of 0.4 to 0.5 oz/day/AE for fruits and 0.5 to 0.8 oz/day/AE for vegetables. All changes are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (P < 0.05). While these absolute changes in FV purchases are small, they translate into meaningful percentage changes on the orders of 48% and 29% for fruits and vegetables, respectively (Supplemental Figure 5B). This suggests that the very low purchase level at baseline limits FV subsidies’ from inducing nutritionally significant increases in FV purchases. Comparing the results for low-income households with children compared to those without children indicates that the latter subgroup would make slightly larger increases in FV purchases in response to subsidies (e.g., 1 oz/day/AE compared with 0.6 oz/day/AE, respectively, at the 90th percentile of vegetable distribution; P < 0.05). We observed similar patterns due to 30% FV subsidies, with even smaller absolute increases in FV purchases.

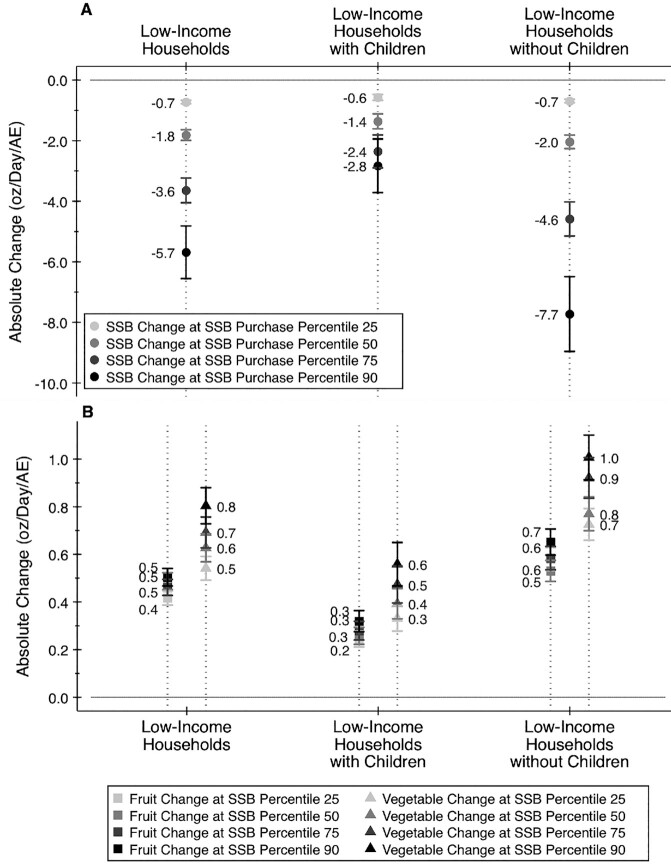

Policy simulation results: SSB tax combined with FV subsidies

The impacts of the SSB tax when combined with a 50% FV subsidy on SSB purchases of low-income households are very similar to those from a SSB tax alone (Figure 3A). This result is expected because indirect effects of FV subsidies on SSB purchases (due to demand interrelationships between SSBs and FVs, quantified by cross-price elasticities of demand) are nonexistent (Supplemental Figure 3). Analogously, the policy's effects on FV purchases are almost identical to those from an FV subsidy alone (Figure 3B). Thus, while the combined policy could result in higher dietary gains, the higher benefits would be driven by direct effects of the tax and subsidies and not their indirect impacts. Similar patterns were observed for the combined policy with a 30% FV subsidy (Supplemental Figure 6).

FIGURE 3.

Simulated absolute changes in (A) SSB and (B) FV purchases of different types of SSB-purchasing households in response to a national 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax combined with a 50% FV subsidy targeted at low-income households. SSB-purchasing-household types were defined by percentiles of the SSB purchase distribution for each study population; higher SSB purchase percentiles refer to higher SSB purchasers, and lower percentiles refer to lower SSB purchasers. A low income corresponds to a household income no more than 185% of the federal poverty line. Absolute changes were simulated using price elasticities from semi-logarithmic demand models for SSBs and FVs estimated via a longitudinal censored quantile regression estimator. All estimated changes are accompanied by 95% CIs. All calculations used Homescan's projection factor. Number of observations (n): full sample (884,532), low-income households (166,382), low-income households with children (47,077), low-income households without children (119,305), and higher-income households (718,150). Source: authors’ calculations, based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2010–2014 periods across the US market. The Nielsen Company, 2015 (53). Abbreviations: AE, adult equivalent; FV, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

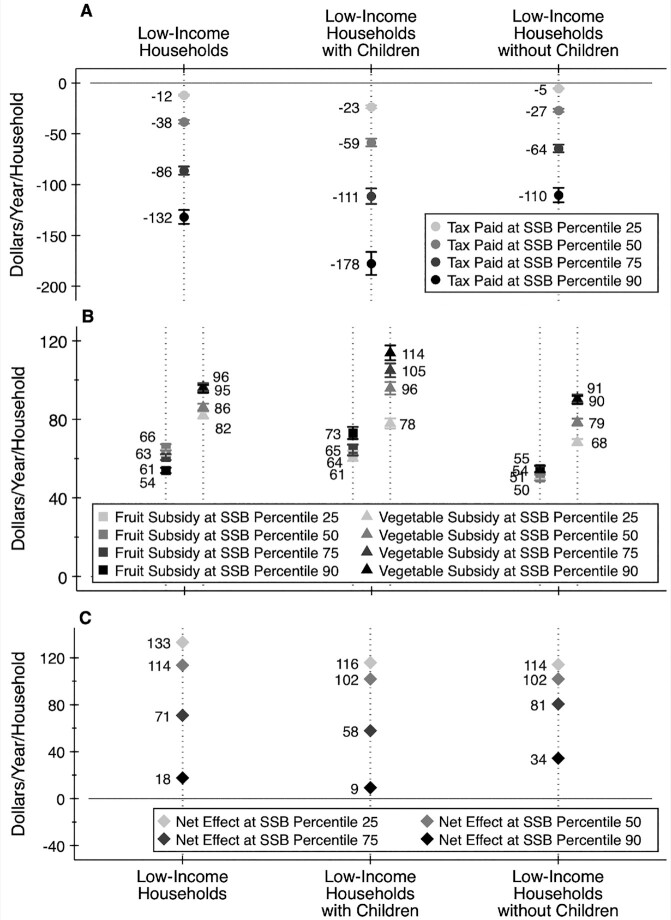

Policy simulation results: Financial impacts of the combined policy

Figure 4 presents the financial effects (dollars per year per household) of the combined policy, under a 50% FV subsidy rate, on low-income households. Starting with Figure 4A, we see higher SSB purchasers would pay substantially larger taxes (denoted by negative values) than lower SSB purchasers (e.g., $132 at SSB percentile 90 compared with $12 at SSB percentile 25; P < 0.05). Despite this substantial variation in taxes paid, in Figure 4B, we see that households at all SSB purchase levels would receive similar FV subsidies, ranging from $54 to $66 for fruit and $82 to $96 for vegetable subsidies. Consequently, higher-SSB-purchasing households would gain smaller net financial benefits than lower SSB purchasers (e.g., $18 at SSB percentile 90 compared with $133 at percentile 25; Figure 4C). Regardless, all households would experience a net financial gain. Moreover, households with children would pay higher SSB taxes (due to their higher total SSB purchases) than those without children (e.g., $178 compared with $110, respectively at SSB percentile 90) and receive larger but less than proportional total FV subsidies (e.g., $73 + $114 = $187 compared with $55 + $90 = $145, respectively, at SSB percentile 90). Consequently, at higher SSB purchase levels, households with children experience smaller net financial gains than households without children (e.g., $9 compared with $34, respectively, at SSB percentile 90) and incur net financial losses when the tax is combined with a 30% FV subsidy (Supplemental Figure 7).

FIGURE 4.

Simulated (A) SSB tax burdens, (B) FV subsidy transfers, and (C) net financial effects of a national 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax combined with a targeted 50% FV subsidy on different types of low-income SSB-purchasing households. SSB taxes paid by households are denoted by negative values. FV subsidies received are denoted by positive values. Net financial effects are calculated as the sum of total FV subsidies received and SSB taxes paid. Different types of SSB purchasing households are defined by percentiles of SSB purchase distribution for each study population; higher percentiles refer to higher SSB purchasers, and lower percentiles refer to lower SSB purchasers. Low income corresponds to household income no more than 185% of the federal poverty line. Simulated tax burdens and subsidy transfers are accompanied by 95% CIs. All calculations use Homescan's projection factor. Number of observations (n): low-income (166,382), low-income with children (47,077), low-income without children (119,305). Source: Authors’ calculations based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2010-2014 periods across the US market. The Nielsen Company, 2015 (53). Abbreviations: FV, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Discussion

Diet quality in the United States needs to be improved, particularly among the poor. This can be done by lowering unhealthy food intake and increasing healthy food intake. Efforts to improve diet quality are focused on reducing SSB consumption and increasing FV intake through taxes and subsidies, both of which we tested in a nationally representative sample of urban/semiurban households. One key finding is that SSB taxes would result in a much larger absolute decrease in SSB purchases of higher-SSB-consuming households at the higher end of the SSB purchase distribution. Consistently, we show that SSB taxes would induce larger absolute reductions in SSB purchases of low-income households, who tend to consume more SSBs than their higher-income counterparts (7). Further, within each income stratum, we found that the corrective effect of the tax increased with the SSB purchase level. These findings thus indicate that SSB taxes would result in much larger reductions in the absolute amount of SSB purchases among low-income, high-SSB consumers, in whom health implications are the most relevant.

One approach to enhance the effectiveness of SSB taxes in improving the dietary quality of the poor, while also mitigating the economic burden of the tax falling on them, is to combine taxes with FV subsidies. However, this approach is highly constrained, as levels of FV purchases are very low across the board and responsiveness to FV subsidies is relatively muted even among low-SSB-purchasing households. We find that although subsidizing FV consumption would increase FV purchases among low-income households, the subsidy rate must be large enough, given the very low initial consumption levels among this subpopulation. In particular, our findings imply that low-income households with children will need larger FV subsidies to have meaningful FV increases and to offset the financial implications of a 1-cent-per-ounce SSB tax fully. This will be a critical consideration for SNAP and/or Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children program administrators in considering any subsidy for program participants if the subsidy is targeted.

The coronavirus disease 2019 crisis has highlighted the urgent need to address the issue of very low diet quality, particularly among the poor US populations. Our findings strengthen empirical evidence suggesting that taxes are effective in discouraging purchases of unhealthy items like SSBs (8, 16, 17, 54). We also showed that SSB taxes would impact higher consumers much more, consistent with studies of the impacts of the national SSB and nonessential food taxes in Mexico (55, 56). An alternative but controversial option to reducing SSB intake of the poor includes restricting SSB purchases with SNAP benefits (57, 58). How impactful this will be is a major unknown now, as waiver applications to pilot such efforts have been rejected to date.

Another way to improve diet quality is to expand taxes beyond SSBs, given the growing evidence that with a broader tax, the health benefits and tax revenues would be much greater (59). Therefore, expanding taxes to cover ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which are high in added sugar, sodium, and saturated fats and contain many additives and other chemicals to enhance palatability and shelf life, may be needed. UPFs represent between half and two-thirds of the foods purchased and consumed by most Americans (4, 60–62). A randomized controlled trial demonstrated 2 weeks of being on a UPF diet can have a large impact on weight gain and selected noncommunicable disease (NCD) biomarkers (63). This, along with dozens of cohort studies, makes it clear that UPFs are linked with weight gain and major NCDs, such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as heart disease, cancer, and total mortality (64, 65).

Our findings also show that while FV subsidies/incentives can help improve FV purchases, it is still unclear whether they will improve overall dietary quality. Thus, it will be important to begin testing options beyond incentivizing FVs, to include other healthy alternatives such as nuts/seeds, whole grains, and healthy proteins such as legumes. Simulation studies have shown that a broader subsidy beyond FVs that also includes whole grains, nuts/seeds, seafood, and plant proteins could reduce cardiovascular disease events by 3.28 million and prevent 0.12 million diabetes cases, saving $100.2 billion in formal health-care costs, with a greater lifetime cost-effective ratio than an FV incentive only (32–34). More empirical and model-based research is needed to determine whether subsidizing a broader variety of healthy options can more effectively improve dietary quality.

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic only highlighted again the needs for additional targeted food and other social assistance for low-income households and the revenue sources to support them. Taxes on SSBs, and potentially other unhealthy foods, provide a redistributive option that could help address existing disparities/inequities. However, to help the poor and to address income regressivity concerns, the tax revenue must be linked with approaches for subsidizing a healthier diet for these households. Several US cities have directed their SSB tax revenues to support local public health and education programs, many of which have been allocated in equity-enhancing ways. In the wake of the pandemic, San Francisco and Seattle allocated some of their SSB tax revenues towards food vouchers for the poor, but the target population was limited, and the vouchers were not targeted towards healthy foods (66).

Strengths and limitations

This study examined the differential impacts of a national SSB tax combined with an FV subsidy targeted at low-income households. We investigated the impact on higher and lower SSB consumers across the SSB purchase distribution of low-income US households. This type of analysis is important for current and future food policy efforts, given that both the health consequences of SSB consumption and financial costs of SSB taxes are disproportionately larger for high consumers of SSBs. It also enabled us to examine the effectiveness of the policy in mitigating the financial burden of the tax imposed on low-income, high-SSB-purchasing households. Methodologically, using a longitudinal quantile regression estimator, we leveraged the longitudinal dimension of Homescan to avoid potential biases in demand elasticity estimates due to unobserved household behaviors, such as searching for lower prices within aggregate FAH categories.

The Homescan data used, however, have certain limitations which should be considered in interpreting our findings. First, they report household-level food purchases and not individual-level consumption. Purchases could differ from consumption for several reasons, such as throwing food away (i.e., food waste) or sharing it with others. Moreover, Homescan only provides data on foods purchased for at-home consumption, and thus food consumed away from home is not included in our analysis. Further, purchases of non-UPC-labeled, random-weight items are not recorded in Homescan. We know roughly one-third of calories from sugars are consumed away from home (e.g., at restaurants, fast foods, and vending machines) (67), and random-weight fresh FVs account for roughly 40% of the average Homescan household's total FV spending (28). Therefore, our simulation results provide lower-bound estimates of pricing policies’ dietary and economic effects.

Conclusions

Improving the diet quality of low-income US households is imperative. Imposing taxes on UPFs, like SSBs, can effectively reduce SSB consumption, with larger impacts on higher SSB consumers, who are more likely to have a lower income. Concurrently redistributing the generated tax revenues to provide FV subsidies to low-income households would help increase FV purchases; however, nutritionally meaningful increases may be limited due to very low purchase and consumption levels before policy implementation. Expanding the scope and size of taxes beyond SSBs would provide a much larger basis for expanding targeted subsidies to include other elements that are considered healthful and play a role in not only enhancing diet quality but in reducing the risks of a high-UPF diet on nutrition-related NCDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Donna Miles for exceptional assistance with data management. We also thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institutes of Health for financial support.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—PV: conducted the research, analyzed the data, drafted and revised the manuscript, and had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: were involved in designing the research and writing the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Funding for this work came primarily from Arnold Ventures. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (R01DK098072, DK056350, and CPC P2C HD050924) also provided financial support.

The funders had no role in the study design, implementation, analyses and interpretation of the data. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policies of their institutions and the funding agencies. The conclusions drawn from the Nielsen data used in this study are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Nielsen. Nielsen is not responsible for and had no role in, and was not involved in, analyzing, and preparing the results reported herein.

Supplemental Figures 1–7 and Supplemental Material are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: AE, adult equivalent; FAH, food at home; FINI, Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives; FV, fruit and vegetable; NCD, noncommunicable diseases; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages; UPC, universal product code; UPF, ultra-processed food.

Contributor Information

Pourya Valizadeh, Agricultural & Food Policy Center, Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA; Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA.

Barry M Popkin, Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Shu Wen Ng, Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript will not be made available because contractually, authors cannot share the Nielsen data or derivatives from it. Analytic code will be made available upon request.

References

- 1. Wilson MM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. American diet quality: where it is, where it is heading, and what it could be. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):302–10.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steele EM, Baraldi LG, da Costa Louzada ML, Moubarac J-C, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac J-C, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(1):5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith TA, Valizadeh P, Lin B-H, Coats E. What is driving increases in dietary quality in the United States?. Food Policy. 2019;86:101720. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(3):726–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valizadeh P, Popkin BM, Ng SW. Distributional changes in U.S. sugar-sweetened beverage purchases, 2002–2014. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(2):260–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colchero MA, Popkin BM, Rivera JA, Ng SW. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. BMJ. 2016;352:h6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colchero MA, Rivera-Dommarco J, Popkin BM, Ng SW. In Mexico, evidence of sustained consumer response two years after implementing a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Health Aff. 2017;36(3):564–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Essman M, Taillie LS, Frank T, Ng SW, Popkin BM., Swart EC. Taxed and untaxed beverage consumption by young adults in Langa, South Africa before and one year after a national sugar-sweetened beverage tax. PLoS Med. 2021;18(5):e1003574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stacey N, Edoka I, Hofman K, Popkin BM, Ng SW. Changes in beverage purchases following the announcement and implementation of South Africa's Health Promotion Levy: an observational study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(4):e200–e208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pell D, Mytton O, Penney TL, Briggs A, Cummins S, Penn-Jones C, Rayner M, Rutter H, Scarborough P, Sharp SJ et al. Changes in soft drinks purchased by British households associated with the UK soft drinks industry levy: controlled interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2021;372:n254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13. Krieger J, Bleich SN, Scarmo S, Ng SW. Sugar-sweetened beverage reduction policies: progress and promise. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42(1):439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scarborough P, Adhikari V, Harrington RA, Elhussein A, Briggs A, Rayner M, Adams J, Cummins S, Penney T, White M. Impact of the announcement and implementation of the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy on sugar content, price, product size and number of available soft drinks in the UK, 2015–19: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(2):e1003025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Popkin BM, Barquera S, Corvalan C, Hofman KJ, Monteiro C, Ng SW, Swart EC, Taillie LS. Towards unified and impactful policies to reduce ultra-processed food consumption and promote healthier eating. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(7):462–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roberto CA, Lawman HG, LeVasseur MT, Mitra N, Peterhans A, Herring B, Bleich SN. Association of a beverage tax on sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages with changes in beverage prices and sales at chain retailers in a large urban setting. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lawman HG, Bleich SN, Yan J, Hua SV, Lowery CM, Peterhans A, LeVasseur MT, Mitra N, Gibson LA, Roberto CA. One-year changes in sugar-sweetened beverage consumers’ purchases following implementation of a beverage tax: a longitudinal quasi-experiment. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(3):644–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cawley J, Frisvold D, Jones D. The impact of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes on purchases: evidence from four city-level taxes in the United States. Health Econ. 2020;29(10):1289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cawley J, Frisvold D, Hill A, Jones D. The impact of the Philadelphia beverage tax on purchases and consumption by adults and children. J Health Econ. 2019;67:102225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Powell LM, Leider J. The impact of Seattle's sweetened beverage tax on beverage prices and volume sold. Econ Human Biol. 2020;37:100856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones-Smith JC, Walkinshaw LP, Oddo VM, Knox M, Neuhouser ML, Hurvitz PM, Saelens BE, Chan N. Impact of a sweetened beverage tax on beverage prices in Seattle, WA. Econ Human Biol. 2020;39:100917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falbe J, Lee MM, Kaplan S, Rojas NA, Hinojosa AMO, Madsen KA. Higher sugar-sweetened beverage retail prices after excise taxes in Oakland and San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):1017–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cawley J, Frisvold D, Hill A, Jones D. Oakland's sugar-sweetened beverage tax: impacts on prices, purchases and consumption by adults and children. Econ Human Biol. 2020;37:100865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silver LD, Ng SW, Ryan-Ibarra S, Taillie LS, Induni M, Miles DR, Poti JM, Popkin BM. Changes in prices, sales, consumer spending, and beverage consumption one year after a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Berkeley, California, US: a before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Falbe J, Thompson HR, Becker CM, Rojas N, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Impact of the Berkeley excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1865–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee MM, Falbe J, Schillinger D, Basu S, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption 3 years after the Berkeley, California, sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):637–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Léger PT, Powell LM. The impact of the Oakland SSB tax on prices and volume sold: a study of intended and unintended consequences. Health Econ. 2021;30:1745–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valizadeh P, Ng SW. Would a national sugar-sweetened beverage tax in the United States be well targeted?. Am J Agric Econ. 2021;103(3):961–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vericker T, Dixit-Joshi S, Taylor J, Giesen L, Gearing M, Baier K, Lee H, Trundle K, Manglitz C, May L. The evaluation of Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives (FINI) interim report. Prepared by Westat, Inc. for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Project Officer: Eric Sean Williams; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parks CA, Stern KL, Fricke HE, Clausen W, Yaroch AL. Healthy food incentive programs: findings from food insecurity nutrition incentive programs across the United States. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(3):421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee Y, Mozaffarian D, Sy S, Huang Y, Liu J, Wilde PE, Abrahams-Gessel S, Jardim TdSV, Gaziano TA, Micha R. Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives for improving diet and health through Medicare and Medicaid: a microsimulation study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(3):e1002761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mozaffarian D, Liu J, Sy S, Huang Y, Rehm C, Lee Y, Wilde P, Abrahams-Gessel S, de Souza Veiga Jardim T, Gaziano T et al. Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives and disincentives for improving food purchases and health through the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): a microsimulation study. PLoS Med. 2018;15(10):e1002661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pearson-Stuttard J, Bandosz P, Rehm CD, Penalvo J, Whitsel L, Gaziano T, Conrad Z, Wilde P, Micha R, Lloyd-Williams F et al. Reducing US cardiovascular disease burden and disparities through national and targeted dietary policies: a modelling study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(6):e1002311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. French SA, Rydell SA, Mitchell NR, Oakes JM, Elbel B, Harnack L. Financial incentives and purchase restrictions in a food benefit program affect the types of foods and beverages purchased: results from a randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glewwe P, King EM. The impact of early childhood nutritional status on cognitive development: does the timing of malnutrition matter?. World Bank Econ Rev. 2001;15(1):81–113. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marshall S, Burrows T, Collins CE. Systematic review of diet quality indices and their associations with health-related outcomes in children and adolescents. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27(6):577–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Beecher MD, Roemmich JN. Increasing healthy eating vs. reducing high energy-dense foods to treat pediatric obesity. Obesity. 2008;16(2):318–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daniel C. Economic constraints on taste formation and the true cost of healthy eating. Soc Sci Med. 2016;148:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drewnowski A, Darmon N. Food choices and diet costs: An economic analysis. J Nutr. 2005;135(4):900–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rao M, Afshin A, Singh G, Mozaffarian D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e004277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Olsho LE, Klerman JA, Wilde PE, Bartlett S. Financial incentives increase fruit and vegetable intake among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants: a randomized controlled trial of the USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. John S, Lyerly R, Wilde P, Cohen ED, Lawson E, Nunn A. The case for a national SNAP fruit and vegetable incentive program. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(1):27–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Einav L, Leibtag E, Nevo A. Recording discrepancies in Nielsen Homescan data: are they present and do they matter?. QME. 2010;8(2):207–39. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Einav L, Leibtag ES, Nevo A. On the accuracy of Nielsen Homescan data. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2008. Report Number 69. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mintel. Global new product database. [Internet]. [Cited 2019 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.mintel.com/global-new-products-database.

- 47. Harding M, Lovenheim M. The effect of prices on nutrition: comparing the impact of product-and nutrient-specific taxes. J Health Econ. 2017;53:53–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhen C, Finkelstein EA, Nonnemaker JM, Karns SA, Todd JE. Predicting the effects of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes on food and beverage demand in a large demand system. Am J Agric Econ. 2014;96(1):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lacko A, Ng SW, Popkin B. Urban vs. rural socioeconomic differences in the nutritional quality of household packaged food purchases by store type. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bache SHM, Dahl CM, Kristensen JT. Headlights on tobacco road to low birthweight outcomes. Empir Econ. 2013;44(3):1593–633. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chernozhukov V, Hong H. Three-step censored quantile regression and extramarital affairs. J Am Statist Assoc. 2002;97(459):872–82. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bellemare MF, Wichman CJ. Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxf Bull Econ Stat. 2020;82(1):50–61. [Google Scholar]

- 53. The Nielsen Company. 2015 [Internet]. Available from: www.nielsen.com/us/en.html. [Accessed 2021 Oct 19]. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Batis C, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Taillie LS. First-year evaluation of Mexico's tax on nonessential energy-dense foods: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(7):e1002057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ng SW, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Colchero MA. Did high sugar-sweetened beverage purchasers respond differently to the excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Mexico?. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(4):750–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Taillie LS, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Batis C. Do high vs. low purchasers respond differently to a nonessential energy-dense food tax? Two-year evaluation of Mexico's 8% nonessential food tax. Prev Med. 2017;105:S37–S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Brookings Institute. Pros and cons of restricting SNAP purchases. 2017. [Accessed 2021 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/pros-and-cons-of-restricting-snap-purchases/.

- 58. Schanzenbach DW. Exploring options to improve the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2019;686(1):204–28. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Colchero A, Paraje G, Popkin BM. The impacts on food purchases and tax revenues of a tax based on Chile's nutrient profiling model. 2020 (under review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60. Martínez Steele E, Baraldi LG, Louzada MLdC, Moubarac J-C, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Steele EM, Popkin BM, Swinburn B, Monteiro CA. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dunford EK, Popkin BM, Ng SW. Recent trends in junk food intake in US children and adolescents, 2003–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:(1):49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hall KD. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: a one-month inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pagliai G, Dinu M, Madarena MP, Bonaccio M, Iacoviello L, Sofi F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2021;125(3):308–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lawrence MA, Baker PI. Ultra-processed food and adverse health outcomes. BMJ. 2019;365:l2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Krieger J, Magee K, Hennings T, Schoof J, Madsen KA. How sugar-sweetened beverage tax revenues are being used in the United States. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. USDA ARS. Energy intakes: percentages of energy from protein, carbohydrate, fat, and alcohol, by gender and age. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2017–2018. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2020. [Accessed 2021 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/1718/Table_5_EIN_GEN_17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript will not be made available because contractually, authors cannot share the Nielsen data or derivatives from it. Analytic code will be made available upon request.