Abstract

Objective

To learn from primary health care experts’ experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic across countries.

Methods

We applied qualitative thematic analysis to open-text responses from a multinational rapid response survey of primary health care experts assessing response to the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Respondents’ comments focused on three main areas of primary health care response directly influenced by the pandemic: 1) impact on the primary care workforce, including task-shifting responsibilities outside clinician specialty and changes in scope of work, financial strains on practices, and the daily uncertainties and stress of a constantly evolving situation; 2) impact on patient care delivery, both essential care for COVID-19 cases and the non-essential care that was neglected or postponed; 3) and the shift to using new technologies.

Conclusions

Primary health care experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe were similar in their levels of workforce stress, rapid technologic adaptation, and need to pivot delivery strategies, often at the expense of routine care.

Keywords: Primary health care, COVID-19, Pandemic, Patient care, Workforce, Qualitative research

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has impacted the entire world on a global, national, and local level (Dong et al., 2020). Millions of primary care workers worldwide have faced significant challenges in attempts to contain and treat the virus. National pandemic plans, quarantining and testing protocols, the closing of borders and lockdown procedures, and strategies to flatten the curve or boost herd immunity have all been implemented in various ways. The pandemic has shown the gaps in primary health care (PHC) worldwide, and the climb it will take to fulfill the public health goals of the Declaration of Astana (Declaration of Astana: Global Conference on Primary Health Care, 2018) and the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 (United Nations Foundation (2021) Sustainable Development Goals).

It is globally accepted that PHC is the most effective and sustainable health approach to address community health problems, implement solutions, and work towards health equity (Starfield et al., 2005). However, PHC, which comprises both public health and first-contact primary care, was underutilized and underinvested in most countries during the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which focused largely on hospital-based responses and resources; underscoring the underfunding and underutilization of PHC (Rasanathan & Evans, 2020). Past studies on pandemics/epidemics of individual experiences have documented miscommunications of national and local leadership, unsure responsibilities of public health duties in procuring both authority and community support, lack of personal protective equipment, as well as emotional and mental stressors, in addition to physical risks (Kunin et al., 2013; (Goodyear-Smith et al., 2021). This shows the need for a well-funded, comprehensive PHC strategy and infrastructure to curtail and combat future pandemics/epidemics (Prado et al., 2020).

While there are numerous qualitative studies focused on individual responses to COVID-19 in specific countries or regions (Al Ghafri et al., 2020; Gomez et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2020; Verhoeven et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020), there is less information on exploring primary care experts’ experiences during the pandemic on a multiple country scale spanning the globe (Rawaf et al., 2020). In this paper we aim to present the challenges of patient care and the impact on primary care associated with the uncertainty of rapidly adapting to changing governmental and public health policies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic that were experienced by primary care experts multinationally.

2. Methods

This paper is an analysis of one question's open-ended text responses that was part of a larger survey compiling primary care experts' perceptions of how their countries adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study question, “Since the first identified case of COVID-19 in your country, have the roles of a typical primary care team in your country changed?” and the accompanying text box asked respondents to elaborate on their answer if they wanted. We chose this question because we wanted to examine respondents' perspectives and experiences for similarities in primary care responses across countries. The larger survey employed a convenience sampling of primary care experts, including clinicians, academics, and policy-makers, and encouraged them to use snowballing to recruit more participants. The online, anonymous survey consisted of 34 questions to gauge national pandemic preparedness and adaptive response from a primary care perspective. The survey was available in English and Spanish and open from April 15 – May 4, 2020. Ethical approval was granted for three years on 9 April 2020 by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC); Ref number 024557.

There were 1131 survey responses recorded of which 1035 (91.5%) were useable, with 96 (8.5%) excluded due to incompleteness. These respondents represented 111 countries from all socio-economic levels and political systems. Complete demographic and methodological details from the survey have been published elsewhere, but included an examination of cumulative death rates by respondent country compared to primary care strength, an analysis of political, economic, and medical decision making that guided pandemic plans, and summary reports on demographics comparing key survey questions examining the intersection of primary care and public health (Goodyear-Smith et al., 2020).

The qualitative open-text responses were compiled in Excel for analysis. Thematic analysis was conducted by three members of the research team, led by an experienced qualitative methodologist. An a priori codebook was established based on the survey questions and overall research questions of the project. The research team coded the first 40 responses to check alignment with a priori codes and to identify emerging themes. Once consensus was reached on the initial 40 codes, the remaining responses were divided evenly between the researchers. Throughout the analysis process, the team employed an iterative constant comparative approach to identify, discuss, and refine additional emerging codes as they arose through regularly scheduled project analysis meetings. This allowed for continuous reflection on identifying themes, the ability to reach consensus, and provided inter-reader reliability. Quotes presented in this paper are original and only minorly altered to correct for obvious spelling or typographical errors. Spanish language quotes were initially run through Google Translate then checked by the lead qualitative researcher who is proficient in the language. Analysis was conducted after all quotes were translated into English.

3. Results

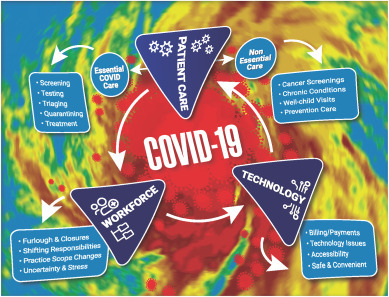

There were 339 unique responses recorded for the open-text portion of the question. Of these, 190 (56%) were female, 3 (1%) were gender diverse, and 144 (43%) were male, representing 69 countries, across all socio-economic levels and political systems. Thematic analysis revealed three overarching themes which respondents were coping with and adjusting to, during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic: 1) primary care workforce issues, including staff furloughs and closures of or restrictions on practice operations, shifting responsibilities of primary care workers, including their scope of practice, and large amounts of uncertainty, stress, and anxiety in confronting the unknown; 2) patient care concerns about COVID-19 and for routine and chronic conditions; and 3) the rapid adoption or expansion of telehealth, patient portals, and mobile phone apps in order to limit physical contact. These three themes also revealed subthemes, and due to the nature of qualitative data, some quotes overlap multiple themes and subthemes (see Fig. 1 for thematic model).

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 “storm” model showing connectedness of themes and subthemes (in color).

3.1. Impact on the primary care workforce

During the early stages of the pandemic, respondents experienced a variety of primary care workforce changes. These were broad sweeping and rapid, resulting in primary care clinicians having to adapt and innovate solutions quickly to meet COVID-19 pandemic response plans while supporting routine care. When lock-down requirements and quarantine measures were established, many primary care clinicians lost their jobs, were furloughed, or had their hours dramatically reduced due to sudden reductions in patient visits for usual care. One respondent commented,

“As a locum I have for the first time in my working life been scrambling around looking for work, after normally being fully booked ahead 1 1/2 years in advance. I am now surplus to requirements. I finally found work at a COVID testing centre,” (New Zealand, female primary care clinician (PCC)).

Another primary care clinician replied, “Doctors are being reassigned to intensive care and hospital teams. Other doctors are being laid off/furloughed because the scope of their primary care practice is ambulatory only,” (United States, female PCC).

Furloughs and lay-offs produced primary care workforce reductions, but many respondents also reported a shift in their daily responsibilities, location of work, or patient population focus. These shifts included governments incentivizing medical students to volunteer for pandemic specific protocols (Brazil, see Table 1 ), the utilization of more community health workers (South Africa), sending primary care clinicians outside the clinic and into the communities to provide COVID-19 testing to migrant workers (Singapore), the incorporation of military and naval officers to help with screenings (Fiji), or reassigning clinicians to surveillance teams (Trinidad and Tobago), and organizing clinician shifts to two-week periods to accommodate quarantine policies (Chile). Many respondents reported that their daily clinic activities had shifted to meet pandemic needs:

“The primary health care team is now required to do contact tracing, surveillance, establishing quarantine sites, providing manpower for screening at ports of entry, training health care workers on covid-19, donning and doffing, taking specimens from suspected patients and from people in quarantine sites,” (Botswana, male academic).

Table 1.

Illustrative quotes by impact on the primary care workforce subthemes.

| Workforce Subthemes: | Illustrative Quote | Country & Respondent Info |

|---|---|---|

| Furlough & Closures | “Most of the care is provided by private practitioners. There has been a shortage of support staff and paramedics within primary care teams due to lockdown/travel restrictions as well as the stigma associated with COVID 19.” | India, male primary care provider PCC |

| Shifting Responsibilities | “The government has launched a calling for voluntary services for health professionals and health students and a protocol offering benefits for last year Medicine students to stimulate their participation in fighting COVID.” | Brazil, female primary health care PHC academic |

| “More involvement of community health workers.” | South Africa, female PCC | |

| “They are deployed to screen people for covid-19 e.g migrant workers living in dormitories.” | Singapore, female PHC academic | |

| “We divide the team into 2 groups, and we work 2 weeks and 2 weeks quarantine, so there is continuous care from Monday to Saturday.” | Chile, female PCC | |

| “Some of the primary care physicians have been re-assigned to the Surveillance teams.” | Trinidad and Tobago, female PHC academic | |

| Practice Scope Changes | “… Less actual patient care. Less capacity to deliver mental health and opportunistic health screening.” | Australia, female PCC |

| “… The GP and his team represent now the only accessible health representative, leading to: 1) performing nursing procedures that before were performed exclusively by home nurses whose services have been often canceled, 2) enhance clinical, diagnostic and therapeutical methods, since second level doctors became difficult to access …” | Italy, male PCC | |

| Uncertainty & Stress | “Heightened anxiety.” | Australia, male PCC |

| “The increased work load, pressure of COVID-19 mitigation put in place.” | Democratic Republic of Congo, male PCC | |

| “Primary Care has borne the brunt of community anxiety and fear in the wake of COVID, often without proper protective equipment.” | Australia, female PHC academic | |

| “Healthcare workers are also afraid, we are old, we belong to the high-risk population, we do not have protective equipment, or the possibility to test for COVID.” | Slovakia, male PCC |

This was also experienced in Europe, “Few visits by patients and now all patients are typically first seen by a doctor, not a nurse …” (Finland, female PCC). And, “We formed Covid-19 clinics (offices) and call centres with family medicine staff (20% of all family physicians and nurses),” (Bosnia and Herzegovina, male PCC).

With shifting responsibilities came changes to the scope of practice for most primary care clinicians. Many respondents stated that they were doing much less direct patient care, including a decrease in mental health care (Australia), or saw a complete shift to one area of practice, such as one respondent from Mexico, “Now we (family physicians) are working in a respiratory triage, where we see only patients with respiratory symptoms and other family physicians see patients without respiratory symptoms,” (Mexico, female PCC).

While in some places primary care clinicians’ workloads decreased or disappeared, others experienced an increase in daily activities. Some clinicians assumed job responsibilities of different types of primary care clinicians, such as nursing procedures from home health care staff who could no longer work in-house due to governmental restrictions (Italy), and others switched departments to handle COVID-19 specific patients, “Being asked to do duties of an emergency physician/internal medicine etc.. primary care doctors are assumed to be footballs to kick into any department that needs staff,” (Trinidad and Tobago, female PCC).

These changes, shifts, and limitations to practice created an environment of uncertainty and stress for primary care clinicians, as evidenced by responses focused on increased anxiety and fear among staff (Australia, Slovakia) and pressures of increased workloads (Democratic Republic of Congo). One respondent from Nigeria stated, “Heightened fear among doctors across all levels as they are rescheduled regularly across units, especially the GPs,” (Nigeria, male PCC).

Another in Malaysia felt abandoned by the national government, “Private sector primary care physicians neglected and made to fend for their own. Nil government support,” (Malaysia, male PCC). Regardless of whether respondents were furloughed, had decreased hours, or were pulled in multiple directions with an increase in their workload, all groups felt an element of either uncertainty, anxiety, or stress associated with the changes to their daily clinical responsibilities.

3.2. Impact on patient care delivery

These primary care workforce changes impacted patient care at all levels. The majority of respondents made a distinction between treating and handling essential COVID-19 patient care and routine daily patient care, which in many countries had been deemed as non-essential in the early stages of the pandemic. For many primary care clinicians, the pandemic response (screening, testing, triaging, quarantining, and treatment) overran usual scopes of practice. One primary care clinician from Iraq commented,

“The marked professions have been more engaged in field work focusing on increasing community awareness about social distancing, disease symptoms and what to do when suspecting the illness, active case detection through sample collection for testing,” (Iraq, male PCC).

Another respondent from Israel made a similar statement,

“… preventive care has almost completely diminished, changes due to responsibilities of doctors and nurses to remotely care for COVID-19 positive patients (about 2/3 of cases are treated for by primary care clinicians as the majority of patients are at home/hotels) has resulted in a shift of care focus,” (Israel, female academic).

Because of the shift in primary care to COVID-19 focused essential care, many respondents commented on how much routine patient care was being ignored or forced to be put on hold per government mandates. One respondent from Switzerland stated, “All treatments except emergencies were not allowed. The police make controls in primary care doctors and physiotherapists for example to make sure that they did not treat “normal” patients!” (Switzerland, male PCC).

Responses on what was being identified as non-essential patient care were grouped into three areas (see Table 2 ): 1) concerns about cancer screenings being put on hold and care of chronic conditions being stopped (Canada); 2) an absence of preventative care and health education around diabetes, food nutrition, exercise management, and mental health care services (Malaysia); 3) and the cessation of well-child visits for specific age groups (Estonia).

Table 2.

Illustrative quotes by impact of patient care delivery subthemes.

| Patient Care Subthemes | Illustrative Quote | Country & Respondent Info |

|---|---|---|

| Essential COVID-19 Care | ||

| Screening, testing, triaging, quarantining, treatment | “… most health care workers are now prioritized to COVID screening and testing.” | South Africa, male PCC |

| “Doctors are more involved in COVID-19 containment activities … no time for attending and providing primary health care. Most of the academicians are involved in fever screening units.” | India, male PHC academic | |

| Non-Essential Care | “Suspension of all ‘non-urgent care.” | Belgium, gender diverse NGO/Civil Society Organization worker |

| Prevention Care | “Diabetes education, diet counseling & physical therapist consultations has been put on hold. Patients defaulted their prescription due to scare of COVID-19 and nobody to help them to go to the clinic for repeat prescription in view of the lock-down.” | Malaysia, female PCC |

| Cancer Screenings & Chronic Conditions | “Complete cessation of screening for cancer and cardiovascular disease. Decrease in care for chronic conditions eg diabetes.” | Canada, male PCC |

| “Home visit and care has stopped and chronic care of non- communicable diseases are not seen.” | South Africa, male PCC | |

| Well-Child Visits | “We still provide immunization and follow-up of babies until 1 year old, but no preventive visits for older children. Only acute care is provided. The same with midwifes- no preventive care.” | Estonia, female PCC |

These subthemes were shown in a response from the United Kingdom,

“Stopped a lot of routine work e.g. cervical smears and routine blood tests. Lots of people seem not to be seeking primary care advice at the moment - reduced workflow. However, there the patients have increased mental health needs,” (United Kingdom, gender diverse PCC).

And again from Ireland,

“Some patients need to still be seen/treated (palliative care, baby vaccinations, antenatal checks). Others need to wait for services to be restored (screening blood tests and ECGs, ear syringing, hospital out-patients services),” (Ireland, female PCC).

The overlapping of the subthemes are apparent, as the absence of providing patient care, under COVID-19 circumstances, took its toll on all areas of patient life, including at the community level, as referenced from a respondent in Uruguay, “We stopped doing checks on children, older adolescents, we stopped doing checks on chronic diseases such as diabetes or depression, we stopped community tasks,” (Uruguay, female PCC).

3.3. Shifts to new technology

One positive adaptation that survey respondents mentioned was the increase in the incorporation of technologies to handle patient visits. This included digital health and the increased use of e-mail and patient portals, and the use of apps with patients passing photos back and forth to clinicians. Many respondents reported a huge drop off for in-person visits, with their practices switching to 80–98% virtual visits either by phone, video conference, or email (United States, Cyprus, Estonia; see Table 3 ). A respondent from Spain commented, “Mostly the consultation is made by telephone interviews …. We are provided apps to be able to see photos of patients and to work at home (some days of week and not all teams do it),” (Spain, female PCC).

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes by shifts to new technology subthemes.

| Technology | Illustrative Quotes | Country & Respondent Info |

|---|---|---|

| Visit Volume Changes | “98% of patients are seen virtually by telephone or video.” | United States, male PCC |

| “80% of consultations are by phone or email.” | Cyprus, female PCC | |

| “Most of the consultations are done by phone calls (phone-visits) or by e-mail. Very few patients actually come to see a health care worker.” | Estonia, female PCC | |

| Safe & Convenient | “As a GP researcher and mental health trained GP, I have found telehealth to be a wonderful way to help people receive care while feeling safe at home.” | Australia, female PHC researcher |

| Accessibility | “Gps are moving to telephone consultations. Video platforms not available.” | United Kingdom, female PCC |

| “GPs have had to adapt with online prescription and pathology testing not available from on home computers etc.” | Australia, female PHC researcher | |

| Payments | “We are now able to do telemedicine-mostly through phone; these kinds of services are now paid by the assurance companies.” | Romania, female PCC |

The implementation of digital health technologies also helped keep primary care clinicians and patients safe from potential exposure and was a convenient way to reach patients during lockdown and quarantine protocols. “Tele consultations (allowed practitioners) to avoid overcrowding of health centres and unnecessary exposure of vulnerable populations,” (Saudi Arabia, female PCC).

However, the fast uptake in technology meant that some populations were either left out of being able to access care or had difficulties in doing so. This was shown in quotes discussing infrastructure issues to support internet capabilities and video technologies (United Kingdom), higher demands for online services, such as filling prescriptions (Australia), and the technology divide between urban and rural areas, “Shift to caring for patients virtually – in many places, especially rural areas, the infrastructure doesn't exist for these types of services so providers and patients both have had to find ways to adapt,” (United States, female PCC).

These accessibility challenges were also coupled with payment re-structuring (Romania) and reimbursement challenges, “Non face to face consultations have previously been unfunded - but we have had rapid rollout of government subsidised non-face-to-face consultations via telephone or video,” (Australia, male PCC).

4. Discussion

This paper highlights the experiences of individual primary care experts during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic to understand how on-the-ground circumstances were influenced by policies and protocols put in place by a variety of countries. Even though the survey's open-text responses were compiled from 69 different countries, representing all socio-economic tiers and political systems, there were numerous overlapping themes in how primary care clinicians and those workers supporting primary care services delivery were impacted. The pandemic has shown what other historical accounts of previous pandemics/epidemics have shown, that they exacerbate the lack of resources, health care access, economic and domestic stability, and death rates among minority and other marginalized groups with sweeping impacts to their communities (Galasso, 2020; Mein, 2020). This pandemic is no exception. Furthermore, our results show that the intentions of the Astana Declaration have not only not been met yet, but that the pandemic has forced governmental responses into the opposite direction in some instances (Kinder et al., 2021).

There are several similarities in primary care's responses as to how they have been impacted in the current pandemic globally, and these lessons learned should be remembered and incorporated going forward to address future pandemics/epidemics so that mistakes of the past do not recur (Peeri et al., 2020). Lessons learned from treating COVID-19 and charting historical trends with previous pandemics/epidemics are currently being compiled (Krist et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Mujica et al., 2020). This paper provides additional considerations from the perspectives derived from the on-the-ground experiences of primary care experts (see Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Lessons learned from experiences of primary care experts across the globe.

| Lesson Learned | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1. Pandemics illuminate weaknesses in healthcare systems for both patients (minority populations, lower socio-economic status individuals, people living in rural areas, etc.) AND the healthcare workforce (lack of resources, lack of or overburdened personnel, financial pressures, etc.). | Primary health care should take steps to reduce these disparities now before the next pandemic – this includes governmental support through proper funding, workforce development, and securing patient access to care. |

| 2. Pandemics apply unique uncertainty, stress, and anxiety which can contribute to or increase feelings of burnout, moral injury, or post-traumatic stress syndrome for primary care clinicians and staff. | Increased focus on mental health care services for healthcare workers starting at the beginning of the pandemic and continuing past its conclusion as needed is essential to maintain a healthy primary care workforce. |

| 3. Primary care clinicians have a generalist scope of practice and therefore can be utilized more effectively than other specialists to fit specific community needs for pandemic plans and response. | Primary care clinicians should be incorporated as an integral part of pandemic planning from the beginning. Considerations on utilizing PCCs should adhere to ethical considerations of decision-making, including autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. |

| 4. Deciding which patients deserve care (COVID-19 positive patients) versus those who do not (routine, continuity of care patients) places an ethical dilemma onto policy-makers, often leaving clinicians out of the decision-making process, with little room to shift care based on particular patient circumstances. | Public health guidelines should incorporate primary care perspectives on care delivery during a pandemic, including allowing clinicians flexibility to meet patient needs following the ethical guiding principles of decision-making (listed above). |

| 5. Digital health was a benefit to patients and clinicians, provided both parties were able to access it and clinicians were able to be compensated for using it. | Digital health should remain a staple of facilitating primary care services. Expanding access is necessary for marginalized populations, and governments/payors should appropriately financially reimburse for services utilizing these technologies. |

Shared and recurring themes across countries included the impacts of workforce issues, patient care demands, and the incorporation of advanced technologies; all playing a role in how primary care clinicians altered their provision of care during the first few months of the pandemic. Primary care was often at the mercy of governmental protocols and mandates which affected the workforce with employment shifts and challenges in providing patient care. Primary care workforce changes included clinician relocation, as many reported being moved to COVID-19 only clinics or other specialty departments such as the emergency room. Additionally, further stress and uncertainty was placed onto clinicians who had to do double work to fill the gaps of personnel shortages in nursing staff or other physicians being put under lockdown policies, or who had to quarantine after being exposed or infected. Because of the generalist nature of primary care's scope of practice, several respondents mentioned being thrown around or ordered to wherever they were needed, with little autonomy over daily scheduling decisions. The ability for primary care clinicians to be utilized most effectively based on community needs is an asset during a global public health crisis. Individuals providing patient care should not be over-worked and taken advantage of, but should be consulted concerning what positions and workloads they can handle best. Public health and national policy makers working collaboratively with primary care clinicians would provide deeper commitment from them and would increase perceived autonomy, likely reducing some of the emotional burden clinicians feel during these periods of increased stress and uncertainty (Huston et al., 2020).

An emergent theme among primary care clinician respondents was the emotional toll rendered by this pandemic, particularly with regards to their job security and ability to safely deliver patient care. Respondents expressed clear feelings of stress, anxiety, and fear over the possibility of contracting the virus given the absence of adequate personal protective equipment in primary care settings. These fears were compounded by perceptions of job insecurity, as well as serial uncertainty in their everyday schedules, scope of practice, and patient care responsibilities. Mental and emotional health needs of health care workers can lead to burnout, moral distress, and post-traumatic stress syndrome, as reported during other epidemics (Restauri & Sheridan, 2020) and preliminary findings of COVID-19 are showing similar patterns (Amanullah & Ramesh Shankar, 2020; Dutour et al., 2021; Khoo & Lantos, 2020; Sasangohar et al., 2020). As the pandemic drags on, primary care clinicians will need more mental and emotional support to prevent burnout.

Numerous respondents commented on shifts in roles and responsibilities and shared concerns about disruptions in their abilities to care for their usual patients. Many countries and health care disciplines established essential versus non-essential patient care guidelines early on (Ferorelli et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2020; Moletta et al., 2020), and this delineation ruptured the holistic continuity of care model that primary care prides itself on delivering. Routine and preventative care, such as cancer screenings, chronic disease maintenance, and well-child visits were put on hold as COVID-19 policies overtook patient access to ‘non-essential’ care. Our respondents stated the telehealth innovations helped ameliorate some of these discrepancies in care, but technology-based care was still limited in places due to technology access inequities.

Policy-makers, often without the input from primary care clinicians, established mandates on essential versus non-essential care, which had the potential to hurt patients and add increased stress and anxiety for clinicians. For future pandemics/epidemics, an ethical decision-making framework incorporating the concepts of autonomy, beneficence, non-malfeasance, and justice should be utilized to protect both patients and clinicians, providing flexibility at the clinician level, while working collaboratively with public health policies to meet patient and community needs (Arora & Arora, 2020; Huxtable, 2020; Kramer et al., 2020).

4.1. Limitations

In the interest of rapid data gathering amidst pandemic uncertainty, this project utilized a convenience and snowball sampling methodology to capture individual experiences of handling the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, respondents are not representative of their respective countries' policies or protocols, nor are they necessarily representative of other primary care clinicians’ experiences within those countries. Additionally, as this project was focused on the early months of the pandemic it may not reflect experience or concerns as the pandemic continued to evolve and as vaccination programs slowly bring the national epidemics under control.

4.2. Conclusion

Primary care respondents, across countries that vary considerably in size, geography, political ideology, per capita wealth, and type of health system, consistently reported high levels of stress, unprecedented and rapid adaptation of their delivery systems, and tremendous uncertainty in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and provided lessons for response to future health crises. Primary health care provides the opportunity to utilize both primary care and public health to approach pandemic plans that reduce disparities for patients and communities, allow flexibility at the local level for treatments, and incorporate mental health services as a key component of health care for both workers and patients. There were differences in death rates, pandemic plans, and the utilization of health care systems, but primary care experts felt COVID-19 impacts similarly across countries, regardless of socio-economic status and political systems.

Author contributions

Melina K. Taylor – Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, project administration. Karen Kinder – Writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration. Joe George – Investigation, writing – review and editing. Andrew Bazemore – Writing -review and editing, project administration, supervision. Cristina Mannie – Writing – review and editing, formal analysis. Robert Phillips – Writing, review and editing. Stefan Strydom – Writing – review and editing, formal analysis. Felicity Goodyear-Smith – Investigation, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC), Ref number 024557 and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank our international experts Prof Michael Kidd (Principal Medical Advisor, Australian Government), Dr Dionne Kringos (Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, the Netherlands), Dr Ramiro Gilardino (Professional Society for Health Economics &Outcomes Research, USA), Assoc Prof Ben Harris-Roxas (University of New South Wales, Australia) Dr Priya Balasubramaniam Kakkar (Public Health Foundation of India) and Prof Kirsty Douglas, Dr Jane Desborough and Dr Sally Hall (Australian National University) for providing advice and/or piloting of our survey. Thanks also to Jose M Ramirez-Aranda (University of Nuevo León, Mexico) for the Spanish translation and Dr Viviana Martinez-Bianchi (Duke University in North Carolina, USA) for back-translation. And thanks to Allison Morris for her graphic design expertise. Lastly, we would like to express our gratitude to all the primary care experts who took time out of their busy lives to answer our survey.

References

- Al Ghafri T., Al Ajmi F., Anwar H., Al Balushi L., Al Balushi Z., Al Fahdi F., Al Lawati A., Al Hashmi S., Al Ghamari A., Al Harthi M., Kurup P., Al Lamki M., Al Manji A., Al Sharji A., Al Harthi S., Gibson E. The experiences and perceptions of health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in muscat, Oman: A qualitative study. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2020;11 doi: 10.1177/2150132720967514. 215013272096751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanullah S., Ramesh Shankar R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: A review. Healthcare. 2020;8(4):421. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora A., Arora A. Ethics in the age of COVID-19. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2020;15(5):889–890. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02368-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declaration of Astana . World Health Organization & United Nation’s Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2018. Global conference on primary health care (p. 12)https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutour M., Kirchhoff A., Janssen C., Meleze S., Chevalier H., Levy-Amon S., Detrez M.-A., Piet E., Delory T. Family medicine practitioners' stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Family Practice. 2021;22(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01382-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferorelli D., Mandarelli G., Solarino B. Ethical challenges in health care policy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2020;56(12) doi: 10.3390/medicina56120691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasso V. COVID: Not a great equalizer. CESifo Economic Studies. 2020;66(4):376–393. doi: 10.1093/cesifo/ifaa019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez T., Anaya Y.B., Shih K.J., Tarn D.M. A qualitative study of primary care physicians' experiences with telemedicine during COVID-19. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2021;34(Supplement):S61–S70. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear-Smith Felicity, et al. Relationship between the perceived strength of countries’ primary care system and COVID-19 mortality: an international survey study. BJGP Open. 2020;4 doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101129. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear-Smith Felicity, et al. Primary care perspectives on pandemic politics. Global Public Health. 2021;16 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1876751. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston P., Campbell J., Russell G., Goodyear-Smith F., Phillips R.L., van Weel C., Hogg W. COVID-19 and primary care in six countries. BJGP Open. 2020;4(4) doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101128. bjgpopen20X101128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxtable R. COVID-19: Where is the national ethical guidance? BMC Medical Ethics. 2020;21(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12910-020-00478-2. s12910-020-00478–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo E.J., Lantos J.D. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatrica. 2020;109(7):1323–1325. doi: 10.1111/apa.15307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinder Karen, et al. Integrating primary care and public health to enhance response to a pandemic. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2021;22 doi: 10.1017/S1463423621000311. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J.B., Brown D.E., Kopar P.K. Ethics in the time of coronavirus: Recommendations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2020;230(6):1114–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krist A.H., DeVoe J.E., Cheng A., Ehrlich T., Jones S.M. Redesigning primary care to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the midst of the pandemic. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2020;18(4):349–354. doi: 10.1370/afm.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin M., Engelhard D., Piterman L., Thomas S. Response of general practitioners to infectious disease public health crises: An integrative systematic review of the literature. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2013;7(5):522–533. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.L.T., West S., Tang A.C.Y., Cheng H.Y., Chong C.Y.Y., Chien W.T., Chan S.W.C. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of school nurses during COVID-19 pandemic as the frontline primary health care professionals. Nursing Outlook. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.12.003. S0029655420307107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Xu K., Wang X., Wang W. From SARS to COVID-19: What lessons have we learned? Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020;13(11):1611–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Vervoort D., Reddy C.L., Park K.B., Makasa E. Emergency and essential surgical healthcare services during COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries: A perspective. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;79:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mein S.A. COVID-19 and health disparities: The reality of “the great equalizer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2020;35(8):2439–2440. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05880-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moletta L., Pierobon E.S., Capovilla G., Costantini M., Salvador R., Merigliano S., Valmasoni M. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;79:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujica G., Sternberg Z., Solis J., Wand T., Carrasco P., Henao-Martínez A.F., Franco-Paredes C. Defusing COVID-19: Lessons learned from a century of pandemics. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020;5(4):182. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5040182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeri N.C., Shrestha N., Rahman M.S., Zaki R., Tan Z., Bibi S., Baghbanzadeh M., Aghamohammadi N., Zhang W., Haque U. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: What lessons have we learned? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2020;49(3):717–726. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado, N. M. de B. L. Rossi T.R.A., Chaves S.C.L., Barros S. G. de, Magno L., Santos, H. L. P. C. dos. Santos, A. M. dos The international response of primary health care to COVID-19: Document analysis in selected countries. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2020;36(12) doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00183820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasanathan K., Evans T.G. Primary health care, the declaration of Astana and COVID-19. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2020;98(11):801–808. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.252932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawaf S., Allen L.N., Stigler F.L., Kringos D., Quezada Yamamoto H., van Weel C. Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. The European Journal of General Practice. 2020;26(1):129–133. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2020.1820479. On behalf of the Global Forum on Universal Health Coverage and Primary Health Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restauri N., Sheridan A.D. Burnout and posttraumatic stress disorder in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Intersection, impact, and interventions. Journal of the American College of Radiology: JACR. 2020;17(7):921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasangohar F., Jones S.L., Masud F.N., Vahidy F.S., Kash B.A. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2020;131(1):106–111. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B., Shi L., Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Foundation Sustainable development goals. 2021. https://unfoundation.org/what-we-do/issues/sustainable-development-goals/ (n.d)

- Verhoeven V., Tsakitzidis G., Philips H., Van Royen P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the core functions of primary care: Will the cure be worse than the disease? A qualitative interview study in flemish GPs. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Ye Y., Wang Y., Qian Y., Pan J., Lu Y., Fang L. Primary care practitioners' barriers to and experience of COVID-19 epidemic control in China: A qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2020;35(11):3278–3284. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06107-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]