Abstract

Denitrification plays a central role in the global nitrogen cycle, reducing and removing nitrogen from marine and terrestrial ecosystems. The flux of nitrogen species through this pathway has a widespread impact, affecting ecological carrying capacity, agriculture, and climate. Nitrite reductase (Nir) and nitric oxide reductase (NOR) are the two central enzymes in this pathway. Here we present a previously unreported Nir domain architecture in members of phylum Chloroflexi. Phylogenetic analyses of protein domains within Nir indicate that an ancestral horizontal transfer and fusion event produced this chimeric domain architecture. We also identify an expanded genomic diversity of a rarely reported NOR subtype, eNOR. Together, these results suggest a greater diversity of denitrification enzyme arrangements exist than have been previously reported.

Keywords: Chloroflexi, cytochrome, denitrification, nitric‐oxide reductase, nitrite reductase, phylogeny

Nitrite reductase (Nir) and nitric oxide reductase (NOR) are the two central enzymes in denitrification, a key process in the global nitrogen cycle. This study identifies a novel Nir domain architecture and expanded diversity in a rarely reported nitric oxide reductase variant (eNOR) in members of the bacterial phylum Chloroflexi.

1. INTRODUCTION

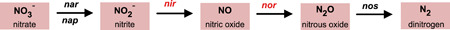

Microbial denitrification is a key pathway in global nitrogen cycling and has been studied extensively for its role in fixed nitrogen loss and as a source of potent greenhouse gases (Decleyre et al., 2016; Zumft, 1997). Diverse bacteria are capable of denitrification, often facultatively using nitrate or nitrite as an alternative electron acceptor in oxygen‐limited zones. Several diverse microorganisms have the genomic capacity to perform complete denitrification (Figure 1), reducing nitrate to dinitrogen gas (Canfield et al., 2010; Philippot, 2002).

Figure 1.

Denitrification. Complete denitrification transforms nitrate into dinitrogen gas. Respiratory nitrate reductase gene (nar) and periplasmic nitrate reductase (nap) genes are distributed in non‐denitrifying organisms. Nitrite reductase (Nir) is considered the canonical first enzyme of denitrification (Graf et al., 2014), followed by nitric oxide reductase (NOR) and nitrous oxide reductase (Nos)

Denitrification has been widely reported in various taxa (Philippot, 2002; Zumft, 1997), and the utility of the pathway is underscored by the diversity of key constituent enzymes. The canonical denitrification enzyme is dissimilatory nitrite reductase, Nir, which reduces nitrite to nitric oxide (NO). Nir functionality is found in two distinct enzymes—the copper‐based nitrite reductase NirK, and the cytochrome‐type reductase NirS (Braker et al., 2000; Decleyre et al., 2016; Priemé et al., 2002). NirS reduces nitrite via cytochrome cd1, a dimer of subunits each containing heme c and heme d1; in canonical denitrification, as observed in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cytochrome cd1 catalyzes the oxidation of a colocalized cytochrome c551 to reduce nitrite to NO at the heme d1 site (Philippot, 2002; Zumft, 1997). The nirS gene has been reported as a constituent of a larger gene cluster containing genes such as nirM and nirF, which encode biosynthetic proteins for the cytochrome c551 and heme d 1 , respectively, and the nitrite transporter nirC (Kawasaki et al., 1997; Philippot, 2002).

The next step in the pathway—the reduction of NO to nitrous oxide—is catalyzed by nitric oxide reductases (NORs). Most bacterial NORs are homologous and closely related to one another, and to oxygen reductases in the heme–copper oxygen reductase superfamily (Hemp & Gennis, 2008). The most widely studied NOR enzymes are cytochrome‐type nitric oxide reductases (cNOR) and quinol‐dependent nitric oxide reductases (qNOR) (Graf et al., 2014; Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Hendriks et al., 2000), distinguished by their respective electron donors. Enzymes in the cNOR subfamily have two subunits—one catalytic site and one heme‐containing electron shuttle that accepts electrons from cytochrome c—while qNOR family enzymes' single, fused subunit accepts electrons from membrane‐bound quinol groups (Hemp & Gennis, 2008). Rarer, alternative NOR enzymes, including sNOR, gNOR, and eNOR, have been more recently identified and characterized in limited members of the Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Archaea, and Chloroflexi (Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Hemp et al., 2015; Sievert et al., 2008; Stein et al., 2007). Like cNOR, these enzymes are predicted to have a two‐subunit structure, but the second subunit in these NORs contains a cupredoxin instead of heme c fold (Hemp & Gennis, 2008).

Many bacteria contain genes encoding only one or a partial subset of the four denitrification steps. Such organisms may perform partial denitrification, while others may use one of these enzymes for nondenitrifying functions (Graf et al., 2014; Hendriks et al., 2000; Roco et al., 2017; Sanford et al., 2012). In partial denitrifiers, the co‐occurrence of denitrification pathway genes appears to vary across different taxa and environments (Graf et al., 2014). Some of this variation may be constrained by the chemistry of certain intermediates. For example, nitric oxide (NO), the product of NirS and NirK, is highly cytotoxic. Both Nir types are periplasmic, and so cells require a means of effluxing or detoxifying NO before it accumulates to lethal levels. Denitrifiers are thought to immediately reduce NO to nitrous oxide (N2O) to avoid injury, using membrane‐bound NOR enzymes (Hendriks et al., 2000). Perhaps, for this reason, it is rare to find genomes that contain nir but not nor, while organisms showing the inverse—the presence of a nor gene but not a nir gene—are far more common (Graf et al., 2014; Hendriks et al., 2000). While cNORs are only found in denitrifying microbes, other types of NOR—for example, quinol‐dependent qNOR—are found in nondenitrifiers and can presumably detoxify environmental NO (Hendriks et al., 2000). Beyond NORs, alternative pathways to NO detoxification are possible, including alternative enzymes such as cytochrome c oxidase (Blomberg & Ädelroth, 2018) or oxidoreductase (Gardner et al., 2002), flavorubredoxin (Gardner et al., 2002), or flavohemoglobins (Sánchez et al., 2011).

While denitrification has been most widely studied and observed in Proteobacteria, the process has also been identified in other phyla, including Chloroflexi. Chloroflexi are ecologically and physiologically diverse, and often key players in oxygen‐, nutrient‐, and light‐limited environments, including anaerobic sludge and subsurface sediments (Hug et al., 2013; Ward, Hemp et al., 2018). Previous surveys have indicated the presence of diverse nitrite reductases in Chloroflexi; members of order Anaerolineales and classes Chloroflexia and Thermomicrobia may have the capacity for nitrite reduction via the copper‐type NirK (Decleyre et al., 2016; Hug et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2015). However, recent studies indicate that certain Chloroflexi—including members of Anaerolineales—may possess nirS instead of nirK (Hemp et al., 2015; Ward, McGlynn et al., 2018), and may also harbor a divergent variant of nor previously reported in members of Archaea (Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Hemp et al., 2015). These findings suggest that the evolution and/or biochemistry of denitrification may be unusual for this subset of bacteria, and informative for a broader understanding of microbial denitrification metabolisms and their origin.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

2.1. Genome sampling and assembly

Collection of all fluid samples and total genomic DNA extractions from those fluids, as well as corresponding physical and geochemical data, have been described previously (Heard et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2014, 2016; Magnabosco et al., 2016; Momper & Jungbluth, 2017; Momper & Kiel Reese, 2017; Osburn et al., 2014). All metagenome‐assembled genomes (MAGs) from North America and Africa were reconstructed according to the methods used in Momper and Jungbluth (2017). MAG identifiers and sources are listed in Table A5. Completeness was calculated using the composite values from five widely accepted core essential gene metrics. Duplicate copies of any of these single‐copy marker genes were interpreted as a measure of contamination (Alneberg et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2013; Creevey et al., 2011; Dupont et al., 2012; Wu & Scott, 2012). Individual genomes were then submitted for gene calling and annotations through the DOE Joint Genome Institute IMG‐ER (Integrated Microbial Genomes expert review) pipeline (Huntemann et al., 2015; Markowitz et al., 2008). For quality control purposes, the genes flanking every denitrification gene presented in this study were individually searched on the National Center for Biotechnology Information's (NCBI) RefSeq database using the BLASTp algorithm, confirming that top hits for all flanking genes were also to Chloroflexi. This step ensured that the nitrogen transforming genes of interest presented here were not simply on scaffolds that were incorrectly binned into a putative Chloroflexi genome.

2.2. Genetic database construction and sequence sampling

Sequences for nirS and eNOR genes from Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) MAG 42 (see Table A5) were used as queries to BLAST (Camacho et al., 2009) three genomic repositories:

-

1.

Genome databases constructed for 21 Chloroflexi genomes assembled from deep‐subsurface MAG data (Jungbluth et al., 2017; Momper & Jungbluth, 2017; Table A5).

-

2.

Genome databases constructed for 86 genomes from recent MAG assembled sludge bioreactor genomes (Parks et al., 2017; Table A6).

-

3.

The full NCBI nonredundant protein database (as of September 25, 2019; Agarwala et al., 2018).

Additionally, putative environmental homologs were evaluated using protein sequence data from SURF MAG 42 to query NCBI's nonredundant environmental metagenomic sequence database (env‐nr, as of June 2020; Agarwala et al., 2018). Hits from all databases were combined and assessed for quality; hits with E ≤ 1 × 10−10 were included for initial analyses. To capture diversity while limiting imprecision and biased sampling of overrepresented groups (e.g., Proteobacteria), hits were subsampled to the genus level, except for members of the Chloroflexi (to fully capture the taxonomic distribution of the novel gene variant). One additional, divergent multispecies hit was allowed per genus. The genus‐level filter was also removed for C1, where non‐Chloroflexi hits were severely limited (see below). Duplicate sequences (from strains with multiple genome entries or in multiple databases surveyed) were removed. Expanded database hits and filtering data are available as Supporting Information Data Files at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14515554.v2.

2.3. Sequence alignment

Putative homologous protein sequences were aligned with MAFFT, using autoparameterization (Nakamura et al., 2018), and visualized in Jalview (A. M. Waterhouse et al., 2009). Alignments were manually curated; partial sequences with substantial missing regions or anomalous insertions in conserved regions of the protein were removed to avoid confounding phylogenetic analyses and evolutionary model selection. Protein sequence alignments were trimmed to the length of individual domains identified by NCBI's Conserved Domains Database (CDD). Each domain was then realigned.

2.4. eNOR

A preliminary alignment for the eNOR gene showed a poorly conserved region near the C‐terminal end of the open reading frame (ORF); to improve accuracy and avoid misalignment, this region was manually removed, and the remaining sequences were realigned before tree construction. Two sequences (Actinobacteria bacterium RBG_16_68_12, OFW73639.1, and Thermus WP_015717644.1) with missing N‐terminal regions and three sequences (Chloroflexi bacterium, RME47896.1; Rhodocyclaceae bacterium UTPRO2, OQY7467.1; and Rhodothermus profundi, WP_072715415.1) with missing C‐terminal regions were included in the final alignment; the placement of these sequences is therefore based upon fewer alignment sites than other taxa. All retain key active site residues and show no clear evidence of long‐branch attraction artifacts in the tree.

2.5. C1

An initial alignment for the C1 domain showed a poorly conserved N‐terminal region. To improve accuracy, this region was manually removed, and the remaining sequences realigned before tree construction.

2.6. NirS

Because the NirS domain had a C‐terminal placement in the ORF across hits, C‐terminal sites extending beyond the identified NirS domain were included in the trimmed alignment.

2.7. Rooting and outgroup identification

2.7.1. eNOR

Ingroup eNOR subunit I sequences were identified by the presence of a conserved Gln residue in alignment position 323. This site distinguishes eNOR not only from other NORs but also from members of the oxygen reductase superfamily, which have a conserved Tyr in this site that plays a role in cofactor crosslinking (Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Table A4). Outgroup sequences (oxygen reductase superfamily or other divergent NORs) were subsampled to a single taxon representative per major subgroup observed in a preliminary tree. Retained outgroup sequences CCQ74688.1, WP_100277903.1, WP_097280063.1, WP_089728124.1, RLC59399.1, and WP_083704903.1 are annotated as uncharacterized domains. The remaining sequences were realigned before tree construction and manually rooted on the branch leading to the outgroup.

2.7.2. C1

Due to a paucity of initial hits (17 total genera), the genus‐level filter was removed for all phyla to increase the resolution of the domain phylogeny. A preliminary tree (Figure A8) was expanded to identify outgroup sequences by including hits with E ≤ 10−4. The resulting tree was rooted using minimal ancestor deviation (MAD) rooting (Tria et al., 2017).

2.7.3. C2 and NirS

Sequences were rooted using MAD rooting (Tria et al., 2017).

2.8. Tree construction

Maximum‐likelihood trees were constructed using IQ‐Tree (Nguyen et al., 2015), under the optimal model defined by the ModelFinder (‐MFP) command (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017; Table A7). Ultrafast bootstraps and approximate likelihood ratio tests were performed using IQ‐Tree's ultrafast bootstrap and Sh‐aLRT parameters (Hoang et al., 2018; Minh et al., 2013). Full domain and gene sequences, sequence alignments, and raw treefiles are available as Supporting Information Data Files at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14515554.v2.

2.9. Gene and enzyme structural analysis

FIND (Murali et al., 2019) was used to identify structural features and conserved denitrification pathway genes in deep subsurface genomes. Putative domains within denitrification gene ORFs were identified and compared across genomes using BLAST and NCBI's CDD (S. Lu et al., 2020; Marchler‐Bauer et al., 2015) and EMBL InterPro (Mitchell et al., 2019). C1 from SURF MAG 42 was classified by CDD as COG4654 (e = 6.4 × 10−4) and by hmmscan (Potter et al., 2018) as cytochrome c superfamily (accession 46626) hit (e = 1.6 × 10−5). C1 did not show a strong pfam match in hmmscan; the closest match was PF13442.8 (independent e = 0.18). C2 from SURF MAG 42 was classified by CDD as COG2010 (e = 5.31 × 10−9), and included an annotated region classified as pfam 13442 (e = 4.06 × 10−7); C2 was identified in hmmscan as a cytochrome c superfamily (accession 46626) hit (e = 1.2 × 10−17), with a pfam match to PF13442.8 (independent e = 2.8 × 10−10). While clearly homologous, the C1 and C2 families appear distantly related and do not appear within the other's data set of closely related sequences (see above). Gene neighborhoods were visualized using Gene Graphics (Harrison et al., 2018), using a 20,000 base pair region. Gene and domains identified in each neighborhood were sourced and cross‐referenced with NCBI's RefSeq and CDD (Marchler‐Bauer et al., 2015; O'Leary et al., 2016). Existing enzyme structures for canonical denitrification genes were downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000). Anaerolineales‐type enzyme structures were predicted using SWISS‐MODEL (A. Waterhouse et al., 2018). All enzyme structures were visualized and analyzed in PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0, Schrödinger, LLC). SWISS‐MODEL outputs are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14515554.v2.

3. RESULTS

To investigate divergent denitrification genes in Chloroflexi, we performed a comprehensive analysis of denitrification homologs in over 100 recently sequenced Chloroflexi MAGs, as well as previously available genomes and metagenomes from the NCBI protein databases. Domains of interest were initially identified in SURF MAG 42, an Anaerolineales bacterium sampled in the SURF, a former gold mine in South Dakota (Momper & Jungbluth, 2017).

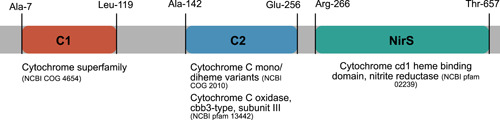

3.1. Apparent chimeric fusion in Chloroflexi NirS

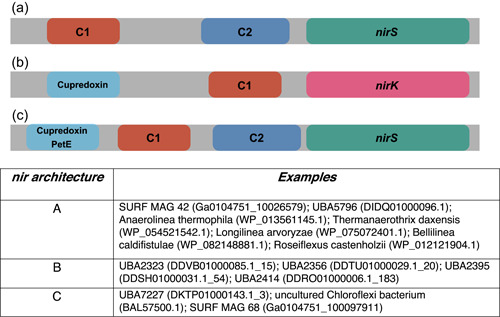

Domain analysis of the Anaerolineales‐type nitrite reductase ORF from SURF MAG 42 indicated three putative functional regions of interest: one cytochrome‐type NirS domain and two cytochrome c superfamily domains (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Open reading frame domain map. Conserved domain analysis of SURF MAG 42 Chloroflexi nitrite reductase (GenBank RJP53747.1) indicates the presence of two distinct cytochrome superfamily domains and a C‐terminal nitrite reductase domain. MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome; SURF, Sanford Underground Research Facility

The first cytochrome domain (C1) in the Anaerolineales‐type ORF was identified by NCBI's CDD (S. Lu et al., 2020; Marchler‐Bauer et al., 2015) as a cytochrome c551/552. The second cytochrome domain (C2) was predicted with high specificity as a cytochrome c mono‐ and diheme variant. C2 included a region predicted as a cbb3‐type cytochrome c oxidase subunit III; such subunits frequently contain two cytochromes (Bertini et al., 2006).

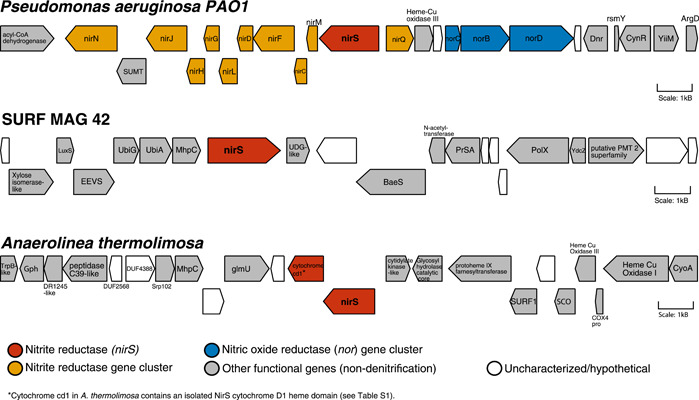

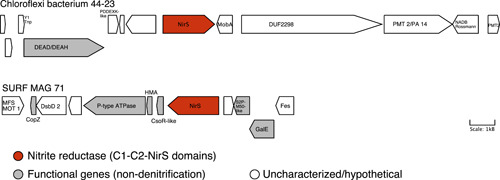

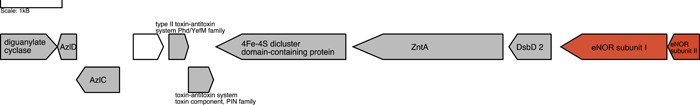

Gene neighborhood analyses indicated that the MAG‐derived nitrite reductase ORF displays a very different local genomic environment as compared with a canonical nitrite reductase neighborhood in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Figure 3). In P. aeruginosa, nirS (NCBI reference sequence NP_249210.1; O'Leary et al., 2016) co‐occurs with other genes in the nir operon and is closely adjacent to genes encoding a cNOR. This arrangement places nitrite reduction in cis with NO reduction, the next step of canonical denitrification. In the Chloroflexi MAG, no other denitrification genes appear within a 20,000 base pair neighborhood for the C1‐C2‐NirS nitrite reductase. A similar pattern is observed for a homologous C1‐C2‐NirS nitrite reductase gene identified in the Chloroflexi Anaerolinea thermolimosa (Matsuura et al., 2015); the A. thermolimosa neighborhood also shows no evidence of other denitrification genes in the immediate vicinity of the novel NirS, though it does contain some ORFs with predicted functionality similar to those in the SURF MAG 42 neighborhood (Figure 3). Full descriptions of all gene abbreviations are provided in Table A1. Analyses of additional selected C1‐C2‐NirS ORF neighborhoods within other Chloroflexi reveal diverse genetic assemblages also dissimilar to the canonical Pseudomonas operon (Figure A1, Table A2).

Figure 3.

NirS gene neighborhood in SURF MAG 42 versus Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene neighborhood analyses of the 20,000 base pair region surrounding nirS differ markedly between P. aeruginosa PAO1 (GenBank reference sequence NP_249210.1, top) and two Chloroflexi genomes containing the C1‐C2‐NirS gene: SURF MAG 42 (center) and Anaerolinea thermolimosa (bottom). While the P. aeruginosa nitrite reductase occurs as part of a larger nir operon, and in close proximity to nitric oxide reductase genes, the nirS ORF neighborhoods in SURF MAG 42 and A. thermolimosa do not appear to contain other denitrification‐specific genes. Detailed descriptions of ORF/gene families and functions can be found in Table A1. MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome; ORF, open reading frame; SURF, Sanford Underground Research Facility

Conserved domain analysis of NirS homologs in this study suggests that while the C2 and NirS functional domains frequently co‐occur in nitrite reductases, the inclusion of C1 in the ORF appears extremely rare and limited to Chloroflexi. A lineage‐specific fusion of multiple gene domains could explain this novel C1‐C2‐NirS arrangement. Different evolutionary histories among the domain subunits within Chloroflexi would provide evidence for an ancestral horizontal acquisition and fusion event.

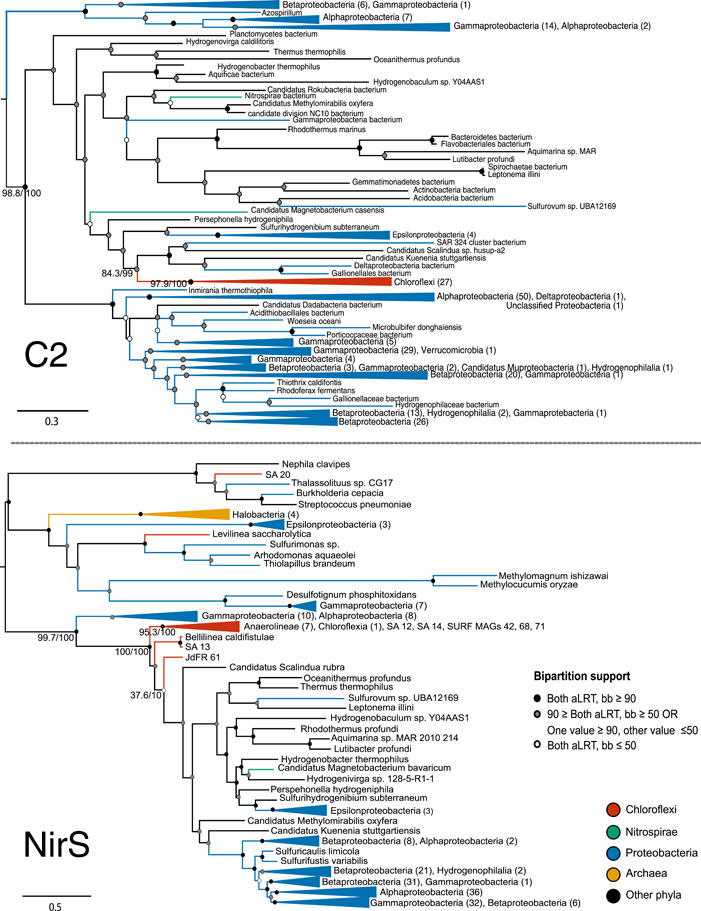

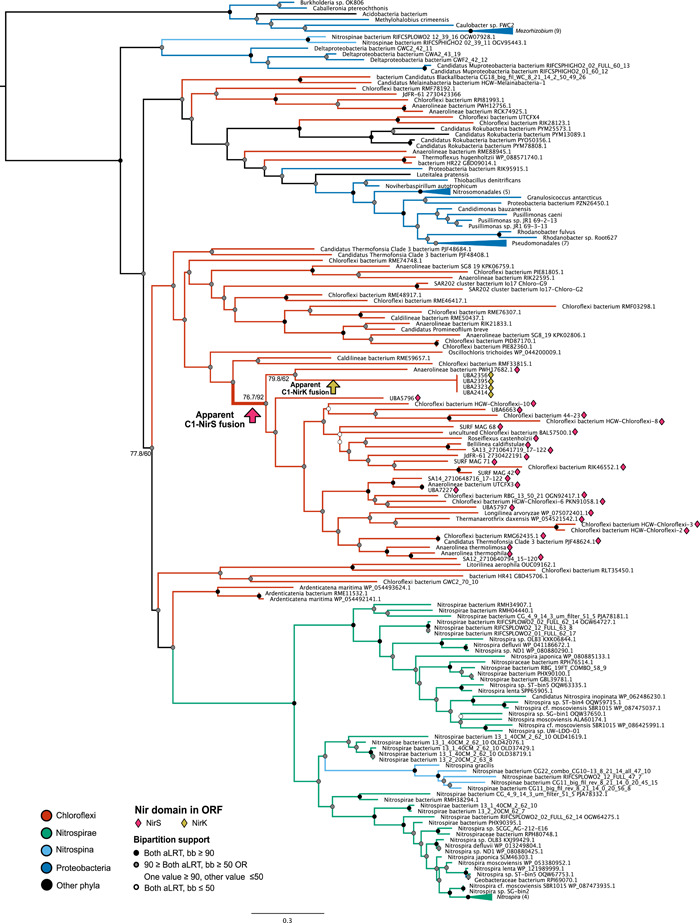

To compare the evolutionary histories of each domain in the enzyme ORF, and to determine if the different domains have different ancestry, maximum‐likelihood domain trees were reconstructed independently for C1, C2, and the NirS‐specific domain (see Methods).

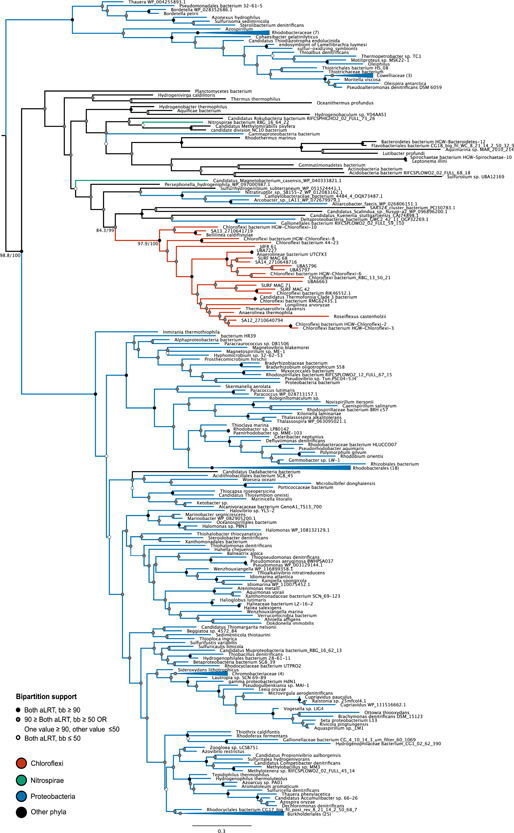

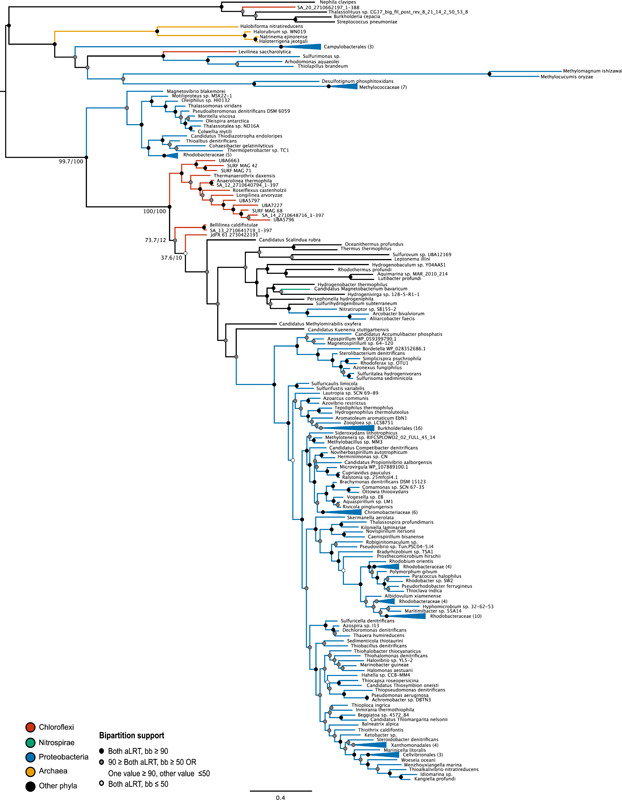

Domain phylogenies indicate similar taxonomic distributions for the C2 and NirS domains (Figure 4). The relative placement of Chloroflexi sequences varies slightly between domain trees: For the C2 domain tree, Chloroflexi sequences are monophyletic within a larger clade comprising polyphyletic sequences including members of the Aquificae, Bacteroidetes, Epsilonproteobacteria, and Spirochaetia; this clade places sister to a large group dominated by Alpha‐, Beta‐, and Gammaproteobacteria (expanded tree available as Figure A2). In the NirS domain tree, Chloroflexi place basally in a clade shared with both polyphyletic sequences and the large radiation of Proteobacterial sequences (expanded tree available as Figure A3).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees for C2 and NirS domains. Phylogenetic analysis of C2 domain homologs (above) places the Chloroflexi within a diverse clade including Epsilonproteobacteria, Aquificae, Bacteroidetes, and Planctomycetes; this clade is sister to a broad radiation of Alpha‐, Beta‐, and Gammaproteobacteria. Analysis of NirS domain homologs (below) places the Chloroflexi within the clade dominated by Alpha‐, Beta‐, and Gammaproteobacteria, which also contains members of the Bacteroidetes and Aquificales. The overall taxonomic representation for the domains is similar. Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray)

C2 and NirS domain trees reconstructed exclusively from ORFs containing both domains produce similar topologies, albeit with slightly different placement of these major groups of taxa (Figures A4 and A5). Interestingly, the subsampling inverts the placements of the Chloroflexi with respect to the largest Proteobacterial group, as compared with the unsampled trees. This change suggests that sampling and phylogenetic noise are likely responsible for the observed differences in the C2 and NirS domain phylogenies. Additionally, there are notable differences in placement among subclades within the Proteobacteria, and low bipartition support for these subclades for the C2 tree, suggesting that patterns unrelated to Chloroflexi evolution may be polarizing the relative placements of groups in the tree. This lack of robustness caused by alternative sampling, combined with poor support values within the polyphyletic clade or between this clade and the Proteobacteria, suggests that the differences in tree topology may be artifactual, and not reflective of gene reticulation events.

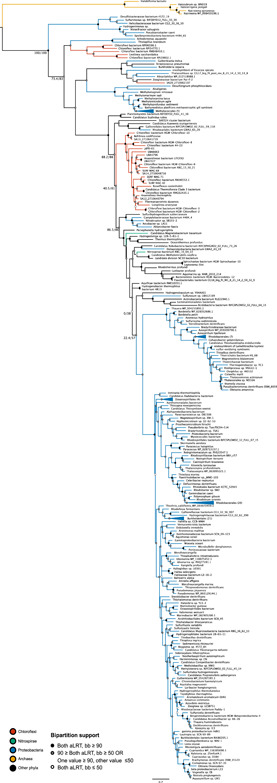

The inferred phylogeny for C1 shows a much different evolutionary history than the other two domains (Figure 5). In contrast to the domain trees for C2 or NirS, the C1 tree shows sequences from Nitrospirae and Nitrospinae grouping together within a large clade of Chloroflexi C1 domains. Additional Chloroflexi sequences group with a small number of more distantly related Proteobacteria. However, the placement and taxonomic representation of Proteobacteria in the C1 tree is different from that seen in the other domain trees.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree for C1 domain. A phylogenetic tree for the C1 domain—with no genus‐level filter and inclusion of more distant hits (see Methods)—indicates a limited taxonomic distribution of the domain. The largest group of sequences in Chloroflexi places sister to domains found in Nitrospirae, Nitrospinae, and Deltaproteobacteria. Within this clade, the branch along which C1 is inferred to have fused into nitrite reductase genes in Chloroflexi is labeled. C1 homologs that co‐occur in ORFs with nitrite reductase are indicated with magenta diamonds (NirS) or yellow diamonds (NirK). Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray). ORF, open reading frame

The majority of ORFs represented in the C1 domain tree contain the C1 domain homolog either as a free cytochrome or as one of multiple cytochrome‐type or cytochrome superfamily domains. In rare or isolated cases, C1 homologs co‐occur in ORFs with membrane or structural protein domains (Table A3). The ORF containing the C1 homolog was annotated as a NOR in several members of the Nitrospirae and one Geobacteraceae genome (Table A3); domain analysis of these genes yielded limited additional data, but representative sequences showed detectable sequence similarity to Pseudomonas norC genes.

The occurrence of C1 domain homologs within predicted nitrite reductase genes is restricted to the Chloroflexi. The majority of these C1‐containing nir genes have the cytochrome‐type NirS domain; however, a small number of Chloroflexi MAGs contain an ORF pairing the C1 cytochrome with the copper‐type NirK domain instead. This NirK ORF also included an N‐terminal cupredoxin/plastocyanin domain. As this fusion is only apparent within a small number of MAGs, which are identical across the length of the analyzed ORF, this may represent an assembly artifact. However, several of the nir genes that contained a C1 homolog and a cytochrome‐type NirS (not copper‐type NirK) also contained cupredoxins or other copper‐containing domains (Figure A6).

The distinct phylogeny and taxonomic distribution of C1, as compared with C2 and NirS domains, strongly suggest that the C1‐C2‐NirS domain structure observed in Chloroflexi is the result of a fusion of the C1 domain with a horizontally‐acquired nir gene containing the C2 and NirS domains. Topology and extant taxon sampling of these gene trees does not allow us to reliably infer the donor lineage of this transfer. However, the C2‐NirS architecture—or similar arrangements of functional domains—is widespread among members of the Alpha‐, Beta‐, and Gammaproteobacteria; additionally, gene trees for C2 and NirS place the Chloroflexi that also contain the C1 domain within (Figure 4) or as sister to (Figures A4 and A5) Proteobacterial groups, inconsistent with species tree placements for these phyla. These data suggest the Proteobacteria as a possible donor group for the C2‐NirS domains. Additionally, it appears that Chloroflexi may have been the source for an independent transfer of the free C1 domain into Nitrospirae and Nitrospinae.

3.2. C1‐C2‐NirS domain architecture is unique to Chloroflexi

Though putative homologs exist independently for the constituent C1 and C2‐NirS regions, respectively, these hits reflect different cytochrome or cytochrome‐type nitrite reductases (largely in Proteobacteria, Nitrospirae, and Nitrospinae). The full C1‐C2‐NirS architecture appears unique to Chloroflexi and is not observed in other groups. Querying NCBI's nonredundant environmental database (env‐nr) with the full ORF from SURF MAG 42 did not identify additional examples of the full gene construct. While several hits were identified that reflected putative homology to the joint C2‐NirS domains, none of these included the C1 domain as well. An independent search of the env‐nr database using the C1 domain as a query returned few overall hits. While some of these putative C1 homologs were identified in ORFs containing additional cytochrome‐type enzyme superfamily domains or subunits, none co‐occurred with NirS or NirK domains. These data suggest that there is little to no missing diversity of the Chloroflexi‐type chimeric nitrite reductase in existing metagenomes.

Attempts to visualize the full enzyme structure using homology modeling (Bienert et al., 2017; A. Waterhouse et al., 2018) were unsuccessful; structural models were only able to predict a close match for the conserved C2‐NirS region of the putative gene. Efforts to independently model the C1 structure could not recover predicted QMEAN scores above −4.50 (Benkert et al., 2011). The poor scores may reflect the relatively short length of the cytochrome coding region. However, the Chloroflexi nirS gene sequence does retain several conserved residues present in the crystal structure of P. aeruginosa NirS. In P. aeruginosa NirS, His51, and Met88 coordinate heme c; His182 coordinates heme d1; and His327 and His369 are believed to stabilize the active site nitrite anion (Maia & Moura, 2014; Rinaldo et al., 2011). Corresponding residues are conserved within the C2 (His65, Met125) and NirS alignments (His46, His239, His300) for the Chloroflexi NirS ORF; interestingly, the residue corresponding to His327 (His239) is not universally conserved, though it is conserved among Chloroflexi with the novel NirS architecture.

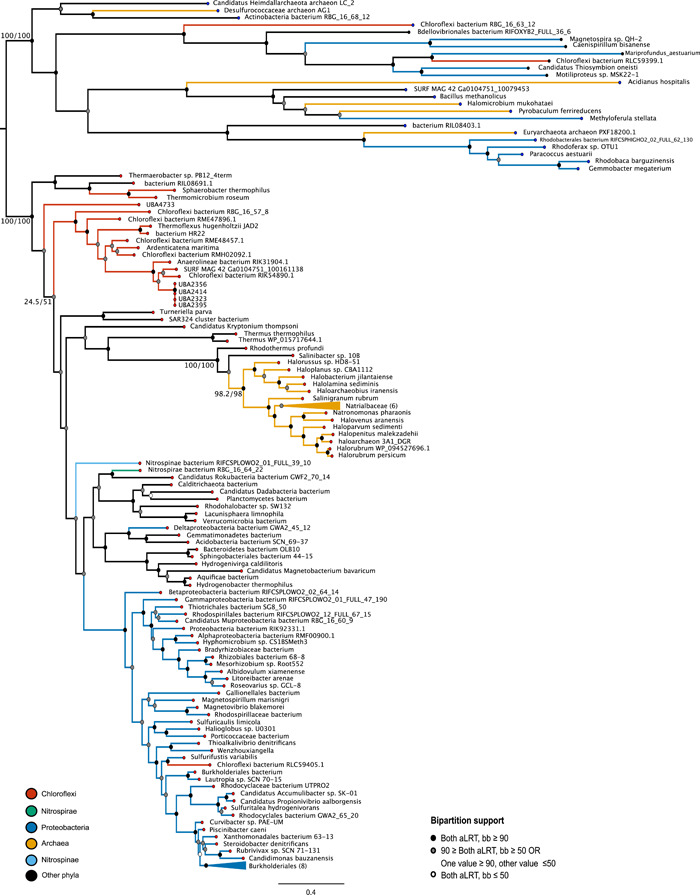

3.3. Expansion of eNOR diversity

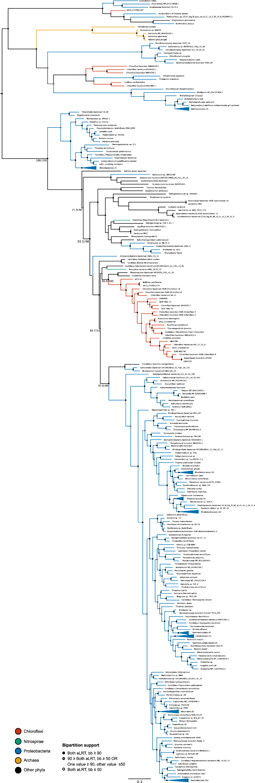

Notably, the majority of genomes with the unique C1‐C2‐NirS structure do not appear to contain a NOR gene (nor). Though the absence of the nor gene in genomes with nirS is not unprecedented, previous genomic surveys suggest it is relatively uncommon, and the toxicity of the product of Nir (NO) makes this absence counterintuitive (Graf et al., 2014; Hendriks et al., 2000). However, analysis of the SURF MAG 42 metagenome—the originally assembled genome in which the novel nirS ORF was observed—did reveal the presence of an unusual nor homolog. Previous studies have identified the established cNOR and qNOR family enzymes (which contain cytochrome c or quinols as electron donors, respectively) in Chloroflexi, as well as a broad distribution of Proteobacteria (Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Hendriks et al., 2000; Zumft, 2005). However, the predicted NOR in SURF MAG 42 included an active site glutamine substitution characteristic of eNOR (Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Hemp et al., 2015; Table A4). SURF MAG 42 contains both proposed subunits (Hemp & Gennis, 2008) of eNOR; the diagnostic subfamily substitution is within the heme‐copper cytochrome‐containing subunit I, and the cupredoxin‐containing subunit II is immediately upstream in the MAG (Figure A7). eNOR has been previously described in Archaea (Hemp & Gennis, 2008) and at least one isolated Anaerolineales bacterium (Hemp et al., 2015).

Phylogenetic analysis indicates the presence of eNOR in an expanded diversity of genomes (Figure 6). Previous studies have described eNOR in Natronomonas; these data indicate a cluster of eNOR genes throughout other Halobacteria as well. Additional putative eNOR genes appear in multiple members of Anaerolineales, as well as other Chloroflexi, and in many members of the Alpha‐, Beta‐, Gamma‐, and Deltaproteobacteria. Many of these putative eNOR subunit homologs appear to have been misannotated or mislabeled as cytochrome c oxidase genes, likely because of the structural similarity of the heme–copper cytochrome region (Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Marchler‐Bauer et al., 2015).

Figure 6.

eNOR gene tree. A phylogenetic tree of homologs to the nitric oxide reductase from SURF MAG 42 reveals an expanded diversity of putative eNOR subunit I homologs in not only Archaea and Chloroflexi, but also Proteobacteria and other diverse phyla. Putative eNOR sequences (red tips) have the characteristic Gln‐323 in the alignment; outgroup sequences (blue tips) have Tyr‐323 (oxygen reductase superfamily) or other substitutions. Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray). MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome; SURF, Sanford Underground Research Facility

4. DISCUSSION

The phylogenetic analyses of nirS and eNOR ORFs in Chloroflexi suggest that subsurface ecosystems may harbor an under‐described diversity of denitrification enzymes, which may reflect adaptations to the unique challenges of nutrient cycling within these environments. More broadly, a deeper understanding of the ecological extent of microbial denitrification has important implications for basic and applied microbial ecology. The reduction of fixed nitrogen species plays a crucial role in global nitrogen cycling and is also an essential component of smaller‐scale systems, such as those associated with agricultural or waste treatment (Butterbach‐Bahl & Dannenmann, 2011; H. Lu et al., 2014). The discovery and characterization of novel variants of genes such as nirS and eNOR may therefore pave the way for future biotechnological applications.

Although the C2 and NirS domains do not have identical evolutionary histories or distributions, the taxonomic representation of these groups is very similar, and the presence of the paired C2‐NirS domains in cytochrome‐type nitrite reductases appears broadly throughout the Proteobacteria. In contrast, the taxonomic distribution and phylogeny of the C1 domain tree are strikingly different than that of the other domains in the nitrite reductase ORF. Combined with the apparent absence of a full C1‐C2‐NirS ORF in any taxonomic group other than Chloroflexi, these data suggest that the C1 cytochrome was likely incorporated into nirS in a gene fusion event within Chloroflexi, following HGT. As there is no evidence of the C2‐NirS ORF in Chloroflexi without the fused C1 domain present, the fusion probably occurred very soon after the acquisition of the C2‐NirS region and may be necessary for the function of the gene in Chloroflexi.

In P. aeruginosa, cytochrome c551—encoded by nirM—is the electron donor for the adjacent cytochrome cd1 nirS (Philippot, 2002; Zumft, 1997). Homology searches do not identify any regions within SURF MAG 42 with significant similarity to Pseudomonas nirM, but C1 is identified as a putative member of the cytochrome c551/552 family. It is, therefore, possible that C1, though divergent from Proteobacterial nirM, serves a similar redox role for the cytochrome cd1 now within the same ORF.

Interestingly, putative homologs of C1 cytochrome domains were found in some Chloroflexi genomes in ORFs containing nirK, not nirS (Figures 5 and A6). Though NirS and NirK are functionally equivalent, the two enzymes do not show a shared evolutionary origin and are often—though not always—mutually exclusive among known denitrifier genomes (Graf et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2008). Unlike the cytochrome‐containing NirS, NirK is a copper‐type enzyme. The co‐occurrence of cytochrome c domains in ORFs with the copper‐type nirK has been identified in rare instances in Proteobacteria, and noted as surprising, given the cupredoxin‐like fold of the NirK enzyme (Bertini et al., 2006). Similarly surprising is the inverse relationship revealed in the C1 domain tree: Several Chloroflexi ORFs contain a cupredoxin or similar copper‐containing domain N‐terminal to the C1‐C2‐NirS architecture (Figure A6, Table A3). The co‐occurrence of C1 with both cytochrome‐ and copper‐dependent Nir domains suggests a general evolutionary trend within Chloroflexi to incorporate this cytochrome into denitrification ORFs. This distribution pattern raises the possibility that the C1‐type cytochrome may serve an important but generalized role in nitrite reduction—regardless of the evolutionary history or genetic profile of the nitrite reduction domain itself.

The apparent absence of a nor homolog in the majority of genomes with the C1‐nirS fusion is unexpected. Beyond providing downstream redox capacity, NOR provides an efficient means of reducing and detoxifying NO, the highly cytotoxic product of NirS. It is not unprecedented for bacterial genomes to harbor a nir gene without a nor gene, particularly for organisms with nirK (Graf et al., 2014; Heylen et al., 2007). This nir–nor mismatch is much rarer for putative denitrifiers with nirS, representing fewer than 4% of genomes in a recent survey—but a small number of surveyed bacteria do, interestingly, appear to harbor nirS without also harboring cNOR or qNOR (Graf et al., 2014; Heylen et al., 2007). To our knowledge, however, eNOR has not been included in such analyses of the genomic correlation between nitrite reductases and NORs. The phylogenetic evidence for diverse eNOR homologs suggests likely undocumented or underexplored diversity for divergent NORs. The diversity and function of cNOR and qNOR are fairly well‐established. However, divergent enzymes such as eNOR and sNOR are less extensively documented and may not be accurately distinguished from broader oxygen reductase superfamily members in genomic or metagenomic analyses.

Cytochrome c proteins function as electron transfer proteins in anaerobic respiration and are often fused to redox enzymes to allow electron passage (Bertini et al., 2006). It is not surprising, therefore, to find cytochrome c‐containing subunits in frame with nitrite reductase. NirS itself is cytochrome‐dependent (Bertini et al., 2006). However, the unusual addition of the upstream cytochrome domain (C1) may reflect additional redox requirements or capacity. It is also possible that the inclusion of this construct could be linked to the conspicuous absence of NOR enzymes in several MAGs containing a NirS ORF with the C1 fusion. NO reduction can be cytochrome‐dependent; the well‐studied cNORs contain a membrane‐anchored cytochrome c (Hemp & Gennis, 2008). Further, the C1 domain tree recovers ORFs in the Nitrospirae that contain C1 homologs and are annotated as NORs, with detectable similarity to Proteobacteria NOR subunits. It is therefore possible that the inclusion of a C1 domain in nir genes within genomes lacking eNOR reflects some generalized NOR‐like role in detoxification of the cytotoxic product of NirS. Additionally, while the presence of NirS suggests an active denitrification pathway, and the NirS domain tree reflects the homology between this domain and NirS from known denitrifying groups, the possibility remains that this group of Chloroflexi do not perform denitrification, and instead use this gene product for a different metabolic function, potentially enabled or constrained by the C1 domain. The genetic diversity observed within C1‐C2‐NirS gene neighborhoods—varying both from the genetic makeup of a canonical denitrification operon, and between different Chloroflexi MAGs—may reflect such functional flexibility. Shared or convergent functions could also be recovered among these diverse neighborhoods. The analyzed gene neighborhoods suggest some conserved functionality between different genomes from varying environmental sources and samples; for example, the presence of heme–copper oxidase subunits, molybdenum cofactor enzymes, and NADB Rossman superfamily proteins (Tables A1 and A2). However, without expanded homology analyses and experimental validation, it is impossible to infer whether apparent similarities or differences reflect biologically‐meaningful patterns of inheritance or function, or are simply artifactual.

A divergent or generalized role is also possible for the eNOR homologs. Models indicate that eNOR (unlike related NORs cNOR, qNOR, sNOR, and gNOR) has a proton channel, and therefore the capacity for proton pumping (Hemp & Gennis, 2008); therefore, this gene product may serve a key electrogenic role, whether reducing NO or alternative substrates. Experimental validation would be necessary to determine if the novel Chloroflexi‐associated NirS performs differently than canonical NirS in vivo, and if NirS and eNOR perform targeted denitrification or nonspecific detoxification or proton pumping. This study, therefore, suggests a promising direction for future investigations.

The divergent denitrification enzymes described above may or may not reflect different metabolic strategies in situ. But the identification of both a novel nirS ORF and an expanded diversity of eNOR enzymes suggests that the existing understanding of denitrification may underestimate the genetic diversity and ecological distribution of constituent enzymes. This may be especially true in deep subsurface biomes, such as those from which several Chloroflexi analyzed in this study were isolated. These systems have garnered increasing attention in recent years; extensive evidence supports the existence of dynamic, diverse microbial subsurface ecosystems with the metabolic potential to influence global biogeochemical cycles (Hug et al., 2013; Magnabosco et al., 2018; Momper & Jungbluth, 2017; Osburn et al., 2014, 2019). Chloroflexi are frequently cited as well‐represented members of deep sediment and aquifer systems, where they play key roles in carbon cycling dynamics (Hug et al., 2013; Kadnikov et al., 2020; Momper & Jungbluth, 2017; Momper & Kiel Reese, 2017). But Chloroflexi are known to also harbor diverse nitrogen metabolisms (Denef et al., 2016; Hemp et al., 2015; Spieck et al., 2020), and previous studies have linked subsurface Chloroflexi to denitrification pathway genes such as nitrous oxide reductase (nos) (Hug et al., 2016; Momper & Jungbluth, 2017; Sanford et al., 2012). The role of Chloroflexi in subsurface nitrogen cycling—as well as the scope of subsurface microbial nitrogen dynamics at large—requires further investigation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None required.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sarah L. Schwartz: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Validation (equal), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing‐Lead. Lily M. Momper: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (supporting); Investigation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Writing – original draft (supporting). L. Thiberio Rangel: Data curation (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (supporting). Cara Magnabosco: Data curation (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting). Jan P. Amend: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting). Gregory P. Fournier: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Supervision (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Ranjani Murali for advice on domain and residue identification and analysis. This study was supported by a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship to Sarah L. Schwartz, and Simons Collaboration on Origins of Life award #339603 to Gregory P. Fournier.

APPENDIX 1.

Figure A1.

C1‐C2‐NirS gene neighborhoods in Chloroflexi. A gene neighborhood showing the 20,000 base pair region adjacent to the putative nitrite reductase gene containing the C1‐C2‐NirS domain architecture. Neighborhoods are shown for homologs in Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 (GenBank accession OJX39483.1) and SURF MAG 71 (GenBank accession RJP52528.1). Expanded descriptions of gene names and functions are provided in Table A2

Figure A2.

Expanded C2 domain tree. Phylogenetic analysis of C2 domain homologs places the Chloroflexi within a diverse polyphyletic clade including Epsilonproteobacteria, Aquificae, Bacteroidetes, and Planctomycetes; this clade is sister to a broad radiation of Proteobacteria. Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray)

Figure A3.

Expanded NirS domain tree. Phylogenetic analysis of NirS domain homologs places the Chloroflexi within a polyphyletic clade dominated by Alpha‐, Beta‐, and Gammaproteobacteria. Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray)

Figure A4.

Subsampled C2 domain tree. Phylogenetic analysis of C2 domain homologs, subsampled to contain only taxa with both C2 and NirS domains in the nitrite reductase ORF, places the largest clade of Chloroflexi as sister to a polyphyletic group including a large group of Alpha‐, Beta‐, and Gammaproteobacteria. Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray). ORF, open reading frame

Figure A5.

Subsampled NirS domain tree. Phylogenetic analysis of NirS domain homologs, subsampled to contain only taxa with both C2 and NirS domains in the nitrite reductase ORF, places the largest clade of Chloroflexi as sister to a large radiation of Proteobacteria; these groups are nested within a diverse polyphyletic group. Support values for selected bipartitions are labeled (aLRT/bb). Support for other nodes is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray). ORF, open reading frame

Figure A6.

Various nitrite reductase architectures within Chloroflexi. Three different open reading frame types including a C1 cytochrome and a nitrite reductase domain appear in surveyed Chloroflexi. The most commonly seen gene features C1, C2, and cytochrome‐dependent nirS (a); however, C1 is also seen in ORFs with cupredoxin and copper‐dependent nitrite reductase (nirK) domains (b). A limited number of Chloroflexi genomes also contain ORFs placing C1, C2, and nirS together with an N‐terminal cupredoxin, plastocyanin (PetE), or similar copper‐containing domain (c). ORF, open reading frame

Figure A7.

eNOR subunit gene neighborhood. A gene neighborhood showing the 20,000 base pair region adjacent to eNOR subunits in SURF MAG 42. Sequence analysis of subunit I (NCBI protein accession RJP50323.1) reflects a conserved glutamine substitution characteristic of the eNOR subfamily. Both proposed subunits of eNOR—the heme‐copper cytochrome‐containing subunit I, and the cupredoxin‐containing subunit II—appear in the MAG. No other denitrification genes appear in the neighborhood. MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; SURF, Sanford Underground Research Facility

Figure A8.

Preliminary C1 domain tree. A preliminary phylogenetic tree for C1, including only sequences with E ≤ 10−10, contains very few overall taxa. The tree contains only members of the Chloroflexi, members of the Nitrospirae, and Nitrospina gracilis; the sampling depth does not recover an outgroup for these sister groups. Support for bipartitions is indicated with the following color scheme: Strong support with both values ≥90 (black); weak support with both values ≤50 (white); intermediate support with one or both values between 50 and 90 (gray); conflicting support, with one value ≤50 and the other ≥90 (gray)

APPENDIX 2.

Table A1.

Open reading frame descriptions for SURF MAG 42, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, and Anaerolinea thermolimosa NirS gene neighborhoods

| Displayed ORF name | Expanded description | Protein ID | Source MAG/organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xylose isomerase‐like | Sugar phosphate isomerase/epimerase, xylose isomerase‐like TIM barrel | RJP53741.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| LuxS | S‐ribosylhomocysteine lyase | RJP53742.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| EEVS | 2‐Epi‐5‐epi‐valiolone synthase/iron‐containing alcohol dehydrogenase | RJP53743.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| UbiG | Ubiquinone biosynthesis O‐methyltransferase/bifunctional 2‐polyprenol‐6‐hydroxyphenol | RJP53744.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| UbiA | ubiA family prenyltransferase | RJP53745.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| MhpC | Alpha/beta hydrolase/pimeloyl‐ACP methyl ester carboxylesterase | RJP53746.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| UDG‐like | Uracil‐DNA glycosylase | RJP53748.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| BaeS | HAMP domain‐containing protein/signal transduction kinase | RJP53750.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| N‐acetyltransferase | GNAT family N‐acetyltransferase | RJP53751.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| PrSA | Ribose‐phosphate pyrophosphokinase/phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase | RJP53766.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| PolX | DNA polymerase/3ʹ−5ʹ exonuclease | RJP53755.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| YdcZ | DMT family transporter | RJP53756.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| Putative PMT 2 superfamily | Dolichyl‐phosphate‐mannose‐protein mannosyltransferase | RJP53757.1 | SURF MAG 42 |

| Acetyl‐CoA dehydrogenase | Probable acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase | AAG03897.1 | PAO1 |

| nirN | Probable c‐type cytochrome | AAG03898.1 | PAO1 |

| SUMT | Probably uroporphyrin‐III c‐methyltransferase | AAG03899.1 | PAO1 |

| nirJ | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirJ | AAG03900.1 | PAO1 |

| nirH | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirH | AAG03901.1 | PAO1 |

| nirG | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirG/probable transcriptional regulator | AAG03902.1 | PAO1 |

| nirL | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirL | AAG03903.1 | PAO1 |

| nirD | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein nirD/probable transcriptional regulator | AAG03904.1 | PAO1 |

| nirF | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirF | AAG03905.1 | PAO1 |

| nirC | Probable c‐type cytochrome precursor | AAG03906.1 | PAO1 |

| nirM | Cytochrome c‐551 precursor | AAG03907.1 | PAO1 |

| nirQ | Regulatory protein NirQ | AAG03909.1 | PAO1 |

| Heme‐Cu oxidase III | Heme–copper oxidase, subunit III | AAG03911.1 | PAO1 |

| norC | Nitric‐oxide reductase subunit C | AAG03912.1 | PAO1 |

| norB | Nitric‐oxide reductase subunit B | AAG03913.1 | PAO1 |

| norD | Probable denitrification protein NorD | AAG03914.1 | PAO1 |

| Dnr | Transcriptional regulator DNR | AAG03916.1 | PAO1 |

| rsmY | Regulatory RNA RsmY/probable transcriptional regulator | AAG03917.1 | PAO1 |

| CynR | Provisional; DNA‐binding transcriptional regulator | AAG03917.1 | PAO1 |

| YiiM | Uncharacterized conserved protein/MOSC (molybdenum cofactor sulfurase C‐terminal)domain‐containing protein | AAG03918.1 | PAO1 |

| ArgD | Acetylornithine/succinyldiaminopimelate/putrescin e aminotransferase | AAG03919.1 | PAO1 |

| TrpB‐like | TrpB‐like pyridoxal‐phosphate dependent enzyme | GAP05449.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Gph | Phosphoglycolate phosphatase; haloacid dehalogenase family hydrolase | GAP05450.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| DR1245‐like | Uncharacterized, YbjN domain‐containing protein; possible type III secretion system chaperone protein | GAP05451.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| peptidase C39‐like | Peptidase C39‐like and TPR domain‐containing protein | GAP05452.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| DUF2568 | Hypothetical protein; YrdB family; DUF2568 | GAP05453.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| DUF4388 | Hypothetical protein; DUF4388 | GAP05454.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Srp102 | ATP/GTP‐binding protein; GTPase, signal recognition particle receptor subunit beta | GAP05455.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| MhpC | Predicted alpha/beta hydrolase; pimeloyl‐ACP methyl ester carboxylesterase | GAP05456.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| glmU | N‐acetylglucosamine‐1‐phosphate uridyltransferase; left‐handed parallel beta‐helix domain | GAP05458.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Cytochrome cd1 | Protein containing cytochrome D1 heme domain; nitrite reductase | GAP05460.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Cytidylate kinase‐like | Cytidylate kinase‐like family protein; NK superfamily | GAP05462.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Glycosyl hydrolase catalytic core | Glycosyl hydrolases superfamily | GAP05463.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Protoheme IX farnesyltransferase | Provisional protoheme IX farnesyltransferase; cytochrome oxidase assembly protein superfamily | GAP05464.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| SURF1 | SURF1 superfamily; similar to yeast cytochrome oxidase assembly protein SHY1 | GAP05465.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| SCO | SCO1/SenC/PrrC; synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase family | GAP05467.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Heme Cu oxidase III | Heme–copper oxidase subunit III | GAP05468.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| COX4 pro | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV family protein; prokaryotic cytochrome C oxidase subunit IV | GAP05469.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| Heme Cu oxidase I | Heme–copper oxidase subunit I | GAP05470.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

| CyoA | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit II; cytochrome c | GAP05471.1 | Anaerolinea thermolimosa |

Abbreviations: MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome; SURF, Sanford Underground Research Facility.

Table A2.

Open reading frame (ORF) descriptions for Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 and SURF MAG 71 NirS gene neighborhoods

| Displayed ORF name | Expanded description | Protein ID | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 Tnp | Hypothetical protein; Y1 Tnp superfamily, transposase IS200‐like | OJX39478.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| DEAD/DEAH | DEAD/DEAH box helicase; type I restriction endonuclease subunit R | OJX39479.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| PDDEXK‐like | Hypothetical protein; PDDEXK nuclease‐like superfamily | OJX39480.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| MobA | Hypothetical molybdenum cofactor guanylyltransferase | OJX39484.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| DUF2298 | Hypothetical protein; uncharacterized membrane protein DUF2298 superfamily; helix‐hairpin‐helix motif | OJX39485.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| PMT2/PA14 | Hypothetical protein; PA14 domain; Dolichyl‐phosphate‐mannose‐protein mannosyltransferase superfamily | OJX39484.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| NADB Rossmann | Hypothetical protein; NADB Rossmann superfamily; Rossmann‐fold NAD(P)(+)‐binding proteins | OJX39487.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| PMT2 | Hypothetical protein; Dolichyl‐phosphate‐mannose‐protein mannosyltransferase | OJX39488.1 | Chloroflexi bacterium 44‐23 |

| MFS MOT1 | Hypothetical protein; putative sulfate/molybdate transporter, MFS superfamily | RJP52521.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| CopZ | Copper chaperone CopZ; heavy‐metal‐associated domain‐containing protein | RJP52522.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| DsbD 2 | Hypothetical protein; DsbD 2 cytochrome c biogenesis protein transmembrane region; cupredoxin superfamily‐containing protein | RJP52523.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| P‐type ATPase | Heavy metal translocating P‐type ATPase, Cu‐like | RJP52525.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| HMA | Heavy metal transporter, HMA superfamily | RJP52526.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| CsoR‐like | Metal‐sensitive transcriptional regulator; TthCsoR‐like DUF156 | RJP52527.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| S2P‐M50‐like | Site‐2 protease family protein; zinc metalloproteases | RJP52530.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| GalE | UDP‐glucose 4‐epimerase; NADB Rossmann superfamily | RJP52531.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

| Fes | Hypothetical protein; Fes superfamily; Enterochelin esterase or related enzyme | RJP52532.1 | SURF MAG 71 |

Abbreviations: MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome; SURF, Sanford Underground Research Facility.

Table A3.

Domain families in ORFs with C1 domain homolog but no NirS domain homolog

| Domain name | Brief description | Accession(s) |

|---|---|---|

| CyoA | Cytochrome/quinol oxidase | RME74748.1 |

| COX IV | Prokaryotic cytochrome c subunit IV | PKB63614.1; PIQ26724.1 |

| tynA | Primary‐amine oxidase | WP_095041976.1 |

| CxxCH_TIGR02603 | Putative heme‐binding domain | WP_095041976.1; OUC09162.1; OGW07928.1; OGP31126.1; OGV95443.1; OGP47454.1; OGP11994.1; OG149337.1; OYT21294.1; OLD38719.1; OLB21185.1 |

| Cupredoxin | N/A | UBA5757_DIDP01000039.1_40 |

| Caa3_CtaG | Cytochrome c oxidase caa3 assembly factor | PYQ29527.1 |

| PRK10856 | Cytoskeleton protein RodZ | OQY877.1 |

| EnvC | Septal ring factor, activator of murein hydrolases | RMF78192.1 |

| PRK03735 | Provisional cytochrome b6 | RME88945.1 |

| DMSOR_beta‐like | DMSO reductase beta subunit | RME88945.1 |

| FlpD | Methyl‐viologen‐reducing | RME88945.1 |

| hydrogenase, beta subunit | ||

| TTQ_mauG | tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis enzyme MauG | RIK95915.1 |

| Heme_Cu_Oxidase_I | Heme‐copper oxidase subunit I | WP_073101466.1 |

| PRK14486 | Putative bifunctional cbb3‐type cytochrome c oxidase subunit II | OYW96265.1 |

| YccC | Uncharacterized membrane protein | OLB04623.1; OAI45763.1; WP_080880425.1; KXJ99429.1 |

| FTR1 | Iron permease | WP_053380952.1 |

| EcfT | T component of ECF‐type transporters | WP_090902251.1 |

| ArsB_NhaD_permease | Anion permease | OYT18856.1; WP_090747891.1 |

Abbreviation: ORF, open reading frame.

Table A4.

Heme–copper superfamily active site (modified from Hemp & Gennis, 2008)

| Enzyme | Active‐site residue | Predicted no. of proton channels | Present in |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen reductase | Y | 0–2 | All domains; varies by enzyme subfamily |

| cNOR | E | 0 | Proteobacteria (Shiro, 2012; Hendriks, 2000) |

| qNOR | E | 0 | Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Archaea (Shiro, 2012; Hemp & Gennis, 2008; Heylen et al., 2007; Hendriks et al, 2000) |

| sNOR | N | 0 | Betaproteobacteria, Silicibacter, Deinococcus, Geobacillus (Stein et al., 2007) |

| eNOR | Q | 1 | Archaea (Hemp & Gennis, 2008, this study), Chloroflexi (Ward, McGlynn et al., 2018 this study), Proteobacteria (this study) |

| gNOR | D | 0 | Sulfurimonas, Sulfurovum, Persephonella (Sievert et al., 2008) |

| CuANor | N | 1 | Bacillus (Al‐Attar & De Vries, 2015; Suharti et al., 2001) |

Abbreviations: cNOR, cytochrome‐type nitric oxide reductase; qNOR, quinol‐dependent nitric oxide reductases.

Table A5.

MAG source data

| Genome | BioProject | BioSample | MAG name | MAG/hit db filename | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499021 | SURF MAG 27 | NA1 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 2 | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499024 | SURF MAG 30 | NA2 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017 |

| 3 | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499034 | SURF MAG 40 | NA3 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 4a | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499036 | SURF MAG 42 | NA4 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 5 | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499037 | SURF MAG 43 | NA5 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 6 | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499065 | SURF MAG 71 | NA6 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 7 | PRJNA355136 | SAMN08499062 | SURF MAG 68 | NA7 | Momper, Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 8 | PRJNA269163 | SAMN06226378 | JdFR‐61 | JdFR61 | Jungbluth et al. (2017) |

| 9 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA8 | – |

| 10 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA9 | – |

| 11 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA10 | – |

| 12 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA11 | – |

| 13 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA12 | – |

| 14 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA13 | – |

| 15 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA14 | – |

| 16 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA15 | – |

| 17 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA16 | – |

| 18 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA17 | – |

| 19 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA18 | – |

| 20 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA19 | – |

| 21 | PRJNA681409/PRJNA680468 | pending release | – | SA20 | – |

Abbreviations: ORF, open reading frame; MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome.

SURF MAG 42 is the source genome for nirS ORF.

Table A6.

MAG identifying data for sequences selected from Parks et al. (2017)

| MAG no. | Organism name | Isolate ID | WGS ID | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA1024 | DCER00000000 | |||||

| 2 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA2178 | DCVW00000000 | |||||

| 3 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA2274 | DDWY00000000 | |||||

| 4 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA6073 | DIXT00000000 | |||||

| 5 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA7644 | DLIK00000000 | |||||

| 6 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA1429 | DCTX00000000 | |||||

| 7 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2181 | DCVT00000000 | |||||

| 8 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2200 | DCVA00000000 | |||||

| 9 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2317 | DDVH00000000 | |||||

| 10 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2323 | DDVB00000000 | |||||

| 11 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2356 | DDTU00000000 | |||||

| 12 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2395 | DDSH00000000 | |||||

| 13 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2414 | DDRO00000000 | |||||

| 14 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA2796 | DEHQ00000000 | |||||

| 15 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA6092 | DIXA00000000 | |||||

| 16 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA6663 | DKKP00000000 | |||||

| 17 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA6665 | DKKN00000000 | |||||

| 18 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA7227 | DKTP00000000 | |||||

| 19 | Chloroflexaceae | bacterium | UBA1466 | DCSM00000000 | |||||

| 20 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA2235 | DDYL00000000 | |||||

| 21 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA5177 | DHWR00000000 | |||||

| 22 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA5183 | DHWL00000000 | |||||

| 23 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA6042 | DIYY00000000 | |||||

| 24 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA6077 | DIXP00000000 | |||||

| 25 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA6265 | DJVD00000000 | |||||

| 26 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA6622 | DJHK00000000 | |||||

| 27 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA1127 | DCAS00000000 | |||||

| 28 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA1151 | DBZV00000000 | |||||

| 29 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA1222 | DBXC00000000 | |||||

| 30 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2141 | DCXH00000000 | |||||

| 31 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2158 | DCWQ00000000 | |||||

| 32 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2160 | DCWO00000000 | |||||

| 33 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2243 | DDYD00000000 | |||||

| 34 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2247 | DDXZ00000000 | |||||

| 35 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2588 | DDKW00000000 | |||||

| 36 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2768 | DEIS00000000 | |||||

| 37 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2962 | DEBG00000000 | |||||

| 38 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA2979 | DEAP00000000 | |||||

| 39 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA6234 | DJWI00000000 | |||||

| 40 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA6803 | DKFF00000000 | |||||

| 41 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA6926 | DKAM00000000 | |||||

| 42 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA6951 | DJZN00000000 | |||||

| 43 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA6956 | DJZI00000000 | |||||

| 44 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA7833 | DLTP00000000 | |||||

| 45 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA7894 | DLRG00000000 | |||||

| 46 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA826 | DBHO00000000 | |||||

| 47 | bacterium | UBP15 | UBA6099 | DIWT00000000 | |||||

| 48 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA4775 | DHHJ00000000 | |||||

| 49 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA4784 | DHHA00000000 | |||||

| 50 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA4841 | DHEV00000000 | |||||

| 51 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA4890 | DHCY00000000 | |||||

| 52 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA4929 | DHBL00000000 | |||||

| 53 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5199 | DHVV00000000 | |||||

| 54 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5224 | DHUW00000000 | |||||

| 55 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5229 | DHUR00000000 | |||||

| 56 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5241 | DHUF00000000 | |||||

| 57 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5243 | DHUD00000000 | |||||

| 58 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5311 | DHRN00000000 | |||||

| 59 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5344 | DHQG00000000 | |||||

| 60 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5355 | DHPV00000000 | |||||

| 61 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5404 | DHNY00000000 | |||||

| 62 | Anaerolineaceae | bacterium | UBA5823 | DICP00000000 | |||||

| 63 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA4142 | DFWE00000000 | |||||

| 64 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA4826 | DHFK00000000 | |||||

| 65 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA5215 | DHVF00000000 | |||||

| 66 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA5796 | DIDQ00000000 | |||||

| 67 | Anaerolineales | bacterium | UBA5797 | DIDP00000000 | |||||

| 68 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA4669 | DHLL00000000 | |||||

| 69 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA4730 | DHJC00000000 | |||||

| 70 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA4733 | DHIZ00000000 | |||||

| 71 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA4735 | DHIX00000000 | |||||

| 72 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA4736 | DHIW00000000 | |||||

| 73 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA5189 | DHWF00000000 | |||||

| 74 | Chloroflexi | bacterium | UBA6019 | DIZV00000000 | |||||

| 75 | Dehalococcoides | mccartyi | UBA5818 | DICU00000000 | |||||

| 76 | Dehalococcoides | mccartyi | UBA5554 | DIMY00000000 | |||||

| 77 | Dehalococcoides | mccartyi | UBA5545 | DINH00000000 | |||||

| 78 | Dehalococcoides | mccartyi | UBA5853 | DJGF00000000 | |||||

| 79 | Dehalococcoides | mccartyi | UBA5846 | DJGM00000000 | |||||

| 80 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA3088 | DFBE00000000 | |||||

| 81 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA4086 | DFYI00000000 | |||||

| 82 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA4087 | DFYH00000000 | |||||

| 83 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA4462 | DGOQ00000000 | |||||

| 84 | Dehalococcoidia | bacterium | UBA5760 | DIFA00000000 | |||||

| 85 | Leptolinea | sp | UBA4782 | DHHC00000000 | |||||

| 86 | Nitrospinaceae | bacterium | UBA3496 | DFQF00000000 |

Abbreviation: MAG, metagenome‐assembled genome.

Table A7.

Model data by domain/gene tree

| Gene/ORF | Figure no. | Substitution model (selected by IQ Tree MF) |

|---|---|---|

| C1, no outgroup | A8 | WAG+F+R4 |

| C1, with outgroup | 5 | WAG+F+R6 |

| C2 | 4, A2 | LG+R7 |

| NirS | 4, A3 | LG+F+R7 |

| eNOR | 6 | LG+F+R6 |

Abbreviation: ORF, open reading frame.

Schwartz, S. L. , Momper, L. , Rangel, L. T. , Magnabosco, C. , Amend, J. P. , & Fournier, G. P. (2022). Novel nitrite reductase domain structure suggests a chimeric denitrification repertoire in the phylum Chloroflexi. MicrobiologyOpen, 11, e1258. 10.1002/mbo3.1258

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14515554.v2. Scripts used to automate analyses are archived in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5745924.

REFERENCES

- Agarwala, R. , Barrett, T. , Beck, J. , Benson, D. A. , Bollin, C. , Bolton, E. , Bourexis, D. , Brister, J. R. , Bryant, S. H. , Canese, K. , Cavanaugh, M. , Charowhas, C. , Clark, K. , Dondoshansky, I. , Feolo, M. , Fitzpatrick, L. , Funk, K. , Geer, L. Y. , Gorelenkov, V. , … Zbicz, K. (2018). Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D8–D13. 10.1093/nar/gkx1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Attar, S. , & de Vries, S. (2015). An electrogenic nitric oxide reductase. FEBS Letters, 589(16), 2050–2057. 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alneberg, J. , Bjarnason, B. S. , de Bruijn, I. , Schirmer, M. , Quick, J. , Ijaz, U. Z. , Lahti, L. , Loman, N. J. , Andersson, A. F. , & Quince, C. (2014). Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nature Methods, 11, 1144–1146. 10.1038/nmeth.3103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert, P. , Biasini, M. , & Schwede, T. (2011). Toward the estimation of the absolute quality of individual protein structure models. Bioinformatics, 27(3), 343–350. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, H. M. , Westbrook, J. , Feng, Z. , Gilliland, G. , Bhat, T. N. , Weissig, H. , Shindyalov, I. N. , & Bourne, P. E. (2000). The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research, 28, 235–242. 10.1093/nar/28.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini, I. , Cavallaro, G. , & Rosato, A. (2006). Cytochrome c: Occurrence and functions. Chemical Reviews, 106, 90–115. 10.1021/cr050241v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert, S. , Waterhouse, A. , de Beer, T. A. , Tauriello, G. , Studer, G. , Bordoli, L. , & Schwede, T. (2017). The SWISS‐MODEL Repository‐new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D313–D319. 10.1093/nar/gkw1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg, M. R. A. , & Ädelroth, P. (2018). Mechanisms for enzymatic reduction of nitric oxide to nitrous oxide—a comparison between nitric oxide reductase and cytochrome c oxidase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Bioenergetics, 1859(11), 1223–1234. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.09.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braker, G. , Zhou, J. , Wu, L. , Devol, A. H. , & Tiedje, J. M. (2000). Nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) as functional markers to investigate diversity of denitrifying bacteria in pacific northwest marine sediment communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 66(5), 2096–2104. 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2096-2104.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterbach‐Bahl, K. , & Dannenmann, M. (2011). Denitrification and associated soil N2O emissions due to agricultural activities in a changing climate. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 3(5), 389–395. 10.1016/j.cosust.2011.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C. , Coulouris, G. , Avagyan, V. , Ma, N. , Papadopoulos, J. , Bealer, K. , & Madden, T. L. (2009). BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 403. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. H. , O'Donoghue, P. , Campbell, A. G. , Schwientek, P. , Sczyrba, A. , Woyke, T. , Söll, D. , & Podar, M. (2013). UGA is an additional glycine codon in uncultured SR1 bacteria from the human microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110, 5540–5545. 10.1073/pnas.1303090110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, D. E. , Glazer, A. N. , & Falkowski, P. G. (2010). The evolution and future of earth's nitrogen cycle. Science, 330(6001), 192–196. 10.1126/science.1186120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creevey, C. J. , Doerks, T. , Fitzpatrick, D. A. , Raes, J. , & Bork, P. (2011). Universally distributed single‐copy genes indicate a constant rate of horizontal transfer. PLoS One, 6(8), e22099. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decleyre, H. , Heylen, K. , Tytgat, B. , & Willems, A. (2016). Erratum to: Highly diverse nirK genes comprise two major clades that harbour ammonium‐producing denitrifiers. BMC Genomics, 17(1), 12864. 10.1186/s12864-016-2812-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef, V. J. , Mueller, R. S. , Chiang, E. , Liebig, J. R. , & Vanderploeg, H. A. (2016). Chloroflexi CL500‐11 populations that predominate deep‐lake hypolimnion bacterioplankton rely on nitrogen‐rich dissolved organic matter metabolism and C1 compound oxidation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 82(5), 1423–1432. 10.1128/AEM.03014-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, C. L. , Rusch, D. B. , Yooseph, S. , Lombardo, M. J. , Richter, R. A. , Valas, R. , Novotny, M. , Yee‐Greenbaum, J. , Selengut, J. D. , Haft, D. H. , Halpern, A. L. , Lasken, R. S. , Nealson, K. , Friedman, R. , & Venter, J. C. (2012). Genomic insights to SAR86, an abundant and uncultivated marine bacterial lineage. ISME Journal, 6(6), 1186–1199. 10.1038/ismej.2011.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, A. M. , Helmick, R. A. , & Gardner, P. R. (2002). Flavorubredoxin, an inducible catalyst for nitric oxide reduction and detoxification in Escherichia coli . Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(10), 8172–8177. 10.1074/jbc.M110471200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, D. R. H. , Jones, C. M. , & Hallin, S. (2014). Intergenomic comparisons highlight modularity of the denitrification pathway and underpin the importance of community structure for N2O emissions. PLoS One, 9(12), 1–20. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, K. J. , Crécy‐Lagard, De, V. , & Zallot, R. (2018). Gene graphics: A genomic neighborhood data visualization web application. Bioinformatics, 34(8), 1406–1408. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard, A. W. , Warr, O. , Borgonie, G. , Linage‐Alvarez, B. , Kuloyo, O. , Magnabosco, C. , Lau, M. , Erasmus, M. , Cason, E. D. , van Heerden, E. , Kieft, T. L. , Mabry, J. , Onstott, T. C. , Sherwood Lollar, B. , & Ballentine, C. J. (2017). Origins and ages of fracture fluids in the South African Crust [Abstract]. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting, H11A–H11153.

- Hemp, J. , Ward, L. M. , Pace, L. A. , & Fischer, W. W. (2015). Draft genome sequence of Ardenticatena maritima 110S, a thermophilic nitrate‐ and iron‐reducing member of the Chloroflexi Class Ardenticatenia. Genome Announcements, 3(6), 2920. 10.1128/genomeA.01347-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemp, J. , & Gennis, R. B. (2008). Diversity of the heme‐copper superfamily in archaea: Insights from genomics and structural modeling. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation, 45, 1–31. 10.1007/400_2007_046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, J. , Oubrie, A. , Castresana, J. , Urbani, A. , Gemeinhardt, S. , & Saraste, M. (2000). Nitric oxide reductases in bacteria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Bioenergetics, 1459(2–3), 266–273. 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00161-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heylen, K. , Vanparys, B. , Gevers, D. , Wittebolle, L. , Boon, N. , & De Vos, P. (2007). Nitric oxide reductase (norB) gene sequence analysis reveals discrepancies with nitrite reductase (nir) gene phylogeny in cultivated denitrifiers. Environmental Microbiology, 9(4), 1072–1077. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, D. T. , Chernomor, O. , von Haeseler, A. , Minh, B. Q. , & Vinh, L. S. (2018). UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 518–522. 10.1093/molbev/msx281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug, L. A. , Castelle, C. J. , Wrighton, K. C. , Thomas, B. C. , Sharon, I. , Frischkorn, K. R. , Williams, K. H. , Tringe, S. G. , & Banfield, J. F. (2013). Community genomic analyses constrain the distribution of metabolic traits across the Chloroflexi phylum and indicate roles in sediment carbon cycling. Microbiome, 1(1), 1–17. 10.1186/2049-2618-1-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug, L. A. , Thomas, B. C. , Sharon, I. , Brown, C. T. , Sharma, R. , Hettich, R. L. , Wilkins, M. J. , Williams, K. H. , Singh, A. , & Banfield, J. F. (2016). Critical biogeochemical functions in the subsurface are associated with bacteria from new phyla and little studied lineages. Environmental Microbiology, 18(1), 159–173. 10.1111/1462-2920.12930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntemann, M. , Ivanova, N. N. , Mavromatis, K. , Tripp, H. J. , Paez‐Espino, D. , Palaniappan, K. , Szeto, E. , Pillay, M. , Chen, I. M. , Pati, A. , Nielsen, T. , Markowitz, V. M. , & Kyrpides, N. C. (2015). The standard operating procedure of the DOE‐JGI Microbial Genome Annotation Pipeline (MGAP v.4). Standards in Genomic Sciences, 11, 27. 10.1186/s40793-015-0077-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. M. , Stres, B. , Rosenquist, M. , & Hallin, S. (2008). Phylogenetic analysis of nitrite, nitric oxide, and nitrous oxide respiratory enzymes reveal a complex evolutionary history for denitrification. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 25(9), 1955–1966. 10.1093/molbev/msn146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungbluth, S. P. , Amend, J. P. , & Rappé, M. S. (2017). Corrigendum: Metagenome sequencing and 98 microbial genomes from Juan de Fuca Ridge flank subsurface fluids. Scientific Data, 4, 170080. 10.1038/sdata.2017.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadnikov, V. V. , Mardanov, A. V. , Beletsky, A. V. , Karnachuk, O. V. , & Ravin, N. V. (2020). Microbial life in the deep subsurface aquifer illuminated by metagenomics. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 1–15. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.572252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S. , Minh, B. Q. , Wong, T. , von Haeseler, A. , & Jermiin, L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods, 14, 587–589. 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]