Abstract

Objectives

This study focuses on the role of spouses for facilitating goal progress during a phase in life when individual resources for goal pursuit are particularly limited. Specifically, we examined the moderating role of relationship characteristics in old age for time-varying partner involvement–goal progress associations as couples engaged in their everyday lives. We also assessed time-varying associations between everyday goal progress, effectiveness of partner contributions, and spousal satisfaction with this contribution.

Methods

We used multilevel modeling to analyze data from 118 couples (Mage = 70 years, SD = 5.9; 60–87 years, 50% women; 57% White). Both partners reported their personal goals and provided information on relationship satisfaction, conflict, and support. They also provided simultaneous ratings of everyday goal progress, effort, partner involvement as well as effectiveness of and satisfaction with partner contribution up to three times daily over 7 days.

Results

In line with expectations, higher relationship satisfaction and support and lower conflict were associated with higher goal progress when the partner was involved in goal pursuit. Both effectiveness of and satisfaction with partner contributions were positively associated with everyday goal progress.

Discussion

Whether partner involvement is beneficial for goal progress depends on characteristics of the relationship as well as what partners actually do in everyday life. This highlights the importance of considering both stable person characteristics as well as time-varying processes to capture the complexity of goal pursuit in older couples.

Keywords: Goal progress, Relationships, Social support, Successful aging

People are active agents who shape their own development through the setting and pursuit of goals (Baltes et al., 1999). Goals provide direction, purpose, and meaning in life (Emmons, 2003; Hooker, 2002; Siegler et al., 2010). Importantly, most goals are not pursued in isolation; in many endeavors significant others are involved to some extent (Berg et al., 1998; Fitzsimons & van Dellen, 2015; Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2016; Mejía & Hooker, 2013). This may be especially true in old age, when older adults face age-related challenges that might hamper individual efforts in the pursuit of their goals, forcing them to search for alternative means to compensate for these age-normative resource losses, for example, by drawing on support from significant others (Baltes & Carstensen, 1999; Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Haase et al., 2013; Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2016). Goals can focus on different timeframes and reflect various levels of abstraction; some may be achieved over years, others are more proximal. This study targets salient goals at a relatively low level of abstraction to be able to link them to older adults’ everyday lives and activities (Hooker, 2002; Hoppmann & Klumb, 2006; Little, 2008). We use multiple daily electronic assessments over 1 week from a sample of 118 couples (Mage = 70, 50% women) to examine how older spouses may contribute to each other’s goal pursuit in everyday life. Particular attention is paid to who may benefit from their partner’s contributions to goal progress, and under what conditions.

Goal Pursuit in Couples

The call for an explicit consideration of the important role of social others for goal pursuit is growing louder (Baltes & Carstensen, 1999; Feeney, 2004; Fitzsimons et al., 2015; Fitzsimons & van Dellen, 2015). A wealth of theoretical work and empirical evidence mainly emanating from the social relationships literature but also including some aging studies indicates that many if not most goals involve other people (Baltes & Carstensen, 1999; Fitzsimons & van Dellen, 2015; Mejía & Hooker, 2013), that individuals look to others for support on their goals, and that those who receive support make more progress both in daily life and over longer time periods (Brunstein et al., 1996; Fitzsimons & Shah, 2008; Jakubiak & Feeney, 2016; Jakubiak et al., 2020). Partners may serve as relational catalysts who help embrace challenges and pursue opportunities for growth, ultimately facilitating goal accomplishment (Feeney et al., 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2016). Partnerships offer the potential for pooling goal-relevant resources and collaborative problem-solving, thus enabling what may not be possible alone (Deutsch, 2000; Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2013; Wilensky, 1983). Of note, there may also be circumstances under which spouses compete for goal-relevant resources that give rise to goal conflict, as shown by the work and family literature and more recently during the pandemic (Hooker et al., 1996; Hoppmann et al., 2013; Salmela-Aro et al., 2000; Vowels & Carnelley, 2021). In other words, involving the partner in one’s goal pursuit has tremendous potential to advance progress, but doing so can also go along with conflicts, making it important to consider that partners have the capacity to facilitate or hamper goal progress.

To date, most research on everyday goal pursuit in couples is based on younger samples. A notable exception is work by Jakubiak and colleagues (Jakubiak & Feeney, 2016; Jakubiak et al., 2020) who recruited both young and older couples into daily diary studies showing that more partner support promotes same-day and next-day goal progress, and that partner support also is associated with lower distress and higher relationship quality. Building on these findings, this study provides a higher resolution of goals paying particular attention to how different relationship dimensions might propagate goal progress. This is important for several reasons: older spouses typically represent the single most important tie in old age (Fingerman & Charles, 2010), they engage in many joint activities, and turn to each other for support (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2014, 2016). This may put them in a unique position to compensate for age-related resource losses and facilitate goal achievement (Berg et al., 2003; Dixon & Gould, 1998; Margrett & Marsiske, 2002; Rauers et al., 2011). Nonetheless, significant interindividual differences in the quality of social relationships remain into old age and may have important ramifications for everyday goal pursuit (Antonucci et al., 2001; Fiori et al., 2008; Mejía & Hooker, 2013).

The Present Study

This study builds on and extends previous work on goal pursuit in couples by examining the role of interindividual differences in relationship characteristics and time-varying indicators of spousal involvement for everyday goal progress in old age. In line with the personal project literature, goals are assessed at a level of abstraction that allows linking them to everyday activities (Hoppmann & Klumb, 2006; Little, 1983). We specifically considered interindividual differences in relationship characteristics to better understand who benefits from spousal involvement in goal pursuit.

The literature consistently focuses on positive characteristics of close ties, like satisfaction, but it is also important to take into account negative aspects, such as conflict (Birditt et al., 2016; Fingerman et al., 2004; Krause & Rook, 2003). Thus, this study focuses on three different relationship dimensions: relationship satisfaction, support, and conflict (Hendrick, 1988; Pierce, 1994). Relationship satisfaction is a key characteristic that is relevant to goal pursuit because it may capture how likely someone is to let another person in (Hendrick, 1988; Jakubiak & Feeney, 2016). We expected that highly satisfying relationships where partners meet each other’s needs promote goal progress when the partner is involved in goal pursuit (Cappuzzello & Gere, 2018; Hendrick, 1988; Hofmann et al., 2015; Jakubiak & Feeney, 2016). Similarly, we expected that relationships where older adults can count on their partner for advice, honest feedback, and support make it particularly likely that a partner’s involvement in everyday goal pursuit is associated with goal progress (Jakubiak et al, 2020; Pierce, 1994). Despite the fact that spouses are uniquely positioned to support each other’s goal pursuit, it is also important to recognize that close relationships may at times limit opportunities and involve conflict (Fingerman et al., 2004). To avoid painting an overly rosy picture, the present study also considered the role of relationship conflict in shaping goal pursuit. Specifically, we expected that partnerships characterized by feelings of anger, guilt, and conflict may hamper goal progress when the partner is involved in goal pursuit (Pierce, 1994).

In addition to a consideration of stable relationship characteristics as potential moderators of partner involvement–goal progress associations in everyday life, the present study also examines the time-varying nature of everyday spousal contributions. Building on previous work with younger samples and unrelated older individuals, we examine both the extent to which spousal contributions to goal pursuit are deemed effective and how satisfied older adults are with the respective partner’s contributions at any given moment (Cappuzzello & Gere, 2018; Fitzsimons & Shah, 2008; Mejía & Hooker, 2013). We expected both everyday effectiveness as well as satisfaction with contributions to be key ingredients that propel goal progress.

The overall purpose of this study was to examine for whom and under what circumstances a partner’s involvement may benefit everyday goal progress in old age. We expected that a partner’s involvement in goal pursuit would benefit everyday goal progress in spouses reporting high relationship satisfaction, high support, and low conflict. Furthermore, we expected that the effectiveness of a partner’s contribution and spousal satisfaction with it would be positively associated with everyday goal progress in the present sample of older couples. Given well-established associations between age, gender, and goal pursuit (Hooker & McAdams, 2003), we considered these important factors as covariates.

Method

Participants

Participants were 129 community-dwelling couples from the larger Vancouver metropolitan area who participated in a project on spousal health dynamics in old age (for details, see Pauly et al., 2019). Couples were recruited through community centers and media advertising. Eligibility required participation of both partners, being aged 60 years or older, the ability to read English, Cantonese, or Mandarin proficiently, the ability to read newspaper-sized print, hear an alarm, and not suffering from any neurodegenerative disease or brain dysfunction.

Of the 129 couples, nine dropped out, one couple was excluded due to limited command of the study languages, and one couple had missing data. The remaining 118 couples had an average age of 70 years (SD = 5.9 years, 60–87 years, 50% women). Participants were mostly White or Asian (59% White, 34.5% Asian; 6.4% other). Both partners of a couple participated in the same study language. Thirty-three couples completed the study in Mandarin, the rest in English. Participants rated their health as good (M = 3.3, SD = 0.95; 1 = poor to 5 = excellent). Most were retired (87.4%) with some university education (65.6%). Participants were given $100 each as compensation for their efforts. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board.

Procedure

Participants attended a baseline session where they answered questionnaires about their background, personal goals, and various individual difference measures. Couples then started a 7-day time-sampling phase, during which each participant completed five self-report questionnaires per day on an older adult-friendly iPad app (iDialogpad; G. Mutz, Cologne, Germany). Seven participants completed an additional day because of technical difficulties. The first two daily questionnaires were self-elicited after getting up and captured questions not relevant to this study. The third, fourth, and fifth daily questionnaires were prompted by an auditory signal (11:00 a.m., 04:00 p.m., and 09:00 p.m.) and included momentary affect ratings and questions about goal progress, effort put into goal pursuit, and partner involvement in goal pursuit since the previous questionnaire, collectively covering goal-relevant information between getting up and going to bed. Whenever the partner had been involved in goal pursuit, two follow-up questions asked about the extent to which their contribution had been effective and satisfying. At the end of the 7 days, participants completed more measures including relationship questionnaires, study feedback, and returned study materials. Participants reported their time in the study as typical of their everyday life (M = 3.8, SD = 1.0, 0 = Not at all to 5 = Very much). Adherence to the time-sampling protocol was 95%, with 4,726 daily questionnaires completed out of 4,956 scheduled ones.

Measures

Relationship characteristics

Participants completed the Relationship Assessment Scale (M = 4.14, SD = 0.74; 5-point scale; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84; Hendrick, 1988), which captures global relationship satisfaction. Relationship-specific support and conflict were assessed using the Quality of Relationship Inventory (Pierce, 1994): support consisting of seven items (M = 3.93, SD = 0.71, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and conflict consisting of 12 items (M = 2.45, SD = 0.61; 5-point scale; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91).

Goals

Participants were asked to list three open-ended goals they planned to actively pursue within the upcoming weeks, whose realization was highly important for them, and which influenced their daily lives and activities (Hoppmann & Klumb, 2006; Little, 1983; Ungar et al., 2021). For each goal, participants were asked to select one or more content domains (partnership, family, friends, physical activity, nutrition, finances, cognition or memory, health, productive/work activities, home management, leisure, other). Most goals were related to health (40.93%), leisure (36.6%), and partnership (29.3%).

Everyday goal pursuit

Participants were asked to rate the effort they had put into the pursuit of their goals since the previous questionnaire (0 = not at all, 100 = very much). Participants carried “goal cards” with them to remind them of the three goals they had listed at baseline. Effort for each measurement point was computed by averaging across the three goals (M = 36.01, SD = 21.00).

Everyday goal progress was rated on a 0–100 scale with higher values indicating more goal progress. Goal progress at each measurement point was computed by averaging across all three goals (M = 41.19, SD = 20.79).

Partner involvement

Participants were asked whether their partner had been involved in the pursuit of one of their three goals since the previous questionnaire (60.3% no; 39.7% yes). Two follow-up questions appeared whenever the partner had been involved in goal pursuit. Participants were asked to rate how effective their partner’s contribution was for their goal pursuit (M = 73.79, SD = 20.78; 0 = not effective at all, 100 = very effective) and how satisfying their partner’s contribution had been (M = 79.22, SD = 19.09; 0 = not satisfying at all, 100 = very satisfying).

Control variables

Covariates included age (M = 70, SD = 5.9; 60–87 years), gender (50% women), and day in study (seven participants had technical difficulties and completed an additional day). We further controlled for marriage duration (M = 40.9 years, SD = 12.9) and ethnicity. Because neither marriage duration nor ethnicity was significantly associated with the outcomes of interest, models exclude these covariates for reasons of parsimony.

Statistical analysis

The four-level structured data (measurement points nested within days crossed between partners nested within couples) were analyzed using the R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015). This package allowed us to specify the crossed nature of spousal assessments. To account for variation between and within people, we included time-varying predictors (person-centered) as well as person-level means (grand-mean-centered) for goal effort, occasions the partner was involved in goal pursuit, effective partner contributions, and satisfying partner contributions. Example code for the models is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between participants’ person-level variables are presented in Table S1 in the Supplementary Document. Men were older and more satisfied with their marriage than wives. Older participants reported more effort and less support than younger participants. Goal progress and effort were positively correlated, as were the three relationship dimensions. Effective and satisfactory contributions were positively correlated with each other (as within-person correlations can also be meaningful, they are reported in Table S1 in the Supplementary Document), and with goal progress.

Goal Pursuit in Old Age

We first examined the origins of variability in everyday goal progress using intraclass correlations. Everyday goal progress varied across all four levels with most variability at the person level (measurement point level = 27%; day level = 16%; person level = 35%; couple level = 22%). We then continued to model time-varying and person-level main effects of effort and partner involvement on everyday goal progress (Table 1, Model A). In line with our expectations, momentary increases in effort and interindividual differences in effort were positively associated with everyday goal progress. The main effect for momentary partner involvement was also significant (b = 1.06, p = .045), demonstrating that more progress was made during moments when partners were involved in goal pursuit. The corresponding person-level main effect did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Linear Models Predicting Goal Progress From Cross-Level Interactions of Partner Involvement and Relationship Measures Using R (N = 236)

| Model A Coefficient (p value) |

Model B Coefficient (p value) |

Model C Coefficient (p value) |

Model D Coefficient (p value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | Support | Conflict | ||

| Intercept | 40.58 (.000)** | 40.62 (.000)** | 40.59 (.000)** | 40.59 (.000)** |

| Age | −0.36 (.007)** | −0.36 (.007)** | −0.37 (.007)** | −0.37 (.006)** |

| Day of study | 0.57 (.000)** | 0.58 (.000)** | 0.57 (.000)** | 0.58 (.000)** |

| Women | −4.35 (.002)** | −4.54 (.001)** | −4.41 (.001)** | −4.41 (.001)** |

| Aggregated effort | 0.86 (.000)** | 0.84 (.000)** | 0.84 (.000)** | 0.84 (.000)** |

| Aggregated partner involvement | 0.08 (.975) | 0.53 (.841) | 0.14 (.957) | 0.51 (.844) |

| Momentary effort | 0.69 (.000)** | 0.68 (.000)** | 0.68 (.000)** | 0.69 (.000)** |

| Momentary partner involvement | 1.06 (.045)* | 1.03 (.049)* | 0.99 (.054) | 0.98 (.059) |

| Relationship satisfaction | −1.37 (.199) | |||

| Relationship support | −0.57 (.601) | |||

| Relationship conflict | 1.99 (.118) | |||

| Relationship satisfaction × Partner involvement | 1.77 (.009)** | |||

| Relationship support × Partner involvement | 2.62 (.000)** | |||

| Relationship conflict × Partner involvement | −2.33 (.005)** | |||

| Random effects | ||||

| Couple level intercept | 4.30 (.111) | 4.31 (.111) | 4.23 (.123) | 4.14 (.094) |

| Individual level intercept | 9.97 (.000)** | 9.96 (.000)** | 9.97 (.000)** | 9.91 (.000)** |

| Partner involvement | 4.01 (.000)** | 3.88 (.000)** | 3.74 (.000)** | 3.85 (.000)** |

| Momentary effort | 0.26 (.000)** | 0.26 (.000)** | 0.26 (.000)** | 0.26 (.000)** |

| Day of study intercept | 4.14 (.000)** | 4.15 (.000)** | 4.15 (.000)** | 4.13 (.000)** |

| Residual | 8.46 | 8.45 | 8.45 | 8.45 |

Notes: Marriage duration and ethnicity were further considered; their inclusion did not change the reported results. We reran all models excluding low endorsement measurement points for goal progress (8.6% reported 0 goal progress); findings did not change substantively.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Goal Pursuit in Couples

Next, we examined main effects for the three different relationship characteristics and respective cross-level interactions with momentary partner involvement on goal progress to examine the role that relationship characteristics might play on partner involvement–goal progress associations (Table 1, Models B–D). When adding relationship satisfaction into the model (Table 1, Model B), its main effect was not significant (b = −1.37, p = .199), but there was a significant cross-level interaction with partner involvement (b = 1.77, p = .009). As illustrated in Figure 1 in relationships with higher satisfaction, partner involvement was more strongly linked with more goal progress.

Figure 1.

Interaction effect of partner involvement and relationship satisfaction for predicting goal progress. Notes: Relationship satisfaction scores were modeled as a continuous moderator for partner involvement in goal progress. Higher scores are above the 75th percentile, while lower scores are those that fall below the 25th percentile. The figure illustrates that goal progress is higher in people with higher relationship satisfaction when the partner is involved. The simple slope for high satisfaction was significant (b = 2.18, p = .002), for low satisfaction it was not (b = −0.32, p = .671).

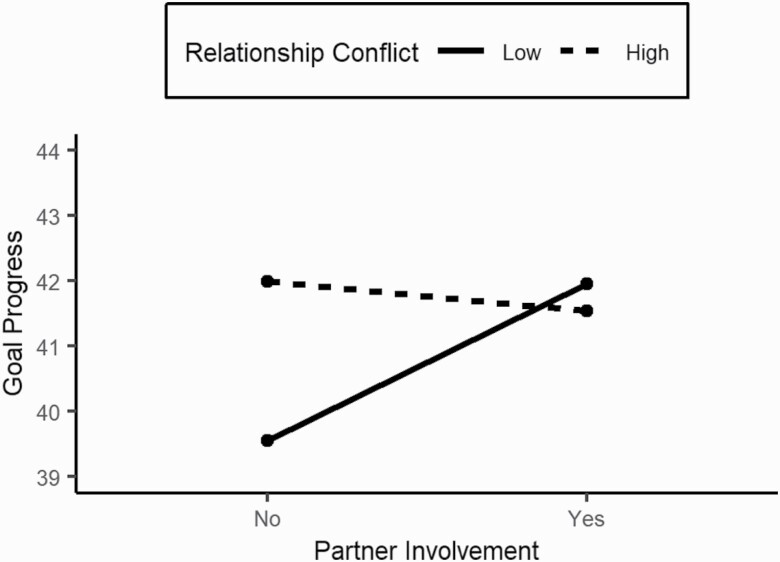

When adding relationship support (Table 1, Model C), the main effect was again not significant (b = −0.57, p = .601), but there was also a significant cross-level interaction with partner involvement (b = 2.62, p = .000). As illustrated in Figure 2, in relationships characterized by higher support, partner involvement was more strongly linked with higher goal progress. Relationship conflict (Table 1, Model D) again did not reveal a significant main effect (b = 1.99, p = .118), but had a significant cross-level interaction with partner involvement (b = –2.33, p = .005). As illustrated in Figure 3, in relationships with less conflict, partner involvement was more strongly associated with goal progress.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect of partner involvement and relationship support for predicting goal progress. Notes: Relationship Quality Inventory Support Subscale scores were modeled as a continuous moderator of partner involvement on goal progress. High support shows model implied slopes for the 75th percentile, while low support represents the 25th percentile. The figure illustrates that goal progress is higher in people with higher perceived support when their partner is involved. The simple slope for high support was significant (b = 2.74, p = .001), for low support it was not (b = −0.93, p = .206).

Figure 3.

Interaction effect of partner involvement and relationship conflict for predicting goal progress. Notes: Relationship Quality Inventory Conflict Subscale scores were modeled as a continuous moderator of partner involvement on goal progress. Higher conflict is above the 75th percentile, while low conflict is below the 25th percentile. The figure illustrates that goal progress is higher in people with less relationship conflict when the partner is involved. The simple slope for high conflict was not significant (b = −0.67, p = .410), for low conflict it was (b = 2.23, p = .002).

Using the marginal R2 approach (Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2013), variance explained for each model was as follows: Relationship Satisfaction Model 65.1%, Support Model 65.1%, and Conflict Model 65.1%. The reduction in deviance, when comparing with Model A (with no interactions), was significant for each model: Relationship Satisfaction Model (χ 2 = 7.72, df = 2, p = .02), Support Model (χ 2 = 13.55, df = 2, p = .001), and Conflict Model (χ 2 = 8.99, df = 2, p = .01).

We then proceeded to examine the predicted time-varying associations using the subset of measurement points when partners had been involved in goal pursuit (Table 2, Models E and F). In line with expectations, participants reported more goal progress when their partner’s contributions were deemed more effective (b = 0.06, p = .004). In addition, individuals whose partner’s contributions were generally more effective also reported more overall goal progress (b = 0.11, p = .013). Furthermore, participants reported greater goal progress when they were more satisfied with their partner’s contributions than usual (b = 0.07, p = .011).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Linear Models Predicting Goal Progress From Effective and Satisfying Partner Involvement Using R (N = 236)

| Model E Coefficient (p value) |

Model F Coefficient (p value) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Effective contribution | Satisfying contribution | |

| Intercept | 41.79 (.000)** | 41.56 (.000)** |

| Age | −0.14 (.283) | −0.16 (.258) |

| Women | −2.82 (.055) | −2.74 (.065) |

| Day of study | 0.36 (.003)** | 0.40 (.001)** |

| Momentary effective contribution | 0.06 (.004)** | |

| Aggregated effective contribution | 0.11 (.013)** | |

| Momentary satisfying contribution | 0.07 (.011)* | |

| Aggregated satisfying contribution | 0.06 (.174) | |

| Momentary effort | 0.80 (.000)** | 0.81 (.000)** |

| Aggregated effort | 0.68 (.000)** | 0.68 (.000)** |

| Random effects | ||

| Day of study intercept | 2.83 (.000)** | 2.73 (.000)** |

| Couple intercept | 2.86 (.000)** | 2.93 (.459) |

| Individual intercept | 9.07 (.000)** | 9.19 (.000)** |

| Momentary effort | 0.23 (.000)** | 0.23 (.000)** |

| Momentary effective contribution | 0.12 (.002) | |

| Momentary satisfying contribution | 0.16 (.000)** | |

| Residual | 8.02 | 7.95 |

Notes: Marriage duration and ethnicity were further considered; their inclusion did not change the reported results.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Using the marginal R2 approach (Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2013), variance explained for each model was as follows: Effectiveness Model 65.1% and Satisfaction Model 66.1%. The reduction in deviance for Effectiveness and Satisfaction, when comparing with a model without these additional predictors, was significant for each model: Effectiveness (χ 2 = 31.15, df = 4, p = .001), Satisfaction (χ 2 = 42.29, df = 4, p < .001). Parallel tables for models accounting for autocorrelation can be found in the Supplementary Document.

Discussion

This study examined when and for whom partner involvement in goal pursuit facilitates everyday goal progress using repeated daily life assessments from a sample of older couples. Consistent with our predictions, increased individual efforts and partner involvement were associated with goal progress and relationship characteristics moderated partner involvement–goal progress associations. Partner involvement was most beneficial when the relationship was high in satisfaction, high in support, and low in conflict. Furthermore, time-varying effectiveness and spousal satisfaction with involvement were positively associated with everyday goal progress. Findings are discussed in the context of the social relationship and aging literatures.

Goal Pursuit in Old Age

Our findings are consistent with the idea that goal progress continues to play a key role into older adulthood when it becomes more challenging (Riediger et al., 2005). We had expected that in addition to individual efforts, partner involvement would increase goal progress by compensating for means that are no longer available in old age. We found that more individual effort was associated with more goal progress and there was an additional significant main effect for partner involvement. Our findings dovetail with the relationship and emotion literature by showing that spouses play a key role in facilitating meaningful activities (Carstensen, 1992; English & Carstensen, 2014).

Further, our findings are in line with social extensions of the Model of Selective Optimization with Compensation, which emphasize the key role of close others for optimizing goal pursuit and compensating for previously available means in old age (Baltes & Carstensen, 1999; Freund & Baltes, 2000; Ko et al., 2014). By involving the partner in goal pursuit, older adults may be able to compensate for age-normative resource losses and increase their goal progress. To further substantiate and potentially qualify how partner involvement may propel goal progress, this study also took into consideration specifics of the relationship such as its quality (i.e., satisfaction) and its function, such as support and conflict.

Goal Pursuit in Older Couples

In line with our expectation, relationship characteristics moderated time-varying associations between partner involvement and goal progress in such a way that spouses who rated their relationship as high in satisfaction and support made more goal progress when the respective partner was involved in goal pursuit than spouses who rated their relationship as lower in satisfaction and support. Furthermore, spouses who rated their relationship as higher as compared to lower in conflict displayed weaker partner involvement–goal progress associations. This supports our hypothesis that relationship characteristics moderate partner involvement for everyday goal progress in old age and provides us with more knowledge of for whom partner involvement may be particularly beneficial.

These results point at the potential of high-quality relationships for propagating goal progress. It is important to recognize that in general, people tend to prefer being around people who promote their goal progress and who are instrumental to their goals (Fitzsimons & Fishbach, 2010; Fitzsimons & Shah, 2008). The current study represents a snapshot out of the daily lives of older couples, who usually have good relationships and prioritize emotionally meaningful interactions (Aron & Aron, 1996; Butler & Randall, 2013; Luong et al., 2011). We speculate that this prioritization of meaningful interactions puts them in a unique position to foster goal progress during a phase in life when resources become more limited.

Our findings further show that both the effectiveness of a partner’s contribution and spousal satisfaction shape everyday goal progress. They demonstrate that not only do relationship characteristics matter, but also what happens when the partner is involved in goal pursuit. These findings dovetail with the motivational and emotional aging literatures by showing both the compensatory potential (effectiveness) as well as the satisfaction with how it is delivered being positively associated with goal progress (Baltes & Carstensen, 1999; Berg et al., 2003; Mejía & Hooker, 2013).

The targeted associations may be bidirectional such that positive relationships facilitate goal progress and goal progress boosts relationship quality (Braithwaite & Holt-Lunstad, 2017; Coyne et al., 2001; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). It is also important to recognize that the current sample had very long relationship histories as it is typical for this cohort (mean marriage duration exceeded 40 years). This must be taken into consideration when examining the currently aging baby boomers who enter old age with much more diverse relationship histories than earlier born cohorts.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study has several strengths. First, we collected data multiple times a day representing life as it is lived. Second, we had high adherence (95%), both contributing to generalizability. Third, we recruited a diverse sample, facilitated by offering study completion in multiple languages. Fourth, we considered multiple relationship characteristics. Finally, we examined time-varying partner involvement–goal progress associations.

Several limitations of our measures, study design, and sample need to be considered. First, everyday goal progress was merged across three goals due to the increased complexity and lack of power for differentiating between them; future research should supplement this approach by zooming in on particular goals, such as health goals (Choun et al., 2017). Furthermore, momentary effectiveness of and satisfaction with partner involvement were assessed using single items which were highly correlated. Second, this study represents a 1-week snapshot of participants’ everyday lives; goals were measured at a level of abstraction that allowed linking them to everyday activities. Indeed, participants regularly worked on their goals and reported reasonable progress (M goal progress = 41 on a 100-point scale). When asked about the extent to which they were able to accomplish their goals at the end of the study, 96.2% of participants reported at least some accomplishment on one of their three goals. Future work could complement this approach by covering all stages of goal pursuit including goal setting, implementation, and accomplishment. Similarly, the limited sampling period may not have captured the full range of how spouses may support each other.

Furthermore, we had a predominantly healthy sample. Focusing on individuals living with the effects of chronic conditions (Wilson, 2000) might complement our findings under particularly severe resource constraints. Doing so would lead to more nuanced findings, with ramifications for interventions. Additionally, our sample was predominantly happy. Focusing on more conflictual relationships, like those considering divorce, could shed light on the dark side of relationships. It may also be worth exploring if expectancy violations in couples reporting high satisfaction, high support, and low conflict may undermine goal progress when the partner is not involved.

Finally, limitations in power had to be considered and thus, we did not estimate separate intercepts and slopes for husbands and wives as recommended by Bolger and colleagues (e.g., Laurenceau & Bolger, 2005). Instead, we estimated models using nondistinguishable partners. Careful consideration was taken of the crossed nature of repeated daily life assessments from partners by specifying the error structure as follows: days were treated as nested within couples and crossed between partners. This was possible using lme4 (Bates et al., 2015), with the following crossed specification for the day level: (i.e., “(1 | idc:dos) instead of (1 | idc/id/dos)” with idc being an indicator for the couple, id being an indicator for the person, and dos being an indicator for day of study). Not all coefficients were allowed to vary at random. We estimated random effects for effort and partner involvement and effectiveness of and satisfaction with partner contributions. Future work with larger samples needs to replicate our findings to more fully capture the dynamics underlying goal pursuit in older couples by estimating separate intercepts and slopes for husbands and wives.

Conclusions

This study sheds light on the important role of spouses for everyday goal pursuit in old age. It shows that spouses in relationships with high satisfaction, high support, and low conflict particularly benefit from their partner’s involvement in goal pursuit and that the effectiveness of and satisfaction with a partner’s contribution are associated with everyday goal progress. Thus, partners have the potential to help achieve what may not (or no longer) be possible alone; we hope for an increased recognition of the role of partners in psychological aging research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) Program to C. A. Hoppmann, the CRC Program to M. C. Ashe, and the Li Tze Fong Fellowship to T. Pauly. This research was not preregistered and uses data from a larger project on spousal health dynamics. In line with transparency of research data analytic methods, data and study materials will be made available upon request for verification purposes. Participants did not provide informed consent to open data access. We thank the study participants, who gave generously of their time, and Anita DeLongis and Nancy Sin for their insightful comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-123501 to C. A. Hoppmann, M. C. Ashe, D. Gerstorf, S. Heine).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Antonucci, T. C., Lansford, J. E., & Akiyama, H. (2001). Impact of positive and negative aspects of marital relationships and friendships on well-being of older adults. Applied Developmental Science, 5, 68–75. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0502_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1996). Love and expansion of the self: The state of the model. Personal Relationships, 3, 45–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1996.tb00103.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, M. M., & Carstensen, L. L. (1999). Social–psychological theories and their applications to aging: From individual to collective. In Bengtson V. L. & Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Aging (pp. 209–226). Springer Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan psychology: Theory and application to intellectual functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, C. A., Johnson, M. M. S., Meegan, S. P., & Strough, J. (2003). Collaborative problem-solving interactions in young and old married couples. Discourse Processes, 35, 33–58. doi: 10.1207/S15326950DP3501_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, C. A., Meegan, S. P., & Deviney, F. P. (1998). A social-contextual model of coping with everyday problems across the lifespan. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22, 239–261. doi: 10.1080/016502598384360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, C. A., & Upchurch, R. (2007). A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133(6), 920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S., Newton, N. J., Cranford, J. A., & Ryan, L. H. (2016). Stress and negative relationship quality among older couples: Implications for blood pressure. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(5), 775–785. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, S., & Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). Romantic relationships and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein, J. C., Dangelmayer, G., & Schultheiss, O. C. (1996). Personal goals and social support in close relationships: Effects on relationship mood and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 1006–1019. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.1006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, E. A., & Randall, A. K. (2013). Emotional coregulation in close relationships. Emotion Review, 5, 202–210. doi: 10.1177/1754073912451630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L. L. (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuzzello, A. C., & Gere, J. (2018). Can you make my goals easier to achieve? Effects of partner instrumentality on goal pursuit and relationship satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 25(2), 268–279. doi: 10.1111/pere.12238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choun, S., Hooker, K. A., & Mejía, S. T. (2017). The within-person coupling of health goal pursuit and affect over 100 days. Innovation in Aging, 1(Suppl_1), 1183–1183. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx004.4310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, J. C., Rohrbaugh, M. J., Shoham, V., Sonnega, J. S., Nicklas, J. M., & Cranford, J. A. (2001). Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology, 88(5), 526–529. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M. (2000). Cooperation and competition. In Deutsch M. & Coleman P. T. (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (pp. 21–40). Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R. A., & Gould, O. N. (1998). Younger and older adults collaborating on retelling everyday stories. Applied Developmental Science, 2, 160–171. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0203_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. In Keyes C. L. M. & Haidt J. (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 105–128). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10594-005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English, T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2014). Selective narrowing of social networks across adulthood is associated with improved emotional experience in daily life. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2), 195–202. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney, B. C. (2004). A secure base: Responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney, B. C., Van Vleet, M., Jakubiak, B. K., & Tomlinson, J. M. (2017). Predicting the pursuit and support of challenging life opportunities. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(8), 1171–1187. doi: 10.1177/0146167217708575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., & Charles, S. T. (2010). It takes two to tango: Why older people have the best relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 172–176. doi: 10.1177/0963721410370297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Hay, E. L., & Birditt, K. S. (2004). The best of ties, the worst of ties: Close, problematic, and ambivalent social relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 792–808. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00053.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, K. L., Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (2008). Profiles of social relations among older adults: A cross-cultural approach. Ageing and Society, 28, 203–231. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X07006472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, G. M., Finkel, E. J., & van Dellen, M. R. (2015). Transactive goal dynamics. Psychological Review, 122(4), 648–673. doi: 10.1037/a0039654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, G. M., & Fishbach, A. (2010). Shifting closeness: Interpersonal effects of personal goal progress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 535–549. doi: 10.1037/a0018581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, G. M., & Shah, J. Y. (2008). How goal instrumentality shapes relationship evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 319–337. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, G. M., & van Dellen, M. R. (2015). Goal pursuit in relationships. In Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R., Simpson J. A., & Dovidio J. F. (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of personality and social psychology, vol. 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 273–296). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/14344-010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2000). The orchestration of selection, optimization and compensation: An action-theoretical conceptualization of a theory of developmental regulation. In Perrig W. J. & Grob A. (Eds.), Control of human behavior, mental processes, and consciousness: Essays in honor of the 60th birthday of August Flammer (pp. 35–58). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, C. M., Heckhausen, J., & Wrosch, C. (2013). Developmental regulation across the life span: Toward a new synthesis. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 964–972. doi: 10.1037/a0029231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50, 93–98. doi: 10.2307/352430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, W., Finkel, E. J., & Fitzsimons, G. M. (2015). Close relationships and self-regulation: How relationship satisfaction facilitates momentary goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 434–452. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, K. (2002). New directions for research in personality and aging: A comprehensive model for linking levels, structures, and processes. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 318–334. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00012-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, K., Fiese, B. H., Jenkins, L., Morfei, M. Z., & Schwagler, J. (1996). Possible selves among parents of infants and preschoolers. Developmental Psychology, 32, 542–550. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, K., & McAdams, D. P. (2003). Personality reconsidered: A new agenda for aging research. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(6), P296–P304. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.p296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann, C. A., & Gerstorf, D. (2013). Spousal goals, affect quality, and collaborative problem solving: Evidence from a time-sampling study with older couples. Research in Human Development, 10, 70–87. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2013.760260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann, C. A., & Gerstorf, D. (2014). Biobehavioral pathways underlying spousal health dynamics: Its nature, correlates, and consequences. Gerontology, 60(5), 458–465. doi: 10.1159/000357671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann, C. A., & Gerstorf, D. (2016). Social interrelations in aging: The sample case of married couples. In Schaie K. W. & Willis S. L. (Eds.), Handbook of the Pyschology of Aging (8th ed., pp. 263–277). Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-411469-2.00014-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann, C. A., & Klumb, P. L. (2006). Daily goal pursuits predict cortisol secretion and mood states in employed parents with preschool children. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(6), 887–894. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238232.46870.f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann, C. A., Poetter, U., & Klumb, P. L. (2013). Dyadic conflict in goal-relevant activities affects well-being and psychological functioning in employed parents: Evidence from daily time-samples. Time & Society, 22, 356–370. doi: 10.1177/0961463X11413195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubiak, B. K., & Feeney, B. C. (2016). Daily goal progress is facilitated by spousal support and promotes psychological, physical, and relational well-being throughout adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 317–340. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubiak, B. K., Feeney, B. C., & Ferrer, R. A. (2020). Benefits of daily support visibility versus invisibility across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(5), 1018–1043. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko, H. J., Mejía, S., & Hooker, K. (2014). Social possible selves, self-regulation, and social goal progress in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 219–227. doi: 10.1177/0165025413512063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, N., & Rook, K. S. (2003). Negative interaction in late life: Issues in the stability and generalizability of conflict across relationships. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58, 88–99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.P88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau, J. P., & Bolger, N. (2005). Using diary methods to study marital and family processes. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(1), 86–97. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little, B. R. (1983). Personal projects: A rationale and method for investigation. Environment and Behavior, 15, 273–309. doi: 10.1177/0013916583153002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little, B. R. (2008). Personal projects and free traits: Personality and motivation reconsidered. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1235–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00106.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luong, G., Charles, S. T., & Fingerman, K. L. (2011). Better with age: Social relationships across adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(1), 9–23. doi: 10.1177/0265407510391362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margrett, J. A., & Marsiske, M. (2002). Gender differences in older adults’ everyday cognitive collaboration. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(1), 45–59. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, S. T., & Hooker, K. (2013). Relationship processes within the social convoy: Structure, function, and social goals. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(3), 376–386. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, S., & Schielzeth, H. (2013). A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4, 133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, T., Michalowski, V. I., Nater, U. M., Gerstorf, D., Ashe, M. C., Madden, K. M., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2019). Everyday associations between older adults’ physical activity, negative affect, and cortisol. Health Psychology, 38, 494–501. doi: 10.1037/hea0000743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, G. R. (1994). The quality of relationships inventory: Assessing the interpersonal context of social support. In Burleson B. R., lbrecht T. L., & Sarason I. G. (Eds.), Communication of social support: Messages, interactions, relationships, and community (pp. 247–266). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rauers, A., Riediger, M., Schmiedek, F., & Lindenberger, U. (2011). With a little help from my spouse: Does spousal collaboration compensate for the effects of cognitive aging? Gerontology, 57(2), 161–166. doi: 10.1159/000317335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger, M., Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2005). Managing life through personal goals: Intergoal facilitation and intensity of goal pursuit in younger and older adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(2), P84–P91. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.p84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmela-Aro, K., Nurmi, J. E., Saisto, T., & Halmesmäki, E. (2000). Women’s and men’s personal goals during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(2), 171–186. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler, I. C., Hoppmann, C., & Hooker, K. (2010). Personality: Life span compass for health. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30, 201–232. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.30.201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, J. M., Feeney, B. C., & Van Vleet, M. (2016). A longitudinal investigation of relational catalyst support of goal strivings. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 246–257. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1048815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, N., Michalowski, V., Baehring, S., Gerstorf, D., Ashe, M. C., Madden, K. M. & Hoppmann, C. A. (2021). Joint goals in older couples – associations with goal progress, allostatic load, and relationship satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology 12, 1014. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowels, L. M., & Carnelley, K. B. (2021). Attachment styles, negotiation of goal conflict, and perceived partner support during COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences. 171, 110505. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky, R. (1983). Planning and understanding: A computational approach to human reasoning. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. Advanced Book Program. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B. A. (2000). Compensating for cognitive deficits following brain injury. Neuropsychology Review, 10(4), 233–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1026464827874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.