Abstract

Chemical sensors based on mesoporous silica nanotubes (MSNTs) for the quick detection of Fe(III) ions have been developed. The nanotubes’ surface was chemically modified with phenolic groups by reaction of the silanol from the silica nanotubes surface with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane followed by reaction with 3-formylsalicylic acid (3-fsa) or 5-formylsalicylic acid (5-fsa) to produce the novel nanosensors. The color of the resultant 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors changes once meeting a very low concentration of Fe(III) ions. Color changes can be seen by the naked eye and tracked with a smartphone or fluorometric or spectrophotometric techniques. Many experimental studies have been conducted to find out the optimum conditions for colorimetric and fluorometric determining of the Fe(III) ions by the two novel sensors. The response time, for the two sensors, that is necessary to achieve a steady spectroscopic signal was less than 15 s. The suggested methods were validated in terms of the lowest limit of detection (LOD), the lowest limit of quantification (LOQ), linearity, and precision according to International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines. The lowest limit of detection that was obtained from the spectrophotometric technique was 18 ppb for Fe(III) ions. In addition, the results showed that the two sensors can be used eight times after recycling using 0.1 M EDTA as eluent with high efficiency (90%). As a result, the two sensors were successfully used to determine Fe(III) in a variety of real samples (tap water, river water, seawater, and pharmaceutical samples) with great sensitivity and selectivity.

Introduction

Iron is the fourth most prevalent element in the earth’s crust, and it is widely spread throughout the ecosystem. It is most common in oxidation states II and III. Fe(II) and Fe(III) have different bioavailability and metabolism. The Fe(III) ion is a critical metal center in catalysis and biology, as well as in biotechnology.1 An adequate amount of Fe(III) intake prevents certain illnesses, for example, liver and pancreatic uptake.2 Once the concentration of the Fe(III) ions surpasses the capability of the organisms, they become toxic, although they can be detoxified via Strophariaceae.2 As a result, Fe(III) detection or sensing is critical for biological and environmental issues.3

Many traditional analytical techniques were used in Fe determination, e.g., ICP-AES method,4 ion-selective membrane potentiometric sensor,5 flame atomic absorption spectrometry,6 and the combination of ultraviolet detection and capillary electrophoresis method,7 Also, UV–vis detection and microcolumn ion chromatography,8 as well as atomic absorption spectrometry after solid-phase extraction,9 were also reported. When compared to alternative techniques like luminescence spectroscopy, these procedures are costly, are time-consuming, and need pretreatment or preconcentration.10,11

It is worth mentioning that most power plants include a basic laboratory with low-cost devices like spectrophotometers. While spectrophotometric techniques are recognized for being uncomplicated, affordable, and quick methods of analysis, they typically require the selectivity and sensitivity needed for low-concentration analyte detection. However, combining them with a microextraction method with a high preconcentration factor can improve their sensitivity. Multivariate calibration approaches, for example, partial least squares (PLS) regression, principal component regression (PCR),12 and artificial neural networks,13 can help increase selectivity.

In the solid state, formylsalicylic acid derivatives have been demonstrated to form stable metal complexes with various metal ions.14 It was also found that the salicylic acid derivatives were more sensitive toward Fe(III) ions than other organic compounds containing the phenolic group.15 In pure and mixed solvents, Orabi studied the absorption spectra of 3-formylsalicylic acid and 5-formylsalicylic acid.16 He also used spectrophotometry to investigate the complex formation between the two formylsalicylic acids with the Fe(III) ions in a solution. The stoichiometric ratios of the two systems were calculated using the slope-ratio, continuous variation, and mole-ratio approaches, all of which revealed a 1:1 type of complex.16 The 3-fsa and 5-fsa compounds have been immobilized on the surface of silica gel containing the amino group. The extraction of Fe(III) from the resultant materials was examined, and the exchange capacity was found to be 0.95–0.96 mmol g–1.17 However, there is no one using the immobilized formylsalicylic acids in the determination of Fe(III) using spectrophotometric and fluorometric methods.

In this work, a facile and highly efficient strategy to prepare smart nanosensors based on the mesoporous silica nanotubes has been done. First, the mesoporous silica nanotubes were prepared by using nickel-hydrazine complex nanorods as a hard template. Second, the MSNTs were immobilized by 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane. Third, the formyl salicylic acids were bonded chemically with 3-APTES@MSNTs. Fourth, the formed 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were found to have high sensitivity and selectivity for the determination of Fe(III). Fifth, the determination process can be tracked by the naked eye, a smartphone, or fluorometric and UV–vis spectrophotometric techniques. Sixth, the smart sensors were used for determining the Fe(III) in tap water, river water, seawater, and pharmaceutical samples.

Experimental Section

Preparation of the 3-Formylsalicylic Acid (3-fsa) and 5-Formylsalicylic Acid (5-fsa)

The 3-fsa and 5-fsa were synthesized according to the literature.18 The purity was analyzed by CHNS elemental analyses—CH (3-fsa): C, 57.86; H, 3.66, and CH (5-fsa): C, 57.89; H, 3.61—as they are consistent with the C8H6O4 molecular formula of both (molecular wt. 166.13), which required C, 57.84; H, 3.64%. The 3-fsa and 5-fsa were analyzed by using 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. The data of the 3-fsa were as follows: 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.30 (t, H, Ben-H), 7.95 (d, H, Ben-H), 8.38 (d, H, Ben-H), 10.19 (s, H, Ben-CHO), 12.04 (s, H, Ben-COOH), 12.15 (s, H, Ben-OH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 188.0 (CHO), 171.8 (COOH), 162.9 (Ben, OH), 137.8 (Ben, CHO), 137.5 (Ben, CH), 136.5 (Ben, CH), 121.7 (Ben, CH), 113.8 (Ben, COOH). The data of the (5-fsa) were as follows: 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.21 (d, H, Ben-H), 7.84 (s, H, Ben-H), 8.05 (d, H, Ben-H), 9.88 (s, H, Ben-CHO), 12.04 (s, H, Ben-COOH), 15.2 (s, H, Ben-OH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 191.0 (CHO), 171.8 (COOH), 168.0 (Ben, OH), 129.4 (Ben, CHO), 137.9 (Ben, CH), 131.6 (Ben, CH), 118.4 (Ben, CH), 129.4 (Ben, COOH).

Synthesis of MSNT-Bound Amines (3-APTES@MSNTs)

Into a round-bottomed flask, 1.0 g of the grinded MSNTs was transferred. Then, 50 mL of anhydrous toluene (Sigma-Aldrich) was added followed by 3 mL of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (3-APTES) (Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom) and refluxed overnight. The 3-APTES@MSNTs were filtered off; washed with ethanol, diethyl ether, and toluene; and then dried for 6 h at 60 °C.

Synthesis of MSNT-Bound Formylsalicylic Acid Sensors (3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors)

For the synthesis of MSNT-bound formylsalicylic acid sensors (3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors), 1.0 g of grinded 3-APTES@MSNTs was added to the solution after 0.3 g of 3- or 5-formylsalicylic acid was dissolved in 50 mL of anhydrous toluene by heating. The mixture solution was reflexed for 6 h, left to cool, and filtered off. The precipitate was washed with diethyl ether, ethanol, and toluene and dried at 80 °C for 5 h under a vacuum. Scheme 1 shows the synthesis approach to the MSNT-immobilized formylsalicylic acid phases.

Scheme 1. The Synthetic Route to the MSNT-Immobilized Formylsalicylic Acid and Formation of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors.

Determination of the Fe(III) Ions in the Real Samples

The suggested method was applied to determine the Fe(III) ions in water samples collected from different sources, as shown in Table 5. One drop was added from the 0.1 M HCl solution to 50 mL of the water samples after they were filtered using a 0.45 μm Super filter preceding the test. Then, they were spiked with different Fe(III) ions concentrations (25, 50, and 75 ppb). Also, the planned method was applied to determine the Fe(III) ions in the pharmaceutical sample (dietary supplement). Ten irolamin capsules were added to 50 mL of HNO3 50% (v/v) after removal of their caps. The solution was heated till it was nearly dry and transported to a 100 mL volumetric flask. The solution was made up to the mark, and then 1 mL was taken and diluted with the appropriate buffer in different 10 mL volumetric flasks. All the results of the determination by the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were compared with results obtained using the ICP-OES technique.

Table 5. The Fluorometric Method Results for the Determination of the Fe(III) Ions in the Tap Water, River Water, Sea Water, and Pharmaceutical Samples Using the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors.

| founda (ppb) | founda (ppb) |

SDa |

RSD% |

recovery

(%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | added (ppb) | ICP-OES | 3-fsa-MSNT sensor | 5-fsa-MSNT sensor | 3-fsa-MSNT sensor | 5-fsa-MSNT sensor | 3-fsa-MSNT sensor | 5-fsa-MSNT sensor | 3-fsa-MSNT sensor | 5-fsa-MSNT sensor | sample source |

| tap water | 25 | 31 | 32 | 31 | 0.0219 | 0.0096 | 3.69 | 5.11 | 116 | 100 | Suez (Egypt) |

| 50 | 58 | 57 | 57 | 0.0215 | 0.0094 | 3.73 | 6.61 | 87 | 100 | ||

| 75 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 0.0212 | 0.0092 | 3.77 | 9.32 | 100 | 114 | ||

| river water | 25 | 67 | 66 | 68 | 0.0214 | 0.0093 | 3.74 | 7.44 | 98 | 102 | Ismailia Canal (Egypt) |

| 50 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 0.0211 | 0.0091 | 3.78 | 10.77 | 103 | 105 | ||

| 75 | 118 | 117 | 117 | 0.0208 | 0.0090 | 3.83 | 15.78 | 98 | 98 | ||

| sea water | 25 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 0.0219 | 0.0096 | 3.69 | 5.11 | 100 | 116 | Red Sea (Egypt) |

| 50 | 56 | 55 | 57 | 0.0215 | 0.0094 | 3.72 | 6.49 | 83 | 116 | ||

| 75 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 0.0212 | 0.0092 | 3.77 | 9.17 | 86 | 100 | ||

| dietary supplement | 25 | 27 | 27 | 0.0219 | 0.0096 | 3.68 | 4.90 | irolamin capsules | |||

Average of three replicate determinations.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were collected by using a Bruker Alpha(II) spectrometer (equipped with a diamond ATR crystal) and given in Figure S1. The OH bending vibration at 788–809 cm–1 and the Si–O–Si asymmetric stretching vibration at 1067–1037 cm–1 appeared in the four spectra.19 After the immobilization of the 3-APTES, a new band at 2941–2929 cm–1 that signified C–H stretching vibration appeared in the spectrum of 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT samples.20 The presence of a new band at 1558–1565 cm–1 consistent with the bond (C=N) in the spectrum of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors shows that the formylsalicylic acids were covalently bonded to the 3-APTES@MSNTs through Schiff base bond formation. In addition, the NH2 bands that appeared in 3-APTES@MSNTs at 3166 and 3240 were absent in the IR spectra of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors. The characteristic (C=O) band at 1639–1612 cm–1 in the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors was additional proof of the occurrence of a carbonyl group in their structures. The phenolic (OH) band of the formylsalicylic acids appeared at 3377–3389 in the spectra of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors.

Because of its unique surface functioning, biocompatibility, and hydrophilic design, the silica nanotube has gotten a lot of attention. It was previously synthesized with carefully regulated dimensions.21 In this paper, to synthesize mesoporous silica nanotubes and increase their surface area, the CATAB as a surfactant was used in its preparation. The structure of MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors was verified by the XRD analysis. The low-angle XRD patterns of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were carried out using an X PERT PRO PANalytical (made in Netherlands). They displayed a shoulder peak at 2θ ≈ 1.55° confirming the presence of ordered mesopores in the wall of the silica nanotubes, as shown in Figure S2A. The wide-angle XRD of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT samples displayed a typical broad peak over the range 15–37°, as shown in Figure S2B. This can be attributed to the fact that the nanotubes’ wall was found to be made of amorphous silica. It appears that the MSNTs’ structure morphology was kept after the modification by 3-APTES and also after the condensation of the formylsalicylic acids with 3-APTES@MSNTs.

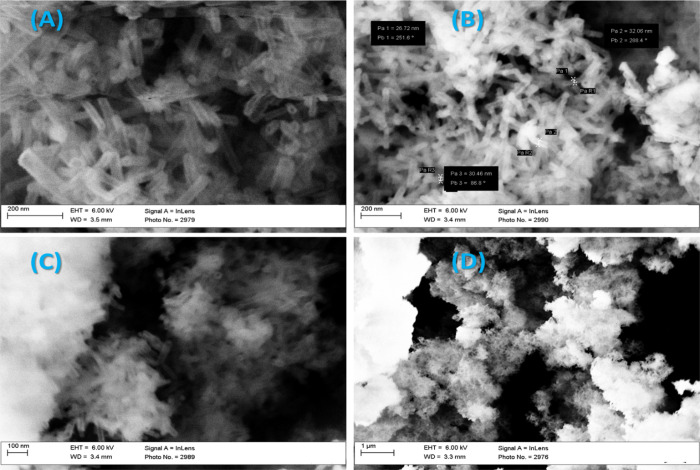

Figures 1 and 2 show the morphologies of the MSNTs, 3-APTES@MSNTs, 3-fsa-MSNTs, and 5-fsa-MSNTs by the FE-SEM (Hitachi S-4300) and HR-TEM (Tecnai G20, made in Netherlands). They speculated that the substance comprises nanotubes with a diameter of 32 nm. In addition, the MSNTs’ structure morphology was kept after the modification by 3-APTES and also after the reaction of the formylsalicylic acids with 3-APTES@MSNTs.

Figure 1.

FE-SEM images of the (A) MSNT, (B) 3-APTES@MSNT, (C) 3-fsa-MSNT, and (D) 5-fsa-MSNT sensors.

Figure 2.

HR-TEM images of the (A) MSNT, (B) 3-APTES@MSNT, (C) 3-fsa-MSNT, and (D) 5-fsa-MSNT sensors.

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm measurements of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were performed at 77 K using a CHEMBET NOVA 3000-Quanta chrome instrument with a pore size and surface area analyzer. As shown from Figure 3A, all samples showed a type IV isotherm, which displays pore condensation with hysteresis loop at p/po = 0.4–1.0 relative pressure. In addition, the (BET) surface area of the MSNTs was 825.17 m2 g–1, which is higher than the surface area of the 3-APTES@MSNTs (660.13 m2 g–1). The surface areas of the two sensors were slightly decreased than the surface area of the 3-APTES@MSNTs (618.87 and 602.75 m2 g–1 for the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively). Consequently, the pore volume of the MSNTs was 0.666 cm3/g, while the pore volumes of the 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were 0.532, 0.504, and 0.507, respectively. The decrease in surface areas and pore volumes of the 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors can be attributed to the attaching of 3-APTES, 3-fsa, and 5-fsa molecules outside and inside the wall of the nanotube.

Figure 3.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the samples at 77 K (A) and pore size distribution curves (B) of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors.

UV–Vis Studies on the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors

To find out the ideal conditions for colorimetric and fluorometric determining of the Fe(III) ions by the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, many experimental studies have been conducted.22 To determine the optimum pH, about 30 mg of each sensor was added to solutions containing 0.1 ppm Fe(III) ions (ferric nitrate nonahydrate [Fe(NO3)3·9H2O] (98%, Merck)) and diverse pHs (pH 1–9). Figure S3 shows that the optimum pH was obtained at pH 4 and 2 for the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively. These values were coincident with the pKa and the optimum pH values for the complexation of the two acids with Fe(III) ions investigated by Orabi.16

The optimum amount of each 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensor for the detection of the Fe(III) ions was investigated. The absorbance of different solutions containing 0.1 ppm Fe(III) ions and different amounts of the 3-fsa-MSNT or 5-fsa-MSNT sensors from 10 to 70 mg at their optimum pHs was measured. Figure S4 shows that the absorbance of each solution rose gradually with the rise in the amount of each sensor and plateaued starting from 20 and 30 mg for 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively. Therefore, these working amounts (20 mg for the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor and 30 mg for the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor) were utilized for the next investigations.

The response time of reacting 0.1 ppm Fe(III) ions with 20 mg of the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor or 30 mg of the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor at their optimum pHs had been checked. It was found that the response time became constant after 10 s to achieve the steady-state response. Furthermore, 20 s was found to be the reaction time needed for determining the concentrations of Fe(III) ion lower than 0.02 ppm. The fast response of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors may be attributed to using a nanomaterial having a high surface area (mesoporous silica nanotubes) as a scaffold.

The change in color and the absorption spectra of the reaction of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, at their optimum conditions, with different Fe(III) ion concentrations (from 0.0 to 2.0 ppm) are shown in Figure 4 and Scheme 2. It was observed that the absorbance signal at 378 and 495 nm for 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively, increased when the concentration of the Fe(III) ions increased, as shown in Figure 5. In general, the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor’s color changed from pale yellow to red, while the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor’s color switched to violet from pale yellow. The highest concentration of Fe(III) ions that can be determined was 1.3 and 2.0 ppm for the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively. The calibration plots represented in Figure 6 showed that the Fe(III) ions can be determined over a wide range of concentrations (0.0–0.56 ppm by using the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor and 0.0–1.52 ppm by using the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor).

Figure 4.

The absorption spectra and color change of different Fe(III) ion concentrations with the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor at pH 4 (A) and with the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor at pH 2 (B).

Scheme 2. Proposed Methods of Analysis for the Sensitive Determination and Detection of Fe(III) Ions Using the 5-fsa-MSNT Sensor.

Figure 5.

Response curves of 3-fa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors with different Fe(III) ion concentrations at the wavelength of 378 nm and pH 4 for the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor (A) and 495 nm and pH 2 for the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor (B).

Figure 6.

Calibration plots of the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor (A) and 5-fsa-MSNT sensor (B) with different Fe(III) concentrations were measured at absorbances of 378 and 495 nm, respectively.

According to International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines,23 the figures of merit have been calculated and listed in Table 1. The calculated limits of detection (LODs) using the two sensors were very low (0.026 ppm by using the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor and 0.023 ppm by using the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor). Consequently, it is possible to determine ultra-traces of Fe(III) ions using the two sensors with high sensitivity better than other spectrophotometric methods24−30 as shown in Table 2. This may be attributed to the use of mesoporous silica nanotube nanomaterial as a carrier that boosted the sensitive property of the immobilized reagents (formylsalicylic acids), resulting in the high sensitivity of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors.21,31−40 It appears from Table 1 that the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor has a lower LOD than the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor, and this may be because the positions of the hydroxyl and carboxylic groups are farther from the formyl group in the 5-fsa-MSNT structure than in the 3-fsa-MSNT structure. This makes the hydroxyl and carboxylic groups in the 5-fsa-MSNTs directed to the solution and easily react with the Fe(III) ions.

Table 1. The Figure of Merits for the Determination of the Fe(III) Ions by the Spectrophotometric, Fluorometric, and Image Analysis Methods Using the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors.

| 3-fsa-MSNT

sensor |

5-fsa-MSNT

sensor |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | spectrophotometric | fluorometric | image analysis | spectrophotometric | fluorometric | image analysis |

| detection range (ppm) | 0.0–0.56 | 0.0–0.825 | 0.196–0.65 | 0.0–1.52 | 0.0–1.73 | 0.2–1.66 |

| LOD (ppm) | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.050 |

| LOQ (ppm) | 0.079 | 0.069 | 0.092 | 0.057 | 0.070 | 0.153 |

| slope | 1.709 | 3.537 | 4.253 | 0.577 | 4.673 | 0.863 |

| intercept | 1.045 | 1.027 | –0.605 | 0.139 | 0.951 | –0.165 |

| correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.9973 | 0.9984 | 0.9998 | 0. 0.9995 | 0.9993 | 0.9982 |

Table 2. A Comparison of Different Reagent Features Used in the Literature for Spectrophotometric Detection of Fe(III).

| sensor or reagent | linearity range (ppm) | LOD (ppb) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| quercetin | 0.1–15 | 60 | (24) |

| morin | 0.4–15 | 380 | |

| N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediammonium dichloride | 0.1–0.5 | 5 | (25) |

| mixture of sulfosalicylic acid and 1,10-phenanthroline | 0.09–1.0 | 80 | (26) |

| 3,5,7,2′,4′-pentahydroxyflavone | 0.008–0.027 | 0.11 | (27) |

| phenanthroline | 0.040–1.0 | 3.09 | (28) |

| ferron | 0.01–0.1 | 10 | (29) |

| casein-capped gold nanoparticles | 0.01–0.05 | 25 | (30) |

| 3-fsa-MSNT sensor | 0.0–0.56 | 26 | this work |

| 5-fsa-MSNT sensor | 0.0–1.52 | 18 |

Fluorescence Studies on the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors

The fluorescence spectra of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were studied in aqueous media. It was found that the optimum conditions for the fluorometric study (i.e., the amount of sensor, the pH, and the contact time) were the same as those used for the UV–vis study. The suspension solutions of the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor exhibit two UV absorption peaks at 340 and 420 nm, while the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor demonstrates the highest absorption peaks at 300 and 400 nm (Figure 4). The 3-fsa-MSNT sensor shows two strong emission bands at 490 and 550 nm, while the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor shows a very strong emission band at 474 nm, upon the excitation at wavelength 400 nm (Figure 7). The intensity of their emission bands was enhanced upon the addition of Fe(III) ions to the two sensors probably because of the Fe(III) coordination with the phenolic (OH) and carboxylic (COOH) groups of the formylsalicylic acids, while the formyl oxygen is not involved in the binding.16 The findings revealed a proportionate relationship between the Fe(III) concentration and emission intensity, meaning that as the concentration of the Fe(III) ions increased, the emission intensities of the two sensors declined (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Emission spectra for the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors with increasing concentrations of Fe(III) ions at λexc = 400.

Figure 8.

Response curves from the reaction of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors with different Fe(III) ion concentrations at emission measured at λem = 490 nm for the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor (A) and at λem = 474 nm for the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor (B).

The sequential addition of Fe(III) ions (0.0–2.5 ppm) diminished the fluorescence intensity of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors (Figure 7). The fluorometric titrations were performed at optimum conditions to assess the detection limit for the Fe(III) ions. The correlation between the comparative fluorescence intensity of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors was plotted against Fe(III) ion concentration at λem = 490 and 474 nm, respectively (Figure 8). The LOD and limit of quantification (LOQ) for sensing of Fe(III) ions were determined (Table 1). The linear curves of the two sensors indicated that Fe(III) ions could be detected with great sensitivity throughout a wide concentration range (Figure 9). The results showed that the fluorometric method is more sensitive than the UV–vis spectrophotometric method. Also, they showed that the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors have a relatively low limit of detection compared to other previously reported fluorometric sensors (Table 3).41−47

Figure 9.

Calibration plots of the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor (A) and 5-fsa-MSNT sensor (B) with different Fe(III) concentrations measured at emission measured at λem = 490 and 474 nm, respectively.

Table 3. An Overview of the Literature-Reported Nanomaterial-Based Approaches for Fluorometric Detection of Fe(III).

| fluorophore | linearity range (ppm) | LOD (ppb) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUMOF-7II | 0.92–9.3 | 927 | (41) |

| MIL-53(Al) | 0.168–11.2 | 50.3 | (42) |

| boron-doped carbon dots | 0.0–0.893 | 13.51 | (43) |

| carbon polymer dots | 0.011–0.558 | 5.58 | (44) |

| nitrogen-doped and amino acid functionalized graphene quantum dots | 0.027–27.92 | 5.58 | (45) |

| nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots | 0.27–27.92 | 10,000 | (46) |

| Gd(III)–5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin | 0.027–5.58 | 5.47 | (47) |

| 3-fsa-MSNT sensor | 0.0–0.56 | 17.2 | this work |

| 5-fsa-MSNT sensor | 0.0–1.52 | 9.4 |

To analyze the interaction between the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors and the Fe(III) ions, the quenching constant (KSV) was determined at 298 K from the Stern–Volmer equation (Fo/F = 1 + Ksv[Q], where [Q] is the Fe(III) concentration). It was found that the quenching constants were 3.538 and 4.6735 mg–1 L for the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively. Because of the dynamical quenching, these data show that Fe(III) ions have a high quenching capability.

Digital Image Analysis

The digital images of the colored 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors taken by a Samsung Galaxy A71 smartphone camera after adding the Fe(III) ions, as already described above, were measured by the Just Color Picker Software (Scheme 2). All the pixels (column by column) of these color images were scanned to collect the RGB component intensities. These intensities can be expressed in absorbance using the equation A = −log(I/Io),22,48 where Io and I are the intensity values of the blue component for the blank and the sample with the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors, respectively. The blue component was chosen because it supplied the maximum color intensity, as shown in Figure 10. It was noticed that as the concentration of Fe(III) ions increased, so did the absorbance of the blue component of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors. Using the ideal conditions stated above for the spectrophotometric approach, the linear concentration ranges of the Fe(III) ions with the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were found (Figure 11). The LOD and the LOQ of this method were calculated and listed in Table 1. The image analysis method showed relatively great sensitivity compared to the fluorometric and spectrophotometric methods.

Figure 10.

Response curves using the smartphone of 3-fa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors with different Fe(III) ion concentrations at pH 4 for the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor (A) and pH 2 for the 5-fsa-MSNT sensor (B).

Figure 11.

Calibration plots of the 3-fsa-MSNT sensor (A) and 5-fsa-MSNT sensor (B) with different Fe(III) concentrations were measured by the image analysis method.

Selectivity 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors

To discover the possibility of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors for detection of ions, the responses of absorption spectroscopy and the fluorescence emission of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors to various anions and cations were examined. Among the tested metal ions, both 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors only show significant responses to Fe(III) ions. The existence of Fe(III) ions drastically increases the absorbance and decreases the fluorescence emission of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors. The quenching of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors maybe because of the selective reaction of the Fe(III) ions with the carboxylic and phenolic groups of the formyl salicylic acids as mentioned above.

Also, Fe2+ (100 ppm), Mg2+ (500 ppm), Ca2+ (500 ppm), Ba2+ (500 ppm), Co2+ (200 ppm), Ni2+ (200 ppm), Cu2+ (50 ppm), Zn2+ (100 ppm), Pb2+ (100 ppm), Hg2+ (100 ppm), Cd2+ (100 ppm), Cl– (500 ppm), NO3– (500 ppm), and SO42– (100 ppm) were used to test their influence on the determination of Fe(III) (0.2 ppm) by the two sensors. According to the results, no major interferences (more than 5%) from these ions were detected during the determination process (Table 4).

Table 4. The Tolerance Concentration for Interfering Matrix Species during Detection of [0.2 Ppm] Fe(III) Ions Using the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors.

| tolerance

limit for foreign ions (ppm) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sensor | specific pH | Fe2+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Ba2+ | Co2+ | Ni2+ | Zn2+ | Cu2+ | Pb2+ | Hg2+ | Cd2+ | Cl– | NO3– | SO42– |

| 3-fsa-MSNTs | 4 | 10 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 5a | 50 | 50 | 50 | 500 | 500 | 100 |

| 5-fsa-MSNTs | 2 | 10 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 10a | 50 | 50 | 50 | 500 | 500 | 100 |

Ion-sensing system with addition of masking agent of 0.1 M sodium citrate.

Recycling of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT Sensors

The reusability of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors after sensing the Fe(III) has been tested. Many substances have been tested to be the best eluents, but EDTA was found as a perfect recycling reagent. This could be because of its great capacity to remove metal ions from complexes.49 The used 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors can recover their functionality after stirring them with 0.1 M EDTA for 1 h. The recycled 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were exposed again to a solution of Fe(III) ions. This procedure was repeated eight times. The 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors’ sensing efficiency was estimated from the equation (A/Ao)% during the detection of the Fe(III) ions in each recycle, where A is the absorbance of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors after reusability and Ao is the initial absorbance. The findings (Figure S5) showed that the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors kept their efficiency (90%) even after eight-time recycling.

Determination of the Fe(III) Ions in the Real Sample

As the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors have high selectivity and sensitivity, they were checked to determine the Fe(III) ions in the real samples (tap water, river water, seawater, and pharmaceutical sample). The spectrophotometric and fluorometric methods were selected to determine the Fe(III) ions in all samples as they were more sensitive. All the results of the determination by the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors were compared with those obtained using the ICP-OES technique. Table 5 shows that the recoveries of the Fe(III) ions were between 83 and 116%. The spiked Fe(III) ions can be recovered with high precision from these samples, although the real samples are complex and contain components that can be a conflict with calculations. This indicates that the proposed method can be used for the determination of the Fe(III) ions with high selectivity and sensitivity in the real samples.

Conclusions

In this work, novel chemical sensors based on mesoporous silica nanotubes have been used to detect Fe(III) ions in aqueous media. The Fe(III) ions were determined with remarkable sensitivity by the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors that result. The time it took to reach a reliable signal was minimal (less than 15 s). The color of the resultant 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors changed after meeting a very low concentration of Fe(III) ions. Color changes can be seen by the naked eye and tracked with a smartphone or fluorometric or spectrophotometric techniques. The suggested methods were validated in terms of LOD, LOQ, linearity, and precision according to ICH guidelines. The lowest limit of detection obtained from the spectrophotometric technique was 18 ppb for Fe(III) ions. In addition, the results showed that the two sensors can be used eight times after recycling using 0.1 M EDTA as eluent with high efficiency (90%). As a result, the two sensors were successfully used to determine Fe(III) in a variety of real samples (tap water, river water, seawater, and pharmaceutical samples) with great sensitivity and selectivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University for funding this work through Research Group RG-21-09-71.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c05899.

Detailed procedure for the synthesis of the mesoporous silica nanotubes; the reaction between the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors with the Fe(III) ions; the image processing; FTIR spectra of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors; low-angle XRD patterns and wide-angle X-ray diffraction patterns of the MSNT, 3-APTES@MSNT, 3-fsa-MSNT, and 5-fsa-MSNT sensor samples; the effect of pH on the complexation of the Fe(III) with 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors at the maximum wavelengths of 378 and 495 nm, respectively; the effect of the amount of 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors with 0.1 ppm Fe(III) ions on the signal response at the wavelengths of 378 and 495 nm, respectively; and reusability study of the 3-fsa-MSNT and 5-fsa-MSNT sensors in several cycles of sensing operations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Shi D.; Xu Y.; Hopkinson B. M.; Morel F. M. M. Effect of ocean acidification on iron availability to marine phytoplankton. Science 2010, 327, 676–679. 10.1126/science.1183517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V.; Hantke K. Recent insights into iron import by bacteria. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011, 15, 328–334. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin F. A.; Soylak M. Separation, preconcentration and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometric (ICP-MS) determination of thorium(IV), titanium(IV), iron(III), lead(II) and chromium(III) on 2-nitroso-1-naphthol impregnated MCI GEL CHP20P resin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 669–674. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y. M.; Chang X. J.; Zhu X. B.; Jiang N.; Hu Z.; Lian N. ICP-AES determination of trace elements after preconcentrated with p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde-modified nanometer SiO2 from sample solution. Microchem. J. 2007, 86, 23–28. 10.1016/j.microc.2006.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mashhadizadeh M. H.; Shoaei I. S.; Monadi N. A novel ion selective membrane potentiometric sensor for direct determination of Fe(III) in the presence of Fe(II). Talanta 2004, 64, 1048–1052. 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaedi M.; Shokrollahi A.; Mehrnoosh R.; Hossaini O.; Soylak M. Combination of cloud point extraction and flame atomic absorption spectrometry for preconcentration and determination of trace iron in environmental and biological samples. cent. eur. j. chem. 2008, 6, 488–496. 10.2478/s11532-008-0049-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra V.; Das M. K.; Jeyakumar S.; Sawant R. M.; Ramakumar K. L. Rapid Separation and Quantification of Iron in Uranium Nuclear Matrix by Capillary Zone Electrophoresis (CZE). Chem. Mater. Sci. 2011, 02, 46–55. 10.4236/ajac.2011.21005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oktavia B.; Lim L. W.; Takeuchi T. Simultaneous determination of Fe(III) and Fe(II) ions via complexation with salicylic acid and 1,10-phenanthroline in microcolumn ion chromatography. Anal. Sci. 2008, 24, 1487–1492. 10.2116/analsci.24.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soylak M.; Unsal Y. E. Chromium and iron determinations in food and herbal plant samples by atomic absorption spectrometry after solid phase extraction on single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) disk. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1511–1515. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S. K.; Sharma D.; Bera R. K.; Crisponi G. C.; Callan J. F. Iron(III) selective molecular and supramolecular fluorescent probes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7195–7227. 10.1039/c2cs35152h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur K.; Saini R.; Kumar A.; Luxami V.; Kaur N.; Singh P.; Kumar S. Chemodosimeters: an approach for detection and estimation of biologically and medically relevant metal ions, anions and thiols. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1992–2028. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massart D. L.Handbook of Chemometrics and Qualimetrics, first ed., Volume Part A, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Massart D. L.Handbook of Chemometrics and Qualimetrics, first ed., Volume Part B, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Adam M. J.; Hall L. D. Synthesis of metal-chelates of amino sugars: Schiff’s base complexes. Can. J. Chem. 1982, 60, 2229–2237. 10.1139/v82-317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore P. H.; Newman P. J. Quantitative aspects of the colour reaction between Iron(III) and phenols. Anal. Chim. Acta 1964, 31, 111. 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88791-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orabi E. A. Spectroscopic studies on 3- and 5-formylsalicylic acids and their complexes with Fe(III). Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2010, 75, 918–924. 10.1016/j.saa.2009.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M. E.; Soliman E. M. Silica-immobilized formylsalicylic acid as a selective phase for the extraction of iron(III). Talanta 1997, 44, 15–22. 10.1016/S0039-9140(96)01960-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff J. C.; Bills E. J. 273. Reactions between hexamethylenetetramine and phenolic compounds. Part I. A new method for the preparation of 3- and 5-aldehydosalicylic acids. J. Chem. Soc. 1932, 1987. 10.1039/jr9320001987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michau M.; Barboiu M. Self-organized proton conductive layers in hybrid proton exchange membranes, exhibiting high ionic conductivity. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 6124. 10.1039/b908680c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Safty S.; Shahat A.; Ogawa K.; Hanaoka T. Highly ordered, thermally/hydrothermally stable cubic Ia3d aluminosilica monoliths with low silica in frameworks. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 138, 51–62. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Melha K. S.; Al-Hazmi G. A. A.; Habeebullah T. M.; Althagafi I.; Othman A.; El-Metwaly N. M.; Shaaban F.; Shahat A. Functionalized silica nanotubes with azo-chromophore for enhanced Pd2+ and Co2+ ions monitoring in E-wastes. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 329, 115585. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altalhi T. A.; Ibrahim M. M.; Mersal G. A. M.; Alsawat M.; Mahmoud M. H. H.; Kumeria T.; Shahat A.; El-Bindary M. A. Mesopores silica nanotubes-based sensors for the highly selective and rapid detection of Fe2+ ions in wastewater, boiler system units and biological samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1180, 338860. 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Conference on Harmonization, ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline . Validation of analytical procedure: text and methodology; Q2. (R1). Geneva: International Conference on Harmonization: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Balcerzak M.; Tyburska A.; Füchsel E. S. Selective determination of Fe(III) in Fe(II) samples by UV-spectrophotometry with the aid of quercetin and morin. Acta Pharm. 2008, 58, 327–334. 10.2478/v10007-008-0013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro J. M. T.; Dias A. C. B.; Zagatto E. A. G.; Honorato R. S. Spectrophotometric catalytic determination of Fe(III) in estuarine waters using a flow-batch system. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 455, 327–333. 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)01611-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak J.; Jodłowska N.; Kozak M.; Kościelniak P. Simple flow injection method for simultaneous spectrophotometric determination of Fe(II) and Fe(III). Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 702, 213–217. 10.1016/j.aca.2011.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam M. R.; Shabani A. M. H.; Dadfarnia S. Simultaneous spectrophotometric determination of Fe(III) and Al(III) using orthogonal signal correction–partial least squares calibration method after solidified floating organic drop microextraction. Spectrochim. Acta A 2015, 135, 929–934. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Li N.; Zhang X.; Yang D.; Jiang H. Online spectrophotometric determination of Fe(II) and Fe(III) by flow injection combined with low pressure ion chromatography. Spectrochimica Acta A 2015, 138, 375–380. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan Z.; Neagu E. A. Spectrophotometric determination of trace iron(III) in natural water after its preconcentration with a chelating resin. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2002, 67, 669–676. 10.2298/JSC0210669M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y.; Shinde S.; Saratale R.; Syed A.; Ameen F.; Ghodake G. Spectrophotometric determination of Fe(III) by using casein-functionalized gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 184 2017, 4695–4704. 10.1007/s00604-017-2520-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat A.; Ali E. A.; El Shahat M. F. Colorimetric determination of some toxic metal ions in post-mortem biological samples. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 221, 1027–1034. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.07.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat A.; Hassan H. M. A.; El-Shahat M. F.; El Shahawy O.; Awual M. R. A ligand-anchored optical composite material for efficient vanadium(ii) adsorption and detection in wastewater. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 10324–10335. 10.1039/C9NJ01818B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan A.; El-Sewify I. M.; Shahat A.; El-Shahat M. F.; Khalil M. M. H. Decorated nanosphere mesoporous silica chemosensors for rapid screening and removal of toxic cadmium ions in well water samples. Microchem. J. 2020, 156, 104806. 10.1016/j.microc.2020.104806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel R. M.; Shahat A.; Anwar Z. M.; El-Kady H. A.; Kilany E. M. Efficient dual sensor of alternate nanomaterials for sensitive and rapid monitoring of ultra-trace phenols in sea water. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 297, 111798. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat A.; Elsalam S. A.; Herrero-Martínez J. M.; Simó-Alfonso E. F.; Ramis-Ramos G. Optical recognition and removal of Hg(II) using a new self-chemosensor based on a modified amino-functionalized Al-MOF. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 253, 164–172. 10.1016/j.snb.2017.06.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat A.; Trupp S. Sensitive, selective, and rapid method for optical recognition of ultra-traces level of Hg(II), Ag(I), Au(III), and Pd(II) in electronic wastes. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 245, 789–802. 10.1016/j.snb.2017.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat A.; Mohamed M. H.; Awual M. R.; Mohamed S. K. Novel and potential chemical sensors for Au(III) ion detection and recovery in electric waste samples. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105312. 10.1016/j.microc.2020.105312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed W. N.; Elwakeel K. Z.; Shahat A.; Awual M. R. Investigation of novel nanomaterial for the removal of toxic substances from contaminated water. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 14167–14175. 10.1039/C9RA00383E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat A.; Kubra K. T.; Salman M. S.; Hasan M. N.; Hasan M. M. Novel solid-state sensor material for efficient cadmium(II) detection and capturing from wastewater. Microchem. J. 2021, 164, 105967. 10.1016/j.microc.2021.105967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan A.; El-Sewify I. M.; Shahat A.; Azzazy H. M. E.; Khalil M. M. H.; El-Shahat M. F. Multiuse Al-MOF Chemosensors for Visual Detection and Removal of Mercury Ions in Water and Skin-Whitening Cosmetics. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 15097–15107. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c03592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid H. N.; Bermejo-Gómez A.; Martín-Matute B.; Zou X. A water-stable lanthanide metal-organic framework for fluorimetric detection of ferric ions and tryptophan. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 3363–3371. 10.1007/s00604-017-2306-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. X.; Ren H. B.; Yan X. P. Fluorescent metal-organic framework MIL-53(Al) for highly selective and sensitive detection of Fe3+ in aqueous solution. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 7441. 10.1021/ac401387z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Hao Q.; Zhang Y.; Xu Y.; Lei W. Fluorescence quenchometric method for determination of ferric ion using boron-doped carbon dots. Microchim. Acta 2016, 183, 273–279. 10.1007/s00604-015-1650-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J.; Zhuang Y. T.; Yu Y. L.; Wang J. H. Highly fluorescent carbon polymer dots prepared at room temperature, and their application as a fluorescent probe for determination and intracellular imaging of ferric ion. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 1109–1116. 10.1007/s00604-017-2104-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Li L.; Wang C.; Liu K.; Zhu R.; Qiang H.; Lin Y. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped and amino acid-functionalized graphene quantum dots from glycine, and their application to the fluorometric determination of ferric ion. Microchim. Acta 2015, 182, 763–770. 10.1007/s00604-014-1383-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.; Bao W.; Liu T.; Zhang B.; Huang S.; Yang W.; Li Y.; Li N.; Wang C.; Pan C.; Li Y. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots prepared by electrolysis of nitrogen-doped nanomesh graphene for the fluorometric determination of ferric ions. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 322. 10.1007/s00604-020-04294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Wang Y.; Zhao X.; Liu B.; Xu Y.; Wang Y. A gadolinium(III)-porphyrin based coordination polymer for colorimetric and fluorometric dual mode determination of ferric ions. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 63. 10.1007/s00604-018-3171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntzleman T. S.; Jacobson E. C. Teaching Beer’s law and absorption spectrophotometry with a smartphone: a substantially simplified protocol. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 1249–1252. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A. I.Quantitative Inorganic Analysis; 5th edn., Longman: Harlow, 1989. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.