Abstract

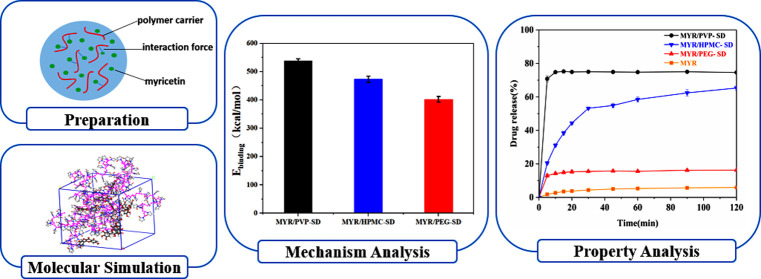

Although the preparation of amorphous solid dispersions can improve the solubility of crystalline drugs, there is still a lack of guidance on the micromechanism in the screening and evaluation of polymer excipients. In this study, a particular method of experimental characterization combined with molecular simulation was attempted on solubilization of myricetin (MYR) by solid dispersion. According to the analysis of the dispersibility and hydrogen-bond interaction, the effectiveness of the solid dispersion and the predicted sequence of poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) > hypromellose (HPMC) > poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) as the polymer excipient were verified. Through the dissolution, cell viability, and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-level detection, the reliability of simulation and micromechanism analysis was further confirmed. This work not only provided the theoretical guidance and screening basis for the miscibility of solid dispersions from the microscopic level but also served as a reference for the modification of new drugs.

1. Introduction

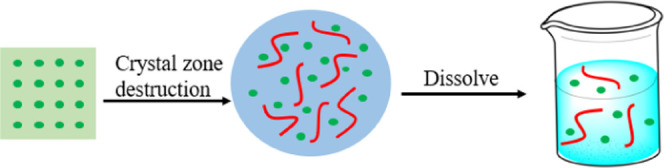

Highly crystalline drugs usually have low water solubility and lead to low bioavailability, which limits their application and promotion.1,2 Among the drugs that have been developed, low-water-solubility drugs account for about 70%.3,4 For targeting this drawback, it is significant to apply related technologies to improve the solubility of drugs in water. The common methods include solid dispersion loading,5 prodrug synthesis,6 cyclodextrin complexation,7 phospholipid complexation,8 polymerization micellar loading,9 nanoparticle delivery,10 cocrystallization,11 etc. At present, the solid dispersion technology has been widely used as a method of drug solubilization.12 The specific mechanism of solid dispersion13 is shown in Figure 1. This technology uses experiments to mix poorly soluble drugs with amphiphilic polymer excipients to reduce the crystallinity of the drugs.14 The solubility, dissolution rate in vitro, bioavailability, and other properties of some insoluble drugs can be greatly enhanced by this technology.15,16

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of coating and dissolution of solid dispersion (the green dots and red lines represent molecules of drug and molecular chains of polymer excipients, respectively).

Like many crystalline drugs, myricetin (MYR) has certain antiviral,17 antitumor,18 and antibacterial activities,19 but it contains multiple active phenolic hydroxyl groups in the molecule, which can form a large number of intermolecular hydrogen bands and eventually induce crystallization. This causes its solubility in water to be so low that it is difficult to be absorbed by the human body and participate in the scavenging of reactive oxygen species. For this reason, it needs to be modified by a certain solubilization technology. Hopefully, relevant studies have proved the feasibility of preparing solid dispersions as the solubilization of such kinds of drugs.20

The addition of polymer excipients in the solid dispersion is the key to improving the water solubility of highly crystalline drugs. Common polymer excipients include poly(ethylene glycol), hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, poly(vinyl pyrrolidone), poloxamer 188, and so on.12,21 These polymer materials contain polar groups such as terminal hydroxyl groups, carbonyl groups, or ether bonds in their molecules. While they have good hydrophilicity, they can also form hydrogen bonds with crystalline drug molecules to destroy the crystallization of drugs and achieve good solubilization.

Researchers mainly make use of solvent evaporation,22 melt extrusion,23 spray-drying,24 microwave radiation,25 and cross-linking26 for the preparation of solid dispersions. For the characterization of solid dispersion effects, different methods have been applied, which include differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) according to the thermal property, microscopic morphology, and crystallization analysis.15,27 In addition, the performance description focuses on the application level of drugs loaded into solid dispersions as well, such as the dissolution in vitro, antioxidation, cell activity, scavenging ROS, etc.28,29

Nowadays, the application of molecular simulation technology through modeling and running dynamic processes to obtain corresponding parameters has been emphasized.30−32 On the scale of miscibility evaluation, some parameters obtained through simulation, such as solubility parameters (δ), Flory–Huggins parameters (χ), and mixing energy (ΔEmix), can be used for evaluation criterion.33 These parameters can be used to analyze and compare the dispersibility and the strength of mutual binding in the mixed system, reflecting the destructive crystallization and compatibilization effects of polymers on poorly soluble drugs. For instance, Barmpalexis34 et al. obtained the solubility parameters of Soluplus and each plasticizer and the mixing energy of each miscible system from molecular dynamics (MD) and molecular docking simulations to discuss the compatibility. In addition, with the help of the radial distribution function (g(r)) extracted from the process of MD, the type of hydrogen bond generated in the system and its probability of occurrence can be judged, which would be practical for analyzing the interactions. Kapourani35 et al. drew the g(r) images of all hydrogen bonds in the Rivaroxaban and Rivaroxaban–Soluplus systems and then calculated the probability distribution of the number of hydrogen bonds between molecules in each group, which clearly and intuitively demonstrated the mutual combination of the two samples. Therefore, the methods of molecular simulation could be theoretical support to experimental characterization of the compound materials.

Although many methods of characterization and molecular simulation parameters have enriched the study of the micromechanism and macroperformance of solid dispersion systems,15,36 the vacancy of horizontal screening of different excipients in solid dispersion systems still needs to be made up for. For example, the radial distribution function g(r) can be used as an important indicator for discussing hydrogen bonds between molecules in solid dispersions, but when it is used to compare the interaction between multiple excipients and drugs, it is necessary to consider the strength of the hydrogen bond and the amount of content for adjuvant. It means that the method of screening the optimal excipients through the theoretical parameter discussion of the difference of various excipient–drug microdispersion and interaction combined with experimental results has not been reported yet.

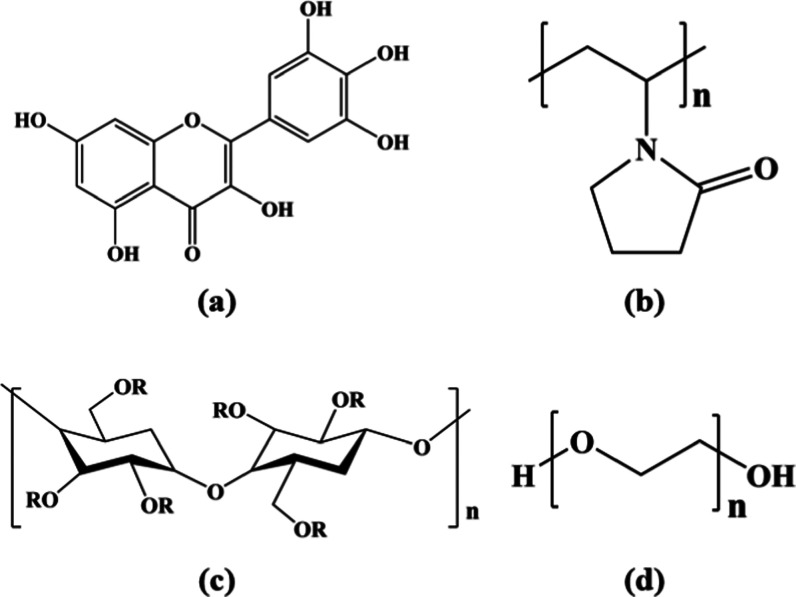

Therefore, this study aimed at developing a set of related molecular simulation techniques to evaluate the dispersibility and interaction mechanism of different excipients and myricetin and to complete the screening of excipients in combination with characterization methods. In this research, poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP), hypromellose (HPMC), and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) were selected as excipients because they have been already commercialized and there were related reports that provide evidence that these excipients can solubilize hydrophobic drugs.37 Their molecular chains all contain polar end groups or side groups, which can form intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the phenolic hydroxyl groups of myricetin molecules, thereby destroying myricetin crystals. The structures of myricetin and the excipients mentioned above are shown in Figure 2. Through the comparison and discussion of these parameters and related performance characterization results, the modification effects of various excipients can be evaluated and screened.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of selected polymer excipients (a) MYR, (b) PVP, (c) HPMC, and (d) PEG.

2. Molecular Simulation

2.1. Molecular Dynamic Simulation

As mentioned above, the addition of polymer excipients can inhibit molecular migration and destroy the crystallization of antioxidants. Therefore, through molecular dynamics (MD) simulation technology,38−40 the kinetic model of the single system and the binary system of polymer/myricetin can be established, which can explain the mixing and binding mechanism on a microscopic scale, and compare and screen polymer excipients.

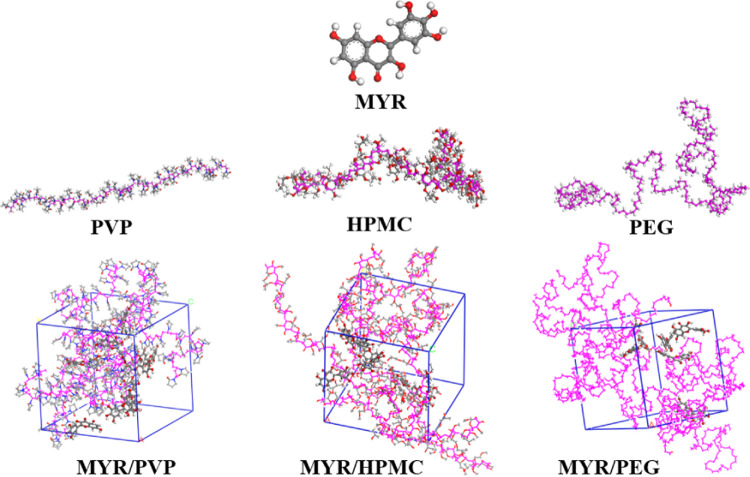

In this study, the work of molecular simulation was carried out in Materials Studio (Accelrys) software. The model building procedure is shown in Figure 3. In the constructed mixed model, in the system containing PVP, HPMC, and PEG, four long excipient chains were placed in each box and eight, seven, and six myricetin molecules were added, respectively. The myricetin contents of each system were 10.27, 9.71, and 9.16%, respectively. Moreover, the constructed molecular chains of PVP, HPMC, and PEG contained 50, 25, and 100 repeating units to keep the total number of atoms in each system close.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of periodic cell modeling for molecular dynamics simulation (the red, gray, and white balls represent oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen atoms, respectively, while magenta balls and lines represent the molecular chains of three polymers).

With the constructed periodic cells, the corresponding dynamic process was run. First, the cells with minimized energy are annealed under the COMPASS (condensed-phase optimized molecular potentials for atomistic simulation studies) force field,41 and 200 anneal cycles of NVE (constant atoms’ number, constant volume, constant energy) are performed between 300 and 500 K. Thereafter, on the basis of the last frame constellation of the previous step, the process of NVT (constant atoms’ number, constant volume, constant temperature) of at least 500 ps and the NPT process of at least 1000 ps are run one by one. To verify the reliability of the model during molecular dynamics simulation, the density and energy of the system were monitored. When the system reached equilibrium, the density of the system converges (with fluctuations within 5%) and it was compared with the actual density. Besides, its energy convergences including potential energy, kinetic energy, nonbond energy, and total energy were also detected, and their fluctuation range did not exceed 5% as well.42

2.2. Quantum Mechanics Simulation

Quantum mechanics simulation is realized through the DMol3 module. The small molecular units of the electron donor and the electron acceptor and their hydrogen-bond association dimers were constructed. Their energy minimization was carried out using molecular dynamics methods. Then, through the DMol3 module, the geometry optimization tasks were performed. According to the density functional theory (DFT)43 and the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)44 of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional form, the exchange correlation potential in the Kohn–Sham (KS) equation is approximated, and the additional polarization function (TNP)44 basis set describes the wave function of the system.

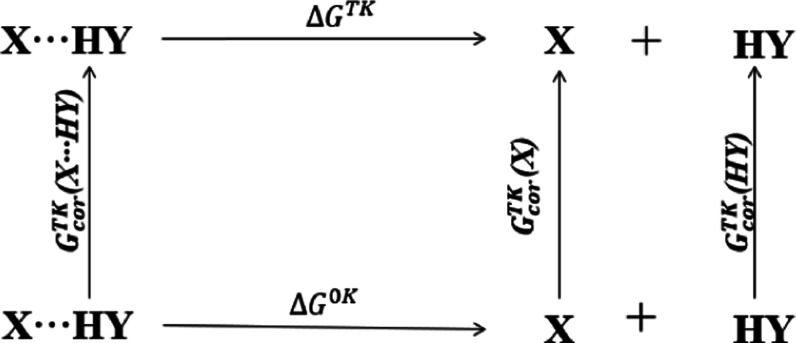

According to the thermodynamic cycle diagram of hydrogen-bond dissociation in Figure 4, the Gibbs free energy of hydrogen-bond dissociation is calculated as shown in formula 1(45)

| 1 |

here, X refers to the electron donor; HY refers to the electron acceptor; G0K represents the standard Gibbs free energy of X, HY, X···HY at 0 K; GTK refers to the standard Gibbs free energy of X, HY, X···HY at T K; and Gcor refers to the corrected value of Gibbs free energy calculated from 0K to TK for X, HY, and X···HY.

Figure 4.

Thermodynamic cycle diagram of hydrogen-bond dissociation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dispersive Research

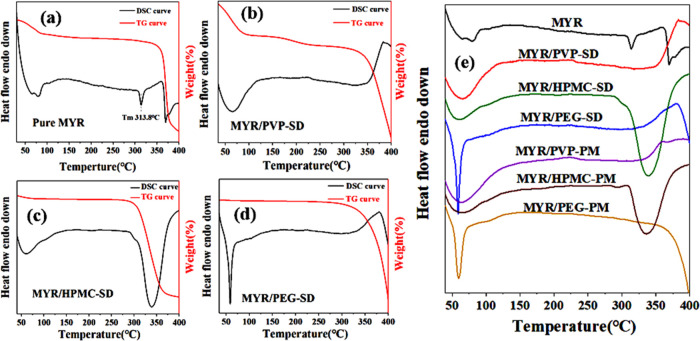

3.1.1. Simultaneous Thermal Analysis

Through the DSC–TG combined technology, the thermal behaviors of myricetin (MYR), physical mixing (PM), solid dispersion (SD), and other samples were observed and analyzed. It can be seen from Figure 5a that pure MYR shows a dehydration behavior before about 100 °C. The DSC curve has an exothermic behavior at 313.8 °C,20 while the TG curve at the same temperature exhibits no obvious change, indicating that MYR melts at this temperature. The TG curve displays that the sample undergoes thermal decomposition between 350 and 370 °C. An obvious melting endothermic peak can be observed before thermal decomposition, indicating the crystallization of the pure MYR sample.

Figure 5.

DSC–TG curve of each sample: (a) pure MYR, (b) MYR/PVP-SD, (c) MYR/HPMC-SD, and (d) MYR/PEG-SD, and (e) the summary of the DSC curve.

Although the intensity of the melting characteristic peak at about 310 °C is reduced in the PM samples, it still exists, as summarized in Figure 5e. Regarding the thermal behavior of the myricetin–polymer solid dispersion, it can be seen from Figure 5b–d that the melting endothermic peak of myricetin at about 313.8 °C disappears in all of the SD samples. This result reflects the good compatibility between myricetin with polymer excipients, and the amorphous degree is improved.

3.1.2. Crystallinity Analysis

The XRD curves are shown in Figure 6a–c. First, the pure MYR sample represents dense and sharp crystal diffraction peaks, which indicates the high crystallinity. Meanwhile, the corresponding crystal diffraction peaks can also be observed in the three physical mixture (PM) systems. However, the intensity of these crystal diffraction peaks is lower than that of the pure MYR sample. The three samples of solid dispersion (SD) of MYR express obvious amorphous characteristics. Therefore, the solid dispersion obtained experimentally means that adding polymers ideally disperses the agglomerated myricetin crystals.

Figure 6.

XRD spectra of three polymer–myricetin systems: (a) MYR/PVP, (b) MYR/HPMC, and (c) MYR/PEG, and (d) comparison of the crystallinity.

The essence of the solubilization of myricetin by polymer excipients is actually to inhibit the crystallization of myricetin through the intermolecular interaction between the polymer and myricetin so as to test the dispersibility of myricetin. Therefore, the calculation of crystallinity can directly quantify the inhibitory effect of excipients on myricetin crystallization. The results of XRD spectra were used for peak fitting, and the crystallinity could be further calculated. Here, the diffraction peak with a half-maximum width (FWHM) greater than 3° is defined as an amorphous peak,46 and the proportion of the crystal diffraction peak area is figured out, with the crystallinity results shown in Figure 6d. It can also be seen that the solid dispersion (SD) effectively reduces the crystallinity compared to the physical mixture (PM) of the corresponding systems. In particular, the crystallinity of PVP/MYR-SD decreased the most significantly, which reduced the 95.44% crystallinity of pure MYR to 2.79%, followed by HPMC/MYR-SD, and finally PEG/MYR-SD.

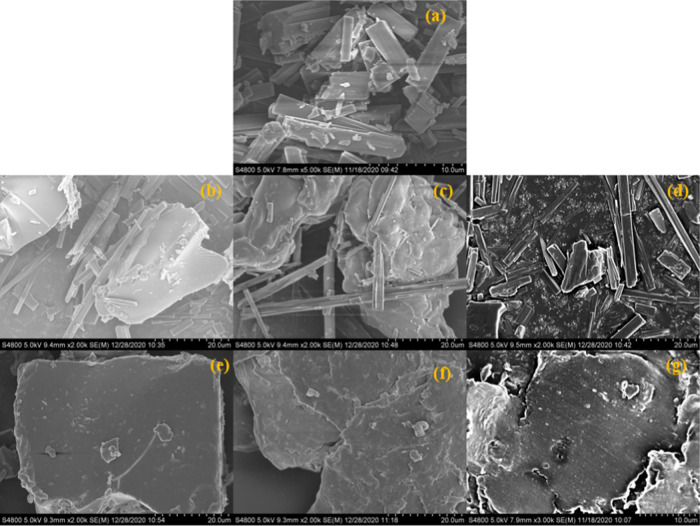

3.1.3. Surface Topography

SEM can be used to observe the surface topography of the samples. As shown in Figure 7, the pure solid powder of myricetin presents a rod-shaped sharp crystal structure (Figure 7a), while the myricetin–polymer physical mixture powder does not have sharp crystal regions like myricetin, but there is still a small amount of aggregation (Figure 7b–d). The agglomeration phenomenon in the three solid dispersion samples is significantly less present (Figure 7e–g). Compared with the physical mixture samples, the surface is smoother in the solid dispersion systems, which more specifically reflects the decrease in crystallinity of myricetin and the increase in dispersibility.

Figure 7.

SEM images of myricetin, physical mixture, and solid dispersion: (a) pure MYR, (b) MYR/PVP-PM, (c) MYR/HPMC-PM, (d) MYR/PEG-PM, (e) MYR/PVP-SD, (f) MYR/HPMC-SD, and (g) MYR/PEG-SD.

3.1.4. Molecular Simulation Results

For discussing the compatibility of MYR and excipients, the rule of solubility parameter value for judging miscibility does not apply to all binary mixing systems, especially systems with a negative heat of mixing. Instead, the Flory–Huggins parameters (χ) and the mixing energy (ΔEmix) can be used to evaluate the compatibility of antioxidant molecules with the polymer matrix47 for which the Flory–Huggins parameter is positively correlated with the ratio of mixing energy and temperature, which directly explains the difficulty of mixing the two substances. During the modeling and calculation, the polymer is set as the base and the antioxidant is set as the screen. The methods of obtaining of two parameters are shown in formulas 2 and 3. Here, E is the energy of interaction, with “b” and “s” representing molecules of the base and screen, respectively, and Z is the number of coordination. The lower the values of the two parameters, the better the mixing effect in the mixing system.36

| 2 |

| 3 |

The calculated χ and ΔEmix are provided in Figure 8a and b, respectively. It can be seen that χ and ΔEmix achieve the highest value in the MYR/PVP system (red line), which shows that MYR has the best compatibility with PVP, so that the two can even be mixed spontaneously. The compatibility with HPMC is second, and the compatibility with PEG is unsatisfactory.

Figure 8.

(a) Flory–Huggins parameter χ of three solid dispersion systems, (b) mixing energy (ΔEmix) of three solid dispersions, (c) mean square displacement (MSD) of MYR in three systems, and (d) binding energy (Ebinding) of MYR with polymer excipients.

The mean square displacement (MSD) may be used to reflect the movement and migration ability of small molecules.45 The calculation of MSD is shown in formula 4(42)

| 4 |

Among them, ri(0) and ri(t) refer to the position coordinates of molecule i at times 0 and t, respectively. The greater the MSD value changes over time, the more significant the migration of molecules.48 Thus, the results from Figure 8c show the lowest migration of MYR in the PVP system, which agrees with the χ and ΔEmix analyses.

Meanwhile, the binding energy (Ebinding)49 can reflect the dispersibility of the antioxidant in the polymer matrix and indirectly reflect the ability of the polymer excipients to destroy the crystal region of the antioxidant. The value of binding energy can be obtained by formula 5

| 5 |

In addition, Ebinding represents the strength of the combination of the two and indirectly reflects the dispersibility of small molecules in the polymer excipients. In formula 5, Etotal represents the energy of the miscible system, while EMYR and Epolymer represent energies of MYR and the polymer excipient, respectively. From Figure 8d, the binding energy of MYR in PVP is greater than the two other systems, which also provides a theoretical basis for the above decreased crystallinity results.

3.2. Internal Interaction Force of Solid Dispersion

3.2.1. FTIR Result Analysis

As shown in Figure 9a–c of the FTIR results, the spectra of the SD samples of the three systems are the superposition of the spectra of pure MYR and the respective polymer excipients, and no new characteristic absorption peaks are generated. This indicates that there is no chemical reaction during PM and SD manufacturing processes. The MYR spectrum shows the phenolic hydroxyl stretching vibrations at the wavenumbers of 3417 and 3285 cm–1. The peaks broaden and disappear in the respective SD spectra (red curves), while the phenomenon is not obvious in the PM spectra (green curves), which shows that there are hydrogen bonds between the −O–H group of MYR and the −O–H or −C=O of three polymer excipients in SD systems.20

Figure 9.

Fourier infrared spectra of (a) PVP/MYR, (b) HPMC/MYR, and (c) PEG/MYR of myricetin, PM, and SD polymer excipients.

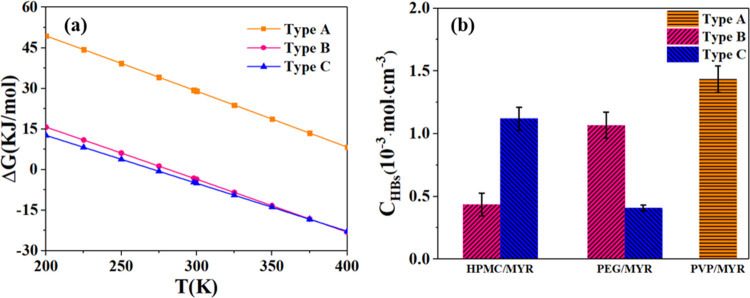

3.2.2. Hydrogen-Bond Analysis

The hydrogen bond is the directional attraction acting on the electron-deficient hydrogen atom and the highly electronegative atom.50 These two parts are, respectively, the electron acceptor and the electron donor. The judge standard to form the hydrogen bonds is the existence of these two parts, and relevant geometric parameters conform to the judgment principle proposed by Jeffery.51 The greater the absolute value of the atomic charge, the easier it is to act as a donor or acceptor for forming hydrogen bonds. Figure 10a and Table 1 present the charge distribution of MYR molecules. From the figures and the charge values, the phenolic hydroxyl hydrogen atoms (H1/H3/H5/H7/H8/H9) in MYR molecules have a higher positive charge and tend to act as electron acceptors for intermolecular hydrogen bonds or intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The negatively charged oxygen atoms such as O1/O2/O6/O7/O8 in the molecule tend to form hydrogen-bond electron donors.

Figure 10.

(a) Myricetin molecular model and the ID of the atoms in the molecule. The radial distribution function (g(r)) of the three types of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in (b) PVP/MYR, (c) HPMC/MYR, and (d) PEG/MYR, and the characteristic peaks of the radial distribution that form hydrogen bonds are marked with green circles.

Table 1. Charge Distribution of Each Atom in the MYR Molecule.

| atom | charge |

|---|---|

| C1/C3/C5/C6/C12/C13/C14/C15 | 0.042 |

| C2/C4/C11 | –0.1268 |

| C7 | 0.367 |

| C8/C9 | 0.0265 |

| C10 | 0 |

| O1/O2/O6/O7/O8 | –0.452 |

| O3 | –0.0685 |

| O4 | –0.419 |

| O5 | –0.4365 |

| H1/H3/H5/H7/H8/H9 | 0.41 |

| H2/H4/H6/H10 | 0.1268 |

It can be known from the molecular structure of myricetin and the selected polymer that there is a tendency to form intermolecular hydrogen bonds between myricetin and the polymer. The −C = O group in PVP and the −C–O– group in HPMC and PEG can be regarded as the electron donors of the hydrogen bond, and they physically bind to the phenolic hydroxyl site of myricetin. The stronger the hydrogen bond between myricetin molecules and the polymer, the lower the mobility of myricetin molecules, which can better inhibit myricetin crystallization. According to the atom and group composition of the electron donor and electron acceptor, the kinds of hydrogen bonds that may appear in solid dispersion are classified and shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Classification of H-Bonds According to Electron Donor and Electron Acceptor.

| H-bond | electron donor | electron acceptor |

|---|---|---|

| type A | MYR–OH | –C=O |

| type B | MYR–OH | –C–O–C– |

| type C | MYR–OH | –C–O–H |

The radial distribution function (RDF and g(r)) can be used to describe the distribution of hydrogen bonds.52 The g(r) is the probability of finding another atom when the distance is r, where g(r) is a quantity of dimension 1. When r is near 2–2.5Å, the possibility of forming hydrogen bonds is the largest.45Figure 10b–d shows that three systems all contain intermolecular hydrogen bonds, which correspond to the characterization results of FTIR in Section 4.2.1. The intermolecular hydrogen bond of type A can only be observed in the system PVP/MYR, while type B and type C can also exist in the other two systems. In addition, the oxygen atom of hydroxy tends to be an electron donor more than that of the ether bond in the polymer chain, which could be inferred from the results of Figure 10c,d.

The Gibbs free energy of hydrogen-bond dissociation can be calculated to measure the strength of the hydrogen bonds.53 As is shown in Figure 11a, the Gibbs dissociation free energy (ΔG) of type A hydrogen bonds (orange color) is significantly higher than that of types B and C. The latter two types can also dissociate spontaneously, but the binding effect of myricetin with PVP is the strongest.

Figure 11.

(a) Gibbs free energy of the dissociation reaction of three types of hydrogen bonds; (b) molar concentration of all hydrogen bonds in the three systems.

The molar concentration of intermolecular hydrogen bonds (CHBs) that is achieved from eq 6 is the number of moles of intermolecular hydrogen bonds per unit volume of the system.54 Here, NHBs refers to the number of hydrogen bonds, NA is the Avogadro constant, and V refers to the volume of periodic cells.55 It is used to evaluate the content of each hydrogen bond in the systems.45

| 6 |

From the analysis of the hydrogen-bond molar concentration results in Figure 11b, the type A hydrogen bonds in PVP (orange column) have not only a strong effect but also a high molar concentration value. Therefore, the intermolecular interaction of this system is more significant and it is easier to make myricetin molecules more dispersed in PVP than the other two.

3.3. Characterization of Solubility

3.3.1. Standard Melting Curve and Equilibrium Solubility

The myricetin–ethanol solution with a concentration of 2–18 μg/mL was configured into five solution samples according to a concentration gradient of 4 μg/mL, and the UV–vis curve in the range of 450–300 nm was measured as shown in Figure 12a. Myricetin solution has a maximum absorption peak at a wavelength of 377 nm, and there is an ideal linear correlation (R2 = 0.9999) between the maximum absorption value and the concentration, and the solubility standard curve of myricetin is drawn in Figure 12b.

Figure 12.

(a) UV–vis curve of different concentrations of myricetin–ethanol solution in the range of 300–450 nm; (b) solubility standard curve of myricetin.

Compared with the standard solubility curve, the equilibrium solubilities of pure myricetin and three solid dispersion samples were measured. The results are shown in Table 3. It can be found that the equilibrium solubility of myricetin using PVP as the excipient is about 26 times higher than the PEG system and about 5 times higher than the HPMC system. In the previous simulation calculations, it was obtained that the PVP/MYR hybrid system has a stronger PVP-MYR intermolecular force than the other two systems, which will destroy the crystallization of myricetin and improve its solubility in water. Obviously, the results of equilibrium solubility could confirm this point.

Table 3. Equilibrium Solubility of MYR and Three Types of Solid Dispersion.

| samples | MYR | MYR/PVP-SD | MYR/HPMC-SD | MYR/PEG-SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| equilibrium solubility (μg/mL) | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 50.74 ± 0.05 | 9.87 ± 1.40 | 1.94 ± 0.08 |

In addition, the same content of myricetin and the solid dispersion was weighed in the same volume of deionized water and it was fully stirred and then allowed to stand to observe the dissolution process of each sample. It can be seen that the dissolution phenomenon of the solid dispersion system with PVP is obvious, and a yellow transparent solution is obtained as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Dissolution of pure myricetin and three types of solid dispersion samples.

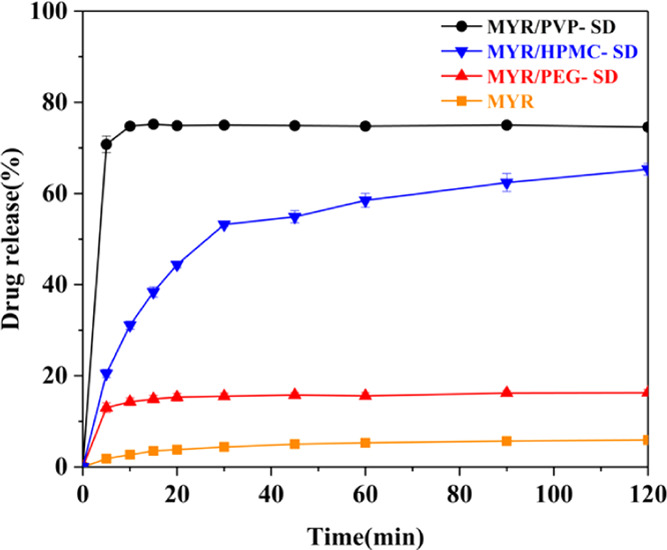

3.3.2. Dissolution In Vitro Analysis

The dissolution experiment is more intuitive to compare and analyze the dissolution and release of the antioxidant in the solid dispersion.28 The results are shown in Figure 14. The dissolution platform of the three solid dispersions is higher than that of pure MYR, and the order is MYR/PVP-SD > MYR/HPMC-SD > MYR/PEG-SD, which agrees well with the simulation predictions from ΔEmix, Ebinding, ΔG, and CHBs values. It is proved that the combination of ideal dispersibility and strong interaction can improve the solubility.

Figure 14.

Dissolution curves of pure myricetin and three solid dispersion systems.

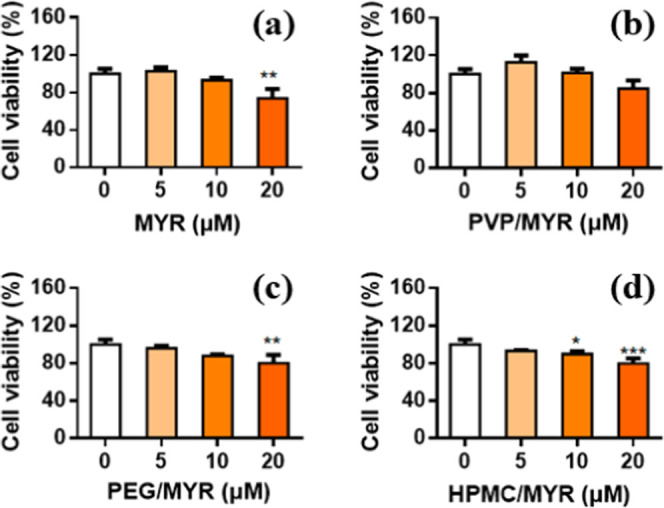

3.4. Effects of Myricetin and Its Solid Dispersions on the Cell Viability and Intracellular ROS Level

Myricetin and its solid dispersions were incubated with HUVECs for 24 h at different concentrations. Results showed that no significant cytotoxic effects were detected on the cell viability when the concentration of myricetin was not higher than 10 μM (Figure 15). In addition, it can be noticed that the cells incubated with PVP/MYR-SD displayed a higher viability than those with myricetin alone or with the other two solid dispersions when myricetin was at equimolar concentrations.

Figure 15.

Relative viability of HUVECs incubated with myricetin and its solid dispersions for 24 h at different concentrations: (a) pure MYR, (b) PVP/MYR-SD, (c) PEG/MYR-SD, and (d) HPMC/MYR-SD.

The intracellular ROS level was examined to characterize the free radical scavenging activity and antioxidant performance of myricetin and its solid dispersions.56 The results are shown in Figure 16. The negative control group is a group without hydrogen peroxide, while the CON group is a positive control group with hydrogen peroxide without myricetin and its solid dispersion samples, and the rest of the groups are added with hydrogen peroxide. The ability of 10 μM antioxidants to reduce ROS levels in cells is also listed as PVP/MVR-SD > HPMC/MVR-SD > PEG/MVR-SD > MYR. It can be seen that the solid dispersion of the PVP system displayed a lower median fluorescence intensity (MFI) than the others, suggesting the increased myricetin released from the PVP-based solid dispersion and played a stronger oxygen scavenging activity.

Figure 16.

Scavenging ability of myricetin and its solid dispersion to intracellular ROS. The concentration of myricetin in the tested groups was 10 μM.

The cell experiment is based on the dissolution results. The more dispersed myricetin is, the more significantly it can be released in the cell and even the biological system, and the more effective its medicinal properties will be. The addition of cell experiments can better reflect the practical significance of this set of research.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, through the quantum mechanics and molecule dynamic simulations combined with experiments from the two microscopic perspectives of dispersibility and intermolecular interaction, the factors affecting the myricetin–polymer solid dispersions are discussed. The optimal candidate polymer excipient for myricetin is screened out from PVP, HPMC, and PEG polymers. The main conclusions are as follows.

-

(1)

Judging from the dispersibility of myricetin in the polymer, the solid dispersion is better than the physical mixture, indicating the effectiveness of the solid dispersion modification. In addition, PVP can better inhibit the agglomeration of myricetin compared with HPMC and PEG and present the effect of significantly destroying the myricetin crystallization. These are based on characterizations of DSC–TG, SEM, and XRD experiments and theoretical analyses of Flory–Huggins parameters (χ), mixing energy (ΔEmix), mean square displacement (MSD), and binding energy (Ebinding) data from molecular simulations.

-

(2)

The hydrogen-bond interactions in solid dispersions of myricetin and the three polymer excipients are confirmed from FTIR experiments. Compared with MYR/PEG-SD and MYR/HPMC-SD, the intermolecular hydrogen bond in the MYR/PVP-SD system has a stronger effect and a higher molar concentration, which corresponds to the result of dispersion states. These conclusions are based on the FTIR characterization and the discussion of simulation parameters of strength and concentration of hydrogen bonds.

-

(3)

In terms of experimental and simulation results, the PVP/MYR-SD exhibits superior solubility compared to the other two solid dispersion systems. The dissolution characterization shows the superiority of this group of samples, which is consistent with the simulation data. Cell viability characterization and ROS-level detection experiments also confirmed the superiority of PVP/MYR-SD in scavenging active oxygen free radicals and antioxidation in biological systems.

This study analyzed the solubilization effect of polymer excipients on myricetin from the molecular level and screened the selected polymers. It may provide new ideas for the design and modification of drugs.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Materials

The myricetin (MYR) was supplied by Bide Pharmatech Ltd, Shanghai, China. Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) was achieved from Beijing Solabio Science& Technology Co., Ltd, China. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) was provided from Meryer (Shanghai) Chemical Technology Co., Ltd, China. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry CO., Ltd, Japan. Both absolute ethanol and dichloromethane are industrial grade, used as solvents. All of the above raw materials were put into use directly without further treatment.

5.2. Preparation of Polymer Excipient/MYR Solid Dispersion (SD) and Physical Mixture (PM) Samples

First, a certain mass of MYR and polymer excipients (w/w 1:9) was weighed and dissolved in a mixed solvent of ethanol and dichloromethane (v/v 1:2).13 After that, magnetic stirring was performed for 1 h to completely dissolve the solid mixture. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation in a water bath at 30 °C. The solid obtained by rotary evaporation was dried under reduced pressure at room temperature for about 8 h, and then, the samples were freeze-dried at low temperature for at least 24 h. Finally, the samples were put into a ball mill tank with liquid nitrogen added in, and a powdery solid dispersion was obtained by pulverizing and passing 80-mesh sieves.37

The myricetin and polymer excipients (PVP/MYR, HPMC/MYR, PEG/MYR) were placed in an agate mortar and ground thoroughly to make physical mixture samples for characterization. Since the content of the antioxidant exceeds a certain critical value, secondary crystallization will occur during the preparation of the solid dispersion. Therefore, the mass fraction of MYR is controlled by about 10% in the solid dispersion as well as that in the physical mixture.

5.3. Measurements and Characterization

5.3.1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Through the X-ray diffraction method, the crystallinities of myricetin, excipients, and respective solid dispersions were determined. Tests were recorded and obtained by an XRD-600 diffractometer (SHIMADZU, Japan). The 2θ range was set from 5 to 80 degree, and the scan rate was 5 degree/min.

5.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The group characteristics and intermolecular interactions in the solid dispersion samples were obtained by Fourier infrared spectroscopy. The samples of pure myricetin, three solid dispersion samples containing three excipients, and their corresponding physical mixture samples were all recorded on the FTIR spectrometer (BRUKER, Germany) with the KBr tablet technology, and the wavenumber of each sample was recorded in the range of 4000–400 cm–1.

5.3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry and Thermal Gravimetry (DSC–TG)

The thermal behavior (crystallization, melting, or glass transition) of myricetin and its solid dispersion under a nitrogen flow were recorded by DSC (NETZSCH, German). The dehydration and thermal decomposition behavior of the sample within a specific temperature range were observed by TG (TA, the United States). The purpose of the combination of the two is to analyze whether myricetin is uniformly dispersed before the sample is thermally decomposed. The test was carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere, at a temperature range of 30–400 °C, and the heating rate was 10 °C/min.

5.3.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

The scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-4800, Japan) was used to observe the microscopic morphology of myricetin and its solid dispersion. The samples were evenly smeared on the surface of the conductive adhesive and sputtered with gold spray coating.

5.3.5. Solubility and Dissolution Characterization

A batch of myricetin–ethanol solution was configured according to a certain concentration gradient, and the UV–vis curve in the range of 450–300 nm was measured by a UV spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, Japan). The absorbance at the maximum absorption peak was monitored, and the standard solubility curve was drawn correspondingly. Then, the linear regression equation of the absorbance–myricetin concentration could be obtained by fitting. At the same time, the excess myricetin and its three solid dispersion samples were stirred in 10 mL of deionized water for 2 h and then passed through the filter membrane to obtain their respective saturated solutions. The absorbance was measured and then substituted into the above linear regression equation to obtain the equilibrium solubility.

The dissolution studies of pure MYR and SD (MYR/PVP, MYR/HPMC, and MYR/PEG) samples were carried out by an automatic dissolution apparatus (FADT-800RC, Japan) in vitro.57 The dissolving media consisted of 0.1 N HCl (900 mL) at 37 ± 0.5 °C, and the stirring speed was 100 rpm. A total of 10 mg of pure MYR and a solid dispersion containing 10 mg of MYR active ingredient samples were immersed in the dissolving medium. The samples were taken out at corresponding time intervals (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min) for testing. A UV spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, Japan) was used to determine the concentration of MYR. The relationship diagram between the drug release amount and time can be established by analyzing the dissolution and release performances of the samples.28

5.3.6. Cell Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, #8000), endothelial cell medium (ECM, #1001), fetal bovine serum (FBS, #0025), penicillin/streptomycin solution (P/S, #0503), endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS, #1052), and poly-l-lysine (PLL, #0403) were all purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories (San Diego, CA). HUVECs were grown on a PLL-coated culture plate in ECM supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% P/S, and 1% ECGS.

5.3.7. Cell Viability Assay

The viability of HUVECs treated with MYR or its solid dispersion was analyzed by applying a cell count kit (CCK-8, Dojindo).58 The MYR or the solid dispersion was diluted in a fresh medium to the final MYR concentrations of 5, 10, and 20 μM and was added to HUVECs, respectively. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with a medium containing 10 μL of CCK-8 reagents for 3 h. The absorbance of the medium was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy4). All measurements were carried out in triplicate, and the cell viability was calculated with the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

5.3.8. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Measurement

The intracellular ROS level was measured using the probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Sigma-Aldrich).56 HUVECs were incubated with the probe for 30 min. After washing, the cells were added with 10 μM MYR or its SD samples, followed by addition of 30 μL of 50 mM H2O2 and 5 min of incubation. The cells were then washed, trypsinized, and collected. The fluorescence intensity was detected by a flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6).

5.3.9. Statistical Analysis

The data are shown as mean ± standard deviation for all treatment groups. Statistical significance was ascertained through one-way ANOVA with SPSS software (SPSS17.0).58

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51873017) and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Science (Grant No. CIFMS 2016- I2M-3-004).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Baghel S.; Cathcart H.; O’Reilly N. J. Polymeric Amorphous Solid Dispersions: A Review of Amorphization, Crystallization, Stabilization, Solid-State Characterization, and Aqueous Solubilization of Biopharmaceutical Classification System Class II Drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 2527–2544. 10.1016/j.xphs.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padrela L.; Rodrigues M. A.; Duarte A.; Dias A. M. A.; Braga M. E. M.; de Sousa H. C. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide-Based Technologies for the Production of Drug Nanoparticles/Nanocrystals – A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2018, 131, 22–78. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y.; Wada K.; Nakatani M.; Yamada S.; Onoue S. Formulation Design for Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs Based on Biopharmaceutics Classification System: Basic Approaches and Practical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 1–10. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. M.; Li Z.; LaBelle A. J.; Bates F. S.; Lodge T. P.; Hillmyer M. A. Impact of Polymer Excipient Molar Mass and End Groups on Hydrophobic Drug Solubility Enhancement. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 1102–1112. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsin M. C.; Tale S.; Reineke T. M. Solution-State Polymer Assemblies Influence BCS Class II Drug Dissolution and Supersaturation Maintenance. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 500–511. 10.1021/bm401431t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A. G.; Lin Y.; Lin R.; Cui H. Molecular Design and Synthesis of Self-Assembling Camptothecin Drug Amphiphiles. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 874–884. 10.1038/aps.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.; Wu L.; Ren X.; Zhang W.; Tang Y.; Chen Y.; Carrier A.; Zhang X.; Zhang J. Hyaluronic-Acid-Based β-Cyclodextrin Grafted Copolymers as Biocompatible Supramolecular Hosts to Enhance the Water Solubility of Tocopherol. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 586, 119542 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dora C. P.; Kushwah V.; Katiyar S. S.; Kumar P.; Pillay V.; Suresh S.; Jain S. Improved Oral Bioavailability and Therapeutic Efficacy of Erlotinib through Molecular Complexation with Phospholipid. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 534, 1–13. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi B.; Abdollahi A.; Roghani-Mamaqani H.; Salami-Kalajahi M. Light-, Temperature-, and PH-Responsive Micellar Assemblies of Spiropyran-Initiated Amphiphilic Block Copolymers: Kinetics of Photochromism, Responsiveness, and Smart Drug Delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2020, 109, 110524 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed E.; Karavasili C.; Ruparelia K.; Haj-Ahmad R.; Charalambopoulou G.; Steriotis T.; Giasafaki D.; Cox P.; Singh N.; Giassafaki L.-P. N.; Mpenekou A.; Markopoulou C. K.; Vizirianakis I. S.; Chang M.-W.; Fatouros D. G.; Ahmad Z. Electrosprayed Mesoporous Particles for Improved Aqueous Solubility of a Poorly Water Soluble Anticancer Agent: In Vitro and Ex Vivo Evaluation. J. Controlled Release 2018, 278, 142–155. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raheem Thayyil A.; Juturu T.; Nayak S.; Kamath S. Pharmaceutical Co-Crystallization: Regulatory Aspects, Design, Characterization, and Applications. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 10, 203–212. 10.34172/apb.2020.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S.; Van den Mooter G. Review: Physical Chemistry of Solid Dispersions. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 61, 1571–1586. 10.1211/jpp.61.12.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboo S.; Kestur U. S.; Flaherty D. P.; Taylor L. S. Congruent Release of Drug and Polymer from Amorphous Solid Dispersions: Insights into the Role of Drug-Polymer Hydrogen Bonding, Surface Crystallization, and Glass Transition. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1261–1275. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b01272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schver G. C. R. M.; Nadvorny D.; Lee P. I. Evolution of Supersaturation from Amorphous Solid Dispersions in Water-Insoluble Polymer Carriers: Effects of Swelling Capacity and Interplay between Partition and Diffusion. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 581, 119292 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schittny A.; Philipp-Bauer S.; Detampel P.; Huwyler J.; Puchkov M. Mechanistic Insights into Effect of Surfactants on Oral Bioavailability of Amorphous Solid Dispersions. J. Controlled Release 2020, 320, 214–225. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha D. K.; Shah D. S.; Amin P. D. Thermodynamic Aspects of the Preparation of Amorphous Solid Dispersions of Naringenin with Enhanced Dissolution Rate. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 583, 119363 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Xu C.; Hao C.; Zhang Y.; Wang Z.; Wang S.; Wang W. Inhibition of Herpes Simplex Virus by Myricetin through Targeting Viral GD Protein and Cellular EGFR/PI3K/Akt Pathway. Antiviral Res. 2020, 177, 104714 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.; Wang J.-J.; Li F.; To S.-S. T. Development and Evaluation of a Novel Drug Delivery: Pluronics/SDS Mixed Micelle Loaded With Myricetin In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 1535–1543. 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziani B. E. C.; Barros L.; Boumehira A. Z.; Bachari K.; Heleno S. A.; Alves M. J.; Ferreira I. C. F. R. Profiling Polyphenol Composition by HPLC-DAD-ESI/MSn and the Antibacterial Activity of Infusion Preparations Obtained from Four Medicinal Plants. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 149–159. 10.1039/C7FO01315A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mureşan-Pop M.; Pop M. M.; Borodi G.; Todea M.; Nagy-Simon T.; Simon S. Solid Dispersions of Myricetin with Enhanced Solubility: Formulation, Characterization and Crystal Structure of Stability-Impeding Myricetin Monohydrate Crystals. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1141, 607–614. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ting J. M.; Porter W. W.; Mecca J. M.; Bates F. S.; Reineke T. M. Advances in Polymer Design for Enhancing Oral Drug Solubility and Delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 939–952. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasi N. S.; Bhujbal S. V.; Zemlyanov D. Y.; Zhou Q.; Tony; Taylor L. S. Physical Stability and Release Properties of Lumefantrine Amorphous Solid Dispersion Granules Prepared by a Simple Solvent Evaporation Approach. Int. J. Pharm. X 2020, 2, 100052 10.1016/j.ijpx.2020.100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee T.; O’Donnell K. P.; Rickard M. A.; Nickless B.; Li Y.; Ginzburg V. V.; Sammler R. L. Rheology of Cellulose Ether Excipients Designed for Hot Melt Extrusion. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 4430–4441. 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.; Walker G. Recent Strategies in Spray Drying for the Enhanced Bioavailability of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. J. Controlled Release 2018, 269, 110–127. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doreth M.; Hussein M. A.; Priemel P. A.; Grohganz H.; Holm R.; Lopez de Diego H.; Rades T.; Löbmann K. Amorphization within the Tablet: Using Microwave Irradiation to Form a Glass Solution in Situ. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 519, 343–351. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo A.; Kumar N. S. K.; Suryanarayanan R. Crosslinking: An Avenue to Develop Stable Amorphous Solid Dispersion with High Drug Loading and Tailored Physical Stability. J. Controlled Release 2019, 311–312, 212–224. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni S.; Albertini B.; Facchini C.; Prata C.; Passerini N. Glutathione-Loaded Solid Lipid Microparticles as Innovative Delivery System for Oral Antioxidant Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 364 10.3390/pharmaceutics11080364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri S.; Imam S. S.; Altamimi M. A.; Hussain A.; Shakeel F.; Elzayat E.; Mohsin K.; Ibrahim M.; Alanazi F. Enhanced Dissolution of Luteolin by Solid Dispersion Prepared by Different Methods: Physicochemical Characterization and Antioxidant Activity. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 6461–6471. 10.1021/acsomega.9b04075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. D.; Lee P. I. Probing the Mechanisms of Drug Release from Amorphous Solid Dispersions in Medium-Soluble and Medium-Insoluble Carriers. J. Controlled Release 2015, 211, 85–93. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera-Giraldo L. I.; Borca C. H.; Meng X.; Edgar K. J.; Slipchenko L. V.; Taylor L. S. Mechanistic Design of Chemically Diverse Polymers with Applications in Oral Drug Delivery. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 3659–3671. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Sun M.; Zhao Y.; Song X.; He Z.; Wang J.; Sun J. Molecular Mechanism of Polymer-Assisting Supersaturation of Poorly Water-Soluble Loratadine Based on Experimental Observations and Molecular Dynamic Simulations. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2017, 7, 738–749. 10.1007/s13346-017-0401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Gao P.; Yang Y.; Guo H.; Wu D. Dynamic and Programmable Morphology and Size Evolution via a Living Hierarchical Self-Assembly Strategy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2772 10.1038/s41467-018-05142-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özeren H. D.; Balçık M.; Ahunbay M. G.; Elliott J. R. In Silico Screening of Green Plasticizers for Poly(Vinyl Chloride). Macromolecules 2019, 52, 2421–2430. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barmpalexis P.; Karagianni A.; Kachrimanis K. Molecular Simulations for Amorphous Drug Formulation: Polymeric Matrix Properties Relevant to Hot-Melt Extrusion. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 119, 259–267. 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapourani A.; Eleftheriadou K.; Kontogiannopoulos K. N.; Barmpalexis P. Evaluation of Rivaroxaban Amorphous Solid Dispersions Physical Stability via Molecular Mobility Studies and Molecular Simulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 157, 105642 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. B.; Davis M. T.; Albadarin A. B.; Walker G. M. Investigation of the Dependence of the Flory–Huggins Interaction Parameter on Temperature and Composition in a Drug–Polymer System. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 5327–5335. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X.; Zhang M.; Hou Q.; Tang P.; Suo Z.; Zhu Y.; Li H. Solid Dispersions of Telaprevir with Improved Solubility Prepared by Co-Milling: Formulation, Physicochemical Characterization, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2019, 105, 110012 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P. K.; Larson R. G. Assessing the Efficiency of Polymeric Excipients by Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1676–1686. 10.1021/mp500068w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsteiner M.; Khinast J.; Paudel A. Relative Contributions of Solubility and Mobility to the Stability of Amorphous Solid Dispersions of Poorly Soluble Drugs: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Pharmaceutics 2018, 101 10.3390/pharmaceutics10030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.; Li B.; Li Y.; Liu Y.; Liu Q.; Jiang H.; He Z.; Zhao Y.; Sun J. Experimental Observations and Dissipative Particle Dynamic Simulations on Microstructures of PH-Sensitive Polymer Containing Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 517, 185–195. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Ren P.; Fried J. R. The COMPASS Force Field: Parameterization and Validation for Phosphazenes. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 1998, 8, 229–246. 10.1016/S1089-3156(98)00042-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K.; You G.; Zhang S.; Zheng W.; Wu S. Antioxidation Behavior of Bonded Primary-Secondary Antioxidant/Styrene-Butadiene Rubber Composite: Experimental and Molecular Simulation Investigations. Polymer 2020, 188, 122143 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.122143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G.-Y.; Hu X.; Wang F.; Li L.-M. An Approach to Reduce the Computational Effort in Accurate DFT Calculations. Chem. Phys. 2003, 290, 163–170. 10.1016/S0301-0104(03)00118-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M.; Evers F. O.; Formalik F.; Olejniczak A. Benchmarking DFT-GGA Calculations for the Structure Optimisation of Neutral-Framework Zeotypes. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2016, 135, 257 10.1007/s00214-016-2014-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.; Zhao X.; Liu L.; Yang R.; Song M.; Wu S. Thermodynamic Analyses of the Hydrogen Bond Dissociation Reaction and Their Effects on Damping and Compatibility Capacities of Polar Small Molecule/Nitrile-Butadiene Rubber Systems: Molecular Simulation and Experimental Study. Polymer 2018, 155, 152–167. 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.09.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truong T.; Dahal D.; Urrutia P.; Alvarez L.; Almonacid S.; Bhandari B. Crystallisation and Glass Transition Behaviour of Chilean Raisins in Relation to Their Sugar Compositions. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125929 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty P.; Lubach J. W.; Hau J.; Nagapudi K. A Rational Approach towards Development of Amorphous Solid Dispersions: Experimental and Computational Techniques. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 519, 44–57. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K.; Ye X.; Zhang H.; Liu J.; Luo Y.; Zhu J.; Wu S. Vulcanization and Antioxidation Effects of Accelerator Modified Antioxidant in Styrene-Butadiene Rubber: Experimental and Computational Studies. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 177, 109181 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2020.109181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q.; Zhang Y.; Wang Y.; Yang M. A Molecular Dynamic Simulation Method to Elucidate the Interaction Mechanism of Nano-SiO2 in Polymer Blends. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 12889–12901. 10.1007/s10853-017-1330-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. S.; Jacobsen E. N. Asymmetric Catalysis by Chiral Hydrogen-Bond Donors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1520–1543. 10.1002/anie.200503132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minch M. J. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding (Jeffrey, George A.). J. Chem. Educ. 1999, 76, 759. 10.1021/ed076p759.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapourani A.; Chatzitheodoridou M.; Kontogiannopoulos K. N.; Barmpalexis P. Experimental, Thermodynamic, and Molecular Modeling Evaluation of Amorphous Simvastatin-Poly(Vinylpyrrolidone) Solid Dispersions. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 2703–2720. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier F. C.; Scalbert J.; Thibault-Starzyk F. Unraveling the Mechanism of Chemical Reactions through Thermodynamic Analyses: A Short Review. Appl. Catal., A 2015, 504, 220–227. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X.; Cao L.; Liu Y.; Dai J.; Liu X.; Zhu J.; Du S. How Does the Hydrogen Bonding Interaction Influence the Properties of Polybenzoxazine? An Experimental Study Combined with Computer Simulation. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 4782–4799. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K.; Zhang F.; Zhang X.; Hu Q.; Wu H.; Guo S. Molecular Insights into Hydrogen Bonds in Polyurethane/Hindered Phenol Hybrids: Evolution and Relationship with Damping Properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 8545–8556. 10.1039/C4TA00476K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T.; Yang A.; Wang T.; Jia M.; Lai X.; Meng J.; Liu J.; Han B.; Xu H. Ultra-Small Platinum Nanoparticles on Gold Nanorods Induced Intracellular ROS Fluctuation to Drive Megakaryocytic Differentiation of Leukemia Cells. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 6204–6211. 10.1039/D0BM01547D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong D. H.; Tran T. H.; Ramasamy T.; Choi J. Y.; Choi H.-G.; Yong C. S.; Kim J. O. Preparation and Characterization of Solid Dispersion Using a Novel Amphiphilic Copolymer to Enhance Dissolution and Oral Bioavailability of Sorafenib. Powder Technol. 2015, 283, 260–265. 10.1016/j.powtec.2015.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T.; Du L.; Chen B.; Yan D.; Yang A.; Liu J.; Gu N.; Meng J.; Xu H. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Reversible Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Vascular Endothelial Cells at Acutely Non-Cytotoxic Concentrations. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 30 10.1186/s12989-019-0314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]