This comparative effectiveness research study examines the long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients who use diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia medications.

Key Points

Question

What is the long-term incidence of medication discontinuation and restart associated with sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in patients with obesity-related comorbidities?

Findings

In this comparative effectiveness research study of 95 405 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, gastric bypass was associated with a slightly higher incidence of discontinuing diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia medication up to 5 years after surgery, compared with sleeve gastrectomy. Patients who underwent gastric bypass also had a lower incidence of medication restart for all 3 medication classes.

Meaning

These findings suggest that, after bariatric surgery, patients who had gastric bypass may be more likely to remain free of obesity-related medications compared with those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy.

Abstract

Importance

Sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass are the most common bariatric surgical procedures in the world; however, their long-term medication discontinuation and comorbidity resolution remain unclear.

Objective

To compare the incidence of medication discontinuation and restart of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia medications up to 5 years after sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This comparative effectiveness research study of adult Medicare beneficiaries who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass between January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2018, and had a claim for diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia medication in the 6 months before surgery with a corresponding diagnosis used instrumental-variable survival analysis to estimate the cumulative incidence of medication discontinuation and restart. Data analyses were performed from February to June 2021.

Exposures

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was discontinuation of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia medication for any reason. Among patients who discontinued medication, the adjusted cumulative incidence of restarting medication was calculated up to 5 years after discontinuation.

Results

Of the 95 405 patients included, 71 348 (74.8%) were women and the mean (SD) age was 56.6 (11.8) years. Gastric bypass compared with sleeve gastrectomy was associated with a slightly higher 5-year cumulative incidence of medication discontinuation among 30 588 patients with diabetes medication use and diagnosis at the time of surgery (74.7% [95% CI, 74.6%-74.9%] vs 72.0% [95% CI, 71.8%-72.2%]), 52 081 patients with antihypertensive medication use and diagnosis at the time of surgery (53.3% [95% CI, 53.2%-53.4%] vs 49.4% [95% CI, 49.3%-49.5%]), and 35 055 patients with lipid-lowering medication use and diagnosis at the time of surgery (64.6% [95% CI, 64.5%-64.8%] vs 61.2% [95% CI, 61.1%-61.3%]). Among the subset of patients who discontinued medication, gastric bypass was also associated with a slightly lower incidence of medication restart up to 5 years after discontinuation. Specifically, the 5-year cumulative incidence of medication restart was lower after gastric bypass compared with sleeve gastrectomy among 19 599 patients who discontinued their diabetes medication after surgery (30.4% [95% CI, 30.2%-30.5%] vs 35.6% [95% CI, 35.4%-35.9%]), 21 611 patients who discontinued their antihypertensive medication after surgery (67.2% [95% CI, 66.9%-67.4%] vs 70.6% [95% CI, 70.3%-70.9%]), and 18 546 patients who discontinued their lipid-lowering medication after surgery (46.2% [95% CI, 46.2%-46.3%] vs 52.5% [95% CI, 52.2%-52.7%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this study suggest that, compared with sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass was associated with a slightly higher incidence of medication discontinuation and a slightly lower incidence of medication restart among patients who discontinued medication. Long-term trials are needed to explain the mechanisms and factors associated with differences in medication discontinuation and comorbidity resolution after bariatric surgery.

Introduction

Sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass are the 2 most commonly performed surgical procedures for severe obesity.1,2,3 Studies that evaluated the comparative safety of these 2 procedures have suggested that sleeve gastrectomy has a superior short-term and long-term safety profile after surgery. Specifically, patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy have a lower incidence of interventions, operations, and hospitalizations compared with patients who underwent gastric bypass.4,5,6,7

Although the incidence of adverse events after sleeve gastrectomy appears to be lower than after gastric bypass, differences in long-term comorbidity resolution remain unclear. Both procedures have been shown in randomized clinical trials to have similar weight loss outcomes up to 5 years after surgery.8,9 Although gastric bypass may be associated with a slightly higher rate of diabetes remission, sleeve gastrectomy was also found in multiple studies to have durable diabetes remission.10,11 Other studies have suggested that gastric bypass may be associated with superior hypertension and hyperlipidemia resolution; however, these studies were limited by their small sample size.12 Even less is known regarding comparative outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries among whom obesity and bariatric surgery are increasingly common, but evidence to inform decision-making is lacking.13,14,15 Informed surgical decision-making requires understanding the differences in obesity-related outcomes of these procedures.16

Within this context, we conducted the current study to assess the long-term comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. Specifically, we evaluated the incidence of medication discontinuation for 3 major obesity-related diseases (diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) among Medicare beneficiaries with corresponding diagnoses at the time of surgery. We also examined the incidence of medication restart of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia medications after discontinuation to assess the durability of medication discontinuation. We hypothesized that both procedures would have substantial long-term medication discontinuation but that gastric bypass would offer more durable medication discontinuation given the evidence suggesting its superiority.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This comparative effectiveness research study used 100% fee-for-service Medicare (Part A, Part B, Part D) claims for bariatric surgery in patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2018. This study was deemed exempt from regulation and the informed consent requirement was waived by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board because the study used deidentified administrative claims data. We followed the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) reporting guideline.

Patients with morbid obesity were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes. Appropriate Current Procedural Terminology as well as ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were used to identify patients who had sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of gastric or small bowel cancer, if they did not have 3-month continuous Medicare enrollment before their index admission, or if their Medicare entitlement was obtained because of their end-stage kidney disease.

We identified 3 study cohorts using the following criteria: (1) diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia before index admission (eTable 1 in the Supplement), and (2) at least 1 related pharmacy claim for a diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia drug before index admission (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The purpose of using both inclusion criteria was to avoid identifying patients who may be using these medications for other indications, such as antihypertensive medication for migraine. Drug claims were queried up to 6 months before index admission because refills of 90 or more days may fall outside the 3-month inclusion window. Because patients may use multiple medications, the same patient could be counted in more than 1 cohort.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was discontinuation of all diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia medications for any reason. Medication discontinuation was defined as at least a 6-month lapse in claims for a medication refill after the previous medication fill. This definition was based on previously validated methods for identifying medication discontinuation in administrative data.17,18

The secondary outcome was restart of medication after discontinuation for each medication class. Medication restart was defined as a pharmacy claim for the relevant medication class after discontinuation. This definition was consistent with that used in previous studies wherein the rates of relapse or recurrence were calculated only among patients who first achieved remission.19,20,21 The time of medication restart was calculated from the last fill for that medication plus when that medication would have been expected to run out.

Instrumental Variable Assumptions

The instrumental variable was previous-year state-level sleeve gastrectomy rate, which has been used in other studies.5,6,7 In June 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began coverage of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for treatment of severe obesity.22 After this coverage decision, the rate of sleeve gastrectomy uptake in Medicare beneficiaries varied geographically. This variation created the opportunity for a natural experiment in which treatment choice largely depended on whether a patient lived in a region with high or low sleeve gastrectomy utilization, similar to other studies that have used geographic variation as an instrumental variable.23

For an instrumental variable to be valid, it must meet 2 conditions. First, it must be associated with treatment. This condition is assessed with the F statistic; an F statistic that is greater than 10 signifies a strong association.24,25 In the current study, the F statistic of the previous-year state-level sleeve gastrectomy rate was 605.3 for the diabetes cohort, 924.5 for the hypertension cohort, and 769.1 for the hyperlipidemia cohort.

Second, a valid instrumental variable must not be associated with the outcome except through treatment; that is, there should be no mutual confounders between the instrument and the outcome. Although this condition cannot be empirically evaluated, lagged treatment patterns meet this condition because they reflect comorbidities and care decisions among different sets of patients.26 Moreover, we found that patient characteristics and comorbidities were well balanced using this instrumental variable (eTables 3-5 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for age, sex, race and ethnicity, comorbidities, and year of operation. Race and ethnicity were identified in the Medicare claims database and were used in this study because bariatric surgery outcomes have been found to differ by race and ethnicity. Race and ethnicity categories included Asian, Black, Hispanic, North American Native, White, other, and unknown; no additional details were available for the other category.

Univariate statistics were calculated using the χ2 test or an unpaired, 2-tailed t test. The primary analysis of this study used a 2-stage modeling approach to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and cumulative incidence of medication discontinuation and restart after each procedure.27,28,29 This 2-stage residual inclusion estimation method has been shown to result in more consistent estimates of nonlinear outcomes.30,31

In the first stage of analysis, we performed logistic regression to estimate a patient’s likelihood of undergoing sleeve gastrectomy using the following covariates: previous-year state-level sleeve gastrectomy rate (the instrumental variable), age, sex, race and ethnicity, comorbidities, and year of surgery, all of which were associated with bariatric surgical outcomes.29,32 In the second stage, we constructed a Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the aHR and cumulative incidence of outcomes using the following covariates: treatment (gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy), age, sex, race and ethnicity, comorbidities, year of surgery, and residuals from the first-stage regression model, which represented unobserved confounders associated with treatment choice. Calibration of this model was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals, which revealed a violation of the proportional hazards assumption. Violation of this assumption indicates that the treatment effect is time variant and thus there is not a consistent HR for the entire study period.33

Accordingly, the covariates in this model were interacted with time, and aHRs at 1-, 3-, and 5-year time points were presented for each outcome, which represented the ratio of outcomes at each time point. In addition, aHRs without instrumental variable adjustment were calculated (eTables 7-8 in the Supplement). The cumulative incidence of each outcome, which represented the incidence of outcomes up to each time point, was then calculated from the Cox proportional hazards regression model and the covariates were held at their mean value. Patients were censored if they died, disenrolled from Medicare, or reached the end of the study period, and the primary outcome could be reached in less than 180 postoperative days if the last medication fill occurred before surgery.

All multivariable regression analyses accounted for clustering at the state level, and robust SEs were used to account for state-level heteroscedasticity. Statistical tests were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC). Tests were 2-sided, and significance was set at P < .05. Data analyses were performed from February to June 2021.

Results

A total of 95 405 patients were included in this analysis, of whom 71 348 (74.8%) were women and 24 057 (25.2%) were men with a mean (SD) age of 56.6 (11.8) years. From these patients, 3 cohorts were generated according to diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia medication use and diagnosis at the time of surgery; medication discontinuation was also calculated for these cohorts (Table 1). Rates of medication restart were then calculated among the 59 756 patients who discontinued medication (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the 3 Study Cohortsa.

| Characteristic | Diabetes cohort, No. (%) | Hypertension cohort, No. (%) | Hyperlipidemia cohort, No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGB (n = 13 779) | SL (n = 16 809) | P value | RYGB (n = 20 955) | SL (n = 31 126) | P value | RYGB (n = 14 401) | SL (n = 20 654) | P value | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.3 (10.9) | 57.8 (10.9) | <.001 | 56.42 (11.1) | 58.06 (11.1) | <.001 | 57.8 (10.4) | 59.55 (10.3) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 10 010 (72.7) | 11 781 (70.1) | <.001 | 15 765 (75.2) | 22 759 (73.1) | <.001 | 10 567 (73.4) | 14 602 (70.7) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 3769 (27.3) | 5028 (29.9) | 5190 (24.8) | 8367 (26.9) | 3834 (26.6) | 6052 (29.3) | |||

| Race and ethnicityb | |||||||||

| Asian | 44 (0.3) | 47 (0.3) | .005 | 53 (0.3) | 67 (0.2) | <.001 | 43 (0.3) | 52 (0.3) | .02 |

| Black | 2325 (16.9) | 3055 (18.2) | 3857 (18.4) | 6115 (19.7) | 2110 (14.7) | 3081 (14.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 559 (4.1) | 705 (4.2) | 680 (3.3) | 1026 (3.3) | 457 (3.2) | 645 (3.1) | |||

| North American Native | 106 (0.8) | 97 (0.6) | 141 (0.7) | 151 (0.5) | 86 (0.6) | 91 (0.4) | |||

| White | 10 457 (75.9) | 12 548 (74.7) | 15 848 (75.6) | 23 126 (74.3) | 11 422 (79.3) | 16 345 (79.1) | |||

| Otherc | 141 (1.0) | 144 (0.9) | 178 (0.9) | 233 (0.8) | 133 (0.9) | 161 (0.8) | |||

| Unknown | 147 (1.1) | 213 (1.3) | 198 (0.9) | 408 (1.3) | 150 (1.0) | 279 (1.4) | |||

| Year of operation | |||||||||

| 2012 | 2849 (20.7) | 139 (0.8) | <.001 | 4304 (20.5) | 212 (0.7) | <.001 | 2850 (19.8) | 152 (0.7) | <.001 |

| 2013 | 2401 (17.4) | 2025 (12.1) | 3613 (17.2) | 3507 (11.3) | 2492 (17.3) | 2413 (11.7) | |||

| 2014 | 2127 (15.4) | 2734 (16.3) | 3199 (15.3) | 4917 (15.8) | 2199 (15.3) | 3264 (15.8) | |||

| 2015 | 1912 (13.9) | 2950 (17.6) | 2857 (13.6) | 5607 (18.0) | 1995 (13.9) | 3675 (17.8) | |||

| 2016 | 1668 (12.1) | 3144 (18.7) | 2554 (12.2) | 5834 (18.7) | 1786 (12.4) | 3943 (19.1) | |||

| 2017 | 1599 (11.6) | 3226 (19.2) | 2403 (11.5) | 6068 (19.5) | 1701 (11.8) | 4077 (19.7) | |||

| 2018 | 1223 (8.9) | 2591 (15.4) | 2025 (9.7) | 4981(16.0) | 1378 (9.6) | 3130 (15.2) | |||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| AIDS | 11 (0.1) | 26 (0.2) | .06 | 25 (0.1) | 65 (0.2) | .02 | 21 (0.2) | 42 (0.2) | .21 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 30 (0.2) | 23 (0.1) | .09 | 47 (0.2) | 43 (0.1) | .02 | 27 (0.2) | 30 (0.2) | .33 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 4019 (29.2) | 4833 (28.8) | .42 | 6240 (29.8) | 8725 (28.0) | <.001 | 4198 (29.2) | 5661 (27.4) | .001 |

| Coagulopathy | 142 (1.0) | 145 (0.9) | .13 | 198 (0.9) | 265 (0.9) | .26 | 135 (0.9) | 179 (0.9) | .48 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1106 (8.0) | 1586 (9.4) | <.001 | 1634 (7.8) | 2648 (8.5) | .004 | 1144 (7.9) | 1805 (8.7) | .008 |

| Deficiency anemias | 985 (7.2) | 1185 (7.1) | .74 | 1439 (6.9) | 1992 (6.4) | .04 | 941 (6.5) | 1224 (5.9) | .02 |

| Depression | 3954 (28.7) | 4192 (24.9) | <.001 | 6235 (29.8) | 8089 (26.0) | <.001 | 4302 (29.9) | 5366 (26.0) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| With chronic complications | NA | NA | NA | 2740 (13.1) | 3541 (11.4) | <.001 | 2255 (15.7) | 2846 (13.8) | <.001 |

| Without chronic complications | NA | NA | NA | 10 318 (49.2) | 12 723 (40.9) | <.001 | 7899 (54.9) | 9669 (46.8) | <.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1033 (7.5) | 1090 (6.5) | .001 | 1486 (7.1) | 1866 (6.0) | <.001 | 979 (6.8) | 1250 (6.1) | .005 |

| Hypertension | 11 582 (84.1) | 14 147 (84.2) | .80 | NA | NA | NA | 12 044 (83.6) | 17 238 (83.5) | .66 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2453 (17.8) | 3088 (18.4) | .20 | 3687 (17.6) | 5577 (17.9) | .34 | 2696 (18.7) | 3974 (19.2) | .22 |

| Liver disease | 2331 (16.9) | 2545 (15.1) | <.001 | 3177 (15.2) | 4079 (13.1) | <.001 | 2207 (15.3) | 2634 (12.8) | <.001 |

| Lymphoma | 8 (0.1) | 21 (0.1) | .06 | 15 (0.1) | 45 (0.1) | .02 | 6 (0.0) | 26 (0.1) | .01 |

| Other neurological disorders | 714 (5.2) | 829 (4.9) | .32 | 1148 (5.5) | 1613 (5.2) | .14 | 797 (5.5) | 1096 (5.3) | .35 |

| Paralysis | 73 (0.5) | 106 (0.6) | .25 | 112 (0.5) | 179 (0.6) | .54 | 75 (0.5) | 135 (0.7) | .11 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 300 (2.2) | 356 (2.1) | .72 | 432 (2.1) | 584 (1.9) | .13 | 337 (2.3) | 445 (2.2) | .24 |

| Psychoses | 1042 (7.6) | 1050 (6.3) | <.001 | 1531 (7.3) | 1759 (5.7) | <.001 | 1074 (7.5) | 1206 (5.8) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 196 (1.4) | 157 (0.9) | <.001 | 281 (1.3) | 265 (0.9) | <.001 | 186 (1.3) | 176 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Kidney failure | 1197 (8.7) | 1631 (9.7) | .002 | 1574 (7.5) | 2378 (7.6) | .58 | 1195 (8.3) | 1767 (8.6) | .39 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease | 480 (3.5) | 599 (3.6) | .71 | 826 (3.9) | 1390 (4.5) | .004 | 501 (3.5) | 778 (3.8) | .16 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 37 (0.3) | 49 (0.3) | .71 | 50 (0.2) | 88 (0.3) | .34 | 37 (0.3) | 58 (03) | .67 |

| Malnutrition | 67 (0.5) | 45 (0.3) | .002 | 91 (0.4) | 89 (0.3) | .005 | 71 (0.5) | 54 (0.3) | <.001 |

| Valvular disease | 247 (1.8) | 338 (2.0) | .17 | 417 (2.0) | 701 (2.3) | .04 | 281 (2.0) | 489 (2.4) | .009 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SL, sleeve gastrectomy.

Three separate cohorts were identified based on medication use and corresponding diagnosis at the time of surgery. Because patients may be using more than 1 medication class, the same patient could be counted in more than 1 cohort.

Race and ethnicity data were identified in the Medicare claims database.

No additional details were available in the Medicare claims database for the other race and ethnicity category.

Diabetes

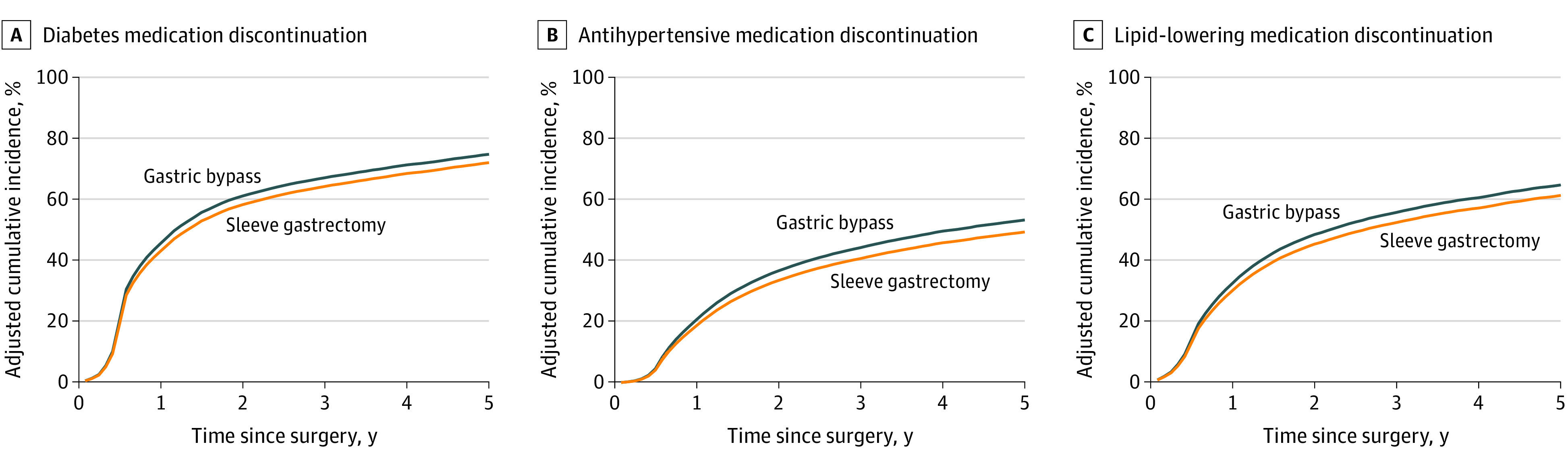

For the 30 588 patients in the diabetes cohort, the median (IQR) follow-up time was 307 (160-795) days for 16 809 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy and 260 (158-702) days for 13 779 patients who underwent gastric bypass. Patients who underwent gastric bypass were more likely to discontinue diabetes medication up to 5 years after surgery compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (aHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.12-1.51) (Table 2). This result corresponded to an adjusted 5-year cumulative incidence of diabetes medication discontinuation of 74.7% (95% CI, 74.6%-74.9%) for the gastric bypass group vs 72.0% (95% CI, 71.8%-72.2%) for the sleeve gastrectomy group (Figure 1A).

Table 2. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Discontinuation of Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications at 1, 3, or 5 Years After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs Sleeve Gastrectomy.

| Outcomea | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 3 y | 5 y | |

| Diabetes medication discontinuation | 1.19 (1.05-1.34) | 1.26 (1.10-1.45) | 1.30 (1.12-1.51) |

| Antihypertensive medication discontinuation | 1.28 (1.17-1.41) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) | 1.31 (1.18-1.45) |

| Lipid-lowering medication discontinuation | 1.28 (1.16-1.40) | 1.10 (0.99-1.22) | 1.03 (0.92-1.15) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Medication discontinuation was defined as at least a 6-month lapse in claims for a medication refill after the previous medication fill. Outcomes were calculated among 30 588 patients with diabetes diagnosis and medication use, 52 081 patients with hypertension diagnosis and medication use, and 35 055 patients with hyperlipidemia diagnosis and medication use.

Adjusted HRs were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models, which included treatment, age, sex, race and ethnicity, year of surgery, comorbidities, and previous-year sleeve gastrectomy rate as an instrumental variable and were interacted with time.

Figure 1. Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Discontinuation of Diabetes, Antihypertensive, and Lipid-Lowering Medications After Surgery .

A, Discontinuation was calculated among 30 588 patients with diabetes diagnosis and medication use at the time of surgery. B, Discontinuation was calculated among 52 081 patients with hypertension diagnosis and medication use at the time of surgery. C, Discontinuation was calculated among 35 055 patients with hyperlipidemia diagnosis and medication use at the time of surgery.

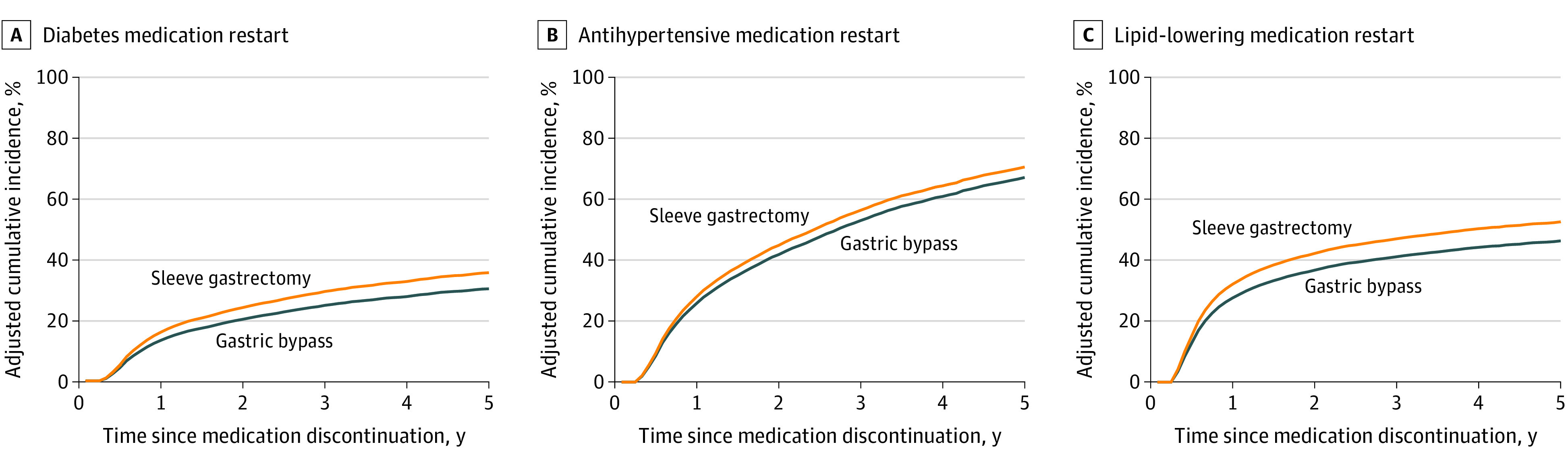

Among the 19 599 patients who discontinued diabetes medication, those who underwent gastric bypass had a lower likelihood of restarting medication up to 5 years after discontinuation (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63-0.96) (Table 3). This result corresponded to an adjusted cumulative incidence of diabetes medication restart of 30.4% (95% CI, 30.2%-30.5%) for the gastric bypass group vs 35.6% (95% CI, 35.4%-35.9%) for the sleeve gastrectomy group 5 years after medication discontinuation (Figure 2A). The median (IQR) duration of diabetes medication discontinuation among patients who discontinued medication was 866 (336-1587) days for patients in the gastric bypass group and 578 (244-1109) days for patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P < .001).

Table 3. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Restarting Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications at 1, 3, or 5 Years After Medication Discontinuation After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs Sleeve Gastrectomy.

| Outcomea | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 3 y | 5 y | |

| Diabetes medication restart | 0.69 (0.60-0.78) | 0.75 (0.63-0.89) | 0.78 (0.63-0.96) |

| Antihypertensive medication restart | 0.81 (0.73-0.89) | 0.90 (0.79-1.01) | 0.94 (0.82-1.08) |

| Lipid-lowering medication restart | 0.53 (0.47-0.60) | 0.46 (0.40-0.53) | 0.44 (0.38-0.50) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Medication restart was defined as a pharmacy claim for the relevant medication class after discontinuation. Outcomes were calculated among 19 599 patients who discontinued all diabetes medications, 21 611 patients who discontinued all hypertension medications, and 18 546 patients who discontinued all hyperlipidemia medications.

Adjusted HRs were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models, which included treatment, age, sex, race and ethnicity, year of surgery, comorbidities, and previous-year sleeve gastrectomy rate as an instrumental variable and were interacted with time.

Figure 2. Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Restart of Diabetes, Antihypertensive, and Lipid-Lowering Medications After Discontinuation.

A, Restart was calculated among 19 599 patients who discontinued all diabetes medication after surgery. B, Restart was calculated among 21 611 patients who discontinued all antihypertensive medications after surgery. C, Restart was calculated among 18 546 patients who discontinued all lipid-lowering medications after surgery.

Hypertension

For the 52 081 patients in the hypertension cohort, the median (IQR) follow-up time was 545 (250-1091) days for 31 126 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy and 613 (265-1349) days for 20 955 patients who underwent gastric bypass. Patients who underwent gastric bypass were more likely to discontinue antihypertensive medication up to 5 years after surgery (aHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.18-1.45) (Table 2). This finding corresponded to an adjusted 5-year cumulative incidence of antihypertensive medication discontinuation of 53.3% (95% CI, 53.2%-53.4%) for the gastric bypass group vs 49.4% (95% CI, 49.3%-49.5%) for the sleeve gastrectomy group (Figure 1B).

Among the 21 611 patients who discontinued antihypertensive medication, those who underwent gastric bypass had a lower likelihood of restarting medication at 1 year after discontinuation (aHR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73-0.89), but the difference became nonsignificant at 3 and 5 years (Table 3). This result corresponded to an adjusted cumulative incidence of antihypertensive medication restart of 67.2% (95% CI, 66.9%-67.4%) for the gastric bypass group vs 70.6% (95% CI, 70.3%-70.9%) for the sleeve gastrectomy group 5 years after medication discontinuation (Figure 2B). The median (IQR) duration of antihypertensive medication discontinuation among patients who discontinued medication was 410 (191-975) days for patients in the gastric bypass group and 338 (177-740) days for patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P < .001).

Hyperlipidemia

For the 35 055 patients in the hyperlipidemia cohort, the median (IQR) follow-up time was 487 (218-963) days for 20 654 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy and 419 (172-1006) days for 14 401 patients who underwent gastric bypass. Patients who underwent gastric bypass were more likely to discontinue lipid-lowering medication at 1 year after surgery (aHR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.16-1.40), but this became nonsignificant at 3 and 5 years (Table 2). This finding corresponded to an adjusted 5-year cumulative incidence of hyperlipidemia medication discontinuation of 64.6% (95% CI, 64.5%-64.8%) for the gastric bypass group vs 61.2% (95% CI, 61.1%-61.3%) for the sleeve gastrectomy group (Figure 1C).

Among the 18 546 patients who discontinued lipid-lowering medication, those who underwent gastric bypass had a lower likelihood of restarting medication up to 5 years after surgery (aHR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.38-0.50) (Table 3). This finding corresponded to an adjusted cumulative incidence of lipid-lowering medication restart of 46.2% (95% CI, 46.2%-46.3%) for the gastric bypass group vs 52.5% (95% CI, 52.2%-52.7%) for the sleeve gastrectomy group 5 years after medication discontinuation (Figure 2C). The median (IQR) duration of lipid-lowering medication discontinuation among patients who discontinued medication was 647 (222-1413) days for patients in the gastric bypass group and 345 (170-815) days for patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P < .001).

Discussion

This comparative effectiveness research study of patients using medications for obesity-related comorbidities at the time of bariatric surgery presents 3 key findings. First, both gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy were associated with a high incidence of medication discontinuation up to 5 years after surgery. Second, the durability of medication discontinuation differed across chronic conditions, with diabetes medications having the highest incidence of discontinuation and the lowest incidence of restart compared with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications. Third, for all comorbidities examined, gastric bypass was associated with a slightly higher incidence of medication discontinuation and a slightly lower incidence of medication restart compared with sleeve gastrectomy. Overall, we believe these results suggest that both procedures are associated with long-term improved outcomes enabling obesity-related medication discontinuation and suggest that patients who underwent gastric bypass may be slightly more likely to remain off of medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia after surgery compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy.

The benefits of bariatric surgery for obesity-related medication discontinuation are well established.34,35,36,37 For example, Segal et al38 found that, among privately insured patients who had bariatric surgery, 1-year discontinuation rates were 76% for diabetes medication, 59% for lipid-lowering medication, and 51% for antihypertensive medication. The current study, which investigated long-term medication discontinuation in Medicare beneficiaries, found nearly identical patterns of long-term discontinuation rates, with diabetes medication having the highest incidence of discontinuation, followed by lipid-lowering medication and antihypertensive medication. Corroborating these patterns among Medicare patients is important given that since 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass for Medicare beneficiaries; however, there has been a lack of long-term comparative effectiveness studies in this population.15,39 The current study adds evidence to the literature regarding the overall and comparative improvement in outcomes associated with these 2 procedures among Medicare beneficiaries. Moreover, given the similarities in safety, effectiveness, and patterns of utilization between studies involving Medicare beneficiaries and those involving privately insured individuals, the results of the current study are likely generalizable to the broader population of patients with obesity and obesity-related comorbidities.5,6,11

This study also offers insight into the differing effect size and durability of medication discontinuation after bariatric surgery. For example, the overall incidence of medication discontinuation was highest for diabetes medication and lowest for antihypertensive medication in both groups. This result is consistent with results of previous work, such as the Swedish Obese Subjects study, which found that patients with diabetes derived the greatest benefit from bariatric surgery compared with patients with other comorbidities.40 Alternatively, the improved outcomes associated with these procedures differed by comorbid health condition. The difference in discontinuation rates between procedures was greatest for antihypertensive medication and smallest for diabetes medication. Again, previous work has demonstrated that the overall benefit of bariatric surgery may be greatest for patients with diabetes, but the biggest difference between procedures is greatest for patients with hypertension.41 Differences were also observed for medication restarts among the subset of patients who initially discontinued medication use. Although diabetes medication had the lowest incidence of medication restarts, lipid-lowering medications had the greatest difference in restart rate between the 2 procedures.

Compared with the high rates of medication discontinuation after both procedures, the difference between procedures was marginal. This finding is consistent with the results of a number of studies that demonstrated relatively similar improvements in weight loss and comorbidities after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy.42,43 Insofar as all 3 conditions are strongly associated with body weight, similarities in medication discontinuation between these procedures may be associated with their similar weight loss outcomes.44 It is also possible that the slight superiority of gastric bypass reflects the differences in the underlying mechanisms of these operations. For example, gastric bypass has been found to be associated with superior diabetes remission compared with sleeve gastrectomy because of the gut hormonal changes and reduced insulin resistance after both gastric restriction and duodenal exclusion as opposed to gastric restriction alone.45 Similarly, insofar as blood pressure and lipid levels are associated with total body weight, the small differences in medication discontinuation for these 2 conditions may be associated with differential weight loss between gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy.46 However, these small differences could also be associated with factors unrelated to weight loss or comorbidity resolution, such as oral medication tolerance, lifestyle modification, or even medication management. These results should be interpreted within the broader evidence regarding these 2 procedures, and the slight superiority of gastric bypass should be weighed against the comparative safety of sleeve gastrectomy.7 Long-term prospective trials of outcomes after bariatric surgery are needed to explain the mechanisms and factors associated with the differences in medication discontinuation and comorbidity resolution.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the generalizability of these results may be limited by the use of fee-for-service Medicare claims data, which did not include privately insured individuals or managed Medicare beneficiaries who differed in the incidence of obesity-related comorbidities and medication use.47,48 However, it is crucial to understand the comparative effectiveness of bariatric surgery in a Medicare population, and results from this study may be relatively generalizable given the similarities in bariatric surgery utilization between publicly and privately insured individuals.49 Second, the definition of medication discontinuation relied on an arbitrary window of time in which no medication claims were observed. Administrative claims data also lack granular detail on actual medication use. For example, patients who were prescribed a medication then given different instructions of use would interfere with our estimations. However, the discontinuation definition we used was based on a previously validated method that is highly sensitive to capturing actual medication discontinuation and not misidentifying temporary lapses in refill as discontinuation.17 Although we calculated the incidence of medication restart among patients who discontinued medication, it is equally important to understand medication changes among patients who do not entirely discontinue their medications after surgery. Third, medication discontinuation does not necessarily imply comorbidity resolution in this cohort. It is possible that patients who underwent gastric bypass developed a greater intolerance to oral medications, resulting in less medication use without comorbidity resolution. Although the patterns observed in this study are consistent with those in previous studies that directly measured comorbidity resolution using laboratory values such as hemoglobin A1c and lipid levels, future work is needed to ascertain the long-term changes in underlying comorbidities. Fourth, despite its use of an instrumental variable, this study was still subject to residual bias. Between-group differences in mortality, Medicare disenrollment, and even medication compliance may confound the observed outcomes. The large sample size of this study also increased the likelihood of type I error. Despite these limitations, the large sample size and use of econometric techniques to control for confounding mitigated the degree to which the study’s observational design biased the results.

Conclusions

In this comparative effectiveness research study with a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with a high burden of medication use for obesity-associated diseases, both gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy were associated with a high incidence of medication discontinuation up to 5 years after surgery. Compared with sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass was associated with a slightly higher incidence of medication discontinuation and a slightly lower incidence of medication restart after discontinuation. Overall, we believe these results demonstrate that both procedures are associated with long-term discontinuation of obesity-related medication and suggest that patients who underwent gastric bypass may be slightly more likely to remain free from their diabetes, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering medications. Long-term prospective trials are needed to explain the mechanisms and factors associated with the differences in medication discontinuation and comorbidity resolution after bariatric surgery.

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes Used to Identify Study Cohorts

eTable 2. Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications Used to Identify Study Cohorts

eTable 3. Covariate Balance Using Instrumental Variable for Cohort of Patients With Diabetes Medication Use and Diagnosis at the Time of Surgery

eTable 4. Covariate Balance Using Instrumental Variable for Cohort of Patients With Hypertension Medication Use and Diagnosis at the Time of Surgery

eTable 5. Covariate Balance Using Instrumental Variable for Cohort of Patients With Hyperlipidemia Medication Use and Diagnosis at the Time of Surgery

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Discontinued All Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications After Surgery and Among Whom the Incidence of Medication Restart Was Calculated

eTable 7. Adjusted Hazard Ratios Without Use of the Instrumental Variable for Discontinuation of Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications at 1, 3, and 5 Years After Gastric Bypass Compared to Sleeve Gastrectomy

eTable 8. Adjusted Hazard Ratios Without Use of the Instrumental Variable for Restarting Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications at 1, 3, and 5 Years After Medication Discontinuation Following Gastric Bypass Compared to Sleeve Gastrectomy

References

- 1.Campos GM, Khoraki J, Browning MG, Pessoa BM, Mazzini GS, Wolfe L. Changes in utilization of bariatric surgery in the United States from 1993 to 2016. Ann Surg. 2020;271(2):201-209. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.English WJ, DeMaria EJ, Brethauer SA, Mattar SG, Rosenthal RJ, Morton JM. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States in 2016. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):259-263. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alalwan AA, Friedman J, Park H, Segal R, Brumback BA, Hartzema AG. US national trends in bariatric surgery: a decade of study. Surgery. 2021;170(1):13-17. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcoulas A, Coley RY, Clark JM, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative . Interventions and operations 5 years after bariatric surgery in a cohort from the US National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network Bariatric Study. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(3):194-204. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhabra KR, Telem DA, Chao GF, et al. Comparative safety of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: an instrumental variables approach. Ann Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao GF, Chhabra KR, Yang J, et al. Bariatric surgery in Medicare patients: examining safety and healthcare utilization in the disabled and elderly. Ann Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard R, Chao GF, Yang J, et al. Comparative safety of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass up to 5 years after surgery in patients with severe obesity. JAMA Surg. 2021. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.4981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(3):255-265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(3):241-254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. ; STAMPEDE Investigators . Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641-651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McTigue KM, Wellman R, Nauman E, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative . Comparing the 5-year diabetes outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet) Bariatric Study. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5):e200087. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Climent E, Goday A, Pedro-Botet J, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for 5-year hypertension remission in obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2020;38(2):185-195. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrick AT, Kuhn JE, Parker DM, Prasad J, Still C, Wood GC. Bariatric surgery is safe and effective in Medicare patients regardless of age: an analysis of primary gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(10):1704-1711. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doshi JA, Polsky D, Chang VW. Prevalence and trends in obesity among aged and disabled U.S. Medicare beneficiaries, 1997-2002. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(4):1111-1117. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . MEDCAC meeting: health outcomes after bariatric surgical therapies in the Medicare population. August 30, 2017. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/medcac-meeting-details.aspx?MEDCACId=74

- 16.Arterburn D, Gupta A. Comparing the outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for severe obesity. JAMA. 2018;319(3):235-237. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker MM, Moffet HH, Adams A, Karter AJ. An algorithm to identify medication nonpersistence using electronic pharmacy databases. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(5):957-961. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner JZ, Gopalan A, Mishra P, et al. Use and discontinuation of insulin treatment among adults aged 75 to 79 years with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1633-1641. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arterburn DE, Bogart A, Sherwood NE, et al. A multisite study of long-term remission and relapse of type 2 diabetes mellitus following gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2013;23(1):93-102. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0802-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. JAMA. 2014;311(22):2297-2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth JN III, Colantonio LD, Chen L, et al. Statin discontinuation, reinitiation, and persistence patterns among Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(10):e003626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . National Coverage Determination (NCD): bariatric surgery for treatment of co-morbid conditions related to morbid obesity. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=57

- 23.Valley TS, Sjoding MW, Ryan AM, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Association of intensive care unit admission with mortality among older patients with pneumonia. JAMA. 2015;314(12):1272-1279. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baiocchi M, Cheng J, Small DS. Instrumental variable methods for causal inference. Stat Med. 2014;33(13):2297-2340. doi: 10.1002/sim.6128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rassen JA, Brookhart MA, Glynn RJ, Mittleman MA, Schneeweiss S. Instrumental variables II: instrumental variable application-in 25 variations, the physician prescribing preference generally was strong and reduced covariate imbalance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(12):1233-1241. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hadley J, Yabroff KR, Barrett MJ, Penson DF, Saigal CS, Potosky AL. Comparative effectiveness of prostate cancer treatments: evaluating statistical adjustments for confounding in observational data. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(23):1780-1793. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birkmeyer NJ, Dimick JB, Share D, et al. ; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative . Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA. 2010;304(4):435-442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finks JF, Kole KL, Yenumula PR, et al. ; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, from the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy . Predicting risk for serious complications with bariatric surgery: results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Ann Surg. 2011;254(4):633-640. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318230058c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courcoulas AP, Yanovski SZ, Bonds D, et al. Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery: a National Institutes of Health symposium. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(12):1323-1329. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan HJ, Norton EC, Ye Z, Hafez KS, Gore JL, Miller DC. Long-term survival following partial vs radical nephrectomy among older patients with early-stage kidney cancer. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1629-1635. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. J Health Econ. 2008;27(3):531-543. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(5):427-434. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hess KR. Graphical methods for assessing violations of the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1995;14(15):1707-1723. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crémieux PY, Ledoux S, Clerici C, Cremieux F, Buessing M. The impact of bariatric surgery on comorbidities and medication use among obese patients. Obes Surg. 2010;20(7):861-870. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0163-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yska JP, van der Meer DH, Dreijer AR, et al. Influence of bariatric surgery on the use of medication. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(2):203-209. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1971-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiavon CA, Bhatt DL, Ikeoka D, et al. Three-year outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with obesity and hypertension: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):685-693. doi: 10.7326/M19-3781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yska JP, van der Linde S, Tapper VV, et al. Influence of bariatric surgery on the use and pharmacokinetics of some major drug classes. Obes Surg. 2013;23(6):819-825. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0882-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segal JB, Clark JM, Shore AD, et al. Prompt reduction in use of medications for comorbid conditions after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19(12):1646-1656. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9960-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panagiotou OA, Markozannes G, Adam GP, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of bariatric procedures in Medicare-eligible patients: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):e183326. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sjöström CD, Lissner L, Wedel H, Sjöström L. Reduction in incidence of diabetes, hypertension and lipid disturbances after intentional weight loss induced by bariatric surgery: the SOS Intervention Study. Obes Res. 1999;7(5):477-484. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lager CJ, Esfandiari NH, Luo Y, et al. Metabolic parameters, weight loss, and comorbidities 4 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018;28(11):3415-3423. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3346-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grönroos S, Helmiö M, Juuti A, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss and quality of life at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(2):137-146. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khalaj A, Tasdighi E, Hosseinpanah F, et al. Two-year outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy versus gastric bypass: first report based on Tehran Obesity Treatment Study (TOTS). BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12893-020-00819-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen NT, Magno CP, Lane KT, Hinojosa MW, Lane JS. Association of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome with obesity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(6):928-934. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee WJ, Chen CY, Chong K, Lee YC, Chen SC, Lee SD. Changes in postprandial gut hormones after metabolic surgery: a comparison of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(6):683-690. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lager CJ, Esfandiari NH, Subauste AR, et al. Roux-En-Y gastric bypass vs. sleeve gastrectomy: balancing the risks of surgery with the benefits of weight loss. Obes Surg. 2017;27(1):154-161. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2265-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park S, Larson EB, Fishman P, White L, Coe NB. Differences in health care utilization, process of diabetes care, care satisfaction, and health status in patients with diabetes in Medicare Advantage versus traditional Medicare. Med Care. 2020;58(11):1004-1012. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Souza J, Ayanian JZ. Use of diabetes medications in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(3):e80-e88. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2021.88602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altieri MS, Yang J, Yin D, Talamini MA, Spaniolas K, Pryor AD. Patients insured by Medicare and Medicaid undergo lower rates of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(12):2109-2114. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes Used to Identify Study Cohorts

eTable 2. Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications Used to Identify Study Cohorts

eTable 3. Covariate Balance Using Instrumental Variable for Cohort of Patients With Diabetes Medication Use and Diagnosis at the Time of Surgery

eTable 4. Covariate Balance Using Instrumental Variable for Cohort of Patients With Hypertension Medication Use and Diagnosis at the Time of Surgery

eTable 5. Covariate Balance Using Instrumental Variable for Cohort of Patients With Hyperlipidemia Medication Use and Diagnosis at the Time of Surgery

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Discontinued All Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications After Surgery and Among Whom the Incidence of Medication Restart Was Calculated

eTable 7. Adjusted Hazard Ratios Without Use of the Instrumental Variable for Discontinuation of Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications at 1, 3, and 5 Years After Gastric Bypass Compared to Sleeve Gastrectomy

eTable 8. Adjusted Hazard Ratios Without Use of the Instrumental Variable for Restarting Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia Medications at 1, 3, and 5 Years After Medication Discontinuation Following Gastric Bypass Compared to Sleeve Gastrectomy