Abstract

The Barakar coal seams of Jharia Basin have been evaluated for the geochemical and petrographic control of coalbed methane (CBM) reservoir characteristics. The coal core samples are analyzed for the total gas content, gas chromatography, stable isotopes (δ13C1), and geochemical, petrographic and vitrinite reflectance. The significant face (1.6–7.6%) and butt (0.9–5.3%) cleat intensities specify the brittle characteristics of coal seams and also favor the gas flow mechanism. The thermal cracking position of hydrocarbon compounds was evaluated, which signifies the excellent source rock potential of coal for gas genesis. The inputs of type III and IV organic matter illustrated by the van Krevelan diagram signify thermally matured coal seams. The low values of sorption time (τ) between 2.1 and 5.6 days designate excellent diffusion characteristics that is favored by the cleat intensities. The values of total gas content and sorption capacity (VL) reveal that moderate saturation indicates a higher gas content, attributed to the seam thickness and thermal maturity. Similarly, the CH4 concentrations (89.4–96.6 vol %) display that the genesis pattern is a function of thermal maturity; however, some samples fall under the mixed type substantiated by the stable isotope (δ13C1) (−25.40 to −64.90‰), emphasizing bacterial hold by seasonal influx of freshwater. The ternary facies diagram (Vmmf, Immf, Lmmf) also supports notable generation of methane gas and storage in the coal seams of the Jharia Basin. The volume percentage of each maceral determined from petrographic study was used to estimate the fraction of conversion (f) of the organic content (0.19–0.97). The values of “f” indicate that the Barakar coal has undergone maximum conversion, which may be attributed to the older early Permian coal and placed at a greater depth after deposition due to the basin sink. The high fraction of conversion and thermal maturity may also be explained due to the existence of volcanic intrusion (sills and dykes). The uniformity in the distribution of functional groups is shown by Fourier transform infrared spectra representing moderate to stronger peaks of aromatic carbon (CO and C=C) between 1750 and 1450 cm–1, which indicates that the presence of a larger total organic carbon content likely validates the removal of aliphatic compounds during gas genesis. The variations in the BET curve have been categorized as H1 hysteresis following the type II adsorption pattern, suggesting that cylindrical pores and some of the coal samples have a type IV H4 hysteresis pattern, characterized as the slit type of pores. The average values of the pore diameter indicate the dominance of mesopores suitable for gas storage and release and hence a major part of the pore volume is contributed by the mesopores having a width mainly between 2.98 and 4.48 nm. The significant role of the meso-macropore network (D1 fractals) in methane storage of the coal matrix is represented by a moderate positive relationship of VL with D1, which accentuated that meso-macropores developed due to devolatilization and dehydration of organic matter and also by geochemical alteration of macerals and minerals formed heterogenetic inner surfaces suitable for gas adsorption. The estimated recoverable resource applying Mavor Pratt methods is 8.78 BCM, which is found to be a more realistic resource value for the studied CBM block.

1. Introduction

Coalbed methane (CBM) is a kind of natural gas which mainly contains methane and occurs in in situ coal seam matrix systems in the adsorbed state.1−6 The conventional coal mining is one of the major causes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission, particularly methane. However, methane extraction prior to and during mining has gained importance as a clean source of fuel that not only mitigates the local pollution but also helps to reduce the emissions of GHG into the atmosphere. Numerous researchers stated that the coal reservoir possesses a number of critical parameters like geological controls, geochemical properties, thermal maturity, depth of occurrence, permeability, in situ gas content, gas storage capacity, fracture, and cleat intensity.3,7−9 These properties of coal seams directly influence CBM assessment and recovery. Several authors have also categorized the coal beds on the basis of the gas content, permeability, rate of gas production, and depth of occurrence, such as coal beds in the ranges of 400–700, 700–1000, and 1000–1500 m and >1500 m. However, for the coal seams having a depth >700 m, there is a reduction in values of the above parameters as a function of hydrostatic and overburden pressure, which affects the CBM resource development.10−12

The gases in coal beds exist in three forms, such as (i) free state—gases held up in cleat and fractures (<3%), (ii) an adsorbed state (>95%) where molecules are adsorbed with physical sorption into the micropores and pore structure of coal surfaces, and (iii) gases very minutely dissolved (<2%) in water as a function of overburden and hydrostatic pressure.13−15 Usually, gas genesis in coal seams occurs mainly by two processes, including biogenic and thermogenic. The gas generated by the thermogenic process follows an abiotic method where the lead role is played by heat and pressure through the geological timescales. However, biogenic gas generation is assimilated through the biotic method where conversion of organic content in coal to methane is carried out by the bacterial process.14,16−18 The reservoir attributes that generally affect the production of CBM are the coal seam thickness, permeability, total gas content, and critical desorption from the coal beds. Moreover, the maceral content, thermal maturity, and kerogen type are the core factors behind the composition and amount of hydrocarbons produced from the coal seams.8,19,20

India has a total coal reserve of about 319 billion tons spread over 17 major coalfields and also comprises laterally varying in situ methane content.21−23 According to the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons (DGH),24 the coal seams of Jharia are thermally matured and hold >15 BCM of methane gas in a block of 85 km2 of area. Further, the coal-bearing basin of India has been categorized into types I, II, III, and IV as per their favorable parameters for CBM exploration and production development.4 Jharia Basin is one of the most promising CBM that belongs to category I. Moreover, in India, the CBM exploration activity has been initiated only from the Jharia Basin. Also, the commercial production has been underway since 2007, but no significant progress has been made because of the lack of a fundamental understanding and confidence on reservoir characteristics. The present CBM production in the Jharia Basin is very low <20 000 m3/day from five to six wells, and continuous efforts are being made to have more wells in the near future.

The parameters controlling CBM generation, adsorption, accumulation, desorption, and production in the Jharia Basin (an equivalent basin of the Damodar valley) are still quite vaguely understood among the researchers and operators. The hypothesis theory of sedimentation, diagenesis, and coalification advises the transformation of organic matter to coking coal, chiefly due to heat received from dykes and sills during the Jurassic–Cretaceous period.25−27 Hence, the basin is variably affected by the igneous intrusion, and the effects of intrusion are sometimes local or regional, which occurs for a short interval of time.28 The intrusion caused the change in the behavior of thermal and geochemical properties of coal. However, the organic-rich material basically acts as an insulator that reduces the effect and causes a narrow transformation zone around the intrusion.29,30 In this process, a large amount of methane might have generated during partial distillation and jump of organic matter. The generated hydrocarbons either adsorbed/stored in pockets or migrated to the nearby porous formation. Several researchers have recorded the issue related to gas blowers near igneous intrusives, which cause safety problems due to methane emission in underground coal mines.31−33 These multicomplex properties, followed by geological history greatly influence the CBM operation in the Jharia Basin.

In this view, an integrated approach by applying different analyses on coal core samples retrieved from seven boreholes such as the geochemical characteristics, total gas content, stable isotopes, desorbed gas molecular composition, petrographic constituents, Rock-Eval pyrolysis, surface area, and pore structure with sorption properties is utilized for better recovery of methane in the Jharia Basin. The geological influences on the gas genesis, storage, maturity, pore structure, and other aspects have been evaluated. Also, the gas recovery and the resource estimation were carried out using different methods. This study is useful to better develop and recover the methane gas from coal seams.

2. Study Site—Jharia Basin

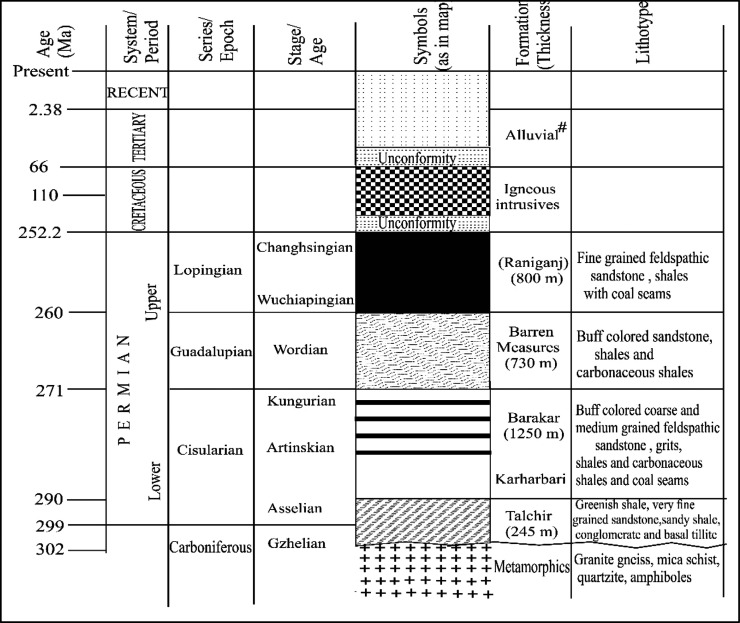

The Jharia coal basin is located near the “Coal Capital of India”, that is, the Dhanbad town and part of the Damodar Valley, which covers an area of about 456 sq km.34−36 This basin is known for prime coking coal deposits having >19 coal seams of laterally varying thicknesses. The basin mainly stretches up to 38 km in the east–west direction, where it extended about 18 km in the north–south direction. It is a roughly sickle-shaped synclinal basin with an east–west alignment of the synclinal axis marked by a major, roughly EW trending, northerly dipping high throw fault.34,37 The basin distends at 23°37′ and 23°52′ latitudes and 86°06′ and 86°30′ longitudes. The simplified geological map marked with coal core sampling borehole locations and also a detailed stratigraphic succession of the Jharia coal basin are exhibited in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Geological map of the Jharia Basin showing borehole locations of the studied samples36,39 (modified after Fox, 1930; CMPDI, 1993).

Figure 2.

Generalized stratigraphic succession of the Jharia Basin35,39 (modified after Fox, 1930; Sengupta, 1980).

The general stratigraphic succession unconformably overlies the basement of metamorphic rocks. The lowest unit has Talchir Formation trailed by coal-bearing Barakar, non-coal-bearing Barren Measures, and coal-containing Raniganj Formations up to tertiary alluvial deposit.34,38,39 The Barakar Formation mainly consists of conglomerates, pebbly sandstones and grits, silty sandstone, siltstone, fireclays, intercalations, carbonaceous shales, and a number of thin to thick coal seams.34,38−41 Due to crustal tension during the epiorogenic movement, there were numerous developments of contemporaneous fault and intrabasinal graben. There were a number of gravity faults present as primary structural developments. These faults are widely distributed in the basin in a scale of few centimeters to microfaults. The faults had affected the lower Gondwana part entirely in the Jharia Basin. The Jharia Basin gets encountered by igneous intrusion as dykes and sills that are basic—ultrabasic in nature. The occurrence of dykes and sills all over the basin has devolatilized the coal reserve extensively.38,39,42 The coal core has been obtained from seven exploratory drilling boreholes, which have encountered the multiple coal horizons in the Barakar Formation. The Barakar formations contain 18 standards of coal horizons (I–XVIII). Although coal seams XIII and above are found to be of superior quality and thin, seams XII–IX/X are of medium quality with a sizeable thickness. However, coal seams II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII are thick but of inferior quality. The details of borehole coal core samples, seam thickness, and the depth of occurrence are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Details of the Studied Coal Core Samplesa.

| cleat/fracture intensity per cm2 (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample no. | depth (m) | borehole no. | coal seam name | seam thickness (m) | MCI | FCI | BCI |

| CG-1103 | 925 | JH#1 | XV | 1.8 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 2.9 |

| CG-1104 | 950 | XIV | 10.5 | 0.8 | 6.3 | 4.6 | |

| CG-1105 | 1038 | XI | 9.8 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 2.9 | |

| CG-1106 | 1102 | JH#2 | XV | 6.5 | 0.4 | 7.6 | 3.4 |

| CG-1107 | 1276 | VIII | 5.0 | 0.6 | 7.4 | 5.3 | |

| CG-1108 | 760 | JH#3 | XVI | 5.4 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 2.6 |

| CG-1109 | 640 | JH#4 | XII | 8.5 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| CG-1110 | 771 | IX | 8.0 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 4.7 | |

| CG-1111 | 665 | JH#5 | XII | 6.0 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| CG-1112 | 750 | X | 5.2 | 0.8 | 5.3 | 4.2 | |

| CG-1113 | 799 | VIII | 5.4 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 3.4 | |

| CG-1114 | 858 | V | 11.6 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 4.1 | |

| CG-1115 | 937 | II | 4.1 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 3.5 | |

| CG-1116 | 186 | JH#6 | XVIIIT | 4.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 2.4 |

| CG-1117 | 215 | XVIIIB | 5.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 2.2 | |

| CG-1118 | 268 | XVIIT | 3.7 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 0.9 | |

| CG-1119 | 470 | XVIIB | 3.8 | 0.6 | 3.4 | 2.8 | |

| CG-1120 | 204 | JH#7 | XVIIIT | 4.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| CG-1121 | 285 | XVIIIB | 5.2 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 2.6 | |

| CG-1122 | 354 | XVII | 3.8 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 2.7 | |

| CG-1123 | 614 | XVI | 3.7 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 2.3 | |

Explanations: MCI—master cleat intensity, FCI—face cleat intensity, BCI—butt cleat intensity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Geological and Geochemical Attributes

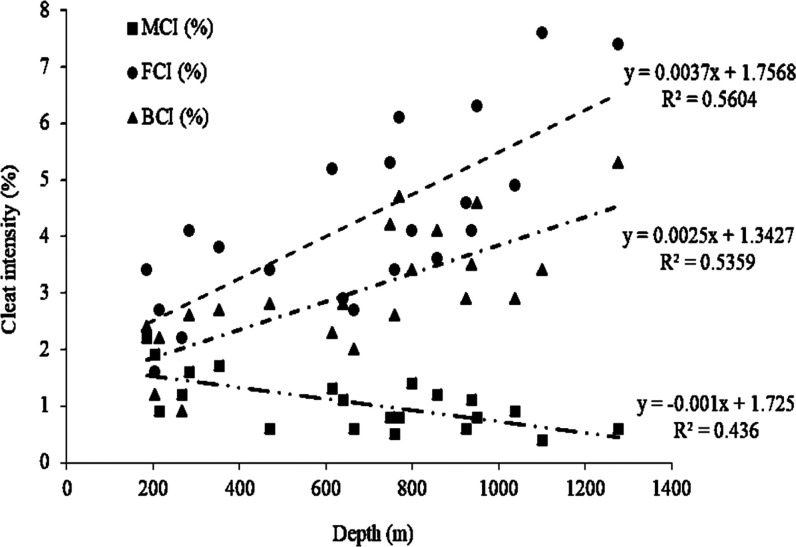

A total of 21 coal core samples were collected from the seven boreholes from the Jharia Basin. The coal seam name, depth of occurrence, thickness, and cleat intensity measured per cm2 area were recorded (Table 1). The thickness of the coal seams laterally varied from 1.80 to 11.60 m with an average thickness of 5.80 m (Table 1). There are three major types of cleat intensity observed, such as the face cleat (cleats usually perpendicular to bedding planes in micrometers), butt cleat (small regular cleats that are parallel to bedding planes measured in micrometers), and master cleat (extensional cleats passing through the entire coal seam from top to bottom perpendicular to the bedding planes, with the length in decimeter).43 The master cleat intensity (MCI), face cleat intensity (FCI), and butt cleat intensity (BCI) vary from 0.4 to 2.2, 1.6 to 7.6, and 0.9 to 5.3%, respectively. The significant intensity of face and butt cleat is attributed to brittle and excellent network connectivity ideal for hydrofracs, resultant permeability, and subsequent recovery of gas.43−45 The occurrence of FCI and BCI with depths is exhibited in Figure 3, showing positive trends (R2 = 0.56 and 0.53), which point toward an increase of the cleat intensity with increasing depth, attributed to the maturity and physico-mechanical changes in coal seams during coalification. However, there are other several factors controlling the cleat/fracture within organic deposits like the sinking of the basin, compaction and devolatalization of organic matter, restructuring, and tectonic movements.22,44 According to Paul and Chatterjee,46 the formation of cleats in the Jharia Basin is mainly controlled by faults, the in situ stress direction, and lineation. Moreover, the negative trend shown by the relation of MCI with depth (R2 = 0.44) specifies comparatively less effects of different stresses on deeper coal seams than shallow coal seams due to the large overburden pressure (Figure 3). Therefore, it can be summarized that cleat in the Jharia coal is the result of multiple geological and tectonic activities, for example, dehydration, devolatilization, and compaction of organic matter and the internal and external basin structural activities.

Figure 3.

Variation in cleat intensity with the depth of coal samples.

The moisture content (Wa), volatile matter content (VMdaf), and ash yield (Ad) of the studied coal samples vary from 0.33 to 1.65, 13.41 to 40.30, and 7.86 to 49.92 wt.%, respectively. The fixed carbon content (FCdaf) of the studied coals ranges from 59.70 to 86.59 (avg. 61.66 wt %) (Table 2). The positive relationship of fixed carbon with depth is shown in Figure 4 (R2 = 0.56). It is emphasized that the carbon content increases at a greater depth because the higher-depth coal seams were subjected to comparatively higher thermal gradients under anaerobic conditions and achieve greater thermal maturity with carbon enrichment. This has been supplemented by the usual negative trend of volatile matter (VMdaf) with depth (Figure 4, R2 = 0.56), demonstrating about the loss of volatile content from the coal seams, maybe due to an increase in the thermal gradient as a function of overburden pressure and tectonics of the basin.25,47−51

Table 2. Geochemical Constituents of Coal Core Samplesa.

| proximate

analysis (wt %) |

ultimate

analysis (wt %) |

atomic

ratio |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample no. | Wa | Ad | VMdaf | FCdaf | FRdaf | Cdaf | Hdaf | Ndaf | Sdaf | Odaf | H/C | O/C | H/O | N/O |

| CG-1103 | 0.72 | 12.84 | 17.70 | 82.30 | 4.02 | 91.27 | 4.39 | 2.20 | 0.67 | 1.47 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 22.27 | 1.10 |

| CG-1104 | 0.33 | 13.68 | 17.53 | 82.47 | 4.05 | 92.33 | 4.14 | 2.37 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 27.00 | 1.29 |

| CG-1105 | 0.41 | 37.28 | 18.91 | 81.09 | 2.68 | 90.49 | 4.03 | 2.06 | 0.55 | 2.88 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 6.43 | 0.32 |

| CG-1106 | 0.82 | 8.71 | 16.58 | 83.42 | 4.56 | 92.32 | 4.30 | 1.85 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 90.14 | 4.20 |

| CG-1107 | 0.71 | 20.72 | 14.93 | 85.07 | 4.49 | 92.73 | 3.98 | 2.07 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 17.78 | 0.96 |

| CG-1108 | 0.82 | 21.84 | 18.83 | 81.17 | 3.34 | 89.44 | 4.02 | 1.49 | 0.48 | 4.57 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 8.20 | 0.38 |

| CG-1109 | 1.11 | 12.24 | 30.92 | 69.08 | 1.94 | 91.85 | 5.31 | 1.63 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 38.09 | 1.51 |

| CG-1110 | 1.65 | 7.86 | 24.66 | 75.34 | 2.77 | 92.86 | 4.94 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 104.92 | 4.06 |

| CG-1111 | 0.95 | 16.51 | 20.15 | 79.85 | 3.28 | 91.75 | 4.77 | 2.15 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 38.69 | 1.94 |

| CG-1112 | 1.21 | 13.91 | 21.04 | 78.96 | 3.19 | 91.67 | 4.71 | 1.83 | 0.81 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 65.53 | 3.29 |

| CG-1113 | 0.95 | 21.95 | 17.28 | 82.72 | 3.70 | 92.44 | 4.27 | 1.70 | 0.41 | 1.18 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 15.41 | 0.76 |

| CG-1114 | 0.99 | 14.23 | 16.91 | 83.09 | 4.17 | 93.20 | 4.14 | 1.61 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 27.12 | 1.32 |

| CG-1115 | 0.72 | 28.37 | 13.65 | 86.35 | 4.50 | 93.69 | 4.04 | 1.40 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 12.89 | 0.56 |

| CG-1116 | 0.36 | 10.74 | 32.13 | 67.87 | 1.88 | 90.56 | 5.12 | 2.59 | 0.68 | 1.05 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 33.76 | 1.42 |

| CG-1117 | 0.76 | 37.65 | 33.17 | 66.83 | 1.25 | 89.83 | 5.54 | 2.15 | 0.81 | 1.66 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 9.92 | 0.45 |

| CG-1118 | 1.38 | 13.19 | 13.41 | 86.59 | 5.53 | 93.60 | 3.55 | 1.51 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 23.44 | 1.49 |

| CG-1119 | 0.55 | 8.00 | 26.49 | 73.51 | 2.54 | 91.62 | 5.01 | 2.52 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 120.26 | 5.42 |

| CG-1120 | 0.86 | 49.92 | 40.30 | 59.70 | 0.74 | 80.00 | 5.46 | 1.99 | 1.18 | 11.37 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 3.64 | 0.19 |

| CG-1121 | 1.00 | 10.50 | 35.87 | 64.13 | 1.58 | 88.68 | 5.03 | 1.83 | 0.79 | 3.67 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 15.98 | 0.68 |

| CG-1122 | 0.89 | 10.46 | 34.48 | 65.52 | 1.69 | 91.51 | 5.42 | 2.09 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 70.06 | 2.88 |

| CG-1123 | 0.62 | 26.47 | 29.40 | 70.60 | 1.76 | 90.58 | 5.32 | 2.55 | 0.90 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 17.50 | 0.81 |

Explanations: Wa—moisture as received, Ad—ash as the dry basis, daf—dry ash-free basis, VM—volatile matter yield, FC—fixed carbon, FR—fuel ratio (FC/VM), C—carbon, H—hydrogen, N—nitrogen, S—sulfur, O—oxygen, H/C—hydrogen and carbon atomic ratio, O/C—oxygen and carbon atomic ratio, H/O—hydrogen and oxygen atomic ratio, N/O—nitrogen and oxygen atomic ratio.

Figure 4.

Change in fixed carbon and volatile matter content with depth of coal samples.

The elemental distribution of ultimate parameters (C, H, S, N, and O) in the studied coal samples on dry ash-free basis varies from 80.00 to 93.69, 3.55 to 5.46, 0.41 to 1.18, 0.80 to 2.59, and 0.32 to 11.37 wt %, respectively (Table 2). The large carbon content and moderate volatile matter values indicate good-quality coal and a potential source for gas genesis and storage. A bivariate plot (H/C and O/C atomic ratios) of the van Krevelan diagram (Figure 5) shows the presence of type III/IV kerogen in the Jharia coal seams. It is interpreted that the coal seams of the Barakar Formation of the Jharia coalfield were subjected to a greater depth and received significant heat from the thermal gradient and volcanic intrusion, for example, sills and dykes (Rajmahal eruption occurred during the Cretaceous period) and therefore were placed in the dry hydrocarbon prone zone.19,22,35,50,52 Similarly, the plot of atomic ratios like H/O and N/O with carbon content of the coal samples (Figure 6) demonstrates the path of coalification with accumulation of cluster points between 84 and 93 wt % of carbon. This cluster may be due to the similarity in the nature of organic matter, the kerogen type, and the coalification process.14,18,27 Further, the continuous reduction in hydrogen content specified by the exponential curve appears to indicate changes in properties due to physicochemical transformation as a function of thermal gradient. However, the high values of H/O compared to N/O signify the unceasing disintegration of hydrocarbon compounds and associated moisture in the late thermogenic stage. The narrow slope of N/O indicates the high reduction of nitrogen from organic matter as the material attains the maximum thermal maturity. Similarly, the relationship of H/O with N/O showing uniformity in the trend of coalification of the coal seams (Figure 7, R2 = 0.9795) also validates the above statement.14,15,53−55

Figure 5.

Plot of H/C and O/C atomic ratios showing the presence of the type of kerogen80 (adopted from van Krevelen Coal: Typology-chemistry-physics-constitution. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, 1993, 963).

Figure 6.

Relationship of carbon content with H/O and N/O atomic ratios showing a trend of coalification.

Figure 7.

Relationship of H/O and N/O atomic ratios showing uniformity in the trend of coalification.

3.2. Gas Potentiality and Storage Capacity

The desorbed gas (DGdaf), lost gas (LGdaf), residual gas (RGdaf), and total gas (TGdaf) of coal seams of the Barakar Formation of the Jharia Basin on a dry ash-free basis (daf) varies from 1.86 to 13.74, 0.18 to 3.35 and 0.30 to 3.32 cm3/g, respectively. The average total gas content at STP is 9.74 cm3/g (Table 3). The sorption time (τ, days), that is, the time required to release 63.21% of desorbed gas measured through the canister test. The estimated values of sorption time range from 2.1 to 5.6 days, indicating excellent diffusion characteristics of the coal seams supported by MCT. The values of reservoir temperature vary from 25.3 to 64.4 OC, specifying that coal seams placed in a significant thermal gradient may upkeep the diffusion and release of gas from the pore-associated matrix to the cleat/fracture system with gas recovery, and a similar statement has been stated by Zhao et al.12 for southeastern Ordos Basin, China. The gas saturation level (GSL) of the samples of various coal seams gives the wide ranges of distributions from 11.30 to 94.72% (Table 3). The usual positive relationship of total gas content with GSL (Figure 8a; R2 = 0.68) indicates that the higher the gas content, the greater the gas recovery. Similarly, the desorbed gas content has shown a positive relationship with GSL (Figure 8b, R2 = 0.80). The GSL displays a negative trend with increasing depth (Figure 8c) of coal seams, specifying that accumulation of gas is influenced by restructural and igneous intrusive activities in the basin.25,35,56,57Figure 8d presents the direct relationship of ash content with total gas content (R2 = 0.47), specifying the inorganic content in coal (mineral and clays) also backing the formation of the pore-associated matrix system in coal which stores gas.22,55,58 Similarly, the positive relationship of desorbed gas with ash content (Figure 8e, R2 = 0.38) indicates that inorganic matter in coal primarily supports the diffusion of gases from pores.59−61

Table 3. In Situ Gas Content, Sorption Capacity, and GSL of Coal Seamsa.

| sample no. | LGdaf (cm3/g) | DGdaf (cm3/g) | RGdaf (cm3/g) | TGdaf (STP, cm3/g) | sorption time (τ, days) | reservoir temperature (°C) | VL (daf, cm3/g) | PL (kPa) | GSL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG-1103 | 0.27 | 4.13 | 1.39 | 5.78 | 5.3 | 54.9 | 20.94 | 3011 | 27.60 |

| CG-1104 | 0.36 | 5.16 | 0.74 | 6.26 | 4.6 | 55.6 | 23.62 | 3069 | 26.50 |

| CG-1105 | 0.86 | 10.84 | 0.82 | 12.52 | 3.9 | 58.0 | 21.21 | 3228 | 59.03 |

| CG-1106 | 0.18 | 2.13 | 0.49 | 2.79 | 3.6 | 59.7 | 24.68 | 3014 | 11.30 |

| CG-1107 | 3.35 | 10.28 | 0.30 | 13.94 | 4.1 | 64.4 | 25.48 | 2545 | 54.71 |

| CG-1108 | 2.12 | 9.11 | 0.80 | 12.02 | 4.2 | 50.5 | 20.28 | 3210 | 59.27 |

| CG-1109 | 1.47 | 1.86 | 0.90 | 4.23 | 4.6 | 47.3 | 27.75 | 3185 | 15.24 |

| CG-1110 | 0.83 | 2.81 | 1.29 | 4.93 | 3.7 | 50.8 | 19.95 | 3150 | 24.71 |

| CG-1111 | 0.81 | 3.85 | 1.87 | 6.53 | 3.5 | 48.0 | 18.34 | 3365 | 35.61 |

| CG-1112 | 2.14 | 7.85 | 1.82 | 11.82 | 2.6 | 50.2 | 20.96 | 3442 | 56.39 |

| CG-1113 | 0.36 | 7.35 | 1.89 | 9.60 | 4.6 | 51.6 | 15.20 | 3216 | 63.16 |

| CG-1114 | 1.12 | 8.93 | 0.68 | 10.73 | 4.7 | 53.2 | 25.17 | 3170 | 42.63 |

| CG-1115 | 0.70 | 3.61 | 3.32 | 7.64 | 5.6 | 25.3 | 17.42 | 3055 | 43.86 |

| CG-1116 | 0.62 | 7.77 | 0.33 | 8.71 | 2.9 | 35.2 | 26.92 | 3612 | 32.36 |

| CG-1117 | 1.03 | 10.65 | 1.00 | 12.69 | 2.5 | 35.8 | 17.75 | 3516 | 71.49 |

| CG-1118 | 0.75 | 8.83 | 0.54 | 10.12 | 2.1 | 37.4 | 24.14 | 3502 | 41.92 |

| CG-1119 | 0.79 | 8.79 | 0.73 | 10.31 | 2.4 | 42.7 | 27.19 | 3313 | 37.92 |

| CG-1120 | 1.79 | 13.74 | 1.15 | 16.68 | 2.3 | 35.5 | 17.61 | 3390 | 94.72 |

| CG-1121 | 0.63 | 7.78 | 0.34 | 8.75 | 2.3 | 37.7 | 19.79 | 3210 | 44.21 |

| CG-1122 | 0.57 | 7.99 | 0.52 | 9.08 | 3.1 | 39.6 | 20.80 | 3025 | 43.65 |

| CG-1123 | 1.00 | 11.73 | 0.62 | 13.34 | 2.1 | 36.6 | 20.94 | 3040 | 63.71 |

Explanations: daf—dry ash-free basis, LG—lost gas, DG—desorbed gas, RG—residual gas, TG—gas content, STP—standard temperature (30 °C) and pressure (760 mmHg), VL—Langmuir volume, PL—Langmuir pressure, GSL—gas saturation level.

Figure 8.

Relationship plots of (a) total gas content (TGdaf, cm3/g) with GSL (%), (b) desorbed gas (DGdaf, cm3/g) with GSL (%), (c) depth (m) with GSL (%), (d) ash dry basis (wt %) with total gas content (TGdaf, cm3/g), (e) ash dry basis (wt %) with desorbed gas content (DGdaf, cm3/g), (f) Langmuir pressure (PL, kPa) with depth (m), (g) sorption time (τ, days) with depth (m), and (h) sorption time (τ, days) with GSL (%).

The Langmuir volume (VL) and pressure (PL) determined from high-pressure methane adsorption isotherm coal samples range from 16.42 to 37.62 cm3/g on a dry ash-free basis (daf) and from 2545 to 3612 kPa (Table 3), respectively. Further, values of VL are high on a dry ash-free basis due to the large ash content attributing to the shaly coals. The values of total gas content compared with maximum sorption values (VL) demonstrate moderately saturated coal seams in the Jharia Basin. The value of Langmuir pressure (PL) decreases with depth VL (Figure 8f, R2 = 0.52), attributed to the attraction of CH4 into the pore surfaces; thus, the lower pressure range will help to recover maximum gas from coal seams.19,25,54,62 The sorption time (τ, days) showed a positive trend with the depth of coal samples (Figure 8g, R2 = 0.49), validating the above results that deeper coal seams have better gas diffusion characteristics controlled by local geology and do not have an impact on gas recovery. Moreover, the inverse relationship of sorption time with GSL (Figure 8h, R2 = 0.42) also suggests that faster recovery of gas from higher-saturation-level coal seams were supported by excellent diffusion characteristics, and a similar statement was recorded by several researchers for the coal seams of their respective study areas.12,22,43,45,50,56,61−63

The adsorption isotherm curve for methane adsorption of the studied coal seams indicates the significance of seam thickness and maturity as seams IX, V, XIV, and XI show a higher adsorbed gas content in them while there are various other features, which play a significant part in adsorption. However, seam X having a thickness of 5.2 m shows a comparable good value of adsorbed gas content relative to other coal seams, maybe due to high thermal maturation (Figure 9a–d).

Figure 9.

(a–d) High-pressure methane adsorption isotherms of studied coal seams.

3.3. Molecular Gas Compositions and Stable Methane Isotopes

The molecular gas composition of studied coals gives predominant occurrence of methane (CH4) with some carbon dioxide (CO2). However, sometimes, CO2 could be even present as the dominant gas with the existence of volume of ethane and higher hydrocarbon compounds (C2+ at deeper intervals) as a function of the biogenic process caused by bacteria.25,54,64 The distribution of molecular composition in the desorbed gas of the Jharia coal seam gives combustible gases (CGs) (including all hydrocarbons), CO2, N2, and O2 observed in the ranges from 83.9 to 93.6, 2.4 to 5.2, 3.6 to 10.5, and 0.1 to 0.8 vol %, respectively (Table 4). The presence of a significant amount of CGs indicates that the coal seams have achieved the thermogenic stage and have generated and stored thermogenic dry gases. Moreover, the large content of CGs is useful to avoid the treatment and process of gas in downstream, which may also reduce the cost of project execution in the study area. The CO2 concentration in the desorbed gas is under permissible limits and derived from the coalification gas genesis process. The high concentration of nitrogen is due to the atmospheric impurity or due to segmentation of O2 and N2 from the air during desorption measurements and gas sample collection.56,65

Table 4. Molecular Composition of Desorbed Gas Received during Canister Core Desorption Measurementsa.

| hydrocarbon

distribution in CG (vol %) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample no. | CG (vol %) | CO2 (vol %) | N2 (vol %) | O2 (vol %) | CH4 | C2H6 | C3H8 | iC4H10 | nC4H10 | C1/(C2 + C3) | δ13C1 (‰) | GSI |

| CG-1103 | 83.9 | 5.2 | 10.5 | 0.4 | 93.8 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 55.2 | –38.2 | 106.4 |

| CG-1104 | 86.7 | 3.5 | 9.6 | 0.2 | 94.3 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 47.2 | –41.2 | 74.1 |

| CG-1105 | 88.4 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 0.2 | 95.7 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 53.2 | –37.1 | 75.2 |

| CG-1106 | 89.9 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 95.9 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 63.9 | –25.4 | 108.8 |

| CG-1107 | 91.2 | 2.4 | 6.2 | 0.2 | 96.3 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 68.8 | –28.7 | 109.2 |

| CG-1108 | 86.5 | 4.0 | 8.9 | 0.6 | 92.8 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 42.2 | –51.7 | 63.2 |

| CG-1109 | 87.2 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 0.4 | 94.3 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 52.4 | –45.8 | 74.1 |

| CG-1110 | 87.9 | 4.8 | 7.0 | 0.3 | 96.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 60.1 | –39.6 | 65.5 |

| CG-1111 | 90.5 | 3.2 | 6.0 | 0.3 | 94.2 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 52.3 | –54.2 | 74.0 |

| CG-1112 | 91.6 | 2.8 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 93.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 62.3 | –42.9 | 119.3 |

| CG-1113 | 92.8 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 94.9 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 39.5 | –34.6 | 57.0 |

| CG-1114 | 93.2 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 0.2 | 95.1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 47.6 | –31.4 | 53.9 |

| CG-1115 | 93.6 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 96.2 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 48.1 | –32.7 | 65.5 |

| CG-1116 | 89.4 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 0.4 | 96.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 45.8 | –64.9 | 61.3 |

| CG-1117 | 88.6 | 3.4 | 7.2 | 0.8 | 96.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 50.8 | –61.4 | 58.0 |

| CG-1118 | 90.1 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 96.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 53.5 | –58.3 | 81.9 |

| CG-1119 | 87.2 | 4.2 | 8.4 | 0.2 | 89.4 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 49.7 | –48.7 | 76.2 |

| CG-1120 | 88.4 | 3.6 | 7.4 | 0.6 | 93.6 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 49.3 | –58.4 | 56.2 |

| CG-1121 | 89.9 | 2.4 | 7.5 | 0.2 | 94.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 42.9 | –52.1 | 45.9 |

| CG-1122 | 91.6 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 95.2 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 47.6 | –58.2 | 69.4 |

| CG-1123 | 90.5 | 2.5 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 95.6 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 53.1 | –41.2 | 75.1 |

Explanations: CH4—methane, C2H6—ethane, C2H4—ethylene, C3H6—propylene, C3H8—propane, iC4H10—ibutane, nC4H10—nbutane, and GSI—gas stability index (CH4/(C2H6+C3H6+C3H8+iC4H10 + nC4H10).

The detailed distribution of various hydrocarbons and non-hydrocarbon gases and stable isotope analyses results are listed in Table 4. The hydrocarbon distribution of CGs mainly consists of CH4, C2H6, C3H8, iC4H10, and nC4H10, which vary from 89.4 to 96.6, 1.2 to 1.9, 0.1 to 0.8, 0.1 to 0.6, and 0.1 to 0.4, respectively. The values of the stable carbon isotope (δ13C1) varies from −25.4 to −64.9‰, and few samples were placed in the mixed-type (biothermo) origin, as indicated by values of the stable isotope, specifying the bacterial influence during the post-maturation caused by the incursion of freshwater through the local drainage pattern.22,56,66,67 The molecular composition and stable isotope values of desorbed gases are considered as significant attributes of analyzing the hydrocarbon genesis pattern.57,67−72 The plot of δ13C1 with depth indicates the greater evolution and accumulation of thermogenic gases with increasing depth (R2 = 0.82) as a function of thermal gradient chiefly contributing the generation of thermogenic gas in the coal seams. The gas stability index (GSI) calculated by considering (Figure 10a) the stability of methane with respect to ethane and other hydrocarbon gases (i.e., CH4/(C2H6 + C3H6 + C3H8 + iC4H10 + nC4H10) ranges from 45.9 to 119.3 (Table 4). It is summarized that high values of GSI represent the methane derived from the thermogenic process and stored in coal seams. The GSI also increases with depth, validating the higher generation of dry thermogenic gases at a greater depth (Figure 10b). However, the bivariate plot of ethane concentrations (C2+) with δ13C1 (Figure 11a) gives the mixed and thermogenic sources from the coal seams of the desorbed gas.67 Here, seams XI and XV (CG1105 and CG1106, respectively) fall under or near the boundary of the late thermogenic origin due to higher depths of these coal horizons. The proportion value of CH4 to C2H6 and C3H8, that is, [C1/(C2 + C3)], ranges from 39.5 to 68.8. The bivariate plot of [C1/(C2 + C3)] with δ13C1 also substantiates the above observation of having the mixed-thermogenic origin of hydrocarbons (Figure 11b). It may be due to the intervention of freshwater through the local river-drainage pattern in coal seams causing microbial degradation trailed by bacterial oxidation.60,66,73,74 A triangular plot for defining the facies behavior of the coal seams using molecular composition of the gases CO2 and N2 and CGs (Figure 12a) displays the trend for hydrocarbon genesis with an increase of maturity. In addition to this (Figure 12b), a ternary plot of N2, O2, and CO2 shows a complete reduction of nitrogen due to coalification of the coal seams.15,25

Figure 10.

Plot of (a) variation in δ13C1 (‰) with increasing depth and (b) GSI values with varying depth of coal seams.

Figure 11.

Genesis pattern of desorbed gas in coal: (a) plot of C2+ and δ13C167 (after Schoell, 1980) and (b) plot of δ13C1 and C1/(C2 + C3)73,74 (after Bernard et al., 1978; Faber and Stahl, 1984).

Figure 12.

Ternary diagram of gas genesis facies of desorbed gases: (a) N2, CO2, and CGs showing a trend of hydrocarbon genesis and (b) O2, CO2, and N2 of desorbed gas showing a cluster of non-combustible gases.

3.4. Maceral Compositions and Maturity

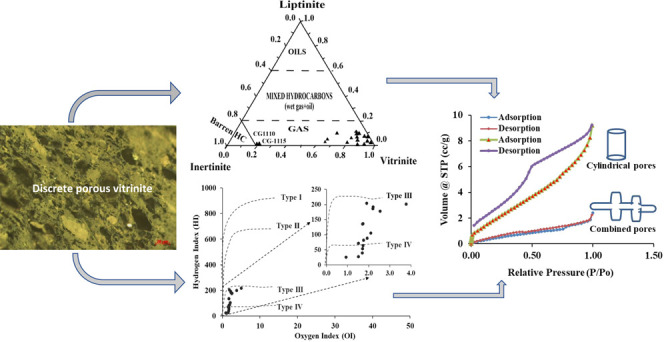

The vitrinite reflectance (mean random; Ro % in oil) of studied coals ranges from 0.65 to 1.81 (avg. 1.06) (Table 5). The V-step reflectograms for the coal seams are given in Figure 13a–d; it shows the prominent maturity peaks of the coal seams, indicating a single source mainly where it can have a very feeble interruption from other sources. The major maceral distribution of the coal seams on a mineral matter-free basis is designated as vitrinite (Vmmf), liptinite (Lmmf), and inertinite (Immf) content (Table 5). The coal seams give dominant input of vitrinite macerals, where it varies from 18.86 to 97.17 vol % in a mineral matter-free basis, whereas the samples CG1110 and CG1115 representing the coal seams show that <20% of vitrinites may be influenced of oxidation.14,19 In addition, the same coal seam shows a relatively high concentration of inertinite content, indicating that organic matter was subjected to partial oxidation under dry conditions and also passed through geochemical alteration.15,22,52,75 The liptinite (Lmmf) percentage varies from non-traceable 11.85 vol % in the studied coals. The low concentration of liptinite in the coal seams supports the high thermal maturation of Jharia coal seams. The inertinite and mineral matter contents vary from 0.81 to 81.14 and 0.37 to 17.47 vol %, respectively. The presence of different macerals, their texture, and pore distribution controlled by the lithotype is presented in Figure 14a–h. It may be observed that a higher density of pores was observed in discrete vitrinite, indicating that the pore-containing matrix is mainly composed of vitrinite macerals like collotelinite and pseudovitrinite. The existence of the fusinite maceral is the result of processes like low-temperature oxidation in early and later stages of coalification.22,27,63,76

Table 5. Petrographic Constituents of Studied Coal Core Samplesa.

| vitrinite (mmf, vol %) |

inertinite (mmf, vol %) |

liptinite (mmf, vol %) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample no. | Te | Co | Vd | total vitrinite (mmf, vol %) | Sf | F | Ind | total inertinite (mmf, vol %) | Sp | Rs | Cu | total liptinite (mmf, vol %) | mineral matter (vol %) | mean random Ro % | random Ro % range |

| CG-1103 | 83.16 | 6.84 | 90.00 | 3.16 | 3.16 | 1.05 | 5.79 | 6.84 | 0.52 | 1.04 | 0.90–1.26 | ||||

| CG-1104 | 79.49 | 10.00 | 89.49 | 3.37 | 3.37 | 0.41 | 6.73 | 7.14 | 2.00 | 1.13 | 0.93–1.29 | ||||

| CG-1105 | 30.81 | 54.03 | 84.83 | 4.74 | 0.47 | 5.21 | 1.90 | 8.06 | 9.95 | 2.31 | 1.13 | 1.01–1.29 | |||

| CG-1106 | 7.16 | 81.65 | 2.82 | 91.63 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 2.02 | 5.54 | 7.56 | 0.80 | 1.32 | 1.07–1.58 | |||

| CG-1107 | 76.98 | 15.08 | 92.06 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 5.56 | 6.75 | 1.18 | 1.50 | 1.04–1.60 | |||

| CG-1108 | 13.95 | 47.23 | 27.23 | 88.42 | 4.51 | 4.51 | 1.28 | 5.79 | 7.07 | 2.08 | 1.00 | 0.86–1.24 | |||

| CG-1109 | 7.09 | 83.82 | 6.27 | 97.17 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 1.62 | 2.02 | 1.20 | 0.83 | 0.71–0.91 | ||

| CG-1110 | 6.74 | 10.88 | 1.24 | 18.86 | 55.24 | 21.24 | 4.66 | 81.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.09 | 1.09 | 0.90–1.28 | |

| CG-1111 | 4.36 | 64.91 | 17.54 | 86.81 | 3.92 | 0.00 | 3.92 | 2.63 | 6.64 | 9.27 | 1.30 | 1.16 | 1.06–1.26 | ||

| CG-1112 | 48.40 | 35.20 | 6.80 | 90.40 | 1.20 | 2.40 | 6.00 | 9.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.49 | 1.29 | 1.11–1.39 | |

| CG-1113 | 50.79 | 32.80 | 10.05 | 93.65 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 5.29 | 6.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 17.47 | 1.27 | 1.13–1.45 | |

| CG-1114 | 51.39 | 13.94 | 65.34 | 7.17 | 21.91 | 29.08 | 0.80 | 4.78 | 5.58 | 2.33 | 1.07 | 0.91–1.23 | |||

| CG-1115 | 1.02 | 18.78 | 19.80 | 23.86 | 55.84 | 79.70 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 4.37 | 1.19 | 1.07–1.28 | |||

| CG-1116 | 70.00 | 17.50 | 87.50 | 3.50 | 5.50 | 9.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 3.50 | 1.96 | 0.80 | 0.70–0.91 | |||

| CG-1117 | 17.07 | 27.99 | 20.52 | 65.58 | 30.16 | 1.49 | 31.65 | 0.75 | 2.02 | 2.76 | 0.37 | 0.75 | 0.65–0.88 | ||

| CG-1118 | 91.13 | 2.96 | 94.09 | 1.97 | 1.48 | 3.45 | 0.49 | 1.97 | 2.46 | 0.98 | 1.81 | 1.42–2.20 | |||

| CG-1119 | 61.19 | 25.37 | 86.57 | 1.49 | 5.97 | 7.46 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 5.97 | 2.90 | 1.05 | 0.95–120 | |||

| CG-1120 | 8.21 | 72.50 | 80.71 | 3.21 | 12.50 | 15.71 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 3.57 | 2.10 | 0.71 | 0.61–0.80 | |||

| CG-1121 | 62.32 | 7.36 | 69.68 | 8.81 | 9.66 | 18.47 | 3.64 | 6.28 | 1.93 | 11.85 | 2.36 | 0.68 | 0.60–0.87 | ||

| CG-1122 | 77.12 | 8.49 | 85.61 | 1.97 | 4.45 | 6.42 | 1.97 | 6.00 | 7.97 | 3.40 | 0.65 | 0.55–0.86 | |||

| CG-1123 | 31.79 | 50.66 | 82.44 | 3.73 | 7.87 | 11.60 | 1.82 | 4.14 | 5.95 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.65–0.99 | |||

Explanations: mmf—mineral matter-free basis, Te—telinite, Co—collodetrinite, Vd—vitrodetrinite, Sf—semifusinite, F—fusinite, Ind—inertodetrinite, Sp—sporinite, Rs—resinite, Cu—cutinite, Ro—vitrinite reflectance.

Figure 13.

(a–d) V-step reflectograms of studied coal samples.

Figure 14.

(a–h) Photomicrographs of coal samples showing macerals and their texture.

The relative percentage of organic matter (vitrinite, liptinite, and inertinite) on an mmf basis (mineral matter-free basis) is plotted in the ternary diagram (Figure 15a), showing that the Jharia coal seams are potentially a good source of gas generation53 apart from CG1110 and CG1115, which lie at the boundary of the barren hydrocarbon region. Similar to this, an apex diagram classifying the apex points as (A = vitrinite + corpogelinite + cutinite + sporinite + resinite; B = vitrodetrinite + liptodetrinite + alginite + gelinite; C = inertinite) gives the indication of paleodepositional conditions of the coal seams which are mostly under anoxic conditions76−78 (Figure 15b). Moreover, a triangular plot of vitrinite, liptinite, and inertinite macerals (Figure 15c) clearly exhibits the trend of maturity that increases with the coalification.

Figure 15.

(a–c) Ternary plot of vitrinite, liptinite, and inertinite showing (a) hydrocarbon potentiality of the samples, (b) depositional conditions, and (c) trend of coalification with maturity.

3.5. Evaluation of Cracking of Hydrocarbon Compounds

The evaluation of the thermal cracking position of hydrocarbon compounds signifies the source rock potential of coal for oil/gas genesis. The total organic carbon content in coal varies from 42.15 to 74.54 (wt %) with an average value of 60.18 (wt %), indicating carbon-rich coal potential for gas genesis and storage. The values of S1 vary from 0.40 to 8.35 (mgHC/g rock), which signify the release of free hydrocarbons up to 300 °C; the S2 values represent the secretion of hydrocarbons by cracking of organic compounds (kerogen) and range from 13.18 to 149.84 (mgHC/g rock), emphasizing the excellent source rock potential of the studied coal. The amount of CO2 release during pyrolysis is shown by peak values of S3 varying from 0.43 to 2.81 (mgCO2/g rock). The maximum temperature of kerogen decomposition is determined as Tmax, and it varies from 441 to 586 °C with an average value 483.62 °C. The values of hydrogen index (HI), oxygen index (OI), and production index (PI) range from 25.0 to 218.0 (avg. 111.05), 1.0 to 5.0 (avg. 2.38), and 0.01 to 0.18 (0.038), respectively (Table 6). The volume percentage of each maceral determined from the petrographic study was used to estimate the fraction of conversion (f) of the organic content (0.19–0.97). The values of “f” indicate that the Barakar coal has undergone maximum conversion, which may be attributed to the older early Permian coal, placed at a greater depth after deposition due to the basin sink. The high fraction of conversion and thermal maturity may also be explained due to existence of volcanic intrusion (sills and dykes) in the Barakar Formation during the Cretaceous period. The values of estimated original hydrogen index (HIo) vary from 101.87 to 332.22, which specify significant conversion of organic compounds (kerogen) to gaseous hydrocarbons during coalification.14,48,52,79 Also, the variation in values of original total organic content ranges from 26.43 to 81.37 (wt %) with an average value of 68.24 (wt %), which implies the role of organic content in hydrocarbon genesis. The relation of OI with HI in the modified80 van Krevelen diagram indicates thermally matured source rocks containing type III–IV kerogen (Figure 16). The reduction in values of HI with an increase in Tmax values suggests extensive cracking of organic compounds as a function of temperature, attributed to a greater thermal gradient at a greater depth (Figure 17a). The plot of S1 + S2 versus total organic carbon (TOC) content indicated very good positive relationship (R2 = 0.706), specifying the major role of organic carbon content in gas generation during thermal maturation of coal (Figure 17b). Similarly, the PI also shows direct relationship with Tmax, indicating larger gas genesis at a higher temperature, attributed to greater cracking of kerogen (Figure 17c).

Table 6. Results of Rock-Eval Pyrolysis and Estimated Indices.

| sample no. | TOC (%) | S1 (mgHC/g rock) | S2 (mgHC/g rock) | S3 (mgCO2/g rock) | Tmax (°C) | HI (mgHC/g TOC) | OI (mgCO2/g TOC) | PI | HIo | f | TOCo | S1 + S2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG-1103 | 42.15 | 0.52 | 18.27 | 1.35 | 495 | 57 | 4 | 0.03 | 324.86 | 0.94 | 54.07 | 18.79 |

| CG-1104 | 59.14 | 1.08 | 34.8 | 1.88 | 500 | 56 | 3 | 0.03 | 324.66 | 0.94 | 74.67 | 35.88 |

| CG-1105 | 49.39 | 0.75 | 13.18 | 0.96 | 508 | 33 | 2 | 0.05 | 323.08 | 0.97 | 60.58 | 13.93 |

| CG-1106 | 61.59 | 1.9 | 49.9 | 1.35 | 499 | 64 | 2 | 0.04 | 332.22 | 0.94 | 81.37 | 51.80 |

| CG-1107 | 55.26 | 0.7 | 16.31 | 0.91 | 520 | 27 | 2 | 0.04 | 330.17 | 0.97 | 74.24 | 17.01 |

| CG-1108 | 63.69 | 1.87 | 52.53 | 1.12 | 490 | 82 | 2 | 0.03 | 321.44 | 0.91 | 75.10 | 54.40 |

| CG-1109 | 71.34 | 8.35 | 126.9 | 1.81 | 458 | 178 | 3 | 0.06 | 325.30 | 0.79 | 78.29 | 135.25 |

| CG-1110 | 67.97 | 5.47 | 92.06 | 1.16 | 467 | 135 | 2 | 0.06 | 101.87 | 0.19 | 69.31 | 97.53 |

| CG-1111 | 61.81 | 1.17 | 65.35 | 1.3 | 483 | 106 | 2 | 0.02 | 325.81 | 0.89 | 74.21 | 66.52 |

| CG-1112 | 65.49 | 1.64 | 58.32 | 1.26 | 489 | 89 | 2 | 0.03 | 298.60 | 0.88 | 74.97 | 59.96 |

| CG-1113 | 56.49 | 1.34 | 47.53 | 1.01 | 492 | 71 | 2 | 0.03 | 307.54 | 0.91 | 75.97 | 48.87 |

| CG-1114 | 61.83 | 1.17 | 38.77 | 1.23 | 498 | 54 | 2 | 0.03 | 252.01 | 0.89 | 77.18 | 39.94 |

| CG-1115 | 53.07 | 0.65 | 20.91 | 0.9 | 510 | 39 | 2 | 0.03 | 106.50 | 0.71 | 57.11 | 21.56 |

| CG-1116 | 73.01 | 2.91 | 140.01 | 1.61 | 453 | 192 | 2 | 0.02 | 304.63 | 0.72 | 78.49 | 142.92 |

| CG-1117 | 49.52 | 0.7 | 36.4 | 0.43 | 452 | 186 | 2 | 0.02 | 241.38 | 0.54 | 28.44 | 37.10 |

| CG-1118 | 56.76 | 4.27 | 19.4 | 0.71 | 586 | 25 | 1 | 0.18 | 318.59 | 0.97 | 80.94 | 23.67 |

| CG-1119 | 72.29 | 2.68 | 102.96 | 1.31 | 461 | 137 | 2 | 0.03 | 311.95 | 0.83 | 79.94 | 105.64 |

| CG-1120 | 45.56 | 0.4 | 33.97 | 0.78 | 441 | 218 | 5 | 0.01 | 286.23 | 0.62 | 26.43 | 34.37 |

| CG-1121 | 74.54 | 2.89 | 149.84 | 2.81 | 447 | 201 | 3 | 0.02 | 289.02 | 0.67 | 78.87 | 152.73 |

| CG-1122 | 64.51 | 3.08 | 125.85 | 1.17 | 448 | 205 | 2 | 0.02 | 317.31 | 0.73 | 72.74 | 128.93 |

| CG-1123 | 58.37 | 1.8 | 78.36 | 1.11 | 459 | 177 | 3 | 0.02 | 300.51 | 0.74 | 60.10 | 80.16 |

Figure 16.

Relation of HI with OI showing dominance of Type III/IV kerogen in coal.

Figure 17.

Rock-Eval constituents showing the trend of thermal maturity: (a) HI versus Tmax, (b) S1 + S2 versus TOC, and (c) PI versus Tmax.

The uniformity in distribution of functional groups is shown by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of coal (Figure 18). The spectra are divided into broad segments, indicating stretching of organic functional groups of O–H (Alcohols and phenols), OH, and Si–OH containing hydroxyl groups, aliphatic stretching of C–H, and CO stretching of aromatic groups. Similarly, the inorganic mineral-containing groups are shown by CO stretching of carbonates, Si–O–Si of quartz, and Si–OH of hydrous silicates (kaolinite). The aliphatic (C–H) moderate stretching with peaks at 3100–2800 cm–1 recorded in all studied coal samples was accredited to reduction in organic carbon content by thermal maturation and the impact of sills and dykes receiving heat contact. The moderate to stronger peaks of aromatic carbon (CO and C=C) between 1750 and 1450 cm–1 indicate the presence of a larger TOC content, likely validating the removal of aliphatic compounds during gas genesis (Figure 18). The irregularities in kaolinite peaks between 3810 and 3620 cm–1 and 8000 and 550 cm–1 signify the presence of hydrous silicate in coal. The distinct quartz peaks between 850 and 1250 cm–1 indicate that the source of the sediment was Granitic-Chotta Nagpur Complex.62,63

Figure 18.

FTIR spectra of coal samples showing OH, Si–OH, C–H, CO, and Si–O–Si stretching.

3.6. Evaluation of Pore Types and Pore Structures in Coal

The low-pressure N2 adsorption and desorption curves give the information about pore types and pore structures.22,55,81,82 The marginal difference in pore structure indicated by the typically open pattern of the adsorption and desorption curves shows abundance of the slit and cylindrical type of pores in studied coal (Figure 19). The variations in curve have been categorized as H1 hysteresis following the type II adsorption pattern, suggesting that cylindrical pores and some of the coal samples have the H4 hysteresis pattern with type IV characterized as the slit type of pores. The multipoint BET (mBET) adsorption determined within the relative pressure range of 0.05 < P/P0 < 0.3515,82 provides information about the pore surface area, which shows a wide category of values from 1.10 to 16.45 m2/g with an average value of 5.542 m2/g. The BJH surface area, pore diameter, and pore volume range from 0.72 to 12.45 m2/g, 2.98 to 4.48 nm, and 0.01 to 0.02 cm3/g, respectively (Table 7). Similarly, the values of surface area, pore size, and pore volume determined following the density functional theory (DFT) model vary from 0.23 to 6.31 m2/g, 0.75 to 4.54 nm, and 0.01 to 0.02 cm3/g, respectively (Table 7). The pores in the coal matrix result from the intermix of organo–inorganic content containing macerals and siliciclastic grains of minerals and clays, pore evolution by devolatilization and dehydration, or the thermal maturation and ablation of the organic material.22,81−83 The average values of pore diameter indicate dominance of mesopores suitable for gas storage and release, and hence, a major part of the pore volume is contributed by the mesopores having a width mainly between 2.98 and 4.48 nm. Further, it is concluded that the coal matrix is sequentially composed of mesopores > macropores > micropores. Moreover, the bimodal distribution pattern and the surface area of the pores with respect to pore size are contributed in a similar fashion as pore volume.15,22,55,63,81,83,84

Figure 19.

Low-pressure N2 sorption isotherms used for determination of surface area, pore size, pore volume, and fractal dimensions of pores in coal samples.

Table 7. Surface Area, Pore Size, Pore Volume, and Fractal Dimensions of Pores in Coal Samples.

| |

|

|

fractal

dimensions |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| surface

area (m2/g) |

pore

volume (m3/g) |

pore

diameter (nm) |

region I (P/P0 = 0–0.5, D1) |

region

II (P/P0 = 0.5–1.0, D2) |

|||||||||||||

| sample no. | mBET | BJH | DFT | BJH | DFT | BJH | DFT | A1 | D1 = 3 + A1 | D1 = 3 + 3A1 | fitting equations | R12 | A2 | D2 = 3 + A2 | D2 = 3 + 3A2 | fitting equations | R22 |

| CG-1104 | 2.082 | 0.881 | 0.872 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 2.990 | 2.769 | –1.1511 | 1.8489 | –0.4533 | y = −0.8707x – 0.9356 | 0.99 | –0.4497 | 2.5503 | 1.6509 | y = −0.4497x-4.1590 | 0.80 |

| CG-1105 | 2.548 | 1.698 | 1.381 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 2.991 | 2.769 | –0.8707 | 2.1293 | 0.3879 | y = −0.9056x – 0.5654 | 0.95 | –0.3355 | 2.6645 | 1.9935 | y = −0.3355x-0.4652 | 0.75 |

| CG-1106 | 2.530 | 1.384 | 1.179 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 2.991 | 2.769 | –0.9056 | 2.0944 | 0.2832 | y = −0.8528x – 0.8092 | 0.99 | –0.5177 | 2.4823 | 1.4469 | y = −0.5177x – 0.3624 | 0.92 |

| CG-1107 | 9.782 | 2.916 | 0.299 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 4.474 | 2.769 | –0.8528 | 2.1472 | 0.4416 | y = −0.3944x – 0.9820 | 0.91 | –0.4736 | 2.5264 | 1.5792 | y = −0.4736x – 0.4073 | 0.83 |

| CG-1108 | 1.102 | 0.715 | 0.232 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 3.339 | 3.169 | –0.3944 | 2.6056 | 1.8168 | y = −0.7426x – 1.0652 | 0.82 | 4.777 | 2.7770 | 17.331 | y = 4.777x – 1.2254 | 0.41 |

| CG-1109 | 4.224 | 2.593 | 2.252 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 4.478 | 2.769 | –0.7426 | 2.2574 | 0.7722 | y = −0.3038x – 0.3900 | 0.99 | –0.3107 | 2.6893 | 2.0679 | y = −0.3107x – 1.0786 | 0.78 |

| CG-1110 | 2.870 | 1.400 | 1.217 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 2.991 | 2.769 | –0.3038 | 2.6962 | 2.0886 | y = −0.6729x – 0.7756 | 0.80 | –0.4441 | 2.5559 | 1.6677 | y = −0.4441x – 0.0983 | 0.87 |

| CG-1111 | 4.785 | 2.532 | 2.003 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 2.989 | 2.769 | –0.6729 | 2.3271 | 0.9813 | y = −1.3458x – 0.5501 | 0.90 | –0.4874 | 2.5126 | 1.5378 | y = −0.4874x – 0.3884 | 0.87 |

| CG-1112 | 3.975 | 2.042 | 1.771 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 3.336 | 2.769 | –1.3458 | 1.6542 | –1.0374 | y = −0.9577x – 0.6114 | 0.91 | –0.4751 | 2.5249 | 1.5747 | y = −0.4751x – 0.1453 | 0.81 |

| CG-1113 | 16.452 | 12.448 | 5.461 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 2.982 | 4.543 | –0.9577 | 2.0423 | 0.1269 | y = −1.7983x – 0.1246 | 0.88 | –0.4532 | 2.5468 | 1.6404 | y = −0.4532x – 0.2037 | 0.82 |

| CG-1114 | 11.192 | 7.485 | 3.169 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 2.988 | 3.169 | –1.7983 | 1.2017 | –2.3949 | y = −0.6761x – 0.1801 | 0.92 | –0.4828 | 2.5172 | 1.5516 | y = −0.4828x+0.4552 | 0.73 |

| CG-1115 | 4.114 | 4.838 | 1.969 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 3.736 | 4.543 | –0.6761 | 2.3239 | 0.9717 | y = −1.3154x – 0.3845 | 0.83 | –0.4947 | 2.5053 | 1.5159 | y = −0.4947x+0.2933 | 0.81 |

| CG-1116 | 5.412 | 2.270 | 4.831 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 2.991 | 0.750 | –1.3154 | 1.6846 | –0.9462 | y = −0.1466x + 0.0091 | 0.91 | –0.5067 | 2.4933 | 1.4799 | y = −0.5067x+0.0726 | 0.79 |

| CG-1117 | 10.614 | 6.460 | 6.313 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 2.985 | 3.627 | –0.1466 | 2.8534 | 2.5602 | y = −1.604x + 0.3096 | 0.70 | –0.2914 | 2.7086 | 2.1258 | y = −0.2914x+0.1408 | 0.92 |

| CG-1118 | 6.484 | 4.731 | 3.273 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 2.989 | 3.169 | –1.604 | 1.3960 | –1.8120 | y = −0.7609x – 0.1873 | 0.97 | –0.4386 | 2.5614 | 1.6842 | y = −0.4386x+0.2767 | 0.88 |

| CG-1119 | 4.632 | 3.093 | 1.937 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 3.154 | 3.169 | –0.7609 | 2.2391 | 0.7173 | y = −0.8087x – 0.9356 | 0.97 | –0.4537 | 2.5463 | 1.6389 | y = −0.4537x+0.1077 | 0.85 |

| CG-1120 | 4.817 | 3.127 | 2.463 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 2.988 | 3.627 | –0.8087 | 2.1913 | 0.5739 | y = −1.5703x – 0.3276 | 0.95 | –0.4261 | 2.5739 | 1.7217 | y = −0.4261x – 0.5107 | 0.77 |

| CG-1121 | 5.288 | 3.014 | 2.030 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 2.988 | 3.169 | –1.5703 | 1.4297 | –1.7109 | y = −0.9229x – 0.5767 | 0.99 | –0.4877 | 2.5123 | 1.5369 | y = −0.4877x – 0.1185 | 0.83 |

| CG-1122 | 4.441 | 2.833 | 2.463 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 3.338 | 3.169 | –0.9229 | 2.0771 | 0.2313 | y = −1.2095x – 0.7929 | 0.89 | –0.5032 | 2.4968 | 1.4904 | y = −0.5032x-0.113 | 0.81 |

| CG-1123 | 3.476 | 2.278 | 1.555 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 2.988 | 2.769 | –1.2095 | 1.7905 | –0.6285 | y = −1.4625x – 0.7365 | 0.88 | –0.5903 | 2.4097 | 1.2291 | y = −0.5903x – 0.2866 | 0.83 |

3.7. Effects of Thermal Transformation on the Pore Structure and Fractals of Coal

The pore evolution and formation of pore-rugged surfaces are the simultaneous processes occurring during thermal transformation of organic matter under compaction and the heat gradient. The pore-rugged internal surfaces are known as fractals, which favor the gas adsorption in the coal. Several authors have recorded that more the fractal dimension, more the gas adsorption in coal.85−87 Therefore, the understanding about the type of fractal in pores has become important to evaluate the storage and flow behavior of gas in the coal matrix to fractures of the coal seam gas reservoir. The fractal dimension has been evaluated by following the Frenkel–Halsey–Hill (FHH) model by unraveling the relative pressure in two distinct paces as Region I (P/P0 = 0.0–0.5; D1) and Region II (P/P0 = 0.5–1.0; D2) (Table 7).63,85,88 Following the FHH model, the straight line A and the fractal dimension D depend on the value of A. For these regions, fractal dimensions D1 and D2 (Figure 20) were determined independently along with the slope of the regression line (A1 and A2) at the two distinct ranges of relative pressure (P/P0) (Table 7). The two different gradients that separate the data into two ranges and the fractal dimension D were calculated from the gradient (D = gradient + 3). Two distinct separated sections (Figure 20) show linear relation having very good to excellent correlation coefficients (R12 = 0.70–0.99 for A1 and R22 = 0.41–0.92 for A2), signifying fractal nature of coal pores. The fractal fitting coefficients for region I and region II indicate that fractal dimensions at these two regions are different.63,85 The values of fractal dimensions D1 and D2 vary from 1.2017 to 2.8534 and 2.4097 to 2.7770, respectively. The variation in fractals is also due to variation in thermal maturity (R0 % = 0.65 to 1.60). The maximum values of D1 and D2 are observed in coal sample CG-1108, which has a maximum reflectance value of 1.60%, validating the thermal controls on genesis of fractals in coal pores (Table 5). The fractal dimension D1 represents meso-macropores, whereas D2 represents micropores. Moreover, it also indicates distinct partings of two phases on the nitrogen adsorption process like Langmuir monolayer adsorption, followed by multilayer adsorption and subsequent pore fillings.22,63,84,85,89,90 The fractal dimension values, particularly D2, are close to 3, exhibiting that the pore surfaces, pore structure, and their openings are favorable for gas interactions on pore surfaces, pore openings, and diffusion.22,63,85,89 The positive trend of Tmax with fractals indicates volatiles associated with the hydrocarbon compound cracked during thermal transformation and evolved pores contributing to the formation of fractals (Figure 21c). Similarly, the thermal maturation of organic matter during the coalification process formed different types of fractals in pores associated with the matrix system as a function of dehydration and devolatilization (Figure 21d).

Figure 20.

Two distinct fractal dimensions (D1 and D2) present in pores of coal samples.

Figure 21.

Relation of maximum sorption capacity (VL) with fractal dimensions D1 and D2: (a) VL versus D1 showing that fractals of meso-macropores have excellent methane sorption capacity, (b) VL versus D2 exhibits fractals of micropores making negligible contribution in the methane sorption mechanism, (c) Tmax versus fractal dimension (D1 and D2), and (d) mean random Ro % versus fractal dimension (D1 and D2).

3.8. Controls of Fractals on the Gas Adsorption Pattern

The pore fractal surfaces playing an important role in the methane sorption mechanism are shown by relation of maximum sorption capacity (Langmuir volume, VL) in Figure 21. The significant role of the meso-macropores network (D1 fractals) in methane storage of the coal matrix is represented by moderate positive relationship of VL with D1 (R2 = 0.7401; Figure 21a). It is emphasized that meso-macropores developed due to devolatilization and dehydration of organic matter, and also, geochemical alteration of macerals and minerals formed heterogenetic inner surfaces suitable for gas adsorption. The positive trend with negligible correlation (R2 = 0.1835) is shown by relation of VL versus D2 (Figure 21b). The minor correlation between fractal dimension D2 and VL indicates that hydrous-anhydrous fractal surfaces are not suitable for monolayer adsorption. Therefore, it is summarized that micropores restrict gas sorption or interactions due to closed or narrow openings influenced by secondary minerals or volatile matter.22,63,85−87,89,91,92 Further, the low correlation suggests the influence of the dissolution of minerals and rock interactions caused due to geochemical weathering occurring during the pre- and post-deposition of coal seams, resulting in the reduction in fractal surfaces.

3.9. Reserve Estimations and Gas Recovery

The generalized method used for the reserve estimation of any basin is given as eq 1

| 1 |

where Gi—total gas resource, A—drainage

area for gas, h—coal bed thickness,  —pure coal density, and TG—total

gas content.

—pure coal density, and TG—total

gas content.

Since the above-expressed method applied for resource estimations has limitations due to inadequate attributes, namely, thickness, gas, and content drainage area. The estimation of CBM resources is influenced by coal seam thickness, burial depths, continuity, coal density, gas content, ash yield, maturity, and porosity. Further, a method of resource estimation suggested by Mavor and Pratt93 is found to be a more realistic approach. Because in this method moisture, saturated pores, and fractures are also considered, this needs to be subtracted while carrying out the resource estimation.

The empirical eq 2 of Mavor and Pratt used for CBM reserve calculations is as follows:

| 2 |

where Gi—estimated gas resource, A—area of the studied block, h—coal seam thickness, ϕf—proportion of cleat/fracture porosity, Swfi—water saturation in fractures, Bgi—initial reservoir pressure gas formation volume factor, Cgi—initial adsorbed gas content, lc—coal seam density, fa—ash content in fraction, and fm—moisture content in fraction.

In addition to the above calculation, the recovery factor can be estimated by the adsorption isotherm. The values of total gas and residual gas content are plotted to obtain abandoned gas pressure and the initial desorption pressure. This gives eq 3 for the recovery factor as follows (Figure 22):

| 3 |

where Rf = estimated recovery factor, Csgi = initial gas content, and Csga = abandonment gas content.

Figure 22.

Estimation of the gas recovery factor from the measured adsorption isotherm and initial in situ gas content.

Applying eq 4, the recoverable reserve could be estimated

| 4 |

Since pressure depends on several factors, namely, coal bed homogeneity, aquifers, and seasonal rainfall, the estimation of average reservoir pressure under abandonment conditions is difficult to obtain using this method.93 The accuracy of the resource estimation lies in the data type and amount also. Table 8 shows the reserve estimation and gas recovery of CBM from the Parbatpur area of the Jharia Basin. The estimated recoverable resource applying generalized and Mavor and Pratt methods gives the values of 6.67 and 8.78 BCM, respectively (Table 8). Since the accuracy of the data depends on the parameters selected during the calculation, the Mavor and Pratt method was found to be a more realistic approach for resource estimation. It is found that from seam V, up to 1.85 BCM (Figure 23) of CBM gas recovery is possible, where seams XIV and XI also give the good possibility of recoverable gas of 1.29 and 1.43 BCM, respectively. The estimated values of resource potentiality are nearly close to the data out by DGH.4 However, the estimation made in this study is more site-specific, limited to a 9 km2 area, as marked in Figure 1.

Table 8. CBM Reserve Estimation of the Jharia Coal Basin of Studied Coal Seamsa.

| generalized

method (BCM) |

Mavor

and Pratt (BCM) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seam name | A (m) | h | Φf | Bgi | Swfi | TG | lc | fa | fm | Rf | Gi1 | Rr | Gi3 | Rr |

| XV | 9 × 106 | 4.15 | 9.75 | 0.93 | 0.3 | 4.345 | 1.35 | 0.1197 | 0.0077 | 0.74 | 0.219 | 0.161 | 0.47 | 0.34 |

| XIV | 9 ×106 | 10.50 | 11.70 | 0.96 | 0.3 | 6.38 | 1.35 | 0.1520 | 0.0033 | 0.87 | 0.814 | 0.705 | 1.49 | 1.29 |

| XI | 9 ×106 | 9.80 | 8.70 | 0.88 | 0.3 | 13.40 | 1.35 | 0.4142 | 0.0041 | 0.93 | 1.596 | 1.484 | 1.54 | 1.43 |

| VIII | 9 ×106 | 5.20 | 11.10 | 0.95 | 0.3 | 12.13 | 1.35 | 0.2370 | 0.0083 | 0.98 | 0.766 | 0.750 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| XVI | 9 ×106 | 5.40 | 6.50 | 0.96 | 0.3 | 12.41 | 1.35 | 0.2427 | 0.0082 | 0.93 | 0.814 | 0.756 | 0.84 | 0.78 |

| XII | 9 ×106 | 7.25 | 6.05 | 0.92 | 0.3 | 5.49 | 1.35 | 0.1597 | 0.0103 | 0.73 | 0.484 | 0.353 | 0.70 | 0.51 |

| IX | 9 ×106 | 8.00 | 11.60 | 0.92 | 0.3 | 4.98 | 1.35 | 0.0873 | 0.0165 | 0.65 | 0.484 | 0.313 | 1.07 | 0.69 |

| X | 9 ×106 | 5.20 | 10.30 | 0.92 | 0.3 | 12.03 | 1.35 | 0.1546 | 0.0121 | 0.82 | 0.760 | 0.622 | 1.00 | 0.82 |

| V | 9 ×106 | 11.60 | 8.90 | 0.92 | 0.3 | 10.93 | 1.35 | 0.1581 | 0.0099 | 0.93 | 1.540 | 1.436 | 1.99 | 1.85 |

| II | 9 ×106 | 4.10 | 8.70 | 0.86 | 0.3 | 7.99 | 1.35 | 0.3152 | 0.0072 | 0.23 | 0.398 | 0.091 | 0.53 | 0.12 |

| total resources (BCM) | 7.87 | 6.67 | 10.59 | 8.78 | 7.875 | 6.670 | 10.59 | 8.78 | ||||||

Explanations: Gi—total gas resource, A—gas drainage area, h—net coal thickness, Φf—cleat/fracture effective porosity, Swfi—fracture water saturation, Bgi—formation volume factor of gas at initial reservoir pressure, lc—pure coal density, fa—ash content by weight, fm—moisture content by weight, TG—gas content, Rr—recoverable resource, and Rf—recovery factor.

Figure 23.

Distribution of recoverable gas from different coal seams93 (estimated following the method suggested by Mavor and Pratt improved methodology for determining total gas content, vol. II. Comparative evaluation of the accuracy of gas-in-place estimates and review of lost gas models, Gas Research Inst., Topical Rep.1996, GRI-94/0429).

4. Summary and Conclusions

The Jharia Basin is considered most prospective for CBM resources. However, the lack of systematic information on methane resource genesis and an understanding of other parameters are major concerns for CBM resource development. The coal seams of the Jharia Basin have been evaluated for geologic, geochemical, petrographic, gas potentiality, and sorption characteristics. The conclusions obtained from these analyses are as follows:

-

i.

The significant intensity of face and butt cleats is attributed to the brittle and excellent network connectivity ideal for the hydrofracs, resultant permeability, and subsequent recovery of gas.

-

ii.

The chief input of type III and IV organic matter signifies thermally matured coal seams as ideal for CBM resource development.

-

iii.

The cleat intensity and the low sorption time (τ) indicate favorable diffusion characteristics of the coal seams. Coal seams IX, V, XIV, and XI show a comparatively higher adsorbed gas content, attributed to the seam thickness and maturity.

-

iv.

The values of the total gas content compared with maximum sorption values (VL) demonstrate moderately saturated coal seams in the Jharia Basin.

-

v.

The high CH4 concentrations in coal seams are a function of thermal maturity; however, few samples were placed in the mixed type (biothermo) origin, as indicated by values of the stable isotope (δ13C1), specifying the bacterial influence caused due to an influx of fresh water during post-maturation.

-

vi.

The significant concentration of liptinite and vitrinite suggests the good gas generation potential of the coal seams. This has been substantiated by ternary facies, indicating the dominance of vitrinite and having type III–IV organic matter favoring the generation and storage of gas in coal seams of the Jharia Basin.

-

vii.

The values of “f” (factor of conversion of organic matter) indicate that the Barakar coal has undergone maximum conversion, which may be attributed to the older early Permian coal and placed at a greater depth after deposition due to the basin sink. The high fraction of conversion and thermal maturity may also be explained due to the existence of volcanic intrusion (sills and dykes).

-

viii.

The average values of pore diameter indicate the dominance of mesopores suitable for gas storage and release and hence a major part of the pore volume is contributed by the mesopores.

-

ix.

The significant role of the meso-macropore network (D1 fractals) in methane storage of the coal matrix is represented by a moderate positive relationship of VL with D1, which accentuated that meso-macropores developed due to devolatilization and dehydration of organic matter and also by geochemical alteration of macerals and minerals formed heterogenetic inner surfaces suitable for gas adsorption.

-

x.

The recoverable resource estimated by generalized and Mavor and Pratt methods seems to be significant for CBM resource development. From seam V up to 1.85 BCM of CBM, gas recovery is possible, where seams XIV and XI also give the good possibility of recoverable gas of 1.29 and 1.43 BCM, respectively.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Geochemical Analysis

The geochemical properties are the principal indicators of the organic matter content.22,47,52,55,63 The coal core samples were manually crushed and sized to 72 mesh by sieving for determining the proximate parameters such as the moisture content, volatile yield, ash yield, and content of fixed carbon using the standard method recommended by the Bureau of Indian Standards.94 An Elementar-Vario MACRO Analyser was used to determine the ultimate parameters of coal samples following the standard method laid down by the American Society for Testing and Materials.95−97

5.2. Determination of the Total Gas Content

The total gas content in coal is the most important parameter for CBM resource development. The coal core samples are retrieved from boreholes collected in airtight temperature-controlled (reservoir temperature) desorption canisters. The direct method was used for estimation of the total gas content, as advised by Bertard et al.98 and further revised by numerous authors.99−102 The total gas content was measured in three steps, such as the estimation of lost gas (Q1), desorbed gas obtained from the canister test (Q2), and residual gas determined by crushing the samples in a ball mill (Q3). The total gas volume was calculated by the sum of Q1, Q2, and Q3, further divided by the weight of the sample, given the total gas content (Q) of the coal sample.6,15,47,54,56

5.3. Composition of Desorbed Gas and Isotope Analysis

The gas samples were obtained during desorption measurements of coal cores in a saline water medium in a glass sampling tube during desorption measurements to avoid the contamination and dissolution of desorbed gases. The distribution of hydrocarbons and non-hydrocarbons was analyzed using a Chemito, model: 1000 gas chromatograph. The desorbed gas samples were examined for hydrocarbon distribution (CH4, C2H6, and C3H8) by applying a flame ionization detector, whereas the presence of non-hydrocarbons, viz. N2 and CO2 has been analyzed using a thermal conductivity detector. The stable δ13C1 isotope of desorbed gas samples was determined using a mass spectrometer (make: Finnigan, Model Mat 251). To prevent cross contamination, CH4 and C2H6 were oxidized in different CuO ovens. The products of combustion of CO and HO were frozen into different gathering containers.

5.4. Rock-Eval Pyrolysis and TOC

Rock-Eval pyrolysis gives information on the type of organic matter within the coal samples. A Rock-Eval 6 pyrolyser installed at KDMIPE Dehradun, India, was used to determine the TOC, the content of free hydrocarbon expending the S1 curve, the content of thermally crackable hydrocarbon compounds by the S2 curve, and the total yield of carbon dioxide released during pyrolysis by the S3 curve, and the maximum temperature required for cracking of hydrocarbon compounds was recorded as Tmax. The TOC and pyrolysis parameters have been used to compute the present-day HI, OI, and PI.15,52,103 The percentages of the maceral (vitrinite, liptinite, and inertinite) obtained from the petrographic study were used to estimate the values of original hydrogen index (HIO), applying the equation of Jarvie et al.103 (eq 5). Moreover, the present-day HI and HIO values derived from Rock-Eval pyrolysis were taken to calculate the factor of kerogen conversion to hydrocarbon (f)15,25,79,104,105 following eq 6. Similarly, the the original total organic carbon content (TOCO) was estimated from HIO, HI, and TOC values along with the f parameter eq 7. The value of PIo was assumed to be 0.60 for calculation purposes.

| 5 |

|

6 |

| 7 |

5.5. Maceral and Maturity

The detailed organo-petrography of coal pellets was carried out using the reflected and fluorescence light under oil immersion using a Carl Zeiss, model: AxioImager.m2M following the standard techniques as advised by ICCP106−110 and ASTM,111 which was further proceeded by International Standard of Organizations.112 The detailed petrographic constituents were identified and are listed in Table 4. Subsequently, the thermal maturity indicator vitrinite reflectance (Ro %) measurements have been carried out on the same coal pellet samples. The vitrinite reflectance (mean random) counts were measured on a Leica MPV-II petrographical microscope following the standard procedures.109,110,113

5.6. FTIR Spectroscopy

The coal samples were analyzed for FTIR spectroscopy to find out the transformation situation of the functional group following Painter et al.114 The coal samples were crushed and sieved to size 212 μm and formed pellets. Further, the pellets were dried at 75 °C in a vacuum oven for about 48 h to avoid the influence of moisture on the spectra. The spectra were recorded in the wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm–1 in the absorbance mode using a Bruker 3000 Hyperion microscope compounded with a VERTEX 80 FTIR system at the Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility in the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IITB), in Mumbai, India. The wavenumber repeatability was better than ±0.01 cm–1. The Gaussian function in Fityk 1.3.1 software was used to fit the curve of the raw spectra.

5.7. High-Pressure Sorption Isotherm

The methane sorption capacity at high pressure was obtained through the volumetric technique, as ascribed by several workers.15,22,25,50,58,59,61,63,115–116,117 The determination of a high-pressure adsorption isotherm was usually carried out in three stages as equilibrium moisture preparation of the sample, estimation of void volume after putting the samples in the sample cell, and finally the measurement of adsorption capacity. The manually crushed sample of −0.630 + 0.400 mm size of 80–90 g weight was equilibrated and taken in a sample cell and then the system was evacuated. Afterward, the reference cell was filled up with helium and connected to the sample cell, allowing to equilibrate. The drop in pressure was used to estimate the dead volume of the system after putting the samples following Boyle’s law. As the void volume was estimated, the helium in the apparatus was vented and the apparatus was vacuumed for the adsorption isotherm process. The adsorbate (methane) was then loaded into the reference cell where it was equilibrated and then added to the sample cell. The adsorbed gas amount was determined by the equilibrium pressure after connecting the reference cell to the sample cell. The loading of gas in the reference cell and connection to the sample cell were repeated with each step of increasing pressure at 8–10 times until the highest pressure was achieved. The quantity of gas adsorbed was estimated using the equilibrium pressure. The sorption constants like VL and PL were calculated following the Langmuir monolayer model by incorporating the z-factor corrections according to Hall and Yarborough equations.117

5.8. Fractal Analysis

The surface area, pore size, pore volume, pore structure, and fractal dimensions of pores were determined by low-pressure N2 adsorption and desorption isotherm measurements using a Quantachrome AutosorbiQ2 MP-XR system at CSIR-CIMFR, Dhanbad. The detailed experimental procedures (BET) are given by several researchers.49,63,81,118 The adsorption and desorption isotherms were performed by injecting N2 (purity 99.99%) at 77 K (−196 °C) under a liquid nitrogen environment. The relative pressures were maintained between P/P0 of 0.00 and 0.99, where P is the balance pressure and P0 is the saturation pressure.49,60,63,89,119 The fractal dimensions were determined using the FHH equation.49,63,81,89

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the Director, IIT (ISM), and the Director, CSIR-CIMFR, Dhanbad, for granting consent to publish this paper. The authors are thankful to the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGC) for their help in the field and laboratory studies.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Diamond W. P.Evaluation of the methane gas content of coalbeds: part of a complete coal exploration program for health and safety and resource evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Coal Experimenta Symposium; Miller Freeman Publications: San Francisco, CA, 1979, pp 211–227.

- Alpern B. Pour une classification synthetiqueuniverselle des combustibles solides. Bull. Cent. Rech. Explor.-Prod. Elf-Aquitaine 1981, 5, 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Flores R. M. Coalbed methane: From hazard to resource. Int. J. Coal Geol. 1998, 35, 3–26. 10.1016/s0166-5162(97)00043-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGlade C.; Speirs J.; Sorrell S. Unconventional gas - A review of regional and global resource estimates. Energy 2013, 55, 571–584. 10.1016/j.energy.2013.01.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strąpoć D.; Mastalerz M.; Dawson K.; Macalady J.; Callaghan A. V.; Wawrik B.; Turich C.; Ashby M. Biogeochemistry of microbial coal-bed methane. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2011, 39, 617–656. [Google Scholar]

- Mendhe V. A.; Kamble A. D.; Bannerjee M.; Mishra S.; Mukherjee S.; Mishra P. Evaluation of shale gas reservoir in Barakar and barren measures formations of north and south Karanpura Coalfields, Jharkhand. J. Geol. Soc. India 2016, 88, 305–316. 10.1007/s12594-016-0493-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creedy D. P. An introduction to geological aspects of methane occurrence and control in British deep coal mines. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 1991, 24, 209–220. 10.1144/gsl.qjeg.1991.024.02.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]