Abstract

Evidence suggesting that high-grade serous ovarian cancers originate in the fallopian tubes has led to the emergence of opportunistic salpingectomy (OS) as an approach to reduce ovarian cancer risk. In the U.S., some national societies now recommend OS in place of tubal ligation for sterilization or during a benign hysterectomy in average-risk women. However, limited data exist on the adoption of OS in clinical practice. We examined the uptake and predictors of OS in a nationwide sample of inpatient and outpatient claims (N=48,231,235) from 2010-2017. Incidence rates of OS were calculated, and an interrupted time-series analysis was used to quantify changes in rates before (2010-2013) and after (2015-2017) national guideline release. Predictors of OS use were examined using Poisson regression. From 2010-2017, the age-adjusted incidence rate of OS for sterilization and OS during hysterectomy increased 17.8-fold (95% CI: 16.2-19.5) and 7.6-fold (95% CI: 5.5-10.4), respectively. The rapid increase (age-adjusted increase in quarterly rates of between 109% and 250%) coincided with the time of guideline release. In multivariable-adjusted analyses, OS use was more common in young women and varied significantly by geographic region, rurality, family history/genetic susceptibility, surgical indication, inpatient/outpatient setting, and underlying comorbidities. Similar differences in OS uptake were noted in analyses limited to women with a family history/genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer. Our results highlight significant differences in OS uptake in both high- and average-risk women. Defining subsets of women who would benefit most from OS and identifying barriers to equitable OS uptake is needed.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Risk-reducing surgery, Cancer prevention, Salpingectomy

Prevention Relevance Statement:

Despite limited data on overall efficacy, opportunistic salpingectomy for ovarian cancer risk reduction has been rapidly adopted in the U.S. with significant variation in uptake by demographic and clinical factors. Studies examining barriers to opportunistic salpingectomy access and the long-term effectiveness and potential adverse effects of opportunistic salpingectomy are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynecologic cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths among U.S. women.1 Despite advances in treatment over the past three decades, the five-year survival of ovarian cancer remains <50%. Population-based screening for ovarian cancer is currently not recommended as available screening tests have high false-positive rates and are not associated with reductions in ovarian cancer incidence and mortality.2-4 In the absence of effective screening, risk-reducing surgeries have been adopted to reduce the mortality from ovarian cancer in high-risk women.5

Recent studies have indicated that high-grade serous ovarian cancer, the most common and lethal ovarian cancer subtype, originates in the fallopian tubes and involves the ovaries secondarily.6,7 These findings have led to the emergence of opportunistic salpingectomy (OS), the surgical removal of the fallopian tubes, as a novel ovarian cancer risk-reducing strategy. Data from three observational studies suggest that OS may be associated with a 42%-64% reduction in ovarian cancer risk.8-10 However, these studies were conducted in women undergoing OS for indications other than ovarian cancer risk reduction and did not assess long-term morbidity. Despite limited data on efficacy, some national societies in the U.S. now recommend OS for ovarian cancer risk reduction in place of tubal ligation for sterilization or during a benign hysterectomy in average-risk women.11,12 High-risk women, including those with BRCA mutations and/or a strong family history of ovarian cancer are still advised to undergo the removal of both the ovaries (oophorectomy) and the fallopian tubes.5 However, interval OS has been proposed as an approach to delay oophorectomy in premenopausal high-risk women. Several studies are currently assessing the safety and acceptability of this approach in BRCA mutation carriers.13-15

The extent to which guideline recommendations for OS use have led to changes in clinical practice is unclear since the majority of information regarding OS adoption comes from studies that are limited to inpatient settings,16-18 which is not reflective of where most benign gynecologic surgeries are performed in the U.S.19,20 Prior studies have also focused on small geographic regions,21,22 significantly limiting their generalizability. No studies have examined the predictors of OS adoption in a national sample of inpatient and outpatient surgeries.

We conducted a large observational study of over 48 million women to comprehensively characterize recent trends and predictors of OS use in a nationwide sample of inpatient and outpatient insurance claims and evaluate the impact of national guidelines supporting OS use on the speed of OS uptake.

METHODS

Data source

We analyzed deidentified data from the 2010-2017 Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, an administrative claims database that represents a large sample of Americans with commercial, employer-sponsored health insurance. MarketScan includes approximately 350 payers and captures insurance claims from privately insured patients <65 years old and their dependents. The database contains inpatient and outpatient encounters at hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers, and includes demographic characteristics, and admitting and discharge diagnoses and procedure codes. Each enrollee is provided with a unique identification number, which enables linking across different encounters and enrollment years. An individual’s enrollment in the database may be subject to change if they lose employment, change employment, or transition to disability due to illness. The study was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Study population

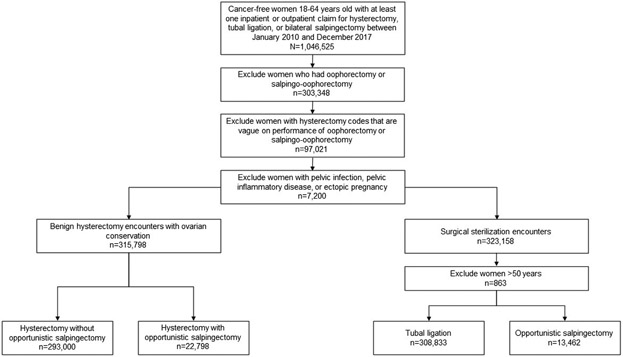

Our study population consisted of 48,231,235 women without a history of breast or gynecologic cancer. Figure 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to identify the analytic sample. Women with at least one claim for tubal ligation, OS, or hysterectomy between 2010 and 2017 were identified (n=1,046,525). All women undergoing an oophorectomy or a salpingo-oophorectomy during hysterectomy (n=303,348), those with hysterectomy codes that do not provide detail regarding removal of additional adnexal structures (n=97,021), and those with ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease or pelvic infection were excluded (n=7,200). For tubal ligation and OS for sterilization, women >50 years were excluded since sterilization procedures are rare in this age group (n=863). After exclusions, 638,093 women with benign gynecologic surgeries were included in the analytic sample. Women were classified into four distinct groups by type of surgery: tubal ligation (n=308,833), OS for sterilization (n=13,462), hysterectomy alone without OS (n=293,000), and hysterectomy and OS (n=22,798). For brevity, hysterectomy alone will denote hysterectomy alone without OS for the rest of the article.

Figure 1.

Criteria used to identify the analytic population.

Classification of surgeries

Surgeries were ascertained using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th and 10th revision procedure codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. A set of minimally sufficient codes were used to classify each surgical procedure (Supplementary Table 1). There were five groups: hysterectomy alone (group 1), hysterectomy, vague on oophorectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy (group 2; CPT codes only), bilateral oophorectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy (group 3), bilateral salpingectomy (group 4), and tubal ligation (group 5). For inpatient procedures, patients with at least one ICD code in group 1 and no ICD codes in groups 3-5 were classified as hysterectomy alone without OS, those with at least one ICD code in group 1 and group 4 and no ICD codes in groups 3 or 5 were classified as hysterectomy and OS, those with at least one ICD code in group 5 and no ICD codes in groups 1, 3, or 4 were classified as tubal ligation, and those with at least one ICD code in group 4 and no ICD codes in groups 1, 3, or 5 were classified as OS for sterilization. For outpatient procedures, patients with at least one CPT code in group 1 and no CPT codes in groups 2-5 were classified as hysterectomy alone, those with at least one CPT code in group 1 with CPT code 58700 and no CPT codes in groups 2, 3, or 5 were classified as hysterectomy and OS, those with at least one CPT code in group 5 and no CPT codes in groups 1-4 were classified as tubal ligation, and those with at least one CPT code in group 4 and no CPT codes in groups 1, 2, 3, or 5 were classified as OS for sterilization.

Clinical and demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics including age (<30, 31-40, 41-50, >50 years), year of surgery (2010-2017), insurance type (health maintenance organization [HMO], preferred provider organization [PPO], other), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and location of residence (rural, urban) were ascertained for each patient. Region of residence was based on U.S. Census delineations23 and location of residence was mapped from the five-digit zip code of the primary beneficiary by Truven Health Analytics.24 Patients were classified based on the type of hysterectomy performed (abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic [abdominal or vaginal]) based on ICD9/ICD10 procedure codes and CPT codes. Surgical indications for hysterectomy were identified based on the primary ICD9/ICD10 diagnosis code associated with the hysterectomy claim. A comorbidity score (0, ≥1 comorbidities) was calculated using the Klabunde adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index.25 Family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer was based on ICD9/ICD10 diagnosis codes. Women were classified as having a family history of breast/ovarian cancer if they had a family history code for breast and/or ovarian cancer, but no genetic susceptibility code for breast and/or ovarian cancer during the study period. Women were classified as having a genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer if they had a genetic susceptibility code for breast and/or ovarian cancer with or without a family history code for breast and/or ovarian cancer during the study period (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for patient characteristics, and annual rates of surgery (tubal ligation and OS for sterilization and hysterectomy and hysterectomy and OS) were calculated overall and by specific subgroups. Rates were calculated as the number of women with surgery during a specified period divided by the total number of women enrolled during the specified period (with and without surgery) and multiplied by 100,000. An interrupted time series (ITS) analysis using segmented Poisson regression was used to evaluate changes in the quarterly rate of OS from January 2010-December 2017, with the Society of Gynecologic Oncology clinical practice guideline release in November 2013 as the interruption.11 The year 2014 was excluded to allow time for guideline implementation, resulting in a post-guideline period from January 2015-December 2017. A scaling parameter was added to the models to allow for overdispersion of data and all models were adjusted for age and seasonal variation by using a Fourier term.26-28

A Poisson regression model with robust variance was utilized to identify predictors of OS use. Covariates were selected a priori based on clinical rationale and literature review. Multivariable-adjusted models were run separately for OS for sterilization and hysterectomy and OS for benign indications. Models were stratified by year of diagnosis (2010-2013 and 2015-2017) to examine the impact of clinical practice guideline release on the predictors of OS use. Multivariable models were adjusted for year of surgery, age, region, location, type of insurance, place of service, family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer, and underlying comorbidities. Multivariable models for hysterectomy and OS were additionally adjusted for hysterectomy route and surgical indication. We further examined the impact of location and region of residence on the use of OS procedures in a subset of women with a family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast and/or ovarian cancer since this group is at the highest risk of ovarian cancer. These models were adjusted for year of surgery, age, type of insurance plan, place of service, and underlying comorbidities. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the impact of including hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy on the uptake of hysterectomy and OS. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 15.1 (Stata Corporation) and all tests of statistical significance were two-sided.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Among 322,295 women undergoing sterilization, 13,462 OS and 308,833 tubal ligations were identified, and among 315,798 women undergoing a benign hysterectomy, 22,798 OS and 293,000 hysterectomies alone were identified (Table 1). The median age at surgery was similar for women undergoing tubal ligation (35 years [interquartile range (IQR): 31-39) and OS for sterilization (36 years [IQR: 32-40]) and hysterectomy (43 years [IQR: 39-48]) and hysterectomy and OS (44 years [IQR: 39-47]). Regardless of surgery type, most women resided in the South (47.0%), in urban locations (79.7%), and had a PPO health plan (61.0%). About 80% of OS for sterilization and 23% of hysterectomy and OS were performed in outpatient settings (44% of all OS procedures). The most common hysterectomy routes for a hysterectomy and OS were laparoscopic (48.5%) followed by abdominal (30.0%). About 6.5% of women had a documented family history of breast/ovarian cancer (8.0% of OS for sterilization; 9.3% of hysterectomy and OS) and 0.3% had a documented genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer (0.5% of OS for sterilization; 0.3% of hysterectomy and OS). Most women undergoing surgeries had no diagnosed comorbidities. Demographic characteristics (age, region, location, type of health plan) of women undergoing surgeries did not differ from the overall study population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the analytic population

| Characteristics, n (%) | All Surgeries | Sterilization Encounters (322,295) | Benign Hysterectomy Encounters (315,798) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubal Ligation | OS | Hysterectomy Alone | Hysterectomy & OS | ||

| Total | 638,093 | 308,833 | 13,462 | 293,000 | 22,798 |

| Age, years | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 39 (8.1) | 35 (5.8) | 36 (5.8) | 44 (7.5) | 43 (6.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 39 (33-44) | 35 (31-39) | 36 (32-40) | 43 (39-48) | 44 (39-47) |

| Age group, years | |||||

| ≤30 | 90,837 (14.2) | 76,741 (24.9) | 2,460 (18.3) | 11,025 (3.8) | 611 (2.6) |

| 31-40 | 286,098 (44.8) | 182,930 (59.2) | 7,993 (59.4) | 88,849 (30.3) | 6,326 (27.8) |

| 41-50 | 212,279 (33.3) | 49,162 (15.9) | 3,009 (22.3) | 146,827 (50.1) | 13,281 (58.3) |

| >50 | 48,879 (7.7) | N/A | N/A | 46,299 (15.8) | 2,580 (11.3) |

| Region of residence | |||||

| Northeast | 85,749 (13.4) | 40,078 (13.0) | 1,931 (14.3) | 39,534 (13.5) | 4,206 (18.5) |

| Midwest | 134,463 (21.1) | 68,640 (22.2) | 2,724 (20.2) | 59,566 (20.3) | 3,533 (15.5) |

| South | 299,993 (47.0) | 143,446 (46.5) | 6,262 (46.5) | 140,476 (47.9) | 9,809 (43.0) |

| West | 104,951 (16.5) | 49,585 (16.1) | 2,452 (18.2) | 47,905 (16.4) | 5,009 (21.9) |

| Unknown | 12,937 (2.0) | 7,084 (2.2) | 93 (0.8) | 5,519 (1.9) | 241 (1.1) |

| Location of residence | |||||

| Rural | 114,319 (17.9) | 87,111 (18.5) | 2,036 (15.1) | 52,507 (17.9) | 2,665 (11.7) |

| Urban | 508,277 (79.7) | 244,189 (79.1) | 11,135 (82.7) | 233,457 (79.6) | 19,496 (85.5) |

| Unknown | 15,497 (2.4) | 7,533 (2.4) | 291 (2.2) | 7,036 (2.5) | 637 (2.8) |

| Insurance type | |||||

| HMO | 78,806 (12.4) | 38,205 (12.4) | 1,574 (11.7) | 35,304 (12.1) | 3,723 (16.3) |

| PPO | 389,165 (61.0) | 188,347 (61.0) | 8,230 (61.1) | 179,819 (61.4) | 12,769 (56.0) |

| Other | 121,761 (19.1) | 57,865 (18.7) | 3,041 (22.6) | 55,907 (19.1) | 4,948 (21.7) |

| Unknown | 48,361 (7.5) | 24,416 (7.9) | 617 (4.6) | 21,970 (7.4) | 1,358 (6.0) |

| Place of service | |||||

| Inpatient | 306,695 (48.1) | 140,391 (45.5) | 2,700 (20.1) | 145,927 (49.8) | 17,677 (77.5) |

| Outpatient | 331,398 (51.9) | 168,442 (54.5) | 10,762 (79.9) | 147,073 (50.2) | 5,121 (22.5) |

| Route of hysterectomy | |||||

| Abdominal | 101,000 (32.0) | N/A | N/A | 87,538 (30.0) | 13,462 (61.6) |

| Vaginal | 64,016 (20.3) | N/A | N/A | 62,715 (21.5) | 1,301 (6.0) |

| Laparoscopic (abdominal or vaginal) | 150,782 (47.7) | N/A | N/A | 142,747 (48.5) | 8,035 (32.4) |

| Family history of/genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer† | |||||

| None | 595,005 (93.2) | 294,263 (95.3) | 12,317 (91.5) | 267,808 (91.4) | 20,617 (90.4) |

| Family history only | 41,767 (6.5) | 14,208 (4.6) | 1,081 (8.0) | 24,354 (8.3) | 2,124 (9.3) |

| Genetic susceptibility | 1,321 (0.3) | 362 (0.1) | 64 (0.5) | 838 (0.3) | 57 (0.3) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||||

| 0 | 614,591 (96.3) | 300,767 (97.4) | 13,101 (97.3) | 279,845 (95.5) | 20,878 (91.6) |

| 1 or more | 23,502 (3.7) | 8,066 (2.6) | 361 (2.7) | 13,155 (4.5) | 1,920 (8.4) |

Abbreviations: OS, opportunistic salpingectomy; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred payer organization.

Family history only includes women with a documented family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, but no genetic susceptibility to breast and/or ovarian cancer and genetic susceptibility includes women with a documented genetic susceptibility to breast and/or ovarian cancer with or without family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer.

All tubal ligations and OS alone included in the study were performed for sterilization. About 23% of tubal ligations and 16% of OS alone were performed postpartum, most of which were performed during a cesarean section (61% of tubal ligations and 60% of OS). Two-thirds of hysterectomies alone were performed for uterine fibroids (31.7%) and abnormal uterine bleeding (31.7%). Other common indications for hysterectomy alone included prolapse (10.7%), pain/other symptoms of the genital tract (8.9%), and endometriosis (7.1%). Women with a diagnosis of uterine fibroids accounted for 46% of all hysterectomy and OS procedures. Other common indications for hysterectomy and OS included abnormal uterine bleeding (27.1%), pain/other symptoms of the genital tract (6.0%), prolapse (5.6%), and endometriosis (4.2%).

Incidence rate of OS

From 2010-2017, there was a 1,683% increase (3 to 47 per 100,000 women) in the annual age-adjusted incidence rate of OS for sterilization and a 659% increase (5 to 38 per 100,000 women) in the incidence rate of hysterectomy and OS. Over the same period, there was a 42% (294 to 169 per 100,000 women) decrease in the rate of tubal ligation and a 76% decrease (341 to 81 per 100,000 women) in the rate of hysterectomy alone (Figure 2). The proportion of sterilization encounters involving OS increased from 1% in 2010 to 20% in 2017 and the proportion of benign hysterectomy encounters involving OS increased from 1% in 2010 to 32% in 2017 (Figure 3). Incidence rates of OS increased across all age groups, in all geographic regions, in rural and urban locations, across all health plans, in women with and without underlying comorbidities, and in women with and without a family history of/genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 2.

Annual age-adjusted rates of tubal ligation and opportunistic salpingectomy for sterilization and hysterectomy alone and hysterectomy and opportunistic salpingectomy for benign gynecologic indications, 2010 to 2017.

Figure 3.

Proportional uptake of opportunistic salpingectomy for sterilization and hysterectomy and opportunistic salpingectomy for benign gynecologic indications, 2010 to 2017.

Speed of OS uptake

Results of the ITS analysis of OS for sterilization revealed that there was a 250% (incidence rate ratio [IRR]: 3.51; 95% CI: 2.53-4.86) increase in the age-adjusted quarterly rate immediately after guideline release followed by a 14% (IRR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.10-1.19) sustained increase in the rate of surgery after compared to before guideline release. For hysterectomy and OS, there was a 109% (IRR: 2.09; 95% CI: 1.65-2.63) increase in the quarterly rate of surgery immediately after guideline release followed by a 3% (IRR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95-0.99) sustained decrease in the rate of surgery after compared to before guideline release. Significant declines in tubal ligation and hysterectomy rates were observed and these declines were temporally associated with the guideline release (Supplementary Table 3). No significant differences were observed in age-adjusted surgery rates in ITS analyses stratified by geographic region, rural/urban location, type of health plan, underlying comorbidities, and family history of/genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer.

Predictors of OS uptake

Results of the multivariable analyses of predictors of OS use are summarized in Table 2. The year of surgery had the strongest association with undergoing OS, with women more likely to undergo OS in 2014-2017 compared to 2010-2013. Compared to women ≤30 years, women 31-40 years (risk ratio [RR]: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.18-1.28) and 41-50 years (RR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.29-1.43) were more likely to undergo an OS for sterilization. Among women ≤50 years, the likelihood of hysterectomy and OS increased with increasing age; however, women >50 years (RR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.76-0.90) were less likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS compared to women ≤30 years.

Table 2.

Multivariable models of factors associated with undergoing an opportunistic salpingectomy

| Characteristics | Sterilization Encounters (n=322,295) | Benign Hysterectomy Encounters (n=315,798) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. | No. OS | RR (95% CI) | Total no. | No. OS | RR (95% CI) | |

| Year of surgery | ||||||

| 2010-2013 | 206,759 | 2,008 | Reference | 236,546 | 6,095 | Reference |

| 2014-2017 | 115,536 | 11,454 | 10.68 (10.19-11.18) | 79,252 | 16,703 | 7.87 (7.66-8.09) |

| Age group, years | ||||||

| ≤30 | 79,201 | 2,460 | Reference | 11,636 | 611 | Reference |

| 31-40 | 190,923 | 7,993 | 1.23 (1.18-1.28) | 95,175 | 6,326 | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) |

| 41-50 | 52,171 | 3,009 | 1.35 (1.29-1.43) | 160,108 | 13,281 | 1.16 (1.08-1.26) |

| >50 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 48,879 | 2,580 | 0.83 (0.76-0.90) |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Northeast | 42,009 | 1,934 | Reference | 43,470 | 4,206 | Reference |

| Midwest | 71,364 | 2,724 | 0.83 (0.79-0.88) | 63,099 | 3,533 | 0.83 (0.80-0.86) |

| South | 149,708 | 6,262 | 0.83 (0.79-0.87) | 150,285 | 9,809 | 0.78 (0.76-0.81) |

| West | 52,037 | 2,452 | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) | 5,760 | 5,009 | 1.19 (1.15-1.24) |

| Location of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 255,324 | 11,135 | Reference | 252,953 | 19,496 | Reference |

| Rural | 59,147 | 2,036 | 0.87 (0.83-0.91) | 55,172 | 2,665 | 0.82 (0.79-0.85) |

| Insurance type | ||||||

| PPO | 196,577 | 8,230 | Reference | 192,588 | 12,769 | Reference |

| HMO | 39,779 | 1,574 | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) | 39,027 | 3,723 | 1.31 (1.27-1.36) |

| Other | 60,906 | 3,041 | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | 60,855 | 4,948 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) |

| Place of service | ||||||

| Inpatient | 143,091 | 2,700 | Reference | 163,604 | 17,677 | Reference |

| Outpatient | 179,204 | 10,762 | 3.42 (3.28-3.56) | 152,194 | 5,121 | 0.34 (0.32-0.35) |

| Family history of/genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer† | ||||||

| None | 306,580 | 12,317 | Reference | 288,425 | 20,617 | Reference |

| Family history only | 15,289 | 1,081 | 1.38 (1.31-1.46) | 26,478 | 2,124 | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) |

| Genetic susceptibility | 426 | 64 | 2.84 (2.31-3.49) | 895 | 57 | 0.70 (0.55-0.90) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||

| 0 | 313,868 | 13,101 | Reference | 300,723 | 20,878 | Reference |

| 1 or more | 8,427 | 361 | 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | 15,075 | 1,920 | 1.27 (1.21-1.32) |

| Hysterectomy route | ||||||

| Laparoscopic (abdominal or vaginal) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 150,782 | 7,108 | Reference |

| Abdominal | N/A | N/A | N/A | 64,016 | 13,462 | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) |

| Vaginal | N/A | N/A | N/A | 101,000 | 1,301 | 0.35 (0.33-0.37) |

| Hysterectomy surgical indication | ||||||

| Other | N/A | N/A | N/A | 212,284 | 12,274 | Reference |

| Uterine fibroids | N/A | N/A | N/A | 103,514 | 10,524 | 1.22 (1.19-1.25) |

Abbreviations: RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred payer organization.

Family history only includes women with a documented family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, but no genetic susceptibility to breast and/or ovarian cancer and genetic susceptibility includes women with a documented genetic susceptibility to breast and/or ovarian cancer with or without family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer.

Women with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer (RR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.31-1.46) and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer (RR: 2.84; 95% CI: 2.31-3.49) were more likely to undergo an OS for sterilization compared to women with no family history of and no genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer. There was no association between family history of breast/ovarian cancer and the likelihood of undergoing a hysterectomy and OS (RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.98-1.06), whereas women with a genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer were less likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS (RR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.55-0.90). Underlying comorbidities were not associated with the likelihood of undergoing an OS for sterilization; however, women with 1 or more comorbidities were more likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS compared to women with no comorbidities.

OS was more likely to be performed during an abdominal compared to a laparoscopic hysterectomy and less likely to be performed during a vaginal compared to a laparoscopic hysterectomy. Compared to other surgical indications, women with uterine fibroids were more likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS (RR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.19-1.25). OS for sterilization was more likely to be performed as outpatient compared to inpatient surgery (RR: 3.42; 95% CI: 3.28-3.56), whereas hysterectomy and OS was less likely to be performed as outpatient compared to inpatient surgery (RR: 0.34; 95% CI: 0.32-0.35). Type of insurance plan was not associated with the likelihood of undergoing an OS for sterilization; however, women enrolled in HMO and other health plans were more likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS compared to women with PPO health plans.

OS uptake differed significantly by region and location of residence. Women residing in the Midwest and South were less likely to undergo an OS for sterilization and hysterectomy and OS compared to women in the Northeast. In contrast, women residing in the West were more likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS compared to women in the Northeast. Additionally, women residing in rural locations were less likely to undergo OS procedures compared to women in urban locations. In models stratified by year of surgery, differences in OS uptake by region of residence decreased after compared to before guideline release and differences in OS uptake by location of residence increased after compared to before guideline release (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5).

To further examine differences in current practice patterns, we evaluated predictors of OS in a subset of women with a family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer who may be more likely to opt for OS if offered. The median age of OS in women with a family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer (OS for sterilization: 38 years [IQR: 34-41]; hysterectomy and OS: 46 years [IQR: 40-50]) was higher compared to women with no family history of and no genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer (OS for sterilization: 34 years [IQR: 30-38]; hysterectomy and OS: 43 years [IRR: 39-48]). Predictors of OS uptake in this high-risk subset did not differ substantially from the overall analysis. Differences in OS uptake were strongly related to the year of surgery and region and location of residence (Supplementary Table 6). After adjusting for year of surgery, age, type of health insurance plan, place of service, and underlying comorbidities, women with a family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer residing in rural and urban areas of the Midwest and South were less likely to undergo an OS for sterilization and hysterectomy and OS compared to those residing in urban areas of the Northeast (Pheterogeneity <0.001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable models of factors associated with undergoing an opportunistic salpingectomy among women at high risk of ovarian cancer by location and region of residence*

| Location/Region of Residence | Sterilization Encounters (n=15,188) | Benign Hysterectomy Encounters (n=14,196)† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. | No. OS | RR (95% CI) | P heterogeneity | Total no. | No. OS | RR (95% CI) | P heterogeneity | |

| Urban Northeast | 2,170 | 192 | Reference | 2,496 | 406 | Reference | ||

| Urban Midwest | 2,701 | 152 | 0.67 (0.55-0.81) | <0.001 | 2,160 | 235 | 0.88 (0.77-1.00) | <0.001 |

| Urban South | 5,674 | 424 | 0.79 (0.68-0.92) | 5,533 | 637 | 0.79 (0.71-0.88) | ||

| Urban West | 2,327 | 200 | 1.00 (0.84-1.20) | 2,281 | 292 | 1.04 (0.92-1.19) | ||

| Rural Northeast | 296 | 15 | 0.72 (0.43-1.19) | 217 | 23 | 0.84 (0.57-1.22) | ||

| Rural Midwest | 584 | 36 | 0.69 (0.50-0.96) | 408 | 28 | 0.59 (0.42-0.82) | ||

| Rural South | 1,216 | 74 | 0.66 (0.52-0.84) | 908 | 78 | 0.65 (0.52-0.80) | ||

| Rural West | 220 | 15 | 0.78 (0.48-1.27) | 193 | 23 | 0.90 (0.61-1.32) | ||

Limited to women with a family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer.

Limited to abdominal hysterectomies with or without laparoscopy. Abbreviations: RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval. Models adjusted for year of surgery, age, type of insurance, place of service, and number of comorbidities.

In sensitivity analysis, including hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to the analytic sample did not significantly alter the overall results. With bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies included, the proportion of benign hysterectomy encounters involving OS increased from 1% in 2010 to 24% in 2017. Additionally, there was no significant change in ITS analysis of hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy immediately after guideline release (IRR: 1.07; 995% CI: 0.90-1.12) or after compared to before guideline release (IRR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.95-1.07).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to characterize the uptake of OS in women undergoing sterilization and benign hysterectomies in inpatient and outpatient settings. Thus, our study offers the first complete look at the adoption of OS in the U.S. We observed that between 2010 and 2017, the rate of OS for sterilization and hysterectomy and OS increased 17.8-fold (95% CI: 16.2-19.5) and 7.6-fold (95% CI: 5.5-10.4), respectively. If this rate remains constant, OS will account for >50% of all sterilization and benign hysterectomy encounters in privately insured women in the U.S. by 2022. We also noted substantial variation in the use of OS, with 94% of OS performed among women ≤50 years, higher uptake of OS for sterilization in women with a family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer, and higher uptake of OS in the Northeast and West and urban locations. Additionally, OS use during hysterectomy was higher among women undergoing an abdominal hysterectomy and women with uterine fibroids. Significant variation in OS uptake, notably by region and location of residence, was also observed in analyses limited to high-risk women. These findings could reflect provider and patient knowledge and preferences regarding OS use, insurance coverage, and access to the fallopian tubes during surgery.

The reasons for the rapid increase in OS are likely multifactorial. In addition to the multiple clinical practice guidelines advocating for the use of OS for ovarian cancer risk reduction,11,12,29 other factors that may have contributed to the rapid adoption of OS include the lack of effective screening tests for ovarian cancer, the high morbidity and mortality associated with ovarian cancer, the high prevalence of gynecologic surgeries currently eligible for OS, and provider enthusiasm. The rapid increase in OS could also be driven by insurance reimbursements, which can significantly influence hospital policies and clinical practice. According to national payment amounts from Medicare, a standard that many other payers use to determine reimbursement, the average payment in 2017 for performing a tubal ligation (CPT 58670) in the office was $371.45, and the payment for performing a bilateral salpingectomy (CPT 58700) was $797.45.30 The finding that women >50 years were less likely to undergo a hysterectomy and OS may be attributed to the fact that these women are closer to the age of natural menopause and may therefore be considered for a bilateral oophorectomy instead of OS for ovarian cancer risk-reduction. In addition to the rapid adoption of OS during benign hysterectomy, the decline in hysterectomy rates observed in this study may also be due to increased use of uterine-sparing procedures for uterine fibroids, abnormal bleeding, and pelvic pain, the most common indications for hysterectomy among reproductive-aged women.31,32

To date, only three studies have assessed predictors of OS use during a benign hysterectomy in the U.S.17,18,33 Prior studies assessing OS use during benign hysterectomy demonstrated increased uptake of OS in young women, large-volume hospitals, the Northeast, and women with underlying comorbidities. Our study confirmed these findings and identified additional factors driving OS uptake. It is important to note that all these prior studies relied on datasets limited to inpatient procedures only, providing a biased and incomplete view of trends in OS uptake. Approximately 44% of OS procedures in our database were performed in outpatient settings (80% of OS for sterilization and 23% of hysterectomy and OS). Additionally, these studies included narrow age ranges, lacked data from more recent time periods, had small sample sizes, and lacked information on family history of and genetic susceptibility to breast/ovarian cancer.

In discussing OS uptake, it is also important to highlight the limited evidence to support the use of OS for ovarian cancer risk reduction. Only three studies have assessed ovarian cancer risk after OS. These studies suggest that OS is associated with a 42%-64% lower risk of ovarian cancer.8-10 However, none of these studies evaluated OS specifically for ovarian cancer risk reduction but rather focused on OS for specific indications such as pelvic infection and endometriosis. Additionally, there is limited data on the potential adverse effects associated with OS. A registry-based study found that women undergoing hysterectomy and OS had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1-year after surgery compared to hysterectomy alone (RR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.04-1.69).34 Studies evaluating the impact of OS on short term ovarian function have found no detrimental effects.35-37

Although our analysis benefits from the inclusion of a very large number of privately insured women, our results may not be generalizable to women who have public insurance plans such as Medicaid and Medicare. However, it is estimated that about 60% of women <65 years received their health coverage through employment-sponsored health insurance plans in 2017, representing the largest segment of U.S. healthcare users.38 Additionally, we could not capture individual patient and physician perceptions and attitudes, which likely influenced OS uptake. Furthermore, our dataset lacked several important factors, such as race/ethnicity, education, and body mass index, that likely influenced OS uptake. Finally, our analysis is limited by the nature of claims data, which may involve errors in coding or incomplete documentation for some conditions, such as a family history of and genetic susceptibility to cancer, that could lead to misclassification of covariates.

In conclusion, we found that clinicians in the U.S. have rapidly adopted OS for ovarian cancer risk reduction with significant variation in use by demographic and clinical factors even among women at high risk of ovarian cancer. Given the rapid uptake of OS in average-risk women, prospective studies are needed to evaluate the impact of OS on ovarian cancer incidence, mortality, and potential adverse effects, such as premature menopause. This information could be used to inform clinical practice and insurance reimbursement. Current studies are focused on young BRCA1 carriers. From a clinical and public health standpoint, identifying subsets of women who would benefit the most from OS for ovarian cancer risk-reduction and developing initiatives to address barriers to equitable OS uptake is needed.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers: NCI T32 CA009314 (Karia), NCI T32 CA094061 (P.S. Karia), and NCI P30 CA006973 (C.E. Joshu and K. Visvanathan), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (K. Visvanathan).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no financial disclosures of conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. Cancer Stat Facts: Ovarian Cancer 2020; https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed November 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2295–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Force USPST, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for Ovarian Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(6):588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, et al. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(1):77–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarboe E, Folkins A, Nucci MR, et al. Serous carcinogenesis in the fallopian tube: a descriptive classification. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labidi-Galy SI, Papp E, Hallberg D, et al. High grade serous ovarian carcinomas originate in the fallopian tube. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lessard-Anderson CR, Handlogten KS, Molitor RJ, et al. Effect of tubal sterilization technique on risk of serous epithelial ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(3):423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen C, Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, Kjaer SK. Tubal ligation and salpingectomy and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer and borderline ovarian tumors: a nationwide case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(1):86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falconer H, Yin L, Gronberg H, Altman D. Ovarian cancer risk after salpingectomy: a nationwide population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society of Gynecologic Oncology clinical practice statement: salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention 2013; https://www.sgo.org/clinical-practice/guidelines/sgo-clinical-practice-statement-salpingectomy-for-ovarian-cancer-prevention/. Accessed September 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology committee opinion no. 620: Salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):279–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmsen MG, Arts-de Jong M, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. Early salpingectomy (TUbectomy) with delayed oophorectomy to improve quality of life as alternative for risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (TUBA study): a prospective non-randomised multicentre study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nebgen DR, Hurteau J, Holman LL, et al. Bilateral salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy for ovarian cancer risk reduction: A pilot study in women with BRCA1/2 mutations. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(1):79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NRG Oncology. A study to compare two surgical procedures in women with BRCA1 mutations to assess reduced risk of ovarian cancer (SOROCk). 2021; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04251052. Accessed March 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikhail E, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, Hart S, Salihu HM, Imudia AN. National trends of adnexal surgeries at the time of hysterectomy for benign indication, United States, 1998–2011. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(5):713 e711–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley GE, McAlpine JN, Pearce CL, Miller D. The performance and safety of bilateral salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):270 e271–270 e279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandelbaum RS, Adams CL, Yoshihara K, et al. The rapid adoption of opportunistic salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doll KM, Dusetzina SB, Robinson W. Trends in Inpatient and Outpatient Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy Rates Among Commercially Insured Women in the United States, 2000-2014. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(9):876–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore BJ, Steiner CA, Davis PH, Stocks C, Barrett ML. Trends in hysterectomies and oophorectomies in hospital inpatient and ambulatory settings, 2005-2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, HCUP Statistical Brief #214 2016; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb214-Hysterectomy-Oophorectomy-Trends.jsp. Accessed November 4, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell CB, Alabaster A, Simmons S, et al. Salpingectomy for Sterilization: Change in Practice in a Large Integrated Health Care System, 2011-2016. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):961–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Till SR, Kobernik EK, Kamdar NS, et al. The Use of Opportunistic Salpingectomy at the Time of Benign Hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(1):53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Census Bureau Geographic Program. Geographic terms and concepts—census divisions and census regions. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography.html. Accessed August 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Census Bureau Geographic Program. Metropolitan and micropolitan. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro.html. Accessed August 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhaskaran K, Gasparrini A, Hajat S, Smeeth L, Armstrong B. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1187–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunsberger S, Albert PS, Follmann DA, Suh E. Parametric and semiparametric approaches to testing for seasonal trend in serial count data. Biostatistics. 2002;3(2):289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salvador S, Scott S, Francis JA, Agrawal A, Giede C. No. 344-Opportunistic Salpingectomy and Other Methods of Risk Reduction for Ovarian/Fallopian Tube/Peritoneal Cancer in the General Population. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(6):480–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare and Medicais Services. Physician fee schedule. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search. Accessed May 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee DW, Gibson TB, Carls GS, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Stewart EA. Uterine fibroid treatment patterns in a population of insured women. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Dongen H, van de Merwe AG, de Kroon CD, Jansen FW. The impact of alternative treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding on hysterectomy rates in a tertiary referral center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu X, Desai VB. Hospital Variation in the Practice of Bilateral Salpingectomy With Ovarian Conservation in 2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins E, Strandell A, Granasen G, Idahl A. Menopausal symptoms and surgical complications after opportunistic bilateral salpingectomy, a register-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):85 e81–85 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Findley AD, Siedhoff MT, Hobbs KA, et al. Short-term effects of salpingectomy during laparoscopic hysterectomy on ovarian reserve: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(6):1704–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morelli M, Venturella R, Mocciaro R, et al. Prophylactic salpingectomy in premenopausal low-risk women for ovarian cancer: primum non nocere. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129(3):448–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sezik M, Ozkaya O, Demir F, Sezik HT, Kaya H. Total salpingectomy during abdominal hysterectomy: effects on ovarian reserve and ovarian stromal blood flow. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33(6):863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiser Familty Foundation. Women's Health Insurance Coverage. 2018; https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage-fact-sheet/. Accessed December 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.