Abstract

Purpose:

This study aims to develop and validate a parametric response mapping (PRM) methodology to accurately identify diseased regions of the lung by using variable thresholds to account for alterations in regional lung function between the gravitationally-independent (anterior) and gravitationally-dependent (posterior) lung in CT images acquired in the supine position.

Methods:

34 male Sprague-Dawley rats (260–540 g) were imaged, 4 of which received elastase injection (100 units/kg) as a model for emphysema (EMPH). Gated volumetric CT was performed at end-inspiration (EI) and end-expiration (EE) on separate groups of free-breathing (n = 20) and ventilated (n = 10) rats in the supine position. To derive variable thresholds for the new PRM methodology, voxels were first grouped into 100 bins based on the fractional distance along the anterior-to-posterior direction. Lower limits of normal (LLN) for x-ray attenuation in each bin were set by determining the smallest region that enclosed 98% of voxels from healthy, ventilated animals.

Results:

When utilizing fixed thresholds in the conventional PRM methodology, a distinct posterior-anterior gradient was seen, in which nearly the entire posterior region of the lung was identified as HEALTHY, while the anterior lung was labeled as significantly less so (t(29) = −3.27, p = 0.003). In both cohorts, %SAD progressively increased from posterior to anterior, while %HEALTHY lung decreased in the same direction. After applying our PRM methodology with variable thresholds to the same rat images, the posterior-anterior trend in %SAD quantification was removed from all rats and the significant increase of diseased lung in the anterior was removed.

Conclusions:

The PRM methodology using variable thresholds provides regionally specific markers of %SAD and %EMPH by correcting for alterations in regional lung function associated with the naturally occurring vertical gradient of dependent vs. non-dependent lung density and compliance.

Keywords: PRM, Lung CT, Volumetric Lung CT, Variable Thresholds

Introduction

The lung is a dynamic and heterogeneous structure, in which the constituent components of tissue, blood and air respond to gravity1, pleural pressure, body positioning2 and the breathing cycle. The physiological response to gravity can be summarized in terms of dependent (gravitationally lower) and non-dependent (higher) regions. Dependent regions of the lung experience an increase in blood flow and ventilation during the breathing cycle, coupled with overall higher tissue density and smaller alveolar size. This gradient is particularly pronounced at lower lung inflation levels1,3,4.

Because differences in tissue density form the basis of x-ray absorption contrast, the gravitational response is easily detected on computed tomography (CT) images, which are known to be significantly influenced by gravity and body position2,5–7. Unfortunately, this introduces the potential for imprecise CT quantification, because changes in x-ray absorption also underlie methods to detect and quantify tissue destruction associated with emphysema and air trapping caused by small airways disease8. For example, Parametric Response Mapping (PRM)9–12 uses co-registered paired end-inspiratory (EI) and end-expiratory (EE) volumetric CT images to classify voxels in terms of both the local x-ray attenuation (Hounsfeld Unit, or HU) and the attenuation change during the breathing cycle using a fixed set of thresholds that has been largely accepted for application to human lung images13–15: regions of lung parenchyma with HU < −856 at EE and HU > −950 at EI are labeled as non-emphysematous air trapping, while those with HU <−856 at EE and HU <−950 at EI are classified as emphysematous tissue remodeling. Non-emphysematous air trapping has been closely associated with the presence of small airways disease (SAD)13.

The utility of PRM analysis in following the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) is now well established9,16,17, leading to its incorporation into the newly proposed diagnostic criteria for COPD18. However, in light of known physiological responses, it stands to reason that classification of individual regions will be affected by their location along the gravitational axis, lung volume at image acquisition, and by the supine subject position typical of imaging studies. Clinical interventions that rely on local information, such as lung volume reduction surgery or endobronchial valve placement, may thus be affected by this potential misclassification as well.

In this work, we take the first steps toward a more flexible thresholding and classification scheme by measuring and accounting for gravitational effects in an animal model. In analyzing micro-CT images obtained from free-breathing or ventilated rats, we employed a new methodology that maintains the conventional PRM description but applies different thresholds at each position in the anterior-posterior direction. We then tested the method to verify that the effect of animal weight is insufficient to require additional correction, and applied the modified scheme to animals with elastase-induced lung injury to verify model sensitivity. Finally, the thresholds selected for the free-breathing and ventilated rats, respectively, were applied to images from the opposite cohort in order to determine the extent to which lung volume influences PRM quantification.

Methods & Materials

Animal Studies

All studies performed were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. Imaging was performed on 30 Sprague-Dawley rats (260–540g) after anesthetization using a combination of oxygen and isoflurane at approximately 2%. Whole-body volumetric EE and EI respiratory gated CT scans were performed in the supine position during the anesthetized rats’ normal tidal breathing (20 rats) or during mechanical ventilation (10 rats) using a commercial microCT scanner (eXplore CT120 system, Trifoil Imaging, Inc., Chatsworth, CA). A single view was acquired at each inhalation and exhalation. Ventilation imaging was ventilator-gated and performed during 5-ms breath-holds at end inspiration (EI) and end-expiration (EE) with a setting of PEEP 0 cm H2O, TV of 10 mL/kg and BR of 50/min (350ms inhale, 800ms exhale). PIP was typically 26–28 cmH2O, indicating that EI images were acquired at near TLC. Under free-breathing conditions, EI images were acquired at tidal volume (TV) + functional residual capacity (FRC), while EE corresponded to FRC. Before the start of acquisition, animals were subject to PEEP=8cmH2O for 2 minutes to minimize atelectasis due to posture and anesthesia during imaging. Heart-rate and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored during imaging via pulse oximetry, and imaging did not begin until rats were breathing at approximately 50 breaths per minute. The image acquisition settings used were: 80 kVp, 32 mA, 16 mS exposure time, 220 projections (half-scan), and reconstruction to 200 μm isotropic resolution. For both breathing schemes, a single view was acquired during each breath, resulting in a total imaging time of approximately 12 minutes per animal.

Disease Model

Emphysema was induced in 4 male Sprague-Dawley rat (300–350g) via localized elastase injection (100 units/kg) into the lungs. In order to allow time for the disease to develop and progress, elastase injection occurred approximately one month prior to imaging. Diseased animals were imaged once in the same manner as described above, with 2 rats undergoing CT while free-breathing and 2 with mechanical ventilation.

Image Analysis and Conventional Parametric Response Mapping

Lung boundary and full airway segmentations for paired EI and EE volumetric CT images were performed semi-automatically using the ITK-snap Image Analysis Toolbox 19. The conducting airways were removed from all lung images after segmentation. EI images were then co-registered (aligned) to EE images using an anatomical feature matching algorithm that accounts for distortion of the thoracic cavity during tidal breathing20,21. Co-registered EI and EE images were subsequently used to generate PRMs of the rat lungs using a custom Matlab code following a similar methodology to that previously presented by Galban et al.10. In analogy with the appropriate human thresholds of %emph at < −950 EI and %fSAD at < −856 EE, we chose fixed threshold values of < −716 EI and < −580 EE to distinguish between healthy and diseased regions of the free-breathing rat lung, while values of < −869 EI and < −686 EE were chosen for the ventilated rats. These values were chosen such that the rectangular region designated as ‘healthy’ in the EE/EI plane enclosed the smallest area possible while containing 98% of voxels from healthy animals. Paired EE and EI images were next divided into 3 isotropic regions of interest (ROIs) representing the anterior, middle, and posterior thirds of the lung. After quantification, paired two sample t-tests were used to compare the %SAD in posterior vs. anterior regions.

PRM Correction Methodology

To derive variable threshold values appropriate for each position along the gravitational axis, EI and EE voxels from all 30 healthy rats were plotted individually and grouped into 100 bins based on the voxel’s fractional distance above the dorsal edge of the lung segmentation mask, where bin 1 was the posteriormost lung and bin 100 was the anteriormost lung. A small amount of variability was observed in mean lung tissue EE and EI HU values among free-breathing (−349 +/−39 and 455 +/−55 HU, respectively) and ventilated animals (−445 +/− 54 and −634 +/− 35 HU, respectively). Because a similar variability was observed in both extrapulmonary tissue and air outside the body, we attributed the variability to scanner or reconstruction artifacts. Thresholds corresponding to lower limits of normal (LLN) for each bin were then set to contain 98% of the bin’s voxels, as when deriving the fixed thresholds. Because all rats used for this analysis were healthy, the x-axis and y-axis minimums generated from this analysis were considered to be the LLNs for healthy lung tissue for each bin.

After calculating variable EE and EI thresholds for each bin in all rats, diseased regions were classified as SAD or EMPH using a similar criterion to that previously described by Galban et al. Understanding that the EELLN and EILLN thresholds depend on the voxel’s position in the anterior-posterior direction, voxels with EIvoxel ≥ EILLN and EEvoxel ≤ EELLN were classified as SAD, while voxels with both EEvoxel and EIvoxel ≥ EE/EILLN were classified as EMPH. Remaining voxels with EIvoxel and EEvoxel ≤ EE/EILLN were classified as healthy.

Results

Defining the Gravitational Gradient on Conventional PRM

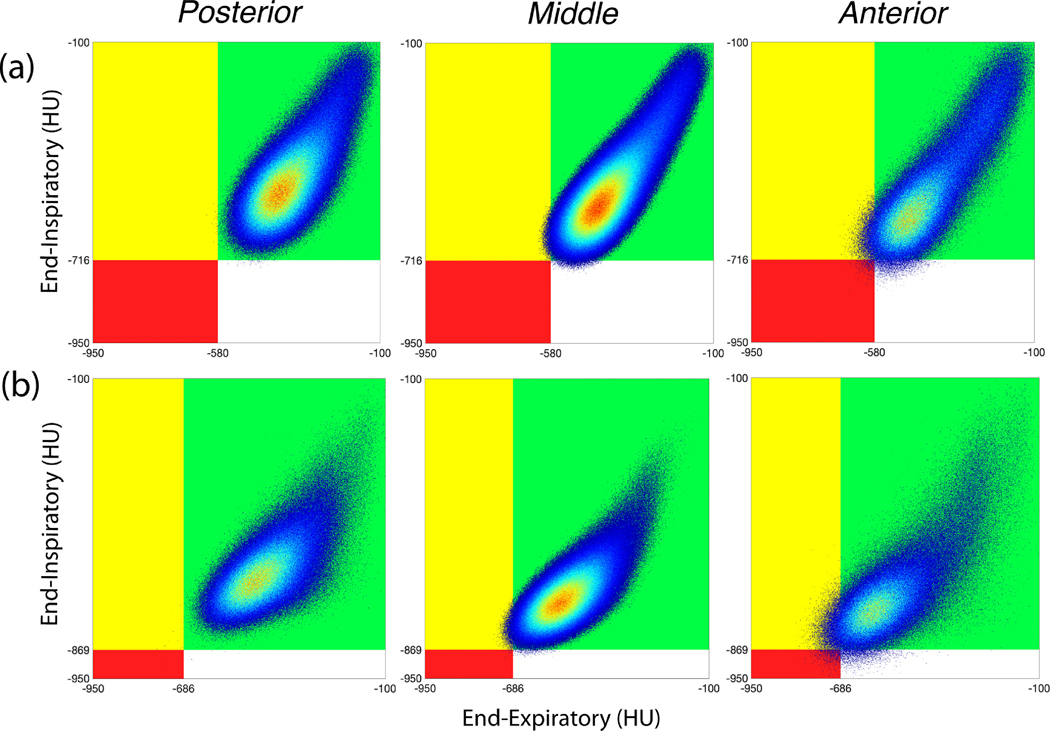

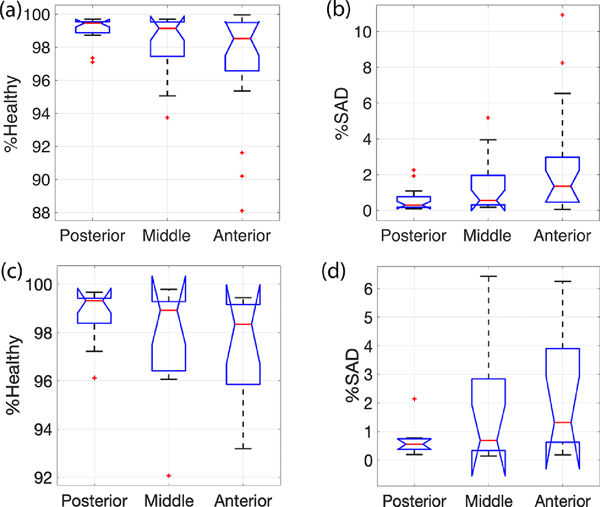

Analysis of images from all free-breathing and ventilated rats revealed a distinct anterior-to-posterior gradient within the lungs. To assess this gradient, conventional PRM methodology with fixed thresholds was applied to EE and EI voxel distributions from the anterior, middle, and posterior lung of all healthy free-breathing and ventilated rats. Figures 1a and b show that the vast majority of voxels classified as SAD (yellow region) are located in the anterior lung, while the amount classified as SAD progressively decreases from anterior (right) to posterior (left) slices, until the posterior portion of the lung is classified as entirely healthy. Although the fixed thresholds utilized in free-breathing vs. ventilated PRMs differ, the anterior-posterior disease quantification trend remains. This same trend can be observed in the box and whisker plots of Figures 2a and b, where the %SAD calculated by conventional PRM progressively increases from the posterior (left) (average %SAD free-breathing = 0.501%, average %SAD ventilated = 0.227%) to anterior lung (right) (average %SAD free-breathing = 2.76%, average %SAD ventilated = 4.09% ) in all rats. A paired two sample t-test showed a significant difference between the %SAD quantification in anterior vs. posterior lung when using the fixed thresholds (t(29) = −3.27, p = 0.003).

Figure 1:

Overall PRM distributions generated using conventional PRM methodology on paired EE and EI volumetric CT images acquired from healthy free-breathing rats (a) and healthy ventilated rats (b). Voxels in the green region are classified as HEALTHY, while those in the yellow and red regions are classified as SAD and EMPH, respectively. Note that the threshold values on the PRM are different for free-breathing compared to ventilated rats.

Figure 2:

Box and whisker plots of (a,c) %HEALTHY and (b,d) %SAD calculated in 20 healthy, free-breathing rats (a,b) and 10 ventilated rats (c,d) using conventional PRM methodology with a fixed threshold, representing the progressive decrease in %SAD from anterior (left) to posterior (right) as well as the increase in %HEALTHY in the same direction.

Unlike for SAD, no trend was observed in either the presence or distribution of emphysema (EMPH) throughout the lungs of the free-breathing rats. Because airways were removed from all images prior to analysis, the average %EMPH identified by PRM across free-breathing rats was 0.33%. Given the extremely low amount of EMPH identified in the healthy rats imaged here, the presence or absence of SAD largely determined whether a region/voxel of the lung was defined as healthy or not. Thus, the distribution of HEALTHY lung regions identified by conventional PRM follows the observed trend for SAD—with free-breathing rats’ posterior lungs identified as almost entirely healthy (0.227% EMPH and 0.501% SAD), while the anterior lung is labeled as much less so (0.483% EMPH and 2.77% SAD).

We performed the same analysis on EE and EI CTs obtained from the 10 healthy, mechanically ventilated rats. Because mechanical ventilation causes increased alveolar recruitment and lung volume relative to free breathing, we utilized different threshold values than those used for the free-breathing rats. Despite the different thresholds, voxels identified as SAD and EMPH progressively decreased from anterior (Figure 1b, right) (0.583% EMPH and 4.10% SAD) to posterior (Figure 1b, left) (0.246% EMPH and 0.227% SAD), showing a nearly identical trend to that seen in the free-breathing rats. This same trend is also seen in the box and whisker plots of Figures 2c and d, where average %SAD increases from posterior (%SAD=0.227%) to anterior (average %SAD=4.09%).

In both free-breathing and ventilated rats, the PRM identifies nearly the entire posterior lung as healthy while only identifying diseased voxels in the middle and anterior lung. The observed anterior-to-posterior trend in SAD mirrors previously reported trends in dependent vs. non-dependent lung regions in the supine position—in which gravitational effects on regional lung function and air trapping cause the conventional PRM methodology to improperly identify regions in the dependent/posterior lung as healthy and non-dependent/anterior regions as diseased.

Correcting the Anterior-Posterior Gradient – Free Breathing

Figure 3 shows LLNs distributions for healthy tissue in each bin from all free-breathing (Figure 3a) and ventilated (Figure 3b) rats at both EE (circle markers) and EI (diamond markers). In the free-breathing rats, a significant negative trend was observed in bins 1–5, while a significant positive trend in HU attenuation appeared in bins 70–100. Figure 4 shows a comparison of %SAD and %EMPH identification when using both variable (Figure 4a) and fixed thresholds (Figure 4b) in free-breathing rats. When the variable thresholds are applied and the %SAD/%EMPH subsequently averaged, the posterior-anterior trend in %SAD calculation is no longer present—i.e., a progressive increase in %SAD is no longer seen. Additionally, the trend in %EMPH, which was relatively low using both thresholds, remained unchanged. A paired two sample t-test indicated no significant difference between the average %SAD quantification in anterior vs. posterior lung when utilizing variable thresholds (t(19) = −0.08, p=0.93).

Figure 3:

Line plots with standard deviation error bars showing the trend in LLN for Healthy lung tissue HU across 100 bins averaged from all healthy, free-breathing (a) and ventilated rats (b). The circle markers represent LLN values for EE bins in free-breathing and ventilated rats, while the diamond markers represent LLN values for EI bins.

Figure 4:

Line plots showing the posterior-to-anterior trend in average %SAD (red) and average %EMPH (blue) quantification in free-breathing healthy rats (a,b) and ventilated rats (c,d) when using: variable thresholds (a,c), fixed thresholds (b,d). Error bars represent standard deviation for each region.

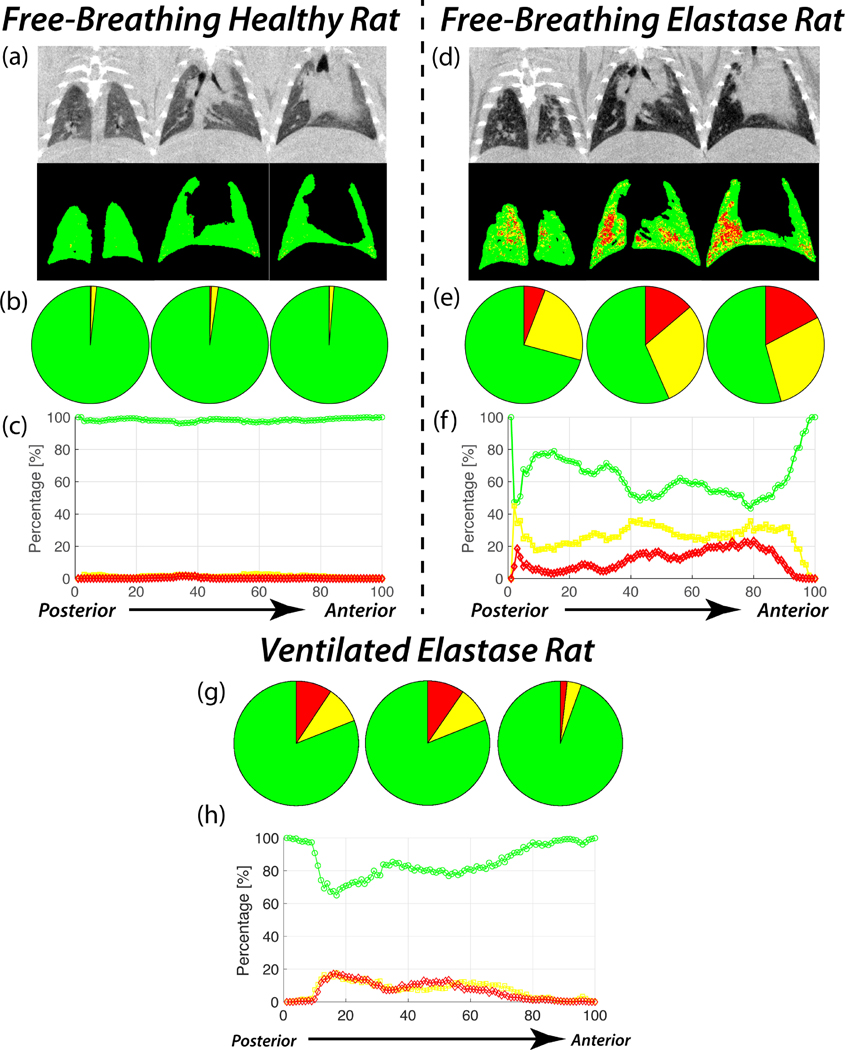

To assess our ability to effectively correct for the anterior-posterior trend seen in the conventional PRM, we applied our correction in a representative healthy rat (Figures 5a–c) and found that the percentage of healthy lung tissue (%HEALTHY) per bin remains uniformly at or near 0 for the entire lung (Figure 5c, green line). In total, the representative healthy rat was determined to have 97.9% healthy lung tissue, with no anterior-posterior trend in %HEALTHY, %SAD, or %EMPH.

Figure 5:

Full PRM analysis using variable thresholds performed on representative free-breathing Healthy (a-c), free-breathing Elastase (d-f), and ventilated Elastase (g,h) rats. Raw CT and PRM lung projections obtained from a Healthy (a) and an Elastase (b) rat, progressing from anterior (left) to posterior (right). Pie charts (b, e, g) representing PRM of %HEALTHY (green), %SAD (yellow), and %EMPH (red), and distributions (c, f, h) of %HEALTHY (green), %SAD (yellow), and %EMPH (red) from bin 1 to bin 100 in the representative rat lungs.

As seen in the lung projections generated using the PRM correction, little to no diseased tissue can be seen in any lung region other than the small portion of airways identified as EMPH (Figure 5). To assess the presence of an anterior-posterior trend, bins 1 to 100 were divided into three regions: posterior (bins 1 – 32), middle (33 – 66), and anterior (67 – 100); %HEALTHY, %SAD, and %EMPH were then determined for each region. As the pie charts plots in Figure 5b show, no anterior-posterior trend was observed in either %SAD or %EMPH in the representative healthy, free-breathing rat. Average %SAD in the posterior, middle and anterior lung were 1.45%, 1.91%, and 1.269%, respectively; %EMPH remained uniformly at or near 0% for nearly the entire lung, with only 0.267%, 0.467%, and 0.113% of voxels identified as such in the posterior, middle, and anterior lung, respectively.

To further validate our PRM methodology, we performed the same analysis with variable thresholds on images acquired in two free-breathing rats with elastase-induced lung injury to test the LLN values for healthy lung in a disease model. Because the original PRM methodology was initially developed using CT scans acquired in COPD patients, we believed elastase injury would be suitable for this application, as many COPD patients also present with emphysema. As seen in Figure 5d and e, the PRM correction using variable thresholds identified substantially more diseased tissue across all regions of the elastase rat’s lung compared to the healthy rats shown in Figures 5a–c. To appreciate this substantial difference quantitatively, Figure 5f shows the distribution of %HEALTHY, %SAD, and %EMPH across the lung of the same representative elastase rat after applying the PRM correction. Interestingly, the anterior and middle lung present nearly identical %HEALTHY tissue distributions (54.3% and 56.6%, respectively), while the posterior lung presents an increased %HEALTHY of 70.8%. Overall, the corrected PRMs identified 60.4% of voxels as healthy lung tissue, while 27.5% and 12.1% of the remaining lung tissue was identified as SAD and EMPH, respectively.

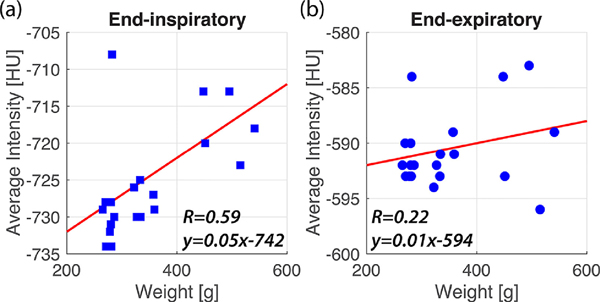

To determine if a relationship exists between tissue density (HU attenuation) and animal weight, we averaged the EE and EI LLN from the middle, most homogeneous portion of the lung (bin 0.35–0.7) and compared this to rat weight (Figure 6). No correlation was found between EE LLN values and weight, while a moderate correlation was seen between EI LLN and weight (R2 = 0.22 and R2 = 0.59, respectively).

Figure 6:

Plots of the average EI (a) and EE (b) HU attenuation from bins 0.34 to 0.66 vs. weight in 20 healthy, free-breathing rats, plotted with the line of best fit.

Correcting the Anterior-Posterior Gradient – Ventilated

To assess the effect of lung volume on PRM thresholds, we performed volumetric CT imaging on an additional 10 mechanically ventilated rats. Following the same PRM methods used for the free-breathing rats, we generated additional position-dependent healthy baseline threshold values for the ventilated rats. Figure 3 shows a side-by-side comparison of the free-breathing (Figure 3a) vs. ventilated (Figure 3b) LLNs for healthy tissue in each bin from all rats at both EE (circle) and EI (diamond). While the LLN values for the ventilated rats were nearly identical to those of the free-breathing, healthy rats at EE, the EI thresholds were set at a much lower density, as the rats were ventilated with a larger tidal volume and were subject to PEEP before imaging to prevent atelectasis. Despite the relative difference in density, the ventilated rats displayed the same trends in HU seen in bins 1–5 and 70–100 in the free-breathing rats.

The fixed threshold PRM again showed the same anterior-to-posterior gradient in %SAD (Figure 4c), which was corrected when applying the variable threshold PRM methodology (Figure 4d). The variable threshold also significantly reduced %SAD and %EMPH across all lung regions in the ventilated rats. A paired two sample t-test indicated no significant difference in the average %SAD quantification in the anterior vs. the lung when utilizing variable thresholds (t(9) = 2.11, p= 0.064).

As seen in the line plot and pie charts of Figure 5g and 5h, variable thresholds were also able to effectively identify diseased lung regions in a representative elastase rat. As opposed to the free-breathing elastase rat, %SAD and %EMPH were nearly quantitatively equal to across all bins in the representative elastase rat. Additionally, the variable threshold PRM identified more diseased voxels in the posterior than in the anterior lung.

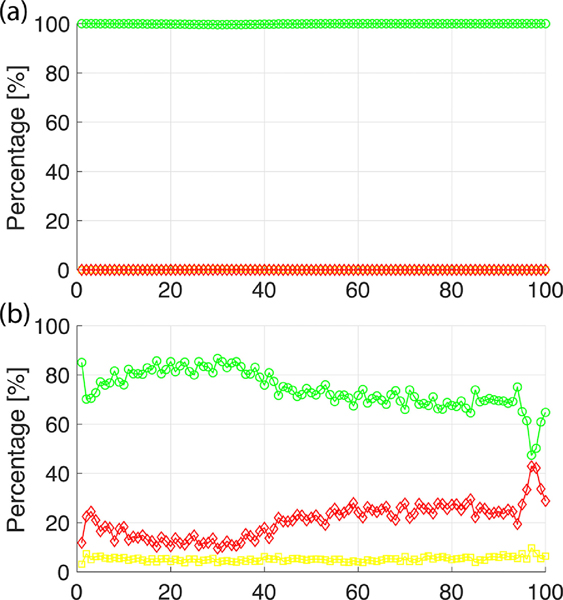

While the variable threshold effectively corrects the anterior-posterior disease quantification gradient found when using fixed thresholds, the differences in Healthy LLN threshold values between free-breathing and ventilated rats appear to be heavily influenced by lung volume at EE and EI, respectively (see Figure 3). We therefore sought to determine how the PRM quantifies disease when images are acquired at increased or decreased lung volumes by applying free-breathing variable thresholds to ventilated rat images and ventilated variable thresholds to free-breathing images. As seen in Figure 7, when ventilated thresholds are applied to all 20 free-breathing rats (reduced lung volume at EE and EI), the variable PRM identifies nearly 100% of voxels across the lung as healthy. Interestingly, when free-breathing thresholds are applied to all 10 ventilated rats (increased lung volume at EE and EI), quantification of healthy lung is less homogeneous, as %EMPH increases to approximately 20% across all bins and reaches a maximum of 42%, while %SAD remains at approximately 5% across all bins.

Figure 7:

Line plots showing %HEALTHY (green circles), %SAD (yellow squares), and %EMPH (red diamond) from bins 0 to 100, quantified by applying free-breathing variable thresholds to ventilated rat images (a) and ventilated variable thresholds to free-breathing rat images (b).

Discussion

We developed a new approach for generating CT-based parametric response maps of the lung that differentiates healthy from diseased voxels by correcting for positionally-dependent characteristics of healthy lung tissue across various lung regions. The approach builds upon previously published methods10 by introducing variable thresholds that account for the expected gradients in x-ray attenuation as well as its homogeneity. These trends are partly anatomical and partly gravity-induced, and are found primarily in the anterior-posterior direction. One of the major advantages provided by our approach is that it derives the LLN for HU attenuation in healthy lung tissue across the lung, rather than treating all voxels as if they belonged to populations with the same positionally dependent characteristics. In this respect, the LLN values used in our method are analogous to those employed in clinically ubiquitous tests like spirometry, which incorporate adjustable expectation values that account for an individual’s demographic characteristics.

The conventional PRM methodology, which utilizes fixed thresholds at EE and EI, has been widely applied to assess disease progression in the COPD cohort9,13,17,18. However, this method is susceptible to an anterior-posterior trend in both %EMPH and, particularly, %SAD quantification. This trend can be qualitatively appreciated by considering the %SAD trends resulting from application of a fixed threshold to the free-breathing and ventilated rat cohorts in Figure 1. Here, %SAD is uniformly at or near 0% in the posterior lung, but progressively increases across the lung until the anterior portion is identified as having as high as ~10% SAD in healthy subjects. While the overall extent of disease determined by this algorithm is dependent on the exact choice of EE and EI thresholds, which differed between free-breathing and ventilated rats, this anterior-posterior trend is present for all threshold values and is clearly incorrect for healthy tissue, as it will almost undoubtedly mask alterations associated with early disease.

When considering how overall lung compliance is affected by vertical gradients in pleural pressure, the bias we describe in the conventional PRM’s identification of diseased voxels becomes understandable. Because the primary threshold used to distinguish SAD from healthy lung tissue is derived from measurements at EE, %SAD is potentially overestimated in non-dependent lung because overall alveolar contraction during exhalation is diminished in this region due to increased transpulmonary pressure which alters tissue compliance22,23. Alveoli in the non-dependent lung remain slightly inflated following exhalation, while alveoli in the dependent lung contract more fully, thus potentially causing the anterior-posterior trend observed in PRM-derived %SAD classifications. Notably, despite the small size and expectation of minimal weight-induced strain, the effect of gravity can be clearly seen in the rat lung by comparing imaging under prone and supine conditions24. This effect is present to a larger degree in human lungs.

Since this trend appears to be indicative of the naturally occurring gravitational gradient within the lung and is associated more with positioning during imaging than the actual presence of disease, we designed our normalized PRM methodology by treating each anterior-posterior region of the organ with unique thresholds that more accurately differentiate healthy from diseased voxels and applied this methodology to CT images from free-breathing and ventilated healthy rats to quantify average HU attenuation and LLN for healthy lung as a function of anterior-posterior distance. The average LLN values at EE and EI in all rats were used to determine %SAD and %EMPH in a manner nearly identical to that of the conventional PRM methodology. As seen in Figure 4, the PRM correction using variable thresholds (Figures 4a and c) eliminates the effect of the gravitational gradient within the lung. Interestingly, as seen in the error bars representing standard deviation, overall disease quantification in the anterior lung is more variable than in the posterior, indicating increased HU inhomogeneity in the former (Figure 4). While this anterior-posterior trend was eliminated in healthy rats, a trend did still appear in %SAD and %EMPH in the free-breathing elastase rats studied here (Figures 5d–f), but not in the ventilated elastase rats (Figure 5g,h). In the case of the free-breathing elastase rats, because emphysema induction with elastase occurs over the course of ~24 hours with the animals in their natural body position, gravity may have allowed the elastase to collect in the ventral-middle lung during induction, thereby causing increased alveolar remodeling in these regions25.

While those PRM trends discussed above appear to be influenced by the naturally occurring gravitational gradient within the lung, decreased lung volume at EI in the free-breathing rats could play a role in overestimating diseased regions. Because the clinical PRM protocol utilizes EE images obtained near FRC and EI images obtained near maximum inhalation, we investigated whether these observed trends were influenced by decreased inflation levels relative to the clinical protocol. The EI LLN values for the ventilated rats (Figure 3b, diamond) were at an overall lower HU value relative to the free-breathing EI (Figure 3a, diamond). Despite the lower HU values, the trends seen in the ventilated and free-breathing EIs are nearly identical, suggesting that the naturally occurring gravitational gradient within the lung influences the LLN values even when EI images are acquired at increased lung volume. Although mechanical ventilation was performed with PEEP 0, the elevated FRC observed is likely due to enhanced alveolar recruitment as a result of mechanical ventilation and the application of PEEP prior to imaging.

Given the recent emphasis placed on CT imaging and PRM analysis for diagnosing and staging COPD18, the PRM correction presented here has the potential to more accurately identify the presence of disease within the lung by considering regional changes in lung function associated with dependent vs. non-dependent lung compliance. Although this initial demonstration utilized a rat model, applying the method to human lung maps would be equally straightforward. Additionally, interpretation of the PRM correction presented here shows that lung volume at both EE and EI greatly influences threshold values for diseased lung. As seen in Figure 7, when utilizing thresholds that assume a decreased volume at EI (free-breathing rat) on images with an increased EI (ventilated rat), the variable PRM drastically overestimates %EMPH and %SAD in otherwise healthy rats solely due to protocol non-compliance (Figure 7b). Similarly, the PRM identifies nearly 100% of the lung as healthy when thresholds assume an increased EI volume but images with decreased EI volumes are applied instead (Figure 7a). While EE volume is a major factor as well, compliance with a well-defined protocol during image acquisition appears to heavily influence the PRM’s ability to identify diseased voxels. In our study, it is likely that this ability was affected by variable breathing dynamics in the free-breathing elastase animals. Based on these observations, any meaningful PRM assessment in patients would therefore require rigid protocol compliance—i.e., where EE is only acquired at FRC (or RV) and EI at maximum inhalation—which may prove similarly difficult in diseased cohorts.

At the same time, however, applying this PRM methodology in humans would necessarily involve dealing with a more heterogeneous patient cohort—in terms of, e.g., genetic variation, sex, and age difference—as the rats studied here. For example, recent human studies have highlighted a relationship between tissue heterogeneity and BMI26, while earlier studies reported no relationship between the two27. To assess whether a relationship between HU attenuation and weight could be observed in our rat cohort, EE and EI LLN values were averaged from bins in the middle third of the lung in all free-breathing rats—a range in which they were relatively homogeneous across all rats (Figure 6). This assessment showed little correlation with weight at EE, while a moderate correlation was seen at EI. Because HU at EE determines the classification of diseased vs. healthy tissue, we conclude that weight had no discernable effect on the determination of overall tissue health, but may slightly affect subclassification into small airways disease and emphysema. The source of the remaining variability among healthy rats cannot presently be attributed to a single factor. It should be noted that although weight had no correlation with EE LLN values in the healthy rats studied here, trends in HU attenuation associated with BMI in humans are still subject to debate.

This study’s primary limitations is that all imaging sessions were performed on a single strain of rat in the supine position. While the PRM methodology described here can be used to derive appropriate thresholds in the same manner with rats from other strains and/or with different positioning, the thresholds introduced here may not be directly applicable. Further limitations of our binning process should also be noted. Given the curvatures of the lung, some bins in the anterior (bins 67 – 100) and posterior (1 – 33) regions contained fewer voxels than other regions from the middle of the lung, making those bins more susceptible to both image blurring related to inconsistent breathing and statistical noise. It is also possible that the gravitationally-induced gradients accounted for in healthy animals are not the same as those in severe disease, where overall tissue compliance has been altered. It is likely that our results were affected by variable breathing dynamics in the free-breathing diseased animals

We also note that neither cohort is a direct analog of the human PRM: free-breathing animals do not achieve TLC and are subject to anesthesia-induced atelectasis, while human subjects are unlikely to achieve the prescribed lung volumes as reliably as ventilated animals. Finally, although we attempted to segment conducting airways out of all lung images, we cannot guarantee that all airways were completely removed. It is likely that some degree of airway distension occurred at EI in the ventilated animals due to the PIP, and the varying airway partial volume contribution to some pixels may have incorrectly shifted their position in the EE/EI plane.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the PRM methodology presented here is able to provide a less-biased identification of diseased lung regions by correcting for alterations in regional lung density associated with the naturally occurring vertical gradient of dependent vs. non-dependent lung density and compliance. This PRM correction proved to be more accurate in assessing %SAD and %HEALTHY within the lung, eliminating the anterior-posterior trend in %SAD quantification seen in conventional PRMs. Additionally, the difference in variable thresholds at different lung volumes provides convincing evidence that EE and EI lung volumes strongly influence the PRM’s quantification of disease. Future work will focus on applying this same PRM methodology to human data sets in an effort to correct these images in the same manner. Once verified in human data sets, this PRM correction has the capacity to provide more accurate assessments of disease state in COPD patients, with the ultimate potential to influence staging and treatment decisions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rooney D, Friese M, Fraser JF, R Dunster K, Schibler A. Gravity-dependent ventilation distribution in rats measured with electrical impedance tomography. Physiol Meas. 2009;30(10):1075–1085. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/30/10/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millar AB, Denison DM. Vertical gradients of lung density in healthy supine men. Thorax. 1989;44(6):485–490. doi: 10.1136/thx.44.6.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunster KR, Friese M, Fraser JF, Cowin GJ, Schibler A. Ventilation distribution in rats: Part I - The effect of gas composition as measured with electrical impedance tomography. Biomed Eng Online. 2012;11:64. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-11-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunster KR, Friese ME, Fraser JF, Galloway GJ, Cowin GJ, Schibler A. Ventilation distribution in rats: Part 2 – A comparison of electrical impedance tomography and hyperpolarised helium magnetic resonance imaging. Biomed Eng Online. 2012;11:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-11-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandoh S, Fujita J, Fukunaga Y, et al. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma masked by gravity-dependent gradient on computed tomography. Intern Med. 2002;41(6):487–490. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattinoni L, Pelosi P, Vitale G, Pesenti A, D’Andrea L, Mascheroni D. Body position changes redistribute lung computed-tomographic density in patients with acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology. 1991;74(1):15–23. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199101000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verschakelen JA, Van fraeyenhoven L, Laureys G, Demedts M, Baert AL. Differences in CT density between dependent and nondependent portions of the lung: influence of lung volume. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(4):713–717. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.4.8372744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chae KJ, Choi J, Jin GY, et al. Relative Regional Air Volume Change Maps at the Acinar Scale Reflect Variable Ventilation in Low Lung Attenuation of COPD patients. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(11):1540–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt SP, Soler X, Wang X, et al. Association between Functional Small Airway Disease and FEV1 Decline in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(2):178–184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201511-2219OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galbán CJ, Han MK, Boes JL, et al. Computed tomography-based biomarker provides unique signature for diagnosis of COPD phenotypes and disease progression. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1711–1715. doi: 10.1038/nm.2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pompe E, Galbán CJ, Ross BD, et al. Parametric response mapping on chest computed tomography associates with clinical and functional parameters in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2017;123:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez CH, Okajima Y, Yen A, et al. Paired CT Measures of Emphysema and Small Airways Disease and Lung Function and Exercise Capacity in Smokers with Radiographic Bronchiectasis. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(3):370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasilescu DM, Martinez FJ, Marchetti N, et al. Noninvasive Imaging Biomarker Identifies Small Airway Damage in Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(5):575–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201811-2083OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevenois PA, de Maertelaer V, De Vuyst P, Zanen J, Yernault JC. Comparison of computed density and macroscopic morphometry in pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(2):653–657. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gevenois PA, De Vuyst P, de Maertelaer V, et al. Comparison of computed density and microscopic morphometry in pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(1):187–192. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belloli EA, Degtiar I, Wang X, et al. Parametric Response Mapping as an Imaging Biomarker in Lung Transplant Recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(7):942–952. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0732OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatt SP, Washko GR, Hoffman EA, et al. Imaging Advances in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Insights from the Genetic Epidemiology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPDGene) Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(3):286–301. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1351SO [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowe KE, Regan EA, Anzueto A, et al. COPDGene® 2019: Redefining the Diagnosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;6(5):384–399. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.6.5.2019.0149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2033–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avants BB, Yushkevich P, Pluta J, et al. The optimal template effect in hippocampus studies of diseased populations. Neuroimage. 2010;49(3):2457–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedenstierna G. Effects of body position on ventilation/perfusion matching. In: Gullo A, ed. Anaesthesia, Pain, Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine — A.P.I.C.E. Springer; Milan; 2005:3–15. doi: 10.1007/88-470-0351-2_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva PL, Gama de Abreu M. Regional distribution of transpulmonary pressure. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(19). doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.10.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santini A, Protti A, Langer T, et al. Prone position ameliorates lung elastance and increasesfunctional residual capacity independently from lung recruitment. ICMx. 2015;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s40635-015-0055-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muñoz-Barrutia A, Ceresa M, Artaechevarria X, Montuenga LM, Ortiz-de-Solorzano C. Quantification of lung damage in an elastase-induced mouse model of emphysema. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2012;2012:734734. doi: 10.1155/2012/734734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramaniam K, Clark AR, Hoffman EA, Tawhai MH. Metrics of lung tissue heterogeneity depend on BMI but not age. J Appl Physiol. 2018;125(2):328–339. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00510.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zach J, Newell J, Schroeder J, et al. Quantitative CT of the Lungs and Airways in Healthy Non-smoking Adults. Invest Radiol. 2012;47(10):596–602. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318262292e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]