Resumo

A prevalência de obesidade e insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção preservada (ICFEP) aumenta significativamente em mulheres na pós-menopausa. Embora a obesidade seja um fator de risco para disfunção diastólica do ventrículo esquerdo (DDFVE), o mecanismo que liga a interrupção da produção de hormônios ovarianos, especialmente o estrogênio, ao desenvolvimento da obesidade, DDFVE, e ICFEP em mulheres em processo de envelhecimento não é claro. Estudos clínicos e epidemiológicos demonstram que mulheres na pós-menopausa com obesidade abdominal (definida pela circunferência de cintura) têm risco maior de desenvolver a ICFEP do que homens ou mulheres sem obesidade abdominal. Este estudo analisa dados clínicos que corroboram a existência de uma ligação de mecanismo entre a perda de estrogênio mais obesidade e o remodelamento ventricular esquerdo com ICFEP. Ele também discute os possíveis mecanismos celulares e moleculares para a proteção mediada por estrogênio contra tipos de células, depósitos de tecidos, função e metabolismo de adipócitos negativos que podem contribuir para a DDFVE e a ICFEP.

Keywords: Estrogênio; Obesidade; Insuficiência Cardíaca; Volume Sistólico, Menopausa; Adiposidade; Sobrepeso; Ecocardiografia/métodos; Índice de Massa Corporal

Introdução

A prevalência da obesidade está aumentando constantemente em todo o mundo.1 Como a obesidade está associada à mortalidade alta e ao desenvolvimento de comorbidades, incluindo diabetes mellitus e doenças cardiovasculares (DCV), ela é um dos problemas de saúde pública mais difíceis enfrentados por nossa sociedade. Esse grupo de comorbidades relacionadas à obesidade, direta ou indiretamente (por exemplo, efeito colateral de quimioterapia com antraciclinas)2 frequentemente culmina em insuficiência cardíaca (IC).3 - 6

Apesar de a obesidade, definida como um índice de massa corporal (IMC) >30 kg/m2, é um preditor independente de IC incidente na população geral, há evidências de que o próprio sobrepeso (IMC 25-29 kg/m2) representa um aumento no risco de IC.7 - 10

Vários estudos mostram que medidas de adiposidade, tais como circunferência de cintura (CC), são melhores que medidas de adiposidade global, tais como peso e IMC, para se estimar o risco de DCV.11 - 16 A CC é independentemente associada à disfunção diastólica do ventrículo esquerdo (DDFVE), definida por parâmetros ecocardiográficos.17 Tanto a DDFVE quanto a obesidade são fatores comuns que contribuem para o aparecimento de insuficiência cardíaca com fenótipo de fração de ejeção preservada (ICFEP), e parecem ter uma ligação causal.17 - 19 Em um breve resumo, pacientes com IC pode ter fenótipos diferentes, de acordo com as características morfofuncionais da doença.20 Em resumo, os pacientes de IC são classificados de acordo com a função VE; aqueles com frações de ejeção VE menor ou igual a 40% se encaixam na categoria de insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção reduzida (ICFER), enquanto os pacientes com frações de ejeção maiores ou iguais a 50% são considerados portadores de ICFEP. De acordo com diretrizes do American College of Cardiology (Colégio Americano de Cardiologia) e da American Heart Association (Associação Americana do Coração)21 também existe um grupo de pacientes intermediários ou limítrofes, que têm frações de ejeção entre 41 e 49%, às vezes chamados de ICFEI. Além disso, um subconjunto de pacientes com frações de ejeção acima de 40%, com ICFEP que tiverem ICFER anteriormente é considerado clinicamente diferente daqueles com frações de ejeção persistentemente preservadas ou reduzidas. Esta análise concentrou-se apenas na ICFEP, e, especificamente, as características do fenótipo do portador de ICFEP “obeso, do sexo feminino e fadigado”.21

Uma revisão da literatura de todos os fenótipos clínicos de ICFEP de referência para o leitor é a realizada por Silverman.20 Independentemente do fenótipo biológico, a ICFEP é uma síndrome clínica heterogênea, que inclui mecanismos fisiopatológicos de cardiomiócitos, de matriz extracelular, vasculares e relacionados a comorbidade.22 Ela é caracterizadas pela redução do volume diastólico final, hipertrofia do ventrículo esquerdo, e aumento do volume atrial esquerdo e da pressão de enchimento do ventrículo esquerdo. Essas anormalidades fisiopatológicas estão associadas ao aumento da rigidez do ventrículo esquerdo, à diminuição do relaxamento do ventrículo esquerdo, à hipertrofia de cardiomiócitos, à fibrose miocárdica intersticial, e à redução de capilares intramiocárdicos.23 - 26

Outro fator importante envolvido no fenótipo de ICFEP é o sexo. A ICFEP afeta desproporcionalmente mais mulheres (razão de sexos de aproximadamente 2:1) que homens.27 , 28 A prevalência mais alta de ICFEP em mulheres idosas29 parece estar relacionada à perda de hormônios ovarianos, principalmente estrogênios, que ocorre após a menopausa.

Portanto, esta revisão explora dados pré-clínicos e clínicos sobre a relação entre sexo, “gordura”, incluindo mecanismos de disfunção cardíaca causada por obesidade, especificamente a DDFVE e a ICFEP, e os efeitos cardioprotetores do estrogênio no metabolismo de gordura nas mulheres.

Associação entre “gordura”, sexo e ICFEP: evidências clínicas

A IC é um problema grave cujo escopo tem aumentado. Apesar dos avanços terapêuticos recentes, a morbidade e a mortalidade após o aparecimento da IC ainda continuam significativas.30 Consequentemente, a prevenção da IC pela identificação das fases pré-clínicas da doença e gestão dos fatores de risco é uma prioridade. Considerando-se que 50 por cento de todos os pacientes com IC têm ICFEP,31 a fisiopatologia complexa dessa doença ainda não é completamente entendida, sem terapia específica disponível para melhorar os resultados para o paciente. Nesse contexto, vários estudos avaliaram a obesidade como um fator de risco para remodelamento do VE e ICFEP subsequente.32 - 34 Nesses estudos, a obesidade foi consistentemente associada à rigidez do VE e à disfunção diastólica, especialmente em mulheres.17 , 35

Um estudo comunitário clínico de 377 participantes, acima de 16 anos de idade, selecionados aleatoriamente avaliou a contribuição independente dos índices de adiposidade para as variações na velocidade transmitral (atrial) de inicial a final (E/A), conforme determinada pelo ecocardiograma. O principal objetivo foi esclarecer por que alguns estudo não conseguiram estabelecer uma contribuição da obesidade para a função diastólica do VE, enquanto outros demonstraram uma contribuição relativamente pequena. Para cada participante do estudo, foi determinada a relação independente entre adiposidade e funções das câmaras diastólica (E/A) ou sistólica (fração de ejeção do VE, FEVE), utilizando-se análise de regressão linear multivariada, com padronização para idade, gênero, aferições convencionais de pressão arterial diastólica ou sistólica, e ou o índice de massa do VE ou a espessura relativa da parede (calculada por ecocardiograma). A adiposidade central (CC) excessiva, mas o IMC não elevado, foi independentemente e inversamente correlacionada à E/A; os pesquisadores enfatizaram que a CC pode representar uma condição pré-clínica progressiva que contribui para a IC diastólica causada por obesidade.36 A CC só foi superada pela idade e se igualou à pressão arterial em magnitude do efeito sobre a E/A. Achados deste estudo também sugerem que, no nível populacional, a massa e a geometria do VE tem pouca ou nenhuma influência na patogênese das anormalidades diastólicas do VE causadas por obesidade.36 É interessante observar que não há relação entre CC e FEVE (disfunção sistólica), confirmando os achados de outros pesquisadores que identificaram a CC como fator de risco para ICFEP.7 , 9 , 17 , 37 - 43 Por último, é relevante observar que os dados relatados por esses autores foram restritos a mulheres, já que foi recrutada uma proporção limitada de participantes do sexo masculino.36 Dados adicionais do estudo clínico realizado por Canepa et al.,17 em que a amostra, para ambos os sexos, é parte do Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA - Estudo Longitudinal de Envelhecimento de Baltimore) propõem que uma possível explicação fisiopatológica para a associação entre adiposidade e resultados cardiovasculares piores é sua relação com a DDFVE. Eles identificaram que a adiposidade central estava fortemente associada à disfunção do VE, particularmente com deficiência do relaxamento do VE. Os pesquisadores também identificaram que o efeito da adiposidade central sobre a DDFVE foi independente da adiposidade geral e, surpreendentemente, isso era mais pronunciado em homens que em mulheres. O efeito específico do gênero do acúmulo central de gordura na DDFVE foi classificado de acordo com parâmetros ecocardiográficos. O estudo confirmou que os relatórios anteriores demonstrando correlação negativa entre os índices de adiposidade e a relação E/A; entretanto, os autores também identificaram que a E/A sozinha não era suficiente para diferenciar entre sujeitos com função diastólica normal ou anormal, e as velocidades de fluxo mitral também foram significativamente afetados pelo aumento de pré-carga, uma condição frequentemente encontrada em sujeitos obesos. Quando esses tecidos foram padronizados pela combinação de medidas histológicas por Doppler da velocidade do anel mitral, ou parâmetros e’ ou dinâmicos (E/A), identificou-se que a relação E/e’ estava correlacionada positivamente à CC. Portanto, esse estudo epidemiológico ofereceu mais evidências da ligação entre obesidade central (CC) e a prevalência e o desenvolvimento de DDFVE, e de que essa ligação é influenciada pelo sexo.17

Uma limitação de estudos transversais é que eles apresentam um instantâneo de um momento único no tempo e, portanto, não conseguem capturar mudanças que ocorrem ao longo do tempo. As relações complexas entre envelhecimento, sexo, adiposidade, e mecanismos ventriculares foram avaliadas em um grande estudo longitudinal realizado em um período de 4 anos, em 1.402 sujeitos, com 45 anos de idade ou mais, que foram selecionados aleatoriamente de uma população de uma comunidade.35 Identificou-se que o ganho de peso durante o período de 4 anos estava associado a aumentos significativos da rigidez diastólica do VE, em homens e mulheres, porém era mais pronunciado em mulheres, indicando que há uma diferença entre os sexos em relação à biologia da rigidez ventricular relacionada à idade. Além disso, a avaliação da obesidade central em mulheres pode ajudar a identificar um grupo em risco mais alto da incidência de ICFEP, que pode se beneficiar de tratamento preventivo.35 Finalmente, os resultados deste estudo longitudinal confirmaram os achados das investigações transversais relacionadas à relação positiva entre CC e medidas ecocardiográficas da disfunção diastólica (por exemplo, relação E/e’).

É importante considerar como as alterações do depósito de tecido adiposo podem influenciar a ligação entre obesidade e deficiências da função e remodelamento cardíaca, especialmente entre mulheres. Apesar de se acreditar que os hormônios sexuais femininos causam o acúmulo de gordura nas nádegas, coxas e quadris de mulheres, o que pode ser essencial para fins de reprodução normal, as mudanças na distribuição da gordura corporal relacionadas à menopausa pode explicar parcialmente o aumento do risco de doenças cardiovasculares e metabólicas durante os anos pós-menopausa.44 - 46 Em 2011, Wehr et al.,47 publicaram os resultados de um estudo longitudinal das diferenças específicas associadas ao sexo na relação entre o produto de acumulação lipídica, que é calculado a partir da CC, e a mortalidade cardiovascular, bem como a presença de diabetes tipo 2. O estudo incluiu 2.279 homens e 875 mulheres na pós-menopausa, com um acompanhamento médio aos 77 anos. Os níveis de produto de acumulação lipídica foram associados à mortalidade por IC congestiva em todas as mulheres na pós-menopausa, e com a mortalidade global em mulheres diabéticas na pós-menopausa, mas não em homens. Esses dados não só corroboram o conceito de que a redistribuição da gordura após a perda de estrogênio pode contribuir para o avanço de doenças cardiovasculares, mas também identifica um biomarcador de risco simples e acessível, o produto de acumulação lipídica, que poderia identificar mulheres na pós-menopausa com risco cardiovascular mais alto.47

Modalidades de tratamento para perda de peso: uma abordagem baseada em evidências para medir resultados em pacientes com ICFEP

Considerando a evidência clínica de interferência entre coração e “gordura”, em relação a ICFEP específica do sexo feminino, a redução do peso, ou a manutenção do peso corporal ideal é uma abordagem preventiva para mitigar alterações na estrutura e na função ventricular relacionadas à idade e à perda de estrogênio. Tratamentos essenciais para redução de peso incluem alterações nos hábitos alimentares passando para dietas com redução de caloria e gordura, aumento da atividade física ou exercício, e outras estratégias de modificação comportamental, tais como o automonitoramento (por exemplo, registro diário do consumo alimentar e da atividade física), e solução de problemas (por exemplo, identificação de barreiras e maneiras de superá-las). Além disso, a cirurgia bariátrica é outra estratégia eficiente para tratar pacientes gravemente obesos. Portanto, é importante fazer a revisão da literatura que aborda os efeitos de várias estratégias de perda de peso sobre os efeitos cardiovasculares em pacientes com DDFVE e ICFEP.

Estudos observacionais sugerem que pacientes com ICFEP que têm sobrepeso ou com obesidade de leve a moderada têm uma sobrevida mais longa do que os que têm peso normal.18 , 48 Entretanto, Kitzman et al.,49 relataram recentemente que 20 semanas de restrição calórica combinada com exercícios aeróbicos entre pacientes obesos mais velhos com ICFEP reduziram seu peso corporal e resultaram em melhorias na capacidade de exercício, definida pelo VO2pico. Além disso, a restrição calórica sozinha levou à diminuição da massa do VE e da espessura relativa da parede do VE, bem como deu um indício de melhorias na função diastólica, conforme o aumento de E/A observado nesse braço do tratamento, sem afetar a função cardíaca em repouso, ilustrado pela fração de ejeção ou pelo débito cardíaco derivado de Doppler.49 Relatou-se posteriormente que não foram observadas alterações em medidas de imagens por ressonância magnética (IRM) da gordura epicárdica ou pericárdica durante o tratamento, mas houve reduções significativas nos depósitos de gordura subcutânea das coxas e abdominal e gordura visceral, apenas no grupo que fez a dieta.49 Apesar de esses achados identificarem serem favoráveis à adoção de estratégias de redução de peso, juntamente com exercícios, para melhorar os prejuízos à capacidade de exercício e o consumo máximo de oxigênio associado à ICFEP entre pacientes obesos, eles também corroboram o conceito de que mecanismos extracardíacos estão envolvidos de maneira exclusiva na patogênese da ICFEP.50 , 51

Outra estratégia de redução de peso que leva à avaliação da ligação entre “gordura”, DDFVE e ICFEP é a cirurgia bariátrica. Na realidade, pacientes com obesidade mórbida normalmente apresentam características hemodinâmicas e morfométricas cardíacas, tais como, elevação da pré-carga e da pós-carga cardíaca e aumento da câmara do VE e dimensões da parede do VE, que contribuem para a rigidez miocárdica e deficiências no relaxamento miocárdico.52 Vários estudos clínicos52 - 55 e uma revisão sistemática com meta-análise56 relataram os benefícios da cirurgia bariátrica com perda de peso subsequente nas medidas ecocardiográficas e de IRM da estrutura do VE, incluindo reduções significativas da espessura da parede e da massa do VE, e da função diastólica. Junto com as melhorias da função diastólica, outros estudos identificaram que a grande perda de peso após a cirurgia bariátrica também resultou em mudanças favoráveis do metabolismo muscular57 e das características da elasticidade arterial.58 , 59

Ligação entre adiposidade regional específica cardíaca, DDFVE e ICFEP

Além da gordura periférica e da gordura total que estão ligadas à DDFVE, o possível papel da adiposidade específica da região cardíaca (por exemplo, depósitos de gordura pericárdica e epicárdica) não deve ser ignorado.60 As gorduras pericárdica e epicárdica, geralmente encontrada em pacientes obesos e com sobrepeso, são consideradas depósitos adiposos ectópicos que levam a um estado lipotóxico em proximidade ao músculo cardíaco e às artérias coronárias.61 , 62 Além disso, sabe-se que a síndrome metabólica, uma doença comum entre paciente obesos e com sobrepeso,63 está associada ao aumento do volume de tecido adiposo próximo ao coração,60 especialmente o acúmulo de gordura epicárdica,64 e isso está significativamente ligado a eventos cardiovasculares adversos,65 - 69 incluindo a ICFEP.61 , 70 , 71 A correlação direta entre esses depósitos locais de gordura e a DDFVE pode ser explicada, em parte, por processos parácrinos, pelos quais as citocinas pró-inflamatórias e outros mediadores prejudiciais (por exemplo, TNF-α e IL-6),72 chamados coletivamente de adipocinas, são liberados dos repositórios adiposos locais.61 , 72 - 74

A distinção entre os dois depósitos de gordura e sua respectiva ligação à DDFVE pode ser importante anatômica e bioquimicamente. Por exemplo, a gordura epicárdica está localizada entre a parede externa do músculo cardíaco e a camada visceral do pericárdio,64 e sua proximidade ao miocárdio é significativa, pois ambas as camadas de tecido compartilham da mesma microcirculação sanguínea, as artérias coronárias.64 Possíveis interações podem ser elicitadas quando adipócitos disfuncionais de depósitos de gordura cardíaca liberam adipocinas pró-inflamatórias para a microcirculação,37 que, por sua vez, interagem com cardiomiócitos e fibroblastos cardíacos. Essas células respondem independentemente às adipocinas que contribuem para o processo patológico da fibrose miocárdica,75 levando portanto à remodelamento miocárdica, por processos fibróticos e inflamação de baixo grau, que podem intensificar a hipertrofia do VE, rigidez da parede, e avanço da DDFVE.76 - 79 A gordura pericárdica, que pode ser chamada mais especificamente de gordura paracárdica ou gordura intratorácica,80 é a gordura depositada fora do pericárdio parietal. Esse depósito de gordura de origina do mesênquima torácico primitivo e é alimentado por fontes não coronárias. Embora já se tenha relatado que os aumentos no volume de gordura paracárdica na ICFEP levem à uma carga mecânica do tipo compressiva no miocárdio, o que afeta o enchimento do VE,81 também se observaram processos parácrinos também foram observados. A adiposidade pericárdica excessiva contém altos níveis de mediadores pró-inflamatórios que, quando liberados dos adipócitos, promovem uma rotação de colágeno, levando à rigidez miocárdica, lusitropismo prejudicado e subsequente DDFVE.82 Realmente, Konishi et al.,61 relataram que um volume alto de gordura pericárdica estava relativamente correlacionado a aumentos derivados de Doppler na pressão de enchimento, ou E/e’, em pacientes com ICFEP. Além disso, estudos documentaram um forte potencial de a adiposidade epicárdica estar associada com o mau prognóstico em pacientes com DDFVE e ICFEP obesos e com sobrepeso.71 , 83 - 85

Considerando a ligação entre depósitos de gordura cardíaca local e a saúde cardiovascular adversa, as estratégias de redução de peso devem ser fortemente consideradas no arsenal terapêutico para a gestão de pacientes com DDFVE obesos. É interessante observar que em mulheres na pós-menopausa com ICFEP, Brinkley et al.,86 demonstraram que a restrição calórica, os exercícios aeróbicos ou uma combinação de tratamentos reduziram significativamente o peso corporal e a gordura pericárdica, e que as mudanças na gordura pericárdica estavam inversamente correlacionadas ao condicionamento cardiorrespiratório definido por VO2max. Com certeza, terapias futuras que têm como alvo processos inflamatórios de baixo grau resultantes de depósitos de gordura epicárdica e pericárdica também poderiam limitar o avanço da DDFVE.

Ligação entre estrogênio - risco cardiovascular induzido por gordura

A alta prevalência da ICFEP entre mulheres mais velhas em comparação a homens mais velhos com IC é bem aceita.27 , 28 O papel que as diferenças na distribuição de adipócitos entre homens e mulheres pode ter em relação a esses diferenciais específicos do sexo na prevalência da IC é novo e ainda em avaliação. Realmente, as mulheres têm mais gordura corporal que os homens, mas, diferentemente das consequências metabólicas adversas da obesidade central que é típica de homens, a distribuição subcutânea da gordura corporal gluteofemoral ou em formato de pera de muitas mulheres está associada a um risco cardiometabólico mais baixo.87 , 88 Entretanto, com o avanço da idade, há uma mudança geral e expansão da gordura, do compartimento subcutâneo para o visceral.87 - 89 Em homens idosos, isso significa o aumento da adiposidade visceral abdominal, enquanto em mulheres idosas isso envolve uma redistribuição de gordura do compartimento subcutâneo gluteofemoral para o compartimento visceral-abdominal.87 - 89 Em ambos os casos, o risco de doença cardiovascular aumenta com a expansão de gordura visceral do compartimento abdominal relacionado à idade.89 , 90

Como apontado na introdução, a perda de hormônios gonadais em mulheres mais velhas parece representar um componente associado ao aumento do risco de desenvolvimento de ICFEP. Como as mulheres têm menor possibilidade de desenvolver DCV antes da menopausa,91 a produção de estrogênio ovariano parece proteger contra a IC.92 , 93 De forma consistente, há vários relatórios que confirma os efeitos benéficos do estrogênio no sistema cardiovascular.94 - 96

Para entender o papel específico dos hormônios gonadais na expansão da gordura visceral relacionada à idade em mulheres, e, ao mesmo tempo, sua possível influência na função diastólica, é necessário realizar uma análise breve dos hormônios gonadais, particularmente os estrogênios e seus receptores primeiramente. Os três estrogênios que ocorrem naturalmente em mulheres são a estrona (E1), o estradiol (E2), e o estriol (E3). Uma quarta forma de estrogênio, o estetrol (E4), é produzida apenas durante a gravidez. Todas essas formas diferentes de estrogênio são sintetizadas a partir de andrógenos.97 Para simplificar, será utilizado o termo estrogênio incluindo todas as formas.

O estrogênio se liga a vários receptores, incluindo os receptores de estrogênio nuclear clássicos (RE), REα, e REβ, e um receptor acoplado à proteína G, RAPG.98 Os RE sinalizam não só por meio da regulação de transcrição gênica “clássica”, com também pela ativação de um caminho de sinalização “não nuclear”.94 , 99 O acúmulo de achados já foi bem descrito e analisado na literatura relacionada aos papéis desencadeados pelos RE na manutenção da homeostase do sistema cardiovascular.99 - 101

O estrogênio regula diretamente as distribuições de adiposidade por meio de receptores de estrogênio. No estado pré-menopausa, a gordura subcutânea tem relativamente mais receptores de estrogênio e progesterona que receptores de andrógenos, enquanto a gordura visceral tem níveis mais altos de receptores de andrógenos.102 Com a menopausa, a queda do estrogênio faz com que os receptores de estrogênio na gordura subcutânea sejam inativados, enquanto os receptores de andrógenos na gordura visceral se torna relativamente ativada, contribuindo, portanto para a relação inversa entre níveis de estrogênio e gordura visceral.103 , 104 Da mesma forma, em modelos de roedores com déficit de estrogênio induzido por ovariectomia, o aumento do peso corporal se deve principalmente pelo aumento de gordura visceral.105 A proteção estrogênica pode ser vista na administração sistêmica de estrogênio em modelos ovariectomizados em que a distribuição de gordura corporal reflete à das contrapartidas com gônadas intactas.106

Os papéis específicos podem compensar os receptores de esteroides REα e REβ no contexto da gordura um ao outro. Em um estudo recente de Zidon et al.,107 identificou-se que ratos KO comα RE de gônadas intactas são 25% mais pesados, com redução do gasto energético em comparação com o tipo selvagem com gônadas intactas e os ratos KO com ERβ.107 Além disso, após a ovariectomia, os ratos αKO não apresentaram aumento de peso corporal ou apresentaram resistência à insulina mais pronunciada, enquanto os do tipo selvagem e os βKO apresentaram, sugerido que a perda de sinal por REα facilita a disfunção metabólica induzida por ovariectomia. Esses novos dados sugerem ainda que após a deficiência de estrogênio, os REβ podem mediar benefícios metabólicos de proteção.107 Isso contradiz relatórios pré-clínicos anteriores demonstrando que dois RE clássicos no tecido adiposo regulam a gordura reciprocamente.108 - 110 Apesar dessa discrepância, a ligação entre os polimorfismos na estrutura dos RE clássicos e no aumento de risco em mulheres na pós-menopausa corroboram o papel importante de isoformas de ER na regulação da adiposidade, na disfunção metabólica, e no risco cardiovascular.111 - 113

Adipocinas derivadas da gordura e funções no risco de doenças cardiovasculares

A principal função da gordura marrom, localizada principalmente ao redor do pescoço e grandes vasos sanguíneos do tórax, é gerar calor “desacoplando” a cadeia de fosforilação oxidativa dentro das mitocôndrias.114 A gordura visceral branca (gordura abdominal) está envolvida principalmente em uma rede multidirecional de sinalização autócrina, parácrina e endócrina que interconecta órgãos e tecidos. É a gordura branca que participa principalmente da patogênese de doenças metabólicas, tais como o diabetes mellitus tipo 2, resistência à insulina, hipertensão, doença cardíaca coronária, acidente vascular cerebral, e IC.17 , 115 , 116 Atualmente, está bem estabelecido que o tecido adiposo é um órgão endócrino ativo que secreta fatores bioativos heterogêneos chamados adipocinas115 incluindo citocinas e quimiocinas, fatores vasoativos e de coagulação, reguladores do metabolismo lipoproteico, e proteínas como adiponectina e leptina.115

Na obesidade, o aumento da massa de tecido adiposo tem sido associada a uma desregulação da secreção de adipocinas e à inflamação de tecido relacionada, o que representa uma ligação patogênica entre obesidade e o desenvolvimento de doenças cardiometabólicas.117 Em indivíduos obesos, o tecido adiposo é infiltrado por macrófagos ativados e vários outros tipos de células inflamatórias, levando ao aumento da produção de adipocinas pró-inflamatórias, tais como TNF-α, IL-6, proteína quimiotática de monócitos (MCP-1), resistina, leptina, lipocalina-2, proteína transportadora de ácidos graxos de adipócitos (A-FABP), inibidor do ativador de plasminogênio tipo 1.116 Esses fatores inflamatórios são componentes-chave do “eixo adipo-cardiovascular”, que media as interferências entre tecido adiposo e o sistema cardiovascular.

Entre os vários depósitos adiposos, o tecido adiposo perivascular tem uma contribuição importante na inflamação vascular, devido à sua proximidade à parede do vaso sanguíneo e suas propriedades pró-inflamatórias pronunciadas. Citocinas/adipocinas pró-inflamatórias liberadas de outros depósitos de tecido adiposo, tais como a gordura abdominal subcutânea, podem contribuir ainda mais para a inflamação vascular, por meio de suas ações endócrinas.116 Esses achados explicam, em parte, porque a CC pode ser considerada um biomarcador substituto do risco de DCV.

A adiponectina é uma das adipocinas mais abundante secretadas pelos adipócitos, representando 0,01% do teor de proteína plasmática em seres humanos118 A produção de adiponectina a partir de adipócitos brancos, que tem efeitos benéficos na sensibilidade à insulina e na função cardiovascular, é notadamente reduzida em indivíduos obesos.116 , 119 , 120 Estudos epidemiológicos demonstram que níveis de adiponectina circulante baixos, especialmente a forma com alto peso molecular, é um fator de risco de diabetes tipo 2, hipertensão, aterosclerose e infarto do miocárdio.116

Adiponectina e receptores de adiponectina

A relação entre obesidade e DDFVE pode estar relacionada à adiponectina e aos receptores de adiponectina. A adiponectina é composta de 247 resíduos de aminoácidos, organizados em uma região hipervariável N-terminal seguidos de um domínio colagenoso conservado de 22 repetições de Gly-Xaa-Yaa e um domínio globular C -terminal tipo C1q.119 A adiponectina está presente no plasma humano e de ratos nas três principais formas oligoméricas.119 , 121 , 122 A forma monomérica nunca foi detectada em condições nativas. A unidade básica de adiponectina oligomérica é um homotrímero chamado adiponectina de baixo peso molecular (LMW).119 , 123 , 124 Duas subunidades do trímero de adiponectina estão conectadas por uma ligação dissulfeto via resíduos de cisteína do domínio do tipo colágeno, que forma um hexâmero chamado adiponectina de médio peso molecular (MMW). O hexâmero fornece a base para a formação da adiponectina de alto peso molecular (HMW) em forma de buquê, composta de 12-18 hexâmeros.

É necessário realizar modificações pós-translação na proteína adiponectina para a organização intracelular do complexo oligomérico de HMW nos adipócitos.125 Várias formas de adiponectina agem em alvos diferentes e têm funções biológicas distintas.119

Os dois principais receptores de adiponectina (AdipoRs), AdipoR1 e AdipoR2, são estruturalmente e funcionalmente diferentes dos receptores acoplados à proteína G clássicos.126 O AdipoR1 é expresso em todos os locais, enquanto o AdipoR2 é expresso mais abundantemente no fígado.126 Tanto o AdipoR1 quanto o AdipoR2 são expressos em células cardíacas,127 mas a função exata desses dois receptores no stress antioxidativo/nitrativo e nas ações anti-inflamatórias nos cardiomiócitos ainda não está clara.

Embora os adipócitos tenham a principal contribuição para a adiponectina plasmática, a adiponectina também é expressa em cardiomiócitos,127 e a adiponectina derivada de cardiomiócitos é biologicamente ativa na proteção das células contra lesões isquêmicas via ativação parácrina/autócrina dos AdipoRs em ratos.128 Em pacientes com cardiomiopatia dilatada, a expressão da adiponectina cardíaca é diminuída.129

Adiponectina e DDFVE

Além dos AdipoRs, sugere-se também que a T-caderina também seja um receptor possível para a adiponectina130 e ele é altamente expresso no coração, no músculo liso, e no endotélio, representando o principal alvo da adiponectina no sistema cardiovascular.131 , 132 A T-caderina é ancorada na superfície da célula pelo glicosilfosfatidilinositol e desempenha um papel essencial na proteção cardíaca induzida por adiponectina em ratos133 agindo como um receptor de ligação de adiponectina fisiológico que permite a associação dessa adipocina ao tecido cardíaco.133

Como baixos níveis de adiponectina foram associados a complicações cardiometabólicas relacionadas à obesidade, sua função na manutenção da saúde cardíaca não deve ser ignorada120 , 134 , 135 Dados pré-clínicos mostram que a adiponectina pode atenuar ou evitar o avanço da DDFVE para ICFEP.120 , 136 , 137 Em um modelo com ratos de ICFEP induzida por aldosterona, Sam et al.,137 demonstraram que a falta de adiponectina estava associada ao aumento da pressão arterial sistólica, remodelamento do VE, disfunção diastólica, e congestão pulmonar. Já a hiperadiponectinemia em ratos transgênicos com superexpressão de adiponectina, relatada Tanaka et al.,120 amenizou a hipertrofia do VE induzida por aldosterona, a disfunção diastólica, e a congestão pulmonar, independentemente das mudanças na pressão arterial. A relação de enchimento inicial e descida inicial do anel mitral, ou E/e’, que foi aumentada nos ratos com ICFEP induzida por aldosterona e indica pressões de enchimento elevadas,137 foi significativamente atenuada em ratos transgênicos por adiponectina. Tanaka et al.,120 também detectaram que a superexpressão de adiponectina diminuiu o stress oxidativo e o manejo de cálcio, preservando a fosforilação de fosfolambano dependente da proteína quinase A (PKA). Além disso, a reposição de adiponectina em ratos knockout atenuou os índices de pseudonormalização transmitral de Doppler, que indicam conformidade com VE deficiente.120 Considerados em conjunto, esses achados pré-clínicos sugerem que a adiponectina possa ter um potencial terapêutico no controle da DDFVE e da ICFEP, por meio de ação direta no coração.

A observação deste estudo de que a adiponectina circulante não estava associada ao encurtamento fracional do VE é consistente com a literatura existente que sugere que a adiponectina age principalmente como um inibidor de hipertrofia cardíaca.

Estudos clínicos também corroboram a hipótese de associação entre adiponectina e função e estrutura cardíacas.129 , 138 Em um estudo coorte em uma comunidade, McMannus et al.,139 demonstraram que níveis plasmáticos relativamente mais altos de adiponectina associados à redução da massa do VE, sugerindo um efeito de proteção cardíaca. Existem dados clínicos adicionais que tratam das funções de proteção cardíacas da adiponectina no coração.140 - 142 Por exemplo, Francisco et al.,143 realizou uma revisão abrangente da relevância da sinalização por adiponectina na prevenção de disfunção diastólica relacionada à obesidade com ênfase em sua função de limitar a hipertrofia miocárdica, a fibrose cardíaca, o stress oxidativo e nitrativo, a aterosclerose, e a inflamação.

Como existem vários estudos mostrando o papel modulador da adiponectina na manutenção da função diastólica, vale mencionar que outros pesquisadores não relataram nenhuma relação com DDFVE associada à gordura. Sawada et al.,144 identificaram que, enquanto os níveis de adiponectina diminuíram significativamente com o aumento de adiposidade visceral na população em geral, a associação entre adiponectina e função diastólica não se deu independentemente da gordura. Em outras palavras, a diminuição dos níveis de adiponectina circulante não parece ter tido um papel central na associação entre adiposidade visceral e DDFVE. Como esse estudo foi realizado em uma população não portadora ou com grau 1 de DDFVE, os sujeitos com DDFVE mais moderada não foram incluídos. Esses autores sugeriram que um estudo de larga escala, incluindo pacientes com DDFVE moderada ou grave é necessário, para confirmar os achados.

Diferenças de sexo, adiponectina e função cardíaca

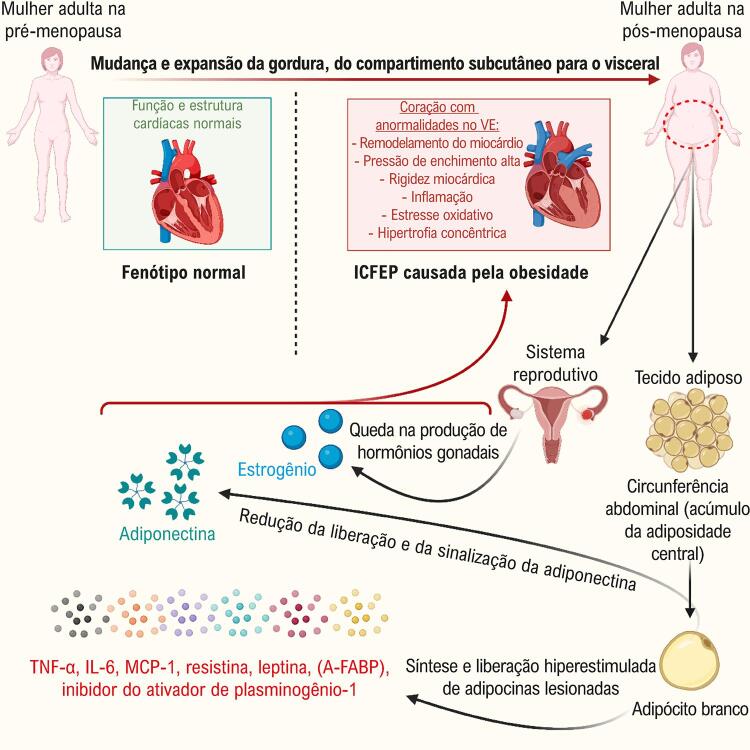

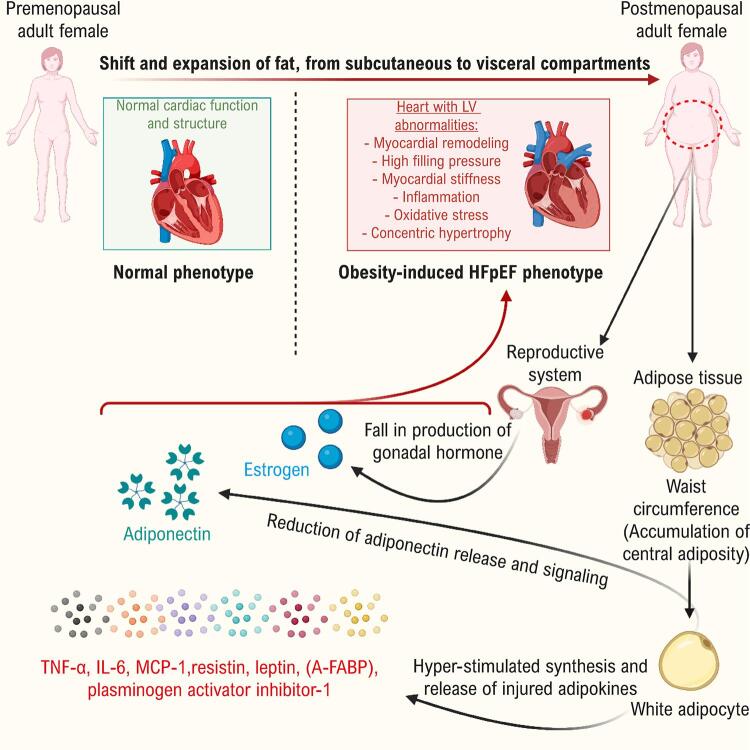

Não está claro se há diferenças entre os sexos nos efeitos da adiponectina na função e na estrutura cardíaca. Fontes-Carvalho et al.,145 relataram dados de um estudo populacional envolvendo indivíduos com 45 anos de idade ou mais sobre as associações dos níveis de leptina e adiponectina e a função diastólica do VE. Esses pesquisadores encontraram diferenças significativas entre os sexos para os níveis de leptina e adiponectina, e suas relações com a função diastólica. Níveis relativamente mais altos de leptina, associados a função diastólica piorada, foram relatados, especialmente entre mulheres, independentemente de idade ou hipertensão. É interessante notar que a adiponectina foi correlacionada a parâmetros da função diastólica.145 Ainda assim, é plausível postular um efeito específico do sexo para alterações de adiponectina na estrutura e na função miocárdica, já que as mulheres têm níveis de adiponectina sistêmica significativamente mais altos.146 Em dois estudos pequenos envolvendo pacientes que passam por angiografia coronária147 ou com IC,142 a redução dos níveis de adiponectina foi associada à piora da função diastólica. A Figura 1 resume os principais mecanismos envolvidos na perda de estrogênio e na obesidade no desenvolvimento de DDFVE e ICFEP.

Figura 1. – Diagrama esquemático mostrando o envolvimento de perda de estrogênio e obesidade na ICFEP. Uma expansão e mudança de gordura subcutânea para visceral ocorre em mulheres após a menopausa. A obesidade abdominal, definida pelo aumento da circunferência de cintura, é um grande fator de risco de desenvolvimento de ICFEP, que pode envolver uma tendência de aumento na síntese e na liberação de adipocinas, incluindo TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, resistina, leptina, lipocalina-2, e inibidor do ativador de plasminogênio-1. Essas adipocinas têm funções críticas em inflamação cardíaca, stress oxidativo, e disfunção metabólica. Por outro lado, a produção de adiponectina de adipócitos brancos, que tem efeitos benéficos na sensibilidade à insulina e função cardiovascular, é notadamente reduzida em indivíduos obesos. Anormalidades em adipocinas, além da perda de estrogênio, podem participar do desenvolvimento de ICFEP, induzindo a inflamação cardíaca e o stress oxidativo, e levando à hipertrofia cardíaca concêntrica, Remodelamento, rigidez, e disfunção diastólica. ICFEP, insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção preservada; TNF-α, fator de necrose tumoral alfa; IL-6, interleucina 6; MCP-1, proteína quimiotática de monócitos; A-FABP, proteína transportadora de ácidos graxos de adipócitos.

Conclusão

Em resumo, o estrogênio desempenha um papel essencial na regulação do peso corporal e da gordura corporal, e esse papel também pode ser a proteção do coração pré-menopausa da disfunção do VE. Em comparação com homens da mesma idade, as mulheres na pós-menopausa apresentaram aumento da rigidez ventricular e arterial, e têm mais probabilidade de desenvolver DDFVE e ICFEP subsequentes. Os níveis mais baixos de estrogênio depois da menopausa estão envolvidos nas mudanças da distribuição e no teor de gordura corporal, um fator que aumenta a incidência de DCV. Esta análise coletou as evidências recentes e esclareceu as rotas moleculares pelas quais o estrogênio desencadeia esses efeitos, e apresentou novas direções para pesquisa futura nessa área interessante do envelhecimento cardíaco específico dos sexos e da disfunção diastólica, que é um prenúncio de ICFEP.

Funding Statement

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo foi financiado por National Institute on Aging of the National Institute of Health to Leanne Groban (AG033727; AG061588) e parcialmente financiado pelo Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) to Gisele Zapata-Sudo and Allan Kardec Nogueira de Alencar.

Vinculação acadêmica

Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este artigo não contém estudos com humanos ou animais realizados por nenhum dos autores.

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo foi financiado por National Institute on Aging of the National Institute of Health to Leanne Groban (AG033727; AG061588) e parcialmente financiado pelo Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) to Gisele Zapata-Sudo and Allan Kardec Nogueira de Alencar.

Referências

- 1.Collaborators GBDO, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Guenancia C, Lefebvre A, Cardinale D, Yu AF, Ladoire S, Ghiringhelli F, et al. Obesity As a Risk Factor for Anthracyclines and Trastuzumab Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3157-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Alpert MA, Lavie CJ, Agrawal H, Aggarwal KB, Kumar SA. Obesity and heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Translat Res. 2014;164(4):345-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Lee HJ, Kim HL, Lim WH, Seo JB, Kim SH, Zo JH, et al. Subclinical alterations in left ventricular structure and function according to obesity and metabolic health status. PloS one. 2019;14(9):e0222118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Russo C, Sera F, Jin Z, Palmieri V, Homma S, Rundek T, et al. Abdominal adiposity, general obesity, and subclinical systolic dysfunction in the elderly: A population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J Fail.2016;18(5):537-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Yang H, Huynh QL, Venn AJ, Dwyer T, Marwick TH. Associations of childhood and adult obesity with left ventricular structure and function. Int J Obes. 2017;41(4):560-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Sacco RL, et al. Effect of obesity and overweight on left ventricular diastolic function: a community-based study in an elderly cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(12):1368-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rayner JJ, Banerjee R, Holloway CJ, Lewis AJM, Peterzan MA, Francis JM, et al. The relative contribution of metabolic and structural abnormalities to diastolic dysfunction in obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(3):441-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lee SL, Daimon M, Di Tullio MR, Homma S, Nakao T, Kawata T, et al. Relationship of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function to Obesity and Overweight in a Japanese Population With Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Circ J. 2016;80(9):1951-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pandey A, Patel KV, Vaduganathan M, Sarma S, Haykowsky MJ, Berry JD, et al. Physical Activity, Fitness, and Obesity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(12):975-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bigaard J, Frederiksen K, Tjonneland A, Thomsen BL, Overvad K, Heitmann BL, et al. Waist circumference and body composition in relation to all-cause mortality in middle-aged men and women. Int J Obes. 2005;29(7):778-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ashwell M, Hsieh SD. Six reasons why the waist-to-height ratio is a rapid and effective global indicator for health risks of obesity and how its use could simplify the international public health message on obesity. Int Nat Food Sci Nutr. 2005;56(5):303-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ho SY, Lam TH, Janus ED, Hong Kong Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study Steering C. Waist to stature ratio is more strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors than other simple anthropometric indices. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(10):683-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(3):379-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Wei M, Gaskill SP, Haffner SM, Stern MP. Waist circumference as the best predictor of noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) compared to body mass index, waist/hip ratio and other anthropometric measurements in Mexican Americans--a 7-year prospective study. Obes Res. 1997;5(1):16-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Welborn TA, Dhaliwal SS. Preferred clinical measures of central obesity for predicting mortality. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(12):1373-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Canepa M, Strait JB, Abramov D, Milaneschi Y, AlGhatrif M, Moni M, et al. Contribution of central adiposity to left ventricular diastolic function (from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging). Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(8):1171-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Haass M, Kitzman DW, Anand IS, Miller A, Zile MR, Massie BM, et al. Body mass index and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (I-PRESERVE) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):324-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ho JE, Lyass A, Lee DS, Vasan RS, Kannel WB, Larson MG, et al. Predictors of new-onset heart failure: differences in preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(2):279-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Silverman DN, Shah SJ. Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF): the Phenotype-Guided Approach. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2019;21(4):20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lam CSP, Chandramouli C. Fat, Female, Fatigued: Features of the Obese HFpEF Phenotype. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(8):710-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lewis GA, Schelbert EB, Williams SG, Cunnington C, Ahmed F, McDonagh TA, et al. Biological Phenotypes of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(17):2186-200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Mohammed SF, Borlaug BA, Roger VL, Mirzoyev SA, Rodeheffer RJ, Chirinos JA, et al. Comorbidity and ventricular and vascular structure and function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(6):710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Bursi F, Borlaug BA, Ommen SR, et al. Cardiac structure and ventricular-vascular function in persons with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation. 2007;115(15):1982-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Zile MR, Gottdiener JS, Hetzel SJ, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, et al. Prevalence and significance of alterations in cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2011;124(23):2491-501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure--abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1953-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Maslov PZ, Kim JK, Argulian E, Ahmadi A, Narula N, Singh M, et al. Is Cardiac Diastolic Dysfunction a Part of Post-Menopausal Syndrome? JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(3):192-203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pandey A, Omar W, Ayers C, LaMonte M, Klein L, Allen NB, et al. Sex and Race Differences in Lifetime Risk of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2018;137(17):1814-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Upadhya B, Kitzman DW. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Older Adults. Heart Fail Clin. 2017;13(3):485-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(8):768-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Alpert MA, Karthikeyan K, Abdullah O, Ghadban R. Obesity and Cardiac Remodeling in Adults: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61(2):114-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ferron AJT, Francisqueti FV, Minatel IO, Silva C, Bazan SGZ, Kitawara KAH, et al. Association between Cardiac Remodeling and Metabolic Alteration in an Experimental Model of Obesity Induced by Western Diet. Nutrients. 2018;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Antonini-Canterin F, Di Nora C, Poli S, Sparacino L, Cosei I, Ravasel A, et al. Obesity, Cardiac Remodeling, and Metabolic Profile: Validation of a New Simple Index beyond Body Mass Index. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2018;28(1):18-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wohlfahrt P, Redfield MM, Lopez-Jimenez F, Melenovsky V, Kane GC, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. Impact of general and central adiposity on ventricular-arterial aging in women and men. JACC Heart failure. 2014;2(5):489-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Libhaber CD, Norton GR, Majane OH, Libhaber E, Essop MR, Brooksbank R, et al. Contribution of central and general adiposity to abnormal left ventricular diastolic function in a community sample with a high prevalence of obesity. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(11):1527-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Fuster JJ, Ouchi N, Gokce N, Walsh K. Obesity-Induced Changes in Adipose Tissue Microenvironment and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. 2016;118(11):1786-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Tong D, French KM, Villalobos E, Kim SY, et al. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature. 2019;568(7752):351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Chirinos JA, Zamani P. The Nitrate-Nitrite-NO Pathway and Its Implications for Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2016;13(1):47-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Alvarez P, Briasoulis A. Immune Modulation in Heart Failure: the Promise of Novel Biologics. Current treatment. Options Cardiovasc Med. 2018 2018;20(3):26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Hulsmans M, Sager HB, Roh JD, Valero-Munoz M, Houstis NE, Iwamoto Y, et al. Cardiac macrophages promote diastolic dysfunction. J Exper Med.. 2018;215(2):423-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Van Tassell BW, Trankle CR, Canada JM, Carbone S, Buckley L, Kadariya D, et al. IL-1 Blockade in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(8):e005036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Van Tassell BW, Buckley LF, Carbone S, Trankle CR, Canada JM, Dixon DL, et al. Interleukin-1 blockade in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the Diastolic Heart Failure Anakinra Response Trial 2 (D-HART2). Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(9):626-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Garaulet M, Perez-Llamas F, Baraza JC, Garcia-Prieto MD, Fardy PS, Tebar FJ, et al. Body fat distribution in pre-and post-menopausal women: metabolic and anthropometric variables. J Nutr Health Aging. 2002;6(2):123-6. [PubMed]

- 45.Zamboni M, Armellini F, Milani MP, De Marchi M, Todesco T, Robbi R, et al. Body fat distribution in pre- and post-menopausal women: metabolic and anthropometric variables and their inter-relationships. Int In and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. Int J Obes.1992;16(7):495-504. [PubMed]

- 46.Toth MJ, Tchernof A, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Menopause-related changes in body fat distribution. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;904:502-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Wehr E, Pilz S, Boehm BO, Marz W, Obermayer-Pietsch B. The lipid accumulation product is associated with increased mortality in normal weight postmenopausal women. Obesity. 2011;19(9):1873-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Joyce E, Lala A, Stevens SR, Cooper LB, AbouEzzeddine OF, Groarke JD, et al. Prevalence, Profile, and Prognosis of Severe Obesity in Contemporary Hospitalized Heart Failure Trial Populations. JACC Heart failure. 2016;4(12):923-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kitzman DW, Brubaker P, Morgan T, Haykowsky M, Hundley G, Kraus WE, et al. Effect of Caloric Restriction or Aerobic Exercise Training on Peak Oxygen Consumption and Quality of Life in Obese Older Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(1):36-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Herrington DM, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Hundley WG, et al. Effect of endurance exercise training on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(7):584-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(2):120-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Shin SH, Lee YJ, Heo YS, Park SD, Kwon SW, Woo SI, et al. Beneficial Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Cardiac Structure and Function in Obesity. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):620-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Aggarwal R, Harling L, Efthimiou E, Darzi A, Athanasiou T, Ashrafian H. The Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Cardiac Structure and Function: a Systematic Review of Cardiac Imaging Outcomes. Obes Surg. 2016;26(5):1030-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Karason K, Wallentin I, Larsson B, Sjostrom L. Effects of obesity and weight loss on left ventricular mass and relative wall thickness: survey and intervention study. BMJ. 1997;315(7113):912-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Jhaveri RR, Pond KK, Hauser TH, Kissinger KV, Goepfert L, Schneider B, et al. Cardiac remodeling after substantial weight loss: a prospective cardiac magnetic resonance study after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(6):648-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Cuspidi C, Rescaldani M, Tadic M, Sala C, Grassi G. Effects of bariatric surgery on cardiac structure and function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(2):146-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Leichman JG, Wilson EB, Scarborough T, Aguilar D, Miller CC, 3rd, Yu S, et al. Dramatic reversal of derangements in muscle metabolism and left ventricular function after bariatric surgery. Am J Med. 2008;121(11):966-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Ikonomidis I, Mazarakis A, Papadopoulos C, Patsouras N, Kalfarentzos F, Lekakis J, et al. Weight loss after bariatric surgery improves aortic elastic properties and left ventricular function in individuals with morbid obesity: a 3-year follow-up study. J Hypert.2007;25(2):439-47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Iancu ME, Copaescu C, Serban M, Ginghina C. Favorable changes in arterial elasticity, left ventricular mass, and diastolic function after significant weight loss following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in obese individuals. Obes Surg. 2014;24(3):364-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Nyman K, Graner M, Pentikainen MO, Lundbom J, Hakkarainen A, Siren R, et al. Cardiac steatosis and left ventricular function in men with metabolic syndrome. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Konishi M, Sugiyama S, Sugamura K, Nozaki T, Matsubara J, Akiyama E, et al. Accumulation of pericardial fat correlates with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with normal ejection fraction. J Cardiol. 2012;59(3):344-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Assael F, Vecci E, Tiberti C, Zappaterreno A, et al. Echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue is related to anthropometric and clinical parameters of metabolic syndrome: a new indicator of cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(11):5163-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Morelli NR, Scavuzzi BM, Miglioranza L, Lozovoy MAB, Simao ANC, Dichi I. Metabolic syndrome components are associated with oxidative stress in overweight and obese patients. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2018;62(3):309-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Iacobellis G. Epicardial and pericardial fat: close, but very different. Obesity. 2009;17(4):625; author reply 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Ding J, Hsu FC, Harris TB, Liu Y, Kritchevsky SB, Szklo M, et al. The association of pericardial fat with incident coronary heart disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):499-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Tamarappoo B, Dey D, Shmilovich H, Nakazato R, Gransar H, Cheng VY, et al. Increased pericardial fat volume measured from noncontrast CT predicts myocardial ischemia by SPECT. JACC Cardiovasc Imag. 2010;3(11):1104-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Aslanabadi N, Salehi R, Javadrashid A, Tarzamni M, Khodadad B, Enamzadeh E, et al. Epicardial and pericardial fat volume correlate with the severity of coronary artery stenosis. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2014;6(4):235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Cheng VY, Dey D, Tamarappoo B, Nakazato R, Gransar H, Miranda-Peats R, et al. Pericardial fat burden on ECG-gated noncontrast CT in asymptomatic patients who subsequently experience adverse cardiovascular events. JACC Cardiovasc Imag 2010;3(4):352-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Mahabadi AA, Berg MH, Lehmann N, Kalsch H, Bauer M, Kara K, et al. Association of epicardial fat with cardiovascular risk factors and incident myocardial infarction in the general population: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(13):1388-95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Alonso-Gomez AM, Tojal Sierra L, Fortuny Frau E, Goicolea Guemez L, Aboitiz Uribarri A, Portillo MP, et al. Diastolic dysfunction and exercise capacity in patients with metabolic syndrome and overweight/obesity. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;22:67-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Haykowsky MJ, Nicklas BJ, Brubaker PH, Hundley WG, Brinkley TE, Upadhya B, et al. Regional Adipose Distribution and its Relationship to Exercise Intolerance in Older Obese Patients Who Have Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart failure. 2018;6(8):640-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, Mannion JD, Diehl JT, Arafat H, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108(20):2460-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Sacks HS, Fain JN. Human epicardial adipose tissue: a review. Am Heart J. 2007;153(6):907-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Iacobellis G, Corradi D, Sharma AM. Epicardial adipose tissue: anatomic, biomolecular and clinical relationships with the heart. Nature clinical practice Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2(10):536-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Schram K, Sweeney G. Implications of myocardial matrix remodeling by adipokines in obesity-related heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18(6):199-205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Packer M. Epicardial Adipose Tissue May Mediate Deleterious Effects of Obesity and Inflammation on the Myocardium. JJ Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2360-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Patel VB, Basu R, Oudit GY. ACE2/Ang 1-7 axis: A critical regulator of epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in obesity. Adipocyte. 2016;5(3):306-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Patel VB, Mori J, McLean BA, Basu R, Das SK, Ramprasath T, et al. ACE2 Deficiency Worsens Epicardial Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Cardiac Dysfunction in Response to Diet-Induced Obesity. Diabetes. 2016;65(1):85-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Wu CK, Tsai HY, Su MM, Wu YF, Hwang JJ, Lin JL, et al. Evolutional change in epicardial fat and its correlation with myocardial diffuse fibrosis in heart failure patients. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(6):1421-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Lee JJ, Yin X, Hoffmann U, Fox CS, Benjamin EJ. Relation of Pericardial Fat, Intrathoracic Fat, and Abdominal Visceral Fat With Incident Atrial Fibrillation (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(10):1486-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Fox CS, Gona P, Hoffmann U, Porter SA, Salton CJ, Massaro JM, et al. Pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and measures of left ventricular structure and function: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119(12):1586-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Mak GJ, Ledwidge MT, Watson CJ, Phelan DM, Dawkins IR, Murphy NF, et al. Natural history of markers of collagen turnover in patients with early diastolic dysfunction and impact of eplerenone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(18):1674-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.van Woerden G, Gorter TM, Westenbrink BD, Willems TP, van Veldhuisen DJ, Rienstra M. Epicardial fat in heart failure patients with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(11):1559-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Evidence Supporting the Existence of a Distinct Obese Phenotype of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2017;136(1):6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Cavalcante JL, Tamarappoo BK, Hachamovitch R, Kwon DH, Alraies MC, Halliburton S, et al. Association of epicardial fat, hypertension, subclinical coronary artery disease, and metabolic syndrome with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(12):1793-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Brinkley TE, Ding J, Carr JJ, Nicklas BJ. Pericardial fat loss in postmenopausal women under conditions of equal energy deficit. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(5):808-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Karastergiou K, Smith SR, Greenberg AS, Fried SK. Sex differences in human adipose tissues - the biology of pear shape. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Manolopoulos KN, Karpe F, Frayn KN. Gluteofemoral body fat as a determinant of metabolic health. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(6):949-59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Frank AP, de Souza Santos R, Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Determinants of body fat distribution in humans may provide insight about obesity-related health risks. J Lipid Res. 2019;60(10):1710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Mancuso P, Bouchard B. The Impact of Aging on Adipose Function and Adipokine Synthesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Lobo RA, Davis SR, De Villiers TJ, Gompel A, Henderson VW, Hodis HN, et al. Prevention of diseases after menopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(5):540-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Borlaug BA, Rodeheffer RJ, Kass DA. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community-based study. Circulation. 2005;112(15):2254-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Oertelt-Prigione S, Seeland U, Hetzer R. Sex and gender differences in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ J. 2010;74(7):1265-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Gorodeski GI. Update on cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;16(3):329-55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 95.Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(23):1801-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.Turgeon JL, McDonnell DP, Martin KA, Wise PM. Hormone therapy: physiological complexity belies therapeutic simplicity. Science. 2004;304(5675):1269-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Watson CS, Jeng YJ, Kochukov MY. Nongenomic actions of estradiol compared with estrone and estriol in pituitary tumor cell signaling and proliferation. FASEB J. 2008;22(9):3328-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, Damjanovic M, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, et al. Regulatory role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor for vascular function and obesity. Circ Res. 2009;104(3):288-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Ueda K, Adachi Y, Liu P, Fukuma N, Takimoto E. Regulatory Actions of Estrogen Receptor Signaling in the Cardiovascular System. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Iorga A, Cunningham CM, Moazeni S, Ruffenach G, Umar S, Eghbali M. The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Dworatzek E, Mahmoodzadeh S. Targeted basic research to highlight the role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Res. 2017;119:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.Mayes JS, Watson GH. Direct effects of sex steroid hormones on adipose tissues and obesity. Obes Rev. 2004;5(4):197-216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Bouchard C, Despres JP, Mauriege P. Genetic and nongenetic determinants of regional fat distribution. Endocr Rev. 1993;14(1):72-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Brown LM, Clegg DJ. Central effects of estradiol in the regulation of food intake, body weight, and adiposity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;122(1-3):65-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):978-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 106.Stubbins RE, Holcomb VB, Hong J, Nunez NP. Estrogen modulates abdominal adiposity and protects female mice from obesity and impaired glucose tolerance. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51(7):861-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 107.Zidon TM, Padilla J, Fritsche KL, Welly RJ, McCabe LT, Stricklin OE, et al. Effects of ERbeta and ERalpha on OVX-induced changes in adiposity and insulin resistance. J Endocrinol. 2020;245(1):165-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Crandall DL, Busler DE, Novak TJ, Weber RV, Kral JG. Identification of estrogen receptor beta RNA in human breast and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1998;248(3):523-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Matelski H, Greene R, Huberman M, Lokich J, Zipoli T. Randomized trial of estrogen vs. tamoxifen therapy for advanced breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1985;8(2):128-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(12):5925-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Rexrode KM, Ridker PM, Hegener HH, Buring JE, Manson JE, Zee RY. Polymorphisms and haplotypes of the estrogen receptor-beta gene (ESR2) and cardiovascular disease in men and women. Clin Chem. 2007;53(10):1749-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 112.Lo JC, Zhao X, Scuteri A, Brockwell S, Sowers MR. The association of genetic polymorphisms in sex hormone biosynthesis and action with insulin sensitivity and diabetes mellitus in women at midlife. Am J Med. 2006;119(9 Suppl 1):S69-78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Schuit SC, Oei HH, Witteman JC, Geurts van Kessel CH, van Meurs JB, Nijhuis RL, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2004;291(24):2969-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 114.Trayhurn P. Hypoxia and adipocyte physiology: implications for adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Ann Rev Nutr. 2014;34:207-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 115.Romacho T, Elsen M, Rohrborn D, Eckel J. Adipose tissue and its role in organ crosstalk. Acta Physiol. 2014;210(4):733-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Xu A, Vanhoutte PM. Adiponectin and adipocyte fatty acid binding protein in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(6):H1231-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 117.Lehr S, Hartwig S, Lamers D, Famulla S, Muller S, Hanisch FG, et al. Identification and validation of novel adipokines released from primary human adipocytes. Mol Cell Proteom. MCP. 2012;11(1):M111 010504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 118.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1999;257(1):79-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 119.Zhu W, Cheng KK, Vanhoutte PM, Lam KS, Xu A. Vascular effects of adiponectin: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic intervention. Clin Sci. 2008;114(5):361-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 120.Tanaka K, Wilson RM, Essick EE, Duffen JL, Scherer PE, Ouchi N, et al. Effects of adiponectin on calcium-handling proteins in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(6):976-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 121.Tsao TS, Murrey HE, Hug C, Lee DH, Lodish HF. Oligomerization state-dependent activation of NF-kappa B signaling pathway by adipocyte complement-related protein of 30 kDa (Acrp30). J Biol Chem. 2002;277(33):29359-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 122.Xu A, Chan KW, Hoo RL, Wang Y, Tan KC, Zhang J, et al. Testosterone selectively reduces the high molecular weight form of adiponectin by inhibiting its secretion from adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(18):18073-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 123.Pajvani UB, Du X, Combs TP, Berg AH, Rajala MW, Schulthess T, et al. Structure-function studies of the adipocyte-secreted hormone Acrp30/adiponectin. Implications fpr metabolic regulation and bioactivity. J Biol Chem.. 2003;278(11):9073-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 124.Tsao TS, Tomas E, Murrey HE, Hug C, Lee DH, Ruderman NB, et al. Role of disulfide bonds in Acrp30/adiponectin structure and signaling specificity. Different oligomers activate different signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(50):50810-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 125.Richards AA, Stephens T, Charlton HK, Jones A, Macdonald GA, Prins JB, et al. Adiponectin multimerization is dependent on conserved lysines in the collagenous domain: evidence for regulation of multimerization by alterations in posttranslational modifications. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(7):1673-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 126.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, Tsuchida A, Yokomizo T, Kita S, et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature. 2003;423(6941):762-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 127.Ding G, Qin Q, He N, Francis-David SC, Hou J, Liu J, et al. Adiponectin and its receptors are expressed in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes and upregulated by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma.J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43(1):73-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 128.Wang Y, Lau WB, Gao E, Tao L, Yuan Y, Li R, et al. Cardiomyocyte-derived adiponectin is biologically active in protecting against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298(3):E663-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 129.Skurk C, Wittchen F, Suckau L, Witt H, Noutsias M, Fechner H, et al. Description of a local cardiac adiponectin system and its deregulation in dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(9):1168-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 130.Hug C, Wang J, Ahmad NS, Bogan JS, Tsao TS, Lodish HF. T-cadherin is a receptor for hexameric and high-molecular-weight forms of Acrp30/adiponectin. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(28):10308-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 131.Ivanov D, Philippova M, Antropova J, Gubaeva F, Iljinskaya O, Tararak E, et al. Expression of cell adhesion molecule T-cadherin in the human vasculature. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;115(3):231-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 132.Doyle DD, Goings GE, Upshaw-Earley J, Page E, Ranscht B, Palfrey HC. T-cadherin is a major glycophosphoinositol-anchored protein associated with noncaveolar detergent-insoluble domains of the cardiac sarcolemma. J Biol Chem.. 1998;273(12):6937-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 133.Denzel MS, Scimia MC, Zumstein PM, Walsh K, Ruiz-Lozano P, Ranscht B. T-cadherin is critical for adiponectin-mediated cardioprotection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4342-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 134.Pou KM, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Vasan RS, Maurovich-Horvat P, Larson MG, et al. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue volumes are cross-sectionally related to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116(11):1234-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 135.Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Cardioprotection by adiponectin. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16(5):141-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 136.Shibata R, Ouchi N, Ito M, Kihara S, Shiojima I, Pimentel DR, et al. Adiponectin-mediated modulation of hypertrophic signals in the heart. Nature Med. 2004;10(12):1384-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 137.Sam F, Duhaney TA, Sato K, Wilson RM, Ohashi K, Sono-Romanelli S, et al. Adiponectin deficiency, diastolic dysfunction, and diastolic heart failure. Endocrinology. 2010;151(1):322-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 138.Hui X, Lam KS, Vanhoutte PM, Xu A. Adiponectin and cardiovascular health: an update. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(3):574-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 139.McManus DD, Lyass A, Ingelsson E, Massaro JM, Meigs JB, Aragam J, et al. Relations of circulating resistin and adiponectin and cardiac structure and function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Obesity. 2012;20(9):1882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 140.Hong SJ, Park CG, Seo HS, Oh DJ, Ro YM. Associations among plasma adiponectin, hypertension, left ventricular diastolic function and left ventricular mass index. Blood Press. 2004;13(4):236-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 141.Norvik JV, Schirmer H, Ytrehus K, Jenssen TG, Zykova SN, Eggen AE, et al. Low adiponectin is associated with diastolic dysfunction in women: a cross-sectional study from the Tromso Study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 142.Negi SI, Jeong EM, Shukrullah I, Raicu M, Dudley SC, Jr. Association of low plasma adiponectin with early diastolic dysfunction. Congest Heart Fail. 2012;18(4):187-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 143.Francisco C, Neves JS, Falcao-Pires I, Leite-Moreira A. Can Adiponectin Help us to Target Diastolic Dysfunction? Cardiovasc Dugs Ther. 2016;30(6):635-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 144.Sawada N, Daimon M, Kawata T, Nakao T, Kimura K, Nakanishi K, et al. The Significance of the Effect of Visceral Adiposity on Left Ventricular Diastolic Function in the General Population. Scientific Rep. 2019;9(1):4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 145.Fontes-Carvalho R, Pimenta J, Bettencourt P, Leite-Moreira A, Azevedo A. Association between plasma leptin and adiponectin levels and diastolic function in the general population. Exper Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19(10):1283-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 146.Han SH, Quon MJ, Kim JA, Koh KK. Adiponectin and cardiovascular disease: response to therapeutic interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49(5):531-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 147.Fukuta H, Ohte N, Wakami K, Goto T, Tani T, Kimura G. Relation of plasma levels of adiponectin to left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(8):1081-5. [DOI] [PubMed]