Abstract

The objectives were to analyze the effects of housing cow–calf pairs in drylots (DL) or pasture (PAST) on cow performance and reproduction as well as calf performance and behavior through feedlot receiving. Simmental × Angus (2 yr; 108/yr; 81 ± 15.3 d postpartum) spring-calving cows were stratified by age, body weight (BW), body condition score (BCS), and calf sex and allotted to six groups per year. Groups were randomly assigned to one of two treatments: DL or PAST. Cows in DL were limit-fed at maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to the cow diet in an adjacent pen. Pairs on PAST were rotationally grazed and calves received creep ad libitum 3 wk prior to weaning. On day 110, calves were fence-line weaned and behavior was observed on days 111 and 112. On day 116, calves were transported 272 km to a feedlot for a 42-d receiving period. Behavior was evaluated again on days 117 and 118. Data were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS except reproductive data which was analyzed using the GLIMMIX procedure. Cows on DL had greater (P ≤ 0.01) BW and BCS at weaning. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.42) detected in reproductive data. Cows on DL had greater (P = 0.02) milk production. Calves on DL had greater BW (P ≤ 0.01) on day 55 and at weaning and greater preweaning average daily gain (ADG). There were treatment × time effects (P = 0.01) for lying and eating on days 111 and 112. More DL calves were eating in the morning and lying in the evening. More (P < 0.01) PAST calves were walking on day 111. Pasture calves vocalized more (P ≤ 0.01) on day 112. On day 117, more (P ≤ 0.05) pasture calves were lying and eating, and DL vocalized more. On day 118, treatment × time and treatment effects were detected (P ≤ 0.02) for lying and walking. More PAST calves were lying and more DL calves were walking. Drylot calves had greater (P ≤ 0.02) BW at the beginning and end of the receiving phase. Pasture calves had greater (P < 0.01) ADG and tended (P = 0.10) to have greater gain efficiency during feedlot receiving phase. In conclusion, housing cow–calf pairs in drylots improved BW, BCS, and milk production of cows but did not affect reproductive performance. Drylot calves had increased BW and ADG during the preweaning phase. Calf behavior at weaning and receiving was influenced by preweaning housing. Pasture calves had improved receiving phase ADG and feed efficiency but were still lighter than drylot calves after 42-d receiving phase.

Keywords: cow–calf, drylot, housing systems, pasture

Introduction

Historically, cow–calf producers have maintained cow–calf pairs on pastures and supplemented them as needed to meet requirements. The availability and quality of grass throughout the year often determine the success of a producer’s system (Ball et al., 2007). Urbanization has caused an increase in land prices making pasture expensive and less available for producers. Additionally, Midwest farmland is made up of fertile soil which is ideal for crop production causing the conversion of pastureland to cropland to increase. Therefore, cattle producers are seeking an alternative system for housing cow–calf pairs.

Maintaining cow–calf pairs in a drylot system is not a new concept as drylots have proven to be an effective alternative when there is a shortage of forage availability (Thomas and Durham, 1964; Loerch, 1996; Gardine et al., 2019). Feeding cattle in drylots gives producers more flexibility to use low-cost feedstuffs such as corn or corn co-products (Jenkins et al., 2015). These co-products, such as distillers grains or corn gluten feed, effectively meet energy needs during lactation (Shike et al., 2009) and increase cow BW and BCS during gestation and lactation (Wilson et al., 2016). Energy requirements of beef cattle housed in drylots can be up to 20% less than cattle grazing pasture (Miller et al., 2007). Drylots are also commonly used during the winter months in the Midwest. Over the years, they have provided advantages such as the ability to monitor cows during parturition (Gunn et al., 2014) and the drier and less windy conditions can decrease maintenance requirements (NASEM, 2016). Additionally, drylots have the potential to increase the adoption of synchronization and aid in maximizing on artificial insemination and other technologies in systems where a working facility can be easily accessed (Lardy, 2017). Ultimately, a drylot system can provide producers flexibility of management.

Although drylot systems have proven to be a viable alternative during the winter months (Gardine et al., 2019), limited research is available studying the effects of housing cattle in these systems during the summer months. Cows grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue have reduced performance and reproduction (Gay et al., 1988; Porter and Thompson, 1992) and their progeny has reduced birth and weaning BW (Watson et al., 2004). Alternative drylot or confinement systems may also be of greater interest in regions where predominate forage is endophyte-infected tall fescue. Evaluation of impacts of these systems for extended periods of time on cow and calf performance is needed. It was hypothesized that cows housed in a drylot would better maintain body weight and body condition score compared with cows on pasture. Additionally, we hypothesized that calves raised in a drylot would be better adapted to a feedlot environment and display less behavioral signs of stress at weaning and feedlot arrival which would contribute to increased performance. The objective was to determine the effects of housing cow–calf pairs in a drylot compared to pasture on cow performance and reproduction, as well as calf performance and behavior at weaning and through feedlot receiving.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Illinois (Protocol #20083) and followed the guidelines recommended in the Guide for the Care and Use of Agricultural Animal in Agricultural Research and Teaching (FASS, 2020).

Animals, experimental design, and treatments

To evaluate the effects of housing cow–calf pairs on drylots (DL) or pasture (PAST) on cow performance and reproduction as well as calf performance and behavior at weaning and through feedlot receiving, a 2-yr study with 216 spring-calving (81 ± 15.3 d postpartum), Angus × Simmental cows (body weight [BW] = 659.4 ± 88.1 kg) and their progeny were evaluated at the Orr Agricultural Research and Demonstration Center (OARC) in Baylis, IL from May to August. Prior to the initiation of the study, cows had been managed similarly and historically are on pasture from May through December and are housed on drylots from December through May. These cows calved (Feb–March) on drylots and were limit-fed the same total mixed ration (TMR) described as TMR 1 for both years in Table 1 prior to the start of the experiment.

Table 1.

Drylot ration composition, amount fed, and proximate analysis on a dry matter basis

| Item | Year 1 | Year 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMR 1 | TMR 2 | TMR 3 | TMR 1 | TMR 2 | TMR 3 | |

| Ingredient, kg | ||||||

| Corn silage | 4.4 | 3.6 | – | 7.8 | 3.6 | – |

| Ground hay | 2.4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| DDGS1 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Corn stalks | 2 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.4 |

| Soybean hulls | – | – | 2.4 | – | – | 2.4 |

| Dry rolled corn | 2.3 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Supplement2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Cow limit-fed TMR, kg/d | 14 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 14.5 | 10.9 | 11.1 |

| Calf intake3, kg/d | 0.9 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 3.8 |

| Number of weeks fed4 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 2 |

| Analyzed nutrient content, % | ||||||

| Dry matter | 68.1 | 68.2 | 83.4 | 62.1 | 69.3 | 87 |

| Organic matter | 88.7 | 88.4 | 87.6 | 89.5 | 89.1 | 88.9 |

| NDF5 | 38.3 | 33.7 | 41.7 | 37.6 | 33.5 | 44.4 |

| ADF6 | 18.8 | 16.8 | 23.0 | 19.5 | 16.9 | 25.6 |

| Ether extract | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4 | 3.6 | 4 | 3.6 |

| Crude protein | 9.4 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 10.4 |

| TDN7 | 72.2 | 74.2 | 68.0 | 71.5 | 74.1 | 65.3 |

1Dried distillers grains with solubles.

2Supplement contained 87.7% ground corn, 8.9% limestone, 1.8% trace mineral salt [8.5% Ca as calcium carbonate, 5% Mg as magnesium oxide and magnesium sulfate, 7.6% K as potassium chloride, 6.7% Cl as potassium chloride, 10% S as S8, prilled, 0.5% Cu as copper sulfate and Availa-4 (Zinpro Performance Minerals; Zinpro Corp, Eden Prairie, MN), 2% Fe as iron sulfate, 3% Mn as manganese sulfate and Availa-4, 3% Zn as zinc sulfate and Availa-4, 278 mg/kg Co as Availa-4, 250 mg/kg I as calcium iodate, 150 mg/kg Se as sodium selenite, 2,205 KIU/kg VitA as retinyl acetate, 662.5 KIU/kg VitD as cholecalciferol, 22,047.5 IU/kg VitE as DL-α-tocopheryl acetate, and less than 1% crude protein, fat, crude fiber, salt], 0.1% Rumensin 90 (198 g monensin/kg, Rumensin 90; Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, IN), and 1.5% fat.

3Calves were offered free-choice access to same.

4There were differences in the amount of weeks diets were fed due to ingredient availability.

5Neutral detergent fiber.

6Acid detergent fiber.

7Total digestible nutrients; calculated %TDN = 90.82 + (CP × 0.0353) − (ADF × 1.01).

A stratified, randomized design was used for this experiment. Cows were stratified by age, BW, body condition score (BCS: emaciated = 1; obese = 9; as described by NASEM, 2016), calving date, previous treatment, and sex of the calves and allotted to six groups each year. Groups were randomly assigned to one of two treatments: DL or PAST. Cows on DL were maintained in a 21.9- × 11-m concrete lot that allowed 13.4 m2/cow with a 14.6- × 7.3-m shed allowing 5.9 m2/cow. Their calves had access to an adjacent creep pen that was an 11.0- × 11.0-m concrete lot with a 7.3- × 7.3-m open-front shed. The area under roof was bedded as needed during the treatment period with ground stalks and wheat straw.

Drylot cows were limit-fed a TMR (Table 1) formulated to maintenance (NASEM, 2016) in a 14.6-m concrete bunk allowing for 0.8 m/cow. There were three sequential TMR fed each year that consisted of corn silage, dried distillers grains, ground hay, ground stalks, corn, soybean hulls, and mineral. There were minor year-to-year variations in the TMR due to ingredient availability. The TMR 1 in year 1 included ground hay, whereas TMR 1 in year 2 did not. In both years, TMR 2 was fed until corn silage was no longer available. The TMR 3 replaced corn silage with soybean hulls, corn, and ground stalks. Calves in the drylot were fed the same TMR as cows ad libitum in an adjacent creep pen with a 7.3-m concrete bunk allowing for 0.4 m/calf.

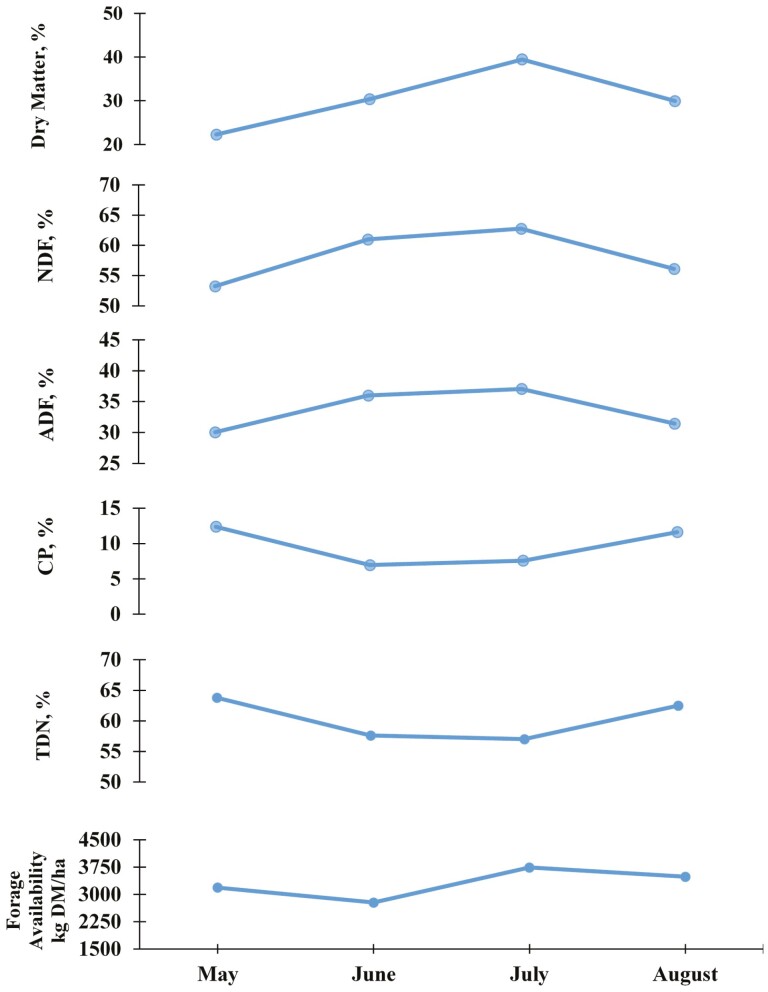

Cow–calf pairs on PAST were managed on a rotational grazing system stocked at 4.01 pairs/ha, and each group was rotated between two pastures every 3–4 wk, thus allowing 3–4 wk rest between grazing. Pastures were comprised of a mix of red clover (Trifolium pretense), white clover (Trifolium repens), and endophyte-infected tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Pasture nutrient composition can be found in Figure 1. Weather data were collected from Water and Atmospheric Resources Monitoring Program (Illinois Climate Network and Illinois State Water Survey) and can be found in Figure 2. The pairs on PAST had access to free-choice commercial mineral (Pike Feeds, Pittsfield, IL; 12% to 14% Ca, 5% P, 18% to 20% Na, 6% Mg, 375 mg/kg I, 400,000 IU/kg of vitamin A, 40,000 IU/kg of vitamin D3, 400 IU/kg of vitamin E). Calves on PAST were fed creep (Pike 14% Beef Creep Pellet #C029, Pittsfield, IL; 85.3 % dry matter [DM] 86.0% organic matter [OM], 34.0% neutral detergent fiber [NDF], 19.2% acid detergent fiber [ADF], 2.6% fat, 14.4% crude protein [CP]) ad libitum 3 wk prior to weaning to acclimate calves to processed feeds before weaning (Lardy and Maddock, 2007).

Figure 1.

Forage quality (percentage neutral detergent fiber [NDF], acid detergent fiber [ADF], and crude protein [CP], total digestible nutrients [TDN], and forage availability) of endophyte-infected fescue (Festuca arundinacea), white clover (Trifolium repens), and red clover (Trifolium pretense) pastures from May to August.

Figure 2.

Comparison of precipitation (cm) and temperature (°C) at Orr Agricultural Research and Demonstration Center (OARC) in Baylis, IL from May 2019 to August 2019 and May 2020 to August 2020.

Prior to the initiation of the experiment, cows were synchronized with a 7-d CO-Synch + CIDR protocol as outlined by Grussing et al. (2016) and artificially inseminated on day 0 (AI; 81 ± 15.3 d postpartum). Eleven days following AI, cows were exposed to bulls who had previously passed breeding soundness exams for a 51-d breeding season with one bull per group. Conception to AI and overall pregnancy were determined at 35 and 102 d post-AI, respectively. Conception to AI and overall pregnancy rates were determined by a trained technician via ultrasonography (Aloka 500 instrument [Wallingford, CT]; 7.5 MHz general purpose transducer array).

All cows and calves received 1 mL/9.98 kg BW Eprinex (Merial, Duluth, GA) and were tagged with Python tags (2 per cow, 1 per calf) on day 34. Per OARC vaccination protocol, on day 62, calves received 5 mL Bovi-shield Gold FP5 VL5 HB (Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ), 2 mL Ultra Choice 8 (Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ), 2 mL MpB Guard (American Health Inc., Ronkonkoma, NY), and Covexin 8 (Merck, Madison, NJ) were given to steers at time of castration. A second round of vaccinations was given on day 89; calves received 5 mL Bovi-shield Gold FP5 VL5 HB (Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ), 2 mL Ultra Choice 8 (Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ), 2 mL MpB Guard (American Health Inc., Ronkonkoma, NY), and 1 mL/nostril Inforce 3 (Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ). Calves were poured with 1mL/10 kg of Dectomax (Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI) before shipping to the University of Illinois Beef Cattle and Sheep Field Research Laboratory in Urbana, IL.

At the time of weaning (calf age = 191 ± 15.3 d), PAST cows and calves were brought into the drylot for a 6-d fence-line wean. The creep gate on the drylot calf pen adjacent to the cow pens was closed so that drylot cows and calves stayed in their original pens. All cows and calves were sorted and separated with only nose-to nose access to one another through the fence. The PAST cows and calves were housed identical to the DL cows during the fence-line wean period. During this time, treatment groups remained on the same diet to minimize potential digestive upset at weaning and reduce potential for diet change to influence behavior. Drylot calves were fed the same TMR that was fed preweaning (TMR 3 in Table 1). Pasture calves had ad libitum access to hay (84.7% DM, 86.8% OM, 61.6% NDF, 53.0% ADF 1.4% fat, 7.5% CP) and to the same 14% commercial creep offered preweaning.

After the 6-d fence-line wean, calves were weighed and shipped 272 km to the University of Illinois Beef Cattle and Sheep Field Research Laboratory in Urbana, IL. Upon arrival, calves were weighed and sorted by original dam pen and sex. Calves were assigned to 12 pens/yr [7–11 calves per pen (4.88 m × 10.36 m)] in the same barn with treatments separated and on opposite ends of the barn. Calves from each treatment were separated by six empty pens to minimize influence from other treatment on behavior. The barn was constructed of a wood frame with a ribbed metal roof and with siding on the north, west, and east sides. The south side of the barn was covered with polyvinyl chloride–coated 1.27- × 1.27-cm wire mesh bird screen and equipped with retractable curtains for wind protection. Pens had 4.88 × 4.88 m level slotted floors and 4.88 × 4.88 m solid sloped floor covered by interlocking rubber matting. Calves were fed in 4.27-m concrete feed bunks. Days 116 to 158 are referred to as the receiving period. Calves were offered ad libitum access to a receiving diet (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ingredient and nutrient composition of calf receiving diet on a dry matter basis

| Item | Receiving1 |

|---|---|

| Ingredient, % | |

| Corn silage | 32 |

| Grass hay | 20 |

| Corn2 | 20 |

| MWDGS3 | 18 |

| Supplement4 | 10 |

| Analyzed nutrient content, % | |

| Dry matter5 | 47.6 |

| Organic matter | 88.7 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 31.1 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 15.9 |

| Ether extract | 4.2 |

| Crude Protein | 12.6 |

1Receiving diet was provided ad libitum from days 116 to 158.

2High moisture corn was used in year 1, and dry rolled corn was used in year 2.

3Modified wet distillers grains.

4Supplement contained 76.2% ground corn, 15.9% limestone, 6.0% urea, 0.91% trace mineral salt (trace mineral salt = 8.5% Ca as CaCO3, 5% Mg as MgO and MgSO4, 7.6% K as KCl2, 6.7% Cl as KCl2 10% S as S8 [prilled], 0.5% Cu as CuSO4 and Availa-4 [Zinpro Performance Minerals; Zinpro Corp, Eden Prairie, MN], 2% Fe as FeSO4, 3% Mn as MnSO4 and Availa-4, 3% Zn as ZnSO4 and Availa-4, 278 mg/kg Co as Availa-4, 250 mg/kg I as Ca(IO3)2, 150 Se mg/kg Na2SeO3, 2,205 KIU/kg vitamin A as retinyl acetate, 662.5 KIU/kg vitamin D as cholecalciferol, 22,047.5 IU/kg vitamin E as dl-α-tocopheryl acetate, and less than 1% CP, fat, crude fiber, and salt), 0.155% Rumensin 90 (198 g monensin/kg Rumensin 90; Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, IN), 0.1% Tylosin 40 (88 g tylan/kg Tylosin 40; Elanco Animal Health), and 0.75% soybean oil.

5The differences in corn made for slight differences in DM% between years: 44.3% in year 1 and 50.9% in year 2.

In year 2, one cow from the DL treatment was removed from the study due to excessive BW loss, and all data from this cow/calf pair were removed from analysis. In year 2, one calf from the PAST treatment died from chronic respiratory disease, and all data from this calf were removed from analysis. During the preweaning phase, two calves from the PAST treatment were treated for respiratory disease in year 1. In year 2, one calf from the PAST and two calves from DL were treated for respiratory disease. One calf was also treated for lameness in year 2. During the receiving phase, one calf from PAST was treated for respiratory disease in year 1 and one DL calf was treated for rectal prolapse and one DL calf for lameness in year 2.

Sample collection and analytical procedures

Cow BW was collected at the initiation of the trial (81 ± 15.3 d postpartum; day 0) and at weaning (192 ± 15.3 d postpartum; day 111). A 4% pencil shrink was applied to cow BW on day 0 to account for gut fill since cows had been fed a common diet before the initiation of the study. At weaning, a single, shrunk BW was collected (16–20 h feed restriction; access to water). Cow BCS (emaciated = 1; obese = 9; as described by NASEM, 2016) was evaluated at the same time points as BW.

Preweaning calf BW was collected at the initiation of the trial (81 ± 15.3 d age; day 0), at the time of weigh-suckle-weigh (WSW; 135.9 ± 15.1 d of age; day 55), at weaning (191 ± 15.3 d of age; day 110), and at the end of the fence-line wean (197 ± 15.3 d of age; day 116). Calf average daily gain (ADG) was determined through the preweaning period.

Milk production was estimated using the weigh-suckle-weigh (WSW) technique (135.9 ± 15.1 d postpartum; day 55 [Beal et al., 1990]). Cows and calves were separated for 12 h. Following separation, calves were weighed prior to and after nursing. The difference between empty and full calf BW was assumed to be representative of 12-h milk production. The 12-h milk production was doubled to estimate 24-h milk production. Milk production was determined on all cows and milk samples were collected from a random sub-set of 36 cows per treatment (6 cows/pen). Milk composition samples (50 mL) were collected (Clements et al., 2017) by hand milking following injection of 1 ml/cow oxytocin intramuscularly (Oxoject; Henry Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH) and analyzed for percent fat, percent protein, percent lactose, total solids, and milk urea nitrogen (MUN; Dairy Lab Services, Dubuque, IA).

Cow hair coat scores (HCS; 1 to 5, in which 1 = slick, short coat and 5 = unshed, full winter coat) were evaluated and recorded at initiation of the trial (81 ± 15.3 d postpartum; day 0) and weaning (191 ± 15.3 d postpartum; day 110). Calf dirty score (DS) were evaluated and recorded at the initiation of the trial (81 ± 15.3 d of age; day 0), weaning (191 ± 15.3 d of age; day 110), and at the end of the receiving phase (240 ± 15.3 d of age; day 158). Dirty score was scored on a 1 to 5 scale, in which 1 = no tag, clean hide and 5 = lumps of manure attached to the hide continuously on the underbelly and side of the animal from brisket to quarter, as described by Busby and Strohbehn (2008).

Locomotion score was evaluated at the initiation of the trial, AI pregnancy-check (115.9 ± 15.3 days postpartum; day 34), and weaning on a 4-point scale to determine lameness (0 = normal; animal walks normally, with no apparent lameness or change in gait: 3 = severe lameness; animal applies little to or no weight to affected limb and is reluctant or unable to move; as described by the Zinpro Step-Up Locomotion Scoring System (Zinpro, 2013). During the trial, cows identified with foot lameness were treated for either foot rot or digital dermatitis. Per OARC farm protocol, cows treated for foot rot received 3 mL/45.36 kg of Noromycin LA-300 (Norbrook Inc, Lenexa, KS). Digital dermatitis was treated by wrapping the hoof with 10 ml/foot of Noromycin LA-300. Foot scores were collected on cows and calves at the same time-points as locomotion scores and quantified using the American Angus Association’s simple foot scoring system. The system characterizes cattle for two traits: foot angle and claw set. Both scores are ranked on a 1–9 system with 5 being ideal. Claw set (1 to 9, in which 1 = extremely weak, open divergent claw set and 9 = extreme scissor claw and/or screw claw) and foot angle (1 to 9, in which 1 = extremely straight pasterns and 9 = extremely shallow heel and long toe). Claw set and foot angle were evaluated on calves on days 0 and 110. All foot scoring data were collected by two trained observers and scores were averaged.

Calf behavior was observed for 12 h on day 111 (calf age = 192 ± 15.3 d) and day 112 (calf age = 193 ± 15.3 d) during the fence-line wean. Cattle were fed at 0800 h both days and behavior was observed from 0800 to 1900 h on day 1 (due to weighing the cows at 0700 h) and from 0700 to 1800 h on day 2. Behavior was observed every 20 min, and three observations were averaged to represent each hour. The number of calves lying, walking, eating, and drinking in each pen were recorded. Pens were sampled for vocalizations for 2 min per pen for each 20-min interval. Any audible vocal sound that could be attributed to a specific pen being evaluated was counted as a vocalization. Total number of vocalizations during each of the three 2-min periods was used to calculate number of vocalizations/calf per hour.

Upon arrival to the feedlot, calves were sorted by original dam pen and sex. Body weight was recorded upon arrival on day 116. An average of the pre-ship BW and arrival weight was used for initial weight of receiving period. Final BW for all calves was determined by averaging a 2-d consecutive BW on days 157 and 158. Calves were scored for DS, claw set, and foot angle at the end of the receiving phase. Dry matter intake (DMI), ADG, and gain:feed (G:F) were evaluated to determine calf performance. Behavior was observed on days 117 and 118 of receiving phase for 12 h. Cattle were fed at 0700 h and calf behavior was observed from 0700 to 1800 h on both days. Behavior was observed using the same collection method that was used during the fence-line wean.

Sample analysis

During the pre-weaning phase, ingredient samples were collected every 2 wk from DL and were composited for analyses. Forage samples from PAST treatment were hand-clipped every 2 wk and composited by month. Forage availability was quantified as cows rotated out of pastures by using a falling plate meter (Jenquip, Fielding, New Zealand) to collect 12 random measurements in each pasture. Average forage availability (kg DM/ha) was averaged by month and reported in Figure 1 (year 2 only). Feed refusals were collected every 2 wk and at the time of a diet transition for calves in the drylot. Creep refusals for calves on pasture treatment during the preweaning phase were collected weekly for each of the final 3 wk prior to weaning. Feed refusals were collected at the end of the fence-line wean phase and weekly during the receiving phase. All feed refusals were weighed and a subsample was collected for DM determination.

Forage and ingredient samples were dried in a 55 °C forced air oven for 3 d and then ground with a Wiley mill (1-mm screen, Arthur H. Thomas, Philadelphia, PA). Forage and ingredient samples were analyzed for dry matter (24 h at 105 °C), neutral detergent fiber, and acid detergent fiber (using Ankom Technology methods 5 and 6, respectively; Ankom200 Fiber Analyzer, Ankom Technology, Macedon, NY), ether extract (using Ankom Technology method 2; Ankom XT10 Fat Analyzer, Ankom Technology), crude protein (Leco TruMac, LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI), and organic matter (600 °C for 12 h; Thermolyte muffle oven Model F30420C, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The percent TDN was calculated (Clemson University Agricultural Service Laboratory, 1996) for pasture using %TDN = 81.38 + (CP × 0.36) − (ADF × 0.77) and for TMR using %TDN = 90.82 + (CP × 0.0353) − (ADF × 1.01).

Statistical analysis

Pen was used as the experimental unit for all variables. The MIXED procedure of SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC) was utilized to analyze all variables excluding cow reproductive performance and percentage of cows treated for foot lameness. Random effects included year and pen nested in treatment for models with individual animal observational units. Fixed effects of treatment, previous treatment, and cow age were all included in the model statements for all variables for cows. For cow BW, BCS, HCS, foot angle, claw set, and locomotion score, individual animal was considered as the observational unit with day 0 values included as a fixed effect for each of the following time points for the respective parameters. Treatment, calf age, sex, sire, and cow age were included as fixed effects in the models for all variables pertaining to calf performance. For calf BW, DS, foot angle, and claw set, individual animal was considered as the observational unit with day 0 values included as a fixed effect for each of the following time points for the respective parameters. During the fence-line wean and receiving phase, growth performance parameters were evaluated using pen averages as the observational unit with treatment and sex as fixed effects.

The GLIMMIX procedure of SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC) was utilized to analyze cow reproductive performance (AI conception rate and overall pregnancy rate) and percentage of cows treated for foot lameness. For those parameters, previous treatment and treatment were included in the model as fixed effects and year and pen nested in treatment were included as random effects. The REPEATED statement was used to model the repeated measurements within pen for calf behavior and vocalizations and the compound symmetry covariance structure was used based on the lowest AIC value. Pen was the observational unit for behavior. Fixed effects included sex, treatment, time, and the interaction of treatment and for behavior. Year was included as a random effect. Least square means function of SAS was used to separate treatment means. The SLICE statement was used to separate least square means when the interaction of treatment and time was significant (P ≤ 0.05). Significance was declared at P ≤ 0.05 and trends discussed at 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10.

Results

Cow performance, milk production, and milk composition

Cow BW and BCS data are reported in Table 3. There was no difference (P = 0.59) in cow BW on day 0; however, DL had greater BW (P < 0.01) at time of weaning compared with cows maintained on PAST. There was no differences (P = 0.53) detected in BCS on day 0; however, cows in DL had greater BCS (P < 0.01) at time of weaning than cows on PAST. There were no differences (P = 0.92) in cow HCS on day 0. Hair coat score was greater (P < 0.01) for cows on PAST at weaning compared to cows on DL. Cows on DL had greater (P = 0.02) milk production (Table 3) compared with cows on PAST. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.18) detected for percent fat, percent protein, percent lactose, or total solids between treatments. However, PAST cows had greater (P = 0.01) MUN compared to DL cows.

Table 3.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on cow body weight (BW), body condition score (BCS), hair coat score (HCS), milk production, and milk composition

| Item | Treatment1 | SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | PAST | |||

| BW, kg | ||||

| Initial2 | 686 | 680 | 10.6 | 0.59 |

| Weaning3 | 662 | 599 | 8.4 | <0.01 |

| BCS | ||||

| Initial | 6.7 | 6.6 | 0.10 | 0.53 |

| Weaning | 6.2 | 5.9 | 0.09 | <0.01 |

| Cow HCS4 | ||||

| Initial | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.26 | 0.92 |

| Weaning | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| Milk production5, kg/d | 7.6 | 5.3 | 0.60 | 0.02 |

| Milk composition6 | ||||

| Fat, % | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.35 | 0.57 |

| Protein, % | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.12 | 0.26 |

| Lactose, % | 4.9 | 4.8 | 0.09 | 0.18 |

| Total Solids | 10.6 | 10.7 | 0.34 | 0.61 |

| MUN, mg/dL | 4.8 | 13.9 | 1.00 | 0.01 |

1DL cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR, and PAST cows rotationally grazed pasture, calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning.

281 ± 15.3 d postpartum, a 4% pencil shrink was applied to BW.

3 192 ± 15.3 d postpartum, 16–20 h shrink with access to water was applied to account for differences in gut fill.

4Hair coat score; 1 to 5, in which 1 = slick and 5 = unshed.

5Determined by weigh-suckle-weigh at 142 ± 11.5 d postpartum.

6Determined from 36 cows per treatment (6 cows per pen).

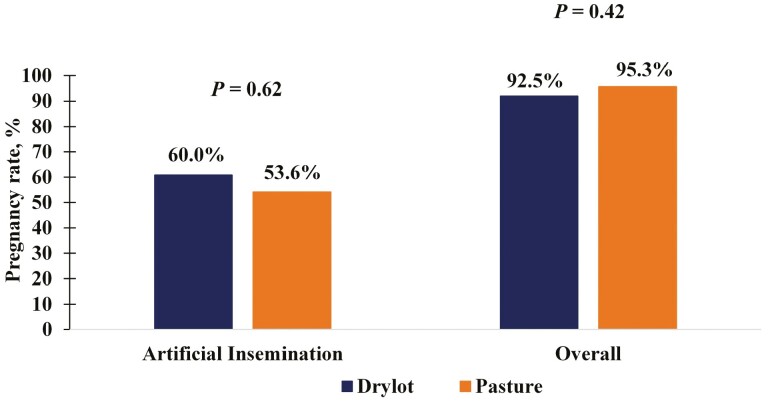

Reproductive performance

There were no differences (P = 0.62) for AI pregnancy rate (Figure 3) between DL (60.0%) and PAST (53.6%). Similarly, there were no differences (P = 0.42) for overall pregnancy rate between DL (92.5%) and PAST (95.3%).

Figure 3.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on cow artificial insemination and overall pregnancy rate. DL cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR, and PAST cows rotationally grazed pasture, calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning.

Locomotion, foot treatment, and foot scores

There were no differences (P = 0.33) in cow locomotion (Table 4) at the start of the trial (day 0). However, cows in the DL tended to have greater locomotion scores at midpoint (P = 0.07) of trial and at weaning (P = 0.06) compared with cows on PAST. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.13) in the percentage of DL and PAST cows treated at least once (36.0 vs. 4.4, respectively) or twice or more (7.4 vs. 0.8, respectively) for foot rot or digital dermatitis. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.18) in foot angle or claw set scores for cows between treatments at any time point except for PAST cows tending to have greater initial foot angle (P = 0.09) and lower claw set score (P = 0.09) at the midpoint. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.14) in foot angle or claw set scores for calves between treatments at the start of the study, at weaning, or at the end of the receiving phase.

Table 4.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on cow locomotion score, foot angle, claw set, and percent of cows treated for foot lameness as well as calf foot angle and claw set scores

| Item | Treatment1 | SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | PAST | |||

| Cow locomotion2 | ||||

| Initial3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| Mid4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| Weaning5 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Cow foot angle6 | ||||

| Initial | 5.9 | 6.2 | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| Mid | 6.3 | 6.1 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| Weaning | 6.4 | 6.4 | 0.25 | 0.97 |

| Cow claw set7 | ||||

| Initial | 5.7 | 5.7 | 0.13 | 0.69 |

| Mid | 6.0 | 5.9 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Weaning | 6.3 | 6.2 | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| Cows treated8,% | ||||

| 1 treatment | 36.0 | 4.4 | – | 0.13 |

| 2 or more treatments | 7.4 | 0.8 | – | 0.28 |

| Calf foot angle | ||||

| Initial | 4.5 | 4.4 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| Weaning | 5.1 | 5.2 | 0.11 | 0.56 |

| End of receiving9 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Calf claw set | ||||

| Initial | 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.06 | 0.76 |

| Weaning | 4.9 | 4.8 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| End of receiving | 5.2 | 5.1 | 0.07 | 0.33 |

1DL cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR, and PAST cows rotationally grazed pasture, calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning.

2Locomotion score (0 = normal; animal walks normally, 3 = severe lameness) as described from the Zinpro Step-Up Locomotion Scoring System).

3Evaluated at 81 ± 15.3 d postpartum.

4Evaluated at 115.9 ± 15.3 d postpartum.

5Evaluated at 191 ± 15.3 d postpartum.

6Angle scores (1 to 9, in which 1 = extremely straight pasterns and 9 = extremely shallow heel and long toe, as described by the American Angus Association).

7Claw scores (1 to 9, 1 to 9, in which 1 = extremely weak, open divergent claw set and 9 = extreme scissor claw and/or screw claw, as described by the American Angus Association).

8Percentage of cows treated for foot rot or digital dermatitis.

9Evaluated at 240 ± 15.3 d of age at the completion of the receiving phase.

Calf performance through weaning

There were no differences (P = 0.96) on day 0 for calf BW (Table 5). Calves on DL had greater BW (P < 0.01) at time of WSW and at weaning compared to calves on PAST. Calves on DL continued to have greater BW (P < 0.01) through the end of the fence-line wean compared to PAST calves. Calves on DL had greater (P < 0.01) preweaning ADG compared to calves on PAST (1.40 vs. 1.12 kg/d, respectively). In 2019, calves on DL had a DMI (Table 1) of 0.9 kg/d on TMR 1, 1.9 kg/d on TMR 2, and 3.1 kg/d on TMR 3. In 2020, calves on DL had a DMI of 0.9 kg/d on TMR 1, 2.7 kg/d on TMR 2, and 3.8 kg/d on TMR 3. Calves on PAST had an average creep DMI of 0.8 kg/d during week 14, 2.5 kg/d during week 15, and 3.4 kg/d during week 16. Calves on PAST tended (P = 0.10) to have greater DMI compared to calves in the DL during the 6-d fence-line wean period (5.2 vs. 4.7 kg/d, respectively).

Table 5.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on calf body weight (BW), average daily gain (ADG) during the preweaning phase, as well as calf dirty scores

| Item | Treatment1 | SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | PAST | |||

| BW, kg | ||||

| Initial2 | 134.1 | 134.0 | 3.68 | 0.96 |

| WSW3 | 192.8 | 177.8 | 2.15 | <0.01 |

| Weaning4 | 286.1 | 255.4 | 4.66 | <0.01 |

| End of fence-line5 | 289.0 | 251.7 | 5.43 | <0.01 |

| ADG, kg/d | ||||

| Preweaning ADG6 | 1.40 | 1.12 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| Calf dirty score7 | ||||

| Initial | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Weaning | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.11 | <0.01 |

| End of Receiving8 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

1DL cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR, and PAST cows rotationally grazed pasture, calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning.

281 ± 15.3 d of age.

3Weigh-suckle-weigh conducted at 135 ± 15.1 d of age.

4191 ± 15.3 d of age.

5197 ± 15.3 d of age.

6ADG calculated from initial to weaning; days 0–110.

7Determine by a 5-point scale 1 = no tag, clean hide and 5 = lumps of manure attached to the hide continuously on the underbelly and side of the animal from brisket to quarter; as described by Busby and Strohbehn (2008).

8Evaluated at 240 ± 15.3 d of age at the completion of the receiving phase.

Calf dirty score

Calves in the DL treatment tended (P = 0.09) to be dirtier (Table 5) at the beginning of the trial compared to PAST calves. Calves in the DL treatment were dirtier (P = 0.03) compared with calves in the PAST treatment at weaning. However, at the end of the receiving phase, calves in the PAST treatment were dirtier (P = 0.04) compared to DL calves.

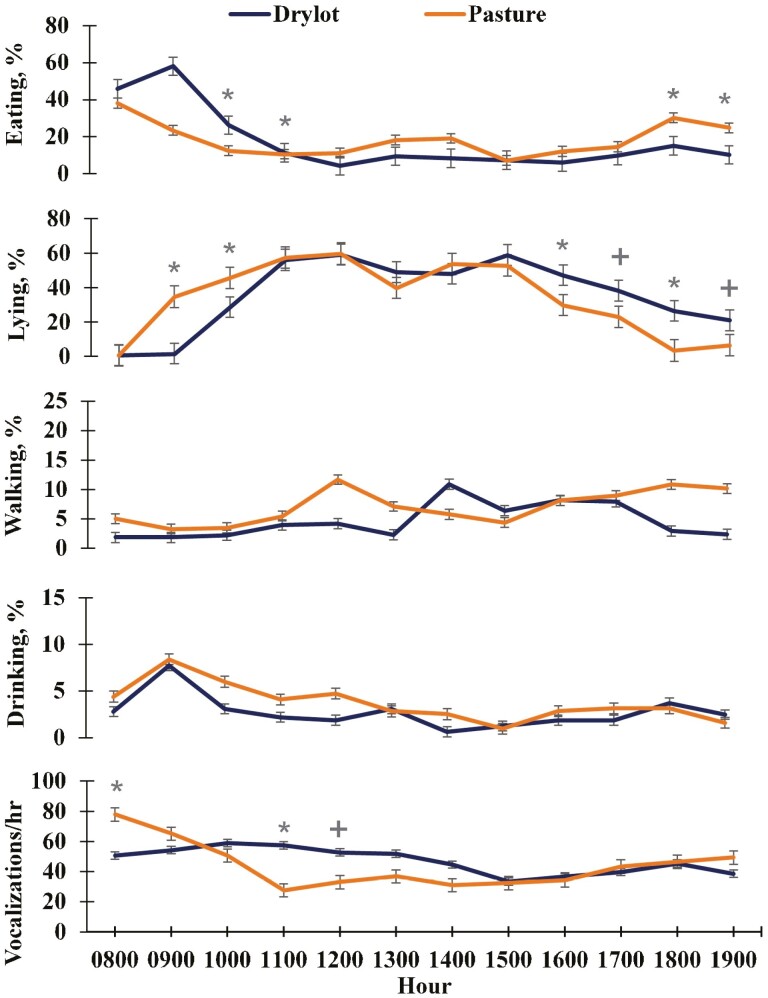

Weaning behavior observations

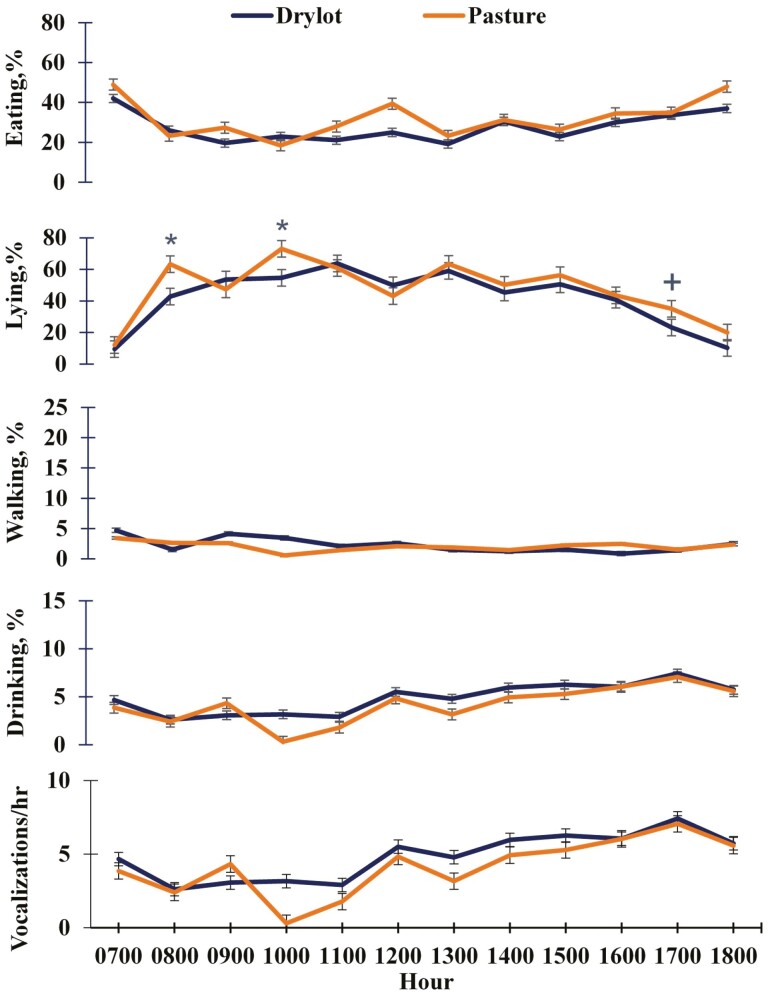

Behavior observations of eating, lying, walking, drinking, and vocalizations for day 111 are reported in Figure 4. On day 111, treatment × time effects were detected (P < 0.01) for eating, lying, and vocalizations. At hours 0900 and 1000 more (P ≤ 0.05) DL calves were eating. However, more (P ≤ 0.04) PAST calves were eating at hours 1800 and 1900. A greater proportion (P ≤ 0.04) of PAST calves were lying at hours 0900 and 1000. More (P ≤ 0.04) DL calves were lying at hours 1600 and 1800 and tended (P ≤ 0.08) to be at hours 1700 and 1900. The PAST calves vocalized more (P = 0.02) at hour 0800, whereas DL calves vocalized more (P < 0.01) at hour 1100 and tended (P = 0.08) to at hour 1200. There was a treatment effect detected on day 111 (P < 0.01) for more PAST calves to be walking compared to DL calves. There were no treatment effects detected for eating (P = 0.77), lying (P = 0.42), or vocalizations (P = 0.66). There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected (P ≥ 0.36) in drinking behavior.

Figure 4.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on calf behavior at weaning on day 111. Drylot cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR; pasture cows rotationally grazed pasture, and calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning. Significance of hour slice P-values is represented as P ≤ 0.05 defined by *, and tendencies from 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10 are defined as +. Vertical bars represent the SEM. There were treatment × time effects (P < 0.01) detected for eating, lying, and vocalizations. There was a treatment effect detected for walking (P < 0.01) but no treatment effects (P ≥ 0.42) for eating, lying, or vocalizations. There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected for drinking (P ≥ 0.36). There was a time effect detected (P ≤ 0.01) for each behavior.

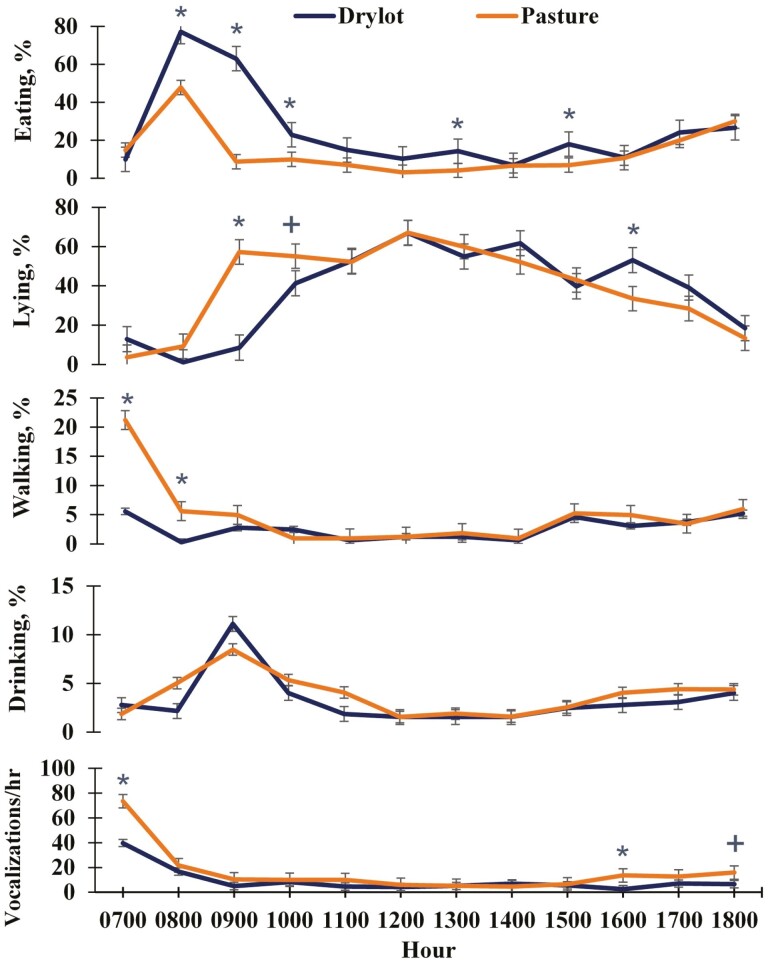

Behavior observations for day 112 are reported in Figure 5. There were treatment × time effects detected (P < 0.01) for eating, lying, walking, and vocalizations on day 112. More DL (P ≤ 0.04) calves were eating at hours 0800, 0900, 1000, 1300, and 1500 than PAST calves. More (P < 0.01) PAST calves were lying at hour 0900 and tended (P = 0.07) to be at hour 1000. However, more (P < 0.01) DL calves were lying at hour 1600. More (P ≤ 0.02) PAST calves were walking at hours 0700 and 0800. More (P ≤ 0.03) PAST calves vocalized at hours 0700 and 1600 and tended (P = 0.07) to be at hour 1800. There were treatment effects detected (P ≤ 0.03) for more PAST calves to be walking and vocalizing. There was also a treatment effect detected (P < 0.01) for more DL calves eating on day 112. There was no treatment effect detected for lying (P = 0.23). There were no treatment or treatment × time effects (P ≥ 0.32) detected in percent of calves drinking.

Figure 5.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on calf behavior at weaning on day 112. Drylot cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR; pasture cows rotationally grazed pasture, and calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning. Significance of hour slice P-values is represented as P ≤ 0.05 defined by *, and tendencies from 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10 are defined as +. Vertical bars represent the SEM. There were treatment × time effects detected (P ≤ 0.01) for eating, lying, walking, and vocalizations. There were treatment effects detected (P ≤ 0.03) for eating, walking, and vocalizations. There was no treatment effect detected for lying (P ≥ 0.23). There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected for drinking (P ≥ 0.32). There was a time effect detected (P ≤ 0.01) for each behavior.

Feedlot arrival behavior observations

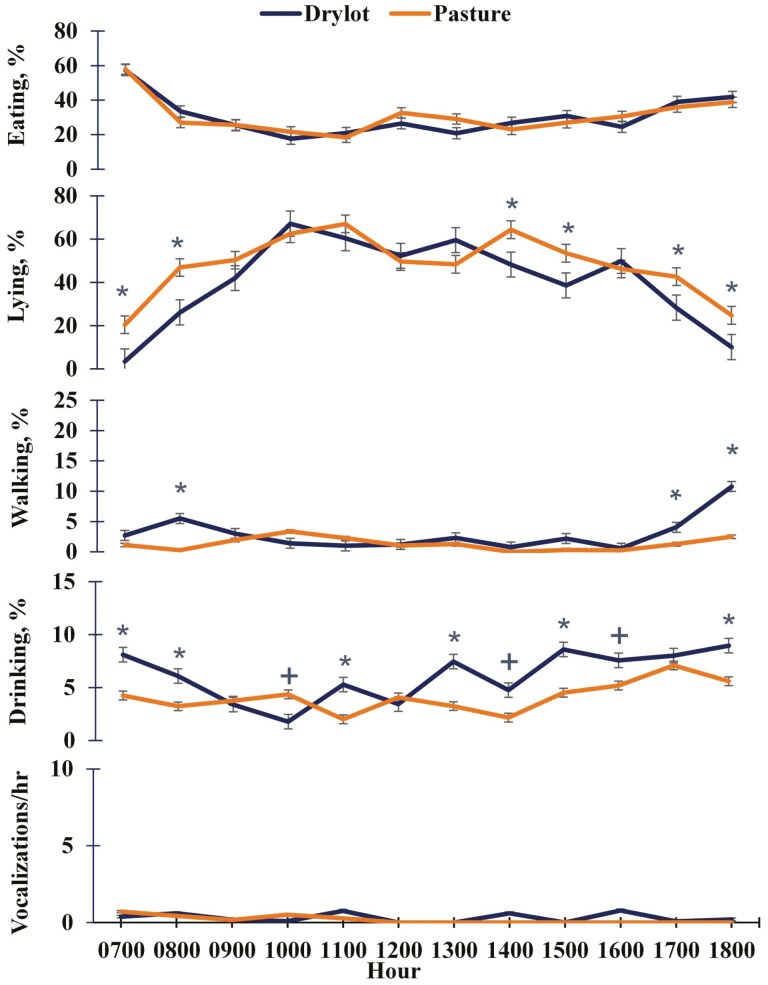

Behavior observations at feedlot arrival on day 117 are reported in Figure 6. Treatment × time effects were detected (P = 0.03) for lying on day 117. More (P < 0.01) PAST calves were lying at hours 0800 and 1000 and tended (P = 0.06) to be at hour 1700. There were also treatment effects (P ≤ 0.05) detected for lying and eating where more PAST calves were lying and eating on day 117. There was a treatment effect (P = 0.01) detected where DL calves vocalized more compared to PAST. There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected for walking (P ≥ 0.48) or drinking (P ≥ 0.12) on day 117.

Figure 6.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on calf behavior at receiving on day 117. Drylot cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR; pasture cows rotationally grazed pasture, and calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning. Significance of hour slice P-values is represented as P ≤ 0.05 defined by *, and tendencies from 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10 are defined as +. Vertical bars represent the SEM. There was a treatment × time effect detected (P = 0.03) for lying. There were treatment effects detected (P ≤ 0.05) for eating, lying and vocalizations. There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected for walking (P ≥ 0.48) or drinking (P ≥ 0.12). There was a time effect detected (P ≤ 0.10) for each behavior.

Behavior observations at feedlot arrival on d 118 are reported in Figure 7. There were treatment × time effects (P ≤ 0.02) detected for lying, walking, and drinking. More (P ≤ 0.05) PAST calves were lying at hours 0700, 0800, 1400, 1500, 1700, and 1800. Conversely, more DL calves were walking (P ≤ 0.05) at hours 0800, 1700, and 1800. More (P ≤ 0.05) DL calves were drinking at hours 0700, 0800, 1100, 1300, 1500, and 1800, and additionally tended (P ≤ 0.10) to be at hours 1400 and 1600. However, more PAST calves tended (P = 0.07) to be drinking at hour 1000. There were also treatment effects (P ≤ 0.01) detected for lying, drinking, and walking. More PAST calves were lying throughout the day, whereas more DL calves were walking and drinking. There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected for eating (P ≥ 0.69) or vocalizations (P ≥ 0.18) on day 118.

Figure 7.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on calf behavior at receiving on day 118. Drylot cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR; pasture cows rotationally grazed pasture, and calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning. Significance of hour slice P-values are represented as: P ≤ 0.05 defined by *, and tendencies from 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10 are defined as +. Vertical bars represent the SEM. There were treatment × time and treatment effects detected (P ≤ 0.02), for lying, walking and drinking. There were no treatment or treatment × time effects detected for eating (P ≥ 0.69) or vocalizations (P ≥ 0.17). There was a time effect detected for each behavior (P ≤ 0.01) besides vocalizations (P ≥ 0.12).

Receiving phase calf performance

The DL calves had greater BW (P < 0.01) upon arrival to the feedlot (Table 6). The DL calves had greater (P < 0.01) BW at the end of receiving. However, calves on PAST had a greater (P < 0.01) ADG during the 42-d receiving period. Overall, DMI during the 42-day receiving period was not different (P = 0.62). The PAST calves tended to have greater (P = 0.10) G:F during the receiving phase.

Table 6.

Influence of drylot housing or pasture on calf body weight (BW), average daily gain (ADG), dry matter intake (DMI), and gain:feed (G:F) during the receiving phase

| Item | Treatment1 | SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | PAST | |||

| BW, kg | ||||

| Beginning of receiving phase2 | 283.3 | 244.7 | 4.44 | <0.01 |

| End of receiving phase3 | 355.5 | 326.4 | 4.07 | <0.01 |

| ADG, kg/d | 1.72 | 1.95 | 0.05 | <0.01 |

| DMI, kg/d | 7.12 | 7.28 | 0.23 | 0.62 |

| G:F | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.011 | 0.10 |

1DL cow/calf pairs were housed on concrete lots with open front sheds, cows were limit-fed TMR formulated for maintenance and calves had ad libitum access to TMR; PAST cows rotationally grazed pasture, and calves offered creep feed 3 wk prior to weaning.

2198 ± 15.3 d of age.

3240 ± 15.3 d of age.

Discussion

The objective of this experiment was to determine the effects of housing cow–calf pairs in a drylot compared with pasture on cow performance and reproduction, in addition to calf performance and behavior at weaning and through the feedlot receiving phase. Cows housed in a DL maintained similar BW throughout the experiment and had greater BW and BCS at weaning compared to cows housed on PAST. However; both DL and PAST groups were in acceptable BCS at the end of the experiment (6.2 vs. 5.9, respectively). By design, the DL cows maintained BW throughout the experiment as they were fed rations formulated to meet maintenance requirements (NASEM, 2016), unlike PAST cows whose diets are less predictable and weather dependent. Similarly, summer calving cows had greater BCS and BW when maintained in a drylot from November to April compared with cows grazing cornstalks (Gardine et al., 2019). In contrast to the current study, lactating cows in a drylot from May to December weighed 18 kg of BW less than those grazing native grassland (Anderson et al., 2013). The authors explained that this weight difference was driven by the quality of the fall pastures compared to the lower quality hay cows on drylot were provided. An evaluation of different wintering systems indicated cows grazing stockpiled perennial forages gained more BW compared with those grazing crop residue or consuming grass legume hay in a drylot (Hitz and Russell, 1998). Similar to the current study, the authors reported that since cows in the drylot were fed at maintenance that would explain why BW did not change for the treatment. Cow–calf pairs maintained on pasture had improved BW compared to cows limit-fed in a drylot (Preedy et al., 2018). Although cows on both treatments lost BW in that study, cows on pasture had improved BW change (−33.7 kg) compared to drylot cows (−48.4 kg) from the beginning to the end of the grazing season. There were no differences in BW or BCS when cows were grazing stockpiled kochia-grass pastures compared to feeding harvested alfalfa hay in a drylot to maintain beef cows during the winter (Waldron et al., 2006).

In the current study, cows on PAST lost BW and BCS. The authors believe that this is likely related to the pasture quality as reported in Figure 1 and weather data as reported in Figure 2. Through June and July, NDF and ADF increased which decreased forage digestibility (NASEM, 2016) and resulted in lower calculated TDN values. As the plant matures in the later summer months, the digestibility decreased resulting in fewer nutrients available for the lactating cow. Additionally, crude protein decreased during those months. This decrease in pasture quality could partially be explained by the below-average rainfall in June. Pasture quality improvement in August is likely due to above-average rainfall in July (2019) and August (2020). Differences in BW and BCS between PAST and DL cows could also be partially explained by the activity increment that is increased when cattle are grazing (NASEM, 2016). Ultimately, cow performance in drylots with shelters depends primarily on the diet being fed and less on weather while stocking rates, forage quality, and weather determine performance on pasture. Forage availability fluctuated throughout the grazing season but was never limiting with lowest average forage availability observed in June at 2775.4 kg DM/ha.

Cows on PAST had greater HCS compared to cows on DL at weaning although the difference was minor (0.2 difference in HCS). Regardless, this suggests that cows on the DL treatment were able to shed better than PAST cows. Research has demonstrated that cows grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue can lead to rough hair coats (Porter and Thompson, 1992). Since PAST cows were grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue, this likely contributed to increased HCS.

Cows on DL had greater milk production than PAST cows (7.6 vs. 5.3 kg, respectively). Relative differences in plane of nutrition between treatments due to pasture quality may also explain this difference in milk production. It should also be noted that the weigh-suckle-weigh technique used for estimating milk production is not as repeatable as the milk machine method (Beal et al., 1990). There were no differences in milk composition besides an increase in MUN (4.8 vs. 13.9 mg/dL, respectively). Moderate MUN in dairy cattle is described as 13.5 mg/dL and high MUN as 18 mg/dL (Guo et al., 2004). Cows on PAST in this study had a 13.9 mg/dL which is still considered moderate. Elevated MUN is typically the result of excess CP (DePeters and Ferguson, 1992) or negative energy balance (Huhtanen et al., 2015). Since cows in this study were grazing pastures of relatively low to moderate CP, the elevated MUN in PAST cows is more likely a result of being in a negative energy balance.

Although PAST cows lost more BW than DL in the current study, there were no differences in reproductive performance between cows housed in drylots or pasture for AI pregnancy (60.0% vs. 53.6%, respectively) or overall pregnancy rate (92.5 vs. 95.3%, respectively). Treatments were initiated on day of AI so any differences in AI that were due to treatment would have to be the result of embryonic loss. It is important to note that both treatments were still in acceptable BCS throughout the experiment with both treatments at a BCS of ~6 at time of weaning. A BCS of 5–6 is recommended to ensure that cows are in adequate nutrition and have acceptable conception rates (Selk et al., 1988). Similarly, Anderson et al. (2013) observed no differences in overall conception rates for lactating cows housed in drylots or pasture when exposed to natural-service sires for a 45-d breeding season (84.2% vs. 85.2%, respectively). The authors also acknowledge that this experiment was not powered to detect small differences in reproductive performance.

The dairy industry has identified hoof health and locomotion as a primary management consideration when housing cattle in confined facilities (Adams et al., 2017). In the current study, cow locomotion scores tended to differ at the midpoint and at weaning where DL cows exhibited more lameness. On this locomotion scoring system, 0 is walking normally and 1 is walking with mild lameness where the animal does not exhibit a limp when walking. Therefore, even though the cows housed in a DL had an increased locomotion score compared with PAST cows (1.1 vs. 0.8, respectively) at weaning, they still had a mild lame-score. Although there were numerical differences in percentage of cows treated for foot rot or digital dermatitis, it was not significant. The authors also acknowledge that this experiment was not powered to detect differences in percentage of foot treatments given the large variation from pen to pen that occurred. There were no significant differences in foot angle or claw set detected during this experiment. It is unlikely that these foot scores would dramatically change during this short evaluation period. Previous environment could have also impacted cow locomotion and foot health, as cows and calves in both treatment groups were housed in the drylot pens during the winter months prior to the initiation of the study. Dairy cows housed in confinement with zero access to pasture had doubled the percentage of lame cows in comparison with cows given access to pasture (Haskell et al., 2006). Although culling for lameness in the beef industry is relatively low at 3% (USDA, 2010), lameness is one of the primary reasons for culling in confined dairy cows in the United States (Adams et al., 2017).

Similar to cows, calves housed in a DL had greater BW compared to calves raised on PAST. The DL calves had ad libitum access to the cow TMR ration for the duration of the preweaning period compared to calves on PAST given access to creep for only the final 3 wk prior to weaning. Creep feed was offered for the final 3 wk to help acclimate calves to processed feeds before weaning (Lardy and Maddock, 2007). Our objective was to compare different systems and utilize the most practical management options within each system. Similarly to our results, Preedy et al. (2018) found that calves that were both early and conventionally weaned and managed in confinement had greater BW than pasture calves weaned at either time point. Contrary to these findings, Burson (2017) studied the effects of cows calving on pasture, confinement, or sandhills systems on the health and performance of calves through weaning. Calves on pasture treatment had greater BW and ADG compared to calves raised in confinement. In this study, however, calves in confinement were fed creep 30 d into the calving season at a target of 1% of BW as-fed intake and calves on pasture did not have access to creep. Anderson et al. (2013) reported that pasture calves gained more weight when turned out on grass with their dam compared to drylot calves who were supplemented with a TMR. In that study, both groups were given access to a 16% creep during the preweaning phase, drylot groups were weaned in late September, whereas pasture calves were weaned in late October which could explain some of the differences in BW. In the current study, differences in cow milk production also likely contributed to differences in calf BW at the time of weaning as DL cows produced more milk than PAST cows.

Calves in the DL had greater DS at weaning; yet, PAST calves had greater DS at the end of receiving. The drylot conditions could explain DL calves having a greater DS at weaning. Although pens were bedded as needed, the precipitation caused the pens to be damp. Considering PAST cows had greater HCS, the PAST calves may have also had greater HCS which would allow tag to attach to the hide easier during the receiving phase. Although a statistical difference was observed, both treatments were still considered a clean score.

The authors hypothesized that calves raised in a drylot would show less behavioral signs of stress at weaning since their environment had not changed and they were more acclimated to the feed bunk. On day 111, more DL calves were eating in the earlier hours of the day, whereas more PAST calves were eating creep or hay in the later hours of the day. This is likely due to the DL calves being more accustomed to the feed bunk and morning delivery of the TMR. More PAST calves were lying in the early hours on day 111 compared to DL calves. This may be linked to the calves on DL eating at those hours. More PAST calves were walking on day 111 compared to DL calves. This is likely due to PAST calves entering a new environment and when cattle are adapting to a new environment they often walk the perimeter and were likely seeking their dam.

Additionally, on day 111, PAST calves vocalized more at hour 0800 and DL calves vocalized more at hour 1100 and tended to at hour 1200. The authors speculate that PAST calves were bawling for their dam early in the morning, whereas DL calves were eating at that hour. Conversely, the DL calves were not vocal until the later part of the morning after they were done eating. The frequency of vocalizations emitted by the calf is perhaps the most important behavior indicative of stress (Enríquez et al., 2011). The high frequency of vocalizations may indicate the animal’s state of frustration for being unable to receive its previous feed, care, or bond with the dam (Enríquez et al., 2011). Although calves in this study were both fence-line weaned, the PAST calves experienced a new environment which could explain the increase in vocalizations. Haley et al. (2005) reported that abrupt-weaned calves averaged 41.9 vocalizations which was approximately 30 times greater than calves weaned in two-stages. Similarly, Rauch et al. (2018) reported that calves weaned in two-steps also vocalized less 2 d post-weaning compared to abrupt-weaned calves.

On day 112, behavior observations were similar to the previous day. More DL calves were eating throughout the day compared to calves on PAST, especially in the morning hours. There were differences in lying behavior throughout the day where more PAST calves were lying in the morning hours. More PAST calves were walking in the morning and vocalized more before feed was delivered.

Interestingly, there was a difference in intake during the fence-line wean. The authors had hypothesized that calves on DL would eat more since they had remained in their original environment and were acclimated to the feed bunk; yet, PAST calves tended to have greater DMI. This is surprising when considering more DL calves were eating during behavior observations on day 112. The authors hypothesize that this could be due to PAST calves compensating for their dams’ decreased milk production by increasing forage intake prior to weaning. Additionally, calves on PAST had ad libitum access to creep and hay, whereas DL calves only had access to the TMR. The authors acknowledge that differences in diet type and palatability could have contributed to differences in DMI. However, our objective was to minimize diet changes within treatment at time of weaning that could have added additional stress and potentially altered behavior.

Upon arrival to the feedlot, more PAST calves were lying at hours 0800, 1000, and 1700. Additionally, more PAST calves were eating and PAST calves vocalized less than DL calves on day 117. Surprisingly, the DL calves showed more behavioral signs of stress upon feedlot arrival compared to PAST calves. The authors hypothesized that DL calves would be better adapted to a feedlot setting since it was similar to their preweaning environment. The authors speculate that this may be explained by this is the first time DL calves moved to a new environment, even though it was similar. They also had been accustomed to being in close proximity with their dam, whereas PAST calves had already had to adjust to a new environment. It is documented that the breaking of the bond between cow and calf is more indicative of the behavior of the calves than the loss of access to milk (Wiese et al., 2016). Stěhulová et al. (2017) reported that calves who weaned with greater ADG vocalized more than calves with poorer gains. In this study, DL calves weaned with greater ADG and also vocalized more than PAST calves upon feedlot arrival on day 117.

There were similar behavior observations on day 118 as on day 117. There were differences in the percentage of calves lying, drinking, and walking from either treatment at different parts of the day. More DL calves were drinking and walking whereas more PAST calves were lying. There were very few vocalizations from either treatment and no differences in eating. Price et al. (2003) and Rauch et al. (2018) also found commonalities in behaviors between days when observing calf behavior for two or more consecutive days.

Calves on the DL treatment had greater BW at weaning; thus, the authors were not surprised that they had greater BW throughout the receiving phase. The authors had hypothesized that DMI would be lower for calves raised on pasture as Fluharty and Loerch (1996) had found that newly arrived calves at the feedlot initially prefer diets that are similar in moisture and texture to feeds that they are familiar with. Calves on PAST had been adapted to a forage diet with pelleted creep supplement, whereas DL calves were fed a TMR with similar ingredients. The PAST calves had improved G:F and ADG during the overall receiving period. The authors speculate that since the PAST calves were on a lower plane of nutrition preweaning, that they compensated when put on a higher energy diet during the receiving period. It is important to note that even though PAST calves experienced compensatory gain they still did not achieve similar BW as DL calves by the end of the receiving period. Similarly, Mathis et al. (2009) found that calves managed on pasture weaned lighter than calves weaned in a drylot but gained more BW during the first 75 d of finishing compared to drylot calves. However, Bailey et al. (2016) evaluated the effects of fence-line or drylot weaning on the performance of calves during weaning, receiving, and finishing and found that ADG was greater for drylot calves than either pasture treatment during the 28-d weaning period when fed a diet to promote ADG of 1 kg at a DMI of 2.5% of BW. In contrast to the current study, however, DMI and G:F were greater for drylot calves than either pasture treatment during the 56-d receiving phase. Conversely, Boyles et al (2007) compared calves that were weaned at trucking, weaned 30 d before trucking and confined in a drylot, or weaned 30 d before trucking and pastured with fence-line wean contact with their dam. Steers from the drylot treatment lost 0.6 kg/d in the first week in the feedlot receiving, whereas steers who were weaned at trucking gained 0.5 kg/d and those that were pasture-weaned gained 0.4 kg/d. Although BW gain in the subsequent 3 wk was similar among treatments, the differences in the first week upon arrival were enough to impact overall gain during the receiving period. Calves weaned on pasture or on the truck had increased gains compared to calves weaned in the drylot at the end of the receiving period. Multiple management and nutritional factors contribute to differences and variability in housing systems effects on calf performance.

Conclusions

In summary, with decreased land availability and natural resources in the Midwest and challenges with grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue, many producers are seeking alternative options for housing cow–calf pairs during the summer months. Housing cow–calf pairs in drylots resulted in increased BW, BCS, and milk production compared to cows on pasture but did not affect reproduction. Housing cow–calf pairs in drylots did, however, tend to increase lameness. Calves raised in a drylot had greater BW and ADG during the preweaning stage and maintained the BW advantage through the 42-d receiving phase. Calves raised in PAST had greater G:F and ADG during the 42-d receiving phase did not compensate enough to achieve similar weights at end of the receiving period as DL calves. There were differences in behavioral stress for calves at weaning amongst both treatments. Drylot systems utilizing readily available alternative feedstuffs are a viable alternative to grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue pastures for Midwest producers. Drylot systems offer more predictable cow performance as the impacts of weather on forage quality are removed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Iowa Beef Industry Council for funding for this project and the staff at the University of Illinois Orr Agricultural and Demonstration Center, Baylis, IL for care of the experimental animals and aiding in collection of data. We thank the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture for providing the Illinois Beef Experiential Learning and Industry Exposure Fellowship (I-BELIEF) supported by Literacy Initiative grant 2018-67032-27709 which provided support for the undergraduate students.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADF

acid detergent fiber

- ADG

average daily gain

- BCS

body condition score

- BW

body weight

- CP

crude protein

- DDGS

dried distillers grains with solubles

- DL

drylot

- DM

dry matter

- DMI

dry matter intake

- DS

dirty score

- G:F

gain:feed

- HCS

hair coat score

- NDF

neutral detergent fiber

- OM

organic matter

- MUN

milk urea nitrogen

- MWDGS

modified wet distillers grains with solubles

- PAST

pasture

- WSW

weigh-suckle-weigh

- TMR

total mixed ration

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Adams, A. E., Lombard J. E., Fossler C. P., Román-Muñiz I. N., and Kopral C. A.. . 2017. Associations between housing and management practices and the prevalence of lameness, hock lesions, and thin cows on US dairy operations. J. Dairy Sci. 100:2119–2136. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, V., Ilse B., and Engel C.. . 2013. Drylot vs. pasture beef cow/calf production – 3-year progress report. 2013 Carrington Research Extension Center Field Day. North Dakota State University. Online summary found at: https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/CarringtonREC/documents/video-handouts/2013/field-day/drylot-vs-pasture-handout/view—[accessed February 17, 2021].

- Bailey, E. A., Jaeger J. R., Waggoner J. W., Preedy G. W., Pacheco L. A., Olson K. C.. . 2016. Effect of fence-line or drylot weaning on the health and performance of beef calves during weaning, receiving, and finishing. Prof. Anim. Sci. 32:220–228. doi: 10.15232/pas.2015-01456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, B. C., Watson C. A., and Baddeley J. A.. . 2007. Soil physical fertility, soil structure and rooting conditions after ploughing organically managed grass/clover swards. Soil Use Manag. 23:20–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-2743.2006.00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beal, W. E., Notter D. R., and Akers R. M.. . 1990. Techniques for estimation of milk yield in beef cows and relationships of milk yield to calf weight gain and postpartum reproduction. J. Anim. Sci. 68:937–943. doi: 10.2527/1990.684937x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyles, S. L., Loerch S. C., and Lowe G. D.. . 2007. Effects of weaning management strategies and health of calves during feedlot receiving. Prof. Anim. Sci. 23:637–641. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)31034-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burson, W. C., 2017. Confined versus conventional cow-calf management systems: Implications for calf health. Ph.D. dissertation, Lubbock (TX):Texas Tech University. [Google Scholar]

- Busby, D. W., and Strohbehn D. R.. . 2008. Evaluation of mud scores on finished beef steers dressing percent. Iowa State University Animal Industry Report. 5(1). doi: 10.31274/ans_air-180814-426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clements, A. R., Ireland F. A., Freitas T., Tucker H., and Shike D. W.. . 2017. Effects of supplementing methionine hydroxy analog on beef cow performance, milk production, reproduction, and preweaning calf performance. J. Anim. Sci. 95:5597–5605. doi: 10.2527/jas2017.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemson University Agricultural Service Laboratory. 1996. Formulas for feed and forage analysis calculations—(retrieved November 13, 2015) Available from http://www.clemson.edu/agsrvlb/Feed%20formulas.txt.

- DePeters, E. J., and Ferguson J. D.. . 1992. Nonprotein nitrogen and protein distribution in the milk of cows. J. Dairy Sci. 75:3192–3209. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)78085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enríquez, D., Hötzel M. J., and Ungerfeld R.. . 2011. Minimising the stress of weaning of beef calves: a review. Acta Vet. Scand. 53:28. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-53-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FASS. 2020. Guide for the care and use of agricultural animals in agricultural research and teaching. Consortium for Developing a Guide for the Care and Use of Agricultural Research and Teaching. Champaign (IL):Association Headquarters. [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty, F. L., and Loerch S. C.. . 1996. Effects of dietary energy source and level on performance of newly arrived feedlot calves. J. Anim. Sci. 74:504–513. doi: 10.2527/1996.743504x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardine, S. E., Warner J. M., Bondurant R. G., Hilscher F. H., Rasby R. J., Klopfenstein T. J., Watson A. K., Jenkins K. H.. . 2019. Performance of cows and summer born calves and economics in semi-confined and confined beef systems. Prof. Anim. Sci. 35:521–529. doi: 10.15232/aas.2019-01858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gay N., Boling J. A., and Dew R.. . 1988. Effects of endophyte-infected tall fescue on beef cow-calf performance. Appl. Agric. Res. 3:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Grussing, T. M., Grussing T. C., and Gunn P. J.. . 2016. Effect of GnRH removal at CIDR insertionin the 5 d CO-Synch + CIDR ovulation synchonization protocol on ovarian function in beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 94:511. doi: 10.2527/jam2016-1066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, P. J., Sellers J., Clark C., and Schulz L.. . 2014. Considerations for managing beef cows in confinement. Driftless Region Beef Conference. Iowa State University. January 30-31, 2014. 30–32. Online summary found at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=driftlessconference#:~:text=Cows%20and%20calves%20in%20confinement,for%20those%20conditions%20as%20well—[accessed December 12, 2020].

- Guo, K., Russek-Cohen E., Varner M. A., and Kohn R. A.. . 2004. Effects of milk urea nitrogen and other factors on the probability of conception of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87:1878–1885. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley, D. D., and Bailey J. S.. . 2005. The effects of weaning beef calves in two stages on their behavior and growth rate. J. Anim. Sci. 83:2205–2214. doi: 10.2527/2005.8392205x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, M. J., Rennie L. J., Bowell V. A., Bell M. J., and Lawrence A. B.. . 2006. Housing system, milk production, and zero-grazing effects on lameness and leg injury in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 89:4259–4266. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitz, A. C., and Russel J. R.. . 1998. Potential of stockpiled perrenial forages in winter grazing systems for pregnant beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 76:404–415. doi: 10.2527/1998.762404x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtanen, P., Cabezas-Garcia E. H., Krizan S. J., and Shingfield K. J.. . 2015. Evaluation of between-cow variation in milk urea and rumen ammonia nitrogen concentrations and the association with nitrogen utilization and diet digestibility in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 98:3182–3196. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, K. H., Furman S. A., Hansen J. A., Klopfenstein T. J.. . 2015. Limit feeding high-energy, by-product-based diets to late-gestation beef cows in confinement. Prof. Anim. Sci. 31:109–113. Doi: 10.15232/pas.2014-01357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lardy, G. P., and Maddock T. D.. . 2007. Creep feeding nursing beef calves. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 23:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardy, G. P., Anderson V. L., Boyles S. L., and Specialist B. E.. . 2017. Drylot beef cow-calf production. North Dakota Agriculture Experiment Station. Fargo, North Dakota: Extension Publication AS974. [Google Scholar]

- Loerch, S. C. 1996. Limit-feeding corn as an alternative to hay for gestating beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 51: 432–438. doi: 10.2527/1996.7461211x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, C. P., Cox S. H., Loest C. A., Petersen M. K., Endecott R. L., Encinias A. M., and Wenzel J. C.. . 2009. Comparison of low-input pasture to high-input drylot backgrounding on performance and profitability of beef calves through harvest. Prof. Anim. Sci. 24:169–174. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30832-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. J., Faulkner D. B., Cunningham T. C., and Dahlquist J. M.. . 2007. Restricting time of access to large round bales of hay affects hay waste and cow performance. Prof. Anim. Sci. 23:366–372. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30990-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. 8th ed. Washington, DC:National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, J. K., and F. N.Thompson, Jr. 1992. Effects of fescue toxicosis on reproduction in livestock. J. Anim. Sci. 70:1594–1603. doi: 10.2527/1992.7051594x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preedy, G. W., Jaeger J. R., Waggoner J. W., Olson K. C., and Harmoney K. R.. . 2018. Effects of early or conventional weaning on beef cow and calf performance in pasture and drylot environments. Kansas Agric. Exp. Stat. Res. Rep. 4. doi: 10.4148/2378-5977.7554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, E. O., Harris J. E., Borgward R. E., Sween M. L., and Connor J. M.. . 2003. Fenceline contact of beef calves with their dams at weaning reduces the negative effects of separation on behavior and growth rate. J. Anim. Sci. 81:116–121. doi: 10.2527/2003.811116x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, J. C., Stokes R. S., and Shike D. W.. . 2018. Evaluation of two-stage weaning and trace mineral injection on receiving cattle growth performance and behavior. Transl. Anim. Sci. 3:155–163. doi: 10.1093/tas/txy131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selk, G. E., Wettemann R. P., Lusby K. S., Oltjen J. W., Mobley S. L., Rasby R. J., and Garmendia J. C.. . 1988. Relationship among weight change, body condition, and reproductive performance of range beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 66:3153–3159. doi: 10.2527/jas1988.66123153x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shike, D. W., Faulkner D. B., Parrett D. F., and Sexten W. J.. . 2009. Influences of corn co-products in limit-fed rations on cow performance, lactation, nutrient output, and subsequent reproduction. Prof. Anim. Sci. 25:132–138. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30699-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stěhulová, I., Valníčková B., Šárová R., and Špinka M.. . 2017. Weaning reactions in beef cattle are adaptively adjusted to the state of the cow and the calf. J. Anim. Sci. 95:1023–1029. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. W., and Durham R. M.. . 1964. Drylot all-concentrate feeding: an approach to flexible ranching. J. Range Manag. 17:179. doi: 10.2307/3895761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- USDA. 2010. Beef 2007–08, Part IV: Reference of beef cow-calf management practices in the United States, 2007–08. Fort Collins, CO: USDA:APHIS:VS, CEAH. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, B. L., ZoBell D. R., Olson K. C., Jensen K. B., and Snyder D. L.. . 2006. Stockpiled forage kochia to maintain beef cows during winter. Rangel Ecol Manag. 59:275–284. doi: 10.2111/05-121R1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, R. H., McCann M. A., Parish J. A., Hoveland C. S., Thompson F. N., and Bouton J. H.. . 2004. Productivity of cow–calf pairs grazing tall fescue pastures infected with either the wild-type endophyte or a nonergot alkaloid-producing endophyte strain, AR542. J. Anim. Sci. 82:3388–3393. doi: 10.2527/2004.82113388x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, B. I., Hendrick S., Stookey J. M., Schwartzkopf-Genswein K. S., Li S., Plaizier J. C., and Penner G. B.. . 2016. The effect of weaning regimen on behavioral and production responses of beef calves. Prof. Anim. Sci. 32:229–235. doi: 10.15232/pas.2015-01447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T. B., Long N. M., Faulkner D. B., and Shike D. W.. . 2016. Influence of excessive dietary protein intake during late gestation on drylot beef cow performance and progeny growth, carcass characteristics, and plasma glucose and insulin concentrations. J. Anim. Sci. 94:2035–2046. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinpro Coorporation in conjunction with Kansas State University and the Beef Cattle Institute. 2013. Zinpro Corp. B-5057. Available from https://www.zinpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/StepUpBeefCattleLocomotionScoring.pdf —[last accessed December 14, 2021]. [Google Scholar]